3 minute read

Collections Conservation

Joan Mitchell (American, 1925–1992) "Red Painting No. 2," 1954 Oil on canvas 67 5/8 x 74 x 2 1/2 in. Gift of Frederick King Shaw, 1973.34 © Joan Mitchell Foundation

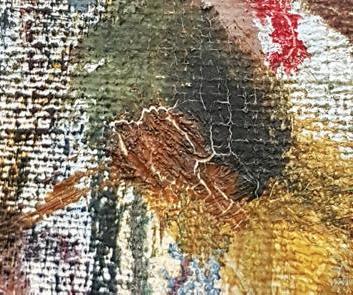

Red Painting No. 2 (1954) is a spectacular work that helped earn Joan Mitchell early acclaim. Mitchell was one of the very few women who helped to cement the reputation of the Abstract Expressionists through her participation in the watershed Ninth Street Show in 1951 and, in following years, her solo exhibitions at the Stable Gallery, NYC. Red Painting no. 2 was recognized for its daring; Kyle Morris included it as part of the 1955 exhibition Vanguard at the Walker Art Center. Critics alternately described her work as lyrical or aggressive, rigorously abstract or naturalistic. Red Painting No. 2 sustains the simultaneity of these seemingly contradictory descriptions. Colorful marks accrue across the canvas, layered like sediment to create passages of thick impasto. The highly gestural, vibrant abstract painting shimmers and registers at times like landscape.

Precisely because of its experimental approach and because it is so well loved, the painting has had a few condition issues. In the past it had lost some paint because of scratches here and there, but more recently and more alarmingly, the painting had begun to flake. This was one of the most highprofile paintings in our collection that was in need of treatment. But there are others in the collection that needed care as well. When Joyce Tsai first arrived as curator in 2016, she conducted a survey of the paintings with Katherine Wilson, manager of exhibitions and collections, and Kim Datchuk, now curator of learning and engagement. As newcomers, Kim and Joyce wanted to get a sense of the collection in person, but the process also gave them an opportunity to identify artworks that should be conserved. Because the collection is in Davenport, this study had to be conducted over the course of a year on days they could devote to being in storage. It was a thrilling experience for them to go from reviewing the collection through the database to seeing the works in person.

One painting that caught their eye was Girl in Green (1937) by Nicolai Cikovsky. It was a charming picture but in an alarming state—not only was it dirty, but the painting had been folded over multiple times and there were patched nail holes along the edge from various attempts to stretch the canvas. With a little research, museum staff discovered that this painting had once been in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and came to UI by exchange for a piece by Man Ray. That in itself was a bit shocking. Why on earth would the University of Iowa have a Man Ray painting to begin with, and what would convince the UI to exchange it with MoMA for this portrait?

Nicolai Cikovsky (American, 1894–1987) "Girl in Green," 1937 Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 x 37 ½ in. Exchange with the Museum of Modern Art, 1938.2 © Estate of Nicolai Cikovsky

Nicolai Cikovsky (American, 1894–1987) "Girl in Green," 1937 Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 x 37 ½ in. Exchange with the Museum of Modern Art, 1938.2 © Estate of Nicolai Cikovsky

Tastes and values change over time and Girl in Green captures these shifts. This painting debuted at the renowned Downtown Gallery in 1938 to rave reviews in The New York Times and was selected as a representative painting in Three Hundred Years of American Art , the landmark show that was organized by MoMA and exhibited in Paris. That same year, MoMA acquired the painting.

This painting came to Iowa in part because of the University of Iowa’s MFA program. While early on the program was devoted to Modern art, it was also training painters to work in traditional genres like portraiture. Even Phillip Guston, who taught at the University in the forties, executed portraits that share Cikovsky’s language.

In 2017 both the Mitchell and Cikovsky were among dozens of works assessed by a paintings conservator at the Midwest Art Conservation Center. Through the generosity of retired Iowa City citizen Steven A. Hall—who also happens to be Katherine Wilson’s father—the museum was able to send both paintings to be conserved. The Mitchell was cleaned, the areas of flaking and potential loss stabilized. Conservators vacuumed the Cikovsky, removed the dirty varnish, humidified the canvas to help relax the deformations, and filled paint losses. The Stanley is thrilled to bring both these paintings to light soon in the inaugural exhibition.