5 minute read

POWYS MATHERS: AN IMPRESSION

Before Edward Powys Mathers wrote the world’s most difficult literary puzzle Cain’s Jawbone, he was a cryptic crossword creator. Under his pseudonym ‘Torquemada’, his puzzles taunted readers of the Observer for over 15 years. His true identity was only revealed when he died in 1939. As well as earning the reputation for setting the world’s toughest crosswords, Torquemada was also delightfully creative: with many puzzles written in perfectly constructed verse or delivered as mininarratives to their solvers.

Unbound will be re-issuing Torquemada’s best crosswords, originally published in 1942, along with tributes to his life and achievements, one of which is this thoughtful testimonial by his friend and author John Dickson Carr.

Advertisement

One evening only a year ago, I met a man and made a friend. That is my only justification for writing these lines. If it were not so, to write even the briefest memoir of Powys Mathers would be presumptuous in one who knew him for so short a time. Of the poet and the scholar others can speak. But the wit, the punster, the good host and good friend, even the merest acquaintance could testify to the full; for we shall not see his like again.

Nor should any account of him be weighed down by too heavy words. No man was ever so quick to laugh at solemnities or puncture the high flown. I shall always remember Bill Mathers sitting by the open windows giving on the garden, his sleeves rolled to the elbows, a grin on his face and a pun in his head, preparing his own remedy for anyone who pulled a long face even at his own funeral.

It all began, then, with a detective story. This at least can be said with certainty: there has never lived a man with such a wide knowledge of sensational fiction. Torquemada of the Observer read everything that was being written. Bill Mathers was already familiar with everything that had been written. And he never forgot any of it.

He once said that in his youth he had two great ambitions: to make a perfect epigram, and to be a great detective. The first ambition he achieved a dozen times in an evening, and thought nothing of it; he was usually two jokes ahead of our slower wits. The second ambition he achieved by detecting, with such delight that you could almost hear him think, the crimes in the books, the crimes that were as easy-going as himself.

This mimic world was very real to him. It was not alone that he could tell you offhand the name of Sherlock Holmes’s tobacconist, or why Father Brown did not like hat-pegs. Every exploit of even obscure and halfforgotten detectives was known and docketed, ready to be discussed, with chucking analysis, as though these people lived next door.

There Has Never Lived A Man With Such A Wide Knowledge Of Sensational Fiction

Cleek, Ashton Kirk, Martin Hewitt, Gryce, Van Dusen, Thornley Colton, Violet Strange, Sergeant Cuff… how many of those dim detectives can you identify? There were only a few to Torquemada. He sat like a kind of Commissioner in the Scotland Yard of this cloudcuckoo land, gravely shaking his head over mistakes, and uttering words of praise for a bit of smart work. Do you remember that singular affair of the flaming phantom, now? And young Joseph Rouletabille, there: he did a good piece of work by noting the significance of the walking stick in the affair at the Chateau Glandier. So, because I happen myself to be fond of this ghostly Scotland Yard, we would talk on far into the night; until a kind of nostalgia came over us, and we would agree that the golden years of detection were past, and that they produce no such mental giants now as they did in the good old days.

Equally wide was his knowledge of ghost stories, of any tales of the supernatural and the horrific. He could quote page after page of the late M. R. James, that greatest master of the ghost story, who never cracked the whip or goaded the adjective. But his greatest liking, I think, was for the ‘semi-supernatural’ story – the spectral presence induced in all its terrors, only to be explained in a few words at the end. For the more mystic kind of ghost stories, the fog of words and the esoteric dreaminess, he had little use. He had (be it repeated) that strong sceptical intelligence which will have no truck with high-fallutin’. So he much preferred even his bogles to have their origin in a creaky shutter or a skilful trick. He was fond of those little-known tales of William Hope Hodgson, the Adventures of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder; the earlier stories of L. T. Meade and Robert Eustace; anything of what may be called a supernatural wangle. This attitude, I believe, is held by some connoisseurs of ghost stories to be rank blasphemy. Torquemada had read so much that he knew better.

These two things, the love of epigrams and the love of puzzles formed the essential texture of his mind. They always went together. He could turn a joke into a problem and a problem into a joke. The effect of his death can be measured by the floods of letters which poured into the Observer from those who were accustomed to solve his crossword puzzles. But one point in particular strikes out of them at anyone who has heard Bill Mathers talk at ease by the fireside. Every writer, however gropingly, expresses the same thing. He was Torquemada. They knew him. There was personal loss in this. And so they did know him; for even in a printed page, infusing life into it always, was the essential man.

The

Crossword Puzzles

He constructed his puzzles exactly as he talked. A pun or a play on words lurked always round the corner. The construction of those puzzles was with him a word-patience, a sort of game, at which his nimble intelligence was always playing; and one of his great enthusiasms, as all of us will remember, was for games of all kinds. The game might be so complicated that nobody could understand it: in fact, it frequently was. But, whether little cardboard figures were pushed about a board, doing heaven knows what, or whether we ourselves floundered through intricate manoeuvres of pencil and paper, he infused into it a gusto and richness of wit which made even the cardboard figures come alive. There was one of these figures, called Aunt Cora, of whom he was particularly fond – full biographical details supplied – and another named Snitkin. If there were no games he would invent them. And he invented them with the ease with which he created that fine old firm of publishers, Messrs. Crippen and Wainewright.

These are trifles. Possibly they should not be included here. But they are the essential parts of memory, the pictures that remain, of that vast, complex, gentle personality. His friends see familiar rooms:

Torquemada reading aloud a duel scene (‘Kirby or devil!’); Torquemada, in carpet slippers, looking for a place to hand a picture of Edgar Allen Poe; Torquemada brewing Christmas punch and commenting, about a detective story in which the victim is killed in a falling lift, that the real title should have been, ‘A Drop too Much’.

The chuckle is always there. He loved reading aloud, and hearing others read aloud. It might be serious – he had a fine voice for verse – but more frequently it was parody, and his tastes ranged from Ben Travers’s broad slapstick to the poisoned darts of Max Beerbohm. Savanarola Brown, so barbed and edged that only the intelligence laughed, was not more welcome to him than an account of Romeo and Juliet delivered in broad East Side Americanese.

It began, then, with a detective story. I went one evening to Park Hill Road to talk of such things, and made a friendship which it would only be ironical to describe as lifelong. Other of his friends, perhaps, are more fitted than I to describe the character of which I knew only one side. But that one side would have sufficed twenty men. It glowed and was alive with unforgettable kindliness. It was, and is, enough.

JOHN DICKSON CARR London, 1939

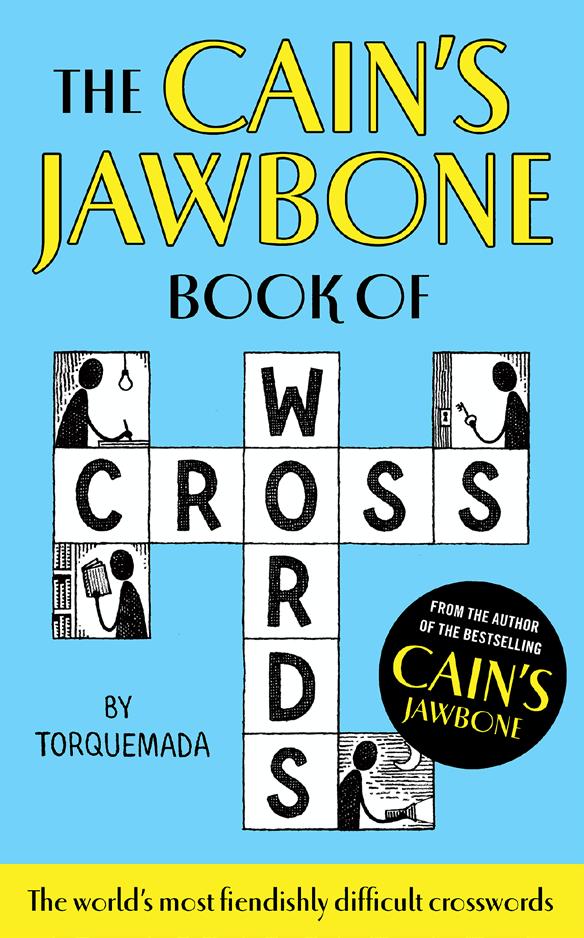

Find The Cain’s Jawbone Book of Crosswords on page 72