Multi-stories.

Urban Pamphleteer

Urban Pamphleteer # 11:

Multi-Stories. Estate interventions in London and Paris.

Martine Drozdz, Andrew Harris, Nathaniel Télémaque

We are delighted to present Urban Pamphleteer # 11

In the tradition of radical pamphleteering, the intention of this series is to confront key themes in contemporary urban debate from diverse perspectives, in a direct and accessible but not reductive way. The broader aim is to empower and inform citizens, professionals, researchers, institutions, and policy-makers, with a view to positively shaping change.

#11 Multi-stories. Estate interventions in London and Paris.

Looking at the banlieues in their banality, in their ordinariness, is also doing something political because we never look at them like that Alice Diop, film-maker.

This issue documents and explores experimental interventions in the way the everyday life of multi-storey social housing in London and Paris is represented and understood. It addresses how postWar multi-storey residential developments, that conjoined stateled welfarism with modernist architectural aesthetics, has often been framed through a problematic visual rhetoric of violence and criminality, or relegated through increasing attention to up-market residential new-builds and commercial skyscrapers.

Interspersing contributions from Paris and London, the issue foregrounds approaches that develop intersections across visual, ethnographic and historical methods. These counter and re-imagine the widespread past and present stigmatisation of these spaces. These are approaches — forged across personal, institutional and academic contexts, stories and experiences — that seek to intervene in direct and specific ways with the marginalisation of these important locations for everyday urban life.

The responses in this issue form four blocks. Representations questions and criticises inherited images and their impact on our imaginations and seeks to open up new ways of thinking about and presenting multi-story neighbourhoods. Far from portraying these areas as exceptional, perpetually isolated areas of London and Paris, Spaces of the ordinary celebrates the everyday lives that persist and flourish. Inside the Block takes us into the intimacy and intricacies of these locations, before we explore the role for their Conservations: how collecting multiple memories and experiences reveals and highlights — far from the recurrent stigma — the many attachments residents crucially have to these urban settings.

r e p r e s e n t a t i o n s

Cloé Korman

In 2005,1 France didn’t yet have a populist conservative media like Fox News or Sky News. So, during the riots that followed the scandalous and heartbreaking “death for nothing” of the teenagers Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré on the 27th of October in the Parisian suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois, it was the cameras of the mainstream television channel, TF1, that were the most present on the ground. And so the images they captured were the most widely received by the nation’s public.

Virgil Vernier’s film, Kindertotenlieder (“Song for the death of children”), based on Gustav Mahler, is a fascinating short film first shown during the “Cinema of the Real” festival that took place in 2021 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The film allows us to revisit these images and the destruction they captured, to relive the ransacking of the city as the product of a media war that we have yet to escape from.

The film was initiated by the art writer and editor Éric Reinhardt, a child of Clichy-sous-Bois, to whom the city has entrusted the artistic direction of an exhibition that will accompany the programmed disappearance of ChênePointu, the neighbourhood where the riots began in 2005. 16 years later, the violence of these riots appears as the threshold of a sordid era for the suburbs (banlieues) and the council estates in which their generalised weariness and continued decay is reaching another peak. 2005 marks the moment when the government and the media reinforced a socio-economic stigmatisation of the suburbs which persists to this day.

The title of Virgil Vernier’s film, as well as its musical form, gives its scenes a rhythm that is at times contemplative. It fixes in our hearts the memory of Zyed and Bouna by recalling a grief at the centre of what transpired. The filmmaker’s careful edits clean the scenes of the voices of journalists, as if ironing them out, focusing our attention where it is most due. By restoring the respect owed to the pain of the parents, the victims, and the residents of the city, Vernier turns attention to a powerful experience pulled from the archives of TF1.

The film brings together an accumulation of stunning destruction: the cameras stutter incessantly as flames rise in the distance, the corpses of buses and cars are taken away, schools and shops are destroyed, and residents’ voices are distraught, bruised. But when seeing these flames, and the black silhouettes of rioters emerging from them, one also notices the curious absence of any recording equipment. The rioters are never interviewed and the journalists are never capable of making connections at the scene that would allow their testimonies to be heard. They are there like the verticality of the buildings, like the asphalt of parking lots or streetlights: they are atmospheric urban phenomena.

The journalists’ work follows that of the police: during the confrontations their shields are the foreground, never surpassed or filmed from the other side — as they would be for any conflict in the world that the press would attempt to cover from several angles. The absence of the viewpoint of the principal actors is replaced by a different glossary of images, most notably a press conference at city hall where a public meeting is organised,

The images and the sounds from this film are drawn from the television broadcasts of TF1 aired between the 27 October and the 17 November 2005

cameras at the ready, to equip residents with personal fire extinguishers. This absence testifies to a laziness, a cowardness, or to an appalling political choice by the journalists.

The violence that took place from October to November 2005 marked a watershed moment in French journalism in the coverage of the suburbs. Residents of council estates, as the subjects of this stigmatising media rhetoric, noticed immediately the change. To challenge this monolithic perspective, a sharp and incisive “insider” news site for working-class neighbourhoods, Bondy Blog,2 successfully established itself in the media landscape the same year.

1 A longer version of this text was published in the magazine AOC, 14 February 2022 as “Le point de vue des émeutiers - sur Kindertotenlieder de Virgile Vernier” https://aoc.media/ critique/2022/02/13/le-point-de-vuedes-emeutiers-sur-kindertotenliederde-virgil-vernier/. It was published in an amended version for the catalogue of the exhibition Chêne Pointu. Clichy-sous-bois, edited by Eric Reinhardt and published by Atelier EXB. All images are taken from the short film Kindertotenlieder, directed by Virgile Vernier and presented at the Centre Pompidou, in partnership with Ateliers Medicis, during the cycle of screenings selected by Alice Diop in February 2022.

2 https://www.bondyblog.fr/

3 A racist term used in France to refer to people of North African descent, which evokes the word “biquet”, i.e. “goat” in French. Cloé Korman is a writer.

The images of such murderous, hurtful and demeaning acts, are more relevant than ever before. Today, videos taken by citizens are playing a major role in the fight against police violence. In April 2020, for example, a passer-by filmed police officers insulting a suspect who had jumped into the Seine to escape them. The officers were filmed shouting “a bicot 3 like that can’t swim” and suggesting they put a ball and chain in his foot before fishing him out and taking him to the station. This video led to the indictment of the officer who had

uttered the insults. This was only a month before George Floyd’s agony was also filmed by witnesses on the other side of the Atlantic. One of these witnesses was an eighteen-year-old girl named Darnella Frazier who received a special Pulitzer Prize for her work. Floyd’s death sparked an international movement against racist police violence. And in 2023, it was once again the actions of a passer-by spontaneously deciding to film that made it possible to document the murder of young Nahel Merzouk in Nanterre, sparking a new wave of riots and awareness of police abuses in France.

“Breaking everything that moves, burning, so that everyone wakes up” — this hymn from the riot, yelled off camera at one point in Vernier’s film, should be understood through its dignity. “That everyone wakes up” is a noble purpose, a democratic necessity, and it has an immense subversive force of which the weight of its aggression, its difficulty, and courage cannot be ignored. For all those who create, film, and write, this slogan must be read as reciprocity in the form of violence, as the capacity to respond to violence.

Unsoldering TF1’s images of the past and the present, or other images and other words that still debase us today; questioning the arrogance of certain media outlets; representing the political acts obscured by dominant representations: this is what the deaths of the two teenagers in Clichy-sous-Bois still call us to do, sixteen years on.

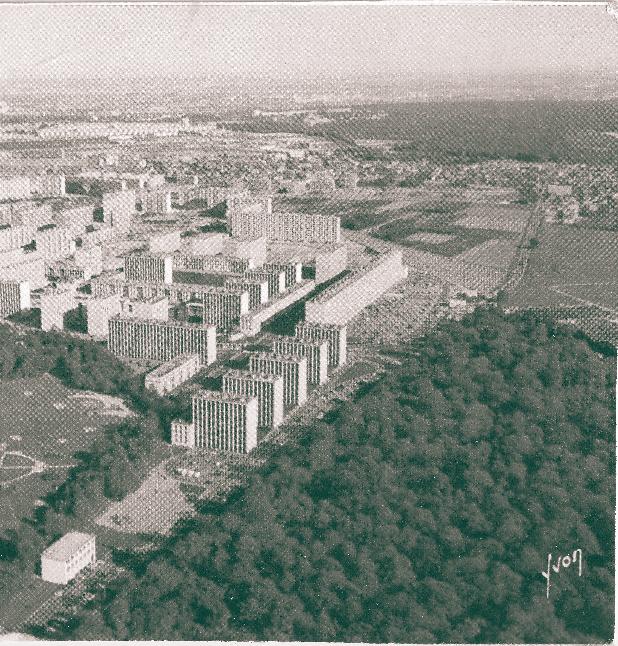

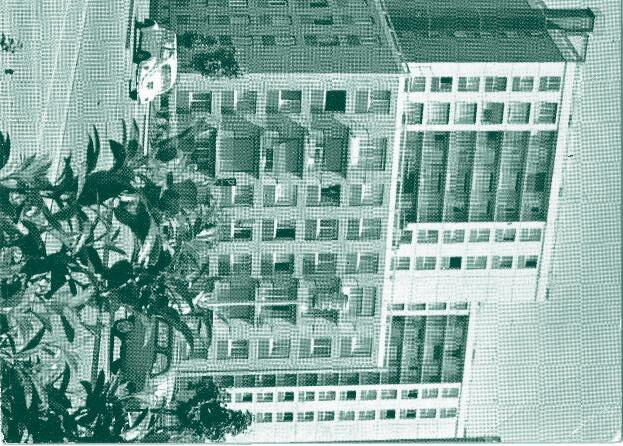

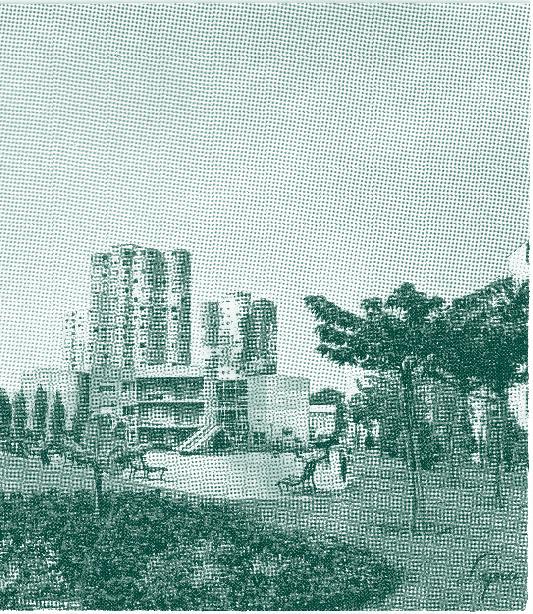

Renaud Epstein

The large social housing complexes built en masse by the developmental state in the decades after World War II transformed the landscapes of French cities. Their construction was accompanied by the even more massive production of postcards depicting them. National and local editors published thousands of these small cardboard rectangles, which were then sold from stores in the neighbourhoods that appeared in them. The majority of these cards reproduced aerial photos depicting the beautiful layout of towers and long buildings that make up the housing complexes. Other photos, taken from the ground, foreground the equipment and well-maintained outdoor spaces of these modern buildings.

These commercial images appear, at times, faded and, at others, so vivid that you might believe they had been transformed by an Instagram filter. They take us back to a time, not so long ago, when France’s large social housing complexes were synonyms of urban modernisation and of social development, a time when they were the pride not only of those who built them but also — as the widespread purchasing and sending of the postcards attests — of those who lived in them.

Half a century after having built them, the French state initiated in 2003 a vast program of urban renovation involving hundreds of these housing complexes. So, I started to collect postcards of the neighbourhoods that would soon be demolished, in order to create a visual archive of a world soon to disappear. After having collected several thousand, I started sending them out on Twitter in 2014, where I published until 2023 a daily series “A day, a ZUP,1 a postcard”.

This series interrogates the common representation of social housing complexes through several expositions, teaching workshops and the publication of an edited volume.2 In contrast to a stigmatising and uniform image of these neighbourhoods that allowed — and still allows — millions of citizens and immigrants in France to access decent housing, these cards show the diversity of urban forms, architectures and environments in which the social housing complexes are located. They allow us to measure the scale of the urban transformations of recent decades in which these once peripheral neighbourhoods were overtaken by urban sprawl, their buildings degraded and their spatial unity dissolved under the pressure of demolition and reconstruction. The contrast between today’s negative image of social housing complexes and their positive image of the past is even more striking when we turn the postcards over to read the short texts written by those who lived in them.

The impact of circulating these images of social housing on the internet is surely limited when compared to the surplus of depressing images which regularly appear in the media today. Reactions from current and past residents show, however, that they nevertheless have had an effect. The images remind us that

popular neighbourhoods have a history and that this history remains an integral part of the national history of France. They remind us that each neighbourhood is singular and unique and never devoid of positive qualities, that they are a source of pride and recognition for their residents.

1 In France, a Zone à urbaniser en priorité (ZUP) is an area that was designated by authorities for the construction of large housing complexes to respond to the urgent need for housing in the 1950s and 60s.

2 Renaud Epstein, On est bien arrivés. Un tour de France des grands ensembles, Le Nouvel Attila, 2022

Renaud Epstein is professor of political sociology at Sciences Po Saint-Germain-en-Laye. His work focuses on urban policies, particularly those aimed at disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

‘We felt very magnificent

When I knew I had to live here and I didn’t have any choice, I wanted to run away, I didn’t know anything about the tower. As soon as I moved in to the 21st floor I just total fell in love with it.

In December 2015, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets approved plans to refurbish and privatise Balfron Tower.

It was very very friendly which I was surprised at. The older people speaking in the lift to you. You know the young lads mucking around. It was really lovely.

In the preceding three years I supported residents’ tireless campaign for it to remain a beacon for social housing.1

I was here forty-odd years. I loved it. Everyone would help one another. You knew your next-door neighbour, you knew everyone. Even in the block, because as we moved the whole street moved into the block with us. So we still knew everyone and there was such a friendship and everything.

‘We felt very magnificent being up there’

Throughout its life certain judgments of Balfron Tower have been accepted uncritically — correlating its architecture of dramatic proportions with a way of life as stark and severe, ill-suited to the needs of families, and at a high density in which socialisation is difficult.

It’s a very communal view and often there are kids playing in the sunken playground. It’s been lovely these past few weeks of summer to come home and have a cup of the tea on the balcony and just listen to the sound of activity below.

Feature films exploit Balfron’s height and style as inherently unsafe and violent: in 28 Days Later frothing zombies scale the tower in vicious bands; in Blitz the tower is the home of a strutting psychotic serial killer; in For Queen and Country, Greenwich Mean Time, and Shopping it hosts invariably frightening incidents.2

You don’t really watch TV when you live somewhere with a nice view… every time you look out you can see different things.

Ernö Goldfinger, the tower’s architect, theorised that the sensation of space cannot be experienced by contemplation from outside, it only comes from being within.

1 See Balfron Social Club, 50percentbalfron.tumblr.com; Balfron Tower: A Building Archive, balfrontower. org; and Tower Hamlets Renters, towerhamletsrenters.wordpress.com.

2 For Queen and Country, 1988, dir. Martin Stellman; Shopping, 1994, dir. Paul WS Anderson; Greenwich Mean Time, 1999, dir. John Strickland; 28 Days Later, 2002, dir. Danny Boyle; Blitz, 2011, dir. Elliott Lester. Images featured here are stills taken from these films.

3 Oral history interviews conducted by Felicity Davies, David Roberts, Polly Rodgers and Katharine Yates, 2013–14. Grade II* listing upgrade nomination prepared by James Dunnett with support by David Roberts. David Roberts is Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, part of collaborative art practice Fugitive Images and of architecture collectives Involve and BREAK//LINE.

Goldfinger designed with an awful lot of light. You live in the space in a different way. It affects your being. And that’s critical to your entire existenc�.

These quotes are drawn from oral history interviews conducted with generations of residents to describe their everyday experiences.

We felt very magnificent being up there. I think for social housing tenants to lose the view is such a terrible theft of experienc�.

These excerpts were included in a listing upgrade nomination which sought to challenge dominant discourses of the tower and testify to Balfron’s social purpose, integral to its vision and function as social housing. 3

One resident who lived with the view for twenty years fetched a small postcard print of Wanderer above the Sea of Fog during our interview, “That’s me looking out of the window, that’s how I feel looking out of the window. That’s my image of my life in the flat overlooking Londo� .”

What are the Ends and how have they been stigmatised?

Many social housing estates across London are colloquially referred to as the Ends, a term born from Multicultural London English which is the result of widespread migration to London particularly from the Caribbean, South Asia and West Africa. A sizable majority of non-UK born communities disproportionally inhabit the Ends.

In recent years, the Ends have repeatedly been characterised as uninhabitable and antisocial spaces by sensational journalists living outside of these locales. Portrayed as disempowering and ugly, a perceived aesthetic of the Ends forms the bedrock of arguments for their redevelopment with this nearly always followed by gentrification.

In November 2018, the UK Government created a panel of built environment professionals named the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. Its mission was to advocate for ‘beauty’ in the UK’s built environment. A proclamation was made by the co-chair, philosopher Roger Scruton, during a debate about ‘beauty’ on 24th January 2019 at University of the Arts London in reference to the Grenfell Tower fire which took place on the 14th June 2017:

If it hadn’t been so ugly to begin with, the whole problem would never have happened.

Accounts and documents collected from the Grenfell Inquiry highlighted that the cladding responsible for the spread of the fire was added not only as a low-cost method of insulation but in efforts at improving the appearance of the tower.

But the perception of ‘beauty’ is dependent on particular tastes and values. Who decides what is beautiful?

Grenfell Tower was deemed to be void of beauty, and an eyesore for its neighbours. And in the pursuit for ‘beauty’, the rectification directly led to the loss of 72 lives.

By day, Nabil Al-Kinani is a builtenvironment professional with a keen interest in urbanism, placemaking, sustainable development and place vision. By night, he is a cultural producer that uses creative practice to deliver changemaking projects that draw focus on the relationship between spaces and stories. His works include: Authors of the Estate: written by Chalkhill estate, Privatise the Mandem and Pipe Dreams. Nabil credits influential figures like Skepta, George the Poet, Tupac Shakur, and Andre Anderson as sources of inspiration.

Let’s offer an alternative characterisation, one formed from our own framing…

The Ends are modern-day castles. These modern-day castles are inhabited by kings and queens. And the ‘ends’ along with its inhabitants are nothing short of beautiful.

Look at the majesty of our castles through our eyes…

S p a c e s o f t h e o r d i n a r y

‘Documenting the Suburbs as they are.’

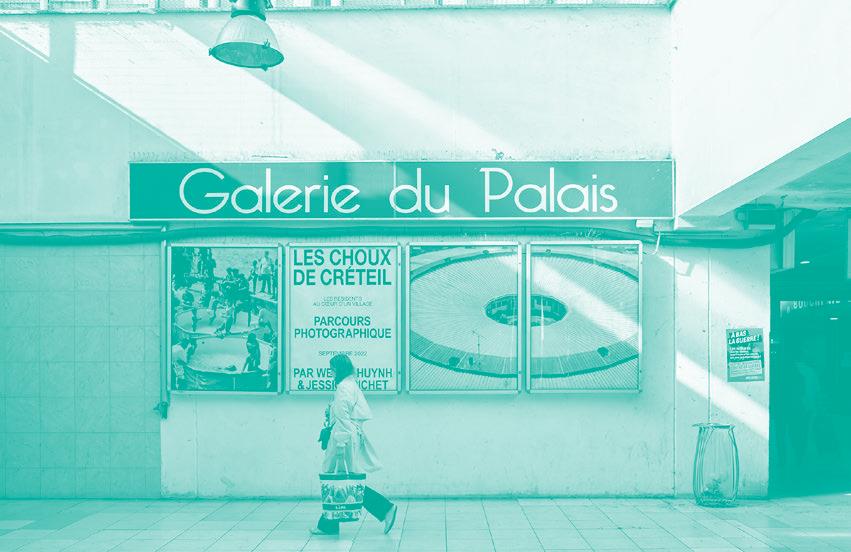

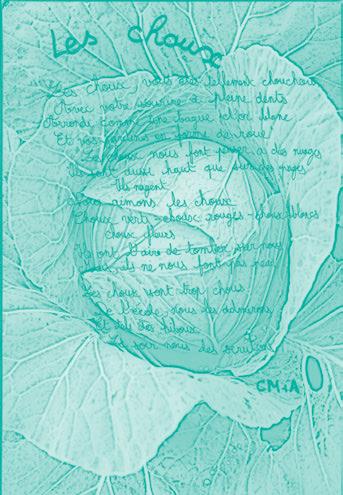

Les Choux de Créteil

Prize ceremony for the drawing and writing competition organised with the local primary schools in Créteil; Artwork by Léa Xia from the CP class, Blaise Pascal school; Valérie Pottier and Martine Bacrot photographed in the courtyard of the local primary school Charles Peguy, summer Balconies of les Choux, Image by Wendy Huynh, July 2021.

Working as a documentary photographer raises several questions concerning its practice — how do you conduct the work and how do you share it internally and externally. As a documentary photographer, I like to see it as a tool to represent the realities of life, something which allows us to put a face on people and places we don’t usually shine the right light on. A physical tool where the camera serves the purpose of representing what is present at the time the image is taken, a tool which almost disappears so the photographer and the subject merge together. However some could sense a sort of hierarchy within documentary photography — is the photographer exploiting the subject? And how fair can the share of interest and collaboration be between the photographer and the subject?

Growing up in the eastern suburbs of Paris, I felt the need to document

with residents that Jessica met while growing up there. With time passing by, we managed to get in contact with more people, including the neighborhood’s ‘social actors’ and local schools.

This project taught us how social practices are defined — we spent time with the residents taking their pictures, recording and filming them, and collecting their archives. The hours spent with them would be time for us to absorb random facts and to learn about their personal experiences of the neighborhood. It felt like the best way to understand them in order to represent their stories truly.

Les Choux de Créteil actually started with drawings and poems made by the local kids during a school competition in 1998, which were all kept by Gérard Grandval. The architect was curious to search for those pupils, wondering what they became. His curiosity kickstarted the project, pushing us to dig in the past and look for archives — this process felt like a constant investigation. And in the summer of 2022 writing competition with the local schools encouraging them to observe their unique neighborhood.

Wendy

based in Paris and London and founder of the magazine Arcades, about the culture and lifestyle of the suburbs. https://www.instagram. com/arcadesmagazine http://www.wendyhuynh.com/

The archives put in context the suburban dis parities, the photos put a face on under-represented communities, the audio video files give them a voice and the drawings made by the kids offer an imagina tive interpretation to Les Choux. They all organically tie together each with the same goal: to tell the story of these unique buildings through the ordinary lives of their residents, far from the clichés of “la vie en banlieue”.

‘Everyday

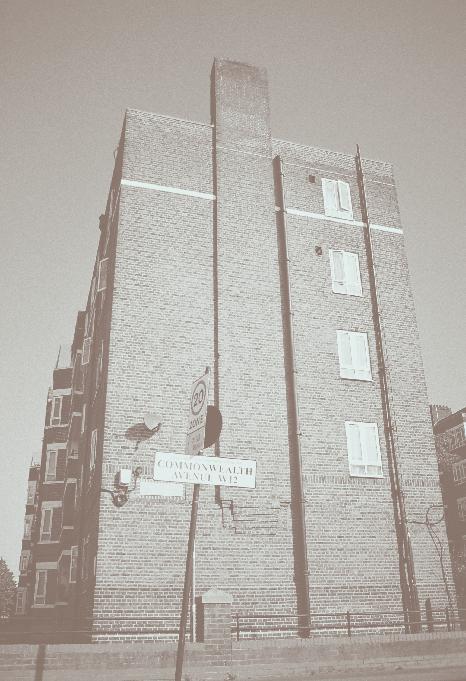

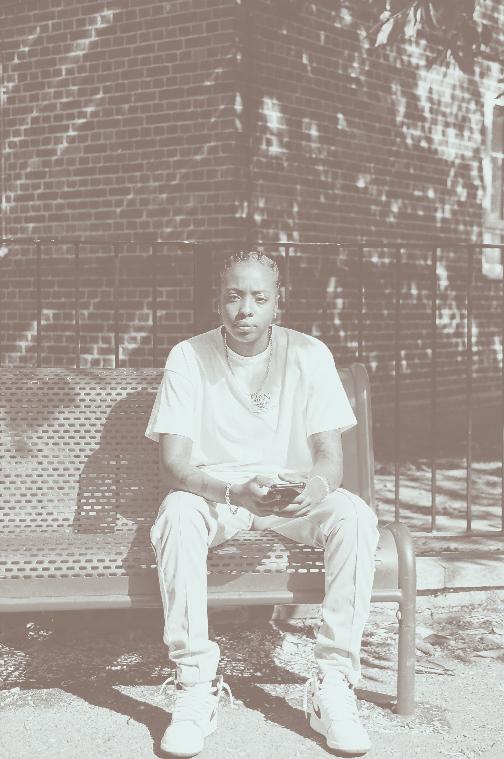

How is your work an intervention in the existing representation of multi-storey social housing in London?

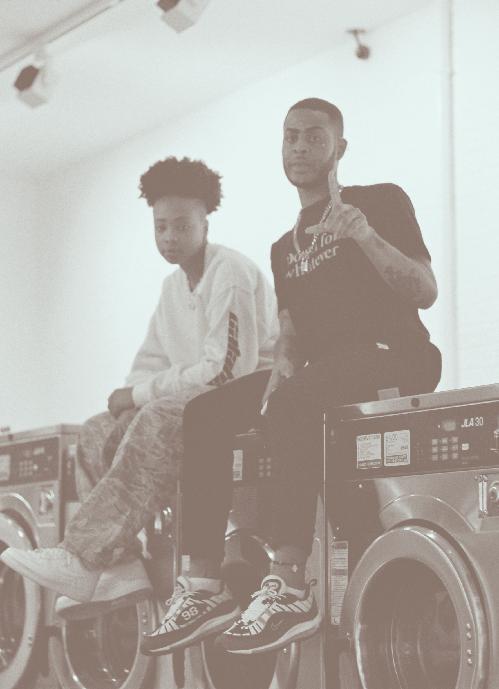

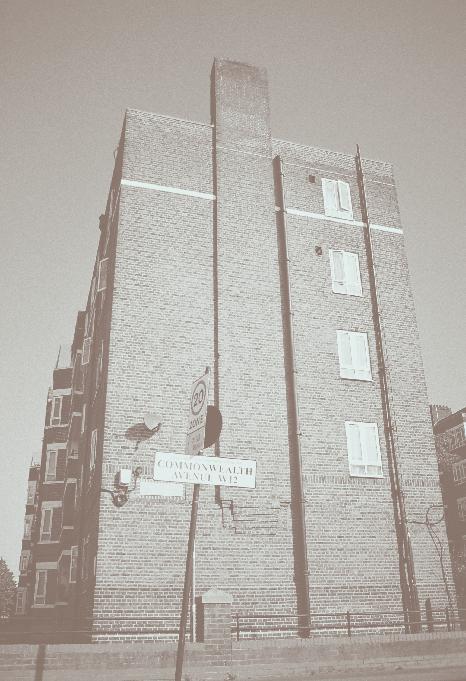

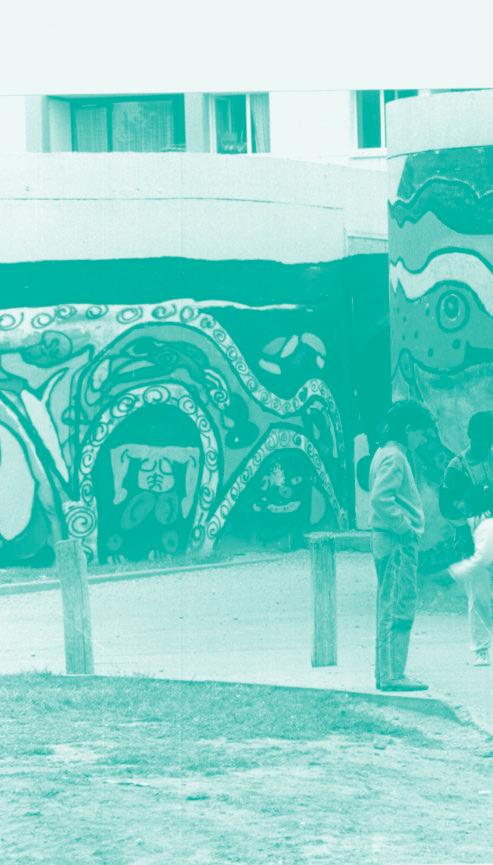

I use archival research alongside visual and textual collaborations taken up with my kinship collective peers living in the White City Estate. This has allowed me to intervene in White City’s representations by demystifying its imperial origins as the 1908—1914 Great White City Exhibition site and utopian inceptions as an L.C.C developed Council estate 1939—present day. Sharing reproductions of archival records, housing block and street name biographies with academic and public audiences at seminars and exhibitions in a local archive has allowed me to raise awareness around the White City’s histories, etymological origins and visual representations. With my White City peers Crizzy, Slim, Rell, Rmular and Wavy I have produced and distributed an ‘Everyday Things’ Photobook which features reflections on their perspectives of the everyday and everyday things in White City. I have begun to orientate ‘Everyday Things’ towards becoming an interventional visual archive that is aimed at ensuring White City is understood as a multi-faceted locale alongside reframing representations of Black life in West London.

How do you go about working with people and places, and how do you feature the quotidian or everyday?

I always aim to spend a substantial amount of time learning to understand the people that I make photographs with before I pick up my cameras. However, recently I have been working the everyday into photographic engagements simply by initiating dialogues on what people may believe to be their ‘everyday things’ in different spaces and at different times.

My name is Nathaniel Télémaque A.K.A St.Peso your friendly neighbourhood visual artist, writer and researcher. As a co-founder the Pesolife audio-visual arts collective my cameras’ lenses visually attend to witnessing mad cities, maverick livelihoods and distinct notions of the everyday. My Geography Practicerelated PhD Everyday Things White City: Generations 88—97 intervenes in the histories and representations of the White City Estate, in Shepherd’s Bush West London through, archival research and collaborative photographic activities taken up with a kinship collective of young Black adults who live in the area. Three visual and textual practitioners of note, whose works inspire greatly me are: Ingrid Pollard, Masahisa Fukase and bell hooks.

I also treat places as though they were people in and of themselves. I frequently visit the places I photograph at different times of the day: listening to their soundscapes, observ ing where shadows form and where light falls. I bear witness to how notions of the everyday and different people’s everyday things may change throughout the seasons, so I pay particular attention to these changes; be they the budding of roses from concrete or my peers like Slim starting to photograph his everyday things. What does it mean to make portraits of a place is a key question that drives my photographic practice. ‘Everyday Things’ in White City, West London

She chose Paris in order to find her house there, and she bought a camera with which she found her own language. She built her own history by taking her time in cities, in homes, in countries, by observing the places and the landscapes as well as the faces that appear in them. She searched ceaselessly for places that looked like her or that evoked certain similarities, imagin ing that she could find answers in them.

The photographic project of Greater Paris allowed her to take the necessary time to explore and study these structures and architectures, which are today still called “the suburbs” — a space considered in relation to the city’s centre, a sort of back lot. For the masses of humanity that live in these neighbourhoods, it is as if the city dangles new neighbourhoods and peaceful lives and progress in their faces…but when it comes to offering equal access to them, the city appears to be fresh out.

She saw how certain municipalities were neglected and scorned, where residents’ lives are difficult and filled with thousands of everyday constraints, and where young people are disadvantaged by a form of segregation and by sharp social injustices. All this in one of the most dynamic regions of Europe.

She questioned and photographed the rundown housing complexes of Bosquets in Montfermeil and Chêne-Pointu in Clichysous-Bois. She became an eye witness to so many excesses, tragic stories, urban social struggles, and ambiguous political situations where there still persists an increasingly trivialised social violence. It was here, in October of 2005, that three teenagers, trying to escape yet another police check, took refuge in an electricity transformer. Zyed (17) and Bouna (15) were electrocuted to death, while Muhittin (15) was severely burned and will suffer life-

Tom Wolseley

These pictures, taken between 1997 and 2023, are of the Heygate Estate: a large housing estate in Southwark, South London that was built in the early 1970s but demolished between 2011 and 2014 and redeveloped as Elephant Park. The Heygate had 1200 socially rented homes. The Elephant Park redevelopment has plans for 2,689 homes, more than doubling the density of housing on the land and decreasing the size of the flats. The 1200 social rent flats will be replaced with 92, with 541 ‘affordable’ flats (20% off market rents).

I used to wander through the Heygate with my young daughter, navigating the ‘streets in the sky’, stepping behind the monolithic housing blocks that bordered the main roads to the area they enclosed: low rise, strewn with mature trees. My daughter and I took the ‘scenic route’ through the estate, often to have a fresh orange juice and Papas Rellenas in the Columbian café in the shopping centre on the other side, also now gone, rede-

veloped, like much of London at the moment.

I had been photographing the Heygate for years but it was only as the residents were decanted and the estate was to be imminently knocked down that the urgency prompted me to do it more formally. You can see in one older photograph here that some of the flats are already vacant, their windows shuttered with sheet steel.

Of the many images I took, these pairs are some of the ones I could match up, exact positions from before and after, by scrubbing across the historical timeline of Google maps.

The new estate is more porous to foot traffic, has more ground level amenities, less green space, is busier with a diverse range of people at ground level, but financially exclusive in its demographic of residents. It is markedly different in the way it is run from the surrounding streets, privately policed and maintained.

Within ten minutes of taking photographs of the new Elephant Park I am intercepted by multiple security guards, citing protection of children from photographic intrusion as their justification for apprehending me. It took me

Reproduction/Reinvention: the Heygate and Elephant Park

three months to negotiate the permissions required to take photos of the new Elephant Park development. As I am leaving, the security guards are escorting another man, proselytising on the street, off the estate.

The film camera I used was made in Japan in the 1970s. The digital camera is a new technology, but still using similar lenses to ‘correct perspective’ as the film camera. This perspective control is a process that can be imitated digitally now, but in the construction of the image I still feel the need to have a moment where the image is constructed, where all the contingencies come together, a point where a certain state of affairs is witnessed.

Where the Heygate’s purpose was providing housing for those in need, Elephant Park is primarily using the medium of the city to maximise profit for a global company. As I walk through the streets and feel that transition, it feels light but deep. While the Heygate and Elephant Park are both housing in the city, like the movement from analogue to digital, what may appear similar belies a greater change, from chemical reaction upon acetate to digital data streaming, the social city to the commodity city.

Tom Wolseley is an artist who uses video and photography alongside text/narration. He has made a variety of works linked to this site, such as ‘Estates 2010’, an inventory of the orientation maps of social housing projects across; ‘in memory of tomorrow’ a slide/acoustic

i n s i d e t h e b l o c k

Ensembles 1 is a photographic work created between 2011 and 2013. It is about the everyday living spaces of social housing residents in France and was carried out in the sensitive urban area (Zone Urbaine Sensible , ZUS)2 of La Noue — Clos-Français in the Parisian suburb of Montreuil Seine-Saint-Denis; in the Fenassiers, in Colomiers, a housing complex located in Haute-Garonne; in the ZUS of Viguier in Carcassonne situated in the Aude region; as well as in the neighbourhoods of Argentine and Saint-Lucien, in Beauvais in the Oise area. Going beyond the usual approach of seeing social housing complexes from the perspective of their public spaces, the project aimed to take an approach which privileged showing these neighbourhoods from the interior of their homes. The work included interviews with the residents, photos of their domestic spaces and points of view from the interior to the exterior of homes. The textual part of the project takes the form of a short life story drawn from recorded interviews with each resident from which certain clips were extracted.

This project was born from initial meetings with residents and from the desire to encounter neighbourhoods with social housing that, among the general public, are rarely spoken of. The project’s ambition was to tell the story of a neighbourhood through representations of its domestic spaces and through the words of the people who live in them. These people are not present in the images themselves. But the resulting images are not ghostly, nor are they places amputated of presence. Instead, they are a representation of residents’ living space that shows how people take ownership of their everyday environments. The absence of the human figure is the reflection of a desire to draw attention to these places, to offer the readers the possibility to imagine themselves in these homes and also to imagine who inhabits them. The presence of the residents is revealed by the textual elements of the interviews; the first person perspective is privileged, the text is the voice of the resident narrating their everyday life and talking about their relationship with their living space, whether it is about their home, their neighbourhood, or their city.

In line with similar projects that represent domestic spaces, the relation between the text and the image contributes to the construction of an imaginary of the everyday. The photos and the texts create a mirror effect in which it is possible to imagine one’s own universe. The visible objects mercilessly display social belonging. The words of the residents narrate the relations of living, of contemporary modes of life. It is neither a denunciation nor an inventory, but the transmission of a reality. The absence of people in the images doesn’t make them less real, thanks to the objects whose presence and arrangement express a cultural fact. In this sense, the work is like anthropology. Practising this type of photography is about participating in the field of contemporary photography by using a method borrowed from the social sciences and by collaborating with sociologists, geographers and anthropologists. The approach requires a deep

“We were living in a small studio in the 19th arrondissement and had the opportunity to buy a flat in La Noue [housing project in Montreuil] thanks to the 1% housing scheme [a state-funded programme]. The fact that it’s near Paris, in Montreuil, which is a little Bamako, and that my husband is Malian, spoke to us and we said OK, even if it’s ugly when we get there, we’ll go and see it. When you’ve worked hard to pay 700 euros rent for a studio apartment and you can get something bigger for the same price, you say to yourself, we’re going to stay here for a while. The children from the neighbourhood often come to stay with me, but they know that you have to speak properly here because I don’t like the way young people in the neighbourhood speak. I grew up in Boulogne, my mother wanted to buy in Montreuil but my father wouldn’t hear of it.”

immersion on the ground and is anchored in encounters with the people that create these places (residents, local actors, etc.). Crea tion is derived from an original artistic intention, but also thanks to the articulation between text and image. The installation of this articulation invites a dialogue on the ability of photography to represent reality. Each display, whether in the exhibits or in the publications, presents an opportunity to test the possible relations between these two media.

“I was living in another housing estate in Montreuil before. But I’m not from here, I’m from Bourges. When I had a baby, I asked for a bigger place and they gave me this one, so I had no choice. I felt better where I was before. Anyway, I don’t want to stay here, I can’t stand it any more, I want to leave and go back to Bourges. That’s why I haven’t really settled down, I’ve just moved the furniture around. Apart from that, the accommodation is fine, but as I’m not an interior designer, I don’t see the point. I need to be surrounded by activity and shops. When I can get out of my house, I change neighbour-

Ensembles.

Habiter un logement social en France, text by Jean-Michel Léger and Michel Poivert, Grâne, Créaphis, 2014.

ZUS was an official designation used in France between 1996 and 2014 for urban areas targeted for addressing their high concentration of social issues like unemployment, housing insecurity, and poverty.

Hortense Soichet I was born in Toulouse in 1982. I am a photographer. I have been working for around fifteen years on the question of how people invest themselves in their living spaces — their homes as well as the areas in which they live. My projects are often carried out in collaboration with other artists, researchers or amateurs.

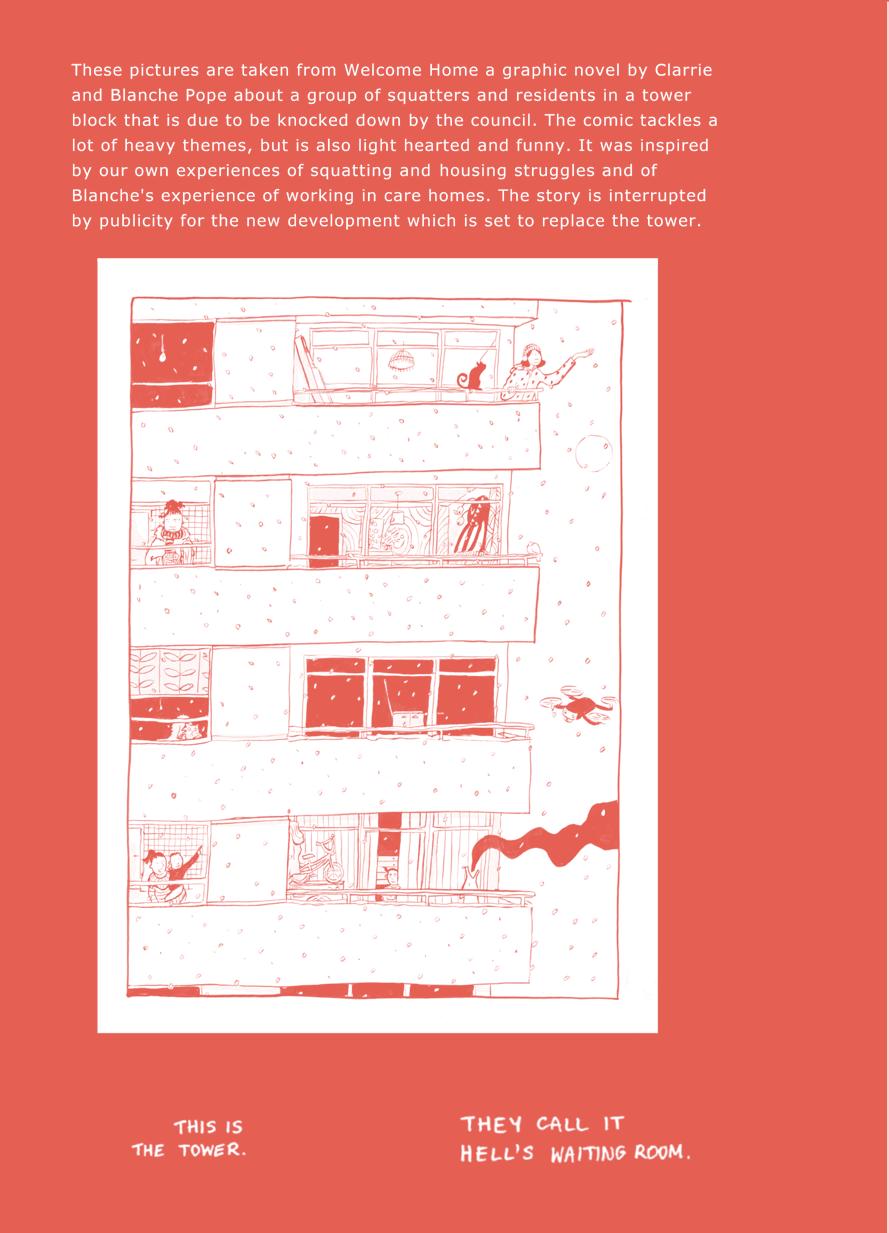

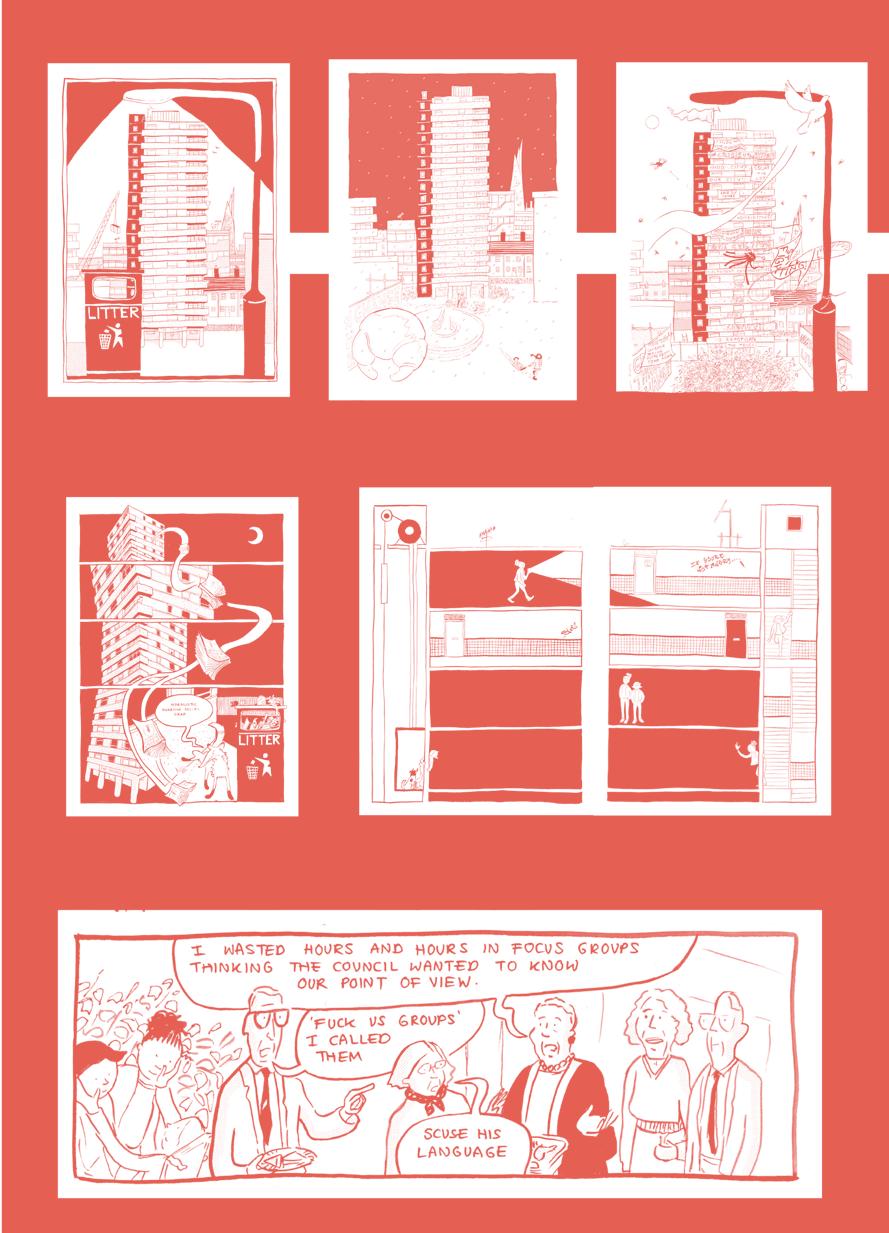

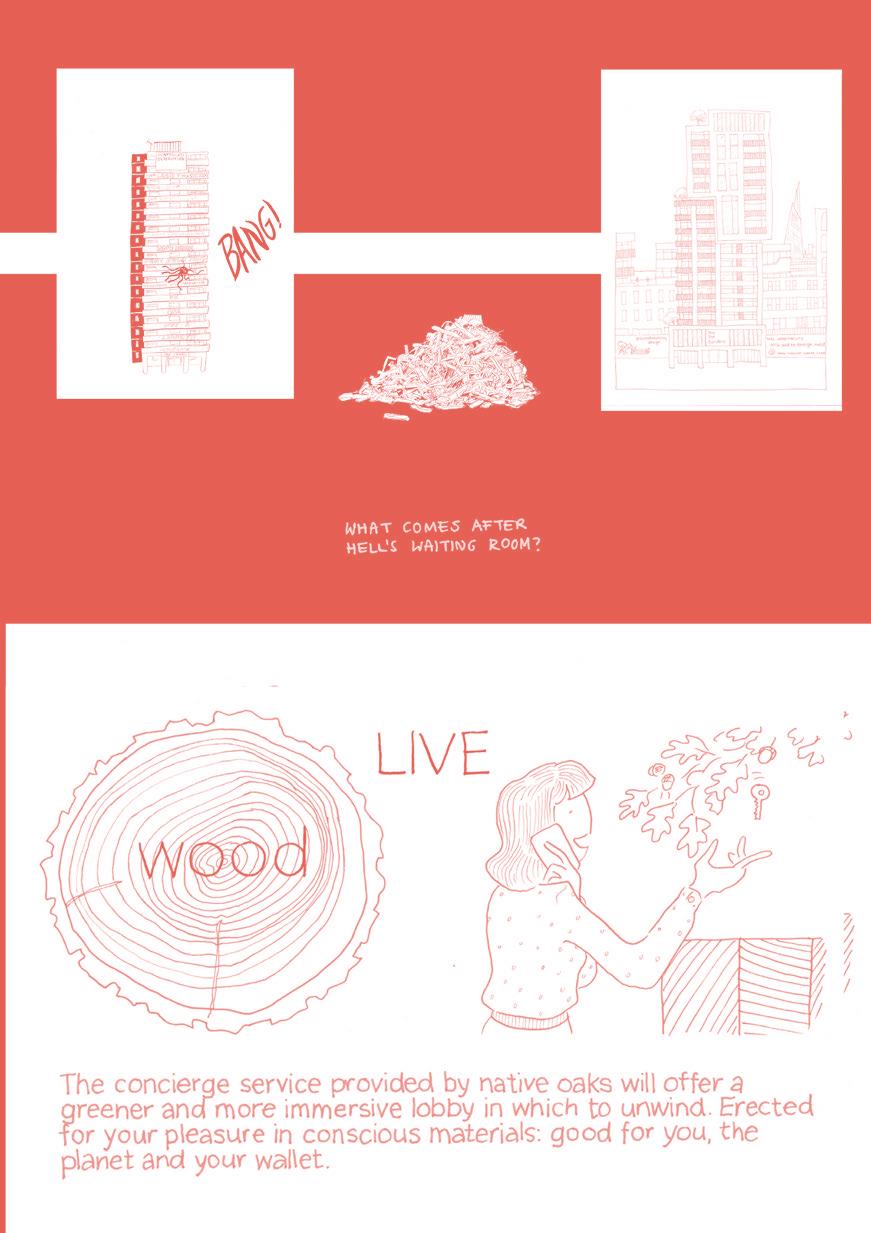

Clarrie and Blanche Pope

These pictures are taken from Welcome Home, a graphic novel by sisters Clarrie and Blanche Pope about a group of squatters and residents fighting to resist the eviction and destruction of their tower block. As you can see in these pages, the stories of their struggles are interrupted by publicity for a new development that is planned to take its place. The comic tackles a lot of heavy themes but is full of humour and hope.

Sisters Clarrie and Blanche Pope wrote Welcome Home based on their own experiences of squatting and housing struggles and on Blanche’s experience of carework. Clarrie is @skyrat_post

When I was little, I thought that we lived at the top of the towers to get closer to the birds and the stars. As I grew up, the towers started to fall and all around us the horizon changed.

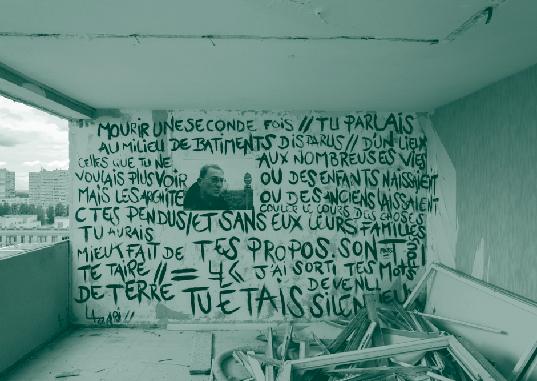

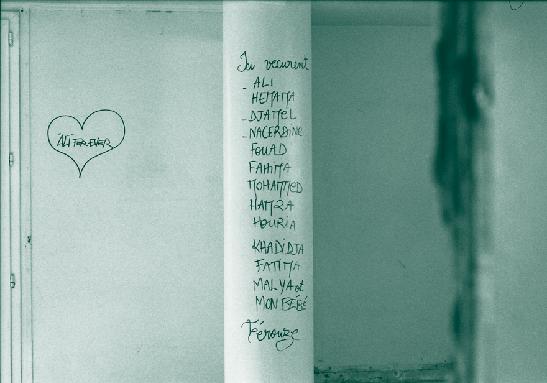

In 2019, I visited the demolition sites for the social housing complexes of greater Paris. I took notes in my notebook, I took photos, I met the residents. I had no idea what I was going to do with all this, but I had the feeling that I was obligated to keep and to save what I could.

In January of 2020, at the time I started at the Kourtrajmé school founded by Ladj Ly, I walked into Building 5 of the Groves housing complex in Montfermeil. Long and low-lying building with broken windows. I spent the last year before its destruction with this building, and with the people who had lived there. A year spent between anger, nostalgia, longing, destruction and transformation.

I ensconced myself in the demolition site, I maneuvered through the gray zone without permission. An interstitial zone built slowly, little by little. At first glance, everyone thought that I was there for a legitimate reason. I waited several weeks before taking out my camera. Instead, I observed, waited, hung out without forcing any friendships. They were my age and they were breaking their backs and their

health for abysmal pay. They worked in the cold then the heat, destroying the walls with sledgehammers. Many among them had grown up in the building they were demolishing. They were destroying their childhood homes. I photographed them in their apartments, in their parents’ bedrooms.

During the summer of 2020, I started to paint, write and glue these photos in the building’s open empty rooms. I made friends in the housing complex and, in the evenings, I brought them up to the roof of B5. During the day, hidden in bags from the demolition site, I brought up packs of soda to drink while watching the sunset. At nightfall, we went down the stairs with paintbrushes and markers. I showed them what I had created and then we wrote on the walls around the collages, the photos of their faces. We called these evenings “exhibitions in the wild” (les vernissages sauvages). Without planning it, these moments of expression allowed life to return amid the smell of plaster dust and destruction. Accompanying the building in its final summer, we had the feeling that we were keeping alight the eternal presence of its residents between these walls that were soon to disappear.

Finally, in the fall, the machines arrived and in two months this enormous vessel of concrete became a field of ruins, a ghost living only in the heads and hearts of its former residents. After 56 years of life — a life that was a story of exclusion and of segregation but

also of love, of belonging and of pride.

B5 was the last of the historic buildings of the Groves housing complex, last monument, last vestige. The destruction finally stopped for the residents after 26 years in the dust and the ballet of the demolition machines.

These walls carried the life and the memory of thousands of people. I felt like I was saying a final goodbye to a dear friend, without having known him entirely or for very long. These months with building 5 allowed me to understand and fix some things from my past. I accompanied it into its new life of ruins and memories, as it had guided me in mine.

c o n s e r v a t i o n s

Founded in 2014, the Association for a Museum of Social Housing (AMULOP) is an organisation of university professors, high school teachers, and professionals of historic preservation working in the Parisian suburbs. The association advocates for the creation of a museum that would collect and display the history of Paris’ working-class suburbs since the eighteenth century. The museum is anticipated to be located in Seine-Saint-Denis, a Parisian suburb emblematic of working class political unrest and whose residents have long been subjected to stigmatising and stereotypical representations.

To build anticipation for this future museum, l’AMULOP organised the exhibition “Life in Council Estates: residential histories of social housing, Aubervilliers, 1950—20003”. The exhibition took place in Aubervilliers from October 2021 to June 2022 in the housing project Émile-Dubois, which is often referred to as the “complex of 800” due to its large quantity of homes (800, to be precise). Like its neighbour Saint-Denis, Aubervillliers is emblematic of France’s industrial suburbs.

In order to speak to the public as concretely and vividly as possible, l'AMULOP took inspiration from the museographical approach of the Tenement Museum of New York: “Life in Council Estates” tells the story of families who actually lived in Émile Dubois by reconstituting the interior of homes from different periods. This immersive approach allows visitors to understand in situ the everyday life of the residents of working-class neighbourhoods. It focuses on the material dimensions of social housing, while also giving access to the more intimate experiences of domestic space.

The exhibition reconstitutes the experiences of residents and how they lived in social housing. In doing so, it explores the great social, economic, political and cultural transformations of French society as they were lived in its suburbs: industrialisation and deindustrialisation, wars, decolonisation, social and political conflicts, transformations in gender relations, access to health care and leisure, migration and discrimination, urban change. This approach aims to break with media representations focused on moments of crisis and, in contrast, presents ordinary residents’ diverse identities and everyday life in all its social complexity.

The exhibition is located in a large housing complex in Aubervilliers, Émile-Dubois, built in 1960. In 2014, an “urban renovation” programme was undertaken in which the municipality agreed to offer the use of the Grosperrin building located in Émile Dubois. To develop the exhibition, its organisers led a deep historical study and spent nearly a year both in the archives and alongside former and current residents of the building.

Two apartments offered contrasting visual experiences of the

exhibit. The first apartment entirely reconstituted the home of the Croisille family — who lived there between 1957 and 2012 — to resemble its appearance in 1967. A tour guide offered an interactive story of the life of this workingclass family, of the everyday life of its various members, and the transformation of their relation with the housing complex. The guide presented family photos, letters and excerpts from testimonials, and the material features of the home itself.

In the second apartment, each room corresponds to a story of a family at a specific time, organised around residents’ everyday struggles that are revealed through the presentation of several objects. Still accompanied by a tour guide, visitors are introduced to the difficulties of one resident, Marie, in finding housing in 1957. Then, they explore the ascendance of one Italian family — the Dimeos — into consumer society in 1968, thanks to the inclusion of women into salary work. The crisis of the Émile Dubois housing project in 1985 is presented through the perspective of Marie and, finally, the visitor is presented with the activist work that one Malian mother named Madale Soukouna undertook in 2005.

Association pour un musée du logement populaire (AMULOP)

Muriel Cohen Lecturer in contemporary history Le Mans Université TEMOS (UMR 9016).

Sébastien Radouan Lecturer of architectural history and culture École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Paris La Villette Équipe AHTTEP du laboratoire AUSser (UMR 3329).

The exhibit aims to make visitors aware of the issues facing residents in poor neighbourhoods, of the cultural heritage of their city, and of the role of these places and their residents in French history. L’AMULOP also intends to offer a different perspective on the representations and difficulties of poor neighbourhoods. The dominant interpretation often stigmatises poor suburbs by explaining their poverty in cultural and ethnic terms. In contrast, the exhibit focuses on the social experiences and struggles residents face every day. It aims to promote the role of large social housing complexes in the improvement of the living conditions of working class people since the twentieth century. Since 2003, however, the National Agency of Urban Renovation (ANRU) has been attempting to erase this type of social housing from the urban landscape.

When Aysen and her sister Pinar were given the keys to their council flat on the 8th floor of one of the high rises on the Aylesbury Estate in South London in 1993, they danced in the empty rooms, filled with joy. Having spent their youth active in the left and underground circles of their native Istanbul,

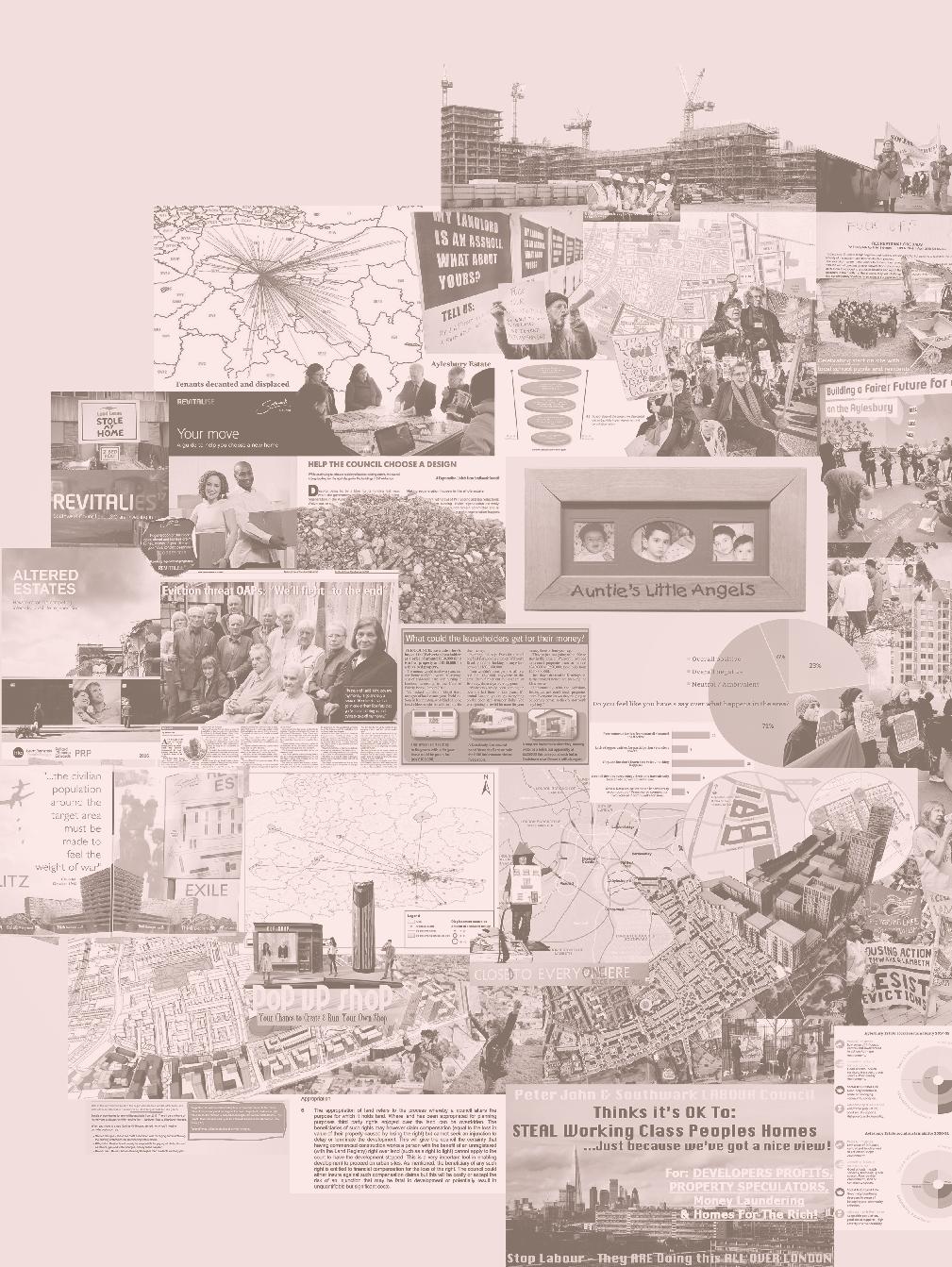

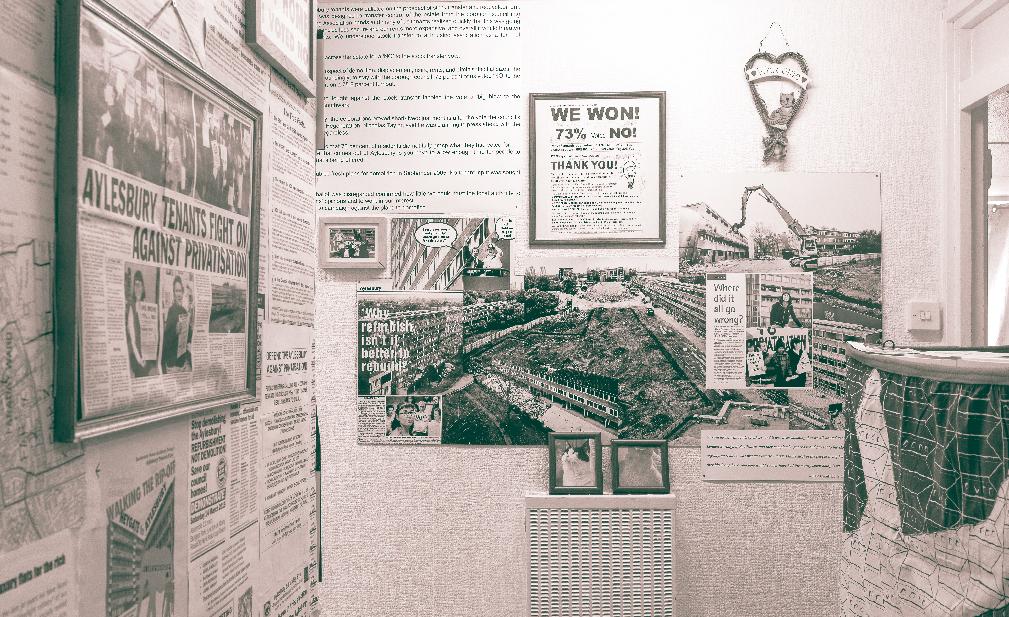

Previous page

Part of the collage placed in Aysen’s corridor using extracts from the council’s and developers’ leaflets, press articles, campaigns photos, etc.

Opposite above Aysen’s entrance hall with in the middle the framed poster celebrating the 2001 victory of the residents against the Estate’s stock transfer and redevelopment.

Opposite below Aysen’s kitchen covered with memories of her life on the estate.

the sisters moved to London in the early 80s. The shift was not easy, and finding a political and material home in the new city took time.

They could not have imagined that 30 years after moving in, their muchloved flat would become a living exhibition attended by hundreds of visitors over the course of a month.

The Aylesbury Estate was built during the tail end of the post-War drive for municipal housing construction in the UK. Since its early days, the estate has been criticised in the architectural and mainstream press, for its size, design and building materials. Expressions like ‘sink estate’, ‘Hell’s waiting room’ and other classist and racialised tropes have been used to describe it for decades now, despite the ongoing protestations of residents and housing campaigners.

When in 1999 the estate was placed under a major urban regeneration programme, it didn’t take Aysen long to understand that the plan was a drive towards privatisation. Together with other residents and supporters, Aysen started campaigning, at first against the plans to ‘stock transfer’ the ownership of the housing away from the local administration to a housing association, and later against plans to demolish the estate altogether.

The campaigners used a range of tactics over the years: from door knocking to producing a printed newsletter, to organising demonstrations and public meetings, squatting empty buildings, and, once, even standing for local elections. The campaigners created networks of solidarity with other estates in struggle across London, and always linked their analysis to global processes of gentrification and social cleansing. Whilst Aysen was out in the streets, Pinar held down the fort at home, and at the same time ran an active social media channel supporting the Kurdish cause.

Alessia Gammarota is a documentary photographer and designer. Her practice is rooted in community engagement and participatory processes. Aysen Dennis is a housing campaigner who has been fighting against the ‘regeneration’ of her home for more than 20 years.

Caterina Sartori is a visual anthropologist dedicated to co-creation and engaged research practices. They are part of Fight4Aylesbury, a collective of residents and supporters campaigning against the demolition of the Aylesbury Estate.

Instagram @fight4aylesbury Twitter @aylesbury_exhib

Pinar tragically passed away at home in early 2019, leaving a large void. Concomitantly, work towards the demolition of their building was also progressing. Aysen’s response was to create a tribute for her sister and a celebration of 20+ years of housing struggles inside her flat, in the form of an installation, open to the public. With the support of photographer Alessia and researcher Caterina, and a collective of neighbours and campaigners, the exhibition Fight4Aylesbury was born. Alessia created a tapestry of images, posters, and collages that covered most of the flat’s walls. Artists contributed with songs, videos, poems, sound compositions, flower and leaf installations, writings, and more.

The Fight4Aylsebury exhibition was open for a month in MarchApril 2023, and it welcomed hundreds of visitors who visited the flat and attended 8 public talks hosted in the living room and the corridor. The exhibition wilfully centres residents’ experiences and analysis. Against the backdrop of a relentlessly marginalising public rhetoric, the organisers aimed to uphold a narrative of resistance against the processes of demolition and social cleansing, whilst also making visible the everyday lives that residents continue to create within their homes.

Valibout, the main neighbourhood of social housing in the city of Plaisir (Yvelines, Paris region), is today confronting an urban renewal project led by the municipality and the French National Agency for Urban Renovation. Taking up the discourse about the neighbourhood which regularly appears in the media, the project claims to “unclog” Valibout and introduce a “functional mix of social classes” to respond to the “incivilities” and “anarchic” use of public space.1 The project anticipates the demolition of 56 recently renovated homes, a school and a commercial area (the neighbourhoods main place for socialising) for the construction of roads, private homes and a new mall.

In opposition to this uncoordinated urban intervention, an association of residents, the DAL 78 Committee, is mobilising to construct a militant counter-expertise in partnership with scholars and activists.2 They oppose a project that does not respond to local necessities, but to the interests of the real estate sector. With this partnership, the collective set out to co-author the history of Valibout. Drawing on a series of interviews and workshops conducted with residents and municipal employees and a collection of family and institutional archives, the collective is co-constructing a historical story of the neighbourhood.3 This research is anchored in a deep collaboration between a pair of researchers (a sociologist and a historian) and DAL 78 which aims to collectively develop hypotheses, analyses, and techniques to report back to the community (posters, timelines, pamphlets and research reports).

First, our research sought to historicize

the current conflict by taking account of the different urban interventions in Valibout since its birth in the middle of what was then an agricultural landscape at the end of the 1960s. Our objectives progressively diversified. At the heart of the discourses we collected, there are the memories of different collective spaces, and the lives of activists and the union struggles of immigrant workers. They bring back the places today resigned to memory, and their transformations, as events which mark a common urban history, but also a colonial and working class one.4

This action-research created a timeline that juxtaposes the social dynamics which transformed Valibout. It gives us a glimpse of the long history of interventions of institutional actors and it makes clear the many poorly coordinated and rarely evaluated demolitions of collective spaces that are a recurring, and often arbitrary, feature of the city. It also reveals the shortcomings of landlords and the municipality, and their responsibilities for the mismanagement of buildings and public spaces. For mobilised residents and activists, the timeline is a tool for mobilisation and a call to action that reveals the stakes of this kind of large scale urban intervention. Alongside these spatial transformations, the timeline offers insight into the rich social and political history of Valibout. Although certain forms of obstruction and repression are now aimed at organisations opposing municipal projects, our research underlines the importance of the collective efforts that have long been integral to the neighbourhood. This history reminds us that Valibout was an important place for the emergence of citizen, immigrant and anti-racist struggles as well as a local cultural scene. These dynamics have left their mark in the political and social fabric that, despite its material difficulties, manages to maintain its activities with or without government support. The work of collecting and circulating archives contributes to the emergence of a debate around a common heritage to be defended, a local history to be passed on, in contrast

The first Valibout urban renewal project, 1990. Plaisir municipal archives.

Neighbourhood gathering at the Millefeuilles social centre, n.d. Private archives, Atif Moufakka.

to the silences that punctuate institutional discourse. This visual work, supplemented by written productions, allows us to write an alternative history of Valibout beyond the stigmatising narratives that structure urban renewal projects.

1 Preliminary consultation file, November 2021, City of Plaisir.

2 Le Comité DAL78 partnered with the association APPUII, Alternative For Urban Projects Here and Abroad, which offers technical support to resident organisations.

3 This action research was carried out as part of Copolis, a FrenchBrazilian research project focused on urban co-production and financed by the French National Research Agency and the São Paulo Research Foundation.

4 Elise Havard dit Duclos and Philippe Urvoy, “Coécrire l’histoire locale face à la démolition des quartiers populaires, de Plaisir (France) à Belo Horizonte (Brésil)”, Les Cahiers de la recherche

architecturale urbaine et paysagère [Online], 15 | 2022, Online since 21 November 2022, connection on 27 March 2023. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/craup/10773; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ craup.10773

Elise Havard dit Duclos is a PhD student in sociology at LAVUE (Paris 8 University / CNRS).

Fatima Idrissi is a teacher, an elected member of the municipal opposition in the town of Plaisir and a member of the residents' collective DAL 78, based in the Valibout district.

Philippe Urvoy is a post-doctoral researcher at LAVUE (Paris 8 University / CNRS) and part-time lecturer at the University Paris Nanterre.

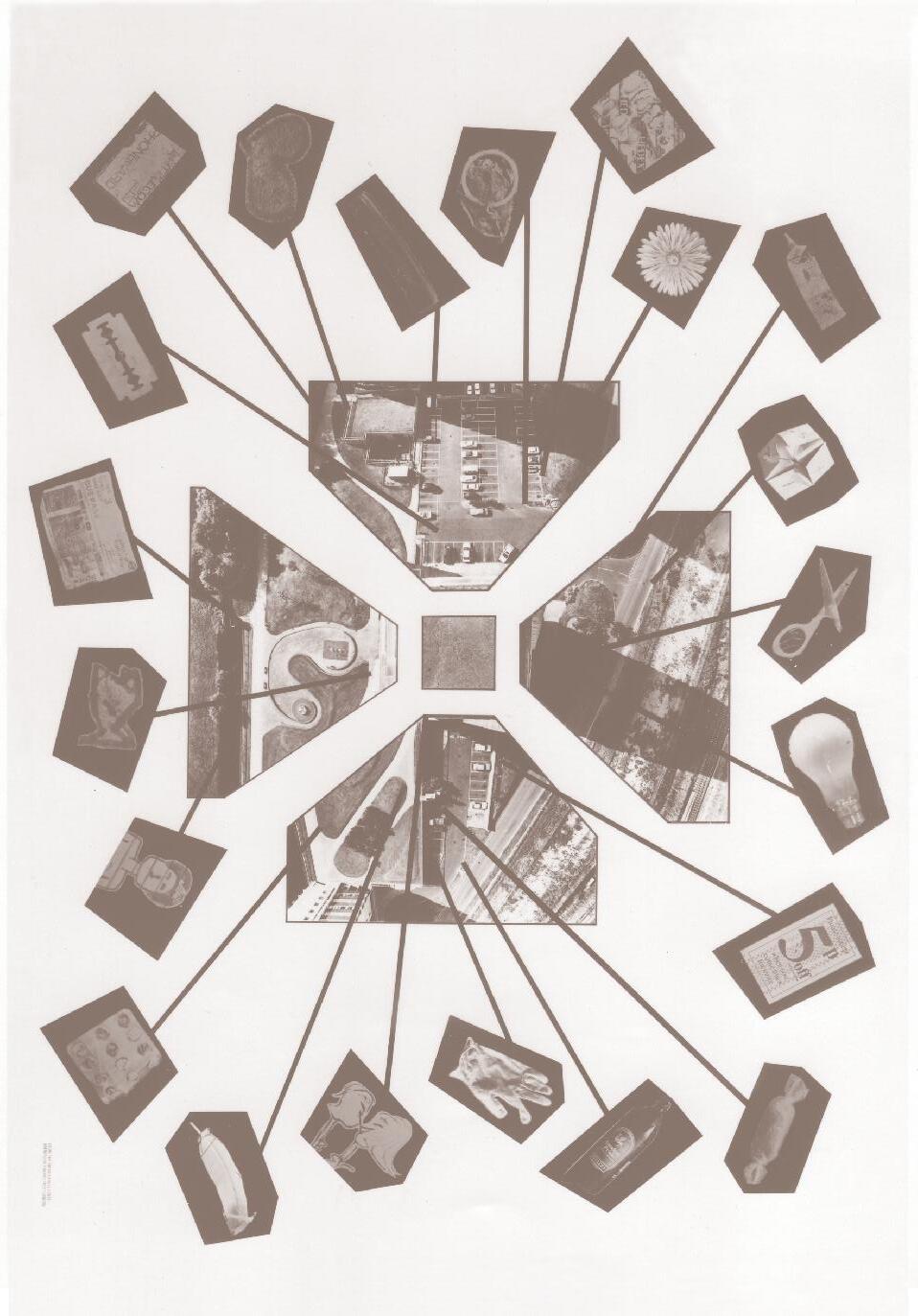

The twenty-two storey tower block, Harvey House, is situated in the middle of the estate known as Brentford Towers, at Brentford, West London. Built in the early ‘70’s by the local council as something of a show piece development, the estate comprises six identical concrete tower blocks, laid out in a line that is down the centre of a landscaped and behaviouraly planned environment, totally reflecting the highly organised architecture. The estate is located next door to the picturesque Kew Bridge over the River Thames, and can be seen by everyone coming in and out of London on the M4 Motorway or by anyone landing at Heathrow Airport, so, like many people I have been consequently reminded of its existence for a long time. Though it is only in the last three years that I have explored it fully, and it has become a site that I have used in a number of my works as a total expression of what I have called the ‘New Reality’.

What has drawn me towards Brentford Towers is the estate’s size (half a mile long by about a third of a mile wide) and its completeness, in that it still has intact all the attendant attributes associated with the ‘New Reality’, such as walk-ways, underground car parks, seats made from concrete, play and community areas, the accompanying prohibitory notices etc. However, another very important factor has been the estate’s containment, its isolation from surrounding areas. It is almost as if you enter a special world, that of society’s institutions: the Housing Department, the Planner, Social Services of various kinds; it is their island that they have created, and which has been purposefully cut off from the mixture of the surrounding neighbourhood. As such, this

contained world powerfully expressed to me the institutional aspirations and idealisations made by the professionals in the optimistic climate of the 1940’s when it was conceived, envisaging a highly planned, paternalistic future way of life. But, of course, while the estate still projects a somewhat worn image of the professional’s ‘New Reality’, it also embodies the stark reality of people’s lives today, the here and now of their isolation and their alienation. This conflict between vastly different perceptions of the same environment is overtly manifest through residents’ constant fight to state to others their own identity, and their need for their own community. Despite the inhibitory nature of residents’ surroundings they still do need to display their fundamental creativity, resulting in a contextual language of signs and messages that they have left behind from various behaviours and activities within the immediate vicinity: I see that residents’ acts of vandalism, directed against the building that they live in, the graffiti they make on its walls, the objects that they discard and perhaps throw out of the tower block itself, all state a consciousness of a people in opposition to the hard, grey, uniform, concrete block that contains their home, and that constantly and unmovingly radiates the message of a higher authority which is ultimately that of society itself. Now, the fundamental creative act is the act of transformation, and I consider the debris of residents’ activities, both casually discarded and consciously placed within the immediate territory of Harvey House, as agents for people to conceptually transform that environment into another consciousness, that of community. For all these traces of activity act as signs to other people, giving notice that that concrete object does have a social identity, moreover one that has been

From The

implicitly self-created by the community, and in the process these traces subvert the imposed consciousness embodied in the tower block’s physicality.

My map of these discarded residues of residents’ activities makes a further transformation through my photographic encoding of what I found during a slow walk around the base of Harvey House over the period of one day. But I started making the map by simply going to the roof of Harvey House and leaning over the side so as to photograph the ground on each side of the block. I then searched the area on the ground covered by my roof-top photographs, and recorded with my camera the different objects and marks that I encountered in my wanderings. These photographed objects were then later assembled into a map that showed where they had been found.

I see that my map is one of people’s everyday social alienation, and of their struggle to express their own identity, and furthermore their need to create their own landscape within contemporary society. In this sense my map of what the residents of Harvey House left immediately beneath them may be considered to contrast sharply with the historical idea of the Parish, and its well-ordered, homogenous community. But not so, for both are social territories that reflect different stages of society, sharing the common element that both were authoritatively defined.

From the early 1960s until today, Stephen Willats has situated his pioneering practice at the intersection between art and other disciplines such as cybernetics, advertising systems research, learning theory, communications theory and computer technology. In so doing, he has constructed and developed a collaborative, interactive and participatory practice grounded in the variables of social relationships, settings and physical realities.

Series Editors

Ben Campkin, Rebecca Ross

Issue Editors

Martine Drozdz, Andrew Harris, Nathaniel Télémaque

Copy Editor

James C. Mizes

Graphic Design

Bandiera, Guglielmo Rossi

With gratitude

Urban Pamphleteer is supported by UCL Urban Laboratory. Urban Pamphleteer #11 has been produced with support from Labex Futurs Urbains | Urban Futures, and UCL ’s Cities Partnership Programme (Paris).

Printing

TW Graphics

Contact

http://urbanpamphleteer.org email@urbanpamphleteer.org

Urban Pamphleteer

UCL Urban Laboratory

Gordon House

29 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PY

Cover

Concrete Roses (2020), by Nathaniel Télémaque.

Back Issues

# 1 Future & Smart Cities

# 2 Regeneration Realities

# 3 Design & Trust

#4 Heritage & Renewal in Doha

#5 Global Education for Urban Futures

#6 Open Source Housing Crisis

#7 LGBTQ+ Night-time Spaces

# 8 Skateboardings

# 9 Reimagining the Night # 10 Museums, Cities & Cultural Power

Available online at urbanpamphleteer.org

Thanks!

Central Saint Martins Graphic Communication Design

The Bartlett, UCL

We gratefully acknowledge the UCL Grand Challenges support that helped to initiate the Urban Pamphleteer series.

© 2024 All content remains the property of Urban Pamphleteer’s authors, editors and image producers. In some cases, existing copyright holders have granted single use permissions.

ISSN 2052–8647 (Print)

ISSN 2052–8655 (Online)

@urbanpamphlet

July 2024

Ben Campkin is Professor of Urbanism and Urban History at the Bartlett School of Architecture, and author of Queer Premises (2023).

Rebecca Ross is Director of the Graphic Communication Design Programme at Central Saint Martins. She is the creator of ‘London is Changing’ (2015).

Martine Drozdz is an urban geographer based in Paris, member of the research collective ‘Futurs Urbains | Urban Futures’.

Andrew Harris is Co-Director of UCL Urban Laboratory where he leads the 'urban verticality' research theme, and Associate Professor in Geography and Urban Studies at UCL.

Nathaniel Télémaque is your friendly neighbourhood visual artist, writer and researcher. He is also a Lecturer in Geography and Social Justice at King’s College London.