7 minute read

Language of Music

by MADELEINE PARSELL photography by EMILY KARCHER

Over the course of her life thus far, 82 years to be exact, Ann Mayo Muir has taken the hand of inspiration countless times and developed an impressive musical portfolio. In addition to her work with The Highwaymen and, more prominently, the Maine-based folk musician and songwriter Gordon Bok, Muir has studied under acclaimed traditional fiddlers Alasdair Fraser and Martin Hayes. Throughout her career, Muir’s talent has been guided by intuition and an unwavering ear for just the right sound.

Advertisement

Arguably, both intuition and a good ear came in handy when Muir encountered Bok while she earned her stay at a ski lodge in Vermont by singing. An enthusiastic member of the audience led her to a neighboring A-frame to hear Bok sing for the lodge’s diners. She responded by sitting on the floor in front of the stage as patrons finished their meal. The two of them subsequently discussed music for hours in a small kitchen off the stage, and the rest is history, as they say.

Under Bok’s tutelage, Muir learned about folk music, which she had not particularly listened to previously. She had already discovered the chords she loved, most of which were not commonly used in folk music. While working together, Bok encouraged Muir to sing more like him—softly, with her eyes closed, and allowing the words to gently blend together—a method that did not stick.

While Bok would sing softly to pull the audience in, Muir strived to sing with clarity for those in the very back of the room to hear. “I thought about the people in the back row . . . I wanted them to hear the words, because I liked the words,” she recalls. She also had a strong tendency to enunciate each word, having grown up with a nearly deaf father. Although Bok and Muir differed in many ways, their voices blended beautifully for almost 40 years, 27 of

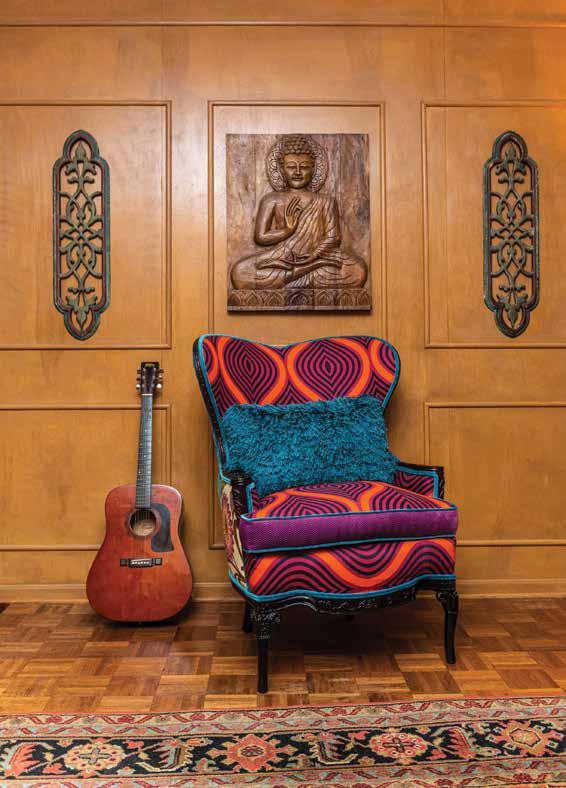

Muir in her kitchen. which were spent working in a trio that included Ed Trickett. They toured throughout the United States twice a year to places where folk music had an audience, visiting colleges, churches, festivals, and homes. This continued even when Muir relocated from Annapolis to France with her second husband. Bok, Muir, and Trickett created 11 albums starting with Turning Toward the Morning, released in 1975 and ending with Harbors of Home in 1998. Muir, Bok, and Trickett toured a final time together in 2000. The trio was forced to part ways when an age-related hormonal shift occurred that prohibited Muir from reaching the same vocal range. Up until this point, Muir had never written her own music, even though she recorded an album in the early 1960s called The Magic of Mayo Muir. Over the years, the trio performed a diverse array of folk songs ranging from lesser known pieces unearthed by research to songs written by Bok and other contemporary folk musicians. For years, this suited Muir, who found each composition uniquely compelling. When the trio dispersed, Muir learned to work alone, which presented its own challenges. Until then, she had not seen herself capable of creating her own music. She recalls having so many words and melodies floating through her mind that she feared someone else’s work would come out instead of her own. “Then I realized it was impossible, of course that couldn’t happen,” she says. When inspiration offered her its hand, she took it and found something she did not know was there waiting to be shared—her own words. Muir has found inspiration for her songs in conversations and musings “I love getting a phrase,” Muir states. She will hear something and think, “There is a song in that one.”

Muir plays one of her lifelong favorite tunes, "How are Things in Glocca Morra?" on the nyckelharpa.

While studying fiddle, one of her teachers told her that he had a notebook of unfinished phrases he had yet to complete. This inspired Muir to charge ahead and write full pieces. She has completed a significant amount of compositions, which she attributes in part to a willingness to forge ahead, make mistakes, and not be afraid to make changes. She consistently works through the challenges as they arise. She did just that while creating her latest album, Notes from Across the Sea, performed and recorded by Ensemble Galilei in 2009. “It was something I never dreamed I would do, or thought I could do, because I don’t write [or read] music [notation]. I play everything by ear,” says Muir. She has learned an impressive array of instruments over the years, starting with her beloved baritone ukulele. She taught herself to play around the age of eight by memorizing how each chord looked in the pictures of her music book. Other than the fiddle, which she learned through one-on-one instruction,

Muir learned to play instruments by ear and memorizing how hands moved over the strings or the keys. Most fondly, Muir remembers learning to play the harp. “I built [the music] chord by chord. I found the chord that matched what I wanted to hear,” she explains. Muir likens learning to play the harp to architecture, putting the pieces together the way one builds a house, with the floor, the walls, the ceiling. Playing each instrument yielded a sense of personal creation as she discovered the chords that produced the sounds that she sought.

In Notes from Across the Sea, Muir wrote music for four instruments, the harmonies of which were picked up and woven into a musical tapestry featuring nine instruments throughout the album. When Muir discovered Sibelius Software®, a program used to compose music, she found her awaking; she could hear each note as she placed it on the staff. After arranging each measure, she would ask the music where to go next. “And [the music] told me . . . so I just kept going and every time I ran out, I’d ask again,” she says.

As Muir listened to each song, she found a language in the music, built of questions and replies. While some notes needed to be longer or shorter, each element provided an important piece to the conversation of the song. To Muir, it was obvious—the music was speaking to her, and she understood every word. In this fashion, she constructed an album of 13 songs in which the creative talent of Ensemble Galilei was given the freedom to build on Muir’s melodies. Believing in the music is a part of Muir’s creative process. When recording songs with vocals, she navigates with her instincts rather than with a plan. “I hit ‘record’ and sing my song as if it already [exists]. The words tell me the music every time,” she says. Muir has a long relationship with music built on trust and faith; they have an open dialogue that exists only in intimate relationships. From Muir’s perspective, “People miss the music they haven’t been doing.” Muir enjoys a Sunday afternoon playing and singing old favorites on her baritone ukulele.

Perhaps a bit conspiratorial, Muir endeavors to stir things up wherever she goes. She inquires among strangers, “What instruments do you play?” and “What would you like to play?” The point is simple, to inspire others to play music and experience what Muir believes to be true. Music is a universal voice for those willing to converse with it, and it is never too late to learn the language of music. █

For more information, visit www.annmayomuir.com.

Muir in her sunlit kitchen overlooking Spa Creek in Annapolis.

MARYLAND FEDERATION OF ART MUCH MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE

Winter Member Show Jan 5 - Jan 21 Reception: Jan 1 4 Apr 2 - May 2 Reception: Apr 9 Art on Paper Spring Show May 6 - 30 Reception: May 1 7

Paint Annapolis June 7 - 1 4 20th Annual Plein Air Competition

art by Matthew Barber Kennedy, Paint Annapolis 2018 1 8 State Circle, Annapolis MD 21 401 | 41 0.268.4566 WWW.MDFEDART.ORG