18 minute read

THE JOURNEY TO mARS STARTS HERE ON EARTH JOALDA mORANCY

COVID-19’S DISPROPORTIONATE ImPACT ON COmmUNITIES OF COLOR: ImPLICATIONS FOR VACCINE DEVELOPmENT AND DISTRIBUTION ANNIE QIAO

The omnipresence of masks covering the faces of strangers and friends alike. Signs taped to the windows of businesses reading “no masks, no service.” Gatherings limited to ten people or less, social distancing recommended. And, in Chicago, an unsettling silence dimming its once bustling and lively streets as people adjust to life in the middle of a pandemic. As 2020 came to a close, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States continued to rise higher and higher, with the nation accounting for 231,000 of the 1.2 million deaths and 9.21 million out of the 46.2 million cases worldwide [1]. Moreover, the virus continues to disproportionately affect people of color, especially Hispanic and Black communities. For example, in Illinois, out of those who specified their race on a recent survey, Hispanic and Black Americans accounted for 47.8% of confirmed cases despite only making up around 32% of the population combined [2]. In addition, both groups had an age-adjusted mortality rate 3.2 times greater than that of white Americans infected with COVID-19 [3]. Consequently, as scientists scramble to develop a vaccine for the coronavirus, there must be a corresponding conversation about the access of the future vaccine to communities of color.

Advertisement

From provider stereotyping to inequitable access to health insurance, it is no secret that racial disparities persist in the United States healthcare system. In fact, racism itself negatively impacts physical health by creating chronic stress. Allostatic load can best be explained as the physical cost of chronic stressors that an individual faces throughout their lifetime. When the body systems responsible for regulating stress are continuously perturbed, there can be negative implications for long-term health status [4].

Using biomarkers—objective biological indicators, such as blood pressure and heart rate, that measure the presence or progress of a disease—researchers found that higher levels of perceived discrimination for Black adolescents predicted higher allostatic loads, stress hormones, and blood pressure at age 20 [4]. Another study conducted in 2012 found that Black Americans tended to have higher allostatic loads than white Americans and that increases in the allostatic load score were associated with increased cardiovascular and diabetes-related mortality [5]. Consequently, in part due to chronic stress, Black communities have elevated rates of hypertension and diabetes. These pre-existing conditions can, in turn, cause COVID-19 to manifest more severely [6]. In fact, a national report published in August by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that people of color were around five times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than white people [7].

Disproportionately impacted by the virus, it is crucial that minority communities are represented in vaccine trials. In fact, immunologist Anthony Fauci recommended that minorities should be overrepresented in trials because they have been hit the hardest by the coronavirus (Cohen). However, according to the FDA, nearly 3 out of 4 subjects in trials for novel drugs last year were white [8], revealing a broader shortcoming in clinical research to recruit diverse groups of participants for drug trials. Underrepresentation of minorities in clinical trials leaves unanswered questions on the effects of the vaccines on these communities and could foster distrust about the vaccine, potentially hindering distribution efforts down the line.

At a series of listening sessions organized by the FDA, people of color voiced a range of concerns regarding the vaccine, including “I would not be first in line and I would want to see some data” and “We are not going to be guinea pigs again” [9]. This distrust stems from a context much broader and more complex than just the COVID-19 vaccine trials.

The Tuskegee Experiment, in particular, is one of the most egregious examples of the American scientific community abusing minorities in a medical research setting [10]. In a clinical study that spanned from 1932 to 1972, 600 Black Americans living in Macon County, Alabama were misinformed of a study regarding the natural history of untreated syphilis, as they were told that they were being treated for “bad blood,” a colloquial term for illnesses like syphilis, anemia, and fatigue that were major causes of death for southern Black Americans at the time. Throughout the trial, both information about the nature of the study and access to treatment once penicillin was discovered to be an effective antibiotic were withheld. When the fact that the scientists had knowingly misinformed participants and withheld treatment came to light, it further damaged the relationship between medical authorities and the Black community, generating deep distrust for research projects backed by the federal government in particular [15]. This historical context is critical to understanding the challenge of recruiting participants for vaccine studies today and further illuminates why people may be hesitant to receive the vaccine.

So far, community leaders have played an important role in the push towards building trust in the COVID-19 vaccine trials. For example, the

Courtesy of Eva Marie Uzcategui/Getty Images

When a vaccine for COVID-19 is eventually distributed, both the vaccine itself and information about the trials must be accessible to people of color.

Courtesy of Spencer Platt/Getty images COVID-19 continues to disproportionately affect communities of color, especially Black Americans.

New York Times recently followed pastor Father Paul as he attempted to have such conversations with people in his predominantly Black Pittsburgh neighborhood [11]. A trusted figure in the community, he was able to communicate transparently about the vaccine process and ultimately increased local participation in the vaccine registry [11]. Meanwhile, in Chicago, response teams like the nonprofit West Side United have dedicated themselves to leveraging resources to improve health equity, successfully opening city testing sites in priority neighborhoods, distributing informational pamphlets, and securing $3.1 million in grants for COVID-19 relief [12]. Such efforts will eventually transition to support the Chicago Department of Public Health’s Healthy Chicago 2025 plan to address health disparities in the city more long-term [12].

As of November 18, Pfizer and BioNTech recently concluded their phase 3 study for the COVID-19 vaccine trial, announcing a 95% efficacy rate for their vaccine. They have reported that 42% of participants in their trials had “racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds” [13]. After sharing data with other countries and getting the vaccine officially approved, the companies project that they will manufacture over 1.3 billion doses of their vaccine worldwide by the end of 2021 [14]. As clinical trials draw to a close, we must turn our attention to equitable distribution efforts, learning from leaders such as Father Paul in order to effectively and efficiently get a vaccine into those communities affected most by the virus.

References

1. “Covid in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 3 Mar. 2020, www. nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html.

2. “COVID-19 Statistics.” COVID-19 Statistics | IDPH, www.dph.illinois.gov/ covid19/covid19-statistics.

3. “COVID-19 Deaths Analyzed by Race and Ethnicity.” APM Research Lab, www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deathsby-race.

4. Brody, Gene H., et al. “Perceived Discrimination Among African American Adolescents and Allostatic Load: A Longitudinal Analysis With Buffering Effects.” Child Development, vol. 85, no. 3, 2014, pp. 989–1002., doi:10.1111/ cdev.12213.

5. Duru, O Kenrik et al. “Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 104,1-2 (2012): 89-95. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30120-6.

6. “Certain Medical Conditions and Risk for Severe COVID-19 Illness.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/ people-with-medical-conditions.html.

7. Artiga, Samantha and Corallo, Bradley. “Racial Disparities in COVID-19: Key Findings from Available Data and Analysis.” KFF, 17 Aug. 2020, www. kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-covid-19-key-findings-available-data-analysis/.

8. Hopkins, Jared S. “Covid-19 Vaccine Trials Have a Problem: Minority Groups Don't Trust Them.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 5 Aug. 2020, www.wsj.com/ articles/covid-19-vaccine-trials-have-aproblem-minority-groups-dont-trustthem-11596619802.

9. Wamsley, Laurel. “Researchers Find Doubts About COVID-19 Vaccine Among People Of Color.” NPR, NPR, 22 Oct. 2020, www.npr. org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/10/22/926813331/researchers-find-doubts-about-covid-19-vaccine-among-people-of-color. 10. “More People Of Color Needed In COVID-19 Vaccine Trials.” NPR, NPR, 23 Aug. 2020, www.npr. org/2020/08/23/905181731/more-people-of-color-needed-in-covid-19-vaccine-trials.

11. Hoffman, Jan and Lee, Chang W. “Vaccine Trials Struggle to Find Black Volunteers.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 7 Oct. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/10/07/health/coronavirus-vaccine-trials-african-americans. html.

12. “COVID-19 Health Equity Initiatives: Chicago Racial Equity Rapid Response Team.” American Medical Association, www.ama-assn. org/delivering-care/health-equity/ covid-19-health-equity-initiatives-chicago-racial-equity-rapid.

13. Callaway, Ewen. “What Pfizer's Landmark COVID Vaccine Results Mean for the Pandemic.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 9 Nov. 2020, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-02003166-8.

14. “Pfizer and BioNTech Conclude Phase 3 Study of COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate, Meeting All Primary Efficacy Endpoints.” Pfizer, www.pfizer.com/ news/press-release/press-release-detail/ pfizer-and-biontech-conclude-phase-3study-covid-19-vaccine.

15. “Tuskegee Study - Timeline.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 Mar. 2020, www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

16. Cohen, Elizabeth. “Moderna Increases Minority Numbers in Its Vaccine Trial, but Still Not Meeting Fauci's Goal.” CNN, Cable News Network, 29 Aug. 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/08/29/ health/moderna-coronavirus-vaccine-minorities-goal/index.html.

17. O'Connor, Mary I. “To Build Trust on COVID Vax in Black Community, Learn From the Flu.” Medical News and Free CME Online, MedpageToday, 16 Nov. 2020, www.medpagetoday.com/ infectiousdisease/covid19/89695.

18. Peek, M Kristen et al. “Allostatic load among non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and people of Mexican origin: effects of ethnicity, nativity, and acculturation.” American journal of public health vol. 100,5 (2010): 940-6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.129312.

19. Stewart, Ada. “Minorities Are Underrepresented in Clinical Trials.” AAFP Home, 4 Dec. 2018, www. aafp.org/news/blogs/leadervoices/entry/20181204lv-clinicaltrials.html.

Annie Qiao is a firstyear planning to major in HIPS. She is on the pre-medical track and was a member of and editor for her high school newspaper.

THE FUTURE OF A CATASTROPHE-RIDDEN NUCLEAR ENERGY NIkHIL kUmAR

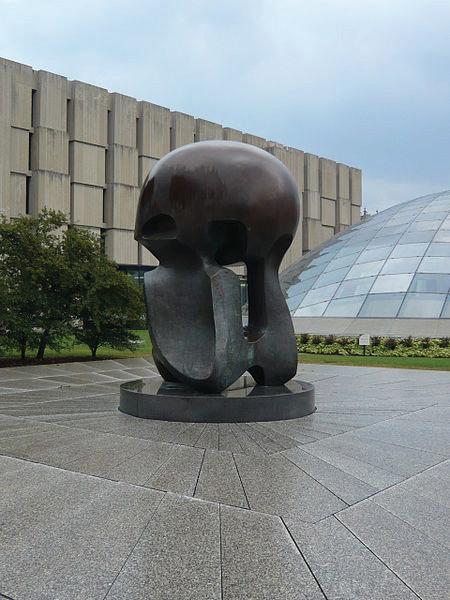

of one nucleus can split another and continually as 120 gallons of oil, and cost, where producing a produce large amounts of heat, as long as fuel ex- kilowatt-hour of electrical energy costs approxiists [5]. The first practical nuclear project was at mately $0.02438 for nuclear, but $0.03541 for fossil the University of Chicago in 1942, where a team fuel steam plants [9]. of scientists, led by Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, created the world’s first man-made, self-sustaining However, nuclear energy does have its disadvantagnuclear fission chain reaction in a reactor called es. One major problem is the production of radioChicago Pile-1 [6]. Fer- active waste, which occurs when the larger atoms mi’s experiment would are split up into smaller radioactive materials. Rago on to inspire innova- dioactive waste is produced in small quantities and The phrase “nuclear energy” strikes a nerve in most people on the planet. It can bring to mind images of war, death and destruction. Some remember the arms race of the Cold War and related events like the Cuban Missile Crisis, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear war [1]. Others may remember the sheer power of the nuclear warheads detonated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, costing more than 100,000 lives [2]. Others may recall Three-Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima for their explosive nuclear meltdowns that together led to the deaths of more than 2,300 people and irreversibly changing the lives of hundreds of thousands more [3]. In the United States specifically, public support for nuclear energy production mirrors these events, most recently falling to a 20 year low of 44% in 2016 in the 5 years following Fukushima. It is therefore surprising, then, that since its inception, around half of all Americans have supported nuclear power [4]. This raises a few important questions: Why does nuclear energy retain its appeal today, and what place does nuclear energy have in the future of energy production, considering the risks it poses to society? To understand why nuclear energy has so much potential, it is important to understand how it is produced and how it started. Nuclear energy is produced by a process called NUCLEAR ENERGY IS PRODUCED BY A PROCESS CALLED NUCLEAR FISSION, WHICH OCCURS WHEN NEUTRONS BOmBARD THE NUCLEI OF LARGE ATOmS LIkE URANIUm, CAUSING THE NUCLEI TO SPLIT APART. “ Statue at The University of Chicago commemorating the world’s first man-made, self-sustaining nuclear fission chain reaction in a reactor. nuclear fission, which occurs when neutrons bombard the nuclei of large atoms like uranium, causing the nuclei to split apart. This process generates an immense amount of energy in the form of heat, used to convert water to steam, which pushes turbines connected to a generator. What makes nuclear energy special, however, is the chain reaction, in which the neutrons generated from the splitting tions in nuclear energy such as the production of electricity from fission in 1951 and the first nuclear plant in 1954 [5]. Nuclear energy was seen as unique, being a form of clean energy, which means it produces no emissions of greenhouse gases, while generating a tremendous amount of energy from little fuel. These innovations were surprising, however, since they were discovered after the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite the devastation this technology had caused, scientists and governments were determined to use the same technology for peaceful and more positive purposes, dedicating large investments to create a promising new industry [7]. On the surface, nuclear energy appears to be the solution to our environmental concerns when pitted against fossil fuels. First and foremost, nuclear energy is a source of clean energy. In the United States, nuclear energy is the largest source of clean power, generating more than 800 billion kilowatt-hours of energy each year. When that same amount of electricity is generated by fossil fuels, more than 470 million metric tons of carbon emissions are produced. Generating this energy through nuclear means would be equivalent to taking 100 million cars off the road in terms of carbon emissions avoided [8]. While the primary byproduct of nuclear energy is steam, fossil fuels produce pollutants with damaging effects on the environment, such as greenhouse gases (which contribute to global warming) and toxic materials like sulfur dioxide, arsenic, cadmium and mercury (which adversely affect indigenous flora and fauna). Nuclear also comes out on top in terms of efficiency, where 0.1 ounce of nuclear fuel produces the same energy has standard containment procedures to prevent interaction with the environment, allowing nuclear energy to maintain its clean energy status. The levels of radiation produced by most radioactive waste is low, so materials like bitumen and concrete can effectively block the effects of low level radioactive waste [10]. However, if radioactive waste is leaked, the radiation can have carcinogenic or mutagenic effects on nearby organisms which can irreversibly affect the surrounding ecosystems [11]. Another major problem with nuclear energy is the time and effort required to manufacture a nuclear plant. High capital costs, the necessity of regulatory approvals, and construction delays are just some of the reasons that make nuclear energy a poor shortterm solution to energy problems and high carbon emissions [8]. In 2020, the United States was involved in the construction of just 2 reactors and closed down 37 pre-existing reactors, possibly due to the reasons mentioned above, along with lower public support [12]. Perhaps the most prominent reasons for public distrust in nuclear energy, are the power plant accidents that rocked the world. The disastrous events at Chernobyl and Fukushima permanently tainted the legacy of nuclear energy. In 1986, a steam explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear plant, located near the now-abandoned city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine, released at least 5% of the radioactive reactor core into the environment. The blast caused 38 plant worker deaths (28 from acute radiation syndrome), 6,500 cases of thyroid cancer (with 15 known fatalities), and the relocation of 350,000 people [13]. The event caused a period

IN THE UNITED STATES, NUCLEAR ENERGY IS THE LARGEST SOURCE OF CLEAN POWER, GENERATING mORE THAN 800 BILLION kILOWATT-HOURS OF ENERGY EACH YEAR[, WHICH IS] EQUIVALENT TO TAkING 100 mILLION CARS OFF THE ROAD IN TERmS OF CARBON EmISSIONS AVOIDED [8].

Damaged nuclear reactor buildings left from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

of low support for nuclear energy lasting until the 2000s [4]. Just when the world had begun to reconsider nuclear energy as a viable energy alternative to fossil fuels, on March 11, 2011, Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was hit by a magnitude 9.0 Credit: Wikimedia Commons earthquake. While the power plant survived the earthquake and moved to emergency power, a 15-meter high tsunami wiped out both the cooling systems and the power supply, leading to three nuclear meltdowns and the release of high doses of radiation. While there were no deaths or cases of radiation sickness from the meltdown, 100,000 people were forced to evacuate, resulting in 2259 evacuation-related deaths [3]. In both cases, the potentially devastating consequences of nuclear energy production were brought to public attention.

Despite the tragedies following nuclear energy since its inception, polls suggest that public opinion about this controversial energy source may be starting to change. A Gallup poll conducted in 2019, showed that 49% of Americans supported nuclear power production. According to the same source, this marked a distinct increase from 2016 of 44% support, the A GALLUP POLL CONDUCTED IN lowest point in over 25 years [14]. Anoth2019, SHOWED THAT 49% OF er literature review AmERICANS SUPPORTED NUCLEAR supports this idea, claiming that AmerPOWER PRODUCTION. ican support for nuclear energy was rising for the first time since 2010 (before Fukushima’s disaster) [4]. These studies coincided with another poll in 2019 which showed 60% of Americans supported reductions in fossil fuel usage and a vast majority supported expansion of renewable energy [15]. These data suggest that as time passed after nuclear disasters, the American people began to accept nuclear energy as a way to fight back against climate change and global warming. On top of this, legislators on both sides of the aisle appear to finally be on the same page, with Republican leaders already in support and the 2020 Democratic platform recently supporting nuclear technologies to prevent carbon emissions [16]. While early drafts of the Green New Deal (a non-binding resolution to counter climate change) seemed to oppose nuclear plants, a major sponsor of the bill, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, clarified that nuclear could remain a possibility [17]. While nuclear power plant production can be set aside temporarily due to its risks, the government and private investors should take advantage of the opportunity to invest in nuclear energy research, to not only regain public support, but also drive development of safer and cheaper nuclear technologies.

Today, new innovations in renewable energy are being developed across the planet. Solar energy was shown in October 2020 to have finally become the cheapest form of energy in history [18]. It may be tempting, considering all the problems associated with it, to end all efforts toward nuclear energy production and push forward with less risky forms of energy. Nuclear research, however, is experiencing major advances simultaneously. India is making an ambitious plan to produce thorium reactors which could produce more energy with safer longterm nuclear waste [19]. Controlled nuclear fusion (which uses the same energy production method as the Sun) is another innovation on the horizon which could enable vast amounts of clean energy [20]. Until these projects reach commercial viability, despite major strides in other forms of clean energy, research in nuclear energy must continue and be promoted. Despite scaling back nuclear energy production, we must never forget the positive potential of one of the greatest forces on Earth.

References

1. “The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/cuban-missile-crisis.

2. “Total Casualties.” The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | Historical Documents, Atomicarchive.com, www. atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/med/med_chp10. html.

3. “Fukushima Daichii Accident.” World Nuclear Association, May 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident. aspx.

4. Gupta, Kuhika, et al. "Tracking the nuclear ‘mood’ in the United States: Introducing a long term measure of public opinion about nuclear energy using aggregate survey data." Energy Policy 133 (2019): 110888.

5. Nunez, Christina. “What Is Nuclear Energy and Is It a Viable Resource?” Nuclear Energy Facts and Information, National Geographic, 29 Mar. 2019, www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/energy/reference/nuclear-energy/.

6. “Nuclear Energy.” UChicago Arts, The University of Chicago, 12 Oct. 2015, arts.uchicago.edu/public-art-campus/browsework/nuclear-energy.

7. Outline History of Nuclear Energy.” World Nuclear Association, Nov. 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/ current-and-future-generation/outline-history-of-nuclear-energy.aspx.

8. “Advantages and Challenges of Nuclear Energy.” Energy.gov, www.energy.gov/ne/articles/advantages-and-challenges-nuclear-energy.

9. Sen, Debashree. “Nuclear Energy Vs. Fossil Fuel.” Sciencing, 2 Sept. 2019, sciencing.com/about-6134607-nuclear-energy-vs-fossil-fuel.html.

10. “Radioactive Waste Management .” World Nuclear Association, Feb. 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/ nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-wastes/radioactive-waste-management.aspx.

11. Rinkesh. “Dangers and Effects of Nuclear Waste Disposal.” Conserve Energy Future, 25 Dec. 2016, www.conserve-energy-future.com/dangers-and-effects-of-nuclear-waste-disposal. php. 12. Tiseo, Ian. “Number of under Construction Nuclear Reactors Worldwide 2020.” Statista, Ian Tiseo, 2 Sept. 2020, www. statista.com/statistics/513671/number-of-under-construction-nuclear-reactors-worldwide/.

13. “Chernobyl Accident 1986.” World Nuclear Association, Apr. 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/chernobyl-accident.aspx.

14. Reinhart, RJ. “40 Years After Three Mile Island, Americans Split on Nuclear Power.” Gallup.com, Gallup, 20 Nov. 2020, news.gallup.com/poll/248048/years-three-mile-island-americans-split-nuclear-power.aspx

15. McCarthy, Justin. “Most Americans Support Reducing Fossil Fuel Use.” Gallup.com, Gallup, 20 Nov. 2020, news.gallup. com/poll/248006/americans-support-reducing-fossil-fuel.aspx.

16. Nuclear News Staff. “After Decades, Democrats' Platform Endorses Nuclear Energy.” American Nuclear Society, 25 Aug. 2020, www.ans.org/news/article-463/after-48-years-democrats-endorse-nuclear-energy/.

17. Meinetz, Bob. “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: Green New Deal ‘Leaves the Door Open’ for Nuclear Energy.” Energy Central, 26 May 2020, energycentral.com/c/cp/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-gr een-new-deal-leaves-door-open-nuclear-energy.

18. Shahan, Zachary. “Solar Power = ‘Cheapest Electricity In History.’” CleanTechnica, 26 Oct. 2020, cleantechnica. com/2020/10/26/solar-power-cheapest-electricity-in-history/.

19. Tagotra, Niharika. “India's Ambitious Nuclear Power Plan – And What's Getting in Its Way.” The Diplomat, 9 Sept. 2020, thediplomat.com/2020/09/indias-ambitious-nuclear-powerplan-and-whats-getting-in-its-way/.

20. “Nuclear Fusion.” World Nuclear Association, July 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/nuclear-fusion-power.aspx.

Nikhil Kumar is a second year student at the University of Chicago, planning on pursuing a major in Biology/Pre-med with a minor in Cinema and Media Studies. He is especially interested in regenerative medicine and physiology which he hopes to research in the future. Apart from academics, Nikhil is a member of the UChicago Quiz Bowl team and the Table Tennis club on campus, in addition to writing for Triple Helix. Nikhil likes to spend his free time in quarantine perfecting his baking skills, writing parts of his never-ending novel or playing video games with friends.