THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY of FLORIDA COLLEGE of LIBERAL ARTS and SCIENCES

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

The herons can fly. The orchards can bloom. The waters can fall. The streams can shine in the sun. These hills can abide forever. And we can say of the Florida we love, as was said so long ago, ‘a more beautiful country can scarcely be imagined.’

But first we must dream. We must dream the great dream of the once and future Florida. And we must make that dream come true.

— FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS, JANUARY 2, 1979

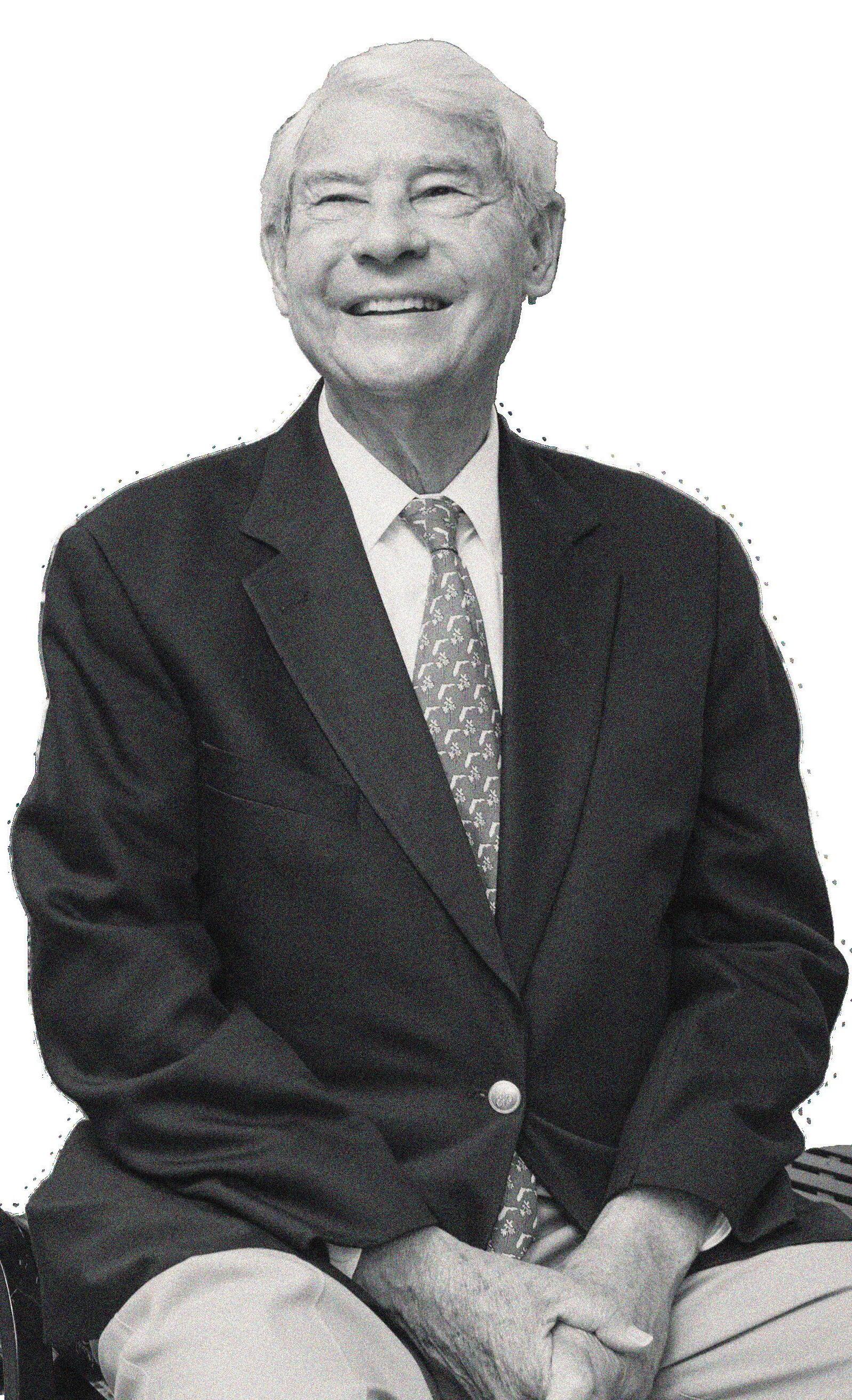

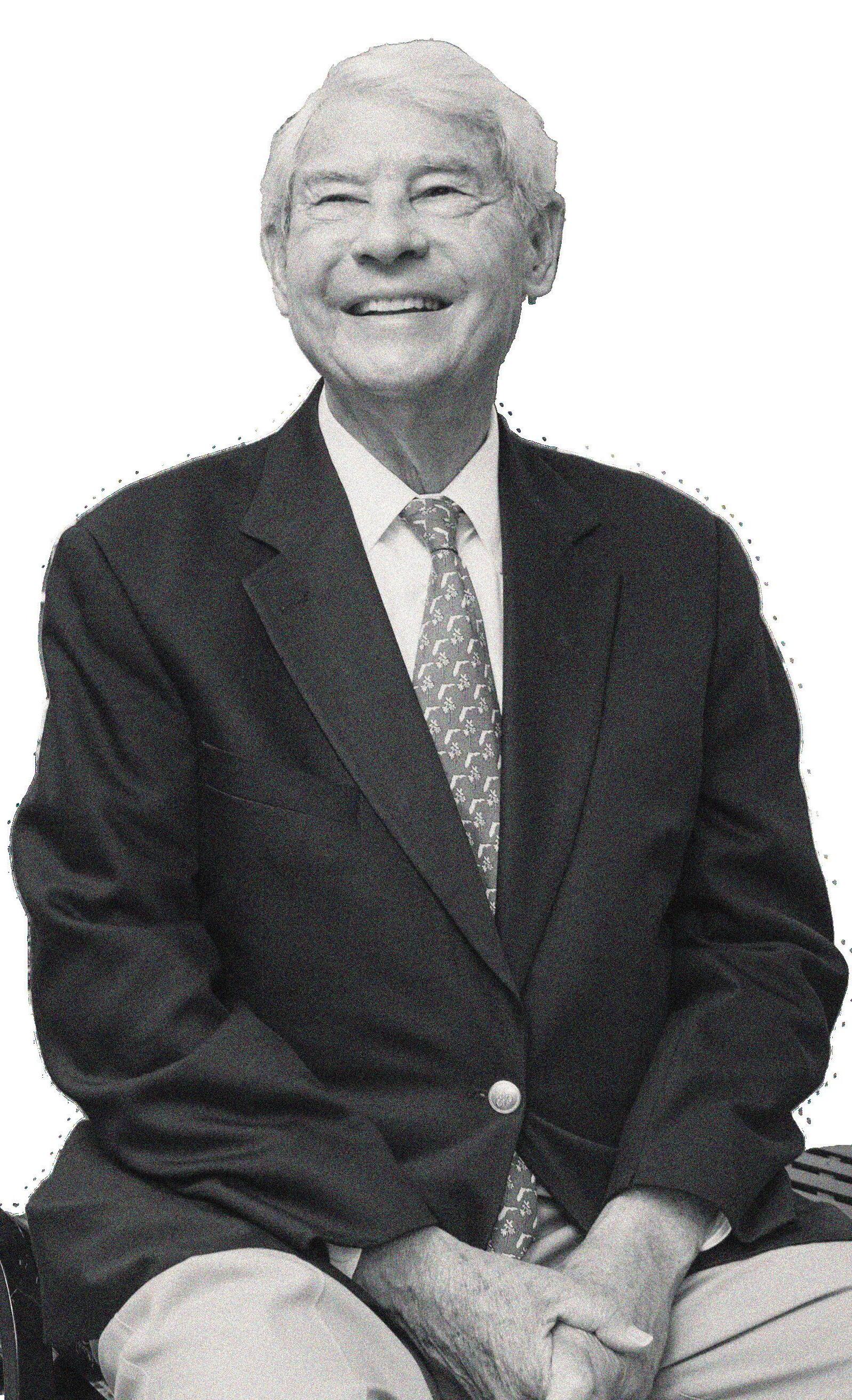

In memoriam

GOV. BOB GRAHAM (1936 - 2024)

Marshland. @ ECrafts/Adobe

Stock. Photo courtesy of the Bob Graham Center.

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

Ytori is published twice a year by the University of Florida College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“Ytori” means “alligator” in the language of the Timucua, the native inhabitants of north-central and northeastern Florida.

STAFF

DAVID E. RICHARDSON, Dean

STEVE EVANS, Executive Director of Advancement

MEREDITH PALMBERG, Senior Director of Strategic Engagement

DOUGLAS RAY, Associate Director of Communications

LAUREN BARNETT, Editor-in-Chief

BRIAN SMITH, Writer

EMMA BARRETT, Editorial Assistant

ALI RADKE, Proofreader

KATHLEEN MARTIN, Art Director

MICHEL THOMAS, Multimedia Specialist

© 2024 by the University of Florida College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or duplicated without prior permission of the editor. University of Florida College of Liberal Arts and Sciences is an equal access/equal opportunity university.

HAVE A STORY IDEA OR WANT TO GET IN TOUCH?

ADDRESS

Ytori, University of Florida College of Liberal Arts and Sciences 2014 Turlington Hall PO Box 117300 Gainesville, FL 32611

EMAIL clas-news@ufl.edu WEBSITE news.clas.ufl.edu

@UF.CLAS @UF_CLAS @UF_CLAS

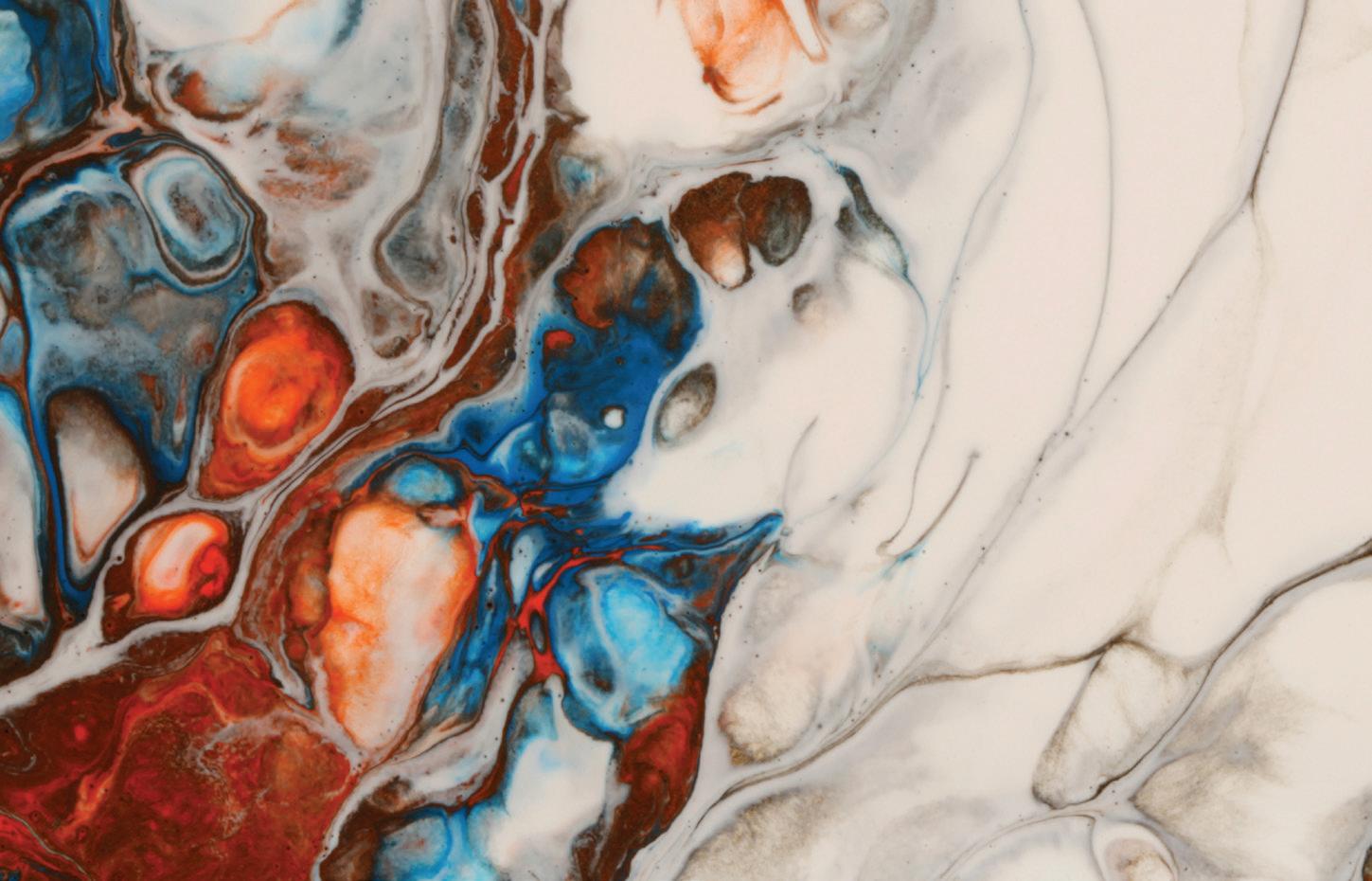

ON THE COVER

The university’s connection to water comes to life as abstract water elements double as alligator skin. Design by Kathleen Martin. Marble Texture. © Liliia/Adobe Stock.

Ytori Magazine

| COVER STORY Waterscapes Geographers lead the way toward water solutions 20 Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

SPRING/SUMMER 2024 Contents

| CONNECT 32 Glacial Features A documentary film spotlights scientists on a Greenland expedition 34 Ripple Effects A center expands partnerships to create a wider impact 36 Movers and Shakers 40 Under 40 honorees make waves in their communities | QUESTION 6 Research Roundup A showcase of recent research efforts across the college 8 The Sound of a Water Dog Author Jack E. Davis dives into childhood memories on the Gulf 10 Sea Change Gulf Scholars Program finds a home at the Graham Center 12 Holy Water Insights into the intersection of tradition and modernity in pilgrimages 14 Words Across Water As humans move, a closer look at the impacts on language | IN EVERY ISSUE 4 Dean’s Letter 40 Creative License New book releases from CLAS faculty and alumni 44 Laurels Celebrating outstanding achievements of students, staff, faculty, and alumni 46 Dean’s Circle Recognizing the generosity of our giving society 48 Crossword Puzzle Liquid Logic 16 28 | DISCOVER 16 The Call of Nature Ecologists show how animals shape their aquatic ecosystems 28 Oasis in the Desert Timeless water lessons from an ancient Peruvian civilization Wooden figure. @ Creative Pixels/Adobe Stock. Hippo gazing at the night sky. @ Alice/Adobe Stock.

From the Dean

As a chemist, I have always been fascinated by the way water is so central to geological history and life on our planet. In a foundational course I teach to undergraduates, we begin with the origin of elements, starting with hydrogen (H) — the universe’s most abundant element, initially created from protons and electrons combined in a cooling plasma. Later, oxygen atoms (O) emerged, produced in the cores of stars through the fusion of lighter elements like hydrogen. As the third most abundant element, oxygen readily pairs with two H atoms to produce water molecules (H2O). This fundamental chemistry brought water to Earth, forming oceans about 4 billion years ago.

Thanks to all that chemistry, water is everywhere in Florida. Whether in a creek, river, lake, wetland, spring, or ocean, water is nearby. I am often struck by the profound impact that water, in all its forms, has on our collective experiences. Indeed, the existence of life on earth requires water, and the oxygen we breathe (in the form of O2) is made from it by living cells with the help of sunlight.

During my tenure as Dean, I have watched our college transform into a hub for water research, environmental stewardship, and sustainability. Our dedication to these areas extends far beyond our campus, reaching communities near and far.

This issue of Ytori celebrates some CLAS folks who are “making waves.” You will meet geographers tackling challenges of extreme weather (page 20), ecologists investigating how animals act as connectors between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems (page 16), and an Andean archaeologist exploring how the ancient past and present meet when approaching water issues (page 28).

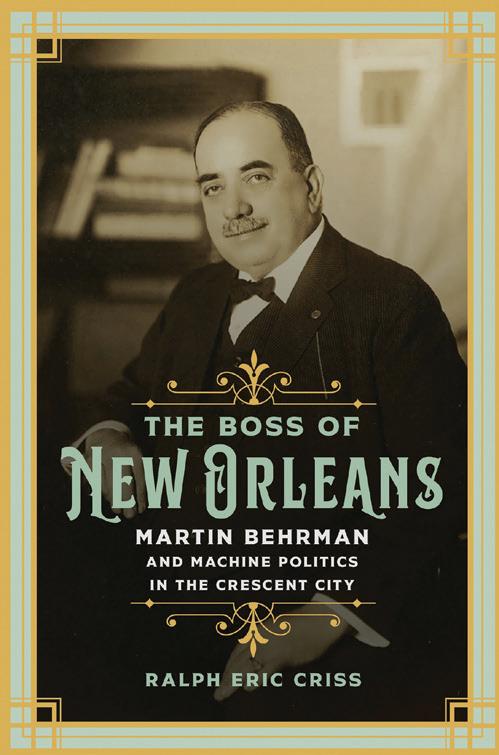

With my time as Dean drawing to a close this summer, I want to thank you for your commitment to our shared vision where the study of nature, society, and humanity helps us understand the world on which we live. It has been the privilege of a lifetime to serve our students and help prepare them for the future.

Just as water continuously adapts and flows through obstacles, our college has evolved to meet the challenges and opportunities we have encountered. As we navigate new beginnings and endings, I hope you find inspiration in water’s transformative nature.

Sincerely,

David E. Richardson Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

David E. Richardson Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

4 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

Photo by Michel Thomas.

CHANNELING IMPACT

JAMES “JIM” STIDHAM SR. (BSBA '50) found profound peace while paddling the tranquil waters of the St. Marks River. His deep connection to Florida’s waterways was more than a pastime; it was a passion he fervently shared with others.

Now, his enthusiasm lives on through the Stidham Endowment for Water Resources and Hydrology. Established by his son JIM STIDHAM JR. (Accounting '81, MA '83), this fund celebrates a life intertwined with the values of the University of Florida.

Reflecting on their close connection, Stidham Jr. recalls, “No matter where in the world I might be, our routine Sunday phone call was dominated by things happening at UF.”

The endowment extends Stidham Sr.’s devotion to environmental and water advocacy by supporting student research on the Florida aquifer, thereby fostering environmental stewardship.

Stidham Sr. embodied the spirit of service, from his robust military career to leadership in the community. His environmental

engineering firm, Jim Stidham and Associates, also doubled as a vibrant classroom. At any given time, a dozen college students could be found working and gaining hands-on experience, benefiting from Stidham Sr.’s transformative mentorship.

Many of the alumni from these cohorts now occupy key positions in water resources and engineering sectors, ensuring that Stidham Sr.’s enduring influence continues to ripple across Florida. The endowment aspires to continue his tradition by enabling more students to pursue meaningful careers in this vital sector.

The creation of this endowment honors Stidham Sr.’s lasting impact, the unbreakable bond between father and son, and their shared devotion to their alma mater. More than a tribute, it’s a pledge to protect our waterways and empower research for generations to come.

UNIVERSITY of FLORIDA

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 5

Shape the next wave of leaders, visit

YOUR SUPPORT CHANGES STUDENTS’ LIVES. LEARN HOW TO MAKE YOUR OWN LASTING IMPACT.

geology.ufl.edu/donate.

James “Jim” Stidham Sr. (1927 - 2018). Photo by Nouchine O. Stidham.

Roundup RESEARCH

Compiled by Emma Barrett

Faculty and researchers collaborate and innovate to gain a deeper understanding of our world. Here’s a snapshot of recent grants and publication highlights.

TINY ANTS DISRUPT LIONS’ HUNTING GAME

Scientists revealed how a small but mighty invasive ant species is disrupting East African ecosystem dynamics, making hunting hard for the revered lion. Investigated by ecologist TODD PALMER, the research spans three decades, using hidden camera traps, satellite tracking of lions, and statistical modeling.

exciting new research developments: clas.ufl.edu/researchroundup

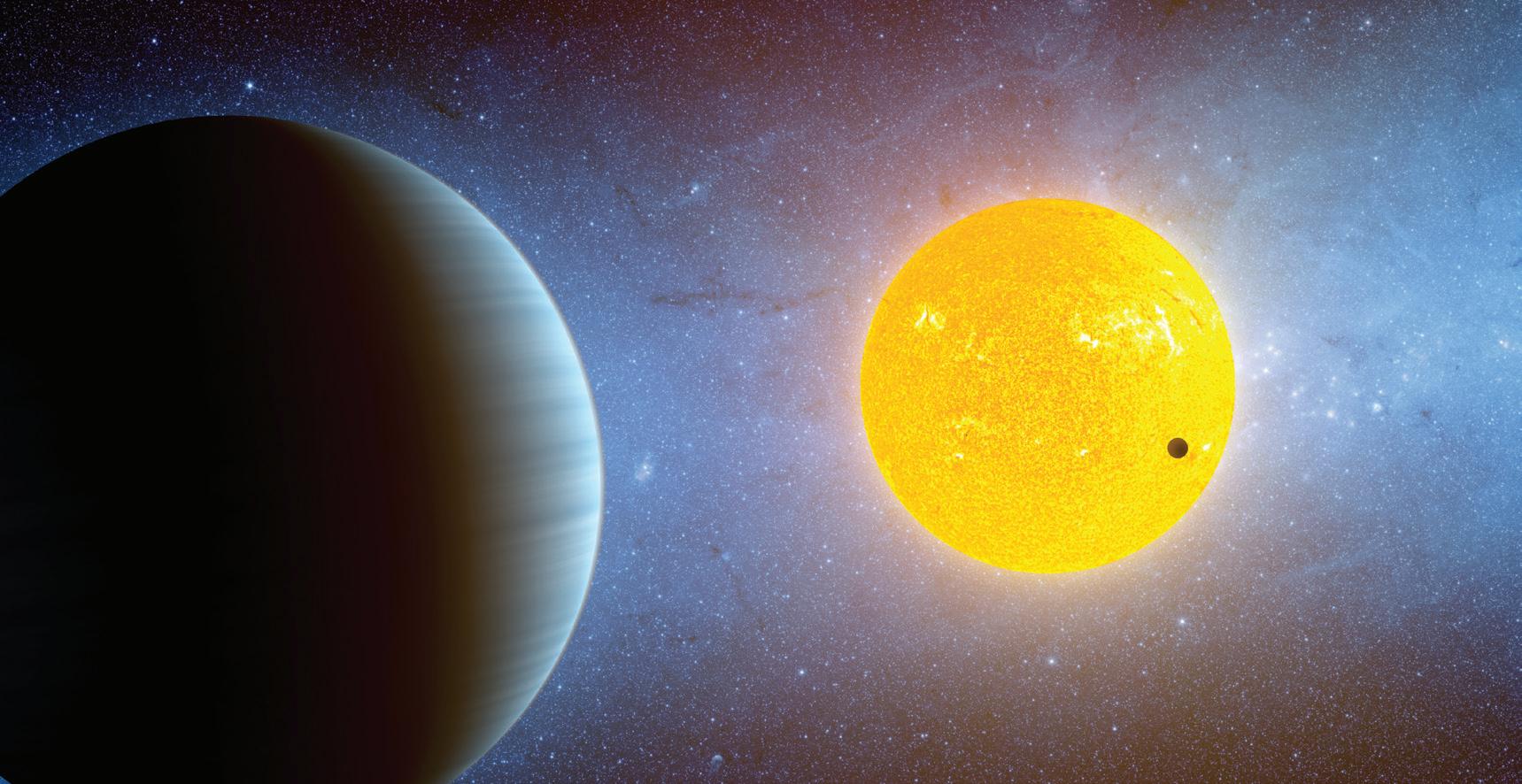

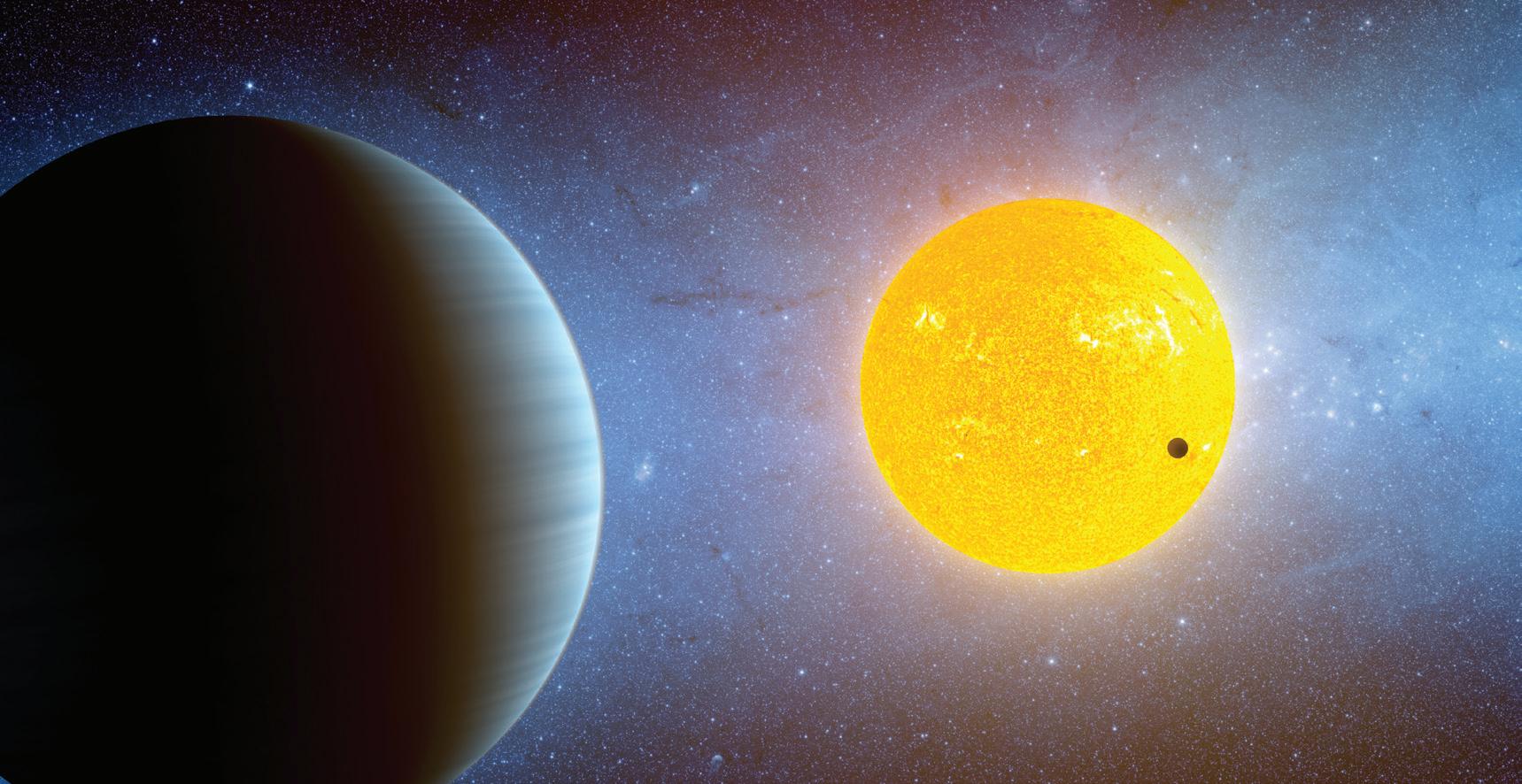

Astronomers have discovered the nearest young Earth-sized planet ever observed. It’s located near its sun-like star in the vicinity of the Big Dipper constellation. Despite its harsh environment with scorching temperatures and possible lava oceans, this young planet offers insights into the evolution of planets similar to ours.

Discovered with data from the Gaia and TESS telescopes, the planet orbits its star every four days, displaying rapid motion. Led by University of Florida astronomy doctoral student BEN CAPISTRANT and colleagues from UW-Madison, the findings provide a unique opportunity to study atmospheric

Historically, native ants protected acacia trees from large herbivores, but invasive ants have destroyed these bodyguard colonies, leaving the trees vulnerable. With a decline in the tree cover, lions now struggle to hunt preferred prey like zebras and are resorting to more challenging prey like buffaloes. The study highlights the intricate connections among species and the profound impact of seemingly minor disruptions on ecosystem stability. Researchers aim to understand the long-term effects of this shift and find solutions to preserve tree cover in these special environments.

loss in young planets, which is crucial for understanding their habitability. With an age of approximately 500 million years, the planet’s youth allows scientists to investigate previously unobserved processes.

6 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

A STRANGE LAVA WORLD

6 OF AND

Story first reported by UF News.

Big headed ant. @ Guawan/Adobe Stock. Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

Story first reported by UF News.

TURNING of the Tide

Sargassum colonies, crucial to Atlantic Ocean ecosystems, have surged recently but remained enigmatic until now. In a groundbreaking study led by UF’s Department of Biology and Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, researchers investigated the thermal properties of sargassum, a floating brown algae found in large colonies in the ocean.

Led by alumna ALEXANDRA GULICK, PhD candidate NERINE CONSTANT, the center’s Director KAREN

BJORNDAL, and Associate Director ALAN BOLTEN, since deceased, the study revealed sargassum colonies maintain higher temperatures than surrounding open water by absorbing solar heat. This impacts organism development and growth, as colonies serve as vital habitats for marine species by providing shelter and food sources.

The research, part of the Greenpeace Pole to Pole expedition in the Sargasso Sea, will extend to other expanding sargassum areas. The goal is to understand its impact on fauna amid climate change, as well as to quantify responses to temperature changes and gain insights into the broader implications of sargassum proliferation.

A TALE OF TWO FORESTS

A new analysis of U.S. Forest Service data reveals how climate change reshapes forests across the United States. The study, led by UF biologists J. AARON HOGAN and JEREMY W. LICHSTEIN, reveals a stark regional imbalance in forest productivity. The Western U.S. is experiencing slowdowns in tree growth and survival due to severe climate impacts, while the Eastern U.S. is seeing accelerated growth.

These changes have implications for the forest's ability to act as carbon sinks, as drought-impacted regions in the West may experience decreased carbon storage, potentially exacerbating climate change.

The study examined data from 1999 to 2020, encompassing more than one million trees, and emphasizes the urgent need for emissions reduction to maintain forest health. The researchers stress the importance of collaborative efforts to achieve net-zero emissions and ensure the resilience of forest ecosystems in the face of climate challenges.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 7 Algue sargasse @ F r a n c k M a z /saeebodA .kcotS

Kepler-10 b. NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle.

Photo by Jeremy Lichstein.

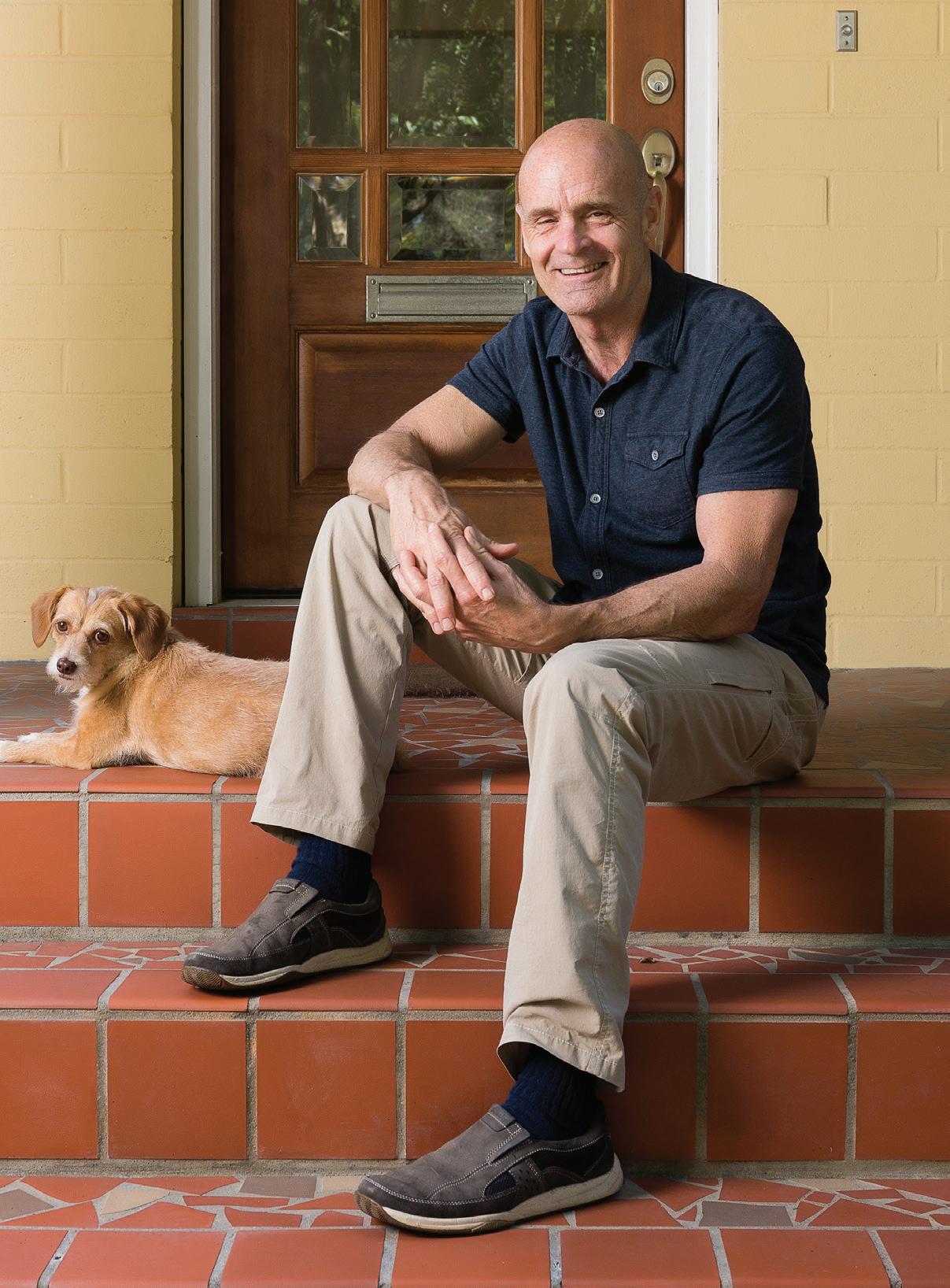

The Sound of a Water Dog

By Jack E. Davis

Lulu had a water-dog’s itch and had it bad. From one day to the next, she fished the shallows fronting our house nonstop. Back and forth she sloshed, pouncing on anything darting or flashing, her cropped tail spinning like a boat propeller. She was the family’s dog, a springer spaniel with sun-faded liver-and-white coloring, but I had a similar itch that gave us a special bond.

We forged it after my family moved to Florida when I was 10. Our new house was a proud old one. A man named Darling built it of southern pine between live oaks beside Santa Rosa Sound, a 40-mile-long luminous sliver that underscored Florida’s western panhandle. Our view across took in an equally rangy barrier island quietly left undeveloped and preserved in a dune-quilted serenity. At night, lying

in bed beside a breeze-filled window, you could hear breakers rolling onto its beach from the Gulf of Mexico. The immutable sea was the animating center of this canvas-like setting. But it was the Sound that situated my days.

At first, they felt lonely. I had known only suburban enclaves booming with kids, and our new home came with neither bicycled streets nor playmates. But I had the Sound, and soon enough a canoe with a six-horse kicker clamped to its squared-off stern. I provisioned my vessel with a fishing rod, live bait, and cream-filled Mickey cakes (Merita Breads’ not the Mouse’s). With Lulu in the bow sniffing and tasting the salt and tides, we explored every spoil island, lagoon, and hideaway. We hurdled the wakes of sturdy tugs pushing rusty barges, and bored through afternoon

rainstorms that washed the day clean before the sun reappeared and steamed the wetness out of us. I cast my fishing line singing toward dark shapes in the water, hoping to land a big one. Lulu pored over flats for anything of any size. Her catch rate was zero but her joy was off the charts. At day’s end, when I smelled like, well, a wet dog in from the flats, I jumped off our dock with a bar of soap. Lulu trolled the home shoreline for a last chance with luck, her spinning tail anticipating. At my grade school, they didn’t teach about water, nature, and the like. I don’t think I heard the word ecology until college. But that didn’t matter. Each vibrant season on the Sound was a semester of learning. In the fall, great mullet runs set out for spawning grounds in the Gulf, with feeding

QUESTION 8 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

“ Some say water is not a living thing. But the Sound taught me otherwise. It lives within me.”

dolphins hot on mullet tails. Slack tides of winter opened bountiful flats to northern plovers, Sanderlings, and dunlins. Once plump with migration fat, they answered spring’s call to return to upper latitudes. Wild millions of feathered others winged in from as far away as Patagonia en route to as far north as Arctic breeding grounds. In summer, crabs, minnows, baby shrimp, and mysteries of all sorts hid in shaggy seagrass beds eluding predators. After outgrowing their sanctuaries, hapless numbers ended up in the gullets of pelicans and the talons of osprey.

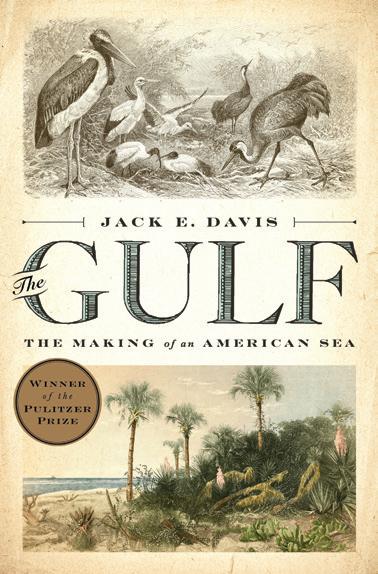

Long after Lulu departed this world to fish in another, I found myself writing a book about the Gulf. The inspiration had come like a calling yet seemingly out of nowhere. All the while, my thoughts kept drifting to the Sound, many years and many

miles removed. So, on one fine spring weekend, I returned. Happily, little had changed. The starkest departure from my past was me paddling a kayak with my 11-year-old daughter holding forth at the bow. As we passed over remembered waters, it struck me that my boyhood attachment to the Sound had endured and gently nudged me to write about its parent sea.

New research at the time revealed that humans are endowed with neurological and psychological stimuli that call us to be near water. In motion or stillness, it is transporting and vitalizing, inviting happiness and inner peace. Just as we inhabit watery places, water inhabits us.

None of this came as a surprise to me. It affirmed what had arisen within, the sea stirring me to write not solely from the mind but from a deeper place,

to connect with readers as the Sound connected with me so that they might know the Gulf in its truest nature— essential to our quality of life.

Some say water is not a living thing. But the Sound taught me otherwise. It lives within me. It guided me on a journey that led to composing a heartfelt portrait of the Gulf that resonated with a wide readership. It engendered knowledge to pass on to students in courses that it invited me to create and in the university’s new Gulf Scholars Program that it prepared me to help launch.

Water was an awakening, a revelation, and the future for a kid with a dog.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 9

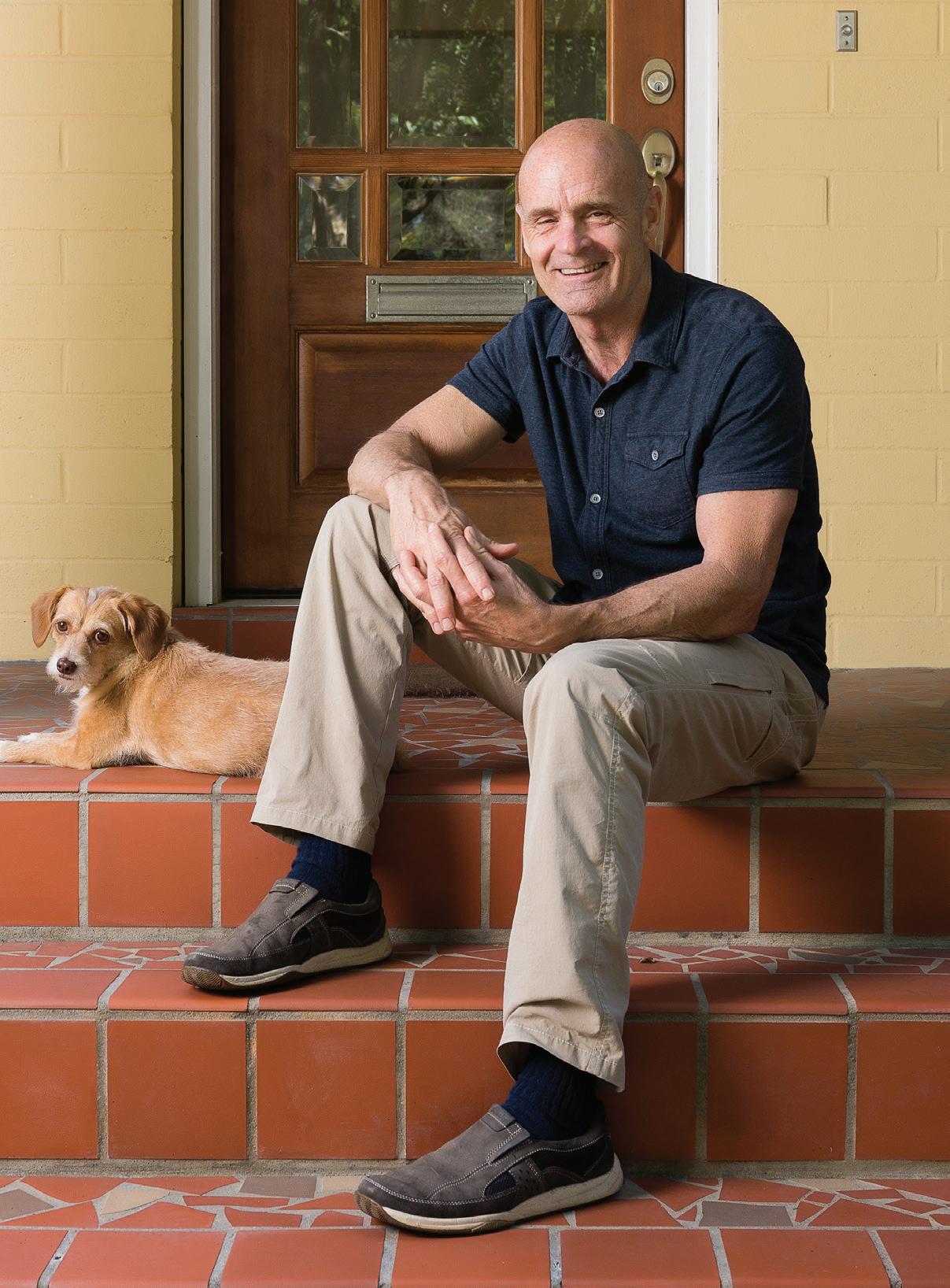

Jack Davis and his dog Izzy by Bernard Brzezinski/UF Photography. Springer spaniel. @ Wolfe/Adobe Stock.

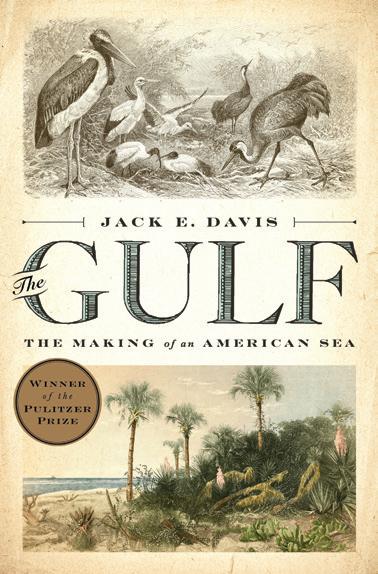

Top: Davis’ Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.” Above, left to right: Davis’ mother Becky, and sisters Jill and Wendy with Lulu; the family home on Santa Rosa Sound; on the Sound with great-grandmother Nanny, sister Jill, and Lulu in the background. Photos courtesy of Jack E. Davis.

Jack Davis, in addition to being an author, is a distinguished professor of history and the Rothman Family Chair in the Humanities.

Sea Change

By Douglas Ray

Seeking a healthier future for the Gulf of Mexico

Growing up in Pensacola, REBECCA

BURTON had a front-row seat to the Gulf of Mexico, where the power of the American Sea to build communities over the decades and to wipe them away in a season has been unfolding since long before the first Europeans arrived on its shores.

She saw how development and industry could harness the beauty and bounties of the Gulf while devastating its ecology. This led her to an early career in environmental journalism and science communication. She founded The Marjorie, a Floridabased reporting nonprofit focused on environmental justice. She also led communications for the Florida Sea Grant and for the UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute, organizing environmental leadership experiential learning programs for students.

Recently, Burton was tapped to lead the University of Florida’s Gulf Scholars Program. Starting this fall, the program will equip undergraduates with the knowledge and skills to create solutions for a healthier Gulf of Mexico and more vibrant inland communities.

Burton’s personal connection to the Gulf runs deep. Her grandfather and great-grandfather were Gulf fishermen who depended on its resources for their livelihoods.

“Growing up in Pensacola, I learned to appreciate the beauty of this waterbody and its ability to provide for our community — and

the nation,” Burton said. “But I’ve also experienced firsthand many of the challenges facing the region.”

In 2010, the nation’s reliance on the Gulf of Mexico made international news when an explosion on the BP Deepwater Horizon oil platform killed 11 people and led to the largest oil spill in history. This catastrophic event highlighted the urgent need for comprehensive solutions to the complex environmental, health, and social challenges facing communities along the Gulf.

“I’ve lost my home in a hurricane. My middle school was shut down due to its location next to a toxic waste site. And I remember crying with a group of friends when news of the oil spill broke as we savored what we thought would be our last Gulf oysters,” Burton recalled. These experiences motivated Burton to become an environmental reporter. She sought to better understand these challenges, explain them to her family, and explore possible solutions while maintaining hope.

“I think those of us who grew up on the Gulf have a strong sense of place, but sometimes the challenges lead us to leave,” she said. “I’m so excited for this new role to help students develop a shared mission to ensure its ability to support future generations.”

Now with criminal settlement funds from the companies found responsible in the BP Deepwater

10 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

QUESTION Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock. Oysters. @ Sketch Master/Adobe Stock.

Horizon oil spill, the Gulf Scholars Program aims to prepare UF undergraduates from a variety of disciplines with the knowledge and skills to imagine and implement innovative solutions for a healthy and thriving Gulf for generations to come.

UF was one of five universities recently selected as a host institution for the third cohort of the Gulf Scholars Program, a five-year, $12.7 million pilot program funded by the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Last fall, UF President Ben Sasse awarded an additional $414,000 in strategic funds from the state legislature to bolster the $475,000 grant.

“The Gulf Scholars Program provides an opportunity to reach undergraduate students — many of whom have home ties to the Gulf region — and engage them in rigorous education and training on issues that directly impact their own communities,” said Karena Mothershed, senior program manager of the Gulf Research Program’s Board on Gulf Education and Engagement.

“We hope this program inspires students to envision a future in the Gulf region and work to make it an even better place to live, work, and thrive,” she said.

The program will include Gulffocused academic courses, experiential and place-based learning opportunities (research, internships, field excursions,

etc.), faculty-mentored Gulf Impact Projects, and public programming. Each of these components will culminate in a Gulf studies minor or certificate. With its home in the Bob Graham Center for Public Service, the UF Gulf Scholars Program will place effective civic engagement, public service, and leadership at the forefront of its programming.

“The Bob Graham Center for Public Service is delighted to house the Gulf Scholars Program. As governor and senator, BOB GRAHAM sought to understand the complex relationships between Florida’s climate, landscape, waterways, and marine life. He implemented policies to restore the Everglades, and has long advocated for Florida’s manatees,” said MATT JACOBS, director of the Bob Graham Center for Public Service.

Faculty may sign up to hear about funding to develop related courses or host experiential learning opportunities. Students can expect to register for these classes as early as Spring 2025. More information about experiential learning and internship opportunities and support for Gulf Impact Projects will be announced in the coming months.

“The challenges facing the Gulf and its communities are messy, and we will rely on a wide variety of skill sets to adapt and plan for the future,” said Burton, the program coordinator.

“ We hope this program inspires students to envision a future in the Gulf region and work to make it an even better place to live, work, and thrive.”

— Karena Mothershed

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 11

DIVE INTO THE GULF SCHOLARS PROGRAM

gulfscholars.bobgrahamcenter.ufl.edu

holy Water

By Douglas Ray

For Africans in the Sahel, water carries blessings as climate change spells trouble

The Sahel stretches across Africa, a narrow band sandwiched between the arid Sahara to the north and the wetter savannas of the central continent to its south, a transition zone for culture as well as climate, where people flow across national borders like water.

Migration through this crossroads has meant a mixing of languages, religions, and ethno-national identities.

ABDOULAYE KANE, associate professor of anthropology and African studies, has studied the region for years, focusing on transnationalism, migration, global connections, and the African diaspora. His research has explored the pilgrimages made by Sufis, followers of a mystic tradition that extends to the earliest days of Islam.

Sufism bridges Islam’s Sunni and Shia divisions. It emphasizes purification, spirituality, rituals, asceticism, and hidden knowledge.

Among the major Sufi orders, but a recent one, is Tijaniyyah, widespread in West Africa, and seated in Fes, Morocco, the resting place of its founder, Ahmad al-Tijani (1737 – 1815).

Kane has been studying the transSaharan religious circuits of the Tijaniyyah across the national borders between the Sahel and North Africa, particularly the annual pilgrimages to Fes that draw followers from

Senegal, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, and from across the globe.

The Sufi pilgrims in the Sahel are motivated by the search for blessings, obtained at the tomb of Shaykh Tijani, through Tijani’s descendants, and in water from the well the tradition says was dug by Tijani.

“Water is among the first things because water is so vital in this part of the world,” said Kane in April as he was sitting in his office in Grinter Hall. “Going to fetch water has always been a gendered social space used by women to chat and get advice on issues related to marriage, pregnancy and health, working conditions within the household and how to handle in-laws, etc.”

Among the esoteric Tijaniyyah beliefs is that the well in Fes is mystically connected to a source of the Zamzam Well in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, more than 3,500 miles away.

“It makes a lot of sense from within their traditions to make these kinds of claims,” Kane said.

Stories in Islam recount that the Zamzam Well miraculously opened in the desert when Ishmael, son of Abraham, was left with his mother Hagar. According to tradition, the well was lost but rediscovered by

QUESTION

Muhammad. Each year, millions of pilgrims making the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca drink from the well.

“Water is a sign of provision,” Kane noted, pointing to another ancient African, the biblical figure Moses, who was transported to safety as a baby in a basket floating on the Nile and who, according to tradition, rescued his people by parting the sea.

Unlike blessings from Tijani’s descendants or a visit to his tomb, water can be transported to those who are unable to travel. Pilgrims to Fes often return with containers holding blessed water that can be used by the faithful to heal, protect, and bring good fortune to families and friends.

Kane said pilgrims place bottles of well water next to Tijani’s tomb overnight or bring them to rituals on Fridays (Hadaratul Jumaat), during which the Tijaniyyah believe the Prophet Mohamad, his companions, and Shaykh Tijani are present, thus capturing the blessings from the distinguished, if invisible, guests.

When security restrictions limited the volume of liquids that airlines would allow on flights, it wasn’t unusual to see large containers

holding blessed water abandoned at airport security gates. Today, you might be more likely to see pilgrims loading 10-gallon water bottles aboard buses heading to their homes.

“Mobility is an important aspect of survival in a very unpredictable region,” he said.

These patterns began long before the colonial era when there were large cities across the Sahel that were linked by trade. Seasonal migrations also saw herds of livestock moved from grasslands when the rainy season ended. New disruptions from political upheaval, religious fundamentalism, and climate change have made some of this travel more perilous.

In May, Kane traveled to Thilogne, the town in Senegal where he grew up, and spoke over Zoom from his mother’s house as the temperature outside reached 124 degrees.

“The major issue here is the demographics. We have rapidly growing populations, and the states are struggling to create enough jobs for the youth. This started in the early 1980s and, since then, a country like Senegal has been adding more than 200,000 youth into the job market

per year with an ability to create less than 40,000 jobs,” Kane said.

“So, the excess is people who end up going into the informal economy with precarious and poorly paid jobs. The youth is just struggling to do something. Oftentimes that’s not sustainable so they end up exploring migration as an option,” he said.

“The second major factor is related to the environment. In rural areas, like the one where I am right now, the rain has been really very unpredictable. You have the cycles of droughts,” he said. “More and more, we are seeing people who are climate refugees, those whose livelihood is completely jeopardized by climate change.”

Migration. @ pronoia/Adobe Stock. Chalice. @ F.J. Carneros/Adobe Stock. Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

By Douglas Ray

By Douglas Ray

LANGUAGE FLOWS AS PEOPLE ADAPT TO NEW REALITIES

“How many languages do you speak?”

The lecturer visiting from Guinea thought it was an odd question, posed by a student reporter for the Independent Florida Alligator. The answer took him a minute to consider: seven.

FIONA MCLAUGHLIN, professor of linguistics and African languages, recalled that the lecturer, like many from West Africa, was highly multilingual. “He said he had never ever thought of counting these languages. It was sort of like saying how many dances do you know? The tango, the waltz, the cha-cha-cha: You don't count them, you just do them, right?” she said with a laugh.

QUESTION 14 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

In fact, counting languages often is tricky. There is no definitive tally of languages spoken in Africa, the richest continent in linguistics, but somewhere around 2,000 is often cited.

“Multilingualism is the norm in the world,” McLaughlin said. “Americans are familiar with bilingualism, particularly here in Florida where we hear so many Spanish speakers or Haitian Creole speakers. But when you go elsewhere in the world, especially in Africa, many people have quite extensive repertoires, maybe five or six languages.”

said. “But some parts of their native language are not directly translatable.”

“One example is the word ‘with,’ as in ‘I am speaking with you.’ You can’t translate that directly into Yoruba,” said Odutola, speaking of a language predominant in his home nation of Nigeria.

People speaking different languages often live close together, and there is a long tradition of migration, trade, and other interchange among groups in Africa.

“So when people are moving, they are determining what languages become useful to them and which ones are no longer useful. They’ll adjust accordingly. It's really a function of people's biographies and experiences,” McLaughlin said.

How people use languages, and how they are perceived by others, is a field pursued both by McLaughlin and by KOLE ADE ODUTOLA, associate instructional professor in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures. Both also are Africanists, studying the cultures and dynamics, particularly in West Africa, which has seen large migrations to Europe and North America.

“When people leave their homeland and move somewhere else, they still try to express themselves in the language of their parents,” Odutola

Echoes of African languages can be found in the sound of words and the structure of phrases in English, Caribbean dialects, and other languages influenced by the “forced migration” of Africans through the slave trade. Odutola points to “ire” (ahy-ree) in Jamaican Patois, which can be loosely translated as “cool” or “ok.”

displace populations in Africa and globally. She has begun to explore “eco-linguistics,” the intersection of ecology and linguistics, and plans to launch a course in this area in the upcoming fall semester.

The course will explore climate change discourse, societal views on humanity’s relationship with the natural world, and the role of language within these constructs. It will also explore language endangerment, particularly in ecosystems where communities are compelled to disperse and potentially abandon their original languages due to events such as climate change-induced migrations.

“This word comes from a word of blessing in the Yoruba language. It’s almost the same spelling, but in Yoruba, the ‘ahy’ is pronounced as ‘ee,’ so we say ‘ee-ree’,” he said. “We talk about language contact and conflicts. Where there is a predominant language or the language of the colonizers, when it comes in contact with the language of a people, there’s going to be some modification or what people call ‘creolization’.”

This can also affect how language is structured. Odutola pointed to what is sometimes called “Ebonics,” phrasing used by some African Americans. “When you hear someone say ‘Where you at?’ — that is not traditionally proper English. But that structure mirrors Yoruba. So this recalls the structure from the homeland,” Odutola said.

McLaughlin’s research confirms the evolving dynamics, particularly as new forces such as climate change

Nevertheless, the prevalence of multilingualism in Africa shows the value placed on linguistic diversity and the willingness to bridge linguistic barriers. When people are forced to leave their communities and are scattered across different regions, the ability to communicate in multiple languages becomes crucial for displaced individuals to navigate their new surroundings and connect with locals.

“For a lot of Africans, multilingualism is something that they use in everyday life,” McLaughlin said. “You see a neighbor coming by who speaks a different language than your own native language and you greet them in that language, just out of solidarity and showing respect to them.”

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 15

Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

The Call of Nature

By Lauren Barnett

As day gives way to night on the Maasai Mara National Reserve, a new world awakens. A team of scientists sits within the seclusion of their research camp. They eagerly await the transformation.

Modern luxuries are sparse in the Kenyan wilderness. The camp, nestled in a wooded thicket, lacks running water or power. Here, a cluster of canvas tents offer shelter, a humble arrangement in an expanse where animals far outnumber humans. But there’s no lack of entertainment on site: The savanna comes alive at night.

From their tents, ecologists CHRIS DUTTON and AMANDA SUBALUSKY tune in to the nightly concert. A symphony of sounds floods the darkness. No fencing separates the camp from the passing wildlife, and the proximity leads to an immersive auditory experience. When leopards hunt, they make a distinctive sawing sound, recalls Dutton. It’s a haunting indicator of the wild at work. Meanwhile, a herd of elephants, mere steps away from the campsite, rest fitfully. They’re insomniacs, clocking only about two hours of sleep per night. To an untrained ear, their presence might go unnoticed, but Dutton has become quite familiar with the peculiar sounds of their digestion. “It sounds like someone shaking a piece of sheet metal,” he said.

16 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

DISCOVER Hippo gazing at the night sky. @ Alice/Adobe Stock

GUT REACTIONS

Digestion is something to which Dutton and Subalusky are closely attuned. As zoogeochemists, they’re engrossed in understanding the role of animals in nutrient cycling. In this process, nutrients circulate from the environment into living organisms and back again, supporting life and ecosystem health.

It’s not glamorous work: There’s a lot of defecation, death, and decomposition involved. But their research is helping to connect the dots between wildlife and their environments.

“We all enjoy seeing animals in our environment, in our daily lives. We see birds in our yard. We see fireflies at night. We see deer moving through our neighborhood,” Subalusky said. “Our research is really focused on understanding how those animals aren't just passing through, but are actually shaping the ecosystems that they live in.”

The duo has taken a deep dive into the guts of the animal kingdom, uncovering how vital digestion is for ecological balance. Their studies show how when animals consume and process food, they subsequently expel not only waste but also carbon, nutrients, and gut microbes that can greatly affect the surrounding environment.

The scientists collect samples and analyze them back at their research hub on the University of Florida’s main campus, the Subalusky Lab. Their investigations span a variety of ecosystems and animal interactions, but their interests lie heavily with animals that move between land and water.

Water bodies often serve as hubs of wildlife activity. Animals congregate around the water and transfer resources from different parts of the

landscape to these aquatic centers. While water predominantly moves downstream, animals have the ability to move resources in various directions, including uphill. Subalusky describes this as the Earth’s natural circulatory system.

She points out that while microbial and plant communities are often the focal points of ecological observation, animals play a pivotal role in shaping ecosystems through their ability to concentrate and distribute nutrients.

“Animals move nutrients across landscapes, sometimes in complex ways and sometimes over far distances,” Subalusky said. “So, they can actually have kind of a disproportionately important impact on ecosystem processes.”

Subalusky posits that the tendency to underestimate animals’ ecological impact may stem from the massive declines in wildlife populations, which obscure the visibility of these once-numerous species. However, that’s not the case in the Serengeti Mara, where large animal populations still dominate the scene.

“In a place like that, it’s much easier to see how strongly animals can impact ecosystems,” she said.

Amanda Subalusky sets up litterbags in the Mara River, Kenya to measure decomposition rates. Courtesy of the Subalusky Lab.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 17

LIQUID ASSETS

Despite the challenges presented by wildlife and natural events, which have led to the loss of thousands of dollars in equipment, the Mara remains a rich and rewarding field for research. Since 2008, Dutton and Subalusky have collaborated with Kenyan institutions and local communities, including the Indigenous Maasai people, who have coexisted with the region’s wildlife for centuries. The team has stationed data collection systems throughout the basin, allowing them to remotely monitor environmental dynamics.

Over 4,000 hippopotamuses reside in this region, partaking in group wallowing in the rivers. Each animal consumes nearly 100 pounds of food daily, accumulating significant waste in the pools where they linger. Dutton has noted that this behavior, while primarily a cooling mechanism, could also play an essential role in the nutrient cycle of the region.

He discovered that the microorganisms in hippo-infested pools bear a closer resemblance to those in the hippo gut rather than to those in typical river water. The team coined the term “meta-gut,” reflecting the altered aquatic

environment when infused with the hippo’s microbes. The phenomenon may benefit the hippos, functioning “almost like a probiotic shake,” according to Dutton. Interestingly, hippos bathing in these enriched pools appear to display less stress and aggression, hinting at the meta-gut’s role in modulating their behavior.

“It’s a really novel perspective,” Subalusky said. “I don’t think people thought that animals could have this strong of an influence on the shaping of microbial communities.”

DISCOVER 18 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

Left: Amanda Subalusky collects hippo feces. Above: Chris Dutton and Narasha, a local Maasai warrior, collect aquatic macroinvertebrates using a kick-net.

INTO THE WILD

The Mara hosts the world’s largest remaining overland migration. Each year, more than 1.3 million wildebeest cross this treacherous terrain, with many perishing in the river. Subalusky’s research reveals that their decomposing bodies fuel the river for months or even years afterward, a true display of the circle of life.

This phenomenon offers a window into historical ecosystems once shaped by large herds, such as the 30 million to 60 million bison that roamed North America’s Great Plains. These herds similarly encountered mass drownings in river crossings, influencing the evolution of the landscape. Now, studying the Mara has inspired the researchers to undertake studies that help us better understand the impacts of large migrations and the resulting changes in the American West due to the bison decline.

Additionally, the team is exploring the ecological impacts of hippos in an unexpected landscape: Colombia. Drug kingpin Pablo Escobar imported four hippos to his estate in the 1980s. After his death, they escaped to the nearby Magdalena River, where they have since formed a feral population growing at an annual rate of 9.5%. The Subalusky Lab is collaborating with international experts to model their population growth and evaluate potential ecological and community impacts under various control strategies.

Closer to home, Dutton and Subalusky are investigating Florida’s diverse fauna and impacts on waterways. They’re co-leading a study on seasonal wetlands, a key yet unprotected habitat under the Clean Water Act, to explore their ecological and hydrological connectivity.

American alligators play a pivotal role here, acting as ecosystem engineers as they burrow. Additionally, the team is exploring how water level variations can impact carbon cycling. They’re also turning their attention to the University of Florida’s campus, where they plan to develop a center to study animal movement and landscape connectivity. Their objective is to transform the campus into a dynamic living laboratory that tracks the movements of its notable animal residents, including alligators, bats, and squirrels.

Stepping back, Dutton and Subalusky’s work reaffirms a vital yet often overlooked principle: Across every corner of the globe, animals play unseen but essential roles in balancing our ecosystems. Through actions like nutrient cycling, they support ecological health, which, in turn, lends humans a helping hand in providing access to clean water and fertile soil. Preserving biodiversity is not just about saving animal species; it’s also about protecting the delicate ecosystem services that human communities rely on.

“The animals that we share our world with also help shape our world,” Subalusky said.

Above: Students Samantha Howley, Joshua Epstein, and Susannah Lohmann deploy a sensor network at UF's Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Photo by Michel Thomas.

SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 19

THE FILM CLAS.UFL.EDU/ ANIMALS

WATCH

Courtesy of the Subalusky Lab.

BY LAUREN BARNETT & BRIAN SMITH

DISCOVER 20 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

aterscapes

UF Geography charts a course toward a more water-resilient future

Driving through the picturesque university town of Stellenbosch, located about 30 miles east of Cape Town, South Africa, was not the enjoyable trip

JANE SOUTHWORTH had expected.

“We couldn’t even get to our hotel,” she recalls. “Half of the town was under water.”

A devastating series of floods had just submerged much of the province, the result of heavy rainfall. Southworth traveled to the region last summer to research land cover change in agricultural areas, and she was confronted firsthand with the water issues afflicting many parts of the world.

In nearby Cape Town, Southworth explains that they’re using more water than they have, and during droughts, severe water restrictions are imposed. Development and irrigation practices contribute to the water scarcity issue there, but climate variability exacerbates the situation. And, despite the sudden deluge of water, there’s an even more alarming issue: Worsening droughts threaten to leave the region’s taps dry.

Cape Town is not the only city facing a future with too little water. The 2024 World Water Development Report reveals that 2.2 billion people worldwide do not have access to safely managed drinking water, and as of 2022, approximately half of the global population has experienced at least temporary severe water scarcity.

Geography is essential for tackling water-related challenges. Over 80% of all collected data involves a spatial component, making the mapping and analysis of water dynamics crucial for future insights.

“If you think of almost any problem that’s facing the world, it’s spatial,” Southworth said. “You can look at how things vary over space and time and start understanding those relationships. If you aren’t looking at that spatial component, you’re missing so much of what’s going on.”

At the University of Florida, geographers are delving into interrelated climate shifts and their effects on social and environmental systems. Their work is not just academic; it has vital real-world implications for the well-being of both human and natural systems.

“When we talk about climate variability and extreme weather events, they’re just everywhere right now,” she said. “It has such a huge impact on every facet of society; it’s not just the physical structures being impacted.” Water is top of mind for Southworth and the researchers she collaborates with in the field. As professor and chair of the Department of Geography, Southworth leads the charge toward solving these pressing issues and inspiring the next generation to join the cause.

“Water, for most of us in the department, is either an event or a driver of what we’re exploring in our work,” she said. “It’s the great connector.”

Here, you’ll meet just a few of the researchers working toward a more resilient future. As graduates of the program take their newly acquired skills out into the workforce, the ripple effects of their impact extend far and wide.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 21

ortifying Coastal Communities

Coastal communities worldwide are grappling with ever-increasing threats such as storm surges, high water levels, and erosion — challenges intensified by climate change. At UF, geographers are pioneering research dedicated to enhancing coastal resilience through a deeper understanding and proactive community engagement.

Assistant Professor KEVIN ASH’s childhood experiences in Tulsa, Oklahoma, sparked his interest in extreme weather events. He vividly recalls the chaos brought by a storm that overwhelmed a nearby dam, flooding multiple city areas. Today, he is a leading authority on red tides, events caused by proliferations of algae that harm local ecosystems and pose health threats by releasing toxins. These events have become more verdant and frequent over the last few decades, especially on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

“Despite their rising threat to humans, red tide and harmful algal blooms are not included in widely used risk and vulnerability metrics, such as FEMA’s

Vulnerability Index (CRTVI), to which he contributes his expertise on geospatial analysis and risk, vulnerability, and resilience metrics. They hope that this index will help communities affected by red tides better prepare for them and minimize their harmful effects on humans.

This last aspect is the key to all of Ash’s work, not just his red tide projects. He hopes that his research will give communities everywhere the tools they need to protect themselves from disasters and mitigate their damage. Once his team has finished its work on this index, Ash hopes to develop better ways to communicate the red tide risks and vulnerabilities with decision-

DISCOVER

“I want to participate in research that is impactful beyond the academic pursuit, contributing to policy changes if appropriate, and encouraging and assisting young people who are developing their interests and careers,” Ash said.

KATY SERAFIN, a coastal scientist and assistant professor, is similarly invested in coastal resilience, specializing in coastal flooding and erosion. Her journey into this field was sparked by childhood visits to the Outer Banks in North Carolina, where she was captivated by the dramatic shifts in the coastline following major storms. This early fascination led Serafin to research coastal flooding and erosion, including the factors that propel flooding events.

In Florida, where the symbiosis between land and water defines the essence of life, Serafin’s work takes on a heightened significance. The Sunshine State, with its sprawling coastlines, is a bustling hub of population, economic activity, and critical infrastructure — all resting

precariously at the mercy of the tides. Her observations echo a universal truth: the health of our coastlines is inseparable from the resilience of our communities.

“Understanding why and when we have too much water in some places, and how that will evolve in the future is essential for building resilient communities in the face of flooding events,” she said.

Serafin takes her scientific findings a step further. She actively works to ensure that her findings inform real-world strategies for coastal management and planning. Her work centers on the detailed intersection of geographical changes and human impacts. She’s also committed to shaping future leaders in coastal science and those who interact with the coast.

“I hope that my courses help Florida’s future workforce develop a fundamental understanding of sea level rise and the relevant drivers of flooding and erosion hazards,” she said, “as well as grow in connecting the science

The Department of Geography is excited to announce the debut of its new Bachelor of Science program in Meteorology, launching this fall. It’s designed to delve into the intricacies of weather forecasting and climate projections, while providing students with communication skills to share forecasts with the public. Timely and accurate weather forecasting is not just about understanding the sky above — it’s about saving lives, shaping policies, and helping Florida’s businesses.

The curriculum will blend a mix of established geography courses and nine new meteorologyspecific classes. Students can choose from three specialization tracks: Applied Meteorology, Hazards, and Global Change; General Atmospheric Science; and Broadcast Meteorology.

Students specializing in Broadcast Meteorology will benefit from a collaboration with the College of Journalism and Communications, involving 15 credit hours of specialized coursework. Strategic electives like these complement the hands-on training and theoretical approaches taught throughout the meteorology program.

Assistant Instructional Professor STEPHEN MULLENS, supported by his colleagues Wen, Matyas, and ESTHER MULLENS — with their extensive expertise in atmospheric sciences and education — will lead and coordinate the program.

Mullens expressed his enthusiasm for the program's launch, saying, “I’m excited to watch how the motivation and creativity of our students and faculty feed off and encourage each other,” he said. “It’s going to be thrilling to observe how students help us shape the program, improving the experience for future students.”

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 23

TODAY’S

Fallen trees. @ Wollwerth Imagery/Adobe Stock. Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

FORECAST

uenching

waterborne woes

As climate change redefines global weather patterns and temperatures, its impact on disease dynamics has caught the attention of several UF geographers. Escalating incidents of extreme weather events, such as severe droughts and floods, are disrupting patterns of foodborne and waterborne infectious diseases. Moreover, fluctuating climate conditions and declining air quality have been linked to a surge in respiratory illnesses, including influenza. Even soil quality is a concern, as altered compositions may harbor pathogens that threaten agricultural productivity.

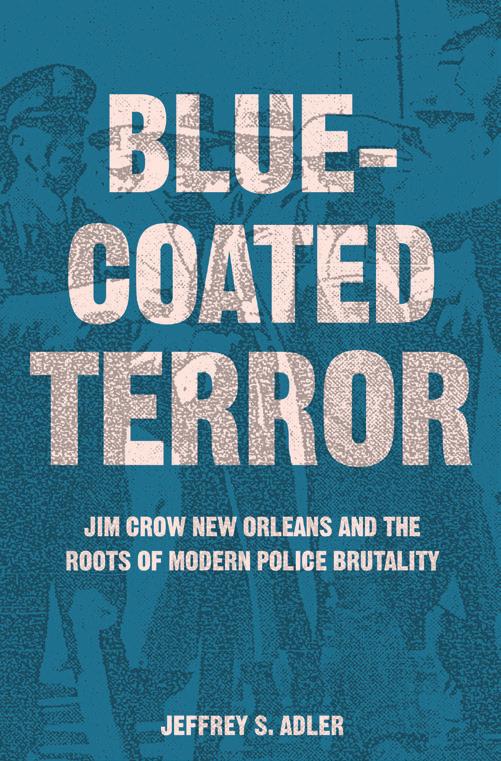

Medical geographer JASON BLACKBURN has dedicated the last six years to investigating the impacts of climate change on health, focusing on a pathogen called Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei).

This bacterium, which thrives in the soil and water of tropical regions like Southeast Asia and Australia, is the cause of melioidosis, a disease that can infect humans through direct contact with contaminated environments or through the ingestion of or contact with infected animals.

Two aspects of this disease make it a concern to researchers like Blackburn. For one, waterborne diseases can spread quickly if communities are unprepared. A single compromised water source could lead to extensive outbreaks, given our essential dependence on water for drinking and agriculture. Secondly, the pathogen's emergence in regions outside its usual domain — marked by the first U.S. report in Mississippi in 2022, as noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — signals a troubling expansion.

Blackburn hopes that understanding the disease better will help us fight it, wherever it appears. His team employs several strategies to get a full profile of the bacteria, using geospatial mapping to measure its prevalence in its home regions and identify its largest vectors, sequencing its genome, and measuring its drug resistance. Blackburn aims to use this profile to develop a dataset useful for informing policy on disease intensity in the country.

“When we know such information, we can better inform surveillance and diagnostic efforts and educate health workers and the public ahead of outbreak seasons,” Blackburn explained.

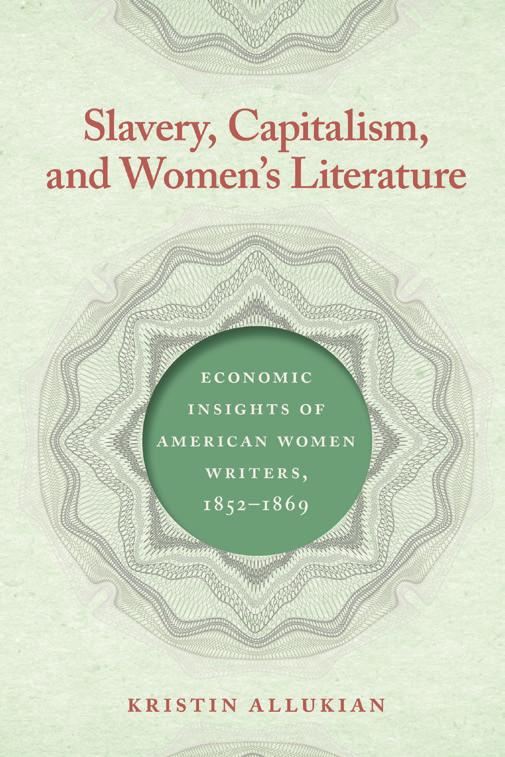

SADIE RYAN also works to bridge the gap between climate science and public health. With a strong foundation in environmental science and disease ecology, Ryan has dedicated her career to unraveling how shifting climate patterns impact the spread of infectious diseases, particularly those transmitted by vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks.

DISCOVER NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

Ryan takes an active stance in informing public health planning and policy. Her research investigates how disease outbreaks can be better controlled, effectively shaping how we manage infectious disease risks.

“It is important to develop projections of how climate-sensitive infectious diseases, such as vectorborne diseases, are anticipated to shift on the landscape and change seasons of suitability,” Ryan said. “Will malaria seasons get longer in this region? Will more cities see invasions of mosquitoes previously assumed to be tropical? Tools to communicate these model outputs and inform health decisions will help us prepare and adapt in a rapidly changing world.”

As the planet warms, her studies emphasize the critical synergy between climate change, population dynamics, and disease, demanding comprehensive strategies that incorporate demographic shifts and climate models into future disease risk assessments. Ryan’s findings offer a roadmap for future research and policy development, underscoring the necessity for governments and policymakers worldwide to proactively address the evolving challenges that climate change presents to public health.

As an anthropologist, geographer, and Earth system scientist, NICOLAS GAUTHIER is dedicated to deciphering the complex relationships that exist across various times and places. His work explores how historical events such as floods or drought can trigger a cascade of effects such as migration, ecological instability, and disease spread, which may not surface until decades later.

Gauthier advocates a holistic approach that underscores the

interconnectedness of environmental factors and human activities, emphasizing the need for integrated solutions. He currently leads a collaborative study with GABRIELA HAMERLINCK, investigating the enduring interplay between climate variability and the spread of infectious diseases, using the Black Death as their case study.

“By integrating historical and archaeological data on plague outbreaks with reconstructed temperature and rainfall patterns, we aim to determine whether specific climatic anomalies, such as droughts or floods in one region, can predict disease outbreaks in other regions,” he said. “This approach helps us to understand how long-term climate trends may influence disease dynamics across different geographical areas.”

Gauthier stresses the importance of a global perspective when thinking about water. There’s a fundamental interconnectedness to our water systems, he said.

“Events halfway around the world, like shifting ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific, can have profound effects on weather patterns here in Florida,” he said. “This interconnectedness underscores how actions in one area can affect conditions in another — what is dumped into a river upstream, for example, directly impacts those living downstream.”

It’s a lesson that hits home for Gauthier, who has spent much of his life in the deserts of California and Arizona. Now, a new resident of Florida, he’s eager to shift his focus to the Sunshine State, where the issue is often too much water rather than not enough. Gauthier is confident that history has much to teach us here.

He points to Florida’s ancient Indigenous Calusa people, who crafted advanced strategies for shaping their environment. This society sustained itself on marine resources and constructed shellmade structures and artificial islands, demonstrating their skills in sustainable water management.

“They were adept at sustainably manipulating local water systems to suit their needs — skills that are invaluable for addressing contemporary challenges like sea level rise and hurricanes,” he said.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 25

Jason Blackburn

Sadie Ryan

Nicolas Gauthier

Charting the future

Each year 80-90 tropical cyclones form over most of the Earth’s tropical and subtropical oceans, carrying with them extreme wind speeds and rainfall that can trigger floods. Due to climate change, these events have become more severe and more erratic in recent years, a serious issue for those living in coastal and inland areas.

For Professor of Geography CORENE MATYAS, there is beauty to these storms. They were fascinated by how the storms showed up on weather radars and in satellite images; mesmerized by the swirl of clouds and the shapes of their rain patterns.

“At the age of 4, I realized that one cannot hide from severe weather events,” Matyas said. “Consequently, I vowed to learn everything that I could about hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and other natural disasters so I could be prepared when severe weather struck.”

Matyas’ interests in weather and the visual arts connected at UF, where they have spent years studying the rainfall patterns of tropical cyclones and now create sculptures to communicate information about the climate system. They hope that studying these patterns will help us better understand the mechanisms of these storms, and thus

improve our detection and protection capabilities. Currently, Matyas is leading a project that aims to do just that, mapping out storms from the past decade in different moisture regions to analyze how a region’s “wetness” can impact a storm’s wind and rain fields.

Matyas, alongside postdoctoral fellow DASOL KIM, has also experimented with artificial intelligence (AI) in their research. Like many fields at UF, AI has incredible potential in the Department of Geography, and many have long embraced the technology for its speed and efficiency. Matyas is currently working on projects that use AI to examine the variability of rainfall in and moisture surrounding tropical cyclones with the goal of analyzing more than 20 years of storms in the Atlantic Basin. Matyas found six typical rainfall patterns for tropical storms and hurricanes and four typical moisture

patterns for hurricanes. These are associated with other variables such as wind shear, storm intensity, and sea surface temperatures, which would otherwise be a monumental task without AI’s speed.

Assistant Professor of Geography BERRY WEN has also been at the forefront of integrating AI into weather prediction systems since she arrived at UF in 2022. Among extreme weather events, Wen focuses on tornadoes, which pose significant challenges due to their rapid formation. She leverages AI and deep learning techniques to develop detection systems capable of quickly identifying conditions that lead to tornadoes, aiming to improve warning times for public safety. However, Wen and her peers face the “black box” challenge with AI, where the internal processing details of AI systems remain obscure. Deep

DISCOVER 26 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

“If you think of almost any problem that’s facing the world, it’s spatial … If you aren’t looking at that spatial component, you’re missing so much of what’s going on.”

— JANE SOUTHWORTH

symbolic learning (DSL), a branch of AI, represents knowledge with symbols for clearer, interpretable explanations of its decisions. Wen applies DSL to tornado forecasting, focusing on the relationship between tornado occurrence and predictors like thermodynamic conditions and radar data. Their research shows DSL-based models outperform traditional tornado prediction indexes, offering a more transparent and accurate approach to tornado detection.

Beyond her AI work on tornado detection, Wen is also investigating droughts. Recognizing the devastation caused by prolonged dry spells, she analyzes precipitation and satellite data to gain insights into their causes. Through her research, Wen seeks to unravel the meteorological and physical drivers of droughts to improve seasonal rainfall predictions. Her ultimate objective is to advance drought detection techniques, enabling communities to better anticipate, prepare for, and mitigate the harms of these increasingly severe events.

JANE SOUTHWORTH, the department chair who recounted her experiences with flooding last summer, has been leveraging AI tools to explore climate-induced ecological shifts in South Africa’s vineyards. With a laugh, she admits that her visits to vineyard owners, often starting with the sampling of the wines, is hardly what you’d call a “tough gig.” But her task is profound. Every glass has a backstory of climatic subtleties, a narrative that Southworth is unraveling through her research.

Over recent years, her collaborative work with vineyard owners across South Africa has involved using machine learning to analyze 30 years of land cover changes. This research helps link observational data from vineyard managers with actual changes recorded via remote sensing technologies. Recently, some vineyards have been diversifying their crops or abandoning areas due to environmental stress.

Immersed in an environment where every drop counts, Southworth notes that dryland ecosystems — those delicate balances of soil and water that support most of the global agricultural output — are at the mercy of rainfall.

“Dryland ecosystems are where all your main agricultural systems and where about 50% of the world’s people live,” she said. “It all comes back to water.”

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 27

ake a deep dive into UF Geography GEOG.UFL.EDU

T

Watercolor. @ Liliia/Adobe Stock.

Oasis in the Desert

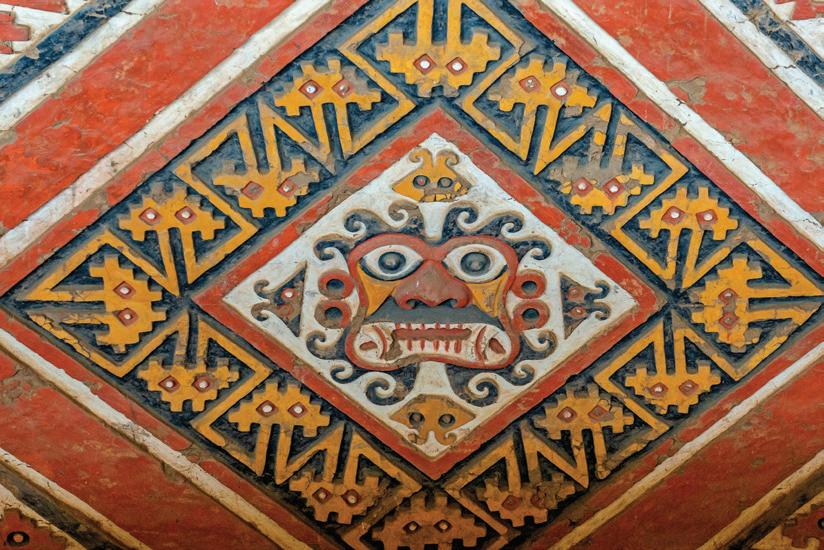

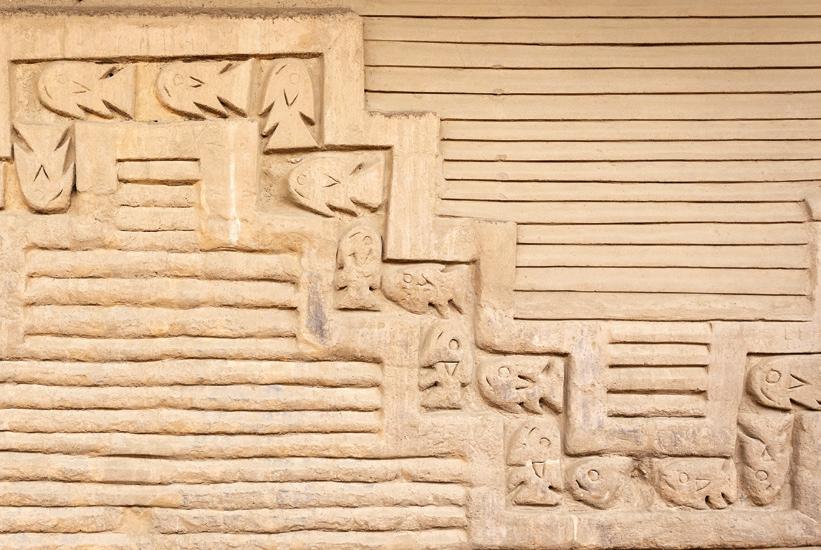

The Chimú civilization’s quest to harness the lifeline of the desert offers modern lessons

By Brian Smith

On the sun-kissed western coast of South America, nestled in modern-day Peru’s northern expanse, lies a mesmerizing testament to human ingenuity and the resilience of a oncemighty civilization. Around 900

A.D., this area was the home to the Chimú people and their Kingdom of Chimor, the second-largest empire in ancient Andean history. For over 500 years, the Chimú’s innovative spirit and technological prowess allowed them to transform the desert into a thriving oasis.

Despite succumbing to an eventual Incan conquest, the ruins of the Chimú endure, drawing global interest.

Archaeologist GABRIEL PRIETO has dedicated nearly a decade to studying the Chimú people, fascinated with their relationship with the environment.

Prieto’s quest is to expand our knowledge of the development of early civilizations and dispel the myth that Indigenous people in the Americas were less advanced than their

European and Asian counterparts. To that end, his work has uncovered a deluge of evidence that the Chimú were adept architects, farmers, and seafarers; some of their achievements rival and even surpass European advancements of the time.

The story of the Chimú and their efforts to control the water in their surroundings reflects humanity’s enduring and complex relationship with water. Like the Chimú, we are always trying to understand this precious resource and maximize our use of it.

“Chimú society valued water and invested countless resources to improve water quality and efficiency, both for their benefit and the environment,” Prieto said. “It was also clear that they were aware of the almighty power and destructive effects of water. Yet amazingly, they learned to not only cope with their situation but to take advantage of it, for the benefit of their society.”

DISCOVER

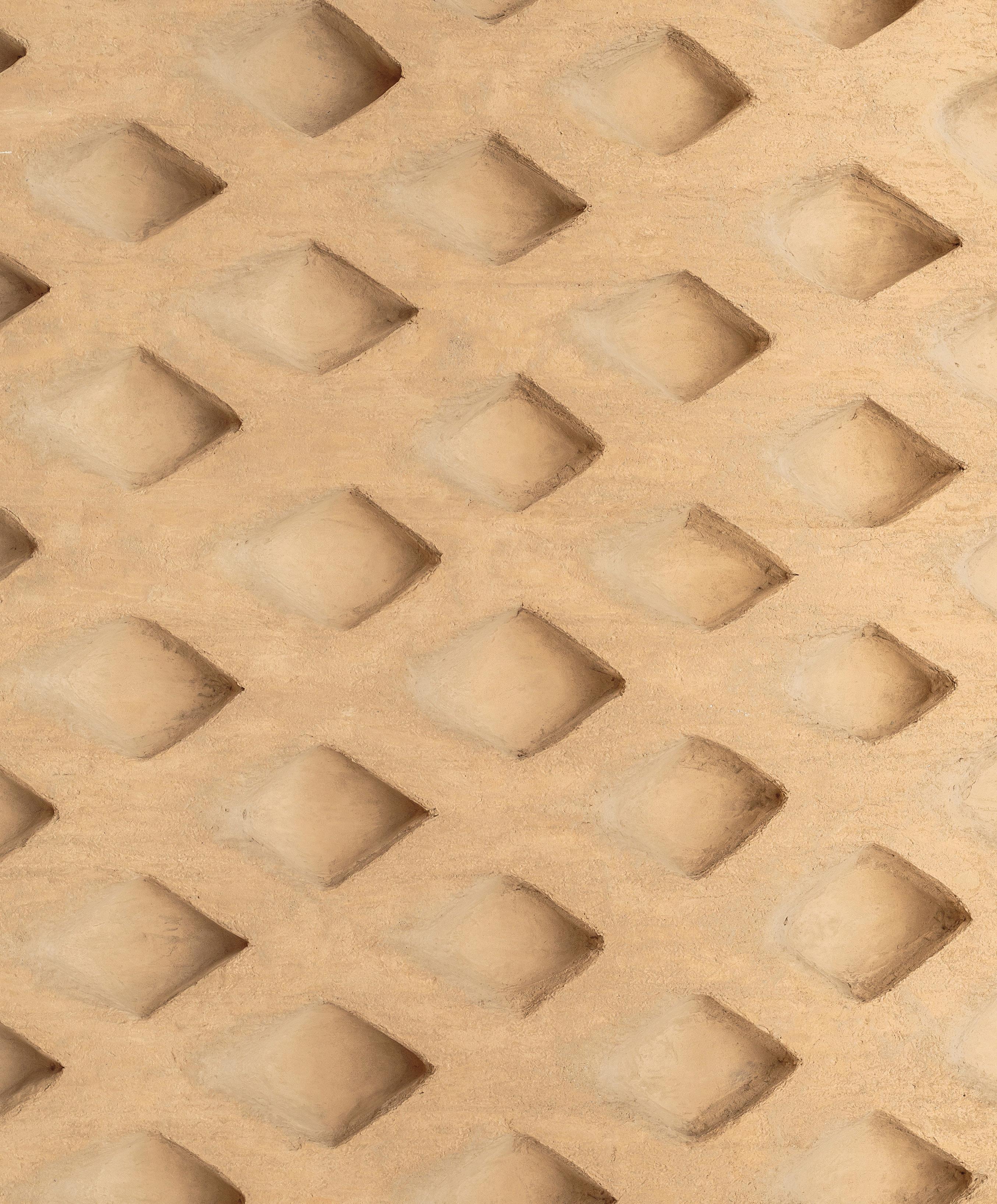

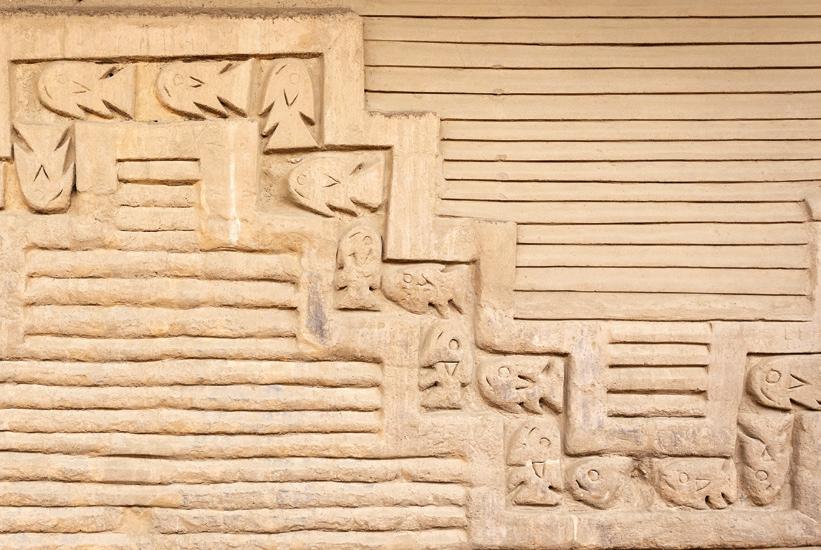

IMPRESSIVE INFRASTRUCTURE

What sets the Chimú’s rise to prominence apart is their defiance of the limitations posed by their surroundings to build their oasis in the desert. The engineering feats they accomplished highlight their ingenuity, particularly in their resourceful use of limited freshwater sources.

The biggest challenge faced by the Chimú was sustaining their massive population, estimated to have peaked somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 people in their capital city alone. Farming in the desert is no easy feat, yet evidence suggests the Chimú were able to maintain vast farms, producing more food than

even those living in Peru today. To harness water for their agricultural pursuits, the Chimú built complex irrigation canals and aqueducts to bring water up from the surrounding valleys. These aqueducts sometimes spanned considerable distances, the longest covering over 50 miles.

“At the time, they rivaled the famous Roman aqueducts in terms of size and distance, and many are not only standing today, but still in use,” Prieto said.

To protect against seasonal flooding, the Chimú built the Muralla La Cumbre, an 8-foot-tall, 6-mile-long wall that stretched along two dried riverbeds. Prieto’s findings suggest that these usually dry ravines would flood during rainy seasons and threaten the farmlands along the western edge

of the civilization, so the wall was erected to repel the excess water.

“We also found that there were large build-ups of sediments along the outside of the wall, and found those same sediments in layers of soil in their ancient farmlands,” Prieto said. “Our theory is that after the floods subsided, they collected these nutrient-rich sediments and used them as fertilizer for their farms.”

The Chimú were also astute in their crop selection, opting for varieties that required minimal water to grow. These included corn, beans, squash, and chile peppers, which continue to be staple crops in the region today.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 29

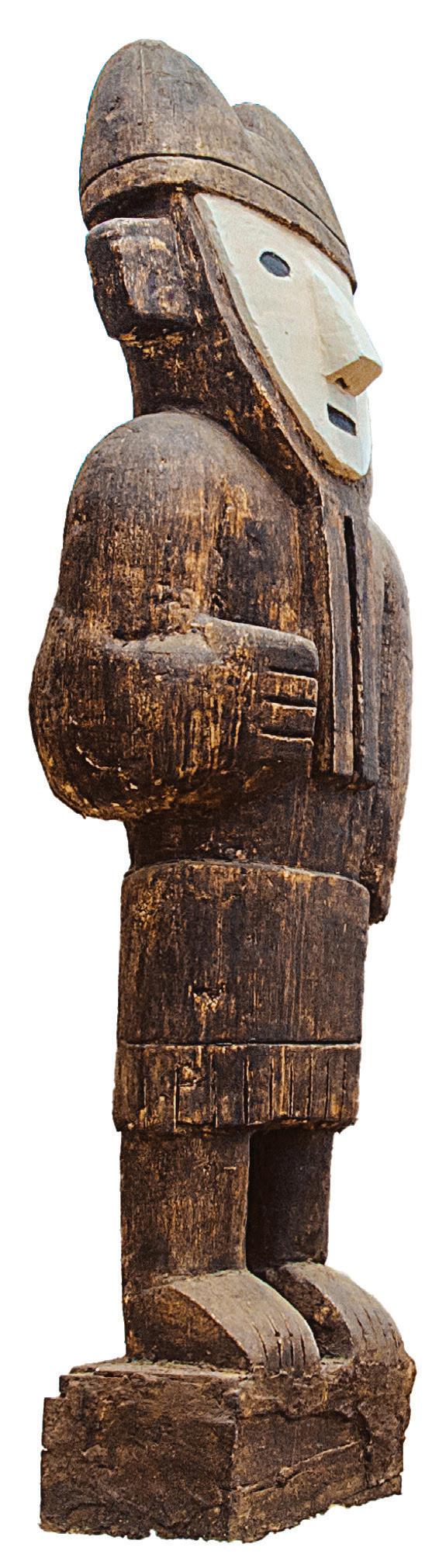

Citadel of Chan Chan. @ Creative Pixels/Adobe Stock.

Top: A field of reeds near the Chimú capital of Chan Chan. @ Rafal Cichawa/Adobe Stock. Above, left to right: Chan Chan water reservoir. @ christian vinces; Aerial view of excavation sites near Trujillo. Photo courtesy of Gabriel Prieto; Chan Chan ruins. @ yoshi/Adobe Stock.

FROM MEAT TO MYTH

While the Chimú people boasted one of the largest civilizations in the region, they were not the first to settle those lands. Evidence suggests that there were people living there before the Chimú, albeit in a much smaller capacity. These people, who began living in the region about 3,200 years ago, are believed to be ancestors or precursors to the Chimú. Like their descendants, they appear to have had advanced technologies for their time.

Several sites belonging to those precursors have been found, and Prieto and his fellow excavators made another intriguing find in some of them: shark teeth. While the presence of coastal shark species was expected, what surprised the researchers were the teeth belonging to pelagic species, or sharks that roam open ocean waters, like the blue shark and even the great white shark.

“Finding the remains of these pelagic sharks has made us reconsider what we know about the naval capabilities of the Chimú predecessors,” Prieto explained. “In order to hunt these fish, they must have had sturdy boats and some form of advanced navigation, which is impressive considering these technologies were still in their early phases over in Europe.”

Prieto believes that there was an evolution of the cultural significance of sharks as their society developed. The earliest shark remains were found grouped together haphazardly in what were believed to be trash pits, but newer specimens were found in temples and tombs. This suggests that as millennia passed, sharks became less of a staple food and more of a class or religious symbol.

The Chimú were aware of the almighty power and destructive effects of water. Yet amazingly, they learned to not only cope with their situation but to take advantage of it.

Background: Close-up of the walls in Chan Chan @ christian vinces/Adobe Stock. Inset: Detail of Tschudi Palace frieze depicting fish @ Maurizio De Mattei/Adobe Stock.

THE FURY OF EL NIÑO

For all their technological advances and mastery of engineering, the Chimú people struggled with the same problem we face today: Try as we might to bend nature to our will, we can’t control the weather; we can merely shield ourselves from it. Despite constructing aqueducts to combat floods and redirect water, the Chimú were defenseless to the extreme weather events we continue to battle today.

El Niño, a cyclical weather phenomenon occurring in the Pacific every three to five years, afflicted the Chimú civilization. In some areas of the Pacific, like California, it causes prolonged dry seasons, but in Peru, it’s quite the opposite. Instead, El Niño brings heavy rainfall and wetter, cooler conditions, sometimes leading to floods and cataclysmic storms. In recent years, these events have become more frequent and extreme due to climate change, but historical records document several particularly severe El Niño events.

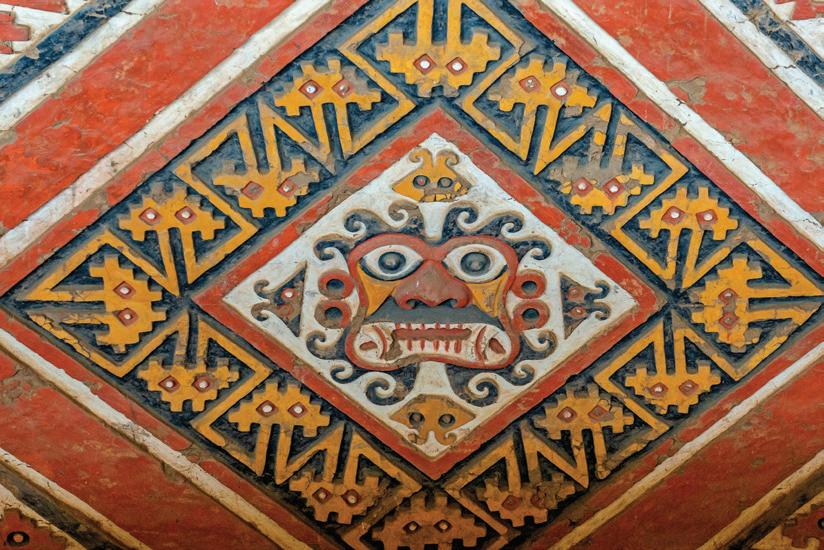

This posed a problem for the Chimú people, who turned to their faith in those times of crisis. They believed that their gods had sent the storm because they were angry, and they believed that they could appease their gods to calm the rain and wind.

“Most of their rituals and ceremonial events were related to sacralizing water and its sources,” Prieto explained. “They considered the mountains the keepers of water sources, although others believed the sea was the mother of all water sources.”

Their deification of the waters around them was also reflected in their art. Many woven textiles have

been unearthed at Chimú sites, and the patterns woven into some of them seem to represent the spirals and waves of the ocean, while others appear to represent their canals and agriculture fields. “We believe these patterns emphasize the importance of water in their cosmovision system,” Prieto said.

Sacrificial rituals held profound significance in ancient South American religions, and the Chimú were no different. Prieto uncovered the aftermath of these sacrifices and many like them, finding mass burial sites in temples and coastal shrines throughout the littoral of the Moche Valley. At one such site near the Chimor capital of Chan Chan, excavators found the remains of 269 boys and girls, aged between 5 and 14, along with the bones of dozens of llamas curled alongside them. Through radiocarbon analysis, the remains found at this site, named Huanchaquito-Las Llamas, were dated back to approximately A.D. 1400. “Records suggest that there was a particularly bad El Niño season around this time, and we found layers of dried mud around the site, suggesting that these sacrifices took place in the rain,” Prieto explained. “Our working theory is that in order to calm the weather, the Chimú believed they had to sacrifice that which was most important to them: their children.”

The Chimú’s attempt to navigate the wrath of El Niño serves as a haunting reminder of our own vulnerability in the face of nature’s furies. As Prieto exposes more of their history, we are compelled to confront our own delicate balance between faith, sacrifice, and the fundamental drive to forge a path amid the relentless tempests of existence.

YTORI SPRING / SUMMER 2024 | 31

A painting depicting Ai Apaec, a principal deity of the Moche, precursors to the Chimú. @ SLPhotography/Adobe Stock.

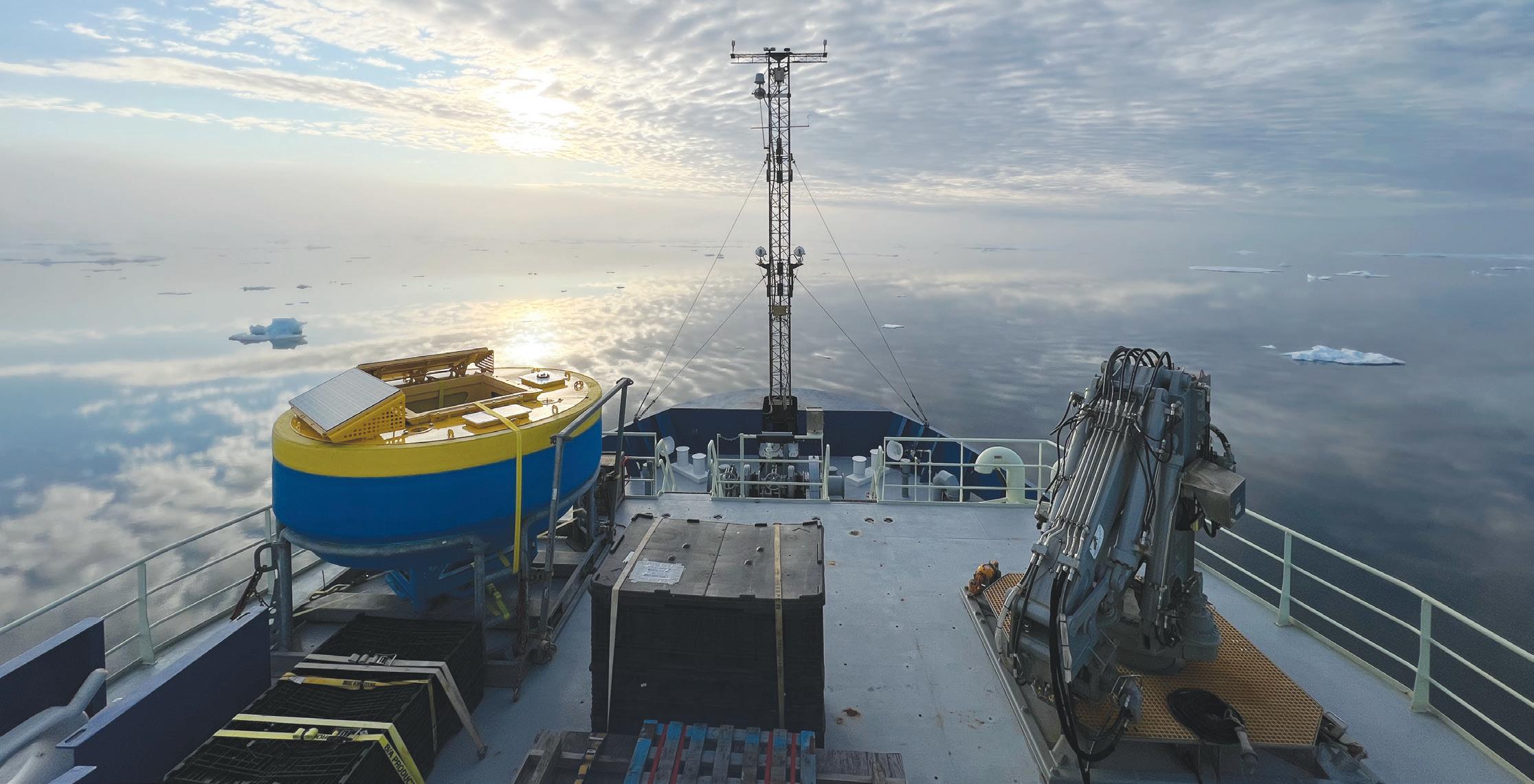

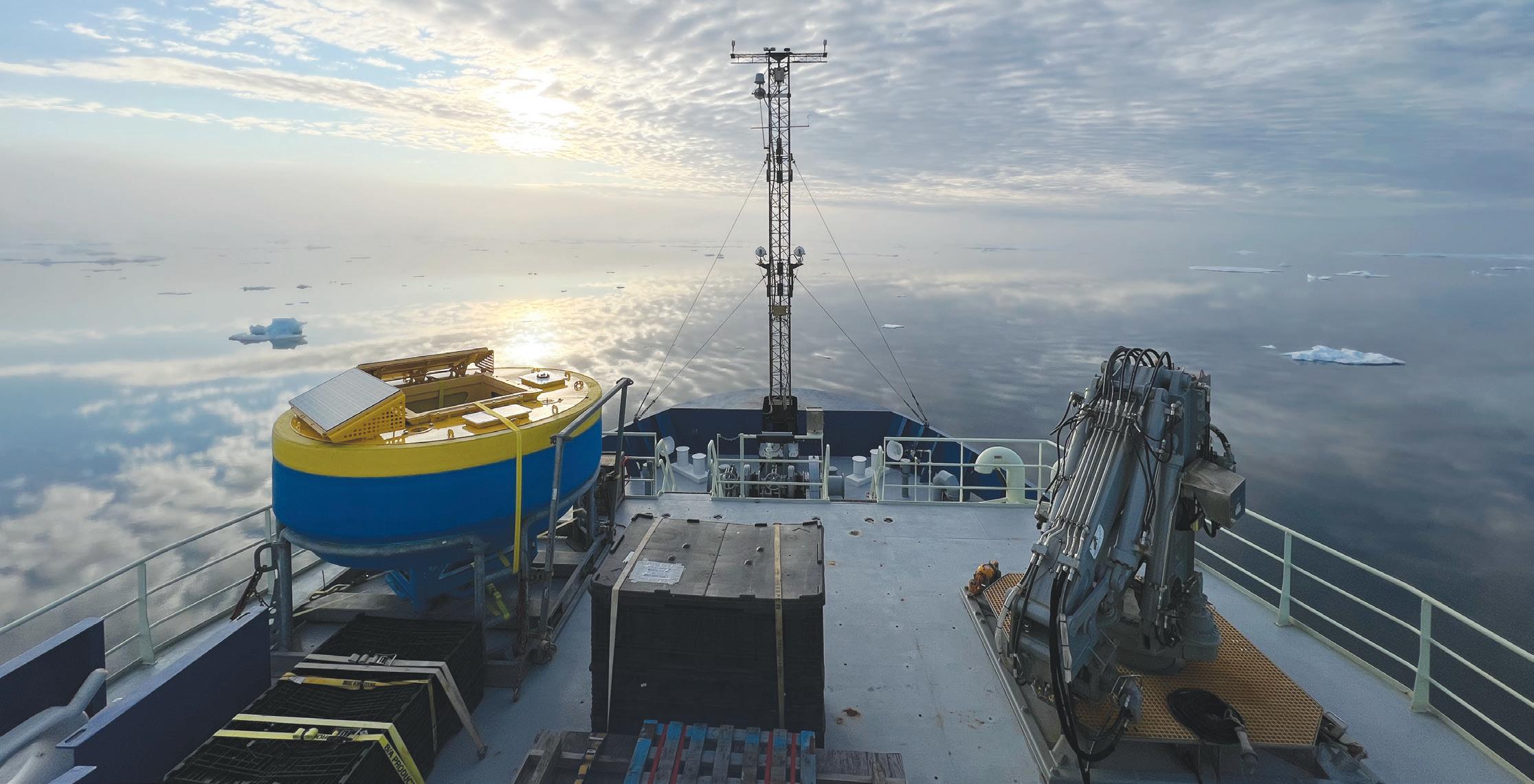

Glacial Features

By Lauren Barnett

A science expedition to Greenland’s ice sheets takes center stage

Greenland, with its expansive ice sheets and remote wilderness, may seem worlds away. But this far-flung landscape harbors valuable insights into the future of life on Earth, making it relevant to each of us.

A new short documentary film, “The Baffin Bay Deglacial Experiment,” brings this distant world closer. Viewers venture aboard a massive United States Navy-owned research vessel, the R/V Neil Armstrong, to follow a team of interdisciplinary scientists, including University of Florida paleomagnetist and geological

oceanographer ROB HATFIELD, during their monthlong expedition at sea. The film goes behind the scenes as the science party investigates the frigid depths of Baffin Bay, off the west coast of Greenland.

Central to the icy expedition is an ambitious objective of retrieving ocean mud from depths of up to 5,000 feet of water. The mud holds a historical record of Earth’s last deglaciation period, around 17,000 years ago. During this period, the western margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet destabilized and rapidly retreated, but the reasons for this swift occurrence remain shrouded in mystery.

By analyzing the sediment composition and the geochemistry of animal shells within, the research team hopes to gain insights into the longterm interaction between the ocean

and ice sheets, ultimately forming a broader view of the Earth’s system.

As chief scientist on the project, Hatfield works tirelessly to uncover the untold stories hidden within the seafloor, a complex and delicate task. The documentary provides a window into the team’s cuttingedge research, which involves using geophysics to image the seafloor and employing specialized tools to extract sediment samples with precision.

It’s a taxing trip, but the scientists hope to help us answer pressing questions for our future: How fast did the ice melt? How quickly did the sea level change? Did the ice sheets disintegrate quickly or resist change? What does all of this say about our remaining ice sheets?

The film has garnered attention at global film festivals, winning

CONNECT 32 | COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES NEWS.CLAS.UFL.EDU

All photos courtesy of Rob Hatfield.

“Climate Action Film” at the Arctic Film Festival in Svalbard. It has been selected for over half a dozen other science film festivals as of the date of this publication.

“I think films like this can help humanize scientific research,” Hatfield said. “Often, we hear about climate change through quantitative statistics, projections for decades out, or quotable sound bites. I think it’s important to show not only how work is done, but also the people doing it.”

The science party was staffed with early-career researchers, bringing fresh perspectives to the work. Over half of the science party identified as female — a key aspect of this project, especially for a field that has historically excluded women, Hatfield emphasized.

The project, a collaboration between five institutions led by UF, included 21 scientists and 20 crew members working in 12-hour shifts over 33 days at sea. The researchers brought expertise spanning geophysics, paleoceanography, paleomagnetism, sedimentology, geochronology, and ice sheet history and behavior.

“The rewarding part of this work is being able to draw together a team of people with different specialties and address a big problem,” he said. “Not one person could answer the question alone.”

Hatfield brought along two of his doctoral students, PALOMA OLARTE and LINDSEY MONITO, but they weren’t the only Gators on board. Film director GEORG KOSZULINSKI (BA '03, MA '11) is a double graduate of UF’s film studies program, while co-principal investigator JOSEPH STONER (BS '87, MS '91), now a professor at Oregon State University, studied geology at UF.

While the voyage has concluded, its legacy endures through the film

and the preservation of archived samples collected. Within the layers of sediment, a narrative emerges about climate change. Like tree rings, these samples can be dated, offering a glimpse into bygone days.

“How we archive these samples is almost as important as how we recover them,” Hatfield said.

Preservation efforts are crucial for scientists to reconstruct the planet’s climate history. Hatfield wants to know the implications of an entire ice sheet collapse and the ocean’s role in such a scenario. Each melt, crack, and break of the ice signals an urgency to persist in the arduous work of unraveling the secrets within these samples. The Greenland Ice Sheet, if completely melted, could cause a 24-foot sea level rise and trigger a series of catastrophic events. This has significant implications for billions of people worldwide, particularly those in coastal communities.