19 minute read

2022 Tater Hill Open

Part 1: Paying better attention to changing conditions

by Bubba Goodman

:The 2022 race was the 17th Tater Hill Open that I have coordinated. I’ve been flying the region since the late 1970s and have banked hundreds of hours and thousands of flights. I know this place well, and I thought, for the most part, that the weather was predictable. Our competition safety records speak for themselves. Until 2022, we never had any deployments. However, just one day in a friendly competition changed everything about how I look at the weather and pilots’ attitudes toward unsafe conditions.

For the 2022 event, we had a great turnout, with over 60 registered pilots. The two practice days were incredible. On Friday, many lucky pilots got over ten grand, and the site was flyable all day. Saturday could have been better, but still, people flew late into the day.

Sunday morning, we had a pilot meeting at the LZ. By 9:30 a.m., we were running pilots up the hill. The mountain was ridge-soarable when we got there with a few early clouds. The forecast was for overdevelopment later, around 4 or 5 p.m., so the task committee came

The ideal conditions Tater Hill typically offers. Photo by Bubba Goodman.

up with a short task for both the open and sport classes. All turn points were in front and north, away from where the weather was supposed to be, with good LZs nearby.

The launch window opened at 11:45 a.m., and the start was 1:00 p.m. It was still blue over the back, but we had weak-looking clouds out front. As soon as a couple of pilots stuck, launching began quickly. A few bombed out, but, for the most part, everyone was staying up. It didn’t take long for it to OD toward Grandfather Mountain. This development is quite normal and routinely happens there first. We could see rain some distance away and convergence clouds behind launch, but out front, where the task was run, it was still clear.

There was talk on the radio of rain, but it was early, and pilots were happily running the task. However, as the rain to the south crept slowly toward us, I was getting more concerned and radioed to launch to ask what pilots up there saw. A couple saw rain behind launch to the north, so at 1:27 p.m. I stopped the task. As always at comps, when I stop the task, call the day, or can’t run a task, pilots will sometimes choose to launch or stay flying for a bit.

This day was no different. Some folks tried to get down as fast as possible, others took their time, and others stayed high and enjoyed some airtime. Behind launch, things were starting to build up, and pilots were having a hard time getting down. There were about 10 pilots up on launch, including a couple of hang gliders. We could see a big wall of dark clouds heading our way, so we were scrambling, trying to put things away.

I was helping hide the gliders when I looked over my shoulder and saw a paraglider pull up and launch. The gust front was rapidly heading up the back of the mountain, and by the time we loaded everyone in the two trucks, it was blowing 40+ over the back. We drove down in a hailstorm with pouring rain.

When we got to the LZ, most pilots were on the ground, but four were still in the air. Pilot #1 was having a great time surfing the storm, staying ahead of the gust front. Pilot #2 was trying to stay ahead and get down in a safe field. Pilot #3 had disappeared in the clouds, and folks on the ground were trying to help him by radio. Nobody knew who Pilot #4 was.

The first three pilots all landed in the same field some miles away. Pilot #1 had a great flight by staying in front of the storm, whereas Pilot #2 did not. He had tried many ways to come down, including B-line stalls—he was a little shaken by the experience. Pilot #3 flew through hail, snow, and rain and was coached from the ground on how to descend using advanced maneuvers. He, too, was shaken up by the experience.

What about Pilot #4? Around the same time the other pilots were landing, we received selfie pictures of a pilot on the ground in a big field with a reserve behind them. Only then did we realize who the pilot was. Looking at their tracklog, we saw they were up over 18,000 to 19,600 feet and finally threw their reserve to land safely.

So here were four pilots, all in the same air, having totally different flights. The first three were caught in the air, while the fourth pilot chose to launch despite the approaching wall of rain, thinking he would take a sled ride down. All of this happened in a very brief period as

Comp pilots safely retrieving Lucas Soler after forced landing by storm. Photo by Lucas Soler. The storm over Tater launch. Photo by Lucas Soler.

the weather shifted just as quickly. The weather in this area has changed in the last ten years. We can no longer count on what we think we know or our past experiences. Did the pressure of the comp come into play? Maybe. I had 60 pilots wanting to fly, and though the weather was iffy, it was nice and flyable for a short period. Additionally, the forecast for the rest of the week was not favorable, so we wanted to get a round in. In the end, pilots decided to fly even after I called the task, and a few chose not to launch. Most of the pilots had a fun flight and made the conservative decision to land early. Will I be a little more conservative next time? Yes. It was the first day of the comp, and it usually takes a day or two to figure out a few bugs in the system. We didn’t know who Pilot #4 was, and since they launched when and where they weren’t supposed to, nobody was watching. On top of that, they had no buddy to tell us who they were. We got very lucky on this day at Tater. The rest of the week was a wash, with only a few late afternoon soaring sessions after the winds backed down. Some folks went home, but others stayed to enjoy the fantastic weather; they went mountain biking, swimming, and hiking, and participated in clinics hosted by Kari Castle and Chris Grantham. We had a good turnout for the final dinner of the event; the food was great, thanks to Joe Koening. All six or seven hang glider pilots showed up and got some great swag from all the generous sponsors.

Many folks told me that despite the lack of flying, the meet was a success, and they had fun. For me, though, the disappointment of not flying and the precarity of the storm surfers weigh heavy. I’m always asked why I have so many rules at the comps, and this past comp made it clear why: I’ve had 17 years of watching pilots take advantage of or ignore the systems in place. Comps make some pilots do stupid things. It only takes one person to screw things up for everyone. No doubt, this year, I will be more cautious of conditions and keep better track of pilots.

I think it’s safe to say everyone at the comp learned something. I can only hope that the reality of how lucky a few pilots were is not lost on everyone. We all need to pay more attention to conditions, even if we think we know them well.

Part 2: Cloud Suck Really Sucks

by Tony Davis

:Day one of the 2022 Tater Hill Challenge in Boone, North Carolina, was shaping up to be completely uneventful. Pilots were launching but, with a few exceptions, were getting little altitude above launch. Some even bombed out and landed early. Bubba Goodman, the event coordinator, talked about ending the task and calling it a free fly day.

Based on the advice of a more experienced pilot, I was holding off on launching in hopes of more favorable conditions as the day progressed and the sun had time to do its thing. As this was my first competition and my first time flying at Tater Hill, I was attentive to what Bubba and the other event organizers had to say about conditions.

Though there was rain in sight much of the time, it was quite some distance away. I was told that this rain typically stays to the south of where we were flying, and though we needed to “keep an eye on it,” there should be little to no impact in our immediate area. Large overdevelopment is often held at bay by a ridge system and rarely becomes a concern for pilots flying at Tater Hill. And this prediction was accurate—until it wasn’t.

From launch, we could again see rain to the south, but it seemed far enough away to be of no consequence. The local experts kept an eye on things and eventually decided to cancel the day’s task but keep the site open for free flying. I decided to launch wearing only a thin shirt and no jacket, not something I usually do, expecting an uneventful sledder. I also did not have my inReach satellite device with me because I thought it would be a short ride down from launch to the LZ. From now on, however, I will always plan for an eventful flight, even if

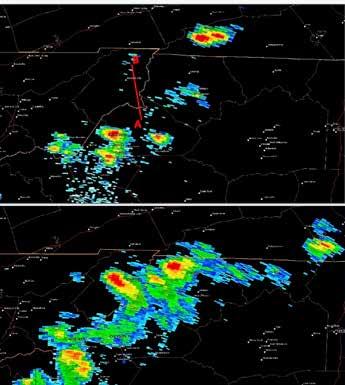

Radar image along Tony Davis's flight path from around 1:04 p.m. to 3:03 p.m.

-Marcel Proust

I expect a sledder.

I launched at 1:26 p.m. into smooth air, and, as luck would have it, I got a bit higher above the launch than expected. I gained altitude in mostly ridge lift as there was little thermic activity out front. This lack of lift away from the hill would soon change.

Once I reached about 500 feet above launch, I had a unique vantage point of the imposing weather and could see what others could not. Rain was approaching from the south, but ominous weather was also growing to the east; this eastern threat was likely not visible to the folks on the ground. I radioed what I was seeing and decided to head toward the LZ.

Over the LZ, I encountered light lift that allowed for some thermaling, but nothing seemed problematic. I had little reason to feel concerned about getting down quickly. However, things soon transformed. Conditions changed slowly at first, but when the change came, it seemed exponential rather than linear. The lift went from light to something you might long on a great XC flight, to something challenging to get down in, to, suddenly, something dangerous. The storm that caused this unexpected lift looked far away, but it had consequences for pilots over the LZ. Moving forward, I now have firsthand experience of how weather can impact you from further away than you might realize.

I made my one big mistake of the day before the dramatic change in conditions. Other, more experienced pilots on site agreed that most of my piloting decisions were sound, except for this one. When I first saw other pilots starting to descend using big ears, light spirals, and wingovers, I wrongly assumed I had plenty of time to get down, and I lingered in the air. I started using

Just after landing, looking north toward the still "friendly" skies. The sky was much more imposing to the south. Photo by Tony Davis.

Tony Davis on big ears trying to get down to the LZ before things got bad. Photo by Luke Higginbotham.

big ears initially, but when I got low, I decided to play around in the air a little longer. A few other pilots were flying around, and I felt safe lingering in the air too— this was a big mistake. I had seen the development from the air and had already decided not to continue flying, so I should have followed my plan and gotten down immediately. With little warning, the lift became stronger—it wasn’t sudden but grew consistently. Big ears alone were no longer effective. Eventually, I found all my movement was up, even with ears. I had recently completed my first SIV and had practiced spiral dives; I should have done one here while I still had the chance, but I hesitated. While continuing to try big ears and full-speed bar (which resulted in either going up slower or, at best, maintaining level flight), I could see the rain and a lot of wind approaching. It looked like things were going to get nasty soon. For the first time, at about 1:57 p.m., I felt like I needed to get down NOW! Unfortunately, the lift kicked in stronger, and I felt that nothing short of a full spiral dive would get me down.

Just as I decided to commit to the spiral and did a 360 to clear the airspace, I saw a lightning strike just past the LZ. I decided to turn and run. After making the mistake of not getting down when I could, the decision to run from the storm was my best option given the circumstances. For the first time on this flight, since reporting conditions after I launched, I made a radio call. I identified myself, said I was having trouble getting down, and was running from the storm.

Once I had just a bit of distance between me and the storm, I saw a likely alternate LZ below and decided to try the spiral one more time. Unfortunately, just as I was committing to the move, I was sucked into the

QUEEN 3 EN/LTF C QUEEN 3 EN/LTF C

Setting new standards once more Setting new standards once more

WE’RE THERE! Introducing the Triple Seven Queen 3, the EN C wing to let YOU fulfill your loftiest flying goals! WE’RE THERE! Introducing the Triple Seven Queen 3, the EN C wing to let YOU fulfill your loftiest flying goals!

While flying one, you will notice that the design team made the new wing even more While flying one, you will notice that the accessible and easy to fly; we think this one design team made the new wing even more really feels like an extension of your body accessible and easy to fly; we think this one and brain! really feels like an extension of your body and brain! The new Queen 3 – once again setting the standards in its class! The new Queen 3 – once again setting the standards in its class!

cloud. Pulling the G-forces associated with a spiral while simultaneously being sucked into a cloud was incredibly disorienting. I tried to come out of the spiral as I had learned, slowly bleeding off the energy, and went into level flight, using my instrument to head north toward Mountain City, Tennessee.

During most of this flight, I had the calm and reassuring voice of Richard McDermott, a paragliding instructor from St. Louis, speaking to me on the radio. It was comforting to hear someone telling me that I was doing the right things; keep running from the storm, keep heading north, and, for now, worry more about flying than getting down. For anyone on the ground in a situation such as this, I would recommend staying in radio contact with the pilot in a bad situation. Let them know they are not alone, provide coaching if needed and possible, but mostly, just “be there.”

Once in the cloud, all I could do was keep the wing overhead and pointed in a safe and consistent direction. I held a steady north heading, primarily because McDermott advised this direction on the radio as the storm was still advancing from the south. This information was crucial as I was new to the area. Though I know north from south, the initial advice I received to head toward Mountain City was lost on me. As a piece of advice, if you see you are about to enter a cloud, take a heading of the direction you want to go using your instrument or compass while you can still see. I had often heard how disorienting it can be to fly inside a cloud in whiteout conditions—I now have firsthand experience with how true this is. Several times, every sense in my body told me I was turning left (I don’t know why, but it was always left), but by looking at my compass, I could tell I was flying north. However, I found it difficult to reconcile the fact that to fly straight north (according to my ball compass), I had to do what felt like a moderate amount of weight shift and brake input to turn right. After coming out of the cloud at an elevation of around 8,400 feet, I witnessed one of the most beautiful vistas I have ever seen. I exited the cloud somewhere near the middle, looking down at a field of smaller cumulus clouds, with other cumulonimbus clouds around me and nothing but blue skies and wispy cirrus clouds above. It was breathtaking. I wish I could have relaxed and enjoyed it more, but such was not the case. There was more piloting to do. After leaving the cloud, I faced something of a dilemma. I could see the ground through small openings in the clouds below. It was dark down there and did not look like somewhere I wanted to be flying. As disconcerting as it was in my location, the ground below looked worse. There was another large cumulonimbus to my north, the direction I needed to fly. If time was of

The day started off normally, setting up for launch. Photo by Tony Davis.

no concern, I likely could have flown around the cloud. However, the occasional lightning flash and thunderclap reminded me that I needed to keep running north. I either had to take the time to avoid the next cloud and lose distance from the storm or intentionally fly back into the white room. I chose the white room. After about 40 minutes of flight, the air was getting smoother. Maintaining a north heading with minimal weight shift was more manageable, and things were starting to brighten up a bit. I was spending less time in clouds, and the ground below looked more inviting. At about 2:35 p.m., I finally cleared the clouds for the last time. While things were relatively calm and clear, the bad weather was still headed my way, so I knew I needed to get on the ground. I was finally losing altitude and found a little sink—unfortunately, there was nothing but trees below me. Since I needed to make it to an acceptable LZ, I came off big ears. Fortunately, releasing big ears was all I needed to clear the trees and easily make it to any of the several great landing spots directly in front of me.

I was now on a glide path to a nice LZ. At around 2:43 p.m., another voice came over the radio, my friend Andrew Copeland. Copeland reassured me that everything looked ok here but also that the approaching weather might be worse than I realized, including very high winds and a lot of rain. Copeland advised foregoing the gentle S-turns I was currently doing to bleed off altitude and do something a little more aggressive. A spiral with big ears was the recommendation. “Just pull big ears, pick a side, and fully commit with weight shift,” Copeland said. I did this, and it worked very well, even though I never did a full spiral, only moderately tight 360s.

THERE AND BACK…

Demos available: 801-699-1462 info@bgd-usa.com

I lost a lot of altitude very quickly—it was a smooth maneuver with minimal G-forces compared to a spiral dive. As an added benefit, I didn’t have to deal with all the excess energy I often experience when coming out of a spiral dive. At long last, I was finally on the ground.

I engaged in several conversations on rapid descent techniques following my experience. A couple of more experienced pilots suggested that the G-forces associated with spiraling down on less than your entire wing (on big ears, asymmetric, etc.) might put excessive stress on the lines still supporting your weight.

I was flying a BGD Base 2 paraglider, so I went to the source and asked Bruce Goldsmith if there were any concerns about spiraling down on big ears with this glider. He responded, “The problem with a high-G maneuver where not all lines are being used is the possibility of structural failure of the lines. All gliders are load tested to withstand 8G at max load. However, that

is with all the lines. If you remove some lines, the safety factor is also reduced. This is the reason why I advise not to do a spiral dive with an asymmetric collapse on production gliders.”

He admitted that he does not personally have experience with spirals with big ears but would look into it more as he does not know how high the G-forces are in this maneuver. I pointed out that the G-forces on the pilot seemed much lower spiraling down with big ears than with a normal spiral dive, and Bruce offered, “If the G-forces are low on the pilot, then the line loads will also be low. So, this maneuver is likely not to overstress the glider or lines.” As a final thought to this narrative, if I had immediately committed to a spiral dive or B-line stall when I first realized I needed to get down quickly, I likely would have landed at the LZ and avoided the day’s excitement—but I hesitated. I hesitated because I am not yet completely comfortable with these rapid descent techniques. Eventually, I tried both a spiral and a half-hearted B-line stall, but by that time, the cloud had veto authority. The bottom line: I need more practice. As they say, dig your well before you get thirsty.