9 minute read

Yesteryears

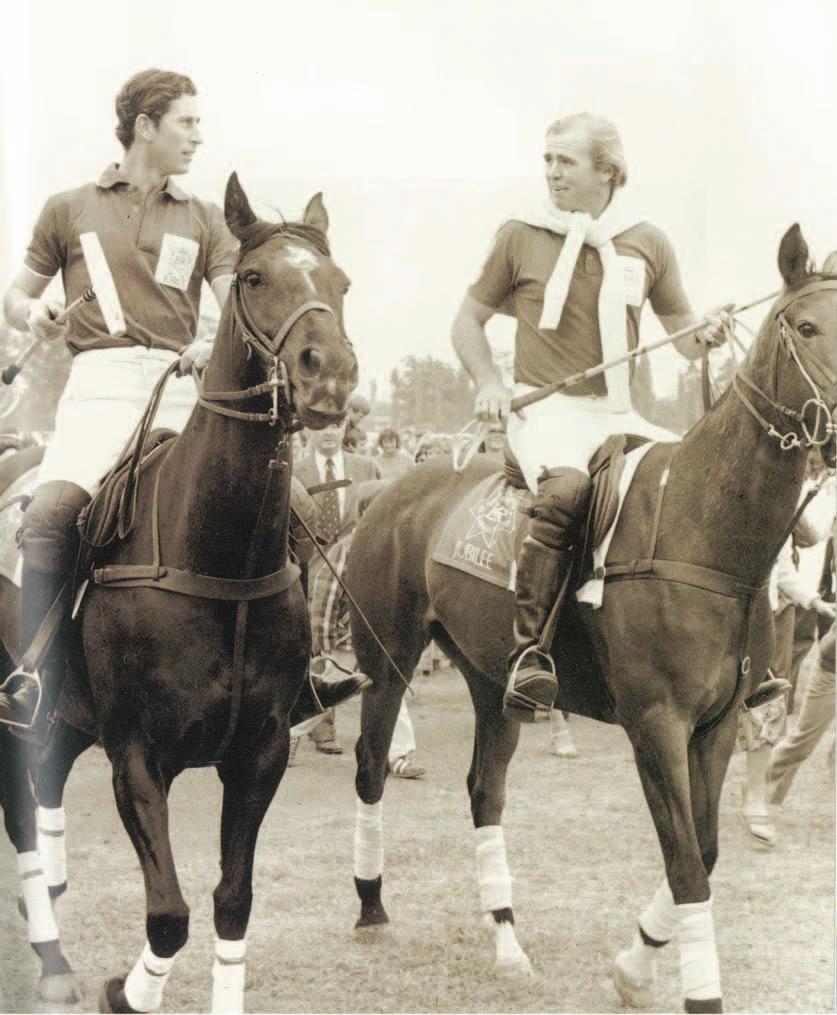

A prince among men

England’s heir apparent was a talented polo player

By J.M. Casper

You can often tell someone’s character by the way they conduct themselves as a sportsman. Geoffrey Kent, who captained Prince Charles’ Windsor Park polo team, put it simply, “It’s not en vino veritas, but en polo veritas.” You can tell a lot about a man by the way he plays polo. If that’s the case, Charles, Prince of Wales, is going to be an exceptional legatee of the British throne.

On the field Charles embodied the same quiet dignity and sense of duty that endears so many to his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, and the drive and determination that made his father, Prince Philip, an international caliber polo player with a 5-goal handicap.

Charles was no hobbyist on a show pony. Quite simply, he could play.

As soon as there was the Guards Polo Club—originally the Household Brigade Polo Club, which Philip helped establish in 1955—there was Charles, aged 7, playing with a polo mallet. A polo pony was the first gift he received from his father. As a young

PA IMAGES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

A young Charles, his sister Anne, mother Queen Elizabeth, and father Prince Philip at Windsor Great Park in 1956.

Queen Elizabeth, Prince Charles, his sons Princes Harry and William and their wives. Charles has always taken his royal duties very seriously.

Prince Charles played with Guy Wildenstein’s Les Diables Bleus in 1987. The previous year they won the Queen’s Cup together.

teenager, the young prince was often spotted practicing with his father at the club. Charles’ beloved uncle, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, also a 5-goal polo player, penned “An Introduction to Polo,” by Marco, a seminal treatise on the game’s fundamentals.

“Lord Louis, I remember, was the man that actually played probably a bigger role in getting Prince Charles involved in polo than his father did,” explained polo legend Paul Withers. “When [Philip] realized that he was serious about it, the two of them took over together helping Prince Charles.”

In 1966, a 17-year-old Charles traveled to the Commonwealth Games in Jamaica with Philip and made his first public appearance as a polo player in a series of matches played in conjunction with the Games, a moment captured on film and archived by British Pathé for posterity.

“Charles, I think, enjoyed playing very, very much,” said Withers, who was on the first all-English team to win the Gold Cup with Prince Philip in 1968. “I think [Prince Charles] wanted to prove to his father that he could do what his father could and was a very good person to play with.”

By age 19, with a 3-goal handicap, he was playing high-goal polo. In 1973, he played in a test match following the Coronation Cup with a Young England team, only to lose in the closing moments to Young America. Charles was selected for the Young England team, which defeated France the year before.

As was the want of The Queen, duty came first, though polo became something between a passion and a healthy obsession for Charles. The prince was ranked among the top 10 British poloists and played every chance he could get.

At the height of his career, Charles played back alongside Julian Hipwood—the first Briton to be rated at 9 goals by the USPA since Gerald Balding in 1938—with Guy Wildenstein’s Les Diables Bleus team, making it to the final of the Gold Cup in 1978, one of four finals appearances. He and Wildenstein, along with Memo Gracida and Chile’s Ricardo Vial, captured the Queen’s Cup with Les Diables Bleus in 1986, eclipsing his father who lost in the final for the second time 20 years before. He also played with Hipwood on Canadian businessman Gaylen Weston’s Maple Leafs team.

“You have to give him 10 out of 10 for what he could do on the polo field … to get to 4-goals,” said Hipwood, 74, from his Florida home in Wellington, a short trek from the USPA Hall-of-Fame where he was inducted in 2011. “Prince Charles was always opening some factory or having to give some speech somewhere. Probably 90% of our practices were without him, he was busy. He really did take his royal position very, very seriously, and is true to his words. He is there and does an outstanding job and to reach a handicap of 4. I wouldn’t have gotten to my handicap—I got to 9—if I had to live the life and do all those things he had to do. He wasn’t an ordinary man. He was a very special person.”

In the late 60s, while in the British Navy, Prince Charles met a young British Army officer named

Geoffrey Kent, center, played against Prince Charles, right, in Chicago in 1986.

Prince Charles chats with Lady and Lord Louis Mountbatten at Cowdray Park Polo Club in 1971. Geoffrey Kent on the polo field and the two became fast friends. Eventually Charles asked Kent to be captain of the Windsor Park polo team that disbanded after Philip had retired, an honor Kent, the famed luxury travel mogul, called the pinnacle for a polo player. In the summer, they would often play six days per week.

“Julian said it correctly. I was a 4-goal player and an amateur,” said Kent, who made it to the final of the British Open with the prince in 1987. “He was a 4-goal handicap and he earned it.”

Starting in the late 1970s, Charles brought his

Prince Philip hands Charles a trophy in one of the first tournaments they played together.

talents to South Florida. The one man that could top the pomp and circumstance helped bring attention to the new epicenter of American polo. Though short of the 35,000 spectators Prince Edward saw at Meadow Brook in 1924, about 15,000 polo enthusiasts and royal watchers alike attended when Charles played at Palm Beach Polo and brought his first wife, Diana, to present the trophy at an exhibition in 1985.

“Whenever there was news of [Lady Diana] coming [to watch Charles play polo] there were obviously more people. Everyone wanted to see her … I thought she was wonderful,” remembered Hipwood. “He was a good enough player where he wasn’t just sitting there doing nothing. They just loved it when he gave someone a good bump and came through and scored a goal. You would’ve thought it was a 10-goal player that just made that play; he had just so much support.”

Despite royal prestige and protocol, Charles gave and received no quarter and likewise expected none. He was a throwback, a defensive minded rough-andtumble back who knew where and when to be at the right place at the right time.

“He was very disciplined, a highly disciplined player, very thoughtful,” explained Kent, who won the U.S. Gold Cup and U.S. Open in 1978. “He had his own style but above all he was reliable. I use one word—reliable—you knew he would be there. He is reliable. You can’t say that about many people today. He had honor … they don’t make them like him anymore.

“He wasn’t a wimp. You can write that one down,” notes Hipwood, who enjoyed success here in the States as a professional player after serving as captain of the English National team. “If he had to give

Prince Charles with Australian 10- goaler Sinclair Hill. Hill coached Charles when he played on the Young England team.

Prince Charles played hard and occassionally got hurt. One example is when he fell with his horse in 1985.

somebody a jolly-good bump, he’d give it, and a few too hard bumps and he’d have a penalty.

Added Kent: “We’d give instructions at halftime. Prince Charles said to me, ‘What should I do?’ I said, ‘You, Sir, you just kill. Kill anybody who gets away from us, kill them.’ ‘I got it. I’ll kill them,’ [replied Charles]. That’s it. He is a team player, [and] apart from calling him ‘Sir’ there is no difference.”

That reckless abandon often came at the expense of the royal heir’s body. Though he retired from highgoal polo in 1992, Charles still played in lower-goal matches, often to raise money for many foundations, including The Prince’s Trust.

“Prince Charles did a huge amount on the charity side, as much as he could, and did very well,” said Withers.

Ever the environmental advocate, gossip columnists couldn’t help but point out that Charles had used 70 gallons in fuel to fly back and forth

from a polo match in one day, failing to point out he had raised over $15 million for charity at the game. That microscope partly explains why Charles finds serenity on the polo field.

“Quite honestly, he just loved polo. He just would’ve played all the time. One day he said to me, ‘Julian, I really envy you.’” Hipwood noted. Charles just wanted to play polo and when on the field, be one of the guys.

Finally, after breaking his wrist—an injury Hipwood says could bring tears to his eyes on a mishit even after he recovered—his wife, Camilla, convinced Charles to hang up his mallets for good in 2005. However, he still attends games. As The Queen gets on in years, he occasionally presents the Queen’s Cup at Guards in her stead as well as the Mountbatten Cup played on the same day, which Charles revived in Mountbatten’s honor after his untimely demise in 1979.

“[Charles] is a really good person; he is not quiet in his thinking. He often spoke about his duty, what he had been born into. No matter what, [he] was going to see it through because that was his job. opined Hipwood. “I think he is a true gentleman. I don’t know what other words to use. I wish all sportsmen had his way of playing and his way of wanting to win and accepting if he lost.”

Kent echoed those sentiments. “We are just so lucky to have him. They have no idea of his personality, of his ability in many, many theaters. [People should be] amazingly gratified that he is going to be our next king. They should be really, really happy. He is an amazing, amazing person,” he said. “Prince Charles has all the honor and the caliber of—you know, he’s a prince.” •

Paul Withers, Julian Hipwood, Prince Charles, John Horswell and Howard Hipwood