6 minute read

Remembering a Legendary Fauquier Attorney

Remembering a Legendary Fauquier Attorney

By John T. Toler

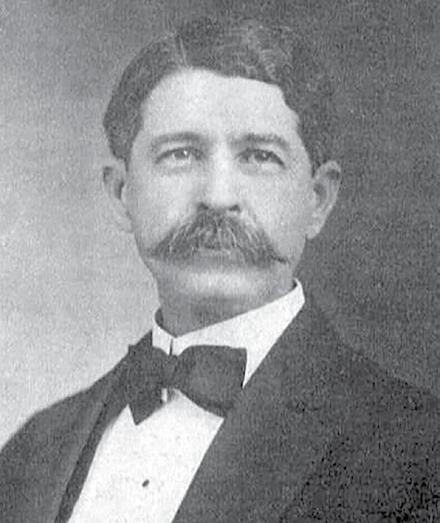

Over the years, a number of distinguished attorneys have called Fauquier County home, but few have had as long and varied a career as Major Robert Augustus McIntyre (1862-1952). His name appears in many newspaper articles and countless court documents from the early to mid-20th century.

Robert McIntyre was born in Marion, South Carolina, the son of Scottish immigrant Col. Charles McIntyre and Martha Wayne Murdoch McIntyre. He came to Warrenton as a young student at Bethel Military Academy, where he studied law under Major A. G. Smith. He passed the bar in 1883 and married Major Smith’s daughter, Elizabeth Blackwell Smith (1860-1940).

The couple moved to South Carolina, where Robert practiced law until returning to Warrenton in 1886 to serve as assistant principal and Commandant of Cadets at Bethel under Major Smith. By 1890 he was largely in charge of the academy, and in 1892 succeeded Major Smith as superintendent. At that point, McIntyre also acquired the title “Major,” by which he would be known for the rest of his life.

Not long after the death of his father-in-law, McIntyre paid off the debt he owed to the Blackwell family for the BMA property. At the academy he taught classes on the law. He continued in charge of the school until 1902, at which time he focused on his legal career and state politics. Bethel closed in 1911.

McIntyre was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for two terms, 1929-1933. He served on four powerful committees, including Privileges and Elections, Schools and Colleges, Militia and Police and Federal Regulations and Resolutions.

In Richmond, he fought bills that would require public school students to pay for their textbooks, as well as a bill that would have mandated the tuitions be collected by the state’s high schools. Other action included serving on the delegation that supported repeal of the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) in 1933, personal responsibility in the design of the Seal of Virginia (Sic Semper Tyrannis).

For many years, the McIntyres lived at Argyle on the Alexandria Pike in Warrenton, where they raised three children, Elizabeth Carter Blackwell, Agnes McIntyre Clarke and Robert C. McIntyre. They also owned Springfield Farm, a 227-acre property in Broad Run.

McIntyre had his law office in Warrenton in the same building once occupied by attorney and Civil War General H. William Payne. Involved in his community, McIntyre was a member of the Fauquier Bar Association, Mt. Carmel Masonic Lodge, Black Horse Chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and St. James Episcopal Church. He was a director of the Chamber of Commerce and Fauquier National Bank.

Throughout his legal career, McIntyre was known as an effective attorney, on occasion representing both parties in a dispute.

According to the late John K. Gott, McIntyre once represented his uncle and another man, both named “Glascock” in a civil case. Their names only differed by their middle initials, and the filings sent to the parties involved were switched, resulting in an embarrassing situation. But McIntyre still managed to settle the case.

Over his long career, McIntyre won acquittals or non-capital punishment for 76 accused murderers. His only loss was in 1943 – at age 81 – defending Loudoun County resident Thomas William Clatterbuck. He was accused of killing five people— three members of the Morris Love family, and a farm worker and his wife at the Love’s farm near Purcellville.

The killings took place on the morning of June 1, 1943, and Clatterbuck was arrested the next day. He was arraigned on June 14, with the trial set for June 30. Clatterbuck’s family, who had business dealings with McIntyre in the past, retained him on June 15.

There was a preponderance of evidence, Clatterbuck’s five-page confession, witness testimony and motive—a dispute over payment of a loan he owed Morris Love.

Presiding judge at the trial was J. R. H. Alexander, the son of John Alexander of Warrenton, who had served with Mosby’s Rangers. Prior to being appointed to serve on the bench, he served as Loudoun County Commonwealth’s Attorney. His son, John Alexander (1918-1986) is remembered as Fauquier County Commonwealth’s Attorney, as well as serving as a judge and also as Fauquier’s delegate to the Virginia General Assembly.

McIntyre was granted a request to re-schedule the trial to July 26. His defense strategy was twofold: Clatterbuck’s alleged overwrought mental state, supported by the testimony of mental health experts who believed that Clatterbuck suffered from dementia praecox, a form of insanity that prompts the sufferer to kill. He also claimed that due to pretrial publicity, Clatterbuck could not get a fair trial.

The legal wrangling continued until Sept.14, and was marked by testy exchanges between McIntyre and Prosecutor Charles F. Harrison. McIntyre characterized Clatterbuck as an “ignorant man,” and said the confession had been made under duress. His final argument was based on the premise that no sane person could have killed five people, proof that Clatterbuck was insane.

The jury didn’t agree and convicted Clatterbuck. He was sentenced to death on Sept. 24, with the execution to take place on Dec. 10. McIntyre filed a writ of error with the State Court of Appeals on Nov. 13, and the execution was postponed until Feb. 4, 1944.

Three reprieves based on the insanity plea were granted by Virginia Governor Colgate Darden, but after a review by the State Board of Mental Hygiene, the execution finally took place on June 16, 1944.

McIntyre’s perfect record of saving his defendants from capital punishment may have been broken, but over the next five years – until he retired from the practice of law in 1949 at age 87 – he continued to represent clients in criminal cases. These included three persons accused of murder, none of which resulted in execution.

A year after retiring, McIntyre endured a two year struggle with illness, dying at home at Argyle in 1952.