45 minute read

News and views from around campus

Discovery

RESEARCH, INNOVATION, IDEAS

Advertisement

FINDINGS

Dog bites more likely in cities

City dwellers are nearly twice as likely to be bitten by a dog than people living in the country, and most of those bites involve an unleashed dog, according to researchers with U of G’s Ontario Veterinary College who surveyed more than 2,000 people for information to help prevent dog bites.

Dogs are more common in rural households, but the percentage of dog bites in the country was only about half that in cities.

Population medicine professor Jan Sargeant and PhD student Danielle Julien found 77 per cent of bites involved unleashed dogs. Seventeen per cent of bites were from dogs that were not vaccinated against rabies.

Learning that dog bites are more common in urban versus rural settings is important because it spurs further inquiries into the causes, says Sargeant.

“When you know these things, you can target messages more specifically. The more specifically you can target to people’s individual situation, the more likely it is to resonate with them and the more likely you are to effect some change.”

The researchers set out to determine the differences between urban and rural communities in numbers of dogs, dog ownership dynamics and human exposure to dog bites, says Julien.

“All are important considerations in the planning and implementation of public health strategies related to zoonotic disease awareness, prevention and control, and for the promotion of responsible dog ownership,” she says.

Human exposure to dog bites is an important and often serious public health issue, Julien adds.

“Some of the more important concerns surrounding the issue of dog bites include the repercussions of physical and emotional trauma experienced by bite victims, and the potential risk of transmission of rabies.”

The main transmitters of canine rabies to humans are domestic dogs.

“In Ontario, dogs three months of age or older are legally required to be vaccinated against rabies,” says Sargeant. “These findings will not only help shape public health measures related to preventing dog bites but also bring awareness to the need for the rabies vaccine.”

RESEARCH BRIEF

U of G helping restore endangered butterfly species

The mottled duskywing butterfly has nearly vanished from Ontario, but University of Guelph biologists hope to help restore the endangered species. Federal funding worth $825,000 will drive a five-year research project intended ultimately to reintroduce the insect.

The goal is to reverse the devastating effect of habitat loss due to human development. The species was declared endangered in Canada in 2012, and lives in only a few small pockets in the province.

“If it works, it will be a big achievement,” says integrative biology professor Ryan Norris, adding that he hopes the project will also yield insights about restoring other threatened creatures. He said no butterfly has been successfully reintroduced in Ontario.

RESEARCH BRIEF

Women and girls with disabilities face the highest rates of poverty and gender-based violence in the world, a problem believed to have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

U of G political scientist Deborah Stienstra will lead a seven-year study to learn about challenges for women and girls with disabilities around the globe and to identify ways Deborah Stienstra to dismantle barriers facing what is considered one of the most marginalized groups in the world.

“By focusing attention, increasing knowledge and creating new opportunities with women and girls, we will create better inclusion,” says Stienstra, who is director of U of G’s Live Work Well Research Centre and holder of the Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work.

Supported by a $2.5-million federal Partnership Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the study will initially focus on the effects of the pandemic on women with disabilities in Canada, Haiti, South Africa and Vietnam.

FINDINGS

Parental stress linked to low screen-time enforcement

Canadian parents under stress, including those dealing with COVID-19 pandemic pressures, are less likely to monitor and limit the screen time of their young children, according to a U of G study. Stressed parents are also more likely to use their own devices in front of their kids.

The researchers found that when parents are under stress, household rules about screen time often go out the window. Moms and dads are not equal: mothers who reported high stress said they were more likely to use devices in front of their children PARENTING STRESS INFLUENCED MOTHERS AND FATHERS DIFFERENTLY IN REGARD TO CHILDREN’S SCREEN TIME.

and less likely to monitor or limit their kids’ screen use, unlike highstress fathers, who were more likely to limit children’s screen time.

Lead author Lisa Tang, a PhD student in the Department of Family Relations and Applied Nutrition, says, “We found parenting stress does indeed affect how parents manage screen time but influenced mothers and fathers differently.”

NOTEWORTHY

U of G innovation helping with PPE

A University of Guelph innovation is now being used to sanitize personal protective equipment for safe reuse.

Clean Works Medical in Beamsville, Ont., and Pure Life Machinery are using “clean flow” technology developed by U of G food science professor Keith Warriner and post-doc Mahdiyeh Hasani.

A portable disinfection device, the company’s Clean Flow Healthcare Mini kills pathogens using ultraviolet light, hydrogen peroxide and ozone. Each device can sanitize up to 800 N95 masks per hour and can also sanitize face shields and goggles.

Clean Works adapted the U of G technology in April and was soon

serving 50 health-care institutions across Canada. The project is a partnership with a Niagara-area company and is supported by a $2-million provincial investment from the Ontario Together Fund.

Discovery

RESEARCH BRIEF

Monitoring river health in Indigenous communities

Under a multi-year environmental DNA metabarcoding project, researchers are identifying organisms to gauge the health status of waterways in little-studied parts of the country, including areas where Indigenous peoples have lived for generations.

The STREAM (Sequencing the Rivers for Environmental Assessment and Monitoring) project involves citizen scientists and dozens of members of Indigenous communities in collecting samples for data to monitor freshwater health.

“These communities are well aware of the potential issues affecting their environment and they want timely and comprehensive access to biodiversity information, especially for freshwater biomonitoring. We can provide that using cutting-edge metabarcoding techniques developed at U of G,” says project lead Prof. Mehrdad Hajibabaei, Department of Integrative Biology, and a member of the University’s Centre for Biodiversity Genomics.

Metabarcoding technology developed by his lab allows scientists to analyze DNA and identify numerous organisms at once.

“We can turn around results to a community group within

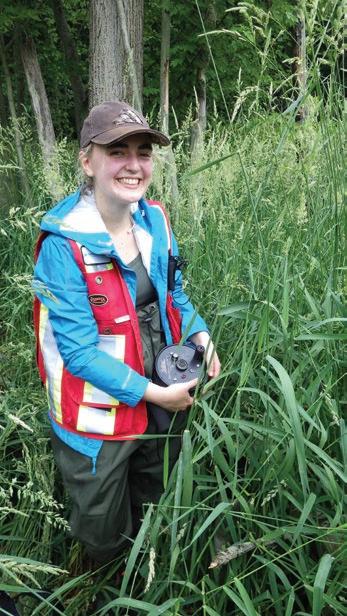

Members of Blueberry River First Nations doing field training for ecosystem health assessments. Indigenous knowledge is meeting University of Guelph-developed technology to help assess the health of rivers in Canada.

STREAM project coordinator Chloe Robinson

two months using metabarcoding,” which is several times faster than methods that use microscopes to analyze single organisms, says Chloe Robinson, a post-doctoral researcher who is also STREAM’s project coordinator.

Many of Canada’s important but little-researched waterways are in lands where Indigenous peoples have lived for generations, Hajibabaei says.

“We have partnered with Indigenous communities and seek their perspective to understand which sites are most important. So these partnerships have been invaluable to helping us study the health of freshwater ecosystems.

“Without these groups, it would be impossible to access remote sites to do this research. We hope to create new partnerships with more Indigenous communities so we can broaden this research.”

Data from the catalogued samples are shared with other STREAM project partners, including World Wildlife Fund-Canada, Living Lakes Canada, and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

RESEARCH BRIEF

Novel project to detect COVID-19 in waste water

Looking for early warning signs of a COVID-19 outbreak on a university campus? Check the sewers.

U of G researchers aim to test waste water to detect levels of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – released in human feces – from student residences. Detecting higher levels of the virus in the sewer system may help prevent outbreaks on university campuses, says food science professor Lawrence Goodridge.

He’s working on the project with other U of G researchers and scientists at Laval University and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Previous research shows that the virus appears in waste water roughly a week before it shows up in a population, says Goodridge, director of the Canadian

Prof. Lawrence Goodridge

Research Institute for Food Safety at U of G.

“If we find evidence of the virus in waste water, it’s an indication that there is potentially a problem coming up. With that information, we can then take steps to take early action against that potential problem.”

Engineering professor Ed McBean and student research assistants are now taking waste water samples at East Residence.

By identifying the virus in communities, says McBean, the research could help target individual testing more efficiently.

It could also reinforce public health practices from mask-wearing to handwashing, says Goodridge. “We appear to be the first in Canada to test a campus residence and use the data to try to make the campus safer.”

FINDINGS

Study predicts increased exposure to extreme heat in cities

Rising temperatures from climate change and increased urbanization mean city residents will experience more extreme heat in the future, but how much more?

A study co-authored by a University of Guelph researcher projects that more people will be exposed to intense heat due to increased greenhouse gas emissions and urban population growth.

“A major reason that cities are often warmer is the built infrastructure – the paved roads and the building and residential roofs that absorb and emit heat, the tall buildings that retain that heat – those are major factors that make cities hotter than rural areas,” says Prof.

Scott Krayenhoff, School of Environmental Sciences, who co-authored the study with researchers at Arizona State University.

The researchers calculated that population-weighted exposure to extreme heat will increase at least 12-fold by the end of this century. As much as two-thirds of the world’s people are projected to be living in cities by midcentury.

Study findings may help planners and policy makers in adapting to climate change and in implementing urban features from street treeplanting to additional cooling centres.

NOTEWORTHY

U of G app could improve COVID-19 contact tracing

A University of Guelph-led project may make contact tracing technology more accurate, helping to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Smart Contact Tracing, a smartphone app, ensures greater accuracy and privacy than other systems while identifying recent contacts infected with COVID-19 and reminding users to maintain physical distancing, says engineering professor Petros Spachos.

“The application we developed could be very useful as an upgrade to any contact tracing application available,” he says.

Apps perform well on phones that are “visible” to each other but lose accuracy when the devices are in a pocket, purse or backpack. The U of G app uses machine learning to improve accuracy in “hidden phone” scenarios from about 56 per cent to 87 per cent.

The app also “learns” to distinguish when the user is at home or in another private space and stops recording contact information there.

The researchers have worked with a Toronto wireless communication firm on development of the app.

Veterinary care where it’s needed

OVC PROGRAMS AIM TO BROADEN COMMUNITY ACCESS TO SERVICES

STORY BY ANDREW VOWLES ILLUSTRATIONS BY JEFF KULAK

For each of the past eight years, the Community Outreach Club at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) has organized and hosted animal wellness clinics at Kettle and Stony Point First Nation in southwestern Ontario. OVC student and staff volunteers have also offered the program at nearby Walpole Island First Nation for the past four years. Early in 2020, the group was preparing for its annual outreach visits. Then came the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns and other public health restrictions.

“We were gearing up for our largest clinics when COVID-19 struck and it became very apparent that in-person clinics would not be safe or possible this year,” says clinical studies professor Shane Bateman, who helps run the program in collaboration with the First Nations as well as local veterinarians and pharmaceutical companies. “We elected to proceed with offering some services virtually, including parasite prevention. We used telemedicine to ensure members of the community – humans and animals – would be protected.” Noting that internal parasites, as well as fleas and ticks, can transmit disease from animals to people, he adds, “Parasite prevention was deemed to be a public health priority this year.”

Partnering with Indigenous communities is just one example of a growing movement to widen veterinary care and community practice for underserved animals – and often overlooked clients – in Ontario and across Canada. Over the past decade, the cost of providing gold-standard veterinary care has risen significantly, as practitioners looked to apply medical research and technological advances for their patients. Those increasing costs have prevented large swaths of people and their pets from receiving even basic veterinary care – often creating a moral dilemma for practitioners looking to provide care for clients while ensuring a thriving practice for themselves (see accompanying story).

A 2018 study in the United States found that one out of four households with pets experienced a barrier to veterinary services, mainly financial. The “money gulf” is what one Partnering with Indigenous communities is one example of a growing movement to widen veterinary care for underserviced regions.

Prof. Shane Bateman

Dean Jeffrey Wichtel

Florida practitioner called it in a 2017 article listing the top challenges for veterinarians. In a follow-up article two years ago in the Canadian Veterinary Journal, U of G pathobiology professor emeritus Carlton Gyles found that a similar divide exists in Canada. Says Bateman, “Veterinary medicine is very focused currently on supporting the usual clientele, but we’ve neglected a whole segment of our community and population who in some ways depend on that human-animal bond even more than the average citizen does.”

that’s all changing, says OVC dean Jeff Wichtel. An $11-million gift announced in fall 2019 is intended to effectively reinvent veterinary education. As the largest single donation in the college’s history, the funding comes from longtime U of G and OVC benefactors Kim and Stu Lang through their Angel Gabriel Foundation. With its connections to top-flight academics performing clinical trials and benchtop research on everything from cancer treatment to heart health to infectious diseases, the college always provides gold-standard health care through the college’s Health Sciences Centre, says Wichtel. But he and others want to train tomorrow’s grads to meet the growing need for affordable care for all animals, including societal sectors that have traditionally been underserved. “We want our graduates to leave veterinary college understanding, ‘This is what vets do,’” he says. “This shift is a real moment of transformation in veterinary medicine and probably the biggest reframing of our curriculum in 20 years.”

Named the Kim and Stu Lang Community Healthcare Partnerships Program (CHPP) – the first of its kind in Canada – this initiative will refocus teaching, research and animal health care to include that neglected sector. To do that, the college will develop partnerships with humane societies, veterinary outreach organizations and social service agencies working in community health care. Students will gain broader experiential learning opportunities, including a clinical rotation in Northern Indigenous communities. For the first time in Canada, graduate students will have a chance to focus their studies on community or shelter medicine. The gift has also led to the creation of Remy’s Fund – named for one of the Langs’ numerous rescue dogs – that will help subsidize medical expenses for underserved owners with animals in need. The Lang gift will also support capital improvements on campus as well as new positions, including a full-time veterinary director and an academic professorship or chair in the field, both to be appointed by early 2021.

For Bateman, the project makes sense for many reasons, not least the blend of expertise on campus, from the Health Sciences Centre and related services, to the college’s “one health” focus that encompasses well-being of humans and animals, to the University’s strengths in interdisciplinary research and learning. “We have the right

expertise here,” says Bateman, now serving as the program’s interim director. “A lot of features make OVC the right place for this to happen.”

Indeed, it’s already happening – including through those annual wellness clinics to First Nations communities in southwestern Ontario. Working mostly with dogs – several hundred in all – and supervised by Bateman as faculty adviser, about 15 student and professional volunteers normally visit to provide an overall health check, as well as vaccination, microchipping and protection against various parasites. Clients obtain those services for less than one-quarter of what they might pay in a regular veterinary clinic – no small consideration, For the first time in Canada, graduate students will have a chance to focus their studies on community or shelter medicine.

says club president Taylor Morris, a third-year doctor of veterinary medicine (DVM) student. “It’s not that the people living in these communities don’t want to care for their pets or don’t understand the need,” says Morris, who has also volunteered at pop-up clinics in Guatemala. “They lack access to veterinary care and money is tight, so they can’t afford it.” The club raises money to buy supplies and medications and relies on support from pharmaceutical companies to keep costs at a minimum for families.

Tracy Bressette, a resident of Walpole Island First Nation, says the virtual care helps ensure the continued health of her dogs. “They were able to provide medicine for my pets, which they desperately need because we have lots and lots of mosquitoes and wood ticks in this area,” she says. “So they really needed the heartworm prevention and so on.” Bressette says the service helps area clients, few of whom can transport their pets to the veterinary clinic in nearby Wallaceburg. Even the reduced service due to COVID-19 was a big help to many pet owners, she adds: “The fees are great compared to what a veterinarian would charge, and I

think that’s where a lot of people really benefit.”

After the virtual appointments, medications were labelled and packaged for individual animals. They were then bundled together and shipped to the health centres in both communities, where they were distributed by local teams. Regulations preventing veterinarians from prescribing medications through telemedicine have been relaxed during the pandemic, says Bateman. “Our pharmaceutical partners – Boehringer Ingelheim, Elanco and Merck – all stepped up and allowed us to deliver this important care in a unique way. It allowed our students the opportunity to learn so much about not only telemedicine but also how to work with First Nations people in providing health care for their companions.”

Since it began, the program has seen 1,000 pets from 665 families. This year’s telemedicine effort served more than 170 pets. Christina Jobson, entering her third year at OVC, worked on the project this year from her home in Guelph. “It’s very different than the clinics we’ve run in the past,” Jobson says. “Not being able to run the clinics in the First Nations this year, but still being able to find a way to provide support to the communities, has been a really great experience.” The medications and preventive care provided remotely will help until the team can get back into the communities, she adds.

Supported through the CHPP, the program not only provides care to animals in First Nations but also ensures OVC students have the specific knowledge and skills to extend animal health care to these communities, “There’s a significant lack of access to veterinary care in many remote communities. Some communities have zero access.”

DVM Linda Bolton

Prof. Katie Clow

Prof. Gordon Kirby

says Bateman. “Going forward, this type of work will be a core activity of the CHPP, and we will be expanding our impact in other communities.”

This year, under a grant from PetSmart Charities of Canada, OVC will offer similar services through a new fourth-year rotation in Aroland First Nation, about four hours’ drive northeast of Thunder Bay. Currently, the closest veterinary service is provided by a practitioner from Sault Ste. Marie who runs a mobile clinic once every two months in Geraldton, about an hour away from Aroland. “There’s a significant lack of access to veterinary care in many remote communities. Some communities have zero access,” says population medicine professor Katie Clow. Beginning in spring 2021, about eight students will spend a week there with Clow, Bateman and other OVC members, learning from the community and providing programs including youth education and scholarships to enable youngsters to visit U of G.

Biomedical sciences professor Gord Kirby says the program partly reflects growing student interest in serving wider communities. “They are very plugged in,” he says. “A lot of this is being driven by students’ desire to explore alternative career paths.” Bateman says the program will likely benefit community members, too. “Veterinarians impact human health because of the human-animal bond,” he says. Beyond that, caring for animals may enable the veterinary team members, along with practitioners from other disciplines, to address human health concerns from smoking cessation to vaccinations: “This is an opportunity to influence human health care decisions and behaviour through relationships with their pets.”

In 2019, Kirby and Clow took part in another northern clinic program run by U of G grad Linda Bolton, DVM ’84 and owner of Mullen Small Animal Clinic in Walkerton, Ont. Under the Grey Bruce Aboriginal Qimmiq Team, she leads twice-yearly volunteer groups of veterinarians and technicians to semi-remote First Nations communities in Northern Ontario to provide humane dog population control through spaying and neutering, vaccination, parasite control and microchipping. Running since 2012, the program has spayed and neutered more than 850 dogs and performed wellness treatments on more than 1,300. Bolton says the communities help to partially fund visits, and veterinary care is offered pro bono to owners. “By helping the dogs, we will be helping the community members,” she says. “Each community has different resources, cultural priorities and socioeconomic issues such as isolation and poverty. I wanted to see the North and help in my backyard. I have thought about rabies clinics in Africa, but why do that when there’s a need in Ontario?”

Meagan Wellon, a veterinary technician in OVC’s large-animal clinic, has accompanied Bolton on three week-long trips to two First Nations commun-

ities. She says the project fits with her long-time interest in advocating for animals through their owners. “Education is important for the one health aspect,” she says. “Teaching owners about population control and helping them learn to interact with their dogs in a safe way helps make the community safer.”

treat a pet and treat the person: That might be the mantra for Michelle Lem, a 2001 DVM grad who runs Community Veterinary Outreach from Ottawa. Now offered in several Canadian communities as well as Kansas City, Missouri, the program provides accessible care for people and their pets who are experiencing homelessness and housing vulnerability. Clinics are offered every other month for clients referred through community agencies. “For many people facing socioeconomic barriers to care, animals are incredibly important in their lives.”

In an unusual twist, those pet owners can also obtain healthcare services for themselves, ranging from smoking cessation to oral and dental consultations to immunizations. “What makes the program unique is that human health services provided by collaborating practitioners from other disciplines are paired with veterinary services,” says Lem, who studied social work at Carleton University and completed a master’s degree at U of G on effects of pet ownership on young people who are homeless or at risk. She says many clients worry more about their animals’ health than their

DVM Michelle Lem

own. “For many clients, just getting out of bed in the morning is a huge challenge, and pets are huge motivators, so we work with that in a non-judgmental way.” She’s been working on animal care guidelines for shelters for people who are homeless or victims of domestic violence; those guidelines were released earlier this year.

“For many people facing socioeconomic barriers to care, animals are incredibly important in their lives,” says Karen Ward, chief veterinary officer with the Toronto Humane Society (THS). Far from merely sheltering animals, the agency provides subsidized procedures, notably spay and neuter procedures, and has delivered outreach services to First Nations. The THS has partnered with Meals on Wheels and other organizations delivering food to households,

Veterinarians facing mental health challenges

Pets need veterinary care, but practitioners may need some attention, too. Canadian veterinarians have higher stress, burnout, compassion fatigue, anxiety and depression, and reported more suicidal ideation and lower resilience than the general population, says a landmark 2020 study published by University of Guelph researchers.

The team surveyed all of Canada’s roughly 12,500 veterinarians working in companion animal care as well as food safety and agricultural support from February through July 2017. Some 1,400 practitioners (about 10 per cent) responded; just over three-quarters of respondents identified as women.

About 30 per cent of women veterinarians reported a history of mental illness, compared with almost 27 per cent for men. Just over 15 per cent of women reported mental illness at the time of the survey, compared to just over 9 per cent for men – a key point, says lead author Jennifer Perret, a veterinarian now completing her PhD with Prof. Andria Jones-Bitton in OVC’s Department of Population Medicine.

“Overall, female veterinarians have higher poor mental health outcomes than men,” says Perret, who works part-time at the Guelph Animal Hospital. “We really need to focus on supports for women.” The study says caregiver mental health can be improved through wellness interventions such as mindfulness and resilience training and improved workplace culture. The researchers also recommend management skills training, reduced Prof. Andria Jones-Bitton working hours and more support services for veterinarians.

This winter, Jones-Bitton, DVM ’00, was appointed as director of well-being programming for OVC, including implementing training across the college curriculum.

She says veterinarians often find themselves caught between a desire to help animal patients and clients’ inability to pay for expensive diagnosis and treatment. “It’s important that we train veterinary students and veterinarians in the profession to build resilience skills,” says Jones-Bitton, whose research includes studying aspects of communication and other interpersonal skills. “We all need a sense of meaning and purpose in our lives.” “It’s about the simple act of caring and providing dignity and respect to another human being who has an animal.”

DVM Karen Ward

including dog food for pets. In 2019, the agency began offering access to free veterinary care for people in the city’s homeless shelters. Partnered with the People with AIDS Foundation, it provides temporary fostering of animals while their owners get treatment.

From diagnostic tools to treatment options, veterinary care has improved since Ward completed her DVM in 1990. Those advances are double-edged, she adds. “There’s such a focus on technological advancement to the detriment of some folks of offering accessible care. Veterinary medicine doesn’t always have to function at that standard. You leave so many behind and that’s not right, not just and not fair. We are doing a disservice to the profession and the community at large when we chase that gold standard. The value that life has should not be reliant on your financial resources.”

back at OVC, that sentiment resonates with Bateman. For its nearly 160 years, the college’s clinical training has focused on providing excellent veterinary care and equipping graduates to succeed in practice. The new community healthcare program is about widening access to veterinary care, he says, and growing practitioners’ hearts at the same time: “It’s about the simple act of caring and providing dignity and respect to another human being who has an animal.”

Macdonald Institute (left) and Macdonald Hall (right), November 1919.

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

STORY BY GRAHAM BURT

This fall brought a new semester – and new ways of learning – for students of all ages, from primary classrooms to virtual university lecture halls. Although COVID-19 has been a first in our lifetime, earlier outbreaks on and off campus offer potential lessons for today, from quarantining and curtailing group activities, to keeping kids safe at school, to wearing personal protective equipment.

Since COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic on March 11, many people have referred to “unprecedented times.” But Graham Burt, a former archival assistant at U of G’s McLaughlin Library, says while the current pandemic is unparalleled in our lifetime, it’s hardly unprecedented. He explains why in an article published previously by U of G. Here’s an abridged version of his account:

Beginning near the end of the First World War, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-20 killed about 55,000 Canadians and at least 50 million people worldwide. Among them were at least 15 students and faculty members at the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) and Macdonald Institute, two of the founding colleges of the University of Guelph.

“It soon became evident that Macdonald Hall must be its own hospital, as one after another the students showed symptoms of the malady and were ordered to stay in bed.”

– OAC REVIEW, NOVEMBER 1918

on oct. 2, 1918, OAC students and staff learned that a student, Geoffrey Howard Scott, had died. Training with the Canadian Engineers that summer in Quebec, the 20-year-old entered hospital in late September after appearing “very ill and delirious.” Flu led to bacterial pneumonia, and he died five days later.

By mid-October, half of the student body of 300 people had fallen ill. Those with serious symptoms were sent to hospital, but most were tended on campus. The whole of “Upper Hunt” in Moreton Lodge (the predecessor building to Johnston Hall) and a few rooms in Macdonald Hall were converted into hospital rooms, with patients assessed by doctors and nurses from town.

OAC president George Creelman cancelled lectures for a week. Healthy students were either sent home or quarantined in residence. A few Macdonald Institute students volunteered as nurses and cooks in city hospitals. Campus events, including student-run concerts, plays, dances and athletics, were cancelled or postponed.

Within a few weeks, students and faculty returned to campus, and classes and events resumed. Reporting on a postponed sophomore dance finally held in mid-November, an article in the OAC Review said, “Not only was the flu a thing of the past, but the war’s end came with such a grateful relief that we could well afford to make merry.”

The relief was short-lived.

The flu returned in early December, coinciding with the annual provincial winter fair held in Guelph. After several OAC members began showing symptoms, Creelman again cancelled

classes, postponed exams and sent students home early for the holiday break.

That winter, the flu claimed three OAC members.

Roy Lindley Vining, a 1914 OAC graduate, had been wounded overseas with the Canadian forces. In fall 1918, he became a dairy specialist and lecturer in animal husbandry with the college. On Dec. 19, a week after attending the winter fair, the 31-year-old died of the flu at Guelph General Hospital.

That month, Walter Herbert Scott, a 1916 OAC graduate and physics professor on campus, had volunteered to tend students with flu symptoms. Scott died on Jan. 8, 1919, leaving his wife and seven-month-old daughter.

The final OAC victim of the first flu wave was student Harold “Lindsay” McLaughlin, who died on Feb. 14, 1919.

By mid-February, it seemed that the flu had passed for good.

“At first it was rumoured and then it became only too true: the ‘flu’ was with us again.”

– OAC REVIEW, JANUARY 1920

in january 1920, an article in the Guelph daily newspaper reported the death from pneumonia of Murray Fallowdown, an OAC shortcourse student. Four days later, another college student, George James Tocher, also succumbed to pneumonia. Doctors realized that their pneumonia was only a contributory cause of death. Influenza was back.

From left: Lieutenant Roy Lindley Vining; Kate Morton Sinclair.

Writing about Macdonald Hall on campus, the OAC Review reported that “the drawing room was quickly commandeered and in a few hours was completely transformed into a hospital. When more cases were discovered, the library was used as a ward.”

Unlike in 1918, both Macdonald Institute and OAC remained open. Lectures and exams continued, and even OAC’s annual Conversat ball was held.

On Jan. 30, Macdonald Institute lost its first and only student to the pandemic. Sophomore Kate Morton Sinclair was admitted to hospital after developing double pneumonia and died Jan. 30.

John “Walter” Rutherford Dawson, a short-course OAC student, was also admitted to

hospital, where he developed acute pneumonia and died Jan. 31.

Between Feb. 1 and Feb. 2, four more OAC members died: students Roy “Victor” Wood, Lorne Victor McGee and Douglas Edward Pettypiece; and Walter Lawton Iveson, a professor of chemistry and geology.

Oscar Wilbur Bennett, a 1916 OAC grad, had also been wounded overseas before returning to Canada, where he became a lecturer in the poultry department. He contracted flu and then pneumonia and died Feb. 4.

Within almost two weeks, seven students and two faculty members in OAC and the Macdonald Institute died during the second wave of the Spanish flu. In all, the pandemic claimed the lives of 15 students and faculty, ranging in age from 17 to 32.

Compared with the influenza pandemic of 1918-20, wrote Burt, COVID-19 has been met with improved medical research, health care and medicine. Scientists have a better understanding of how viruses act and spread – knowledge that has led to improved medicine, hygiene practices and general preventive measures. As well, technological advancements give us up-to-date news and instant communications and the ability to continue to learn and work at home.

Although no two pandemics are the same, lessons from yesterday can inform today. History warns us to be proactive against epidemics. Viruses may be invisible to us, but they can be fatal and must be taken seriously. Pandemics can overwhelm hospitals and medical professionals. Protective measures must be implemented early. Halting the spread is a shared responsibility.

The 1918-20 pandemic discussed in Burt’s account was hardly the last outbreak of infectious disease to upend lives on campus and off in the following century.

In an article published this year in The Conversation, U of G history professor Tara Abraham wrote about how Ontario’s worst polio epidemic in summer 1937 prompted school closings and left Toronto playgrounds and beaches deserted.

Polio typically struck during the summer, meaning students lost just a few weeks; COVID-19 affected schooling for weeks earlier this year, with potentially more disruptions to come.

In 1937, parents feared children risking infection. Today, parental anxiety over COVID-19 stems partly from infection fears (albeit much lower than polio infection in children) and partly from work-life stress over caring for and homeschooling their kids.

As with earlier disease outbreaks, wrote Abraham,

back-to-school this fall has required parents to balance their sense of collective responsibility for ensuring public health and their personal responsibility for their own mental health and the health of their children.

For kids returning to the classroom, masks are now as much a part of the back-toschool ensemble as backpacks and lunch bags. Mask-wearing has also become a fact of life for many of their parents in workplaces and other public spaces.

Again, that’s nothing new. In another article this summer in The Conversation, history professor Catherine Carstairs wrote that medical mask-

Walter Iveson (front right) with the College Quartet, 1918.

wearing has a long history – going all the way back to the 17th-century plague. During the 1918 flu epidemic, cities around the world passed mandatory masking orders.

Wrote Carstairs, “Historian Nancy Tomes argues that mask-wearing was embraced by the American public as ‘an emblem of public-spiritedness and discipline.’” That view was hardly universal in 1918-20. Many Canadians were reluctant to wear masks and questioned their effectiveness. At the same time, Japanese embraced maskwearing during the Spanish flu and again in the early years of this century with outbreaks of SARS and avian influenza.

In Canada today, controversies over masks continue, with complaints over lack of comfort and perceived ineffectiveness or concerns that masks impede communications for some people. As a visual representation of the threat of COVID, wrote Carstairs, masks can make people more fearful.

Still, she said, support for mask-wearing appears to be growing in Canada. If earlier outbreaks from the 1918-20 flu pandemic to the 1937 polio crisis teach us anything, it’s that we all must be proactive and that we all have a part to play in ensuring health – our own and that of others around us.

HIRE A UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH CO-OP STUDENT

recruit@uoguelph.ca (519) 824-4120 x52323

• Students are ready to be hired from over 40 co-op programs including Business, Engineering, Computing, Science & Arts

• Hire a student for 4 or 8 month work terms (program specific)

• We support work-from-home placement solutions • Funding has temporarily become more flexible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Visit our website or contact us to learn more

U OF G’S LIVING LAB

AT 50, THE ARBORETUM FOSTERS RESEARCH AND TEACHING,

PROVIDES GREEN RESPITE / STORY BY ANDREW VOWLES

Even for a self-described nature geek, the University of Guelph Arboretum still holds surprises. Case in point: One summer day, Chris Earley was leading a tour group, just a handful among the tens of thousands of people he’s ushered around the grounds as interpretive biologist and education coordinator. Partway through the walk, one student invited him to look at her cellphone picture of a caterpillar. Earley has seen many of the 800-plus kinds of moths and their larvae found in the arboretum, but this was a species never recorded there. Where did you find that? he said.

Gesturing to a cucumber magnolia tree, one of many kinds of endangered plants nurtured on the grounds, she said: Under that leaf, about five seconds ago. “You never know what’s going to pop out,” says Earley, who has worked at the arboretum since finishing his zoology studies here in 1992. Laughing at the recollection, he says, “All the students got to see me all excited. It’s fun not only to be surprised but it’s extra fun to be surprised when you’re with a group of students who can see that surprise and realize: Oh, this is awesome.”

Fifty years after it was established through U of G’s Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) on former farmland, wetland and forest at the east end of campus, the arboretum has become a place for discovery and learning about the natural world. This year, COVID-19 has curtailed or altered many of the activities and programs that normally occur on the grounds, including events planned to celebrate the arboretum’s first half-century of existence. But in many ways, the pandemic has also underlined our need for fresh air and green spaces, says Justine Richardson, appointed earlier this year as the new director. During the shutdowns, essential work on living collections continued and walk-through access was allowed, she says. “People were coming – grandparents, dog walkers, families walking in the morning or evening. That trails were kept open is a recognition of one of our important roles and the need to be outdoors for mental well-being and physical activity.”

Walking through the grounds offers more than just a green respite. As one of fewer than a dozen university-based botanic gardens and arboreta (collections of trees and other woody plants) in Canada, the U of G arboretum is variously called “the green heart of Guelph” and a “living laboratory.” The 400-acre expanse with its mix of open spaces, old-growth forests, provincially significant wetlands, cultivated gardens, woody plant collections – oh, and a disc golf course – offers an experimental site for campus researchers, an outdoor classroom for learners and a natural sanctuary for some 100,000 visitors a year. That mix of research, teaching and outreach was already envisioned by members of the University-wide committee led by OAC from 1964 to develop plans for the arboretum. The arboretum was established under its inaugural director, Prof. Robert James Hilton, in 1970 (see sidebar).

That fall, Alan Watson arrived as a marine biology undergraduate. One of his classes trekked through the nature reserve, a 100-acre portion of today’s arboretum lying south of Stone Road and containing an old-growth forest and wetland. Watson, who later joined the faculty in the School of Environmental Sciences (SES) and eventually became the arboretum’s longest-serving director, remembers his professor explaining that the reserve would become part of a planned nature sanctuary that would eventually green up the entire east end of campus.

Recalling the sparse, young plantings in the early years dotting much of the area formerly occupied by farm fields, Richard Reader says some campus members called the area “a field of sticks.” After joining the former U of G

The arboretum features nearly 10 km of trails, including the newly renovated boardwalk through Wild Goose Woods.

botany department in 1974, he regularly used the arboretum over the next 20 years for studies of old field ecology and routinely took plant ecology classes to the nature reserve. Now retired, he’s one of about 70 arboretum volunteers who work along with the arboretum’s roughly 12 full-time staff and an army of students; he now helps maintain the cultivated gardens and has donated funding for renovations to its rose collection. “The founders had amazing foresight to have thought about developing an arboretum. It provides an opportunity for research to be sustained over time,” says Reader.

Echoing that idea, Watson says many of the arboretum’s trees afford a living record of climate variations over the past half-century – and even over the past two centuries for three old-growth stands: the nature reserve, Victoria Woods and Wild Goose Woods. “The great value of an arboretum within a university is that it provides such an opportunity for long-term research and teaching and opportunities to go back and look at what was happening in the past,” says Watson, who stepped down in 2012 after two decades as director. Besides its utility in tracking climate change, he says, the green space is effectively a 400-acre carbon-sequestering facility. “It’s a huge carbon sink. The University could really highlight that in its quest to become a green university.”

The U of G arboretum contains more than 1,700 kinds of trees and woody shrubs, including nearly all species native to southern Ontario. Specimens include common deciduous trees – beech, maple birch – and many familiar conifers. Maybe more important, says Sean Fox, curator and manager of horticulture, the collection contains about 90 per cent of provincial natives listed as endangered or threatened. “Very early in our history, we started to focus on rare flora in Ontario,” says Fox, a U of G graduate who has spent 19 years at the arboretum.

50 GREEN YEARS

The first proposal to establish a campus arboretum was a 1939 plan by Ontario Agricultural College professor Leslie Hancock for a small tree collection north of College Avenue. In 1963, a year before the University was established, Robert James Hilton proposed what eventually became today’s arboretum.

With the facility’s 50th anniversary pending, the history of the arboretum became the topic of two experiential learning courses taught by history professor Kim Martin last year. Four senior undergrads pored over an extensive collection of materials in the McLaughlin Library archives and conducted oral history interviews.

Fourth-year student Alexa Nitsis focused on conservation programs, including the Elm Recovery Project launched in 1998 by Henry Kock, former arboretum horticulturalist and namesake of the arboretum’s propagation facility. “He was such an important figure in creating this project and reintroducing genetically diverse populations of these elms to Ontario,” says Nitsis.

The students’ findings will be posted on the arboretum website, and Martin hopes to publish the project results in a commemorative book.

Now, using a Learning Enhancement Fund grant from the provost’s office, she is collaborating with the arboretum on a project that will enable visitors to hear recorded audio clips on their cellphones about specific locations and features.

Then and now: The arboretum’s cultivated gardens, including the Italian Garden with its signature pool, fountain and hedges, have evolved over the decades.

Those specimens are grown in the arboretum’s tree gene bank, begun in the 1970s. That genetic archive consists of DNA contained not in lab test tubes but in numerous trees collected in the wild and rooted in orchard-style blocks on the north side of College Avenue, near the arboretum’s R.J. Hilton Centre and Henry Kock Propagation Centre. In turn, the arboretum shares seed and germplasm with other organizations for research and conservation.

Sharing plant material, especially rare specimens, is vital for efforts in rehabilitating endangered species and restoring landscapes. Equally important, the arboretum’s collection records the origin of every specimen planted over the past five decades – where it came from, who collected it, whether it came from seed or a sapling. That’s invaluable for ecologists studying longterm effects of anything from climate change to insect infestation.

The arboretum’s signature rehabilitation effort is its Elm Recovery Project, begun in the late 1990s to save and reintroduce white elm trees decimated by Dutch elm disease. Arboretum staff have collected material from more than 600 surviving elms in Ontario, tested responses to the disease-causing fungus and planted resistant specimens in the gene bank. Fox says he plans to share seed with other centres for reintroduction across Ontario in the next few years.

Widening the lens, the arboretum also serves as a kind of outdoor laboratory for campus researchers and teachers. Those connections are fostered by Aron Fazekas, an educational developer in U of G’s Office of Teaching and Learning who is also a part-time research coordinator for the arboretum. Among researchers mostly from OAC and the College of Biological Science, scientists have visited the arboretum for studies of everything from perennials and pollinators to plant-fungi interactions to bee movement. Research conducted here has resulted in more than 100 peer-reviewed publications.

Fazekas also helps to connect faculty members looking to use the arboretum

for undergrad courses. For a fourthyear SES project course, dozens of students have undertaken projects such as enhancing wildlife habitat and encroachment and control of invasive species. These collaborations give the arboretum access to student researchers, while students and teachers benefit from a campus green space to study various topics. “That close access makes things easier for instructors and students,” he says. “It also fosters a connection to place that you can’t replicate elsewhere.”

Normally, the arboretum plays host to about 100,000 visitors each year for everything from conferences and wedding receptions, to nature workshops and interpretive tours, to indoor and outdoor arts programs, to an environmental leadership program that has brought high schoolers to spend an entire semester learning at the arboretum’s nature centre. Over the years, staffers have led groups on owl prowls, maple syrup days, and plant and animal identification treks.

Although the arboretum has remained open to visitors, this year’s pandemic has prompted a shift to virtual learning, including a family nature program that Earley ran online this past summer. Under a pilot program this past spring, he and Richardson partnered with experiential learning leaders at local school boards to send multilingual tree resources home to all Grade 6 students and classroom teachers for the biodiversity curriculum. They expect to broaden that virtual outreach to other topics and other boards. “We want to provide inquiry-based materials that parents, teachers and students can use to connect to the natural world,” says Richardson.

That’s also happening through social media being shared by naturalist interns Jenny and Kitty Lin, hired by the arboretum in 2019 following their biology studies at U of G. The twins initially helped lead tour groups around the arboretum; this summer, they have provided weekly virtual tours through

Naturalist interns Kitty (left) and Jenny Lin continue to provide virtual tours of the arboretum during this year’s pandemic.

videos available on YouTube, Instagram and other channels. In recent episodes, they’ve explored everything from parasitic wasps to plant defences against insect predators. “We’ve seen a huge increase in our social media following,” says Kitty, pointing out that virtual programming now brings the arboretum to viewers anywhere in the world. Closer to home, says Jenny, the arboretum continues to attract pandemiccloseted visitors looking for a dose of the outdoors. “It’s a place for people to come and enjoy nature,” she says.

Fostering research, teaching and public connections is where the future lies for the arboretum, says Richardson. Referring to a pending update of the arboretum’s master plan, she says, “At 50, this arboretum has relevance to major issues of our day, from climate change, to reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, to mental health and well-being. We want to look back and celebrate how we’ve grown and look forward to strengthening the role of the arboretum in research, teaching and connecting people with nature. That connection is the first step to valuing nature.”

Matured from those early plantings, the arboretum now nurtures extensive biodiversity, a key focus for a University that is home to internationally heralded researchers and global networks of scientists, conservationists and agencies. “People are not going to protect the planet without being aware of what they need to protect,” says Earley. “This is an amazing green space in the city. We have an incredible diversity in 400 acres that’s all part of a cityscape. It allows people to realize you don’t have to go to Algonquin Park or a big national park to learn about nature. Nature is all around you: you just have to get there.”

The University of Guelph Arboretum has kicked off several months’ worth of 50th-anniversary celebrations. Events include an online speaker series, sharing pictures and stories on the website and launching both a fundraising campaign and a new master planning process. For information, see: uoguelph.ca/arboretum.

New chapters, sights & sounds

The latest books, art and exhibitions by U of G faculty and alumni

RODERICK HODGSON

Barns – Classic Structures From Across the Land

viewpoint, there is a need to deal with complicity and to share knowledge that can open more doors to equality,” she says.

Roderick Hodgson, BA ’78, has written his 14th book. Barns – Classic Structures From Across the Land details the evolution, style and construction of the grand rural structures. Barns have been his interest for more than 40 years.

EUGENE BENSON

The Symmetry of the Tyger

In his memoir The Symmetry of the Tyger, professor emeritus Eugene Benson, School of English and Theatre Studies, surveys 90 years of travel, adventure and engagement in Canadian culture. The book charts the author’s own adventures while travelling around the globe and includes recollections of his time at U of G.

KATHLEEN HEPBURNE

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open

Kathleen Hepburne, MFA ’12, co-wrote and co-directed the critically acclaimed and multiple award-winning film The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open with Elle-Maija Tailfeathers.

The Toronto Film Critics Association gave the Indigenous story the 2019 Rogers Best Canadian Film Award, worth $100,000. Praised by critics across North America, the film was named one of the top 10 Canadian movies of 2019 and was named best Canadian film by the Vancouver Film Critics Circle.

MARK A. MCCUTCHEON

Shape Your Eyes by Shutting Them

Mark A. McCutcheon, BA ’95, PhD ’06, a professor of literary studies at Athabasca University, has published his first book of poetry. Shape Your Eyes by Shutting Them was published by Athabasca University Press in 2019. Literary critic Di Brandt called the inventive collection a “romp through the surreal landscape of our times.”

LAUREN SATOK

Unsettled: The Art of Remapping a History of Erasure

Visual artist Lauren Satok, BFA ’02, creates landscapes that explore the effect of colonization on the environment. Her exhibition Unsettled: The Art of Remapping a History of Erasure began in early 2020 at the Debajehmujig Creation Centre in Manitowaning, Ont. Originally from Toronto, Satok now lives on Manitoulin Island. “From a white or settler

SIMONE DALTON

RBC Taylor Prize mentorship program

Simone Dalton, MFA ’18, was selected as one of five writers for the RBC Taylor Prize emerging writers mentorship program. She’s currently writing a memoir.

GUELPH CLASSICS SOCIETY

Canta

The Guelph Classics Society, consisting of U of G undergraduate students enthusiastic about ancient literature, art, history and languages, launched the student-led, peer-reviewed journal Canta/ἄειδε: A Journal of Classical Studies. The first edition appeared in early 2020.

BRITTANY LUBY

Encounter

History professor Brittany Luby’s Encounter, a children’s storybook, was shortlisted for the first annual Sheila Barry Best Picturebook of the Year Award, worth $2,500.