SP R IN G 2015

UNIVERSIT Y OF ALBERTA

ALUMNI MAGA ZINE

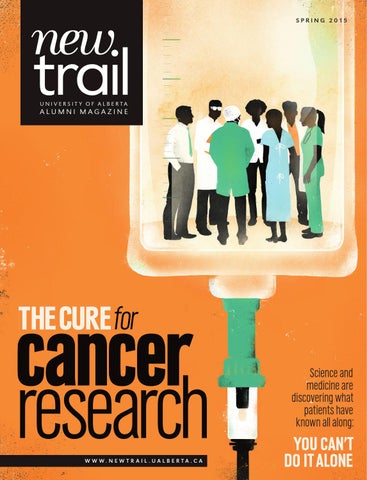

THE CURE for

cancer research W W W.NEW TR AIL .UALBERTA .C A

Science and medicine are discovering what patients have known all along:

YOU CAN’T DO IT ALONE

Chart the best course for your life in the years ahead. Start with preferred insurance rates.

On average, alumni who have home and auto insurance with us save $400.*

Home and auto insurance program recommended by

Celebrating a Century of Achievement!

Supporting you... and the University of Alberta. Your needs will change as your life and career evolve. As a University of Alberta Alumni Association member, you have access to the TD Insurance Meloche Monnex program, which offers preferred insurance rates, other discounts and great protection, that is easily adapted to your changing needs. Plus, every year our program contributes to supporting your alumni association, so it’s a great way to save and show you care at the same time. Get a quote today! Our extended business hours make it easy. Monday to Friday: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturday: 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

HOME | AUTO | TRAVEL

Ask for your quote today at 1-888-589-5656 or visit melochemonnex.com/ualberta The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex program is underwritten by SECURITY NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY. It is distributed by Meloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebec, by Meloche Monnex Financial Services Inc. in Ontario, and by TD Insurance Direct Agency Inc. in the rest of Canada. Our address: 50 Place Crémazie, Montreal (Quebec) H2P 1B6. Due to provincial legislation, our auto and recreational vehicle insurance program is not offered in British Columbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *Average based on the home and auto premiums for active policies on July 31, 2014 of all of our clients who belong to a professional or alumni group that has an agreement with us when compared to the premiums they would have paid with the same insurer without the preferred insurance rate for groups and the multi-product discount. Savings are not guaranteed and may vary based on the client’s profile. ® The TD logo and other TD trade-marks are the property of The Toronto-Dominion Bank.

S P R I N G 2015 V O L U M E 71 N U M B E R 1

On the cover: Cancer research today brings together experts from fields as diverse as nutrition, computer science and health law in the quest to bring better diagnosis and treatment to patients. Read more on page 18. Illustration by Sébastien Thibault

features 18

18 Teaming Up to Conquer Cancer

Researchers are speeding discovery by breaking down barriers and finding allies in unexpected places

30

30 Minds Without Borders

The value of diversity goes deeper than the obvious; it can be a source of innovation and creativity

36 It Takes a Global Village

As Indira Samarasekera’s presidency ends, she ponders an international legacy — and time with her grandchild

36

NE W TR AIL .UALBERTA .C A

Supervising Editors Mary Lou Reeleder Cynthia Strawson, ’05 BA, ’13 MSc, Editor-in-Chief Lisa Cook, @NewTrail_Lisa Managing Editor Karen Sherlock Associate Editor Christie Hutchinson Art Director Marcey Andrews Senior Photographer John Ulan Digital Editor Karen Sherlock New Trail Digital Shane Riczu, ’12 MA, Ryan Whitefield, ’10 BA, Joyce Yu, ’07 BA Staff Writers Amie Filkow, Sarah Pratt, Bridget Stirling Proofreader Sasha Roeder Mah Advisory Board Anne Bailey, ’84 BA; Jason Cobb, ’96 BA; Susan Colberg, ’83 BFA, ’91 MVA; Glenn Kubish, ’87 BA(Hons); Kiann McNeill; Robert Moyles, ’86 BCom; Julie Naylor, ’95 BA, ’05 MA CONTACT US Email (Comments/Letters/Class Notes) alumni@ualberta.ca Call 780-492-3224; toll-free 1-800-661-2593

44

departments

Mail Office of Advancement, University of Alberta, Third Floor, Enterprise Square, 10230 Jasper Ave., Edmonton, AB T5J 4P6

3

Your Letters Our Readers Write

4

Bear Country The U of A Community

Facebook U of A Alumni Association

14

Whatsoever Things Are True Column by Todd Babiak

Twitter @UofA_Alumni

16

Continuing Education Column by Curtis Gillespie

40

Question Period Pam Ryan on libraries of now and tomorrow

Address Updates 780-492-3471; toll-free 1-866-492-7516 or alumrec@ualberta.ca

42

What’s Brewing Column by Greg Zeschuk

44

Books Alumni Share Their New Work

48

Events In Edmonton and Beyond

50

Class Notes Keeping Classmates up to Date

61

In Memoriam Bidding Farewell to Friends

64

Photo Finish The Picture-Perfect Finale

TO ADVERTISE lesley.dirkson@ualberta.ca This University of Alberta Alumni Association magazine is published three times a year. It is mailed to more than 180,000 alumni and non-alumni friends, and is available on select newsstands. The views and opinions expressed in the magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Alberta or the U of A Alumni Association. All material copyright ©. New Trail cannot be held responsible for unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. ISSN: 0824-8125 Copyright 2015 Publications Mail Agreement No. 40112326 If undeliverable in Canada, return to: Offi ce of Advancement University of Alberta, Third Floor, Enterprise Square 10230 Jasper Ave. Edmonton, AB T5J 4P6

newtrail spring 2015

1

OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS

Robert Moyles, ’86 BCom Interim Associate Vice-President Tracy Salmon, ’91 BA, ’96 MSc Director, Alumni Programs Kara Sweeney Director, Alumni Engagement Coleen Graham, ’88 BSc(HEc), ’93 MEd Senior Manager, Strategic Initiatives

ALUMNI COUNCIL EXECUTIVE President Glenn Stowkowy, ’76 BSc(ElecEng) President-elect Mary Pat Barry, ’04 MA Executive Member at Large Ron Glen, ’89 BA(Spec), ’04 MBA Vice-President: Affinity Chris Grey, ’92 BA, ’95 MBA Vice-President: Centenary Wanda Wetterberg, ’74 BA(RecAdmin) Vice-President: Communications Glenn Kubish, ’87 BA(Hons) Vice-President: Education Charlene Butler, ’09 MBA Vice-President: Histories & Traditions Jason Acker, ’95 BSc, ’97 MSc, ’00 PhD, ’09 MBA Vice-President: Students Sheena Neilson, ’06 BSc(Pharm) Vice-President: Volunteers Tom Gooding, ’78 BSc(MechEng) Board of Governors Representatives: Jane Halford, ’94 BCom Rob Parks, ’87 BEd, ’99 MBA Senate Representatives Cindie LeBlanc, ’01 BA Sunil Agnihotri, ’05 BA, ’12 MA

Graduate Studies Chris Grey, ’92 BA, ’95 MBA Law Ian Reynolds, ’91 BCom, ’94 LLB Medicine Vacant Native Studies Carolyn Wagner, ’06 BA(NativeStuHons) Nursing Keith King, ’04 BScN Pharmacy Sheena Neilson, ’06 BSc(Pharm) Physical Education and Recreation Wanda Wetterberg, ’74 BA(RecAdmin) Public Health Paul Childs, ’05 MPH Rehabilitation Medicine Linda Miller, ’89 BSc(OT) Science Fred Johannesen, ’84 BSc(Spec) Members at Large Darryl Lesiuk, ’87 BA, ’91 BCom, ’07 MBA Jessa Aco, ’14 BCom Ken Bautista, ’99 BEd David Johnston, ’94 BA Ayaz Bhanji, ’91 BSc (Pharm) Emerson Csorba, ’14 BA(Spec) Della Lizotte, ’10 BA(NativeStu) Christine Causing, ’97 BA Julie Lussier, ’11 BCom Nick Dehod, ’11 BA Steven Dollansky, ’09 BSc, ’12 JD Amy Shostak, ’07 BA EXCEL’85 BCom Kevin OFFEEXXCCEELLLL OF Higa, L EO E LE LEL River Wilson, ’01 BA, ’06 MSc(RehabMed) SILVER SILVER SILVER

upfront

C

CI R

M

C

C

C

CI R

CI R

M

M

M

A

A

A

CI R

CL

CL

M

CIR C

M

A

M

A

CIR

M

M

A

A

M

A

2014

M

CIR A CMLM

CIR

M

M

A

A

M

A

CL

CIR

CIR A C M

CIR

CL

M

M

A

A

AR

A

CL

CL

CIR

CIR

C

M

CL

CIR

M

A

CIR

#2 - Taken apart. shows globe and line options in gray -- #4 does this as well. thicker globe line on 2 & 3. fewer teeth on 3

M

M

M

M

A

A

A

CIR A CIC R M

M

A

A

CI R

M

A

A M M M

A M M A M MM

CI CIR CIRRC C C

M

M

A

M

A

A CI R CM

M

M

A

A

M

A

CL

A

CL

CIR

C

C I R AM CMLM CIR CL

CL

CIR

AM M

MM

A

C

C

MM

A

CL

CL

CIR

CIR

C

CI R

CI R

CL

CL

CIR

CIR

M

CL

CIR

CIR

M

A

A

M

M

A

A

CICR CIIRCR

CL

M

M

A

A

M M

A

CL

CIR

CL

CL

CL

CIR

M

A M

MM

C CIRR CC CICRCIRIC ICR L

CIR

CIR

M

A

M

MM

M

A E

CI R

C

CI R

CI R

RCM M

CCIRA IC

M

A

CL

CL

CIR

C CI R C

CI R

CL

M

A

A

CIR

N

CCIRIRC C

RC

CCIR IC

M

A

C CI R C

CI R

M

CIR C

M

CIR

CIR

CIR C

C

CI R

CL

CIR

C

CI R

CL

CIR

CL

CIR

CL

M

CIR

CIC RICR C L CIR

CASE DS PR O GR

CE

2 01 4

EN

EXCEL OF L

SILVER

CE

M

EN

A AW AW

RR A OOGG SPP RR

Meta Bold in 2 & 3 center

CE EN

7/11/2014 6:32:18 PM

LE

AW

2014 CASE

Avenir heavy

R

lines 30% shape 15%

CASE CASE W A RA RD D S

E

S PROG

E CE CE NC EN EN

CEECE C EN CEEENN NC EN

EXCC ELEL OF OF EX L LE LELE EXCEL SILVER OF L LE

RD

#4 - first two logos from #3 with circle type treated similar to original COE logo

NC

A

CE EN

E AW

AW

AW

AW

AW AAWW A A

W A 2014 AARRR RGAR D DDSSSP RPO RGO W

Meta Bold in 2 & 3 center

Meta Bold in 2 & 3 #3 center - Circle text is

AW

E NCCE

CE

CE

CE

lines 30% lines shape 40% shape 15% 25%

CASE CASE CASE CASE

CASE

Avenir heavy MetaPlus medium

A R R RD RD S P RS OPGR O G

CE

N A WE

EN

AE N AW

EN

#4 - first two logos from #3 with circle type treated similar to original COE logo

CASE

spaced out closer to style of original logo. first logo is all Avenir, second logo is Stone lines 30% shape 15% Serif Semi and MetaPlus medium. Third logo is MetaBook in circle and MetaMedium in center.

EN

CE

CE

A W CE E NCEC

N A WEN

CASE

CE

CE

AW

AW

EN

EN

CE

XC XECLE E OOFFFEEX LL EO EL LLEE F EEXCCEELLL SILVER EOOF LE L E C L

CASE

#4 - first two logos from #3 with circle type treated similar to original COE logo

EN

EN

CE

CE

CE

Meta Bold in 2 & 3 #3 center - Circle text is

CASE

AW

CE

AW

EN

EN

CASE CASE

spaced out closer to style of original logo. first logo is all Avenir, lines 80% 60% logo is lines second Stone30%lines lines 30% lines shape 40% shape 15% 25% shape shape 40%15% shape 25% Serif Semi and MetaPlus medium. Third logo is MetaBook in circle and MetaMedium in center.

A

CE

EN

CE

AW

AW

CE

CASE

to original COE logo

CASE CASE

AW

CE

CE

EN

EN

AW

AW

EN

CE

A

EN

CE

EN

CE

CE

CE

EN

EN

EN

CASE CASE

AW

EN

EE NECNC E NC

M

#1 - fewer teeth and type in circle smaller, moved in from outlines. This is Avenir. (first logo is what was in previous pdf - just for comparison)

CASE

#3 - Circle text is spaced out closer to style of original logo. first logo is all Avenir, second logo is Stone Serif Semi and MetaPlus medium. Third logo is Meta- Taken Book in#2 circle and apart. shows MetaMedium in globe center.and line options in gray -- #4 does this as well. thicker globe line on 2 & 3. fewer teeth on 3

CASE CASE

#4 - first two logos from #3 with circle white lines white shape lines shape 20% 20%type treated similar white lines shape 20%

EN

CE

CIR

E

EN

CE

E NC AW

AW

A

AW

AW

EN

CE

AW

AW

CIRC L CIR

NC

A

EN

CE

CE

CE

AW

AW

AW CE CE

EN

CE

80% lines 40% lines shape 25%shape 60%

N

EN

EN

N

CASE

Myriad semi MetaPlus medium Avenir heavy

WINNER

#1 - fewer teeth and type in circle smaller, moved in from outlines. This is Avenir. (first logo is what was in previous pdf - just for comparison)

CASE

#3 - Circle text is spaced out closer to style of original logo. first logo is all Avenir, second logo is Stone Serif Semi and MetaPlus medium. Third logo is Meta- Taken Book in#2 circle and apart. shows MetaMedium in globe center.and line options in gray -- #4 does this as well. thicker globe line on 2 & 3. fewer teeth on 3

CASE CASE CASE CASE CASE R R RD AR S P RDO S GP R O G

CEE ENNC

AAW

EN

CASE CASE

CASE CASE

A A AW

EN

AA

A

WA A ARRD GRR DS S PPRROOG W W

CE

AW

AW

E NC

lines 80% shape 60%

CASE CASE

EN

80% lines 40% lines shape 25%shape 60%

L M AG

E EXXCCEEL LLL OOFF E LEE F EXCELLL EO EE CL

EN

AW

CE

CASE

A

R

A EE NCC EN AW

CE EN CE EN

A

AW

EN

R

I G S P RZO A

A AW

AW

W

S P RO G

AW

CE

RD

COE14_REVISED STICKER.indd 4

RD

AW

EN

CASE

WINNER

TRAI

2 newtrail.ualberta.ca CASE A

AW

CE

AW

CECE EN N

EXCE LL OF F EXCELL EO E L C

whitelines lines15% shape 20%30% shape

ITI

NG

AA

A

E

A

EW

AAW

N

E NC

AW

WR

Myriad medium semi MetaPlus

N

CASE

CASE

ER•PROFILE

CASE

AW

A CE EN

AW

CE

AW

lines 80% shape 60%

CASE CASE

Myriad semi

CE N E C

CE

EN

A

lines 15% shape 30%

WINN

EN

N

AW

AW

VER

AAW

AW

A SIL

CASE

#1 - fewer teeth and type in circle smaller, moved in from outlines. This is Avenir. (first logo is what was in previous pdf - just for comparison)

#2 - Taken #2 - Taken apart. shows apart. shows globe and line globe and line options in gray options in gray -- #4 does this -- #4 does this as well. thicker as well. thicker globe line on 2 globe line on 2 & 3. fewer & 3. fewer teeth on 3 teeth on 3 #1 - fewer teeth and type in circle #1 - fewer teeth and type in circle smaller, moved in from outlines. smaller, moved in from outlines. This is Avenir. This is Avenir. white lines white shape lines shape 20% 20% is30% white lines shape (first shape logo what was in previous (first logo is what was in previous white lines20% shape 20% white lines shape 20% lines 15% pdf - just for comparison) pdf - just for comparison)

whitelines lines15% shape 20%30% shape

lines 15% shape 30%

CASE

EE NCC EN

CE EN

It was such a simple question: What should people eat while they are undergoing cancer therapy? But 10 years ago U of A nutritional scientist Catherine Field, ’88 PhD, had no good answers. “Patients asked so many questions about nutrition during and after their treatment, but we had no science-based answers,” she told New Trail. This simple question led Field, a registered dietitian and a professor in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences, to look more closely at omega-3 fatty acids. Could omega-3s, long recognized as important nutrients, play a role in the treatment of breast cancer? The results of Field’s studies were groundbreaking: treating human breast tumours with the fatty acid before chemotherapy killed more malignant cells than the chemo alone. EEXXCCEEL team isE Onow F EXCEL pursuing trials in pre-clinical models, and she O OFF Field’s LEL LE LLEE L SILVER SILVER her findings into an answer to the original isSILVER working to translate question: dietary recommendations for patients during chemotherapy. EX OFFICIO CASE CASE CASE CASE 2014 President 2014 2014 2014 Honorary 2014 2014 It is an exciting development, and one that never would have WA W W AR A A ARR AARR AR R RA Indira D S Samarasekera DDSS PPRRO GR DSS PPRROOGGRR D DS PR O GR OG PR O G come about if Field had not been part of a translational research Interim Vice-President (Advancement) FACULTY REPRESENTATIVES collaboration with colleagues in oncology and physical education. Colm Renehan EXEX EX EX EX X EXCE Academic Representative X EC OF OF C OF OFCEOLFLCEX OF OCFEE LLELL LLCELL LL CELL OF LL O F E CELL E E E LE MBA LE LE LE LE LE LE solutions LE LE The to today’s problems are bigger than one person, Acting Dean of Students Jason Acker, ’95 BSc, ’97 MSc, ’00 PhD, ’09 SILVER SILVER SILVER Robin Everall, ’92 BA(Spec), ’94 MEd, ’98 PhD whether it is physicians and researchers working together to address Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences CASE CASE CASEGraduate CASE Association OFFEEXXCCEEL CASE CASEthe Reint Boelman, ’97 BSc(Ag) EXStudents’ C EL CEL needs of a cancer patient (page 18) or scientists from every O F EX LLLE OF O LE 2014 Susan 2014 LE LE Cake L W 2014 LELE W Arts A A A W A A A SILVER SILVER A SILVER A SILVER R R R R globe A R R DA R R R R AR R the RD A corner working together to find a better treatment for R R GR O G G R DS P DR Dof GR RPD S DPSRPORGO G SO S PD D S P R O GStudents’ Union S PROG R SO G PRO S PR O Glenn Kubish, ’87 BA(Hons) diabetes (page 30). The thorny problems of the 21st century cannot CASE CASE CASE William Lau, ’13 BSc(Nutr/Food) Augustana 2014 2014 2014 2014 WA Wbe answered by a lone researcher working late hours in a lab. They Sandra Gawad Gad, ’12 BSc AR A A A A R RRDD R RD G D S P R O G R F E XFCEEX C E GFR E XF CEEX C EXCE X CF EE X C E EX E SS PPRRO S P R OOGF E O OO F EXC OF O O O LL O OF LL LL LL L ELL ELL LL LL Business E E E E E E E L require diversity of Cbackgrounds, experiences and thought. Ea rich E Charlene Butler, ’09 MBA These are the kinds of challenges that are uniquely suited to X X X EFXC E E E C C C XCEL X F F F F E E C E E E E F O O O O O LLELL LL LL LL O Campus Saint-Jean LE E CASE CASE E LE LE LE LE LCASE LE the University of Alberta. Here we have philosophers, engineers, Marty McKeever, ’02 BEd SILVER SILVER A A A A A A A A A R R R R R R R R RD R R D R D R G G R Geducators, RD R RD RD and doctors, all being asked to think in new and Gscientists G D Dentistry O O S P SR OP D S S PDRS OPGR O G S PROG S PROG RS PRO P RS P R O CASE CASE CASE CASE Vacant different ways. Each year the U of A produces more than 8,000 new 2014 2014 W EXCE A EX E X C E X CEEX C EF E X C E A W A FA A F EXC EX F EXCEL Education ORFDA R OCFE L G RE LRLA OR D ORFD OR D ready AR OF L O F E L CRE L to bring O L LO LL GRRLOLG R alumni, solutions into the world. These are L OG L L E D S P R O G RL ES DPSRPOR E E E S PR E ES P R OLG E their own SEOP GRAND Heather Raymond, ’82 BEd, ’86 Dip(Ed), SILVER BRONZE GOLD the ways in which the university makes a positive difference in the ’95 MEd, ’02 PhD CASE CASE CASE CASE CASE CASE world, and one of the reasons I wanted to remain connected to this Engineering E XFCEEX C E E X EXCE E XCE F EXCEL OWINNER O F OWINNER O F O F C E L WINNER OF LL LL LL LL L AE AE AE AE A L Tom Gooding, ’78 BSc(MechEng) EA E A and R R R R R its alumni. R R RD AR R D R D AGRR G R institution RD R RD RD G G G G G G G D D D S PRO S P RS OP R O S P R O S P R SO P R O S PRO S PRO S PRO Extension As you receive this issue of New Trail, my time representing the Nikki van Dusen, ’96 BA, ’10 MA CASE CASE U of A’s quarter-million alumni is coming to an end. I am preparing EXCCEELL XEC ECC EXCEL F EEX F EXCELLL F EXCELL OFOF EX OF EOEOFOF ELELLLLELE LLE EO EO EE L E E LE E CL A A LCELCRL R A A CL A R L CR R L R R DA R R D RD R D over RD to hand S P SR OP GR O G S P R O G the role of Alumni Association president to Mary Pat S PDRS OPGR O G S PROG Barry, ’04 MA. The two years I have spent serving U of A alumni have CASE you to each of you who have helped to make EXCE EXCE E X CCASE E X E X CASE EXCE OF O FE L OF O F O FC E L C E L OF LL LL LL L L L been wonderful — thank E E E E E E W W WAW W W A AR A A A AR A A A A A RR D RADR RRDD RRR RSD SILVER GGRR A GOLD D S PR O G R GGG DS PR O GR D SS P R O G R SD SP R O S SPPR OO O PRO PR this such a rewarding experience. I encourage other alumni to get #3 - Circle text is spaced out closer to style of original logo. first logo is all Avenir, second logo is Stone Serif Semi and MetaPlus medium. Third logo is MetaBook in circle and MetaMedium in center.

#4 - first two logos from #3 with circle type treated similar to original COE logo Meta Bold in 2 & 3 center

We would like to hear your comments about the magazine. Send us your letters by post or email to the addresses on page 1. Letters may be edited for length or clarity.

involved and experience the benefits of staying connected to the university. As Mary Pat begins her new role at the end of this month, she takes the helm at a particularly inspiring time. This year we continue to celebrate the Alumni Association’s 100th anniversary with the association’s first Leadership Summit on May 22, featuring the Be a Difference Maker lecture by Rick Hansen, ’11 LLD (Honorary). Of course, we will have some extra reason to celebrate at this year’s Alumni Weekend Sept. 24-27. Ours is a very active group of alumni — a group that cares passionately about the university and its role in our city and province — and there are plenty of ways for you to get involved. Come back to campus and see what is happening at the U of A; take advantage of alumni volunteer opportunities; share your experiences with potential students; or come to an alumni event where you can reconnect with your peers or your passion. Turn to the events listings on page 48 for a list of upcoming opportunities to get involved. Mary Pat and I hope to see you soon.

Glenn Stowkowy, ’76 BSc(ElecEng), President, Alumni Association

CurmudgeonAB@ curmudgeonAB2 @UofA_Alumni Re winter New Trail – never fails to amaze me how these historyoriented issues always mention #CKUA but never @CJSR

These profiles of past alumni are great! Good to see what they have done and where they are now! –BERNARD LEONG

Keep in touch between New Trail issues. Find web-exclusive stories, videos and more online, or sign up for our monthly email, Thought Box by visiting newtrail.ualberta.ca.

Meet the Incoming President Get to know David Turpin through this series of videos before he takes office as the University of Alberta’s 13th president on July 1.

More About Your Favourite Predators Get more (gory) details about how these six marine predators hunt, catch and digest their prey (page 10).

New Trail Best in the West in Post-Secondary Magazines

New Trail was honoured recently as the best magazine in its category within western North America. The publication earned gold in the Best Magazine category (circulation greater than 75,000) in February from the Council for Advancement and Support of Education District VIII, which honours excellence in postsecondary publications. New Trail also earned a gold for Best Special Issue for the Winter 2013 Impact Issue. University of Alberta communicators earned 29 CASE VIII awards overall, including honours for writing, design, photography and illustration, video and social media. District VIII is geographically the largest of the eight North American CASE districts, encompassing the states of Alaska, Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana; the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba; and the Yukon, Northwest and Nunavut territories.

The Queen of Hugs Stole My Heart It might have been hockey night in Canada, but it was Lois Hole, ’00 LLD (Honorary), night in Tees, Alta.

Prepare to Take on a Second Career Plus five money tips from David Tims, ’85 BA(Hons), ’87 MBA, a man who manages billions.

Three Ways a Smartphone Could Literally Save Your Life Researching pocket-sized solutions. newtrail spring 2015

3

RESEARCH IN THE NEWS U of A research is always garnering media attention. Here’s the lowdown on what’s been causing a buzz.

Popping the Myths of Knuckle Cracking

4

newtrail.ualberta.ca

TRANSIT PASSES HELP HOMELESS YOUTHS

Dwelling on pain could slow recovery Patients who logged daily pain diaries reported recovery rates that were slower than those who kept no regular record of their symptoms. The study by the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry examined the effects of such a diary on patients with acute lower back sprains. At the three-month point in their recovery, only 52 per cent of patients who kept a diary reported recovery, while 79 per cent of patients who did not keep a diary did so. “It’s just more evidence suggesting that how we think about our symptoms affects our symptoms,” says Robert Ferrari, ’88 BSc(Med), ’90 MD, ’10 MSc, a clinical professor in the faculty’s Department of Medicine and a practising physician. “Symptoms are everything when it comes to the sense of recovery.” –SCIENCEDAILY

Homeless youth who were given free transit passes or bus tickets had dramatically fewer encounters with police and better personal safety, according to a recent study led by Miriam Steward from the Faculty of Nursing. The 40 teens involved in the project, called Routes to Homes, were also able to attend school more regularly and search for jobs thanks to their ability to safely manoeuvre around the city. –EDMONTON JOURNAL

Kid chefs make healthier choices The most effective way to encourage kids to eat and enjoy healthy food could be to get them involved in preparing meals. Researchers from the School of Public Health surveyed Grade 5 students and found those who helped their parents prepare meals showed an increased preference for fruits and vegetables over junk food. They were also more certain about the importance of healthy food choices. The overall goal of the research is to decrease the burden of chronic disease on society. Healthy eating does that by promoting bone and muscle development, learning and self-esteem. –GLOBE AND MAIL

THINKSTOCK

“Pull my finger,” the joke embraced by school-aged kids and embarrassing uncles the world over, is now being used to settle a decades-long debate about what happens when you crack your knuckles. A team of researchers led by the University of Alberta used MRI video to figure out what happens inside finger joints to cause the distinctive popping sounds. The answer? Bubbles. “We call it the ‘pull my finger study’ — and actually pulled on someone’s finger and filmed what happens in the MRI. When you do that, you can actually see very clearly what is happening inside the joints,” explains lead author Greg Kawchuk, a professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. MRI video that captured the moment of each knuckle cracking in real time — less than 310 milliseconds — showed the sound is associated with the rapid creation of a gas cavity within the synovial fluid (which lubricates the joints) as the joint separates. “It’s a little bit like forming a vacuum,” Kawchuk says. “As the joint surfaces suddenly separate, there is no more fluid available to fill the increasing joint volume, so a cavity is created, and that event is what’s associated with the sound.” The video also showed a white flash appeared just before cracking, which no one has observed before. Kawchuk would like to use even more advanced MRI technology to understand what happens in the joint after the pop, and what it all means for joint health. –BRYAN ALARY

ALUMNI IN THE NEWS U of A alumni who made headlines recently

Leanne Brown, ’07 BA, was named one of Forbes’ 2015 30 Under 30. The author of Good and Cheap, a cookbook for people with limited income, Brown sells books using the “get one, give one” philosophy to reach people in need. The second edition is set for release July 14, and her next project is a retail venture with Workman Publishing Company. –FORBES

ILLUSTRATION BY JULIUS CSOTONYI, PHOTO PROVIDED

Lorne Tyrrell, ’64 BSc, ’68 MD, renowned for his work in treating viral hepatitis, has been recognized with one of Canada’s most prestigious awards: the 2015 Killam Prize for Health Sciences. The director of the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology and professor in the U of A’s Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology has dedicated decades of research to developing vaccines for viral hepatitis B and C, including an oral vaccine for hepatitis B now licensed in 200 countries. Five Killam prizes of $100,000 are awarded annually by the Canada Council for the Arts. –EDMONTON JOURNAL

SNAKES AT LEAST 40 MILLION YEARS OLDER THAN WE THOUGHT We’re going to need a lot more candles to celebrate the snake’s birthday. We now know that the creatures are much older than scientists previously believed — by 40 to 67 million years — thanks to research published by an international team that included U of A professor Michael Caldwell, ’86 BPE, ’91 BSc(Hons). Until now, the oldest known snake fossil dated back 100 million years. This new research, which re-examined fossil material found around the world as long ago as the 1850s — some of these fossils previously misidentified as lizards — proves snakes existed 140 to 167 million years ago. That means snake evolution might be more complex than previously thought.

Former deputy prime minister Anne McLellan, ’07 LLD (Honorary), was to be installed as the seventh chancellor of Dalhousie University at the end of May. McLellan was appointed associate professor of law at the U of A in 1980 and later served as associate dean and dean of the Faculty of Law. McLellan was Liberal MP for EdmontonCentre from 1993 to 2006. –CTV NEWS Greg Abel, ’84 BCom, was named a possible successor to American businessman Warren Buffett by Charlie Munger, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Abel, who heads the company’s energy division, was named one of two people likely to become CEO of the US$365-billion corporation should Buffett step down. –BLOOMBERG BUSINESS

newtrail spring 2015

5

CAMPUS NEWS A brief look at what’s new at the U

DiscoverE, delivered by students in the Faculty of Engineering, has won a record third Google Roots in Science and Engineering Award. The group runs classroom workshops, clubs, events and camps for more than 26,000 youth every year. This year’s $25,000 award will go toward creating DiscoverE’s second massive open online course, introducing students to Java and teaching them to program apps.

A swath of U of A land in southern Alberta will be forever conserved in its current state with no future development allowed. The university signed an agreement with Western Sky Land Trust to ensure the 4,856-hectare Rangeland Research Institute–Mattheis Ranch near Brooks, Alta., remains an intact living research lab. The ranch, donated to the university in 2010 by alumni Edwin, ’57 BSc(PetEng), and Ruth Mattheis, ’58 BA, is home to a diverse ecosystem and about 30 at-risk species. The U of A will lead a national network for glycomics research, the study of carbohydrates, or sugars, in biological systems. The Alberta Glycomics Centre at the U of A has been chosen to host the Canadian Glycomics Network, or GlycoNet, a federally funded program that unites 60 researchers from nearly two dozen post-secondary institutions with industry, government and international partners. GlycoNet is focusing on five key areas of research: chronic disease, diabetes and obesity, rare genetic disease, antimicrobials and therapeutic proteins and vaccines.

6

newtrail.ualberta.ca

5 Reasons Not to Fear a Climbing Wall by Jay Smith, ’02 BA(Hons), ’05 MA

BEGINNER S WELCOMEARE 4 OTHER YOU SHOURE ASONS LD IT A TRY GIVE

+

The Physical Activity Wellness Centre is now open on campus. The sustainably designed 17,000-square-metre facility houses social areas, a double-decker fitness centre and sports research space. It also houses a two-storey climbing wall that, at up to 4.5 metres high, ranks among the tallest in Canada. A $10M donation from Dick, ’74 BDes, ’75 LLB, and Carol Wilson, ’74 BEd, helped fund the Wilson Climbing Centre and the Hanson Fitness and Lifestyle Centre, named for Carol’s father. Alumni can access the new facility with their ONEcard. For those eager to try out the new climbing wall but who are nervous or inexperienced, program co-ordinator Dallas Mix, ’14 BEd, offers these tips.

1

NOT JUST FOR SUPERHEROES Mix, who helps design and regularly remake the climbing routes at the Wilson Climbing Centre, says they’re designed for all abilities and body types.

2

CLIMBERS ARE A FRIENDLY BUNCH Attitudes, be gone. Most climbing centres strive to create a welcoming environment for newcomers who want to (ahem) learn the ropes. The public can

rent equipment, sign up for adult and children’s classes and enrol in summer camps for kids.

3

IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT UP Climbing facilities typically offer three types of climbing. “Bouldering” involves moving both vertically and horizontally without a rope (good for beginners). “Top-roping” is done with a partner, who holds one end of a rope that is passed through an anchor at the top of the wall

and attached to the climber’s harness. In “lead climbing,” the rope trails behind the climber, who passes it through “quick draws” anchored in the wall as he or she climbs. It’s trickier and can mean longer falls.

4

HOW TO READ A CLIMBING WALL It may look random, but the colourful holds scattered across a wall are placed deliberately to create routes of varying difficulties. Red is easiest, followed by

black, green, blue and yellow, the hardest.

5

BLAZING THE TRAILS Bouldering routes are called “problems” because solving them is as much about smarts as it is about strength. When Mix sets a route he’s inspired by many things, such as the features of the wall or a hold that enables a “really cool movement.” Mainly, he says, his goal “is to ensure everyone has the best experience possible.”

PHOTO BY NICK CROKEN

U of A teams netted five national championships this season. The Bears volleyball and hockey teams and the men’s and women’s curling teams were champs in Canadian Interuniversity Sport. The Bears and Pandas tennis team won the national title in non-CIS play. The U of A has won at least one championship per year for the past 21 years.

THINKSTOCK

Brain Difference Discovered in Stutterers A new study sheds light on the brain mechanisms underlying stuttering. A U of A research team used MRIs to examine brain development in children and adults, and determined that the grey matter in a region of the brain responsible for speech, known as Broca’s area, develops differently in people who stutter. The results do not indicate for certain that an atypically developed Broca’s region causes stuttering, says research lead Deryk Beal, assistant professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. However the findings support the need for a long-term study of brain development to compare the brain growth of children who stutter with that of those who don’t — as well as for that of those who stutter and recover. “That will help us know how the brains of children who stutter and recover change to achieve fluent speech. We can then start to change our treatments so they affect all kids in this way,” says Beal, who is also executive director of the U of A’s Institute for Stuttering Treatment and Research, a self-funded centre helping people overcome stuttering since 1985. –BRYAN ALARY

DIGESTIVE BACTERIA IN INFANTS LINKED TO ALLERGIES A new study has found that infants with fewer kinds of bacteria in their digestive tracts are more likely to become sensitized to foods such as egg, milk or peanuts. Infants who developed food intolerances also showed altered levels of specific types of intestinal bacteria called enterobacteriaceae and bacteroidaceae, researchers from the U of A and the University of Manitoba discovered. Their study used bacteria in infant stool samples collected at three months and one year old. They plan to examine the young participants again at ages three and five. In the hunt for new ways to prevent or treat allergies, the researchers theorize that modifying gut microbiota may be one way to battle allergies.

newtrail spring 2015

7

A VOICE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

STUDENT LIFE

Claire Edwards may be the most civic-minded young woman ever. The third-year political science student is hoping to work with a human rights organization in D.C. this fall through a Washington Center internship. She chairs the City of Edmonton Youth Council. She’s president of the Student Network for Advocacy and Public Policy, where she works with students to lobby political leaders. Her own advocacy has ranged from eliminating bottled water use in her high school to getting a student trustee on the Edmonton Public School Board. In short, Edwards is an expert on getting young people involved in their communities.

How can young people get more involved? Volunteer and leadership opportunities are great for preparing youth for the future. When I talk about getting students engaged in their schools, I hope that translates 8

newtrail.ualberta.ca

into active citizenship when they’re older. Being on a community league, for example, may seem like an adult thing, but it’s a great opportunity to see your work translated into something tangible. We often hear young people are apathetic. Do you believe that’s the case? I don’t think my generation

is less engaged; I think they’re disempowered. Youth don’t think they’re powerful, so they sit at home. And I don’t think that’s just youth. There’s an epidemic in our society that says, “It doesn’t matter if I vote. It doesn’t matter if I donate to charity. It doesn’t matter if I go out on the picket line.” So it’s important that we start telling youth, as early as

possible, that every little bit does matter. That’s what citizenship is about. What can organizations do to include young voices? On boards, I’m always the token young person. If organizations are going to give youth a seat at the table, it has to be to learn from them, not as a placeholder. –BRIDGET STIRLING

PHOTO BY JOHN ULAN

What got you interested in being active in civic life? When I was in Grade 10, I took part in a leadership program that connects students to non-profit agencies to learn about human rights. That was my first exposure to social justice work. My parents aren’t activists, and I’m the first person in my family to go to university, but my parents taught me that actions have an impact, whether you’re big or small. My first experience of lobbying was pitching the idea of a student trustee on the school board. I coldcalled public school board chair Sarah Hoffman, ’04 BEd, ’08 MEd. At the time, it was terrifying, but I thought, “How has no one thought about this before?”

FROM THE COLLECTIONS

UNCOVERING CAMPUS TREASURES The University of Alberta Museums house many objects that provide students and researchers with a deeper understanding of the world’s mysteries. Here we uncover items from some of the university’s diverse collections.

Changing perceptions of human prehistory These projectile points, acquired recently by the Bryan/Gruhn Archaeology Collection, are from the Middle Stone Age — about 90,000 years BP, or before present — from what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These harpoon casts are exquisite examples of bone workmanship exhibiting significant technological advancement, supporting the idea that behaviourally modern humans evolved in Africa. The Bryan/Gruhn Archeology Collection contains more than 10,000 prehistoric and historic objects from around the world.

© Michael Neugebauer

An Evening with Dr. Jane Goodall PhD, DBE, Founder of the Jane Goodall Institute, UN Messenger of Peace

Wednesday September 9, 2015 Winspear Centre Edmonton

Summer prints are all about Canadiana Christopher Pratt, one of Canada’s iconic painters and printmakers, captures the unbeatable sensations of a summer road trip in this recent donation to the U of A’s art collection. Summer of the Karmann Ghia enhances the contemporary Canadian holdings of one of North America’s strongest print collections, used regularly in the Print Study Centre for teaching and research.

PHOTOS BY JOHN ULAN

April showers bring May flowers This Calypso orchid is a local species that flowers back to life in spring and is one of the roughly 130,000 specimens in the Vascular Plant Herbarium, a research and teaching resource that captures biodiversity from the year 1816 to the present. U of A botanists are busy preparing for Botany 2015, an international conference of several societies with more than 2,300 participating plant scientists, hosted for the first time in Edmonton this July. All across campus are the 29 interdisciplinary collections that make up the University of Alberta Museums. This unique model distinguishes the U of A as one of the world’s great public universities. The collections are used daily for teaching, research and community engagement, and many are open to the public. museums.ualberta.ca

In support of the Ilsa Mae Research Fund at Muscular Dystrophy Canada

and the

Tickets starting at $41 on sale now at the Winspear Box Office or www.winspearcentre.com presented by

© the Jane Goodall Institute

newtrail spring 2015

9

by sarah pratt illustration by pulp studios

FROM THE WORLD’S LARGEST HABITAT, THE OCEAN, COME BIZARRE TALES OF SIX PREDATORS SEEMINGLY SPAWNED IN A LABORATORY NIGHTMARE. Like creatures from a low-budget horror movie, these six marine invertebrates are among the most fantastic and efficient killers of the deep, hunting and devouring prey with ingenuity and precision. Lindsey Leighton, associate professor in the U of A’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, describes some of his favourite marine predators, so prepare yourself for the most ghastly ocean death rituals by creatures who are anything but spineless.

10

newtrail.ualberta.ca

With its two club-like arms, this invertebrate can unleash the fastest predatory strike on the planet: 80 km/h and 880 Newtons of force. If a major leaguer could accelerate his arm at onetenth this speed, he could throw a baseball into orbit. Legend says the mantis shrimp can break aquarium glass or even a human bone.

Don’t be fooled by this marine gastropod’s size or good looks. Lying in wait, it smells prey by extending a tube-like proboscis, then launches a barbed harpoon. A deadly cocktail of neurotoxins paralyzes the victim. The cone snail pulls its still-living dinner into its mouth and eats it whole. Some can even kill a human.

The moon snail oozes along the ocean floor — and pity the poor bivalve it finds. An expandable appendage secretes chemicals, including hydrochloric acid, that soften a spot on the prey’s shell, while a tongue-like organ covered in teeth scrapes away the weakened shell. Days later, the snail breaks through and sucks out the flesh of its prey.

A man’s hand has an average grip of 660 kilopascals. Saltwater crocodiles have a bite force of 25,500 kPa. Meanwhile, the seemingly innocuous stone crab is armed with a crushing claw that can exert at least 96,000 kPa. “If it gets hold of your finger, it’s like having it run over by a dump truck,” says Leighton.

Imagine a blind cannibal with 12 to 13 arms creeping along the ocean floor on thousands of sensitive tube feet. Once it wraps itself around the victim, it extrudes its stomach, which can slip through even the smallest gaps in a bivalve shell. Digestive juices dissolve the prey’s flesh, giving new meaning to clam on the half shell.

Despite this crab’s bashful name, it is bold on the hunt. The unusual-looking calappid’s right pincer features a specialized curved tooth that it inserts into the prey, then cuts a channel along the shell like using a can opener. When the victim is exposed, the crab’s left forcep-like pincer extracts the meat from within.

newtrail spring 2015

11

When Food is Your Enemy

by SARAH PRATT

For people living with a recurrent C. difficile infection, everyday mealtime becomes a painful test. Patients can’t properly digest food, and the joy of eating becomes suffering as each meal tears its way through the intestines. U of A researchers are finding that an ancient solution — fecal transplants — is giving patients back their lives when other treatments have failed.

12

newtrail.ualberta.ca

of gastrointestinal hell, Susan Brothen cried with relief when she was finally able to eat a tomato, lettuce and mayo sandwich. In spring 2014, Brothen suffered from a recurring bacterial infection that left her with endless bouts of diarrhea, fevers and abdominal pain. On her worst days, she would go to the bathroom up to 13 times; good days meant five or six trips. For four months she was scared to leave the house because she had no control over her bodily functions. She lived on mushed salmon mixed with a bit of rice. “Every time I ate I would be in the bathroom within a half-hour,” says Brothen. “My body wasn’t getting any nutrition, I had no energy and I lost 30 pounds. I had no appetite and I would gag on my food. All I thought about was food and the bathroom. It was affecting everything in my life.” She eventually learned the culprit was a recurrent clostridium difficile infection, also known as RCDI, a bacterial infection that developed when she used antibiotics to treat a blocked salivary gland. Getting sick from antibiotics? It’s possible because antibiotics disrupt the normal populations of gut microflora, making the environment friendlier for nasty bacteria such as C. difficile. It grows quickly and produces toxins that cause illness. In the competition for limited resources in the gut, sometimes the bad guys win. Typically, people with C. difficile infections are prescribed another antibiotic. But for the unlucky patients who develop a recurring infection, symptoms return within days of stopping treatment. Some end up on a seemingly endless cycle of illness and antibiotics long after the original illness is gone. Recurrent C. difficile deprives patients of the ability to live normal lives and costs the health-care system millions annually. Patients have traditionally undergone treatments that are more invasive and prone to side-effects, such as surgery or repeated rounds of antibiotics. Recently, a different method is gaining popularity: fecal microbial transplant. It’s literally

PHOTO BY JOHN ULAN

after four months

transplanting healthy donor feces into a patient’s gut to replenish normal bacteria levels and ensure the intestines are healthy and working as they should. Relief comes almost immediately for those who undergo a fecal transplant, says one of two people performing the procedure in Alberta. “Patients often feel better the next day. It’s amazing,” says Dina Kao, ’94 BSc(Spec), ’99 MD, ’08 MSc, associate professor and a gastroenterologist at the University of Alberta Hospital. “This is the most rewarding work I have ever done.” Kao has performed fecal microbial transplants as what is termed investigational therapy since 2012, and has successfully treated more than 140 people with recurrent C. difficile. According to Kao, the procedure could save the provincial health-care system at least $10,000 per patient. Clinical trials

By the Numbers Alberta records about 3,000 cases of C. difficile annually, equalling 21,300 hospital days. ————— C. difficile is ranked second in all Alberta hospital-acquired bacterial infections. It costs the provincial health-care system $32 million annually. ————— Fecal microbial transplants (FMT) could save the health-care system at least $10,000 per patient, says Dina Kao. This includes the cost of antimicrobials, hospitalization and emergency room visits. —————

$1,388.08:

cost of a fresh-sample FMT colonoscopy

$1,414.90:

cost of a frozen-sample FMT colonoscopy

are also underway to use the procedure to treat inflammatory bowel disease and hepatic encephalopathy, which is the loss of brain function brought on by liver disorders. Most patients choose a colonoscopy as the delivery method for the fecal transplant. Other options include an enema, a feeding tube or an oral treatment that involves taking 40 pills in an hour. Patients who need more than one transplant can usually have another done two to 14 days after the first. As for donor feces, every precaution is taken to ensure a healthy sample is harvested. Most of the donors are nurses, tested to ensure excellent overall health and safe specimens. The prepared fecal suspensions are stored as fresh and frozen fluid; the use of one or the other depends on availability. Before and after the procedure, Kao closely monitors the patient’s gut bacteria. Within days or even hours of a transplant, the mix of bacteria changes radically, returning quickly to a healthy combination predominantly of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, bacteria essential in a healthy human gut. “It’s like having two arms and two legs — the combination of these bacteria are normal for us,” says Kao. Brothen started to feel better immediately after her fecal transplant, and by the next day was able to leave behind her salmon-and-rice diet. “That sandwich tasted so good,” she says. “I hadn’t eaten greens in four months.” The future of fecal transplants is one of hope and continued research. “There is so much we don’t know about fecal transplants,” says Kao. “Health Canada considers it investigational therapy and recently they have said they want to put in some regulations to ensure the safety of patients. There will probably be some regulation changes in the future, but we don’t yet know what those look like.” Brothen hopes the treatment helps as many people as possible. “If someone told me that I would have a fecal transplant, I would have said they were nuts,” she says. “But when you’re sick you will do anything to get better. Dr. Kao gave me my quality of life back.” new trail spring 2015 13

whatsoeverthingsaretrue

Second Chance at a Second Tongue

AS A YOUNG MAN GROWING UP IN ALBERTA, THERE WAS HUMILIATION TO BE FOUND IN TRYING TO SPEAK PROPER FRENCH. AS A GROWN MAN WITHOUT A SECOND LANGUAUGE, THE HUMILIATION HAS TURNED TO REGRET.

toward the end of winter , a national organization called le Français pour l’avenir, French for the Future, invited me to deliver a speech. The audience was high school students in francophone and immersion programs who must soon decide whether to continue their studies in French or in English.

I was, in many ways, an odd choice of speaker. Growing up, my father had conspiracy theories about Pierre Trudeau and his plans to punish the West with cruel language laws. Neither he nor my mother had gone to university. The only time we heard anyone speak a language other than English was when we skipped the television channel from 11 to 13. I still think of 12 as the French-iest number. In high school, I took French classes but only because it was required for university acceptance. Often I am haunted by the way we treated Madame Hoffman. Actually trying to speak French properly, with an accent, would have been like walking around with no pants. It wasn’t until I was in university that it occurred to me that my hometown, Leduc, had a French name. Graduating from university also required pesky second-language requirements. It seemed such an imposition at the time, an annoying ritual that served no purpose. It’s not like I would ever live or work in Quebec or a foreign country. And besides, I spoke the language everyone wanted to speak, the language of the Queen and Brad Pitt: English! Then I moved to Montreal. The shame set in on my second or third day in the city, and it has remained with me for almost 20 years. I had been 14

newtrail.ualberta.ca

an idiot. My blessed parents had been idiots. My friends had been idiots. All that time, when I was goofing off, I might have been learning French. And Spanish. Italian, German, Mandarin. As I write this, I am preparing to make a business presentation to French winemakers. I lived in Montreal for several years, and in France for more than a year, but there remains a huge gap between my thoughts and my ability to express them in French. Why should they trust one euro of their money with a person who makes grammatical errors when speaking their language? Then I will be working in Iceland. I have ordered a book called Colloquial Icelandic, but the best I can hope for is a reception like I had in Kenya, where I spoke guidebook Swahili: smiles, pats on the back, an E for effort. John Ralston Saul, a sometimesAlbertan, is the founding patron of French for the Future. His dream is a Canada where everyone is at least trilingual. This seems an impossible dream until you go to Europe, or Africa, or the Middle East, or Asia, or the cities of Latin America. The organizers of the French for the Future conference, at the U of A’s Campus Saint-Jean, asked me to speak because I became serious about French at a late age — so late that I will always have a funny accent, always make

grammatical errors, always sound “foreign” to a native speaker of French. But I had gone to all the trouble of taking classes at the Alliance Française, through the U of A Extension program. They asked me to speak because they could smell the regret on me. It is among our most powerful emotions when we harness it for the good of 16-year-olds. When I arrived to make the speech, I learned it was supposed to be delivered in French. I blacked out for a minute or so. But thanks to years of suffering, and an ego so battered by humiliation that it no longer guards against risk, I told the students a 40-minute cautionary tale in my second language. Form met content. Every error was another reason for them to continue en français, lest they arrive on a stage one day, 40 and balding and ruining the subjunctive. Learning French and Spanish, which I have done since leaving university, with a relatively miserable and saggy brain, has turned out to be the most profitable decision I have ever made — economically and spiritually. When you learn a second language and you travel or work abroad, you see how it transforms your experience. While I take full responsibility for my past stupidity in the matter of language, I must say the young people of today have astounding opportunities. Students at the U of A can study abroad and connect with mentors and alumni networks all over the world. I’m already brainwashing my two daughters, who speak French better than I do. Languages and international experiences aren’t optional: this is just what serious people do. It’s an essential part of their education. “Did you do it, Daddy? When you were in school?” I think of Madame Hoffman. And I regret. Todd Babiak, ’95 BA, co-founded the company Story Engine and has published several books, including Come Barbarians, a national bestseller.

PHOTO BY SELENA PHILLIPS-BOYLE

by Todd Babiak

The Art of Patience

WHERE DO YOU START WHEN LIFE TELLS YOU IT’S TIME TO SLOW DOWN? CURTIS GILLESPIE OFFERS LESSONS LEARNED ALONG THE PATH TO FORBEARANCE

Learning doesn’t end when you accept your degree. We are all lifelong learners whether we pursue lessons in a class or a lecture hall — or these lessons pursue us. This is the first of a regular series of essays by Curtis Gillespie, ’85 BA, reflecting on the continuing opportunities for education that life throws our way, sometimes when we least expect them.

i’ve always loved shortcuts, even though they sometimes turn into long cuts, such as the time (my wife likes to remind me) I drove us down a British Columbia logging road to save us an hour. Or it would have, had we not ended up on a nerve-shredding onelane road in the rain, dodging careening semi-trailers spilling timber. Shortcuts aren’t just about driving, either. If I can heat my coffee in the microwave at the same time I’m loading the dishwasher, or if I’m able to iron shirts while catching the hockey game, well, the entire day gets an upgrade. But I’ve come to learn over the years that this love of shortcuts is, in fact, a less-than-ideal aspect of my character. It’s impatience. I knew it existed, but, until recently, I considered it less a flaw than a fuel source — sometimes a person needs to push hard, right?

16 newtrail.ualberta.ca

Wrong. Last summer I was putting a new blade into a retractable utility knife. The lid of the blade box was jammed shut. Rather than walk the 20 steps to my tool shelf to find the right tool to open it, I tried to pry it open manually. I was applying some force to it when the lid gave and my hand swept across the blade tips, opening up a bone-deep gash in my index finger. The slit was so pure and so deep that it didn’t even hurt or start bleeding for a good five seconds. But then it began to pour blood, and pain liquefied my torso. I had to drive myself to the hospital with one hand — the hand that was also trying to staunch the bleeding from my finger. It seemed only fitting that the most painful part of the entire sorry episode came when the doctor had to place a disinfecting needle straight into the very depth of the gash. I swear it touched bone. All this because I didn’t have the patience to spend 10 seconds finding the right tool, making me (sorry, I can’t resist) the impatient outpatient. Later that summer, we were driving to the Okanagan in B.C. for our family holiday. At one point, while cruising through a sleepy village at 20 kilometres an hour, my phone went off. I managed to ignore the ring but saw that a message had been left. Radically overestimating my centrality to the universe (or even to the people who know me), I decided to check the message while driving. My wife and children took exception to this and declared that since the message was obviously more important to me than their safety, it was clear I didn’t care about them. I laughed, or tried to, but one of my daughters gave me a devastatingly level stare and said, “We’re not kidding.” I took these, and similar events happening around the same time, as signs that maybe patience was an art I needed to school myself in. But what is patience, anyway? And what is the opposite of patience? Impatience? Not quite, because impatience suggests an

ILLUSTRATION BY KELLY SUTHERLAND

continuingeducation

PHOTO BY JOHN ULAN

by Curtis Gillespie

inability to wait, a temporal quality, whereas patience suggests a kind of calm acceptance, a spiritual quality. I would suggest that the opposite of patience is rage, even solipsism, a kind of selfishness. In reality, it’s not about me, that guy who cut me off. The girl fumbling with her bank card at the grocery till isn’t doing it solely to make me late picking up my daughter from soccer. She’s not doing it for any reason. This is the point of patience, is it not, to separate the action from the outcome? To let things unfold. To accept. Not that it’s always easy. One day in the dead of this past winter, I came to a four-way stop close to our neighbourhood and pulled up to the intersection just a foot or two ahead of a sedan entering from the right. We both came to a full stop at more or less the same time. Normally, I’d have taken the three-inch advantage I owned as a sign that I had the right of way. No, I told myself, be patient, force yourself to wait, allow the other car to go first. I flicked my headlights, the universal signal to indicate to another vehicle that it may proceed. Except that apparently this driver had not been schooled on universal signals. I flicked again, a little more quickly. Nothing. I waved my hand, motioning for them to go. Nothing. It was as if the driver had proceeded to the intersection only to succumb to a narcoleptic fit. Non-issue, I said to myself. If that person doesn’t want to proceed that is his or her prerogative. Let it wash over you. Donning a cloak of imperturbable calm I took my foot off the brake and eased into the intersection, at which point the hitherto immobile sedan to my right shot off its spot like a rocket car on Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, spurting directly towards me, causing me to hit the brakes to avoid a collision. “You IDIOT!” I shouted. “What a …” The rest is unprintable. I drove home rattled. If that was all it took to shatter my evolving monastic serenity, then what chance did I stand

with the more important challenges of life in which true patience would stand me in good stead? Ruminating on this question, I began to see that I was frequently impatient without even knowing what endpoint I was so desperate to get to. Impatience is expressed in all of us in so many small but damaging ways. I recognize my impatience when I channel surf, skim books, get fidgety in long conversations, eat too quickly. I don’t know for sure if this is the main point of practices like mindfulness or books like Carl Honoré’s In Praise of Slow — that impatience robs us of appreciation — but that’s sure how it feels when I’m being impatient. Our culture has long viewed various expressions of impatience — such as ambition, energy, drive, assertiveness, directness — as positive traits, but are they really? If we like to say that something is worth the wait, then why are we so regularly unwilling to wait? Certainly, technology doesn’t help. Too many of us crave the dopamine hit of our email ping and are obsessed with the incredibly important and selfreferential things our smartphones promise us every minute or so (research has shown that people with smartphones check them, on average, more than 700 times a day). But it’s not all about technology. Our upbringing imprints many things upon us. I was fortunate enough to grow up in a loving household, but I was also one of six children, close in age, and in our tiny house we fought — often literally — for space, privacy, control of the TV, beds, bathroom time, attention and even food. It was a fun but relentlessly Darwinian childhood. And I’m not exaggerating when I liken our dinner-table routine to a pack of slavering hyenas hunched over an antelope carcass on the Serengeti. Patience meant getting stuck with antelope hooves on your plate. I think my mother must have understood the psychological pressure, because she actually tried to get our family, even my laconic father, to adopt

meditation when I was about 14. The practice didn’t stick, sadly. For my own part it was impossible to concentrate during morning meditation because the mantra our Nepalese teacher had given me, ing, was impossible to repeat without thinking of hockey, due to the charismatic presence of one of the first Swedes to ever play in the NHL, Inge Hammarström, who was then with the Toronto Maple Leafs. Every time I tried to empty my mind, all I saw was a puckrushing defenceman. Such was my upbringing. I’ve started meditating again, since it can’t hurt and even if I can’t concentrate or empty my mind, at least the 15 minutes of silence is a bonus. I find it challenging, though the acceptance of the wandering mind helps. I’ve also attempted to adopt other methods of patience-cultivation. I have once or twice tried to sit silent and still, without electronics, for a few minutes here and there with no other purpose than to just be, though that mostly just reminds me of my tinnitus. I have altered my driving habits, though there is still the occasional reversal. I’m trying to be more patient, to be tall grass in the wind, though sometimes I still get mown short by the other half of my nature. Everyone says it’s a process, so I’ve also tried to make it a process to share with others. For instance, I handed this essay in late even though I finished it early, only because I hoped to present my editor with a patience opportunity. She has expressed the depth of her gratitude through her actions, in that I have yet to receive further assignments. Her patience is impressive, indeed, and I will undoubtedly learn something from it. Curtis Gillespie has written five books, including the novel Crown Shyness. His magazine writing on politics, sports, travel, science and the arts has earned him seven National Magazine Awards. He lives in Edmonton with his wife and their two daughters. newtrail spring 2015

17

Researchers are breaking down boundaries and finding allies in unexpected places, speeding up discovery in the hunt for answers

BY AMIE FILKOW ILLUSTRATION BY SÉBASTIEN THIBAULT

18

newtrail.ualberta.ca

new trail spring 2015 19

E

“EVERYONE HAS A CANCER STORY.

“PEOPLE SEEM TO INTUITIVELY UNDERSTAND THAT THIS IS A LONG BATTLE THAT’S GOING TO REQUIRE A SUSTAINED EFFORT.” – TIMOTHY CAULFIELD

20

newtrail.ualberta.ca

When I was first diagnosed, every person I met told me theirs.” Tanya Prochazka’s own cancer story involves nearly a decade of hope in the face of daunting odds and repeated disappointment. It’s about holding on to that hope, even beyond her own life. An internationally acclaimed cellist who has performed everywhere from Carnegie Hall to the wedding ceremony for Wayne Gretzky, ’00 LLD (Honorary), Prochazka’s life in the past few years has been full of weddings, births, laughter and milestones. Back when she was first diagnosed with Stage 3 ovarian cancer, she never thought she’d be around to see any of these milestones, but this mother of three grown children and four young grandchildren has defied the odds. Few ovarian cancer patients live more than five years after diagnosis; she’s on year nine. (“I’m not even in the data,” she says.) With the support of family, friends and a phalanx of dedicated health practitioners, the former University of Alberta music professor has endured three surgeries, four gruelling rounds of chemotherapy plus one of radiation. “It all gets very hazy because you just leap from one treatment to the next. You forget what it’s like to be normal.” Even after chemotherapy proved ineffective, Prochazka kept trying. She participated in a clinical trial in Seattle and explored other experimental treatments, including nitroglycerine. She donated a biopsy sample of her cancer to the provincial tumour bank for a U of A research project. “I just wanted to be there to see my children go through their lives and help them with their children,” she said a year ago. But nothing has halted her cancer, and there are no more treatments to try.

THE EMPEROR OF ALL MALADIES Cancer continues to be the leading cause of death in Canada. Last year, more than 191,000 new cases were diagnosed and 76,000 Canadians died from cancer. Even more alarming are these numbers: two out of five of us will develop cancer in our lifetimes and one out of every four will die from it. Between private donations and public funding, more than $500 million is invested in Canadian cancer research each year. But is it money well spent? Statistics from the Canadian Cancer Society, which tracks cancer survival rates, would suggest it is. When the organization started funding research in the 1940s, just 25 per cent of Canadians diagnosed with cancer survived. Today, that number is 60 per cent. Of course, survival rates tell only part of the story. There’s a bigger question for anyone touched by this disease: Will there ever be a cure? The question is at once impossible and surprisingly easy to answer. There can be no capital “C” cure for cancer because cancer is not one thing. Breakthroughs in DNA sequencing have shattered the naïve assumption that cancer is a single-gene disease. Cancer is a catch-all for more than 200 varieties of abnormal cellular growth, each one able to mutate and evolve. In The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, oncologist and author Siddhartha Mukherjee describes cancer as “a parallel species, one perhaps more adapted to survival than even we are …. If we, as a species, are the ultimate product of Darwinian selection, then so, too, is this incredible disease that lurks inside us.” Even within one type of cancer, such as lung cancer, thousands of molecular profiles could exist, each responding differently to treatment. To further complicate matters, the severity, activity and progression of the disease can differ vastly from one patient to another. And then there’s the astronomical cost and painstakingly slow process of medical research and drug development. These factors make cancer a spreading, moving target that can’t be eradicated with a single silver bullet. “People seem to intuitively understand that this is a long battle that’s going to require a sustained effort,” says Timothy Caulfield, ’87 BSc(Spec), ’90 LLB, Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy at the U of A and research director of the Health Law Institute. “Big promises have been made — big promises that haven’t necessarily been fulfilled. But people see the successes we’ve had with childhood leukemia and breast cancer, for example, and they’re willing to continue the fight. You see that in the public support for charities and fun runs and people wanting to donate.”

CANCER SUCCESSES AT THE U OF A 1970s Biochemists Alan Paterson and Carol Cass discover and characterize “nucleoside transport” — how cells absorb anticancer drugs. 1980s Biochemist Chris Bleackley and collaborators discover granzyme-B, molecular bullets that immune cells use to destroy cancer cells and can be used for targeted cancer therapy. 2000s Nanotechnology researchers Linda Pilarski and Chris Backhouse, ’85 BSc(Hons), develop the lab-ona-chip device that can test for up to 80 different genetic markers of cancer. 2010s Nuclear radiologist Sandy McEwan oversees the first CT scan to use a cyclotron-produced medical isotope to detect cancer — a safer, cleaner alternative to medical isotopes made from nuclear reactors. 2014 Cancer biologist John Lewis leads a prostate cancer research team that pioneers a technique to capture realtime video of cancer cells metastasizing, revealing how the cells attack the tissue from the bloodstream to form a new tumour. new trail spring 2015 21

22 newtrail.ualberta.ca

“AS A BASIC SCIENTIST I CAN DO AMAZING THINGS IN THE LAB AND HAVE BREAKTHROUGHS THAT GET PUBLISHED IN ‘NATURE,’ BUT THEY MAY HAVE NO IMPACT ON PATIENTS BECAUSE I DON’T HAVE THE KNOWLEDGE OR RESOURCES TO BRING IT TO THE CLINICAL NEXT STEP.” – JOHN LEWIS

SKATING WITH GRETZKY “I’m tired of seeing my patients die,” says cancer physican John Mackey, ’90 MD, a fierce advocate for research, who links patient care back to the lab bench. Mackey is a medical oncologist who treats breast cancer patients and a professor of oncology in the U of A’s Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry. He serves as director of clinical trials at the Cross Cancer Institute in Edmonton and is co-founder of Alberta’s pioneering provincial tumour bank, now part of the Alberta Cancer Research Biorepository. Sitting in his clinical office at the Cross, fishing through a stack of papers for a journal article, he laughs, “I’m a jack of all trades and a master of none.” In fact, it’s difficult for Mackey to choose just one of his projects to talk about. He begins describing one, then interrupts himself to mention another. He falls silent for a moment, mentally flipping through all of the projects he wants to share.

PHOTO BY JOHN ULAN

RESEARCH ROADBLOCKS Few understand the complexities of the disease better than cancer researchers. Strategies to target treatment to certain cancers have saved lives, while other cancers, such as pancreatic and brain cancer, remain a mystery. In the quest to understand, diagnose and treat cancers, scientists, physicians, universities and funding agencies are coming to realize something that patients such as Prochazka have known all along: when it comes to cancer, you can’t do it alone. There is a growing realization that a “race to be first” model of research, the romantic image of a lone researcher in a lab finding “the cure,” will not work. The best approach to tackling cancer now appears to lie in more — and better — collaboration from the moment a research project is conceived. This is the crux of what’s known as “translational research.” It involves, in part, breaking down disciplinary barriers to build teams of experts from different fields who share ideas, resources and results. Translational research also refers to “translating” scientific discoveries from the laboratory to the treatment of patients, sometimes called “bench to bedside.” It’s a feedback loop of discovery and treatment, in which basic cancer research leads to new treatments and better patient outcomes, which, in turn, help direct further avenues of research. When a biochemist, an oncologist, a biomedical engineer, a nutritional scientist and a biostatistician work on a research project together, they bring different questions, expertise, insights and points of view to bear on the problem. This makes the research process more effective, ideally shortening the time it takes for new discoveries to move through

the research pipeline from an experiment at the lab bench to detection or treatment at the cancer patient’s bedside. [Editor’s note: Read about one such translational research discovery on page 2.] At its core, translation is about clearing roadblocks on the twisting and expensive pathway from basic scientific discovery to patient care. In an academic setting, this means breaking out of departmental silos and separate buildings. It means establishing ways for scientists in the lab to share what they know with health practitioners who treat patients — and vice versa. It means creating opportunities for collaborative research projects that tap into a research university’s greatest strength: its wealth of expertise in diverse disciplines. “As a basic scientist I can do amazing things in the lab and have breakthroughs that get published in Nature, but they may have no impact on patients because I don’t have the knowledge or resources to bring it to the clinical next step,” says John Lewis, who holds the Frank and Carla Sojonky Chair in Prostate Cancer Research at the U of A and leads a team in translational prostate cancer research. “We have to start using a broad spectrum of experts with diverse skills to tackle this in a very different way,” says Stephen Robbins, scientific director of the Institute of Cancer Research in the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), which funds more than a quarter of all cancer research in the country — the single largest investor. It’s not that collaboration is new. What is new is how broadly the network of collaboration stretches, the diversity of the collaborators and how early in the process the connections are formed. Funding models, research facilities and even purpose-built buildings are shifting to support this integrated, team-based approach.

Cancer physician John Mackey (left) and biochemist Ing Swie Goping are studying why some breast and ovarian cancer tumours respond to treatment while others show resistance.

newtrail spring 2015

23

One of Mackey’s most promising lines of inquiry is a collaboration with U of A associate professor of biochemistry Ing Swie Goping. They’re striving to understand why some patients respond to chemotherapy while others show resistance. Specifically, they are looking into taxanes, aggressive chemotherapy drugs used in the treatment of breast and ovarian cancers. Despite the highly toxic therapy, cancer relapses in nearly 40 per cent of breast cancer patients and 70 per cent of ovarian cancer patients. When Goping proposed a collaboration, Mackey was eager to be involved, having seen his patients suffer from the harmful side-effects of taxane therapy, which in some cases can even cause death. “As doctors, if we don’t understand the biology, our treatment strategies will simply be empiric, like randomly throwing darts at a wall without knowing the direction to aim,” he says. The team is developing an antibody-based diagnostic kit that will help breast cancer patients and their doctors determine whether the difficult treatment might be beneficial. Goping discovered that a protein called BAD (Bcl-2-associated death promoter) acts as a predictive biological marker that indicates whether a patient will respond to taxane treatment. Since taxanes require BAD in order to eliminate the cancer cell, patients with the protein in their tumours respond better to the therapy. The team is continuing to test its hypothesis in larger numbers of tumour specimens but, based on the findings, the biomarker could potentially spare hundreds of Albertans from having to undergo this difficult treatment without any benefit. For patients whose tumours have high levels of the BAD protein, the hope is that they will be more willing to soldier through the taxane therapy with the odds in their favour. Knowing they have the biomarker would give them a reason to hope. The project demonstrates what basic research and clinical medicine can achieve through collaboration, when people from different disciplines contribute a variety of insights and approaches. “Collaboration was absolutely necessary for this project to move forward, for us to expand our knowledge and reach our conclusion,” Goping says. As a medical oncologist who sees patients on a daily basis, Mackey recognized the need for a diagnostic tool to help target treatment. The tumour bank he co-founded provided samples for the research on taxanes. (Open to all researchers, the biorepository has blood and tissue samples of more than 40 types of cancer from more than 20,000 participants.) Pathologist Judith Hugh, another key member of the translational team, can “read” each tumour sample and determine its grade and diagnosis. Cancer surgeon Todd McMullen, ’91 BSc(Spec), ’97 PhD, who also has a background in biochemistry, provides surgical input to help acquire specimens. Biostatistician John Hanson, ’64 BSc, ’68 MSc, analyzes vast amounts of research data and interprets the results. Mackey is enthusiastic about the depth and breadth of talent with which he works. “Most of what I do is like skating with Gretzky,” he says. “You get a few goals, but most are because of the talented people you’re collaborating with. I work with people who know things I don’t know and that’s really where the sparks fly and the advances happen. When people approach the same problem from different directions, patients win.” 24

newtrail.ualberta.ca