UCLA Ed&IS

STATE OF CRISIS

Dismantling Student Homelessness in California

32%

OF PRINCIPALS

REPORTED THAT ALL THEIR TEACHERS HAD THE NECESSARY TECHNOLOGY WHEN THEIR SCHOOL TRANSITIONED.

32%

REPORTED THAT ALL THEIR TEACHERS HAD THE NECESSARY TECHNOLOGY WHEN THEIR SCHOOL TRANSITIONED.

U.S. Public High Schools and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spring 2020

UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access national survey of high school principals looking at the response of educators to COVID-19 pressures.

PAGE 16

How Innovators around the World are Overcoming Inequality and Creating the Technologies of Tomorrow

PAGE 20

Embodying the principles of individual responsibility and social justice, an ethic of caring, and commitment to the communities we serve.

2 Message from the Dean

4 State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California

A report from the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools on the crisis of student homelessness in California.

10 The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom

Excerpts from Professor Eddie R. Cole’s new book looking at the history of college presidents during the civil rights era. Q&A with Professor Cole.

16 Learning Lessons: U.S. Public High Schools and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spring 2020

UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access national survey of high school principals looking at the response of educators to COVID-19 pressures.

20 Beyond the Valley: How Innovators around the World are Overcoming Inequality and Creating Technologies of Tomorrow

Excerpt from Information Studies Professor Ramesh Srinivasan’s book looks at how we can create a more democratic internet.

25 Lost Opportunities: How Disparate School Discipline Continues to Drive Differences in the Opportunity to Learn

A national study on the impact of school discipline from the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

28 A Collection and its Many Relations and Contexts: Constructing an Object Biography of the Police Historical/Archival Investigative Files

Excerpt from an article by Kathy Carbone, postdoctoral scholar and lecturer, UCLA Department of Information Studies.

MAGAZINE OF THE UCLA SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND INFORMATION STUDIES

FALL 2020

Tina Christie, Ph.D.

UCLA Wasserman Dean & Professor of Education, UCLA School of Education and Information Studies

Laura Lindberg Executive Director External Relations, UCLA School of Education and Information Studies

EDITOR

Leigh Leveen Director, Communications UCLA School of Education and Information Studies lleveen@support.ucla.edu

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Joanie Harmon Director, Campaign & Development Communications, UCLA School of Education and Information Studies harmon@gseis.ucla.edu

John McDonald Director, Sudikoff Family Institute jmcdonald@gseis.ucla.edu

DESIGN

Robin Weisz Design

© 2020, by The Regents of the University of California gseis.ucla.edu

We live in extraordinary times. In the span of nine months we have witnessed devastation from a virus unknown for a hundred years. Thousands have lost their lives and many more have suffered ill health. In these trying times we grieve with families who have lost loved ones. We are told it will get worse. Hence, we seek fortitude and strength to cope with further challenges ahead. With the development of a vaccine, there is now some light in these dark times.

These months have been dark for yet another reason—one that strikes at the core of human dignity. We have witnessed brazen and blatant brutality from those entrusted to protect us. And more perniciously, this inhumanness has been perpetrated systematically along racial

lines. As a result, we witnessed unprecedented social unrest and unrelenting demonstrations the world over for justice and moral reckoning. These events have undeniable ramifications not just for our social conscience but, I believe, for the role of a university, especially a public, land grant institution.

In the sometimes rarified towers of academia it is easy to lose touch with lived experiences and realities especially those painful and uncomfortable. It is easy and perhaps more comfortable to spin webs and remain suspended in theory-speak safely away from harsh and harrowing actualities. This disconnect is further exacerbated by university cultures politely denigrating research addressing real social problems as “applied.” Perhaps it is made worse by reward structures. But surely the best of scholarship is that which is theoretically sound and rises to the challenge of contributing to social upliftment—to the resolute realization of cherished human goods and ideals.

It is precisely this kind of scholarship that is represented in these pages—scholarship that is timely and unreservedly responsive to real issues but scholarship that is at once rigorous and meticulous. I commend the faculty represented here and the faculty in UCLA’s School of Education and Information Studies more generally for taking up the challenge to advance the profoundly human and communal good through their scholarship.

The work of the faculty in the School of Education and Information Studies is guided by a vision of human good and by an unwavering faith in the possibility of human progress through knowledge and immersed inquiry. Our research is driven by an ethic of responsibility for the furtherance of this human good through engaged scholarship—an ethic that is even more relevant today in our trying and challenging times—an ethic moreover which, I believe, eminently befits a public university entrusted with advancing this very good.

The emblem of the University of California includes a translation of the iconic Latin phrase, Fiat Lux, “Let There Be Light.” It also includes a five-pointed star at the top of the emblem with rays of light emanating from it, symbolizing the discovery and dissemination of knowledge. While we may value knowledge in all its forms, even that pursued for its own sake, it is this ethic of engaged scholarship that makes possible the discovery of knowledge for the elevation of the human condition. It is this ethic that can bestow light in the midst of social darkness and thereby help restore that most fundamental of human values to its rightful eminence—human dignity—and, not just for some, but for all.

Moving forward, we can only embrace Ibram Kendi’s concluding words in his award winning Stamped from the Beginning: “There will come a time when we will love humanity, when we will gain the courage to fight for an equitable society for our beloved humanity, knowing, intelligently, that when we fight for humanity, we are fighting for ourselves. There will come a time. Maybe, just maybe, that time is now.”

A guiding principle of this magazine is the dissemination of significant research, in concert with the symbolism of the emanating light in the University of California emblem. It is to disseminate in a manner that is accessible and readily available to the lay public. But, more importantly, it is to do this in order to foster and cultivate a new kind of responsible scholarship that engages not just scholars but the public, the press, and policy makers.

This issue’s cover story, “State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California” highlights new research from the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools. It delves into the unparalleled crisis of student homelessness in our state and offers insightful recommendations for tackling this problem. This research is eminently reflective of the ethic of engaged scholarship discussed above.

This issue also includes work of one of our newest UCLA Education faculty members, Eddie R. Cole, whose new book The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom provides a perceptive history of university presidents during the civil rights era and how they shaped the struggle for racial equality. It has been generating praise among the academic and popular press while furthering the conversations towards change and more enlightened university leadership.

Be sure to read the excerpt from the new book by UCLA Information Studies Professor Ramesh Srinivasan. In Beyond the Valley: How Innovators around the World are Overcoming Inequality and Creating the Technologies of Tomorrow, Srinivasan studies the relationship between technology, politics, culture, and societies across the world and examines and confronts the pervasive power and reach of massive technology companies.

The education story of the year has been the COVID-19 pandemic and its dramatic impact on public schools. John Rogers, Professor of Education and director of the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education and Access, has already studied its early impact with a new national survey, “Learning Lessons: U.S. Public High Schools and the COVID19 Pandemic in Spring 2020.” This research study reveals schools making significant strides meeting the needs of students confronted by illness, economic insecurity and homelessness, stress and anxiety and even death, but challenged by the pervasive inequities that have for too long undermined schools and communities.

Also included is an excerpt of a paper by Kathy Carbone of the UCLA Department of Information Studies, “A Collection and its Many Relations and Contexts: Constructing an Object Biography of the Police Historical/Archival Investigative Files.” Dr. Carbone’s research explores the personal and public relationships that developed between people and archival collections

and makes the case that the biography of objects is useful for the study of the relationships that records create.

And finally, we highlight a report by Daniel Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project, “Lost Opportunities: How Disparate School Discipline Continues to Drive Differences in the Opportunity to Learn.” This work provides an in-depth examination of the previously reported 11 million instructional days lost to out-ofschool suspensions in 2016–17. I encourage you to read the report, which brings to light deeply disturbing disparities and demonstrates how the frequent use of suspension contributes to stark inequities in the opportunity to learn.

The last few months have brought to the surface endemic social issues all of which have only been magnified by the pandemic. But what it reinforces is the commitment to responsible and engaged scholarship—one that steadfastly and resolutely keeps the human good at the forefront. And I believe our intellectual resources in education and information do just that and thereby meaningfully contribute to shaping the national conversation on issues of preeminent importance.

Thank you for reading this issue of our award winning magazine. As we close 2020, we look forward to sharing with you our learnings, our insights and our perspectives over the next decade in the interest of an enlightened and engaged citizenry.

“Let There Be Light.”

—Tina

Photo: Jennifer Young UCLA Ed&IS FALL 2020 3

This includes over 4 million students in the Golden State who are economically disadvantaged, over 269,000 young people in K–12 systems experiencing homelessness, 1 in 5 community college students, 1 in 10 California State University (CSU) students, and 1 in 20 University of California (UC) students.

“California could fill Dodger stadium with students experiencing homelessness almost five times and still probably need to use the parking lot for overflow,” says Joseph Bishop, the director of the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools and the lead author of State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California.

Analyzing data from the California Department of Education, the report shows that nearly 270,000 K–12 students in California experienced homelessness in 2018–19. And the number has increased by nearly 50 percent in the past decade. Large numbers of college students have also struggled with housing insecurity with 1 in 5 California Community College students, 1 in 10 California State University students, and 1 in 20 UC students experiencing homelessness.

“We are talking about young people who may be sleeping on the streets, in cars or in shelters,” Bishop adds. “This is a crisis that deserves immediate action.”

Developed over the past year, and including interviews with more than 150 educators, homeless liaisons and students, the new report provides a comprehensive analysis of homelessness among students in California, detailing the challenges facing thousands of students and the education agencies and community organizations that serve them.

California’s population of students experiencing homelessness is disproportionately Latinx and Black. Latinx students account for 7 in 10 of homeless students, and while Black students make up just 5 percent of the student population, they represent 9 percent of students experiencing homelessness.

“Homelessness impacts Latinx and Black students the most, with real and negative consequences,” said Lorena Camargo Gonzalez, one of the lead authors of the study. “The

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated many of the preexisting inequities present for students and families profoundly impacted by poverty and inequality in California.

BY JOHN MCDONALD

We are talking about young people who may be sleeping on the streets, in cars or in shelters. This is a crisis that deserves immediate action.

prevalence of Latinx and Black youth experiencing homelessness requires more racially and culturally responsive strategies in education practice and policy.”

The report examines the implications for student learning and success. The findings raise serious concerns. Students experiencing homelessness are twice as likely to be suspended (6% versus non-homeless rate of 3%) or chronically absent (25% versus non-homeless rate of 12%), have a lower high school graduation rate (70% versus non-homeless rate of 86%), and half as likely to be UC-CSU-ready (29% versus 52%) than their non-homeless peers.

The capacity of schools and agencies to deal with students experiencing homelessness and the need for a dedicated funding stream to address the issues is an ongoing and critical challenge. The federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (MVA) which is intended to support the educational success of students experiencing homelessness, provides just over $10 million to California’s schools, a sum that is grossly inadequate. Just 106 of 1,037 school districts (9%) in California

received federal funding from MVA to meet the mandates of the law.

“The 106 MVA subgrants touch about 97,000 young people or about one in three students experiencing homelessness in the state,” Bishop said. “That means a majority of students and local education agencies receive no dedicated federal funds to support the educational success of students experiencing homelessness.”

And while some California school districts are prioritizing the needs of students experiencing homelessness through the Local Control Funding Formula planning process, or through the state’s Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS), the report underscores that the state has no dedicated funding stream to support students experiencing homelessness.

There is also a need for better coordination between education and community agencies and nonprofits, and need for a stronger focus on early education for homeless students. The researchers interviewed 13 students experiencing homelessness. They said they often feel overlooked or misunderstood,

Nearly 270,000 K–12 students in California experienced homelessness in 2018–19.

And the number has increased by nearly 50 percent in the past decade.

and need support to fully engage in learning.

“We need to make it more easily accessible to acquire services that benefit them in their life and maybe make it also easier for them to see that there’s resources,” one student told the researchers. “From my perspective, there’s no real access to resources that you can really call upon and say, ‘Hey, I need some help’.”

“Even in these tense and difficult times, the large and growing number of students experiencing homelessness in our state is a crisis that should shock all of us,” said Tyrone Howard, faculty director of the Center for the Transformation of Schools and the UCLA Pritzker Family Chair in Education to Strengthen Families. “We hope this report will create greater awareness of student homelessness, the racial disparities that exist with students experiencing homelessness, and provide

policymakers with meaningful insight and information. Aggressive, immediate and effective action is needed by leaders at every level of government and in our community to dismantle this unacceptable crisis.”

The report and recommendations for State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California can be found at: http://www.transformschools. ucla.edu/stateofcrisis

The prevalence of Latinx and Black youth experiencing homelessness requires more racially and culturally responsive strategies in education practice and policy.

State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California, provides a comprehensive analysis of the student homelessness crisis in California. In addition to a review and analysis of current data, the report identifies key findings based on interviews with more than 150 students, educators, community leaders and others in the field.

Current professional capacity to support students experiencing homelessness is inadequate: comprehensive, targeted and coordinated training is needed. Additional training on common strategies that incorporate student supports such as trauma-informed care, restorative practices, and efforts that promote positive social and emotional development are essential for schools serving students experiencing homelessness. This is especially true for educators working directly with LGBTQ students who experience high rates of homelessness and housing insecurity often due to family rejection on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Homeless liaisons are struggling to effectively respond to growing needs in their community, requiring more resources and staffing. Student homelessness has increased by 48 percent over the last decade. The federal McKinney-Vento Act (MVA) mandates that all school districts designate a homeless liaison who can serve as an advocate for students experiencing homelessness. Homeless liaisons are among the few staff who shoulder the major responsibilities for the academic success and well-being of young people experiencing homelessness, including the initial identification of students experiencing homelessness and managing whole support efforts to ensure student academic success.

The prevalence of Latinx and Black students experiencing homelessness requires more racially and culturally responsive strategies in education practice and policy. Analysis of statewide statistics shows that Latinx (70%) and Black (9%) students who are experiencing homelessness are almost twice as likely to be suspended or miss an extended period of school to absenteeism, experience lower graduation rates, and to be less ready for college than their non-homeless peers. Addressing these patterns will require educators and policymakers to challenge the customary discourses related to homelessness, and the role race plays in determining the educational success of students.

Students experiencing homelessness are often overlooked or misunderstood in school settings, which can result in negative educational experiences. A lack of understanding of student experiences can reinforce educator stereotypes about homelessness and heighten student feelings of isolation. Prioritizing consistent and caring school environments can help foster quality relationships between teachers and students, and help educators to identify and address underlying issues that can make students particularly vulnerable in school.

Better coordination is needed between child welfare, housing and education stakeholders to alleviate barriers for students and families. To improve outcomes for students experiencing homelessness, a greater focus must be placed on the coordination of efforts to address homelessness between schools, community-based organizations, housing, and county and state agencies. Doing so would make it possible to create an integrated, family-centered response aimed at disrupting cyclical patterns of homelessness. Greater coordination also acknowledges that no one public system (i.e. schools) can adequately respond to all the needs of young people and families.

Community-based organizations and nonprofits provide a critical function as part of an ecosystem of support for students and can get out resources to families quickly. Nonprofit organizations provide services to students and families experiencing homelessness outside of the regular school day hours and on weekends. Fragmented coordination between schools, districts, homeless liaisons, and nonprofits or community-based organizations can create unnecessary obstacles for young people and families seeking support. There are emerging examples of school systems, community-based organizations, faith-based groups, counties, and governments who have been able to align services in communities for the benefit of students and families experiencing homelessness.

The bookends of education, early education and higher education, are an essential part of a coordinated response to student homelessness, from cradle to college. The nature of the challenges facing students experiencing homelessness varies considerably depending on their age and the type of educational institution in which they are enrolled. Distinct responses, coupled with more seamless educational pathways, can help students experiencing homelessness encounter minimal disruption to their educational pursuits. Early interventions and continuous investments in quality school experiences can change mobility patterns across generations and break cycles of poverty. The California Community College (CCC), California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) systems are responding proactively through efforts like the California Higher Education Basic Needs Alliance (CHEBNA) to ensure that growing populations of students experiencing food insecurity, homelessness or other related challenges are able to make academic progress and ultimately graduate.

EXCERPTS FROM

BY EDDIE R. COLE

BY EDDIE R. COLE

“You people seem to have been born into a time of crisis,” Edwin D. Harrison told the students gathered inside the old gymnasium at the Georgia Institute of Technology the morning of January 17, 1961. Wearing a dark suit and tie squarely positioned over a white shirt, the forty-five-year-old college president stood behind a skinny lectern, flanked by a microphone to his right. Students squeezed into the crowded bleachers. Others sat on tables, leaving their legs swinging beneath, while the rest sat on the gym floor. The students leaned forward with uneasy frowns or held their heads with worried, aimless gazes.

Harrison hosted an informal meeting every quarter to provide an opportunity for students to chat with him about any topic. But this assembly was different. Roughly two thousand students attended, a record number for an open forum. Therefore, when Harrison stepped before the crowd of somber young white faces, he took the first steps to address what would become “Georgia Tech’s toughest test”—desegregation.

The uneasiness that hovered over the gymnasium came with the swirling suspicion that Georgia Tech, a state-supported university, would succumb to the same racial violence that had occurred a week earlier only seventy miles east of its Atlanta campus. In Athens, a white mob overran the University of Georgia after a federal court order allowed two Black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, to enroll. Several white students and Ku Klux Klan members rioted in tandem. They set fire to Hunter’s residence hall, launched makeshift missiles, and tossed bricks and rocks at local police officers and journalists. Afterward, allegations spread that Georgia’s segregationist governor, Ernest Vandiver, intentionally delayed dispatching state law enforcement to help control the mob violence.

The events in Athens prompted Georgia Tech students to rattle off a barrage of inquiries as soon as Harrison opened the floor for questions. One student asked, “How has the racial crisis affected Tech’s ability to attract and retain a competent faculty?” Another asked, “What can we do to show our displeasure at being forced into an integrated situation?” And another question: “In some northern universities, some of the student organizations have been forced to integrate or get off campus. Do you think that is apt to happen here?”

Then more questions came in rapid fire: What would happen to students who protested the enrollment of Black students? What was the university’s policy to stop outsiders like Klansmen from causing trouble on campus? What challenges did Harrison anticipate Black students would bring to Georgia Tech besides potential violence? Since the press had worsened the Athens situation, according to one student’s assessment, could journalists be banned from Georgia Tech? One after another, student questions revolved around desegregation: how, if, and when. But Harrison’s answers demonstrated that desegregation was a far more complex issue for college presidents than the students could imagine.

With each response, Harrison introduced a new issue he was dealing with regarding civil rights. He explained that Georgia Tech was the only technological institute in the South with a respected national academic reputation. In fact, nonGeorgians widely believed it was a private university because of the stigma carried by state-supported southern white colleges of being social clubs rather than intellectual hubs. The exceptional academic performance of Georgia Tech students also led nonsouthern companies to hire its graduates. Yet, he said, mob violence would certainly damage this reputation.

In answering another student question, Harrison pondered local residents’ varying opinions on desegregation and whether the rapport between campus and the community would worsen depending on how the university managed desegregation. Additionally, when considering the consequences of violence, Harrison explained how outside journalists—those in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago— regularly critiqued white southerners’ resistance to desegregation. He then gingerly

weighed the idea of banning journalists from campus alongside concerns about freedom of the press. This answer dovetailed with his bolder threat to expel any student demonstrators.

Those issues aside, another student question prompted Harrison to note the Ford Foundation’s recent $690,000 grant to Georgia Tech to support doctoral programs; however, those funds could be jeopardized if the institution mishandled desegregation. Media influence, community relations, freedom of expression, academic freedom, and private donors were just some of the sources of pressure that emerged alongside concerns about student resistance. “Any actions and activities which you could undertake if and when a crisis should arise on our campus,” Harrison advised students, “will affect greatly the future of the institution.”

As news of Harrison’s remarks to Georgia Tech students spread throughout the region, James E. Walter, president of Piedmont College, a segregated white college in Demorest, Georgia, immediately wrote Harrison. “Power to you as you carry the ball for many of us,” Walter remarked. A similar message came from Florida, where Franklyn A. Johnson, president of the segregated Jacksonville University, concluded, “I have no doubt that we here will grapple with this sort of a situation sooner or later.”

From the largest to the smallest institutions, private or state-supported, the academic leaders of segregated white campuses knew the first presidents tasked with addressing desegregation were simply that: the first. They were attentive to the long-anticipated race question at white institutions, but no amount of anticipation would prepare them for the actual pressures of the day. Thus, as Joe W. Guthridge, Harrison’s assistant and Georgia Tech’s director of development, warned Harrison the day following the quarterly student meeting, “we should not be led into a sense of false security based on the positive reaction we received.”

The Campus Color Line is a history of the Black Freedom Movement as seen through the actions of college presidents. The most pressing civil rights issues—desegregation, equal educational and employment opportunity, fair housing, free speech, economic disparities—were intertwined with higher education. Therefore, the college presidency is a prism through which to disclose how colleges and universities have challenged or preserved the many enduring forms of anti-Black racism in the United States. Through this book, the historic role of college presidents is recovered and reconstructed. It expands understanding regarding college presidents and racial struggles, and it breaks down our regional conceptions while broadening our perspective on how these academic leaders navigated competing demands.

Historical accounts of the Black Freedom Movement have suggested that the nation’s college presidents—as a national collective—were neither protagonists nor antagonists in the debate over racial equality. Institutional histories and individual presidents’ biographies demonstrate that there are some exceptions, but overall, college presidents as a group are not portrayed as directly responsible for racial segregation, nor were they expected to lead the challenge against segregation. In essence, college presidents walked a fine line between constituents on opposite sides to protect themselves

and their institutions from reprisal. This captivating narrative demonstrates the precarious position of these academic leaders; however, it is incomplete. There is more to learn about the broader struggle for Black freedom through college presidents.

The Black Freedom Movement presented numerous new challenges for college presidents. Student and faculty demonstrations were perhaps the most visible, but they were not the only cause for concern. How a college president managed racial tensions also affected the recruitment and retention of faculty. The support of local entities—businesses, churches, and civic organizations—also hinged on where academic leaders stood on racial advancement. Journalists from local and national media outlets frequented campuses to assess how college presidents were handling racial crises; in turn, college presidents became increasingly focused on maintaining good publicity.

Trustees and alumni donors stirred new questions about higher education governance, and college presidents were forced to mold new university practices around free speech and academic freedom. College presidents also exchanged pleasantries with the executives at private foundations to stay on the good side of philanthropists. Meanwhile, those same philanthropists’ dollars helped fund the physical growth of universities and, subsequently, strained relationships between academic leaders and local residents.

These issues and others demonstrate why President Harrison’s open forum with Georgia Tech students is significant. It was a rare moment when a college president publicly discussed the breadth of challenges associated with desegregation and broader civil rights struggles. College presidents usually held such conversations behind closed doors, through private correspondence, or within mediums limited to academic circles. But Harrison stood before the Georgia Tech student

body and candidly laid bare some of the issues college presidents quietly managed. During struggles for racial equality, college presidents played varied roles, from mitigating free speech concerns to soliciting private foundations to fund racial initiatives, occasionally reaching beyond their campuses to shape urban renewal programs.

University leaders continue to play these roles today, as racism, racial tensions, and racial violence resonate loudly on college campuses once more. Education researchers have found that current college presidents sometimes alienate members of their campus communities when they respond to racial unrest—suggesting that campus officials do not always understand or utilize history well. Legal scholars have assessed that college presidents’ mishandling of contemporary racial unrest have resulted in “millions of tuition dollars lost, statewide and national reputation[s] harmed, [and] relations with [legislatures] damaged.” Journalists have also deemed recent campus unrest “a second civil rights movement” and “a rebirth of the civil rights movement.” But these contemporary assessments are shaped by a long history of racism, and college presidents’ responses to it, on college campuses.

In the mid-twentieth century, higher education inherited a broader meaning as a cultural structure and distinctive aspect of a democratic society, and each chapter conveys a multifaceted tale of the college presidency and its new and competing pressures. The Campus Color Line illustrates the variety of challenges academic leaders confronted and the range of strategies they employed as they ushered the full range of institutions into new social and political significance and influenced how municipal, state, and federal officials engaged racial policy and practices. There are lessons to be learned from how these individuals negotiated organizational needs and pressures that conflicted with academic missions and espoused institutional values. This national study of the college presidency—from smaller colleges to elite universities—conveys historical accounts that must be reckoned with if we are to ever envision college presidents better equipped to effectively address racism, racial tensions, and racial violence in US higher education.

The Black Freedom Movement presented numerous new challenges for college presidents. Student and faculty demonstrations were perhaps the most visible, but they were not the only cause for concern. How a college president managed racial tensions also affected the recruitment and retention of faculty. The support of local entities—businesses, churches, and civic organizations—also hinged on where academic leaders stood on racial advancement … college presidents became increasingly focused on maintaining good publicity.

UCLA Ed&IS: What inspired you to write this book?

COLE: Recent racial incidents over the years—Missouri and Oklahoma in 2015, Virginia in 2017, and North Carolina in 2019 —had a standard public reaction of shock, and university administrators had a standard condemnation of said racial incidents. Yet, we know that the past shapes society today. So, in the same way that we know about the decades of history of student activism, I also wanted to know more beyond academic leaders’ past responses but also how they have engaged racial policies and practices both in education and beyond.

UCLA Ed&IS: What is the most important thing(s) you hope the book will help people to be aware of and understand?

COLE: It is most critical to understand the role that institutions of higher education—particularly college presidents—have played in molding policies and practices with racial implications. Academic leaders have not only had to respond to moments of racial unrest, but history demonstrates they have also proactively shaped how higher education has addressed questions around race. Therefore, this book expands our understanding of how administrative structures have influenced how campuses and the broader society advance racial equity.

UCLA Ed&IS: What do you hope the book helps to accomplish?

COLE: I hope the book immediately reorients how we think about, or don’t think about, how presidents and chancellors can steer conversations and subsequent actions around racism. Because our issues today are not new, and history reminds us that academic leaders are also not new to having to address said issues. Therefore, we’d be wise to learn from the past and—so far—I’m pleased to hear from many readers that my hope for the book is coming into fruition.

This book is a history ripe for the present. It takes a national view of the Black Freedom Movement as seen through the actions of college presidents, and what a world we’re in right now. Today, as in the past, we’re having a national conversation around race and racism, and I believe anyone who is even remotely interested in making sense of our current “reckoning” around race will find the book deeply insightful.

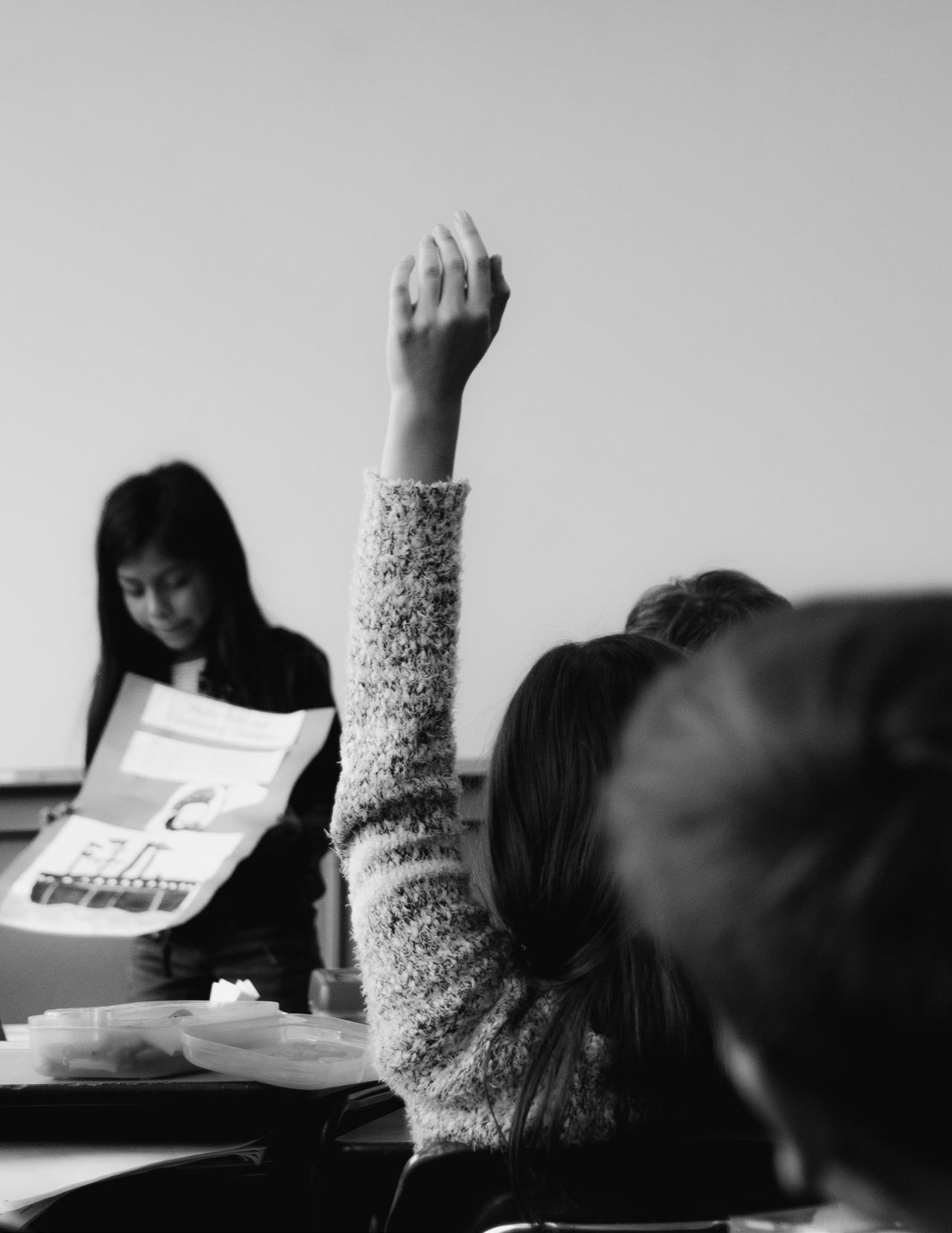

A UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access national survey of high school principals looking at the response of educators to COVID-19 pressures.

BY JOHN MCDONALDIn early March of 2020, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted the closure of public schools across the United States. As the virus surged, with little warning and little opportunity for planning, principals and teachers and school staff acted with urgency to close campuses and classrooms and moved quickly from in-person to remote learning for students. In the midst of this almost unprecedented challenge, educators across the nation stepped up to find ways to offer students instruction, as well as to provide meals, counseling, extracurricular activities, and other critical services.

In a first look at how COVID-19 impacted American high schools last spring, the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access has conducted a national survey of high school principals looking at the response of educators in those difficult days. Their work finds schools stepping up strongly to respond to the needs of students confronted by illness, economic insecurity and even death, but challenged by the pervasive inequities that have for too long undermined schools and communities.

“The results of our survey make two things very clear,” said John Rogers, education professor and director of the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. “Public schools have responded heroically, playing a critical role in supporting students and sustaining communities threatened by the deadly virus and economic shutdown. But the inequities that have long plagued our schools have been exacerbated by the pandemic, impeding learning for those students in communities already greatly challenged by economic and social inequalities.”

The survey, Learning Lessons: U.S. Public High Schools and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spring 2020, reports the responses of a nationally representative sample of 344 high school principals questioned in May and June 2020 after schools closed campuses and transitioned to distance learning amid the pandemic.

Throughout Spring 2020, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Louisiana felt the full brunt of the pandemic. One Massachusetts principal described the “intensity of the problems we’ve faced ... Death. Loss of jobs. Anxiety. Depression.” Nancy Anderson, a principal in suburban New Jersey, noted that her students had “suffered losses … neighbors dying … people afflicted.” While rates of infection in spring were dramatically lower in some other states, the effects of the economic dislocation created by the national lockdown were experienced widely. James Wilson, the principal of a socioeconomically diverse school in urban Washington, remembered “seeing families thrust into poverty so quickly and waiting in food lines.” Sofia De Leon, the principal of a high-poverty school in California, recounted: “As the weeks go on, I know

59%

that my students’ lives and well-being have become more and more precarious. There are some social safety nets, but not nearly enough and the disparity is palpable.”

Educators stepped up to meet the needs of students and their families. In the survey, 59 percent of principals who responded said they had helped students and families access and navigate health services. More than 9 in 10 (92%) provided meals. Eighty percent provided access to mental health counseling. Fifty percent said they provided support to students experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness. Almost a third of principals provided financial support to students and their families. Most poignantly, 43 percent of principals reported providing support for students who experienced death in their families.

“These findings underscore the critical role schools play in their communities,” Rogers said. “More than twothirds of principals said their school or district provided meals to family members of students who were not enrolled in the school. And while principals of almost all schools provided meals to students, nearly half of principals of high-poverty schools provided meals to more students.”

HELPED STUDENTS AND FAMILIES ACCESS AND NAVIGATE HEALTH SERVICES.

92%

PROVIDED MEALS.

80%

PROVIDED ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH COUNSELING.

43%

OF PRINCIPALS OF PRINCIPALS OF PRINCIPALS OF PRINCIPALS

REPORTED PROVIDING SUPPORT FOR STUDENTS WHO EXPERIENCED DEATH IN THEIR FAMILIES.

Public schools have responded heroically, playing a critical role in supporting students and sustaining communities threatened by the deadly virus and economic shutdown. But the inequities that have long plagued our schools have been exacerbated by the pandemic, impeding learning for those students in communities already greatly challenged by economic and social inequalities.

REPORTED THAT ALL THEIR TEACHERS HAD THE NECESSARY TECHNOLOGY WHEN THEIR SCHOOL TRANSITIONED.

17%

OF PRINCIPALS

INDICATED THAT ALL OF THEIR STAFF—TEACHERS, COUNSELORS, PSYCHOLOGISTS, SOCIAL WORKERS, AND CLERICAL SUPPORT—WERE READY.

SCHOOLS WITH HIGH LEVELS OF POVERTY WERE MORE THAN

32% 8x

AS LIKELY TO EXPERIENCE A SEVERE SHORTAGE OF TECHNOLOGY AT THE TIME OF TRANSITION—AT LEAST HALF OF THEIR STUDENTS LACKED THE NECESSARY TECHNOLOGY.

One in five schools moved to remote instruction the very next day after closing for in-person instruction. But the move to remote learning was not the same for all schools and students. Inequality in learning opportunities was exacerbated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The digital divide was a prime cause.

Many educators and key staff struggled to move online in the early days of the transition. Online communication was a challenge, with many principals reporting they had never used Zoom or other technologies for video conferencing or online communications with faculty or staff or with students and parents before the pandemic. Staff members also lacked the necessary hardware or connectivity to support remote instruction. Only one-third (32%) of principals reported that all their teachers had the necessary technology when their school transitioned. Only 17 percent of principals indicated that all of their staff— teachers, counselors, psychologists, social workers, and clerical support— were ready. These gaps in readiness were most commonly found in schools with high rates of poverty and in schools in rural areas. Schools with low rates of poverty were more than three times as likely (25% to 8%) as schools with high rates of poverty to have all staff supplied with necessary technology when they transitioned to remote instruction.

In schools that entered the pandemic with a strong technological infrastructure, educators and students were able to draw upon previous experience to support remote instruction. For principals like George Taylor in Texas and Martina Hernandez in Arizona, members of their school community were familiar with platforms like “Google Classroom” and “Schoology.” Ian Brown, a principal in suburban Indiana, reported that his school was “ahead of the curve with preparation for a situation like COVID,” because it had dedicated almost all of its professional development time for six years to train teachers in digital learning.

High-poverty schools and rural schools struggled during the transition. Carol Stevens, a principal at a school in rural Louisiana where many families lack internet or cell phone coverage,

said that as the school transitioned to remote instruction her staff was “totally unprepared” to provide “distance learning for all students.” Her teachers “had to learn ‘on the fly’.”

Principals also reported great variability in student access to the technology hardware and connectivity needed to participate in learning from home. Schools with high levels of poverty were more than 8 times (34% to 4%) as likely to experience a severe shortage of technology at the time of transition—at least half of their students lacked the necessary technology. Schools with high levels of poverty worked to provide technology to the most students, and principals in these schools spent more time distributing and troubleshooting technology than principals in other schools.

After several weeks into the transition to remote instruction, a strong majority of principals reported that almost all (95% or more) of their students had access to the necessary technology. Yet even after these efforts, just one quarter (26%) of principals could say that all of their students had the necessary technology for remote learning— and this figure was much lower in highpoverty schools.

One of the key questions considered was whether a growing number of students fell behind during remote learning, and was this more likely to occur in particular school communities. The answer is it did. The survey makes clear that the impact of remote instruction has significant implications for educational equity. Many high schools had difficulty providing necessary supplementary services for English Learners and Special Education students. More than 40 percent of all principals reported that their school did not supply English Learners with instructional materials—either online or in print packets—in their home language. And a majority of principals reported that their school did not provide the same quality of services for students with disabilities (such as occupational therapy or counseling) as prior to the pandemic.

Even in those schools that provided students with materials in their home

These gaps in readiness were most commonly found in schools with high rates of poverty and in schools in rural areas.

language, English Learners often did not benefit from the informal peer-to-peer conversations that characterize the best classrooms. Suzanne Davis, a principal in California, said that her school found “irrefutable patterns that distance learning doesn’t work for our language learners.” While almost all principals reported that teachers at their schools are working with Special Education students toward their IEP goals, some acknowledged that their teachers were not tracking students’ progress toward these goals or making accommodations for online teaching.

Two-thirds of principals reported that fewer students than prior to the pandemic were able to keep up with their assigned work. In 43 percent of schools, more than a quarter of students were unable to keep up with assignments during remote instruction. This problem was far more likely to occur in high-poverty schools than in low-poverty schools, with two-thirds (67%) of students in schools with high poverty rates falling behind.

And while some students fell behind, others ceased participating at all during remote instruction. Nearly half of principals reported that they have had difficulty maintaining contact with at least 10 percent of their students. In some instances, principals were not able to establish any contact with a subset of their

student body. Principals in high-poverty schools were several times more likely than principals in low-poverty schools to report difficulties contacting large numbers of students.

“Our research reveals exceptional efforts by school principals across the country, but also makes clear that the inequities confronting schools amid the pandemic map directly onto the preexisting social inequalities that unfairly affect our most vulnerable students,” Rogers said. “As we have moved to remote instruction, economically disadvantaged communities have been disproportionately impacted.”

“To their great credit, schools have played a strong role in the nation’s response to the pandemic,” Rogers said. “But many principals said they do not want to return to schools as they were. They see the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to reset and reflect on values and beliefs, to shift the way students are taught or even dismantle broken systems in a broader reinvention of teaching and learning.

“Creating those public schools will require a well-functioning civil society. Only by nurturing a shared public commitment to the well-being and development of all young people, will we ensure that public schools can fulfill their important role.”

In 43 percent of schools, more than a quarter of students were unable to keep up with assignments during remote instruction. This problem was far more likely to occur in high-poverty schools than in low-poverty schools, with two-thirds (67%) of students in schools with high poverty rates falling behind.

Learning Lessons: U.S. Public High Schools and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spring 2020 is a project of the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. The full report of the survey findings is available online at https://idea.gseis.ucla.edu/publications/ learning-lessons-us-public-high-schoolsand-the-covid-19-pandemic/

*All names of school principals are pseudonyms.

… surveillance cameras, GPS tracking of people using smartphones, and the use of shared data to apprehend terrorists provide great value. But we may not also recognize that in the process we give up our individual rights to privacy, put the most vulnerable members of our society at risk, threaten the viability of small businesses, and contribute to greater economic inequality and political division.

Sergio, a friend of mine from Argentina, recently completed a trip around the world. I met him last year in southern Mexico, where I’ve been visiting regularly since 2016 to learn from indigenous communities who have been creating their own digital networks. My visits there were inspired by my two-decade-long fascination with the internet and digital technology’s rapid development: first as an engineer and, later, as an educator and researcher exploring how digital technologies impact the lives of diverse cultures and societies.

Sergio had not traveled extensively outside of his country before. When we met at a food vendor’s table on a street in Oaxaca, he was buzzing with the excitement of having visited five continents and holding various jobs (as a carpenter and farmer, for instance, and in the service industry, at hotels and restaurants) in just the past year. When I asked him about his range of experiences in parts of the world so different from where he grew up in working-class Buenos Aires, he made an offhand remark that stopped me in my tracks: “Regardless of where you go, people get pushed into the internet. That is what they want.”

After we parted ways, Sergio’s comment stayed with me. I was struck by the contrasting but intertwined images it contained: the first being of people thrust into some alternate universe that exists beyond our screens; the second being of people who relate to the internet as the place where we share common ground. Like many of us, Sergio had the perspective of a user, simultaneously awed yet also perplexed by the characteristic “pushiness” with which websites, mobile apps, virtual reality headsets, and myriad other digital devices have appeared and made their way into our lives.

I wrote this book as a way to explore how we, the billions of internet users, can respond to the sea change that transformed an open world of online possibility into something else altogether: a digital landscape of walled gardens and predetermined paths already programmed for us, for which we have little visibility or control. If we are going to turn over our lives to these devices and systems, shouldn’t we, at the minimum, have power over how they are designed and profited from? Shouldn’t technology be people-centered, not in use and addiction, but in creation and application?

As access to the internet and cell phones expands around the world, so too does the power and wealth of but a few technology companies located on the West Coast of the United States (Silicon Valley and California) and in China. These companies offer services that have, without question, created value for their billions of users, providing efficient and economical ways for us to find and disseminate information, telecommute to our jobs, socialize with one another, and buy and sell goods. Many of us love the cheap prices on Amazon and how quickly the products we purchase

arrive at our doorstep. Others believe that things like surveillance cameras, GPS tracking of people using smartphones, and the use of shared data to apprehend terrorists provide great value. But we may not also recognize that in the process we give up our individual rights to privacy, put the most vulnerable members of our society at risk, threaten the viability of small businesses, and contribute to greater economic inequality and political division.

In domesticating the “wild west” of the internet, the big tech companies have provided a vibrant market of beneficial tools and services for users and amassed unimaginable wealth for their executives and stockholders. But in the process they have also supplanted the open, democratic internet with a vast network of privately owned architecture—imagine digital fences, highways, roads, bridges, and walls—whose sole purpose is to control people’s movement through digital space in ways that benefit their companies’ bottom lines. Clinging to this idea of an open internet obscures the reality: The digital world is structured by static, hefty, and inflexible digital architectures. And like invisible borders, they enforce specific paths.

We are increasingly aware, of course, that the phones and websites linking us to a wider world keep track of us, even when we are not using them, and that our personal data is vulnerable to covert collection and monetization. We have also experienced the amplification and rapid spread of propaganda, misinformation, and hate speech on the internet, too often with tragic results, all of which distracts us from facts, contexts, and multiple points of view. Meanwhile, journalists, activists, scholars, and more of the public are raising concerns that Chinese, Western, and white male interests dominate the content and systems that power the internet rather than those who reflect the full diversity of us online. Finally, against the backdrop of profound economic inequality across the world, we have seen how the expansion of the gig economy has made work, wages, and benefits less secure than ever before, even as digital automation threatens to eliminate much of the current job market.

I, like so many of us, derive incredible value from the services and products provided by Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook. But I also know that I have agreed to their terms of service without understanding exactly what I have given up in exchange for what I am getting: I am not being given the means to think through the downstream implications of my actions even for myself, much less for others in my networks. As an example, Amazon has made it so inexpensive and easy to buy almost anything, that almost all of us use the site regularly. The Chinese Alibaba is no different. But is it okay that both these companies have monopolistically overtaken an open marketplace? What about Amazon’s facial recognition technology being sold to military contractors, the police, and to support President Donald Trump’s actions with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency? Are we okay with these sorts of transactions, similar examples of which we can find involving every powerful tech company?

In Beyond the Valley I show examples of technologies from around the world that balance efficiency with values of equity, democracy, and diversity. I tell stories of global innovators that point the way toward a humane and balanced internet of tomorrow.

How many of us know that the internet itself largely came to be thanks to public, taxpayer-funded research? So how come the spoils of our public investments, the trillions of dollars associated with Silicon Valley, have only lined the pockets of uber-rich investors and executives? Somehow we gave away all the money and power to the 1 percent, a secretive cadre of middlemen.

Don’t get me wrong, the value provided by the most powerful and ubiquitous technologies is unmistakable: Facebook, Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon have created efficient, helpful, and beautiful services and objects most of us wouldn’t want to live without. And these Big 5 tech companies are not the only major players. Although I don’t discuss Chinese tech giants in detail in this book because I couldn’t gain sufficient access to information via first-hand interviews, they are equally pervasive in their presence and influence, particularly in Asia. In 2018, China took 9 of the top-20 slots ranking internet leaders

of the world, with their businesses and products reflecting the kind of design and performance values championed by Silicon Valley. In the e-commerce sector, Alibaba is the No. 1 retailer in the world with profits and sales surpassing Amazon and eBay combined. It too, has worked toward expanding and synthesizing its services, from cloud computing to offering virtual reality shopping experiences for its users. On top of it all, China has just launched an Artificial Intelligence (AI) news anchor, according to state news agency Xinhua. The Guardian reported that Chinese viewers in November 2018 were greeted with a digital version of regular anchor Qiu Hao, who promised them, “Not only can I accompany you 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. I can be endlessly copied and present at different scenes to bring you the news.”

I wrote this book not to merely criticize or raise alarms, but to advocate for and illustrate a future where the connectivity and the online services we love

I tell stories of entrepreneurs creating technologies with a social mission, users pooling resources and ideas to support grassroots politicians and ethical causes, and communities coming together to own digital platforms. In all of these cases the idea is for people, not private tech companies, to design their own networks and services based on shared values and belief systems.

don’t come with the costs of surveillance, income disparity, false information, and extreme imbalances in how technologies are designed and deployed. The possibilities are vast, and we can learn a great deal from the whole range of strategies and efforts already underway. In order to put the power of technology to work for the common global good, we must identify what is dangerous about the current arrangement, and mobilize a vision for positive change.

The challenge doesn’t just face the big tech companies but any who presume that their so-called neutral systems always do good, even when their troubling effects may look more like social engineering. For example, consider the company Faception’s attempts to predict IQ, personality, and violent behaviors through the application of “deep” machine-learning techniques to facial features and bone structure. We’ve made such horrible mistakes before, for example treating black people’s faces and body types as supposed evidence of their inferiority. Are we about to justify continued racism thanks to “machine learning”?

In Beyond the Valley I show examples of technologies from around the world that balance efficiency with values of equity, democracy, and diversity. I tell stories of global innovators that point the way toward a humane and balanced

internet of tomorrow. I explain the perils that occur when a narrow understanding of efficiency becomes our primary focus and ironically creates inefficiency. Efficiency on our consumer platforms can make all of our lives inefficient by disturbing our sense of security and privacy, interfering with our democracy, and furthering economic inequality. Efficient industries can create the inefficiency (and massive threat) of climate change. And similarly, the blind embrace of efficiency can result in tragic hidden costs to vulnerable humans—like when the reliance on AI-powered safetyfeatures that could not be overridden in an emergency resulted in fatal plane crashes in 2018 and 2019.

To address these challenges I tell stories of entrepreneurs creating technologies with a social mission, users pooling resources and ideas to support grassroots politicians and ethical causes, and communities coming together to own digital platforms. In all of these cases the idea is for people, not private tech companies, to design their own networks and services based on shared values and belief systems. These small-scale, environmentally conscious, user-governed, and often decentralized efforts are examples of what some call “appropriate” or “people-centered” technology. I also share examples that are less widely established, but which

are on the cutting edge of innovation, such as privacy-protecting systems, universal basic income, portable benefits, union organizing, digital cooperatives, worker councils, and more.

These are not all new ideas; they exist around us and it’s time to see what we can gain by paying attention to them. But we can also do more, starting with demanding that governments and big tech companies be more accountable and communicative with their users. We can also work with engineers who are not trained to analyze the social, political, or economic effects of the systems they create to develop a more reflective and inclusive design process. We have a range of positive directions in front of us, and they can drive the change needed for a connected world that is more just, more representative, and more diversely democratic.

Part of pursuing this future is pursuing the internet we were promised, but haven’t yet received: an internet that acts as a “global village,” bringing us all together; an internet that creates, or at least supports, equality; an internet that lifts all boats. The coming pages will look at the past and the future, around the world, and at our cultural, political, and economic lives to point toward a digital future that supports diversity, democracy, and the belief that our collective and individual welfares are interwoven.

Part of pursuing this future is pursuing the internet we were promised, but haven’t yet received: an internet that acts as a ‘global village,’ bringing us all together; an internet that creates, or at least supports, equality; an internet that lifts all boats.

Summary of a Research Project from the Center for Civil Rights Remedies, an initiative of the UCLA Civil Rights Project/ Proyecto Derechos Civiles, led by Dan Losen and Paul Martinez

BY JOHN MCDONALD

BY JOHN MCDONALD

During the 2015–16 school year, according to national estimates released by the U.S. Department of Education in May 2020, there were 11,392,474 days of instruction lost due to out-of-school suspension. That is the equivalent of 62,596 years of instruction lost. The counts of days of lost instruction were collected and reported for nearly every school and district by the U.S. Department of Education. For the very first time, one can see the impact of out-of-school suspensions on days of lost instruction for every student group in every district in the nation. Considering the hardships all students are experiencing during the pandemic, including some degree of suspended education, this shared experience of having no access to the classroom should raise awareness of how missing school diminishes the opportunity to learn. The stark disparities in lost instruction due to suspension described in this report also raise the question of how we can close the achievement gap if we do not close the discipline gap.

The racially disparate harm done by the loss of valuable in-person instruction time when schools closed in March 2020 is even deeper for those students who also lost access to mental health services and other important student support services. Suspended students experience the same losses, plus the stigma of punishment, when removed from school for breaking a rule, no matter how minor their misconduct.

Lost Opportunities, produced in collaboration with the Learning Policy Institute (LPI), is the first report to capture the full impact of out-of-school suspensions on instructional time for middle and high school students, and

... how we can close the achievement gap if we do not close the discipline gap?

High school students begin an 80-mile march to the state capitol in Lansing to protest “zero tolerance” school policies that result in suspension or expulsion of students for relatively minor offences. They cite suspensions for offenses such as not bringing their ID card to school or being out of uniform. They say such punishments are disproportionately directed against minority youth. Credit: Jim West/Alamy Live News

for those groups that are most frequently suspended. The research includes details for every state and district, uncovering high rates and wide disparities, and detailing the full impact on every racial group and on students with disabilities..\

“The focus on the experiences of middle and high school students reveals profound disparities in terms of lost instructional time due to suspensions— stark losses that most policymakers and many educators were unaware of,” said Dan Losen, who is director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies and the lead researcher on the report.

In secondary schools, the researchers found the rate of lost instruction is more than five times higher than elementary school rates—37 days lost per 100 middle and high school students compared to just 7 days per 100 elementary school students. The rates for Black and other students of color are starkly higher than those of white students. Black students lost 103 days per 100 students enrolled, 82 more days than the 21 days their white peers lost due to out-of-school suspensions. Alarming disparities are also observed when looking at race with gender. Black boys lost 132 days per 100 students enrolled. Black girls had the second highest rate, at 77 days per 100 students enrolled.

While suspension rates for secondary students have declined somewhat

nationally, rates at the elementary level did not improve. The research also finds that state-level racial disparities are often larger than the national disparities suggest—showing multiple states with exceedingly high rates of loss of instruction for students of color when compared to their white peers. For example, a comparison of rates of lost instruction shows that Black students in Missouri lost 162 more days of instructional time than white students. In New Hampshire, Latinx students lost 75 more days than white students. And in North Carolina, Native American students lost 102 more days than white students.

At a school district level, the disaggregated district data show shockingly high rates of lost instruction, with some large districts having had rates of more than a year’s worth of school—over 182 days per 100 students. For example, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the rate of lost instruction was 416 days per 100 students. The disaggregated district data reveals some rates and disparities that are far higher and wider than most would imagine based on the state and national averages, especially for Black students and students with disabilities. The analysis is also the first to document that students attending alternative schools experience extraordinarily high and profoundly disparate rates of lost instruction.

The rates for Black and other students of color are starkly higher than those of white students. Black students lost 103 days per 100 students enrolled, 82 more days than the 21 days their white peers lost due to out-of-school suspensions. Alarming disparities are also observed when looking at race with gender. Black boys lost 132 days per 100 students enrolled. Black girls had the second highest rate, at 77 days per 100 students enrolled.

“These stark disparities in lost instruction make clear we cannot close the achievement gap if we do not close the discipline gap,” Losen said.

The research also includes new information about school policing, lost instruction, referrals to law enforcement, and school-based arrests, revealing that in some districts more than one out of every 20 enrolled Black middle and high school students were arrested.

And at a time of increasing national concerns about racism and abusive policing and a legal requirement that every district report their school policing data every year, the report documents widespread failure by districts to report data on school policing despite the requirements of federal law. Specifically, over 60 percent of the largest school districts (including New York City and Los Angeles) reported zero schoolbased arrests.

“Our research suggests that much of the school-policing data from 2015–16 required by the federal Office for Civil Rights were either incomplete, or never collected,” said Paul Martinez, the report’s co-author. “The findings raise concerns about how students of color cannot be protected against systemic racism in school policing if districts and police departments don’t meet their obligation to collect and publicly report these data annually.”

The research also indicates widespread noncompliance with the reporting requirements of Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA) which explicitly requires states to report collected school-policing data in annual state and district report cards. As of July 2020, not one state had fully met ESSA’s state and district report card obligation regarding their most recent school-policing data.

Amid a pandemic that has resulted in a massive loss of instructional time and escalating need for mental health and special education supports and services, the researchers are urging educators to reduce suspensions and the resulting loss of instruction.

“With all the instructional loss students have had due to COVID-19, educators should have to provide very sound justification for each additional day they prohibit access to instruction,” Losen said.

The full report, found online, outlines detailed recommendations at the Federal, state and local levels on law and policy including the elimination of unnecessary removals, switching to more effective policies and practices that serve an educational purpose, and reviewing and responding to discipline disparities to promote more equitable outcomes.

not close the discipline gap.

Authors: Daniel J. Losen, J.D., M.Ed., is director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies, an initiative of the UCLA Civil Rights Project/ Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

Paul Martinez is a research associate at the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project. Martinez’s role focuses on understanding and providing solutions to disparities in school discipline, achievement, and graduation rates at the district, state, and national levels.

The full report, including an executive summary and specific recommendations, is available online: https://bit.ly/3me3L2S

These stark disparities in lost instruction make clear we cannot close the achievement gap if we do

BY KATHY CARBONE

BY KATHY CARBONE

A record is a trace of living behavior left behind that someone deems important to save in a manner that stabilizes its structure and content so that the record remains reliable, authentic, and accessible over time and across space, “whether that be for a nanosecond or millennia” (McKemmish, 2001, p. 336). Records bear witness to, serve as evidence and memory of, and reflect in some fashion the original activity and contexts that gave rise to them. And although archival processes and systems preserve or “fix” the structure and content of records, by being put to new uses in new contexts and subject to different interpretations, records are continually shifting—they are always “in a process of becoming” writes McKemmish (2001, p. 335), a notion Brothman echoes, stating that over time, a “record is an object that occurs as something that is the same as and different from itself” (2006, p. 260, italics in original).

Archivists have long been interested in the activations and itineraries of records in order to understand the contexts—social, cultural, political, technological, institutional, and ideological—in which people create, interact with, and find and make meaning with records. Ketelaar urges archivists to reconstruct the paths records take from their origins to the archive, recovering and recording the voices of “the authors of documents, the bureaucrats, the archivists, and the researchers who all used and managed the files” to discover the manifold meanings that become connected to records through their use and reuse (2001, p. 141).

Object biography, from the field of anthropology, is one method for uncovering the activations of records as well as how people experience, interact with, and ascribe meaning to records, and for contemplating the physical, mental, and social aspects of records and their effects on human endeavors and lives across contexts and temporalities. Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff introduced object biography in 1986, which centers on the idea that an object cannot be fully understood if regarded from only one point or stage in its existence and offers a way to study the production, use, exchange, and disposal of an object as well as the connections that occur between people and an object over its lifespan. Moreover, object biography explicitly focuses on unearthing what kinds of relations, understandings, and significances evolve between people and objects through social interactions in shared contexts.

This paper is an object biography of the Police Historical/Archival Investigative Files, a collection of police surveillance records that reside at the City of Portland Archives & Records Center (PARC) in Portland, Oregon, USA.

During the early 1920s to the mid-1980s, the Portland Police Bureau, like many other urban police departments across the United States including the Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago departments, kept a secretive police unit: a “Red Squad.”

Throughout their existence, Red Squads engaged in physical surveillance activities such as observation, wiretapping, and photography as well as compiling records and dossiers on political and social activists and groups—information that Squads used to disrupt and undermine these groups (Donner, 1990, p. 1–3). In response to a fear of Bolshevism, the Portland Police Bureau formed their Red Squad unit in the 1920s with both private and public funds (Jacklet, 2002a; Munk, 2011, p. 203; Serbulo and Gibson, 2013, p. 12). By the 1930s, Portland’s Red Squad served as an “outspoken rightwing political gang” writes Munk, which spent its money spying on and infiltrating “labor and political organizations, organizing raids and provocations, and engaging in violent strike suppression” (2011, p. 204).

Red Squads were at their peak in the United States during the 1960s, with over 300,000 police engaging in political repression, which Donner defines within this milieu as “police behavior

motivated or influenced in whole or in part by hostility to protest, dissent, and related activities perceived as a threat to the status quo” (1990, p. 1). Munk correspondingly notes an enlargement of the Portland Police Bureau’s Red Squad at this time, stating that the “revival of activism in the 1960s caused an expansion of the Red Squad, whose files were quickly filled with informer reports and photo surveillance of Portlanders exercising their political rights” (2011, p. 157). The increased monitoring of activists— especially civil rights activists—during this period was also heightened in part by the federal government’s efforts to disrupt the civil rights movement in the late 1960s.

It was during the mid-1960s when Portland Police Bureau Red Squad member, terrorism expert, and member of the radical right John Birch Society, Winfield Falk, along with more than 20 officers who were part of the Bureau’s Criminal Intelligence Unit, whose mission was “to prepare for and prevent acts of political violence and terrorism” (Jacklet, 2002b), started focusing their surveillance activities on mainly left-leaning political and civic activist organizations. This included surveilling both law-abiding groups (e.g. the police kept watch over those who supported the civil rights movement or were against the Vietnam War) and

those involved in criminal actions. The police monitored rallies, marches, lectures, school board meetings and kept watch over the homes of political activists (Jacklet, 2002a). Although the police monitored groups and not individuals, the names of at least 3,000 individuals do show up in the Files, in documents such as intelligence reports as well as in posters and newspaper clippings in which their names are highlighted or underlined (Jacklet, 2002a). During their surveillance activities, the police created numerous intelligence reports, took surveillance photographs, and collected a wide range and a substantial number of materials produced by activist groups, such as posters, flyers, event announcements, brochures, magazines, and tabloid newspapers.

The police kept watch over 576 activist and civic groups, including the Black Panthers, Students Against the Draft, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, Women’s Rights Coalition, American Indian Movement, Foundation for Middle East Peace, and the Portland Town Council, to name just a few. The police kept file folders for each organization arranged in a quasi-alphabetical order, such as “A is for America—as in American Indian Movement, American Civil Liberties Union, American Friends Service Committee. B is for Black: Black Panthers, Black United Front, Black Muslims. C is for Communists” (Jacklet,