20 minute read

COVER STORY

A Mix of PRACTICES

Advertisement

VETERINARY MEDICINE AS DIVERSE AS THE DOCTORS WHO PRACTICE IT AND ANIMALS THEY TREAT

Helping sick animals is what veterinarians are trained to do, but what happens when a problem is too complex to be solved in a clinic? Dr. Glen Esplin specializes in pathology and saw an opportunity 35 years ago to provide back-up for veterinarians helping animals with unfamiliar diseases.

Growing up on a ranch on the border of Utah and Arizona, Esplin loved working with animals and developed a curiosity for animal diseases at a young age. He started school in St. George, Utah, at Dixie College then finished his pre-vet degree at Utah State University. After finishing veterinary school at Colorado State University, Esplin practiced veterinary medicine for a few years before joining the U.S. Air Force toward the end of the Vietnam War. During the war he worked in public health, food, and sanitation inspections, but his favorite job was taking care of the patrol dogs.

After the war, Esplin continued is his education at the University of Utah and earned a Ph.D. in experimental pathology. He went right to work and helped open a veterinary division in the Associated Regional and University Pathologists (ARUP) laboratories.

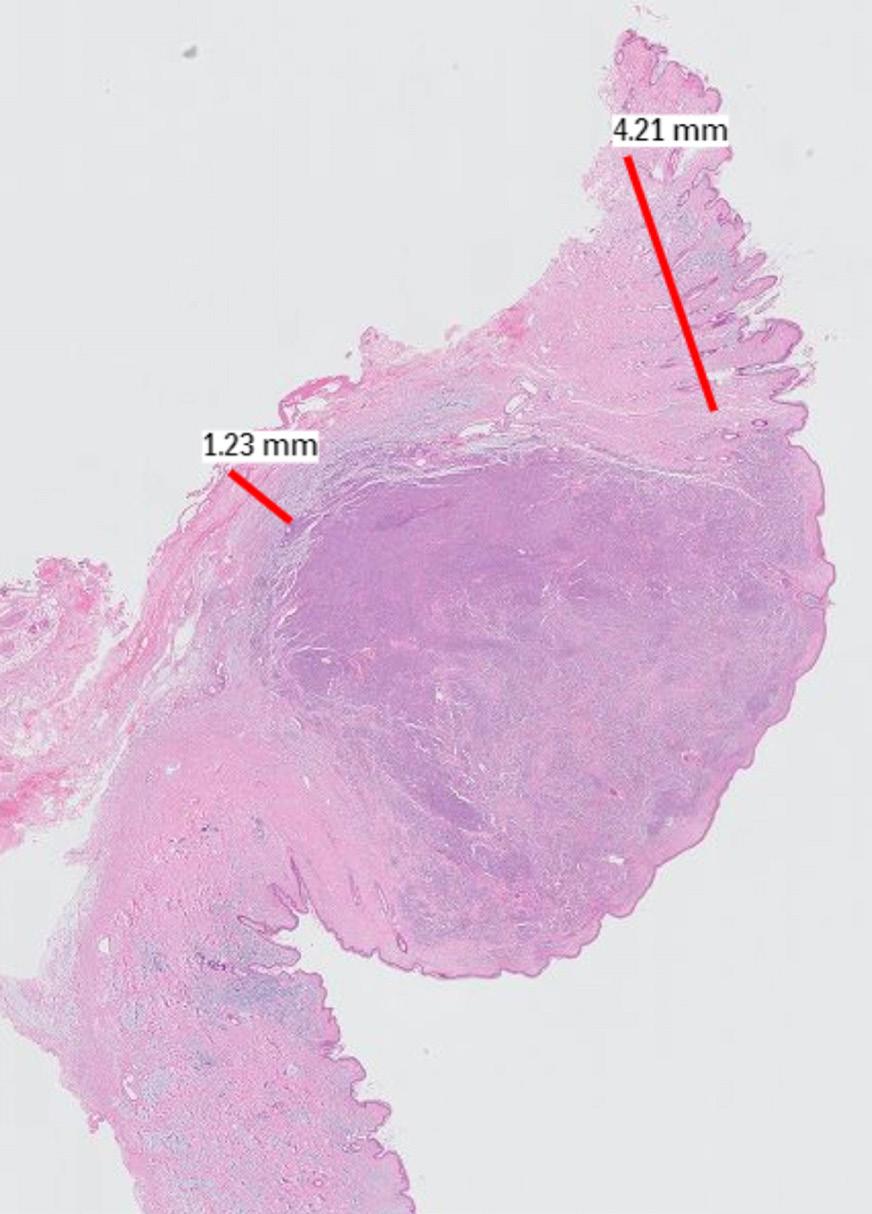

“We have this interaction with veterinarians who are out on the front lines treating animal patients, but we are their back-up,” Esplin said. “If they need to know if a lump or a bump is a tumor or cancer, they cut it out and send it to us so that we can get the results back to them in the same day.”

Esplin usually works with samples from familiar animals like cats, dogs, and horses. However, seeing close to 50,000 cases a year and samples from around the world, Esplin has worked with tissue from pen

guins, polar bears, and diagnosed fungal diseases from tropical climates.

“You have to try and stay at the edge there and always keep learning,” Esplin said. “We’ve been in this so long we think we’ve seen everything, but almost every week we see something that we’ve never seen before. There is always something new like a little variation of an old disease.” Contributing to veterinary medicine under the microscope and sharing that knowledge of animal diseases with veterinarians is what Esplin enjoys the most. Toward the end of his 25 years as director of the laboratory, Dr. David Gardiner came through the program as a student. When Esplin decided to serve a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Gardiner and his family purchased the laboratory and moved it to another location in Salt Lake City and it became a private business: Animal Reference Pathology (ARP).

Unlike Esplin, Gardiner grew up in the would go over it with me.” Gardiner said. “That just reaffirmed what I was doing, so I left vet school and went straight into pathology. I fell in love with diagnostics.”

After Gardiner finished school, he worked for a large pathology lab to gain experience. Gardiner always had an en

Gardiner knew providing all these services in a small lab was a huge responsibility, especially because he wanted to provide high-quality work.

Gardiner said there were two main labs in the country that veterinarians use for veterinary diagnostic needs, and

“You have to try and stay at the edge there and always keep learning. We’ve been in this so long we think we’ve seen everything, but almost every week we see something that we’ve never seen before. There is always something new like a little variation of an old disease.” - Dr. Glen Esplin

avenues of Salt Lake City, but wanted to be a farmer. He started veterinary school, but decided he didn’t want to practice in a clinic. Before Gardiner changed his career path, he decided to look into non-traditional pathways in veterinary medicine and narrowed the choices down to pathology.

“At that time, I applied for an externship when this division was part of ARUP and came out and spent a summer with Dr. Esplin. He would give me cases, I would try to figure them out and then he trepreneurial twist in his personality, so when he heard the ARUP lab was for sale in 2013, he took the opportunity.

“In concept I knew what is was but when you own a business, it’s really different,” Gardiner said. “It took us a year to understand what we bought and to get to know the clients. Then it took another year to put our own spin on it and how we wanted to see it. In the third year we decided this is where we wanted to go.” The ARP lab performs biopsies, cytology and pathology, including blood work. he wanted to be the third one. Gardiner knew that in order to compete with the larger, more established labs he would need to innovate.

When samples come to the lab, case numbers used to be written by hand on the glass slides. Gardiner knew that one slip-up with a number could cause cases to be mixed up, misdiagnoses could be made and time would be lost. Now ARP uses a bar-code system to organize and identify cases. As the lab became more efficient, more samples started pouring in.

More pathologists to lighten the load were hard to find because the field is so specific, according to Gardiner. Not only are pathologists hard to find, they can’t always move to Utah. To solve the dilemma, a photo is taken of each sample under the microscope and sent by email to ARP pathologists in Fort Collins, Kansas City, Toronto, and Boise. When it came to mailing samples for bloodwork back and forth, time was still an obstacle.

“We continued to do blood work and that eventually led us to open a second lab in Louisville, Kentucky, as a separate business with other partners,” Gardiner said. “ARP is now a provider for that second lab based in Louisville because that is United Parcel Service world headquarters. Now we can compete on turnaround time for anywhere in the country for most basic aspects like complete blood counts and chemistries, etc.”

Gardiner said he is happy with the direction the lab is going and is even surpassing the efficiency of human labs.

“If you do a biopsy, you would be lucky to hear back from your doctor within a week,” Gardiner said. “We’re often times getting results back to the veterinarian within 24-40 hours of the surgery. Most pet owners are hearing about their pet biopsies faster than humans are for their own diseases.”

Gardiner is an adjunct professor at Utah State University and is currently collaborating with USU researchers on measuring stress levels in dogs. He also works with USU vet students doing summer internships at ARP labs.

Esplin is officially retired and focuses on spending time with his family and grandchildren, but can still be found at the lab occasionally helping with diagnoses. • Story and photos by: Bronson Teichert Dr. Kimberly Henneman getting acquainted with a canine athlete.

Sports medicine and rehabilitation is an emerging specialty branch of veterinary medicine. Rehabilitation medicine aims to decrease pain, improve healing, enhance performance, prevent compensatory injuries, restore functional ability, and maintain an excellent quality of life.

When visiting with Dr. Kimberly Henneman, it is very clear she is passionate about improving the quality of life for any animal. A native of Utah, Henneman graduated magna cum laude from Utah State University with a bachelor of science in bioveterinary science, and was valedictorian of the College of Agriculture’s class of 1981 and USU's Scholar of the year. After graduating from Purdue School of Veterinary Medicine in 1986, Henneman received her IVAS certification in veterinary acupuncture in 1991, became the twenty-first veterinarian in the United States and first veterinarian in Utah to receive the AVCA certification in veterinary chiropractic, and finished her certification in veterinary Chinese herbal medicine through the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society in 2000. In 2014, she became the first veterinarian to achieve dual board-certification diplomate status (equine and canine) in the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation. “When I started practicing, a specialty for sports medicine and rehabilitation did not ex

ist,” Henneman said. “I contributed to its development.”

Western medicine is the current mainstream healthcare option for pets, but integrative and holistic options are gaining popularity and complement Henneman’s love of biomechanics. She works closely with an animal’s owner to develop integrative treatment plans.

As one of the first veterinarians to use thermal imaging in canine performance medicine and rehabilitation, Henneman helped one of her clients when they approached her regarding an endurance issue with their agility dog.

“We didn’t have ultrasounds at that time, so I used thermal imaging to identify the area of concern and developed an integrative treatment plan for the dog,” Henneman said. “Today, thermal imaging allows us to isolate or determine the location, and x-rays or ultrasounds help us diagnose the problem.”

Thermal imaging, acupuncture, rehabilitation, and chiropractic care also played a role in the 2002 Winter Olympics when Henneman organized the sports medicine center for the working and security dogs and horses; something that had never been done before at an Olympic Games. Henneman recalled, “The 2002 Winter Olympics was the first major international event after the 9/11 attacks and we had heightened security, including triple

Above: Dr. Henneman using chiropractic techniques to treat a rodeo bull. Top right: Thermal imaging helped isolate where this giraffe needed treatment.

“The Chinese medicine method allows us to look at the whole animal from a different perspective. We recognize the different stages of progression and can then treat each animal on an individualized basis.” - Dr. Kimberly Henneman

the usual number of security dogs coming to Utah.”

One of many highlights of Henneman’s career is her involvement with the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, a 1,000-mile trail race from Wasilla to Nome, Alaska. This year will mark the eighth year of Henneman’s participation. Over 50 veterinarians from throughout the world volunteer their time to check the health of these amazing athletic dogs before, during, and after the race. Every dog receives health checks in an extremely tight timeframe. Henneman also loves the research and friendship aspects of the race.

“All these races have been open to research and finding answers to problems regarding nutrition, fatigue, lameness, etc., that we have been able to apply to other performance dogs,” she said. “Even more, I love the long-lasting friends I have made through this experience.” • By: Michelle Merrill Photos: Courtesy of Dr. Kimberly Henneman

Caring for military working dogs is among the duties Dr. Stacie Anderson performs as part of the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps.

Veterinarians in the military wear many hats. In addition to the Military Working Dog mission, military veterinarians see appointments for privately owned animals, perform the food safety mission for the military services, and perform leadership duties by managing the affairs of veterinary hospitals. Military veterinarians take the lead by managing the staff, the core of which are the animal care specialists (68T) and veterinary food inspection specialists (68R).

There are many opportunities for veterinarians in the military, as many specialties are needed to complete missions. The various positions available for doctors of veterinary medicine in the Veterinary Corps include veterinary clinical medicine officers, health professional scholarship program (HPSP) officers, first-year graduate veterinary experience interns (FYGVE), veterinary laboratory animal medicine officers, veterinary preventative medicine officers, field veterinary service officers,

veterinary surgeons, and veterinary pathologists.

I am Captain Stacie Anderson, an officer in the United States Army Veterinary Corps and a graduate of the Washington-Idaho-Montana-Utah Regional Program in Veterinary Medicine veterinary corps officers. FYGVE interns work closely with clinical specialists during their FYGVE year, then typically move on to their first assignment as an officer in charge of a veterinary branch.

“The opportunities for unique experiences are boundless. Having been in my role for only 3 years, I have already gained experience working with bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions when I did active duty training with the U.S. Navy Marine Mammal Program in San Diego.” - Dr. Stacie Anderson

Class of 2018. I received the HPSP scholarship, a 3-year scholarship, in my second year of vet school at Utah State University. Students in that program attend a basic officer leadership training course following their second year of vet school and gain more officer training specific to veterinary medicine following graduation. HPSP students then typically move into the FYGVE internship program, which is a year-long program put in place by the military to allow newly graduated veterinary corps officers to become more confident and competent in their various roles as I have always had horses, dogs, and other animals and been interested in biology and medicine. I decided on becoming a veterinarian after I graduated from high school. I come from a military family—my mother is a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves Logistics Corp, my father retired as a lieutenant colonel from the Medical Service Corp, and other members of my family are currently serving or have served in various branches of the military—so joining the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps seemed like an excellent way to reach that goal.

The opportunities for unique experiences are boundless. Having been in my role for only 3 years, I have already gained experience working with bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions when I did active duty training with the U.S. Navy Marine Mammal Program in San Diego. I have also worked closely with experienced clinicians in the FYGVE program to provide the best possible care to our incredible military working dogs and our service members’ privately owned animals. I honestly believe this to be one of the most rewarding paths for a new veterinarian to take during and after veterinary school in order to become a confident and competent leader and clinician. • By: Dr. Stacie Anderson Photos: Courtesy of Dr. Stacie Anderson

Left: Dr. Anderson cares for military dogs and pets of members of the armed forces. Above: Working with marine mammals was part of Dr. Anderson’s active duty training.

Acritical component of providing the highest quality of care for pets begins with the correct diagnosis. Just like humans, sometimes an animal’s health or diagnosis requires the expertise of a specialist. Often times, this is where the skills of a veterinary radiologist come into play.

In 1971, there were only an estimated 25 board-certified veterinary radiologists in the country. Utah State University alumnus, Dr. Richard Park, was one of those 25. He grew up in Payson, Utah, where his family raised sheep and turkeys. In 1965, Dr. Park graduated from USU with a bachelor of science degree from the Department of Animal, Dairy and Veterinary Sciences. He went on to earn his doctorate of veterinary medicine from Colorado State University (CSU) in 1968, and became a board-certified veterinary radiologist in 1971, after completing his 3-year residency and PhD at Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, University of California, Davis.

Above: Here is a caption. Here is a caption Here is a caption Here is a caption Here is a caption Here is a caption Here is a caption - Dr. Richard Park

Pursuing a specialized career path in veterinary medicine was not common when Park was attending school. In fact, focusing on a vet med specialty was just beginning to evolve in the industry. Throughout his career, Park has witnessed many changes not only in general practice, but also in the equipment used. When he began his teaching career at CSU, they had just two X-ray machines.

Using radiographic pictures of bones, organs, blood vessels, etc., veterinary radiologists can reveal important information regarding an animal’s illness or health. Such findings could result in discovering arthritis, pancreatitis, diabetes or even cancer in animals. Parker has had opportunities to image all kinds of animals, including a baby rhino with brain cancer.

“It feels good knowing that information we (veterinary radiologists) find in an image will help the veterinarian treating the animal,” he said. “It’s also rewarding to know that much of the information we find is translational research. It affects human health too.”

Left and below: Dr. Richard Park uses his skills to give veterinarians information critical to correct diagnoses and taught other veterinary radiologists to effectively use a growing suite of radiology tools.

In particular, Park has greatly enjoyed the research component involved in radiology. Being able to provide practical research and publish that research for everyone to have access to has brought him immense job satisfaction.

Just like his mentors, and the impact they had on his educational experience, Park found his passion for teaching radiology evolving too. From 1980-2013, he was a professor in the Department of Environmental & Radiological Health Sciences in the College of Veterinary Medicine at CSU, and was director of the radiology residency program from 1985-2008. During that period, he supervised nearly 70 graduate students. Park has found the most rewarding and stimulating aspect of his career has been seeing how students progress.

“I have really enjoyed teaching students and residents in radiology,” he said. “Seeing them progress and do such amazing, great works with their careers has been the most rewarding for me.” • By: Michelle Merrill Photos: Courtesy of Dr. Richard Park

DR. HELOISA RUTIGLIANO

Heloisa Rutigliano grew up in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the city of Avaré. She earned her undergraduate degree in veterinary medicine from Sao Paulo State University and received her masters and doctoral degrees at the University of California, Davis. In 2010, Rutigliano began postdoctoral research at Utah State University. She is an assistant professor in USU’s Department of Animal, Dairy and Veterinary Sciences and teaches in the School of Veterinary Medicine. She loves spending time outdoors with her husband, David Epstein, and their two children, Beatriz and Leonardo. Heloisa Rutigliano , DVM, MPH, Associate Professor

How do you like Utah? Dr. Rutigliano: Well, I had to learn to ski. I enjoy the snow, but I don’t like how long the winter is. I love all the mountains and the outdoor activities. I love mountain biking, trail running, and back country skiing. You can’t do those things in Brazil because there are no mountains near where I am from.

What were your favorite experiences growing up in Brazil? Dr. Rutigliano: My dad was an agronomist and a farmer. We didn’t live at the farm, we lived in the city. We would be at the farm every weekend playing with animals and riding horses. I always knew that I wanted to be connected to rural communities. I was a typical veterinarian who, since I was 5 years old, would say that I wanted to be an animal doctor. I rode horses the whole day, worked and played with the animals. I remember tying the horse in front of the house, having lunch with my grandparents, and then riding again in the afternoon. We always had a lot of dogs, we adopted a lot of dogs, but we never had cats.

My mom is a teacher at a community college so I became a little bit of both of my parents.

What is your favorite animal to work with? Dr. Rutigliano: My favorite animals are dairy cows and goats. My dad never had goats, but I love goats. I think they are so interactive. I like animals that interact with you.

What are your research interests? Dr. Rutigliano: My first research interest is reproductive immunology. I study the developing fetus during gestation and the maternal immune system. For example, how the maternal immune system doesn’t reject the fetus or, in some cases, does reject the fetus. I use cattle as a model for that research. My second area of research is characterizing animal models for

UNEXPECTED LAMB DEATHS By Jane Kelly, DVM, MPH, Clinical Associate Professor

A sheep rancher with over 30 years of experience raising lambs lost several lambs in the spring and early summer of 2018. She had never seen clinical signs and death loss like this in all her years of farming. Clinical signs were only seen in the orphan or “bummer” lambs that were fed lamb milk replacer rather than ewe’s milk. The lambs nursing ewes and adult animals on the farm were not affected. Clinical signs seen included lameness, weakness, and unwillingness to move. When the rancher examined the lambs, they were in a great deal of pain and she could feel fractures of the legs. The lambs continued to have a good appetite and were alert. With nursing care, some of the lambs recovered but, unfortunately, some were severely affected and were submitted to the UVDL, Spanish Fork laboratory for necropsy. Gross lesions seen in two 3-monthold lambs necropsied included fractures of the legs and ribs and accompanying soft tissue hemorrhage. Joints were normal and there was no evidence of disease of the major abdominal and thoracic organs. The affected lambs were housed indoors, separately from the rest of the flock so it was unlikely that trauma (such as headbutting by ewes) was the cause of the fractures. All lambs (orphan and nursing ewes) had access to the same lamb starter grain product and the orphan lambs occasionally received Powerade mixed in the milk replacer. Formulate your diagnosis. •

Find the the answer at vetmed.usu.edu/mystery

human disease. I have a project funded by the American Heart Association that is looking at the effects of sex hormones like progesterone and estradiol on the incidents of atrial fibrillation in transgenic goats that have a gene making them more likely to develop atrial fibrillation. We are applying different hormonal treatments to see if they are more or less likely to develop atrial fibrillation. The third one is a new project. It’s looking at metabolism and its effect on the immunity of dairy cows. Dairy cows have a very high metabolism because they are producing a lot of milk. We’re trying to understand the molecular basis of that and trying to understand what metabolite effects immune function and what immune function isn’t there. We’re looking at how to manipulate that with mineral acids or more carbohydrates.

How did you become interested in this type of research? Dr. Rutigliano: I think pregnancy is the most fascinating biological event. Creating another being inside an organism is fascinating to me. I’ve always been fascinated by reproductive biology in general, mainly pregnancy and immunology.

What is your favorite class to teach? Dr. Rutigliano: Immunology. There are so many discoveries going on, there are so many therapies involving the immune system nowadays and it’s a fast-evolving field. It changes all the time and it’s a complex system that is important for survival.

What are you most proud of during your time at USU? Dr. Rutigliano: I am most proud of the number of students I have introduced to research. It’s getting to be over 20 graduates, undergrads, interns and even high school students I’ve had in my lab. Hopefully I’ve made them excited and curious about research. •

By: Bronson Teichert Photos: Dennis Hinkamp