3 minute read

Photoreceptor Misplacement During Retinal Development Implicated in IRDs

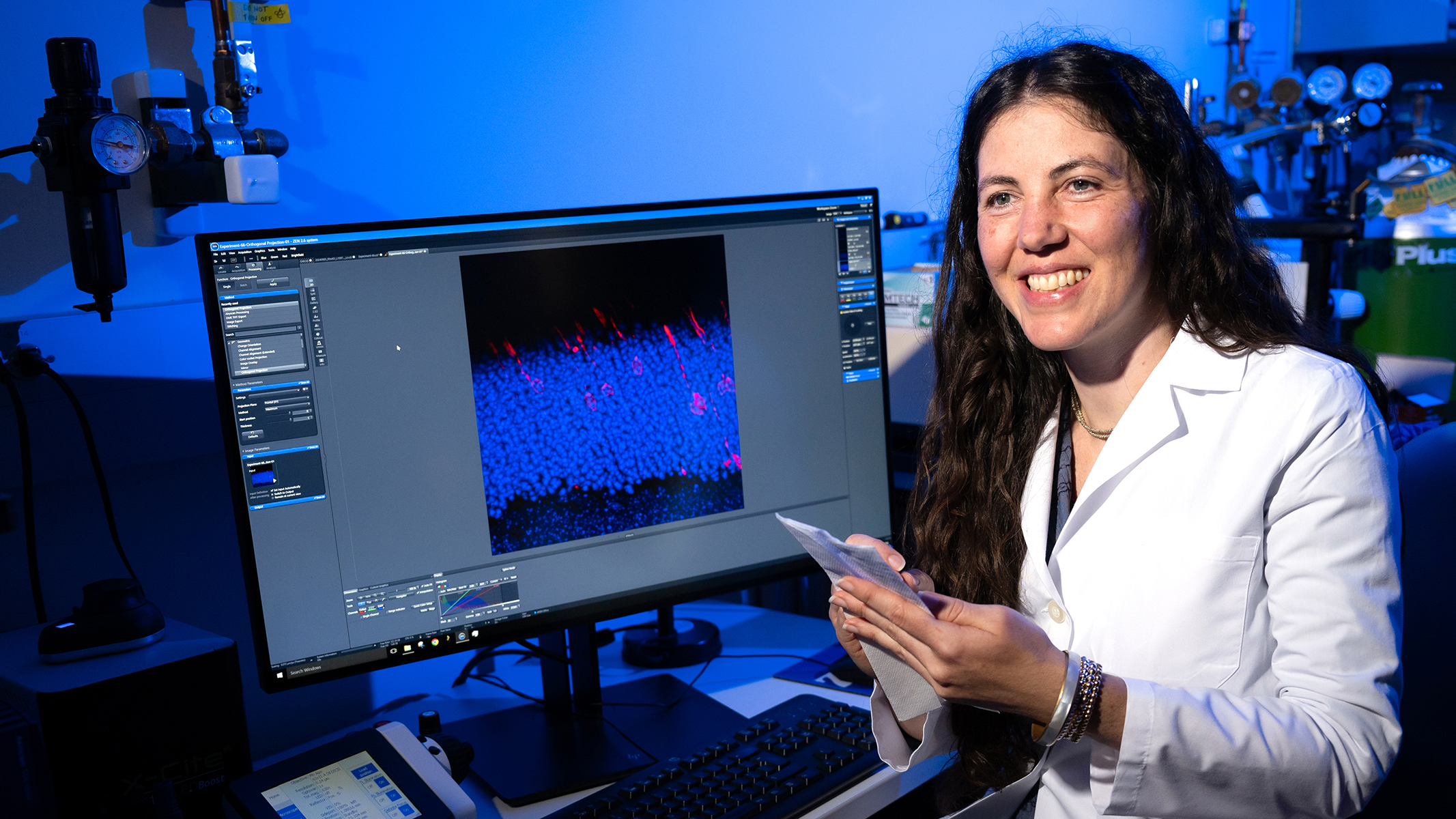

The primary focus in the lab of molecular biologist Jillian Pearring, Ph.D., is studying the light-sensitive photoreceptor cells of the retina, and how defects in their formation, function or trafficking drive blinding inherited retinal diseases (IRDs).

Recently, the Pearring lab identified a new culprit: a disruptive phenomenon occurring in the structure of the retina linked to mutations in the gene Arl3. Two research awards announced in 2024 will fund further studies to better understand this event and its potential relevance as a therapeutic target.

The light-sensing neural tissue of the retina is composed of layers. Neurons communicate across those layers, sending information from the photoreceptor cells that reside in the outermost layer. Dr. Pearring has demonstrated how mutations in the Arl3 gene can cause the Arl3 protein to become hyperactive. This overactivity, which occurs during the development of the retina, results in photoreceptors being stranded in the inner retinal layers, unable to reach their destination in the outer layer.

Dr. Pearring first connected overactive Arl3 with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa and wondered whether the phenomenon might also play a role in other IRDs. To find out, her team zeroed in on another gene, RP2. RP2 is associated with the IRD X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, and has a known connection to Arl3, making it a good target for study.

“RP2 is known to turn off Arl3 activity,” she explains. “We were able to demonstrate that decreasing RP2 function would pave the way for increased Arl3 activity. Furthermore, in models with mutations in either Arl3 or RP2, we observed the same phenomenon— elevated Arl3 activity combined with photoreceptor misplacement.”

Two aspects of these findings have the potential to change the paradigm for IRDs.

First, they move beyond linking genes to specific IRDs to focus on patterns of cellular activity shared by different IRD genes. Second, the phenomenon of Arl3 hyperactivity occurs early in life, during the fetal stage of retinal development, not later as a consequence of disease.

This new vantage point could change how—and how early—these progressive diseases are identified and treated. Dr. Pearring has been awarded both an NIH R01 grant and a grant from the Foundation Fighting Blindness, to pursue complementary aspects of this pivotal finding.

The Pearring lab will test several techniques for suppressing or corralling Arl3 to determine whether there is an approach that will prevent photoreceptors from being stranded in inner retinal layers. In both neonatal and adult disease models, they will also attempt to determine the available time windows to restore photoreceptors to their proper location in the outer layer.

“We are excited to build on these preliminary findings,” says Dr. Pearring. “We hope to describe how mis-localized photoreceptor cells impact retinal health and function, learn more about the cellular mechanisms of Arl3 and RP2 mutations, and eventually identify new therapeutic targets for inherited blindness.”