Social Social Social Justice Justice Justice wanted wanted wanted

2022–2023

The University of Georgia School of Social Work’s primary focus on social justice and diversity, equity, and inclusion in leadership, research, and teaching serve as the organizing principles for all aspects of our programs to train social workers for the 21st Century.

Our mission is to prepare “culturally responsive practitioners and scholars to be leaders in addressing social problems and promoting social justice, locally and globally, through teaching, research, and service.” And our work is guided by the NASW Code of Ethics to advance knowledge, skills, and values of future social workers.

– Dean Philip Hong

OF

WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU ii

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL

SOCIAL

iii FACULTY STATEMENT ON SOCIAL JUSTICE ......... iv Social Justice Wanted Introduction Philip Hong .............................................................1 THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK RESPONDS TO: CIVIL RIGHTS AI, Its Promise and Perils, and Civil Rights Llewellyn Cornelius 5 RURAL COMMUNITY WELL-BEING Stress, Disparities, and Support for the Farmer Anna Scheyett 8

To Build a Better World: Now is the Time for a Rights-Based Approach to Social Work Practice Jane McPherson 12 TRAUMA Trauma-Informed Work with Native Trafficking Survivors Kate Morrissey Stahl 16 Utilizing Trauma-Informed Perinatal Care to Address Birth Trauma and Improve Outcomes Sarah Gormley ..................................................... 19 TABLE OF CONTENTS SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 RACISM School of Social Work Statement on Racism and Social Justice ............................................... 21 Social Justice Common Book Initiative, Tiffany

Elkins ..................... 22 A Letter to Resistance, and Reflections of a New World Joy Green .............................................................24

To Have a Collective Future, the Time to Act is Now Amelia A. Mahan 27 PrOSEADTM Syllabus 30

Communications :

Sam Cook, Kat

Design/Production: Kat

Copy

Peter Frey,

Dot

The

of Georgia does not discriminate

race, sex,

color

or ethnic

sexual

gender

service

its

activities; its

loan

HUMAN RIGHTS

Washington, Jennifer

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022-2023 Dean: Philip Hong

Jennifer Abbott,

Farlowe, Johnathan McGinty

Farlowe

Editor: Johnathan McGinty UGA Photographic Services-Nancy Evelyn,

Dorothy Kozlowski, Robert Newcomb, Chad Osburn,

Paul, Andrew Davis Tucker; UGA School of Social Work-Laurie Anderson; Adobe Stock Images © 2022 University of Georgia School of Social Work

University

on the basis of

religion,

national

origin, age, disability,

orientation,

identity, genetic information, or military

in

administrations of educational policies, programs, or

admissions policies; scholarship and

programs; athletic or other University-administered programs; or employment. Inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Equal Opportunity Office, 119 Holmes-Hunter Academic Building, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602. Telephone 706-542-7912 (V/TDD). Fax 706-542-2822. https://eoo.uga.edu.

University of Georgia School of Social Work

FACULTY STATEMENT ON SOCIAL JUSTICE

Developed through a collaborative and synthetic faculty discussion process.

At the UGA School of Social Work, we believe social justice occurs when systems of all sizes (individuals, families, communities) are able, safely and dependably, to obtain the civil and human rights and resources they need to thrive. These include but are not limited to health, economic growth, social rights, equity, inclusion, safety, freedom to move about the world; social support, food security, a clean environment, education, employment, childcare and housing. Eliminating social injustice is central to our work as social workers, requires brave and assertive action and effort, and must be present in all we do and say. The School of Social Work advocates for social justice by fighting for the rights of people and communities, particularly those who have experienced marginalization, stigma, discrimination, and oppression of any form. We partner with communities in Georgia and around the world to embrace and speak truth to power and privilege and to promote change for social justice in our classrooms, our research, and our service.

Approved unanimously by the faculty of the School of Social Work, September 15, 2017

OF

OF

WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU IV

UNIVERSITY

GEORGIA SCHOOL

SOCIAL

INTRODUCTION: SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED

Philip Hong, PhD, LCSW Dean and Professor

Social justice is the social work profession’s foundational organizing value. The University of Georgia School of Social Work (UGA SSW) has a primary focus on social justice and equity, diversity, and inclusion in leadership, research, and teaching, and centers them as the organizing principles for all aspects of our programs to train social workers for the 21st Century. I am most honored to join the UGA SSW community as the new Dean, and to be part of its mission of “preparing culturally responsive practitioners and scholars to be leaders in addressing social problems and promoting social justice, locally and globally, through teaching, research, and service.” Our community is collectively advancing this mission at UGA, and I hope to build upon our legacies with a spirit of “social innovation” that is rooted in community-engaged social justice research. This endeavor requires a collaborative journey between the UGA SSW, its internal and external resources, community partners, and supporters, that will carry the torch of purposedriven, community-engaged, and socially responsible education and research into an age of ‘social innovation for the greater good.’

According to the Stanford Center for Social Innovation, “social innovation is the process of developing and deploying effective solutions to challenging and often systemic social and environmental issues in support of social progress.” Social innovation originates from the spirit of human-centered values and collaborative relationships. It is my hope to learn from and walk hand-in-hand with the UGA SSW students, staff, faculty, and alums to serve the community of Athens, Georgia, and communities around the globe using our expertise, skills, values, research, and practice, and witness on-the-ground a post-COVID, more racially equitable and socially just world. I would like to support UGA SSW to bring out its best, through relationships based on authenticity, humility, empathy, and unity under a shared vision to advance our social justice mission for the wellbeing of our community.

Social justice is often cited as our professional mission, but without a common definition. In my earlier work with a colleague, we developed a bottom-up articulation of the concept of social justice by surveying and reviewing course syllabi in MSW programs from around the country

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 1

Introduction:SocialJusticeWanted – Philip Hong

Introduction:SocialJusticeWanted

(Hong & Hodge, 2009). We presented the following summary definition of social justice: Based on the professional values of social work, social justice is a process of action to “do justice” and an outcome of achieving justice-related goals and overcoming injustices, particularly for vulnerable groups in society. Four key dimensions are reflected in this statement: professional values, process, outcomes, and population. Professional values are supported by social work’s ethics, supplemented by personal passion, spirituality, and self-awareness in understanding what roles one might take to promote social justice. The process of moving toward justice covers the full range of scope, from micro to global, in tandem with actions that challenge existing social and political systems, individual capacities, and family environments. Outcomes relates to making progress in the areas of economic and political justice, social welfare, human rights, and diversity/social inclusion. Population includes all people in general, but with a particular focus on vulnerable

groups who lack power and representation in society.

As such, calling to social and economic justice requires augmenting diversity, equity, multiculturalism, and social inclusion, and undoing of systemic and institutional racism, oppression, and other forms of social exclusion. It is my unfinished, evolving, but best up-todate understanding that diversity has to do with existence or physical presence of many forms of differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, socioeconomic status, nationality, citizenship status, language, (dis) ability, religion, political affiliations, etc. Increasing diversity is an important step forward, but the next step of promoting equity is essential for diversity to become more meaningful. Equity is about promoting fair institutional procedures and processes to tackle the root causes of disparities in resource allocation and system-generated outcomes faced by people who identify with diverse identities.

Dean Philip Hong delivers the keynote address at the UGA 2022 Embracing Diversity ceremony in Athens, GA. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski)

– Philip Hong

Intersectionality provides a theoretical understanding of how social categorizations and identities overlap and intersect within a system of discrimination and oppression to affect behaviors (Crenshaw, 2013). Disadvantages in one area overlap or intersect with others—including financial deprivation, poor health, lack of access to resources, and social stigmatization—and add to the comprehensive vulnerability in the marketplace (Saatcioglu & Corus, 2014). Inclusion is the sustainable outcome reached as the result of promoting equity, not only so that diversity is valued, respected, and desired, but also so that people from diverse backgrounds feel truly welcomed and appreciated as fully participating members in decision making without fear.

Trust and courage are the foundational principles for strengthening a participantcentered, student-centered, staff-centered, and faculty-centered culture of inclusion at UGA SSW. ‘For service is to pursue scholarly (teaching and research) impact’ can provide the roadmap for SSW to lead by actions, because words cannot adequately compensate for structurally generated injustices, oppression, and exclusions. Walking the walk (and the talk), in the form of Paulo Freirian praxis (reflection and action directed at the structures to be transformed), will be the hallmark of earning trust from the community, students, staff, and faculty who make up the diverse UGA SSW community. Speaking truth to power in accompaniment with and for the most vulnerable populations will highlight the ‘courage’ that UGA SSW needs to provide vocational meaning as learners, supporters, advocates, teachers, researchers, activists, and allies.

These are qualities that will raise critical attention to diversity, equity, social/

economic inclusion, belonging, and community engagement, and will build the organizational culture needed to celebrate what makes UGA SSW a leading program of social justice. Founded on an inclusive diversity culture secured by trust and courage, UGA SSW can lead a non-elitist, non-colonial, non-judgmental practiceresearch integration that defines the future design thinking and social innovation of the 21st Century. At the heart of this will be the community-endorsed and participantsupported narrative change that practiceresearch integration will support in telling an empowerment-based story of community strength and resilience. This could be the signature contribution that the UGA SSW community makes together for social justice in the coming decades for future social workers, local communities, the State of Georgia, the nation, and our global village. • references:

Crenshaw, K. (2013). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In K. T. Bartlett & R. Kennedy (Eds.), Feminist legal theories: Readings in law and gender (pp. 23-51). Routledge.

Hong, P. Y. P., & Hodge, D. R. (2009). Understanding social justice in social work: A content analysis of course syllabi. Families in Society, 90(2), 212-219.

Saatcioglu, B., & Corus, C. (2014). Poverty and intersectionality: A multidimensional look into the lives of the impoverished. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(2), 122-132.

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 3

Introduction:SocialJusticeWanted – Philip Hong

The Center for Social Justice, Human and Civil Rights works with university and community partners to foster a fair and inclusive society. Founded in 2013, it brings attention to historic civil and human rights struggles, encourages scholarship that examines oppression and inequality, sponsors educational events and mentors future social justice leaders.

Through all its endeavors, the Center seeks thoughtful examination of community-engaged social change.

Photo by Laurie Anderson

Photo by Laurie Anderson

AI, ITS PROMISE AND PERILS, AND CIVIL RIGHTS

Llewellyn Cornelius, PhD, LCSW Donald L. Hollowell Distinguished Professor of Social Justice and Civil Rights Studies Director, Center for Social Justice, Human, and Civil Rights

We live in a world where yesterday’s science fiction is quickly becoming reality. Rapid gains in technology and artificial intelligence are helping shape our society and how we interact with our government, companies and each other.

Earlier this year, Shalini Kantayya joined me for our Donald Hollowell Lecture to discuss everything she learned making her Netflix documentary, Coded Bias. This seminal film focuses on the way in which algorithms in video recognition software can lead to racial/ ethnic bias. It asks how we can engage in civil rights in the 21st century in a way that balances ethics in the use of AI applications for human services.

As we think about the widespread use of AI and other invasive technologies already in our society, we must consider the larger issue of social justice. We know groups like Cambridge Analytica and the Facebook Experiment have used social media to influence consumer behavior. How can we monitor the fair use of technology for the benefit of all citizens?

How AI Acts as a Gatekeeper

In talking with Shalini, I learned she became interested in AI after reading Cathy O’Neal’s

2016 book, Weapons of Math Destruction. The book explores how big data algorithms are increasingly used in ways that reinforce preexisting inequality.

AI and big data already decide really important things in our lives, such as who gets hired for a job, who gets pain medication, and even how long a prison sentence someone should serve. We are trusting these machines and systems to govern very important decisions and shape human destinies.

In a sense, we as humans are outsourcing our decision making to machines and algorithms, as machine learning and AI are being used as an invisible decision maker and gatekeeper of opportunity. To make matters worse, the same systems we are putting our faith in haven’t been vetted for racial or gender bias. Too often, these technologies are for surveillance and predatory targeting, or surveillance capitalism.

And we are not often asked clearly if we want any of this. So many of these services are opt-out rather than opt-in. Rights get eroded, and many people don’t know they can stick up for themselves.

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 5

Groups like the nonprofit Algorithmic Justice League (AJL) are raising awareness about the impacts of AI, building the voice and choice of the most impacted communities, and galvanizing researchers, policy makers and industry practitioners to mitigate AI harms and biases.

There is more we can do to shift the AI ecosystem toward a system that is more equitable and accountable.

Balancing Technology and Ethics

Looking down the road, how can we balance technology and ethics?

We know we can’t hold back the technology. It’s already moving fast, and we can’t stop the tide. That may sound a bit dystopian, but it’s also utopic. Tech is amazingly powerful, and AI can help us all thrive.

In her research, Shalini met incredible scholars who opened her mind about many different, exciting uses for AI and emerging technology. Technology can bring so many powerful thinkers together to solve huge problems.

But, so far, we have had a lack of imagination about how emerging tech can be used. This may stem from a lack of inclusion in Silicon Valley. It’s Shalini’s hope there will be more representation – and, as a result, more imagination – in meetings around how we use this tech.

We all need a place at the table because we all interact with these technologies. Knowledge can’t be kept in the hands of the few. Tech literacy is valuable for all of us so we can better understand and question these technologies and how they work.

Shalini is amazed how everyday people are already making a difference. For instance, seven educators and the Houston (Texas) Federation of Teachers settled with the Houston ISD over the district’s use of a secret algorithm that officials used to determine which teachers were evaluated, fired and given bonuses over a five-year period. The system, called the Educational Value Added

Assessment System, or EVAAS, is no longer used by the district.

She can also point to the bigger changes – IBM and Microsoft have changed their policy on selling facial recognition software to police. Facebook has deleted a billion faceprints from its platform. There is cause to believe people are powerful and that these

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 6

companies and agencies will respond when enough people raise their voices.

Data Rights are Human Rights

Shalini’s film and the AJL have a call to action: a proposed universal declaration of data rights as human rights. The declaration calls out AI being used as a gatekeeper to

shouldn’t profit off the limitless use of our data without willful consent.

The declaration calls for a prohibition on collecting biometric and other special categories of personal data without our affirmative consent – especially data that reveals our racial or ethnic origins, political opinions, sexual orientation or religious beliefs – and a moratorium on the use of racially biased and invasive surveillance technologies like facial recognition by all law enforcement agencies.

The argument is that we must democratically determine how these tools are used, and ban uses that breach fundamental civil rights. Algorithmic systems must be vetted for accuracy, bias and non-discrimination, evaluated for harm and capacity for abuse, and subject to continuous scrutiny.

Ultimately, people must be viewed as human beings with inherent value and inalienable civil rights. With this in mind in the times we live in, data rights are fundamental to civil and human rights. •

opportunity in employment, healthcare, housing, education and policing, and it stands up to protect personal liberties and opportunities from being denied by AI.

Our faces and personal information should not be subject to invasive surveillance. Personal data should be processed lawfully, fairly and transparently. Corporations

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 7

The idyllic image of peaceful green fields belies the vulnerabilities and disparities experienced by rural communities. Rural residents face many challenges, including lower household incomes, lower education levels (https:// www.census.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/2016/cb16-210.html), and greater health disparities when compared with urban areas. (Myers, 2019.)

These communities also see significant disparities and high rates of behavioral health disorders. “Deaths of despair,” those due to substance use disorders or suicide, occur more frequently in rural communities (Erwin, 2017).

Rural communities, unfortunately, have multiple barriers to accessing behavioral health care. There is a critical shortage of providers -- 65% of non-metropolitan counties lack even one psychiatrist (Andrilla et al, 2018) and more than 60% of rural areas are designated as Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas (HRSA, 2022.) Even when there are providers in rural areas, travel time and cost of services make behavioral health interventions inaccessible for many, with high rates of underinsurance adding to the challenge of obtaining care.

STRESS, DISPARITIES, AND SUPPORT FOR THE FARMER

Anna Scheyett, PhD, LCSW Professor

Broadband is limited, so tele-health is not a panacea for the challenges of access to services in rural communities. (Becot & Inwood, 2022; Lister, et al., 2020). Finally, stigma around behavioral health services is high in rural communities, where “small town talk” is common, and, combined with the strong sense of self-reliance seen in rural communities, can serve as significant deterrents to help-seeking (Ferris-Day et al. 2021).

For the past several years, my research has focused on the behavioral health challenges faced by rural communities, specifically farmers and farm families. We don’t often think of farmers as a vulnerable population, yet they have the third highest suicide rate among all occupations (Bissen, 2020), have dangerous and isolated working conditions, and their livelihood is at the mercy of weather, input costs, and trade policies that are all out of their control (Scheyett, 2020). Farmers need social work advocacy to address the vulnerabilities and disparities they face, and to ensure they receive behavioral health services in ways that are acceptable and accessible.

My research began in collaboration with colleagues at UGA’s College of Agriculture

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 8

Stress,Disparities,andSupportfortheFarmer – Anna Scheyett

and Cooperative Extension (Extension), using data from the CDC Violent Death Reporting System (VDRS). Using the VDRS, we gathered information on all suicides among farmers and agricultural workers in Georgia for a ten-year period. We found that suicide rates were high and the precipitators for suicide were often heartbreaking — spousal loss, financial stressors, health issues that left farmers unable to work and not wanting to “be a burden” on their families.

The stories of isolated people, mostly older men, who thought their families and their farms would be better off without them, were tragic. One farmer’s last communication was a voicemail to a

neighboring farmer, a last act taking care of his family and his farm … “Please tell my family my wallet is on the mantle, and please take care of my cows.” (Scheyett, et al. 2019)

This work galvanized my commitment to addressing the injustices faced by farmers as they struggle with sometimes overwhelming stress and loss. I have studied farmers’ self-reported stress levels, and found that they are high and increasing (Scheyett, 2020). COVID has only added to this stress. Colleagues and I found that concerns about the emotional impacts of COVID were particularly high in farmers who have the most to lose — those with families, who farm high-risk

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 9

crops, and who don’t know how to access information about mental health. (Scheyett, Shonkweiler, et al., under review).

Given these stressors and risks, how can we help farmers?

As mentioned above, the stigma of seeking behavior health services is particularly high in rural communities, so who will farmers trust and talk with? Our team completed a survey and found that farmers are most likely to confide in spouses, friends, other farmers, and faith leaders (Scheyett, et al., in press). Very few said they would seek professional help. Knowing this, we have been researching and designing interventions that will provide acceptable and accessible support to farmers. We are

embedding these supports within local Extension offices, which are trusted places that farmers visit for many reasons — soil testing, consultation on crop disease, 4-H for their children. Providing support and information on managing high stress and emotional distress through Extension is a non-stigmatizing and acceptable strategy for farmers.

Most recently, we have seen this in play out through an intervention we call the Farmer Stress Production Meetings (Scheyett, Scarrow, et al., under review). At the beginning of each spring, Extension offices hold meetings where farmers come to learn the latest research on the crops they grow. In several counties, Extension agents are providing folders of information on health,

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 10

Anna Scheyett surveys farmers at the Georgia Farm Bureau Convention. (File photo)

stress management, and mental health as part of these meetings. The meetings also include a free blood pressure check, where the provider can talk about the links between blood pressure and stress. Finally, a mental health professional with roots in the local farming community speaks briefly on stress, mental health, and suicide, and provides the Georgia Crisis and Access Line phone number. This information has been well received by farmers, and a number of them have reached out to the mental health provider for more information.

Our research continues, grounded in commitment to creating interventions that are acceptable, that respect the dignity of individuals, and that are grounded in human relationships. The most recent work we have completed is a set of focus groups with farmer spouses, and we plan to use our findings to develop resources for spouses to support their farmers, their families, and themselves during times of stress.

Throughout this piece I have made mention of Extension, the outreach arm of the University for resources about agriculture, nutrition, and family well-being. There is an Extension office in every county in the state, and in my experience, they have been wonderful partners. I would encourage any social worker who wants to reach rural communities to develop a relationship with Extension.

Through my work, I have learned a lot about the struggles, disparities, and injustices experienced by farmers. I hope other social work researchers will engage in this work as well. Anyone who eats food or wears fiber should care deeply about the well-being of farmers and their families. •

references:

Andrilla, C., Patterson, D., Garberson, L., Coulthard, C. & Larson, E. (2018). Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54, 6, Supplement 3, S199-S207. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004

Becot, F. & Inwood, S. (2022). Medical economic vulnerability: A next step in expanding the farm resilience scholarship. Agriculture and Human Values. Online first. DOI 10.1007/s10460-022-10307-4

Bissen, S., (2020). Yes, U.S. farmer suicide is significantly higher than the national average. Organisms: Journal of Biological Sciences, 4, 1, (17-25). DOI: 10.13133/2532-5876/16959.

Erwin, P. (2017). Despair in the American heartland? A focus on rural health. American Journal of Public Health, 107,10, 1533-1534. DOI: 10.2105/ AJPH.2017.304029

Ferris-Day, P., Hoare, K., Wilson, R., Minton, C. & Donaldson, A. (2021). An integrated review of the barriers and facilitators for accessing and engaging with mental health in a rural setting. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30,6, 1525-1538. DOI: 10.1111/inm.12929

Health Research Services Administration. (2022). Health Professional Shortage Areas. Retrieved at https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ shortage-area

Lister, J., Weaver, A., Ellis, J., Himle, J. & Ledgerwood, D. (2020) A systematic review of rural-specific barriers to medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the United States. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 46(3), 273-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00952990.2019.1694536

Myers, C. (2019). Using telehealth to remediate rural mental health and healthcare disparities. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40,3, 233-239. DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2018.1499157

Scheyett, A. (2020). Farmer stress in Georgia: Results of a survey. Athens, GA: Author. https://extension.uga. edu/topic-areas/timely-topics/Rural.html

Scheyett, A., Bayakla, R., Whitaker, M. (2019). Characteristics and contextual stressors in farmer and agricultural work suicides, Georgia, 2008-2015. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 43,61-72. DOI: 10.1037/ rmh0000114

Scheyett, A., Johnson L.P., Bowie, M., Garcia, A. (in press). Who do farmers trust? Identifying farmer support systems during times of stress and suicide risk. Journal of Extension.

Scheyett, A., Kane, S., Shonkweiler, V. (under review). Predictors of emotional distress in farmers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Scheyett, A., Scarrow, A., Dunn, J., Hollifield, S., Shealey, J. & Hayes, B. (under review). The farmer stress production meeting model: Acceptability and feasibility of an intervention.

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 11

Anna Scheyett

Stress,Disparities,andSupportfortheFarmer –

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Arundhati Roy, the Indian novelist and human rights activist, reframed the global state of emergency as a potentially useful rupture in our lives— chaos from which we might build a new and better society:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred… Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it. (Roy, 2020)

Nearly two years into the pandemic, we are not yet walking lightly through this portal. COVID-19 has exposed or exacerbated core weaknesses in our society: extreme inequality, embedded structural racism, and a White-supremacist founding ideology that has shaped our social institutions, including the police, healthcare delivery, and yes, social services. Further, even though we have experienced the collective trauma of a pandemic, as a nation we have not drawn

TO BUILD A BETTER WORLD: NOW IS THE TIME FOR A RIGHTS-BASED APPROACH TO SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

Jane McPherson, PhD, LCSW Director of Global Engagement Associate Professor

together in solidarity, but seem to have grown even further apart (Gomez, 2021).

So, what is a social worker to do? To paraphrase both Saul Alinsky (1971) and Barack Obama (2018), we need to work in the world today—as it is—and we must work to dismantle unjust systems in order to build the world as it should be. As professionals who work shoulder-toshoulder with individuals experiencing injustice (including our own friends, family members, and even ourselves), we must use our skills—both micro and macro— to address people’s immediate needs while also insisting on a redistribution of privilege, wealth, and power in our society and our profession. In other words, now is the time for social workers to commit to taking a rights-based approach to social work practice (Mapp et al., 2019).

What can a rights-based approach bring to the current moment?

Rights-based practice sees the world through a human rights lens; it employs rights-based methods; and it aims at rights-based goals. Through a rightsbased lens, we see that access to healthcare, unemployment benefits, housing, social

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 12

Rights-BasedApproachtoSocialWorkPractice – Jane McPherson

McPherson ©2015

security, education, etc.—the social and economic rights first promised in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)—are actually privileges reserved for the lucky rather than rights guaranteed to all. Shifting the focus from human needs to human rights requires social workers to see clients’ concerns in larger sociopolitical context and to assess for the presence of oppression and social exclusion, beyond the more standard social and psychiatric concerns. Further, it challenges us to work in solidarity with our clients in the fight for justice. Seeing problems through a rights-based lens leads social workers to set ambitious, justice-focused goals. A client’s need for a roof over her head may be met by

referring her to a shelter, but securing her human right to housing will require a longterm commitment to social and political change.

A rights-based approach guides intervention. Rights-based social workers root their practice in the human rights principles of human dignity, antidiscrimination, participation, transparency, and accountability (McPherson & Abell, 2020). Living by these principles, we cultivate democratic and transparent engagement with service users. Relationships built on equality and respect serve to deconstruct traditional power dynamics based on profession, race,

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 13

– Jane McPherson

Rights-BasedApproachtoSocialWorkPractice

Pillars of Practice

Components of Practice

Clients are seen as experiencing rights violations.

Rights-BasedApproachtoSocialWorkPractice – Jane McPherson

income, or other social status (McPherson, 2015). This practice of building respectful and engaged partnerships that question the usual distribution of authority creates expectations—within service users and social workers—that all people will be listened to and treated with dignity. Everyone’s voice matters.

Rights-based practice with its ambitious and aspirational goals is necessarily collaborative. To create the justice-focused changes, social workers must engage clients, communities, and political leaders. Other professionals are needed: lawyers, certainly, but also organizers, doctors, educators, researchers, faith leaders, and more. Rights-based practice, which requires attention to both micro- and macro-level concerns, demands skills and energy that go beyond what a single human being (even a social worker!) is likely to possess.

Rights-based practice is political. It requires advocacy and activism, and this is surely a time when political action is needed to address the human rights violations that we see all around us: people of color assaulted by police or incarcerated in US prisons, jails, and detention centers are experiencing violations of their right to nondiscrimination; the Supreme Court has declined to protect women’s reproductive rights, and all around us states are stripping those rights away; and voting rights are everywhere in jeopardy. Rights-based practice requires social workers to stand up for human rights. Social workers may feel uncomfortable with this call to political action. Indeed, evidence shows that social workers are less comfortable with activism than they are with other aspects of the rights-based practice model (McPherson & Abell, 2020).

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 14

Rights-BasedApproachtoSocialWorkPractice

This discomfort is something we must examine critically. Professional neutrality simply serves to ally professionals with the powerful against the interests of the underserved and disenfranchised (Farmer, 2005; Freire, 1984). We must return to the activism that built our profession and revive our long and brave tradition of campaigning for civil, social, and economic rights (Piven & Cloward, 1978; Reisch, 2013).

A human rights-based approach to social work understands service users as experts and partners, rather than passive recipients of charity and services (Mapp et al., 2019). It also empowers—and challenges—us to promote our core professional values, even (and especially) when those values are threatened by structural racism and austerity-driven social policy.

Arundhati Roy asks us to imagine the world on the other side of the portal. As social workers, we must pass through that door as human rights practitioners. We must embrace practices that fully respect the human dignity and human rights of our services users. We must envision an ambitious expansion of a human rights access for all—and we must be willing to work for it. •

Author note: An earlier version of this editorial appeared in the Journal of Human Rights and Social Work (June 2020) as “Now Is the Time for a RightsBased Approach to Social Work Practice.” https://link. springer.com/article/10.1007/s41134-020-00125-1

references:

Alinksy, S. D. (1971). Rules for Radicals. New York: Random House.

Farmer, P. (2005). Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Freire, P. (1984). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gomez, V. (2021). A partisan chasm in views of Trump’s legacy. https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2021/03/29/a-partisan-chasm-in-views-oftrumps-legacy/

Mapp, S., McPherson, J., Androff, D.A., Gatenio Gabel, S. (2019). Social work is a human rights profession. Social Work, 64(3), 259-269. https://doi.org/10.1093/ sw/swz023

McPherson, J. (2015). Human rights practice in social work: A U.S. social worker looks to Brazil for leadership. European Journal of Social Work, 18, 599-612. https.com//doi:10.1080/13691457.2014.9472 45

McPherson, J. & Abell, N. (2020). Measuring rightsbased practice: Introducing the Human Rights Methods in Social Work scales. British Journal of Social Work, 50, 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz132

Obama, M. (2018). Becoming. New York: Crown Publishing.

Piven, F. F. & Cloward, R. A. (1978). Poor people’s movements: Why they succeed and why they fail. New York, NY: Vintage.

Reisch, M. (2013). What is the future of social work? Critical and Radical Social Work, 1(1), 67-85. https:// doi.org/10.1332/204986013X665974

Roy, A. (2020, April 3). The pandemic is a portal. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/ content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 15

– Jane McPherson

TRAUMA-INFORMED WORK WITH NATIVE TRAFFICKING SURVIVORS

Kate Morrissey Stahl, PhD, LCSW, CST Clinical Associate Professor

Understanding the most effective and most appropriate ways to engage with survivors of sex trafficking is critical to curbing its epidemic across the world, including here in the United States.

Thanks to a small seed grant of $20,000 from the Center on Human Trafficking Research and Outreach (CenHTRO), I have been able to be a part of a research team focused on the impacts of sex trafficking in Native youth populations. This two-year project will wind down at the end of 2023, and will hopefully yield valuable insights that can better inform and guide our interviewing practices when it comes to understanding instances of sex trafficking.

CenHTRO was established in 2021 as a collaborative, cross-disciplinary, and international research hub in the global effort to combat human trafficking. Led by Professor David Okech of the UGA School of Social Work, the center conducts research, develops programming, and influences policies that drastically and measurably reduce human trafficking and other forms of exploitation.

Its focus has primarily been beyond the U.S.’s borders, particularly in sub-Saharan

Africa. However, CenHTRO sought to expand its reach domestically and announced a series of funding opportunities designed to address the existing gaps in measuring and evaluating the prevalence of human trafficking domestically.

As someone who was born and raised in South Dakota, I recognized the benefits a focused research project on Native youth trafficking could provide. I asked my sister, who still lives and works in South Dakota, to introduce me to researchers who were working on the issue of sex trafficking, and I thought how this money could support the projects of researchers with more experience than myself.

Our team of researchers, Bridget DiamondWelch, Anna Koloski, and I, proposed using the grant as an opportunity to better understand, and hopefully refine, the process for interviewing Native youth sex trafficking survivors.

We considered this project to be a pilot study, allowing us to better imagine how to do the work and, most importantly, how to do it sensitively and thoughtfully. This could later lead to future, larger projects that can bring greater awareness to Native

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 16

Trauma-InformedWorkwithNativeTraffickingSurvivors – Kate Morrissey Stahl

Quote from CenHTRO website on faculty seed grants.

sex trafficking and inform how to do the work in sensitive, community engaged ways.

Native youth sex trafficking is a significant problem, but its full scope and scale is unknown. Data around it often is missing or incomplete, giving us only a partial picture of the challenge. The goal of this project is to try and bring some clarity to that picture, understanding this is a small, but important first step.

Part of the challenges stems from the way sex trafficking is defined. It can vary by jurisdiction, while access to available data can sometimes be difficult to obtain. However, understanding the full scope of the problem across tribal communities –and the nation – is a big problem that needs to be addressed.

Interviewing survivors of youth sex trafficking is a delicate, difficult process, but one that is necessary for a multitude of reasons. Those difficulties are magnified when it comes to interviewing Native youth. There could be disconnects, particularly for non-Native researchers or clinicians, and it is important to know what culturally humble practices are.

This is why we are fortunate to have an advisory board to support our efforts on this project. The board is made up of Native experts, as well as experts in the community on human trafficking. We’re also grateful to have Pauletta Red Willow, the owner of Maggie’s House, a South Dakotan safe house that provides a stable environment for trafficked, homeless and young adults between the ages of 17 and 21, as our key advisor, and two-spirit therapist and thought leader Lenny Hayes to provide support to the adult interviewees if they need it.

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 17

– Kate Morrissey Stahl

Trauma-InformedWorkwithNativeTraffickingSurvivors

“Morrissey Stahl’s research project—

‘Developing a Methodology for Trauma-Informed Interviews of Native Child Victims of Human Trafficking’— will provide critical information on safe practices to conduct interviews with Native youth victims of sex trafficking, including youth who are gender diverse, such as Two Spirit.”

Members of the advisory board are compensated for their time and efforts, and they offer guidance on the best way to approach each question, if our questions are sensitive enough and if they are thoughtfully worded. Its counsel throughout the project has been invaluable, enabling our team to interview our participants in a respectful and engaging way so we can better understand what these best practices for interviewing Native youth would be.

For good reason, it is taking a substantial amount of time and a diligent process to receive ethical clearance to work with Native populations because of the abuse that has occurred to these populations on many levels, including from researchers. The oversight for research in Native communities is rigorous and effective, and this ethics review for our research was extensive and beneficial, including both tribal and university review, enabling us to get the necessary clearances to work with the different tribal nations and protecting the data we collect from participants from misuse.

While our team focuses on the research component, our partners on the advisory review every aspect of the project. You don’t get an unlimited number of chances to learn about the topic of trafficking, and we can learn a lot from youth. However, it needs to be done in a way that doesn’t create more harm.

We also know there are best practices when it comes to interviewing youth in general, but there is not existing literature that specifically states what are the best practices for interviewing Native youth sex trafficking survivors. This project is attempting to answer that question by interviewing Native adult sex trafficking survivors and interviewing professionals

who work with Native youth sex trafficking survivors.

This research is in the context of my broader work: I am a clinical associate professor at UGA’s School of Social Work, I own a sex therapy practice called Revolution Therapy and Yoga, and I serve on the board of DIVAS who Win, a group that supports healing in survivors of sex trafficking in Georgia – so I am primarily a practitioner and a clinician. That professional overlap is at the heart of social work research. We as practitioners and researchers work to are bring funds to and honor the expertise of the communities, while helping them support people in their own communities.

My hope is we will help make interviewing processes trauma informed and culturally humble and sensitive to native populations in a way that supports either us better understanding the problem of Native sex trafficking or other researchers and clinicians better understand what they might think about when interviewing youth about sex trafficking in tribal groups or other communities.

Additionally, I hope this work can help us become more aware and show more concern about sex trafficking, especially in populations that have been historically marginalized. Sex trafficking is happening in many communities, and I hope we continue to learn about it and find out on a research, practice and community level how to best respond to the problem. •

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 18

Trauma-InformedWorkwithNativeTraffickingSurvivors – Kate Morrissey Stahl

UTILIZING TRAUMA-INFORMED PERINATAL CARE TO ADDRESS BIRTH TRAUMA AND IMPROVE OUTCOMES

Sarah Gormley, MSW, TF-CBT PhD Student

The United States is currently experiencing a maternal health crisis that positions Black birthing people at disproportionate risk for traumatization in the perinatal period. Black birthing people in the United States are 3.3 times more likely to die in childbirth than White birthing people (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). In the state of Georgia, maternal mortality for Black birthing people is nearly six times the national average for white birthing people (“When the State Fails: Maternal Mortality and Racial Disparity in Georgia”, 2020). The cause of maternal death of Black birthing people is more likely to be deemed preventable as compared with White birthing people (Louis et al., 2015). This disparity in pregnancy-related death does not discriminate amongst income and education levels for Black birthing people (Louis et al., 2015). Furthermore, hospitals that serve majority Black patients have higher rates of maternal complications than other hospitals and “perform worse on 12 of 15 birth outcomes, including elective deliveries, non-elective cesarean births and maternal mortality” (Creanga et al., 2014). Up to 45% of birthing people report that their births were traumatic (Beck et al., 2018).

A strong body of evidence connects past trauma with poor maternal health outcomes, including increased preterm birth rates, low neonatal birth weights and increased prevalence of Perinatal Mood Disorders (PMDs). Birthing people with a history of childhood maltreatment have a 12-fold increased risk of PTSD during pregnancy (Seng & Taylor, 2015). The combination of having Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and low social support increases the risk of depression in pregnant and postpartum people, indicating social support as an important protective factor for the effects of trauma on maternal health (Racine et al., 2020).

Furthermore, birthing people experience the likelihood of re-traumatization in childbirth as they navigate factors such as power dynamics of the client-caregiver relationship, a lack of bodily autonomy, an emphasis on or physical touch of body parts associated with past trauma, and various elements of the birth experience that can re-trigger trauma from a prior traumatic birth (Simkin, 2004).

The disproportionate risk that Black birthing people face for traumatization in the perinatal period, combined with

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 19

PerinatalCare – Sarah Gormley

Utilizing Trauma-Informed

the known effects of trauma on maternal health, calls for a trauma-informed response geared towards parents, childbirth professionals and obstetric providers. A public health approach to the problem of trauma and maternal health seeks to address the factors that contribute to poor maternal outcomes, as well as the inequal distribution of those outcomes across race. These include but are not limited to biological or behavioral risk factors, access to care, the impact of medical racism, and most recently, social and structural determinants of health that underscore the impact of social needs on perinatal health and wellness. However, it is essential to integrate a social work approach into our collaborative response to the maternal health crisis, as social workers are uniquely positioned to disrupt maternal health inequities at micro, mezzo and macro levels of practice.

My research is interested in the integration of case management services into the medical care team, as well as the implementation of perinatal traumainformed care programs into the clinical care settling. Perinatal trauma-informed programming equips parents, partners and providers with tools and techniques for reducing re-traumatization in the perinatal period.

Popular models and frameworks for trauma-informed clinical care must be adapted to meet the unique needs of the perinatal population. Research on the effects of trauma on the physiological process of childbirth, breastfeeding and postpartum recovery is needed to further our understanding of the association between trauma and maternal health. Finally, collaboration with communitybased labor and postpartum doula initiatives can serve to promote social

support through the childbearing year while improving birth outcomes for marginalized populations (Vonderheid et all, 2011). •

references:

Beck, C. T., Watson, S., & Gable, R. K. (2018, June). Traumatic childbirth and its aftermath: Is there anything positive? The Journal of perinatal education. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6193358/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Report from maternal mortality view committees: A view into their critical role. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/ files/upload/pdf/MMRIAReport.pdf

Creanga, A. A., Bateman, B. T., Mhyre, J. M., Kuklina, E., Shilkrut, A., & Callaghan, W. M. (2014). Performance of racial and ethnic minorityserving hospitals on delivery- related indicators. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 211(6), 647-e1. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/24909341/

Gruber, K. J., Cupito, S. H., & Dobson, C. F. (2013). Impact of doulas on healthy birth outcomes. The Journal of perinatal education, 22(1), 49–58. https:// doi.org/ 10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49

Louis, J. M., Menard, M. K., & Gee, R. E. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 125(3), 690-694.

Racine, N., Zumwalt, K., Mcdonald, S., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2020). Perinatal depression: The role of maternal adverse childhood experiences and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 576-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.030

Seng, J., & Taylor, J. (2015). Trauma informed care in the perinatal period. Dunedin Academic.

Simkin, P., & Klaus, P. H. (2014). When Survivors Give Birth: Understanding and Healing the Effects of Early Sexual Abuse on Childbearing Women. Seattle: Classic Day Publishing.

When the state fails: Maternal mortality and racial disparity in Georgia. Yale Law School. (2018). Retrieved from https://law.yale.edu/yls-today/news/whenstate-fails-maternal-mortality-and-racial-disparitygeorgia

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 20

Utilizing Trauma-Informed PerinatalCare – Sarah Gormley

School of Social Work Statement on Racism and Social Justice

The School of Social Work condemns racism and the callous acts of violence behind the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, other African Americans and Asian American Pacific Islanders. We mourn their deaths. We condemn the alarming rise in discrimination, oppression, harassment, violence, and Anti-Asian racism perpetuated in the wake of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We are committed to seeking racial justice and to actions that make positive change happen. We are committed to these actions with broad input and ongoing collaboration and dialogue. We are committed to ensuring that “social justice” is more than a phrase on our website. It is the focus of our mission.

We strongly support our professional organization, the National Association of Social Workers, and its condemnation of lethal police force against unarmed African Americans, our educational accreditation body, the Council on Social Work Education, and its Statement of Social Justice and the Society for Social Work and Research’s Call and Commitment to Ending Police Brutality, Racial Injustice, and White Supremacy. We also support the Council on Social Work Education, the Asian Pacific Islander Social Work Educators Association, Filipinx Social Work Network, Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work, Korean American Social Work Educators Association, National Association of Deans and Directors of Schools of Social Work, Society for Social Work and Research, the St. Louis Group for the advancement of social work research and education, and South Asian Social Work Educators Association in their Joint Statement Against Anti-Asian Racism.

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 21

SOCIAL JUSTICE COMMON BOOK INITIATIVE

Jennifer Elkins, PhD MSW Program Director Associate Professor

Jennifer Elkins, PhD MSW Program Director Associate Professor

Tiffany Washington, PhD Interim PhD Program Director Associate Professor

“The changes we have to have in this country are going to be for the liberation of all people, because nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

– Fannie Lou Hamer SocialJusticeCommonBookInitiative – Tiffany Washington, Jennifer Elkins

Established in 2019, the Social Justice Common Book Initiative (SJCBI) is designed to 1) underscore social work’s commitment to promoting social justice; 2) acclimate incoming social work students to the SSW culture; and 3) foster critical thinking and intellectual curiosity among students. Each year the SJCBI committee selects a book that addresses a timely topic relevant to the current sociopolitical climate and aligns with our mission to prepare culturally responsive practitioners and scholars to be leaders in addressing social problems and promoting social justice, locally and globally.

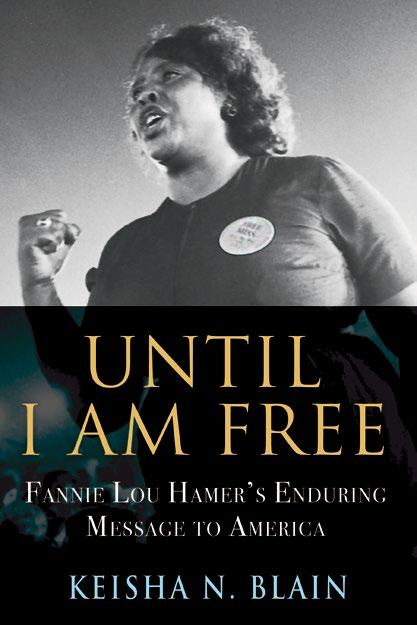

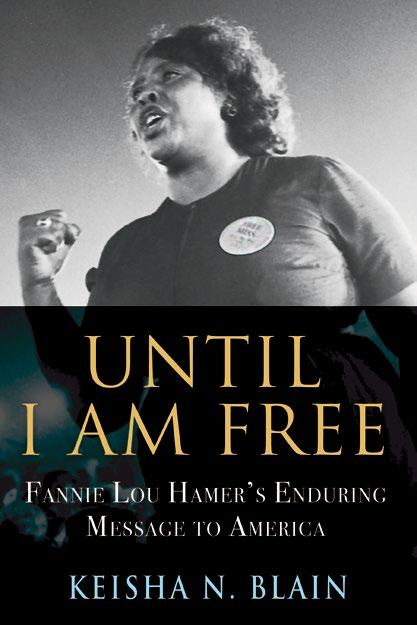

A blend of social commentary, biography, and intellectual history, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America, by awardwinning historian and New York Times bestselling author Dr. Keisha N. Blain, is a manifesto for anyone committed to social justice, liberation and freedom dreaming. The title of this book calls upon one of Hamer’s most well known refrains: “the changes we have to have in this country are going to be for the liberation of all people, because nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” The book challenges us to grapple with contemporary concerns around race, inequality, human rights, and intersectional social justice through the

telling of Fannie Lou Hamer’s life as a Black woman in the Jim Crow South. Hamer was a key activist, organizer, and intellectual of the Civil Rights Movement. Until I am Free underscores the impact of local and state government on everyday lives and encourage readers to be active citizens. And, just as importantly, it demonstrates how her ideas remain salient for a new generation of activists committed to dismantling systems of oppression locally and globally.

To date over 800 incoming MSW, MANML, and PhD students have participated in the SJCBI during their summer and fall orientations. In addition to exciting and energizing discussions at orientation, many faculty have incorporated the book selections into their courses through required reading, assignments, and/or discussions. As with previous selections, we expect this book to expand students’ understanding of social justice, engage their intellectual curiosity about its impact, challenge their critical thinking about social workers’ role in dismantling white supremacy, and imagine a more just future by understanding our past. Drs. Washington and Elkins are proud to have established this initiative and look forward to seeing the new and exciting directions it takes in its

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 23

Washington, Jennifer Elkins

SocialJusticeCommonBookInitiative – Tiffany

keishablain.com

A

LETTER TO RESISTANCE, AND REFLECTIONS OF A NEW WORLD

Joy Green, MSW PhD Student

Eighty of us have come together late on a Thursday evening. Through a virtual shared space, we are led through a radical practice of rest. It has been a long day, a long week, a long year, a long decade. A brilliant Black woman author and rest-advocate by the name of Octavia Raheem shares with us:

I came to rest kicking and screaming. This statement is eerily familiar to me. Just twenty minutes before this event, I’d found myself spinning in circles, having been ‘on’ for well over fifteen hours. Still spinning, going, doing – my mother asks, “Are you going to be able to make the Rest Event this evening?”

It’s her way of reminding me of all that sustains us in this space, and in this work. I go with my “first mind,” and tell her I can no longer make it. Another voice, one from the depths of my spirit, ekes out a hopeful, gentle push to step away and make room for this, for rest, for this sacred, privileged form of resistance.

I stop what I’m doing and listen to the call to join in the practice. Through the noise

of my mind, still “kicking and screaming,” I hear Octavia Raheem speak these words first written by Arundhati Roy:

Another world is not only possible; she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.

I attend a dinner meeting with a younger student and a grassroots community organizer. We have each come from and through so many places, so much pain, and so much light. Our values and activisms propel us, but it is our truths and deepest vulnerabilities that ultimately connect us. We sit, and we unearth. In that space, I am reminded of community. In that space, unexpectedly, we mobilize through healing.

Another world is possible; I can hear her breathing.

As I work on a project, I am called to reflect on what it means to ‘witness’ a thing. I think about how that word has stayed in my mind since reading it in the social media post of an activist-scholar years ago as they shared a video taken by a young Black girl experiencing intimate partner violence.

I think about the way this event spoke to my spirit – and how that young Black girl

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 24

ALettertoResistance,andReflectionsofaNewWorld – Joy Green

was ultimately murdered by her Black cisgender, heterosexual male partner, but instinctively took the video right before her death because she needed her community, someone, anyone - to witness her and her experience, even if it might be too late.

Another world is possible; I can hear her breathing.

It is a Tuesday during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a Black, queer organizer posts a status on her Facebook with an urgent call to action. A Black femme is fleeing an abusive partner with her two young children, and she is in need of $450 to secure temporary housing. A virtual crowd sees this request, and in a matter of minutes, she is receiving immediate and direct financial assistance. This same movement works day in and day out to garner community support in a range of scenarios – all the while holding space for those struggling to find their way through severely flawed systems. This group has taken it upon themselves to step in as a result of the tragic realization that no one else would.

Another world is possible; I can hear her breathing.

News breaks that a young Black woman named Breonna Taylor has been murdered in her home by police officers in the middle of the night after waking up to a raid authorized by a no-knock warrant. We continue to say her name. And still:

Another world is possible; I can hear her breathing.

A group of queer and trans, Black and Brown people, exquisitely dressed and exuding the essence of liberation, have joined together for a Ballroom event in Atlanta.

Communicating through chants and sharp movement, they demonstrate the fluidity of gender, the wonder of our bodies, and the restorative power of community. It is the ultimate self-expression and reclamation of joy. This space captures the ‘in-between’ of two worlds: the mess of our present and a dream of what could be.

Another world is possible; I can hear her breathing.

These words have haunted me, and as more shifts, these words grow louder. There is no doubt that we are in a critical moment, and it has become nearly impossible to look past the incredible unraveling taking place within the structures that have governed us. Still, in the quiet and through our resistance, we are dreamers.

Part of my journey as a Black, queer, femme-identifying doctoral student at the School of Social Work has consisted of preparing to answer the call to dig deeper and to locate clarity on my reason-my “why.” For me, this process begins with my fierce belief in the power of resistance. Resistance is both unplanned and deliberate. It is defiant. It is freedom and fire. It is joy. It is safety when the world is everything but safe. It is the way that persisting has lifted Black people, Black queer communities, Black women, and Black MaGes throughout history.

The reality of belonging to any social identity group without privilege is the feeling of operating within a paradigm, a world, that was not built for you. To an extent, society demands this of us. In other ways, we resist. Always building off history, I return to the works of Black feminist scholars such as Patricia Hill Collins and her observations on responses to the phenomenon of existing as an “outsider,

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 25

ALettertoResistance,andReflectionsofaNewWorld – Joy Green

within.” To leave an institution is to protect your energy; to stay and conform is a different side of the same pain. To remain and endeavor to influence change may be slow and, at times, thankless. I sometimes feel myself pulled in all three directions. And I’ve witnessed outcomes in all three directions.

It is the visceral response we feel when engaging with ideologies, articles, and research studies that inadvertently pathologize entire communities. It is the reality of not seeing yourself or your cultural lived experiences represented, and the instances that cause us to assess our belonging and abilities through the narrow lens of capitalism. It is the way I’ve watched professors and social work practitioners forced to bend, and adapt, and stay, and leave. It is this very existence, though, that has inspired marginalized people to build new systems, standards, and worlds in ways that do not wait for nor require the approval of dominant groups. It is the understanding that to make your own meaning despite the common narratives is to create and shift paradigms.

Another world is not only possible; she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.

Where the drive begins with resistance, it culminates in the radical act of healing. By celebrating the joy, the restoration, the collective action, and the resistance of Black queer people, Black women, and Black people whose gender identities expand across and beyond the binary – we focus on, dream of, push for, and aspire to revolution and new worlds. •

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 26 26

ALettertoResistance,andReflectionsofaNewWorld – Joy Green

TO HAVE A COLLECTIVE FUTURE, THE TIME TO ACT IS NOW

Amelia Mahan, MSW, LCSW Part-Time Instructor

Environmental justice and the climate crisis continue to be an area little explored by the majority of social workers in the United States. In recent years these pressing issues have gained momentum – they are a part of the CSWE EPAS (Council on Social Work Education, 2022) as well as the Grand Challenges for Social Work (American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare, 2016). However, gaining momentum is not enough. The time to act is now. There are multiple facets of environmental justice ranging from the impact of climate change disrupting historically marginalized communities “first and worst” (Whyte, 2017), to increased climate anxiety, to the location of pollutants and toxic waste, to equity in access to green natural spaces, to the whiteness of environmentalism which co-opts the work of Indigenous peoples – the list goes on. Environmental justice should not be carved into a specialty niche reserved for macro social work practitioners, but rather should be a part of all social work practice.

U.S. social work has a strong focus on individual and family practice, and person-in-environment has meant social environment rather than natural environment. It can be argued that U.S.

social workers have accepted the status quo of neoliberal growth, privatization, and individualism, at the expense of accepting our symbiotic relationship to the natural world. To be relevant in an interconnected world, we in the United States must recognize the consequences of the Global North’s disproportionate consumption and exploitation of natural resources on developing nations. The richest 0.1% have made their fortunes from industries that contribute much of the damage to the environment (Noble, 2016). “Those countries that have contributed least to the climate breakdown, mainly in the Global South, will suffer the most from floods, droughts, and rising temperatures. This is a pattern of suffering with a long history” (Lammy, 2020, 3:53). Oppressions due to class, gender, ethnicity, etc. snowball under the weight of environmental disasters, including the scarcity of food and water. Vulnerability from natural and humanmade disasters is increased in rural areas where there is a lack of emergency response infrastructure and other resources (Holbrook, et al., 2019). Additionally, an aging population is more susceptible to poverty and declining health, impacting their capacity to respond to the increasing effects of climate change (Appleby, et al., 2017).

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 27

ToHaveaCollectiveFuture,theTimetoActisNow – Amelia Mahan

Only by shining a light on an issue, can we begin joining with others to find solutions and to adapt to a future that is fast approaching. As a profession, social work must “recognize our essential connection to all of nature. Effective interventions must address not only personal stress and reactions to climate-related issues, but also significant lifestyle, community, and public policy issues to shift towards a more sustainable society” (Coates & Gray, 2012, p. 232). Critical reflexivity is built into social work practice. Now is the time to critically examine, question, challenge, and dismantle modern societal structures, values, and ways of life that lead to overproduction and over-consumption. The risks of ignoring the very real climate crisis are too severe. Social workers, especially those of us who are whitebodied, must recognize how our power

and our environmental privilege are tied to our colonial history (Erickson, 2018, para 3). As we engage in the critical work of decolonizing every aspect of our profession, so must we consider decolonization as it relates to environmental justice:

The exploitation of our planet's natural resources has always been tied to the exploitation of people of color. The logic of colonization was to extract valuable resources from our planet through force, paying no attention to its secondary effects. The climate crisis is in a way colonialism's natural conclusion. (Lammy, 2020, 4:17)

The worst outcomes of climate change (i.e., species extinction, forced migration, hunger, disease, lack of clean water) are all conditions that were forced on Indigenous

ToHaveaCollectiveFuture,theTimetoActisNow – Amelia Mahan

communities by their colonial oppressors (Whyte, 2017). History is repeating itself. Threats to our collective survival as a people feel new to many of us as we are not used to having our futures endangered. For Indigenous people, they have long experienced these hazards to a future existence (Bell, et al., 2019).

As social workers, where do we go from here? As a profession we should activate our strengths: our critical reflexivity, our knowledge of behavior change, our systems thinking, our person-in-environment perspective, our ability to work across disciplines, and our mindful considerations of equity, power, and anti-racism. We have a responsibility to build environmental justice principles into our own practices and into curriculum for the next generation of social workers. We can do the latter in a myriad of ways, including by using case examples, service-learning opportunities, and field placements (Hudson, 2019). Let us provide decolonized crisis intervention with survivors after disasters while also engaging in preparedness for future disasters, recognizing that the onus is not only on individuals and communities to adapt, but also on oppressive structures to change (Pyles, 2017). Through participatory community needs assessments, capacitybuilding, and collective action, social workers are well-placed to center and amplify marginalized voices in the environmental justice fight. We must find points of connection as intersectional and complex human beings and stand in solidarity with other social justice movements. Our collective lives depend on it. •

references

American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare. (2016). Create social responses to a changing environment: Grand challenges for social work. Grand challenges for social work. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://grandchallengesforsocialwork. org/create-social-responses-to-a-changingenvironment/

Appleby, K., Bell, K., & Boetto, H. (2017). Climate Change Adaptation: Community Action, Disadvantaged Groups and Practice Implications for Social Work. Australian Social Work, 70(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2015.1088558

Bell, F. M., Dennis, M. K., & Krings, A. (2019). Collective survival strategies and anti-colonial practice in ecosocial work. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3/4), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2 019.1652947

Coates, J., & Gray, M. (2012). The environment and social work: An overview and introduction. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21(3), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00851.x

Council on Social Work Education. (2022, June 9). 2022 Educational policy and accreditation standards (EPAS) [PDF]. Council on social work education. https://www. cswe.org/getmedia/94471c42-13b8-493b-9041b30f48533d64/2022-EPAS.pdf

Erickson, C. L. (2018, August 20). Teaching environmental privilege is integral to environmental justice. Oxford university press blog. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://blog.oup. com/2018/08/teaching-environmental-privilegeintegrall-justice/

Holbrook, A. M., Akbar, G., & Eastwood, J. (2019). Meeting the challenge of human-induced climate change: reshaping social work education. Social Work Education, 38(8), 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/02 615479.2019.1597040

Hudson, J. (2019). Nature and social work pedagogy: How U.S. social work educators are integrating issues of the natural environment into their teaching. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3-4), 487-502. https://doi. org/10.1080/10705422.2019.1660750

Lammy, D. (2020, October). Climate justice can’t happen without racial justice [Video]. TED Conferences. https://tinyurl.com/844t9s5t

Noble, C. (2016). Green Social Work -- The Next Frontier For Action. Social Alternatives, 35(4), 14–19. Pyles, L. (2017). Decolonising Disaster Social Work: Environmental Justice and Community Participation. British Journal of Social Work, 47(3), 630–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw028

Whyte, K. P. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the Anthropocene. English Language Notes, 55(1–2), 153–162. https://doi. org/10.1215/00138282-55.1-2.153

SOCIAL JUSTICE WANTED | 2022–2023 29

ToHaveaCollectiveFuture,theTimetoActisNow – Amelia Mahan

SOWK 7118:

MSW

Power, Oppression,

Social Justice and Evidence-informed Practice, Advocacy, and Diversity in Social Work (PrOSEAD TM)

CURRICULUM STATEMENT

(Appears at top of every syllabus):

Beginning 2017, the UGA SSW faculty has adopted a focus on addressing power and oppression in society in order to promote social justice by using evidence based practice and advocacy tools and the celebration of diversity. This philosophy, under the acronym, PrOSEADTM, acknowledges that engagement, assessment intervention, and evaluation with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities requires an understanding of the historical and contemporary interrelationships in the distribution, exercise, and access to power and resources for different populations. And, that our role is to promote the well-being of these populations using the best and most appropriate tools across the micro, mezzo and/or macro levels of social work practice. In short, we are committed to: Addressing Power and Oppression, Promoting Social justice, Using Evidence-informed practice and Advocacy, & Celebrating Diversity

a. Power - Certain sections of populations are more privileged than others in accessing resources due to historical or contemporary factors related to class, race, gender, etc. Our curriculum will prepare students to: (i) identify and acknowledge privilege issues both in society as well as at the practitioner/ client level; (ii)have this understanding inform their practice In order to competently serve clients who experience disenfranchisement and marginalization.

b. Oppression - Social work practice across the micro-macro spectrum should work to negate the effects of oppression or acts of oppression locally, nationally and globally. Our curriculum will prepare students to enhance the empowerment of oppressed groups and prevent further oppression among various populations within the contexts of social, cultural, economic, political, and environmental frameworks that exist

c. Social Justice - Social workers understand that human rights and social justice, as well as social welfare and services, are mediated by policy and its implementation at the federal, state, and local levels. Our curriculum will prepare students to engage in policy practice at the local, state, federal, or international levels in order to impact social justice, well-being, service delivery, and access to social services of our clients, communities and organizations.

d. Evidence Informed Practice – Social workers understand that the clients’ clinical state is affected not only by individual-level factors but also by social, economic, and political factors. We are also cognizant that research shows varied levels of evidence for practice approaches with various clients or populations. Our curriculum will prepare students to engage in evidence-informed practice. This includes finding and employing the best available evidence to select practice interventions for every client or group of clients, while also incorporating client preferences and actions, clinical state, and circumstances.

e. Advocacy – Every person regardless of position in society has fundamental human rights to freedom, safety, privacy, an adequate standard of living, health care, and education. Our curriculum will prepare students to apply their understanding of social, economic, and environmental justice and their knowledge of effective advocacy and systems change skills to advocate for human rights at the individual and system levels

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | SSW.UGA.EDU 30

PrOSEADTM Syllabus

f. Diversity - Social workers need to understand how diversity and difference characterize and shape the human experience and are critical to the formation of identity. Our curriculum will produce students who are able to engage, embrace, and cherish diversity and difference across all levels of practice

COURSE DESCRIPTION

This required course encapsulates the entire philosophy of our MSW curriculum. It examines the interrelationships between Power, Oppression, Social justice, Evidence informed practice, Advocacy and Diversity in social work practice. The overall framework focuses on understanding the barriers to and the enablers of social change (see figure in pg. 2). Students learn about the UGA SSW’s initiatives on social justice and human rights. The course will help students to focus on critical self-reflection and the arduous and often painful trajectory to recognize their privileges or power and how it shapes their lives and interactions; how it might be oppressive to others; how diversity in its various forms may be understated; how to advocate at all levels of practice for the under-privileged, and how to base practice on the social work tenets of social justice, human rights, and choosing the most appropriate interventions.

STUDENT OUTCOMES