26 minute read

The Green

YOU SHOULD KNOW

So a warm welcome to the xenobots, hybrid robot-organisms like no other. May the world treat you kindly.” —Wired Wired was among hundreds of media outlets worldwide that recently covered ground-breaking research by UVM professor of computer science Joshua Bongard and colleagues at Tufts University. Read more on page 18. “

Advertisement

English professor Emily Bernard’s collection of essays Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine has garnered wide praise, including earning a place among author and critic Maureen Corrigan’s top ten “unputdownable reads” of 2019. 10 TOP

0%

The percentage University of Vermont tuition will increase from fall 2019 to fall 2020. Read more on page 7. For the third consecutive year, UVM’S Grossman School of Business Sustainable Innovation MBA has been named the no. 1 “best Green MBA” program by The Princeton Review. GREEN GREATNESS

PROFS OF INFLUENCE William Copeland, professor of psychiatry, Mary Cushman, professor of medicine and of pathology and laboratory medicine, and Taylor Ricketts, director of UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment, all earned a place on the 2019 list of the world’s most influential researchers. The Clarivate Analytics Highly Cited Researchers list is based on the number of times published studies have been cited by other researchers over the past decade.

During the fall semester, Catamount student-athletes combined to achieve a school-record GPA of 3.297, marking the thirty-third consecutive semester the department GPA has been above 3.0. Read more: go.uvm.edu/gpa WINNING STREAK

SOUTH POLE SCIENCE As one of twenty-four members of the National Science Board appointed by the President of the United States, UVM President Suresh Garimella spent a week in December touring Antarctica and inspecting facilities run by the U.S. National Science Foundation on the coast of the continent and at the South Pole itself. “Now it’s critical—existentially critical—to understand Antarctica,” Garimella says. “Understanding how—and how fast—the glaciers and ice sheets are moving, melting, and growing in this remote part of the planet is of great consequence for all of us.” Read more: go.uvm.edu/pole

THE GREEN News & Views

FIELD TRIP: A visit to Patrick Gym is a favorite excursion for kids at the UVM Campus Children’s School. Life-size posters of Catamount basketball players Hanna Crymble and Daniel Giddens are a particular attraction these days. Eleanora Boyd, Charlie Corran, Wren Farran, and Ben Strotmeyer check how they measure up.

New Leadership Team

TRUSTEES | In June 2019, Ron Lumbra ’83 testified before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services. His subject: presenting strategies to enhance the diversity in the nation’s board rooms, comments informed by Lumbra’s two decades in the executive search industry, where he is a managing partner of the firm Heidrick & Struggles. And it’s a circumstance Lumbra, who became the third African-American board chair in UVM history with his election in early March, has experience with in his own life and career.

Raised in northern Vermont’s Montgomery Center, Lumbra’s adoptive parents had not attended college themselves, but encouraged him as he excelled in both academics and athletics. Looking back on his UVM years, Lumbra says, “The exposure to out-of-state kids—new friends from Cleveland, Seattle, Syracuse, Silver Springs, Philadelphia—for a kid from small-town Vermont, it was the best possible thing I could have had. It flipped my script, that access to different ways of thinking from students with more urban backgrounds.” A mechanical engineering major at UVM, Lumbra continued his education with a Harvard MBA. Today, from the perspective of board chair, Lumbra celebrates how providing opportunities for first-generation students syncs perfectly with the mission of a land grant university.

Cynthia Barnhart ’81, the board’s new vice chair, shared the campus (and Votey Hall) with Lumbra in the early eighties as she earned her bachelor’s in civil engineering. Barnhart’s parents also did not attend college, but they saw that Board of Trustees Vice Chair Cynthia Barnhart ’81, Chair Ron Lumbra ’83, Provost Patricia Prelock, and President Suresh Garimella. all of the kids in their Barre, Vermont family—Cynthia, her sister Kathy ’80, and brother Richard ’82—earned their degrees from the state university. “My parents valued education a lot,” she says. “UVM was a great launching pad for all three of us.” Barnhart’s husband, Mark Baribeau ’81, is also in the Catamount family.

As a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the past twenty-eight years, Barnhart has blazed trails, becoming the first woman to fill the role of chancellor with her appointment in 2014. She brings deep higher education experience to the UVM board, particularly on student issues, the focus of the chancellor’s role at MIT.

As Barnhart and Lumbra join forces in board leadership, President Suresh Garimella has quickly built a strong working relationship with Provost Patricia Prelock as they head the university’s administrative team. A UVM faculty veteran who has served the university as professor and chair of communications sciences, dean of the College of Nursing and Health Sciences, and now as provost, Prelock brings a wealth of institutional knowledge and history to her leadership role. An internationally recognized expert on autism, Prelock has also worked closely with Vermont children with autism and their families for years.

“This team has a diverse and powerful range of knowledge and life experience united by a deep commitment to the university and its land grant mission,” says President Garimella. “I’m excited about what we’ll achieve moving forward—as a leadership group, and together with the UVM community.”

Holding the Line on Tuition

CAMPUS LIFE | As part of his commitment to making UVM accessible and affordable, President Suresh Garimella announced in November that tuition for the academic year beginning in fall 2020 would not increase over 2019 levels.

“Student loan debt is the second highest category of consumer debt—second only to mortgage debt and higher than credit card debt. Funding a college education is one of the very largest expenditures families face in the United States,” Garimella said. “Forty-four million borrowers owe $1.6 trillion in student loan debt. Yet, education is increasingly important to future success. It’s critical that we do everything we can to address the pressures that families and individuals face in their effort to achieve their educational goals.”

Garimella said the university has kept tuition increases at modest levels in recent years and commits over $160 million in grants, scholarships and tuition remission every year, enabling 44 percent of Vermonters to attend UVM tuition-free.

The university has seen a steady rise in its four-year graduation rate, which now ranks in the top six percent of public universities nationally. Garimella said the university will work hard to further increase its already enviable graduation rate as another cost-cutting strategy for students and their families. Timely graduation decreases the overall cost of a degree and enables students to join the work force earlier.

“Despite that solid record,” he said, “we need to do even more.”

The zero tuition increase, contingent on UVM Board of Trustees approval this spring, is part of Garimella’s efforts to enhance the value of a UVM education. Half of the value equation is educational quality, he said, an area the university

has devoted thought and resources to in recent years, creating new courses, expanding experiential learning opportunities, investing in student advising and career counseling, and continuing to recruit top teacher-scholars, trends that will accelerate during his presidency.

Cost is the other half of the value ratio, an area the 2020 zero percent increase addresses. “Relying on annual tuition increases, even modest ones, is not sustainable,” Garimella said. “As we move forward, we will focus intently on all the ways the university can generate additional revenue to relieve the pressure on tuition.”

| THE GREEN

Artist and Citizen

ART | Mildred Beltré’s neighborhood in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, has it all: the sprawling greenery of Prospect Park, world-class art and events at the Brooklyn Museum, beautiful brownstones around every corner, and nearly any cuisine one could crave—all within walking distance. But after twenty years in her apartment, the native New Yorker and UVM professor of drawing and printmaking says the rest of the borough has finally caught on. Gentrification is rapidly transforming Crown Heights.

For longtime residents like Beltré and Oasa DuVerney, a fellow teaching artist in Beltre’s building, the influx of people and renovations that come with gentrification create a revolving door of fleeting neighbors and businesses, a vulnerability to rent inflation and landlord corruption; increased policing; and a sense of mistrust and suspicion. But the duo isn’t letting their block on Lincoln Place get swallowed up by Brooklyn’s growing hipster scene so easily.

Nearly ten years ago, the two artists took their art supplies, pop-up tents, tables, and chairs out to the sidewalk in front of their building. Together, they hoped to attract curious passersby and befriend their neighbors while they made art. Since then, the “Unofficial Official Artists in Residence” of Lincoln Place have evolved the experiment into Brooklyn Hi-Art! Machine, a collaborative public art project that builds gentrification resilience and community on their block through art.

Beltre and her neighbor have taught mediums like weaving, dance, sculpture, drawing, and silk screening to their community; they’ve planted gardens and invited guest artists to create site-specific installations on their block; and have hosted barbecues and tenants’ rights meetings through BHAM. Beltré, DuVerney, and BHAM’s work was recently displayed by the Brooklyn Museum, has appeared in the Brooklyn Children’s Art Museum, and has been awarded a Brooklyn Community Foundation grant to support neighborhood strength.

LEAHY SCHOLARS INITIATIVE

LEAHY UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARS Tuition support and funding for learning opportunities for Honors College students

LEAHY DOCTORAL & POSTDOCTORAL SCHOLARS Support for students involved with the Gund Institute for Environment

Support the Leahy Scholars: go.uvm.edu/leahy

Leahy Scholars Initiative Honors Senator’s Decades of Support

FOUNDATION | In recognition of Senator Patrick Leahy’s decades of support for important research and teaching initiatives, the university has announced a new $3.3 million fund that will pay tribute to Senator Leahy and his wife, Marcelle. Funds for the Patrick and Marcelle Leahy Scholars Initiative were raised, and will continue to grow, through private philanthropy. The new fund will benefit undergraduate, doctoral and post-doctoral students in two signature programs at the university: the Honors College and the Gund Institute for Environment.

“The Leahy Scholars Initiative will provide financial support and enrichment opportunities that will help us prepare students to meet the challenges that confront our state, our nation, and our world,” said Suresh Garimella, UVM president, when the fund was announced in October. “This is a tremendously impactful way to honor Senator Leahy and the societal impact he himself has had over the last half century.” “We are so proud of Vermont’s land grant university, and this ongoing investment in the future of UVM and its students honors its rich legacy,” said Senator Leahy. “To be a part of UVM’s future means so much to us, and to Vermont. We love the idea of being a part of training the next generation of climate scientists. We are inspired by the vision and determination of our students and can think of nothing better than investing in these emerging leaders.”

The Leahy Undergraduate Scholars program will support students selected from the Honors College, whose members represent the top 10 percent of undergraduates admitted to the university, spanning all its colleges and schools. The students, chosen competitively based on their academic record and engagement in community and other causes, will receive both tuition support and funding for high-impact learning opportunities, including study abroad, research, internships, and community service.

The Leahy Doctoral and Postdoctoral Scholars program will support students engaged in activities supported by the Gund Institute for Environment, a community of 150 researchers and leaders from across UVM’s colleges and departments. The Gund Institute is also allied with forty partner institutions in ten countries.

Selected doctoral and post-doctoral students will receive funding for customized leadership training and real-world experience collaborating with leaders in government and business, with the goal of promoting a deep understanding of complex global environmental issues. Leahy Doctoral and Postdoctoral Scholars will conduct cross-disciplinary research on global environmental challenges with worldclass mentors at UVM.

| THE GREEN

Cynthia Reyew

Water, Water Everywhere

ENGINEERING | “Think about it,” says engineering professor Appala Raju Badireddy, “seventy percent of the planet is covered with water—and we’re running out of drinking water.” He’s leading a research effort to help solve that problem. As the director of UVM’s Water Treatment and Environmental Nanotechnology Laboratory, he and his students are designing and creating a new generation of filtering membranes to make clean water—quickly and cheaply.

A membrane is, in some ways, simple: it’s a barrier with holes. If the holes—the pores—are of a certain size they’ll keep out bulk items, like grains of sand. If they’re smaller, they can keep out microscopic threats, like parasites. Smaller still, viruses. And, below the nanoscale, molecular filtration membranes can separate out dissolved substances, like toxic chemicals or the salt in seawater.

“It’s a nearly perfect technology,” says Badireddy. “You can capture pathogens. Without adding any chemicals, you can make seawater, or even sewage, drinkable.” Indeed, in Singapore about a third of the drinking water supply comes from membrane-filtered sewage. And many other places in the world from Florida to California, Saudi Arabia to India, have major investments in desalination plants that use membranes to extract drinking water from the ocean. Except that membranes have one central flaw. “They clog,” says Badireddy. “Everything clogs the pores.”

But what would happen if you put an electrical field really close to a membrane surface—or ran current through the membrane itself—and polarized it? Badireddy asked himself that question and discovered a powerful, low-cost repellant to keep membranes clear of a host of materials that can clog them.

“Everything in the water is charged,” Badireddy explains, “it’s all negatively charged or positively charged.” Using an alternating field, that flips its charges very frequently, attracts both positive and negative particles. This oscillation—pushing bits of waste or bacteria back and forth— keeps them in suspension while the water passes through the membrane. “And then the contaminants get carried away during the crossflow,” Badireddy says, a bit like leaves that wash over and past a storm drain while the rainwater pours down.

As Badireddy’s lab continues to follow the path of this research, it could mean a revolutionary advance in membrane design with worldwide application. His work is also focused on a critical local application—addressing phosphorus, a key nutrient for agricultural plants but also a persistent pollutant that contributes to eutrophication and toxic algae blooms in lakes and streams.

Badireddy wants to use membrane filtration to capture phosphorus in the water—and return it to the farm before it reaches Lake Champlain. Describing the potential benefit of the approach—for farmers, wastewater treatment facilities, and the health of Vermont’s Great Lake— Badireddy says, “It’s resource recovery. The difference between pollution and a resource is often just where something is located.”

SECRETS UNDER THE ICE

GEOLOGY | The real mission was to build a top-secret missile base. But, in the early 1960s, the U.S. Army publicly trumpeted the creation of a scientific station called Camp Century—a “city under the ice” they called it, in northwestern Greenland, far north of the Arctic Circle. A series of twenty-one horizontal tunnels spidering through the snow—complete with movie theater, portable nuclear reactor, nearly two hundred residents, hot showers, a chapel, and chemistry labs—all, they said, in aid of research.

As part of the effort, a team led by U.S. glacier scientist Chester Langway drilled a 4,560-foot-deep vertical core down through the ice. Each section of ice that came up was packaged and stored, frozen. When the drill finally hit dirt, the scientists worked it down for twelve more feet through mud and rock. Then they stopped.

For decades, this bottom-most layer of ice and rock from the core was lost in the bottom of a freezer in Denmark. Last year, it was rediscovered—in some cookie jars. In October, more than thirty scientists from around the world gathered at UVM for four days to decide what this one-of-a-kind sample of silty ice and frozen sediment might tell us—and how best to study it.

UVM geologist Paul Bierman, who led the workshop, thinks it may be “the key, the Rosetta Stone,” he said, to understanding how durable the ice on Greenland was during past warmings and coolings. And this, in turn, can give scientists a much clearer sense of how fast Greenland might melt in the warming world of the future. Since some twenty feet of sea-level rise is bound up in that vast ice sheet, the answer to this question is of dramatic global consequence. The preliminary results that Bierman and two scientists in his lab—Drew Christ and Lee Corbett—presented at the workshop are troubling. “We should be hoping that this dirt has been covered for two or three million years or more,” he said. Instead, the team’s analysis of the sediment, with support from the National Science Foundation, suggests the massive ice sheet over Greenland must have been greatly reduced within the past million years or less—during a warm time when the Earth’s climate was similar to today.

“This is tentative. We did most of this work in just the last few days, going like mad to be ready for the workshop,” Bierman said, “but, if this first look holds true, this is big-time bad news.” A Greenland that melted off recently, when the past was like today, is a Greenland that is likely to quickly melt again. Discussion among the international team of scientists gathered at UVM this fall will expand the ways this rare sample of geologic history can sharpen our vision of the future.

An overlooked bit of Greenland dirt collected in the 1960s is a treasure for scientists with modern techniques for dating the last exposure of sediment. Working in UVM’s Community Cosmogenic Facility in Delehanty Hall, geology professor Paul Bierman is an expert at analyzing tiny amounts of radioactive isotopes to gauge how long it has been since a landscape was not covered with ice.

| THE GREEN

Hoop Dreams, Wisely Considered

DRAFTED GRADUATE 120% current NBA rookie salary

DRAFTED FRESHMAN 60% current NBA rookie salary

New salary structure proposal by UVM finance professor Michael J. Tomas III and UVM accounting professor Barbara Arel.

BUSINESS | Going pro early may be a nobrainer for college superstars like former Duke freshman and 2019 NBA draft firstpick Zion Williamson. But an article in the International Journal of Sport Finance by two professors in the Grossman School of Business proposes a new salary structure that might entice most other college players considering the NBA to graduate before trying their hands at going pro.

“Zion Williamson is a classic example of a strangely strong signal that foregoing the remaining time in college is rational—from a basketball perspective, we’re not talking about his education or degrees—but from a basketball learning perspective, he had nothing more to gain from playing for Duke. So he should go to the pros and get the contract,” says Michael J. Tomas III, finance professor and co-author of the study with accounting professor Barbara Arel.

Noting that the average NBA career length is just 4.8 years, Arel and Tomas reimagined the NBA’s rookie salary scale—which currently awards the highest salary to the player picked first in the draft and declines with each successive player picked—in a way that considers both draft pick position and class year. “This is our attempt to show that you could alter the NBA draft schedule to try to incentivize student-athletes to stay in college. There’s been a big discussion about people leaving early to go to the NBA draft, and I think that revolves around the idea of wanting to see them get an education,” says Tomas. Their study proposes a pay scale that locks in salary gains as athletes advance toward graduation and incorporates yearly bonuses into their salaries determined by class year. Specifically, it offers a drafted freshman 60 percent of the current NBA rookie salary base and ratchets up to 120 percent for a drafted graduate in that same position.

Inspired by a ratchet option or cliquet option in the finance industry, the professors say that ratcheting up rookies’ salaries this way would ultimately “provide the incentive for players to delay entering the draft until they are ready to contribute to the NBA, but still allows an early exercise decision to remain rational for the very top prospects.” Subsequently, the researchers argue, the NBA’s labor market would improve as a whole as drafted athletes enter the NBA more prepared for the pro game following the additional seasons of college basketball.

3 QUESTIONS |

Bryn Geffert is passionate about “making the academy’s research available to anyone, anywhere, regardless of means,” and he believes UVM can play a leading role in creating new models that make that vision possible. It’s work he spearheaded as library director at Amherst College and a focus he’ll continue as dean of UVM Libraries, a role he assumed at the beginning of this academic year.

Brynn Geffert dean of libraries

What’s problematic about the current model of sharing the academy’s research?

GEFFERT: As librarians, we talk a lot about a crisis in scholarly communication. Faculty at UVM and faculty everywhere receive money from the federal government, from philanthropic organizations, and from tuition and fees—all money well spent to produce good research. Our faculty then seek publishers—often commercial publishers—to distribute what they produce. These publishers, however, require our faculty to sign over copyright to their work without compensation. The institution that finances the research receives no compensation. The government receives no compensation. Out of necessity (given the paucity of publishing outlets), we give our information, produced in the public interest, to commercial publishers; the publishers then sell it back to us, usually in the form of journals that cost thousands of dollars a year for a single title, while denying access to those unable to pay, i.e., to most of the world’s populace.

So we’re caught in a system that effectively locks up the information we have worked so hard and spent so much money to produce. This state of affairs is especially troubling at land grant institutions like UVM, whose mission is to serve the public good. We serve the public when we create research, but we do not serve the public when we give that research away to people who lock it up.

How can libraries help solve this?

GEFFERT: Libraries need to begin imagining themselves not merely as purchasers of information but as producers as well. Some of the most exciting work afoot in academic libraries can be found at institutions creating academic presses under the auspices of their libraries. These presses provide the same sort of peer review and editing one expects at an established press. But these presses, instead of selling the information, make it freely available online. These libraries have decided, in other words, to produce information in ways consonant with the values of the academy.

This does not mean that libraries are about to quit buying books or journals anytime soon. But when we do purchase information, we must do so in accord with certain commitments. We must carefully review contracts to make sure they contain nothing prohibiting us from sharing electronic books and journals with people outside the institution. We must demand the right to send material freely through interlibrary loan. And we must help our faculty get copies of their research into repositories where it is freely available.

This is all to say we must produce and purchase information in ways that do not lock it up; we must spend our money on initiatives that make information universally available.

What else are you focused on in your role as dean?

GEFFERT: I believe UVM’s libraries should be evaluated in part by whether our graduates know how to conduct good research. By “good research” I don’t necessarily mean laboratory research. I simply mean we must be able to say “yes” to the following questions: Can a student ask a good, researchable question? Can she identify the disciplines that have something to say about that question? Can she then track down reputable information, evaluate it, synthesize it, and ultimately produce something original? These are the skills college graduates need in civil democracies, and libraries should work closely with faculty to help teach those skills.

We have a department in the libraries called Information and Instructional Services, and its members work primarily as teachers. They work with faculty to think about the kinds of research skills they want their students to obtain. Often, they’ll contribute to research assignments designed to help students develop those skills. They’ll visit classes to work with students, and sometimes they’ll even embed themselves in a class, participating in the curriculum. I want our students to know that there are good, smart people at the library who want nothing more than to work with them and teach them essential life skills.

| THE GREENTHE GREEN

More efficient solar cells, lighter airplanes, and safer nuclear power plants are among possible applications of this research.

Super Silver Building a Better Metal

ENGINEERING | A team of scientists has made the strongest silver ever—42 percent stronger than the previous world record. But that’s not the important point.

“We’ve discovered a new mechanism at work at the nanoscale that allows us to make metals that are much stronger than anything ever made before—while not losing any electrical conductivity,” says Frederic Sansoz, UVM materials scientist and mechanical engineering professor who co-led the new discovery.

This fundamental breakthrough promises a new category of materials that can overcome a traditional trade-off in industrial and commercial materials between strength and ability to carry electrical current. In addition to UVM, the research team included scientists from Lawrence Livermore National Lab, the Ames Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and UCLA. Their results were published in the journal Nature Materials.

By mixing a trace amount of copper into the silver, the team showed it can transform two types of inherent nanoscale defects into a powerful internal structure. “That’s because impurities are directly attracted to these defects,” explains Sansoz. In other words, the team used a copper impurity—a form of doping or “microalloy” as the scientists style it—to control the behavior of defects in silver. Like a kind of atomic-scale jiu-jitsu, the scientists flipped the defects to their advantage, using them to both strengthen the metal and maintain its electrical conductivity.

Sansoz is confident that the team’s approach to making super-strong and still-conductive silver can be applied to many other metals. “This is a new class of materials and we’re just beginning to understand how they work,” he says. And he anticipates that the basic science revealed in the new study can lead to advances in technologies— from more efficient solar cells to lighter airplanes to safer nuclear power plants. “When you can make material stronger, you can use less of it, and it lasts longer, and being electrically conductive is crucial to many applications,” he says.

A Vermont Original

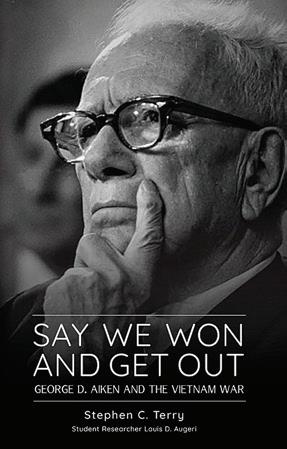

Across more than three decades, from 1941 to 1975, Senator George Aiken was a prominent voice on Capitol Hill during tumultuous times, helping to shape the nation’s course on issues from the Vietnam War to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. And throughout that long political career, from which he retired as senior member of the Senate, Aiken was what is now an increasingly rare animal—a legislator who consistently sought to bridge the partisan divide. A Republican, Aiken ate breakfast every morning with majority leader Sen. Mike Mansfield, a Democrat. (The Vermont senator always kept it simple, favoring an English muffin with peanut butter and coffee.)

Say We Won and Get Out: George D. Aiken and the Vietnam War by Stephen Terry ’64 details Aiken’s life and rise to prominence in the U.S. Senate—examining how his approach to politics stemmed from his early life as a farmer and horticulturist in Putney, Vermont. The author, whose credentials include working as a senate staffer for Aiken and serving as managing editor of the Rutland Herald, draws from historical records to weave a tale through Aiken’s early life, his rapid ascendance in Vermont politics, his public service in the nation’s capital, and his evolving views of the Vietnam war. The book includes Aiken’s “Declare Victory and Go Home” speech, in which he never actually spoke those oftquoted words.

As the Watergate cover-up unraveled and possible impeachment of Richard Nixon loomed, Aiken and other key senior Republicans decided they could no longer support the president. Nixon resigned his office after GOP senators Barry Goldwater and Hugh Scott told the President that the Senate would convict him if the full House voted to impeach.

The book’s inclusion of a 1973 Vermont Life interview with Aiken conducted by a

freelance journalist named Bernie Sanders offers a very different echo of today’s political headlines. In his capacity as an Aiken staffer, author Steve Terry was at the senator’s side for the interview as Sanders asked Aiken about the changing nature of Vermont, about businessmen running government, about corporations taking over Vermont businesses, and about all of the presidents that Aiken served with.

The story of George Aiken’s life and politics couldn’t be told without including a close look into the role of his second wife, Lola. The daughter of a Barre granite worker, she was also deeply rooted in Vermont and was a fierce advocate for her husband and his legacy for years after his death in 1982. Lola Aiken passed away in 2014 at age 102.

UVM student Louis Augeri worked with Terry as research assistant on Say We Won. The dual political science and history major won the 2018 Green Mountain Scholar Award for outstanding student research. An extensive companion website, senatoraiken.com, was developed by Eliza Giles, media director at CRVT.

The Aiken biography is published by the Center for Research on Vermont and White River Press with support from the Silver Special Collections Library and Continuing and Distance Education at the University of Vermont’s George D. Aiken Lecture series.

MEDIA |

GET YOUR ‘BARBARIC YAWP’ ON

Once a literature professor, always a literature professor. Professor Emeritus Huck Gutman continues to explore great poems and share his thoughts on them via his popular listserv poetry@list.uvm.edu. Current “students” on the listserv include hundreds of UVM alumni and many of the nation’s top political leaders, who Gutman connected with during his years in Washington, DC, as chief of staff for Sen. Bernie Sanders. To join, or re-join, go to poetry@list.uvm.edu, and click on subscribe in the righthand column.