8 minute read

Up, up and away

from GOODWOOD | ISSUE 23

by Uncommonly

AND

Above, clockwise from top left: Klemm L.25 in flight; Focke-Wulf Fw 44J Stieglitz, top, and de Havilland Tiger Moth; and the 9th Duke of Richmond’s licence-built Klemm L.25 at Goodwood Aerodrome in 1936. Opposite page: Richard Menage in the cockpit of his 1941 DH82 Tiger Moth

Advertisement

UP, UP

AWAY

Richard Menage, whose 1929 Klemm L.25 will be on show at this year’s Revival, has spent decades restoring some of the world’s rarest and most beautiful vintage aircraft. But for him and other like-minded afi cionados, as he tells Alex Moore, it’s a plane’s history that makes it truly special

Just as some of the most committed car enthusiasts will always choose a barn-find doer-upper over a shiny new speed machine, so there are pilots for whom a modern plane just doesn’t cut it. For the small number who occupy this niche corner of the aviation world, it is vital that their plane should tell a story. And if it takes the better part of a decade to discover and restore it, even better.

“I was looking for a project,” says Richard Menage, 65, running his hand affectionately down the fuselage of his pride and joy, a 1936 Focke-Wulf Fw 44J Stieglitz, G-EMNN, parked in a hangar at Bagby Airfield in North Yorkshire. To his credit, the German biplane has been so lovingly restored, it could be fresh off the factory floor. Parked opposite is its British counterpart, a 1941 de Havilland Tiger Moth belonging to Menage’s close friend and great mentor, David Cyster, with whom he shares the hangar. In 1978 Cyster famously flew said plane to Sydney with little more than a compass and a stopwatch.

Menage found his “project” languishing in the Gillstads Bilmuseum in Lidköping, near Gothenburg, Sweden. He was specifically looking for a Stieglitz (German for goldfinch) – a training plane used by German flying schools and subsequently the Luftwaffe – and with the help of a crack team from the Shuttleworth Collection (home to a unique assemblage of historical aircraft), he managed to locate a plane he describes as “rarer than hen’s teeth”. It is one of only five remaining flyable German-built Stieglitz aircraft – the rest were scrapped after the war.

“The poor thing really was in dire straits,” recalls Menage. “It was 50-50 whether it could be salvaged or not, and ultimately it boiled down to whether the engine could be rebuilt.” Fortunately, he and Cyster knew a fellow enthusiast with an unflyable engine gathering dust, with whom Menage was able to offer a swap for the engine’s best cylinder. In the world of aircraft restoration, very little money changes hands. Spare parts are exchanged or IOUs are written, and so, with luck seemingly on his side, Menage trucked the aircraft back to his workshop and began slowly and meticulously dismantling the entire thing.

“To this day I remember Jean-Michel Munn’s sage advice to photograph and note the location of every item before removal, right down to the last nut and bolt,” says Menage. “This paid dividends when it came to refitting the components months, if not years, later.”

Each fitting had to be stripped to bare metal, inspected, subjected to non-destructive testing and repainted. Fortunately, the Stieglitz is well documented, with parts lists and manuals readily available, but the plane’s technical drawings are harder to come by. A few remain in the FockeWulf archives, now held by Airbus, and the Swedish and Austrian national aeronautical archives were able to help with some of the others.

When it came to reassembling the plane, Menage did seek some assistance, admitting, “I trust myself to maintain aircraft, but not so much when it comes to repairing them.” Henry Tuke, a retired precision engineer and a dab hand on the lathe and milling machines, replaced any spent parts; Sue Bland, a retired saddler, was drafted in to replace the cockpit’s perished leather upholstery; Joachim Altman, a dentist and horologist, serviced and recalibrated the instruments; and aero engine specialist Dirk Bende helped to reconstruct the engine. “The restoration project was made all the more interesting by the involvement of so many willing and helpful people,” says Menage. “Tracking down manuals, engineering drawings, spares and missing instruments was all part of the excitement.”

Five years later the Stieglitz triumphantly took to the skies. For the pilot and his family, it was a moment that had been a long time coming. Menage learnt to fly when he was 22, considerably older than his three sons, who’ve “been flying since they were in nappies”. He started in Cessnas but always had an interest in military aircraft, attributing it to the fact that “Guy Hamilton’s Battle of Britain [1969] was shot over my school [St Peter’s Prep School, Seaford] and we grew up on a diet of Commando comic books”.

So no one was too surprised when in 1981, he returned from a Christie’s auction of Sir William Roberts’s collection in Strathallan, having acquired a Miles M.17 Monarch, G-AFJU, for the discount price of £50. “It cost £400 to transport it home, “grins Menage. “Only for the inspector to turn round and say, ‘I’m sorry, Richard, but basically the glue’s had it – it’s a major restoration job.’ Sadly at the time I had no money, so I sold it to East Fortune [National Museum of Flight].”

Today his business acumen is rather more discerning – he founded a protective textile firm Industrial Textiles & Plastics Ltd (ITP) 30 years ago – and when it comes to purchasing aircraft, his priorities have changed. “As a young pilot, you’re more into touring and aerobatics and planes that are capable of doing those sorts of things,” he explains. “Whereas nowadays I’m more interested in rarity and history. Where was a plane built? Who flew it? And who owned it?”

In the hangar on his farm a few miles north of York, Menage keeps another two planes of “extraordinary provenance”. The first, a 1941 DH82 Tiger Moth, G-ASPV, was the plane in which family friend and distinguished Second

Below left: Richard Menage at work on his Klemm L.25, which will be on display at Goodwood Revival this year, in the hangar at his Yorkshire farm. Below right: Menage’s de Havilland Tiger Moth at the farm’s airstrip

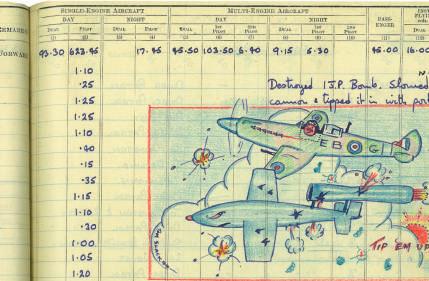

Below, from top: Menage’s immaculate 1936 Focke-Wulf Fw 44J Stieglitz in the hangar at Bagby Airfield; Terence Spencer’s logbook, with his illustration of a manoeuvre called “turtling”, whereby Spitfire pilots would tip the wings of V-1 flying bombs, sending them off course

World War fl ying ace Terence Spencer learnt to fl y. During a cinema-worthy military career that included escaping from a POW camp (Spencer’s autobiography is justifi ably entitled Living Dangerously), he entered the Guinness Book of Records for the lowest successful parachute jump ever recorded. In 1945 his Spitfi re was hit by enemy fi re at a height of just 30 feet but as it broke apart, his parachute somehow deployed, landing him battered but alive in the Bay of Wismar – though he was captured moments later.

Recently, Menage had a close call of his own in Spencer’s Tiger Moth. After fl ying with the Tiger Nine Formation Team at the Midlands Air Festival, he was forced to make a precautionary landing at Leicester Aerodrome when the airframe and rudder pedals started vibrating. On further investigation, the cause was a sticking valve in the No 1 cylinder of the Gipsy Major engine. “It’s all part of fl ying these old ladies,” he chuckles. “But I must say, the few minutes it takes to land can feel like hours.”

The second plane in the hangar – an immaculate 1929 Klemm L.25, G-AAUP, which Menage will be exhibiting at Goodwood Revival this year (and which his wife, Alison, has aff ectionately dubbed “the fl ying lawnmower”) – is currently the 16th-oldest plane on the British register. “The original logbook reveals the interesting history of the previous owners and aviators who fl ew this sedate and dignifi ed machine,” says Menage. “I’ve managed to trace eight of them, including a quite remarkable lady, Miss Nancy Bagge, the second of fi ve siblings known as the ‘Flying Sisters’ from Gaywood Hall, King’s Lynn.”

To see Menage recount the stories of past owners and pilots of yesteryear is to see a collector who cares as much about preserving history as he does about getting his aeronautic kicks. He accepts that his fl ying days may be dwindling – “I’ll fl y as long as I can pass my medical” – but insists that he’ll continue to restore planes for as long as he can. In fact, he’s already halfway through restoring a second Stieglitz – “a historical gem” – one of only two surviving examples used by the Luftwaff e. He reckons it will take a few more years at least, adding, “They always say with aircraft restoration that you’re 90 per cent there with 90 per cent to go. The fi nal stages are always the trickiest.”

What does Alison, a non-fl yer, make of her husband’s passion? “Let’s just say it’s not surprising that many pilots are on their second wives,” she jokes, goading him. “It’s allconsuming. I am supportive, but there surely comes a point.”

Are we close to that point? “Well, we’ve just had our 40th wedding anniversary, so probably not that close. I must admit, Richard’s not like most other pilots…”

The all-new Mercedes-AMG SL