27 minute read

JACK FAQs Mark Evanier’s 1996 interview with Jon B. Cooke

Incidental Iconography

An ongoing analysis of Kirby’s visual shorthand, and how he inadvertently used it to develop his characters, by Sean Kleefeld

The New Fantastic Four cartoon from 1978 is largely only remembered from introducing H.E.R.B.I.E. the Robot as a replacement for the Human Torch. There were only thirteen episodes in total, and the show has never gotten a proper full release on home video (there were only a few episodes released on VHS, and a Region 2-only DVD of the series was briefly available in 2008), nor has it been made available on any legal streaming platform yet.

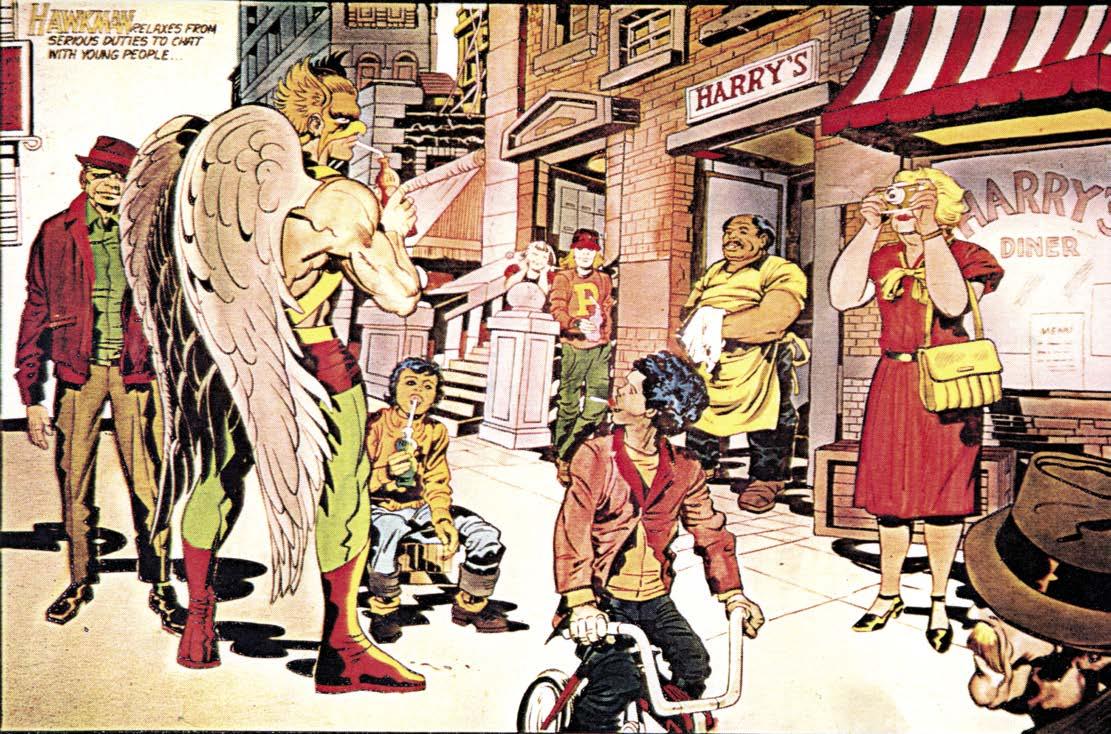

The show should be considered more significant, though, because it got Jack Kirby back into the field of animation (which provided him more financial stability and security than comics ever had) after four decades since leaving the Fleischer Studios. This time, DePatieFreleng was putting together a cartoon based off the Fantastic Four, and The Thing in his short-lived costume (with helmet!), from Fantastic Mark Four #3 (March 1962). Note the whited-out and redrawn shadowed “4”. Evanier told them that the man who designed the characters in the first place lived only about 30 miles away from their Burbank studios. Thus, Jack was hired to create storyboards for the cartoon, loosely based on the comics he had himself worked on in the early 1960s. So let’s take a look at how Jack drew the Fantastic Four’s uniform for these cartoons, and compare that against what he had done for the comics. (For the focus of this piece, I’ll be setting aside the initial design considerations like masks that Jack changed before the comics were even published, as shown above for the Thing.) The first thing I should point out is that the animators were not relying on Jack’s artwork for the specific character designs, only the basic shot compositions. Jack was still largely drawing as if he were working on a comic book, and the animators needed character designs that were easier to animate, so a number of details from the boards didn’t make it onto the animation cels. Brad Case is credited as the animation director, but I can’t seem to find if he was actually the one who worked up character model sheets for the animators. Regardless, if you do get access to the cartoons themselves and wonder why they look nothing like Jack’s work, that’s why. While the Fantastic Four’s basic jumpsuit design is pretty straightforward, there were a few details I thought to key in on. The two I had previously noticed that had changed just within the comics were the “4” chest emblem and the width of the black collar. Except the collar width changed with issue #6,

INNERVIEW A Chat with Steve Gerber

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on April 30, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow [Steve Gerber (September 20, 1947–February 10, 2008) is probably best known within comics as the creator of Howard the Duck, but his work for Marvel also included Man-Thing, Omega the Unknown (created with Mary Skrenes), and many other properties. While engaged in a legal battle with Marvel over ownership of Howard the Duck (which made him a vanguard in the fight for creator’s rights), he approached Jack Kirby and several others to donate their services producing the benefit comic Destroyer Duck. This interview took place after Gerber had settled that dispute, wherein he reflects on his experiences with Jack Kirby at the Ruby-Spears animation studio.]

JON B. COOKE: What was your earliest exposure to Kirby’s work? STEVE GERBER: I really had associated Jack with the few issues of The Fly and Private Strong he did—the revival of The Shield. The Shield stuff I liked quite a bit, actually. JON: Do you still agree with your Fantastic Four #19 Fan Page letter (October 1963), that you’ve never seen a worse artist combination than Kirby and Ditko? STEVE: [laughs] Yes. [laughs] They were wonderful separately, and absolutely awful together. Ditko is one of Kirby’s worst inkers of all time. For two artists who were so wonderful separately, I never thought the combination worked at all. JON: Did you get a chance to work with Jack at Marvel, when he came back? STEVE: No, not at Marvel. JON: You left Marvel in 1978? STEVE: Yeah, I left a little after he came back. All the stuff he was doing at that time, he was doing alone: Black Panther, Machine Man and all those things. JON: So you first met Jack when? STEVE: I think 1979, when he came to Ruby-Spears to work on the Thundarr series. JON: His job was replacing Alex Toth? STEVE: Probably not replacing. Alex did the initial designs for the series. I don’t know if Alex was ever contracted to do more than that. It doesn’t work the same way in television that it does in comics. Somebody’ll be brought in to do a particular presentation piece for the network, and that’s the beginning and the end of their job. They may have nothing whatsoever to do with the series after that. I suspect Alex was brought in on a basis like that, so that when he left, he may have gone on to something else altogether. JON: Did you work closely with Alex? STEVE: No. I never met Alex. JON: In your initial concept, what did Alex have to work from for Ookla? STEVE: Well, I don’t remember exactly the words I used, but I gave a description of the character. He’s about eight feet tall, big and hairy, a little bit like an ape, a little bit like a bear—doesn’t talk, afraid of water, whatever. And I just tried to give an impression of the character, the same way I would describe a character for a comic book artist to draw. JON: And Alex came back with a really classic Toth-like, quintessential design. How would you characterize your experience working in animation? STEVE: Oh brother. When I first went to work for Ruby-Spears, a friend of mine named Gordon Kent worked there. He came up to me and said, “Don’t expect it all to be like this.” [laughs] What had happened was, I’d come in and sold the first series I’d ever proposed to anybody. The producers saw it about 85% the same way I did. The network saw it about 85% the way he did, and while we certainly had conflicts with Standards & Practices—anytime you do an action show, that happens—the show basically went very

smoothly and turned out a lot like what I had in mind. It never happened again. [laughter] JON: What other shows did you work on? STEVE: Oh, no! For that very reason, I will never tell you! [laughs] It was five or six years before the next satisfying experience in animation came along, and that was story-editing G.I. Joe. JON: Was Larry Hama involved in the animation side of that? STEVE: Not really. He worked very closely with the toy company on the East Coast, but had almost nothing to do with the animation end of it. JON: What was so gratifying about working on G.I. Joe? STEVE: It was two things. It was a syndicated series, not a network series, so we didn’t have Standards & Practices to deal with. We had an incredibly intelligent producer by the name of Jay Bacal; he was a Harvard graduate, and younger than I was. If anything, he was pushing me to kick at the seams of the envelope a little more. It was some of the best stuff I’d ever

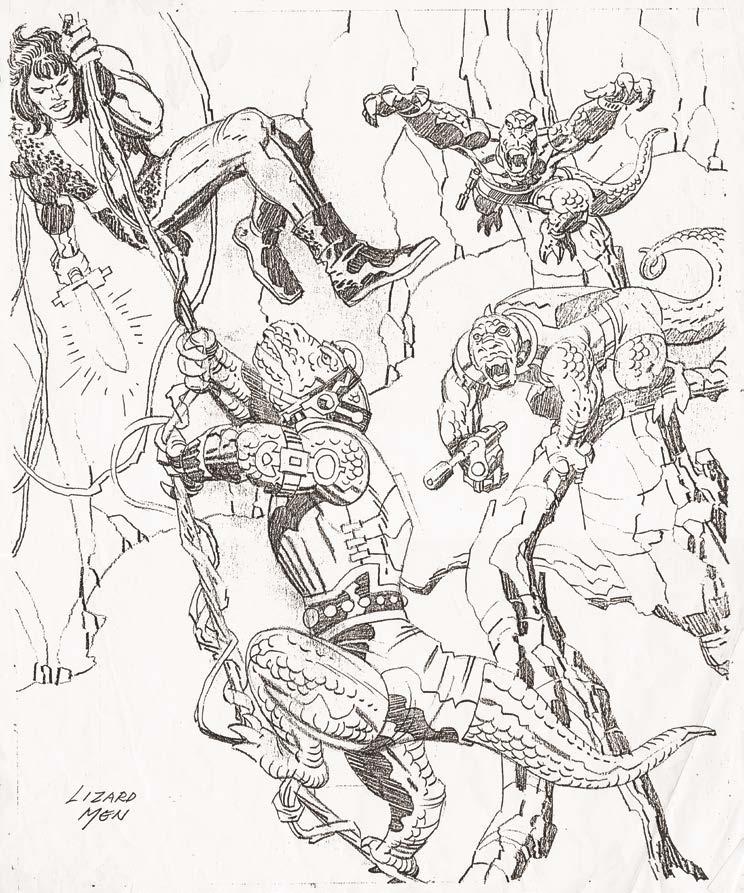

[previous page] Thundarr concept work. [right] Since Steve enjoyed Jack’s 1959 revival of The Shield, he must’ve really loved this Alfredo Alcalainked concept drawing for Ruby-Spears.

Joe Ruby: A Real Gem

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 9, 1996 Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

[Joe Ruby (March 30, 1933–August 26, 2020) wore many hats in the animation industry, including writer, producer, and even music editor. He is best known as a co-creator of the animated Scooby-Doo franchise, together with partner Ken Spears. In 1977, they co-founded RubySpears Productions to create animated series for network television and syndication, and made R-S the most successful TV animation company for a period in the 1980s. His hiring of Jack Kirby marked a major turning point in Jack’s life and career.]

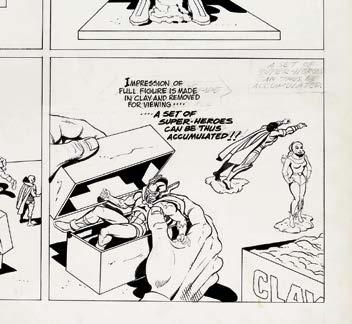

[top] Upon first seeing Jack’s “Hidden Harry” concept in the Unpublished Archives card set, this mag’s editor thought The King must’ve been slipping when he came up with it. Aahhh, but I didn’t realize Jack was also pitching toy ideas, which makes a lot more sense for HH! JON B. COOKE: When did you first meet Jack? JOE RUBY: It was in the early 1980s. He did some work for us, and we liked him so much, that we continued to do a lot of work, and we put him on staff for six years. He was great! JON: Do you remember how he came to work for you? JOE: We were doing a show called Thundarr the Barbarian, and we needed someone to design—because in those days, we took a kind of comic book, older-type skew on the show. We wanted someone who really could design great characters. Jack was brought in. I don’t remember exactly, but that’s how it happened. So on Thundarr, he did the design work of all the other characters for the series, and then continued to work with us. JON: Were you aware of Jack Kirby’s reputation beforehand? JOE: I was very familiar with all of the characters that he had created, but I can’t really remember if I was familiar with him. I probably was, yes. JON: When he was working for you, was he answering directly to you, or John Dorman, or...? JOE: He basically answered to me, but John was in the middle. John was the art director on the show, so he would go to John as well. But whatever happened had to come through me at the end, obviously. JON: Did you give Jack specific assignments, or did he just go off and create concepts? JOE: I gave him specific assignments, and he also did other things that he brought me. He was very prolific, as you know. He was uncanny; he would just bring in stuff all the time. JON: I’ve been speaking to other people who worked at Ruby-Spears, and they say you and Jack spoke the same language. Were you personal friends? JOE: We weren’t close personal friends, but we were friends, yeah. When someone works for you for six years, and you see them all the time, you become

friends with that person, and his wife Roz, who was very nice. They lived out in Thousand Oaks. But Jack generally would work at home, and come in maybe once or twice a week. We did work very closely, and we did speak the same language. It was just very easy, you know? When I’d say something, he’d know exactly what I wanted, and he’d deliver it. He was terrific. JON: In the early 1980s, was that the Golden Age of Ruby-Spears? JOE: Yeah. I think for us it was from the 1980s into the early 1990s. We had so many shows, I can’t even begin to tell you. We had a huge staff of people, and we did quite a bit of artwork. We would develop toys as well as shows. We were venturing into a lot of things. We sold several toys and other things as well. We had some of the top people in the industry working for us at the time—very creative people. JON: What were your personal favorites, of the cartoons Ruby-Spears produced? JOE: Well, I thought Thundarr the Barbarian was one of the best ones we’ve done. We also did Alvin and the Chipmunks, which was a huge success. We did Mr. T… JON: Goldie Gold and Action Jack. JOE: Yes, those were the originals. The others were based off known personalities, and there were also the established characters. We did Punky Brewster; Rubik, the Amazing Cube; all the video games at the time, like Dragon’s Lair. We had an hour video game series on, which featured five or six video games we turned into shows. We did Rambo, that was syndication. We did Centurions, which was a toy show. Sectaurs. We did Police Academy, Superman, Heathcliff.

JON: Do you know where the concept of Turbo Teen came from? JOE: Yeah, that’s was mine. A boy turns into a car. It was kind of a wild one. In those days, they thought I was nuts, but ABC bought it. [laughs] It was a good show. It could be even wilder today. JON: Can you give me a brief background of Ruby-Spears? How did it begin? JOE: Well, my partner Ken Spears and I were working for ABC at the time, for Fred Silverman. We go way back; we were writers at Hanna-Barbera, and we also did live-action things. For animation we were writers, and we were at Hanna-Barbera for many years. We got Scooby-Doo off the ground, and then we came to work for CBS, and ABC for Fred Silverman. We created a lot of shows: Captain Caveman, Blue Falcon and Dyno-Mutt. Then Filmways was looking for a studio, and Peter Roth, who we worked with at ABC, recommended us and put us in business. So we went into business, and Fred gave us a commitment. Fangface was our first show. That’s how we got started, in the very late 1970s.

We were at Filmways a few years, and then we were sold to the Taft Broadcasting Company. We were there through the switch to Great American Broadcasting, for a total of ten years. And then when Turner Broadcasting bought them, they only kept HannaBarbera. They had several other companies, and they dissolved them, us included. And we’ve been independent since then. JON: And you’re still making presentations and making pitches? JOE: Yeah. The business has changed quite a bit. In the heyday, the major studios weren’t involved. Warner Brothers and Disney weren’t putting out the shows. The competition has completely gone around. It’s much, much tougher. There’s not as many spots open, and the availability of certain properties, and the monies involved in getting properties—and now you have to try to get partners, and things have changed from a business point of view. JON: People have said it was an event when Jack would come into the offices. Did you witness that in the art department, when he would come in on Mondays with his arms full of art boards? Was it an event for you? JOE: Oh yeah, I always was anxious to see what Jack had. When he’d come into the office, yeah, he had a whole bunch of stuff with him. A lot of artwork, and he would spread out, and we’d have a good time. Everything was terrific. I always wanted to do a pure Jack Kirby show, where we wouldn’t change things like proportions for animation, and just do his stuff “pure.” But we never were able to. JON: Do you remember any specific stories about Jack? JOE: Not off the top of my head. There was just a lot of stuff we were working on. I’d have to go back and check into the artwork. JON: Would you characterize any of the unproduced work, or the produced work, as being quintessentially Jack’s ideas? I know the concepts were all worked on by lots of people, but is there anything that comes to mind? JOE: There’s a few things in the unproduced stuff, that were his stuff, but I’d have to go back and look at it. JON: The Gargoids? Power Planet? Roxie’s Raiders? Street Angels? JOE: No. A lot of that stuff was mine. I used to feed him a lot of projects. These were all ideas that we handed out. JON: What was Animal Hospital based on? JOE: We were just trying to make a soap opera. JON: Jack produced an enormous amount of work at Ruby-Spears, but not much of it got produced. Is that the nature of the business? JOE: Yes, it’s the business. Obviously, there’s only so many series or shows you can sell, and we were also doing different types of shows. Some were action, some were comedy which had more cartoony

INNERVIEW John Dorman Interview

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 10, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow [Animation veteran Tom Minton summed up John Dorman (June 29, 1952–January 29, 2011) thusly, following Dorman’s passing: “In addition to being a prolific and experienced creative talent, John Dorman was a near-mythic character with an epic sense of the absurd. He was much more than a storyboard artist or art director, as anyone who worked for him in the early to mid-1980s can attest... John defined ‘intense’ and could be tough to please, but ultimately took the people he believed in more seriously than he did himself.” From storyboard artist to art director, his influence in animation cannot be overstated. Here, he discusses what he did to make Ruby-Spears such a remarkable place to work, and his own experiences with Jack Kirby.]

John Dorman at Filmation studios in 1979.

Photo by Tom Minton.

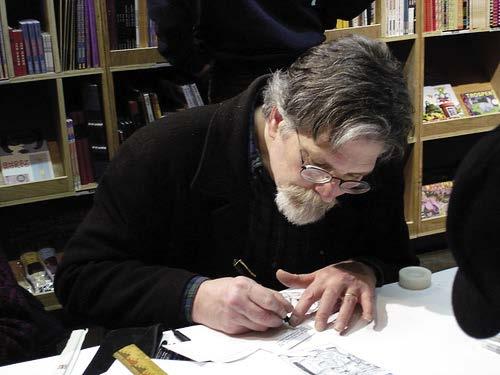

JON B. COOKE: When did you first encounter Jack and his work? JOHN DORMAN: The first time I saw Jack in the industry, was when I worked at DePatie-Freleng. I was hired to draw layouts, and I was supposed to draw storyboards on the Fantastic Four. They said, “You can draw boards, because we only have one board artist, and that’s Jack Kirby.” Now, storyboards are the hardest, most labor-intensive, anonymous, difficult, technically rife portion of animation. It’s a really hard job, so if you can do a half-hour show in five–six weeks, you’re really fast. That’s a very fast artist. I didn’t even meet Jack there; my first encounter with him was that he would turn in a finished half-hour storyboard every week—that he wrote while he was drawing it. He wrote it and drew it. Normally, you had careful scripts, like at DC Comics, where the animation and every scene is figured out. The character is going left to right, with close-up directions. You can almost just follow the directions and do it. Even the visuals are taken care of in the writing. A lot of that is because they had so much product they needed quickly, and there’s not enough storyboard artists, and they had to get other artists that don’t know how to make film, but know how to draw heads, and they know how to draw a close-up. Artists were almost never invited into creative meetings, except to graft a look onto a show, after it had been created. Jack brought a whole different mentality. He came in and his worked just punched its way right through the wall by saying, “I invent this stuff. I write it. I draw it. I do that all faster than any team has ever done, all by myself.” And by the way, Jack was also producing two finished comics a month at the time: Devil Dinosaur and Machine Man, and a storyboard a week for a half-hour episode, and he would design all the incidental characters too. This normally takes a huge body of people, and he’d do everything all by himself. That’s the thing that was really alarming

inker in the business. He gave this industry a big shot in the arm. Joe was an honest, conscientious, fair, and generous guy.

Anytime a minor success came in, Joe and Ken gave the maximum of recognition to us. They put us in really great big offices; anything we wanted, we got. Any art equipment we wanted, we got, and we ordered lots! [laughs] At Hanna-Barbera, they had a relative of one of the owners, who sat in a closet in a suit and handed out pencils, and took down who was taking the pencils. [laughs] He asked me what I had in mind to do with this pencil, and I said, “You’re kidding.” [laughs] I’d say, “I’m planning on drawing layouts,” and he’d say, “Well, why do you need two pencils?” [laughs] We stole all the best artists; all the other companies’ artists wanted to work with us, cause we’d pay them more, they got more liberties, and they were around people that truly loved what they were doing. And Steve bred that type of thing among the writers. It was easy to work with them, cause they weren’t trying to seize authorship over something. It really was special, and Joe and Ken were dispersing money like it was being printed someplace close.

Ken Spears [below], even though he was in charge of production at that company, never acted like he was an expert. He was always excited about doing something new and better. He was always trying to rearrange budgets and work things out, and he always succeeded. Ken was a really fair guy, and he was always kind, and listening, and saw everyone’s side. He’s just one of those guys that, within minutes of meeting him, you really liked him. We first had a floor with just artists, and then we had a separate building. As the artists got more liberties, we felt we had to be better than everybody else, and work harder, and then we could do anything we wanted. That last part bugged everybody who wasn’t part of our group, but they were only there from 9-5 anyway, and we were there overnight, often. The artists were so happy about what was happening, and there was just such a general good vibe, that people put in more personal time and energy to see to it that the whole thing kept going. COOKE: Did you consciously foster that? DORMAN: Of course! Because we had so many shows, and we were adding artists from the comic book industry. Comic artists were all about instant gratification; they liked first-round knockouts. They didn’t worry that their stuff wouldn’t animate, or their drawing was only good for one pose.

We kept moving to different buildings, different annexes. We had one completely wood house which Cheech and Chong owned. We worked in there awhile, and then Jack started reporting to me, and getting assignments from me. But you have to understand something about the dynamic of Jack. If Jack comes in, and you go, “Jack, here’s what we need. We’re gonna do a deal with a toy company, and we’re going to do a thing about a guy with a boat that’s the fin of a living iceberg” or something real peculiar for him to draw, you don’t know how he’d handle it. Well, he’d handle it by coming back with a show about another planet. [laughs] He competed with you; he tried to blow you out of the water. And I realized, that’s just how he is. With Jack, what we tried to do was find out what he liked, and accommodate him. You could ask Jack to do one kind of show, and he’d come back with another, and you’d save it and go, “Let’s try to make a show out of this” or you’d use it in another show. Jack thought such big ideas, that he was treated different than I’ve seen any other artist treated. He basically got to come in and do anything he wanted at all times, and he was loved for it.

iNNerview Jim Woodring Interview

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 6, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

[Jim Woodring is best known in comics for his self-published magazine Jim, and as the creator of his character Frank, who has appeared in a number of short comics and graphic novels, but he’s also an accomplished fine artist and animator. Jon B. Cooke considers him one of “the top five greatest cartoonists alive,” and here he quizzes Woodring about his tenure under friend and art director John Dorman at Ruby-Spears Productions.]

JON B. COOKE: When did you first meet Jack Kirby? JIM WOODRING: I first met him in 1981, when I started working at Ruby-Spears. He already had been hired when I came aboard. They did a TV show called Thundarr the Barbarian, and he did some of the character design and some of the show design for that. Right after he did that, I started working there, and they tried to find other things for him to do. They gave him a stab at storyboards, without really telling him how to do storyboards, and he just tried to wing it. He did some really innovative things, like he had a close-up of somebody’s face, to the extent that all you could see was their eyes, and the shot called for the camera panning from the left eye to the right eye while about two minutes of dialogue were spoken. [laughs] He just made up his own rules. JON: Did he come up with the concept for the stories he was storyboarding? JIM: No, he was given a script, like all the storyboard artists were. He looked at some other boards, and from his own take on how it was done, he did his. But it was completely unusable. It couldn’t have been done the way he called for it. He didn’t really understand how to do it. JON: So what was he primarily doing at Ruby-Spears? JIM: Character design and show ideas. When I started working there, his job was to come up with ideas that might be turned into TV shows. So he would come in every Monday morning with a big thick stack of Crescent board under his arm, on which he had drawn characters and settings and show ideas, and he’d given names to all the shows and all the vehicles and all the characters. They were all really, really imaginative. In fact, there’s a set of Jack Kirby cards

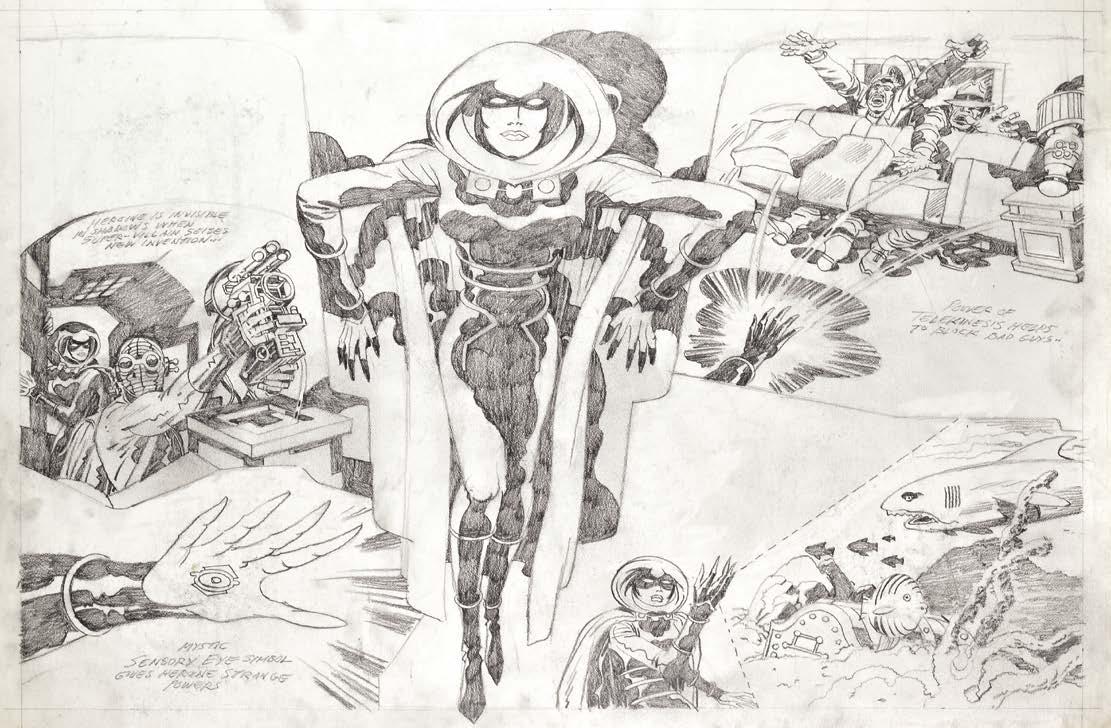

Based on the eye on her palm, this unnamed female may’ve been a character for—or which morphed into—the unproduced Warriors of Illusion project [next page, bottom].

out, and that stuff is a lot of the pitch artwork he did for RubySpears. They were quarter sheets of Crescent board, so they were 20" x 30". JON: Did you color and ink a lot of these? JIM: Yeah, I did. I inked most of them, and colored a lot of them. JON: Some of this stuff is outstanding. Like the Warriors of Illusion; did you do the coloring on that? JIM: I did some of the coloring on that. Most of that was done by a guy named James Gallego. JON: You were unfamiliar with Jack’s work prior to that? JIM: Yeah. I was aware of his name, and aware that he was a comic artist, and well regarded. But I couldn’t have told you what he drew, or how he drew. JON: So you weren’t even aware of his reputation as one of the Marvel guys? JIM: Not until I’d been working there a couple of weeks. I’d tell people that I ran into, that I was working with him… JON: Were they floored? JIM: A lot of them, yeah. JON: Were they surprised to find out he was working in animation? JIM: Yeah. JON: What was your impression of him when you first met him? JIM: Well, that he was unusual in a good way. How shall I put it? He didn’t seem to have the kind of adult, pragmatic, hard, dull edge that most other grown-ups did. I think it comes from having such a rich inner life, and putting such value on drawing and imagination, and comics and cartooning. That was his business, that was his life. He just wasn’t a cold-edged pragmatist. He lived for more and better works of fancy. JON: How did he react to the world of Hollywood? JIM: Well, I only saw him at work. I was never up to his house. He had a professional demeanor; a way of being nice that was genuine, but you also knew it was his work face. So I don’t really have much of an idea of what went on in his mind, or how he felt about anything really, because he was pretty superficial when he was in the office. I know that at Ruby-Spears, at a certain point after he’d done all these drawings and none of them had been made into TV shows, he began to be a little frustrated by that. Because he was doing all this work and coming up with really good ideas, and none of them ever went anywhere. JON: Did you ever talk to him about the business? JIM: Well, I listened to him talk about the business. There was absolutely nothing I had to tell him. His take on the business was pretty personal and idiosyncratic. He didn’t seem to have much awareness about what other people were doing; he was just clued into his work, and some times are better than others. He had that Old World habit of maintaining respect for the office of Editor. He was loathe to say bad things about editors or the people he worked for. When I met him, it was at the very height of that “God Save The King” and “Give Jack Back His Artwork” and all that, and even in the thick of all that, when he had plenty of encouragement to, he never said anything bad about Stan Lee.

JON: Was it just Mondays when he’d come in? JIM: Well, he’d come in Mondays with a big stack of Crescent boards under his arm, and we’d all come in and look at them. We’d all stand around and laugh, and point at the various things, and try to make him stay and talk and tell us stories. JON: Did you go back and look at Jack’s earlier work after meeting him? JIM: Yeah, I did. JON: I seem to perceive an increasingly bizarre sense of humor coming out of him at that point. Did that permeate his work that you saw? JIM: Oh yeah, especially toward the end of his tenure there. His work got sort of recklessly crazy. The one that I really wish I could find is, he did a drawing of a character named Heidi Hogan, which was a bearded lumberjack in a pinafore dress, jumping off a cliff with a propeller beanie. [laughs] It just looked like pure automatic pilot. He must’ve been thinking of something else entirely, and automatically drew

this nonchalantly insane picture. [laughs]

There was another kind of ill-fated project the studio had going called Animal Hospital. I don’t know if he was asked to do it; I suppose he was. He suddenly started coming in with newspaper daily strips. Penciled but not inked, but he had written it, and someone else had lettered it, and it featured all the characters he’d invented for Animal Hospital. It was like five or six days’ worth. JON: Did he come up with the Animal Hospital concept? JIM: No, that was by Joe Ruby, I believe. JON: What was the genesis for that? JIM: The desire to create a sophisticated post-primetime TV show