5 minute read

POLICY

THE ECONOMICS OF FLATTENING THE CURVE

By MAHA KHAN YIFAN MAO

Advertisement

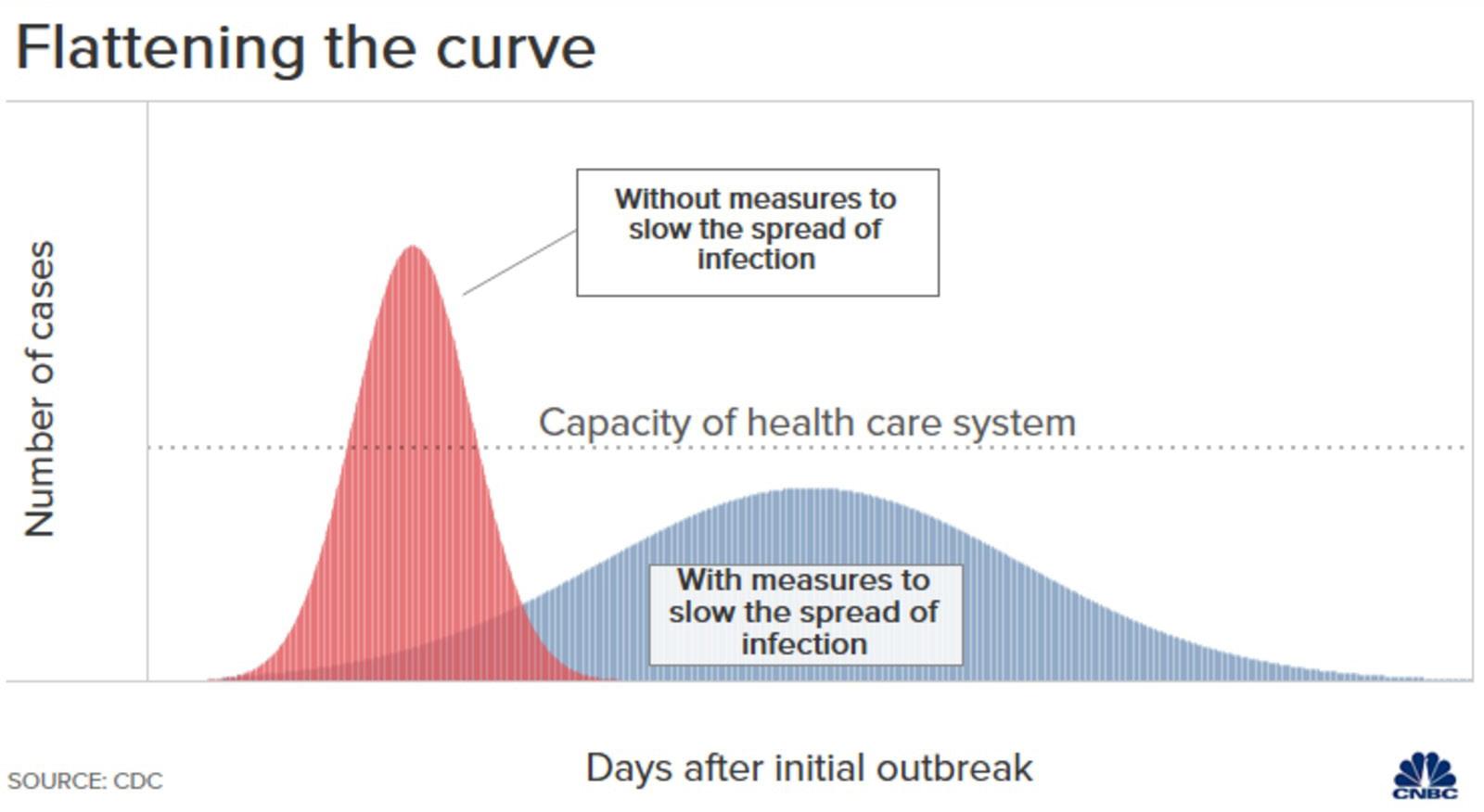

“Flatten the curve.” This was the most widely emphasized message to the general public in mid-March before the peak of COVID-19 in the United States. The importance of flattening the curve is apparent when evaluating the capacity of the healthcare system in relation to the U.S. population. It is equally important to consider the economic reasons underlying the regulations that have led to this specific capacity level. The need to promote this message became clear throughout March as early estimates showed that about 4 million Americans would be infected by May 13. Given that there are 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 Americans, it was obvious that there were not nearly enough physical beds let alone supplies and medical workers to care for the number of Americans projected to be hospitalized from COVID-19 given data from China and Italy. The frightening discrepancy between the estimated number of Americans being infected and the capacity of the U.S. healthcare system drove public health officials to begin emphasizing the need to “flatten the curve” and follow social distancing guidelines. Although these measures are not expected to ensure that the U.S. healthcare system will be able to handle all COVID-19 cases, the effort will surely help reduce the amount of serious cases that are turned away or the rationing of medical resources between dying patients.

The intersection of basic economics and the healthcare system is not usually discussed in news about the state of the U.S.’s “broken” healthcare system. However, just as in the financial markets, there are certain key players and incentives to keep in mind when trying to understand the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the healthcare system. First, the healthcare system comprises 11% of the U.S.’s labor force, and spending on the healthcare sector makes up 24% of total government spending. Consumers in the healthcare system are patients, who reportedly spend 8.1% of consumer expenditures on healthcare, while the firms are hospitals, private practices, and payors. Although these economic actors play roles of different magnitudes in contributing to the capacity of the healthcare system, the most obvious predicted effect of COVID-19 on the healthcare system was the shortage of hospital beds. This shortage was directly caused by how our healthcare

system has been regulated and shaped from its core.

Before the onset of COVID-19, rural hospitals in America were already financially strained. A February 2019 report by Guidehouse of 430 hospitals in 43 states found that one in five rural hospitals was at high risk of closing; a number of hospitals that represented 21,547 staffed beds. The possible effects of these hospitals closing down before the outbreak or during would include widening healthcare disparities and decreasing healthcare access, especially in rural areas where there are already fewer hospitals and resources. The contrast between hospitals in rural and urban areas is quite stark considering that NYC’s hospital system has 26,000 beds, which is approximately the same number of beds at all of these at-financial

risk rural hospitals combined. However, the projected rapid spread of COVID-19 in densely populated cities would still keep NYC underprepared for the outbreak. The important question is why healthcare systems in both rural and urban areas are less than prepared to handle pandemics.

One of the main drivers of the discrepancy in U.S. hospital beds in comparison to the population is lack of adequate federal regulations and oversight of hospital mergers and acquisitions. In the past decade alone, there have been over 680 hospital mergers. Numerous hospitals have been closed down in various communities nationwide, likely increasing the distance and costs associated with receiving medical care for many people who now do not live in close range to a hospital. The Federal Trade Commission has not opposed any of these mergers because of a rule that allows hospitals to merge without challenge if one of the hospitals has less than 100 beds. This lack of oversight allows the healthcare system to be controlled by business interests rather than what is best for health equity in society.

State-level regulations have also dramatically affected the development of new hospitals to expand the system’s capacity. Specifically, Certificate of Need (CON) laws require a state agency to oversee and approve any major capital spending related to healthcare facilities. These laws prevent more hospitals from opening up because they are based on the economic assumption that an increase in hospital beds will cause healthcare price inflation. They have also

Source: Guidehouse Report

contributed to extreme hospital bed shortages in some states, but many governors took action to prevent these laws from slowing down the COVID-19 response. 13 out of 35 states with CON legislation suspended the laws via executive orders, while six states expedited the process associated with CON laws. Suspension of these laws has allowed places like NYC to expand their healthcare system capacity and make temporary ICU units in convention centers and nursing homes.

Although America’s free market capitalist system drives its healthcare capacity to a size where demand equals supply rather than a size fit to handle a surge in demand, it is important to understand the tradeoffs with this system. The inflexible, physical constraints of the healthcare system make it clear that the most effective way to lessen the devastating effects of the pandemic and to ensure that the healthcare system is not overwhelmed is by adhering to social distancing measures. Nevertheless, the pressure of the pandemic on the healthcare system capacity has made it clear that the system cannot be reformed without tackling the economic regulations that have enabled healthcare inequities and underpreparedness for the pandemic in America.

Barron, Seth. “New York’s Calm Before the Storm?”

City Journal, March 20, 2020. https://www. city-journal.org/coronavirus-crisis-nyc-healthcare-system. “CON-Certificate of Need State Laws.” National

Conference of State Legislatures, 1 Dec. 2019, www.ncsl.org/research/health/con-certificateof-need-state-laws.aspx. Flynn, Andrea, and Ron Knox. “Perspective | We're Short on Hospital Beds

Because Washington Let Too Many

Hospitals Merge.” The Washington

Post, WP Company, 8 Apr. 2020, www. washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/08/ were-short-hospital-beds-because-washingtonlet-too-many-hospitals-merge/. Fournier, Deborah, et al. “Anticipating Hospital

Bed Shortages, States Suspend Certificate of

Need Programs to Allow Quick Expansions.”

The National Academy for State Health Policy, 16 Apr. 2020, nashp.org/anticipating-hospitalbed-shortages-states-suspend-certificate-ofneed-programs-to-allow-quick-expansions/. Meredith, Sam. “Flattening the Coronavirus

Curve: What This Means and Why It Matters.”

CNBC, CDC Image, 19 Mar. 2020, www.cnbc. com/2020/03/19/coronavirus-what-doesflattening-the-curve-mean-and-why-it-matters. htmel. Mosley, David, and Daniel DeBehnke. “One-in

Five U.S. Rural Hospitals at High Risk of

Closing.” Advisory, Consulting, Outsourcing

Services, Report and Image. Feb. 2019, guidehouse.com/-/media/www/site/insights/ healthcare/2019/navigant-rural-hospitalanalysis-22019.pdf. Nunn, Ryan, et al. “A Dozen Facts about the

Economics of the US Health-Care System.”

Brookings, 10 Mar. 2020, www.brookings.edu/ research/a-dozen-facts-about-the-economicsof-the-u-s-health-care-system/. Specht, Liz. “Simple Math Offers Alarming

Answers about Covid-19, Health Care.”

STAT, March 10, 2020. https://www.statnews. com/2020/03/10/simple-math-alarminganswers-covid-19/.