12 minute read

Center for Oral Biology Update

Saliva, essential for oral health, is critical for maintaining oral homeostasis and serves multiple functions, including lubrication, digestion, protection of oral and dental tissues, and host defense.

However, a variety of conditions can cause major disruptions in function, including normal aging and drug interactions, as well as systemic diseases, such as diabetes. The most common disease involving the salivary glands is Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease affecting up to 4 million Americans, mostly middle-aged women.

Furthermore, an estimated 52,000 people each year are diagnosed with head and neck cancers and are treated with radiation. This therapy often results in permanent damage to the salivary glands due to irreversible loss of the secretory acinar cells. The long-term outcome is a significant decrease in salivary flow, known as xerostomia.

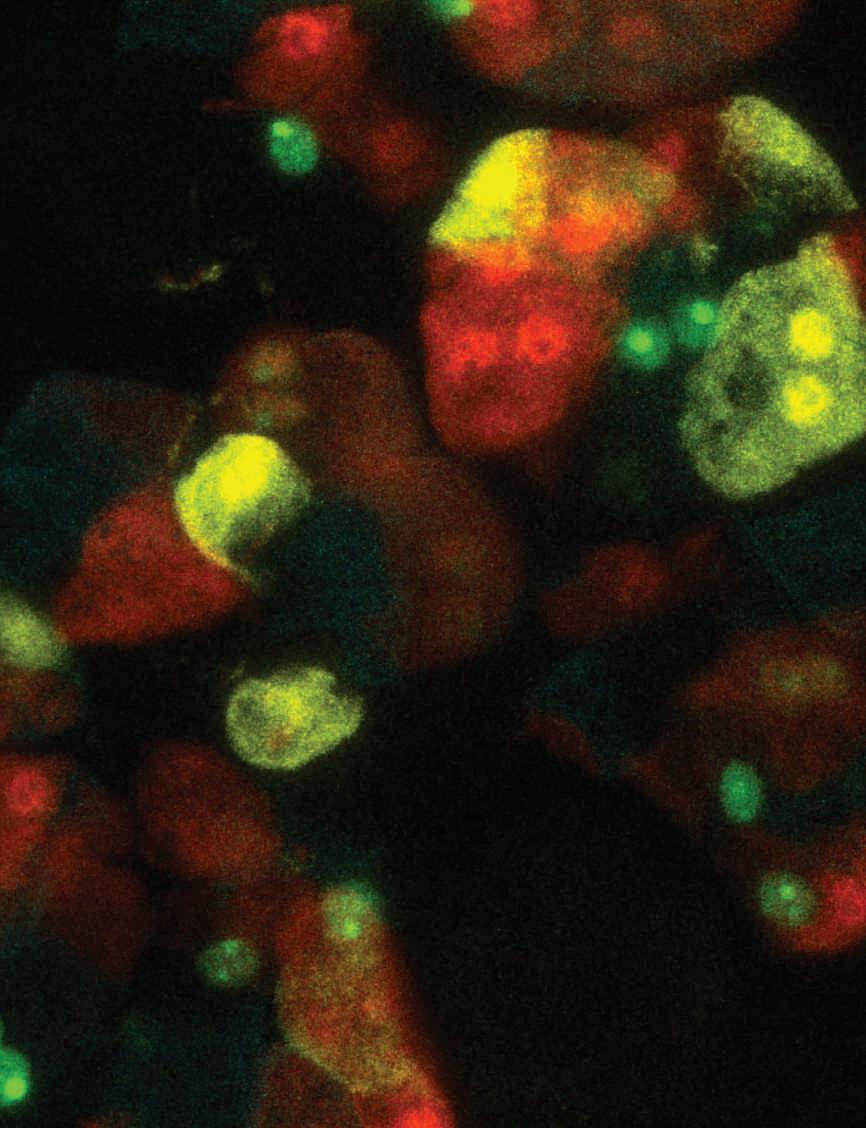

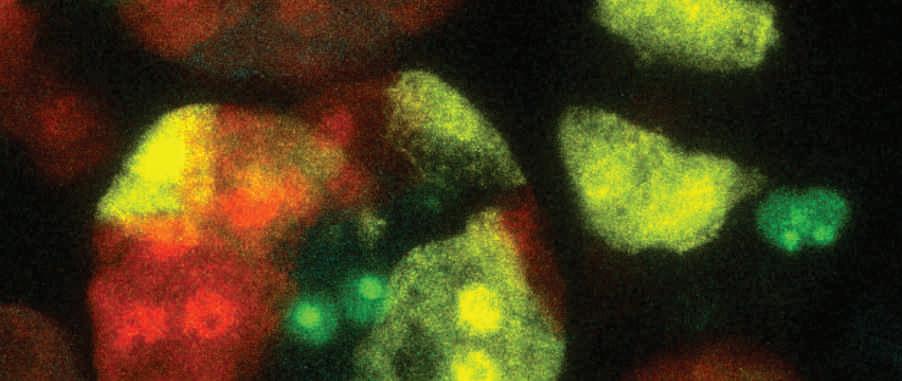

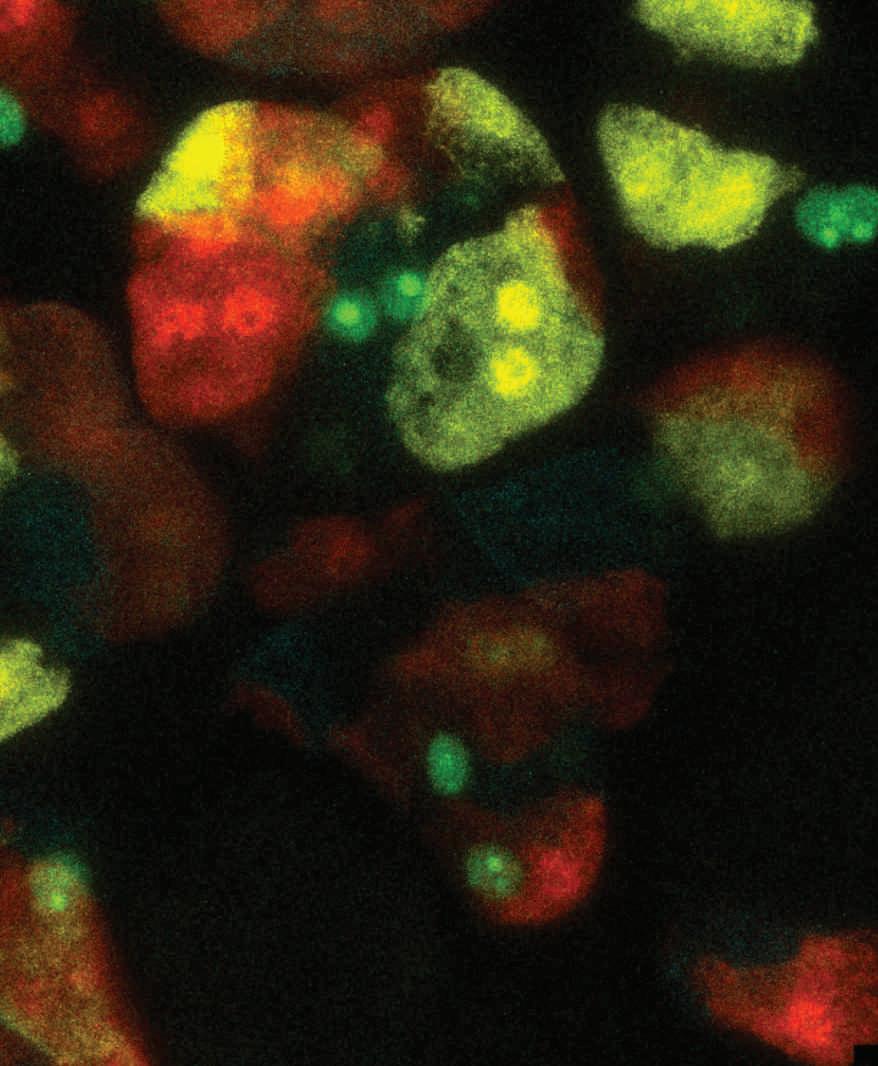

Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), small molecules that can be introduced into the salivary gland cells, to block the process of cell death from being activated by the

radiation treatment. (photo by Marit Aure)

Dr. Catherine Ovitt discusses the research findings with AEGD resident and postdoctoral fellow Szilvia Arany, DMD, PhD.

“Currently available treatments are temporary and do not result in repair of the glands. The availability of stem or progenitor cells would open the way for cellbased regenerative approaches,” explained Catherine Ovitt, Ph.D., Center for Oral Biology scientist and associate professor in the department of Biomedical Genetics. To address these issues, Ovitt and her team have three projects underway involving both molecular and cellular approaches to protect or restore salivary gland function.

One project involves treating the salivary gland in mice before radiation exposure, in an attempt to block cell death, which is the process that is initiated by radiation. The resulting loss of sensitive secretory cells leads to a decline in salivary gland function. Supported by National Institutes for Dental and Craniofacial Research, this project showed initial success and was published recently in Molecular Therapy.

Ovitt and her colleagues used short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), small molecules that can be introduced into the salivary gland cells, to block the process of cell death from being activated by the radiation treatment. “Two issues were paramount for success,” Ovitt explained. “One was efficient delivery into the cells and the second was to specifically block the cell death process.” In order to carry the siRNAs into the salivary gland cells, they coupled the siRNAs to nanoparticles developed in the laboratory of Danielle Benoit, Ph.D., assistant professor in Biomedical Engineering. The siRNAnanoparticle complexes were retroductally injected into the mouse salivary gland excretory ducts by Szilvia Arany, Ph.D. The mice were then treated with radiation.

They soon determined that the siRNAs hit their mark, greatly reducing the amount of cell death that took place after radiation treatment. Not only did the siRNAs protect

Dr. Ovitt is surrounded by members of her laboratory. Pei-Lun Weng, Marit Aure, Szilvia Arany, Andrew Shubin, Catherine Ovitt, Seo-Kyoung Hwang, Eri Maruyama. Seated (l to r) Mridula Vinjamuri and Mireya Gonzalez-Begne. (not pictured – Michael Rogers)

the cells from radiation damage, but they also preserved their secretory function. After three months, the treated mice had 50 percent more salivary flow than irradiated mice that were not pre-treated with siRNAs.

“Our results suggest that this approach could be an effective means of protecting salivary glands during radiation treatment of head and neck cancer patients,” Ovitt said. She also pointed out that the approach has significant advantages over alternative methods. First, the treatment can be limited to the salivary glands, so it should not affect genes in other tissues.

Second, in contrast to many gene therapy strategies, this technique does not involve the use of viruses. And finally, siRNAs are very short-lived, producing only temporary changes in gene expression. Investigations of the method are continuing, to order to determine whether the siRNA-nanoparticle complexes are effective with fractionated radiation treatments, such as are administered to human patients.

Another project in Ovitt’s lab is to identify and characterize stem or progenitor cells in the salivary glands, with the goal of harnessing those cells for repairing damaged or diseased glands. Maintenance of the salivary glands requires continued generation of new cells over time, but the source of these cells is unknown. “Understanding how the salivary glands are normally maintained to replace aging cells in the glands of adults is essential in order to design cell-based repair therapies,” Ovitt said. “Using mouse models in which we can study regeneration, we have focused on the role of two potential cell populations in the adult salivary gland.”

They are currently testing the ability of these individual cell types to contribute to regeneration of a gland damaged by radiation.

Regenerating Salivary Glands After Irradiation

The third area of focus is the application of bioengineered materials, such as hydrogels, in strategies developed for the regeneration of salivary glands damaged by radiation treatments for head and neck cancers.

“Several critical obstacles must be resolved before cell-based therapy for dysfunctional salivary glands can be moved into the clinical arena,” Ovitt said. “These include the identification of appropriate donor cells, the technology for promoting implantation into the gland, and direct functional assays to assess the outcomes.”

Members of Ovitt’s lab are using the powerful and well-defined genetic tools available in mice for tracing cell lineages, and defining important cell types. In collaboration with Benoit’s lab, they are testing the use of tunable hydrogel scaffolds for the introduction of those cells into damaged irradiated glands.

“The hydrogels can be synthetically modified to include environmental and cellular cues required for cell differentiation in vitro and in vivo,” she added. “The goal is to determine if the use of hydrogels can protect transplanted progenitor cells and promote regeneration of damaged salivary glands.”

The most often cited approach for treating salivary gland dysfunction caused by radiation therapy is the transplantation of stem cells, but many critical questions still need to be addressed, including what cells would work best, how to protect the cells once they are transplanted, and whether they can actually regenerate a functional gland.

“Although it is clear that experiments in mice are a long way from treating patients with xerostomia, our work with mice helps us to address these important questions,” Ovitt added. “Only by resolving these critical issues, can we progress toward repairing damaged salivary glands in patients who have undergone radiation therapy.”

Joel Brodsky, DDS, MS (Ortho ’76, MS ’81)

Momentum recently caught up with Joel Brodsky, who recently vacationed in China and stopped by to say hello to fellow alum Walter Li (Ortho ’79, MS ‘80). Since he graduated from the Ortho program in 1976, Joel Brodsky has been in private practice in Lakewood, California, where his son Charles joined him in 2005. Brodsky says he has had the pleasure of treating as many as three generations of area families, and the relationships he’s developed has been by far the most rewarding part of his job.

Q. Why did you choose Eastman

for your residency?

A. While at UCLA I was mentored by Dr. Lawrence Furstman, who was one of the first trained orthodontists in Beverly Hills. He had graduated from Illinois under Dr. Brodie a number of years before Dr. Subtelny. He told me I should go to Rochester as they had the best program! I was very fortunate to have Dr. Subtelny accept me.

I decided to get my master’s degree from the U of R. I had kept procrastinating writing my thesis. In late 1979, Dr. Johanssen, chair of the Dental Research Department, told me that I had until June 1980 to finish my thesis or forget it. With the help of Dr. Subtelny and Dr. Gilda, I defended my thesis in May 1980 and finally received my master’s. used our data for her published research project. I taught at UCLA for eight years and did research there as well. My son and I devote time to several cleft palate teams in Southern California.

Q. What are you doing now? A. I am working full time in my private practice with my son Charles and still loving the field. I feel orthodontics is THE greatest profession in the world! I lecture on 3D imaging as we have had an ICat in the office for six years. We provide 3D services for specialists and general dentists, and we boast one of the largest patient databases of Dicom data. Our data has been used by university programs and we were lucky to host EDC graduate Dr. Jenny Haskell who Q. What are some of your favorite

memories of the program and Rochester?

A. Dr. Gilda's kindness and his wax bone carving and anatomy classes. Dr. Subtelny's Hot Seat (really!) and time in the clinic, which really set the stage for developing our thought processes. Dr. Gugino's clinic days teaching us the "Rickett's" philosophy of treatment. Dr. Carl Musgrave's bread and butter techniques that I still use today. And finally, the Cleft Palate staffing days when we prepared x-rays, photos and models on our cleft palate patients and then went over progress and treatment plans for them. Cleft palate and surgical cases are a large part of our practice today...probably a great legacy and tribute to Dr. Subtelny.

Favorite memories of Rochester include Don and Bob's hamburgers and ice cream, trips to the apple cider mill, sailing on Lake Ontario with Dr. Robert Rosenblum and of course the fall colors.

Q. Tell me about your visit

with Dr. Li – were you friends at Eastman?

A. Dr. Li was actually two years behind me so our clinical training never overlapped. However, I met him when he interviewed and we instantly hit it off. He visited after graduation and I promised that he would be the first person I saw when I visited Hong Kong. Fast forward 35 years…I contacted Dr. Li and told him I was finally coming. What we found was an instant camaraderie and an amazingly warm, kind, giving, and engaging individual. He introduced us to that part of the world and showed us Hong Kong and the pride and love he has for it. Dr. Joel Brodsky with Dr. Walter Li and his wife Edie at the Luk Yu Tea House in Hong Kong.

Q. When you see other friends

from Eastman – do you always reminisce, or is that chapter closed?

A. I was very fortunate to make some long lasting friendships at Eastman. Dr. Bruce Haskell is one of my closest friends. He and his wife Joy lived across the hall from us at the old apartment building at the EDC on Main Street. We have celebrated life’s milestones together and look forward to participating in the same Angle chapter and the AAO. Dr. Bob Bray was my big brother and we enjoy a close bond. He and his wife lived in the apartment below us. Dr. Marshall Deeney was my little brother and I remember him with great fondness as does everyone at Eastman. What a terrible loss. Dr. Cyril Meyerowitz lived downstairs as well and was doing his GPR. We were friends and I was convinced he was headed for greatness. And yes, we still reminisce...

Welcome New Board Members

Bruce Tandy, DMD

Bruce Tandy first learned about Eastman Dental when he observed patient treatment as a biology major at the UR in the early 1970’s, and in 1978 when he applied to the GPR program. Fast forward to Meliora weekend a few years ago, when he took an Eastman Dental tour.

“Bill Calnon, who I knew from the ADA, explained the future goals and strategies to me and I thought it sounded interesting and in line with some of my organized dental pursuits,” Tandy said. “The combination of grad education, research, and community health will be important to the future of the profession as a whole and EIOH may help lead the way.”

Tandy is no stranger to community service. He has served on the American Dental Association’s Communications Council, Smile Health Advisory and Strategic Planning committees. Tandy has also been very active with the Connecticut State Dental Association, YMCA and the Vernon Jaycees. Closest to his heart, perhaps, is helping the underserved. For the past seven years, Tandy has been working with the local and national branches of Mission of Mercy.

“I love working and coordinating the huge group of people necessary to run these projects,” Tandy said. “But walking the line before the project opens and meeting the people who are seeking care is the highlight for me. This is the purist form of treatment I provide as a dentist – no business to run, just taking care of people in need.”

When not taking care of patients, Tandy, a self-described tech geek, plays golf, enjoys food and wine, and travels as much as possible. “But enjoying time with my wife and family makes all the work worthwhile.”

Bruce Tandy, DMD

Michael David Grassi, DDS, MDS

“It was an honor to be nominated and selected to be on the Foundation Board,” said Grassi, who has been involved with the UR for more than 20 years, first lecturing in the late 80’s and then as Section Head of Endodontics at UR School of Medicine and Dentistry since 1990. “The EDC Board has been active and involved with our community and I look forward to participating,” said Grassi, a Rochester, N.Y. native and active community servant, both within and outside the dental profession. “Serving on the Board will allow me the vehicle to continue to reach out, not only to my professional peers, but also to all people in the surrounding community. I look forward to assisting Eastman in its decision making for the next several years.”

A teacher at heart, Grassi taught swimming and diving lessons in high school and college, and also became a teacher’s assistant. “I enjoy watching others learn and develop as individuals,” said Grassi , who believes it’s the responsibility of professionals to encourage and inspire others through example and mentoring. “Teaching serves to open minds of all ages to the place where their abilities, knowledge and outlook encompass a greater ability to serve.”

“My parents, my siblings, and my own personal family have grown up with the acknowledgement that we do not live in a vacuum and need to return some of ourselves to society,” Grassi added. In his free time, he enjoys reading, exercising and relaxing, but is usually spending time with his three sons and supporting their activities.

Michael David Grassi, DDS, MDS