11 minute read

Laying the Foundation USF HISTORY PART 1

By 1920, when the University of St. Francis began, the legacy of the Franciscan Sisters’ commitment to Catholic education and progressing their community was already deeply embedded in Joliet. They created and supported multiple institutions that complemented the development of the region, and without their strength and vision, the University of St. Francis would not exist today. The story of their path, and the values they imparted, provides insight into the character and values of a now 100-year-old institution of higher learning, often referred to as “Joliet’s University.”

The story begins in 1851 when a spirited young woman named Maria Catherine emigrated from Remich, Luxembourg to the United States with her sister, Catherine. The youngest daughter of a prosperous ironsmith, Maria was well-educated. She and her sister had attended boarding school, studying French and German, mathematics and architecture, and such skills as sewing and painting— significant accomplishments at the time.

Hoping to teach Native Americans, they traveled first to Milwaukee—a bustling but “plague-ridden” town like most frontier settlements, and desperately in need of schools, orphanages, and hospitals—before moving to South Bend, Indiana. There, the two sisters taught in parochial schools for the next seven years, eventually taking religious vows and receiving new names: Maria became Sister

Laying the Foundation

THE JOLIET FRANCISCANS PAVE THE WAY FOR “JOLIET’S UNIVERSITY”

by David Veenstra, USF Associate Professor of History

Alfred Moes and Catherine became Sister Barbara Moes. Seemingly looking for greater autonomy, they chose not to join the Indiana order, and instead pursued and joined the Third Order of St. Francis of Allegany, New York.

The Sisters’ reputation for good teaching spread and they were asked to staff a new school in Joliet, Illinois. Founded in 1837, Joliet had been settled by laborers building the Illinois & Michigan Canal. Workers continued to pour into the region, lured by jobs in the limestone quarries and the steel mills—industries that earned Joliet the nicknames “Stone City” and “City of Steel.” The immigrants initially needed help navigating American society. As they established stable homes, their children needed teachers.

On November 2, 1863, Sister Alfred Moes and a companion arrived in Joliet to teach at St. John the Baptist school. A few students from Indiana followed them and Sister Barbara Moes came two years later. This small group became the “first community of religious teachers in Joliet and Will County and the first Franciscan Sisterhood in Illinois.” In 1865, they were formally established as the Third Order of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate. Sister Alfred Moes was named their superior, becoming “Mother” Alfred Moes.

Both the congregation and the number of students grew exponentially. Three times over the next few years, the Sisters enlarged their convent, which began as a small stone cottage near the corner of Broadway and Division streets. In 1869, they began teaching in-house, both as a boarding and day school. They also cared for orphans. Initially calling the school “St. Francis Select School for Girls,” the Sisters eventually chartered it with the state of Illinois and named it “St. Francis Academy.” This beginning to the Sisters’ educational impact in Joliet established important precedents for providing access for young women to quality education.

Life at the academy and convent was hectic. Everyone lived together under the same roof: Sisters, novices, postulants, boarding students and orphans. Girls aged 3–20 from across the country took courses in English and French as well as science, mathematics and business. Sisters learned to teach by apprenticing as part of their “Normal Institute,” with many going on to establish schools of their own. Everyone pitched in with gardening, cleaning, and fetching groceries. To make ends meet, they also started a small enterprise making artificial flower arrangements for special occasions around the city. The work was accompanied by cultural broadening. Mother Alfred Moes bought a used piano and gave lessons to the students. The academy also offered classes in advanced painting and embroidery, hosted neighborhood plays, and brought in guest speakers—fostering an environment similar in many ways to that of Hull House, which was founded in Chicago several decades later.

The enterprise quickly outgrew the walls of the convent and academy. Rather than expand from their location, which was located just a block from the I&M Canal and often smelled of waste from Chicago, the Sisters made plans for a new building at the site where Nowell Park is presently located. Their blueprints were impressive: plans called for constructing a three-story, E-shaped building, complete with a gymnasium, bowling alley, and even a museum.

Mother Alfred Moes “craved action,” as one biographer noted. She also seemed determined to enlarge Catholic women’s roles in the emerging American society. This attitude served her well initially, and she received a broad license for ministry and making improvements.

But in 1870, Bishop Thomas Foley of Chicago took charge of regional matters. He worked tirelessly in the aftermath of the Chicago Fire to rebuild the church in the city. Having been trained in the city on the East Coast, however, he understood little of frontier life and failed to appreciate the entrepreneurial leadership practiced by Mother Alfred Moes. Thus, when presented with the congregation’s plans to expand the convent and school, he turned them down.

Bishop Foley then insisted that the order elect a new superior. Precisely what caused the clash is unclear, but plainly the two held different visions of what was best for both the congregation and for Joliet. Soon thereafter, the congregation fielded a request to open a new school in Rochester, Minnesota. Mother Alfred Moes agreed to lead the project—an endeavor that led to her co-founding St. Marys Hospital, now part of the world-famous Mayo Clinic. Bishop Foley then formally separated her from the Joliet congregation, and gave the Sisters ten days to choose a side. Ninety-two Sisters continued as Joliet Franciscans while 25 went to Minnesota.

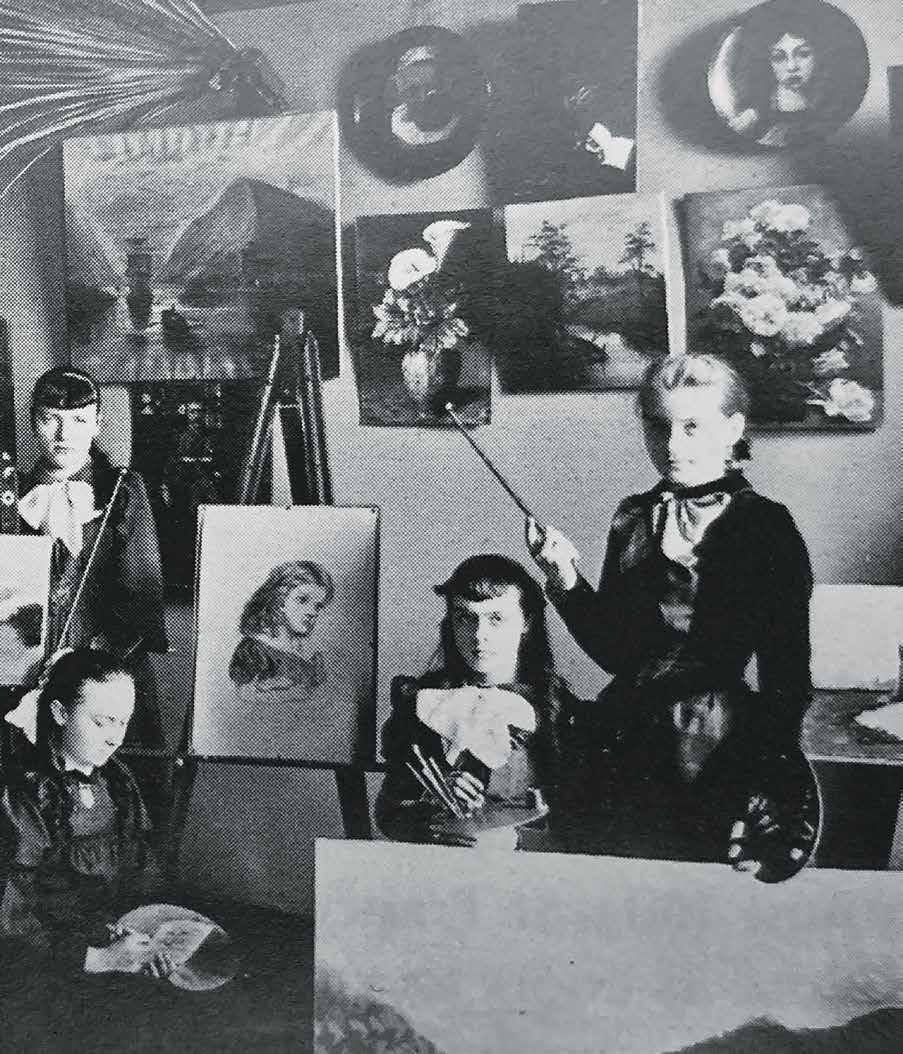

A full St. Francis Academy classroom, 1892.

The motherhouse as it used to be in the school’s early days.

Mother Alfred Moes, founder of the Third Order of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate.

Minim Class (younger students) at St. Francis Academy during its last full academic year before closing to external students, 1904.

During the next few decades, Joliet experienced rapid population and economic growth. Alongside these came difficulties. Typhoid fever hit in 1881, and smallpox in 1882. Newspapers often reported that hospitals crowded beyond capacity were combating pneumonia, whooping cough and other diseases. Harvests failed and food shortages were reported regularly.

The Sisters persisted and grew their work amidst these hardships. In 1880, they purchased property bounded by Taylor and Wilcox streets, partnering with Joliet businesses—pledging that an educational institution and new motherhouse would be built. Construction began the following year, with the congregation taking up residence in 1882. With part of the building dedicated to instruction, this move to the current motherhouse laid the foundations for the modern University of St. Francis.

The old convent was sold to the Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Heart and they quickly converted it into a functional hospital, complete with 20 beds (the humble beginnings of Saint Joseph Medical Center, now owned by AMITA Health). The Joliet Franciscans also purchased a small cottage behind the motherhouse in 1896 to provide complete care for orphans—particularly very young children.

Within a year, the number of children under the Sisters’ care increased to 19, so they purchased an estate on Buell Avenue, which they named Guardian Angel Home. Later, in 1925, the Sisters expanded even further, building new Guardian Angel Home facilities where USF’s St. Clare Campus is now located.

Midwest. The big boon, however, came with the publicity they received after taking out a booth at the Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1893, with the students winning the highest award.

Mother Thomasine Frye, OSF, first president of Assisi Junior College.

By the turn of the century, Joliet was maturing, growing from limestone quarrying and steel production to manufacturing of all sorts. Brick factories, foundries, machine companies and breweries quickly sprung up. Enrollment at the academy also expanded, stretching beyond the limits of the buildings and the faculty, forcing the Sisters to temporarily close the doors to external pupils. To fill this void, alumnae of the academy, the City of Joliet and various friends helped fund the construction of a new academic wing to the motherhouse—now known as Donovan Hall. In 1915, the congregation celebrated its 50th anniversary with the reopening of St. Francis Academy, which continued in the motherhouse until the Sisters built a new school on Larkin Avenue in 1956. (SFA later merged with the all-male Joliet Catholic High School in 1990, becoming Joliet Catholic Academy.)

Joliet’s development meant increasing opportunities for young women with access to advanced education to realize these opportunities. This need, along with the academy’s continued success, caused the Sisters to consider opening a college. Catholic women’s colleges were beginning to debut throughout the United States, but unlike most other Catholic women’s colleges that launched under the patronage of a men’s institution, the Sisters would be on their own. Equally important, Joliet Junior College—the first junior college in the nation—had recently opened on the other side of town and promised to provide competition.

Undeterred, in 1920, the Sisters amended the academy’s original charter to offer college courses, responding to—in their words—the “urgent appeals of their friends and to a demand for a Catholic institution for young women of Joliet and vicinity.” Classes began that fall at what was simply called the “New College.” Mother Vincent Hunk, a protégé and close friend of Mother Alfred Moes, oversaw the inauguration of the college. They initially provided instruction for the congregation and the Sisters of St. Francis of the Sacred Heart, along with nursing students at St. Joseph School of Nursing, which also opened in 1920. But it was Mother Thomasine Frye—an educator who had been instrumental in staffing Illinois schools with teachers— who insisted on the academic diversity and excellence that would sustain the college’s growth.

In early archive photos from the 1920s, the Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate provided nursing instruction for their congregation, the Sisters of St. Francis of the Sacred Heart, and St. Joseph School of Nursing students.

Assisi Junior College students pose on the steps of the wing of the motherhouse now called Donovan Hall.

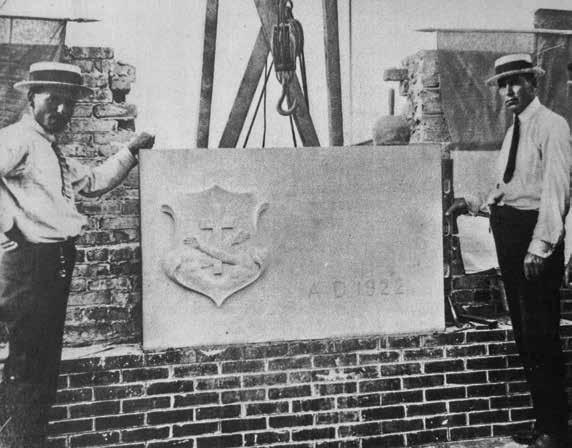

Laying the cornerstone of Tower Hall, 1922.

Vetting their academic plans with other institutions, the Sisters chose to begin as a junior college before becoming a four-year institution. They initially planned to name the school Illini College, but after discussions with the Cardinal of Chicago and University of Illinois, they decided on Assisi Junior College.

In 1922, the Sisters began construction of Tower Hall at the corner of Wilcox and Taylor Streets to provide space for the academy and student dorms, and to free up space in the motherhouse for college coursework. In 1925, Assisi Junior College opened to the public, and shortly thereafter, Mother Thomasine Frye became the college’s first president.

Thirteen students from both the congregation and community enrolled in classes at Assisi Junior College in its first year. At the end of the term, the state of Illinois gave the college approval to issue teaching certificates—an early step toward accreditation, which was granted a few years later. Over the next five years, enrollment increased to 92. All the faculty were Sisters, except for one layperson hired to teach physical education for all freshmen. Courses were taught in dedicated classrooms—English in one room, sciences in another, and so forth. Uniforms, consisting of a “simple one-piece dress of black flat crepe, and white collars and cuffs of the same materials,” were mandated. For chapel, students donned a black beret.

Most students lived on campus in dorm rooms located in Tower Hall. They interacted regularly with the community: entertaining orphans at Guardian Angel Home, holding plays at the elementary school, and collecting books and magazines for distribution to the inmates at the local prison. The Assisi Prom, also known as “Ye Collegiate Hoppe,” was held in the spring at the Joliet Country Club. During the 1927-1928 academic year, a basketball team was organized and played several intramural games against local teams, as well as two intercollegiate contests against DePaul in Chicago. Other sports offerings included tennis, volleyball and croquet.

In 1930, the curriculum grew to a four-year format. With that, the Sisters formally established the College of St. Francis, which received bachelor’s degree-granting authority as a class “A” institution. Under Mother Thomasine Frye’s guidance, the college began offering majors in liberal arts, English, teachers’ training, business, science and journalism— offering curricula that prepared students for careers and admission to graduate programs. The faculty, too, became increasingly specialized—pursuing advanced degrees, publishing academic work, and participating in academic conferences.

Mother Thomasine Frye continued to serve as the college president until 1938, when the college received accreditation recognition from the North Central Association of Colleges and Universities (later becoming the Higher Learning Commission). At the conclusion of her tenure, she said with satisfaction and hope that this time marked the “end of the beginning” of the College of St. Francis. She was right. The small enterprise, which began with a day school and orphanage, had grown and adapted to the needs of the people of Joliet, through the congregation of the Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate, St. Francis Academy, and by 1930, the College of St. Francis.

The University of St. Francis story will continue being told in all three issues of Engaging Mind & Spirit in the centennial year. We look forward to continuing to share our rich history with you!