and

Editing by Jon B. CookePublished by John Morrow

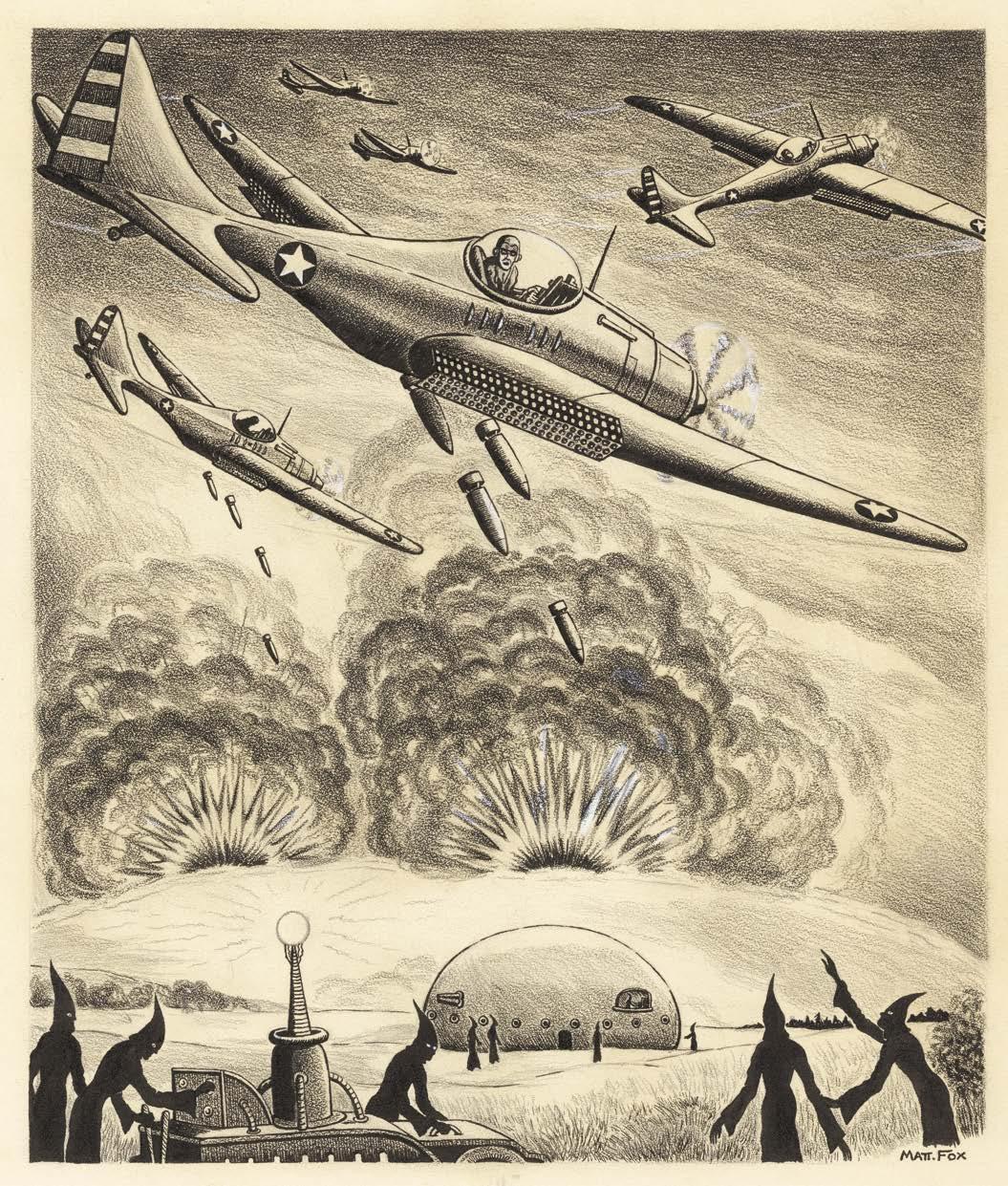

Cover Art by Matthew Fox

Dedication

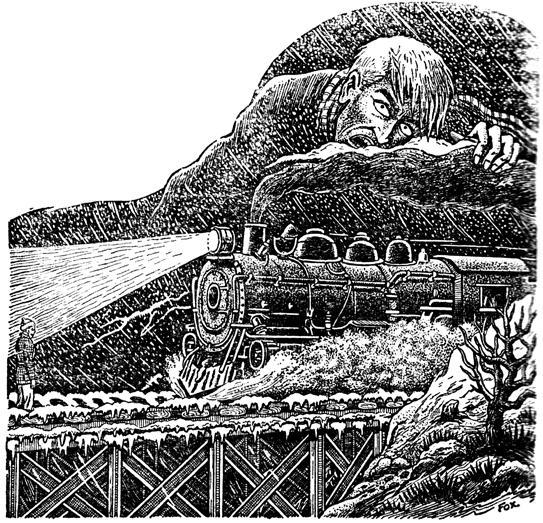

To Matt’s sister, Rose Van Wees, who loved her brother dearly and cared enough to save his art for posterity. The cover is Matt Fox’s unpublished Weird Tales cover painting, circa 1953, and it is © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions. The double-page title spread image is “The Wendigo,” Famous Fantastic Mysteries [June 1944].

Editorial Package ©2023 Roger Hill and TwoMorrows Publishing. Text ©2023 Roger Hill.

Copyrights & Trademarks

Weird Tales TM & © Nth Dimension Media, LLC.

Adventures into Weird Worlds, Creatures on the Loose, Journey into Mystery, Journey into Unknown Worlds, Marvel Tales, Men’s Adventures, Mystery Tales, Mystic, Strange Tales, Strange Tales of Suspense, Tales of Suspense, Tales to Astonish, Uncanny Tales, and World of Fantasy TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Cover painting, illustrations, photos on pages 6, 11, 16, 19, 22, 29, 99, 106, 107, 111–118, 120 are © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions.

“Matt Fox: The Strangest Province” introduction © Peter Normanton.

Special Thanks

To those who helped with illustrations for this book: Skinner Davis, Bud Plant, Charlie Park, Stephen Fishler, Cory Sedlemeier, and Dr. Michael Vassallo.

TwoMorrows Publishing

10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, North Carolina 27614 USA

www.twomorrows.com • email: twomorrow@aol.com

First Printing • June 2023 • Printed in China

ISBN-13: 978-1-60549-120-2

Artwork © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions.

Artwork © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions.

uring the early 1970s, Jerry Bails got a hold of Matt Fox’s Connecticut address and sent him the standard Who’s Who of American Comic Books questionnaire to fill out and return. Here’s what the artist wrote himself and sent back to Bails. (The parenthetical (p) and (i) indicate pencil art and inks, respectively.)

MATTHEW (MATT) FOX (1906– ) Artist. Major influence: Alex Raymond; Cartoons; Adv art; Lithographs; Pulp illus; Covers of Weird Tales (oils), Color woodcuts; Water colors; Oil paintings; Etchings, Comic book credits: (p) & (i). Youthful: (1952–53) fantasy; Marvel: (1952–56) horror, s-f; (1962-63) s-f, fantasy.

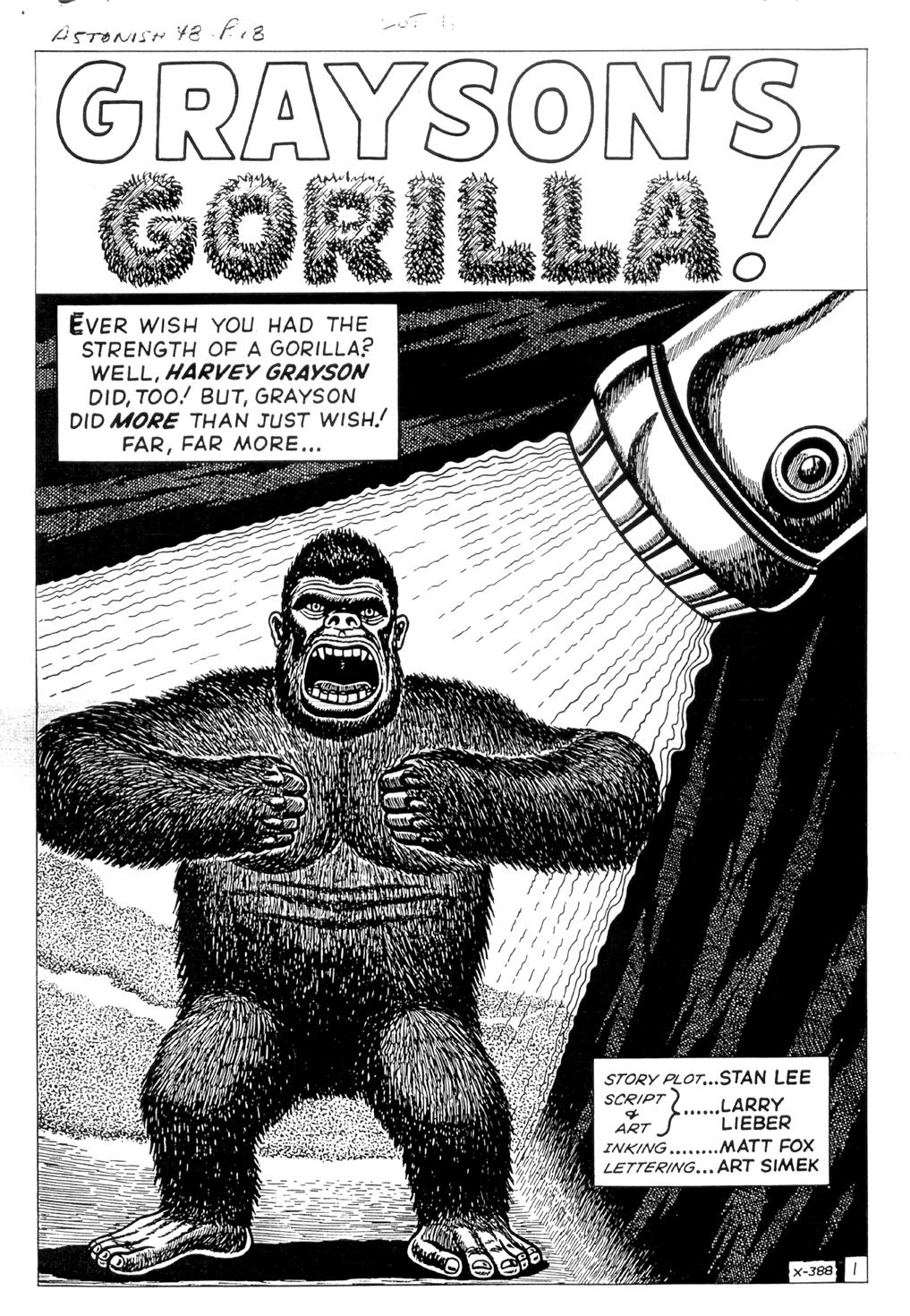

I first discovered the art of Matt Fox during the early 1960s while reading the back-up fantasy stories he had inked, over Larry Lieber’s pencils, in Marvel Comics titles, such as Journey into Mystery, Strange Tales, Tales of Suspense, and Tales to Astonish. In many cases, These stories were more appealing to me than some of the super-hero fare being offered in comics at the time. As an aspiring amateur artist myself, I soon realized just how difficult it was trying to create something with a pencil, out of my own imagination, and then inking it with a Crow Quill pen. My early attempts at art looked crude and, in some cases, overworked, and not very realistic. I couldn’t begin to form slick, quick lines like Jack Kirby or Wally Wood. My drawings had a lot of non-professional scratchings to them. In time, I became pretty good at inking those drawings and adopted the art of stipple for shading; a technique I picked up from other amateur artists at the time, including Matt Fox. I think this may be one of the reasons that I—and other young artists—were first attracted to the unusual work of Matt Fox. In those days, a lot of us wanted to be comic artists, and if we couldn’t be as good as Kirby or Wood, we could at least come close to Matt Fox’s work, right? Well, not really. After all, by that time, Matt Fox was a seasoned pro and had the dedication to stick with something he loved to do.

Many years later, during an interview, Larry Lieber admitted that he struggled himself with the drawing of those stories and didn’t care at all for Fox’s embellishments over his pencils. Lieber claimed that Fox made his work look stiffer than it already was, and made it look like wood cuts, which it no doubt did, in some cases. To this day, however, those stories are remembered more by collectors for the Matt Fox inking than anything else. Comic fans have been discovering and acquiring a taste for this artist’s work for the past fifty years.

Opinions vary greatly about Matt Fox’s art; you either like it or you don’t. I tend to think that most people would agree there is a certain charm about it, especially his body of work produced for Weird Tales and other pulp magazines during the 1940s to 1950s, only some of which has been reprinted in the ensuing years. Many collectors may not even be aware of Matt’s early pulp magazine contributions.

Matt’s work, on his own, usually dripped with horror and odd-looking characters. The editor of Weird Tales obviously thought his art weird and unique enough to be published in a magazine presenting… “weird tales.” During my lengthy research into Matt’s life and career, I discovered the artist loved to read stories of horror, fantasy, and science-fiction, and even more so, loved to illustrate them. It’s a little too easy to judge an artist’s work based on a few comic stories where he was only inking over someone’s pencils. To fully appreciate the talents of Matt Fox, one must first discover and absorb the cover paintings and interior pen-&-ink illustrations he produced for Weird Tales and other pulp magazines, before coming to comics. And then move on to Matt’s early comic book work where he began to mature even more. Only then, can one form an educated opinion about it. Hopefully this volume, and testament to his art, will enlighten you. We certainly hope so.

Roger Hill November 2022Marcy Matthew Fox was born in New York City on November 8, 1906. His mother, Minnie Fox (neé Flesche), was born of Jewish ancestry in Russia in 1881 and immigrated to the United States in 1902. Matt’s father, Morris Fox, had been born in Russia in 1879 and came to America in 1900. According to the family, Minnie and Morris had met through a dating service, and as related in the 1910 New York Census, the couple was married on October 28, 1905. After the nuptials, the family settled into a small tenement apartment in the Jewish section of East Harlem. Morris worked in the garment industry.

Later, in 1909, a daughter named Rita (who would later prefer to be called Rose) was born. The 1915 New York Census lists Marcy’s father as a “shirt ironer,” while the Census from 1925 indicates he is a “traveling salesman.” His occupations varied widely and, according to the family, he was a highly educated man, but couldn’t seem to hold a steady job. This resulted in the Fox family constantly moving and scraping to make ends meet. Minnie Fox and her children were hopeful that things would improve, but eventually the unemployed Morris began showing a darker side with abusive behavior emerging. Morris had a violent temper, which he took out on the family, especially on young Marcy. Exploding in anger, he would aggressively force his son up against the wall and punch him in the stomach. This abuse caused Marcy severe intestinal problems for the rest of his life. During his childhood, Minnie became very sick. With a husband who didn’t believe in working much, times became even harder for the family to get by. In 1918, the Fox family moved to a cheaper apartment located at 339 East 118th Street, on Manhattan’s tough Lower East Side. At some point, Marcy started using his middle name Matthew—or just Matt—for short.

As a young boy attending grade school, Matt took an immediate interest in art and, at the age of eleven, he won the Wanamaker Medal for the “Most Outstanding Art Entry” of all school-age contestants in the city of New York. He would eventually win other awards during his school years and soon discovered—and fell in love with—many of the popular newspaper comic strips of the day. He read the funnies whenever he could get access to discarded newspapers and was soon emulating his favorites with ink on paper. At some point, he decided he wanted to become a professional cartoonist and,

by 12, was headed in that direction. He created his own comic strip characters, first using pencil and watercolors, then later graduating to straight pen-&-ink pages in black-&-white. These were drawn in a Sunday page format on small sheets of ruled paper taken from his school tablets. Some of these pages were akin to pulp paper, and a few examples still exist today, only because his sister, Rose, saved them.

Even at this young age, Matt demonstrated an interest in the macabre, creating a strip called “Poor Mr. Undertaker.” Later examples show the “Poor Mr.” was dropped in favor of the abbreviated title of “Undertaker.” Although the gags in these early efforts are extremely crude and old fashioned, one can recognize the devotion the young artist applied to these strips. One surviving example, dated August 5, 1921, depicts a young man who decides to become an undertaker in order to make some money. Fox drew the strip in four tiers, with each panel numbered from one to twelve, showing the young man accosting old people on the street, prematurely

offering his services before they die. Finally, after being turned down by everyone, he hits an old man over the head with a large hammer, figuring this is the only way to provide his “undertaking” services and earn some income. Not quite yet dead, the old man retaliates by clobbering the young undertaker on the head with a large rock, then carts him off to the hospital to have them “examine his dome.” Two examples of these original strips are reproduced on this and the next page for the first time.

Sometime in the early 1920s, Matt’s father’s abusive nature worsened, and Minnie could take no more. So, with help from Matt and Rose, she managed to force Morris out of the household. At first, they had problems keeping him out, but eventually found support from a local neighborhood gang called the “Society of the Black-Hand.” This Italian crime organization—also known as La Mano Nera—understood the family’s situation and, since they didn’t care for Morris to begin with, helped enforce his expulsion. Whenever spotted peering through the windows or trying to sneak back into the neighborhood to make his way home, the Black Hand would quickly expel him. After a few years of this, he finally went away for good and was never heard from again. Neither the family nor Ancestry.com can provide any information as to Morris Fox’s ultimate fate.

By this time, Matt only had one year of high school under his belt and, at the age of 14, he was forced to quit school to help support the family. In a 1975 newspaper interview the artist said, “I never had any art training. I absorbed it from people in the art world. It took lots of practice and experimenting.” Matt compared himself to Winslow Homer, whom he said was “self-taught and left-handed.” With no formal training to speak of, New York wasn’t the easiest place for a self-taught artist to find work during the 1920s. Fortunately, Matt was flexible and persistent in doing odd jobs. At the age of 17, he managed to land a gig at a printing company where he learned how to set type, do paste-up work, and run a small press. His artistic interest gave him an edge doing advertising art, sign making, and lettering jobs wherever he could find them. Being the gentle and good-natured soul he was, Matt made friends easily in the printing business.

The only thing holding him back was his health. Besides the abuse suffered at the hands of his father, Matt also suffered from colitis, a crippling disease that eventually caused damage to his legs and body, which kept the lad out of sports during his school years. Although he was tall, with decent good looks, and appeared to be healthy, the malady had a damaging effect on his physical form for the rest of his life. Walking became a labored and restricted effort, and just trying to get around New York City became a painful experience. He could not ride in a car or a subway without experiencing great pain.

Opposite page: Nascent art by Matt Fox. This page: Even before his teenage years, “Marcy” was determined to become a comic strip cartoonist.

Matt had always enjoyed an interest in fantasy and horror and, after discovering pulp magazines and books, he became an avid reader when he could afford to buy them, mostly from secondhand outlets. At the same time, he developed a love for music. While working at the drawing board, he would listen to the radio, enjoying favorites such as the Nicholas Rosa Opera Company and other local operatic radio programs. Many art jobs offered to Matt had to be turned down simply because his mobility was so curtailed by colitis. Because of this, he had very little social life. Eventually he did meet and fall in love with a young girl, but things didn’t work out because Matt knew he would never be able to support a wife. He entrenched himself into his art and that relationship dissolved.

In 1923, when Matt was 17 years old, a new pulp magazine called Weird Tales hit the magazine racks. From March of 1923 to September 1954, Weird Tales was the most influential of all pulp magazines in the horror and fantasy genres. The magazine’s main focus was on stories of the fantastical, the bizarre, and the unusual. These sorts of yarns were considered taboo and rejected by most other fiction magazines at the time. Weird Tales explored the possibilities of supernatural occult and served up what the editors termed “highly imaginative” stories. The publication provided the opportunity for many authors to develop and some to experience their first exposure—a number went on to become regarded as founding fathers of modern day horror and fantasy fiction. Through the pages of Weird Tales and magazines of that ilk, Matt was introduced to such great authors as Robert Bloch, August Derleth, Robert

E. Howard, Edmond Hamilton, Fritz Leiber, Otis A. Kline, C.L. Moore, Jack Williamson, and dozens of other writers who would inspire the young artist to create nightmarish visions in his own work for the rest of his life.

At some point Matt and his family moved to 339 East 118th Street, and it was in that apartment where Matt saw a ghostly apparition enter his room while he was awake. Many years later, at the age of 68, the artist put his account to paper with pen-&-ink and titled it, “I have seen this intruder.” Matt soon developed a great love for nature, and early on told his family he wanted to live in the country and get away from the noisy and dirty city life of New York.

Matt’s sister, Rose, married Joseph Van Wees, on May 23, 1931, and moved to an apartment on Bolton Avenue in the Bronx. A few years later, in 1935, Matt, still living with and now caring for his elderly mother, also moved to that borough to be closer to his sister and her husband. The new address was 1640 Washington Avenue. Although no official record could be found, it appears Matt’s mother, Minnie, passed away sometime in the mid- to late-1930s, an assumption based on a pencil drawing found in the artist’s estate depicting Minnie reading a newspaper with a magnifying glass. The drawing, signed and dated, “Matt Fox ’37,” has an inscription: “Minnie Fox—My dear departed mother.”

When the Flash Gordon Sunday newspaper strip came along in 1934, Matt was so taken with the drawing skills of Alex Raymond, he’d eventually claim Raymond’s work was a main influence on his own art. Matt’s interest in the subjects of

Artwork © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions.

Artwork © the Matt Fox estate and EC Fan-Addict Productions.

fantasy, science-fiction, and the macabre, was reflected in most of his work throughout his life. Halloween was his favorite holiday, and Matt always took special interest in that celebration and the decorations that accompanied it.

It wasn’t long before brother-in-law Joseph, who worked as a professional engraver, was teaching Matt the technique of creating etchings. Working in the printing business as well, Matt was able to master the art of producing woodcuts, lithograph prints, and finely detailed etchings. In 1939, the American Museum of Natural History compiled a six-photo display showing 33-year-old Matt Fox enacting the six different stages of etching printing. Each photo measured 16" x 20" for the large display. One of the only surviving photos is reproduced in this book for the first time, on the next page.

Weird Tales and other science-fiction and fantasy type magazines provided a great escape for Matt who, through their pages, became exposed to talented other artists illustrating these type of stories. Here he found the beautiful color covers and interior black-&-white illustrations of such greats as Hannes Bok, Margaret Brundage, Lee Brown Coye, Virgil Finlay, Boris Dolgov, Frank R. Paul, and J. Allen St. John, to name a few. According to science-fiction fantasy historian Sam Moskowitz, Weird Tales’ pay rates were similar to other pulp magazines of the time, paying as much as $50 for a cover painting. Black-&-white illustrations were bought much cheaper at $8, $10, and $12 each, depending on how extensive the illustration had to be—i.e., a single title page or two-page spread. Weird Tales offered those rates until its 1954 demise.

By 1940, Matt had decided that horror and fantasy illustration work had become his calling in life. He ventured out to become a full-fledged “freelance artist.” This didn’t always provide enough money for him and the family, so to help make up the difference, he also took a job as a sheet metal worker.

Matt’s imagination knew no boundaries when it came to visualizing the elements of horror and fantasy, and eventually he connected with leading pulp magazines of the day. His earliest documented published work appears to be an illustration created for “Phantom From Space,” written by John Russell Fearn, and published in the first issue of Super Science Stories, dated March 1940. Next, he turned out a double-page illustration for one of Issac Asimov’s earliest stories, titled “The Callistan Menace,” and published in the April 1940 issue of Astonishing Stories.

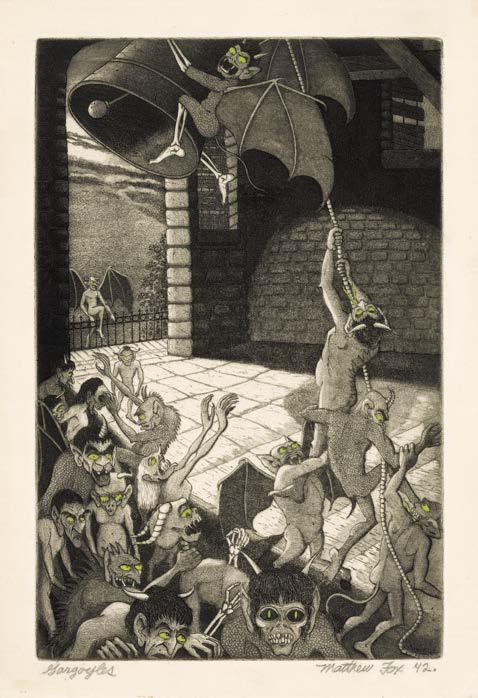

In 1942, Matt produced one of the most detailed horrific etchings of his career. This signed and dated etching, until now, has remained unpublished and buried in the Fox family archives since its creation. Only two signed prints of this work were found in Fox’s estate. This amazing black-&-white image titled “Gargoyles” (see page 19), depicts a horde of winged

and skeleton-like demons and creatures ringing a large bell in the moonlight of darkness. It is one of the most beautifully horrific etchings that Fox ever imagined, let alone engraved to a metal plate. One cannot imagine the hours it must have taken him to etch this image. To give the piece an added jolt, the artist carefully applied a yellowish-green watercolor tint to the eyes of the demons, giving them an extra three-dimensional, glow-in-the-dark sort of eeriness.

Fox contributed to Fiction House’s Planet Stories in late 1942, just before joining the U.S. Army in January 1943. He enlisted under the warrant officer program, hoping to get assigned to the Philippines. Unfortunately, due to colitis, his legs just weren’t strong enough to carry on in the military fashion Uncle Sam expected. By December, he received a medical discharge and was soon back home in the print shop, producing etchings and looking for commercial art jobs.

In early 1943, Matt landed his first Weird Tales assignments. One illustration was for a story by August Derleth titled “No Light For Uncle Henry,” and another for a poem, written by

Joseph C. Kempe, titled “Frost Demons;” both appearing in the March 1943 issue. Weird Tales would become Fox’s permanent home for his work over the next eight years, as he turned out numerous illos for stories and poems by well-known authors. In Fall 1944, Matt finally got the chance to do a cover painting for the magazine. His first effort, depicting three very strange creatures—one with tentacles, and two playing flutes— was based on a scene out of “The Dweller In Darkness,” written by Derleth, published on the November 1944 cover. Between November 1944 to July 1951, Fox would produce a total of 12 Weird Tales covers and 40 interior illustrations. These works remain some of his most inspired and detailed renditions of horror and fantasy, featuring a vast array of creatures, demons, bats, witches, unicorns, and demonic people of all sizes and shapes. Matt seemed to have a special fondness for inserting devilish-horned demons and flying bats onto many of his covers, most of which were simply done on speculation, hoping that the editor would be interested enough to buy it. Only four of his covers actually depicted stories from inside the respective issue. While some may view these covers as having a crude or unpolished look in comparison to other Weird Tales covers, Fox’s creations had a charm and

sophistication of “weirdism” that attracted readers. Obviously, his drawing of the human form was lacking in comparison to other artists’ work, but Fox more than made up for that with his bizarre, colorful visualization of demons and like creatures. His imagination ran rampant through shadowy graveyards and moonlit fields filled with dancing ghosts and demons of all description. Humans were not often depicted on Fox covers, unless they were dead, ghostly, or puppets on strings controlled by the hands of winged devils.

While Matt’s interior work may have lacked the refinement of a Virgil Finlay or Hannes Bok illustration, he always had a firm grip on the subject at hand and never lacked in effort or detail. Applying a unique blend of art inking techniques, such as stipple, crosshatching linework and charcoal pencil shading, Fox was able to translate the images from his head to the paper in a successful manner. In most cases, he utilized pebble-board art paper—commonly used by pulp magazine artists in those days— which offered an added degree of textural shading depth to an illustration when charcoal pencil was applied. On others, Matt would apply pen-&-ink and do the linework, then painstakingly stipple all over the piece for shading. Obviously he was a

mag’s editor and designer, Bhob Stewart, was introduced to Matt during a visit the artist made to Beck’s home. Many years later, Bhob wrote a blog entry recalling his meeting:

“Fox came across as a straight-arrow, no-nonsense sort of a guy, and after a brief conversation about Weird Tales, he quickly got to the point. He was selling glow-in-the-dark posters, and he wanted to run an ad in Castle of Frankenstein With that, he unfurled his glowing poster depicting demons and banshees dancing in the pale moonlight. We took it into a dark corner of the room, and yes, indeed, it did emit an eerie green glow. He next produced an ad for the posters. He had made a negative Photostat of his ink drawing, so the reversal of black-&-white simulated glowing monsters coming out of the darkness toward the reader. Clever hand-lettering effects added a subtle suggestion of glowing letters seen at night.

“The style Fox used on this half-page ad fit in very nicely with the type of art that we occasionally ran in the magazine. I showed Fox how department headings were not permanent, but alternated artwork by different artists. Then I suggested that he create some similar headings. He said, ‘Sure, I’ll do those.’ Calvin was grinning and nodding enthusiastically. The idea of having a few contributions by a Weird Tales illustrator was a nice addition, but in retrospect, I have to wonder why Cal didn’t have Fox create a series of Castle of Frankenstein covers as outré as the ones he had painted for Weird Tales. If Cal felt

Fox’s art was not in keeping with a film magazine, then he could have given him space on the back cover as we had done with Hannes Bok. Given several odd incidents that ended with artists being underpaid by Cal, I can speculate that perhaps Cal offered Fox so little money that he refused to do a painting.”

Matt Fox’s ad for the glow-in-the-dark prints ran on the last interior page of Castle of Frankenstein #8 [1966]. That issue also featured Fox’s header design for the “Ghostal Mail” section, showing several typical Fox creatures looking on as Dracula and Frankenstein peruse through the letters received from readers. This header art and the ad for the posters were repeated in #9 [Nov. 1966], and #10 [Feb. 1967] saw the glowin-the-dark prints ad dropped, while the “Ghostal Mail” header was still used. Later that year Beck issued the 1967 Castle of Frankenstein Annual, which repeated the “Ghostal Mail” header and featured a new Matt Fox header for a review column of science-fiction fanzines. It was the last issue offering the glowin-the-dark posters.

Bhob Stewart went on to recall: “On that Saturday Fox arrived to drop off that cemetery illustration, it was the second time I saw him. I admired his tight rendering in ink and crayon on pebble board. Then I casually asked, ‘So how many orders did you get for the glow-in-the-dark posters?’ He responded bitterly, ‘None.’ After that day, I never saw him and his demonic entourage again.”

#15 [Apr. 1953]. From the collection of Stephen Fishler.

#15 [Apr. 1953]. From the collection of Stephen Fishler.

“The

“Dracula Moonlight” original art [undated].

As mentioned in the biographical essay, Matt Fox’s sister, Rose, married Joseph Van Wees in 1931 and settled in the Bronx, where they raised their two children, Lillian Marie and Ronald David. Ronald joined the U.S. Army’s 179th Infantry 45th Division, serving overseas during the Korean War, and the 22-year-old went missing in action on Nov. 30, 1950, and officially listed as dead in 1953. He was posthumously promoted to corporal and awarded the Purple Heart and the Silver Star, with the accompanying citation describing Ronald’s bravery under fire. New York’s Daily News noted, “The citation said that Ronald had volunteered for an assault on a firmly entrenched enemy hilltop position at Songnaedong, Korea. It added that he had helped a fallen buddy as much as he could, and then proceeded ‘with blazing rifle into the enemy’s secondary position.’”

Subsequently, Rose became convinced that her son was still alive after seeing him among other American POWs in a photo in Life magazine, and so began her lifelong crusade to demand the government be accountable for U.S. servicemen suspected to remain in captivity. Her brother, Matt, shared his talents for her cause and he submitted vehemently anti-Communist cartoons to newspapers, including New Hampshire’s Manchester UnionLeader, which included this biographical caption: “Matthew Fox, the able artist of this drawing, knows well of Communist brutality. His nephew is a prisoner in a Communist China slave camp.”

Illustration [1975].

Artwork

Illustration [1975].

Artwork

Adventures into Terror #19 [May 1953]

“Meet the Bride”—5 pages

Adventures into Terror #25 [Nov. 1953]

“The Terrible Trophy”—5 pages

Adventures into Weird Worlds #10 [Sept. 1952]

“Down in the Cellar”—5 pages

Adventures into Weird Worlds #21 [Aug. 1953]

“Romanov’s Rumour”—5 pages, inks over John Forte

Adventures into Weird Worlds #27 [Mar. 1954]

“The Thieves”—4 pages

Astonishing #23 [Mar. 1953]

“The Woman in Black”—4 pages, inks over unknown artist

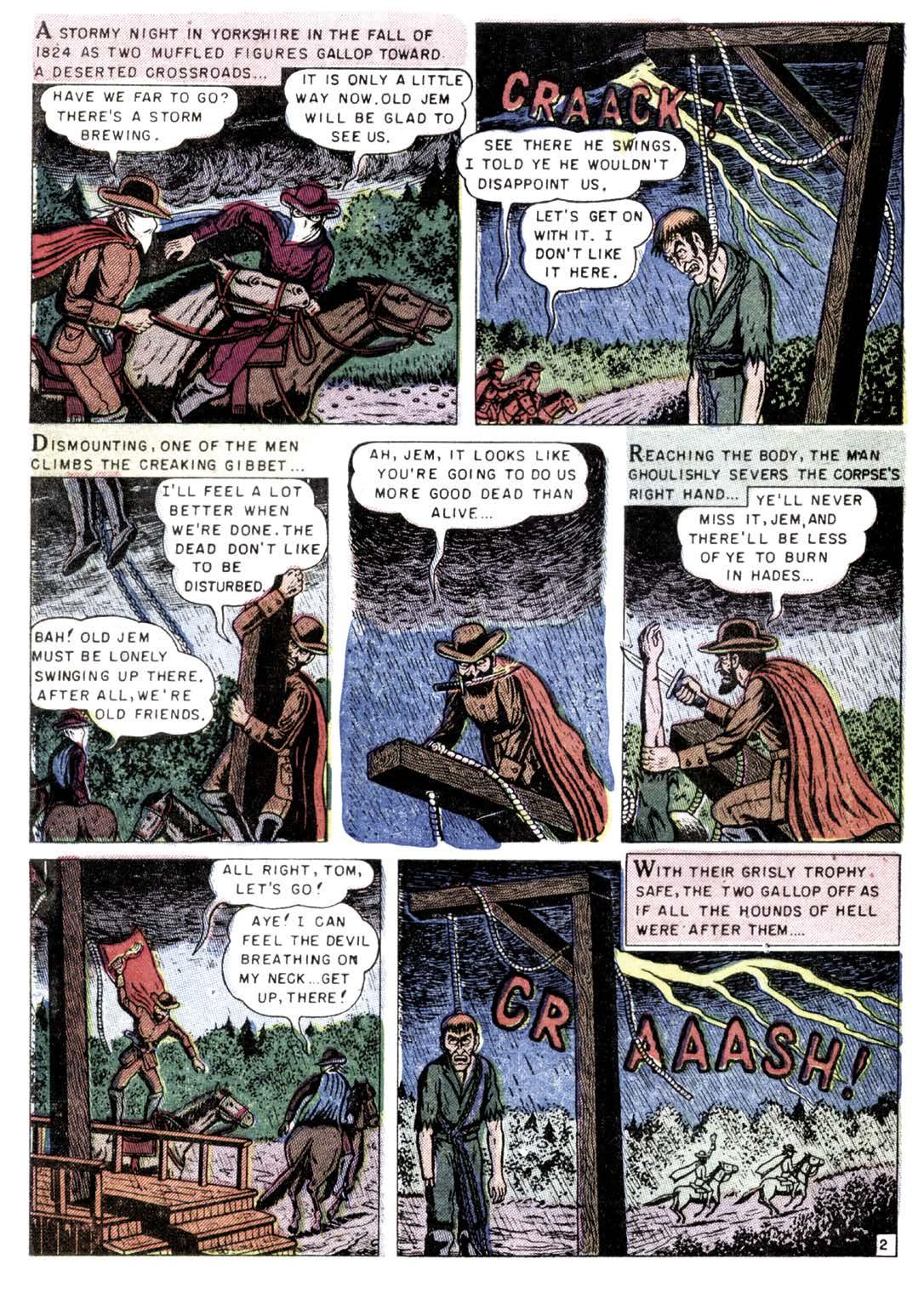

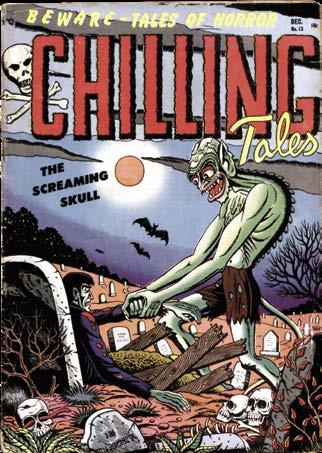

Chilling Tales #13 (first comic-book work) [Dec. 1952]

“The Hand of Glory”—cover and 7 pages

Chilling Tales #15 [Apr. 1953]

Cover

Chilling Tales #17 [Oct. 1953]

Cover

Journey into Mystery #49 [Nov. 1958]

“The World-Destroyers”—3 pages

Journey into Mystery #93 [June 1963]

Journey into Unknown Worlds #19 [ June 1953]

“Beelzebub”—5 pages

Journey into Unknown Worlds #21 [Aug. 1953]

“The Dead of Winter”—5 pages

Journey into Unknown Worlds #22 [Sept. 1953]

“Too Timid to Live”—5 pages, inks over Forte

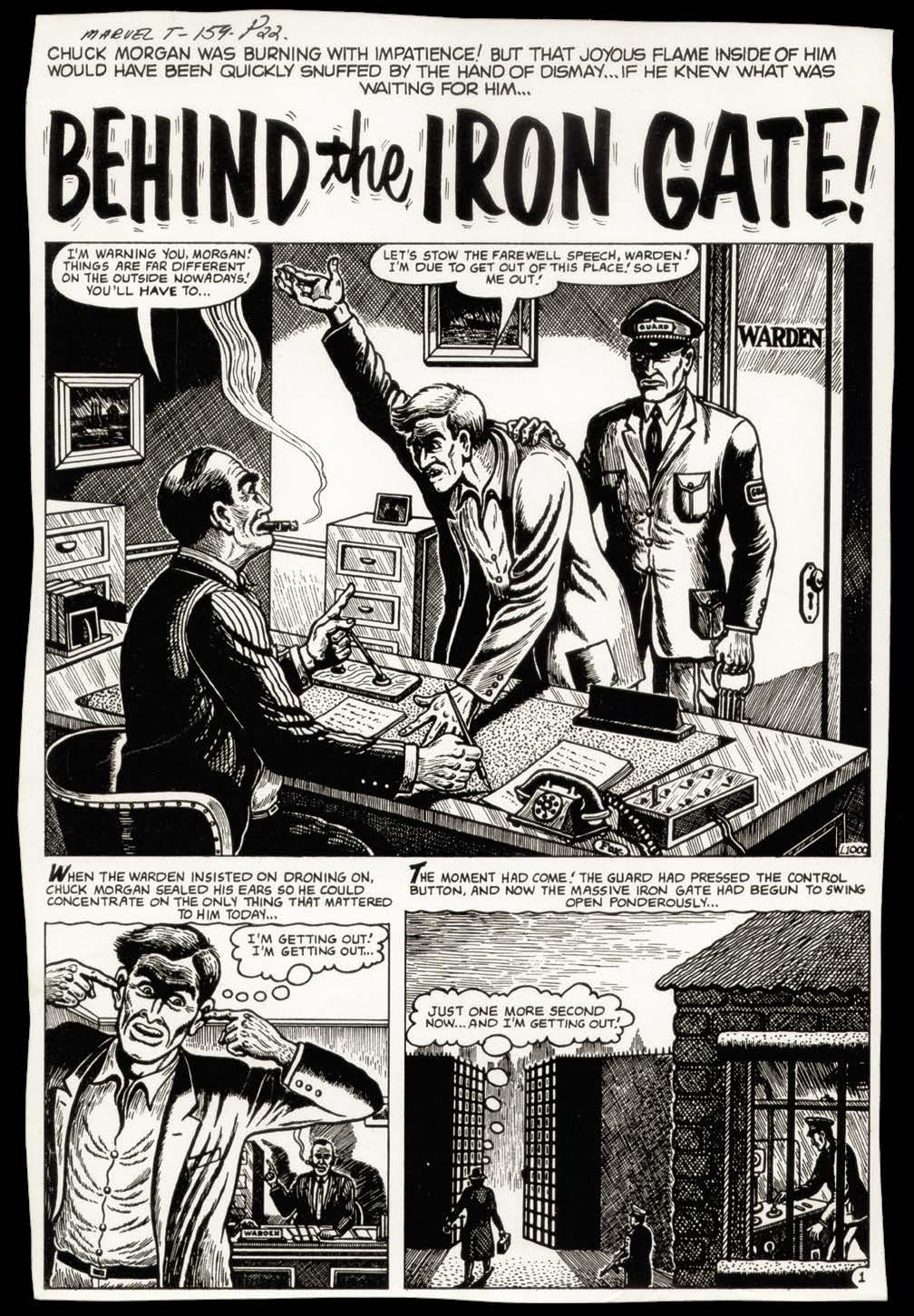

Marvel Tales #159 [Aug. 1957]

“Behind the Iron Gate!”—3 pages

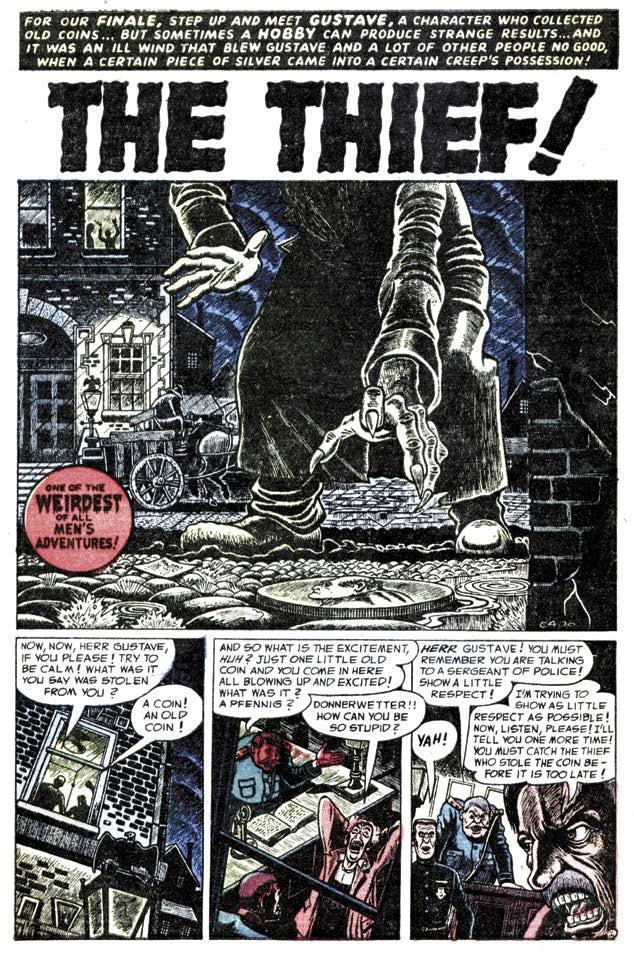

Men’s Adventures #23 [Sept. 1953]

“The Thief”—5 pages

Mystery Tales #12 [May 1953]

“Never Say Die”—4 pages

Mystery Tales #21 [Sept. 1954]

“Hate”—4 pages

Mystery Tales #22 [Oct. 1954]

“The Tiny Coffin”—cover and 4 pages

Mystic #24 [Oct. 1953]

“The Stranger from Space”—4 pages, inks over Gil Kane

Spellbound #16 [Aug. 1953]

“Only a Rose!”—5 pages

“The Man Who Wouldn’t Die!”—5 pgs., inks over Larry Lieber

Journey into Mystery #98 [Nov. 1963]

“The Purple Planet!”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Journey into Mystery #99 [Dec. 1963]

“Stroom’s Strange Solution!”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Journey into Mystery #100 [Jan. 1964]

“The Unreal!”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Journey into Mystery #101 [Feb. 1964]

“The Enemies!”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Journey into Mystery #102 [Mar. 1964]

“The Menace!”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Journey into Unknown Worlds #18 [May 1953]

“Dugan and the Dummy”—5 pages

Strange Stories of Suspense #16 [Aug. 1957]

“The Missing Sun”—3 pages

Strange Tales #18 [May 1953]

“Witch Hunt!”—5 pages

by ROGER HILL

Strange Tales #22 [Sept. 1953]

“Too Good to be True!”—4 pages, inks over Forte

Strange Tales #110 [July 1963]

“We Search the Stars”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Strange Tales #111 [Aug. 1963]

“Beware the Machine”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

#113 [Oct. 1963]

“The Search for Shanng”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

Tales of Suspense #42 [ June 1963]

“Escape into Space”—5 pages, inks over Lieber

MATT FOX (1906–1988) first gained notoriety for his jarring cover paintings on the pulp magazine WEIRD TALES from 1943 to 1951. His almost primitive artistry encompassed ghouls, demons, and grotesqueries of all types, evoking a disquieting horror vibe that no one since has ever matched. Fox suffered with chronic pain throughout his life, and that anguish permeated his classic 1950s cover illustrations and his lone story for CHILLING TALES, putting them at the top of all pre-code horror comic enthusiasts’ want lists. He brought his evocative storytelling skills (and an almost BASIL WOLVERTON-esque ink line over other artists) to ATLAS/MARVEL horror comics of the 1950s and ’60s, but since Fox never gave an interview, this unique creator remained largely unheralded—until now! Comic art historian ROGER HILL finally tells Fox’s life story, through an informative biographical essay, augmented with an insightful introduction by FROM THE TOMB editor PETER NORMANTON. This FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER also showcases all of the artist’s WEIRD TALES covers and interior illustrations, and a special Atlas Comics gallery with examples of his inking over GIL KANE, LARRY LIEBER, and others. Plus, there’s a wealth of other delightfully disturbing images by this grand master of horror—many previously unpublished and reproduced from his original paintings and art—sure to make an indelible imprint on a new legion of fans

(128-page COLOR HARDCOVER) $29.95 • (Digital Edition) $15.99 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-120-2

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=95_94&products_id=1711

Comic book and pulp magazine artist Marcy Matthew Fox [1906–1988] first developed a cult of admirers with his peculiar stylings as illustrator for Weird Tales between 1943–51, and then was noted for his gruesome, almost primitive art on Stan Lee’s line of horror titles at Atlas Comics in the ’50s. Yet most might remember Matt Fox as the idiosyncratic, hyper-detailed inker over Larry Lieber’s pencils on sci-fi stories in the early Marvel Comics—and whose work seemed to all but vanish by 1964. But, as you will find in this captivating look at the artist’s life and work, Fox’s finest achievements were still ahead!

For the first time ever, the life of the fascinating artist is revealed by renowned historian and art aficionado Roger Hill, who shares his amazing collection of Fox art—much of it unpublished until now—and other rarities the author has accumulated over the decades.

THE CHILLINGLY WEIRD ART OF MATT FOX includes:

All of Fox’s Weird Tales covers and interior illustrations

• Fox’s very first comic book story

• Over 25 pages of previously unpublished Fox artwork

• Never-before-seen Fox photos, early work, etchings, and rare editorial cartoons • Plus an introduction by From the Tomb editor Peter Normanton

Raleigh, North Carolina