id ** o M CD CD bi < O r C s M 05 © a w B ft) to XL7 ? V ' •*' •

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORYBOARD OF EDITORS

KENNETH L CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1992

ARLENE H EAKLE, Woods Cross, 1993

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1994

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1994

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1992

RICHARD W SADLER, Ogden, 1994

HAROLD SCHINDLER, Salt Lake City, 1993

GENE A SESSIONS, Ogden, 1992

GREGORY C. THOMPSON, Salt Lake City, 1993

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801) 533-6024 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $15.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $10.00; contributing, $20.00; sustaining, $25.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate accompanied by return postage and should be typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 1/4 inch MS-DOS or PCDOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. Additional information on requirements is available from the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

ftj *Xn£fl*XX Contents SPRING 1992 / VOLUME 60 / NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 99 THE PECULIAR CASEOFJAMESLYNCH AND ROBERT KING DAVID L. BUHLER 101 JUSTICE INTHE BLACKHAWKWAR: THE TRIAL OFTHOMASJOSE ALBERT WINKLER 124 CHARLESR. SAVAGE, THE OTHER PROMONTORY PHOTOGRAPHER BRADLEY W. RICHARDS 137 DIARYOFMARYELIZABETH (MAY) STAPLEY,A SCHOOLTEACHER INVIRGIN, UTAH edited by KERRY WILLIAM BATE 158 THEAMERICANIZATION OF AN IMMIGRANT, THE REV. MSGR. ALFREDO F.GIOVANNONI . . . BERNICE MAHER MOONEY 168 BOOKREVIEWS 187 BOOKNOTICES 194 THE COVER Gov. Charles R. Mabey wields shovel at the opening of Magna Park on May 2, 1924. USHS collections, gift of Governor Mabey. © Copyright 1992 Utah State Historical Society

L KAY GILLESPIE The Unforgiven: Utah's Executed Men

KEN DRIGGS 187

THOMAS G ALEXANDER Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff a Mormon Prophet

RICHARD W. SADLER 188

JAMES H. BECKSTEAD. Cowboying: A Tough Job in a Hard Land

ROBERT S. MCPHERSON 189

CARLOS SCHWANTES In Mountain Shadows: A History of Idaho

SANDRA SCHACKEL 191

VOYLE L MUNSON AND LILLIAN MUNSON A Gift of Faith: Elias Hicks Blackburn, Pioneer, Patriarch, and Healer.

RONALD G. WATT 192

THOMAS EDWARD CHENEY. Voices from the Bottom of the Bowl: A Folk History of Teton Valley, Idaho, 1823-1952

DAVID L. CROWDER 193

Books reviewed

In this issue

The "capacity for justice makes democracy possible," theologian Reinhold Niebuhr observed. Indeed, animated discussions of justice both as an abstract idea and as applied to endlessly varied situations define healthy democracies worldwide. The first article in this issue looks at an extraordinarily complicated turn-of-the-century murder case in Salt Lake City in which an innocent man, convicted and imprisoned for over three years, refused to participate in an escape while his guilty co-defendant saved a guard's life before bolting to temporary freedom. How justice eventually served both men makes an absorbing tale The next piece focuses on a forgotten 1867 murder trial in Iron County Here the defendant was a white man accused of murdering an Indian, a crime typically ignored by authorities in frontier times. Justice in this case decreed the sanctity of a Native American life.

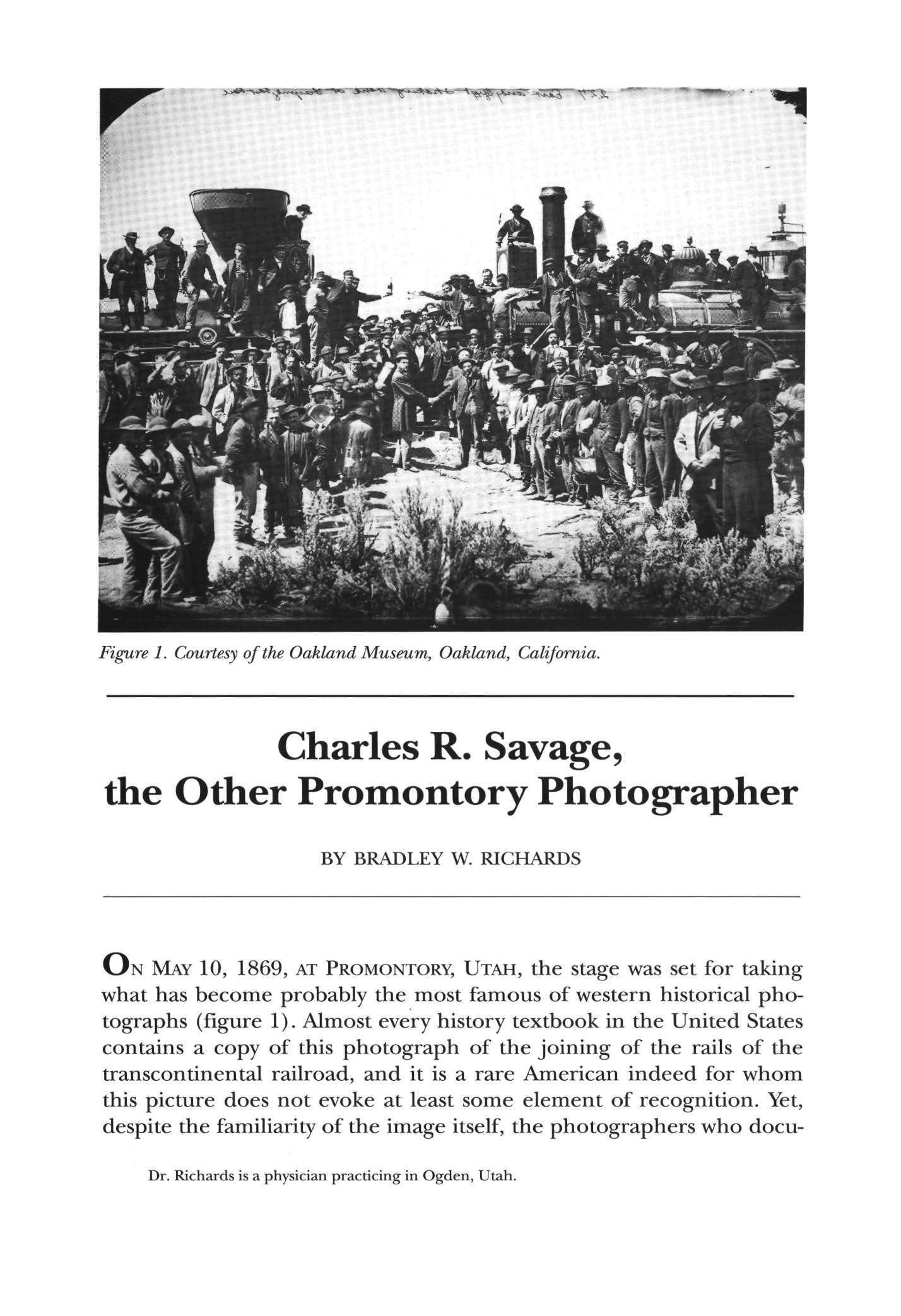

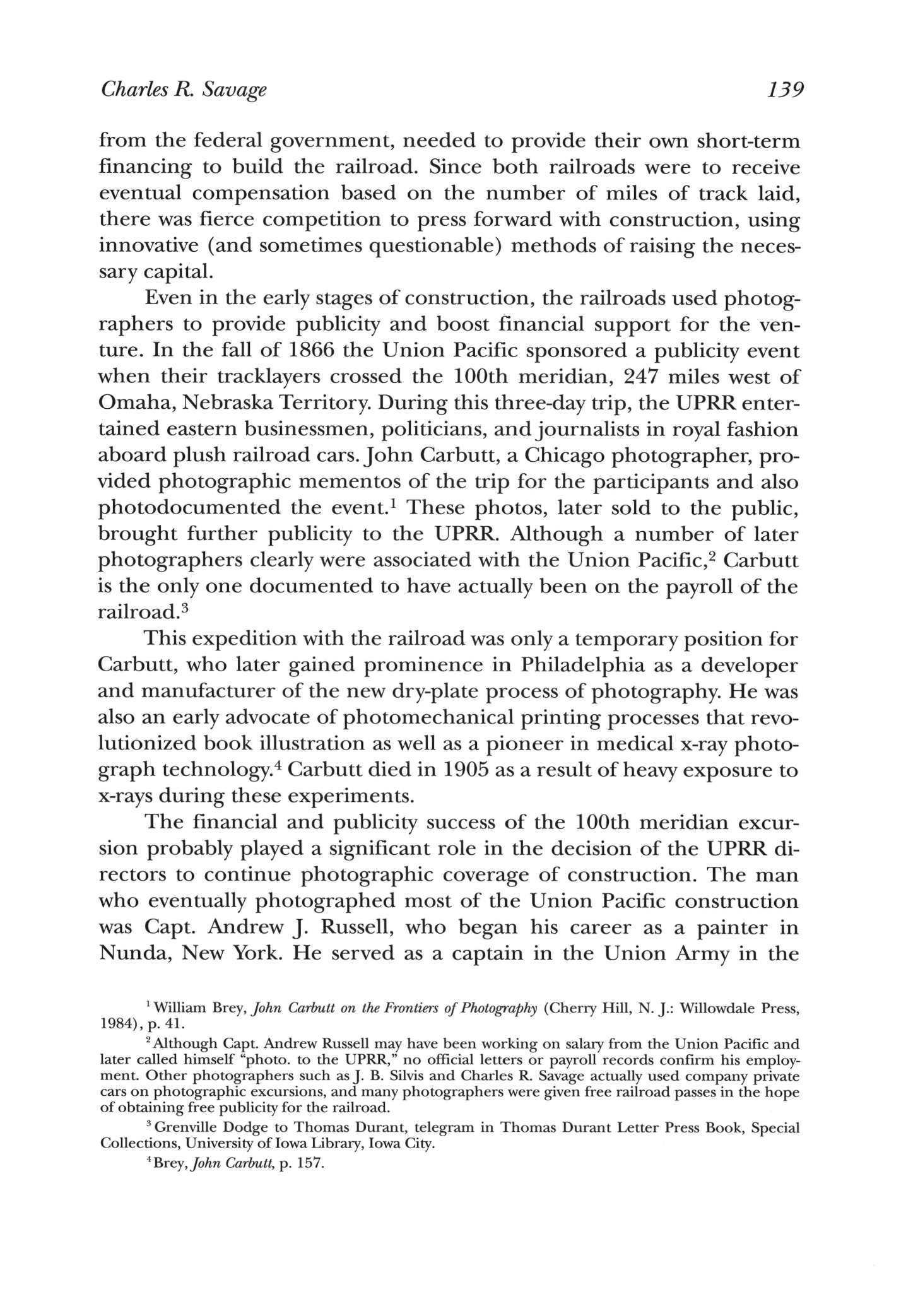

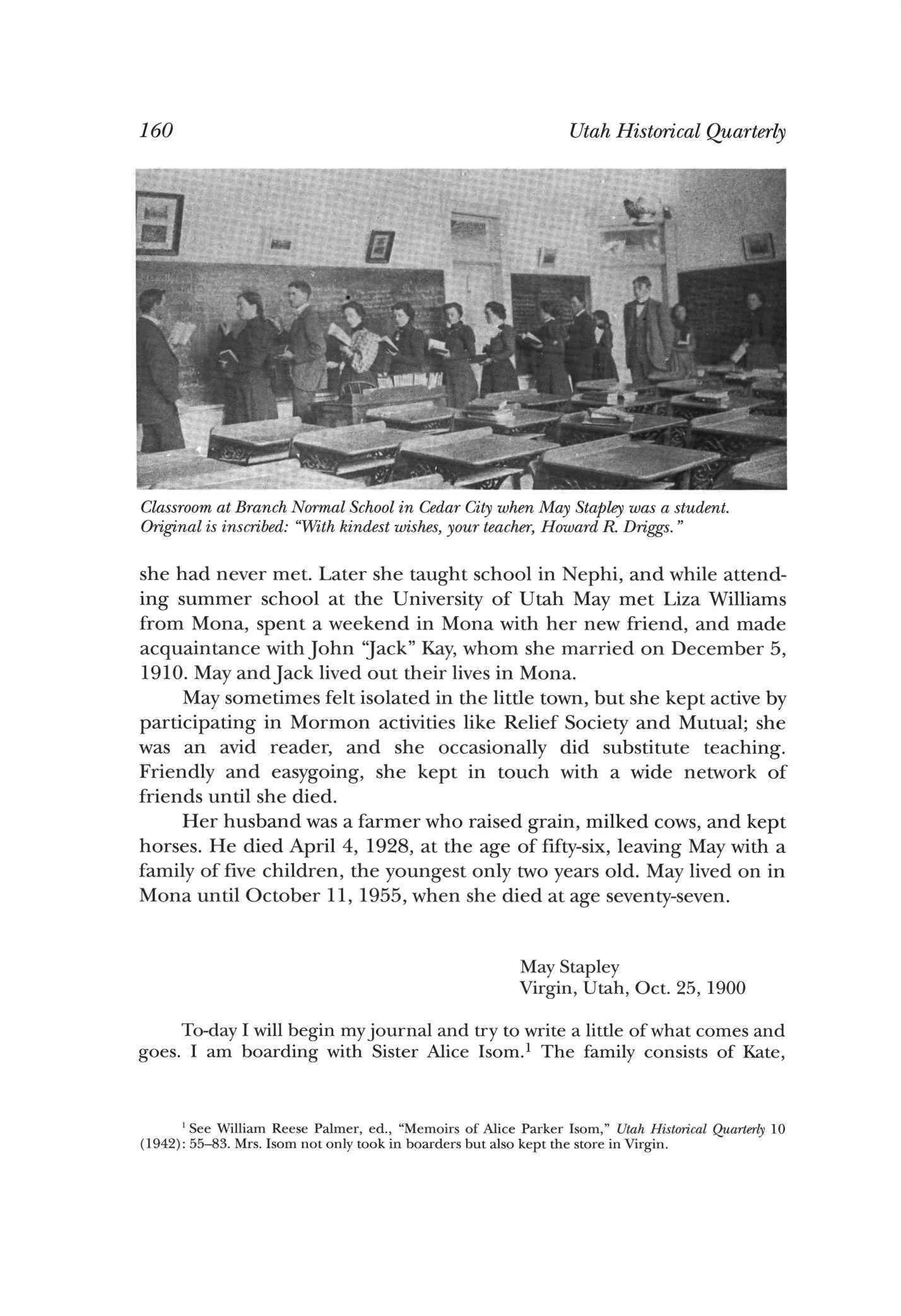

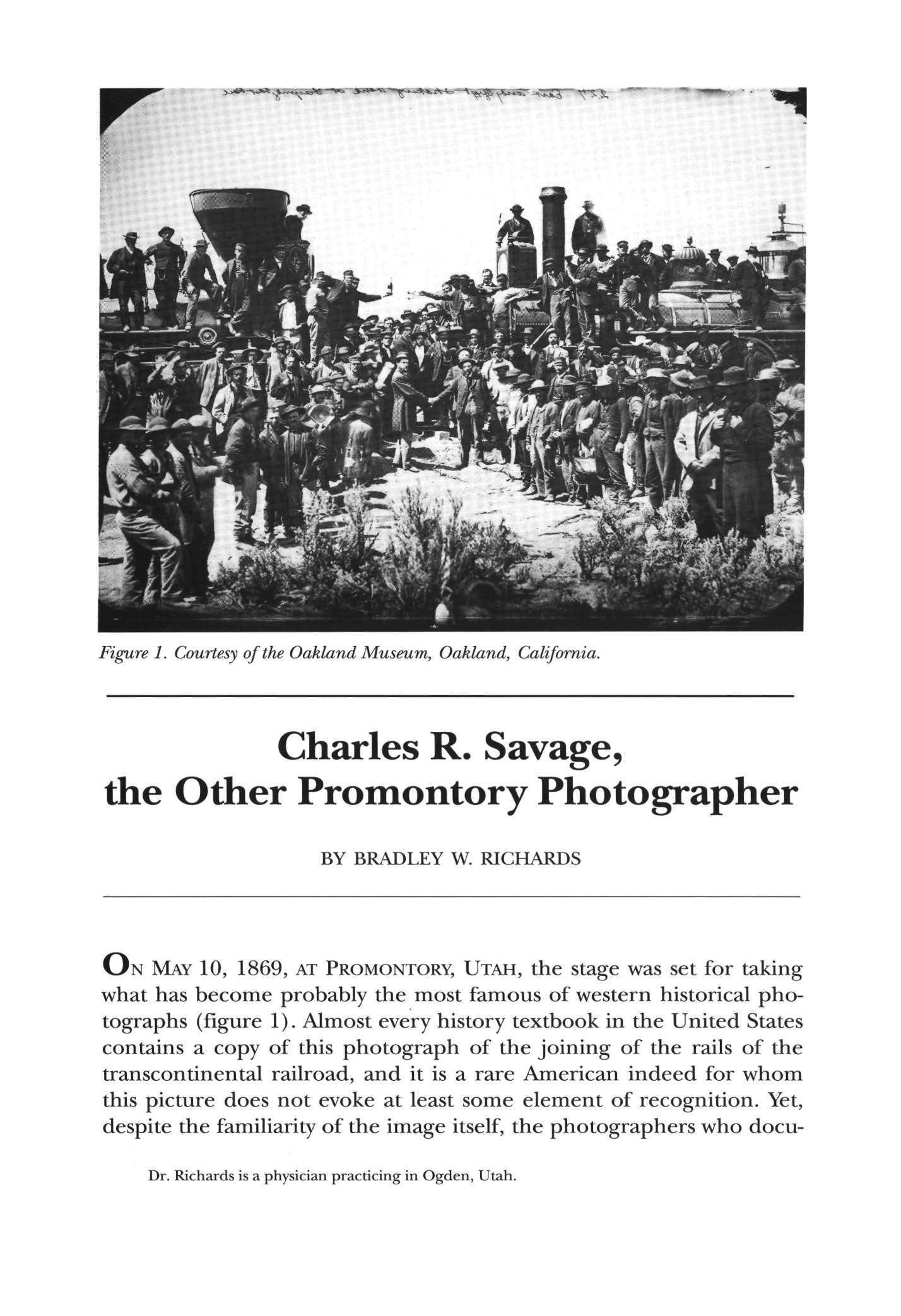

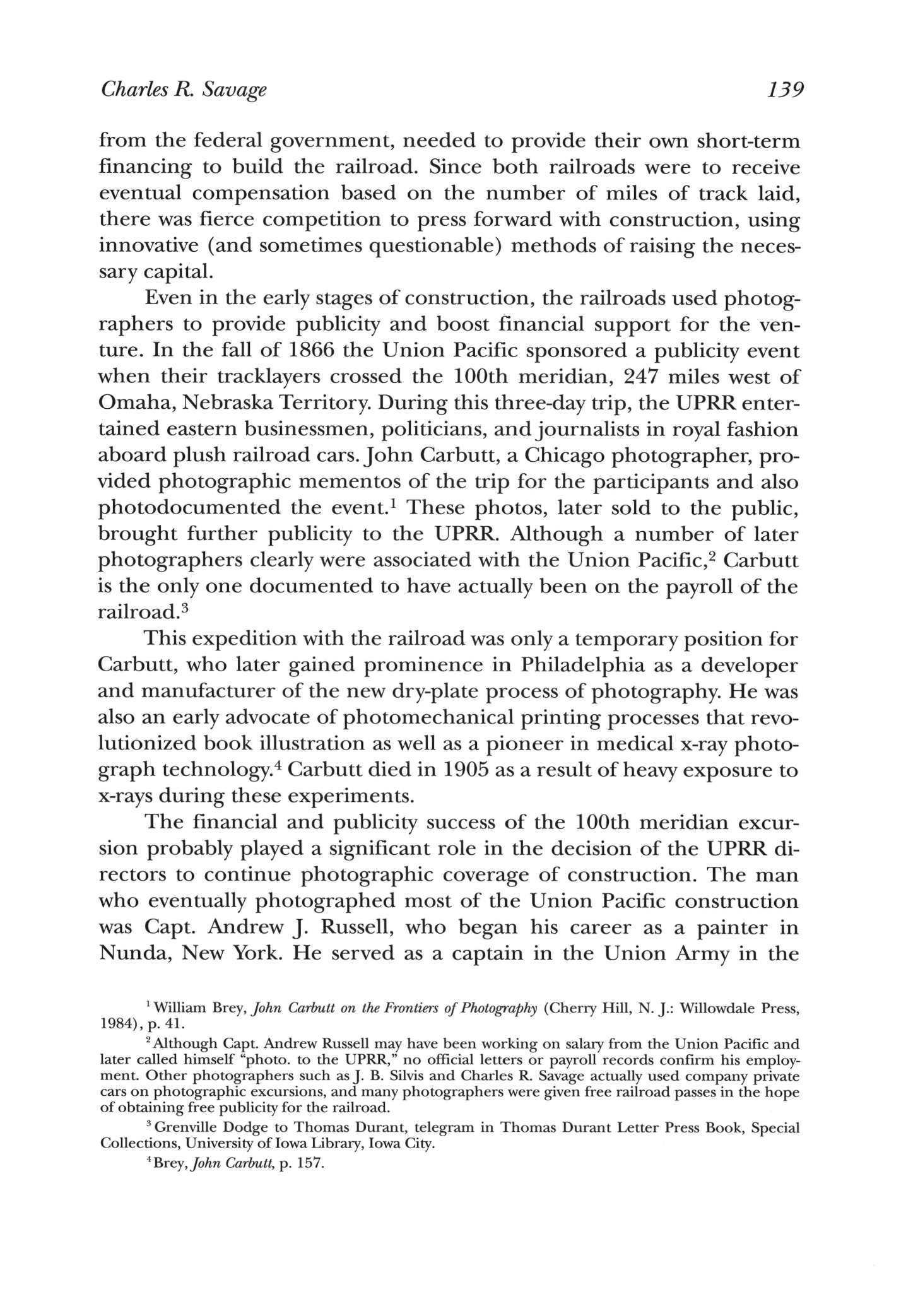

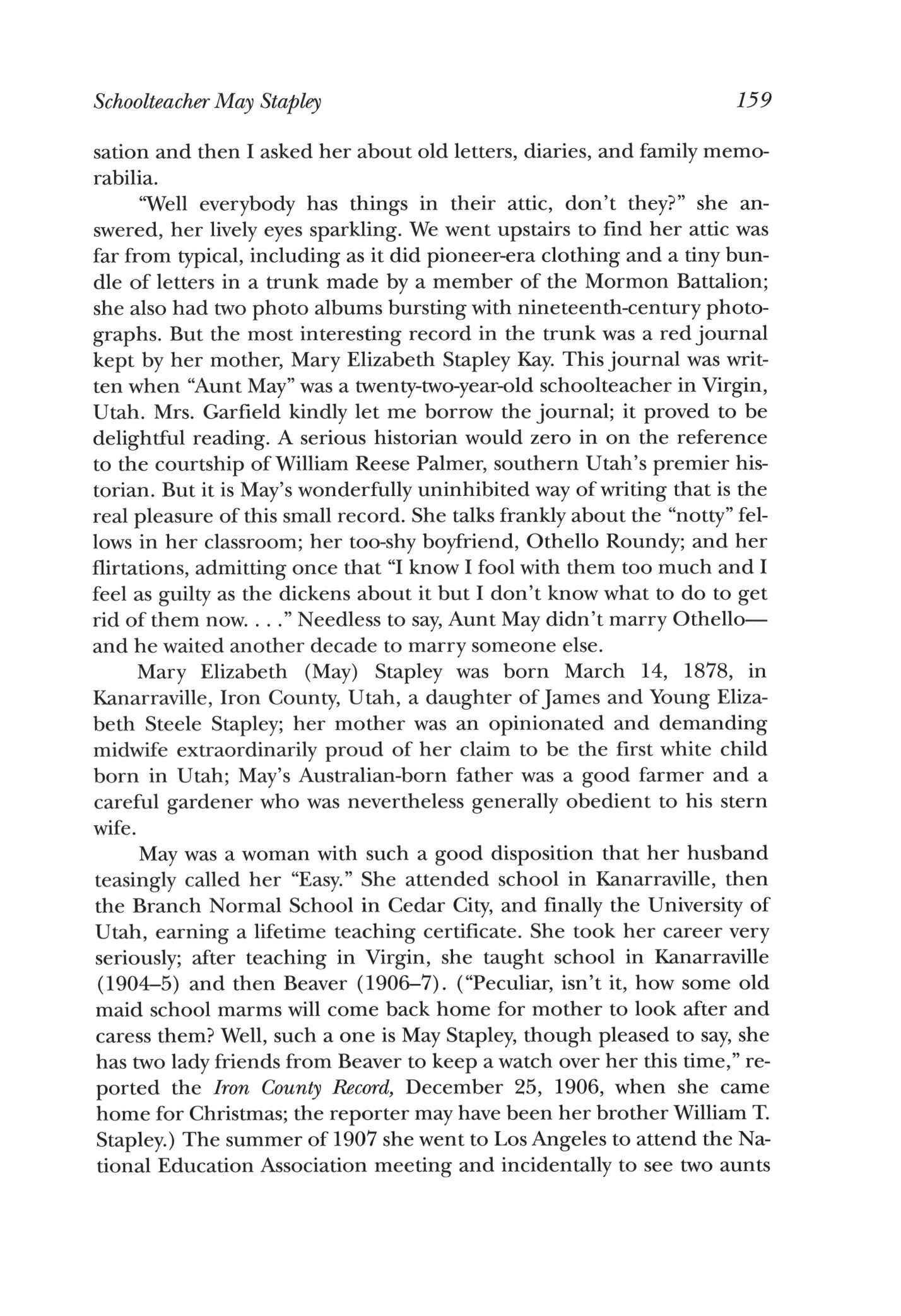

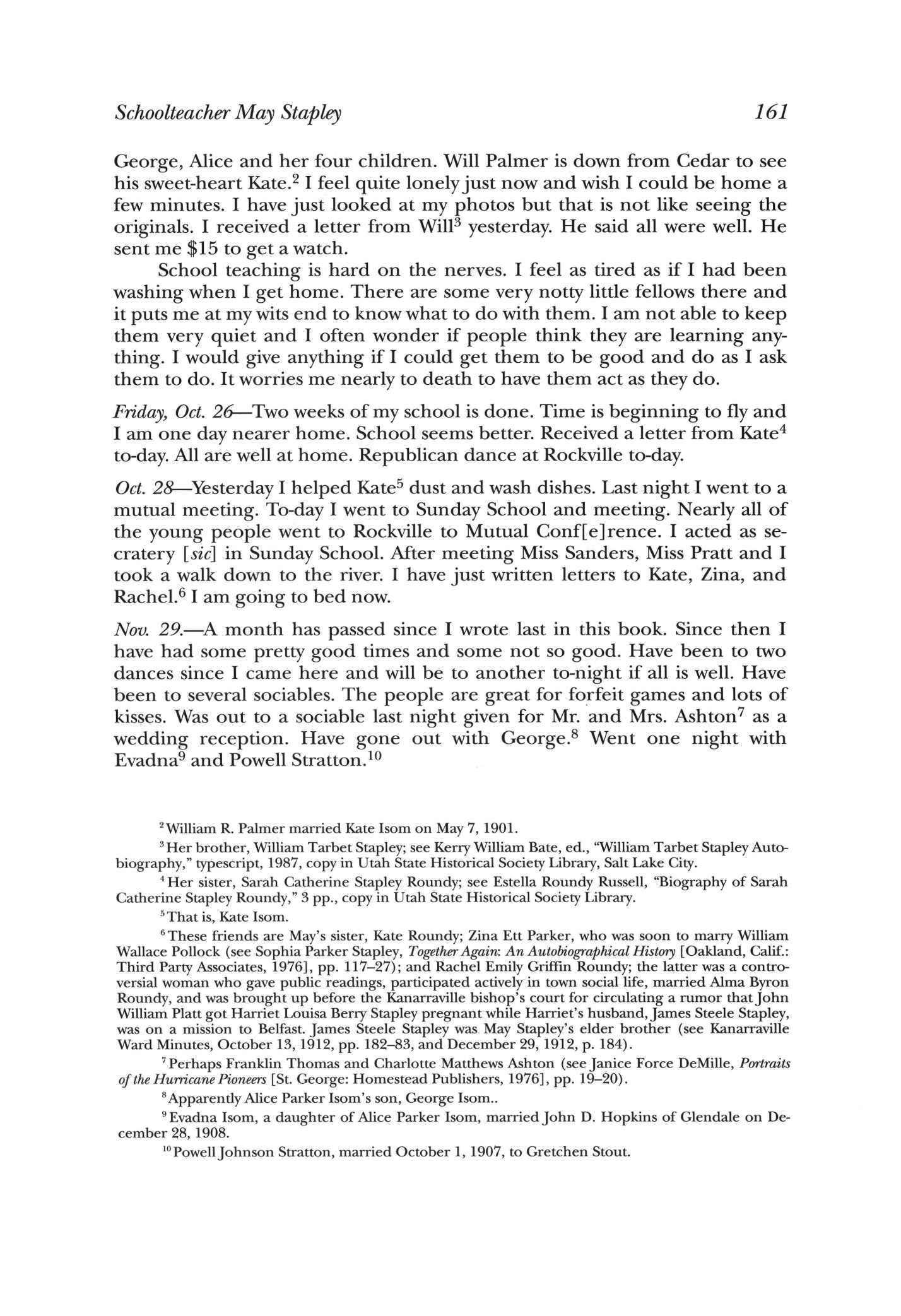

The remaining articles examine the lives of three very different individuals who played a part on the stage of Utah history: photographer Charles R. Savage whose role in documenting the joining of the rails at Promontory has been largely overlooked; schoolteacher May Stapley whose brief diary provides delightful glimpses of rural social life in 1900; and the Rev. Msgr. Alfredo F. Giovannoni, a colorful and energetic priest whose long ministry helped to shape Utah's Catholic heritage. Recognizing this trio's contributions is a small but important part of achieving justice, or fair representation, in the historical record

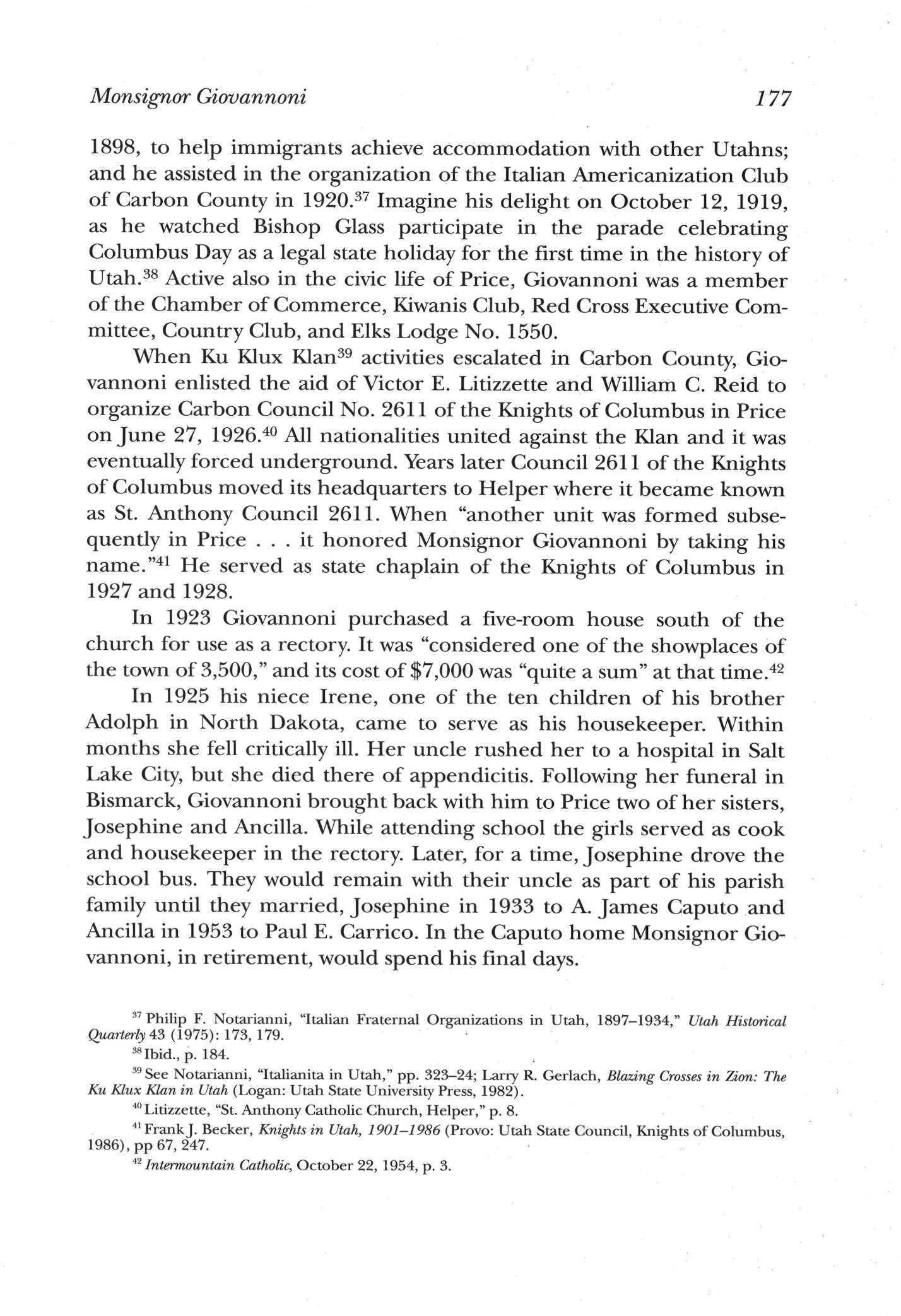

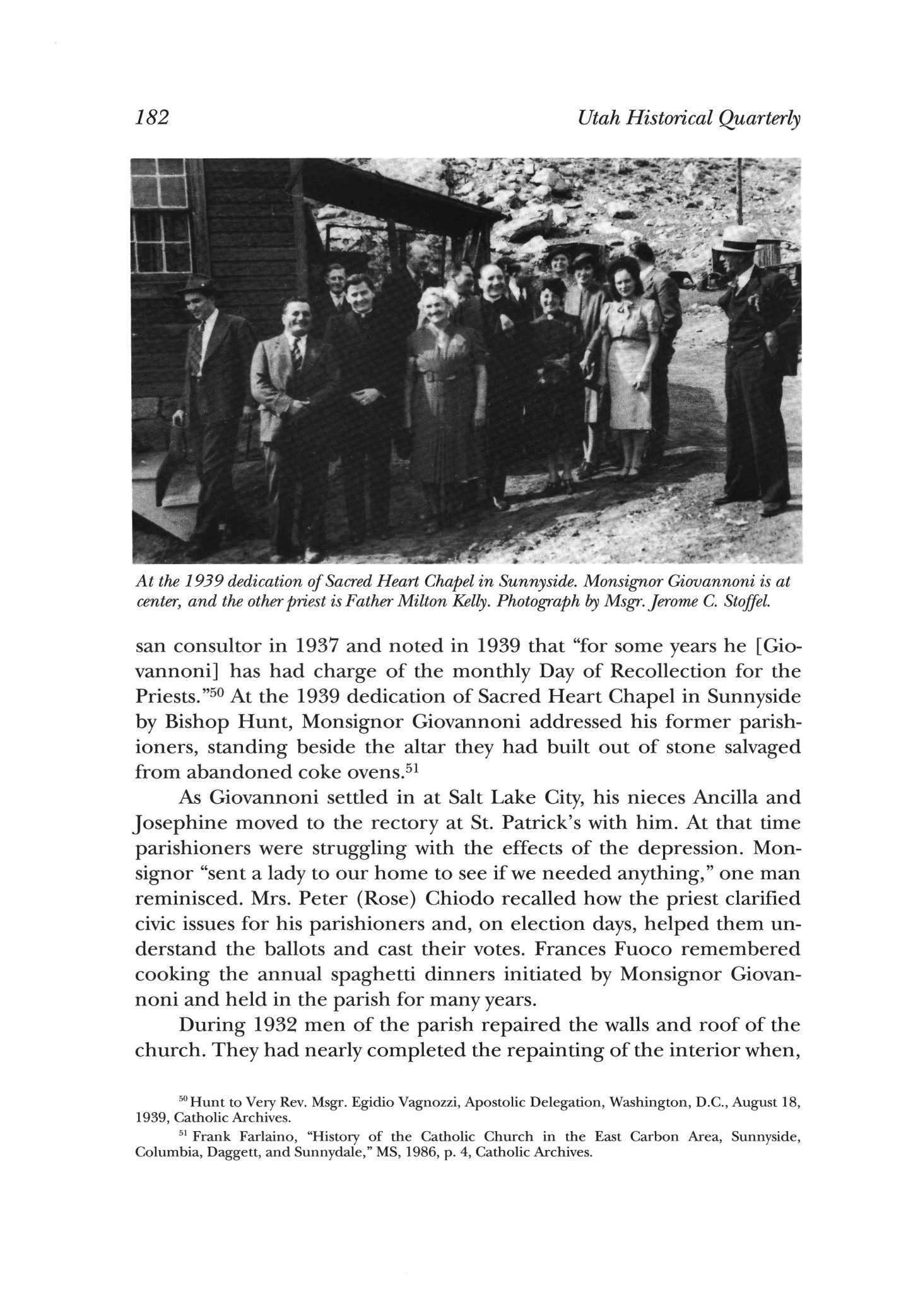

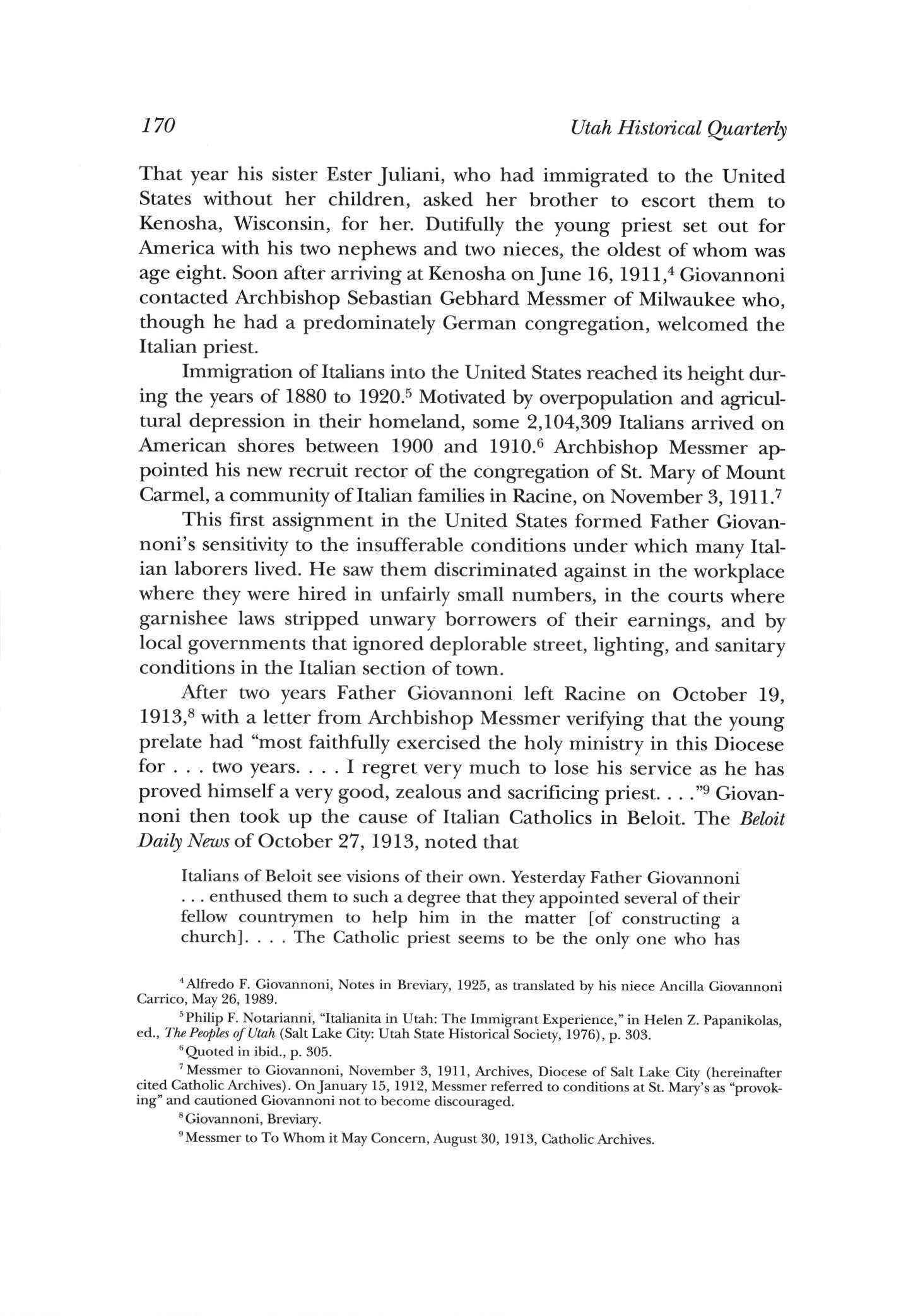

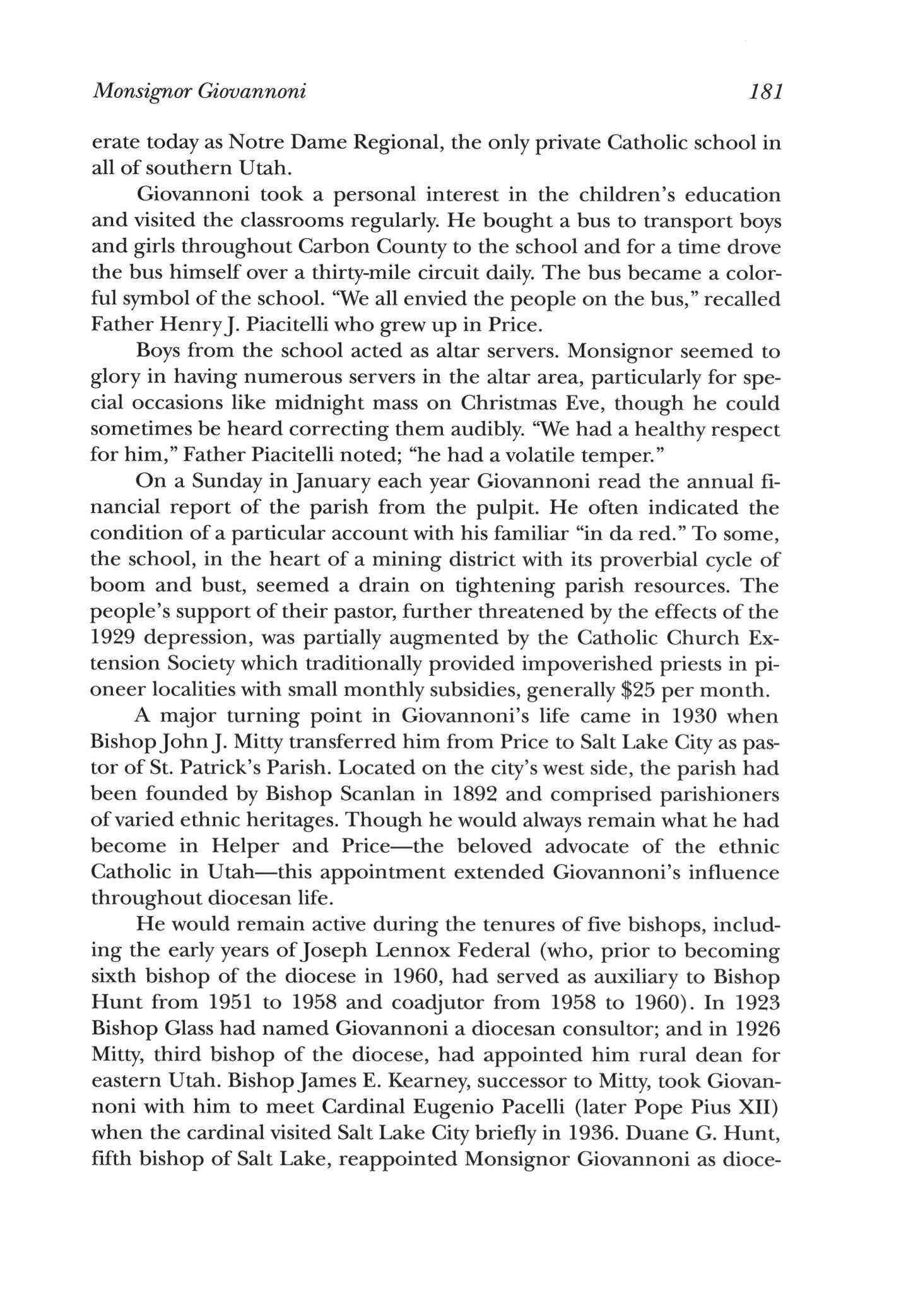

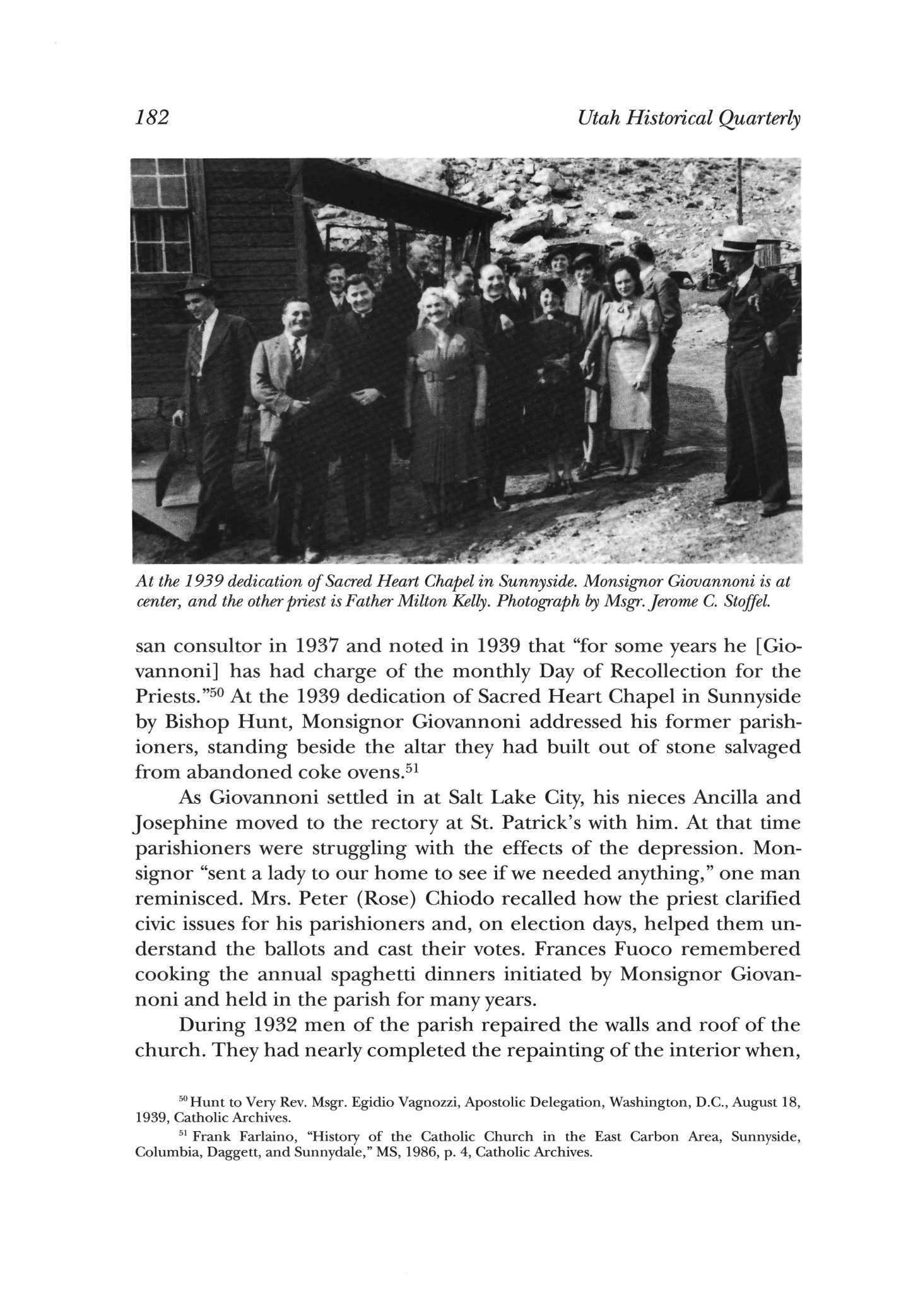

BishopDuane G.Hunt, theRev.Msgr.AlfredoF.Giovannoni,and othersat 1939 cornerstonelayingforSt.Anthony's Church,Helper. Photograph byMsgr.feromeC. Stoffel.

BishopDuane G.Hunt, theRev.Msgr.AlfredoF.Giovannoni,and othersat 1939 cornerstonelayingforSt.Anthony's Church,Helper. Photograph byMsgr.feromeC. Stoffel.

, v immma. » JOAT/F T.AITTE iwvv TTVAT4 Ai)r rl*A ^ ^ / **v 5% ^ ^' *

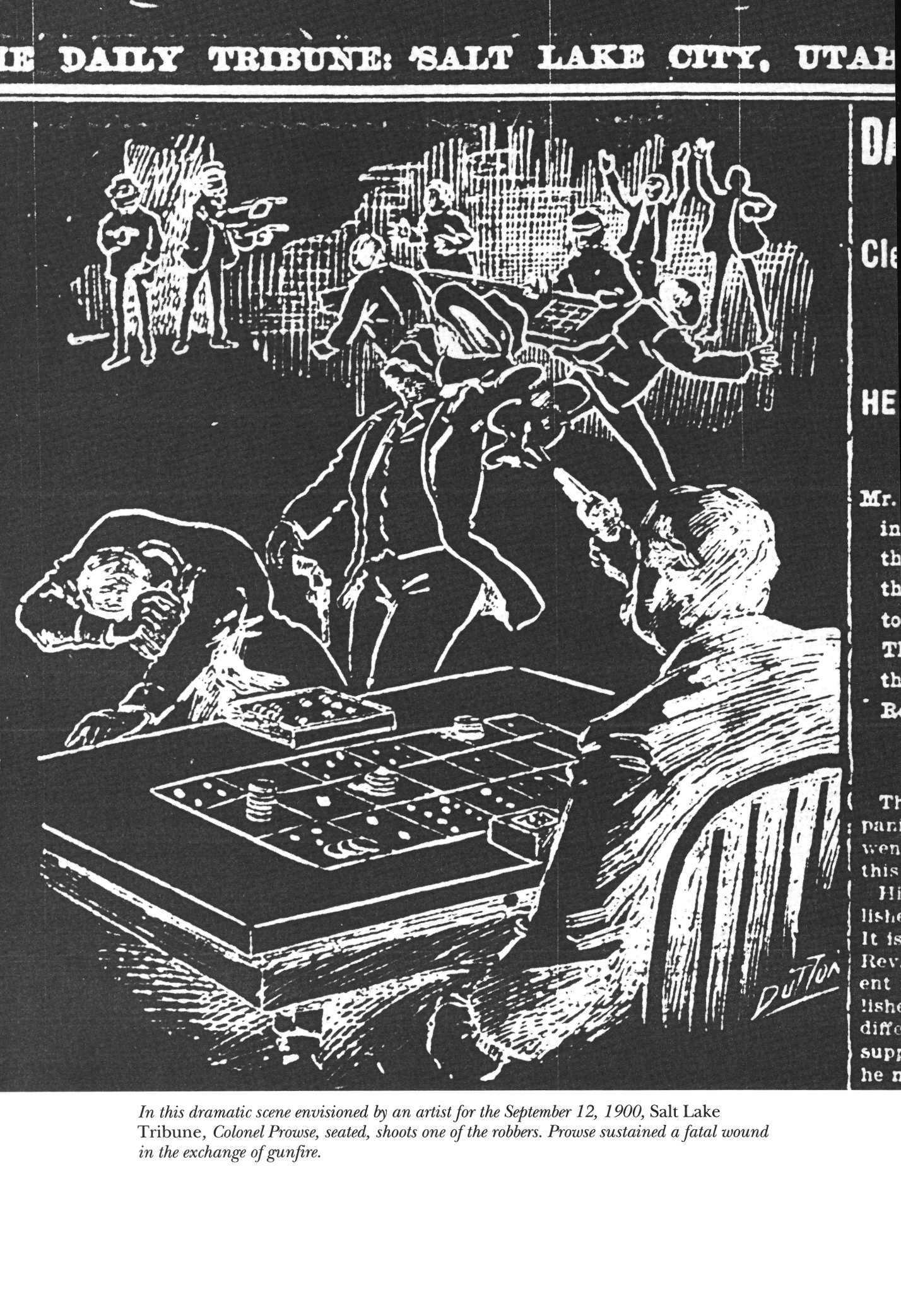

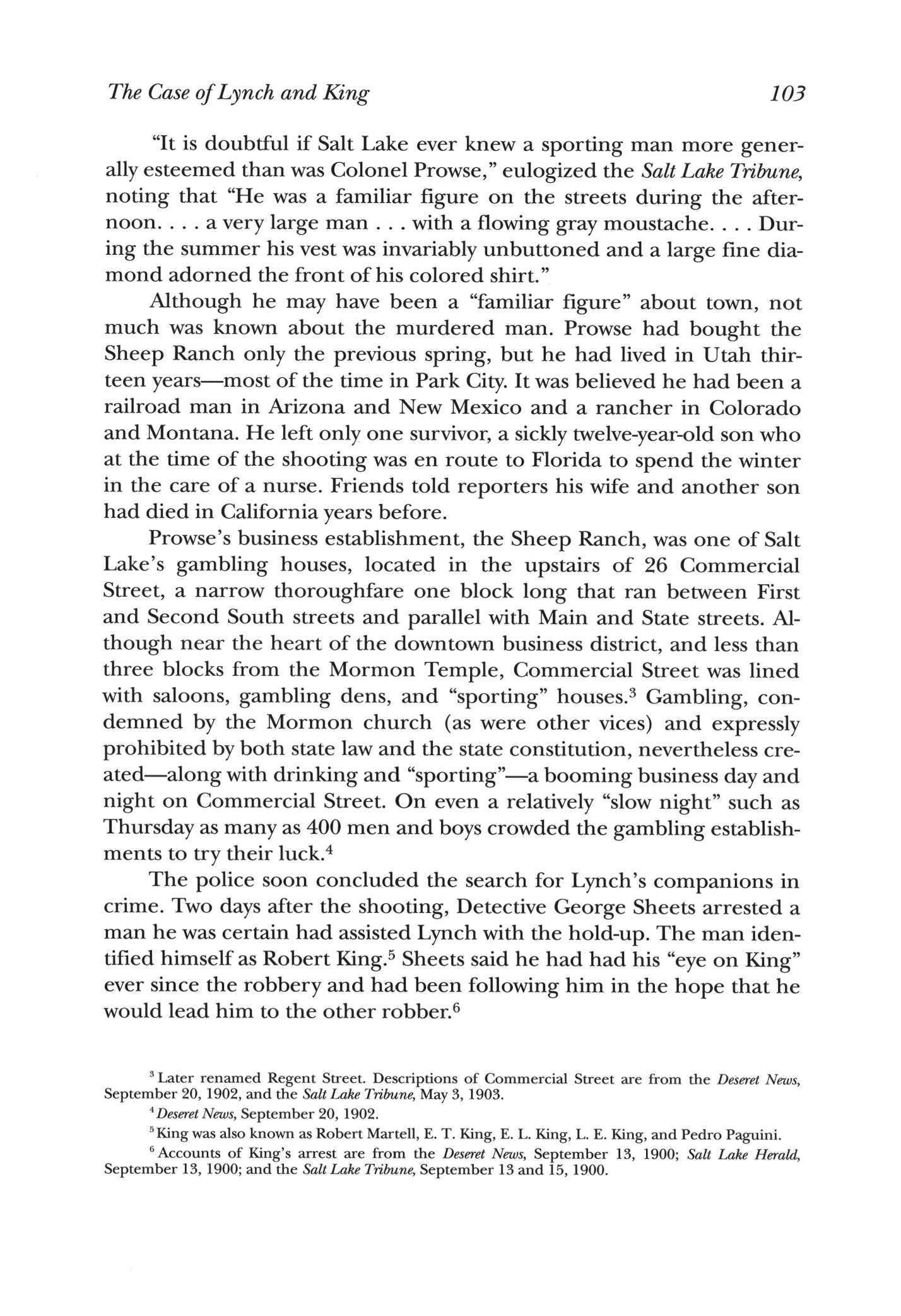

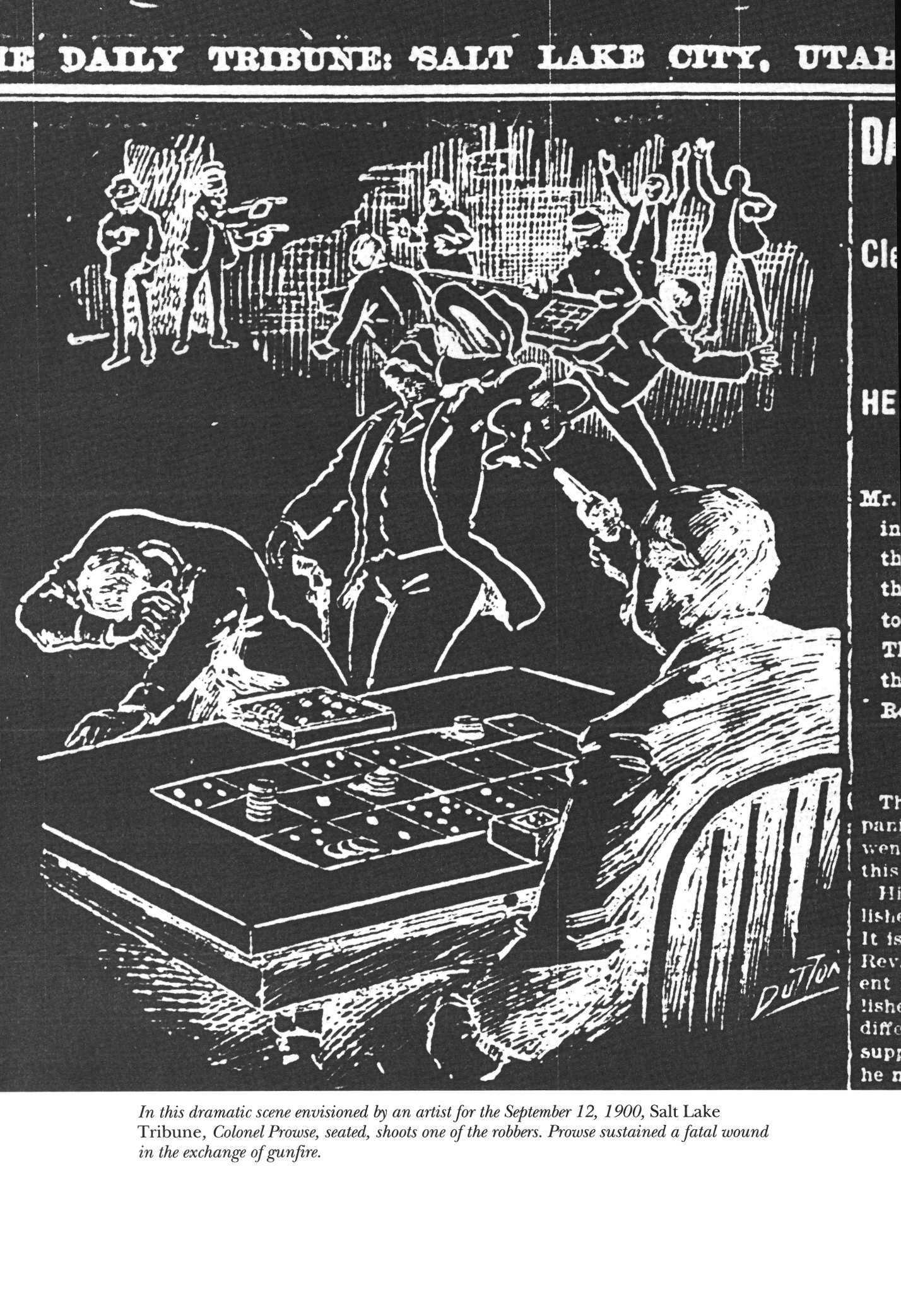

/w £/w.s dramatic scene envisioned by an artistfor the September 12, 1900, Salt Lake Tribune, Colonel Prowse, seated, shoots one of the robbers. Prowse sustained a fatal wound in the exchange of gunfire.

The Peculiar Case of James Lynch and Robert King

BY DAVID L. BUHLER

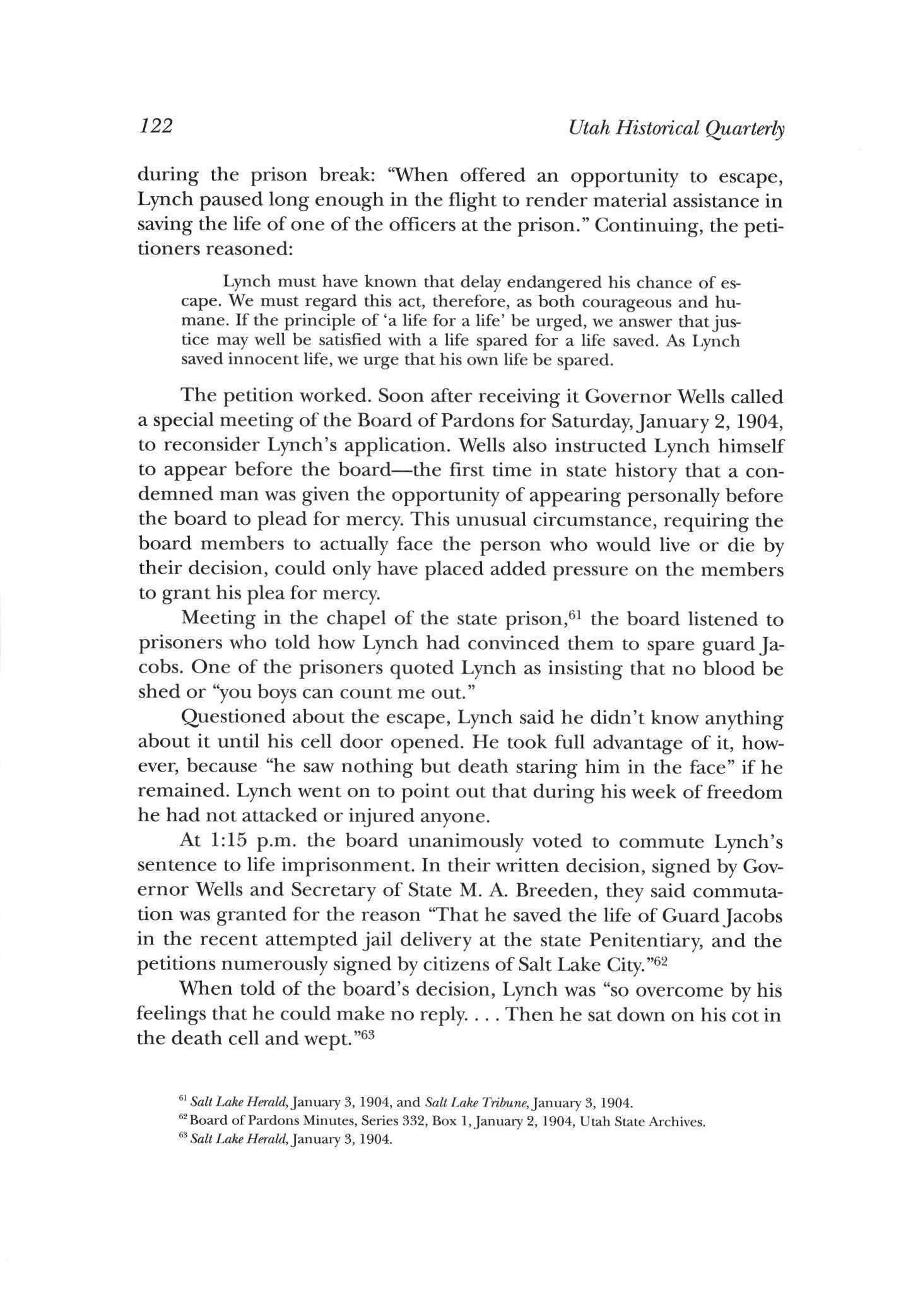

A T TWO A.M. ON TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 1900, three men, revolvers in hand and handkerchiefs pulled snugly over their faces, entered the Sheep Ranch,1 one of several gambling houses located on Salt Lake City's notorious Commercial Street. Two of the three masked men stayed near the entrance, their guns drawn The third approached Col George Prowse,2 the proprietor of the Sheep Ranch, who was seated at a table—the Ranch's "bank." As the man approached, Prowse pulled a gun from the table's drawer and rose to his feet. The robber and Prowse exchanged shots—witnesses were unsure who fired first. The robber, hit in the head, fell to the floor unconscious. The two remaining masked men fired five times, hitting Prowse at least once, and then bolted out the door and down the stairs to the alley below. Simultaneously, Prowse fired four more shots. In the exchange of gunfire a Sheep Ranch employee, Ernest Sidell, was also wounded as a bullet grazed his ear and shoulder

Salt Lake City Police Sgt John B Burbidge, who was nearby, heard the shots and arrived on the scene shortly after the two bandits had fled. When Burbidge entered the Sheep Ranch he saw Prowse "sitting in a chair, his head dropped forward." Sidell was "staggering around the room in a dazed manner, while the [third] robber lay on the floor in a pool of blood and to all appearances dead." Prowse was taken to St. Mark's Hospital for treatment, and Sidell was examined at a neighborhood drugstore. The wounded robber was taken to jail where his wound—which was not serious—was treated by a physician

Later that morning the prisoner identified himself asJames Lynch. He said he was twenty-six years old, from Albany, New York, and had worked in mines and smelters in the West and British Columbia before coming to Salt Lake three days earlier. Asked by a reporter if he had

'Accounts of the robbery were taken from DeseretNews, September 11 and 14, 1900; Salt Lake Herald, September 12 and 13, 1900; and Salt Lake Tribune, September 12 and 26, 1900.

Mr Buhler is executive director of the Utah Department of Commerce

2 Also known as Godfrey Prousse

Mr Buhler is executive director of the Utah Department of Commerce

2 Also known as Godfrey Prousse

done any of the shooting at the Sheep Ranch, Lynch replied, "Damn if I know."

Newspaper reporters,jailers, and policemen all endeavored to persuade Lynch to name his still at-large accomplices At one point Detective George Sheets even brought him a pint of whiskey, hoping this "friendly gesture"would prompt the prisoner to become more cooperative, but Lynch steadfastly refused to identify his partners, saying only that he did not know their names.

The police were not entirely without leads in their attempt to find the other two bandits, having located several witnesses who said they had seen Lynch's accomplices. One witness was Frank Lyon, an employee of the Sheep Ranch, who said he saw three men, including Lynch, at the establishment for several nights before the shooting Lyon finished his shift about an hour before the attempted robbery. Prior to leaving that night he saw the men unlock the back doors. One of the three was Lynch, Lyon said, and he was positive he could identify the other two if he saw them again.

A second witness was a seventeen-year-old messenger boy, William Wittenberg, who told police he saw two men run from the Sheep Ranch, down an alley, and into the nearby Headquarters Saloon. He followed them into the bar, talked with one of them, and got a good look at both. The Headquarters bartender told police that he had noticed the two men enter the bar, and he provided a similar description.

A clue left near the scene of the crime—a new-looking leather valise found at the foot of the Sheep Ranch stairway—also gave police hope of identifying and capturing the other two robbers.

From his hospital bed George Prowse discussed the attempted robbery with a Salt Lake Herald reporter, saying that as soon as he saw the robbers were armed he went for his gun. The man who approached him, Prowse said, "immediately started to shoot I was hit by the first ball I thought he had killed me."After Prowse was hit he returned fire: "If I had not been hit I would not have shot . . .Anyway, I only winged him. He didn't give me half a chance."

Prowse underwent surgery at 7:00 p.m as doctors attempted without success to locate and remove the bullet that had entered his thigh. Following surgery he "grew weaker and about 9 o'clock became unconscious" and died at 9:30 p.m. without regaining consciousness. The post-mortem examination determined the cause of death to be "acute peritonitis" resulting from perforation of the intestines as the bullet traveled through his abdomen before lodging in his hipbone

102 Utah Historical Quarterly

"It is doubtful if Salt Lake ever knew a sporting man more generally esteemed than was Colonel Prowse," eulogized the Salt Lake Tribune, noting that "He was a familiar figure on the streets during the afternoon. ... a very large man . . . with a flowing gray moustache. . . . During the summer his vest was invariably unbuttoned and a large fine diamond adorned the front of his colored shirt."

Although he may have been a "familiar figure" about town, not much was known about the murdered man. Prowse had bought the Sheep Ranch only the previous spring, but he had lived in Utah thirteen years—most of the time in Park City It was believed he had been a railroad man in Arizona and New Mexico and a rancher in Colorado and Montana He left only one survivor, a sickly twelve-year-old son who at the time of the shooting was en route to Florida to spend the winter in the care of a nurse. Friends told reporters his wife and another son had died in California years before.

Prowse's business establishment, the Sheep Ranch, was one of Salt Lake's gambling houses, located in the upstairs of 26 Commercial Street, a narrow thoroughfare one block long that ran between First and Second South streets and parallel with Main and State streets. Although near the heart of the downtown business district, and less than three blocks from the Mormon Temple, Commercial Street was lined with saloons, gambling dens, and "sporting" houses.3 Gambling, condemned by the Mormon church (as were other vices) and expressly prohibited by both state law and the state constitution, nevertheless created—along with drinking and "sporting"—a booming business day and night on Commercial Street. On even a relatively "slow night" such as Thursday as many as 400 men and boys crowded the gambling establishments to try their luck.4

The police soon concluded the search for Lynch's companions in crime. Two days after the shooting, Detective George Sheets arrested a man he was certain had assisted Lynch with the hold-up The man identified himself as Robert King.5 Sheets said he had had his "eye on King" ever since the robbery and had been following him in the hope that he would lead him to the other robber.6

3 Later renamed Regent Street Descriptions of Commercial Street are from the Deseret News, September 20, 1902, and the Salt Lake Tribune, May 3, 1903

4 Deseret News, September 20, 1902

5 King was also known as Robert Martell, E. T. King, E. L. King, L. E.

and Pedro Paguini. "Accounts of King's arrest are from the Deseret News, September 13, 1900; Salt Lake Herald, September 13, 1900; and the Salt Lake Tribune, September 13 and 15, 1900

The Case of Lynch and King 103

King,

King was living at Walker House on West Temple Street, registered under the name of "Robert Martell." He was employed as a dealer at the Lone Star gambling house and said he had worked there from 1:00 to 5:00 p.m. the afternoon prior to the Sheep Ranch hold-up, a fact corroborated by the proprietor He said he had gone to bed at the Walker House shortly before midnight the night of the shooting King insisted that he was not involved in the crime and would have no trouble proving his innocence.

Before arresting King, Sheets had spoken with a store clerk, William Meyers, who identified the valise found near the Sheep Ranch as the one he had sold, along with three handkerchiefs, to a man the afternoon before the holdup He had wrapped the merchandise in yellowish brown paper. After locking up King, Sheets searched his room at the Walker House where he found a piece of yellowish brown paper that fit the clerk's description. He also found burglary tools—steel drills, blasting powder, a powder blower, and a skeleton key. Sheets then took the wrapping paper to Meyers who readily identified it Later that evening Sheets escorted Meyers and the other eyewitness, the messenger boy Wittenberg, to thejail. Both identified King.

Despite the eyewitnesses found by Sheets and the incriminating wrapping paper, King continued to proclaim his innocence and sought to dispute the evidence against him: 'That man Meyers isoff base when he says I am the man who bought a valise from him He's got me mixed up with someone else," King told newspaper reporters the day after his arrest

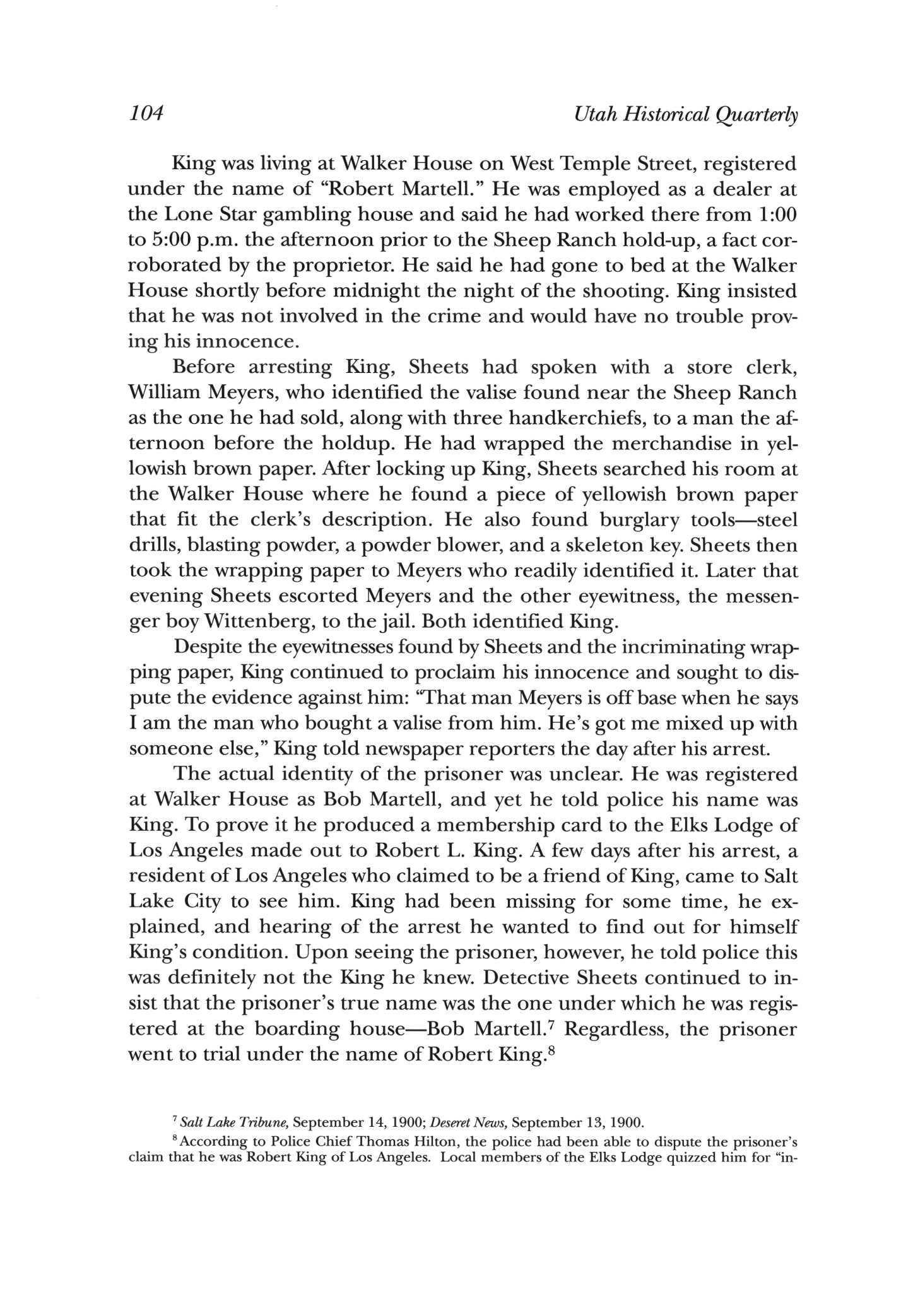

The actual identity of the prisoner was unclear He was registered at Walker House as Bob Martell, and yet he told police his name was King. To prove it he produced a membership card to the Elks Lodge of Los Angeles made out to Robert L. King. A few days after his arrest, a resident of Los Angeles who claimed to be a friend of King, came to Salt Lake City to see him King had been missing for some time, he explained, and hearing of the arrest he wanted to find out for himself King's condition. Upon seeing the prisoner, however, he told police this was definitely not the King he knew. Detective Sheets continued to insist that the prisoner's true name was the one under which he was registered at the boarding house—Bob Martell.7 Regardless, the prisoner went to trial under the name of Robert King.8

104 Utah Historical Quarterly

1 Salt Lake Tribune, September 14, 1900; Deseret News, September 13, 1900

8 According to Police Chief Thomas Hilton, the police had been able to dispute the prisoner's claim that he was Robert King of Los Angeles Local members of the Elks Lodge quizzed him for "in-

After an inquest and preliminary hearing, King and Lynch were tried on October 30, 1900, for the murder of George Prowse in Third District Court, with Judge John Booth presiding The prosecution was handled by Salt Lake County Attorney Graham F. Putnam assisted by Ray Van Cott; the defendants were represented by attorney Will F. Wanless.9

After two days forjury selection the prosecution opened its case with several eyewitness accounts of the shooting; each identified Lynch as one of the three gunmen. Since Prowse's bullet had dropped Lynch to the floor to be found by police, mask on face, gun at hand, it was easy for the prosecutor to link him to the robbery and shooting. Linking King to the crime was more difficult. To establish that King was one of Lynch's masked accomplices, the prosecution relied mainly on the testimony of two eyewitnesses: Meyers and Wittenberg. The other potential witness, Frank Lyon, was not called to testify.10

When store clerk William Meyers took the stand he testified that on the afternoon prior to the shoot-

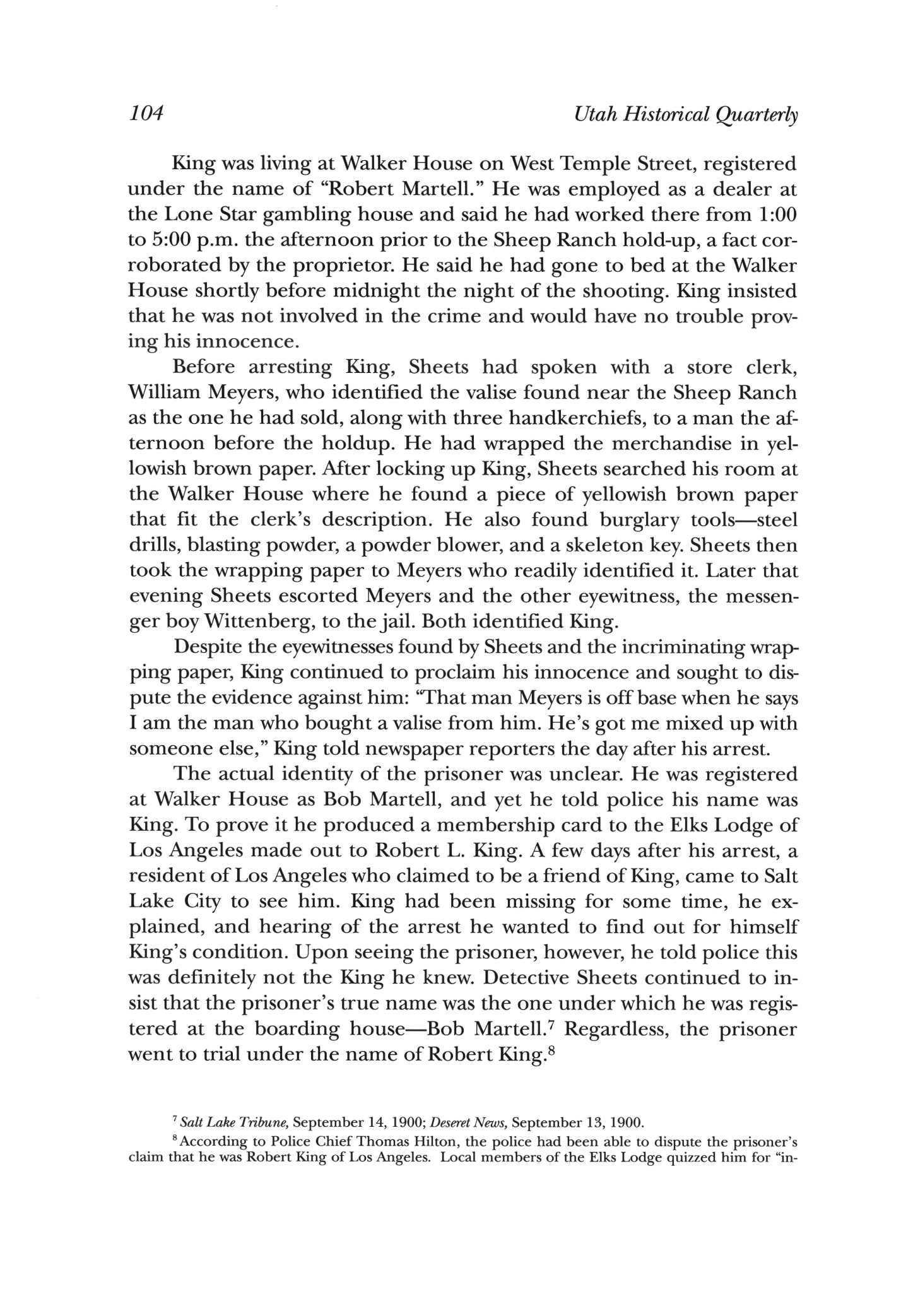

Drawings of Lynch and Martell, alias King, from the Salt Lake Tribune, September 12 and 15, 1900.

formation every Elk should have known" but which the prisoner was unable to provide In November it was reported that Chief Hilton had said the prisoner was from Seattle and was wanted for the murder of Robert L King Hilton said that in Seattle he had been known as Robert LaDue, Robert Duvalle, William Loto, R W LeBlanche, and R W Martello He said he was known as a "forger, a burglar, and all around crook." Deseret News, November 26, 1900

9 Deseret News, October 30, 1900.

10 Lyon had said he was positive that he could identify Lynch's two accomplices if he saw them again It is not known whether Lyon was ever asked if he recognized King It can be safely assumed, however, that if he had positively identified King he would have been called as another eyewitness for the prosecution

The Case of Lynch and King 105

ing a man had entered Cressman's clothing store and purchased three handkerchiefs and a valise, which Meyers had wrapped for him. The prosecutor displayed the paper found in King's room, and Meyers identified it, pointing to some small tears he said had been made by the string used to secure the package. Meyers also identified three handkerchiefs, including the one Lynch was wearing when he was arrested and two that were found in the Headquarters Saloon, as the same handkerchiefs he had sold on September 10.11

Next, the prosecutor asked the clerk to identify who had bought the valise and handkerchiefs "That man," said Meyers, pointing in King's direction. Since there were several people seated near King, a juror asked that "the man who was in the store stand up." "King, heard the [juror's] suggestion," wrote a Herald reporter, "and immediately started to rise from his chair. When about half straightened up he sud-

11

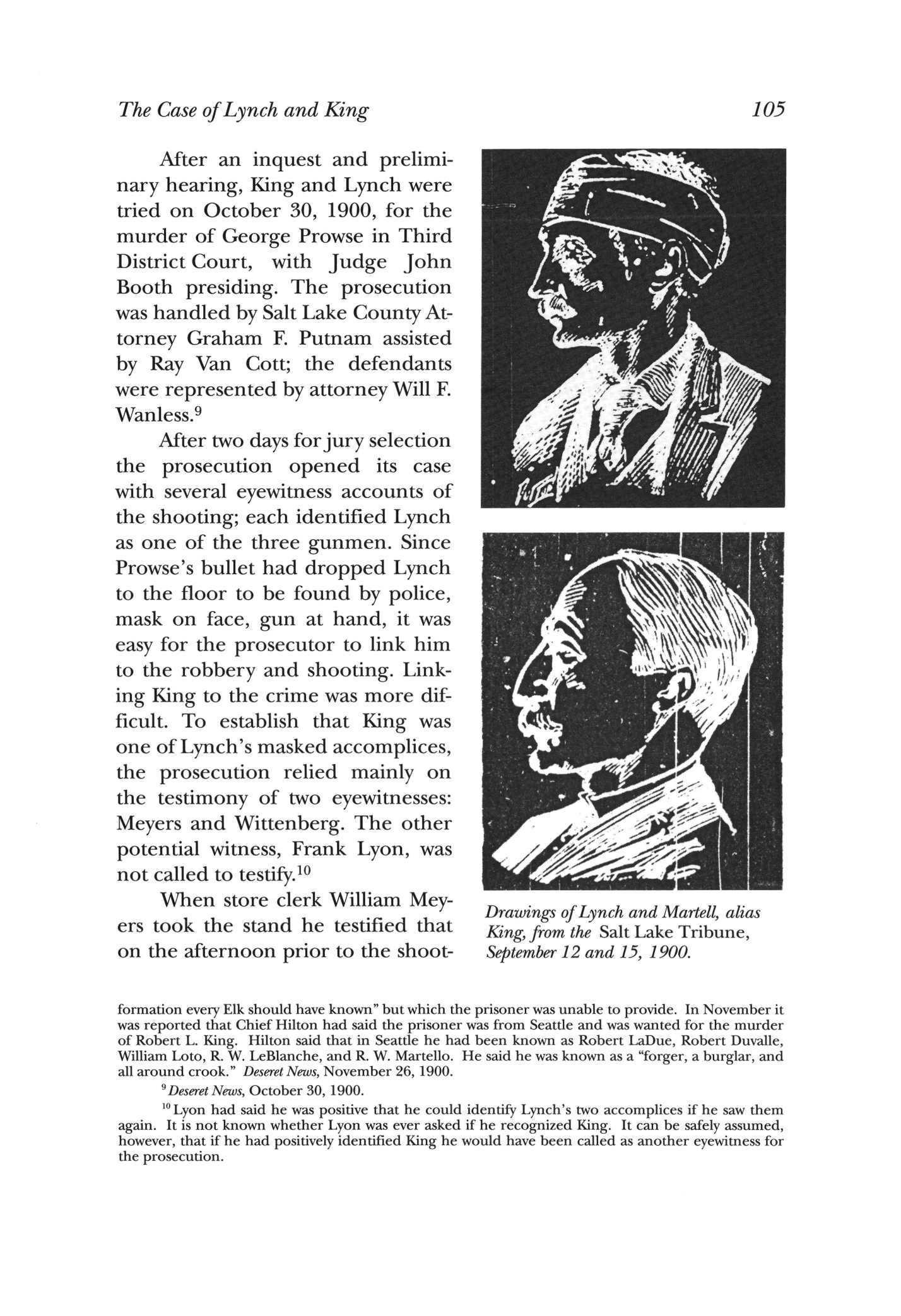

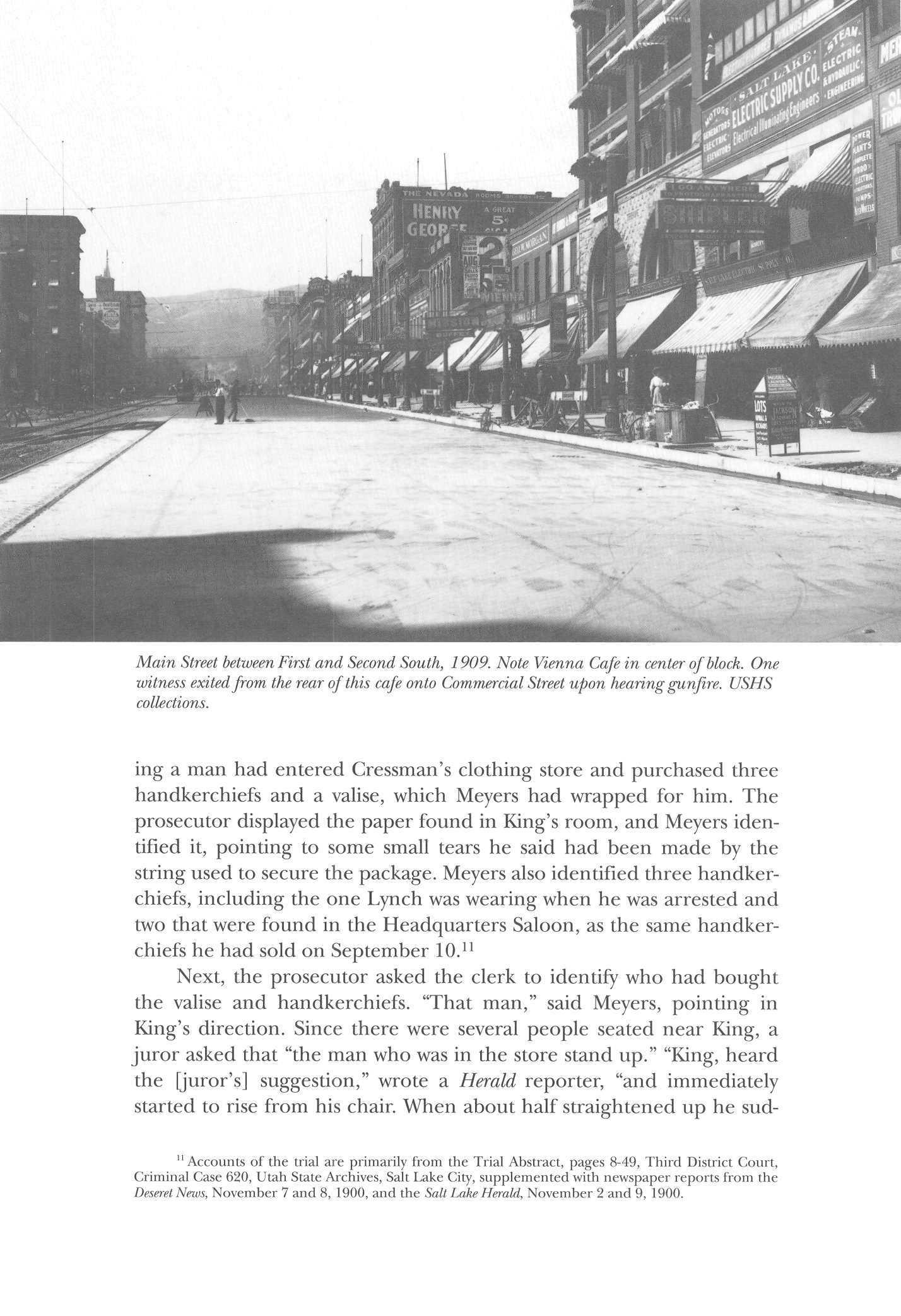

Main Street between First and Second South, 1909. Note Vienna Cafe in center of block. One witness exitedfrom the rear of this cafe onto Commercial Street upon hearing gunfire. USHS collections.

Accounts of the trial are primarily from the Trial Abstract, pages 8-49, Third District Court, Criminal Case 620, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, supplemented with newspaper reports from the Deseret News, November 7 and 8, 1900, and the Salt Lake Herald, November 2 and 9, 1900

denly realized what his act implied and resumed his seat, looking very uncomfortable, while a hushed titter passed 'round the courtroom."

In his cross-examination defense attorney Wanless sought to discredit the store clerk's powers of observation Meyers had testified that King's hands were not the hardened hands of a laborer. When asked how he remembered such a minute detail, Meyers demonstrated how King "took a handful of change from his pocket with his left hand, holding it up with the thumb toward the clerk, so that he could see the hand quite distinctly." Wanless pressed him further: "Did you notice any other peculiarity about the hand except its smoothness and delicateness?" he asked. "No sir,"was the clerk's reply. "Mr. King," Wanless said, "step up here and hold your hands up." King walked to the front of the courtroom and, facing thejury, raised his hands above his head. His left thumb had been cut off, leaving only a long scar.

After this cross-examination ended the prosecutor called his second key witness, William Wittenberg, who told the court that he was in the nearby Vienna Cafe at the time of the shooting. He testified that he heard the shots, stepped into the alley at the rear of the cafe, and saw two masked men running from the direction of the Sheep Ranch As they ran, he said, they removed the masks from their faces and disappeared into the back entrance of the Headquarters Saloon. Wittenberg then ran to the saloon's front door, walked in, and approached the two men who were now at the bar. One asked him tojoin him for a drink, the other left the saloon Both seemed very nervous, he said He identified King as one of the men.

During cross-examination Wanless asked Wittenberg how he knew the men were nervous. Wittenberg replied that he had noticed that King's hands were shaking but admitted he too had failed to see that the left thumb was missing

When it was the defense's turn, Wanless sought to damage the credibility of Wittenberg and Meyers. He began by challenging the conclusiveness of the paper found in King's room as evidence linking him to the crime. He called three witnesses. First, the owner of a Main Street clothing store testified that he used the same width and type of paper in his store Second, a clerk from the same store testified that he had sold a shirt to King and wrapped it in paper like that found in King's room. Third, the manager of the Utah Paper Company, which sold wrapping paper to Salt Lake merchants, testified that it would be impossible to tell which store the paper came from since many stores used exactly the same kind.

The Case of Lynch and King 107

To dispute Wittenberg's identification of King as the man he saw running through the alley and into the Headquarters Saloon, Wanless called on the proprietor and the desk clerk of the boarding house where King lived Both testified they had never seen King wearing clothes that matched Wittenberg's description and that a search of King's room had revealed no clothes of any kind. The only things they had ever seen King wear, they said, were the clothes he had on right then.

In his closing argument Wanless tried to shift responsibility for the crime to the local police and city government by blasting their toleration of gambling in Salt Lake City, noting that it was in direct violation of Utah law "The police and county attorney are sworn to uphold the laws," he declared; and "If they had done their duty there would have been no Prowse murder and no murder trial." Concluding, he told the jury that, at most, Lynch was guilty of manslaughter and King merited acquittal.

In considering the defense, it is striking that Wanless did not attempt to establish an alibi for King. Newspapers reported at the time of King's arrest that he claimed to have an alibi that would prove his innocence. King said he had been working at the Lone Star gambling house during the time Meyers claimed to have sold him the valise and handkerchiefs The proprietor of the Lone Star had corroborated this fact for the Salt Lake Herald, yet Wanless did not seek to establish it in court According to King, he had entered his room at the boarding house some two hours before the shooting and had passed the boarding house proprietor, Mr. Dudley, on the stairs. Someone would have noticed if he had left that night, King had argued. The defense also failed to present this evidence to the jury; nor was King put on the stand to testify in his own defense.12

On November 8, the eighth day of the trial,Judge Booth gave the jury formal instructions. It took only a few minutes for them to find Lynch guilty as charged. Initially, eleven jurors voted to convict King as charged, and one juror voted to convict him of second degree murder. The jury deliberated for two hours. A second ballot was taken, and this

12 Three years later, in a newspaper interview, King was very critical of the way the defense at his trial had been handled: "I was railroaded I do not blame the court or the jury They could say if I had witnesses to prove my innocence, why did I not put them on the stand? I wanted to have a separate trial; I wanted to put witnesses on the stand; witnesses who were well known and highly respected, who would have testified that I was with them on the night of the crime But my attorney said no 'We won't need them, you cannot be convicted,' he said The first thing I knew it I was 'guilty.'" Deseret News, October 23, 1903

108 Utah Historical Quarterly

time, all twelve agreed to find King as well as Lynch guilty of murder in the first degree. 1 3

When the verdict was read, King, according to press accounts, slumped in his chair and looked nervous and pale. Lynch sighed and "settled back into his usual indifferent attitude."

Leaving the courtroom, King and Lynch were asked by reporters for their reaction Lynch had no comment, but King lashed out in what one account called "a volley of blasphemous abuse" against the jurors: "God-damn them, every one of them," King "hissed" between clenched teeth "They're trying tojob us, but I'll show them The police, the sons of bitches,jobbed me, that's all."

Within a few days of the verdict Wanless filed a motion for a new trial with Judge Booth based on a number of supposed procedural errors On November 13 Booth denied the motion, saying he would make the same decisions again if a new trial were held.

Sentencing was held on November 15, scarcely two months after George Prowse had been killed Before rendering the sentence, Judge Booth asked each man in turn if he had anything to say. Lynch declined, but King responded by professing his innocence, claiming he was "bagged and brought in and placed in this position by Detective Sheets." Booth responded that "if it is a fact, Mr. King, that you are innocent, it is known only to you and to Lynch." Concluding, the judge said King and Lynch had "had a fair trial and were found guilty" and therefore "I have no discretion in the matter." Booth asked Lynch and King if they understood that the death penalty was the punishment affixed to this crime and then informed them that under Utah law they had "the privilege of choosing whether you care to be hung or shot." Both chose the firing squad over the gallows, and the judge set their execution date for January 11, 1901. Wanless told reporters he would appeal to the Utah State Supreme Court and hoped to place the matter before the court as soon as possible. King and Lynch were returned to jail where they were placed under the customary "death watch." While the pair waited for their case to be reviewed by the Utah Supreme Court, theirJanuary execution date came and went uneventfully A year later they were still waiting, but by then new developments in the case made it appear that at least Robert King might yet live to see many more Januarys

The Case of Lynch and King 109

"Accounts of verdict and sentencing are from Deseret News, November 9, 13, and 15, 1900; Salt Lake Herald, November 9 and 16, 1900; and Salt Lake Tribune, November 9 and 16, 1900.

Sometime during 1901 King secured the help of the government of Italy He had written the Italian ambassador in Washington, telling him that his real name was "Pedro Paguini"—a member of a distinguished Italian family—and that he was being held in Utah under sentence of death for a crime he had not committed As an Italian subject he solicited the help of his government in correcting this injustice. In September the ambassador instructed the Italian consul in Denver, Joseph Cuneo, to investigate the case. That fall Cuneo traveled to Utah, met with King and attorney Wanless, and provided funds for a private investigator to help uncover evidence that might lead to King's release.14 This Italian connection solidified as King succeeded in enlisting the support of Charles Bonetti, a prominent Italian-American resident of Salt Lake Bonetti rallied the support of the city's Italian community, which, according to one account, "became vehement in its protestations of innocence of its countryman . . . [and] ready to offer any aid in its power."15

King also acquired the help of an unlikely ally—Salt Lake City Police Chief Thomas Hilton who had been persuaded of King's innocence by a telegram he received in the summer of 1901 from the deputy warden of the Colorado penitentiary in Canon City that contained the story ofJohn Mace, an inmate there. Mace claimed King was innocent, having been mistaken for another Colorado inmate, John Strange. He was coming forward to reveal publicly what he knew, Mace said, because he had learned that King was about to be executed for a crime John Strange had bragged about committing.16

During the next several months, Chief Hilton, Consul Cuneo, and defense attorney Wanless combined their efforts to verify the Colorado

'"DeseretNews, February 17, 1902

15 Salt Lake Herald, February 18, 1902

16Deseret News, February 17, 1902

110 Utah Historical Quarterly

Chief Thomas H. Hilton. USHS collections.

convict's story. On February 13John Mace signed an affidavit attesting to Strange's confession to him of King's innocence On February 17 the Mace affidavit was made public.

In the affidavit Mace asserted that he was in Ogden, Utah, the day after the Sheep Ranch hold-up That evening he took a train east to Rawlins, Wyoming. On board he encountered Ed Davenport, whom he had met a week earlier in Ogden, and his partner John Strange. They told Mace that they were the two men wanted for the Sheep Ranch hold-up in Salt Lake. Strange told him "that he was the man who 'pumped' it into Prowse when he saw one of the 'lads' [Lynch] on the floor who was shot." Later, when Mace and Strange were serving time in the Colorado penitentiary, Strange told him that King had been convicted, which was the first Mace had known about it. Strange "laughed about it and said: 'Well King is innocent but they can do nothing with me . . . now.' "Strange said, " T am the man; I bought the valise . . .handkerchiefs and so forth. . . . ' "17

This new evidence made a powerful impact. King took the news of Mace's affidavit as the vindication he had long sought. Interviewed by reporters, King said "it was the happiest news I ever received in my life. Had it come a little later, I would have been dead and in a dishonored grave. ... It is an awful thing to be condemned to die for a crime that you never committed."

Not everyone believed Mace's affidavit, however, or felt it proved King's innocence. District Attorney Dennis Eichnor said the affidavit "reads . . . like a dime novel story and a mighty poor one at that." George Sheets, the detective who arrested King, said King was tried with the evidence "placed before as fair ajury as could be gotten anywhere, and they found him guilty." Surely a jury's judgment should mean more than the statement of a convict Similarly, Assistant County Attorney Frederick Loofbourow called the affidavit a convict's "trick," saying crooks "will go to great lengths to help one another out of trouble."18

Although these officials scoffed at the Mace affidavit, others, including Utah's governor, Heber M. Wells, took it seriously. Elected as the state's first chief executive when Utah achieved statehood in 1896, Wells was now in his second term and had held various public offices for almost twenty years. Called "a staunch friend of law and order" in

The Case of Lynch and King 111

I7 John Mace Affidavit, February 13, 1902, Third District Court, Criminal Case 620 18 Accounts of the reactions to the Mace Affidavit are from the Salt Lake Herald, February 18, 1902, the Salt Lake Tribune, February 18, 1902, and the Deseret News, February 21, 1902.

one contemporary biography,19 Wells, the son of Utah pioneer leader Daniel H. Wells, was also one of the state's most respected citizens.

The morning after the Mace affidavit became public Governor Wells met with other top government officials to evaluate the case and discuss what should be done. Meeting with the governor were Secretary of State James T Hammond, Attorney General M D Breeden, Salt Lake County Attorney Parley P. Christensen, District Attorney Eichnor, Police Chief Hilton, the deputy warden of the Colorado prison where Mace was held, and defense attorney Wanless After considerable deliberation, which included a fervent plea in King's behalf by the police chief, they concluded that further investigation was needed before Strange could or should be brought back to the state.20

The next day, February 19, 1902, attorney C M Garwood—hired by Consul Cuneo to assist in King's defense—arrived in Salt Lake City from Denver.21 That afternoon Garwood visited Lynch in prison, and Lynch agreed to sign an affidavit attesting to King's innocence.

"He [King] is absolutely innocent and had nothing to do with the affair at all," Lynch stated; and "He has suffered for a crime he knew nothing about." Lynch also said that he and King had gone to trial together for financial reasons and that he had "told King that I did not see how he could be convicted and if he was I would some day tell all that happened and that would prove his innocence." 2 2

Why Lynch waited eighteen months to tell the world of King's innocence remains an unanswered question Police Chief Hilton had met with Lynch a week earlier and tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to corroborate Mace's story.23 Although now willing to testify of King's innocence, Lynch continued to be either unwilling or unable to name his accomplices. In speaking of his affidavit, Lynch said he was not "positive of the complicity" of Strange and Davenport, noting that he did not remember his accomplices "as distinctly as I once did." Lynch said his sole purpose in making a statement was to save the life of King, an innocent man. As for himself, Lynch said, "I am condemned to die and wish the thing were over." He realized "only too well that it is a matter of a very short time 'till it is over with me "24

19 Drumm's Manual of Utah and Souvenir of theFirst State Legislature, 1896, Special Collections, University of Utah Library, Salt Lake City

20 Salt Lake Tribune, February 19, 1902

21 Deseret News, February 19, 1902

22James Lynch Affidavit, February 19, 1902, Third District Court, Criminal Case 620.

23 Deseret News, February 17, 1902

24 Salt Lake Herald, February 20, 1902

112 UtahHistorical Quarterly

The affidavits of Mace and Lynch attesting to King's innocence were published in the Salt Lake newspapers. This testimony, though from two convicts, cast doubt on King's guilt and caused one of the key prosecution witnesses, William Wittenberg, to recant his testimony. After seeing a photograph ofJohn Strange, Wittenberg stated in an affidavit, he was "firmly convinced beyond a doubt in my own mind that the man whose photograph is attached [Strange] .. . is the identical person whom I saw enter said saloon after shooting Colonel Prowse, and that the defendant Robert L. King is not the man."

Wittenberg explained why he was now positive that the man he had seen eighteen months earlier was Strange, after seeing only a photograph, when at the trial he had seemed equally certain of King's identity: "In my own conscience I then felt an uncertainty as to King being the man, but others said to me, 'We know he is the man and so do you.' " Furthermore, he said, "The influence being brought to bear on me was the principle [sic] reason I identified King. . . ,"25 Wittenberg told the Salt Lake Herald that "the more he thought of the part he took in the prosecution of King the more it has burned his conscience."26

Wittenberg had recently started working for Charles Bonetti—the same man who was president of Salt Lake's Italian colony and an ardent advocate of King's innocence. Although Wittenberg's troubled conscience may have been behind his decision to come forward to help clear King, Bonetti likely influenced him Bonetti's insistence that King was innocent and his civic activities to raise money to aid King's defense may well have affected Wittenberg, especially when the publicity surrounding the Mace affidavit called into question King's guilt It was Bonetti who informed Chief Hilton that Wittenberg wished to sign an affidavit changing his testimony, and it was Bonetti who notarized Wittenberg's affidavit.

With new evidence pointing to King's innocence, some suggested a pardon might be appropriate Attorney Wanless ruled it out He said King not only would not ask for a pardon but that he would not accept one if offered. "A pardon always carries the impression that a man is guilty but has been punished enough," Wanless stated; "King will not leave the penitentiary until he has been fully exonerated."27

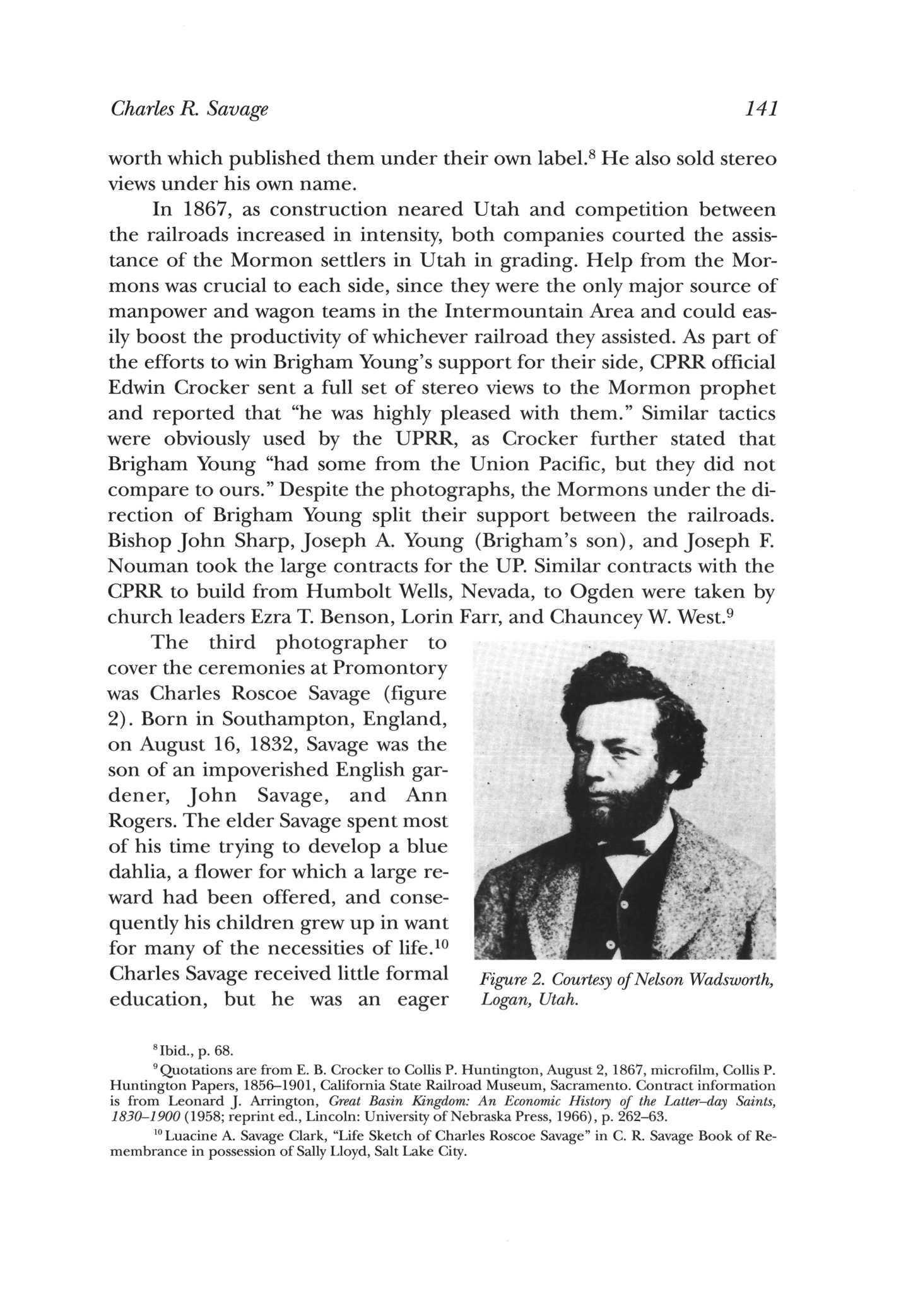

To either verify or disprove the charges made in Mace's affidavit, County Attorney Christensen and Sheriff Naylor traveled to Colorado on

The Case of Lynch and King 113

25 William Wittenberg Affidavit, February 20, 1902, Third District Court, Criminal Case 620 26 Salt Lake Herald, February 21, 1902 27 Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 1902

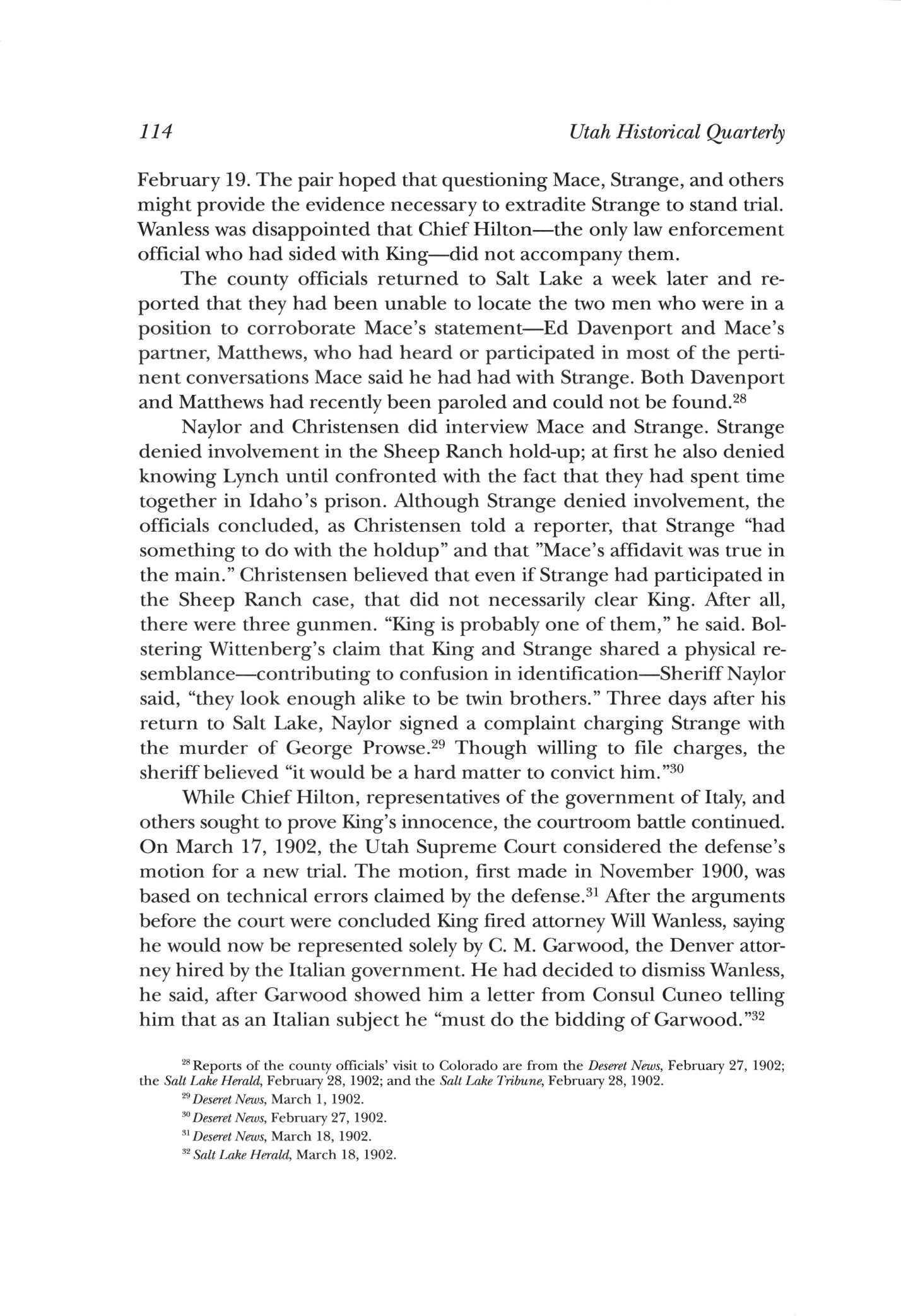

February 19.The pair hoped that questioning Mace, Strange, and others might provide the evidence necessary to extradite Strange to stand trial Wanless was disappointed that Chief Hilton—the only law enforcement official who had sided with King—did not accompany them.

The county officials returned to Salt Lake a week later and reported that they had been unable to locate the two men who were in a position to corroborate Mace's statement—Ed Davenport and Mace's partner, Matthews, who had heard or participated in most of the pertinent conversations Mace said he had had with Strange. Both Davenport and Matthews had recently been paroled and could not be found.28 Naylor and Christensen did interview Mace and Strange. Strange denied involvement in the Sheep Ranch hold-up; at first he also denied knowing Lynch until confronted with the fact that they had spent time together in Idaho's prison. Although Strange denied involvement, the officials concluded, as Christensen told a reporter, that Strange "had something to do with the holdup" and that "Mace's affidavit was true in the main." Christensen believed that even if Strange had participated in the Sheep Ranch case, that did not necessarily clear King. After all, there were three gunmen "King is probably one of them," he said Bolstering Wittenberg's claim that King and Strange shared a physical resemblance—contributing to confusion in identification—Sheriff Naylor said, "they look enough alike to be twin brothers." Three days after his return to Salt Lake, Naylor signed a complaint charging Strange with the murder of George Prowse.29 Though willing to file charges, the sheriff believed "it would be a hard matter to convict him."30 While Chief Hilton, representatives of the government of Italy, and others sought to prove King's innocence, the courtroom battle continued. On March 17, 1902, the Utah Supreme Court considered the defense's motion for a new trial The motion, first made in November 1900, was based on technical errors claimed by the defense.31 After the arguments before the court were concluded King fired attorney Will Wanless, saying he would now be represented solely by C M Garwood, the Denver attorney hired by the Italian government. He had decided to dismiss Wanless, he said, after Garwood showed him a letter from Consul Cuneo telling him that as an Italian subject he "must do the bidding of Garwood."32

114 Utah Historical Quarterly

28,

Neivs,

1, 1902

News,

28 Reports of the county officials' visit to Colorado are from the Deseret News, February 27, 1902; the Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1902; and the Salt Lake Tribune, February

1902 29 Deseret

March

30Deseret

February 27, 1902 31 Deseret News, March 18, 1902 32 Salt Lake Herald, March 18, 1902

Wanless, who had defended King along with Lynch for nearly two years pro-bono, was bitter about losing King as a client just as money had become available to assist with the defense.33 He vowed to continue to fight for Lynch's life. Making a veiled threat, he said he would now feel free to act in Lynch's behalf regardless of the effect his actions might have on King.34

On March 28, 1902, the Utah Supreme Court rejected the motion for a new trial and unanimously upheld the convictions of both King and Lynch, stating that "upon the whole record, no reversible error was found." In turning down the appeal the justices ordered the district court to "execute the sentence in accordance with law."35

Although the court's decision was unfavorable, Will Wanless was not disheartened. He believed that the new evidence in support of King could also be used to benefit Lynch. Confident that a new trial would be ordered, the attorney insisted, "You may rest assured, Lynch will not be shot." The next day he, District Attorney Eichnor, and County Attorney Christensen met with Lynch at the state prison.36 No one knows exactly what Lynch told these men, but the press reported that Lynch "punctured the affidavit ofJohn Mace" and convinced authorities that Strange had nothing to do with the Sheep Ranch hold-up.

Lynch's statements were made without any offer of immunity and in line with Wanless's new policy of "doing everything for his client regardless of the effect it may have on others," namely King.37 Lynch did not recant his previous affidavit swearing to King's innocence; however, neither did he reveal the actual identity of his accomplices.

After consideration of Lynch's statements during the March 29 meeting, Salt Lake County dropped its charges against John Strange,

ss In an attempt to receive at least some payment for his work in behalf of King, Wanless wrote letters to Colorado's two U.S. senators and Italy's ambassador in Washington, asking whether Cuneo and Garwood were acting in compliance with the ambassador's instructions in firing Wanless from the case. It is not known whether they responded or whether Wanless ever received any payment from the Italian government. DeseretNews, March 19, 1902.

34 Wanless reacted sharply to the news of his dismissal: "For a year and a half I have fought for King without any pay whatever Now that the case is practically won and there is a little money in sight, Garwood and Cuneo step in." Wanless said that Lynch was also "indignant" that King would remove Wanless from the case, and the attorney stated it was now "exceedingly doubtful" that Lynch would say anything more that might benefit King (Salt Lake Tribune, March 18, 1902) In a parting shot, Wanless remarked that he wondered what the Italian government would do "should they discover that he [King] is not an Italian, but an American-born Louisiana Creole" (Salt Lake Herald, March 18, 1902)

35 Reports of the Supreme Court decision are from the Deseret News, March 28, 1902, and the Salt Lake Herald, March 29, 1902

36 Lynch and King were admitted to the state prison on May 1, 1901 Prior to that time they were incarcerated in the Salt Lake Cityjail.

3''Salt Lake Tribune, March 30, 1902

The Case of Lynch and King 115

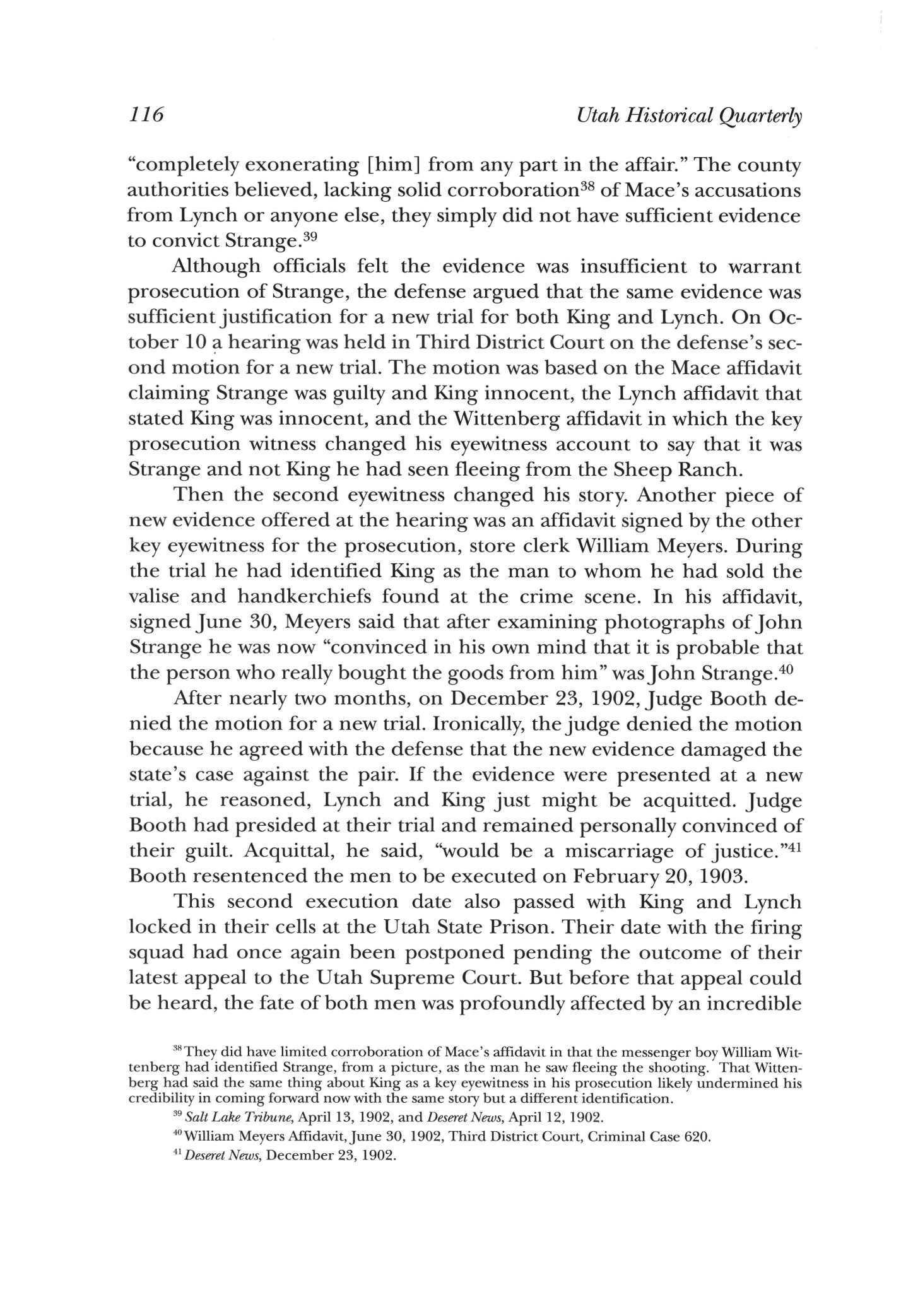

"completely exonerating [him] from any part in the affair." The county authorities believed, lacking solid corroboration38 of Mace's accusations from Lynch or anyone else, they simply did not have sufficient evidence to convict Strange.39

Although officials felt the evidence was insufficient to warrant prosecution of Strange, the defense argued that the same evidence was sufficient justification for a new trial for both King and Lynch. On October 10 a hearing was held in Third District Court on the defense's second motion for a new trial. The motion was based on the Mace affidavit claiming Strange was guilty and King innocent, the Lynch affidavit that stated King was innocent, and the Wittenberg affidavit in which the key prosecution witness changed his eyewitness account to say that it was Strange and not King he had seen fleeing from the Sheep Ranch.

Then the second eyewitness changed his story. Another piece of new evidence offered at the hearing was an affidavit signed by the other key eyewitness for the prosecution, store clerk William Meyers. During the trial he had identified King as the man to whom he had sold the valise and handkerchiefs found at the crime scene. In his affidavit, signed June 30, Meyers said that after examining photographs of John Strange he was now "convinced in his own mind that it is probable that the person who really bought the goods from him" wasJohn Strange.40

After nearly two months, on December 23, 1902,Judge Booth denied the motion for a new trial. Ironically, thejudge denied the motion because he agreed with the defense that the new evidence damaged the state's case against the pair If the evidence were presented at a new trial, he reasoned, Lynch and King just might be acquitted. Judge Booth had presided at their trial and remained personally convinced of their guilt. Acquittal, he said, "would be a miscarriage of justice."41 Booth resentenced the men to be executed on February 20, 1903. This second execution date also passed with King and Lynch locked in their cells at the Utah State Prison. Their date with the firing squad had once again been postponed pending the outcome of their latest appeal to the Utah Supreme Court. But before that appeal could be heard, the fate of both men was profoundly affected by an incredible

38 They did have limited corroboration of Mace's affidavit in that the messenger boy William Wittenberg had identified Strange, from a picture, as the man he saw fleeing the shooting That Wittenberg had said the same thing about King as a key eyewitness in his prosecution likely undermined his credibility in coming forward now with the same story but a different identification

39 Salt Lake Tribune, April 13, 1902, and Deseret News, April 12, 1902

40William Meyers Affidavit, June 30, 1902, Third District Court, Criminal Case 620.

41 Deseret News, December 23, 1902

116 Utah Historical Quarterly

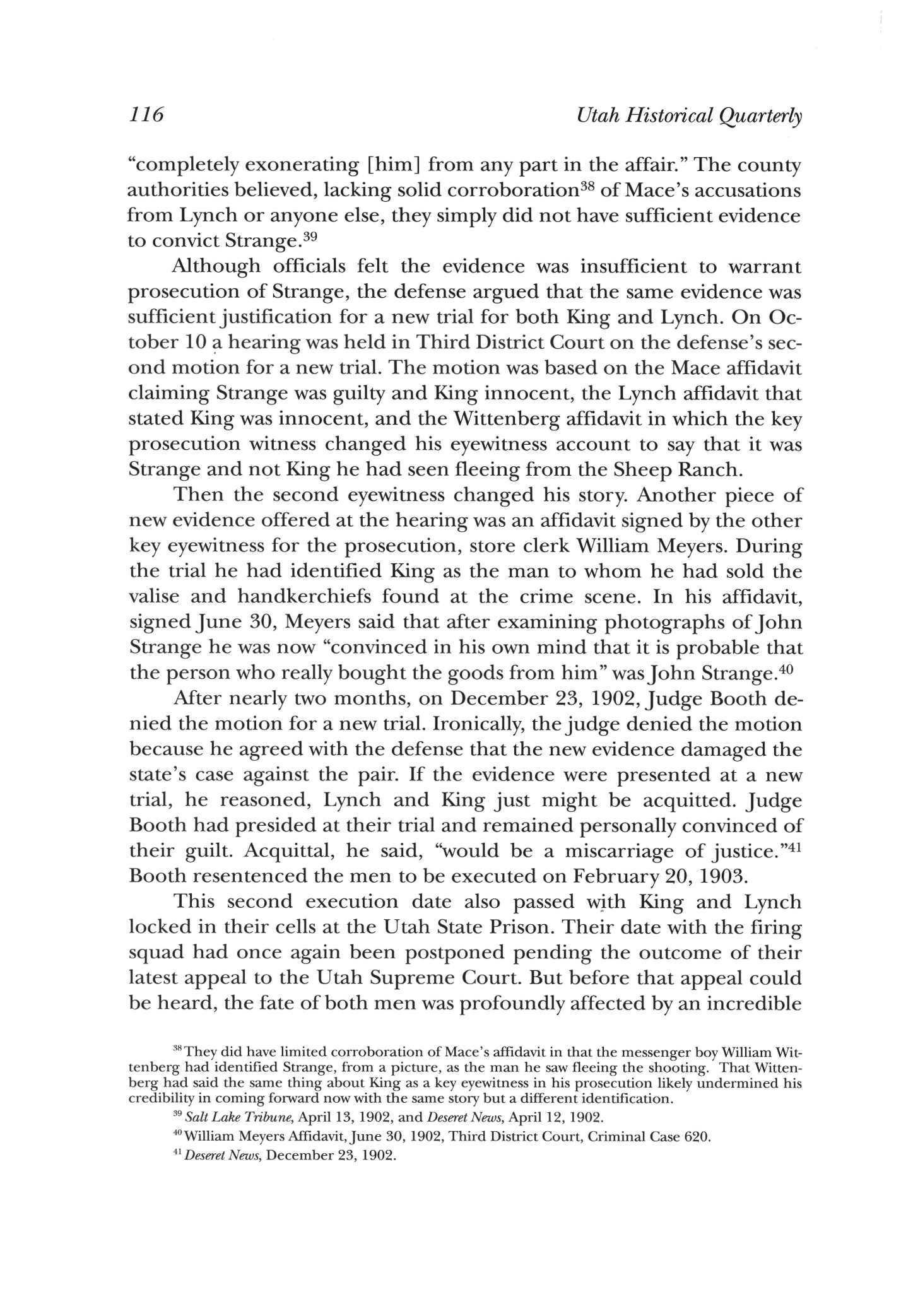

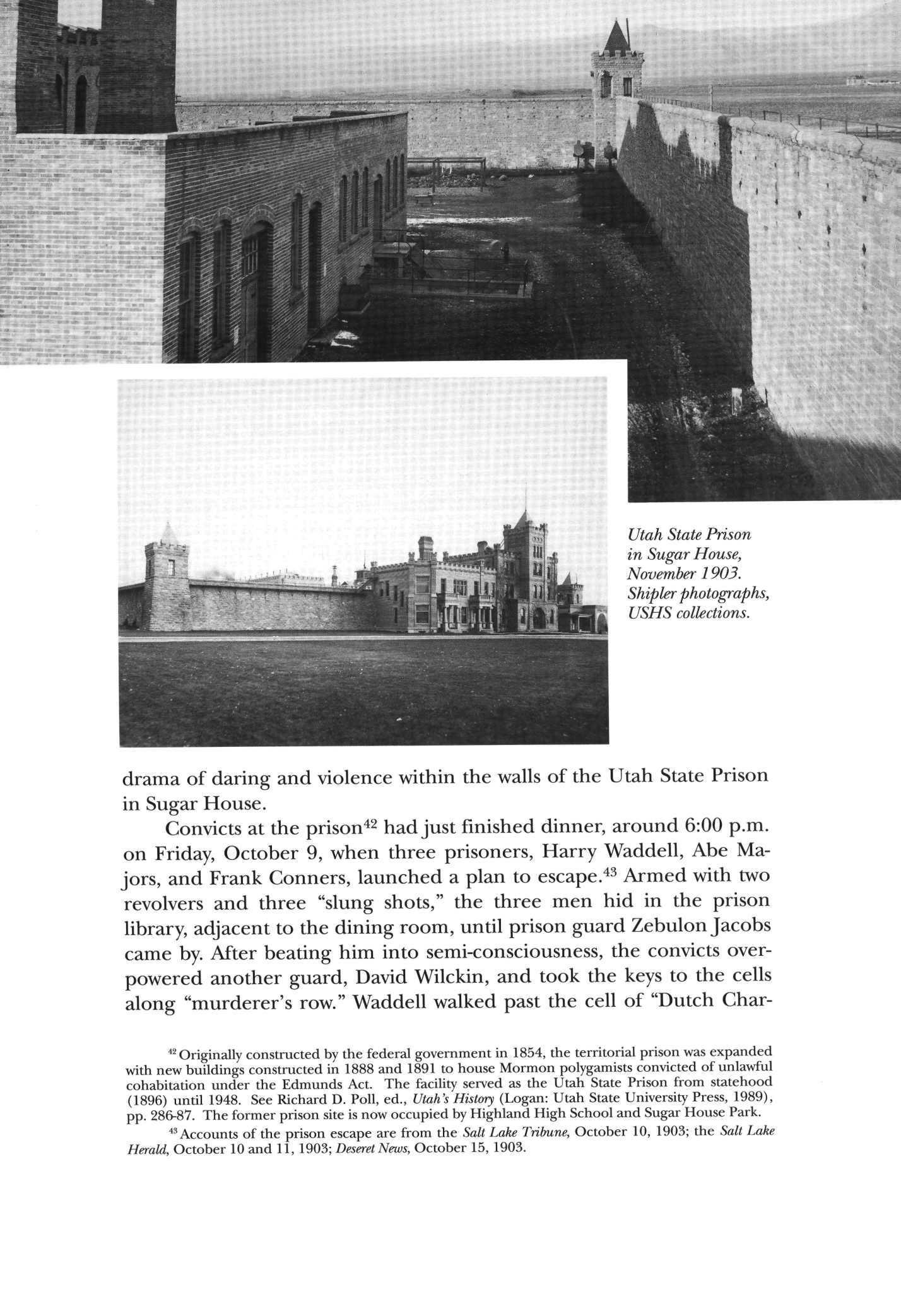

Utah State Prison in Sugar House, November 1903.

Shipler photographs, USHS collections.

drama of daring and violence within the walls of the Utah State Prison in Sugar House.

Convicts at the prison42 hadjust finished dinner, around 6:00 p.m. on Friday, October 9, when three prisoners, Harry Waddell, Abe Majors, and Frank Conners, launched a plan to escape. 43 Armed with two revolvers and three "slung shots," the three men hid in the prison library, adjacent to the dining room, until prison guard Zebulon Jacobs came by. After beating him into semi-consciousness, the convicts overpowered another guard, David Wilckin, and took the keys to the cells along "murderer's row." Waddell walked past the cell of "Dutch Char-

42 Originally constructed by the federal government in 1854, the territorial prison was expanded with new buildings constructed in 1888 and 1891 to house Mormon polygamists convicted of unlawful cohabitation under the Edmunds Act The facility served as the Utah State Prison from statehood (1896) until 1948. See Richard D. Poll, ed., Utah's History (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1989), pp 286-87 The former prison site is now occupied by Highland High School and Sugar House Park

43 Accounts of the prison escape are from the Salt Lake Tribune, October 10, 1903; the Salt Lake Herald, October 10 and 11, 1903; DeseretNews, October 15, 1903

lie" Botha, facing a death sentence44 for killing his wife and her "paramour," and approached the cell occupied byJames Lynch. "What the hell's up?" asked Lynch. "Get your clothes on," Waddell yelled. "There's a break, come along."

As Lynch walked out of his cell, Waddell handed him the keys and told him to let out another convicted murderer, Nick Haworth. Lynch opened Haworth's cell and then approached the cell of Robert King. Lynch told him "there was a break and he stood a good chance to escape." Remarkably, King refused, saying, "I do not care to go. ... I am innocent and will lose nothing by staying where I am." Another convicted murderer, Peter Mortensen, who was facing execution in less than six weeks for killing his wife, begged to be released but his fellow convicts refused.45

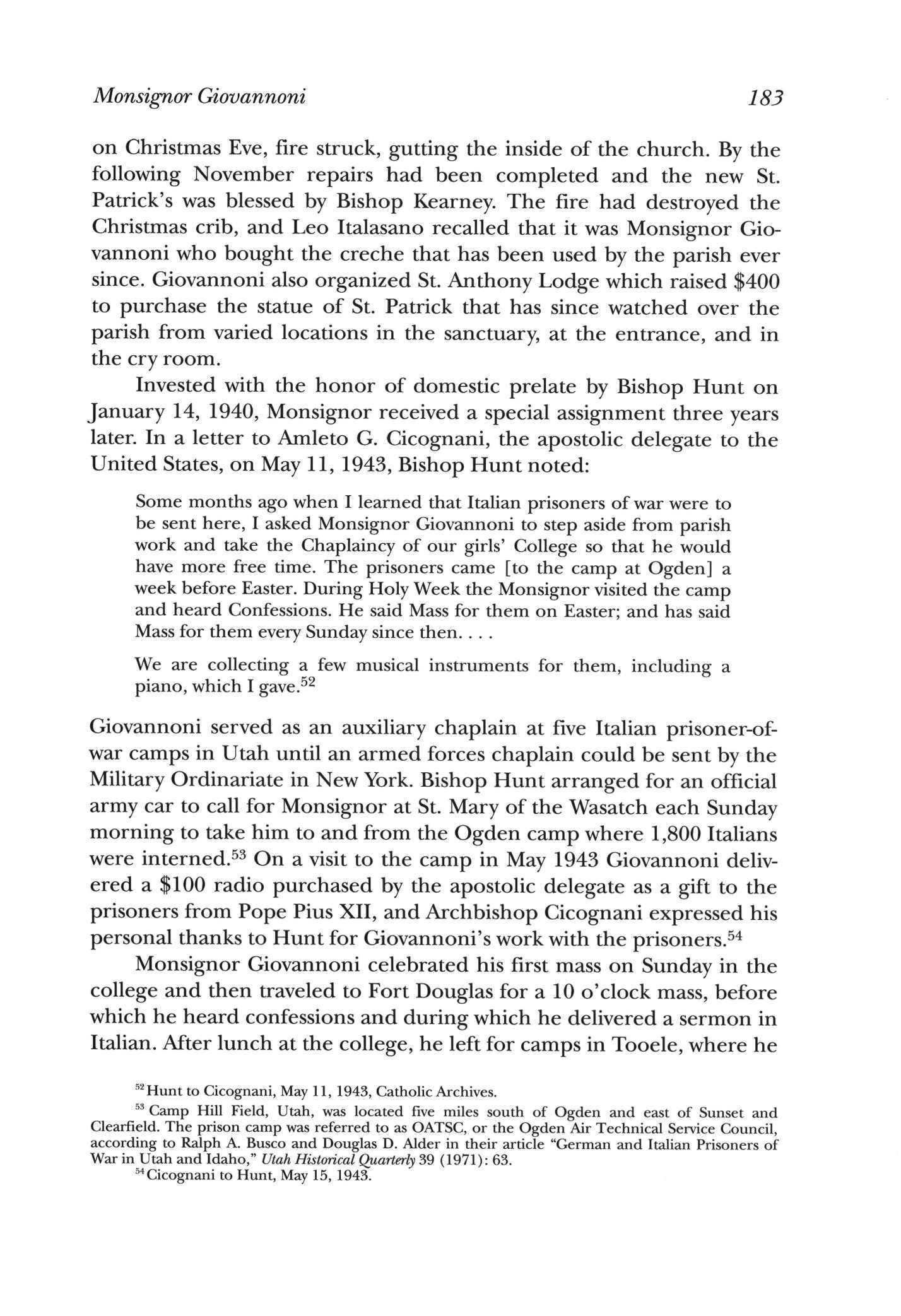

Lynch then joined Waddell, Majors, and Conners who had just finished dragging the guard Jacobs to the south cell house. "Well, what shall we do with him?" one of the prisoners asked. "Guess we had better finish him right here," the other replied Seeing the badly bleeding guard, Lynch intervened. "Here boys, this won't do; there is no need.. .. it will only aggravate this business." Waddell and Majors agreed to spare the old guard's life

Seven prisoners ran for the outer wall of the prison grounds One of them had secured a ladder. Lynch, first on the ladder, was shot in the arm by one of the prison guards as he reached the top of the wall. Though the impact almost knocked him over, he managed to slide down the outside of the wall and run to freedom. Haworth was right behind him. In a hail of gunfire the remaining five convicts took turns climbing the nineteen-foot wall Most made it but were unable to get past two guards who scurried to the outside and positioned themselves at the base of the wall directly below the ladder.

Only an hour after the prison break began the siege was over. Three guards and five prisoners were injured. One prisoner was dead. Only two had succeeded in escaping the immediate area of the prison—James Lynch and Nick Haworth.

Guard Zebulon Jacobs's wounds were serious though not life threatening. He had two scalp wounds—so deep that his skull was exposed—each several inches long Above one eye another cut had bled

118 Utah Historical Quarterly

44 Botha's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the Board of Pardons on June 8, 1904.

45 Mortensen was executed, as scheduled, on November 20, 1903, a mere fourteen months after the murder

profusely, and on his right cheek was another cut that was not very deep He told reporters that Lynch had saved his life

Almost immediately after Lynch and Haworth had dashed to freedom that Friday evening, a posse of twenty men started hunting for them The next morning a fresh posse embarked, supplemented with bloodhounds. Many others volunteered to assist the manhunt. It did not take long. On Sunday, October 11, Haworth was captured in Holladay, a few miles south of the prison. On Wednesday, October 14, Lynch, haggard, weak, and going door to door begging for food, was identified and taken into custody in Woods Cross,46 a small community a few miles north of Salt Lake City

While Lynch was on the loose, his attorney, Will Wanless, went before the Utah Supreme Court as scheduled on Monday to argue for a new trial.47 Prior to the hearing, Wanlessjoked with King's attorneys about the prison break. "Lynch is out hunting new evidence to be used in his new trial which the supreme court is going to grant him," Wanless quipped, which wasmet by "ahearty laugh from allwho were near enough to hear."

While conceding that the new evidence presented to the Supreme Court dealt only with King's guilt and not Lynch's, Wanless argued that since both were originally tried together, if King were granted a new trial, so must Lynch.48 This logic failed to persuade the court On October 23 it granted King a new trial but upheld Lynch's conviction. The court expressed "doubt as to whether . . . King would ever have been convicted without the testimony of Meyers and Wittenberg."49 No evidence had been presented that disputed or questioned Lynch's involvement in the shooting Accordingly, Lynch's conviction stood King and Lynch were brought before Judge Booth in Third District Court once again on November 18. District Attorney Eichnor moved to dismiss the charges against King due to insufficient evidence. Judge Booth granted the motion and all charges against King were dropped Booth then sentenced Lynch to be executed on Friday,January 8, 1904.50 Robert King wasjubilant. Imprisoned for over three years, he repeated his claim of innocence and said that he "knew it was only a question of time" before he would be released. He said he was going back to

46 Deseret News, October 15, 1903

47 Deseret News, October 12, 1903

48 Deseret News, October 12, 1903

49 Deseret News, October 23, 1903

50 Accounts of the court's ruling and reaction to it are from the Salt Lake Telegram, November 18, 1903; Salt Lake Herald, November 19, 1903; and Salt Lake Tribune, November 19, 1903

The Case of Lynch and King 119

Italy for a few months to see his friends and family and to "tell them of my life here, and how I was in prison and was to die for a crime that I did not do." And then what? "I will come back to America It is a good place and I want to live here."

Lynch, back in prison and facing execution for the third time, told reporters his attorney would ask the Board of Pardons to change his sentence to life imprisonment. If the board denied his request, Lynch said, "I suppose I will have to take my medicine like a man."

True to that pledge his application for commutation came before the State Board of Pardons 5 1 on Saturday, December 19, 1903. Even though no new evidence had emerged bearing on Lynch's involvement, his attorney was able to show that nearly every member of the jury that had convicted him now wanted him spared the sentence they had imposed. Wanless presented the board with letters supporting commutation signed by ten of the twelve jurors He also presented a petition signed by a number of the state's most prominent citizens, including the mayor of Salt Lake City, and other city and county officials.

It is both unusual and remarkable that prominent citizens would come to the defense of a drifter who was obviously guilty of participating in a hold-up and shooting that resulted in a man's death. Ironically, support for Lynch can be traced to events surrounding his escape from prison when he intervened to save the life of prison guard Zebulon Jacobs. In savingJacobs, Lynch had saved the life of a prominent and respected citizen. Zebulon Jacobs, at age sixty-one, was one of the last surviving of Utah's early pioneers Born in the Mormon settlement of Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1842,Jacobs came to Utah in 1848 with his mother, Zina Diantha Huntington Young, a plural wife of Brigham Young.52 Zina was, in her own right, one of Utah's most respected women Well known throughout the territory, having been "set apart" by church leaders as a midwife, she personally helped bring hundreds of babies into the world In 1880 she became president of the Deseret Hospital In 1892 she became the third woman to head the Relief Society—the women's auxiliary of the Mormon church—a position she held until her death in 1901.53 When Lynch savedJacobs's life, Zina D. H. Young, dead only two

52 Salt Lake Herald, September 23, 1914

53 Deseret Nezvs, August 28, 1901

120 Utah Historical Quarterly

51 Under Utah's constitution Governor Wells did not have the sole power to grant pardons or to commute sentences. This power was shared with the justices of the Supreme Court and the attorney general who, along with the governor, constituted the Board of Pardons

years, was still fresh in the memories of most Utahns.54 As a youth Zebulon Jacobs had lived in the Lion House, built by his stepfather, Brigham Young.55 He was a veteran of the Black Hawk Indian War, Mormon missionary to England, former railroad worker, and Utah pioneer.56 As the son of "Aunt Zina" Young, he had a special place in the hearts of many Utahns.

Jacobs himself now actively petitioned the Board of Pardons to prevent Lynch's execution.57 In addition, the acting warden of the prison told the board that both before and after the prison break Lynch had been a "model prisoner."58 Despite this and pleas from Salt Lake City Mayor Ezra Thompson, thejurors, and others, the board refused to commute Lynch's sentence. It now seemed certain that James Lynch would finally face a firing squad, since the board was not scheduled to meet again until after hisJanuary 8 execution date.

Undaunted by the board's decision, Wanless continued to press for a life sentence for Lynch. On December 3059 he presented Governor Wells with another petition, signed by fourteen distinguished citizens and prominent attorneys, including a future and a former United States senator: W. H. King and Arthur Brown.60 The petition focused on Lynch's role in preventing other prisoners from killing guard Jacobs

34 It is worth noting that among the speakers at Zina D H Young's funeral in 1901 was Emmeline B Wells, a plural wife of Daniel Wells, the father of Gov Heber M Wells Mrs Wells is quoted as saying, "I mourn for Sister Zina and I cannot help it No woman was ever greater loved than Sister Zina." DeseretNews, September 2, 1901

55Janet Peterson and LaRene Gaunt, ElectLadies (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), p 52

56 Salt Lake Herald, September 23, 1914

57 Deseret News, December 21, 1903.

58 Salt Lake Tribune, December 20, 1903

59 Salt Lake Herald, December 31, 1903, and Deseret News, December 31, 1903.

60 The petition was signed by M P Henderson, A B Irvine, Ashby Snow, M M Kaighn, William A Lee, P C Evans, Fred T McGurrin, Arthur Brown, W H King, A R Barnes, L R Rogers, H.J Dinainy, M P Braffet, and A A Duncan

The Case of Lynch and King 121

ZinaD. H. Young USHS collections.

during the prison break: "When offered an opportunity to escape, Lynch paused long enough in the flight to render material assistance in saving the life of one of the officers at the prison." Continuing, the petitioners reasoned:

Lynch must have known that delay endangered his chance of escape. We must regard this act, therefore, as both courageous and humane If the principle of 'a life for a life' be urged, we answer that justice may well be satisfied with a life spared for a life saved. As Lynch saved innocent life, we urge that his own life be spared

The petition worked. Soon after receiving it Governor Wells called a special meeting of the Board of Pardons for Saturday,January 2, 1904, to reconsider Lynch's application Wells also instructed Lynch himself to appear before the board—the first time in state history that a condemned man was given the opportunity of appearing personally before the board to plead for mercy This unusual circumstance, requiring the board members to actually face the person who would live or die by their decision, could only have placed added pressure on the members to grant his plea for mercy.

Meeting in the chapel of the state prison,61 the board listened to prisoners who told how Lynch had convinced them to spare guard Jacobs. One of the prisoners quoted Lynch as insisting that no blood be shed or "you boys can count me out."

Questioned about the escape, Lynch said he didn't know anything about it until his cell door opened. He took full advantage of it, however, because "he saw nothing but death staring him in the face" if he remained Lynch went on to point out that during his week of freedom he had not attacked or injured anyone.

At 1:15 p.m the board unanimously voted to commute Lynch's sentence to life imprisonment. In their written decision, signed by Governor Wells and Secretary of State M. A. Breeden, they said commutation was granted for the reason "That he saved the life of Guard Jacobs in the recent attempted jail delivery at the state Penitentiary, and the petitions numerously signed by citizens of Salt Lake City."62

YVben told of the board's decision, Lynch was "so overcome by his feelings that he could make no reply. . . .Then he sat down on his cot in the death cell and wept."63

122 Utah Historical Quarterly

61 Salt Lake Herald, January 3, 1904, and Salt Lake 7^ribune, January 3, 1904 62 Board of Pardons Minutes, Series 332, Box 1,January 2, 1904, Utah State Archives. 63 Salt Lake Herald, January 3, 1904

When the Board of Pardons met that Saturday in January they weighed the life spared by Lynch—Zebulon Jacobs—against the life he had taken—George Prowse. Prowse was the owner of a gambling house who left no survivors or relatives in Utah. While a number of prominent men petitioned the board to spare Lynch's life because he had saved Zebulon Jacobs, not one friend, relative, or acquaintance of Prowse asked the board to impose the death penalty as retribution for the life he had taken. As the board members weighed mercy with justice, they concluded that extending mercy to Lynch was the right thing to do. Lynch had not won freedom as had King, but, thanks to his actions during the prison break, he escaped what had seemed to be the certain fate of death by firing squad.

For the next twelve years James Lynch remained incarcerated in the Utah State Prison His reputation as a "model prisoner"64 was enhanced. He won the confidence of prison officers and served for a number of years as a "trusty" in the prison office.65 On December 18, 1915, he applied to the Board of Pardons for parole.66 A month later, on January 22, 1916, the board considered Lynch's application along with six others. His was the only one of the seven granted.67

On the afternoon of Monday, January 24, 1916, less than sixteen years after the hold-up at the Sheep Ranch gambling house, Warden Arthur Pratt approached Lynch, who was standing in the prison yard, and told him he was free to leave the prison Lynch stood as if frozen for a moment, and "Then emotion took hold and he rejoiced like a child." After saying goodbye to former cellmates and guards, Lynch left prison and accepted a job in the copper mill at Garfield, west of Salt Lake City.68 Thus ended one of the most complicated and peculiar murder cases during the early years of Utah's history

64 Salt Lake Herald, March 19, 1911.

65 Salt Lake Telegram, January 23, 1916, and Salt Lake 7ribune, January 23, 1916.

66 Lynch initially applied for commutation of his sentence on February 18, 1911, and it was considered on March 18, 1911 For some unknown reason, after it was considered by the board in executive session, Lynch withdrew the application "without prejudice." (See Board of Pardons Minutes, Utah State Archives Series 332, Box 2, pp 143, 146.) Newspaper reports indicated that Lynch intended to ask for parole at a later time (Deseret News, March 20, 1911)

67 Board of Pardons Minutes, Series 332, Box 3, December 18, 1915, and January 22, 1916, pp 134, 143

The Case of Lynch and King 123

Justice in the Black Hawk War: The Trial of Thomas Jose

BY ALBERT WINKLER

BY ALBERT WINKLER

I N AUGUST 1867 THOMAS JOSE, A WHITE MAN, was tried and convicted of the murder of Simeon, an Indian. The case wasunusual because the settlers of Utah seldom faced legal action for misconduct victimizing Native Americans during the Black Hawk War.

The legal system in Utah was administered by the whites to deal with conduct among themselves and to protect their interests Indians were largely excluded from that system and were given inadequate protection especially in times of conflict such as the Black Hawk War of 1865-68 when even peaceful Native Americans were viewed with suspi-

t Beaver & O^ Paragonah Parowan ly on UTAH * \>* ^ V Cedar City Portions of Beaver and Iron Counties ® Approximate Site of Murder

Dr Winkler is an archivist in the Harold B Lee Library at Brigham Young University

cion The stress of war led some whites to excesses because they did not need to worry about legal restraints. Incidents of the mistreatment of women, children, and other hapless Indians during the hostilities were often inadequately investigated, lightly punished, or simply ignored

During the Black Hawk War a number of instances of the killing of Indians by whites occurred under questionable circumstances On July 18, 1865, a "dozen or more" Native Americans, including women and children, were killed near Burrville by a militia unit that fired blindly into a large cedar grove That same month several Indian women and children captives were killed when a woman struck one of the guards with a stick. The militiamen shot the woman and the rest of the prisoners. 1 Neither of these incidents was officially investigated

Individuals with legal authority could also be accused of excesses.

On March 14, 1866, the Ute chief Sanpitch and seven or eight other men were arrested near Nephi after they had been implicated by rumor. Sanpitch was ordered to dispatch men to bring in Black Hawk and his band or be shot. The chief had insufficient power to bring in the warring Utes, so he and his fellow prisoners broke jail rather than await execution. Each was hunted down and killed.2 The largest massacre of Indians occurred at Circleville in April 1866 when at least sixteen unarmed Paiute Indians, including women and children, were killed— m ost had their throats slit. Despite pleas for an investigation, federal and territorial officials took no legal action.3

Another incident demonstrates that even the most blatant murder could go unpunished. On June 10, 1866, Ute warriors attacked Round Valley (Scipio), taking stock and killing James R. Ivie and Henry Jennings Militia units pursued the raiders but failed to prevent their escape Unable to avenge the death of his father on the raiding party, James A. Ivie killed an "old Indian," Pannikay (Panacara or Parmikang). The victim belonged to the Round Valley "tribe or family" of Pahvant Indians who were considered peaceful, but the fact they were Native Americans was enough to raise suspicions. Shortly after the Ute attack, Pannikay had come to Benjamin Johnson of Round Valley where Thomas Callister was visiting. Johnson told

1 Peter Gottfredson, Indian Depredations in Utah (Salt Lake City, 1919), pp 159-61

2 Ibid., pp 187-89; Carlton Culmsee, Utah's Black Hawk War: Loreand Reminiscences of Participants (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1973), pp. 80-88.

3 Albert Winkler, "The Circleville Massacre: A Brutal Incident in Utah's Black Hawk War," Utah Historical Quarterly 55 (1987): 4-21 This article also presents a summary of some other unpunished misdeeds in the war.

The Trial ofThomasJose 125

Pannikay the whites were very angry and doubted his safety there, and Callister advised him to go to the camp of Kanosh, a Pahvant chief Pannikay, probably in fear of his life, ran away.Johnson intercepted him on horseback and took his gun. He was leading the unarmed Indian back when James A Ivie rode up and shot him Callister and others saw the Indian fall, and they approached to see the victim covered with blood. Ivie admitted killing the man, saying he was avenging his father's death. Callister told Ivie that the "poor Indian" had nothing to do with his father's demise and that "he had better go into the field where the hostile Indians were" if he wanted to kill the perpetrators of the act. Hoping to avert trouble, Callister told the leaders of the Pahvants what had happened Kanosh simply recommended that Ivie give Pannikay's son a horse and some money in compensation. 4 So, although Ivie murdered an unarmed man in front of witnesses and admitted the deed, apparently his only punishment for the crime was a verbal reproof from Callister and a suggestion of a payment by Kanosh.5

From the outset of hostilities in 1865 LDS church leaders had spoken against harming innocent Indians. Onjuly 19 of that yearJohn Taylor made the following statement at Mount Pleasant: "Some want to kill the Indians promiscuously, because some of them have killed some of our people This is not right Let the guilty be punished and innocent go free."6

Brigham Young was more detailed in his opinion as expressed at Springville on July 28, 1866. He stated that Indian hostilities were brought about by "our brethren" who had not treated the Native Americans as they should. He had "a harsh word" for anyone "who professes to be a Latter-day Saint who has been guilty of killing an innocent Indian." Such a person "isjust as much a murderer through killing that Indian, as he would have been had he shot down a white man." Young stated what should be done with anyone who murdered a Native American: "Take that man and try him by law and let him receive the penalty. The law will slay him."7 Despite such sentiment the legal system did little to punish crimes against Indians until Thomas Jose was accused of killing Simeon a year later.

4 Thomas Callister to George A Smith, June 17, 1866,Journal History of the LDS Church, LDS Church Library-Archives, Salt Lake City See also William Probert to Peter Gottfredson, July 1, 1915, cited in Gottfredson, Indian Depredations, pp. 228-29.

5 Whether Ivie actually gave the horse and money to the boy is not known

6Deseret News,July 19, 1865

7Brigham Young, "Remarks,"July 28, 1866,Journal History

126 Utah Historical Quarterly

On Saturday, July 6, 1867, Simeon, a Paiute Indian of a group residing near Beaver, was seen "on the range" where the cattle were kept near Paragonah (Red Creek) He was detained by the militiamen who guarded the stock, but he had a pass from Isaac Riddle of Beaver and was allowed to continue The local Paiutes were believed to be peaceful and to have little sympathy for the warring Utes because of animosities between the two groups. ButJoseph Fish of the militia protested to Silas S Smith, who was over the guards, "against allowing Indians to pass near our stock, as they might be acting as spies."8 A few days later Simeon was again in the area and got a ride in the wagon of George Condie. The man had some fish with him and said he had been to Fish Lake. He said he was on his way back to Beaver.9

Probably on July 8 Simeon camped about two miles north of Paragonah near "Little Creek." Onjuly 17 his body, with a bullet wound in the back of the head, was found by a sheepherder. This "created much excitement both among the friendly Indians and some of our brethren." 1 0

The discovery of Simeon's body was soon followed by an Indian raid. During the night ofJuly 21 raiders struck near Paragonah. Several times they attempted to seize cattle and escape up Cottonwood Canyon Each time they were thwarted by the whites, and sporadic fighting lasted until the afternoon ofJuly 22. The affair was a complete success for the militia which repulsed the Indians, regained the stolen cattle, and captured about fifty of the raiders' saddle horses without losing a man. 11

9

10 Fish Diaries,July 9, 1867

1 Tbid.,July21,22, 1867.

The Trial ofThomas Jose 127

Silas S. Smith. USHS collections.

8Joseph Fish, Diaries,July 6, 1867, typescript, Special Collections, Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Thisjournal is in part at least retrospective because Fish entered under certain dates information that he could only have acquired later

George Condie as cited in Utah v Thomas Jose, Iron County Legal Records, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City

Soon after Simeon's body was found, William H Dame, president of the Parowan Stake of the LDS church and colonel of the militia, had received strong advice from Brigham Young and George A. Smith on what to do with murderers of Indians The telegram, dated July 20 at 3:30 p.m., clearly stated that anyone guilty of "the murder of a friendly Indian . . .should be taken by the civil authorities; and punished, as any other murderer: as an act of this kind exposes the lives of many innocent and defenceless persons."12

The fear of Young and Smith that the unpunished crime of murder might lead to further atrocities wasjustified Joseph Fish reported on August 4 that "the Indian excitement has not abated very much" and that "some of our boys took some of our friendly Indians and were going to hang them, claiming that they were connected with the hostilities during the last raid."13 These men were dissuaded from the attempt, but the fear of such rash reprisals remained. The murder of Simeon was examined perhaps as much to serve as a deterrent as for the cause ofjustice.

Samuel H Rogers and Silas S Smith conducted the investigation Rogers interviewed a number of people in Paragonah. Some settlers were reluctant to cooperate, and Rogers finally "threatened" Monroe Lowder to get information from him When a few people questioned whether Simeon had actually been murdered, since the body was buried without an inquest, Rogers exhumed the body onjuly 23.He cut the head off the corpse, found the entry wound of the bullet, and reburied it. On August 5 he returned to the grave with a physician, Calvin C. Pendleton. This time they "brought away" the head, "opened" the skull, and removed the bullet As a result of that investigation Rogers brought charges against Thomas Jose.14

A grand jury was impaneled on August 22 to decide if the evidence was sufficient to bringJose to trial.Joseph Fish, a member of the grand jury, recorded that "it was with difficulty that the indictment was found, as some thought it of little consequence in these times of Indian troubles to kill one [i.e., an Indian], whether friendly or not."15

Erastus Snow addressed such issues in a speech that day and in two

13

15 Fish Diaries, August 22, 1867

128 UtahHistorical Quarterly

12 Brigham Young and George A Smith to William H Dame, July 20, 1867, Special Collections, Lee Library, BYU

Fish Diaries, August 4, 1867

14 Samuel Rogers outlined the investigation at the trial of ThomasJose; see Utah v Thomas Jose

sermons on the day following Traveling north from St. George, Snow apparently stopped at a number of towns to speak to the people.16 Fish summed up Snow's remarks: "His preaching was principally about relations with the Indians. He showed how we as a general thing condemn all the Indians for the hostile acts of a few. This was not right orjust. The Jose case called for some measure to be taken, or the Indians, whether friendly or not, would be shot down like wolves on the prairie."17

Jesse N. Smith, judge of the Iron County probate court, presided at Jose's trial. Smith was a prominent citizen but had little if any formal training in law.18 The jury for the case of "The People of the Territory of Utah versus Thomas Jose indicted for the murder of one Simeon a friendly Indian" consisted of men called from Cedar City, with John M. Higbee serving as foreman. Testimony in the trial was heard for two days starting on Monday, August 26.19

The trial began with Samuel H. Rogers, the prosecuting attorney, calling witnesses. William Lefevre testified that on July 8 he had met the defendant who was looking for mules Jose had been searching for two or three days and thought Indians had taken them. He said "he would be damned if he did not kill the first Indian he came across." That same dayJoseph Fish also heard the defendant say that if he learned Indians had taken the mules he would kill the first one he met if he "swung for

"Fish Diaries, August 23,

18

The Trial ofThomas Jose 129

Erastus Snow. USHS collections.

16 Andrew Karl Larson, Erastus Snow: The Life of a Missionary and Pioneer for the Early Mormon Church (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1971), pp 406-7 Snow was a Mormon apostle and brigadier general in the militia, meaning he had substantial influence in the area He had been invited by Brigham Young to accompany him on a tour of the settlements in northern Utah

1867

Smith served as a territorial legislator from Iron County, mayor of Parowan, colonel in the militia, and a counselor in the Parowan Stake presidency SeeJesse Nathaniel Smith, "Brief Autobiography," in AndrewJenson, ed Latter-DaySaint BiographicalEncyclopedia, 4 vols (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Co., 1901-36), 1:316-23

19 The main source on the trial is Utah v Thomas Jose These notes were probably taken by a court reporter Some information was recorded verbatim, while the rest was summarized

it the next minute." F Whitney reported that Jose had made a similar threat on or aboutJuly 12 when he had come to Whitney's store. When asked what he intended to do with the pistol he carried, Jose had said, "I am going to kill the first Indian I come across by h -1."

Alan Miller testified that he and Thomas Butler had talked with "an old Indian" near "Little Creek field" at sunset onjuly 8 Miller said they saw someone who looked like the defendant about one-half mile from the road. The man had no weapons that Miller could see. Later that evening Miller went to see Thomas Jose to go with him to play games with William Robb. Later, when Isaac Riddle came looking for Simeon, Miller asked the defendant if he had killed the Indian. Jose said he had not

Emily Lowder testified that she sawJose leave his house with a gun right after her children reported seeing an old Indian pass by. Her nephew, Monroe Lowder, came home about midnight that evening from playing at Robb's He said the defendant had told him he had followed the Indian to Little Creek and had observed him take a drink there and go into the brush to make camp. Monroe commented that he did not think the Indian would bother anyone again because he thought Jose had killed him. But when Emily pressed Monroe to say directly that the defendant had murdered the Indian, he replied no. Emily later approached Jose's mother, Ann, who said Thomas had left with a gun that evening. It was loaded when he left, but it had been fired when he returned. Emily also reported, "Mrs.Jose said to me if it was told what she told me her life would not be worth that" and snapped her fingers.

Monroe Lowder testified that Allan Miller and ThomasJose had arrived between 8 and 9 p.m to play games Rogers asked Lowder if he had questioned Jose about killing Simeon, but Lowder did not remember. When asked again if he had queried Jose about the death of the man, Lowder said yes But Lowder deflected this line of questioning by referring to the defendant's earlier statement that he would kill an Indian to pay for the theft of his mules.

John D. Pickering had found the dead Indian. He had made no detailed examination of the corpse but said the victim was in a sleeping position, lying on his right side with his left arm across his body and his right arm above his head The body was buried shortly after Pickering's discovery.

Most of the physical evidence in the case was presented by the physician, Calvin C Pendleton, who had participated in the coroner's

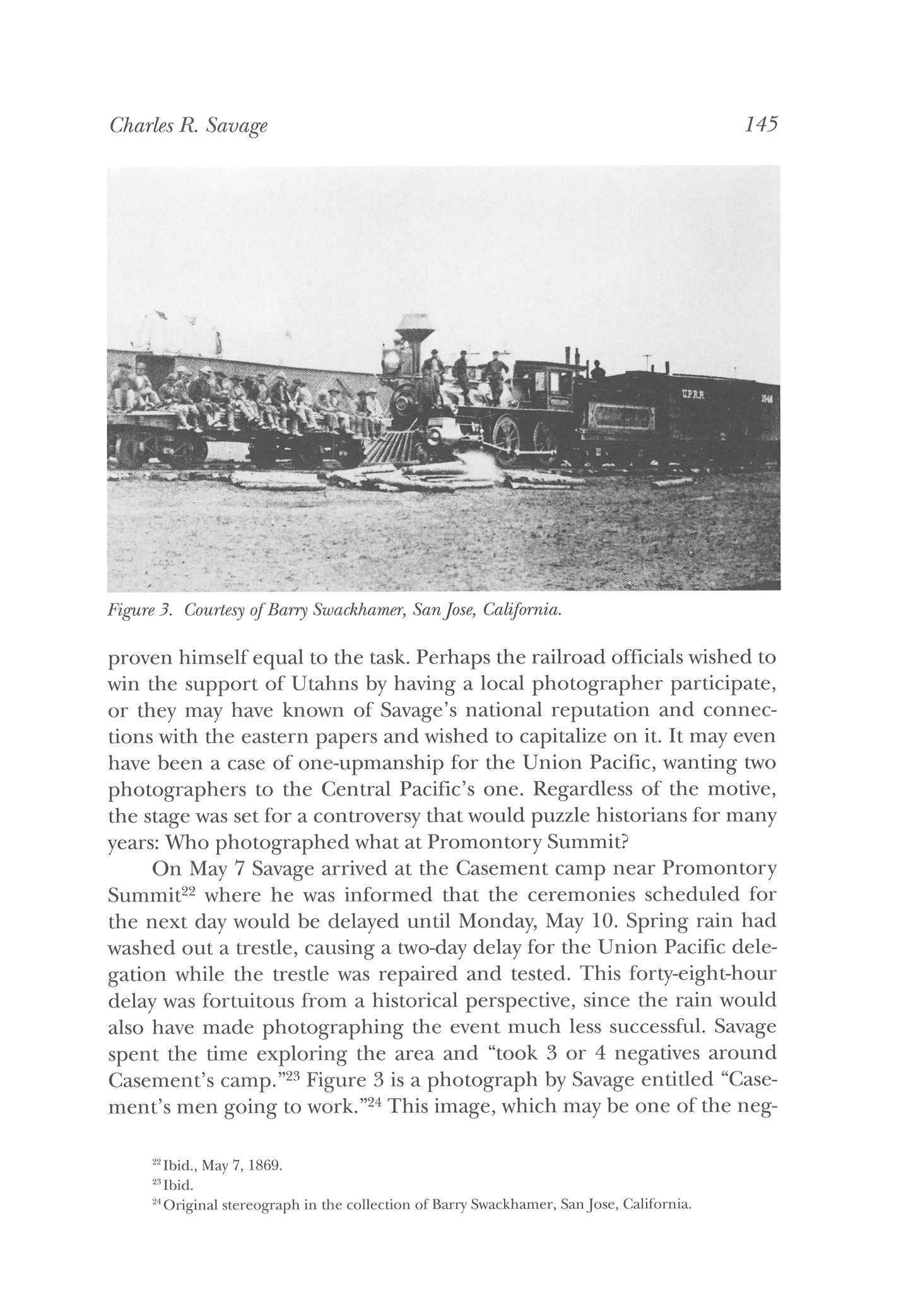

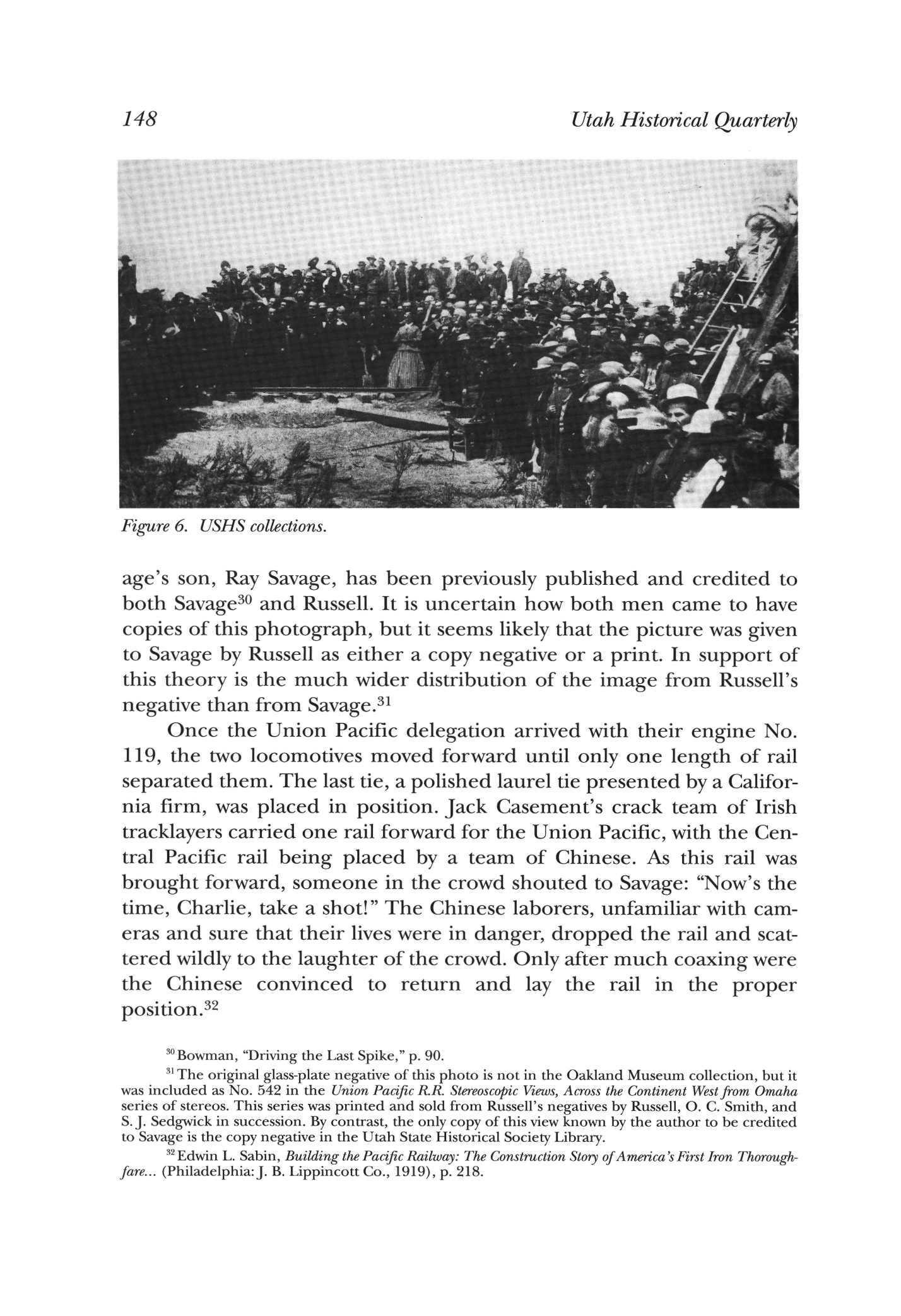

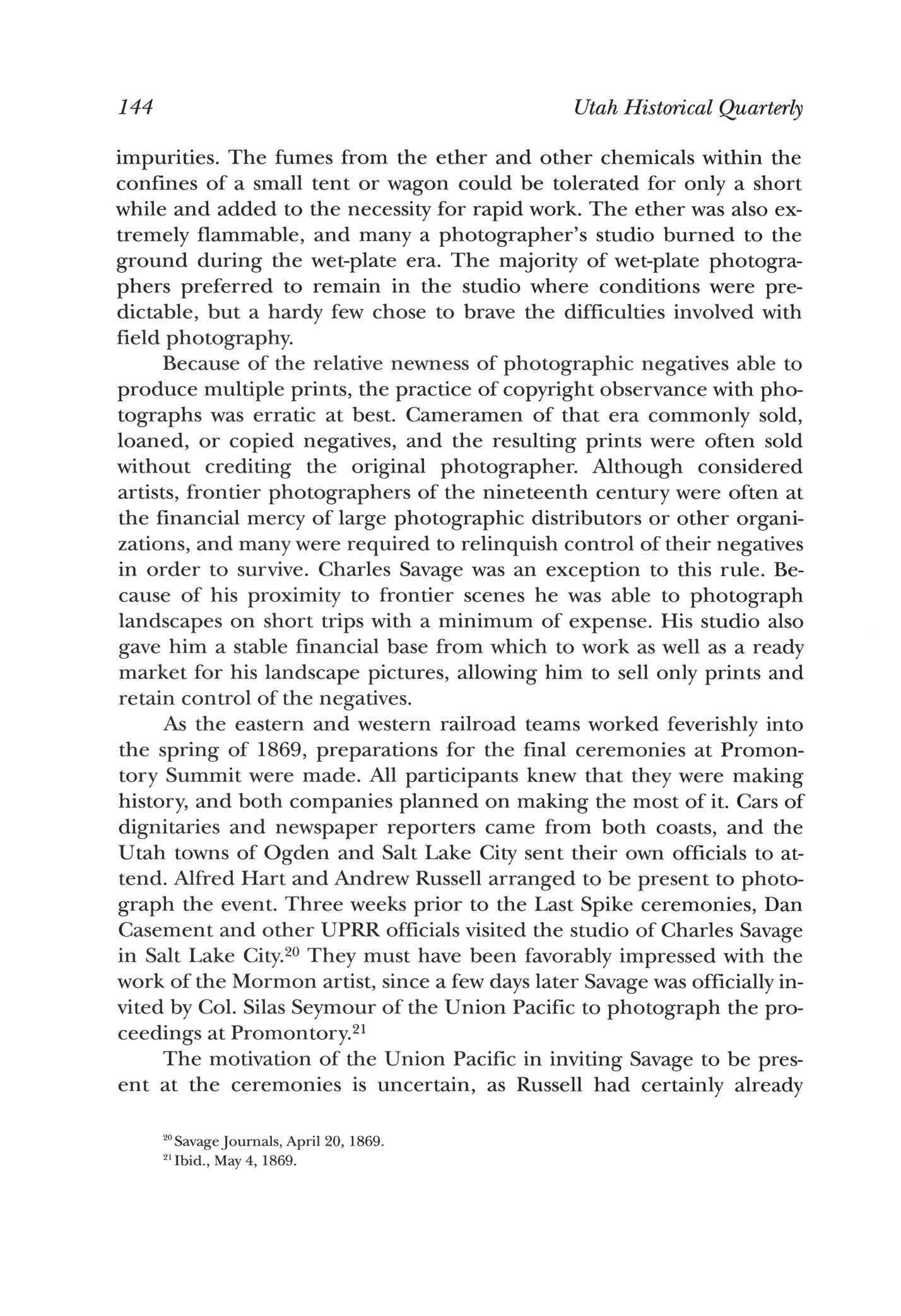

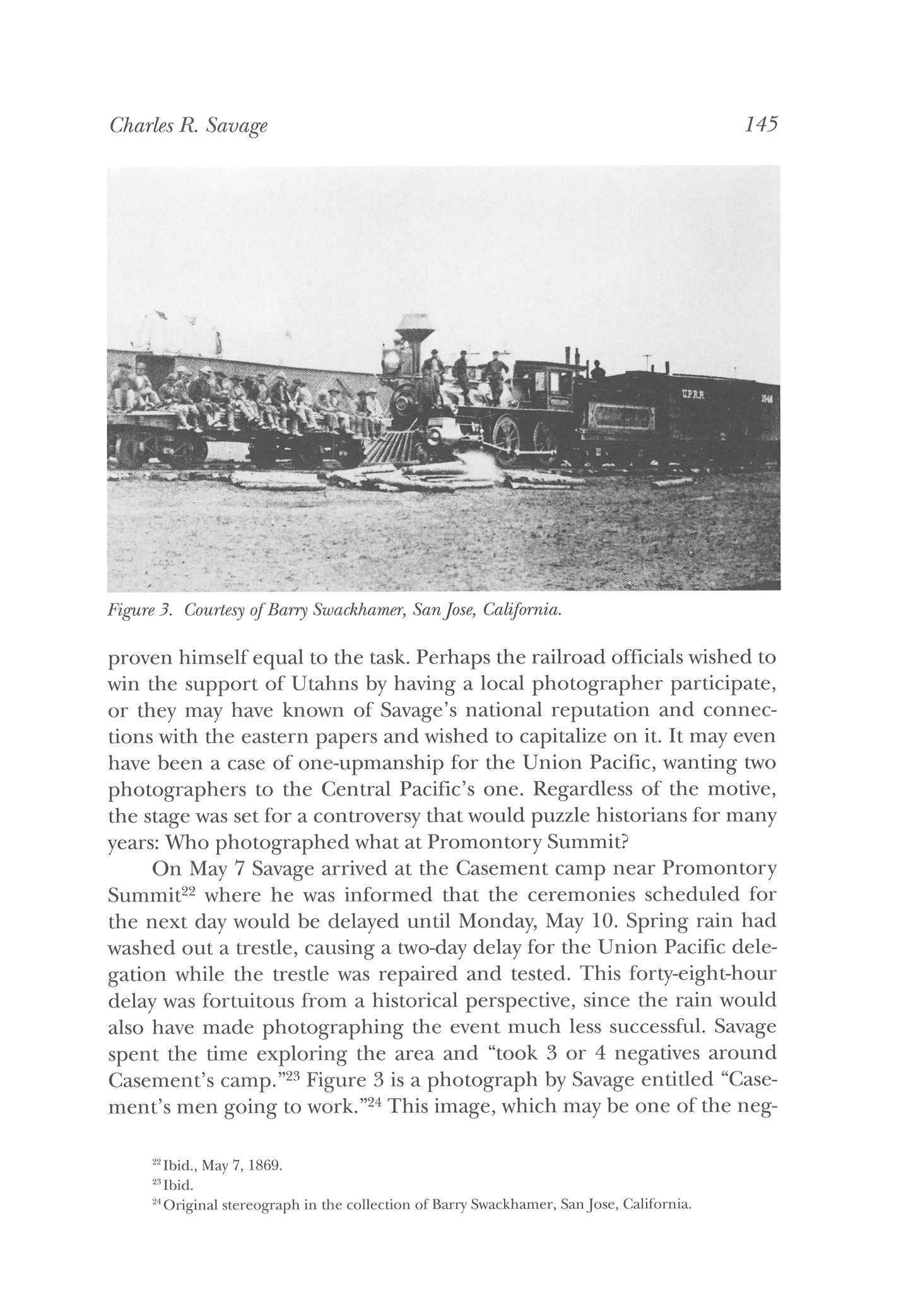

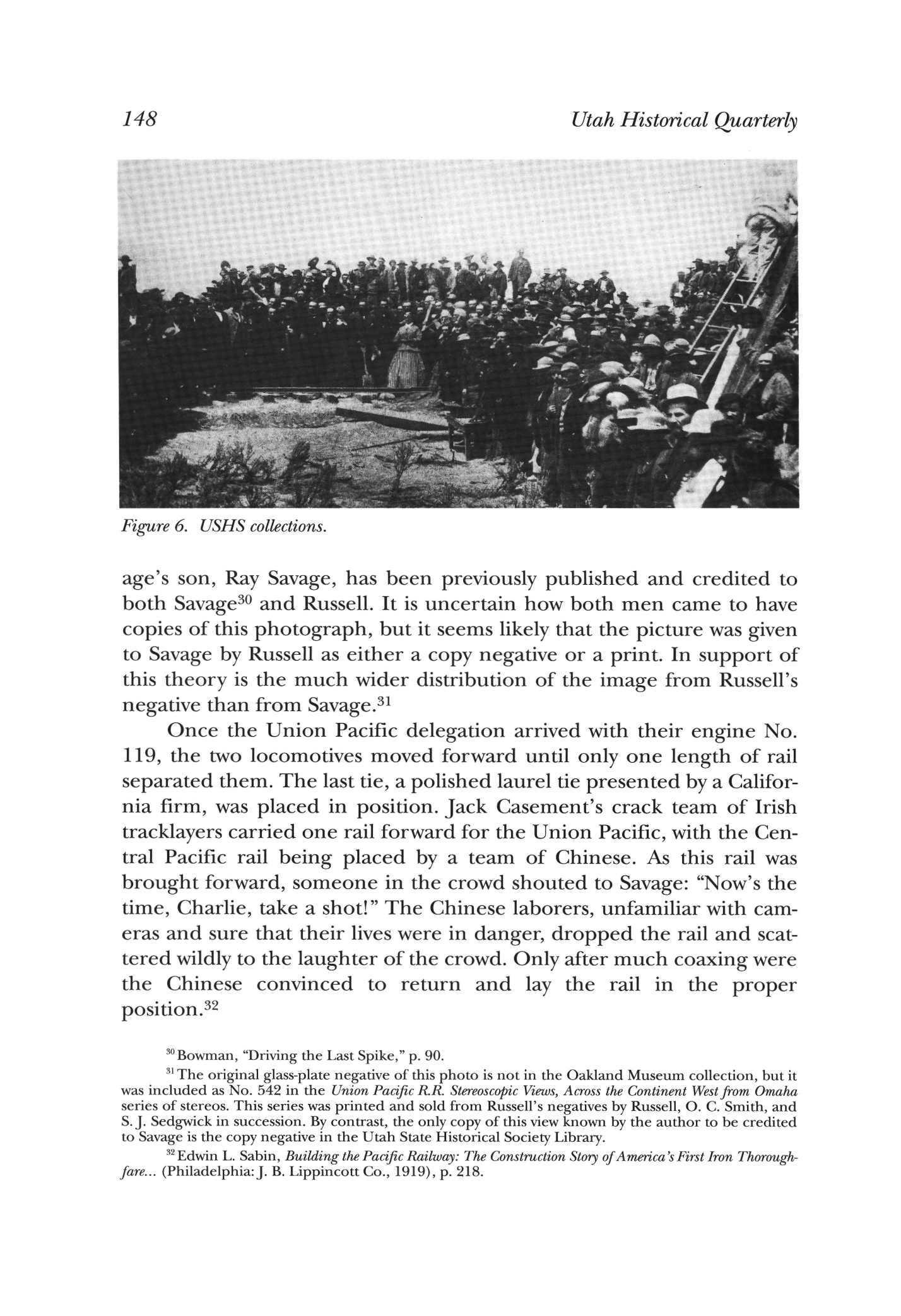

130 Utah Historical Quarterly