4 minute read

Review: Devendra Banhart - MA, Fatima Jafar

from Under City Lights 2019/2020

by uncl

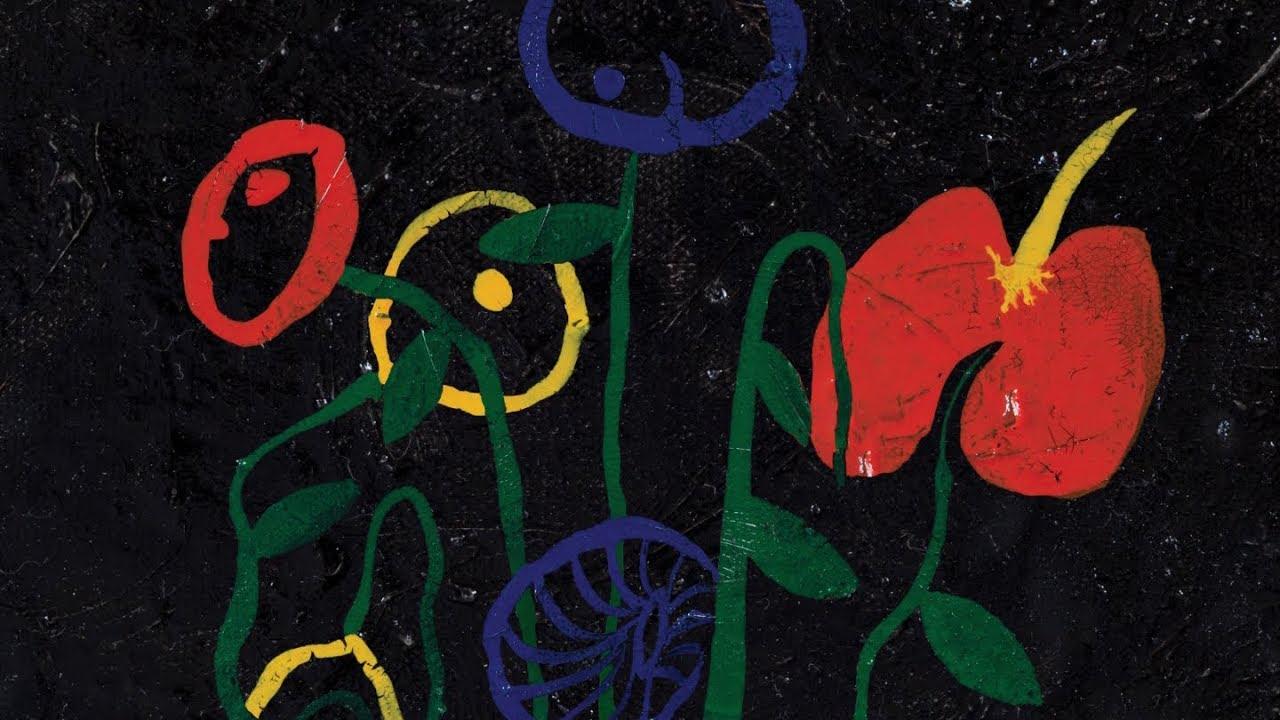

devendra banhart - ma devendra banhart - ma devendra banhart - ma devendra banhart - ma devendra banhart - ma

by Fatima Jafar

Advertisement

After many recurrent listens on the tube, in my bedroom, and on a plane over an ocean, Ma— the newest album of Venezuelan-American artist Devendra Bahnart— now comfortably sits in the position of being my favourite out of all of his works. The album, released in September 2019, is a confident and unwavering expression of love and grief, of mourning and reverence, that does not shy away from jumping into the sticky puddles of unending sadness or compassion that are often so hard to navigate, let alone verbalise. Banhart manages to write and compose thirteen songs that each seem to celebrate and lament various slices of the experiences of growing older, facing the deaths of friends and family members, and wanting to have a family— and a home— of one’s own.

The album begins with ‘Is This Nice?’, a song that juxtaposes plucky guitars, swelling violins and Banhart’s crooning vocals to open up the album with a deeply self-assured pace, sampling John Lennon’s ‘Beautiful Boy’ to create a lullaby-like rhythm that sets the scene for the themes of parenthood and nostalgia that continue throughout the album. In ‘Memorial’, Banhart’s eerie vocals seemingly echo in a hollow, sacred space as he sonically carves out a solemn elegy for a loved one who has died, using the tune of Leonard Cohen’s ‘One of Us Cannot Be Wrong’ as a backbone for approaching the theme of death. Banhart sings “I know it don’t work that way/But maybe you’ll come back some day”, encapsulating the sense of disbelief that comes with a life being cut short, and the inability to comprehend how death cuts through linear time with such a jarring stroke. In frequently referencing other artists throughout this album— from John Lennon and Leonard Cohen to Carole King in ‘Taking a Page’, Banhart imbues each song with a kind of authority and timelessness that bleeds throughout the album: we begin to understand that the themes Banhart covers in his songwriting are universal ones; emotions that countless artists have explored 8

before, and Ma exists as a reverent, heartfelt extension of their artwork, a pastiche built upon the varied layers of art that Banhart has experienced and enjoyed throughout his life.

The album is punctuated with lighter elements as well, such as in ‘Love Song’, where Banhart masterfully fashions a dream-like ode to falling in love. The horn arrangements and smooth rhythm are so fluid and effortless— the song shimmers, and slickly glides on as he sings “love like falling, without ever landing/… this is that feeling”. Banhart is in love with the feeling of falling in love, and constructs this song to commemorate that glittering sentiment. For me, the climax of the album is in ‘Taking a Page’, which bursts at the seams with the ironic phrases and vivid imagery that are typical of his work. His voice quivers with excitement as he asks ‘Do you ever think that colours say/Hey! Who’s your favourite human?’”. His wide-eyed curiosity bleeds into wry irony as he pokes fun at himself and the act of political performance, singing emphatically ‘I’m in my ‘Free Tibet’ shirt that’s made in China!’.

Banhart explores the tensions between emotions like unrequited love, sadness, anger— which seem universal, important, almost holy— and the constant presence of neoliberal capitalism in our lives today when he writes “All the death in my house makes it easy to shop online/Where the signal is strong, and the tech flows like wine”, in ‘Kantori Ongaku’. As Banhart tries to work through these visceral experiences of human life, he sits inside the confusing space between the primordial and modern: he writes “talking to an entity, made of endless night/I dream in TV dialogue, a world of shadow and light”— he is trying to understand these big, swelling relationships humans have with love, death, and God, in the context of an online world. Ma unfurls slowly, forgivingly, with each passing song, opening up gradually to the listener as Banhart dives deeper into his internal world. As I listen to this album more, it begins to feel increasingly personal, like a gift directly from Banhart’s hands to my own. The intimacy of many of his songs, and the way he writes emotion so unblushingly, is increasingly refreshing to hear. On his bandcamp, Banhart writes “Ma means ‘mother’ in pretty much every language. The album is kind of everything I would say to a child”. The album definitely feels like a celebratory cataloguing of human life, an almanac for growing older, intricately and tenderly composed by Banhart and left somewhere hidden, secret, for the listener to find and pick apart endlessly— whether on the tube, in a bedroom, or on a plane over an ocean.