8 minute read

Will an AI take your job?

Report

Does your computer write better than you?

Advertisement

GPT-3 is a digital service that produces text that appears to be written by a human. The service is free of charge, easy to use and available to anyone. – Technology is one of several reasons why homework has become more problematic as a basis for academic assessment in schools. But above all, these kinds of transformative technologies force us to reflect on why skills such as writing are important, says Erik Winerö, upper-secondary school teacher and doctoral student in applied IT.

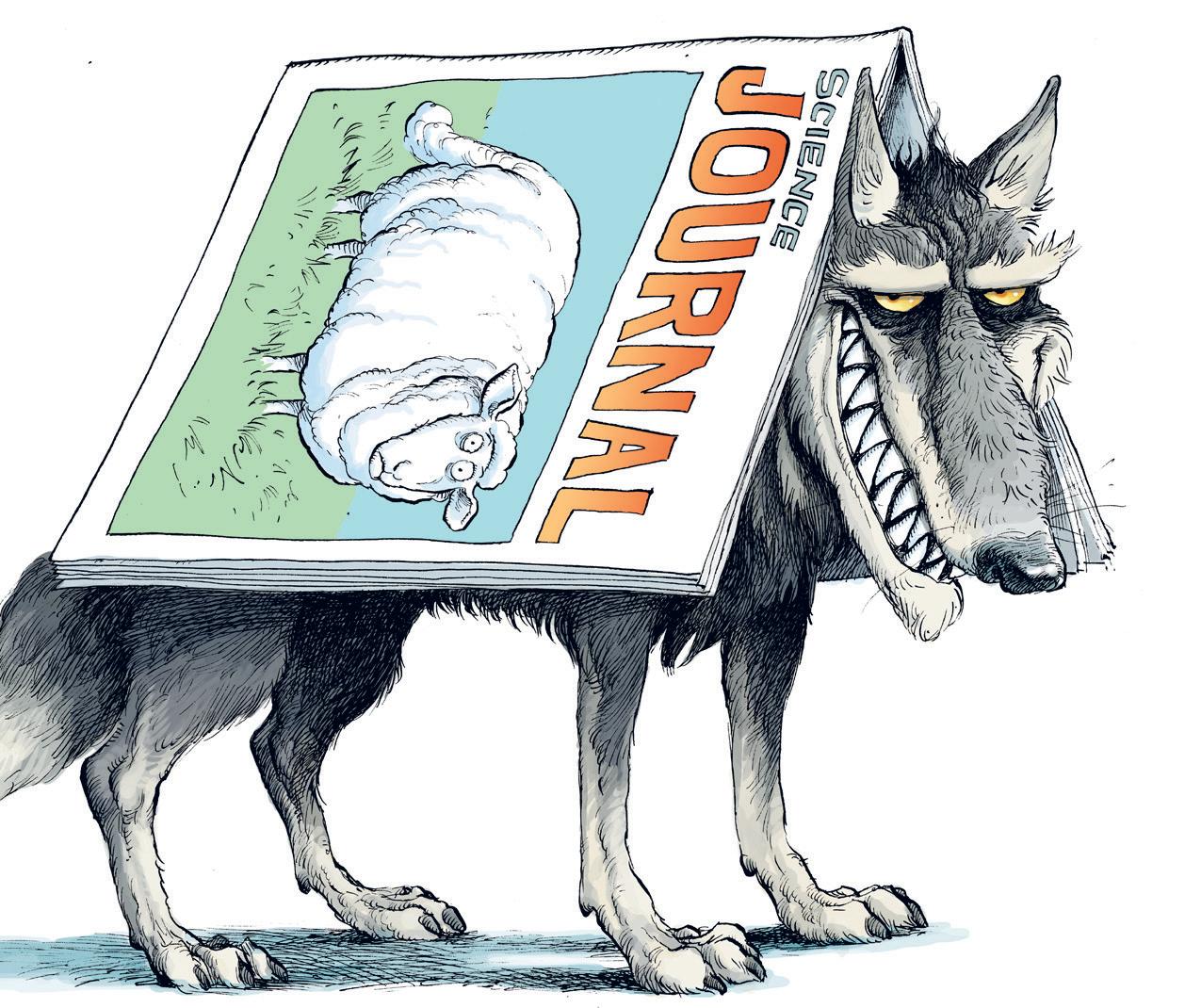

The database from which GPT-3 retrieves information is gigantic, among other things it contains all the Wikipedia pages up until 2019. There is also other material, such as published works by Tomas Tranströmer. This means, for example, that you can ask the programme to write a poem about public transport in Gothenburg in the style of Tranströmer. Not satisfied? Then be more specific and try again. The programme constantly produces new material and does not copy existing text; systems that check for plagiarism such as Original (formerly “Urkund”) are therefore of no use here, Erik Winerö tells us. – My impression is that a lot of people underestimate technology. They don’t believe that GPT-3 works very well, but when you experience it in real time, they are often quite taken aback. Furthermore, if we consider the fact that GPT-3 soon will be superseded by the next generation, GPT-4, which is estimated to be more than 500 times as powerful, we realise that we are facing a truly transformative technology. The consequences for schools are numerous. Above all, GPT-3 makes it problematic to use written assignments done as homework as a basis for examination. Of course such assignments were always problematic. Not only do they encourage cheating, but are also unfair, as pupils have such different home environments; some have access to a well-equipped home office while others share a small room with their siblings.

But GPT-3 does highlight a considerably bigger issue than the possibility of cheating: why should we continue to struggle with writing exercises when we have computer software that can produce text that is just as good as our own? One answer can be found in the work of Alexander Luria, Erik Winerö explains. – Luria was a Soviet researcher who in the 1920s and 1930s conducted experiments that are unlikely to be repeated. The basis was the massive educational initiative that was implemented in the newly formed Soviet Union where the rural population – largely illiterate – would learn to read and write. For a time, this led to there being large groups of people that were comparable in terms of living conditions, but who differed by the fact that some were literate while others were not.

What Alexander Luria investigated was the way in which a written language affected people’s way of thinking. For example, what about logical reasoning, such as: Precious metals cannot corrode. Gold is a precious metal. Can gold corrode? – Those who had learned to read had no problem giving the correct answer, while those who could not read answered based on their own experience instead: I don’t own any gold, how should I know whether gold corrodes? What Luria showed was that something happens to us when we become literate: Not only does it enable us to acquire and pass on information more easily – learning to read and

Erik Winerö says that people often underestimate digital technology.

… Learning to read and write enables us to learn

to think. ERIK WINERÖ

write enables us to learn to think.

So we must not lose sight of writing, Erik Winerö points out. – The upper-secondary school curriculum in Swedish has been increasingly focusing on different types of text and analysis of them, such as op-ed articles, abstracts and scientific memos. All of these are types of text that GPT-3 produces relatively well. One way of managing the risk of pupils using AI to generate text will be to focus more on the writing process itself. But of course it is more demanding to follow the processes of a large number of pupils rather than assessing written text using a matrix. This is an example of our having to move away from so-called “product pedagogy,” but that requires time and resources.

Another way of ensuring that pupils do not cheat is to let them write in digital test systems that lock the writing surface. This means that pupils cannot use Google or paste text from other sources. Most schools have such systems, but as a rule they are only used for final examinations. But Erik Winerö argues that they could be used in other instances as well. – It is important that a test has good validity, that it measures the right thing. If the pupils are not used to the digital systems, the validity will deteriorate. One way of improving the situation is therefore to use the systems frequently, also for assignments that are not for final examinations. Because pupils do not need more tests, they need fewer. The previous curriculum contained a paragraph about teachers, when grading, considering everything they know about the pupil; this was interpreted by many to mean that they must assess everything the pupil does. And if this is communicated to the pupils, there is a risk that they will believe that they are not allowed to fail, which is one reason why Swedish pupils are suffering from growing stress. And yet it is precisely like Yoda pointed out in Star Wars: “the greatest teacher, failure is.”

In order to reduce stress and encourage the pupils’ creativity, the teachers must be careful to distinguish between the activities that will be assessed and those that will not.

Because permissive learning environments, where pupils feel safe to fail, is crucial to a good education. An insight that is sometimes counteracted by the school system, says Erik Winerö. – Even though assessment is a crucial part of school life, up until 2011 assessment and test construction was not a mandatory part of Swedish teacher training education. One explanation could be the dominant views of knowledge, in which memory and facts are disparaged as measurements of knowledge. Interpretations of the theories of, for example, Piaget, Vygotsky and Dewey may lead to the notion that it is only when you do something practical that knowledge becomes visible. With that mindset, classic tests become less relevant. Furthermore, sometimes you come across the view that since we can google for facts, we do not need to remember them to the same extent as we used to. The problem is that that is not the way our brain operates. For example, in order to be able to think critically, we need access to information in our long-term memory. A mobile phone cannot replace that.

So, should digital programmes, such as GPT-3, be completely banned? No, Erik Winerö argues.

– A computer generated text can constitute an interesting starting point for discussions, such as about why a text is good or bad, and about what the text might have been like had I written it myself. Also, GPT-3 can be quite fun, and might inspire people to write themselves.

Naturally, digital technology will have an impact on much more in our future society than the ability to produce text, Erik Winerö points out. – Digital technology will replace almost all of the labour that most of us make a living from now. As, we to a great extent today identify ourselves with our work, that future perspective may appear frightening. But having a particular profession is something that is a fairly recent phenomenon. We can spend our time on other things, such as trying to become good democratic citizens. We can also spend time on artistic endeavours and perhaps take pleasure in the enjoyment and self-realisation that writing can provide – regardless of how many good digital programmes are being developed.

Text: Eva Lundgren Photo: Johan Wingborg

Examples

By entering: “Write a poem in the style of Tranströmer about AI-based text, cheating and Swedish schools” GPT-3 produced the following text: When we’re cheating in our writing we take the shorter path when we make our way

It is easier and takes less time and we don’t need thinking

but it is never truthful cause we’re lying

And cheating will forever remain in place

As a shadow on our learning

A memory of the shortcut that we once took

When we cheated in our writing.

The Moment

Where? Who, When?

•The amphitheatre at Humanisten. • Agnes Eriksson and Philip Ahlgren. • Saturday June 18.

In short

One afternoon in mid-June, Humanisten was transformed into something very special: the open light amphitheatre became a wedding venue for Agnes Eriksson and Philip Ahlgren. – We both work in the construction industry and are interested in architecture and therefore wanted to get married in a venue that is special in some way. We searched for a long time before we eventually got tips about the Humanisten. And the amphitheater is really beautiful with its large, open staircase! The acoustics are good, the woodwork contains fine details and the artist Meriç Algün, who is responsible for the decoration, has used recycled materials. It is simply a room for joy.

Neither Agnes nor Philip have been students at Humanisten or have any other connection to the building. – No, we chose the venue only because it is so beautiful. After the ceremony, we had a reception in Villa Johanneberg right next to Näckrosdammen, which of course was also practical. The number of guests at the wedding was just over 50, the officiant was Marianne Carlström and the wedding trip went to Portugal, the French Riviera and Corsica.

Foto: JOHAN WINGBORG