CO CO < O as

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City,1997

JANICE P DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C. JANETSKI, Provo,1997

ROBERT S. MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

GENE A SESSIONS, Ogden,1998

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

Richard S. Van Wagoner, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801)533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 514 or 3V4 inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor. Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (chang e of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICA L tlUARTERLr Contents WINTER 1996 \ VOLUME 64 \ NUMBER 1 IN THIS ISSUE 3 UTAH'S SILVER QUEEN AND THE "ERA OF THE GREAT SPLURGE" JUDYDYKMAN 4 HOSPITALITY AND GULLIBILITY: A MAGICIAN'S VIEW OF UTAH'S MORMONS DAVID L. ZOLMAN, SR. 34 THE DENIS JULIEN INSCRIPTIONS JAMES H. KNIPMEYER 52 UTAH'S CHINATOWNS: THE DEVELOPMENT AND DECLINE OF EXTINCT ETHNIC ENCLAVES DANIEL LIESTMAN 70 BOOK REVIEWS 96 BOOK NOTICES 104 THE COVER Susanna Emery Holmes, Utah's Silver Queen, was known for her wealth, fashion, and flair. Photograph is from the Gardo House album in USHS collections. © Copyright 1996 Utah State Historical Society

WILLIAM WYCKOFF and LARY M DILSAVER, eels The Mountainous West: Explorations in Historical Geography LOWELL C. "BEN" BENNION

96

PHILIP J MELLINGER Race and Labor in Western Copper: The Fight for Equality, 1896-1918 . PHILIP F. NOTARIANNI 97

PAUL W HIRT A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests since World War Two . BRIAN Q. CANNON 99

MARILYN IRVIN HOLT Linoleum, Better Babies, and the Modern Farm Woman, 1890-1930 Jo ANN RUCKMAN 100

PAUL SCHULLERY. Yellowstone's Ski Pioneers: Peril and Heroism on the Winter Trail ALEXIS KELNER 101

ZEESE PAPANIKOLAS Trickster in the Land ofDreams RUSSELL BURROWS 103

Books reviewed

Oakwood, the Silver Queen's summer home in Holladay. Her brother and sister, John and Nellie Bransford, are sitting on the porch. Courtesy ofHarold Lamb.

In this issue

Few personalities in Utah history have held more fascination for historians, have created a greater body of lore, or have eluded a biography longer than Susanna Bransford Emery Holmes Known familiarly as the Silver Queen, she was a classic rags-to-riches persona during a time when that theme dominated U.S. popular literature. Flamboyant, mercurial, and strong-willed, she rode her Park City wealth to entree into the upper crust of Utah, California, New York, and European society, leaving behind a confusing welter of legends, rumors, and suppositions that has never ceased to scintillate the popular imagination. The first selection, based on an exhaustive search of probate and other original sources, tells her amazing story and places her within a larger historiographical context than she has ever known before

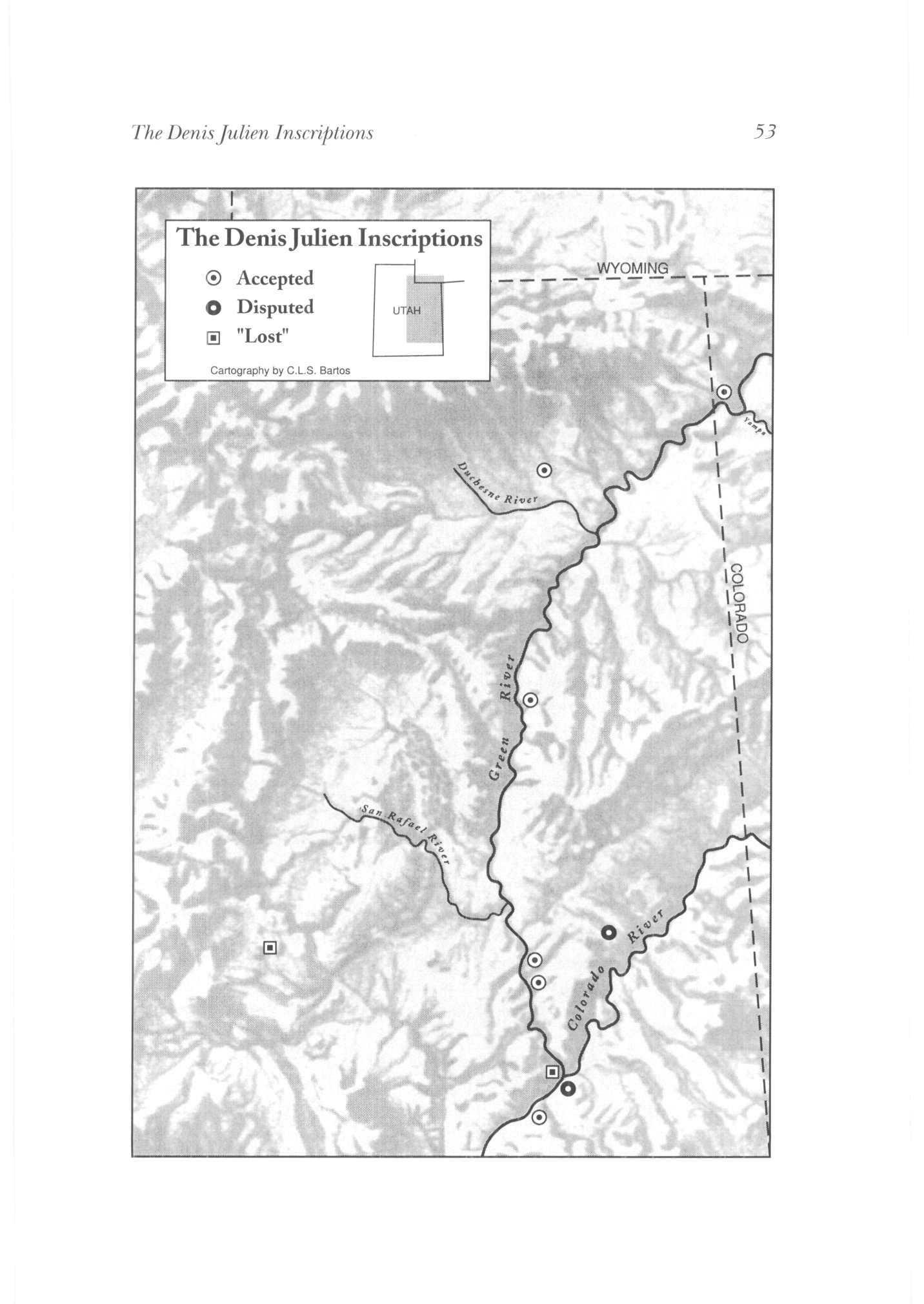

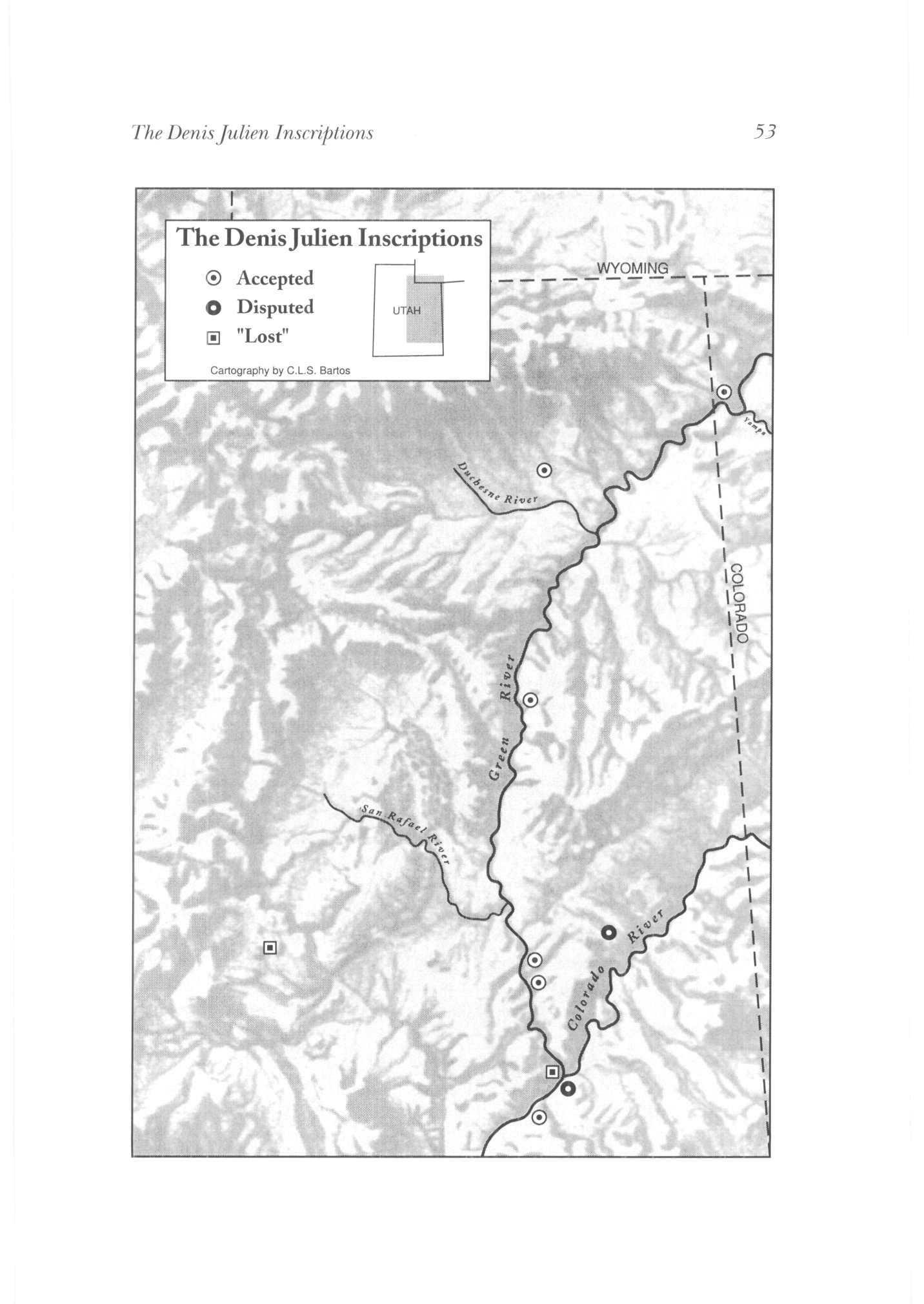

The next two articles also deal with personalities, though of a much different sort Denis Julien was a solitary and enigmatic figure—a mountain man who explored the length and breadth of Utah's pre-territorial landscape. Typical of his type, he left virtually no written record of his comings and goings Yet, his fewjottings—autographs on rock—have teased travelers and historians ever since In contrast, George Anton Zamloch drummed his way through Utah with great fanfare, seeking to mystify people in a different way—with feats of magic. His personal reminiscence, penned years later and just recently discovered, is almost as astonishing as his sleight of hand must have seemed The excerpts featured here promise to delight and entertain just as much as his stage show did more than a century ago.

The final piece illuminates the history of one of Utah's oldest ethnic groups, the Chinese. Creating their distinctive enclaves within a half-dozen counties, these energetic immigrants nurtured hopes and pursued dreams within a frequently hostile social environment Though Utah's Chinatowns have long since disappeared, their colorful legacies remain to enrich and enliven our cultural heritage.

Utah's Silver Queen and the "Era of the Great Splurge"

BYJUDYDYKMAN

This photo of the Silver Queen reveals her beauty. USHS collections.

Mrs. Dykman is a history teacher at Churchill Junior High School in Salt Lake City.

BYJUDYDYKMAN

This photo of the Silver Queen reveals her beauty. USHS collections.

Mrs. Dykman is a history teacher at Churchill Junior High School in Salt Lake City.

HE R ROYAL HIGHNESS SUSANNA Egera Bransford Emery Holmes

Delitch Engalitcheff was one of America's most colorful and unconventional millionaires, and her lifestyle frequently mirrored the excesses of an era As a child shejourneyed to California in a covered wagon; as a teenager she survived a stagecoach holdup; and as an adult, she traveled around the world four times and lived in a palace Married four times, she outlived all of her husbands even though two of the men were many years younger She met kings, queens, presidents and statesmen, conferred with a pope and conversed with Hitler and Mussolini. Affectionately known as Susie to her family and friends and as Utah's Silver Queen to the press, she was loved by some and vilified by others. For decades her social activities, travels, and personal tragedies made headlines. At the turn of the century some speculated that her shares in Park City's fabulous Silver King Mine made her one of the wealthiest women in Utah, if not the United States. Because of this extensive press coverage many have mistakenly assumed that her life resembled an updated version of the Cinderella fairy tale. Recently, two authors have even compared her to Princess Diana or Elizabeth Taylor, while others have accused her of being cold hearted or indifferent to the needs of her daughter, unkind to her husbands, and foolish with her money. Extensive research shows that many stories about her are exaggerations or misrepresentations In reality she was typical of the cosmopolites of the "Gilded Age" who had different values and perceptions than the average American Who then was Susie and which stories about her life and adventures are true and which are merely entertaining folklore?1

The second of four surviving children in the Milford and Sara Ellen Bransford family, Susie was born May 6, 1859, in Richmond, Missouri Prior to the Civil War her parents owned seventy acres of land, several slaves, and a general store When the war broke out her father served as a captain in the Confederate Army Following his release from a prison camp he returned to Missouri to check on his young family and found them impoverished Hoping for a fresh start, several Bransford families in the Richmond areajoined a wagon train

1 "Utah's Own Silver Queen Arrives for Summer Visit in Salt Lake City," Salt Lake Tribune, May 12, 1938, p 12; "Susanna Emery-Holmes," Biographical Record ofSalt Lake City and Vicinity (Chicago: National Historic Record Company, 1902), pp 211-12; Margaret Godfrey, "The Silver Queen," Salt Lake City, September-Octoher 1993, pp. 33-34; unidentified article in Susie's scrapbook archived in the Utah State Historical Society's Library, Salt Lake City.

5

Utah's Silver Queen

bound for the gold fields. Six months later they settled in a number of northern California mining communities such as Crescent Mill.2

Five-year-old Susie and her older brother, John, attended the town's small grammar school; later, their father enrolled them in San Francisco boarding schools. During one of her stagecoach trips to or from Taylorsville, where the family now lived, Susie was involved in a robbery. When the bandits recognized her among the passengers they assured her that they would not harm her, but sixteen-year-old Susie never forgot the ordeal. Possibly the bandits were neighbors of the Bransfords or lumbermen or miners as the men knew her name. 3

As she entered adulthood, Susie blossomed into a very attractive young woman with expressive eyes, flawless skin, a trim figure, and long brown hair. At five feet seven inches she was taller than many women of her day. Her fun-loving personality, self-confidence, and "gift of gab" enabled her to mingle easily with others. She attended many parties and social functions and was a charter member of a Taylorsville, California, girls club, Rescue Lodge #215, organized in 1877. As one admirer put it, she became "the belle of Plumas." The autograph book she kept prior to leaving California includes several romantic entries from numerous suitors and admirers, but she refused all of them.4

During the early 1880s Susie traveled extensively in northern California. It appears she traveled alone, moved to San Francisco and the Oakland area for five months, and then returned to Crescent Mill and Taylorsville where she had family. By the summer of 1884 she had arrived in Park City, Utah, to visit relatives or friends and find work Little information exists about this stage of her life, but an article in Plumas Memories reports she supported herself by working as a seamstress and hairdresser during her twenties. Interestingly, when a New York Herald journalist referred to her in 1902 as a former hatmaker

- Milford Bransford's Bible, courtesy of Dr Harold Lamb, Sr., Salt Lake City; John A Shiver, Bransford Family History (Kentucky: McDowell Publishing Company, 1981), p 35; see also Sara Cooper's undated will, probated in Lexington, Kentucky, copy in possession of Dr Lamb; "Crossing the Plains," a history of the Bransford trip to California, an unpublished account provided by Stella Enge (no author or date); "Milford Bransford," Park Record, May 25, 1894; "Milford Bransford Deceased," Plumas Independent (California), May 26, 1894.

3 "Utah's Own Silver Queen Arrives for Summer"; John Bransford Biographical Sketch, courtesy of Vadney Murray, Quincy, California; interviews with Susanna Hartman, Susie's niece, Laguna Hills, California; interviews with Jean Murray of Quincy, California All interviews cited herein were conducted by the author and are in her possession

4 Plumas County Historical Society, #26 (n.p ,n.d.), p 6; additional information found in unidentified news articles in Susie's scrapbook; Plumas Independent, May 26, 1894; magazine article from Elite in Susie's scrapbook; "from T.M.J.," an entry in Susie's autograph book, 1879-86, in the author's possession

6 Utah Historical Quarterly

and seamstress in one of Park City's stores, Susie fumed but saved the article in her scrapbook. By 1902 she desperately wanted to be accepted into eastern social circles; the article angered her because it claimed common laborers lacked the breeding to be society leaders.5

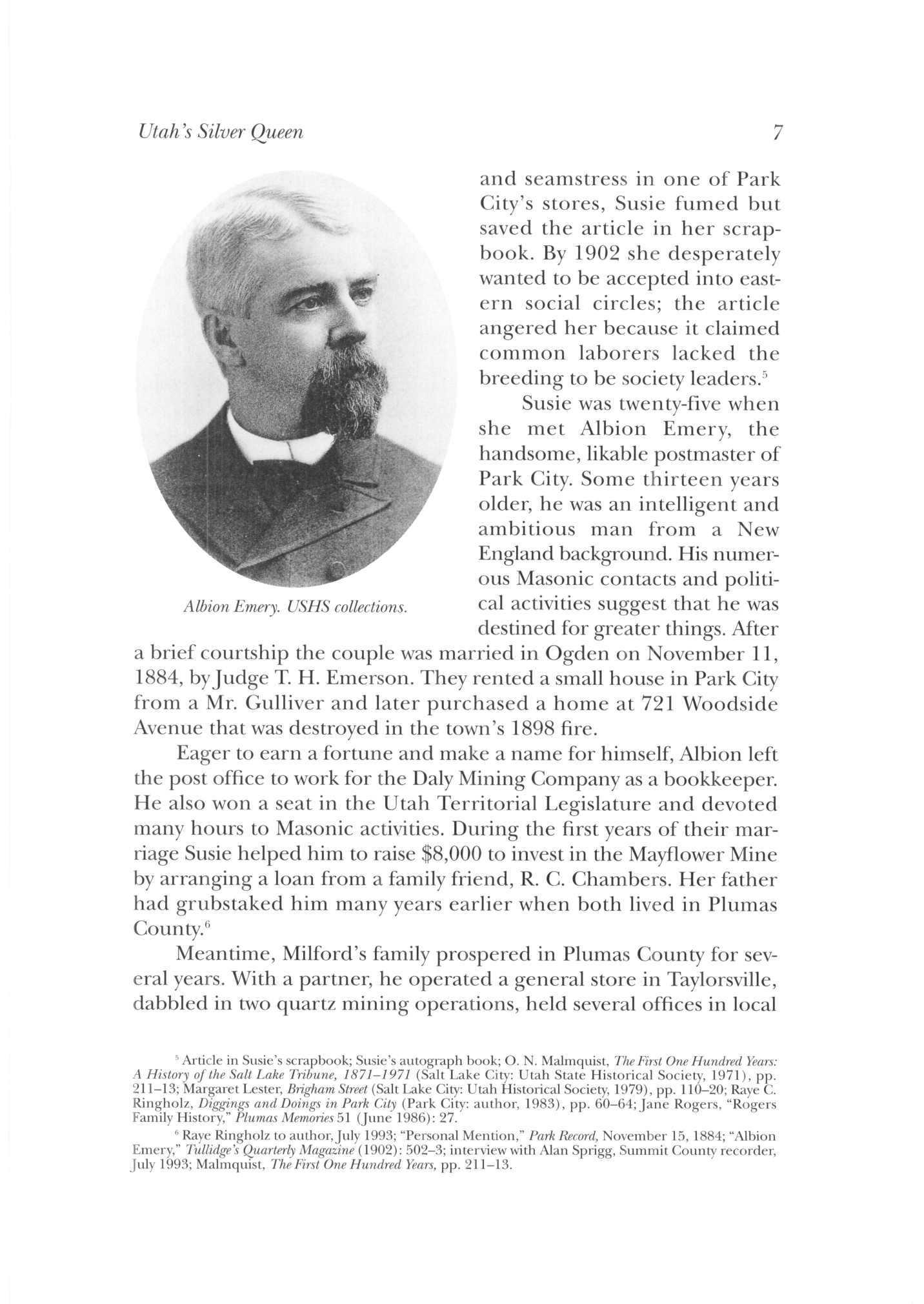

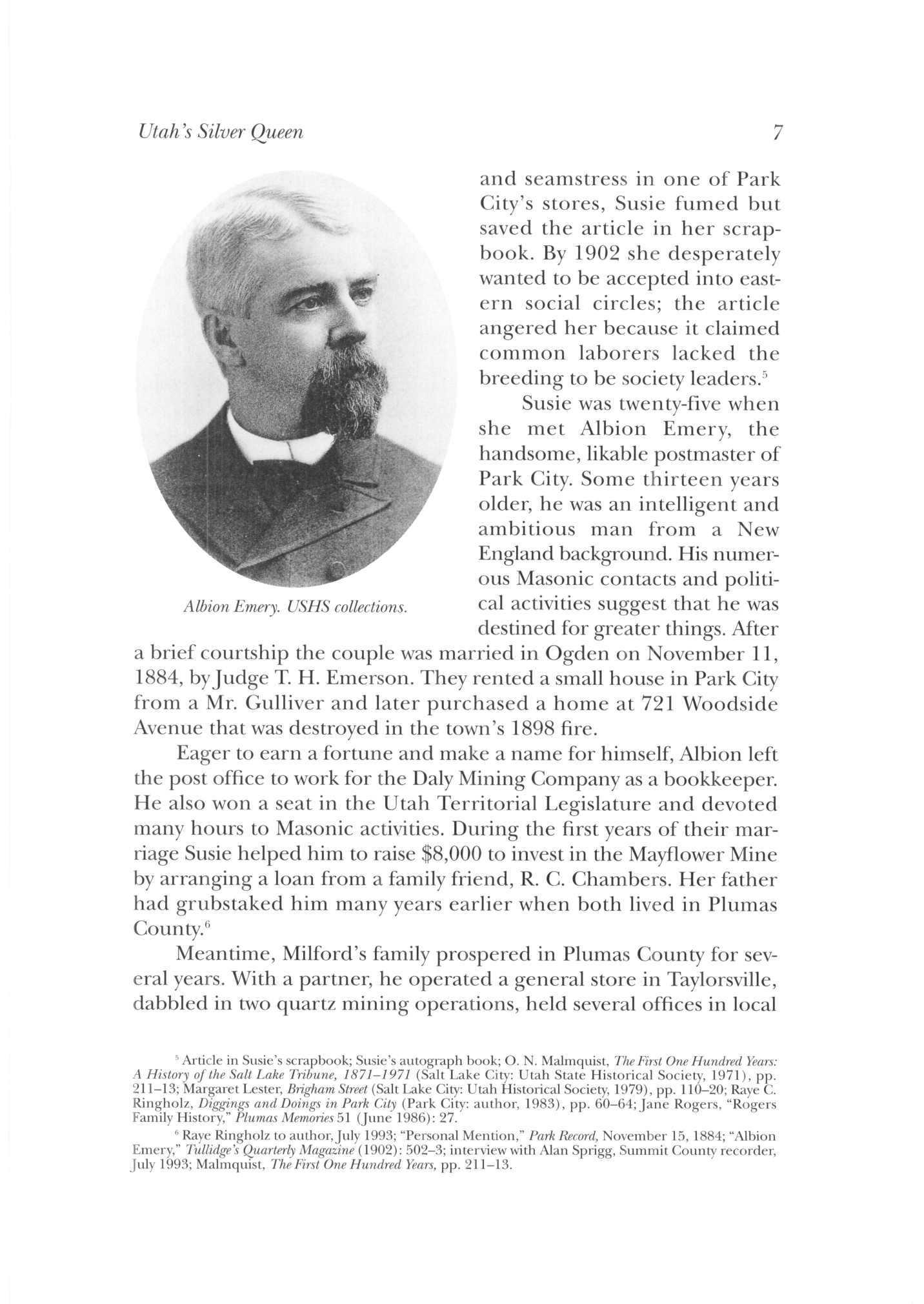

Susie was twenty-five when she met Albion Emery, the handsome, likable postmaster of Park City. Some thirteen years older, he was an intelligent and ambitious man from a New England background His numerous Masonic contacts and political activities suggest that he was destined for greater things. After a brief courtship the couple was married in Ogden on November 11, 1884, byJudge T. H. Emerson. They rented a small house in Park City from a Mr. Gulliver and later purchased a home at 721 Woodside Avenue that was destroyed in the town's 1898 fire.

Eager to earn a fortune and make a name for himself, Albion left the post office to work for the Daly Mining Company as a bookkeeper. He also won a seat in the Utah Territorial Legislature and devoted many hours to Masonic activities. During the first years of their marriage Susie helped him to raise $8,000 to invest in the Mayflower Mine by arranging a loan from a family friend, R. C. Chambers. Her father had grubstaked him many years earlier when both lived in Plumas County.11

Meantime, Milford's family prospered in Plumas County for several years With a partner, he operated a general store in Taylorsville, dabbled in two quartz mining operations, held several offices in local

5 Article in Susie's scrapbook; Susie's autograph book; O N Malmquist, The First One Hundred Years: A History of the Salt Lake Tribune, 1871-1971 (Salt Lake City: Uta h State Historical Society, 1971), pp 211-13; Margaret Lester, Brigham Street (Salt Lake City: Utah Historical Society, 1979), pp 110-20; Raye C Ringholz, Diggings and Doings in Park City (Park City: author, 1983), pp 60-64 ; Jan e Rogers, "Rogers Family History," Plumas Memories 51 (June 1986): 27

6 Raye Ringholz to author, July 1993; "Personal Mention," Park Record, November 15, 1884; "Albion Emery," Tullidge's Quarterly Magazine (1902): 502-3; interview with Alan Sprigg, Summit County recorder, July 1993; Malmquist, The First One Hundred Years, pp 211-13

Utah's Silver Queen 7

Albion Emery. USHS collections.

Utah Historical Quarterly

government, ran a stage line, and operated a boarding house. His many business ventures may have overextended his credit as he was sued for indebtedness in 1879 byj. D. Goodwin and in 1880 byj. McKinney As his properties and opportunities began to dwindle, stories of fabulous silver strikes in Utah's mountains attracted Milford and his family to Park City. In 1887 they migrated to Utah and he became the bookkeeper for the Ontario Mine and joined Park City's Masonic lodge.

Several myths surround Susie's children The Emerys were childless for three years until Susie's younger sister, Viola, died in 1887 To help her aged mother and brother-in-law, Willis Lamb, Susie volunteered to raise her sister's infant son, Harold Vernon Lamb. Two years later, in 1889, the Emerys adopted a two-year-old girl from a Boston orphanage One account suggested that Louise Grace was actually Albion's illegitimate child Another source speculated that the baby was the unwanted child of a Park City prostitute. No one knows Grace's parentage; a Boston policeman found her on a doorstep in May 1886, took her to a nearby orphanage, and gave her the name of Louise Radford, using his own surname While the Emerys were visiting one of Albion's sisters in the Boston area, the girl came to Susie's attention. Disappointed at not having a child of her own, Susie persuaded Albion to adopt the girl.7

In time the Emerys' fortune dramatically changed as the Mayflower Mine began to pay large dividends Albion and his new partners—David Keith, Thomas Kearns,John Judge, and W. V Rice— used the mine's early profits to purchase all of Park City's Treasure Hill. Then in 1892 Albion and his associates organized the Silver King Mining Company. 8 Newly rich, Susie and Albion radically changed their lifestyle, purchasing fine clothes and other luxuries and traveling extensively. Like other Parkites, they also purchased a large home in a prestigious Salt Lake City neighborhood: 352 East 100 South, a block south of the Cathedral of the Madeleine. Albion's prestige grew, andjust before his death in 1894 he was elected Speaker of the House in Utah's Territorial Legislature and became the Worshipful Grand

8

7 Interview with Dr Harold Lamb, Sr.; Wallace Bransford affidavit, p 2, Probate Hearing for Louise Grace Emery Bransford, #9027, 3d Circuit Court, 3d Judicial District, September 17, 1918, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City; interview with Floralie Millsaps, Salt Lake City, longtime tour guide for the Utah Heritage Foundation; Park Record, May 25, 1894, Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 61; Bransford file, Plumas County Museum

8 "Men and Events Linked with Great Mines of Park City," Park Record, June 5, 1931; George A Thompson and Fraser Buck, Treasure Mountain Home (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 1981), p 83

Utah's Silver Queen

Master of Salt Lake City's Masonic Lodge.9

Grace and Harold, who had attended Park City's small grammar school, soon were enrolled in Rowland Hall in Salt Lake City, fashionably attired, and gifted with everything money could buy. Grace, a small, frail, quiet child, did not excel in school and clung to her mother. Before the Emerys began to travel, Susie spent time with her two small charges and carefully supervised their daily activities. Later, however, she hired a governess. Harold did not seem to mind; he could visit his father who had married a second time and lived in Salt Lake City But Grace brooded when her parents left her with the servants

Albion's health began to fail in March 1894. Chest pains and coughing spells made sleeping difficult. On his doctor's advice, he took Susie and her sister Nellie to California and Hawaii for two months When they returned to California he collapsed and was confined to bed in San Francisco's Bella Vista Hotel About five weeks later, onJune 13, 1894, he died of liver and heart failure at the age of forty-eight Apparently he was an alcoholic; nearly four dozen bottles of liquor and club soda were charged to his bill during his five-week stay. Possibly the liquor served as an anesthetic during his final hours. A recent magazine article suggested that Albion died in the arms of another woman, but that is not true. Susie and Nellie were with him when he died, and Susie, who had been at his side for several weeks, tenderly closed his eyes when death finally came. 10

Susie was overwhelmed with grief and stress the summer and fall of 1894, for her father had died of a pneumonia-like illnessjust three weeks before Albion's death. The loss of these two beloved men and, later, the

1,1 Park Record,

The Emerys' adopted daughter Grace. Courtesy of Stella Inge.

9 "Honorable A B Emery" (editorial) and "Death of Honorable A B Emery," Park Record, June 16, 1894; Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, pp 83-84; Millsaps interview; Polk's Sail Lake City Directory, 1894.

June 16, 1894; "Brother Albion B. Emery," Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Utah, 1895, Utah Masonic Lodge, Salt Lake City, pp. 95-98; Albion Emery, Probate Case #102, Summit County records; Godfrey, "The Silver Queen," pp 33-34; Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, pp 83—84; Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 61; Wallace Bransford affidavit, pp 2-3

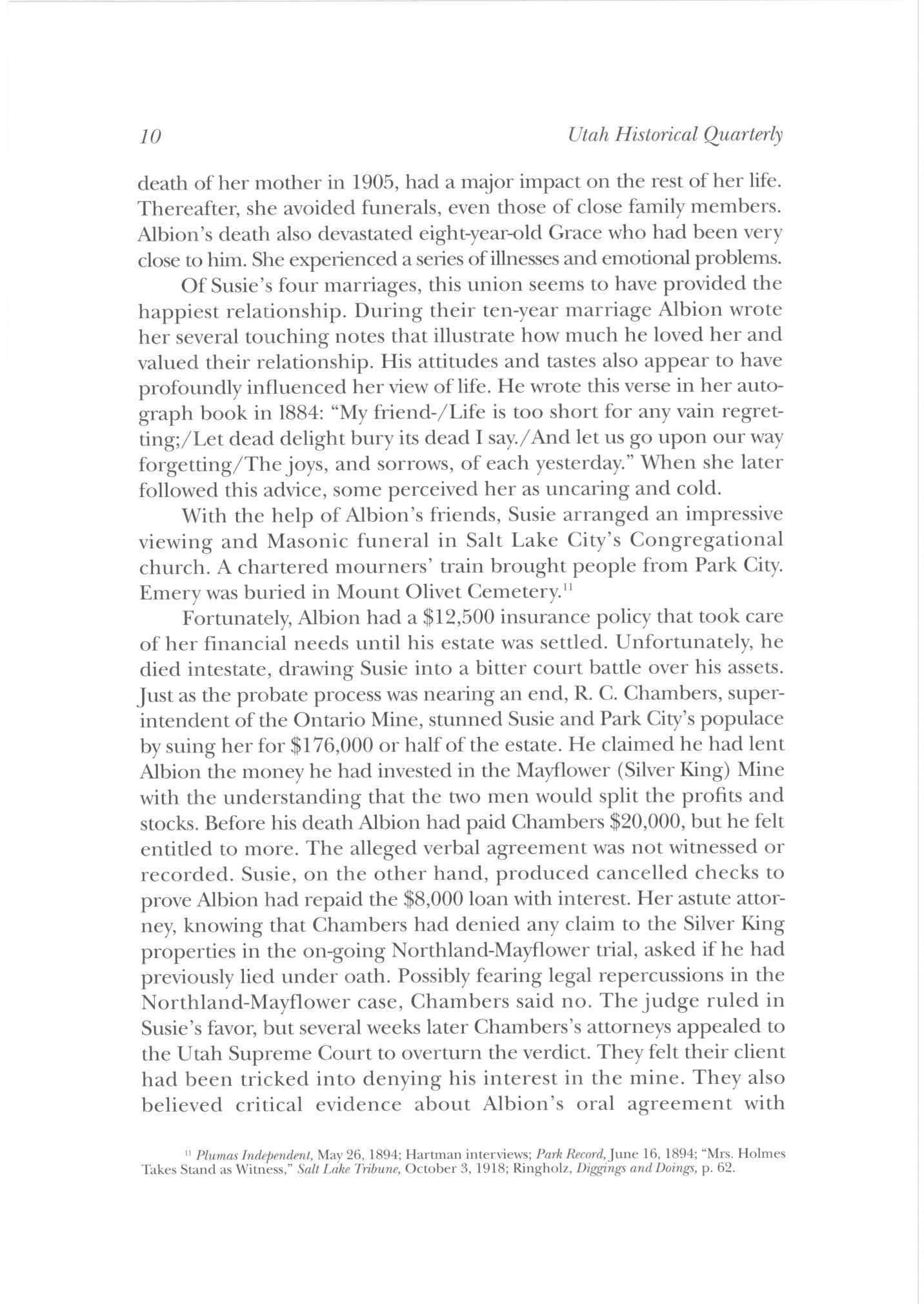

death of her mother in 1905, had a major impact on the rest of her life. Thereafter, she avoided funerals, even those of close family members Albion's death also devastated eight-year-old Grace who had been very close to him She experienced a series of illnesses and emotional problems

Of Susie's four marriages, this union seems to have provided the happiest relationship During their ten-year marriage Albion wrote her several touching notes that illustrate how much he loved her and valued their relationship His attitudes and tastes also appear to have profoundly influenced her view of life. He wrote this verse in her autograph book in 1884: "My friend-/Life is too short for any vain regretting;/Let dead delight bury its dead I say./And let us go upon our way forgetting/The joys, and sorrows, of each yesterday." When she later followed this advice, some perceived her as uncaring and cold.

With the help of Albion's friends, Susie arranged an impressive viewing and Masonic funeral in Salt Lake City's Congregational church A chartered mourners' train brought people from Park City Emery was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery."

Fortunately, Albion had a $12,500 insurance policy that took care of her financial needs until his estate was settled. Unfortunately, he died intestate, drawing Susie into a bitter court battle over his assets. Just as the probate process was nearing an end, R C Chambers, superintendent of the Ontario Mine, stunned Susie and Park City's populace by suing her for $176,000 or half of the estate He claimed he had lent Albion the money he had invested in the Mayflower (Silver King) Mine with the understanding that the two men would split the profits and stocks. Before his death Albion had paid Chambers $20,000, but he felt entitled to more. The alleged verbal agreement was not witnessed or recorded. Susie, on the other hand, produced cancelled checks to prove Albion had repaid the $8,000 loan with interest. Her astute attorney, knowing that Chambers had denied any claim to the Silver King properties in the on-going Northland-Mayflower trial, asked if he had previously lied under oath Possibly fearing legal repercussions in the Northland-Mayflower case, Chambers said no. The judge ruled in Susie's favor, but several weeks later Chambers's attorneys appealed to the Utah Supreme Court to overturn the verdict. They felt their client had been tricked into denying his interest in the mine. They also believed critical evidence about Albion's oral agreement with

10 Utah Historical Quarterly

" Plumas Independent, May 26, 1894; Hartman interviews; Park Record, June 16, 1894; "Mrs Holmes Takes Stand as Witness," Salt Lake Tribune, October 3, 1918; Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 62

Chambers had been wrongly ruled inadmissible. After several weeks of deliberation the justices ruled in Susie's favor. Under Utah probate law she and Grace equally shared Albion's assets.

Years later several eastern newspapers reported that Susie's estate in 1900, five years after the trial, was valued at $50,000,000 to $100,000,000 because they believed she had inherited 150,000 shares of Ontario stock. No Ontario stock is mentioned in Albion's probate papers The Silver King Mine may have been valued at $50,000,000 by 1900, but Susie was only one of the original six owners. The stock had split several times since 1892, and there were more investors. It appears that her assets in 1895 probably amounted to only $350,000 when $3,234 in cash, $13,972 in promissory notes, and the Salt Lake City residence were added to the stocks in Albion's portfolio—not the many millions some have claimed.12

Susie's beauty and charm attracted the attention of many men during her widowhood, for she was still a beautiful brunette with the quick wit and intellect of a good conversationalist. She also impressed people with her independent spirit and by capably handling her own money and investments. Sometime in 1895 her business partner Thomas Kearns introduced her to a wealthy Chicago businessman, Col. Edwin F. Holmes, whose lumber leases in Idaho, shipping investments in the Great Lakes area, and stock in the Anchor Mine were worth approximately $8,000,000. Fourteen years Susie's senior, Holmes had been widowed in 1894 also. He would actively pursue Susie during the next four years. 13

Utah's Silver Queen 11

Susie's brother, John Bransford, managed her financial affairsfor many years. USHS collections.

' - Emery Probate Records; Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, pp 84, 79; "For a Fortune," Park Record, September 1894; Park Record, June 5, 1931; "Chambers vs Emery," Pacific Reporter, 45: 192-200; Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, pp 61-63

13 Elite article in Susie's scrapbook; Lester, Brigham Street, p Ill ; "Mrs Emery Comes Here to Wed," unidentified article from Stella Inge that describes Holmes, now in author's possession.

In the meantime, Susie became concerned about Grace's education The girl was frequently absent from school because of illness or emotional problems. Hoping to improve the situation, she enrolled her in a prestigious San Francisco boarding school in 1898. Susie moved into a hotel apartment nearby but insisted that Grace live in the school dormitory. This forced separation from her mother made the girl hysterical. During one of these tearful sessions Grace met her first cousin Wallace Bransford, John's only son, who was attending the University of California in Berkeley. He arranged for Grace to stay with his family in Quincy, California, for a few months. Susie was grateful Colonel Holmes was courting her, and she did not have the time or energy to deal with Grace's possessiveness and brooding.

Later in 1898John Bransford moved his family and Grace to Salt Lake City where Susie hired him as her financial advisor Their business partnership was mutually beneficial; her investments flourished and he started a floral business and built some real estate holdings for his own family. He also embarked on an impressive political career, eventually serving as Salt Lake City's mayor during 1907-11 Together they built the Emery Holmes, Grace Louise Emery, and Craig apartments and the Semloh Hotel (Holmes spelled backwards)—all excellent rental properties

After seeking Susie's hand for several years, Colonel Holmes tried once more at the fashionable Delmonico Restaurant in NewYork City where they were dining with some wealthy Utah friends One local biographer claims he plucked a red rose from the table's centerpiece, tossed it to Susie, and announced their marriage to the group. Stunned by his cleverness and persistence, she accepted and they were married on October 12, 1899, in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. After a simple ceremony and reception they took a lengthy honeymoon around the world Holmes showered Susie with gifts, beautiful clothes, jewelry, and many collectibles both before and after their marriage. Susie surprised many of her family and friends when she decided to keep her former married name and asked to be called Mrs EmeryHolmes. Entranced by her beauty, wit, and intellect, the colonel catered to her every whim, including this unusual request.

To be near their Park City mining interests and Susie's family, Holmes purchased one of Salt Lake's most impressive mansions, the Gardo House (Amelia's Palace) from the Mormon church for $46,000. This five-story Second Empire home, with a tower and basement, had been built in the 1870s for Brigham Young. Susie hired William

12 Utah Historical Quarterly

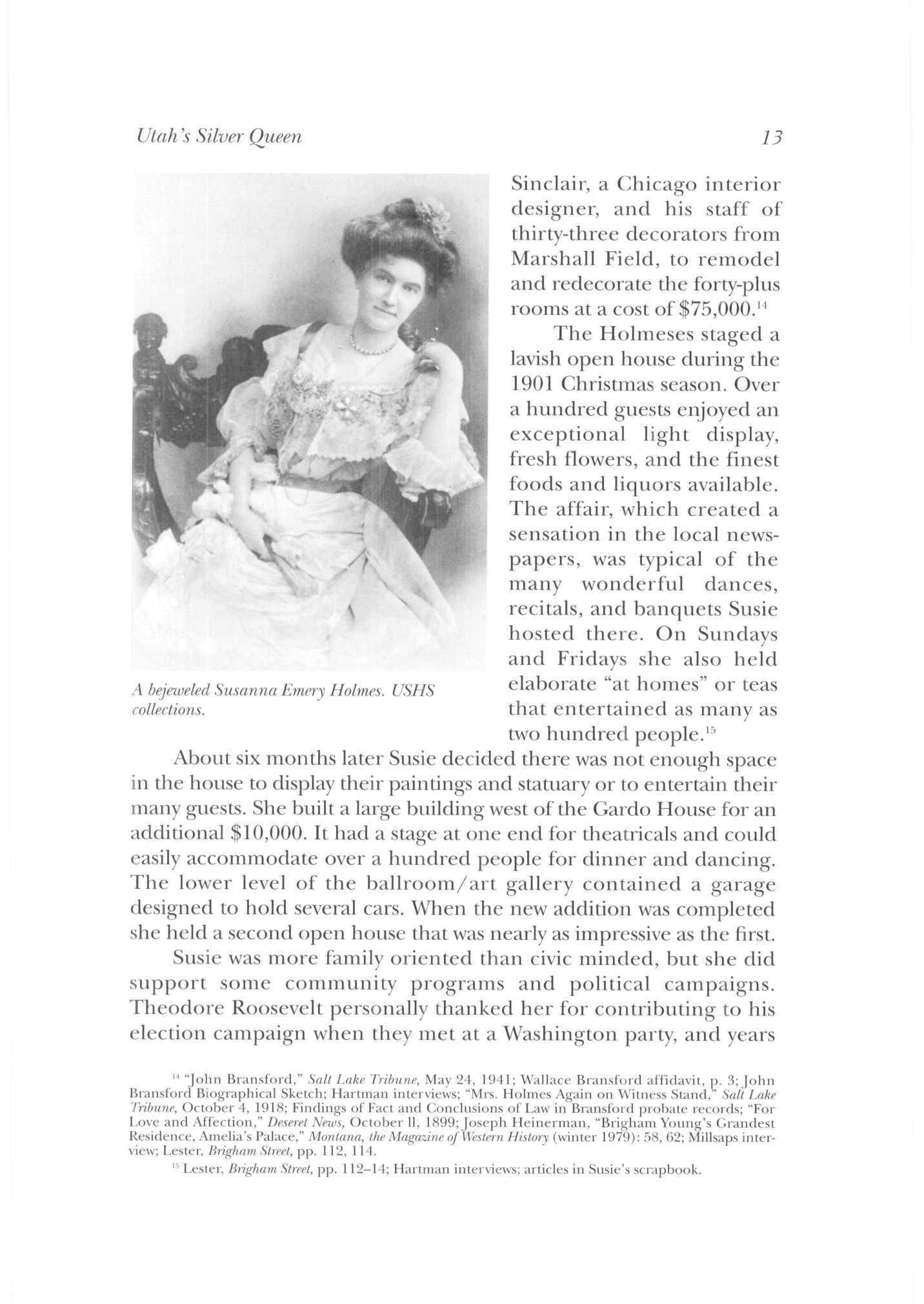

Sinclair, a Chicago interior designer, and his staff of thirty-three decorators from Marshall Field, to remodel and redecorate the forty-plus rooms at a cost of $75,000.'1

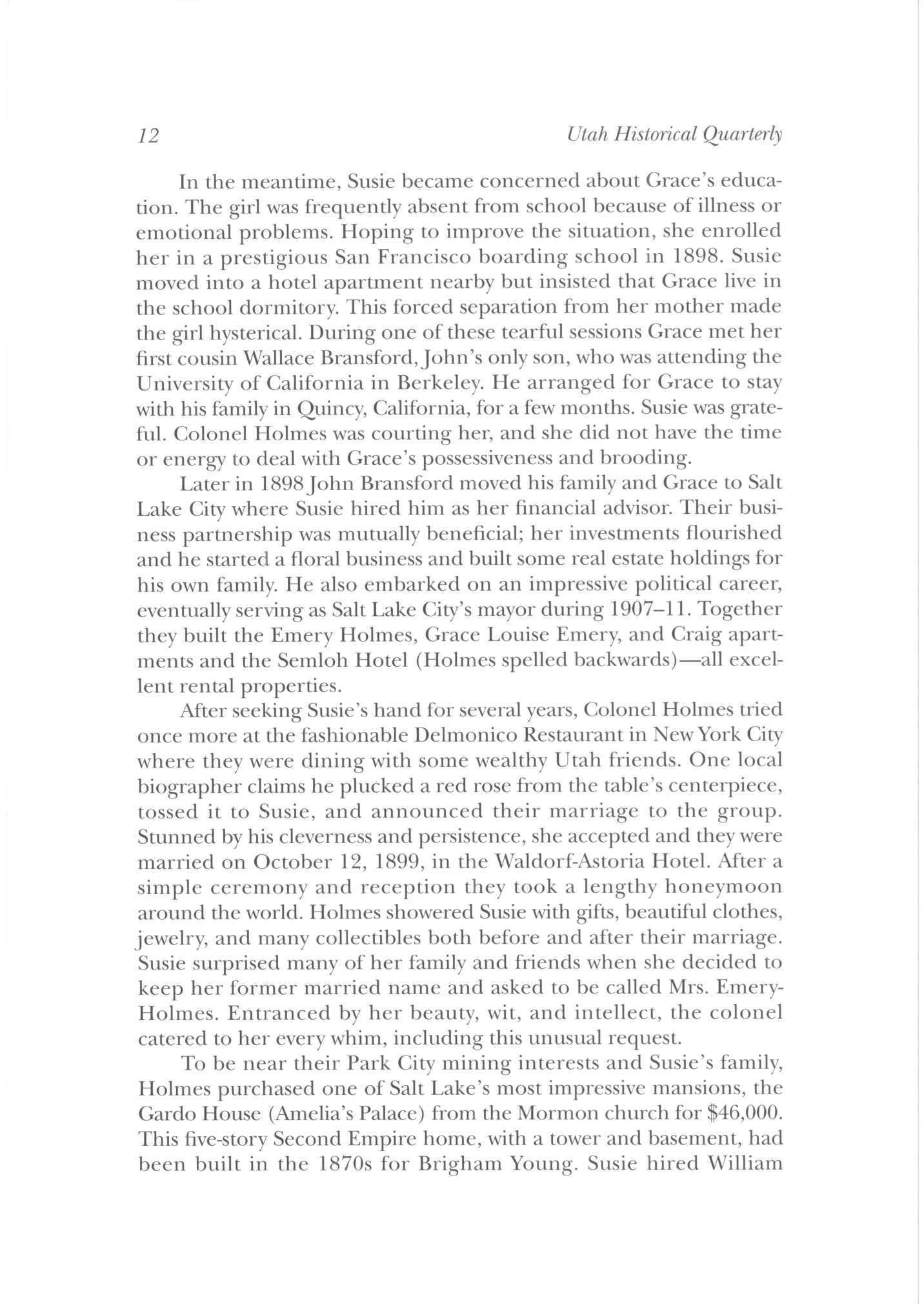

The Holmeses staged a lavish open house during the 1901 Christmas season. Over a hundred guests enjoyed an exceptional light display, fresh flowers, and the finest foods and liquors available. The affair, which created a sensation in the local newspapers, was typical of the many wonderful dances, recitals, and banquets Susie hosted there On Sundays and Fridays she also held elaborate "at homes" or teas that entertained as many as two hundred people.15

About six months later Susie decided there was not enough space in the house to display their paintings and statuary or to entertain their many guests. She built a large building west of the Gardo House for an additional $10,000. It had a stage at one end for theatricals and could easily accommodate over a hundred people for dinner and dancing. The lower level of the ballroom/art gallery contained a garage designed to hold several cars. When the new addition was completed she held a second open house that was nearly as impressive as the first.

Susie was more family oriented than civic minded, but she did support some community programs and political campaigns

Theodore Roosevelt personally thanked her for contributing to his election campaign when they met at a Washington party, and years

15 Lester, Brigham Street, pp 112-14; Hartman interviews; articles in Susie's scrapbook

Utah's Silver Queen 13

A bejeweled Susanna Emery Holmes. USHS collections.

14 "John Bransford," Salt Lake Tribune, May 24, 1941; Wallace Bransford affidavit, p 3; John Bransford Biographical Sketch; Hartman interviews; "Mrs. Holmes Again on Witness Stand," Salt Lake Tribune, October 4, 1918; Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Bransford probate records; "For Love and Affection," Deseret News, October 11, 1899; Joseph Heinerman, "Brigham Young's Grandest Residence, Amelia's Palace," Montana, the Magazine of Western History (winter 1979): 58, 62; Millsaps interview; Lester, Brigham Street, pp 112, 114

later shesupported hiscousin Franklin Roosevelt. Backers of Charles Evans Hughes sought hersupport, butshe gave it toWoodrow Wilson instead. She staged at least one charity function for the Orphan's Home and DayNursery Association, and a 1902publication commended her generosity to the city's poor and the newspaper boys. Additionally, she gave money to the symphony orchestra. Fora time she also donated to theSalvation Army, butthat probably ended when Gen William Booth, commander in chief ofthe organization, publicly rebuked her in the Salt Lake Theatre for fanning herself during his speech Shefelt humiliated.16

Susie was very generous with her family and helped her mother, sister, andbrother andtheir families on numerous occasions. Sheparticularly adored her mother, Sara, and after herfather died built her mother and heryounger sister, Nellie, a large home at 521 East 100 South.17 When Nellie showed an interest in studying piano Susie sent

14 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Silver Queen and her second husband, Col. Edwin E Holmes, were photographed in Ogden soon after their marriage. Courtesy of Stella Inge.

"' Millsaps interview; interview with Sandy Brimhall, author of a manuscript on the Gardo House; "Fan Annoyed General," article in Susie's scrapbook; Biographical Record of Salt Lake City, p 211; "Mrs Emery-Holmes's Public Reply to Hughes Supporters," Salt Lake Tribune, September 9, 1916 17 Polk's Salt Lake City Directory, 1894; Hartman interviews.

her to the Boston School of Music, but modest Nellie refused money to buy fancy clothes and other luxuries and also declined Susie's offer to promote her socially Nellie did allow her sister to give her a lavish wedding in 1900, however; and one source claims she helped the young couple financially with a gift of mining stocks valued at $50,000.18

Susie's relationship with her adopted daughter Grace, on the other hand, often proved stressful. After 1900 Susie enrolled Grace in an exclusive girls' school in Washington, D.C., and found an apartment nearby. News articles from 1902-4 describe Grace as a sweet and pretty girl, but stress in the mother-daughter relationship surfaced when outgoing Susie tried to push shy Grace into social situations. Susie, who had big plans for her daughter, sent her on a trip to Europe to develop her mind and cultivate her manners On more than one occasion she told family members that she hoped to marry Grace into one of Europe's royal families; the Swedish royal family particularly interested her Grace, though, was not interested in traveling, visiting museums, or a possible royal marriage. She kept in touch with her cousin Wallace Bransford by letter, and when they were home from school they were inseparable. Wallace listened sympathetically when she complained about her mother's inattentiveness and efforts to control her life. Susie complained in turn to Nellie that Grace was odd, slow, and unappreciative.

When Grace turned eighteen she openly clashed with her mother over the management of her money. Susie wanted to put it into a trust fund and manage it for her, but Grace wanted control of her own finances. The real break occurred when Grace told Susie that she wanted to marry Wallace. Susie refused to consider it at first because she felt Grace was too young. Wallace was twenty-three, had recently graduated from the University of California at Berkeley and was unemployed Susie did not dislike her nephew, but he was not the son-inlaw she had envisioned She expected her brother to support her in the matter, but he chose not to interfere.19

Finally, after several tense discussions, Susie agreed to a quiet wedding at home on September 4, 1904. She andJohn signed as witnesses on the marriage license. The wedding was announced in the Deseret Nexus and the Salt Lake Tribune the day it occurred, but no one outside

Utah's Silver Queen 15

18 Hartman interviews; Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 62

19 Hartman interviews; Wallace Bransford affidavit; Salt Lake Tribune, October 4, 1918; Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Bransford probate records

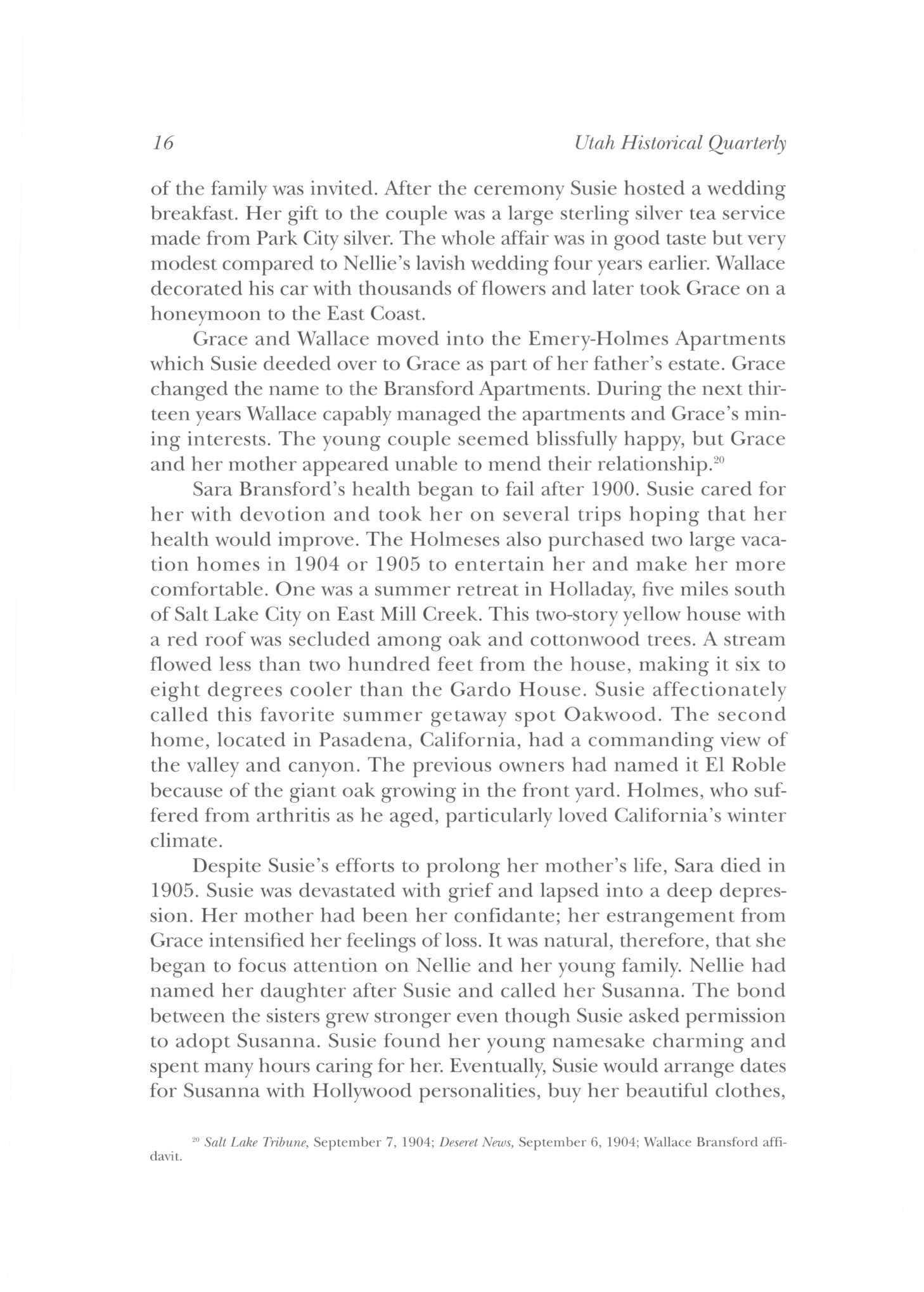

of the family was invited. After the ceremony Susie hosted a wedding breakfast. Her gift to the couple was a large sterling silver tea service made from Park City silver The whole affair was in good taste but very modest compared to Nellie's lavish wedding four years earlier. Wallace decorated his car with thousands of flowers and later took Grace on a honeymoon to the East Coast.

Grace and Wallace moved into the Emery-Holmes Apartments which Susie deeded over to Grace as part of her father's estate Grace changed the name to the Bransford Apartments. During the next thirteen years Wallace capably managed the apartments and Grace's mining interests The young couple seemed blissfully happy, but Grace and her mother appeared unable to mend their relationship.20

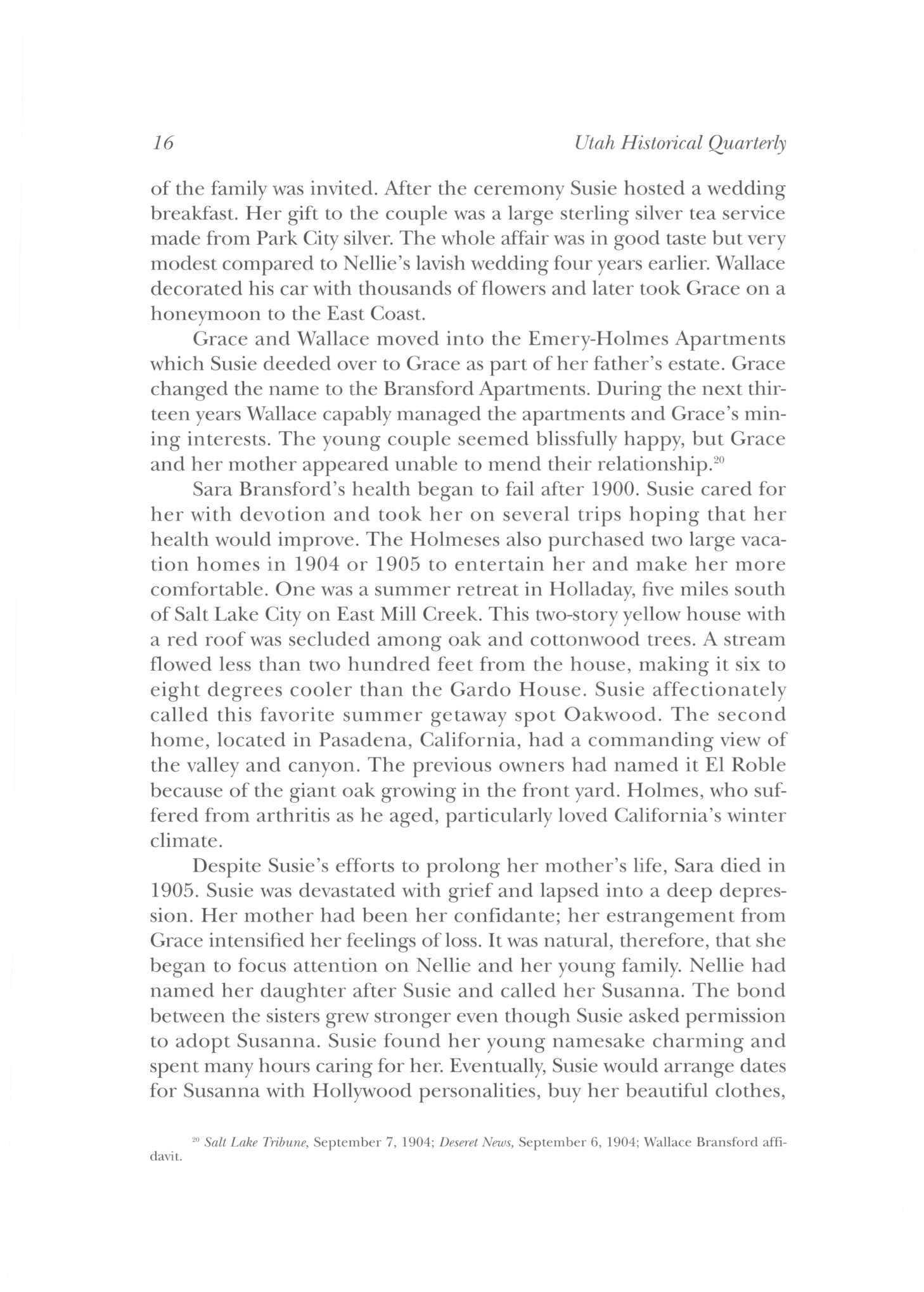

Sara Bransford's health began to fail after 1900 Susie cared for her with devotion and took her on several trips hoping that her health would improve. The Holmeses also purchased two large vacation homes in 1904 or 1905 to entertain her and make her more comfortable. One was a summer retreat in Holladay, five miles south of Salt Lake City on East Mill Creek. This two-story yellow house with a red roof was secluded among oak and cottonwood trees A stream flowed less than two hundred feet from the house, making it six to eight degrees cooler than the Gardo House Susie affectionately called this favorite summer getaway spot Oakwood. The second home, located in Pasadena, California, had a commanding view of the valley and canyon The previous owners had named it El Roble because of the giant oak growing in the front yard. Holmes, who suffered from arthritis as he aged, particularly loved California's winter climate.

Despite Susie's efforts to prolong her mother's life, Sara died in 1905 Susie was devastated with grief and lapsed into a deep depression. Her mother had been her confidante; her estrangement from Grace intensified her feelings of loss. It was natural, therefore, that she began to focus attention on Nellie and her young family Nellie had named her daughter after Susie and called her Susanna. The bond between the sisters grew stronger even though Susie asked permission to adopt Susanna. Susie found her young namesake charming and spent many hours caring for her. Eventually, Susie would arrange dates for Susanna with Hollywood personalities, buy her beautiful clothes,

16 Utah Historical Quarterly

20 Salt Lake Tribune, September 7, 1904; Deseret News, September 6, 1904; Wallace Bransford affidavit

and take her to elaborate parties. Meanwhile, Susie's relationship with her brotherJohn grew cooler. Their partnership continued for several years, but she would only communicate with him through their sister Nellie or a third party. Interestingly, in later years she would offer to pay his medical bills when she feared he was seriously ill but cautioned Nellie not to tell him who was paying the expenses. 21

In 1908 Grace contracted rheumatic fever, and its side effects handicapped her for the remainder of her life. Susie, apparently unaware of the seriousness of the disease for some time, did not visit her often. Grace resented her mother's lack of attention, while Susie complained to friends and family that Grace seldom invited her to her home and that she never had a chance to talk with her alone.

By contrast, Susie lavished attention on Harold Lamb, her nephew and foster son. She had sent him to Exeter, a posh boy's school, and later to Cornell University to pursue a degree in architecture. Very indulgent and generous, she may have encouraged him to be too dependent upon her. After a few years he tired of school and

Utah 5 Silver Queen 17

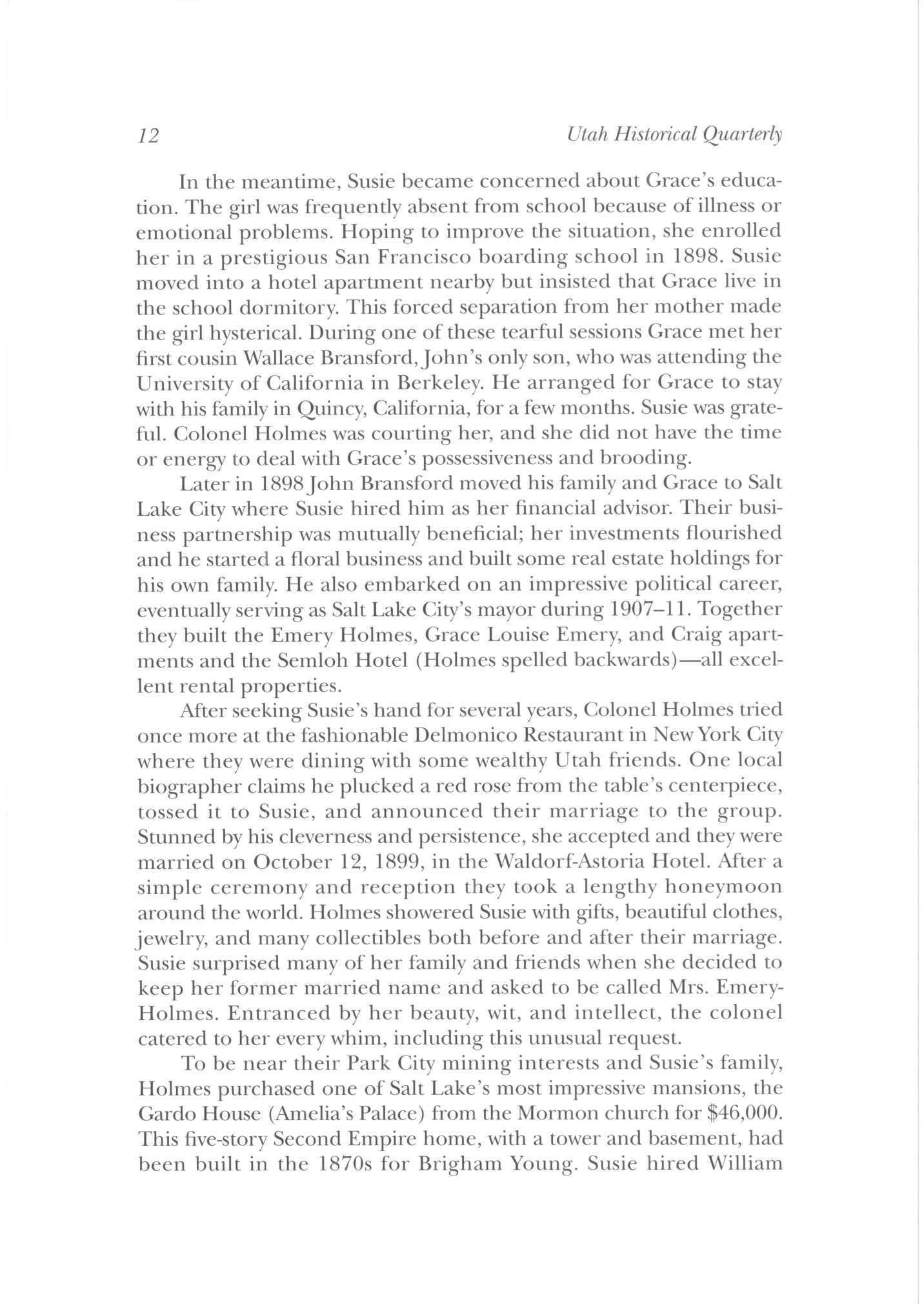

This view of the Gardo House shows the large addition built by Susie to house works of art and provide spacefor entertaining. Courtesy of Anne Bransford Newhall.

Hartman interviews; interviews with Dr Harold Lamb, great-nephew of Susie

returned to Salt Lake City before completing his degree. He was very talented, though, and soon found work with one of Utah's leading architectural firms—Treganza, Ware, and Cannon A short time later, in 1912, he married a Texas beauty, Grizzelle Houston. In 1915 Susie gave him a beautiful Prairie style home on Michigan Avenue in one of Salt Lake City's most desirable neighborhoods.

Grace's health steadily deteriorated, and in September 1917 her doctor advised her to vacation in Los Angeles, hoping a change of climate would help. On October 24, 1917, she suddenly collapsed and died at age thirty-one. Susie, the colonel, his children, and Adele Blood were visiting a hot springs in Virginia when word came that Grace had died. Adele later reported that Susie threw herself onto the bed and wept for several minutes when she read the telegram. However, she cabled Wallace that she would not return for the funeral, using the colonel's need to continue his treatment for pain as an excuse. To John and Wallace's amazement Susie did not send flowers to the funeral. Later she would explain that it was considered bad etiquette to send flowers to a relative's funeral In retaliation for this slight, Wallace arranged to have Grace buried across the street from her father's grave in Mount Olivet Cemetery so that she would not be near her mother's grave in the future.22

Grace left nearly all of her money, properties, and mining stocks to Wallace. Her will left $10,000 to Susie and $10,000 to Albion's surviving sisters. Many were surprised that Susie expected more, but she was livid with anger and frustration She had helped to generate Albion's fortune, had tried to provide her daughter with educational and social opportunities as she grew to maturity and had expected Grace to be more appreciative. In addition, Susie still harbored resentment against Wallace for interfering with her plans for Grace His numerous critical comments about Susie to mutual friends over the years had also irritated her. The Salt Lake Tribune announced on January 21, 1918, that Susie intended to sue for half of Grace's estate which amounted to about $800,000

The trial, which began on September 15, 1918, had a devastating effect on her reputation. The daily media coverage was frequently critical of her and colored many local citizens' perceptions of her Susie alleged that Wallace had coerced Grace into leaving him all of her

18 Utah Historical Quarterly

22 Wallace Bransford affidavit and Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Bransford probate records; Lamb interviews; " Mrs Bransford Dies in California," Salt Lake Tribune, October 25, 1917; "Actress Testifies in Bransford Case," Salt Lake Tribune, October 19, 1918

assets. Her attorneys subpoenaed doctors, teachers, and servants, hoping to show that Grace was incapable of making sound decisions because she was mentally incompetent, poorly educated, and sickly.

Wallace's attorneys countered by subpoenaing all the Bransford friends and associates to show that the couple was happily married and that Grace had been mentally competent. Susie's attorneys also subpoenaed Adele Blood, Wallace's first cousin on his mother's side of the family They hoped she could convince thejudge that Wallace was domineering and inconsiderate of Grace and had prevented the mother and daughter from reconciling their differences. This tactic backfired when unsubstantiated rumors circulated in the city that Susie had adopted Adele or intended to after the trial.

Judge Stevens rejected the stories about Grace's subnormal intelligence and poor judgment because he felt they could not be substantiated Ruling in Wallace's favor, he described Susie as a self-absorbed and flagrantly negligent parent. She was furious and hurt. In particular, she felt that she had been unjustly maligned throughout the trial and that her efforts to educate and care for Grace had not been appreciated. Her attorneys immediately filed an appeal to the Utah Supreme Court, but the court refused to hear the case. 23

Susie was nearly sixtyyears old when she sued Wallace. She may have been seeking revenge because he had interfered with her plans for Grace's future More likely, though, she simply needed the money Money was a prerequisite for membership in some prestigious eastern social groups. For decades she had been known throughout the United States and Europe for her elaborate parties, beautiful clothes, and impressive jewelry. As she aged she spent extravagantly on travel and luxuries and did not manage her money aswisely as she once had. Moreover, Holmes planned to leave his entire fortune to his four children.24

After the trial Susie and the colonel returned to El Roble. During the next six years they fully participated in Pasadena's social life, entertaining often and attending parties hosted by many prominent people Susie transformed El Roble from a wood-shingled structure to a Tudor mansion for $37,000 in 1922. During their travels the colonel had added to his extensive collection of paintings, statuary, and other

23 The account of the trial is drawn from court records in Utah State Archives and some two dozen articles that appeared in the Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret Fvening News, October 1918 through January 1919; "Mrs Holmes Loses Suit Against Bransford," Deseret Evening News, January 25, 1919; "Florist Testifies in Will Contest," Salt Lake Tribune, October 22, 1918; interviews with Anne Bransford Newhall, granddaughter of Wallace and Edna Bransford, summers of 1993 and 1994

24 Colonel Holmes probate papers, #14129, Utah State Archives; Hartman interviews

Utah's Silver Queen 19

El Roble, the Pasadena home of the Holmeses. Inset shoius original Arts and Crafts style house that Susie remodeled into the Tudor mansion shown below. The recent television movieThe Christmas Box wasfilmed there. Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Marshall Morgan.

mementos from Europe, Asia, and Africa, and El Roble soon resembled an elaborate art museum. By the mid-1920s the home and its contents were valued at more than a million dollars.25 After losing Grace, Susie made a point of staying in touch with Harold Lamb and his young family. On trips to Salt Lake City she invited them to her penthouse in the Hotel Utah or visited them at Oakwood. She gave each child a $50 bill for his birthday and Christmas for many years. Once she invited Harold, Jr., to ride with her in the Rose Bowl Parade. To make the event more memorable she purchased the Prince of Wales' Rolls Royce for the occasion. The two of them looked very regal in their best clothes as they drove down Pasadena's streets in the shiny yellow car.

20

Historical

Utah

Quarterly

!5 "Romantic History Adds Glamour to Eleventh Showcase Design," Pasadena Star, April 17, 1975; Pasadena Junior Philharmonic Committee, Showcase ofInterior Design on El Roble Residence, undated, courtesy of Pasadena City Library

About the time she sold the Gardo House in 1920, Susie deeded Oakwood to Harold and his family. He was overjoyed. With its tall trees, stream, and large garden, the home would make an ideal place to raise his three children. Tragically, Harold died of appendicitis on May 14, 1925, at age thirty-eight His wife was devastated to discover that he had no savings or life insurance. Susie stepped in to provide Grizzelle with $300 a month until she remarried several years later. Then, with a new father in the picture, Susie and her foster grandchildren drifted apart. Of all Susie's relationships those with her husbands have generated the most speculation. One historian reported that Susie once jokingly told Jennie Kearns, wife of Thomas Kearns, that she had a difficult time keeping husbands Unfortunately, this was true Only one of her four marriages lasted more than ten years, and she outlived all of her husbands even though the last two were many years younger. Susie's relatives remembered Colonel Holmes as a kindly gentleman who indulged Susie's eccentricities. 2 6 At first, the couple appeared very happy and Susie seemed content to live and entertain in Utah But as time passed she outgrew Salt Lake City and frequently traveled alone to Washington and Europe. She may have felt that Holmes, with all of his business and social interests, neglected her. Prior to 1910 he was very involved in politics and the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce; he also served as commissioner of the water supply. Socially, he had a wide range of contacts as a Mason, as a member of the Alta Club, the University Club, and the Salt Lake Country Club, and as president of the Commercial Club While Grace was a student in Washington, D.C., Susie had an excuse to go there. Later she continued to spend several months a year in the East. Many of her friends were members of prominent eastern families, including congressmen and their wives She was a frequent guest at parties in Washington and New York and hosted some extravagant events herself.27 Some of her socials were so lavish that they prompted a rebuke from Colorado's Tom Walsh, who liked to think of himself as Washington's king of entertainers Supposedly, Holmes grew impatient with her long absences and ordered her to return to Utah, threatening to sell the Gardo House if she did not.28

Despite the many examples of generosity to her family, Susie

Utah's Silver Queen 21

26 Hartman interviews; Lamb interviews; Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 64

-' Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 63; Lester, Brigham Street, p 117; Bransford affidavit, Bransford probate records; Hartman interviews; unidentified clippings in Susie's scrapbook.

28 Salt Lake Herald, December 15, 1903, Susie's scrapbook; Lester, Brigham Street, p 117

appeared unkind to her loved ones at times.When Colonel Holmes died September 30, 1925,at age eighty-two, he had been living in Illinois with his two unmarried daughters for two years. Susie, age sixty-six, was traveling when she received a cable notifying her of his death. She told his children to bury him next to their mother,Jennie, as that had been his wish, and not to expect her at the funeral. In reality, she may have feared a confrontaion with his children as he had signed some assets over to her after she lost the lawsuit in 1919 but did not change his will. She and the colonel had both lost money through the years as the value of their mining stocks had depreciated significantly. Perhaps she hoped her lawyers could reconcile the issue with his children so she could avoid dealing with them over the remainder of their father's estate.29

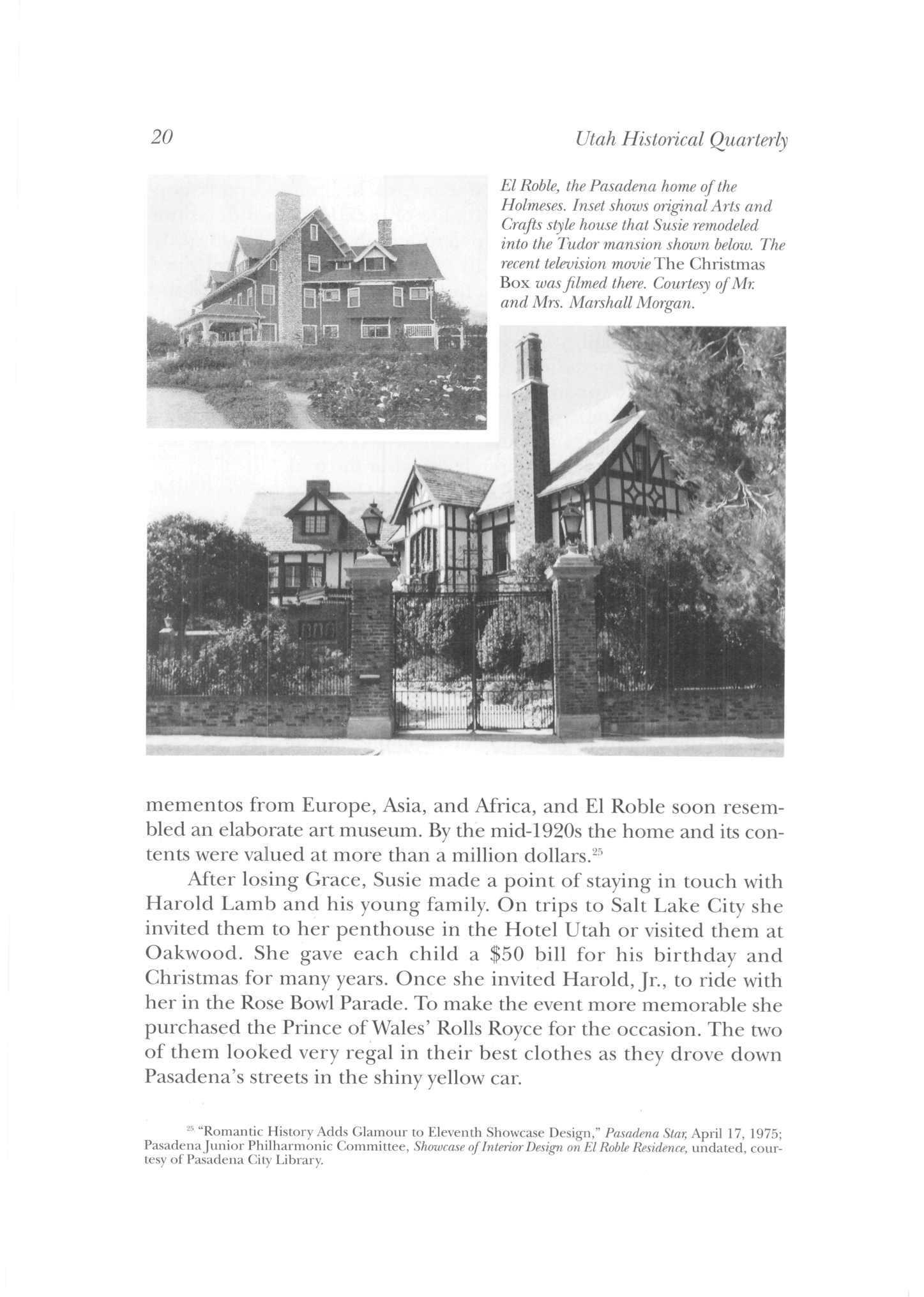

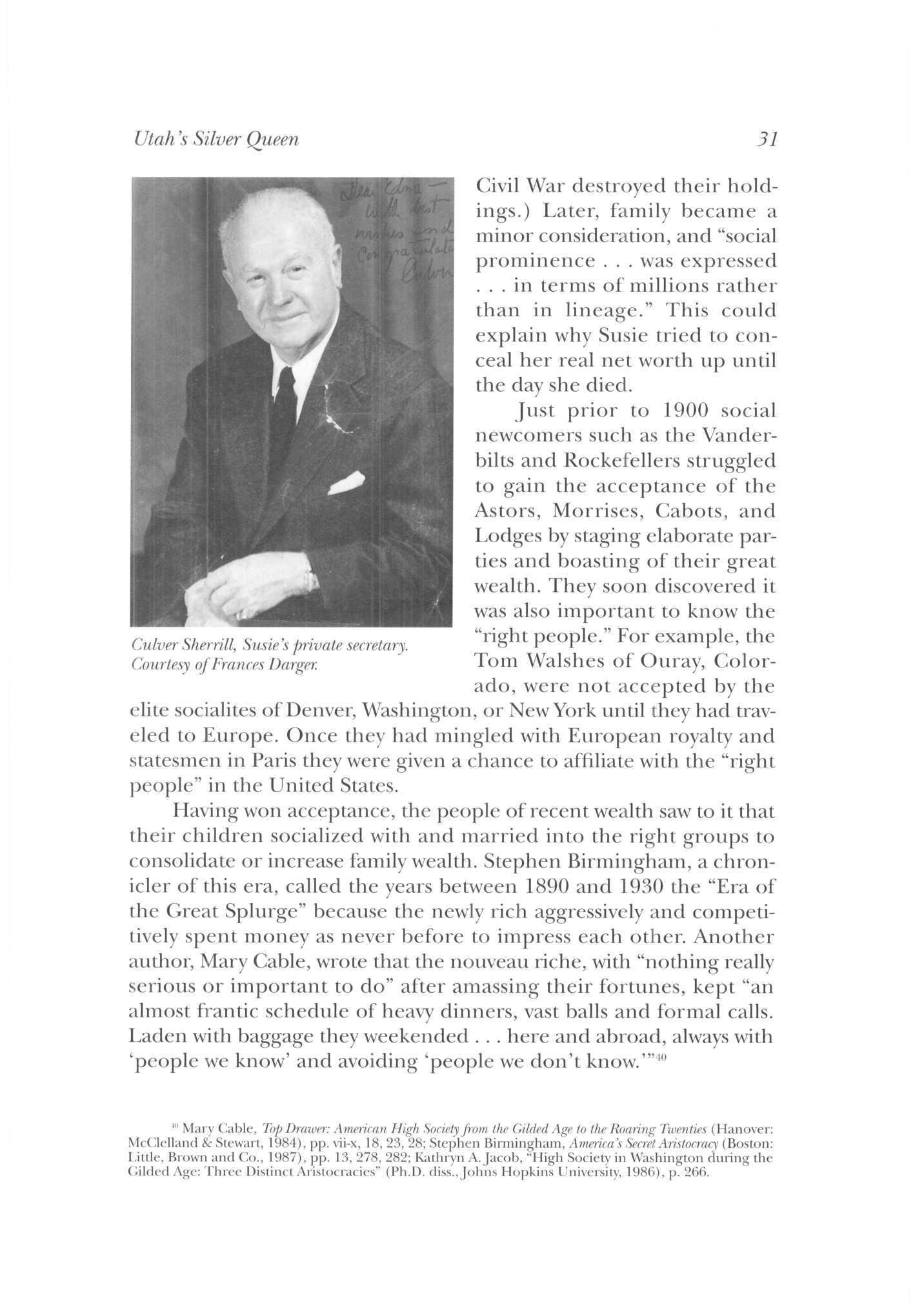

Susie closed El Roble and moved into the Plaza Hotel in NewYork to be near Adele and her daughter Dawn and her eastern friends She also hired a male secretary, Culver Sherrill, to manage her business affairs Time wasvery kind to her during these years At age seventy she was still a very attractive woman. Instead of slowing down, she continued to live life to the fullest measure She was personally acquainted with several presidents, including Franklin D. Roosevelt whose silverframed picture traveled with her Through the years she had met many famous Europeans such as Nicholas II of Russia, Hitler, Mussolini, Pope Leo, and Queen Victoria She had even attended Edward VII's coronation and danced with the Prince of Wales.

About 1928 Susie caught the eye of two Russian princes— Nicholas Engalitcheff, who claimed to be a descendant of Genghis Khan and a relative of the Romanovs, and David Dadiani, descended from Georgian aristocracy. Both were prominent members of New York society. Eventually, she chose the handsome and charming Engalitcheff as a suitor; possibly he was more exciting. Nicki, as he was affectionately called, and Susie decided to marry in 1928. Much to the prince's surprise and embarrassment, he was denied a marriage license because, the state of NewYork informed him, his second wife, Baroness Danise Melanie de Bertrand, was not legally dead despite her disappearance in Canada six years earlier.30

29 "Former Utahn Answers the Call," Park Record, October 2, 1925; "Col. Holmes, Once of Salt Lake, Dies East," Salt Lake Tribune, October 2, 1925; Lester, Brigham Street, p 119; Hartman interviews; Col Holmes probate papers; Col Holmes's probate from Illinois, #799; Petition to Holmes probate submitted to Kane County, Illinois, 1926

30 Hartman interviews; "America's 'Silver Queen' Passes Through Adelaide," Deseret News, August 25, 1930; "Silver Queen Ruled Lavishly for Forty Years," Deseret News, July 24, 1979; "Silver Queen Seeks Divorce," Salt Lake Telegram, November 1, 1932

22 Utah Historical Quarterly

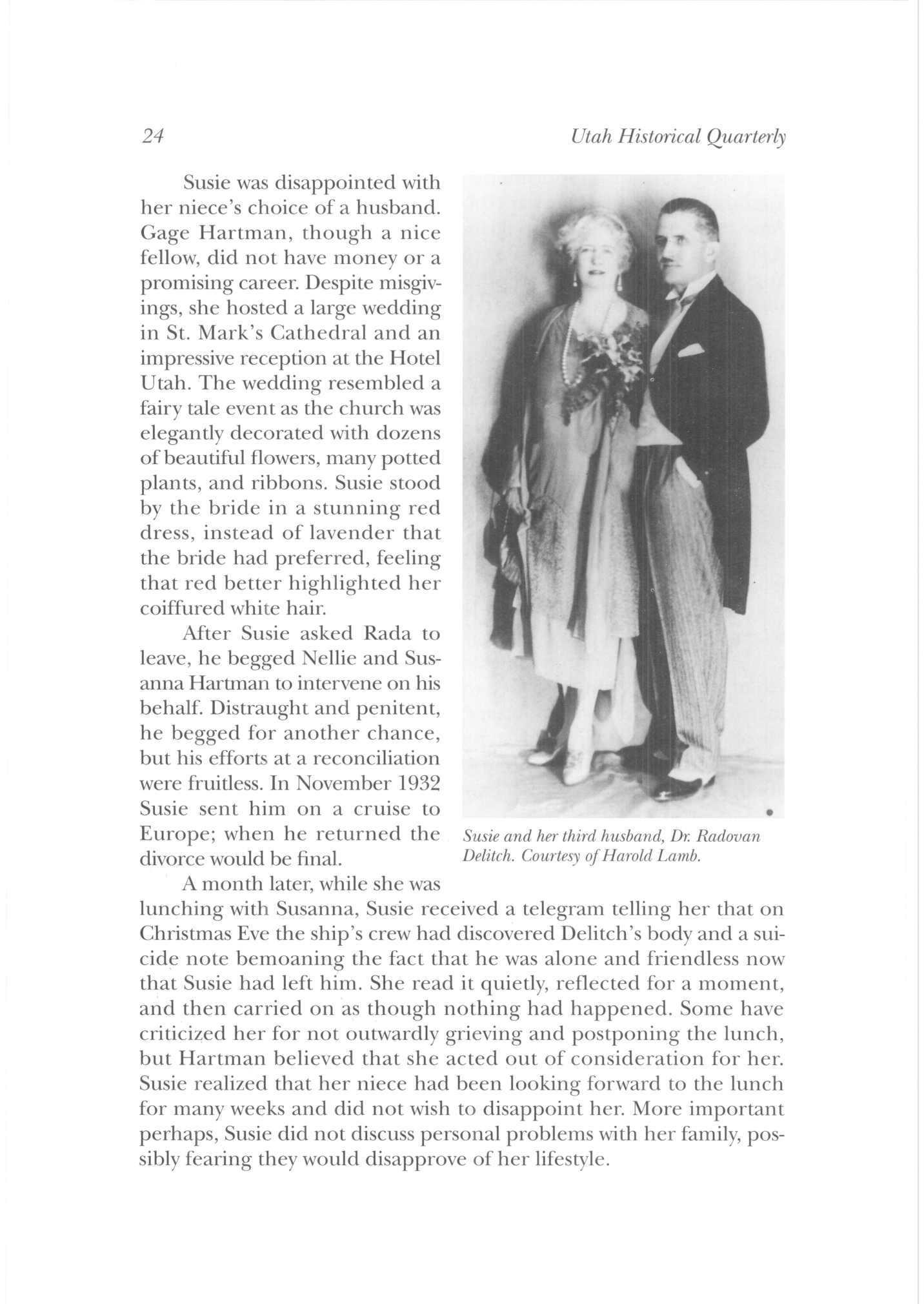

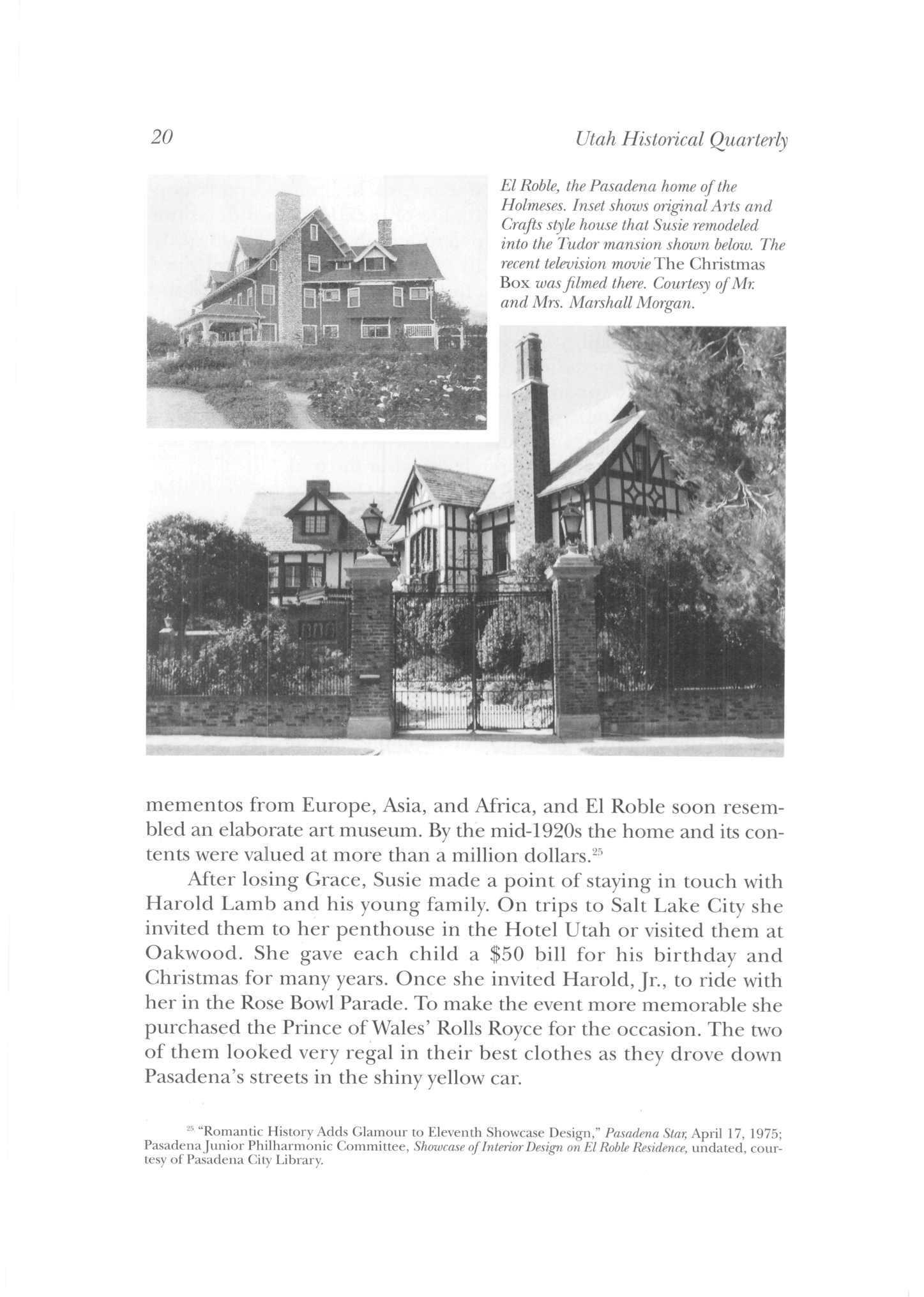

After this disappointment Susie was next romanced by a Yugoslavian doctor, Radovan Nobelkov Delitch, prominent in both American and European social circles. Affiliated with NewYork's Fifth Avenue Hospital, Rada had earned medals from the French and Yugoslav governments for his surgical skills during World War I. After the war he turned to research and became a noted cancer specialist. Surprisingly, the age issue did not trouble Susie or Rada even though he was nearly thirty years younger. They shared friends and a love of travel, parties, nice clothes, and "the good life." They were married in Radovan's Paris home on July 19, 1930; but Yugoslav tradition required a church ceremony, and so a second marriage took place in a Russian Orthodox church in Paris. At Susie's insistence Rada gave up his medical practice She convinced him that he did not need to work and that it would interfere with their travel plans.

The marriage caught most of NewYork society by surprise Even Nellie was stunned when she heard about her sister's latest marriage from newspaper reporters. Susie later tried to make amends by briefly visiting Salt Lake City to introduce Rada to Nellie and her Utah friends.

Between trips around the world the Delitches stayed in the Plaza Hotel, but their main residence was El Roble. Rada tried to adjust to married life, but within a short time it was obvious that he was unhappy He often withdrew to his study to read or sulk and would refuse to speak English Susanna Hartman, Susie's niece, remembered him wandering about the house muttering to himself and refusing to leave his room when company visited.

Delitch became veryjealous of Susie, and she complained that he made public scenes if she talked with other men. When she began attending social functions without him, he hired a detective to report her every move. A servant leaked a story to the newspapers that the couple quarreled about the way she spent her money Rada wanted her to reduce the number of her servants at El Roble to save money during the depression She refused because she worried that some might not find employment elsewhere. He was also concerned that Susie's stock dividends were dwindling. They did not have his former income to rely on, yet she insisted on traveling and entertainingjust the same. 31

Utah's Silver Queen 23

31 "Drawing Hidden Fortunes from Earth Finest Method, Avers Silver Queen,'" Salt Lake Telegram, September 6, 1932; Pasadena Star, February 5, 1933; "Utah Woman Back from Honeymoon," Salt Lake Tribune, October 2, 1930, "Mrs Emery-Holmes Is Bride of Physician at 71," Salt Lake Telegram, July 19, 1930; Hartnrarr interviews

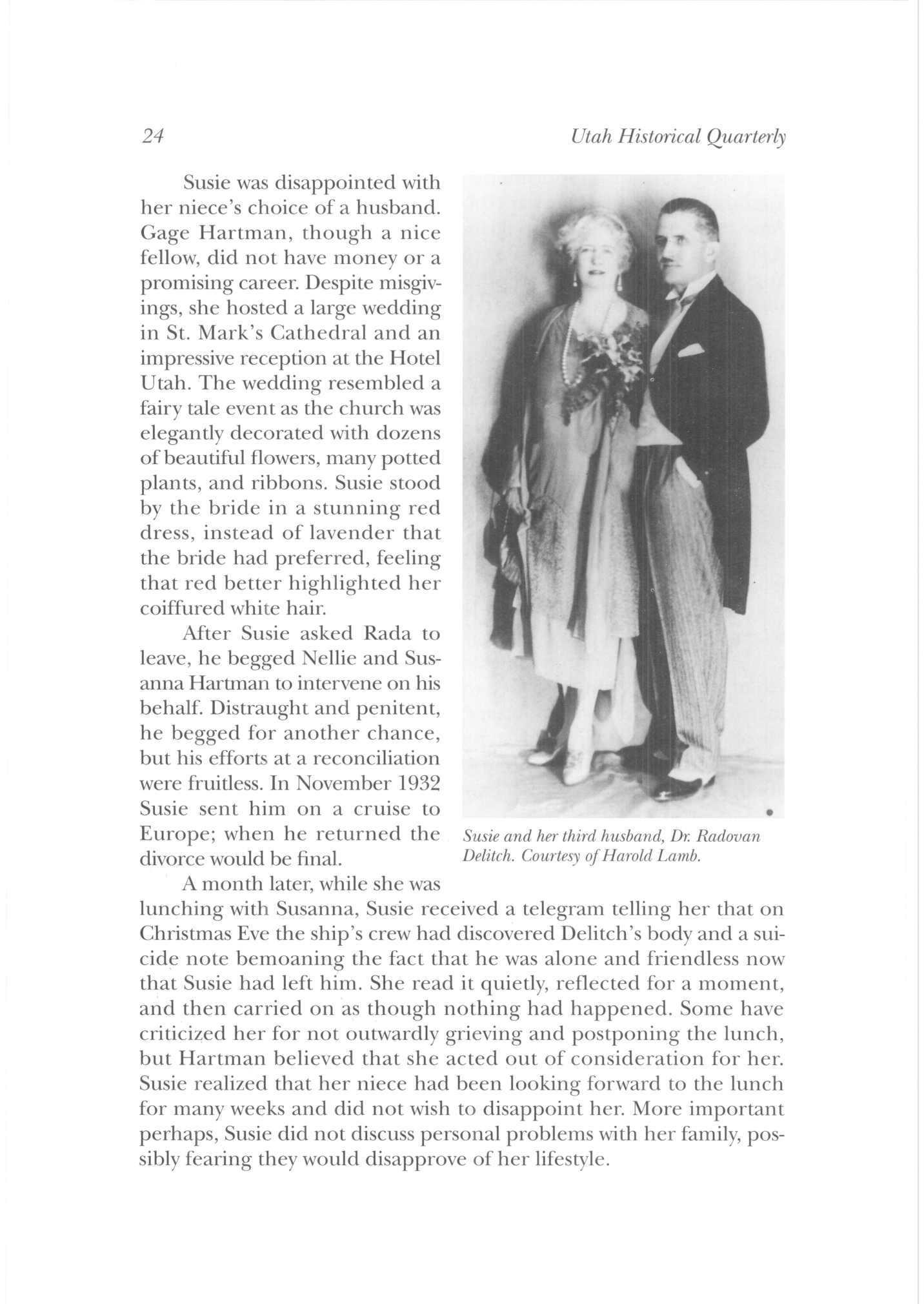

Susie was disappointed with her niece's choice of a husband Gage Hartman, though a nice fellow, did not have money or a promising career. Despite misgivings, she hosted a large wedding in St. Mark's Cathedral and an impressive reception at the Hotel Utah. The wedding resembled a fairy tale event as the church was elegantly decorated with dozens of beautiful flowers, many potted plants, and ribbons. Susie stood by the bride in a stunning red dress, instead of lavender that the bride had preferred, feeling that red better highlighted her coiffured white hair

After Susie asked Rada to leave, he begged Nellie and Susanna Hartman to intervene on his behalf Distraught and penitent, he begged for another chance, but his efforts at a reconciliation were fruitless. In November 1932 Susie sent him on a cruise to Europe; when he returned the divorce would be final.

A month later, while she was lunching with Susanna, Susie received a telegram telling her that on Christmas Eve the ship's crew had discovered Delitch's body and a suicide note bemoaning the fact that he was alone and friendless now that Susie had left him She read it quietly, reflected for a moment, and then carried on as though nothing had happened Some have criticized her for not outwardly grieving and postponing the lunch, but Hartman believed that she acted out of consideration for her Susie realized that her niece had been looking forward to the lunch for many weeks and did not wish to disappoint her. More important perhaps, Susie did not discuss personal problems with her family, possibly fearing they would disapprove of her lifestyle.

24 Utah Historical Quarterly

Susie and her third husband, Dr. Radovan Delitch. Courtesy ofHarold Lamb.

When she was alone, Susie dealt with her grief and also directed her secretary, Culver Sherrill, to arrange to have the Yugoslavian navy bury Delitch at sea. Years later she told a newspaper reporter that she was sure Rada had not committed suicide and that they would have reconciled their differences and lived happily at El Roble if he had not died unexpectedly.32

Within six weeks of Radovan's death, Susie sold El Roble. A Los Angeles company, George Fischer and Sons, was hired to handle the auction. More than 25,000 people came from southern California and elsewhere to tour the house Such treasures as the Prince of Wales' yellow and black Rolls Royce sold for only $700, while the jeweled goblets Tsar Nicholas II had given her went for $65 apiece The sale raised only $100,000. Later, the auction company acknowledged that the replacement value of the house and its contents in 1933 was over one million dollars, but the depression had undercut the market value Susie secluded herself to avoid publicity while her home and treasures were purchased by Anna C. Newcomb, the widow of James Newcomb of Standard Oil.33

A few months later Susie and Nicki Engalitcheff became engaged a second time She was seventy-four and he was sixty The marriage would be her fourth and his third. This time New York allowed them to proceed with a civil marriage on October 18, 1933, followed by a religious ceremony at the Russian Orthodox church on Houston Street about a month later One source claims the prince's gold crown was too large and fell down onto his nose during the church wedding. No matter, Susie was delighted with the marriage and her new title of princess.

It was not a love match Susie was more interested in a travel companion than an amorous relationship and there is evidence that Nicki openly admired her sister Nellie because she was more of a homemaker No doubt Susie also enjoyed the attention she received as the wife of a Russian prince It established her social legitimacy In public Nicki appeared to be a kind and charming man, but he was also pompous and condescending to women Susie seemed to enjoy catering to his needs, but that may have been a pose. Some have speculated that he was

32 Hartman interviews; Lamb interviews; and unidentified wedding announcement placed about September 1933 in a Salt Lake City newspaper.

33

Utah's Silver Queen 25

"'Silver Queen' Seeks Divorce," Salt Lake Telegram, November 1, 1932; Pasadena Star, February 5, 1933; "'Utah Silver Queen', 74, Weds 60 Year Old Prince," Salt Lake Tribune, October 20, 1933; "Palace of 'Silver Queen' Stripped of Treasures, Salt Lake Tribune, January 29, 1933; Hartman interviews

ill during most of their marriage or that he was an invalid and had a nurse. Susanna Hartman noted that he was a chain smoker and drank heavily.

Nicki died of a stroke on March 25, 1935 The couple were separated when he died; the obituary listed his residence as the Hotel Barclay, not the Plaza Hotel where Susie lived when she was in town. She was not with him when he died and did not attend his funeral. The autobiography of her business manager, Culver Sherrill, explains that Nicki left Susie for a younger woman soon after their honeymoon and that she refused to take him back when the affair ended. Despite the obituary that appeared in the New York Times and in the Salt Lake City newspapers, Susie told her family and western friends an incredible story that has been exaggerated and embellished over the years. She claimed that she and Nicki were traveling with friends when he died on a Mediterranean cruise. Rather than cancel the trip to bury him in the United States, she decided to store his body in a warehouse in one of the Mediterranean ports and take care of his funeral later When news of her plans leaked to the press some Russian nationals insisted that she give him a burial at sea befitting his rank She also claimed to have hired a woman to impersonate her at the funeral by wearing her clothes and a black veil.34 Perhaps she was evening the score for past injuries through her humorous version of his death and funeral.

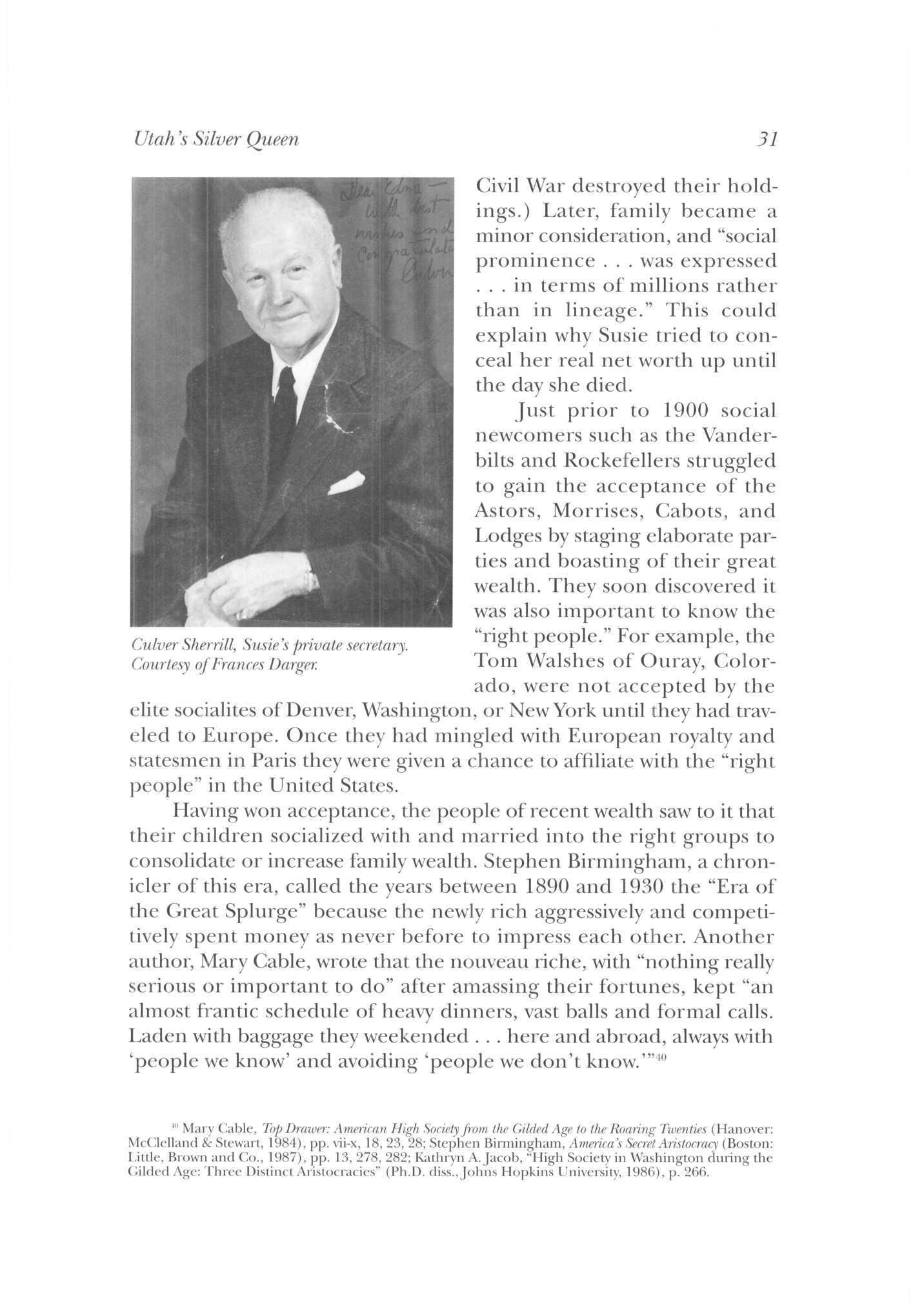

The fifth man to play a major part in Susie's life was her business manager Culver Sherrill, a little man with dyed red hair and a moustache. Some have suggested that he was her last lover, but others believe that unlikely. He was interested in someone else at that time. In her will Susie fondly described him as her closest friend. He tirelessly cared for her and her business interests. He made all their travel

26 Utah Historical Quarterly

Prince Nicholas V. Engalitcheff, Susie'sfourth husband. Courtesy of Susanna Hartman and Raye Ringholz.

34 Hartman interviews; Salt Lake Tribune, January 29, 1933; Pasadena Star, February 5, 1933; Salt Lake Tribune, October 20, 1933; "Prince Weds 'Silver Queen' Second Time," unidentified newspaper clipping courtesy of Dr. Lamb; Ringholz to author; Hartman interviews; Culver Sherrill, Crimes without Punishment (Hicksville, N.Y: Exposition Press, 1977), p 68; telephone interview with Angelo Boncaraglio, Culver Sherrill's companion, Taormina, Sicily, summer 1994

arrangements and packed for both of them. When she died in 1942 he was a fifty-year-old bachelor.

Toward the end of her life Susie gave Sherrill the legal authority to sell her property Some members of her family became alarmed when he began selling many of her properties and stocks in the 1930s. He did not account to anyone except Susie for the money. A few relatives and Culver's companion suggested she may have become senile because her behavior seemed unwise and unpredictable

After the sale of El Roble Susie preferred living in hotels. When she returned to Utah in 1938 to check on her mines, she arrived in the Denver 8c Rio Grande's Pullman suite and checked into a suite of rooms in the Hotel Utah for the summer Many years had passed since her last visit, and she was greeted like royalty by the press and public. She told reporters she would not tour Europe again. At age seventynine she was tired of traveling and wanted to settle down Susie died on August 4, 1942, at the age of eighty-three. She had recently moved from her Plaza Hotel suite in New York to the less expensive Hotel Wendell near Pittsfield, Massachusetts The day she died she was on her way to visit a friend in Virginia and had stopped at the Putnam Inn for the night. That evening she and some friends had planned to attend a party. When she failed to meet them, one of them went up to her room and found her lifeless body lying on the bed with a sleeping mask over her eyes. 35

Throughout the years Susie had many close relationships with her servants. Mary, the head maid in Amelia's Palace, always referred to her as "madam," and other members of the staff also respected and admired her because she treated them well and never chastised them publicly. If necessary she was not above cleaning her own bathroom. When food needed additional seasoning, she typically jumped up from the table and salted it herself instead of reproving the cook A Pasadena home tour script noted that Susie's servants at El Roble were also very loyal and devoted to her. After she left California she maintained a close relationship with J E Feldman and his wife Letitia Feldman had served as El Roble's gardener for several years and lived on the estate with his family. He was also one of her witnesses in the 1918 trial against Wallace Bransford.

In light of these close relationships with her employees, it is easy to

Utah's Silver Queen 27

35 Salt Lake Tribune, May 12, 1938; Hartman interviews; "'Silver Queen' of Utah Closes Famed Career," Park Record, August 6, 1942; all of the obituary notices in Utah newspapers were essentially the same; Hartman and Lamb interviews; Boncaraglio interview

understand why she left her estate to two members of her staff. Her will directed the executor to setup a $4,000 trust fund for Feldman and hiswife. They were to receive $100 a month for life, as a small token for their devotion andloyalty. Culver Sherrill received therest ofher estate and personal property, including several stocks. In 1939, three years before herdeath, Susiehad given him the Richmond Apartments—later renamed the Sherrill Apartments—in Salt Lake City.

Some of Susie's relatives, surprised to find they were not mentioned in herwill, wanted to challenge it, believing shewas mentally incompetent prior to her death. Her magnificent jewelry wasnot part of her estate, and they were further surprised when the executor announced that most of her money was gone. Nellie asked Sherrill for her mother's jewelry—which Susie hadinherited at Sara's death—but he told her itwas also gone. It is hard to explain whySusie chose to leave her relatives nothing, although some of them had been openly critical of her or were cool or indifferent toward her. Sherewrote herwill in 1939, revoking any previous wills that mayhave included them. In this final will she reminded her relatives that shehad been very generous to them during herlifetime andfelt that was enough.36

Even in her grave Susie has remained the subject of speculation by historians andothers, with onewriter suggesting that herdeath was

28 Utah Historical Quarterly

Even in her mature years the Silver Queen projected an image of beauty and style. USHS collections.

36 Hartman and Lamb interviews; Susanna B Engalitcheff's Will, #24672, pp 1, 2, 5, in probate records, Utah State Archives; Pasadena Home Tour Notes; "Florist Testifies in Will Contest," Salt Lake Tribune, October 22, 1918; Engalitcheff probate records; Ringholz to author.

the result of foul play or suicide. There is insufficient evidence to support either premise, but both are worthy of discussion because it is important to dispel the false rumors this theory spawned. The notion of suicide or foul play probably developed because Susie sent Nellie a strange letter a few weeks before she died She complained of being afraid but did not explain why Since that time people have wondered why Susie wrote such a letter but did not ask for help.

The suicide theory is plausible in light of Susie's financial problems After her death several newspapers reported that she had only $65,000 left of her many millions. By 1942 nearly all of her stocks were worthless. The Silver King Mine had paid few dividends during the depression When the estate was probated in Utah and California, it was discovered that she actually owed Utah's Continental Bank $22,000 and had pledged her remaining stocks against the debt. A NewYork appraiser estimated the value of her clothes, remainingjewelry, and cash on hand at $250 when she died. Susie probably had to sell El Roble and herjewelry to support herself during the depression as she was nearing bankruptcy

The California probate hearing also revealed that she had been ill shortly before she died. Unfortunately, neither Utah nor California probate records provide any details of her illness. Despite her failing health and financial woes, those family members who admired her most feel that suicide was not her style and would never have been an option. As for the note to Nellie, it is risky to try to explain her motive for sending it Many older people frequently worry about their health and money.

The foul play theory should also be dismissed; it has no factual foundation It developed because of her sudden and medically unattended death—not in itself a suspicious circumstance. The death certificate lists arteriosclerosis as the cause of death. Sherrill deserves praise for faithfully watching over Susie in her old age. Unfortunately, his boastful statements after Susie's funeral made her heirs suspicious of him. In 1943 he told some reporters in California that he had inherited $4,000,000, whereas a few months earlier he had told Susie's relatives that she had died almost penniless It is highly probable that Susie gave Sherrill some of the money andjewelry in question so that probate would not be a source of contention among her relatives and friends after her death She also may have given Adele and Dawn some of her jewelry because they played an important role in her later life. Furthermore, Susanna Hartman and Harold Lamb,Jr., Susie's niece

Utah 's Silver Queen 29

and great-nephew, have stated that any gifts Sherrill may have received he deserved for his years of faithful service.37

Sherrill also unconsciously fueled suspicion when he built or leased a villa in Taormina, Sicily, with a staff of six servants. Some wondered how he could afford to live in luxury if Susie's fortune was as depleted as he had claimed. Some relatives were still upset that Susie had given him the Richmond (Sherrill) Apartments and felt the building rightfully belonged to the family. A few years after Susie's death he sold these apartments to the Mormon church for $1,800 a month. During a thirtyyear period the Mormon church paid him over $650,000.38

Susie's burial expenses were paid by her estate, not by her family as some have reported Sherrill took care of the arrangements personally. After seeing Susie dressed to perfection in furs and jewels in life, her niece Susanna Hartman was disappointed when she later saw her in the coffin. The dress was too plain and her hair and makeup did not look right. Susie's funeral was held at the Evans and Early Mortuary at 4:00 P.M on Saturday, August 8, 1942 She was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery next to her first husband, Albion Emery. Hartman chose a headstone some twelve inches square and three inches high and simply had the initials S.B.E. carved on it. With the large stone Bransford-Emery marker, the small stone seemed adequate.39

In the process of sorting the myths from the facts about Susie's life, it is important to put her in historical context. Rather than comparing her to the average Utah woman of her time, with whom she had little in common, it makes more sense to view her among her wealthy associates in Washington and New York. The "old guard" made it difficult for the newly rich to infiltrate their exclusive social circles. To belong, Susie had to play by the rules. Originally, as the New York Herald pointed out, lineage was a prerequisite for membership (The Bransford family had been prominent in the South before the

37 Ringholz, Diggings and Doings, p 64; Lamb interviews; "Estate Left by Princess Set at $65,918," Salt Lake Tribune,Junei, 1943; Engalitcheff probate records from Utah and Los Angeles, California; death certificate of Susanna B. Engalitcheff, Vital Statistics Department, Hartford, Connecticut; Hartman interviews; "'Silver Queen' Wills Millions to Manager of Estate," Salt Lake tribune, August 26, 1942

58 Murray interviews; interview with Gene Kellogg, nephew of Culver Sherrill; interviews with Frances Darger, niece of Susie's Salt Lake City lawyer, Frank Johnson; interview with Merna Hansen, LDS Real Estate Department A title search at the Salt Lake County Recorder's Office revealed that Culver Sherrill received the property from Susie on January 31, 1939 The Mormon church purchased the property on February 25, 1950, for $60 a day for the remainder of Sherrill's life This amounted to more than $650,000 by the time of his death in 1981 The church also paid all of Culver's taxes on this income

39 Engalitcheff probate records; "Rites Planned Saturday for 'Silver Queen,'" Salt Lake Tribune, August 6, 1942; Hartman interviews.

30 Utah Historical Quarterly

Civil Wardestroyed their holdings.) Later, family became a minor consideration, and "social prominence . . . was expressed ... in terms of millions rather than in lineage." This could explain whySusie tried to conceal her real networth up until the day she died

Just prior to 1900 social newcomers such as the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers struggled to gain the acceptance of the Astors, Morrises, Cabots, and Lodges bystaging elaborate parties and boasting of their great wealth. They soon discovered it was also important to know the "right people." Forexample, the Tom Walshes of Ouray, Colorado, were not accepted by the elite socialites ofDenver, Washington, or NewYork until they had traveled to Europe. Once they had mingled with European royalty and statesmen in Paris they were given a chance to affiliate with the "right people" in theUnited States.

Having won acceptance, thepeople ofrecent wealth saw toit that their children socialized with and married into the right groups to consolidate or increase family wealth Stephen Birmingham, a chronicler of this era, called theyears between 1890and 1930the "Era of the Great Splurge" because the newly rich aggressively and competitively spent money as never before to impress each other. Another author, Mary Cable, wrote that thenouveau riche, with "nothing really serious or important to do"after amassing their fortunes, kept "an almost frantic schedule of heavy dinners, vast balls and formal calls. Laden with baggage they weekended . ..here andabroad, always with 'people weknow' andavoiding 'people wedon't know.'"40

Utah's Silver Queen 31

Culver Sherrill, Susie's private secretary. Courtesy of Frances Darger.

"' Mary Cable, Top Drawer: American High Societyfrom the Cilded Age to the Roaring Twenties (Hanover: McClelland & Stewart, 1984), pp vii-x, 18, 23, 28; Stephen Birmingham, America's Secret Aristocracy (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1987), pp 13, 278, 282; Kathryn A.Jacob, "High Society in Washington during the Gilded Age: Three Distinct Aristocracies" (Ph.D diss., Johns Hopkins University, 1986), p 266

It appears that philanthropic activities were not generally undertaken by many prominent people until a later period. As for family life, the wealthy usually sent their children to boarding schools, as did Susie, and often were too busy to spend much time with them even during holidays or summer vacations. Governesses were expected to nurture the children and teach them manners and discipline.

Finally, it is important to remember that Susie had a good sense of humor and was a great storyteller. She may have inadvertently started some of the myths about her life by making flippant comments Some seemingly insensitive statements, such as the one to her friend Jennie Kearns about hanging her four wedding rings like grapes in the bathroom, were probably intended to be humorous or even self-deprecating. In one of her most outrageous comments she is quoted as saying that she regretted the passing of an era "when rich people could live like they wanted to live, could afford to live, without fear of offending the proletariat." Perhaps some historians have taken her remarks too seriously. One thing is fairly certain, as a member of an exclusive group of Americans in the "Era of the Great Splurge," Susie believed she had a public image to maintain She may also have used it as a shield to help preserve her dignity in good and bad times. One comment published immediately after her death seems to reflect the views of many who knew her during her lifetime: "Famed for a remarkable personality as much as for her extreme wealth, the princess was often described as a blend of grand dame, business woman, cosmopolite and breezy westerner, forming a striking and attractive combination."41

Contemporary observers dubbed Susie Utah's Silver Queen, and the title has remained exclusively hers for almost a century To attempt to label her today as either a cold, unfeeling socialite or as a caring and loving daughter, wife, sister, mother, aunt, and friend would distort her life Her actions clearly reveal a complex personality that exhibited many traits, endearing and otherwise. While Utah's "silver kings" and other mining millionaires opened businesses or bought newspapers, railroads, and political influence, Susie's exuberant spirit seemed to soar when a handsome prince, a good time, or preferably both were at hand. Perhaps the most significant thing to remember about Susie is that she, more than any other individual who gained a fortune from Utah's mines, used her wealth to create a highly visible

32 Utah Historical Quarterly

" Florida Too Cold, New York Too Hot and California Too Sad, So Globe Trotting Princess Comes Back Home," Salt Lake Telegram, May 11, 1938; Malmquist, The First One Hundred Years, p. 214; Hartman and Lamb interviews; "Death Comes to Utah's Silver Queen,'" Salt Lake Tribune, August 5, 1942

place for herself in elite social circles in America and Europe. In doing so she exemplified the "Era of the Great Splurge."42

42 The millionaires mentioned are Thomas Kearns and David Keith, Susie's business partners

The following bit of folklore was taken from an interview with Susanna Hartman and two Mount Olivet Cemetery guides, Mary Dawn Coleman and Floralie Millsaps: Legendary in life, Susie is apparently not allowed to rest in peace even now Local folklorists claim that after the funeral some of her friends filled her coffin with silver dollars out of love and respect for her memory The present Evans and Early Mortuary staff insists the story is false, but over the years members of Susie's family have complained that their family headstones have been moved and are not in the right places After her life of adventures, real and fabricated, it somehow seems fitting that Utah's illustrious Silver Queen, who rose from modest circumstances in Park City to riches and lost most of it in the end, might be resting in a coffin filled with silver dollars. A major water line for the cemetery's sprinkler system runs through the middle of the Emery and Bransford graves, making it necessary to move headstones occasionally to replace or work on the water pipes. Humorously, the current sexton at Mount Olivet, Daniel Valdez, is not sure that Susie's body actually rests beneath her headstone and does not want to discuss the story No doubt Susie would be delighted with this amusing situation She loved to leave people guessing

Statement of Ownership, Management, and Circulation

The Utah Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0042-143X) is published quarterly by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101-1182. The editor is MaxJ. Evans and the managing editor is Stanford J. Layton with offices at the same address as the publisher The magazine is owned by the Utah State Historical Society, and no individual or company owns or holds any bonds, mortgages, or other securities of the Society or its magazine

The following figures are the average number of copies of each issue during the preceding twelve months: 3,328 copies printed; 85 dealer and counter sales; 2,915 mail subscriptions; 3,000 total paid circulation; 42 free distribution (including samples) by mail, carrier, or other means; 3,057 total distribution; 271 inventory for office use, leftover, unaccounted, spoiled after printing; total, 3,328

The following figures are the actual number of copies of the single issue published nearest to filing date: 3,241 copies printed; 15 dealer and counter sales; 2,975 mail subscriptions; 2,990 total paid circulation; 31 free distribution (including samples) by mail, carrier, or other means; 3,031 total distribution; 210 inventory for office use, leftover, unaccounted, spoiled after printing; total 3,241.

Utah 5 Silver

33

Queen

Hospitality and Gullibility: A Magician's View of Utah's Mormons

BYDAVID L ZOLMAN, SR

BETWEEN 1869 AND 1912, GEORGE ANTON ZAMLOCH, billing himself as The Great Zamloch, took his magic show on the road throughout the West His itinerary included Hawaii, Nevada, California, Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, Idaho, and Utah An Austrian immigrant based in San Francisco, he was a genial and good-natured man who was quick to praise the hospitality he found in Utah's small towns but equally quick to disdain local superstition, stinginess, and uncouth behavior whenever he encountered it.

Zamloch retired in 1912 and wrote an extensive memoir, still in possession of the family, that has never been published or cited in any of the scholarly literature about the West and Mormons. 1 Based primarily on that memoir, this paper recounts his 1882 tour of Utah's small towns and offers personal reflections on the landladies, innkeepers, bishops, and stage managers whom he re-creates so vividly. The mining towns of Park City and Silver Reef stand in cosmopolitan contrast to conservative farming villages such as St. George, Toquerville, and Centerville The Great Zamloch, an illusionist by trade, had a remarkably brisk way of dispelling social illusions in print, and his sleight of hand became a deft touch in his first-person writing