48 minute read

Heard Around Campus

AligNiNg MissioNs. Psychology major Mary-Catherine Scarlett, BA ’21, was one of 15 students to receive a stipend from UD’s COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund for a summer internship at either Catholic Charities Dallas or the Society of St. Vincent de Paul (nonprofits whose missions align with UD’s), thanks to a program launched by the Office of Personal Career Development. Read more at udallas.edu/aligning-and-gaining.

eye oN THe Helpers. Eileen Rauh, BA ’21, Alex Ralles Martinez, BA ’21, Maureen Shumay, BA ’21, and Catherine Thelen, BA ’21, spent their summer serving at the Crossroads Community Services (CCS) food pantry in Dallas. Meanwhile, politics major BeLynn Hollers, BA ’21, (above) participated in site briefings at the White House, the Department of State, the British Embassy and the Hong Kong Economic Office — albeit virtually — in her internship with the nonprofit Mil Mujeres Legal Services. New FACes, 2020 ediTioN. UD welcomed 15 new faculty members this academic year. Their knowledge and insights will further enrich student learning in many disciplines, including art, biology, economics, education, English, history, mathematics, philosophy, physics, theology and the library. Read more at udallas.edu/ new-faces-2020.

Advertisement

CANAdiAN pArTNersHip. A new UD partnership will enable the University of Windsor’s Odette School of Business MBA/Master of Management graduates to gain internationally recognized cybersecurity skills and certification all online. Learn more at udallas.edu/canadian-partnership.

In this tumultuous year, we’ve found wise words both within our immediate community and in the larger Catholic and intellectual communities. These words aid us in situating UD’s mission to address the challenges of our world.

Bishop of Brownsville Daniel Flores, BA ’83 MDiv ’87, during “Presidential Conversation Episode 2: Made in God’s Image: A Catholic Vision of Difference and Unity.”

Professor Emerita of English Eileen Gregory, Ph.D., BA ’68, at the Sybil Novinski Scholarship Fund Endowment Ceremony. “One thing [to hope for] is that this sense of estrangement drives people to search for solidarity, sources of unity, something to believe in and belong to, and that this search might be met by some appropriate, proper objects of loyalty and devotion that can bring us together.”

Yuval

Levin,

Ph.D., of the American Enterprise Institute, during “Presidential Conversation Episode 4: E Pluribus Unum: Is American Unity Still Possible?"

BeLynn Hollers, BA ’21, at the Legacy Society Appreciation Event.

Robert P. George, Ph.D., of Princeton University, during “Presidential Conversation Episode 4.”

gRANTEd

The U.S. Air Force awarded UD and Cerium Labs a $500,000 contract to develop a type of silicon nitride seal to extend engine life in gas turbines. Affiliate Research Assistant Professor of Physics will Flanagan, Ph.D., and Associate Professor of Chemistry ellen Steinmiller, Ph.D., are collaborating. Read more at udallas.edu/granted.

Tradition, Heart,Horizons

Discoveries

UD recently celebrated the endowment of three new scholarships and two faculty excellence funds to support the achievement of our students and faculty.

St. John henry newman ScholarShip in philoSophy

Endowed by alumnus Matthew Hejduk, MA '98 PhD '06, and his wife, Julia Hejduk, Ph.D., this scholarship will support a philosophy doctoral student in the Institute of Philosophic Studies. “This is a wonderful opportunity for us to celebrate one of the leading modern Catholic intellectuals,” said President Thomas S. Hibbs, Ph.D., BA ’82 MA ’83, at a ceremony to commemorate the Hejduks’ gift. “St. John Henry Newman speaks from the depth of tradition in a way that seems remarkably contemporary and alive to us today.”

In the Hejduks themselves, you find this combination of the contemporary and the traditional. Hibbs noted that Matthew Hejduk is an actual rocket scientist in addition to having a doctorate in philosophy, while Julia Hejduk, who was a colleague of Hibbs at Baylor University, is a Latin scholar. Julia is also a leader in the pro-life movement, often finding herself in conversation with those on the other side. “She is eager to engage with people in a way that draws them out in a civil manner and sets an example for what we could do a lot better in our culture, particularly our political culture in this moment,” said Hibbs. “I am on many levels grateful to the two of you — for establishing this scholarship, for the friendship we’ve had over the years, for your commitment to the university that I think formed you intellectually in important ways, and for your explicit intention to honor St. John Henry Newman,” he added. Read more at udallas.edu/depth-of-tradition.

Father robert e. maguire, o. ciSt., Faculty excellence FunD For engliSh Dr. richarD p. olenick Faculty excellence FunD For phySicS

"From our conversations with the Clarks, who have shared many wonderful memories, Stacey and I feel like we knew Zach,” said Hibbs as he thanked Trustee J. Barry Clark and his wife, Kathy, at the ceremony honoring their most recent gift to the university in memory of their son Zach. Zach Clark was a member of UD’s Class of 2016 who died tragically in a car accident the summer before his senior year. The Clarks endowed these funds to support faculty excellence in the English Department and Physics Department and to honor the two faculty members for whom they were named, both of whom had a profound influence on Zach. Such endowments are used to provide additional funds to help sustain faculty research so that our faculty can deepen their wisdom, advance knowledge in their fields and provide the very best education to our students.

Hibbs noted what a perfect UD story Zach’s is: A human sciences major, he was deeply engaged in all of his classes and cherished a particular love for the four Literary Tradition classes he took with Maguire as well as his astronomy classes with Olenick. “In the Bible, God asks Solomon what he needs most to become king,” said Olenick. “Solomon answered, ‘Give me an understanding heart.’ All faculty at UD strive for this, I believe, and I am very honored that the Clarks have endowed this fund in my name because it allows us to reach out to our students with understanding hearts.” Read more at udallas.edu/understanding-hearts.

Dr. megan anne Smith rome ScholarShip

Trustee Megan Smith, D.O., BA ’02 MBA ’18, was thinking of future generations of Romers when she created an endowed scholarship for

UD students who need financial assistance to participate in the Rome Program. Smith did so with a blended gift — a cash commitment now and a generous deferred gift included in her estate plans. “I’m particularly thankful for Megan’s leadership in making UD such a priority in her estate plans,” said Vice President for University Advancement Jason Wu Trujillo. “The impact of these blended gifts is tremendous.” A transfer premed biology major and basketball player at UD, Smith wasn’t the “typical” liberal arts major one might most associate with being profoundly affected by the Rome experience, yet Rome and UD remain integral to her life. Smith, as a trustee and physician, has been a member of UD’s COVID-19 task force, helping the university navigate its pandemic response. Her ongoing support of the Rome Program is yet another example of her continuous involvement with the life and mission of UD.

“Megan is one of UD Rome’s most enduring friends and supporters,” wrote Vice President, Dean and Director of the Rome Campus Peter Hatlie, Ph.D. “She is one of those cherished and valued alumni and friends of the university who have supported Rome as it pursues its mission of broadening student horizons and offering them a rich education in the Western and Roman Catholic tradition abroad.”

Read more at udallas.edu/broadening-student-horizons.

Sybil novinSki ScholarShip FunD

“It’s about time,” said Hibbs at the ceremony celebrating the scholarship endowed by Eileen (McPherson ) Meinert, BA ’83, and her husband, David Meinert. “No one is more deserving of a scholarship in her name than Sybil.” Turning to retired University Historian Sybil Novinski, he added, “Eileen and I as students recognized your work. You’re a Renaissance woman and philosopher queen who understands the principles of the good and how to apply them to 18- to 22-year-olds.” Provost Jonathan J. Sanford, Ph.D., recalled how when he first came to UD as Constantin dean and Professor of English Scott Crider, Ph.D., was serving as associate dean, the Novinskis would have the two of them over to their house.

“We greatly benefited from meals and ideas shared in the Novinski home,” he said. Sybil Novinski, wife of Professor Emeritus of Art Lyle Novinski, has been so much more to UD than any of the many titles she held in her 55 or so years of working for the university, serving in roles in Information Services and Admissions and as registrar, associate academic dean, associate provost and university historian — among other things. As Professor Emerita of English Eileen Gregory, Ph.D., BA ’68, put it: “Words of tribute to Sybil lead to images of Sybil at her desk or dining table, working on tasks she didn’t inherit but invented. I have deep and dear memories of her looking me in the eye and telling me the truth.” “Sybil was an angel in my life,” said Meinert. “She was the Holy Spirit’s visible instrument; she opened the door of the University of Dallas for me and my heart to what real education is. This university gave me the foundation of my life, and for this transformation, I’m eternally grateful to Sybil and to UD. I hope others will make their own contributions to the making of essential human discoveries.”

Read more at udallas.edu/philosopher-queen.

To learn more about establishing your own endowed fund, contact Assistant Vice President for Development kris muñoz vetter at kmunozvetter@udallas.edu.

NEVER MORE

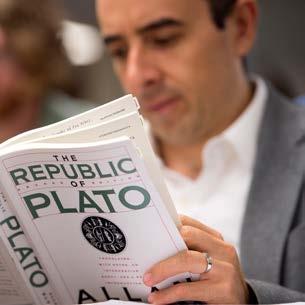

CLASSiCAL eDUCAtiOn At tHe UniVerSitY OF DALLAS TIMELYBy Jonathan J. Sanford, Ph.D. “Plato's Academy” is a Roman mosaic from the first century BCE in Pompeii, now found at the Museo Nazionale Archeologico, Naples.

As alumni may well recall, the most memorable image from Plato’s masterfully wrought Republic is the allegory of the cave, which has filtered into contemporary pop culture through such movies as The Matrix. Yet the cave allegory is not in fact about science fiction, and it is not about our doubting reality. Instead, Plato makes it clear that it is about education and the terrible effects of its absence on the soul.

Plato’s claim is that education is not a matter of uploading new information; it is a matter of transformation, of being led to see things in a different way: Becoming educated requires seeing the truth for oneself. Becoming educated requires the orientation of one’s entire self toward the source of all that is good, true and beautiful. These two lessons lie at the heart of a University of Dallas education. The same two lessons serve as basic pillars in every education that can be described as classical. In this way, we are ideally positioned to help shape the burgeoning classical education movement. What does it mean to see the truth for oneself? One of the dangers of our age is that we can think that the possession of information is the same thing as knowledge. It is not. Computer

What is it that education endeavors to enable us to see? The truth of the good which is the aim of all things:

"this instrument cannot be turned around from that which is coming into being without turning the whole soul until it is able to study that which is and the brightest thing that is, namely, the one we call the good." hard drives also store information. The facility with which we have learned to code and pass information from one device to another, and so from one person to another, can deceive us into thinking that learning and knowing are relatively simple affairs. But learning always requires a real encounter with an object, indeed a union with an object, and that union takes hard work, intellectual humility and a receptivity to things as they really are rather than how we imagine them. We need to be mastered by what we are learning if we are to become disciplined thinkers — masters — of what we study. There are no shortcuts in this endeavor — this quest — to know things as they really are and so to become educated. It requires careful study of original sources in the great works of literature, history, mathematics, the sciences, philosophy, theology and the other disciplines. It requires hands-on work in laboratories, theaters, performance halls, boardrooms, art studios and outings in and around Rome. It requires mastering the Socratic method under the careful tutelage of professors, which includes learning to consider things from multiple points of view, cultivating the habit of articulating and appreciating opposing arguments, and at the same time honing one’s powers of argumentation so that one can come to see the truth of any matter. Learning to see things for oneself requires each of these things and more, and the University of Dallas carefully cultivates the intellectual virtues at issue in this vital work. What does it mean to orient one’s whole self to the good, true and beautiful? We are not brains in vats designed to feed the Matrix. We are not even minds in bodies. We humans are integrated

wholes with minds, brains, passions, senses and bodies. Because of this, we cannot hope to cultivate virtues of the mind without the virtues of character. We have to throw the whole of ourselves, not just our minds, into the effort to learn. Therefore, finding ways to encourage our students to embrace more deeply and cultivate more intentionally the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance cannot be an afterthought; it is central to the work we do. These virtues are enriched, as well, by the theological virtues of faith, hope and charity, and so finding ways to provide opportunities for growth in those Christian virtues is central to the work of our Catholic university. Our principal efforts are aimed at providing such an education, and it is through those efforts that we serve as this model, but we are not content merely to serve as a model. As both the Mission and the university’s new strategic plan make evident in holding up as one of our chief goals finding ways to serve Church and country, the responsibility to educate includes educating our students toward faithful witness and responsible citizenship. There are countless examples of ways in which graduates of our undergraduate programs live out such lives, bringing their UD education to bear in ministry, civic service, legal practice, medicine, education, business and more. Our graduates find themselves in every walk of life,

We live, we know, we love as wholes, and so the education of the whole person is at the very heart of our efforts.

These are the efforts of a genuine liberal arts education, one that aims to liberate our students from both their own ignorance and their tendencies to be diverted from worthy goals by their passions, so that they might be liberated to serve out their call to live meaningful lives enriching themselves, their families, their communities, their countries and their churches. At its best, the classical education movement growing rapidly in the United States and beyond endeavors to do the same. Our witness to these ends, and our proven success in achieving them, has made of us a model others are striving to imitate. where their UD education serves not as a distant memory or a personal affair, but as a living source for lives lived as forces of good for others. In this way, their liberal education, their classical education, is constantly put to the service of cultural renewal.

On the graduate level, these same principles apply, but with a heightened focus on professional preparation. This is the case whatever the discipline our graduate students find themselves in, but it is especially the case in the ways in which we are forming the current and future teachers of every level of education. In our M.A. in Classical Education, for instance, we provide both the pedagogical and substantive resources current and future teachers within K-12 classical education schools need to serve future generations of students well. In addition, for a growing number of current classical education K-12 schools, as well as schools looking to become classical education schools, we are providing both teacher training and curricula that they can use in their classrooms. At the doctoral level, particularly through the unique liberal arts core curriculum of our Institute of Philosophic Studies, we form our students to become university professors who will eventually shape the lives of future undergraduate and graduate students at other institutions. Everywhere one turns, one sees evidence that we are living in turbulent and troubling times. We continue to suffer from a pandemic, economic hardships, social unrest, incivility in our public forums and a crisis of vibrant faith life. But the principles we hold dearest — that our education leads students to grasp the truth and to orient their entire lives by the highest goods — are alive and well, both on campus and in all those arenas where a UD education reaches through our graduates and their work. Our principles are timeless, and our work has never been more timely.

Provost Sanford joined the University of Dallas as dean of Constantin College in 2015. Elevated to provost in 2018, he is currently writing a book on virtue and education.

The IPS core curriculum engages fundamental texts, principles and issues that are formative of the literary, philosophical and political strains in the Western intellectual tradition. It comprises six courses taken by all Ph.D. students in all three concentrations: literature, philosophy and politics.

FUTURE EDUCATION THE OF

Ud’S ClASSICAl MOdEl pOISEd TO SHApE THE NExT gENERATION

estled in the center of Mount St. Michael Catholic School (MSMCS) resides an outdoor oasis. Near the main entrance is the first of two outdoor classrooms, where a second-grader writes in his nature journal before jolting up, explaining, “We’re studying rocks!”

A longtime campus tenant of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity and Refuge, the private Catholic Montessori school partnered with the University of Dallas in 2019 to help train its teachers in classical pedagogy. Now also piloting the UD Classical Humanities curriculum for its sixth-graders, MSMCS is expanding into subjects that include even more outside “green time” surrounded by sprawling undeveloped terrain on the outskirts of southwestern Dallas.

“Our students love learning outside, and are building their attention skills while also forming a closer connection with the world around them,” said Librarian Kathy

Fiegenschue, BS ’76, a longtime teacher and parent. “As children reap the harvest for others, lessons of generosity are planted in their hearts.”

Such innovative learning environments are not only possible, but encouraged, within a classical education model. With the transformation of classrooms, teachers, parents, students and even administrators can agree: The need for fresh air requires more than the normal scheduled recess. Moreover, unlike traditional schools, a classical K-12 education orients its learners to discovering truth and learning virtues by studying the great works of Western civilization. UD, already a leading institution for classical learning at the university level, is now equipping teachers and parents of students from kindergarten through high school with educational resources and training as more schools transition to a classical style of learning. In 2019, UD launched a pilot program for the classical K-12 curriculum that is currently being deployed in a dozen schools nationwide, including five schools in Texas.

AESOP’S FABLES

It’s the fifth day of professional development at St. Maria Goretti Catholic School in East Arlington under the guiding instruction of Adrienne Freas, a classical education adviser in UD’s Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts. A major focus of one of the lessons is character-building and teaching moral virtues with open readings taken from a classic illustrated edition of Aesop’s Fables.

Inside the auditorium, three dozen or so classical educators have gathered to expand their teaching palette with a daylong schedule of professional development. After reading “The Bear and the Bees,” everyone is directed to propose one sentence describing the central lesson (moral) of the fable; readers can often elicit more than one moral. “The lesson was about keeping your calm and not losing your temper,” one teacher suggests. Another replies, “Don’t make assumptions.”

“As the instructor, I would write each of the students’ proposed morals on the whiteboard,” explains Freas. “Then we can help the students think and choose for themselves. They can vote, discuss which one they like best and why, or even have a full debate reflecting back to the text to prove their argument. Younger students can copy their favorite sentence into their copy book.”

Ample Socratic discourse centered around “The Bear and the Bees” helps reinforce the underlying moral lesson: It is wiser to bear a single injury in silence than to provoke a thousand by flying into a rage.

St. Maria Goretti, located in the Diocese of Fort Worth, was in its first year of transitioning to a classical model when it reached out to UD, seeking curricular support and professional development for its teachers. “Our school system has been committed to instructing all new teachers about classical education, philosophically defending the reasons for teaching the good, the true and the beautiful,” explained Lara Pennel, BA ’89, a middle school literature and religion teacher.

Also in attendance for the training are a handful of instructors and parents from St. Isidore Academy, a hybrid Catholic school situated on a 100-acre farm in Greenville, Texas, named Farm2Cook Pastures. St. Isidore Academy partnered with UD for similar curricular resources and classical training, accessible not only for teachers but also parents, complementing the school’s unique family focus on Catholic formation. A small group of local Catholic families founded St. Isidore Academy a few years ago to help families home-school children while inspiring their faith and supporting their intellectual development. This included Director of Education and Operations Kristina Holleman, BA ’93, who tutors fifth and sixth grade as well as high school literature and English. Board member Brandon Barker, MTS ’14, director of evangelization and discipleship at St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in Dallas, also leads St. Isidore’s weekly high school theology discussions.

The home-based farm school meets a few days a week. Following morning prayer at St. Isidore Academy, students lend a hand with the chores: feeding the chickens and goats, collecting eggs, milking the cow, grooming and working the horses, and tending to the garden. Outdoor nature lessons provide an engaging hands-on science curriculum; the community-first approach enables the farm to supply meat and dairy to Dallas-area grocers and restaurants.

“We’re in conversations with charter and home schools from all over the country; headmasters, teachers and even home-school parents are reaching out to us,” said Freas. Nearly a dozen schools are already piloting UD’s K-5 Living Latin curriculum in development by Affiliate Assistant Professor of Modern Languages Laura eidt, Ph.D.

While about 150 Catholic schools nationwide shuttered doors in 2020 due to exacerbated financial strain, according to a 2020 New York Times article, transforming Catholic schools, home schools and charter schools into the classical model is gaining popularity and may be the means of their survival.

At the same time, the Times article continues, bygone Catholic communities centered around these closed schools are left with an almost indescribable, profound loss: “the abrupt disappearance of spaces that long served as focal points for personal relationships and family ties.” External struggles, including the current pandemic, are challenging communities to reimagine education and consider nontraditional and classical models. Such was the case with Nyansa Classical Community, an after-school outreach program primarily serving inner-city students of New Orleans, Louisiana, another group piloting the UD classical curriculum. “Engaging students via Zoom is a challenge,” remarked one Nyansa teacher near the conclusion of a Monday night Zoom lesson taught by Freas that focused on narration and virtues. Helping encourage greater student-instructor interaction, Freas offered the instructors a series of exercises based on Aesop’s Fables’ “The Boys and the Frogs.”

FARM TO FABLE

Back on the campus of MSMCS, the students have come to love their outdoor Fridays with the launch of the school’s Farm to Fable program this fall. “Tomorrow, they’ll come out and learn how to lead him,” said one teacher of the school’s new outdoor barn tenant, Fuego the horse.

“MSMCS knew our pilot would fit with their mission because our humanities curriculum has nature studies built into it,” explained Freas. “The lesson is about Creation — it’s the story of the Bible.”

This sort of curriculum, encompassing nature, physical work and practical skills, classical literature, tradition and religion, is exactly the whole-body, whole-life education that UD has always promoted, now expanding into our larger community.

CLASSICAL EDUCATION

wIll IT ENdURE?

By Jeff Lehman, MA ’99 PhD ’02

s the momentum of the classical education movement continues to grow both in the United States and abroad, one might wonder: 1) what sets classical education apart from other current forms of pedagogy; and 2) whether this movement is simply a passing educational fad or one that is here to stay, promoting an effective pedagogy established on sound principles. In other words, does classical education have the wherewithal needed to serve us well in our present troubled times and to prepare us for whatever the future may hold?

In the past few decades, the classical education movement has grown from very humble beginnings to enrich and to inform the educational philosophy, teaching methods and curricula of a wide variety of K-12 academic institutions — public and private, religious and secular, and newly founded and established schools desiring to “convert” to the classical model.

To see why the movement has enjoyed such marked success, we should first consider the question: What is “classical” education? Put in simplest terms, classical education is an education for freedom. That is why for most of the Western tradition from its origins to the present day, the majority of authors have used the term liberal education (from the Latin liber, free) to denote what is typically called classical education in our time. A liberal education frees the one who pursues it with an active, engaged mind and an open, courageous heart.

Any reasonable practice of education is grounded in a philosophy of education, and central to any philosophy of education is a clearly articulated understanding of the human person. According to the greatest thinkers who have written on liberal education in the Greco-Roman, JudeoChristian tradition, human beings are created by God to know themselves, the created order and their Creator. They are endowed with natural faculties that empower them — to the extent each is able — to grasp the true, the good and the beautiful. Pace the proponents of many “progressive” forms of education, human nature is not something that can be radically transformed or arbitrarily reinvented in light of novel philosophies of education proffered by educational “experts.” Instead, human beings have a stable, enduring nature with certain definite potentials that must be actualized (through moral, intellectual and theological virtues) in order to achieve true human flourishing. humane letters, mathematics, natural science and philosophy, and culminating in the study

Given this description, it is not difficult to see that the roots of classical education are anchored deep in the Western tradition. In fact, what the classical education movement has uncovered in the past few decades is nothing other than the “Great Tradition” of Western education, a tradition that has sustained Western civilization for millennia now, and one that is profoundly indebted to some of the greatest minds in the Catholic Church.

Thus, for UD to embrace classical education is not to move out in a new direction; instead, it is to remain true to its own founding and to the incredible riches of the Catholic intellectual and spiritual tradition that has nourished our institution from the beginning. One of the reasons UD has so quickly moved to the forefront in the classical education movement is that we have been teaching and learning within this tradition since before the classical education movement began.

Clearly, then, the classical education movement and the longstanding tradition of the

By engaging the fullness of human experience across all the disciplines, seeking to integrate all study within the unified pursuit of the good, the true and the beautiful, the enduring tradition of the liberal arts and liberal education offers the most time-tested, dynamic and promising hope for education in

Professor of Humanities

A liberal education frees the one who pursues it with an active, Jeff Lehman is the graduate director of the Classical engaged mind and an open, courageous heart. Education concentration in the Braniff Graduate School

of Liberal Arts Humanities program and director of the

The human intellect by nature hungers for liberal arts and liberal education from which Arts of Liberty Project. knowledge of the truth; it is what nourishes it sprung are anything but a passing fad. This the mind, as food nourishes the body. Since movement is simply a current manifestation nature does nothing in vain, the very possibil- of a fruitful educational tradition that has ity of education is based upon the confidence stood the test of time, weathering economic, we can have of coming to know the truth. social and political crises throughout the Simply knowing the truth is not sufficient, of centuries. This tradition has been sustained course. The one who discovers the way things by the works of such playwrights as Sophare comes to recognize the vital connection ocles and william Shakespeare; such between acknowledging the truth with one’s epic poets as Dante Alighieri and John intellect and embracing the good through Milton; such historians as thucydides and the free choice of one’s will. Knowing the Henry Adams; such statesmen and political truth, willing the good and apprehending leaders as St. thomas More and Martin the beautiful lead to true human happiness. Luther King Jr.; such philosophers as Plato In the Catholic tradition, all this is possible and immanuel Kant; and such theologians only through a willing cooperation of human as St. Augustine of Hippo, St. thomas nature with divine grace. Aquinas and St. John Henry newman.

Summing up, then, we could describe It is certainly here to stay. And given its liberal education as the pursuit of wisdom remarkable ability to foster charitable, irenic through a cultivation of intellectual virtue dialogue among those with very different and an encouragement of moral virtue by perspectives, it is a worthy model for our means of a rich and ordered course of study, times of deep division and (all-too-often) grounded in the liberal arts, ascending through uncivil discourse.

the future. of theology, yielding informed self-rule and a The human intellect by nature hungers for knowledge of the well-ordered understanding of human nature, the cosmos and God. truth; it is what nourishes the mind, as food nourishes the body.

OLD IS NEW

RETURNINg CATHOlIC SCHOOlS TO A ClASSICAl MOdEl

By Matt Post, PhD ’15

he University of Dallas is presently piloting a K-12 curriculum and professional development for Catholic schools transitioning to a classical model of education. UD’s faculty have long served teachers and schools of all kinds, educating current and aspiring teachers as well as contributing to curricular projects and professional development. That said, the development of a full-blown K-12 curriculum is new territory for the university. What has inspired us to serve our community in this way?

Across the country, more and more K-12 schools and home-schoolers are turning to what has come to be called “classical education,” but which has traditionally been called “liberal education.” Many are attracted to its unabashed stance that human beings, however fallible, may grasp some degree of truth not just in scientific disciplines, but also when it comes to aesthetic and especially moral questions. Others are attracted to its cultivation of humility and critical thinking through informed, thoughtful and open-ended discussion, inspired especially by Plato’s Socratic dialogues. And still others are attracted to its emphasis on the human being as a whole, as fundamentally rational and free, with a view to the flourishing of individuals and communities. Liberal education seeks to foster excellence in all its forms.

If this sounds like a lot, that’s because it is, but the Western tradition offers an inexhaustible storehouse of wisdom in negotiating the important but difficult dilemmas that confront us as human beings — drawing from Hebrew Scripture, the Greek and Roman authors, and the Jewish and Muslim thinkers who engaged with them, as well as from a profound desire to engage with other traditions wherever they may be found. This tradition also draws great strength from the Gospels, from St. Augustine and St. thomas Aquinas, and from the monastic schools, cathedral schools and universities that have flourished under the Catholic Church.

This tradition is catholic in every sense: It is for all, pursues what is universal and has been fostered by the Catholic Church.

Leaders in K-12 Catholic education have approached UD for help in transitioning schools to a classical model. Thanks to its outstanding Core Curriculum and graduate programs in K-12 classical teacher formation, UD is well-positioned to serve the community in this way, complementing the work of others, such as the Institute for Catholic Liberal Education, home-schooling author Laura Berquist and St. Jerome Academy.

Our K-12 classical Catholic curriculum is logo-centric. Its animating center is Christ, the Word (logos), as well as Aristotle’s understanding of humans as the living beings possessed of reason (logos). It is ordered according to the liberal arts of the Trivium (grammar, logic and rhetoric) and the Quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy). The Trivium teaches us how words can reveal the innermost depths of human nature and inspire us to virtue, and the Quadrivium teaches us how numbers can reveal the order of nature and the beauty of harmony.

At the heart of the curriculum rests the ancient pedagogical strategy of narration, the ability to re-articulate, explain, question and debate what we learn from Great Works. As could be a transformative thing for K-8. Narration is the way we can weave together all of the different parts of the Trivium and the mode through which we come to understand it … It’s so new and revolutionary that it will be hard at first for people to even grasp it.”

Most importantly, the curriculum draws its strength from the deep Catholic tradition of education, cultivating the habits that sustain intellectual and moral virtue, inspiring wonder and rigor of inquiry, and remaining attentive to our dignity as created in the image of God. At all times, it seeks to show how we may serve our friends, our community and God, respecting our sacred responsibility to minister to God’s created order.

Our curriculum and professional development team is led by Adrienne Freas, who has 20 years of experience in classical education as a home-schooler, classroom teacher, teacher coach and curriculum writer. She is joined by robin Johnston, lead teacher trainer at Mount St. Michael Catholic School, and Alexis Mausolf, who has served as a teacher at The Highlands School and as a writer and editor on curriculum for the Theology of the Body Evangelization Team.

The team is supported by several UD faculty, all of whom have taught K-12 classical teachers in our graduate programs, including Laura eidt, Ph.D., a classical home-schooler; Gregory Roper, whose book The Writer’s Workshop is a mainstay in classical schools across the country; John Peterson, MA ’19 PhD ’19, a former classical high school teacher; robert Hochberg, Ph.D., whose insight guides our integration of STEM and humanities; Bill Frank, Ph.D., whose many years serving UD informs our vision; and Jeffrey Lehman, MA ’99 PhD ’02, a leading authority in developing classical teacher formation programs and resources, whose

Gregory roper, Ph.D., BA ’84, notes, “This

guidance ensures that our work is aligned with the Church’s teachings and the University of Dallas mission.

Our pilot project currently includes the Austin and Fort Worth dioceses, with five schools piloting the K-6 Humanities curriculum (including UD’s lab school Bishop Louis Reicher) and 10 schools piloting the K-2 Latin curriculum. In the coming years, we will add subjects and grades, until every subject and grade is covered. Moreover, the team is working on a pedagogy handbook, Dancing Through the Trivium, which is being piloted by several schools, including Nyansa Classical Community, which serves underprivileged students in Louisiana.

What especially distinguishes this curriculum is its focus on schools in transition, early childhood education and the liberal arts. As Yoshiaki nakazawa, Ph.D., our newest colleague in Education, explains, “Dancing Through the Trivium provides an invaluable framework and metaphor for understanding the complexity and beauty of education … While there is a plethora of books that discuss traditional and progressive forms of education, there is too little written on the practical deliverance of classical education for the young child.”

At a time when many schools, including Catholic schools, are seeing dropping enrollments, our partner schools are seeing enrollment increases in response to their transition to a classical model (e.g., St. Joseph Classical Academy in Killeen, Texas, has grown 60% since adopting UD’s curriculum).

As for the benefits, they’re articulated well by Kristina Holleman, BA ’93, founder of St. Isidore Academy in Greenville, Texas: “What the UD team has put together is tremendous. The scope and sequence is a rich and multilayered combination of living texts … that presents an abundant feast of goodness, truth and beauty … Every [professional development] session has been immensely fruitful, and we have all learned practical methods for implementing a classical pedagogy. Our entire team is unified, excited and now equipped to embrace a genuinely classical approach to educating the youth entrusted to us. We truly believe that this curriculum will help us in our mission to form young people who love wisdom and seek truth, and who will go forward to impact our culture with the love of Christ.”

Matt Post is associate dean of the Braniff Graduate School and assistant professor of humanities. Post received a Bachelor of Humanities and Master of Arts from Carleton University before earning a doctorate in politics at UD.

SOURCES WISDOM PASSING ON THE OF HUMAN

nstitute of Philosophic Studies doctoral candidate Jenny Fast, MA ’14, switched from district-run public to private classical school in seventh grade, and thereby stumbled into a new world. She and her husband, Francis Fast, MA ’13, both received their bachelor’s degrees from Thomas Aquinas College in California, where they studied under a few people who helped lead them toward UD for graduate studies, including Professor of Humanities and Graduate Director of Classical Education Jeff Lehman, MA ’99 PhD ’02, and Associate Professor of Philosophy Matthew walz, Ph.D., MBA ’19.

“UD prepares you for a certain kind of life as an educator,” explained Jenny Fast. “I was happy to find the university because I had wanted to give back to the kind of education I’d received, and those professors recommended UD because of the habits of the intellectual life it seeks to instill in you and the way in which it positions you to extend that life to others.”

Francis Fast, now the assistant headmaster at Founders Classical Academy of Lewisville, has worked in administrative positions at Great Hearts Academies as well, including supervising Great Hearts teachers in UD’s classical education program, working closely with Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts Associate Dean and Assistant Professor of Humanities Matt Post, PhD ’15, and with Lehman. He has also taught at Founders, as has Jenny.

“We’re grateful for the ways the University of Dallas has prepared us to serve in the world of liberal education, both in K-12 and in higher education,” said Jenny, who teaches as an adjunct at UD as she works to finish her dissertation here, striving at the same time to establish her career in the world as a whole — indeed, to get a feel for the world as a whole.

When the Fasts first moved to Texas in 2010 to enter UD’s Ph.D. program, there were no public charter classical schools in North Texas and very few in the country. When Founders, the first Barney Charter School in the nation, opened in Lewisville in 2012, an email, looking for teachers, went out to all Braniff students. Jenny interviewed and was surprised by the scope of the organization, since her classical education experience had been at a small school. Founders started out with around 400 students at the Lewisville location and quickly grew to full capacity at just under 1,000 students.

“Initially, I was just looking to replace the online teaching I’d been doing to support myself,” said Jenny. “But in starting at Founders, we found ourselves caught up in a much bigger project.

“Becoming involved in classical charter school education has given me the opportunity to build a much broader community than graduate school often gives you — I’ve worked with people from elementary to the graduate level,” she added. “Even at schools across the country, there’s this recognition of common texts, connections, pursuits — I know it’s helped me to have a richer, more connected life than I would've had otherwise.”

“It’s also about passing on a vision of what it means to be human and ensuring that some of the greatest works of literature, philosophy and mathematics are actually part of the experience of people on the street,” explained Francis.

All students who go through a classical ed curriculum, for example, have read the Iliad and Paradise Lost, which typically are not at the heart of public school culture in the way they tend to be in a classical school.

“There’s something very different, very exciting and refreshing about being part of a movement where you have thousands of colleagues teaching thousands of kids the same texts,” said Francis.

In Arizona, there are now over 20 Great Hearts schools, and driving around, Francis says that you frequently see Great Hearts bumper stickers.

“Every time you see one, it means you’re driving next to someone who has read or is going to read the Iliad,” he said. “The same thing is happening now in North Texas with the Founders schools — there’s a whole network of families reading the same curriculum. There’s a sense of trying to build up a common civic life, where otherwise people might have no common interests or experiences.

“I also want to mention the vitality of the movement,” added Francis. “With a lot of grad students, there’s anxiety about their career; in higher ed, for every job, there will be many applicants, and you’re trying to find that one spot compatible with what you have to offer. Classical ed, though, is not a contracting field — it’s exploding. It’s offering something that parents are very hungry for. Being in classical ed is being part of an ever-expanding community pulling more and more people in. There’s vibrancy and growth, and teachers are in high demand.”

The Fasts also pointed out that UD prepares these teachers in exactly the way not only suited for classical charter schools, but district public schools as well.

“From a hiring standpoint, UD’s Core and the broad, cross-disciplinary curricular formation is perfect for a teacher and exactly what people need to be prepared to teach,” said Francis. “One thing all schools look for in their teachers is the ability to make links in a cross-disciplinary way. Kids need that, but teachers can’t provide it if they don’t have deep knowledge outside of one discipline."

“Ultimately, we want to see wise and fulfilled students,” added Jenny. “The goal is to create people of all walks of life who have a strong sense of what it means to be human and all the ways you CAN be human, and be able to enter into conversation with anyone they meet. The goal of classical education isn’t a goal that ends in schools.”

“To the extent we’re successful, it’s because we very consciously hold a tradition of wisdom up to ourselves as the thing we’re trying to give the students,” concluded Francis. “We want to take the wisdom of the ages and pass it on to them. This means asking: What wisdom do students need to have access to? There’s a lot of conviction behind this initiative — that educational renewal is not simply about trying to tweak teacher training or tweak curriculum, but about having wisdom to pass on. We’re trying to find the sources of human wisdom that students need and pass these on to them.”

ust down the road from the University of Dallas, I make my small commute each day to teach my lovely seventh- and eighth-graders at Travis Middle School in Irving. I studied history at the University of Dallas, knowing I wanted to teach at the secondary level. What I did not yet know was where I was going to teach! My UD education prepared me in numerous ways to pursue truth, wisdom and virtue, and I knew I wanted to share these wonderful gifts with students of my own. After completing my student teaching at Travis during my senior year, I decided I wanted to stay and teach where I began my career.

By Maria Labus, BA '19

Being a history teacher allows me to be so versatile in the classroom. My students are constantly asking questions and trying to understand large concepts and how they relate to their lives. Because of my classical education, I am able to provide a broader view for these students. There have been many lessons in which I’ve included pictures from my Rome semester. These pictures create a sense of wonder and adventure for my students. It is always a great discussion starter, and they come up with amazing questions. They realize that a school just down the road can provide these experiences for them. It is within their grasp! The style in which we were educated allowed for our wonder to be guided and molded to our own virtues. We learned how to think for ourselves through careful study and analysis. I wanted to carry over this tradition into my own classroom. Typically, many think of a public school as rows of desks with textbooks out. The teachers stand at the front of the room and give a lesson as the students begrudgingly take notes. I did not want to fall into that stringent stereotype. My classroom is not one where silence is often present. Conversations carry most of the lessons; I do not do the majority of the speaking. I present a question that the students must respond to, according to their own resources and discoveries.

A BROADER

They learn from each other; they learn how to think about questions through inquiry, reading, writing and collaboration. It really is an amazing process to see from a teacher’s perspective. Their sense of wonder and imagination is like none other at the middle school level! Because I allow the students to speak their minds and ask questions, they are active and engaged learners. They come into my room listening to music from a historical era; they open their notes to analyze a quote and write what it means to them. They know that their education is in their hands; it is all student-centered. This is how I learned at UD, and this is how my students are going to learn. I love being so close to the university because my students know what and where it is! Last fall, some of my students took a field trip to UD. I had taken the day off from work since I had my oral comps for a grad class during the day. My students saw me sitting in the Cap Bar, last-minute editing my speech, and I don’t think I have ever seen them so excited to see me outside the classroom! The teachers who took them on the field trip asked the students what their favorite part of the trip was. Many responded, “Seeing Ms. Labus in school!” Moments like those, though rare, make things like attending a university seem attainable and real for the kids. They see their role models like us teachers pursuing education and loving what we do. They love that I still go to school because I can still relate to them as a student (what will I do when I graduate in the spring?!). Another touch of UD that I incorporate into my classroom is the program UD Reads. Dr. Carmen Newstreet and Dean Cherie Hohertz started this program in an effort to create a community of readers across the Dallas/Fort Worth area. They have partnered with public schools such as Travis, Catholic schools, charter schools and even home-school groups. Their initiative extends the UD community past the beloved bubble! There are many Irving ISD teachers who partake in this program. Erin Begle is another UD alumna who teaches right across from Travis at MacArthur High; she helps write the curriculum for all of us who participate in the program. It is such a great program to push kids to read things outside of our normal curriculum, once again revealing to them a sense of wonder and a growing passion to find truth, wisdom and virtue.

Classical education and public education do not have to be seen as stark opposites. They work together harmoniously to create critical thinkers. What else is education for if it isn’t to create lifelong learners? We as humans crave experiences that drive us to become more well-rounded individuals. Through experiences, we are able to relate to others and their experiences. It may be hard to physically go out and experience the world for a middle schooler at a Title I public school, but if I can share the possibilities they have through hard work and determination, then that is my mission. Each child has the potential to pursue truth, wisdom and virtue. Every teacher has the ability to plant the seeds and create a path for students to get there. The University of Dallas mission and vision make it clear that we are meant to share the beauty of education and continue our lifelong pursuit in the hopes of raising a large community of independent thinkers.

CORE dISCIplINE

You Can Do WHAT With a Psychology Degree?

Trustee Julie weber, BA ’91, combined her UD psychology degree with a passion for people to become the chief and VP of the People Office at Southwest Airlines. In this interview, Weber reflects back on the challenges of pursuing plans to be a licensed counselor, the change of course that led her to human resources and the benefits of a UD education along the way.

How did you get into HR?

After graduating from UD, I went to Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio for my master’s degree in counseling psychology in ’93. My plans were to get a job underneath a Ph.D., so I could get the needed hours for a counseling license. But with the economy at the time, I could not get a paying job that would allow me to do that, and I had come out of undergraduate and graduate school with a lot of student debt. While struggling to find a job, I reached out to Dr. Churchill from UD and asked for advice, and he suggested human resources. I literally hung up the phone and thought, “OK, I’m going to figure out finding a job in human resources.” Even though I’d just gotten out of graduate school, I called one of my undergraduate professors, which speaks to the community UD creates and how you can really use the professors as counselors. That phone call was monumental for me, and Dr. Churchill probably doesn’t even remember it. I typed up a bunch of resumes, checked the Sunday paper looking for job openings and got a job in Dallas at a staffing agency as a recruiter. And you know, I found something I really loved.

How has your UD education helped you throughout your career?

UD’s education teaches you several important skills; one is critical thinking, which is something that has helped me throughout my entire career. Secondly, UD taught me how to write: I never realized how important that would be for me as an HR professional. Thirdly, I really enjoyed the small, intimate classrooms where you could really have strong conversations and debate with classmates. When you get into business, the ability to have a diverse group of people who are able to debate and dialogue about a situation in order to arrive at a solution is a critical skill. You were recently named on Comparablyʼs list of ʻ50 Leaders Creating Positive Change.ʼ How would you describe your leadership style or philosophy?

Even in that award, it’s not me – it’s the team. There are a lot of people involved in making Southwest Airlines what it is. My leadership philosophy is one of servant leadership. I serve the People Department and the employees of Southwest, and I’m here to help them shine. People become leaders because they were very good at what they did as individual contributors and were moved to leadership roles. What I think leaders need to do is accept that they’re no longer the superstars; their new job is to create superstars. My job is to help others develop, launch careers and help them grow. I think one of the best compliments a leader can have is seeing someone who worked for them surpass them.

What is the most challenging part about your job?

I think the most challenging part of human resources, no pun intended, is the people. It’s not one size fits all. You always have to think about the best thing to do for the company, but at the same time you’re dealing with individuals. It’s a balance, and that’s part of what can be difficult. I think this is where competencies like diplomacy, objectivity, patience and empathy are paramount. In considering phenomenology, which we learned all about in UD psychology, two people could have the exact same thing happen to them but experience it very differently. Phenomenological theory is one of the ways my psychology degree has really helped me when sorting through the challenges that come with dealing with large and diverse groups of people.