67 minute read

Full Steamboat Ahead

from UV Spring 2021

by usflyer

Travel Awesomely

Guide Vern Nelson specializes in world-class adventures to roads less traveled around the world.

Advertisement

Story by Don Gilman Adventure Photos Provided by Vern Nelson

For Vern Nelson, the call of adventure began in the Calapooia Mountains outside Oakland. Experiencing the chilly creeks and verdant hills of southwest Oregon grew in Nelson the heart of a modern-day global explorer. “That was before we had iPads and iPhones, so we spent a lot of time running up the river, swimming,” Nelson recalls. When the river ran high, Nelson and friends ran it in an old, patched-up raft. “I completely should’ve died a couple of times, literally should’ve died a couple times,” Nelson says. “My childhood was great.” Meet the founder of Roseburg-based Big Life Adventures, a personalized guide service specializing in explorations both around the world and right next door. Nelson’s calling is leading unforgettable visits to places few have seen. That wasn’t always the plan. The original scenario involved Nelson earning an advanced degree then settling down, becoming a high school teacher, maybe getting married and leaving behind his youthful escapades. His lifelong love of adventure clearly was no passing fancy. But that was his plan, and it took a happenstance or two to get him fully back in the game. While Nelson was relaxing in the waters of Nat Soo Pah Hot Springs in southern Idaho, a group of international travelers appeared out of the dark to join him at the remote spot. When he learned that a guide working for Trek America had brought them there, a light went on. He recalls thinking, “I could probably do that job.” Then he promptly dropped that thought for a few months until he ran into another Trek America group while in Mexico. This time, he turned his thought into action, mailing the company an application. “I sent it in from the jungle I was in, with apologies for the mud stains it had on it,” Nelson says. “Surprisingly, they hired me.” Nelson stayed for a decade, spending the first four years as a guide and the next six as a training and recruiting manager. But as he worked for what was then the largest guided-tour company in the world, Nelson noticed potential clients longed for something more in their travels, something personal and meaningful — an experience uniquely theirs. Nelson’s next revelation, however, was nearly a tragedy. He had ridden his motorcycle to the tip of South America and was returning north to the Arctic when he had an accident in downtown Portland. Instead of continuing his trip north, Nelson wound up in Oregon Health & Science University hospital with broken ribs, a punctured lung, a broken scapula and spinal injuries. “I spent 10 days at OHSU and had a lot to think about, and just decided I wanted to get back into guiding,” he recalls. “I had a friend that started a company in Vegas, so I ran a few small trips for her in the summers and then, in 2015, I ran my first tour with my own company.” Under Nelson’s guidance, Big Life Adventures has thrived following roads seldom traveled. “That’s what my job is,” says Nelson. “That’s why people go on trips with me. They know I’m going to find the right people and I’m going to take them to places they couldn’t find with a Google search. Finding secret spots is a big part of my job.”

Vern Nelson photo by Thomas Boyd.

Giraffe sighting in Kenya. Group hike to Mt. Cook, New Zealand.

“People know I’m going to take them to places they couldn’t find with a Google search. Finding secret spots is a big part of my job.” — Vern Nelson

Umpqua Valley travelers Cheryl and Dan Yoder joined Nelson for an adventure in New Zealand in November 2017. “It was one of the most amazing trips I’ve ever been on,” Cheryl says. “Vern was such a knowledgeable host of information and places to see. It made the trip just perfect.” The Yoders have enjoyed throughhiking on the hut-to-hut system and sea-kayaking in fjords. They’ve hiked in to see a collapsing glacier and stunning waterfalls. And they aren’t finished. “Vern’s been trying to get us to do a couple more of his trips as the world opens up again,” Cheryl says. “He’s very knowledgeable and he’s just fun. He’s very entertaining.” Lem James, another Nelson client, says Big Life Adventures provides exactly what he wants out of a travel experience — more local knowledge and spontaneity. “Vern is at home around the world and enjoys showing his customers the most beautiful natural wonders from Alaska to Africa and beyond,” says James. Kevin Mathweg, a Big Life Adventures veteran traveler, endorses both international travel — when it becomes safe — and Nelson’s ability to provide experiences found nowhere else. “Whether you want to dirt bag it on a beach in Baja, relax in a secluded kayaking cabin in Alaska or live it up in a private retreat in New Zealand, Vern offers it all,” Mathweg says. Like many other businesses, Big Life Adventures was slammed by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially on international bookings. Nelson is hopeful 2021 is better for business. “This year’s a tough one,” Nelson says. “I’ve got a private tour planned for Alaska. Mongolia is supposed to happen in July. The Spanish Company (a hiking/vineyard trip) is supposed to happen in August. Another Spanish trip in September. I’m supposed to hire somebody to run a second Mongolia tour in September, if they happen. Who knows? I’m hoping for the best and planning for the worst.” That could be a tall order given Nelson’s clients seem to think he is only capable of planning for the best.

A glacial landing on Mt. Denali, Alaska.

DAIRY TALES

As Umpqua Dairy celebrates its 90th year in business, company owners and longtime employees look back on some of their most memorable moments.

Story by Dick Baltus

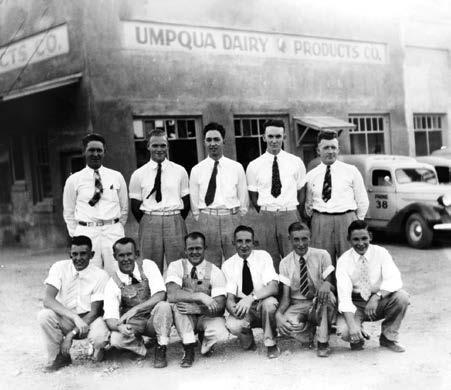

The early dairy delivery fleet. The dairy crew in 1939.

n a misty Friday morning, a door slides open on the side

Oof a refrigerated warehouse in Roseburg’s Mill-Pine district and through the heavy vinyl curtain emerges Doug Feldkamp in white lab coat and mask, clutching a fist full of envelopes. It’s payday at Umpqua Dairy, the semi-weekly ritual that gives the company CEO the chance to touch base with every employee while personally delivering their paycheck, an exercise he shares on occasion with his brother, Steve. “You know, we’ve grown so much it’s getting harder to remember everybody’s name,” says Feldkamp, whose father, Bob, led the company before him, succeeding his own father, Ormond, who co-founded the dairy with Herb Sullivan. This year marks Umpqua Dairy’s 90th year in business and Doug’s 33rd at its helm. When he took the reins of the company, the new boss only had to remember 88 names. Today there are more than 290 individuals on the payroll, and while Feldkamp can’t hand deliver checks to all of them (the dairy now has nearly 110 workers in its seven distribution centers outside of Roseburg), “being able to remember as many names as he does is pretty darn amazing,” says longtime employee Don Fisher. Neither Doug nor chief operating officer Steve ever thought they’d be celebrating Umpqua Dairy’s 90th anniversary from inside the organization. After graduating from Oregon State, Doug was working as an auditor (“and basically being a ski bum”) at Mt. Bachelor Village in Bend when in 1985 he decided to move back closer to family. Steve, also an OSU graduate, was working as a marine biologist in California but decided to return home to the family business when the Feldkamp’s father was diagnosed with cancer. “We’d worked in the dairy during summers, but neither of us felt we’d come back after college,” Doug says. Plans change, as do businesses that last 90 years. We asked the Feldkamps to share some of the most memorable events in Umpqua Dairy’s history before and during their tenure with the company.

THE FIRST DELIVERY

Umpqua Dairy’s first milk delivery in 1931 went to “Mrs. Parrott” who, the Feldkamps surmise, was Rosa Parrott, a local legend whose historic home has been transformed into a restaurant.

In 1931, dairy employees would deliver ice cream via a donkey team to the train station and sell to railroad workers.

THE BIG BLAZE

In 1974, a major fire devastated the dairy, temporarily shutting it down completely. “It was January and I was playing in the band at a Roseburg High basketball game,” recalls Steve. “An announcement came over the P.A. system ‘Would Bob Feldkamp please report to the office?’ Then they asked all dairy employees to report to the office. Somebody ran up to me and said, ‘Hey, the dairy’s on fire.’ We ran outside and the whole sky over here was orange.” Adds Doug: “It was just before my 15 birthday, and I had been looking at this Suzuki motorcycle and was hoping I’d get it as a gift. I remember walking down the sidewalk with Steve looking at that fire and him saying to me, ‘Well, you can kiss that motorcycle goodbye.’ Scarred me for life.” “I don’t remember saying that,” Steve counters. “But I probably did.” Other Oregon dairies lent the use of their plants so Umpqua could continue producing until the local facility was usable again.

YOU CAN GO HOME AGAIN

Doug returned to Roseburg and the family business in 1985; Steve followed in 1988, the year Bob Feldkamp lost his battle with cancer. In the 18 months before and after his death, the dairy lost about 250 years of experience through the deaths or retirements of other long-term employees. At the time, Doug was just 28. Steve was only 31, “and neither of us knew anything about the business,” Doug says. They were quick studies.

— STEVE FELDKAMP

A dairy representative with customer in 1967.

DAIRY GROWTH

After operating exclusively in Douglas County for its first 40 years, Umpqua Dairy expanded into Grants Pass and Coos Bay in 1969. The dairy would build a distribution center in Grants Pass in 1978 then begin expansion into Medford. In 1990, another distribution center was built in Coos Bay followed by centers in Portland and Klamath Falls in 1994, Eugene in 1999, Central Point in 2006 and Springfield in 2019.

ON WORKING TOGETHER

“We’ve had our moments,” says Steve, wryly. “Some of those moments have lasted years.” “I think it helps that we’re from completely different backgrounds,” Doug says. “Steve hasn’t been a marine biologist for 30 years, but he’s still a scientist. And my background is business, so we don’t think the same way about a lot of things. Which I know has driven employees crazy when they are right in the middle of us. But we complement each other.” “There’s a lot of common ground,” Steve adds. “We trust each other.”

Bob Feldkamp (L) with 4H kids at the Douglas County Fair.

Steve and Doug Feldkamp photo by Thomas Boyd.

QUALITY FIRST

Umpqua Dairy has won multiple quality awards for its products and in 1998 won the Irving B. Weber Distinguished Award for Excellence, the Quality Chek’d organization’s most prestigious recognition. “Our team realizes we don’t have to be biggest to be best,” Doug says. “You can be best by just caring about what you are doing and having pride in it.” “I think having long-term relationships makes all the difference, whether it’s customers or employees,” Steve adds. “We have a lot of long-term employees who have kept our culture of excellence alive through the years.”

he following is excerpted from our conversation with

Tlongtime employees John Harvey, director of plant operations (39 years); Ray Duncan, director of logistics and inventory (31 years); Jesse Brannon, purchasing supervisor (33 years); Karen Buswell, human resources specialist/ payroll (41 years); Patty Beamer, executive assistant (30 years) and Don Fisher, night-time plant supervisor (43 years). Jesse: “I started in the cooler. There was one chain, and it went in a tiny circle. The product came out and we loaded it onto trucks. Sometimes we had to load the entire truck with a hand truck.” Ray: “We only had a couple routes because we only had depots in Grants Pass and Coos Bay.” John: “I was supposed to be here for just for two weeks. That was 1982, when there were no jobs. I didn’t even ask the wage. I didn’t know how much I got paid until I got my paycheck. I was just putting milk in crates. They came off the filler on a little turntable and you just put them in the crate as fast as you could, then grabbed another crate.” Ray: “When we ran out of milk crates, we’d have to drive around to all the stores, or houses, and bring back the empties.” John: “We didn’t like people stealing our crates, because you had to run till you were done. So you’d have to stop and run around and get more cases before you could finish your job.” Patty: “That’s still a problem today.” John: “I got a text just today from my son proudly telling me he confiscated a milk crate from one of his co-workers.” Karen: “I remember we took some back from somebody who had pretty much furnished their whole house in our milk crates.” Jesse: “We’ve seen them in fishing magazines, in dorm rooms at the U of O; even saw one on a crab boat on Deadliest Catch.” Don: “So, I’ll tell a story about my brother (Ron, who recently retired after a long career at the dairy). I don’t know the year, but it was in the 80s when we were doing home delivery. Ron liked to rush things, and sometimes he might forget to set a brake or

Karol Orth was a student at Roseburg High when one of her teachers recommended her for a job at Umpqua Dairy. She’s now in her 57th year with the company. She was the first employee to learn how to work on a computer and in her time has “done a little bit of everything.” She’s still going strong at 75. “I’m not ready to retire,” she says. “I don’t want to stay home, and I like my paycheck.”

— JESSE BRANNON, PURCHASING SUPERVISOR

Ray Duncan (31 years).

something. He was delivering five half gallons of 2% up on a hill in town. After he drops them at the house and starts walking down the steps, he notices his truck rolling down the hill toward a house. It ran into a wall that got pushed right into the headboard in this couple’s bedroom. He goes and knocks on door. The owner gets up — well, he was already up — answers the door and says, ‘You didn’t need to knock.’” John: “We used to have a full-size plastic cow…” Jesse: “Oh, you’re going to tell that story?” John: “…a plastic Holstein we kept in a storage area. One day I went by there and there was some kind of chocolate substance on the floor behind it. Steaming. That was funny right there.” Patty: “Who was it that got locked in the freezer?” Karen: “We used to get ice cream fresh out of the spout. One gal decided she wanted to make a sundae with some of the chocolate marble that we used to put in the ice cream. She went into the trailer and the door shut and locked behind her. She panicked a little but they got her out quick.” Jesse: “In the old days, you’d put on a hair net and run into the ice cream room and they’d put a container under the spout and get you a tub of ice cream, whatever you wanted depending on what they were running.” On the dairy’s commitment to quality…. Jesse: “It comes from the top down. It’s ingrained in the culture.” Patty: “John always says, ‘We don’t win every contest, but we expect to,’”

We are pleased to share a small selection of the impressive portfolio of contributing UV photographer Robin Loznak. The former chief photographer for The News-Review in Roseburg, Loznak currently is a contract photographer with the international editorial photo agency ZUMApress. His work is published regularly regionally and around the world. A photojournalist by training, Loznak began concentrating on nature photography while working for a newspaper in Montana, near Glacier National Park. More recently, with pandemic restrictions cutting into his assignments and leading to “a trunk load of gear gathering dust,” he redoubled his effort to photograph the wildlife and nature within miles of the home near Elkton he shares with his wife, three dogs, three cats and chickens. “I set the goal of capturing at least one image worth sharing every day on social media and though ZUMApress,” Loznak says, adding that he’s only missed a few days. “Seeing your amazing photos pretty much every day has provided major sustenance for me through this challenging time,” wrote one of his blog readers. Enjoy.

Smoke from last September’s wildfires tints the sun a vivid color leaving a vulture silhouetted on its perch.

A wild garter snake captures and works on consuming a bullfrog on the bank of the Umpqua River. According to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, garter snakes are known to eat frogs, toads, salamanders, birds, fish, reptiles and small mammals.

A Steller’s jay snatches a walnut from the roof of a shed..

After the Fire

Last September the Archie Creek burned thousands of acres and destroyed treasured recreation sites and scores of homes, sending an array of public and private stakeholders in search of the best route to recovery.

Story by Jennifer Grafiada Photos by Robin Loznak

Labor Day weekend of 2020 unfolded like many before in Douglas County, with residents and visitors enjoying the dozens of miles of fern-fringed, family-friendly trails that lie east of Roseburg along the North Umpqua Highway (Oregon Highway 138). Favorite spots such as Susan Creek Falls, Toketee Falls and Fall Creek Falls were busy with a variety of folks taking in the last days of summer. Couples walked their dogs. Parents did their best to keep up with energetic children delighting in nature. Silver-haired retirees with binoculars took in the spectacular diversity of trees and wildlife. People gathered to skip rocks, take selfies and relax with picnics. A bride and groom said their vows under a waterfall then gamely navigated the dirt and rocks back to the trailhead in their wedding attire. Few of those trail-goers could have imagined that late on Labor Day and early the following morning a terrible concoction of high temperatures, low humidity and strong winds would mix with existing wildfires in the Umpqua National Forest to set the scene for an explosive inferno that would destroy treasured trails and recreation sites, more than 100 homes and more than 130,000 acres of Douglas County forestland. While some green tendrils are beginning to poke through the black in the months after the Archie Creek fire, it’s hard to fathom how much time will pass before the landscape is restored to what it once was. As landowners and public agencies reckon with the damage and work through forest recovery plans, it provides an important window into what it means to create resilient forests in Douglas County and the Pacific Northwest in a changing world.

Rick Sohn has spent his life immersed in the woods. His late father, Fred, founded Sun Studs and later Lone Rock Resources, where Rick spent decades before retiring as CEO and turning his focus to forest management. Sohn holds a master’s degree in tree physiology and a PhD in forest pathology and mycorrhizae with a minor in soils. He is passionate about silviculture, reforestation and timber and, in 2015, helped found Forest Bridges, a non-profit that seeks a collaborative approach to modern forestry practices across the more than 2 million acres of public land in southwestern Oregon. Sohn has been paying attention to what the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) plans to do in terms of fire recovery and shares his concerns. “I believe the intensity with which they are logging 6,300 acres, while leaving 25,000 acres without any planned recovery effort, as I understand it, begs a lot of questions,” he says. “In the checkerboard ownership, where fire has been excluded for 100 years and humans are part of the equation, there really needs to be a new look at how we manage these lands.”

Serious logging is already under way on many private land holdings, which represent almost half of the Archie Creek Fire’s affected acres. Paul Beck is the CEO of Mountain Western Log Scaling and Grading Bureau, a business that provides services to timber companies like Roseburg Forest Products and Seneca Jones Timber Company. Beck believes that the BLM and U.S. Forest

Service, bogged down by regulations and bureaucracy, will waste an opportunity to not only save merchantable timber, but also to create a healthier habitat that will be more fire-resilient in years to come. “The clock is ticking,” Beck explains. “If that wood is not green and growing, it is dead and rotting. It will lose half of its value in a matter of months. It is nice and wet out there now, but as soon as the spring sunshine hits that wood and it starts drying out, the fungus will get to working in there and then it deteriorates and splits and it won’t be of any value. It won’t pay for the rehabilitation work that needs to be done. And if they don’t remove the trees that are out there, it won’t be long before it’s unsafe to get under there with planting crews because, as the trees rot, they lose limbs that fall down and land on tree-planting crews.” Beck recounts hearing the media repeat a line equating salvaging an area of burned forest to mugging a burn victim. “I would say just the opposite,” he explains. “Not restoring these forests – and salvage is only the first step – is like a doctor refusing to treat a burn victim. We are smart enough to do salvage in a kinder and gentler way than my grandfather would have done it.” While fire has always been a natural part of the forest cycle in the Pacific Northwest, human presence creates a more complex picture. Forestry in large part replaces fire as the mechanism to remove the fuel load from timber-rich areas, which does have economic benefits for those logging and selling the timber. How much one should remove, even following a fire, continues to be a matter of debate. “We can argue over salvage, and we have a lot over the past 30 years, but the truth is we need to manage these lands so the fires don’t happen, or they are not as big,” Beck continues. “We have seen fires in the past, like the Tillamook fires in the early part of last century. They are big fires, but they are nothing like what we are seeing today. Spots that we thought were at no risk of fire are all black and brown. There isn’t a green tree out there; it’s all dead.”

Beck believes that, “I believe the intensity with ultimately, laws need to be changed to allow additional harvest on which they are logging 6,300 federal lands. High fuel loads will continue to acres, while leaving 25,000 acres serve as a tinderbox for megafires, he argues, without any planned recovery which often start on public lands and then effort, as I understand it, begs a grow large enough that they encroach onto lot of questions.” – Rick Sohn private lands where they can often be contained because private lands are more intensively managed and therefore have less fuel to burn. burns, the 2009 Williams Creek Fire and the 2015 Cable Crossing Fire. Where it reburns, it

Matt Hill, CEO of Douglas Timber looks particularly nuked.” Operators, shares Beck’s view that the way the U.S. Forest Service and BLM lands are managed needs to change. There is consensus that the Archie Creek Fire was unique. It was late in the season, after 100 days without rain, and strong east winds “This isn’t the choice of the current federal pushed the fire into a fast blaze that destroyed land managers,” says Hill. “They inherited everything in its path, mostly within the first these sets of regulations and they are doing 36 hours. Could it have been prevented, or at the best they can with them. But that doesn’t least mitigated, by different strategies? mean we need to accept them for another generation.” Hill is reluctant to answer definitively. Hill explains that the federal lands in Douglas County and elsewhere in Oregon are predominantly closed to salvage to protect spotted owl habitat, a default practice that he believes should be reconsidered in light of events such as the Archie Creek Fire. “Weather, topography and fuel affect fire,” he explains. “We can’t change wind or topography, but we can affect fuel. We just replaced tens of thousands of acres of living trees filled with water with dead trees filled with pitch, which is basically standing firewood for the next fire. That poses a significant risk to adjacent “We are 25, 26 years into this management communities in the future. Moving forward, plan for the spotted owl, and the fire calls managing fuels and having places where we into question the effectiveness of that can defend against fires is critically important strategy, as well as what they are doing after and it is something we need to be working with the fire,” he says. the federal agencies on.” Hill estimates that 15 percent or less of the burned lands under federal ownership will see any significant recovery activity, such as O f these federal agencies, the BLM manages 403,044 acres of public land called the Roseburg District, which mainly falls removal of dead trees and planting of seedlings. within Douglas County. Approximately 40,000 “They will be left to rot, deteriorate and of those acres burned in the Archie Creek Fire. reburn,” he says. “And we have seen that burn- Of these, approximately 13,000 acres within and-reburn cycle play out over and over in the fire area are classified as Harvest Land Southern Oregon. Even within the Archie Base (HLB), which has a primary focus for Creek Fire, the fire reburned two different old sustained-yield timber production. The BLM is proposing to salvage 6,300 acres of the HLB

by focusing on areas affected by moderate- to high-severity fire in burned stands aged 40 to 160 years old in the Calapooya Creek, Rock Creek, Canton Creek, Little River and lower North Umpqua River watersheds. “Recovery efforts by the Bureau of Land Management continue to focus on minimizing threats to life and property as well as preventing degradation to natural and cultural resources,” says Field Manager Michael Korn of the Roseburg District BLM. “These efforts began with suppression-repair efforts during the fire and have been ongoing since. Initial actions have included erosioncontrol efforts through stabilization of fire lines and roadways prior to the winter rains. Continuing activities this winter have been extensive, ranging from working with adjacent property owners and utilities in support of their recovery efforts to tree planting, storm patrol and continued hazard-tree mitigation.”

Other planned activities include stabilization projects and restoration of recreation infrastructure, including various hiking trails. At the time of writing, all BLM lands affected by the Archie Creek Fire are closed to the public. “We are committed to serving and supporting local communities impacted by the Archie Creek Fire and appreciate everyone’s patience during this long-term recovery effort,” says Korn. He notes that the public can learn more about BLM’s long-term planning efforts for forest management and recreation opportunities and provide feedback through the organization’s e-planning website (blm.gov).

Thomas McGregor, current treasurer of Forest Bridges and a former president of Umpqua Watersheds, believes that the additional regulation and bureaucracy required of the BLM and other public entities serve a critical purpose. “They have an onus to all Americans when they approach our lands,” he says. “Following

“Not restoring these forests is like a doctor refusing to treat a burn victim. We are smart enough to do salvage in a kinder and gentler way than my grandfather would have done it.” – Paul Beck

the NEPA (National Environmental Policy advocate for only industrial activity after Act), following considerations of endangered a fire. I am an advocate for science-based species, and as the Biden administration looks approaches that bring a diversity of activity.” toward climate as a major factor in how we manage public lands, I think that prudence and taking extra steps are wise things to do.” He notes that a mixed-age and diverse stand of trees is less likely to burn with high intensity and may allow wildland firefighters McGregor thinks that to be more effective. ongoing dialogue around the variety of concerns, even on a national scale, is important. And he thinks that leaving a good amount of timber is, too. “We are needing to make “I am not an advocate for only industrial activity after a fire. I am an advocate “We now have a completely different climate, and every tree counts,” he says. “I think the Archie Creek Fire is a game-changer a priority of carbon storage and the legacy for science-based for our community. I think all of us can habitat for wildlife that approaches that bring agree that seeing we have enjoyed and we want our grandchildren a diversity of activity.” the landscapes that we used to enjoy on to enjoy,” he says. “I the North Umpqua, strongly believe we need – Tom McGregor now after the fire, to have variable density is a real wake-up harvests and leave gaps call. We need to and skips, not clear-cuts, when we approach have dialogue on all viewpoints on how we land management, whether it is brown stands are going to manage this century of change or green stands. I do agree that we need to be and how we are going to find resilience for planting trees, but perhaps we need to also our forests.” be planting elderberries for elk or trying to create a mosaic on the landscape. I am not an

Because Time Doesn’t Heal All Wounds

BECAUSE TIME DOESN’T HEAL ALL WOUNDS \ MATTERS OF THE HEART

Health

CHI Mercy’s Center for Wound Healing offers relief to Douglas County patients who are among the 8 million Americans living with chronic, non-healing wounds.

Story by Dick Baltus Photos by Thomas Boyd

Who would have thought a toothpick could cause so much pain and suffering? Not Steven Smith. At least the 70-year-old Wilbur resident wouldn’t have thought that before he stepped on a toothpick protruding from his shag carpet and drove it through his big toe and into the one next to it, skewering the two together. That’s why the retired cabinet maker just went about his business after the incident. Sure it hurt, but how could a toothpick wound be anything but a minor injury? Five days later, when the pain and infection had become too much to bear, Smith had his answer. “Turned out it was a lot more serious than my wife and I realized,” he says. “I almost had to have the foot amputated.” What followed Smith’s self-characterized “stupid accident” was a trip to urgent care and then to a Roseburg podiatrist, followed by an immediate referral to a Eugene specialist and a five-day stay in a hospital. Upon his discharge, Smith was released into the care of CHI Mercy Health’s Center for Wound Healing and Hyperbaric Therapy. He may have been out of the hospital but he wasn’t out of the woods. As an inpatient in Eugene, Smith’s wound had become infected. So he had to visit Mercy seven days a week to continue the

Wound Center staff includes (from left) Vanessa Darnell, NP-C; April Barron, CNA; Sarah Belloir, LPN; Jasmine Minyard, RN; Megan Priest-Free, RN.

infusion therapy that was started in the hospital. He also started making weekly visits to the Wound Center. The Wound Center serves patients with “non-healing” wounds, defined as those that haven’t healed after 30 days, according to the center’s director and registered nurse Misty Jungling. There, patients with wounds from a wide range of accidents or conditions have access to state-of-the-art technology and specially trained staff who work closely with patients’ physicians, surgeons and other providers to achieve the goal of healing patients within 14 weeks. “We see a lot of post-surgical patients, burn victims and a lot of people experiencing complications from diabetes,” Jungling says. “About 80 percent of the wounds we see are related to venous insufficiency (malfunctioning vein valves that can cause leg ulcers and other issues).” Patients begin the healing process with a 90-minute to twohour initial meeting in which staff educate themselves about the patient’s condition and history, their lifestyle and more and in turn educate the patient about “what is going on with their wound, why it’s not healing and what we can do to get it to heal,” Jungling says. Treatment can take a variety of forms, from compression therapy and wound dressings to bio-engineered skin grafting and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which, says Jungling, “helps the body’s oxygen-dependent, wound-healing mechanisms function more efficiently.” Mercy’s inpatient staff and Center for Wound Healing team only needed 10 weeks to get Smith’s infection remedied and his wound healed. During his care, he used a wheelchair and walker to get around and keep the weight off his injury. The care he got at Mercy, Smith says, made a huge difference in his outcome and quality of life. “Both the infusion unit and the Wound Care Center were fantastic,” he says. “They make sure they have answered all your questions before they go further in the treatment. They were very informative about what they were going to do, how they were going to do it and why they were doing it.” Smith says he is up to “about 95 percent” of where he was before the accident and what turned into three months of inactivity. “I’m doing really well,” he says. “I’m able to walk around again and pretty much do the things I was doing before. I can’t tell you how pleased my wife and I were with how I was treated.”

While most patients of Mercy’s Center for Wound Healing are referred by their physicians, self-referrals are accepted. For more information, call 541.677.4501.

Matters of the Heart

Dr. Gary Bronstein

In Shaw Heart and Vascular Center, Umpqua Valley residents have access to a regional resource for advanced care for an vast array of heart- and vein-related conditions.

Story by Dick Baltus Photos by Thomas Boyd

Since 1985, CHI Mercy Health has been committed to building a comprehensive heart program designed to ensure Umpqua Valley residents rarely need to leave the area for state-of-the-art technology, expertise and care. Beginning in 2007, those heart services have been consolidated in the Shaw Heart and Vascular Center, which in the ensuing years has been growing in service offerings, stature and national reputation. When the center opened, Mercy’s heart team consisted of four cardiologists and one catheterization lab, used primarily for diagnosing blocked blood vessels to the heart. Today the Shaw Heart and Vascular Center team is composed of seven cardiologists, a cardiac nurse practitioner and many additional support personnel. But the growth in staff only tells a small part of the story. It is the expertise they have brought that has earned Shaw Heart Center renown as a regional resource for comprehensive cardiac care and status as one of the nation’s highest-performing heart centers. The center’s general and interventional cardiology and radiology services have dramatically changed the lives of hundreds of area patients whose risk of heart attack or limb amputation has been dramatically reduced, or eliminated altogether, by non-surgical procedures to restore blood flow through blocked vessels. A comprehensive electrophysiology program also has been established to diagnose and treat abnormal heart rhythms.

Countless lives have been improved, and often saved, because of access to the care available at Shaw Heart, says director Connie Kinman. “For example, if a patient is brought to the emergency department with chest pain and has a positive EKG, we have the ability to immediately place a stent in a blocked coronary artery to reopen it. Since ‘time is muscle,’ this program has saved many lives.” As Shaw Heart has grown so has its status on the national level. It was the first program west of Texas to earn national Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence certification from the American College of Cardiology.

cardiology fellowship at New York Medical College. In addition to general cardiology and coronary angiography, Dr. Bronstein is trained and certified in echocardiography (cardiac ultrasound), nuclear cardiology (examination of cardiac blood flow using radiotracer markers) and management of implantable electrical devices (pacemakers and defibrillators). In Roseburg and Shaw Heart Center, Dr. Bronstein has clearly found a home. “I wouldn’t want to live and practice anywhere else,” he says “The patients are friendly, the hospital personnel is very supportive, and everyone is easy to deal with. It is vastly different from my prior experiences in many other places.” Here are just a few of Dr. Bronstein’s Shaw Heart teammates:

“The quality of care available at Shaw Heart and Vascular Center starts with people who provide that care,” says Dr. Gary Bronstein. “We have a superb cardiac care team and a highly trained support team. We also have all the required technology for up-to-date practice and a close relationship with specialized cardiac surgery, electrophysiology and congestive heart failure consultants across Oregon.” Dr. Bronstein, board certified in cardiovascular disease, internal medicine and nuclear cardiology, has been an integral part of that team since its early days. After working in private practice in Texas for two years, Dr. Bronstein practiced at Shaw Heart for four months on a temporary basis. That’s all the longer it took to convince him to relocate to Roseburg for good. “I loved the people, the scenery, the climate and everything else, so I decided to stay and bring my family here,” he says. His current home is far removed from his original one. Dr. Bronstein I was born and raised in Moscow, Russia. He moved to the United States with his family in the 80s, during a period when the Russian government was allowing emigration again after it had been shut down for many years. “My family wasn’t taking any chances (that it would be shut down again) so we moved in ’89, when I was right in the middle of medical school,” Dr. Bronstein says. He finished his medical degree at Stony Brook School of Medicine, in Long Island, N.Y., then did his internal medicine residency at the University of Michigan, served as an attending physician at Columbia University School of Medicine and completed a

Jean Brewer

Registered Nurse

Background: “I grew up here and got my nursing degree from UCC. I moved to Portland, got a job at St Vincent’s and received education in ICU/CCU nursing. I returned to Roseburg and became the fourth member of the Shaw Heart Center staff.” Inspirations: “I was inspired by my mother who was employed here and from my oldest sister who also studied nursing.” Favorite Part of Your Job: “Working with the patients. I have always tried to instill confidence by being professional and competent and using humor and music to calm my patients.” Your Idea of a Great Day at Work: “When I can make a difference in someone else’s life, whether it be a patient or a co-worker.” What Do You Appreciate Most About Shaw Heart? “I enjoy learning, and there is always something new to learn here.” Best Words to Describe Shaw Heart: “Professional, intelligent, great place to work.”

Shelby Schulz

Sonographer

Brittney Goodell

Registered Nurse

Background: “I grew up in Roseburg, went to Glide High School and attended Oregon Institute of Technology, where I competed in track team and got my degree in echocardiography. Prior to joining Mercy I worked at PeaceHealth in Springfield.” Inspirations: “When I started at OIT I shadowed many different types of ultrasound. Cardiac just clicked. I think the heart is the most fascinating part of the body.” Favorite Part of Your Job: “I love that every patient is different and brings a new challenge to each day. I also enjoy that no matter what, you can always learn something new. My co-workers are pretty great also.” Your Idea of a Great Day at Work: “Walking out the door feeling like I made a difference, whether it’s discovering someone’s new cardiac issue or just being there for my patients, giving them someone to talk to when they might be feeling scared.” What Do You Appreciate Most About Shaw Heart? “How friendly everyone is. From Day One, everyone has been so welcoming and helpful to me as I continue to learn and grow as a sonographer.” Best Words to Describe Shaw Heart: “Thorough, patientcentered, friendly.” Background: I was born at Mercy, raised in Roseburg and graduated from the UCC nursing program in 2013. I worked as a certified nursing assistant for six years prior to obtaining my R.N. license.” Inspirations: My oldest son, Zaydin, inspired me to start my career; however, my mother set the healthcare scene for me. She went from CNA to LPN to RN so I kind of just followed in her shoes.” Favorite Part of Your Job: “Helping to save a life. Patients are the whole reason I do what I do. Also, we have a great group of people working here. Even with the stress of the job we find a way to make the best of our time together.” Your Idea of a Great Day at Work: “Everything running on time. When we can follow our schedule without multiple disruptions, it makes for a better day. What Do You Appreciate Most About Shaw Heart? “Support from co-workers and doctors, opportunities to use critical nursing skills and continue my training.” Best Words to Describe Shaw Heart: “Challenging, gratifying and camaraderie.”

Heartfelt Giving

Shaw Heart and Vascular Center takes its name from a Chicagobased foundation that has since 1989 contributed more than $3 million to CHI Mercy’s efforts to grow a state-of-the-art regional heart center. The foundation was established by the Shaw family, which started Yellow Cab Company. The foundation’s board of directors was comprised of family members and included Gordie Iler, who by 1989 was living in Roseburg, where he would be introduced to Sister Jacquetta Taylor, Mercy’s longtime CEO. “Gordy loved to tell the story of that first meeting,” says Lisa Platt, CEO of Mercy Foundation. “Jacquetta started their conversation by calling him Mr. Iler. He interrupted and said, ‘You can call me Gordie,’ and so she continued, saying ‘Gordon, I want some money for our heart center.’ He said, ‘How much,’ and she said, ‘$25,000.’” Upon Iler’s recommendation, the Shaw Foundation would give $32,500, kicking off a longtime relationship that would result in annual gifts for a wide array of technology and programs. Iler died in 2020, but his family’s name will forever be attached to the state-of-the-art heart center he was so instrumental in advancing.

ANOTHER GREAT BAD DAY / SUPER BOWLING / B&BX3 / RURAL SANCTUARY

Another Great Bad Day

A trio of local golf aficionados have taken the reins of three local courses with hopes of boosting the popularity of the sport in the Umpqua Valley.

Story by Hunter Normand Photos by Thomas Boyd

Stepping onto the first tee box, the beautiful open green spaces of Oak Hills Golf Club are spread out in front of me. I feel the crisp air of a mid-January evening and watch the sun setting over the valley. Judging by the orange hue of the clouds, I guess we’ll only get nine holes in before we have to pack it up. I take two practice swings in advance of my first attempt to show the retirees in my group what I can do. At 23, I should be able to hit a golf ball about a quarter-mile. Mine, unfortunately, sputters a few yards off into the fairway, seemingly embarrassed by my effort and seeking a place to hide from me. It’ll be a rough round today, but that’s fine. I play for different reasons. Adjacent to I-5 in west Sutherlin, Oak Hills is the flagship course for an operation that also includes Myrtle Creek Golf Club and Stewart Park Golf Course. The owners, general manager Brad Seehawer, golf pro Scott Simpson and superintendent Scott Zielinski bought Oak Hills in 2016 and have leased Stewart Park and Myrtle Creek from the city since 2016 and 2019, respectively. After an ugly seven strokes on No. 1, I hit an arcing shot off the second tee only to follow up with a visit to the thicket. Somehow I find the errant ball and, when no one’s watching, accidentally kick it into the fairway. Don’t judge; I didn’t invent the move. I use my nine iron in hopes of floating a shot over an oak tree, but instead punch the ball beneath its branches. My chip onto the green lands five feet from the cup, but I miss the putt and tap in for double bogey. As the adage goes, “You don’t paint pictures on a scorecard, you just write down a number.”

Simpson grew up playing golf, and spent his early years watering the course at Oak Hills. After his discharge from the Navy, he coached the Sutherlin High golf team for three years before becoming the club pro in 1998. He splits time between Oak Hills and his full-time sales job at Clint Newell Auto. “I make my money selling cars so we can keep funding the golf course,” Simpson jokes. The houses lining the fairways add to the scenery and, somewhat to my surprise, no windows were harmed in the making of this story. Not that I didn’t try. As I search another hidden landing spot in someone’s backyard I can almost feel the homeowner’s disapproving eyes on my back, though I only see empty windows. Still, I keep my expletives in check as I search again for my rogue ball. I pray no one has seen my play today, except for God, who, I am convinced, is laughing. The owners want to upgrade the courses in their charge to enhance the customer experience. The biggest maintenance expense for the three courses is sand. “You spend about $4,000 to $8,000 per load and that only covers a quarter of a hole,” Simpson says. “To sand the entire course, we spend around $350,000.” Other improvements are planned, such as a rebuild of the Oak Hills clubhouse, which will include four electronic driving range stalls where players can compete in leagues and “play” on different virtual courses like Augusta National. “We’ll have monitors which will show your ball speed and launch angle, which is what everybody wants now,” Simpson says. After another horrendous tee shot, I kick my ball away from the wall it lands against. (Seriously, you’ve never?) Two shots later, I hit a 145-yard rainbow that lands on the green as if I’d planned it. For me, however, no good shot goes unpunished, so I scar this one’s beauty with another ugly putt. But the sun feels warm for this time of year, the birds are chirping and the sky is a beautiful blue. Have I told you I play for different reasons? Simpson wants to get more young golfers on the course. All three courses offer free golf for juniors, and camps are held during the summer. But fewer kids are golfing every year. “In the 90s, when I was running the camps, we had 115 to 120 kids. Now, we’re down to 12 to 15,” Simpson says. With other sports growing, and video games becoming ever more popular, getting kids to golf is difficult. But, Simpson points out, golf can be a pathway to success. “Three of the juniors I coached went on to earn full ride scholarships,” he says. With a babbling brook to my left and the sun setting over the hills to my right, I feel at peace, even as my game continues to implode. On this hole, it takes three putts to sink the disobedient white spheroid into the little green cup. It’s a testament to the course and sport that, even on your worst days, you still enjoy every hole. The course management group offers a membership that includes greens fees and a cart for $2,500 annually. Called the “Triple Play,” it allows the golfer to play at three courses throughout the year for a set fee. The goal, along with specials such as Mother’s Day and Father’s Day golf, is to build membership and grow the golf community around the Umpqua Valley. As darkness falls on Oak Hills, I’m sad to see the course fade into the night, more for the loss of scenery than the end of my round. My score was forgettable, but not the tranquility of being outside, in the cool January breeze, enjoying a great game no matter how poorly I played. I say ‘good riddance’ to the round, but only ‘til next time’ to the Oak Hills course. I’ll be back soon.

Super Bowling

For almost 15 years, TenDown Bowling and Entertainment Center has been a go-to destination for family fun and great food and brews.

Story by Nate Hansen Photos by Thomas Boyd

Bowling has taken Bryon Smith around the U.S. and beyond. Since turning pro after high school, the Umpqua Valley native has won bowling tournaments from coast to coast in the U.S. and traveled to compete in the Japan Cup in 2002. A life on the lanes eventually led Smith back home, where he is now co- owner of TenDown Bowling & Entertainment in Roseburg. Smith honed his skills at his parents’ bowling alley in Sutherlin. After high school, he took his shot on the Professional Bowlers Association tour. “I wanted to find out just how good I really was,” he says. Smith’s bet on himself paid off. For the next two decades he competed at the highest levels of professional bowling and, in 2003, he captured the American Bowling Congress’ Masters national championship. “I spent 20-plus years traveling,” Smith says. “I went everywhere. I even spent a month in Japan. It was a really great experience.” Wanting to settle into family life and spend less time on the road, Smith shifted his focus to TenDown, which opened in December 2007. Smith is one of TenDown’s five owners. The bowling center/ restaurant is largely a family business which includes his wife, Mariah, brother and sister-in-law, Brett and Kristen Smith, and Bob Reed, who brings to the business 38 years of bowling center experience. Reed started working at his family’s bowling center as a teenager, which led to a job in bowling-center mechanics that took him to three continents. TenDown was constructed from the ground up, on the same Diamond Lake Boulevard site where another bowling center was razed. Smith used his travels to and experience with other bowling centers when designing the space. “I saw a lot of concepts in other parts of the country that we could bring to the Northwest,” he says. One of those concepts, according to Reed, was to focus on attracting more customers than just serious bowlers. “We wanted to appeal to whole families,” he says. “We have an arcade so kids can play games and a sports bar with a full menu and cocktails, so it’s not just snack-bar food.” The restaurant and bar, Splitz Grill, also has one of the area’s best selections of local and regional craft beers. The COVID-19 pandemic has, of course, presented challenges to TenDown, but the center’s owners have been trying taken the past year in stride. “It’s very important to us that everyone who comes in feels safe.” says Mariah Smith. “We want families to have a sense of normalcy here, even with the added guidelines.” She adds that TenDown helped lead the charge to reopen bowling centers across Oregon. “When the state was reopening businesses, bowling was originally classified as a ‘Phase Three’ activity, so we couldn’t even be open,” she says. “We developed a plan for TenDown to open in a safe manner, and got that plan on the governor’s desk. With that we got bowling placed in ‘Phase Two.’” “I’m really proud to be with these guys.” Reed says. “We’ve had to completely change our philosophy, but I think we’ve got an A-grade team.”

TenDown Bowling & Entertainment is located at 2400 N.E. Diamond Lake Blvd. Check operating hours through the pandemic at tendownbowling.com.

TenDown co-owners (from left) Bob Reed, Mariah and Bryon Smith and Kristen Smith. Not pictured: Brett Smith.

— Mariah Smith

B&Bx3

As the world gradually begins to reopen (fingers crossed), you may find yourself inundated with out-of-town visitors. If so, unique lodging options abound throughout the Umpqua Valley. Here are three.

Story by Don Gilman Photos by Thomas Boyd

John Rast House

Built almost entirely of Douglas fir, the Rast House reflects the aesthetics of the era of its construction. The home boasts high ceilings, mahogany beat board, a soapstone fireplace and oak flooring. Exactly when the house was built, however, is something of an open question. Purportedly constructed in 1875 by John and Clara Rast, current owners Cherri and Mike Herriman think it might have been built three years earlier. “We’re still researching a lot of things out,” Cherri Herriman says. The Herrimans purchased the historic home on Stephens Street in Roseburg in August 2019, but it took a lot of hard work to get it ready for guests. The Covid-19 pandemic also made business a struggle at first, but the Herrimans have persevered. The Rast House is an oasis of quiet despite being on one of Roseburg’s busiest streets. The tranquility belies the derelict state the Herrimans found when they took possession. “This place was terrible,” says Mike, a retired electrical contractor. “It had been vacant for 20 years.” Graffiti covered the walls, light fixtures had been stripped and trash was everywhere. The restoration took six months and required nearly every available minute. But the finished product was the fulfillment of the Herrimans’ dream. “We lived in Grants Pass for 25 years,” Cherri says. “I was ready to start something new. Mike was ready to retire. I still wanted to have a purpose and I’ve always dreamed about having a B&B.”

Find the John Rast House at 236 S.E. Stephens St. and book online at johnrasthouse.com

The South House

Amy Magnus runs The South House Bed & Breakfast in Oakland with her fiancée, Pete Lund, and father, Joe Crudo. Originally a commercial building, the structure did not impress Magnus initially. Her father had run across it online and suggested she take a look. What she saw was a lot of work, but Dad was insistent. She had long wanted to run her own business, but the idea for South House wasn’t born until she looked at the property. “I always wanted something to put my name on,” she says. “The idea for a bed and breakfast popped into my head and I ran with it. I just went with my gut. At that time there was no lodging in Oakland.” Like everyone else, Magnus and her family felt the sting of the Covid-19 pandemic, but 2020 also brought her an extra serving of misfortune. “Last March I got laid off from my regular job, got diagnosed with breast cancer and then the whole thing shut down,” she says.

A sudden spate of COVID-related cancellations was a further setback. But slowly business began to pick up. A training session by Airbnb gave her a chance to bring South House up to standards and begin again to accept guest reservations. While cancer treatments took their toll on Magnus, with the help of family she kept The South House open. “It was something I had to wake up for every day,” she says. “I still needed South House to thrive. It gave me a reason to get up, take that shower, put on the positive pants and go for it.” Magnus’ chemotherapy ended last September. Her health is improving and she’s looking forward to the future. “My health is good, they got all the cancer out. I’m doing great today,” she says.

Find The South House Airbnb at 129 S.E. Maple St., Oakland, and on Facebook.

Terraluna Inn

Sitting above and removed from Main Street a few blocks from downtown Roseburg, Terraluna Inn is a stately colonial-style house built in 1925. Its interior is a cool oasis of rich, welcoming rooms, modern touches and Zen-like retreats where guests can enjoy a quiet, restful stay. With golden oak flooring downstairs and Douglas fir upstairs, Terraluna is a unique mixture of vintage stylings. James and Gail Ragsdale bought the home in May 2017 and worked furiously to get the bed and breakfast open for business a few months later. James, a Marine Corps veteran who played in its famed band, earned a degree in music education after his discharge and taught band and choir in public schools until his retirement in 2009. Gail earned a degree in nursing from Southern Oregon University and worked as an ICU nurse for 45 years, including 35 at McKenzie-Willamette Medical Center in Eugene. She retired in 2017. Much of Terraluna is still the original design. Unique touches include a Bakelite-faced record player from the 1940s and a mint-condition graduated scale from a butcher shop. What was

once the house’s mud room has been converted to a light-filled sun room. The fully renovated kitchen is equipped with a modern gas range and amenities, but retains its vintage feel. Terraluna’s grounds are a woodsy retreat with flowers and a small organic garden. Gail grows fruit for canning and fresh servings of Asian pear, and guests are always treated to homegrown, freshcut flowers. “My whole life I’ve wanted to own a B&B,” Gail says. “It’s always been part of my plan for retirement.” While James confesses it wasn’t necessarily part of his retirement plan, he says he found enjoyment maintaining the property and takes pride in ownership. “Gail does her things and I do my things,” he says. “We’re excellent business partners,” Gail adds.

Find Terraluna Inn at 1367 S.E. Main St. and terralunainn.com

Rural Sanctuary

On Happy Compromise Farm, Eryn Leavens and Oliver Gawlik our creating a peaceful refuge for animals and humans alike.

Story by Hollye Holbrook

Photo by Sarah Murphy @adventuresincrittersitting.

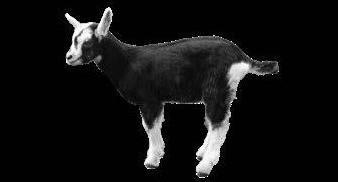

CardiBeak, Pecklemore, Missy Eggliott, Waka Flocka, 2Chirpz and Chicki Minaj. These are just a few of the names you’ll hear while visiting Happy Compromise Farm + Sanctuary, nestled in the hills of northern Douglas County. Stewards Eryn Leavens and Oliver Gawlik moved to the property in July 2019 with a vision of starting a regenerative farm with fruits, vegetables, flowers and, well, some animals. “We brought 11 of our own animals and adopted 24 more who were already living on the property,” says Leavens. “At the time we thought that was a lot. We posted in our Instagram bio that we rescue animals and immediately got requests to take in more. We now have 100.” There are flocks of chickens, roosters and ducks (affectionately named The Lost Boys, The Dragsters, The Goldie Oldies, Party Fowl, Tootie Fruities/Schmidts and Frat Boys); three goats (Herbie Berbie, Big Tony and Fernando); and two alpacas (Hazelnut and Roy). “The sanctuary really took over our first year here,” adds Gawlik. “But it’s been a delightful takeover. The Sanctuary at HCF became a 501(c)(3) registered nonprofit as soon as possible so we could rescue more animals and fundraise for their care. It’s completely donation- and volunteer-run, and we work with other sanctuaries as well.” Walking around the farm with Leavens and Gawlik, the love they have for animals is readily apparent. So is their passion for the land and environment. “We’re looking toward the long term. We minimize anything gas powered – we are the machinery here,” says Gawlik. “Our garden beds are no-till, which is a method that retains the healthy microbiomes in the soil and builds them up over time. It’s a regenerative system where we don’t have to bring in chemicals or many other amendments. We believe that establishing a good relationship with the property and soil will pay off over time.”

— Oliver Gawlick

Oliver Gawlick and Eryn Leavens. Photo by Eryn Leavens.

But the land isn’t the only thing they’re regenerating and establishing a relationship with. Leavens and Gawlik are putting care into humans, too. They’ll be opening a farm stand this year for guests and visitors and donating extra food to a food bank. Next year they plan to have a CSA (community supported agriculture) option. And in the meantime, toward the top of the hill on the property, the two have constructed a yurt that’s listed on Airbnb. “We wanted to create a place where people could come to get away from their busy lives for a few days to stay on the farm and meet the animals or have complete privacy,” says Gawlik. The yurt offers the unmistakable warmth of woodstove heat. Plush robes hang on a rack for guests to wear after using the cedar-steam sauna. Other features include a table with Leaven’s handmade ceramic mugs and tumblers; zero-waste, non-toxic products for the home and a small menu of food that guests can order during their stay. “We wanted to make it an experience,” adds Leavens. “Something special.” Special it is. All of it. With 70 fruit trees, a fire-resistant, zen-like medicinal garden, 23,000 gallons of rainwater collection tanks and hand-built structures for the animal residents, the list of what makes HCF special is a long one. “Our vision for the farm and sanctuary is to create a whole ecosystem where we can raise much of the food our animals need here on the farm, sustain ourselves and help feed our community,” says Gawlik. “And without hurting any animals, or using them for anything,” adds Eryn Leavens. “We want to make sure every animal has the best life possible and is taken care of for their entire life.”

To donate to the nonprofit sanctuary, book a stay in the yurt, find Leaven’s ceramics and learn more, visit happycompromisefarm.com. Find Happy Compromise Farm + Sanctuary on social media @happycompromisefarm.

Photo by Hollye Holbrook.

HOME AWAY FROM HOME HOW KRSB CAME TO BE / Culture

How KRSB Came to Be

Before there was Brooke Communications, there was Roseburg’s first FM station and the Head Goat Observer who made it happen.

Story by Doug Pedersen

It wasn’t widely noted at the time, but Douglas County radio listeners who happened upon 103.1 FM on Oct. 1, 1970, heard history being made. First came the sound of shuffling papers, then a voice that would become one of the most recognizable in the community. “This is KRSB, Roseburg,” said announcer Tom Worden. “Broadcasting at a frequency of 103.1 megahertz.” Worden, who was also a KRSB co-owner, station general manager and program director, then welcomed listeners to the first FM broadcast from Douglas County. That was the start of the KRSB story, one that impacted the Roseburg community, the radio industry as a whole and those who have connected with the station’s personalities, music and stories over its half-century of operation. The crystal-clear, stereophonic sound of FM radio was nothing new at the time. Experimental FM stations began broadcasting in the late 1930s and a commercial FM band was established in 1941. Stereo broadcasting began in 1961. But FM was still something heard largely in large metropolitan areas, not smaller towns where AM still ruled. In Roseburg, that all changed when Tom and Karen Worden came to town. The beginning of that story comes from their son, Eric. KRSB was part of his growing up. Now an on-air host at WNOB-FM in Norfolk, Va., Worden has fond memories of those early days in Roseburg. “My parents got married in August 1960,” Worden says. “Dad was working as a news guy at a radio station in Mount Shasta. After he and Mom met, they moved to Los Angeles looking for the lights.” What Tom and Karen found instead of radio gigs was part-time work at Disneyland. With a new baby in tow, they headed back north to find work and a place to raise their family. Tom landed first at Roseburg’s KQEN in 1961 and later at KRNR, now The Score. “My dad became the news director,” Worden says. “But he wanted to do something bigger. He knew FM was a big deal but he didn’t have the money to start a station. So he shared his dream with several others in town.” Tom persuaded Roseburg brothers, Chuck and Duke Ricketts, to invest in his vision. Chuck owned a local music store and Duke was an attorney. “They also needed an engineer,” Worden says. “Dad got Bob Reece to be part of the group, and WRR Inc. (for Worden, Reece and Ricketts) was created.” In the beginning, KRSB’s studios were in the historic Kohlhagen Building in downtown Roseburg and its tower atop the next-door Hotel Umpqua. For years, Karen led KRSB’s sales team and Tom was the morning host who got national attention for some of his on-air antics. An early example came when an anti-obscenity ordinance was enacted in Roseburg. “The district attorney at the time got Playboy magazine banned through the ordinance,” Worden says. “Dad was an avid reader, so he’d go up to Eugene to get a copy. Then he would read the articles live on the air. Playboy took notice and ran a full-page ad in the New York Times about it. Dad was proud of that.” Then came the KRSB weather goats. Each morning, Tom looked out the studio window to a view of Mount Nebo and a herd of goats that grazed and moved among the rocks. If the goats were near the top of the hill, the town would have fair weather. If they were grazing near the bottom, it meant rain. “The goat weather forecasts were featured on NBC Nightly News, Ripley’s Believe it or Not and in Reader’s Digest,” Worden says. The weather goats’ fame evolved into official KRSB Goat Observation Corps cards, with Tom’s signature and title of Head Goat Observer.

“He’d use terms like widely scattered goats and low-goat pressure system,” Word adds. “Those goats were right most of the time. They were way more accurate than the national weather service.” Gary Donnelly, who partnered with Tom on the morning show before working in public relations at Pacific Power, has fond memories of the goats.

“Tom deserves all the credit for the goat reports,” Donnelly says. “There were people who would not start their day until they heard the goat report.” The goats’ fame endured. “People across the country would ask me about the goat reports years later,” says Donnelly. “I was in Gillette, Wyo., talking about Pacific Power on a local radio station. The interviewer found out

Tom Worden (left) in the KRSB broadcast booth, and with wife, Karen, and son, Eric, in center photo.

I knew Tom and asked if he could get a goat report live on the air. I called Tom and got it done. That guy probably never forgot that.” Eric Worden started his radio career in 1974 as a weekend DJ at KRSB. He later took over the morning show and programming duties. “I’ve been in radio ever since,” he says. “I was very proud of my dad and what he did as a community leader. That’s my calling card.” By the mid-1980s, Tom and Karen wanted to pursue new interests, and KRSB was ready for new ownership. Today, it’s owned by Brooke Communications Inc., whose president, Patrick Markham, is a radio industry expert and longtime broadcast specialist. KRSB-FM is now Best Country 103, but still in the same place on the FM dial. “KRSB is our flagship and has been for 15 years,” Markham says. Brooke’s full list includes Best Country 103, News Radio 1240 KQEN, 104.5 SAM FM, i101 FM, and The Score, simulcasting on 92.3 FM and 1490 AM. “It’s a fun business,” Markham adds. “We’ll keep doing the job we’re doing, which is serving our listeners and clients. That’s what it’s all about.”

House Away From Home

John Hooper’s quest for information about his ancestors took him from his home in Glide to a house from his family’s past

Story by Dick Baltus with John Hooper

He found the book in November 2018. Digging into a box of family memories, John Hooper found photos, mostly, but also his grandmother’s Italian grammar primer and, next to it, an unmarked antique text. Curious, he opened to the first page and set off on an adventure that would lead him through his family’s past and to the other side of the world.

Hooper had never known much about his grandmother’s background. “I remember her saying she was Swiss Italian, but I didn’t really know what that meant,” says the Glide resident and owner of Good Vibrations Audio/Visual in Roseburg. So when he saw three names on the inside of the old book, he only recognized his grandmother’s. With the help of ancestry. com, Hooper was able to identify them as Matilde Vittoria Devaux, his great grandmother, and his great-great grandmother, Barbarina Garbani. Now immersed in intrigue, Hooper continued his Internet search for more information about his relatives and quickly found a public notice in Italian with the name Barbarina Garbani highlighted. After translating the ad, Hooper learned that someone was seeking his great-great grandmother’s heirs. Someone on the other side of the world was looking for him. Hooper traced the address in the ad to a courthouse in Locarno, Switzerland, then contacted the editor of the magazine where the ad appeared and verified its legitimacy. “He said they were often contacted by Swiss authorities searching for families of Swiss immigrants to America,” Hooper says. But why, he wondered, would Swiss authorities be searching for the heirs of a woman who died in 1961 in San Luis Obispo, Calif.? Hooper responded to the ad and learned that his great-great grandmother had been the half-owner of a house in Lucarno, and that half was now his and his brother’s. Communicating via email with an attorney assigned to the estate, Hooper was told the house had “no real value” and, as an heir, he could easily sign over his half to the other owners. “It was a lot to take in,” he says. “I had all these questions. Who was my great-great grandmother? Why was half a house in Switzerland still in her name? Who owned the other half? Why were they searching for heirs 58 years after she died? Why should I sign it over without seeing it?” Hooper started digging into genealogy sites. He learned his greatgreat grandmother had immigrated to America in 1908, following her daughter, Matilde, who had arrived in 1905. He also learned the other half of the house was owned by three siblings, but their connection to his family was a mystery. Then Hooper found the house on Google Earth. “It was located on a hillside between two small villages in Ticino, Switzerland,” he says. “There was no road or driveway to it; it could be accessed by foot only.” On Google Earth, Hooper could see the house was “constructed of stacked granite, four stories tall, and looked to be about 200 years old.” Hooper and his brother decided they would have their share of the house transferred to them. Then they had to figure out what to do with it. So they packed their bags.

Dana and John Hooper.

Former owners Adeline Devaux and her husband, Emilio Guidetti.

“I had all these questions. Who was my great-great grandmother? Why was half a house in Switzerland still in her name? Why were they searching for heirs 58 years after she died?” — John Hooper

On Saturday, Sept. 28, 2019, 10 months from the start of Hooper’s journey, he and his wife, Dana, and his brother and wife picked up Achille Poletti, the youngest of the three sibling co-owners, and a translator and headed for their new-found home. On the walk up from the trailhead, the travelers were treated to stories of the property and structures they passed along the way, including an old stable and a relatively modern barn, constructed from pink block that reminded Hooper of his grandmother’s pink bathroom fixtures. And then they reached the house. “There were palm trees, even a kiwi tree growing in the front yard,” Hooper says. “The roof looked brand new, and Achille explained that a helicopter had to be hired to deliver the tiles for it.” The group sat at a rock picnic table in the backyard and watched their new partner, Poletti, fish a stack of paperwork from his backpack. “The first thing he showed us was a photograph of two people standing in front of the home sometime around 1908,” Hooper says. “They were my great aunt, Adeline Guidetti, and her husband, Emilio. Adeline’s sister, Matilda, was my great grandmother. When she and my great-great grandmother immigrated to the U.S, they left Adeline with the house. That’s where she lived the rest of her life.” Poletti told the group that Emilio had been a successful businessman with stores and other homes in the local villages. But when the economy turned downward, and villagers were unable to pay the accounts carried by Guidetti, he and Adeline were forced to move into his wife’s family home. The Guidettis farmed the land around the home and made cheese to make ends meet. When Poletti’s father, Mario, was 14, he started working as a ranch hand for the Guidettis in exchange for room and board. When Emilio died in 1930, Adeline needed Mario’s help more than ever to keep the farm afloat. In time, Mario would marry Olimpia Fachetti, who helped Adeline in the home while Mario worked outside. They had three children, Achille, Emilio and Rosina. In the mid-50s, Hooper’s great aunt Adeline was diagnosed with cancer, and Mario and Olimpia cared for her until her death in 1957. Before dying, Adeline gave her half of the home to Mario and Olimpia. When they died, the home passed to their three children. Achille Poletti said that he and his siblings had spent their lives caring for the house, never knowing who their co-owner was. He said he had even traveled to San Luis Obispo in 2000, attempting to find someone to talk to about their partial ownership of the house. As Poletti continued to talk about his family making all the needed house repairs, not knowing if they’d ever be reimbursed for half the costs, as he spoke of the weekends family members still spend out the house and the love his children had for it, Hooper turned to his brother. It was clear they were both thinking the same thing. “We knew what we should do,” he says. “We told Achille the Polettis could have our share. It belonged to them.”