2 minute read

In Choroideremia, is the RPE on Defense, or Offense?

A key area of focus in inherited retinal disease (IRD) research is dysfunction in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a layer of cells located between photoreceptors (PRs)—the cells that sense vision—and the structure that supplies blood to the retina, called the choroid. Although the RPE is not the source of vision, it nonetheless plays a vital, defensive role, guarding the health and survival of both PRs and the choroid.

Choroideremia is an IRD estimated to strike approximately one in 50,000 patients, predominantly men. Typically diagnosed in childhood, it usually leaves patients legally blind by early adulthood. Like other IRDs, it results in retinal degeneration. But, as its name suggests, the feature that sets it apart is the severity of degeneration sustained by the choroid.

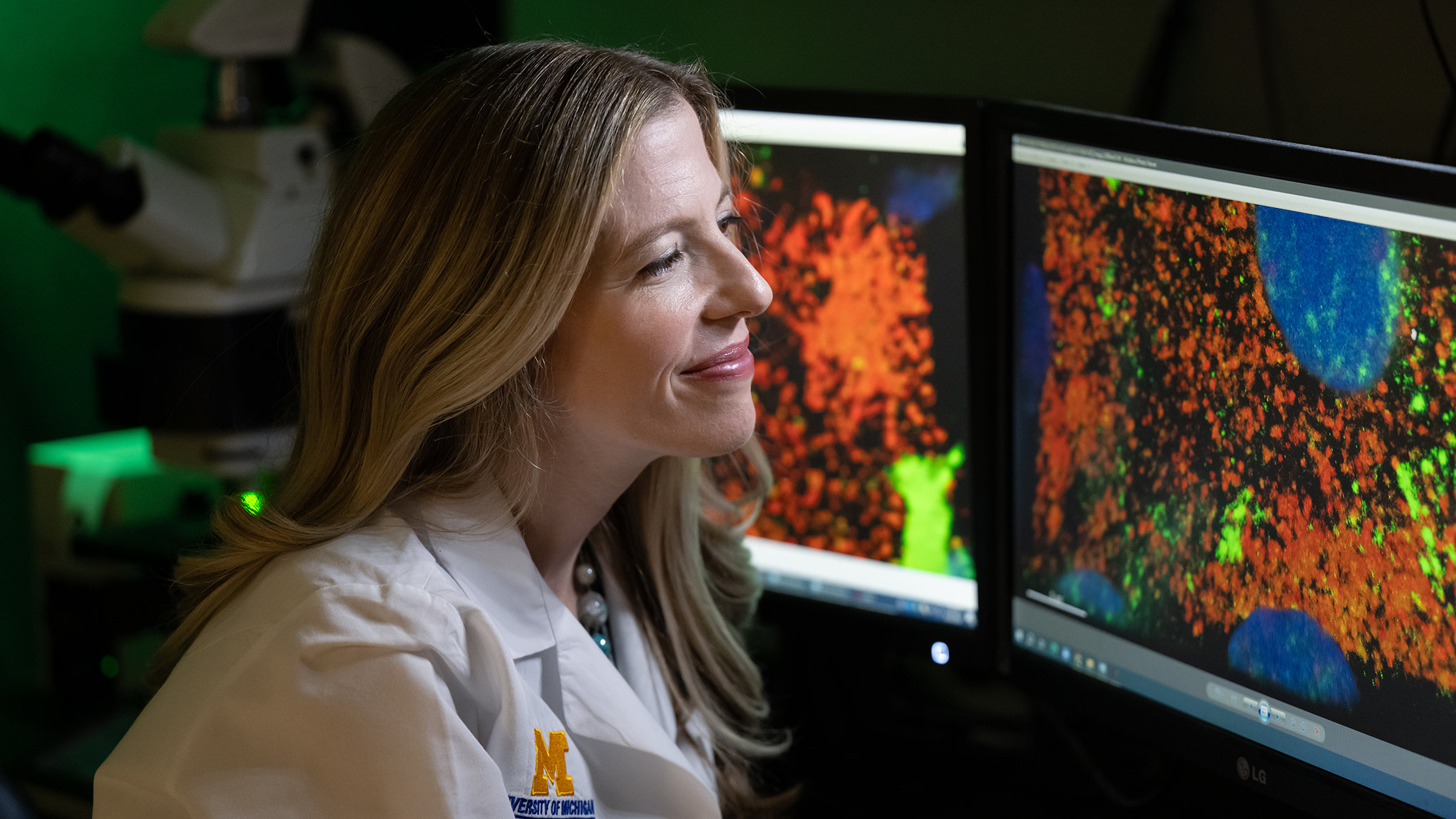

Kellogg clinician-scientist Abigail Fahim, M.D., Ph.D., is pursuing a new theory of the role of the RPE in choroidal degeneration. Her work is supported by a 2024 NIH R01 grant.

“We know that genetic mutations can target and destroy RPE cells, leaving the choroid unsupported,” she explains. “We’ve long attributed choroideremia to this ‘passive’ consequence of RPE cell death. But what if something in the RPE is also playing an active, offensive role in injuring the choroid?”

In order to do their job, RPE cells are prolific secreters of various proteins, including a specific type called a protease. Like molecular scissors, proteases are capable of cutting up adjacent cellular structures.

“Our preliminary studies of choroideremia models showed additional secretion and activity of certain proteases,” notes Dr. Fahim. “Others have previously associated RPE proteases with age-related changes like choroidal thinning and macular degeneration. We now hypothesize that increased protease activity could actually be snipping away at the scaffold-like structure of the choroid.”

Dr. Fahim employed a number of advanced gene editing and molecular biology tools to arrive at this theory, including CRISPR/Cas-9, Tandem mass tag (TMT) spectrometry, RT-PCR, ELISA, gel zymography, and immunofluorescence. She will employ them again to test it. She also uses stem cells derived from human skin to generate RPE cells with the choroideremia genetic defect. These induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are a powerful tool to study genetic diseases in a cell culture dish.

“If we can connect RPE-secreted proteases with the severe choroidal atrophy that characterizes choroideremia, it may prove a promising therapeutic target for this untreatable disease,” she says.