3 minute read

The Grand Ginkos At Dandy Blandy

The Grand Ginkos At Dandy Blandy

By Ronen Feldman

Historic preservation – check. Studying different types of plants – check. Educational opportunities for all different age groups – check, check, check!

Anne Marie Chirieleison, the newly named director of the Foundation of the State Arboretum at Boyce’s Blandy Experimental Farm, has a mouthful to say about its history as well as its collection of rare trees and plants, available to researchers and visitors alike.

Barely in the job for three months, the Fredericksburg native can discuss plants like a botanist and talk about the land’s history as if she had been there back then.

She realizes that the arboretum and the adjacent historic landmarks are an intersection of science and culture; an exploration of thousands of different trees and shrubs from all over the world and a look into Virginia’s past rolled into one.

“We work with researchers from the University of Virginia to study many nonnative plants, often distinguishing the ones that are good from those that are potentially harmful to their non-native environments,” Chirieleison explained. “We only plant the good ones.”

The arboretum is the only one of its kind in the state, and also has ties to the National Arboretum in Washington.

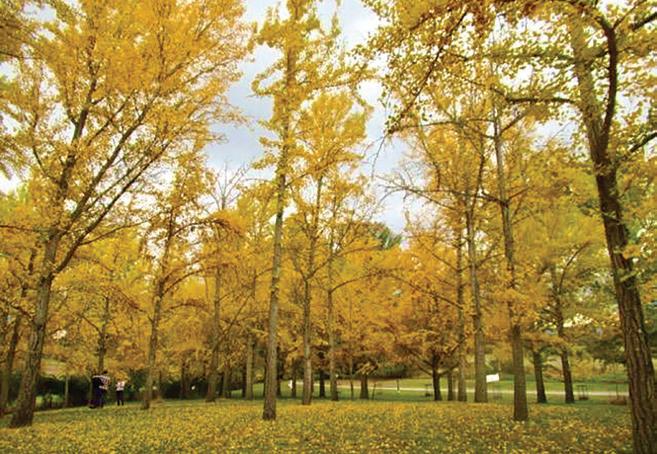

“The spotted lantern fly, for example, is an insect that was introduced by its host tree, the tree of heaven,” she said. “This plant, while beautiful, is terribly invasive, and so are the pests it attracts. And yet, the ginkgo tree, which is another non-native plant from East Asia, is perfectly harmless. This is the kind of research the arboretum is for.”

During the 1920s, the land was repurposed, but its history goes back long before it became the botanical hub it is today. The complex on which the arboretum operates was owned by the Tuleys, a prominent slave-owning family whose patriarch, Colonel Joseph Tuley Jr., began building the mansion known today as “The Tuleyries” almost a century earlier.

The family’s extensive travels through Europe have often been thought to be the inspiration for many of the mansion’s architectural features, including its four signature 28-foot Corinthian columns which were copied from the Tuileries at Versailles. The same is true of the old slave quarters, which were built in Dutch colonial architecture.

The Tuleyries remained in the possession of the family after the Civil War through Tuley’s niece, Belinda, who married a colonel herself, one Upton Boyce. After Belinda’s death, Boyce sold The Tuleyries to a wealthy New Yorker, Graham Blandy in 1905.

Blandy spent a fortune restoring the mansion, even recruiting famed Philadelphia architect Mantle Fielding and a former slave named Mosey, who worked for years repairing the stone walls. In the end, Blandy left 700 of the 900acre estate to the University of Virginia.

What used to be the slave quarters have been converted into laboratories and housing. The Tuleyries and the Blandy Experimental Farm were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and 1992, respectively.

“One major goal we have is to keep its architectural integrity intact,” Chirieleison said. “This place is dedicated to research, but we also offer a variety of K-12 programs and educational opportunities for adults. People also have the chance to connect with the arboretum personally, conduct native plant and bird walks, and visit and see our ginkgo grove.”