10 minute read

CU Anschutz Dental Researchers

Molding the Future of 3D Printing

New materials could lead to better dentures, crowns, for patients

By: Matthew Hastings

Researchers at the University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine (CU SDM) are exploring a new frontier in 3D printing— developing new and more durable materials designed specifically for inkjet printing that can be made quickly and customized for each patient.

CU Anschutz Today sat down with Jeffrey Stansbury, PhD, and Kyle Sorensen (DDS ’25) to discuss their team’s research and what the future holds for 3D printing in dental medicine.

What is the current state of 3D printing in dentistry?

Jeffrey Stansbury, PhD: 3D printing is taking off quite dramatically in the dental profession. While it’s still a minority of what’s going on, it is rapidly building and is expected to eclipse the reductive milling approach for digitally derived dental device manufacturing in the not-too-distant future.

Right now, the materials are the biggest holdup, and that means that most of what’s being printed are dental models—replicas of the patient’s teeth for example. So, while there’s a big need to achieve higher-performance 3D printable polymers that are suitable for long-term clinical function, here we’re trying to leapfrog standard 3D printing techniques and enable the production of fully functional, strong and durable dental devices produced via multi-material inkjet printing

Kyle Sorensen (DDS ’25): In dentistry (with current 3D printing), we can do treatment planning, and you can get a record of the oral cavity as well. However, these study casts or molds aren’t used for direct dental application—it’s just a snapshot of the patient’s mouth.

You can use these casts and molds for various applications, such as designing surgical guides or to create guards that prevent teeth grinding. But the cool thing our project is forwarding is the potential to create intraoral devices, such as dentures, bridges or implants, that can be used on a daily basis by patients.

What are the benefits of 3D printing for dental applications?

Stansbury: It has so much benefit in terms of cost for delivery, speed of delivery, efficiency of material use, all sorts of things.

It’s the ability to 3D print very high-resolution, patient-specific design, which is just ideally suited to what 3D printing does. Mass customization is effectively the terminology for what 3D printing can accomplish. This would be permanent fixed or removable full dentures and removable partial dentures as well as crowns and bridges. It’s all about access to high-performance materials and the ability to 3D print those materials at very high resolution.

What is 3D inkjet printing?

Stansbury: It’s like an inkjet color paper printer, where you can get any blending of color on the fly. What we’re after is to be able to precisely jet droplets of multi-materials to get final unified polymers with localized control of material properties and aesthetic appearance to replicate differences between the gums and the teeth, for example.

This is different from conventional 3D printing used now in dentistry—vat-based printing—where you basically create an object layer by layer as it is lifted out of the vat. We are pushing out new materials that well exceed what’s possible with current vat-based printing and even more dramatically advancing jettable materials.

Can you explain the science behind these new materials and how they differ from existing 3D-printing materials?

Sorensen: Existing polymeric materials widely used in dentistry typically combine chemically bonded network structure along with secondary interactions that add to strength and toughness. A good example is urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) where the methacrylate groups react to produce the basic polymer network, and the self-association of the urethane groups contributes to the overall performance. However, UDMA doesn’t work for 3D inkjet printing because the association between the urethane groups that is positive in the polymeric state drives up the ink viscosity in the pre-cure state where the well-controlled small droplet jetting must take place.

Our new CU-patented materials are monourethane dimethacrylates (MUDMAs) that offer much lower viscosities than UDMA before polymerization yet present equivalent mechanical properties in the final polymers. We then coupled our MUDMAs with a second monomer that preferentially interacts with urethane groups to bring the ink viscosity down to the jettable range while also enhancing the reinforcing effects in the final polymers to achieve mechanical properties that appear to be well suited to clinical challenges in dentistry.

Another interesting result is that in addition to being much more tough and resilient than what’s currently available in the inkjet platform, our new materials are much more temperature tolerant so they won’t deform in shape when exposed to hot foods or liquids. So, in addition to being able to stand up more to normal dietary activities, these are very strong and flexible materials that can be accurately constructed using multi-material inkjet printing.

How will determining sizing and fit for these kinds of devices work going forward?

Stansbury: For the necessary digital design of a desired device, there are two approaches that you can take. One is you can do an intraoral scan with an imaging tool. Again, it’s not a wand, but you carefully move this around in the patient’s mouth and it captures a digital three-dimensional map of the soft and hard tissues there.

There aren’t many groups that are doing that right now, but that is another coming attraction for dentistry. What’s typically done now is you get a standard dental impression taken, you make a model of the mouth, and then you digitally scan that model.

It adds an extra step and time. At every step along the pathway, there’s some degree of uncertainty. So you get less and less precision as you make copies of copies going forward. But that’s how you get the three-dimensional digital image that then allows local or remote construction of the 3D printed device.

Dentists are good at thinking in both the positive and the negative dimension—making a negative model that creates a mold that I can fill, and then it becomes the positive. This always adds to my level of appreciation for what dentists do—to be able to think in those multidimensional terms, as well as being able to work with a mirror and do the right thing in the right place.

Where do you see your research going next on this topic?

Sorensen: I think the next steps would be to test the biocompatibility of these materials and make sure they’re safe for clinical application. And then also developing a wider range of materials with not just strong mechanical properties, but ones that are highly flexible, with lower stiffness.

You might want to have materials that are softer and more flexible on the gum surface. The next step would be identifying and developing materials for those applications as well. What’s interesting is that with a 3D inkjet printer, you can actually blend different materials with more extreme differences in properties to get an intermediate property.

So you might take something that’s really rigid and strong and blend it with something that’s a little bit more flexible. This is achievable because the droplets delivered by 3D inkjet printers are picoliter sizes. So you can create materials with graded functional properties that behave more similarly to biologic tissues.

Stansbury: Yeah, what I see coming is the ability to do both the aesthetic and the mechanical blending along with all sorts of different engineering aspects that take advantage of the multimaterial printing. So we can make something stiff in one direction, but flexible in the other, which again is not something that’s doable in any of the other current modes of 3D printed material manufacture.

This is opening lots of doors where design engineering, materials science and the 3D print processing can all be brought together and have some appliances for patients that are costeffective, rapidly developed and offer the best materials and performance available. If we can meet that, then we’ve solved a lot of problems. It’s very exciting.

Weslie Williams Program Assistant, Department of Restorative Dentistry

Weslie Williams has been part of the CU Dental community since birth. “I feel like I’ve grown up with this school. My mom worked here for 40 years in patient accounting, so she would take me to work with her sometimes after school. I went to high school just two miles down the road. I got to know a number of faculty before I even started working here.”

Today, Williams works directly with some of the same faculty, including Dean Denise Kassebaum, DDS, MS; Lonnie Johnson, DDS, PhD; Daniel Wilson, DDS; and others. She started part-time in the sterilization lab under Professor Emeritus Robert Greer, DDS, ScD, transitioned to a full-time position coordinating clinical schedules and finally made her way to the Department of Restorative Dentistry in 2015. From administrative assistant to program assistant, she’s grateful for the opportunity to grow continually in her career here at the school.

“When I first started, I didn’t know anything about dentistry. I’ve learned a lot in this department—I’m never bored. I’ve been most excited about venturing into digital dentistry.”

In addition to her daily responsibilities supporting faculty and students, Williams works with Associate Professor David Gozalo, DDS, MS, printing 3D models, milling in-house crowns and completing treatment plans in various software programs.

In 2018, Williams and Gozalo produced the first 3D-printed model at the school.

“In the restorative department, with digital dentistry, we have come a long way. We didn’t do any of this 10 years ago. We had one digital scanner, and now we have eight. We’re working in multiple different treatment planning software programs. We have 3D printers and a large milling machine in the school. All of this, plus the opening of the DASH, is a huge upgrade from where we started.”

And this is only the beginning. Williams, Gozalo and others are constantly experimenting with new ideas. The most recent challenge has been attempting to design and mill one-piece dentures. Williams said, “We essentially get a block of material that has both the pink for the gingiva and the white for the teeth. Then using 3D scans of the patient’s mouth, we can design and mill the complete denture without having to cement teeth and gingiva together.” This allows for a stronger denture with minimal manual work before delivery. “It’s just one piece, and it should fit perfectly in the patient’s mouth. That’s what we’re aiming for.”

Jaymil Patel, MBA Director of Infrastructure and Technology Services

How do you keep hundreds of devices up and running so faculty, staff, residents and students can continue teaching, learning, studying, researching, sharing and providing patient care with almost zero SDM systems downtime for more than a decade? It starts with the network servers. It also takes a village—a dedicated team led by SDM Director of Infrastructure and Technology (IT) Services Jaymil Patel, MBA.

“IT is constantly changing,” said Patel. “We are always looking at newer applications and processes to improve. In my 14 years here, the most impactful change I’ve been a part of was bringing more than a dozen physical servers from central IT to the SDM server room. This helps both clinical and non-clinical departments because we can manage everything ourselves and avoid unnecessary or excessive downtime. We’ve had no downtime since 2010 for the SDM systems we manage, and I’m most proud of that.”

Originally from India, Patel moved to the United States in 1999 and earned his bachelor’s degree in computer and information sciences with a focus on management. When he first came to the SDM in 2009, he was the third employee in IT and only worked part-time as a temporary hire. The central Office of Information Technology managed IT services for all schools on campus, so minimal support was dedicated to the dental clinics, which often require faster response times than classrooms.

Patel worked his way up to director in just three years. Since then, Patel and his team have made several impactful changes to the school: IT services were brought in-house to ensure full-time coverage during clinic hours; physical servers were moved from central IT to the dental school server room; the team expanded from two to eight full-time employees, plus four student assistants; and a ticketing system was introduced to streamline and prioritize service requests.

The IT team works on anywhere from 30 to 100 projects weekly. “My team and I get to be advocates for our colleagues. We find solutions and ways to improve, and we couldn’t do that without administrative support.”

Patel credits his past business experience for his strong work ethic and leadership mindset. “It has given me the tools to work with my team and our clients.” He previously owned a liquor store in Albany, New York, and a hotel in Indianapolis, Indiana.

“When I moved to Colorado, I was looking for a business, but it was 2008, so it wasn’t a great time.” He learned about the parttime IT job at the SDM through his wife, Pallavi Parashar, DDS (ISP ’07), BDS, who had recently graduated from CU Dental and joined the faculty. She now teaches and has a private practice in Canada.

Patel said he is the first in his family to have a job like this. “My father, grandfather and great-grandfather all owned businesses, and my cousins teased me initially for doing something different, but I enjoy what I do here. I’m always hungry to learn, so I can continue to improve, not only for myself but for my family, my team and the school too.”

Abby Jaquez, CDA, EDDA

From Alaska to Aurora, Abby Jaquez, CDA, EDDA, is grateful her career has taken her to many places. One of the most memorable was working with a pediatric dentist in Barrow, Alaska, caring for Alaska Native children. She said, “The children were adorable, and the parents were so appreciative to receive dental care for their young ones. Plus, I received my polar bear patch by jumping into the Arctic Ocean. It was frigid!”

A Coloradoan, Jaquez loves the outdoors; in the summers, you will find her hiking in the mountains around lakes or chasing waterfalls everywhere she travels. She enjoys exploring nature, teaching students and working with children.

“I always knew I wanted to work in healthcare,” she said. “I pursued dentistry and have been in the field in different aspects for 40 years.”

Twenty-six of those years have been at the University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine (CU SDM) as a dental assistant, a supervisor and a technician in radiology.

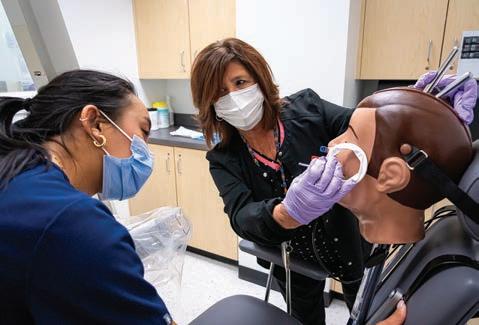

Teaching students how to take good radiographs is one of Jaquez’s proudest accomplishments at the dental school. She said, “I will see doctors I taught years ago, and they will say things like, ‘You taught me how to get a distal projection, and now I teach it to my staff.’ It is so satisfying to help students reach their career goals.”

Before the SDM, Jaquez worked in the dental clinics at Children’s Hospital Colorado for 12 years, where she developed a strong skillset working with patients who may have difficulty staying calm and still long enough to acquire a satisfactory image. Experience like this gives her a unique perspective when demonstrating helpful tactics to students.