5 minute read

DIFFERENT DISCIPLINES, ONE GOAL

Interdepartmental research team seeks to understand how sea sponges affect their environment

By Krissy Vick

Advertisement

Off the coast of Belize lies a little postage-stamp sized island called Carrie Bow Cay. There, the Smithsonian Institution’s Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystems Program is providing opportunities for UNCW students and faculty to further their cutting-edge research on sea sponges and how they affect the overall health of coral reefs.

Carrie Bow Cay

Smithsonian MarineGEO

An interdepartmental seven-person team representing UNCW’s Center for Marine Science and the departments of Biology and Marine Biology; Chemistry and Biochemistry; and Earth and Ocean Sciences will embark on an expedition next spring to gather sponge and water samples from the Mesoamerican Caribbean barrier reef next to Carrie Bow Cay.

The research, federally funded by a new National Science Foundation grant of nearly $1 million, is at the forefront of coral reef ecology exploration. UNCW scientists want to know more about what sea sponges are doing to their environment as they process the large volumes of seawater they pump every day.

“This work represents leading research to address basic but unknown questions about how reef ecosystems – which are critical for biodiversity – function,” said Dr. Ken Halanych, executive director of UNCW’s Center for Marine Science. “One of the novel aspects of this grant is scientists from several different disciplines are coming together to address the same issue from multiple different angles.”

Principal investigator Dr. Wendy Strangman, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and her team, Dr. Joe Pawlik, Frank Hawkins Kenan Distinguished Professor in Marine Sciences; Dr. Winifred Johnson, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry; and Dr. Ralph Mead, professor of Earth and ocean sciences; collaborated on the research proposal.

“We know that sponges are taking over the reef as coral health declines,” Dr. Strangman said. “Caribbean reefs of the future are likely going to be dominated by sponges, so we are trying to understand their impact on the nutrition in the seawater around the reefs.”

A giant barrel sponge pumps fluorescein dye on a reef in the Bahamas Islands.

J.R. Pawlik

The team will gather water samples before and after they are processed by sponges and bring samples back to the CMS labs to learn more about what dissolved compounds the sponges are absorbing and what effect it is having on nutrients and other chemicals in the water column.

Dr. Pawlik compares these dissolved compounds to sugar added to a cup of hot coffee. The sugar dissolves; however, the compound still exists in the liquid and can be absorbed as food, measured and analyzed. In previous studies, Dr. Pawlik’s students determined that most of the diet of giant barrel sponges on Caribbean reefs is made up of dissolved compounds, but the identity of these compounds remains largely unknown.

The team will also develop an outreach component of the project that will share their marine science knowledge with Wilmington community groups such as UNCW MarineQuest summer programs.

Each of the four investigators brings a different set of skills to the project. For example, Dr. Strangman specializes in isolating and identifying more complex dissolved compounds in the seawater mix, while Dr. Johnson uses new techniques to quantify the simpler compounds that may play the largest role as food for sponges and other members of the reef environment.

The researchers will also study the role of seaweeds, or algae, on the reef. Algae produce a complex mixture of dissolved compounds, and the researchers want to determine the role of sponges in removing these compounds as they pump reef seawater.

Previously, Lauren Olinger, a Ph.D. student working for the last five years in both Drs. Strangman and Pawlik’s labs, discovered for the first time that sponges can absorb compounds called organohalides, often made by bacteria and algae. Organohalides include the elements chlorine and bromine, and many of these compounds are toxic. The team will continue building on Olinger’s breakthrough research to better identify these compounds and where they come from.

“I’m excited to see this research expand to our new collaborators,” said Olinger. “I’m also looking forward to transitioning from the role of student to one where I get to be a part of this team as a mentor to incoming graduate and post-doctoral scholars. Not many students get to be a part of a team that crosses departments. To go from chemistry to ocean science to biology is challenging but also really interesting and insightful.”

“The UNCW team’s Caribbean sponge research stands out as a collaborative project,” said Stuart Borrett, associate provost for research and innovation. “One of the best ways to discover new knowledge is to approach existing questions from many angles. This project will help us better understand our oceans, the systems within it, and human impact on those systems.”

While at Carrie Bow Cay, the research team will live in breathtakingly beautiful but primitive conditions—an open-air shack outfitted with four-inch mattresses on boards, a basic roof and the option of a composting toilet or an outhouse at the end of a small dock. Common sights during their two-week stay will be sea turtles nesting on the beach, fist-sized land hermit crabs that form a living carpet on the sands at night, numerous sharks that regularly bump into scuba divers while they work underwater, and unforgettable views of some of the most pristine reefs in the Caribbean.

“Once we return to the CMS labs at UNCW,” Dr. Strangman said, “then the real work begins: running samples through our analytical instruments and diving into the data that we generate to turn that into information we can use.”

J.R. Pawlik

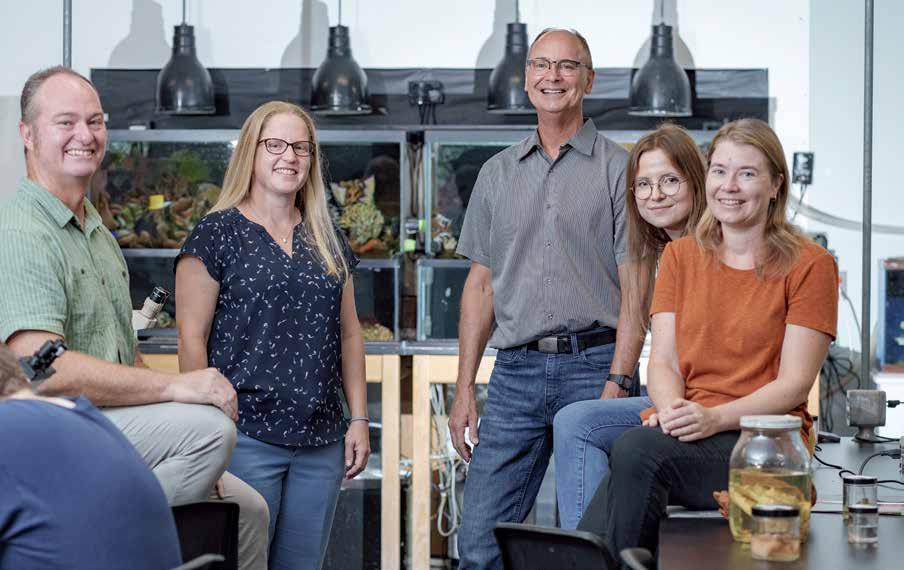

SEA Sponge Research Team

(L TO R) Ralph Mead, Wendy Strangman, Joseph Pawlik, Lauren Olinger and Winifred Johnson are collaborating to learn more about sea sponges.