6 minute read

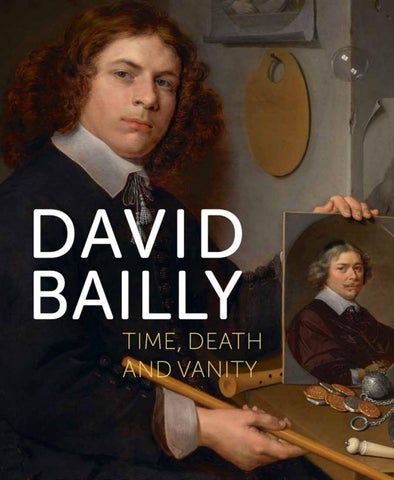

DAVID BAILLY TIME, DEATH AND VANITY

MUSEUM DE LAKENHAL, LEIDEN

WAANDERS PUBLISHERS , ZWOLLE

The Life of David Bailly Marika Keblusek

Self-Portraits and Portraits of Friends by David Bailly

Janneke van Asperen

David Bailly as a Portraitist

Rudi Ekkart

David Bailly & Vanitas

Christiaan Vogelaar

‘Cherchez la femme!’ The Reception History of David Bailly’s VanitasStill LifewithPortraitofaYoungPainter

Karin Leonhard

Phantoms, Portraits, Pigments: a Technical Examination of David Bailly’s VanitasStillLifewithPortrait ofaYoungPainter

Erma Hermens and Nathan Daly

Portraits and Tronies in David Bailly’s Vanitas and the Link with the Steenwijck Family

Carla van de Puttelaar and Fred G. Meijer

Exhibited objects

Bibliography

Index of names

‘So it is − the life we receive is not short, but we make it so, nor do we have any lack of it, but are wasteful of it. Just as great and princely wealth is scattered in a moment when it comes into the hands of a bad owner, while wealth however limited, if it is entrusted to a good guardian, increases by use, so our life is amply long for him who orders it properly. Why do we complain of Nature? She has shown herself kindly; life, if you know how to use it, is long.’

From: Lucius Annaeus Seneca, On the Shortness of Life, c. AD 49 (translation John W. Basore, 1932)

Sometimes, words and images from hundreds, or even thousands of years ago turn out to be surprisingly relevant today. The writings and letters of Seneca are still used as a basis for philosophical consideration of our complex relationship with time and death. Despite all the developments in technology and society, our struggles with time remain a recurring factor of daily life.

Seventeenth-century Leiden artist David Bailly included in one of his vanitas still lifes a bust that was believed at the time to be a portrait of Seneca. He must have been familiar with the writings of the Roman stoic philosopher, and they will have inspired his view of time as our most precious asset. David Bailly’s other work also suggests a great interest in the theme of transience and the vanity of human existence.

Museum De Lakenhal had a longstanding wish to research the work of Bailly, and discover its hidden meanings. The museum has a reputation for exhibitions based on Leiden resources and academic research, often performed in collaboration with fellow art historians in the Netherlands and abroad. Our David Bailly study was conducted by curators Christiaan Vogelaar and Janneke van Asperen, in collaboration with experts from Leiden University, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, the University of Konstanz and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. It included a technical examination of his work, as well as art-historical, stylistic and historical analysis. The project led to some spectacular discoveries and new insights into Bailly’s life, work and practice.

This book, which presents those insights, is published to coincide with the exhibition David Bailly – Time, Death and Vanity at Museum De Lakenhal in 2023. The centrepiece is the 1651 panel Vanitas Still Life with Portrait of a Young Painter, Bailly’s last known work. This extraordinary work from Museum De Lakenhal’s collection, full of symbolism and references to transience, continues to fascinate us almost 400 years after it was painted. Vanitas symbols like soap bubbles and wilting flowers, the refined technique, the mystery of the many portraits in the painting and the story of the painter himself – there is so much to discover in this picture. In the exhibition, Vanitas Still Life with Portrait of a Young Painter will be surrounded by other unique works by David Bailly and his contemporaries, including Rembrandt, Jan Lievens and Gerrit Dou. We are grateful to our fellow museums and their staff for their willingness to loan these works of art, share their knowledge and make items from their collection available for study. Many thanks also to the private individuals who opened their doors to our curators and experts and loaned us their artworks for the exhibition.

I should like to express my particular gratitude to curators Christiaan Vogelaar and Janneke van Asperen for their infectious enthusiasm for the work of Bailly, which inspired the staff of Museum De Lakenhal to put so much effort into this major project, and attracted a unique group of experts to participate in the study. Many thanks also to Rudi Ekkart, co-editor of this catalogue who, with his profound knowledge of Dutch portraiture and his critical eye, interpreted Bailly’s portraits and attributed several new works to him. I would like to thank the other authors, Nathan Daly, Erma Hermens, Marika Keblusek, Karin Leonard, Fred G. Meijer and Carla van de Puttelaar, for their input to the research, which has enriched the knowledge of our collection. Also indispensable were the expert efforts of editorial team Aukje Vergeest, Caren Apers and Janneke van Asperen, image editor Caren Apers, designer Harald Slaterus and publisher Marloes Waanders. Also a great help have been Taco Dibbits, Claire van den Donk, Frits Duparc, George Gordon, Lia Gorter, Bob Haboldt, Kathrin Kirsch, Friso Lammertse, Eva Michel, Pieter Roelofs, Cécile Tainturier and Gerdien Verschoor.

Finally, I would like to give special thanks to our patrons from the Lucas van Leyden Patronage. With their involvement and financial contribution, they continue to make the extraordinary projects of our museum a reality, such as this publication. This is the first book that has its entire focus on both the life and work of David Bailly. It represents an important step in the deciphering of his work in an art-historical context, and towards broader public recognition of Bailly as an important seventeenth-century painter.

Tanja Elstgeest Director, Museum De Lakenhal

It was his final work, the Vanitas Still Life with Portrait of a Young Painter of 1651, that afforded David Bailly a prominent role in the history of art. The exceptional quality of both the portrait and the still life is evident, and the combination of these two genres unusual. But it is above all the interpretation of this enigmatic painting that has exercised minds for decades. Is the painter David Bailly himself, and does it then follow that the elegantly dressed woman in the oval portrait on the table must be his wife, whom he had married in 1642? And is the mysterious phantom image of a woman behind the flute glass a deliberate addition, or an overpainted portrait that has re-emerged over the course of time? To what extent is the vanitas still life on the table a personal reference to the transience of the life of the painter himself?

These questions, which have been pondered for so many years, have prompted Museum De Lakenhal, which purchased the painting in 1967, to organise an exhibition on the artist, and to subject both his drawn and painted work to closer examination. Bailly’s body of work as a whole has not been studied since Josua Bruyn’s groundbreaking papers published in Oud Holland in 1951. The 1651 vanitas still life was subjected to further technical examination when it was on loan to the Rijksmuseum while Museum De Lakenhal was closed for renovation and the building of an extension (2016-2019). Erma Hermens, who was Rijksmuseum Professor of Studio Practice and Technical Art History at the University of Amsterdam until early 2022, and is now director of the Hamilton Kerr Institute in Cambridge, performed a thorough technical examination of the panel. She publishes her findings for the first time in this book, in a paper co-authored by Nathan Daly, research associate at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Karin Leonhard, professor of art history at the University of Konstanz, specialising in Dutch art history and theory, considers the wide-ranging and often controversial interpretations of the work that have appeared since it was first published by Paul Mantz in 1860. The reading of the portraits in the vanitas still life and the link between Bailly and the Steenwijck brothers are explored by art historians Carla van de Puttelaar and Fred G. Meijer. Marika Keblusek, lecturer in art history at Leiden University, has fleshed out the biography already sketched by Josua Bruyn. Rudi Ekkart, former director of the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague, and a leading expert on Dutch portraiture, has investigated Bailly’s rarely studied portraits. Bailly’s selfportraits and portraits of artists and academics with whom he was acquainted are the subject of the essay by Janneke van Asperen, who has been the curator of old masters at Museum De Lakenhal since 2021. Christiaan Vogelaar, her predecessor and the originator of the idea for the exhibition, has focused on Bailly’s vanitas paintings and particularly the 1651 vanitas still life.

In all honesty, we have to say that this new research has not always produced unequivocal conclusions, particularly as regards the identity of the painter in the vanitas still life and of the woman in the oval portrait beside him. The essays in this book consider Bruyn’s suggestion that these two individuals are Bailly himself and his wife Agneta. Some support his hypothesis, while others raise doubts. Despite the initial goal of using science to finally solve the riddle, this publication in fact raises new theories as to their possible identities. But the authors take solace from the fact that this book summarises past controversies, presents new arguments and provides access to a lot of new material.