9 minute read

Minotaur

from The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center Spring 2011 Press Book: Select Previews and Reviews

by umd_arhu

UMD SCHOOL OF THEATRE, DANCE, AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES: MINOTAUR

Advertisement

ENTERTAINMENT & LIFESTYLE, THEATER 'Minotaur': Mythology, muckraking, mincemeat

April 15, 2011 - 01:56 PM

By Maura Judkis

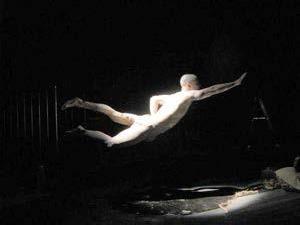

Courtesy Izumi Ashizawa

Playwright Izumi Ashizawa is mostly a vegetarian. She doesn’t eat meat in America, but occasionally does in her native Japan, or “If the animals are treated right.” But neither animals, nor humans, nor half-animal-half-humans are treated well in her debut of Minotaur, a performance piece that examines immigration and ethics

through the ancient Greek myth of the Minotaur, reimagined in the American slaughterhouse industry of the 1920s, and performed in the style of traditional Japanese physical theater.

While Ashizawa’s work is often inspired by mythology, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” was an obvious inspiration for the show. Besides the surface connection of inhumanely-raised beef – the Minotaur, product of a liason between a queen and a bull, grew up sequestered and feral in the labyrinth – there’s a parallel to be drawn between the legend human sacrifices that the citizens of Athens sent to Crete to appease the monster.

“If you take a look at a map of Chicago slaughterhouse, it looks like a maze itself. Chicago also looks like a labyrinth at the time,” says Ashizawa. “These people from Eastern Europe, Poland [who worked the slaughterhouses], they're treated and discarded almost, as a carcass.”

The Minotaur was eventually conquered by the warrior Theseus – but he never would have found his way out of the labyrinth without the help of the princess Ariadne, who helped him mark his trail through the maze with a ball of string. Though it’s one of the best-known stories of Greek mythology, Ashizawa says that the Minotaur has a place in Japanese mythology as well, in their half-bull, half-man creature of UshiOni. Scholars theorize that the legend traveled to Japan along the Silk Road.

“I think that any kind of mythology, even Mesopotamian or Egyptian, somehow connects people,” says Ashizawa. “The old mythology is a different world, however we face exactly the same problems, or similar problems. That's why I usually use mythology as a source.”

Her blend of East and West extends to the stage design, which is in the form of a classical Greek amphitheater, but rotates sets as traditional Japanese Noh theaters do, maintaining a trickle of blood that runs down the stage in every scene. The actors’ movement training comes from Ashizawa’s background in Noh, Kabuki and martial arts, and special effects are orchestrated through puppets that also qualify as costume pieces. Each puppet is a fragmented body part chosen, says Ashizawa, “To represent the fragmented psychological state of heroine Ariadne’s mind.”

Ashizawa doesn’t aim for Sinclair-style muckraking in her work – she says it’s a suggestive experience that leaves it up to the audience to draw their own conclusions about any parallels to contemporary immigration issues.

“This is the type of theater where we don't give the exact answer. We suggest and we show, and the audience thinks,” says Ashizawa. “That's probably the thing that we want them to have: A strong feeling from their guts that I would like them to shake.”

Minotaur will be performed at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center April 15-

23.

Poet Karren LaLonde Alenier, as the Dresser, addresses what's underneath the art.

A Trip into the Minotaur's Maze Circa 1920, Chicago

Pop quiz: did you read The Jungle by Upton Sinclair and if you did, were you appalled but riveted, maybe outraged? If you are socially engaged, seek artistic work that makes you think, then the Dresser suggests that Izumi Ashizawa's adaptation of the myth of the Minotaur, which is set in the 1920s stockyards of Chicago might be worth your time and money.

The Dresser was taken behind the scenes at the Clarice Smith Center for the Arts to talk to Ms. Ashizawa and two of the principle actors: Nick Horan and Claudia Rosales. What she learned is the play features Japanese movement (Ashizawa was trained in the arts of Japanese Noh theater) and unusual puppetry.

The stage is configured in the shape of a steer's hoof. The lighting features "red outs." The original music comes from a Greek contemporary composer, Simos Papanas, who is not a Minimalist but not a Schoenberg either.

The ninety-minute performance about modern day immigration problems runs without intermission. Director Ashizawa hopes to shake the inner core of those who attend. Because every element of this theater work, which features the same group of outstanding graduate

students the Dresser saw in the Mendacity Festival, counts--there is no pretty fluff added, the Dresser believes seeing the play once might hook the viewer into seeing it again.

Minotaur opens April 15, 2011.

Photo Credit: Izumi Ashizawa

Posted by Karren LaLonde Alenier on April 11, 2011 6:12 PM | Permalink

The Diamondback > Diversions

Slaughterhouse live

By Andrew Freedman Sunday, April 17, 2011

To many, the stories of Greek mythology are set in stone.

But don't tell that to Izumi Ashizawa, assistant professor of movement and acting and the writer and director of Minotaur, currently being performed by this university's theatre, dance and performance studies school.

Ashizawa has taken the story of Greek hero Theseus and pushed it into the era of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. The play interweaves the classic story with Chicago's meatpacking industry in the 1920s.

It is in a slaughterhouse where we see Thes (Rob Jansen) slay a re-imagination of the minotaur, the Unbelievably Huge Man (Shane O'Laughlin), and escape to meet the daughter of the evil Slaughterhouse Tycoon Minos (Dave Demke), Ari (Claudia Rosales), whose long hair would put Rapunzel to shame.

It is after the classic battle against the minotaur that we begin our story, and it's certainly where things get interesting.

Jansen plays Thes like a man possessed, pouring his soul into the character's dark side as he cries of the "endless forest of carcasses." We also get a gripping performance from Nick Horan's crazed portrayal of Dion, the king of an island where Thes and Ari go to escape Minos. While the entire cast's acting in Minotaur as a whole is authentic (and sometimes haunting), it is the scene between Thes and Dion that steals the show.

Just because the performances are strong doesn't mean the play always makes sense. Ashizawa gives her audience a lot of credit — she doesn't spoon feed the tale of Theseus to them. However, a small refresher (which you can get, for the most part, through the program notes) is helpful. Some moments, such as the story-within-the-story of the Scorpion SHE (Caroline Stefanie Clay) and the Hunting Boy (James Waters) or the story of the Old Man (Armando Batista) are not completely clear.

Even so, the story, for the most part, is comprehensible without prior knowledge — a significant improvement from Ashizawa's last play at CSPAC, Gilgamesh.

There is a strong directorial connection to Gilgamesh: an emphasis on movement. One can tell Thes is cultured not just from the suit he wears but from the way he carries himself. Dion walks with his feet landing sideways and the slaughterhouse workers perform their duties with synchronized choreography.

There is one odd quirk in the direction. While most of it is over-the-top (and to great effect), some areas of the play seem hyper-sexualized. The women of Dion's island (Teresa Ann Virginia Bayer, Olivia Brann, Anna Lynch, Whitney Rose Pynn and Anupama Singh Yadav) roll and crawl around the floor for several minutes in what seems to be orgasmic ecstasy around the Naked Chess Boy (Greg Mack). Also, Ari has a moment where she discusses death as a lover and touches herself in a sexual

The moments are fascinating to consider, specifically in context — Ashizawa didn't do this without reason — but it can also be distracting, and sometimes there is just too much of it.

Minotaur offers more than just strong performances. The set is dark and dank — the slaughterhouse becomes a character, always in the background of the story. The slaughterhouse is built with brick walls and wooden flooring with a pool of (obviously fake) blood that leaks down the side. As you walk in to the Kogod Theatre, make sure not to step in the resulting puddle.

Throughout the play, we see even more great technical aspects, such as cow hides riding on racks around the set and the fantastic costume used to make the Unbelievably Huge Man unbelievably huge.

The costumes for the rest of the cast are more or less spot-on. The period costumes are completely believable, such as Minos' mafia-esque suit, the bloody aprons and uniforms of the slaughterhouse workers and Dion and the island women's tattered shawls. There are also some clever uses of black bodysuits to disguise actors in the darkness.

The lighting designers also deserve commendation as light is used heavily and to great effect in the show. Strobe lights are effective, but so is dim lighting and darkness. At times, the entire set is pitch black. The carefully controlled lighting design casts the dank atmosphere of the slaughterhouse upon the theater.

There is no reason to beat around the bush. Minotaur is a strange show, but also dark and often entrancing. Brief moments of confusion are present, which is unfortunate because the play as a whole — from acting and costumes to set and light design — is quite strong.

Minotaur is also something new. The idea might be well-tread, but it still tells a strong story. More particularly, this version tells an old story in a new way, which provides for interesting liberties in the adaptation.

Is it strange? Absolutely, but it's also fresh. Well, at least the play is — the slaughterhouse meat may not be.

Minotaur runs through April 23 at the Kogod Theatre in the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center. Tickets are $27 for the public, $9 for students.

afreedman@umdbk.com

DANCE

The Center’s reputation for innovative dance presentations continued to attract favorable attention from the media, with extensive coverage of visiting artistsNora Chipaumire and Lucinda Childs, as wellunprecedented coverage of TDPS dance faculty and students.

This season, dance students performed and collaborated with dance faculty Sharon Mansur, SaraPearson and Patrik Widrig in their multimedia production Danceworks, which wascovered in Dance magazine and the Washington Post. Additionally, dance critic Amanda Abrams used the performance as a launching point for a blog discussion of professional artists who also serve as university faculty. Nora Chipaumire’s February engagement received attention not only for the performance itself but also for engagement events surrounding it. And Lucinda Childs’s April presentation of Dance was the subject of a lengthy preview piece in the Washington Post by Pulitzer Prize-winning dance critic Sarah Kaufman, as well as multiple reviewsin campus and off-campus publications.