HIGHLANDER magazine Volume 4 // Issue 1

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Community is at the core of Cache Valley’s natural beauty, present both in its diverse ecosystem and in efforts to protect and appreciate it. The Jardine Juniper, featured on the cover, is estimated to be around 1,500 years old and represents the history, resilience and unmatched splendor of our valley and the Uintah-WasatchCache National Forest. As an onlooker to Indigenous Shoshone people, trappers, Mormon pioneers and continued growth of Cache Valley, the Jardine Juniper has borne witness to the importance of perseverance and preservation. Within these pages are stories of our community’s commitment to education, research, discovery, support, outdoor recreation, art and innovation. Above all, I hope this issue of Highlander inspires us to persevere through hard times and setbacks in an effort to preserve the place we call home.

— Maya Mackinnon

— Maya Mackinnon

04 AIR QUALITY RECORD-BREAKING 08 CAMPGROUND RECONSTRUCTION 10 GREAT SALT LAKE WHAT WE CAN DO 12 INTERNATIONAL DESIGN OPDD 28 NON-PROFITS LOCAL SUPPORT 20 NATURE ARTISTS CACHE VALLEY 26 SURF CULTURE IN UTAH 22 DIRTY JOBS BEAVER ECOLOGY

BEAR RIVER MASSACRE

PRODUCED AND DISTRIBUTED BY USU STUDENT MEDIA

0165 OLD MAIN HILL LOGAN, UTAH 84322-0165

HIGHLANDER EDITOR

MAYA MACKINNON

STATESMAN EDITOR

DARCY RITCHIE

PHOTO EDITOR

BAILEY RIGBY

DESIGN MANAGER

MONIQUE BLACK

ADVERTISING

SOPHIE BAKER-BUNCH

WRITERS

AVERY TRUMAN, HARRISON LARSON, CARTER OTTLEY, CARLY PRICE, SAVANNAH BURNARD, JENNY CARPENTER, CAITLIN KEITH, LEAH CALL

PHOTOGRAPHERS

CLAIRE OTT, SAM WARNER, HEIDI BINGHAM, ELISE GOTTLING, PAIGE JOHNSON

COVER AND INSIDE PHOTO BY BAILEY RIGBY

The Scottish thistle stands for strength, bravery, durability and resilience.

18

UNDERSTANDING

THE STATESMAN | BLUELIGHT MEDIA | AGGIE RADIO

Cache Valley hits record-breaking levels of wintertime ozone

AVERY TRUMAN PHOTOS BY BAILEY RIGBY

AVERY TRUMAN PHOTOS BY BAILEY RIGBY

This winter has been particularly cold in Logan and the skies have been unusually clear. This gives the sunlight a chance to reflect off of sitting snow, creating more ozone, which is very harmful to breathe in.

Utah State University professor Randy Martin teaches about air quality and pollution control.

“Since 2012 or so, there’s been remediation — regulations and scenarios put in place,” Martin said. “They’ve probably helped us out a bit, but we’ve also had very mild winters for most of the last 10 years or so.”

Martin said the conditions of this winter were not unexpected.

“A lot of us in the meteorological, environmental engineering, environmental science community kind of were waiting for this to happen,” Martin said. “Specifically, we hit air that we haven’t really seen in about a decade.”

According to Martin, Cache Valley can potentially expect another month of bad air quality.

“Even though we’ve put emission reductions in place, we’ve had increases in population,” Martin said. “People are driving more miles on their vehicles, so our potential for sources has, unfortunately, gone up.”

Martin said high wintertime ozone is rare because it usually needs a large amount of sunlight.

“Last week, it was bad enough that we had literally hit the highest ozone — wintertime ozone — that we’ve ever recorded here in Cache Valley,” Martin said. “Even though it’s inverted, we had relatively clear skies, and then we had snow on the ground that reflects the sunlight.”

Martin compared the effect of higher wintertime ozone to the sun reflecting off of the snow when skiing, which makes it easier for the skier to get a sunburn.

“Normally, the air near the ground is warmest so it allows it to convectively mix,” Martin said. “But when it’s cold air at the bottom, just think of it almost like a river — that cold air sinks down and wants to seek the lowest levels here in the valley. And we don’t really have a large enough drain if you will.”

Martin said there are multiple reasons the air quality has been so poor this winter.

“One of them being the fact that we live in a valley, so that doesn’t allow our air pollution to escape very easily,” Martin said. “We get cold stagnant air that allows the inversion to form.”

According to Martin, inversion is when cold air has nowhere to escape because it is trapped below warm air.

4

“Our main particle of concern in Cache Valley is something we call ammonium nitrate,” Martin said.

Overall, the air quality in Utah is getting better, according to Martin.

“A lot of that has to do with the programs that have been put in place at the local and state level — until this winter,” Martin said. “That doesn’t mean we can just ignore it this year, because it’s affecting your health.”

Martin said even short-term exposure to bad air can affect lung capacity.

“If it’s exposed chronically, over time, it will decrease your lung capacity overall, not just the short term,” Martin said. “Which makes you more susceptible to various disease states as well.”

Martin said air quality can affect many different aspects of health, including an increased risk for reproduction issues, cancer, stroke, depression, Alzheimer’s disease and more.

“Pick your favorite body part, and air pollution can affect it, including mental issues,” Martin said. “We found out that our ammonia in Cache Valley were ammoniarich, meaning we have excess ammonia.”

Avery Cronyn, a senior at USU and the sustainable transportation manager for Aggie Blue Bikes, said it can be difficult to travel on bikes when the air quality is poor.

“There’s kind of two different types of people,” Cronyn said. “There’s the people who are not biking when the air quality gets bad so that they save their lungs, and then there’s people who are biking when the air quality is bad because they don’t want to contribute to bad air quality.”

Cronyn said driving less is a good way to increase the quality of Cache Valley’s air.

“Cache Valley has a free bus system, that’s a great way to reduce emissions,” Cronyn said. “If you’re driving your own car, avoid idling. Just really idling as little as possible. I know meat consumption is a big contributor to pollutants.”

Cronyn said the quality of air has affected him personally and is a large difference from his

hometown in Arizona.

“Seasonal affective disorder has been really strong this year,” Cronyn said. “You can’t go out and do anything, and you can’t see the mountains, you can barely see the sun, the moon.”

According to Cronyn, it is important to educate people on this subject because some don’t realize how dangerous the air quality can be.

“It’s not sustainable,” Cronyn said. “You look at the last five years, and this year is the worst for general air quality, but also PM 2.5, just comes from cars mainly.”

In general, Cronyn encourages people to ride bikes for their transportation whenever possible.

“Annually, bikes save over 238 million gallons of gas per year. That’s something I got from bicyclehistory.net,” Cronyn said. “A University of California Davis study showed that if most people switch their transportation travel to cycling, then it could reduce CO2 emissions 10% and save about $25 trillion.”

Marc Mansfield is a senior environmental modeler and research professor at the Bingham Research Center.

“We have ozone in the winter — high ozone reading in the winter,” Mansfield said in a virtual interview. “That’s incredibly rare. There are only two regions worldwide where that’s known to happen. Here, and then the north up in Wyoming.”

According to Mansfield, wintertime inversions, the pollutants being emitted and snow cover all play a role in the Uinta Basin’s air quality.

“We do have an active oil and gas extraction industry here,” Mansfield said. “It’s pretty clear that the precursors — the ozone precursors — are coming from that industry.”

Mansfield said the high level of ozone is not coming from agricultural sources.

“We figured there may be 50,000 cattle in the Basin,” Mansfield said. “But they mainly emit methane, which is not important in the production of ozone. Ozone is the problem here in Uinta Basin.”

Mansfield said poor air quality has always been an issue.

“You can go back 100 years and see photos of the Salt Lake Valley where there’s a haze. In those days, it was because everyone heating with coal,” Mansfield said. “We are required to follow the stipulations of the Clean Air Act.”

Mansfield recommends that people limit how long their vehicles are left idling.

“The ozone concentrations drop off really quickly indoors,” Mansfield said. “So another thing we do is encourage the susceptible people with respiratory issues to stay indoors to avoid outside exposure during these episodes.”

Yoshimitsu Chikamoto is an assistant professor in earth system modeling at USU.

“Poor air quality can also be a problem during the summer, not just in the winter,” Chikamoto said in a written response. “My team is looking at how changing climate affects air quality during the summer.”

Chikamoto said Utah is popular for outdoor recreation activities like mountain biking, hiking and outdoor sports.

“The poor air quality during the summer makes these activities riskier for people’s health,” Chikamoto said. “We have found that Northern Utah will experience more unhealthy air days due to a part of climate change.”

Chikamoto said there are different types of pollution, including ozone, carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and tiny particles.

“The main source comes from larger wildfires in the northwestern United States, which then transported smoke toward Northern Utah,” Chikamoto said. “Therefore, improving Utah’s air quality during the summer would require cooperation between multiple states in the western U.S.”

6

Better Your World by Making LAEP Your Home

If you’re interested in the environment and sustainability and want to make positive changes in the world and your local community, consider making LAEP your home, and pursuing the Environmental Planning undergraduate degree. Use science and creativity to solve problems and implement policy that protects plant, animal, and human life. Learn to understand environmental systems and how to implement policy to mitigate human demands on them.

Nationally, demand for environmental planners will increase 7-11% in the next ten years. Your interests can drive your career. As Professor Daniella Hirschfeld described, “Environmental planning is a fascinating interdisciplinary field of study that brings together natural resources, social sciences, and policy. Students can select areas of focus ranging from water management to urban designs and build an important set of job ready skills.

Within the department, you’ll take a variety of courses to prepare for the profession, and you’ll learn why current students describe LAEP as a “fun environment where people feel accepted and can grow in a healthy way” with “helpful and encouraging faculty.”

If you’re ready to make meaningful and lasting change, and make LAEP your home, visit https://caas.usu.edu/degrees/laep/undergrad/ environmental-planning.

7

PHOTOS BY SAM WARNER

Guinavah-Malibu campsite under reconstruction until 2025

CARTER OTTLEY PHOTOS BY BAILEY RIGBY

Within Logan Canyon and the surrounding area, there are lots of opportunities to enjoy the outdoors, especially through camping. Each of the campgrounds differs depending on the desired experience.

David Ashby, a recreation staff officer for the Logan and Ogden Ranger Districts, said there are a wide variety of opportunities in the canyon.

“The most popular campgrounds are GuinavahMalibu, Tony Grove and Sunrise,” he said. “There are also smaller, more intimate campgrounds such as Red Banks, Preston Valley or Bridger Campground, which provide a different experience with fewer camping sites and are near the Logan River.”

Guinavah-Malibu campground is currently undergoing reconstruction. It would usually be open between May and October. However, it will be closed for the 2023 camping season.

“The first phase started in 2022 by removing the

non-native crack willows from the campground,” Ashby said.

He said the trees were a safety hazard because of their age and size. The trees were also dangerous because they were prone to breakage. They plan to remove the stumps of the trees in the spring, and will begin reconstruction of the campgrounds in the fall.

“All of the campsites and groups sites will be reconstructed while preserving historic features, such as the amphitheater,” Ashby said.

The amphitheater was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s.

Ashby said the reconstruction will not be completed until the fall of 2025.

The reconstruction of the campground is possible because of federal funding from the Great American Outdoors Act, which was signed into law in 2020. The campground will receive a little over $2 million to fund the projects.

The legislation uses revenues from energy development to provide up to $1.9 billion a year for the renovations in national parks and public lands across the country. The act lasts for five years.

In many national parks and public lands across

8

the country, there are roads, trails, restrooms, water treatment systems and visitor facilities that are aging and exceeding the capacity they were intended to hold.

The National Park Service has a backlog of projects addressing these types of issues since they did not have the funding to handle them before the GAOA was signed into law. The federal funding is currently helping to address these maintenance issues.

Other projects have recently been finished at campgrounds in the canyon.

They have installed new fee tubes at picnic sites, removed hazard trees from several campgrounds, added a new restroom in Bridger campground, paved the roads at Tony Grove, improved the water system and installed new signs around campgrounds.

“The day-to-day management of the campgrounds are contracted through our concessionaire, Utah Recreation Company,” Ashby said.

The concessionaire also takes care of routine maintenance.

“Other campground projects would include maintenance of signs, restrooms, parking areas and infrastructure of the facilities through the concessionaire,” Ashby said.

Most sites have bathrooms and drinking water, but check for specific amenities of the one you plan to camp at.

According to Ashby, all of the improved campgrounds and day-use sites in Logan Canyon and the surrounding areas have fees for people who want to use them. Depending on the site selected, the cost per day can range from $10 to $30.

They also offer group site reservations, which can be used for larger groups or special events.

Reservations for these campgrounds can be made through recreation.gov. Reservations for most campgrounds can be made as early as 240 days in advance but they usually need to be made at least five days in advance.

“This is the best way to reserve a campsite,” Ashby said. “There are also opportunities for first come, first serve campsites, but on weekends and holidays it is best to have a reservation.”

The majority of the campgrounds are expected to

open near the middle of May. However, there are some of the campgrounds, like Tony Grove and Sunrise, which will not open until the beginning of July.

The camping season ends between September and October, depending on the campground.

People who visit the canyon can also find opportunities for fishing, rock climbing, mountain biking, paddle boarding, horseback riding and hiking. In the winter, people can enjoy the canyon by snowshoeing, snowmobiling, cross-country skiing and dowhnhill skiing at Beaver Mountain Ski Resort.

Sam Christensen, a resident of Logan, has spent time enjoying what the canyon has to offer. He has rock climbed, walked his dog, gone on drives and used his drone to shoot videos.

“I like to just be with some friends out in nature,” he said. “It’s really fun, and it’s really peaceful.”

Christensen said he also loves all of the trees in the canyon, and how it has so many more than in the valley.

“It just kind of feels like you are going into a whole different world when you go from the valley into the canyon,” he said. “It’s just a whole change in the scenery, which is really cool.”

The canyon connects Cache Valley on the west and Bear Lake along the Utah/Idaho border. It is also part of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest.

Go Camp Utah said the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest is one of the most visited national forest systems, with over 10 million visitors each year. The forest also reaches southeastern Idaho and southwestern Wyoming.

The Cache National Forest portion was first established in 1908. It has since been combined with the Wasatch National Forest and Uinta National Forest to create the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest.

9

What is happening to the Great Salt Lake and what can we do about it?

With the lowest recorded water levels the Great Salt Lake has ever seen, the lake risks losing its diverse ecosystem.

Home to millions of migratory birds and brine shrimp, the deterioration of the Great Salt Lake’s water levels will affect organisms from the bottom of the food chain, all the way up to humans and their environment.

According to a Utah Geological Survey released by the Department of Natural Resources, microbialites are underwater reef-like mounds that form the base of the Great Salt Lake’s entire ecosystem. They serve as a primary food source for brine shrimp and brine flies, which in turn feed the birds that come to the lake.

The survey says with the water levels in the lake declining, a significant amount of microbialites will be exposed. This leads to the microbial mat eroding off of the top of microbialite structures, and takes several years of higher lake level before the microbial mat can recover. This means the primary food source for the brine shrimp and flies is disappearing.

Scott Baxter, a Cache Valley resident, has been kayaking the Great Salt Lake for over 30 years. He has worked with natural resource groups and research scientists, to study the history of the lake.

In September 2021, he circumnavigated the lake with Matt Kahabka to document the lake’s decline. They saw the exposed microbialites first hand.

“It was just like a battle cemetery,” Baxter said in a phone interview. “It was devastating to look at what was happening. We paddled by them for miles. In some places the microbialites were two or three miles deep in between us and the shore.”

The ecosystem is not the only thing that will be affected by the decline in the lake’s water levels. Baxter said when the lakebed is exposed, dust full of arsenic and other chemicals is easily picked up by winds.

“The winds blow right into the Wasatch Front where the population center for Utah is, so it’s going to become a significant health hazard,” Baxter said.

Patrick Belmont, a professor and department head of watershed sciences at Utah State University, said he likes to look at the broader context and understand how everything is interconnected.

“Something like the Great Salt Lake is not just a water problem,” Belmont said. “It’s a people problem. It’s a bird problem. It’s a plant problem. It’s an air quality problem. It’s a climate problem. It’s a snowpack problem.”

One might wonder how local and state leaders plan to look at all of the factors influencing the Great Salt Lake when it comes to creating and changing policies.

USU has an interdisciplinary initiative, called The Janet Quinney Institute for Land, Water, and Air, that brings together USU land, water and air researchers, and connects them with Utah problem solvers.

Brian Steed is the institute’s executive program director.

“We’re working very closely with researchers here on campus getting the best information we can,” Steed said. “Then we’re taking that information to policymakers, both at the local level and the state level, trying to get them to understand what that research shows and how it can be applied to have those real water savings we’re talking about.”

Researchers at USU and the University of Utah formed the Great Salt Lake Strike Team, which includes experts in public policy, hydrology, water management, climatology and dust. On Feb. 8 2023, they released a Great Salt Lake Policy Assessment affirming the urgency of the situation.

According to the assessment, the strike team estimates human and natural consumptive water use comprises 67-73% of the Great Salt Lake’s low elevation, natural variability comprises 15-23% and climate warming comprises 8-11%.

Because natural variability, climate warming and direct evaporation are expected to increase with continued climate change, the assessment says that the solution must focus on human water use because it is the only element that can be changed in the near term.

In a virtual interview, State Rep.

10

SAVANNAH BURNARD

PHOTO BY BAILEY RIGBY

Dan Johnson said the Utah Legislature passed bills to help fix the problem. One of these bills is called Secondary Water Metering Amendments. This bill was put into effect on May 7, 2022, and imposes requirements related to metering pressurized secondary water.

However, Johnson said he recognizes conservation cannot be the only factor in solving the problem.

“Conservation is going to be the biggest savior for us, but we can’t just conserve our way to the end of this,” Johnson said.

The legislature passed another bill that was put into effect on March 21, 2022, called Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Program. This bill addresses the duties of the Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands related to the Great Salt Lake. Utah’s general fund gave $40,000,000 to the Department of Natural Resources for this program.

Rep. Scott Chew proposed another bill, called Utah Water Ways. This bill provides for the creation of a new nonprofit, statewide partnership addressing water. If this bill is passed in 2024, a one-time appropriation of $2,000,000 will be given to the Department of Natural Resources from Utah’s general fund, and they will receive an ongoing appropriation of $1,000,000.

While there are some laws set in place, and others that are starting to be put into motion, Johnson said it will take time.

“These are all really doable things, but they won’t be done by next Christmas,” he said.

Johnson said legislators pay a

lot of attention to the data they get from USU’s researchers. He said continuing to look at this information is one of the most important things legislators can do when they are determining ways to fix the problem.

“I don’t think there’s anybody in the state legislature that doesn’t realize that we have to fund these different types of scientific projects and look at that data and make sure it helps us,” Johnson said.

While policies to save the Great Salt Lake have to be put into effect by lawmakers, individuals can take action in their own lives.

Steed said it’s important to educate one another on how the Great Salt Lake benefits them as a society. One can learn about lake effect snow that provides better snowpack, the variety of ecosystem benefits that come off the lake and the fact that it covers up toxic elements on the lake bed and prevents them from blowing around.

“I think all of those things have helped people understand that if we lose the lake, we really do lose something very important to us,” Steed said.

Losing the lake is a real possibility. Belmont said if trends over the last few years continue, the lake could be lost within five years. He said people should plan for the worst case scenarios and stay away from wishful thinking.

“I have been really surprised with how many people are at least aware of the problem, but they don’t usually understand the real scope and urgency of it,” Belmont said.

He said it’s important for

individuals to email and call their representatives to voice concerns because legislators need to be held accountable.

“If representatives are getting lots of emails from people saying, ‘I want you to support this legislation,’ or ‘I’m just concerned about the Great Salt Lake and I need you to be keeping your eye on this and doing the right things,’ you don’t have to know all the policy to at least tell them that it’s a concern to you and you want them to solve the problem,” Belmont said.

There are also opportunities for individuals to get involved in the community. According to their website, The Nature Conservancy is a global environmental nonprofit that works to halt climate change and biodiversity loss. Individuals can donate to The Nature Conservancy, volunteer with them, attend live or virtual events and learn about ways to lower their own carbon footprint.

Another way for locals to get involved is through donating and volunteering with Friends of Great Salt Lake. According to their website, the mission of Friends of Great Salt Lake is to increase public awareness and appreciation of the lake through research, education, the arts and advocacy. The organization sponsors a variety of programs and activities to help achieve their mission.

“Even if you’re not a biologist, chemist, hydrologist, or anyone who is involved in this from a scientific standpoint, you’re a person with a voice, and the more voices that can be heard, the better our solution is going to be,” Baxter said.

Merino wool and heat mapping: Student recognized internationally for innovative design

Julie Lamarra, an assistant professor of practice in OPDD, mentored Dorrance while he researched, designed and created his base layer set.

CAITLIN KEITH PHOTOS BY HEIDI BINGHAM

Jack Dorrance, a Utah State University student from Chicago, created a base layer for endurance trail runners using thermal mapping of the human body. He designed a top and a pair of shorts that landed him in the top 10 of an international design challenge, earning him a trip to Munich, Germany.

Dorrance is a senior studying outdoor product design and development. He said he came to USU specifically for the OPDD program.

“I was reading an outdoor magazine, and they did a little bit of a report on the program because it was so cutting edge at the time,” Dorrance said. “I think they hadn’t even graduated their first class yet, because this is four years ago, and I just sent it and came here.”

Dorrance entered his design in the 2022 Woolmark Performance Challenge and was selected as a finalist.

The Woolmark Performance Challenge is a competition for design students that partners with a different company every year. Applicants are prompted to design something out of merino wool for a specific purpose.

Lamarra said the competition is unique because it is a global call. Students from all over the world can apply, as long as they are in a design-situated curriculum or a college program signed up as an affiliate of the challenge.

“Jack was really interested in it because the challenge partnered with Salomon as the main collaborator, and the design brief was to incorporate wool into a piece or pieces, head to toe kit, for high alpine ultra runners for a specific ultramarathon,” Lamarra said.

The ultramarathon design brief was based around the Tor des Géants, a 205-mile endurance trail race in Aosta Valley, Italy.

Dorrance focused on heat mapping of the human body and did his own personal research, approved through the USU Institutional Review Board, in order to create a pattern for his pieces.

“I created a paneling map based on the heat production of either the male or female body, then applied different thicknesses of Merino and different blends based on the amount of heat that was produced in that area,” Dorrance said. “So my whole goal was basically to create a base layer where all the heat released around that area was even and relative to the area itself, hopefully giving a hypothetical trail runner a more efficient and comfortable piece of clothing.”

12

Along with support from Lamarra and other professors in the department, Dorrance received materials from New Wool, a company based out of New Zealand. The company sent him three different blends of wool and gave him a discounted price.

The project took a lot of work, and sometimes, he was working in the lab until 3 a.m. Dorrance said he gave it all he had with the resources available — if he hadn’t put in the effort, he wouldn’t have been a finalist.

The project also required a lot of revisions. Dorrance said he completely redesigned his pieces three times.

Out of 1,200 submissions, Dorrance placed in the top ten. There were four finalists from the U.S., with others coming from the U.K. and Italy.

The finalists’ trip to Munich took place the week in November 2022.

“We did get to have a dinner with some big designers and people in the industry,” Dorrance said. “I’ve met people in person that I had only had the experience of following on Instagram, and seeing them in person was very validating. It kind of gave me the sense of maybe I had a shot to get where I wanted to go.”

Dorrance said the OPDD program at USU is one of the only programs of its kind in the U.S. There is a master’s program at the University of Oregon that is similar, but there are no other undergraduate programs like it.

Chase Anderson, the program coordinator for OPDD, said they offer a four-year undergraduate bachelor of science degree.

“We had a faculty member here who worked in the family consumer sciences department program. She had friends in the outdoor industry, and she recognized the need for a program to train the next generation of product designers for the outdoor industry,” Anderson said. “She had some initial conversations with people in the industry, and then put together an initial list of courses, and then presented that to the university and initiated the formal process to create a new program. So, at the time, there was nothing else like it. It’s the first of its kind.”

The program officially began in the fall of 2015 and has had four graduating classes.

“At its core, it’s a design program, focused on helping students learn how to develop physical goods,” Anderson said. “Everything from performance clothing to soft goods and equipment. We make anything that you can hold in your hand — physical products. But at the core of the program is sustainability and performance.”

Lamarra said there are three tracks within the program: product line management, design and development.

The first two years of the program are set up as a pre-professional program, with courses to help students familiarize themselves with all aspects of the three tracks. In the spring semester of their sophomore year, students can then apply for matriculation into the professional program for the last two years.

To apply for the professional program, students have to have received a C grade or better in all pre-professional courses. They also must submit a portfolio based on a rubric put together by the faculty.

13

“We review the portfolios as a faculty and then come together and discuss who’s coming into the professional program and what track are they going to be placed in for their last two years,” Lamarra said.

Lamarra said within each of the three tracks, students can narrow their focus even more to any genre within the outdoor industry. These focuses include watersports, snow sports, fishing, hiking and rock climbing.

“Once you get up to the upper division levels, you’re really able to diverge and really focus on what you came here for,” Dorrance said. “My focus was apparel-based.”

In the last two years of the program, students can take theory and creative courses, as opposed to the more technical, skill-based courses of the first two years.

“In these last two years, they also get a lot more face time with industry professionals,” Lamarra said. “I have really nice relationships and partnerships with industry affiliates that will actually come into our classroom for a few of my classes at midterm and at their final presentations and give critical feedback to our students.”

Dorrance is the first student from the program to enter the competition, but Lamarra said she knows of at least one student interested in entering this year.

“She’s going into it with, a very open mind in designing for this specific problem in this challenge, but it changes every year,” Lamarra said. “We’ll hope to get into the top 10 again.”

This year, the partnership is with Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli. Students will be challenged to create a uniform for a team that races high-speed yachts.

Anderson said Dorrance’s success with the challenge and his product is not only validating and important for him, but also for the program as a whole.

“It’s really validating — showing that we can compete,” Anderson said. “We’re training students who can have an impact and do something really meaningful. Upon graduation or even prior to graduation, it’s really amazing to see that what we’re teaching in the classroom translates, and it’s being recognized by people internationally.”

When Dorrance came to USU and started in the program, his goal was to end up at a design firm after graduation — to be able to solve problems and make life easier for people through his designs.

Because of the competition and the portfolio he has put together in his time at USU, Dorrance has a few prospects for design jobs after his graduation.

“I’m more than where I wanted to be,” Dorrance said. “I’m very dumbfounded. It doesn’t feel real, it is very crazy. Post-graduation, I’m hoping to work for a design firm or a design studio and really just doing that — going in every day working towards a goal.”

Lamarra said Dorrance’s success and example have encouraged other students within the program to work harder and set higher expectations for themselves.

“With someone like Jack who is really self-motivated and really wants to excel, he was willing to listen to my critique and to really hone into what I was saying,” Lamarra said. “He wasn’t afraid to ask questions and he went for it full on. He went for it. We’re not striving for perfection, we’re striving for excellence, and every time he came in, he was raising that bar of excellence up and up and up.”

14

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

EBLS encourages deeper understanding of Bear River Massacre

CARLYSLE

PRICE

PHOTOS BY ERIC J. NEWELL

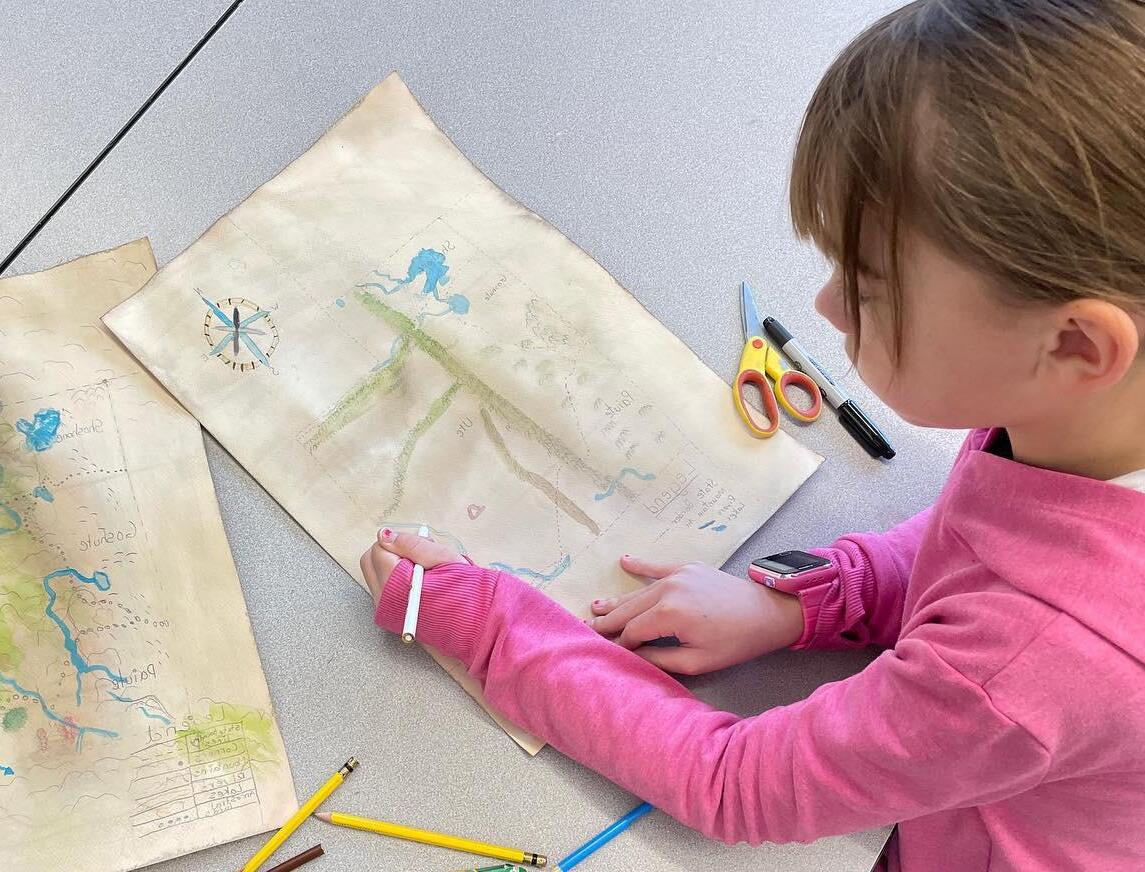

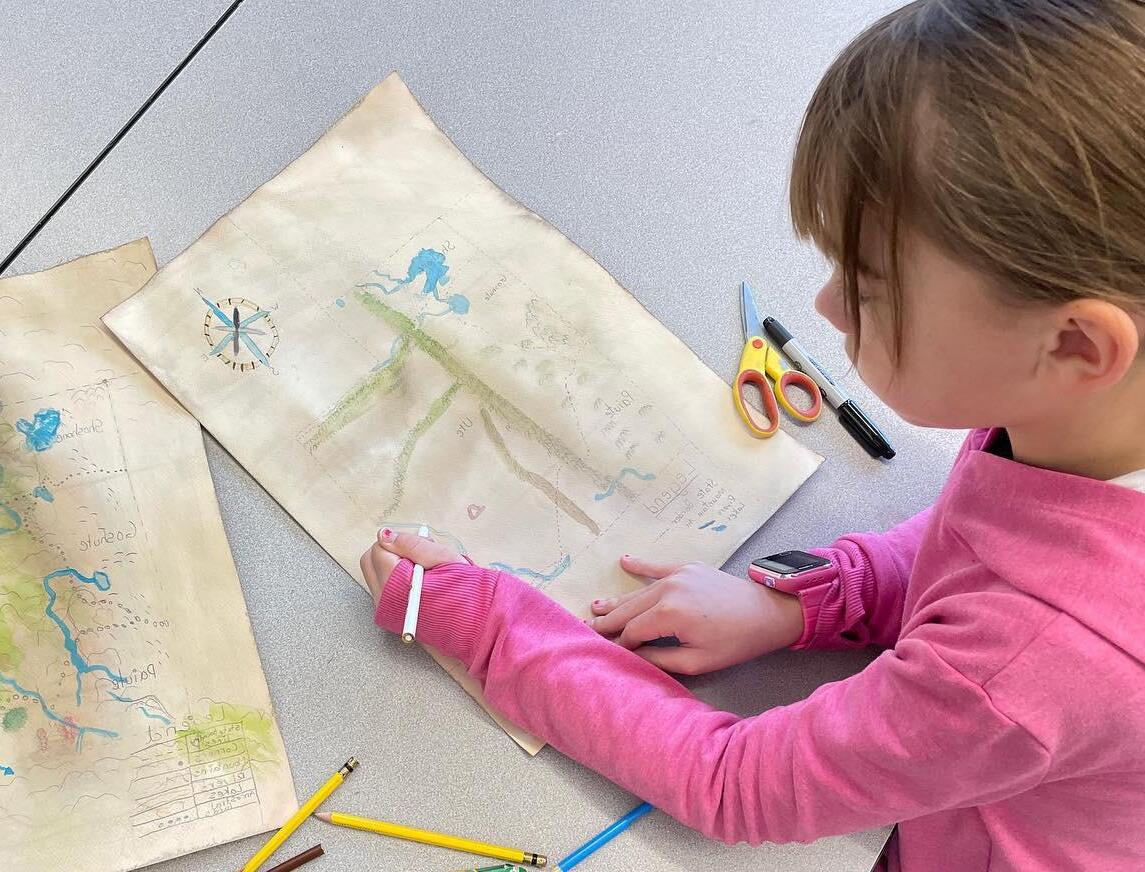

As I walked to the art room at Edith Bowen Laboratory School, art teacher Lisa Saunderson led me past a wall of poster-sized thank you notes to organizations in the community that had engaged with the students and bolstered their learning. The card on the very end was addressed to those at the Bear River Massacre site, written in red crayon.

Every year, fourth graders learn about the Bear River Massacre, an event that took place in presentday Preston, Idaho in 1863. Between 270 and 400 Shoshone were killed by the U.S. Army.

EBLS incorporated this history into the fourth grade curriculum about five years ago, teaching it within their classrooms and art programs.

Saunderson explained that in her unit, she made sure to include a mapping project that not only portrayed state lines, but also showed native territories as well — including those along the Bear River.

Likening it to plant zones and animal migrations,

she hoped to teach her students how native people moved throughout the land naturally with the seasons. Along with this, she encouraged students to add in memories they’ve had in different parts of the state.

“I want them to have that ownership and that experience, and then look at it in another lens of, ‘Who lived in these places originally?’ And think about how those places have been used,” Saunderson said.

Teaming up with the fourth grade teachers, a large effort was made to front-load students on what they would experience at the site of the Bear River Massacre — a field trip they embark on every fall.

Fourth grade teacher Mandy Seifert said she chooses to introduce the historical event in a way that students can relate to.

“I always begin telling them something that happened at recess,” Seifert said. “A kid hit another kid or something to make it personal for them and say, ‘Let’s say I only talked to Joe and didn’t talk to Sue too. What would that feel like to you?’”

She said the students were very passionate that they needed to hear both sides to make things fair. Then when the students understood this on a personal level, they were ready to start learning.

The teachers placed a special effort on preparing students in the beginning by familiarizing them with the Shoshone tribes. Before this introduction, most students didn’t know a lot about the Shoshone, let alone the massacre that took place a few hours north.

Fourth grade teacher Joel Lopez also experienced a lack of education on the massacre until he attended a Native American Student Council Event, where he was introduced to Darren Parry, former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation.

18

Lopez later read an article by Parry that evoked tremendous emotions upon learning more details of the tragedy. After a coworker remarked that people needed to “get over it,” Lopez made it a point in his curriculum to teach students both sides of the story. His goal was to bring awareness and humanity back to those who lost their lives, just as Parry’s writing had done for him.

Working with EBLS, Parry has acted as an expert guide on the field trip for years.

During the field trip, students are divided into three groups. One group listens to Parry speak about the history and experiences of the people. Another group makes an art piece while overlooking the scenery, and the last group works on writing a piece. The students rotate and have a chance at each station.

“When you start doing all three of those things, it activates your other senses, and I think greater learning takes place when you start incorporating all the things that they do,” said Parry. “They’re not just here to look and hear me talk, but they’re there to immerse themselves into it, interpret what they see. I’ve always been such a big fan of their program.”

Lopez said he prepares his students to seek out a greater understanding of a complicated issue and not to place blame on someone who was right or wrong.

Students proved their deep understanding in each piece of the field trip. One in Parry’s group was looking at the Honor Tree, a place where gifts and memorials are left for those who died. Spotting a mirror hanging from the branches, one fourth grader told her group that she had her own interpretation of its meaning.

“It means that it’s here to remind us that we did this and if we don’t learn about it, we can do it again,” Parry quoted.

Parry said no teachers corrected or agreed with the

student, but were in awe of the profoundness of the comment.

During the art rotation, students were taken to an overlook in Idaho where they peered down into the valley. Here they were able to see the land, including the hot springs that the Shoshone stayed by during the winter. They could see features like the shape and size of the river, the horizon and the mountains that Col. Patrick Connor ascended.

“I let them engage with wherever their interest takes them, but I do let them have moments,” Saunderson said. “We bring them to a place of empathy and reflection, and then engage with recording what they’re seeing through a lens that is already open and imagining.”

It was here that a student painted the scene to include cattle on all plots of land, except for one area that they learned the Shoshone had asked to keep sacred.

“That tells me, as a person interpreting their art, that it resonated with them,” Saunderson said. “We’ve gained understanding and deeper knowledge of the history and the story of the place.”

Lopez said for him, the writing portion that took place in the classroom afterwards was where the magic happened. Students returned from their journey and read journals and accounts from Connor and other pioneers from that time. It was then that students wrote their understanding of both sides and the complications that the event posed.

One student who originally didn’t understand the Shoshone at the beginning of the field trip wrote of his new understanding after learning more about the people and their way of life.

“The fact that they’re really thinking for themselves, and the teachers are asking them to put something down on paper, written and drawn, on your experience at the massacre site and start interpreting it for yourself,” Parry said. “I just think it’s such a big deal, and greater learning takes place when that happens.”

The curriculum and field trip surrounding the Bear River Massacre are evolving each year to bring more sides and details of the event. Students continue to learn, grow and even teach their parents.

Teachers hope that soon their program will allow students to return to the site each spring to help with the land restoration and the construction of a new visitor center.

19

Nature artists of Cache Valley: Capturing wild expression

HARRISON LARSON PHOTOS BY CLAIRE OTT

Cache Valley is home to many great artists who strive to capture the beauty surrounding them every day. From wildlife and sport painting to capturing the majesty of a landscape, the artists in the valley paint inspired glimpses of nature.

Joshua Clare and Luke Frazier are painters inspired by the natural world. While different in what they depict in their works, both have a deep appreciation for nature and create works inspired by that passion.

Joshua Clare, a painter based in Paradise, Utah, creates works inspired by the natural landscapes around him. Known for his still-life paintings, he strives to depict the world around him in meaningful ways.

Clare grew up in Salem, Utah, and spent much of his childhood reading, drawing and playing outside on his family’s farm.

“I read, I drew, I played outside a lot and I worked a lot with my dad outside. We had a kind of ‘play’ farm — he always wanted that — so I did a lot on the farm,” Clare said. “I rode horses and did all of the projects that go along with that.”

Clare said much of his inspiration for pursuing art came from the books and movies he watched as a child.

“So when I was little, it was ‘Calvin and Hobbs’ and the classic Disneys. I was in the era — I’m forty, which is amazing — but I was in the era of ‘Aladdin,’ ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’ and those signature Glen Keane drawings, and I want to be able to draw like that,” Clare said. “That is part of what sparked my love of drawing.”

Clare said that initially, he wanted to be an animator, but with the rise of CGI, he wanted to stay with physical mediums, which led him to painting.

“I knew that digital was the future for the movie industry — I knew that drawing was phasing out — and so I knew that wasn’t an option anymore, and I didn’t want to be on the computer to create traditional work and so I started exploring in the painting world,” Clare said.

Clare said nature inspires his art because it is the most beautiful thing people can experience.

“The epitome of beauty to me is nature, it’s the most beautiful thing that we know. I feel like there is more beauty in store for us, but that’s otherworldly — that’s to come — so the finest beauty that we can encounter as humans is God’s creation,” Clare said. “Why is nature so inspiring? Because it’s perfect. It’s so hard for me to imagine anything more beautiful than it — impossible, actually.”

Clare said nature is so beautiful because it is unified while still being full of uniqueness.

“Nature is a perfection of unity with unlimited variety, and I think that’s the best definition of beauty that I have come across, is unity in variety,” Clare said.

“The longer I live, the more that I think that’s true, just with people as well — with friendships or communities — it’s more beautiful when you get a variety of ages and occupations, and every way that you can make a human different: race and ethnicity, and gender and social status, and education. You can get a huge group of people to get together and have them unified in spite of all that variety. It’s unbelievably beautiful, and that’s what nature is. It’s this perfect harmony with unlimited variety.”

Clare said moving forward, he wants to create paintings that don’t just depict nature, but express the feeling of nature.

“I crave — I want desperately — to paint stuff the way it feels and not just the way it looks. To move from essays on nature to poems on nature,” Clare said. “The difference between a song that tells you everything and that you can’t engage in, and a fine piece of classical music that takes you wherever you want to go.”

Clare is a passionate artist who continues to develop and express his style with his paintings, creating beautiful landscapes built on nature’s harmony as well as portraits using the same principles. You can find more of his work and contact him at joshclare.com.

20

Luke Frazier, a graduate of Utah State University with a bachelor’s degree in painting and a master’s degree in illustration, creates works inspired by wildlife and outdoor sporting.

His paintings depict animals everywhere from Alaska to Africa. Based in Cache Valley, he has been creating works for over three decades.

In a virtual interview, Frazier said while growing up in the Salt Lake area, he enjoyed spending time outdoors and hunting and fishing with his brothers, activities which have had an influence on the work he paints now.

“I was always outdoors — always in the hills, always fishing every creek we could find, trapping with my brothers, doing snow sports, but it mainly had to do with hunting and fishing. Always, all the time,” Frazier said. “It was a pastime we enjoyed, and provided for our large family that way as well. And that’s probably why I paint wildlife and sporting art because it’s the life I’ve lived since the beginning.”

Frazier said he gets his inspiration from nature because it drives home a sense of nostalgia.

“It’s a departure from all the craziness that’s in the modern world,” Frazier said. “From the very beginning, it has more of a nostalgic take in my art — the older times, where it was subsistence living.”

Frazier said inspiration from

animals also helps drive his art.

“Just around the animals, the wildlife, or just trying to find them in the landscape — once you’re in it all the time, it’s just… I can’t explain it, you don’t want to be anywhere else,” Frazier said.

Frazier said his process for creating art is very natural. He takes inspiration from what he sees around him and designs his painting around that.

“It’s pretty organic. I get inspired by many things, and being outdoors is the biggest one,” Frazier said. “Going to museums, seeing art, seeing how other artists attack a problem or solve a problem, or portray what they have going on in their mind — just gathering information. Seeing paintings in my mind everywhere I go — I take a lot of pictures of rocks and trees, and little aspects of those find their way into my paintings.”

Frazier said he very rarely sees a perfect scene to paint. Instead, he tries to compose a scene.

“Very rarely do I find a perfect scene for a painting. I try to judiciously edit the information in front of me, and then I decide the subject matter, trying to gain as much reference material as I can to make a complete scene,” Frazier said. “I don’t just want to compact as much as I can into a scene. It has to be beautiful, it has to flow.

It has to say something, it has to mean something.”

Frazier expressed his appreciation for the fine arts department at USU, saying it helped him create a way for him to create his art and make a living.

“I was very lucky, I had very quick success in the fine art world. I fought against the fine art teachers, and I would argue with the illustrators. Adrian van Suchtelen was like, ‘You want to paint deer under a tree in front of a lake!’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, that’s what I want to paint,’” Frazier said. “They said, ‘Are you going to be an artist or an illustrator?’ There was a big separation there that I thought was unnecessary because I thought one fed the other. I always used the saying, ‘I’m sure Michelangelo was paid to paint the Sistine Chapel, so isn’t that kind of illustration?’ But I don’t think that there is really a separation between the two, the goal is to strive to understand your medium and your subject matter.”

Frazier continues to be inspired by the great outdoors. You can find his works and contact information at lukefrazier.com.

21

USU’s Beaver Ecology and Relocation Center featured on TV show Dirty Jobs

AVERY TRUMAN PHOTOS BY LIZ HADFIELD

Season 10, episode 8 of “Dirty Jobs,” a television show starring Mike Rowe, aired on Feb. 5 2023. The episode walked through how Utah State University’s Beaver Ecology and Relocation Center ethically rehomes nuisance beavers for environmental benefit.

Becky Yeager and Nate Norman are the sole two employees of the center. They said they were excited to share their program’s mission with the world through the show.

“Mike Rowe was the main character, and I was his sidekick,” Norman said. “We don’t know how they came across us. At first, an email came to Becky, who I work with, and she thought it was a joke. She didn’t actually believe it.”

Norman said he would consider working with beaver relocation a “dirty job,” but also a fun one.

“I’ve been a wetland consultant my whole life, and so I’ve worked in swamps and wetlands,” Norman said. “So, it just doesn’t seem any dirtier than it used to.”

The center creates Beaver Dam Analogs — artificial beaver habitats that aim to provide shelter and imitate natural beaver dams as closely as possible.

“We build a BDA, so a fake beaver dam,” Norman said. “That’s to, you know, create some immediate habitat for the beaver to be able to hide and kind of figure out what’s the new situation.”

To create a suitable home for relocated beavers, the

team must start with sticks and mud to create a dam.

“We’re all in there, you know — buckets of dirt, and cutting sticks and throwing it in the river,” Norman said. “And it’s like a kid playing in the mud. It’s super fun and super dirty.”

Becky Yeager, the volunteer coordinator for the center, manages about 25 volunteers yearly.

“I believe in the program,” Yeager said in a virtual interview. “I’m in love with the beavers.”

Yeager said that taking nuisance, problem-causing beavers from public or private property is a very important job in the West.

The center works with the Division of Wildlife Resources and the Forest Service to find areas of land that need repair and restoration. The DWR also helps manage and conserve wildlife populations throughout Utah

“At first, we try to work with those entities to resolve the problem,” Yeager said. “But if we can’t, we’ll remove the beaver and take it to the facility where we’re required per DWR guidelines to quarantine it for three days.”

While quarantined, the beavers are kept in special

22

areas with access to both water and dry ground.

“During that time, we try to bring in the other family members, because they’re going to have a much better chance of relocation if we can pull them together as a family,” Yeager said. “They have really tight family bonds.”

Yeager said the center’s volunteers are an important part of the relocation process.

“The three days that they’re in our care, though — it’s really critical that we, you know, keep them as healthy as possible,” Yeager said. “And that’s where our volunteers come in.”

Kelly Bradbury, a professor of geology at USU, has volunteered at the center for two years.

“When you arrive, the first thing you might do is check the temperature of the kennel,” Bradbury said. “Just to make sure it’s OK, and to see if there’s any problems.”

Bradbury said the volunteers go through the process of cleaning the kennels, replacing swimming water, refilling food, and checking the animals’ health.

“You might also take water samples, depending on if there’s any research going on with other scientists at USU,” Bradbury said. “Sometimes we save some of the sticks for DNA testing.”

According to Bradbury, the volunteers use an app to report the conditions of each beaver to Yeager.

“Last year it was a lot tougher because our water spring that we had — our irrigation spring — just stopped flowing,” Bradbury said. “So we had to haul in water every day, and usually Becky and Nate did that as employees of BERC.”

Despite the challenges, Bradbury said the volunteers and staff are very respectful to the beavers and their space.

“There’s a really strong effort to be as quiet as we possibly can, and not to talk or yell, to just try to be gentle in our movements, and move slow,” Bradbury said. “We don’t touch them. The only time they’re touched is during the processing, like when they come into the facility.”

According to Bradbury, in the past, beavers were nearly eradicated through hunting in Cache Valley. Bringing beavers back to the area positively affects the watershed.

“As they put in their dams, and they fill the streams, then it allows water to back up and fill the sediment, and it allows the channel to become more complex,” Bradbury said. “That allows plants to come in, and as the plants come in, then more wildlife that rely on those plants can come in, and it just starts to widen and spread into the floodplain.”

According to Bradbury, some of the positive impacts are recharging groundwater, healing the watershed and rehydrating land.

“But the heart of it is to kind of be able to participate in something that’s more actively working towards

23

mitigating the impacts of climate,” Bradbury said. “To kind of rehydrate watersheds seems like a very important thing, especially in the West.”

According to Norman, bringing water back to higher grounds is becoming increasingly important.

“It’s become a lot more important recently, due to climate change and drought, and so it seems like it is a field that is just exploding,” Norman said. “There’s just a lot of interest, a lot of momentum. And so if you were looking for something to research or get involved in, I think that it’s a great opportunity.”

Bradbury said volunteering at the center has been very rewarding. Volunteer work can usually only be done in the summer because moving beavers from their homes in the winter can be fatal.

“We have a pretty core group of close volunteers,” said Bradbury. “All of us that work with the beavers sort of see them in action as being very communityoriented.”

Liz Hadfield has volunteered at the center for three years.

“It’s been the most educational and fun project I’ve been involved with,” Hadfield said in a text message. “Not only are the beavers amazing, but I get to meet amazing students and instructors to make it double the fun.”

Hadfield said before her time at the center, she enjoyed searching for beavers in the wild.

“I really love that this program is giving the beavers an extra chance to do what they were meant to do,” Hadfield said. “Watching them be released and swimming right into the new handmade dams was very rewarding. The beavers immediately started to redecorate and make it more homey.”

Norman said his favorite part of the job is the beaver releases.

According to Hadfield, one of the areas where beavers were introduced is now thriving. The beavers have created a “drinking oasis” for other animals.

“We have kept close contact with the farmer from Grouse Creek and he is so happy with the progress the beavers have made to his farm and helping his cows have more access to water,” Hadfield said. “Some thought they were destroying their land. This has been proven over and over to be incorrect info. So happy many people have done the hard work and studied to correct this.”

Hadfield said she ensures the beavers become Aggie fans before they are released back into the wild by

decorating the facility with USU-themed decorations.

“I’m sure they are raising their posterity to be true Aggie fans,” Hadfield said.

Jay Wilde is a beaver relocator in Idaho and a longtime friend of the staff at the center.

While there are some negative factors to having beavers around people, Wilde said those things can be alleviated.

“In certain situations, they can cause problems,” Wilde said in a virtual interview. “There’s ways to mitigate most of them.”

According to Wilde, beavers help vegetation to become more resilient.

“Once you learn the benefits of these animals, you know, it’s a no-brainer,” Wilde said. “That’s the key, is an education.”

Wilde said beavers fundamentally change the biodiversity of the land they inhabit.

“They’re a keystone species,” Wilde said. “They have a tremendous impact on a lot of different critters.”

24

https://studentmedia.usu.edu @utahstatesman @aggieradio check us out . the student voice.

Surf culture extends beyond the coast establishing roots in Utah

LEAH CALL PHOTOS BY SAM WARNER

Thaddeus Nicholls is many things. He’s a Cache Valley native, father of two, sourdough bread baker, surfer and surfboard shaper right here in Utah.

“I’m just some weird dude building surfboards in a landlocked state,” Nicholls said. “I don’t know how seriously people take me when they hear I’m a surfboard shaper, but you know, I actually do know what I’m talking about sometimes.”

Surrounded by surfboard blanks and Florida license plates, one could almost imagine they were in a beach shack right on the coast rather than a workshop in the dead of Utah’s winter. Nicholls runs his surfboard shaping business, Slide Theory Surf Craft, out of that workshop.

Nicholls shaped his first board in 2011. He got into surfing after earning his master’s degree in coral-reef ecology and marine sciences. He was doing marine work and was under the mentorship of a colleague in New Smyrna Beach, Florida. There he learned to shape surfboards.

“He was making boards for me for several years and I totally fell in love with surfing in general,” Nicholls said. “And then the whole idea of building a surfboard and riding your own equipment, that kind of thing, sounded really cool. I would always stop and watch Randy working on my boards and I just liked being there. So I started, just for fun, doing ding repair and finally got the courage up to ask Randy if he would take me under his wing and mentor me a little bit and teach me how to shape boards. He did and the rest is history. I dove in headfirst and went with it, you know?”

While giving a demonstration on his shaping process, he explained if he had nothing else to do with his time, he could crank out a board in three to four days. However, Nicholls has a full time job as a program coordinator for the Utah State University Ecology Center.

The process of making a board begins with a blank, which is foam used to create the core of the surfboard. Some are split down the middle so it can be glued with a stringer — a strip of wood that runs from the nose to the tail down the center of the blank.

From there, the blank is “skinned,” or passed over with a planer tool. Skinning means doing a really thin pass with the planer to take the skin off. Respiratory protection is worn from this point on. Rocker templates are used to shape it. The template is screwed into the side so the board is curved when the outline is sawed out.

“I always start on the bottom of the board — working on the contours of the bottom first, then you flip it over and cut your rail bands in, so you’re cutting off bands at a time with your planer to make bevel edges. You just make more and more bevel edges until you get a curved surface and can blend everything,” Nicholls said.

The rail bands control the way the surfboard responds in the water. Once the rail bands have been cut, the board needs to be sanded to make it smooth and even, before installing the fins. Nicholls said he will run his hands over the board to test that it’s ready to go.

“Some people call it the Stevie Wonder or Ray Charles test,” he said. “You just close your eyes and feel the board with your hands when you’re done. Feeling the different parts of the board end to end, and you develop and get to a point where you can feel if one side is thicker or if it’s good to go.”

Following the installation, the board is glassed with fiberglass and epoxy, and is a finished product.

“I like messing around with weird tail shapes,” he said. “I mean, I’ll build someone anything they want, but if I get artistic license for somebody and they don’t give me any direction other than a color palette, that’s when I do my best work because I will geek out on it.”

26

Nicholls’ boards are shipped all over the country, including Florida, California and New York.

“I love doing it,” he said. “I mean, I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t love it. It’s a dirty, disgusting, filthy job, if you can’t tell by looking at the shop. But you know, you have to love to do it. Just like surfing.”

Nicholls and his family moved back to Cache Valley during his wife’s second pregnancy.

“I was writing grant proposals to keep myself employed for like four years,” he said. “It was just time to move. You know, we got pregnant and it was like, okay, I need a big boy job with benefits. I don’t have any regrets moving back here. I miss surfing of course as much as I used to. But I still get in the water when I can. I still get in and paddle around, but I’ve definitely lost my edge. It’s a horrible wakeup call every time because it’s not like riding a bike. If you’re not doing it, you’ll lose it.”

When it came to deciding the name of his business, Nicholls said there are similar names for board shaping businesses out there, but he decided on combining surfing itself with the concept of creating your own board.

“On Slide Theory Surf Craft, the whole idea is that when you’re designing a board there’s designs that are tried and true, but I don’t like shaping conventional stuff,” Nicholls said. “I like experimenting and trying different things. So slide — you’re sliding on the water, you’re planing out, and the theory behind it is tinkering with new designs and trying new things just to see if they’ll work. You check it all out on my Instagram. The handle is @thebeesaredying.”

For more information on Nicholls or surfboard shaping, go to slidetheorysurfcraft.com.

During the winter months, Nicholls’ focus shifts to snowboard and ski repair. There is less work in the wintertime, he explained, as it’s hard to work with resin when it’s cold; it becomes super thick and hard to set up. So he spends time tuning up skis and snowboards and even gets up the mountain a bit himself.

“It’s a blessing being here and being able to snowboard,” Nicholls said. “After sliding sideways on a surfboard for 10 years, making the transition to snowboarding was nice. I have no regrets. Riding the backcountry in deep powder is the closest thing I’ve found to fill the void of surfing.”

Others in Cache Valley use snowboarding as a close second to surfing as well.

USU surfer and student, Michael Worley, said surfing takes a lot of work.

“I like being able to know I can catch a wave. It’s a cool feeling to pick up speed and be in the ocean,” Worley said.

Worley said snowboarding and surfing are different but fill each other’s void.

“With snowboarding, you can find an edge faster, but in surfing it’s harder to find,” he said. “With surfing, there’s a more volatile start. You could catch a wave or you won’t, and with snowboarding you’re always going to make it down the mountain, you know?”

Others fill the surfing void by wakesurfing during the warmer months.

Former USU student Olivia Moorhouse is an avid wakesurfer who can’t get enough of the water.

“I got into wake surfing through some friends. They took me out and just kind of threw me in the water,” Moorhouse said. “There’s something special about being out on the waves and being one with the water. The hardest part about it, honestly, is not giving up on it. Because when you first get out there, you’re not going to be good. You can maybe get up but it takes a minute to find that sweet spot. You will fall, so you just have to keep going with it but I love it.”

27

‘It’s not about me’ Cache Valley nonprofits

JENNY CARPENTER

PHOTOS BY PAIGE JOHNSON AND BAILEY RIGBY

Common Ground Outdoor Adventures

When Alex Ristorcelli skis, he doesn’t ski alone. Instead, he manages two tethers attached to a sit ski, where he helps one of his long-time clients, a military veteran. A nurse with several doctorates, she hasn’t been able to ski independently due to dislocation risks — until Common Ground Outdoor Adventures stepped in.

Ristorcelli, the nonprofit program director, said he watches the nurse’s head tilts to know when to turn; he then directs the tethers and moves her sit ski. But Ristorcelli said that mostly “she’s in charge, and I’m just following.”

What first was an AmeriCorps VISTA project became a nonprofit that now serves “well over 3,600 people with disabilities annually” with adaptive sporting equipment, Youth Adventure Leadership Programs and service to U.S. military veterans with disabilities.

Ristorcelli said he could tell several stories about “people who grew up skiing and for some reason or another, couldn’t ski anymore — and getting them out on the mountain and seeing a 55-yearold, 60-year-old man tearing up about being back on the snow.”

Just as Common Ground has supported thousands of people, several college students have supported the nonprofit. From volunteering a few hours a week to standing for 10 hours in front of Smith’s collecting donations, Ristorcelli said that Utah State University students have stepped in on several occasions to help.

But Ristorcelli also wants student volunteers to see that providing sporting opportunities for individuals with disabilities gives “a glimpse into something that we don’t get to see, that most of the population doesn’t get to see every day.”

“It’s not about me; I am not doing it for my own memories or anything else. I love to get to know every single individual for who that individual is and figure out how to work best with them to get them to enjoy the outdoors in the best possible way,” Ristorcelli said.

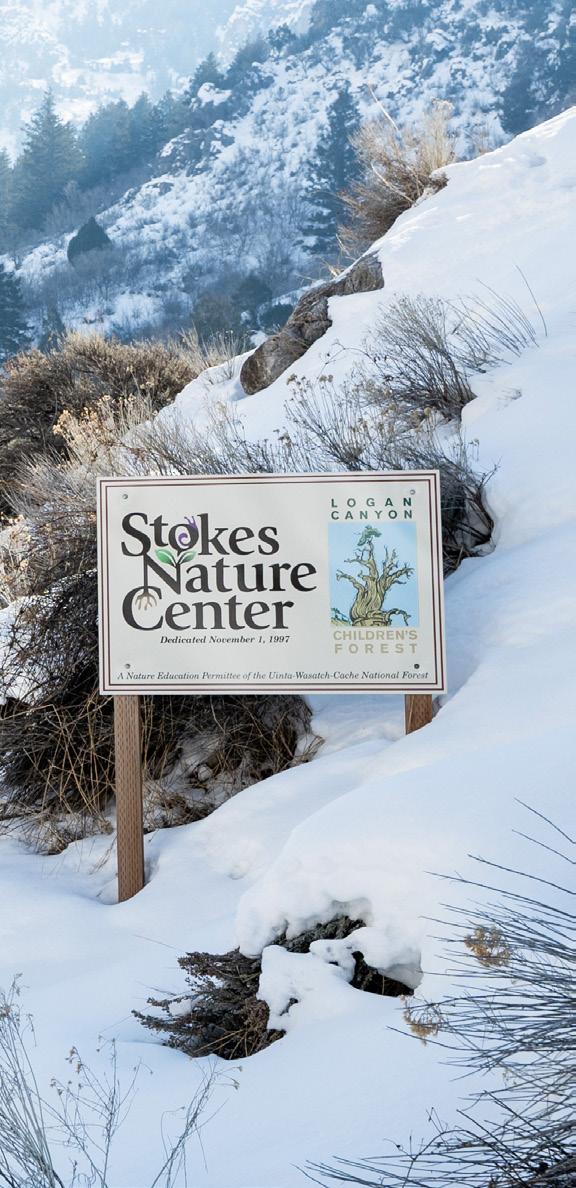

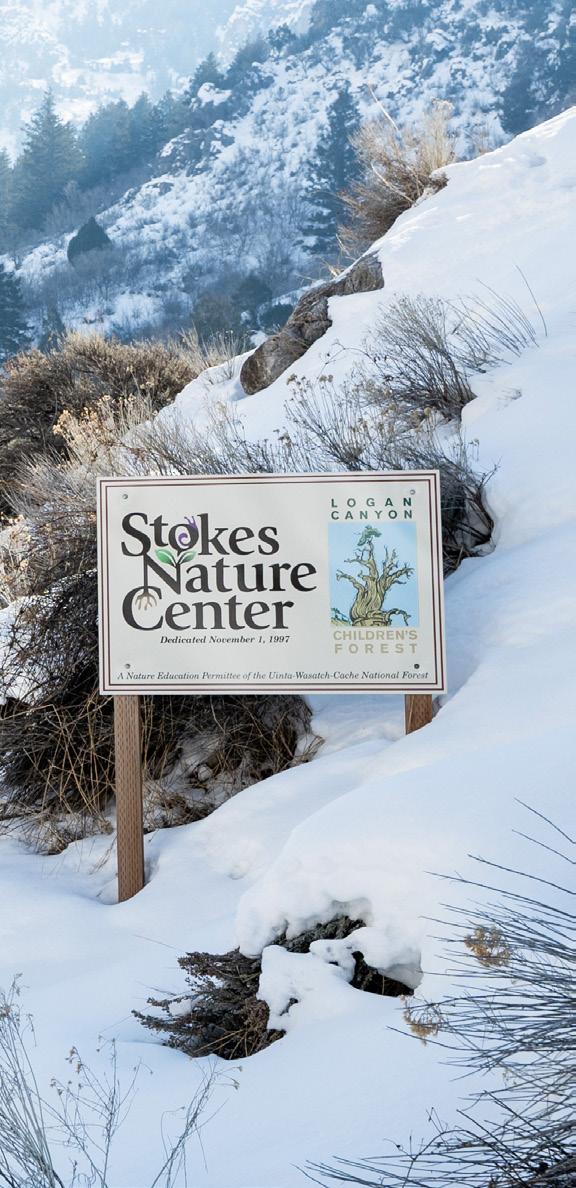

Stokes Nature Center

Allen and Alice Stokes Nature Center’s mission, according to Executive Director Kendra Penry, is cultivating outdoor education and exploration. From school programs, to summer camps to field trips, Stokes provides children of all ages with snowshoe hikes, avalanche education, ecological appreciation and more.

“We know that if people are exposed to nature and know how to care for it, they’re more likely to do so,” Penry said.

The nonprofit started in 1997 and, according to Penry, has made several adjustments since then — including programs featuring cultural awareness and education. Every Friday, once a month, the center will have a “monthly Kenyan adventure,” where USU professors come and discuss their research on worldwide wildlife.

Stokes also plans on having a day for Utah Chinese history. Penry hopes this will connect the world to Cache Valley.

“We want to make sure that there is an entry point for every person to feel welcome in the natural world,” Penry said.

According to Penry, Stokes will continue to have big plans for 2023 — mainly, to create a fully accessible exhibit for those with visual or hearing impairments. The center also plans on expanding their education programs to accommodate school children on waitlists.

“There’s always a lot of new things, simply because we’re constantly learning. The world around us is changing. Our valley is growing, and we have to grow with it,” Penry said.

28

Pour Overs with a Purpose

As Kylie McMorris trekked across the field to her job — which happened to be at a Kenyan orphanage — she heard a baby shrieking. As she walked towards the sound, she saw a baby squirming underneath a tree with a note written in Swahili that said, “I cannot afford to take care of her. If I keep her, she will die.”

While she hoped the orphanage would take the child, it was too full. McMorris eventually found another orphanage to take the baby, receiving several updates on her until she saw a Kenyan couple adopt the child.

“I realized after that whole experience that if mothers were just given resources and options to keep their children, maybe there would be less kids being abandoned, less kids growing up in orphanages without the love they deserve, less kids being left on the streets and starving to death, less kids being trafficked from their homes,” McMorris said in an email.

That’s when Pour Overs with a Purpose began.

With the US-based nonprofit, McMorris sold coffee and received enough donations to fund “Kumbatia,” a Kenyanbased nonprofit that would give childcare services to mothers that were working or in school. Since 2021, Kumbatia has helped

over 70 families, according to McMorris. One mother came with four malnourished kids — and now, after a year and a half of Kumbatia’s care, the children are “well nourished; they are excelling in school, and they are all so happy.”

By employing only Kenyans, Kumbatia empowers women and families to have sufficient housing, schooling and nutrition, McMorris said.

Most Cache Valley residents can help right from their own home, according to McMorris. Some donate through their website, and others make Venmo requests to @pouroverswithpurpose. Some personally sponsor babies or children in school.

Cache Valley Center for the Arts

The Cache Valley Center for the Arts doesn’t just build the audience — they build the performers, according to Wendi Hassan.

As executive director of the nonprofit, Hassan said the center is special not just because of its performances, but because of the way they can educate their performers in affordable dance, theater, singing, piano or visual art classes.

“One thing that is unique for the Cache Valley Center for the Arts is the depth of its usage to the community,” Hassan said. She also noted that every year, the center has 100 performances in the Ellen Eccles Theatre, 2,000 art classes and 111,000 people that would walk through its doors.

And with the theater’s 100th anniversary in 2023 — having originally opened to show movies and local shows — it’s not slowing down its pace of performances.

According to Hassan, the theater hosted a centennial celebration. This included dance performances to honor its humble, local beginnings, a movie night to celebrate its past film showings and, on the final night, Grammy award-winning artists Marc Cohn and Shawn Colvin will perform.

However, having these special performances does not come without its challenges. One of the nonprofit’s biggest struggles is when third parties sell inflated ticket prices.

“We sacrifice to keep our ticket prices affordable,” Hassan said. She encourages her consumers to purchase tickets through the center itself — and not through a separate seller.

29

Utah Avalanche Center

When asked how the Utah Avalanche Center saves lives, Paige Pagnucco, UAC’s Avalanche Awareness program manager, chuckled, saying that there are “thousands of decisions that are made on a daily basis based on our forecasts that actually keep people out of trouble.”

A nonprofit established in 1989 with the U.S. Forest Service, the UAC is “responsible for the majority of avalanche awareness and education in Utah,” according to its website.

“We have a whole curriculum that we go through,” Pagnucco said, explaining how the UAC teaches those interested in backcountry recreation about recognizing avalanche terrain, measuring slope angles and reading the UAC forecasts.

According to Pagnucco, many natural avalanches come as a result of sudden weather or temperature changes, but there are still other human-caused avalanches. Because not every UAC staff member can be in the field when an individual is in crisis, teaching self-rescue is paramount, Pagnucco said.

To better raise awareness of UAC and its programs, they worked with the Utah State Legislature in 2019 to officially recognize the first week of December as Avalanche Awareness Week.

During Avalanche Awareness Week, the UAC brings its partner organizations (such as WNDR Alpine) and search and rescue groups to Sugarhouse Park in Salt Lake City, where they invite the media to provide education beyond the valley, according to Pagnucco.

“We try and bring in all aspects from the avalanche world to show the public just what resources are available to them in terms of avalanche safety, avalanche education and avalanche rescue,” Pagnucco said.

Nordic United

When Rex Davidsavor began working with Nordic United in 2012, he didn’t expect he would become president of the nonprofit in October 2022 — but he was ready to help in any capacity.

The nonprofit provides education on caring for Utah trails, crosscountry ski classes and races, as well as their own trail grooming services to cultivate the best winter recreation environment, according to Davidsavor and Nordic United’s website.

Nordic United focuses on a few trails: one in Smithfield Canyon and a couple in Green Canyon, Davidsavor said. One trail in Beaver Bottoms is for skating and classic skiing, while others draw snowshoers, cyclists and others looking for outdoor adventures.

Volunteer trail trimmers and groomers help smooth the trails

by working with the National Forest Service to remove rocks, trim down trees and restore the road systems in place. But perfecting these trails is no easy task, according to Davidsavor.

“Most of the grooming is done in the dark, so we want to groom in the coldest part of the day, and not the warmest part of the day. Most groomers are up there anywhere from midnight to 5 a.m.,” Davidsavor said.

But such hard work pays off, according to Davidsavor. In fact, on Jan. 21 2023, the nonprofit hosted its fifteenth Crowbar Backcountry Ski Race — which ended up having a hundred participants from across the state and nation because of Nordic United’s supporters and volunteers.

“This community is really good for supporting nonprofits in lots of different areas,” Davidsavor said.

30

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

I believe that we should consider ourselves a part of the environment, the land, the communities of rivers, the animals, birds and the plants. ALICE STOKES

— FROM THE HERALD JOURNAL

highlandermag.com

— Maya Mackinnon

— Maya Mackinnon

AVERY TRUMAN PHOTOS BY BAILEY RIGBY

AVERY TRUMAN PHOTOS BY BAILEY RIGBY

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER

PHOTO BY SAM WARNER