5 minute read

Our century: Past and future thinking at the IHR

By Professor Jo Fox and Dr Philip Carter

The Institute of Historical Research (IHR) is the UK’s national centre for history, and is one of the institutes that comprise the University’s School of Advanced Study. Founded in 1921, the IHR is currently preparing to mark the centenary of its creation. Summer 2021 sees the launch of ‘Our Century’ — a 12-month festival of activities that explores history’s past, present and future, and the IHR’s central role in shaping the discipline in the 2020s and beyond.

On 8 July 1921, the great and good gathered at the University of London’s new home in Bloomsbury. The invited party, including politicians, church leaders, diplomats and senior academics, were there to celebrate the opening of the University’s new Institute of Historical Research. Guest of honour was Herbert Fisher, president of the Board of Education, whose address was subsequently reported in The Times newspaper. The Institute’s creation was, he declared: “a notable stage in the development of historical studies.” Its students would be “trained in methods of historical research,” with the University of London set to become “a centre of historical training and education, richer in opportunities than Paris or Berlin.” Fisher concluded by praising Albert Pollard, the Institute’s inspiration and founding director, whose “signal energy and zeal” had made possible this new home for history.

A pressing need

Fisher was quite right. For more than a decade, Pollard had been planning and arguing for a national centre of historical research. The need was pressing. History as a scholarly discipline was then in its infancy and still regarded by many as a mere branch of literature. In contrast, those campaigning for a new approach to the past advocated rigorous archival-based study, ‘scientific’ research methods and qualifications such as the PhD – first awarded in History by a British university in 1921. By the late 1910s, Pollard and others feared Britain was lagging far behind in this race for a modern research culture – a rivalry which accounts for Fisher’s competitive reference to Paris and Berlin in his speech.

The race was also speeding up, hastened by profound changes that followed the end of the First World War. In Britain suffrage reform had greatly increased the number of working-class men and women aged over 30 now able to vote. Meanwhile, from across Europe came calls for greater international collaboration to avoid returning to the horrors of modern warfare. To its champions, History and historical knowledge were essential tools in cultivating both a responsible mass electorate and a new spirit of internationalism. In an essay from 1920, Pollard spoke of his proposed ‘School of Historical Research’ as having a “practical bearing upon our present problems and our present discontents.” The world was in flux and the coming decade full of uncertainty. “It is useless simply to know things as they are; we want to know what they will be, and we have no way of guessing… unless we know what they were.” For Pollard, history was “the dossier of mankind,” and his Institute was where future editions should be compiled.

100 years

Now, 100 years after this call, the IHR’s current staff are preparing to mark the centenary of its creation. Beginning on 8 July 2021, the Institute will host ‘Our Century’, a 12-month festival of history which revisits, and updates for the 2020s, Pollard’s views on the value of historical thinking and research.

Much, of course, has changed since 1921. The archival research culture that Pollard sought is now central to academic history. So too the infrastructure of libraries, seminars and peer-reviewed publishing that the IHR has done much to promote over the past century, and in which it continues to innovate. The scope of current historical research likewise far exceeds that undertaken by previous generations. Histories of women, gender, working people, minority groups, ethnicity, identity, global exchange or the environment are just some of the research initiatives that have reshaped, and continue to broaden, the discipline. Technological change meanwhile brings innovative ways of analysing and quantifying the past, along with powerful new forms of communication. Over its first 100 years, the Institute of Historical Research has played a leading role in these developments: both as a centre for digital, community and regional history, and as the national meeting place where historians come together to think and collaborate.

And now

And yet, despite these changes, it’s also striking just how relevant Pollard’s founding vision remains for those now preparing the Institute’s centenary year. Today we too face a range of “present problems and discontents” – from populism and social exclusion, to national rivalries and the unknown legacies of a pandemic – that uncannily echo those of 1921. What is history’s place in and contribution to their resolution?

By taking ‘Our Century’ as our theme we’ll engage directly with this question. The IHR centenary is certainly a chance to look back: to reflect on history’s development as a discipline since the 1920s. But more importantly it’s an opportunity – in the spirit of the Institute’s founders – to explore new ways of thinking that will shape research in the 2020s and beyond; and to consider how historical understanding can help us face, and fashion, our coming century. This work will engage the wider community, including archivists, curators, public historians and broadcasters, who make up today’s rich historical culture. As a national and international programme of events, ‘Our Century’ will show how historical research is no longer the preserve of universities; and encourage us to recover the many hidden and marginalised histories yet to be told.

A unique experiment

Twelve months after the Bloomsbury celebrations of July 1921, Albert Pollard sat down to write the Institute’s first annual review. It had, he thought, been a productive year. Hundreds of historians and students were now visiting the IHR from British and overseas universities; weekly seminars provided insights on new research methods; Institute staff were advising government on matters of foreign policy; and as a “laboratory of historical research” the IHR was serving not just academics “but the community as a whole.” Seldom given to gush, Pollard did allow himself one moment of congratulation at the end of his report. The IHR, he concluded: “is a unique experiment. There has been nothing quite like it.” There hadn’t and, a century on, there isn’t – as we aim to show from July 2021.

Professor Jo Fox is Director of the Institute of Historical Research.

Dr Philip Carter is Director of Digital and Publishing at the Institute of Historical Research.

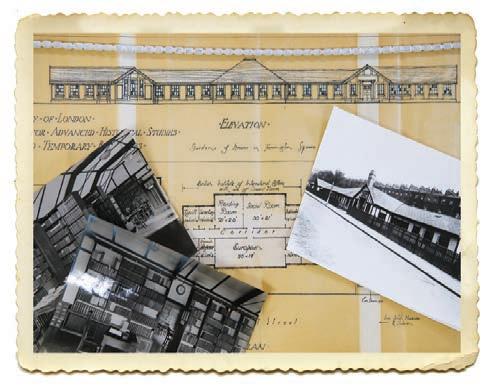

Below: the first home of the Institute of Historical Research from 1921. This temporary ‘hut’ as it was known, located on Malet Street, was the site of the IHR until its move to Senate House in 1938.