6 minute read

He’ll Take Paris, The Historic Virginia Village

He'll Take Paris, The Historic Virginia Village

By John Sherman

Advertisement

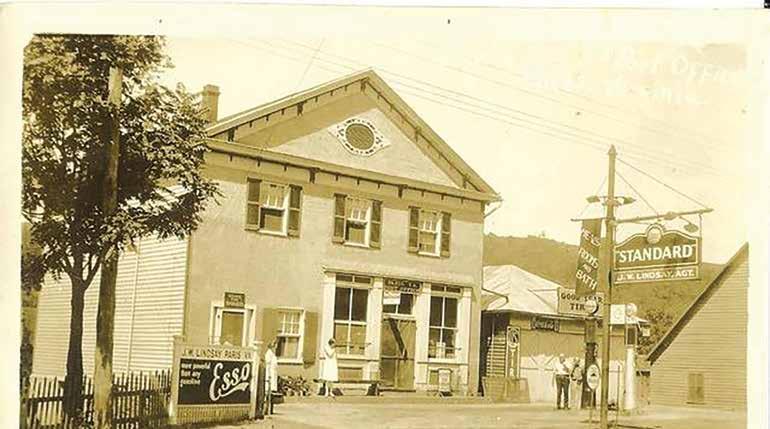

The Lindsey Store and post office back in the day.

All the old timers are gone, along with their memories.

Shanghai Lloyd, Hump Adams, Harvey Turner and Calvin Thomas were still alive when my wife, Roma, and I moved here in 1984 with the intention of opening a country inn. Since that time, only one new house has been built. And only two of the then citizens are sill here. At 80, I’m the second oldest in the village. We all gathered to sing “Happy Birthday” last July as Suzie Pennick turned 90.

By my reckoning, of the 30 houses in the village, about two-thirds were built before the Civil War. And less than 30 of us wake up here each day. Of the 15 or so Parises in the nation, ours is the smallest. The village has two parallel streets, Federal and Republican. Until about twenty years ago, Republican Street (known as “Back Street”) was Black. Federal Street remains White.

Betty Adams was the post mistress when I arrived. The post office was in her basement with hanging laundry and an exercise bike and was the center of village news. Whose daughter got married. Who was sick and would welcome food. And always the water problem.

“It was a friendly meeting place where all private people met,” remembered Ms. Pennick from Republican Street, where mail is now delivered into lock boxes.

I found a letter tucked away in a closet addressed to “Monsieur le Maire, Paris, Virginie.” It was dated 1951, an invitation to all American mayors of Paris to fly in for a week as guests of the French government to celebrate Paris’s two millennia anniversary. Sadly no one in the Post Office spoke French.

When Betty retired in 1990, the village lost that center and, with it, our integration—-both racial and social. A terrible loss.

Mike Carr and his wife are the fifth generation to live in the house his great uncle built. His greatgreat grandfather showed up in Paris in the 1840s with two slaves. His grandmother, Gadora Byrd, a recluse, lived in the house for more than 60 years and was always reading. Every Thursday she was driven to Middleburg with stops at Safeway and the library.

Although I had been living in the village for five years, I only met her once, grocery shopping. We chatted briefly. She told me she grew up with Civil War veterans. I smiled. She sensed my disbelief. “Do the math,” she snapped. I did.

Paris is stuffed with history. Perhaps the earliest account: “Bitterly cold and windy weather on the mountain forced Colonel Washington to return from the surveying field to Ashbys Tavern standing within five miles to the south on the 10th of March (1748). The 12th was spent entirely inside the tavern.” Washington was 16. The tavern was destroyed by a runaway truck in 1939. The only remaining artifacts are the columns fronting the Ashby Inn, once a rectory.

The aftermath of the Revolutionary War brought the story of Hessian prisoners from the battle of Trenton marched through the village headed west toward Winchester.

The name Paris is surrounded by myths. The most standard story has Thomas Glascock, who fought in the Revolutionary War with General Lafayette, named the village Paris in his honor. The Virginia legislature chartered the village Paris in 1810. Given the dates of the marquis’ visits to America after the war, it doesn’t sync.

Glascock owned the land that is now Paris. His original plat showed a vision for 14 streets. The lots laid out along Federal and Republican remain today. Most of the village’s houses were build in the 1820s; the inn in 1829.

From Wikipedia: “The market town prospered in the early 19th century, but lagged in the middle of the century because none of the newly constructed railroads went through it. It was last listed as an incorporated town in 1830. In 1835, Paris had several taverns, three stores, a school and a church shared by several denominations, as well as 25 dwellings, two saddlers, two blacksmiths, two wagon-makers, a tailor, a cabinetmaker, a chair-maker, a turner, a wheat fan maker and three boot and shoe factories.”

The population, according to the 1835 census, was around 200, compared to our diminished 30 today.

Sign of the times at Trinity Methodist

A long view of Federal Street heading north.

Looking north on Federal Street today.

The village’s greatest historic note came on July 20, 1861 with the arrival of Confederate General Thomas Jackson with his lead brigade of 2,500 men. Their orders were to reinforce the army of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard who was about to engage Union forces in what is known by the south as the First Battle of Manassas, and by the north as Bull Run. It was there that Gen. Jackson earned his sobriquet “Stonewall.”

When Jackson was told sentries had been posted, he reportedly replied, “Let the poor boys sleep. I will watch the camp.”

The next morning, Jackson’s remaining troops marched south to Piedmont Station (now Delaplane), where 11,000 men were put on box cars and flatbeds to be hauled by the Manassas Gap railroad right onto the battlefield. It was the first known transport of troops by rail.

Today the houses of Paris tell their own history. At the far west end of Federal Street is the house of Dr. Thomas Settle, called to Charlestown to pronounce abolitionist John Brown dead after his hanging. He spent the war as a field surgeon.

“When I arrived in this village in 1970, many of the buildings were ramshackle,” recalled John Miller, the present owner. “Between the opening of the Ashby Inn and the closing of the street, Paris began to change for the good.”

Next door is what used to be a tavern and way station where horse teams were rotated to make the climb through Ashby Gap. At the time, Federal Street was a major east-west thoroughfare leading to the western frontier. The two-lane street became Route 50 until it was rerouted in 1957.

Across the street stands the house where John Mosby allegedly eluded two Union soldiers waiting outside.

Next door to me is the old Lindsey store which sold groceries and sundries and, where, the story has it, George Patton used to buy hunting hounds. The two Esso pumps are long gone.

Up the street, between the inn and the church, is the Slack store which conveyed with the sale of what is now the inn. The potbelly stove is gone, but the metal plate remains. The heart pine shelving was reworked to make the bar and benches in the inn’s taproom. A local newspaper piece reported that one of the storekeepers committed suicide inside. Not the first shooting death in Paris.

Perhaps the most interesting building lies at the head of Republican. It reportedly was built by Quakers and deeded to the village as a non-denominational meeting house by Thomas Glascock. It was used as a hospital where medals were found nailed to its walls after the war. Around the turn of the century it became school for Black children.

“My husband, Felton, went to that school,” remembers Ms. Pennick who came to Paris 60 years ago. “It was a very different time. There was no electronic music. We had to make our own music.” She is the only Black resident whose daily walk takes her up Federal Street. She exchanges news with passersby.

And George Washington? Well, apparently he went on to sleep around.