UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, ManagingEditor

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City, 1997

JANICE P. DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1997

ROBERT S. MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden,1998

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end. Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5V* or VA inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes,standardASCIItextfile.Foradditional information on requirements contact the managing editor.Articles represent the views of the audior and are not necessarilythose of die Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

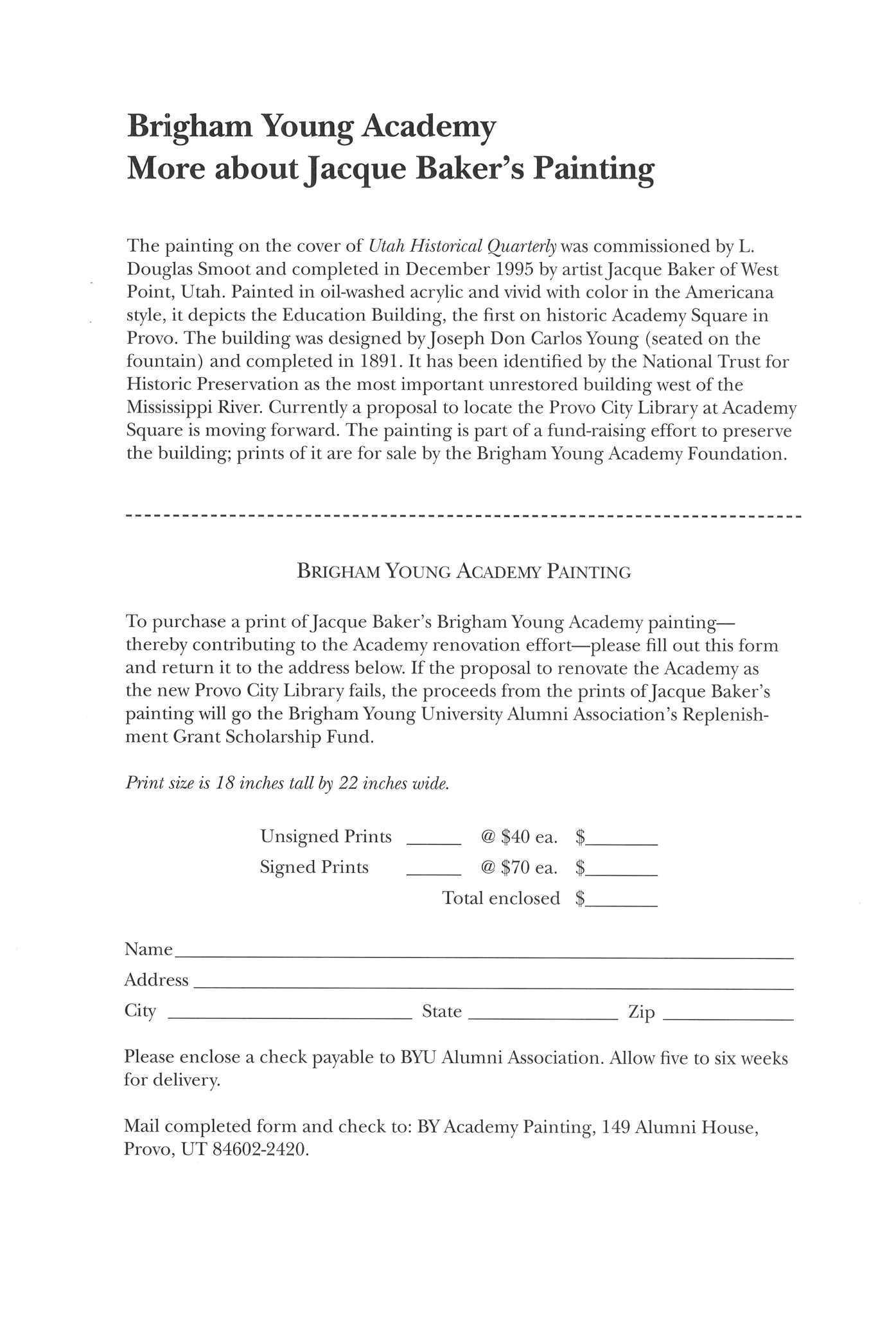

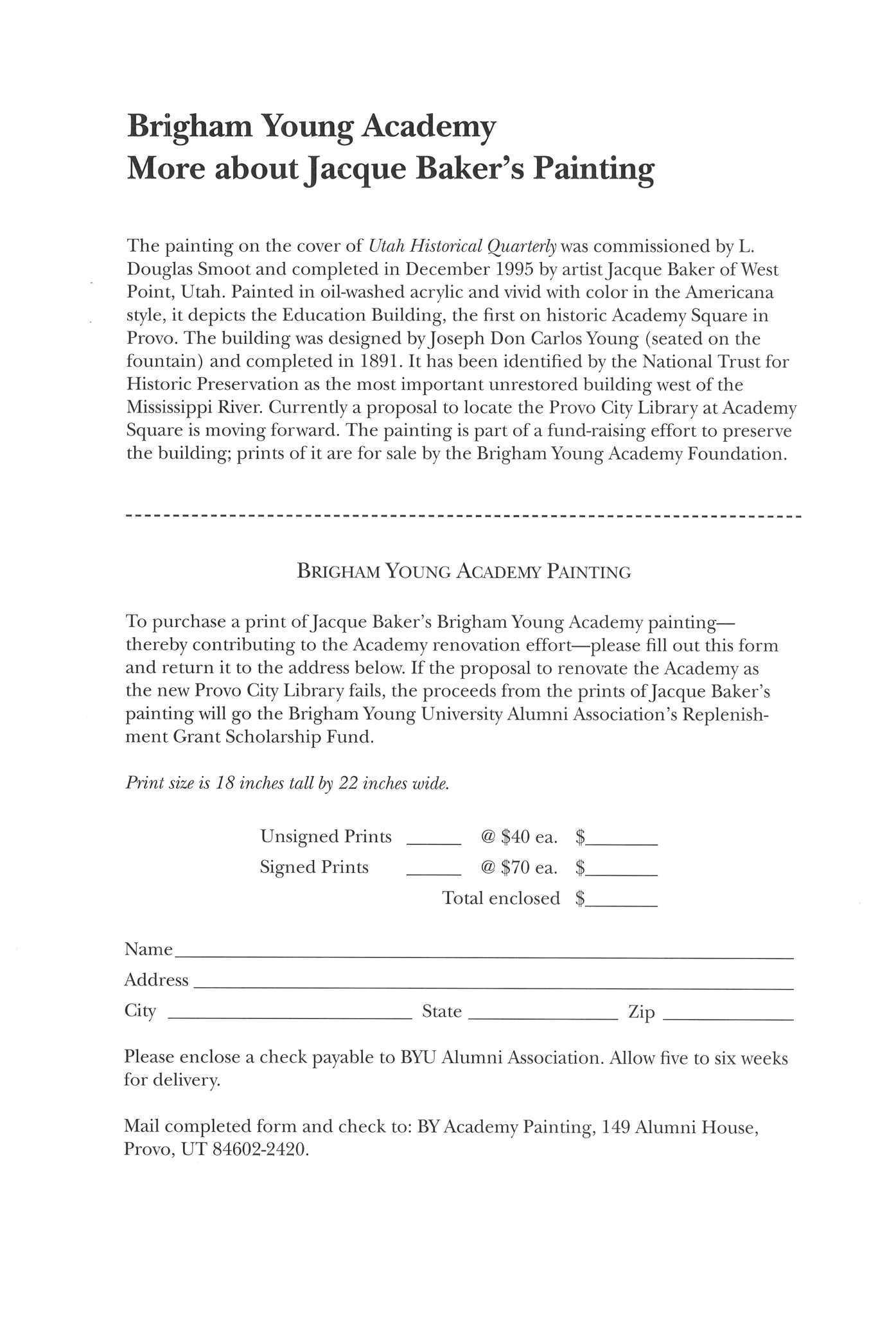

HISTORICA L QUARTERLY Contents SUMMER 1996 \ VOLUME 64 \ NUMBER 3 IN THIS ISSUE 203 GENERAL REGIS DE TROBRIAND, THE MORMONS, AND THE U.S. ARMY AT CAMP DOUGLAS, 1870-71 MARK R. GRANDSTAFF 204 TURNING THE TIDE: THE MOUNTAINEERVS. THE VALLEY TAN ROBERT FLEMING 224 AMERICAN INDIANS AND THE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM: A CASE STUDY OF THE NORTHERN UTES KIM M. GRUENWALD 246 UTAH'S CONSTITUTION: A REFLECTION OF THE TERRITORIAL EXPERIENCE . . . THOMAS G. ALEXANDER 264 BOOKREVIEWS 282 BOOKNOTICES 292 THE COVER The Education Building on Provo 's historic Brigham Young Academy Square was painted by facque Baker and is reproduced through the generosity of the artist. See last page of this issuefor more information. © Copyright 1996 Utah State Historical Society

DANIEL C MCCOOL , ED Watersof Zion: ThePolitics of Water in Utah . . . .MICHAEL E. CHRISTENSEN

J. ELDON DORMAN. Confessionsof a Coal CampDoctorand Other Stories

282

EDWARD A. GEARY 283

BRENT CORCORAN. Park City Underfoot: Self-guided Tours ofHistoric Neighborhoods ELIZABETH EGLESTON 284

MARY LYTHGOE BRADFORD Lowell L. Reunion: Teacher, Counselor, Humanitarian .DOUGLAS D ALDER 286

ANNA JEAN BACKUS. Mountain Meadows Witness: The Life and Times ofBishop Philip Klingensmith . . . .HUG H C. GARNER 287

DAVID WALLACE ADAMS. Education for Extinction: American Indians and theBoarding SchoolExperience, 1875-1928 . . .KIM M. GRUENWALD 289

MELINDA ELLIOTT. Great Excavations: TalesofEarly Southwestern Archaeology, 1888-1939 KEVIN T.JONES 290

Books

reviewed

In this issue

The familiar backdrop of the Mormon-gentile conflict assumes a slightly different look as some relatively unknown personalities take center stage in our first two articles. General Regis de Trobriand was an extraordinary man to begin with. Cosmopolitan and artistic, this French-born sophisticate was an unlikely sort to carry Uncle Sam's banner in the often muddled and treacherous cauldron of nineteenth-century Utah politics, particularly given his distaste for such a role But when he found this responsibility thrust upon him, he responded with a natural confidence and style that earned him

the respect of most principals of the time and of historians since. His story is followed by an analysis of a newspaper war in the territory as the Valley Tan and the Mountaineer exchanged polemics, hyperbole, and unabashed accusations in a wild two-yearjournalistic brawl. Yet, to the benefit of the historical record, that melee shed at least a ray of light on the murky question of personal violence in early territorial Utah.

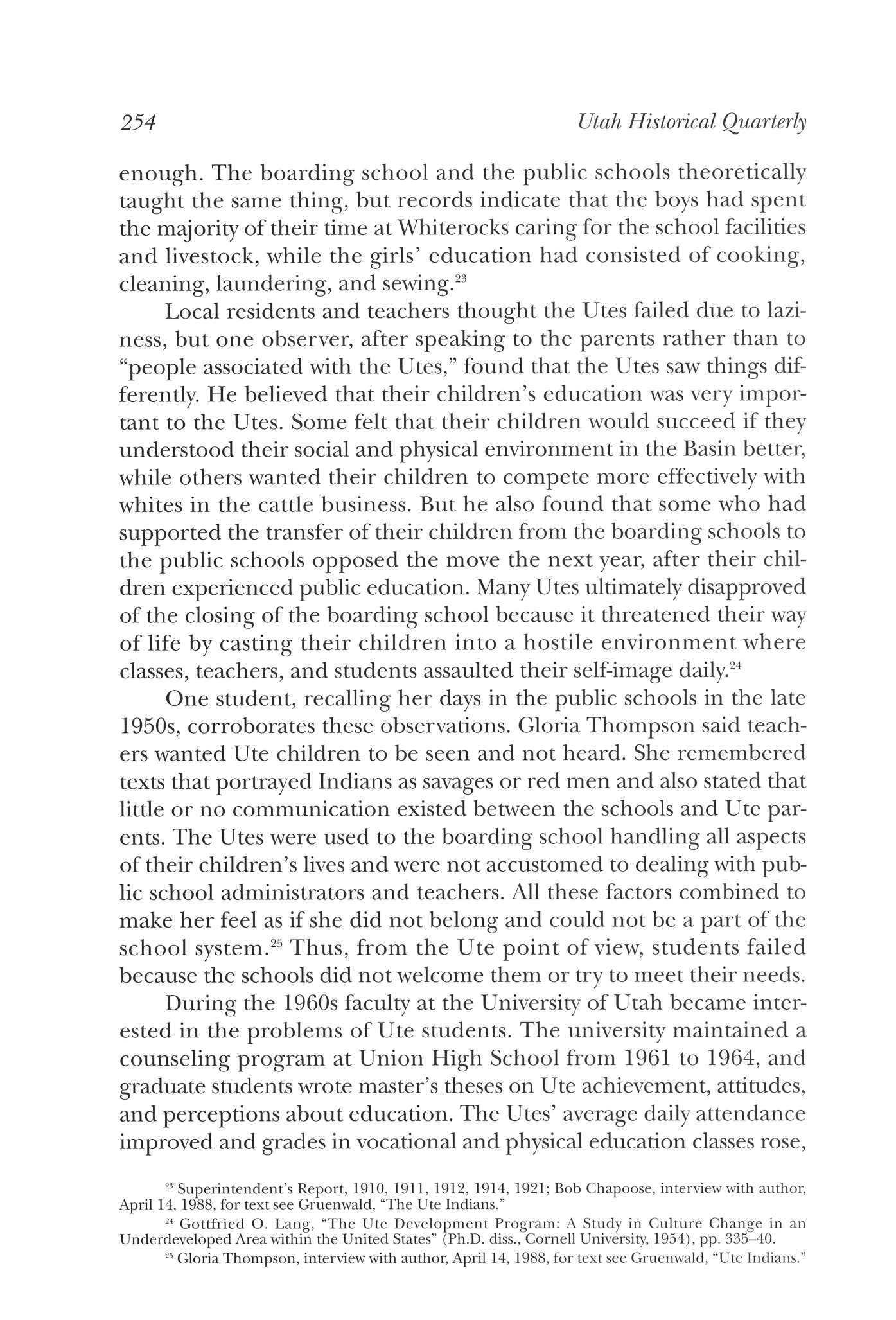

The third article shifts to the twentieth century and conflict of a different type—the clash of cultures in our public school system. Noting that the boarding school experience of Native Americans has been scrutinized over and over again, the author breaks new ground with this bold study of Ute students in Uinta Basin public schools. It is a complex story of federal strategies, local white priorities, and traditional Ute values all seeking accommodation and balance.

The concluding selection continues our year-long emphasis on the centennial as one of Utah's foremost historians examines the interplay of thoughts and events that shaped our state constitution. It will not only command a lasting historiographic niche for its revisionist conclusions but will also serve as the standard reference for anyone seeking to understand territorial development within the context of U.S. constitutional law.

Our colorful front-cover scene of the original Brigham Young Academy in Provo features that wonderful montage of detail and impression that is artist Jacque Baker's hallmark As she bicycles past the historic structure to promote its exciting future, the editors of the Quarterly yell thanks for her thoughtfulness and generosity in letting us share her painting with our readers

General Regis de Trobriand. USES collections.

General Regis de Trobriand, the Mormons, and the U.S. Army at Camp Douglas, 1870-71

BY MARK R GRANDSTAFF

BY MARK R GRANDSTAFF

I N LATE SEPTEMBER 1871 AN IMPORTANT DEBATE took place in the office of Brigham Young. Anticipating being charged and arrested for lewd and lascivious cohabitation with his polygamous wives, the Mormon leader wanted to use the arrest as an opportunity to "meet and fight the opposition in the courtroom." He hoped to demonstrate that the charges against him were a product of persecution and intolerance.

Dr Grandstaff is an assistant professor of history at Brigham Young University where he specializes in U.S military history He wishes to thank Professors Edward M Coffman and Thomas G Alexander for reading and critiquing this article and Dr Roger Launius for supplying several sources

Oil painting of Camp Douglas by General de Trobriand. USHS collections.

ApostleJohn Taylor confronted Young over the possibility of someone assassinating him while incarcerated Having been present when the first Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, was murdered, Taylor wanted to make sure that it did not happen again Young rejected the analogy of 1844 and Carthage Jail but promised Taylor that he would take no unnecessary chances Turning to one of the elders present, Young asked him to take a message to the post commander at Camp Douglas, General Regis de Trobriand. Tell him, Young dictated, that " [I] fully trust the honor of the military for protection [as I] might [soon] be his guest." Later that day de Trobriand sent word back to Young assuring him that if arrested "he would be protected."1

As relations between the Mormons and the army had been problematic, it is a bit surprising to find Young placing his life in the hands of an army officer. But this was no ordinary army officer. Born Philippe Regis Denis Keredern de Trobriand near Tours, France, on June 4, 1816, he was the son and nephew of two French generals. As a child and son of a baron-general, his playmates included the young Due de Bordeaux, later Charles X, the king of France. In 1841 he visited the United States, married the daughter of a prestigious New York City banker, and lived in Europe—painting, writing, and performing opera. 2

After returning to the United States in 1847 and becoming an editor for a leading French-American newspaper, he filed for citizenship shortly after the South fired on Fort Sumter. Tendered a colonelcy in the 55th NewYork Volunteer Regiment in August 1861, he had by 1865 been breveted to the ranks of brigadier and major general and given command of a division in the Army of the Potomac. The only other Frenchman to obtain the rank of major general in the U.S. Army was American Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette.3

The place of de Trobriand in the ranks of postwar regimental commanders is even more remarkable considering that only a third of all regimental commanders were not soldiers prior to the war. Of those, only de Trobriand had been born outside of the United States, become a naturalized citizen, and gone on to a generalship. His friend, General-in-Chief of the Army William T. Sherman, put this accomplishment into perspective: "I was glad, de Trobriand, when you

'Journal History, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, September 26, 1871, microfilm CR 100/137 #28, Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo See also de Trobriand to General Christopher Augur, Department of the Platte, October 1, 1871, de Trobriand Collection, Mormon file, United States Military Academy (hereinafter USMA), West Point, New York

2 Marie Caroline Post, ed., The Life and Memoirs ofComte Regis de Trobriand: Major-General in the Army of the United States (New York: E P Dutton, 1910), p 90

3 Moreover, of all the regular officers born outside the United States and not soldiers prior to the war, he was the highest ranking

GeneraldeTrobriand 205

were one of the chosen; out of six hundred colonels, there were only twenty-five kept for the regular army. You were a brevet major-general becoming a colonel, but, there were full generals who became simple majors and captains."4

Upon being assigned as a regimental commander, de Trobriand served first in the Dakotas and then went to Montana in late 1869 as its military district commander. 5 During this period he began to exhibit those traits that more or less exemplified the collective mentality of the professional army officers of the period. These traits included a dislike of political intrigue, a wariness about the motivations of politicians and self-promoting army officers, a dislike for the army's expanding constabulary role, and the desire to place the needs of the army over personal interests.6 Obviously, some officers exhibited this thinking more than others; some not at all. Nevertheless, this professional mentality combined with de Trobriand's appreciation of foreign cultures and inherent sense of "noblesse oblige" formed a sophisticated framework from which he would judge Utah politicians and the Mormons.

In the spring of 1870, after consulting with Generals Sherman and Philip Sheridan, Brevet Brigadier General Christopher Augur, commander of the Department of the Platte, ordered de Trobriand to headquarter the 13th Infantry at Camp Douglas.7 Described by

4 Post, Memoirs, p. 503.

5 A year after the war he interviewed for a regular officer position and then returned to France to write Quatre Ans de Campagnes a VArmee of the Potomac, published in 1866 One of the first works written by a ranking general about the war, it was translated into English in 1867 and received praise from the likes of Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan (though given Sheridan's dislike of books it is unlikely that he ever read it). While writing the work he received a letter from the War Department tendering him a regular commission and a colonelcy in the 31st Infantry

By the time de Trobriand returned to the U.S. in 1867 regimental headquarters had been set up at Fort Stevenson in the Dakotas, a fairly quiet assignment that introduced him to the vicissitudes of frontier life During his two years there he found time to paint, learn the Sioux dialect, and maintain ajournal of Indian culture In 1868 he penned a portrait of Sitting Bull and finished his most famous work, Military Life in the Dakotas—still a standard for the scholar of the Old Army See Post, Memoirs, pp 364-66 In 1869, when the Army was forced to reduce to twenty-five regiments of infantry, the 31st was consolidated with the 22nd Infantry under the command of David S Stanley, and Sheridan, the new commander of the Missouri, gave de Trobriand command of the 13th. Given Sherman's and Sheridan's high regard for his abilities and integrity, perhaps it was no arbitrarily made decision that de Trobriand received the 13th Infantry Sherman was its first regimental commander during the war and Sheridan one of its first captains For an excellent analysis of de Trobriand's relationships with civilians, other military officers, and the Piegans in Montana, see Paul A Hutton, Phil Sheridan and His Army (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985), pp 180-99

6 The best works analyzing this mentalite are William B Skelton, An American Profession of Arms: The Army Officer Corps, 1784-1861 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1992), especially chaps 13, 15, 16; and Edward M Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784-1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), chap. 5. See also Robert Utley, Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 (New York: Macmillan, 1973); and Robert Wooster, The Military and United States Indian Policy, 1865-1903 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988).

7 Between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century the army divided the country into the Atlantic, Missouri, and Pacific divisions Most troops in the Atlantic served in the Departments of the East and South and performed duties unrelated to Indian affairs and frontier life The Missouri and

206 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Sheridan as "an American consulate in a foreign city," Camp Douglas had been established on October 26, 1862, by Colonel Patrick E Connor on the bench immediately above Salt Lake City to both protect the overland mail route and "keep watch over the Mormons." 8 In June 1869 part of the 7th Infantry, under the command of Colonel John Gibbon, took charge of the camp from the 18th Infantry.9

On June 11, 1870, de Trobriand,

Pacific divisions dealt closely with Indian affairs and sought to make the frontier safe for establishing white communities The Missouri was the largest division, encompassing most of the troops and the largest geographic area (the states of Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas, Indian Territory, and the territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Utah)

In August 1866 Missouri was further divided into three departments: Arkansas, Dakota, and the Platte The Department of the Platte encompassed Iowa, Nebraska and Utah territories, and parts of Wyoming and Montana

In 1870 the department contained fourteen posts with 3,951 troops, or an average of 282 soldiers per post. Sheridan was the Missouri Division commander, and Augur became the Platte's commander in November 1867 See Richard Guentzel, "The Department of the Platte and Western Settlement, 1866-1877," Nebraska History 56 (Fall 1975): 389-417; and Arthur P Wade, "The Military Command Structure, 1853-1891," Journal of the West 15 (July 1976): 5-21

Augur, the Platte's commander, attended West Point with Ulysses S Grant from 1839 to 1843, participated in the Mexican War, and earned much praise from Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan for his management abilities during the Civil War. Efficient, apolitical, and a complex thinker, he handled tough problems discreetiy, which endeared him to his superiors While others sought promotion and popularity, Augur pursued the goals of the army and his superiors See Hutton, Phil Sheridan and His Army, p 122, and Ezra J Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1964), p 12

8 As quoted in Guentzel, "The Department of the Platte," p 406 Although the official orders did not direct the Army to "watch over the Mormons," it was certainly implied, and Connor believed it to be an important part of his mission See Lyman C Pedersen, Jr., "History of Fort Douglas, Utah" (Ph.D diss., Brigham Young University, 1967), a useful but dated work; Charles G Hibbard, "Fort Douglas, 1862-1916: Pivotal Link on the Western Frontier" (Ph.D diss., University of Utah, 1980); Leonard J Arrington and Thomas G Alexander, "The U.S Army Overlooks Salt Lake Valley: Fort Douglas, 1862-1965," Utah Historical Quarterly 33 (1965): 326-50; and Brigham D. Madsen, Glory Hunter: A Biography ofPatrick Edward Connor (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990)

9 Gibbon, another successful Civil War general, found work among the Mormons—including bailing his troops out of Salt Lake Cityjails—tedious and distasteful He objected to the city police entering the military reservation to apprehend disorderly soldiers Army General Orders strictly prohibited civilian authorities from entering government lands without the authorization of the post commander He also disliked the duty of feeding indigent former Mormons who in consequence of "not agreeing with the Church they [were] cutoff from all work, and are unable to support their families" (July 21, 1869). See, for instance, Post Record Book, Camp Douglas, entries dated July 21, 1869, January 30, 1870, February 20, 23, 1870, microfilm A1340, Utah State Historical Society (hereinafter USHS), Salt Lake City

Generalde Trobriand 207

Philippe Regis de Trobriand. USES collections.

along with Companies A, F, I, and K, began their arduous 556-mile march from Fort Shaw, Montana, to Corinne, Utah, where the railroad would take them the additional 72 miles to Salt Lake City. The trek took about 40 days as soldiers marched from 4 A.M to noon, covering between 12 and 18 miles per day.10 Other companies of the regiment marched off to their new stations, while Gibbon and the 7th Infantry moved from Utah and Wyoming to Montana to relieve the 13th Infantry.

Upon assuming command of the post on July 15, de Trobriand found himself in a position to forge the 13th Infantry into an effective fighting force. Unlike the Civil War, when regiments remained together, the nature of the frontier mission dictated that companies break off from the main regiments to garrison various forts and camps. In 1870 alone the 13th had companies dispersed throughout Wyoming and Utah.11 But as of July 1870 about half of the regiment was with de Trobriand at Camp Douglas.12 This provided opportunities for the officers and men to get to know each other and drill as a unit, for this was the first time that a significant part of the regiment had been assigned to one post.13

De Trobriand's immediate concerns centered on establishing a daily routine and enforcing discipline. The day after he assumed command, the daily schedule was posted: reveille at 5 A.M.; work details, marksmanship practice, and drilling throughout the day; and taps at 9 P.M.14

Discipline in the frontier army was harsh and at times could be brutal. For a small infraction, such as missing muster or not carrying out duties properly, the penalty was often extra duty.15 With no civilian custodians to keep the camp clean, it was up to the soldiers to maintain it in good repair These punishments often provided up to 10 percent of the enlisted force for such extra duty. More serious infractions, such as desertion, fighting, and insubordination, usually demanded incarceration for several months, a loss of pay, and hard physical

10 U. G. McAlexander, History of the Thirteenth United States Infantry (Fort McDowell, Calif.: Regimental Press, 1905), pp 72-73

11 Ibid

12 Ibid., p. 74. According to the July 1870 Post Returns, Companies C and E arrived on June 25, and de Trobriand and regimental staff and band, along with Companies J and K arrived on July 15 After C and K departed for Provo on the 28th, the strength at Camp Douglas as ofJuly 31 was 11 officers and 104 enlisted men

n McAlexander, History of the Thirteenth, pp 73-74

14 General Order 31, July 18, 1870, Post Record Book, RG 393, Part V, Entry 10, Vol 2 of 15, Camp Douglas, Utah, Military Branch (MB), National Archives (NA), Washington, D.C

15 Coffman, The Old Army, pp. 198-99, 372-73; Darlis A. Miller, The Frontier Army in the Far West, 1860-1900 (St. Louis: Forum Press, 1979), p. 11.

208 UtahHistorical Quarterly

labor.16 When a captain under his command was too lenient in his sentence of a private who verbally insulted a sergeant, de Trobriand reprimanded the officer and told him to reconsider the sentence. The action of the private, he felt, was "a gross violation which, if not properly repressed" would demoralize the regiment.17

Besides focusing on cultivating regimental cohesion, de Trobriand began building new barracks and recreational facilities. In a letter to the department's adjutant general, he enclosed estimates to build family quarters for officers and to replace a rear building of the camp's hospital. He justified such requests on the basis of better efficiency and morale.18 He was also particularly concerned about the education of the enlisted men's children and requested a new school for them Although the War Department turned down his request for a school, the barracks were finally approved and constructed in the late 1870s De Trobriand would make sure that enlisted men had a billiard table, a reading room, and a place to stage theatricals.19

Some of his more immediate concerns also centered on his own quarters, as someone had taken the wardrobe and extension table that Gibbon had left Writing to the post quartermaster, de Trobriand's aide made sure that the young captain got the message: "As they [the wardrobe and table] belong to his quarters, the Brevet Brigadier General directs that you ascertain what has become of those articles." The table and wardrobe were shortly returned.20 But the quartermaster was not out of hot water yet When de Trobriand saw a civilian employee passing "leisurely" by, using an army horse on his way to Salt Lake City, he had his aide write another note to the captain: "The Brevet Brigadier General Commanding directs me to call for an explanation of this apparent violation of orders."21 He received the report in short order with a promise that it would not happen again.

Despite problems with the quartermaster, de Trobriand probably considered himself fortunate to have such a seasoned group of officers serving under his command Of the 33 officers in the 13th Infantry, 17 (52 percent) had served in the Civil War. Although in

16 Coffman, The Old Army, pp. 373-74; Miller, The Frontier Army, p. 11. A deserter in time of war could be executed Other punishments included confinement for several years, rations of bread and water, and dismissal from the service

17 De Trobriand to Captain A S Hough, October 21, 1870, Post Letter Book, USHS

18 Post Record Book, August 4, 1870, USHS

19 Circular dated August 8, 1871, RG 393 Part V, Entry 10, Vol 2 of 15, Fort Douglas, Utah, Special Orders, NA

20 Post Record Book, July 30, 1870, USHS

21 Post Adjutant to Post Quartermaster, July 30, 1870, in ibid

GeneraldeTrobriand 209

1870 only 3 of these officers were above the rank of major, during the war 8 had been field grade officers or higher, including 2 at the rank of brevet major general, 1 brevet brigadier general, and 3 brevet colonels. None of these senior officers had been in the army before the war, however, all having made their rank as volunteers. They were reduced in rank when tendered a regular commission after the war. 22 It was a bitter pill for many. For example, Brevet Major General Henry A. Morrow, a member of the famous Irish Brigade during the Civil War and now a lieutenant colonel, could not give up the belief that he was destined for future command.23 Self-promoting and over-confident of his military ability, Morrow was often at odds with de Trobriand over War Department policy and departmental orders. De Trobriand saw him as "an able politician" who sought his own advancement at the sake of duty.24 Fortunately, per War Department policy, as the second highest ranking officer Morrow commanded a 13th Infantry regimental garrison at Fort Steele, Wyoming, some two-hundred-plus miles from Salt Lake City.

De Trobriand was to clash with more than one former high-ranking Civil War "politician/officer." Seven months prior to the 13th Infantry's entrance into the Salt Lake Valley, President Ulysses S. Grant, the former commanding general of the Union armies, adopted a "gettough" policy toward the Mormons and appointed former Brevet Brigadier GeneralJohn Wilson Shaffer to the post of Utah's territorial governor. 25 Shaffer, a former chief of staff to General Benjamin Butler, "the Beast of New Orleans," learned firsthand what an occupying force of federal officials could do to bring a people into subjugation.26 In a style more characteristic of a military dictator than a diplomat or politi-

22 The Official Army Registerfor January, 1870 (Washington, D.C: Adjutant General's Office, 1870), pp 134—36 Brevet ranks were given for gallantry, much as a medal is given today A regular officer's official rank was determined by his ascent up the military hierarchy based on date of rank (seniority). One could be a regular captain and a brevet brigadier general, but one would only receive the rights and duties of a captain The brevet and the stories surrounding gallantry were often reserved for discussions at the officers' mess. Approximately 1,700 Civil War officers were breveted major general or brigadier general See Mark Boatner, The Civil War Dictionary (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), p 84

23 For an important insight into Morrow's aspirations see his Civil War diary: "To Chancellorsville with the Iron Brigade," Civil War Times Illustrated 14 (January 1976): 12-22; and "The Last of the Iron Brigade," ibid (February 1976): 10-21

24 See, for instance, de Trobriand to Territorial Governor George Woods, December 15, 1871, de Trobriand Collection, Utah file, USMA I am grateful to Roger D Launius for generously sharing this letter with me.

25 Gustive O Larson, The Americanization of Utah for Statehood (San Marino, Calif: Huntington Library, 1971), pp 72-73 Regarding Shaffer's appointment see Jack E Eblen, The First and Second United States Empires: Governors and Territorial Government, 1784-1912 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1968), p 274 Shaffer had important friends in the Grant administration, including Vice-president Schuyler Colfax; the chaplain of the Senate, Joh n P Newman; and Secretary of War Joh n Rawlins

26 For Shaffer's war record see War Department, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C: GPO, 1880-1901), 15:694—695

210 UtahHistorical Quarterly

cian, Shaffer challenged the Mormon leadership to acknowledge his authority. "Never after me, by God," the bellicose former general allegedly said, "shall it be said that Brigham Young is governor of Utah."27

In a move to exercise his authority, on September 15, 1870, Shaffer suspended the annual musters of the militia and replaced its leader, Lieutenant General Daniel H. Wells, a counselor to Brigham Young in the LDS church and the mayor of Salt Lake City, with Patrick E Connor.28 Although the Mormons

27 As quoted in Robert Dwyer, The Gentile Comes to Utah: A Study in Religious and Social Conflict (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1971), p. 66; and Larson, The Americanization, pp 72-/3 When General Nathan P Banks relieved Butler of command in 1862, he chided Shaffer for his exaggerated estimates of enemy forces and military supplies Banks disliked the number of government entities he found there—a military government, a state government, an independent pro-Southern judiciary, and an informal government consisting of revenue and custom officials Moreover, the army had been reduced to a posse comitatus placed at the whim of whomever wielded power at the time. Perhaps determined not to make the mistakes that Butler had in Louisiana, Shaffer sought to impose strict enforcement of federal laws in Utah and hoped to take a strong hold of legislative matters See War of the Rebellion Records, 15: 694-695

28 p roc l ama tion s of Governor Shaffer, September 15, 1870, Utah Territorial Executive Papers, microfilm A-704, 3424-3426, USHS; Dwyer, The Gentile, pp 69-71; and Thomas G Alexander and James B Allen, Mormons and Gentiles: A History of Salt Lake City (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing, 1984), p 93

Upon arriving in Salt Lake City in March, Shaffer found that the governor had little power The office, he complained, "was a mere sinecure a mockery It is hard to be nominally Gov in Utah Brigham Young is permitted to exercise the power of law giver and autocrat of the territory." He described the Territorial Legislature as "composed of Young's most subservient instruments ready always to do the bidding of the Prophet." See Shaffer to Cullom, April 27, 1870, State Department MSS, Utah, No. 686, NA.

The Mormon theocracy was not the only problem Federal territorial policies were ill-defined, and territorial officers rarely received support from their parent federal agency, the State Department To a very real extent the territories, not the federal government, defined federal-territorial relations Governors repeatedly called for precise instructions or policy statements, only to be told to reread the Organic Act of their territory Governors received no training and were not adequately apprised of federal policies or their duties The State Department provided general guidelines and hoped that the governors would make good decisions. See Eblen, The First and Second United States Empires, pp. 301-2.

When Shaffer pleaded with Secretary of State Hamilton Fish to allow him to choose probate judges and empower the Utah district courts to empanel their own juries, Fish made it clear that he was not prepared to interpose federal authority: "Some of the attributes of these courts are unusual and anomalous, but it is to be observed. . . . that under our principles of administration, every intendment is to be made in favor of the local Legislature, and in restriction (if need be) of the residuary power which Congress may have retained." Fish to Shaffer, August 2, 1870, State Department MSS, Utah, II, No. 709, NA. Shaffer undoubtedly marveled at Fish's antiquated states' rights approach to territorial problems involving the theocracy of the Mormons More important, the governor recognized that if he was going to clean this "Augean Stable" as he promised Grant in July, it would be without the help of other federal agencies and in the wake of his wife's recent death and his own poor health See Shaffer to Grant, July 7, 1870, State Department MSS, Utah, II, No 703, NA

Generalde Trobriand 211

John Wilson Shaffer. USES collections.

protested Wells's removal, Shaffer based his authority to remove the general on the Organic Act of 1850 which specified the governor as the commander-in-chief of the militia.29 Later in November, a group of Mormon militia officers, in what has become known as the Wooden Gun Rebellion, defied Shaffer's order, were arrested, and in turn released by a Mormon grand jury that refused to indict them.30

What made the militia particularly threatening to federal officials was that it was made up almost exclusively of Mormons. Known as the Nauvoo Legion, it had been created by the Mormons during their stay in Illinois and had been led by Wells for over thirty years. By 1870 the militia rolls totaled about 6,000 men, most of them armed, drilled, and equipped.31 The army at Camp Douglas numbered three companies (234 soldiers as of October 1870).32 Mustering such a body of citizen-soldiers that comprised the Nauvoo Legion demonstrated who had the real power in Utah

In the midst of the struggle between Shaffer and the Nauvoo Legion, an event between regulars stationed at Camp Rawlins and citizens in Provo further strained the relationship between federal officials, the Mormons, and the army Camp Rawlins had been established in April 1870 at the request of Shaffer and with the concurrence of Sheridan and Augur. Located three miles northwest of Provo on the Timpanogos (now Provo) River and named after Shaffer's friend, Secretary of War John Rawlins, Camp Rawlins's primary purpose, although not specifically stated, was to enforce antipolygamy laws. Manned by two companies (C and K) of the 13th Infantry under the command of Captain (Brevet Major) Nathaniel Osborne, the officers and men had arrived in Provo from Montana in late July 1870.33

For the better of two months the army and Provo citizens had little contact with each other. But on the night of September 22 that changed dramatically Enlisted men who had contracted with a local citizen to use his home for a dinner party became intoxicated and

29 Dwyer, The Gentile, pp 70-71 When Wells signed a letter to Shaffer as the "Lieutenant-General of the militia of Utah Territory," Shaffer replied that the only lieutenant-general he recognized was Philip H Sheridan. See Deseret Evening News, October 29, 1870.

30 Alexander and Allen, Mormons and Gentiles, pp. 93-94

31 Joh n K Mahon, History of the Militia and the National Guard (New York: MacMillan, 1969), p 115

32 Report of the Secretary of War: 1870 (Washington D.C : GPO, 1870), pp 72-73 Camp Douglas strength stood at 11 officers and 223 enlisted men These figures included 3 officers and 81 men of the 2d Cavalry

33 The best work on the Rawlins incident is Stanford J Layton, "Fort Rawlins, Utah: A Question of Mission and Means" Utah Historical Quarterly 42 (1974): 68-83 In 1875 Osborne was transferred to the 15th Infantry and promoted to major. See Army Register, 1876, p. 140. See also Dwyer, The Gentile, pp. 71-72; and Orson F Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1893), pp 506-19

212 UtahHistorical Quarterly

wandered Provo's streets looking for those Mormons who had failed to keep their promise of supplying a dance hall and some female companionship. LDS Bishop William Miller, a city alderman, was marched down West Main Street at bayonet point and eventually released after proving that he had not promised such accommodations. Nevertheless, for the next two hours gun were fired, citizens harassed, and several buildings damaged.34

Cited in the SaltLakeHerald the next day as the "Provo Outrage," it appeared to some that Shaffer's prohibition of the militia deliberately left the Mormons without a means to protect themselves from the whims of the federal government and its disorderly constabulary force.35 Hoping to avoid a confrontation with the Mormons, the governor sought to turn the "outrage" into an opportunity for solidifying Mormon opinion in his favor. Shaffer's inept handling of the affair, however, placed a wedge between him and the post commander at Camp Douglas. On September 27, 1870, he wrote a letter to de Trobriand chastising the general for not submitting a report to him personally and insisting that the soldiers be "delivered up to the civil authorities . . . that I may see that they are properly tried, and if convicted, punished." Citing his "high regard" for the Mormons, he challenged de Trobriand to remove the army from Utah, "if the United States soldiery cannot fulfill the high object they were sent here for. . . ."36 Adding insult to injury, the letter was not sent to Camp Douglas but published in the Salt Lake City newspapers Shaffer miscalculated de Trobriand's reaction. The general's dislike of politicians and political rhetoric only added fuel to his indignation at being publicly challenged by the territorial governor. Unfortunately for Shaffer, he had struck the first blow with a choice of weapons that was very familiar to de Trobriand—pen and paper. The general's reply was published two days later in the DeseretEvening News/'7 His first thrust was aimed at Shaffer's admitted weakness—a knowledge of territorial law and peacetime military protocol De Trobriand made it clear that the military had no duty toward the ter-

34 "The Provo Outrage," Salt Lake Herald, September 27, 1870; Layton, "Fort Rawlins," pp 69-70

36 "More Concerning the Proclamations," Salt Lake Herald, September 23, 1870; Layton, "Fort Rawlins," p 71; Dwyer, The Gentile, pp 71-72; Pedersen, "History of Fort Douglas," pp 213-16; Hibbard, "Fort Douglas," p 125

36 "The Provo Outrages," Deseret Evening News, September 27, 1870; "Governor Shaffer Writes," Salt Lake Herald, September 27, 1870; Dwyer, The Gentile, pp 71-72 See also Post, Memoirs, pp 425-29

37 "Letter," Deseret Evening News, September 30, 1870; "Heavy on Governor Shaffer," Salt Lake Herald, October 1, 1870

GeneraldeTrobriand 213

ritorial governor other than providing him assistance should Shaffer apply for it through the correct channels.

De Trobriand also made it quite clear that although Shaffer had done nothing about the event until September 29, he had been in Provo since the 25th trying to ascertain the facts and punish the guilty.38 Regarding Shaffer's comment about removing the army from Utah, the general made his disdain for politicians and his opinion about using the army for constabulary duty in Utah manifest The reason why the army was sent to Provo in the first place, de Trobriand pointed out, was the desire of Shaffer and his friends to force their position on the Mormons. If the governor would like the military to leave, de Trobriand said, then

By all means Sir, if you wish it You know by this that we of the Army are not of a meddling temper, we are no politicians, we don't belong to any ring; we have no interest in any clique, and we don't share in any spoils. Our personal ambition is generally limited to the honest and patriotic performance of our duties Wherever we are ordered to go, we go, but we have no choice in the matter, and if we are sent to Provo or anywhere else, it is . . . generally in compliance with the demand of the Governor. To be let alone!! Why, Sir the military itself does not wish any better.39

Moreover, de Trobriand continued, "if the presence of U.S Soldiery interferes in any way with the harmonious workings of your 'happy family' [we will let] you alone to the full enjoyment of that popularity which sojustly distinguishes your administration and surrounds your person in this Territory of Utah."40 Sherman, who was visiting Camp Douglas during the first week of October, was aware of de Trobriand's relationship with the territorial governor, and given his feelings toward politicians and the army's constabulary role, undoubtedly agreed with the Frenchman's analysis of the army's apolitical nature.41 Shaffer died suddenly a month later (October 31), evidently never finding the courage to reply.42

38 Deseret Evening News, September 20, 1870; See also de Trobriand's report to Augur, dated October 1, 1870, Post Record Book, microfilm A1340, USHS Unknown to Shaffer, Mayor A O Smoot of Provo had telegraphed de Trobriand the day after the debacle and asked for his assistance. Since Camp Rawlins was not unde r his command , de Trobriand immediately contacted General Augur in Omah a and requested direction On the 24th Augur directed de Trobriand to go to Provo Arriving on the 25th, he immediately began taking depositions and formulating his report. In fairness to Shaffer, who had lost his wife in July and was deathly ill himself, it is surprising that he found the strength to take any action at all

39 Post, Memoirs, p 428

40 Ibid

11 "General Sherman Visits," Deseret Evening News, October 3, 4, 1870 Sherman's approval of de Trobriand's action and letter is found in Post, Memoirs, p 429

42 Dwyer, The Gentile, p 71; Whitney, History of Utah, p 523

214 UtahHistorical Quarterly

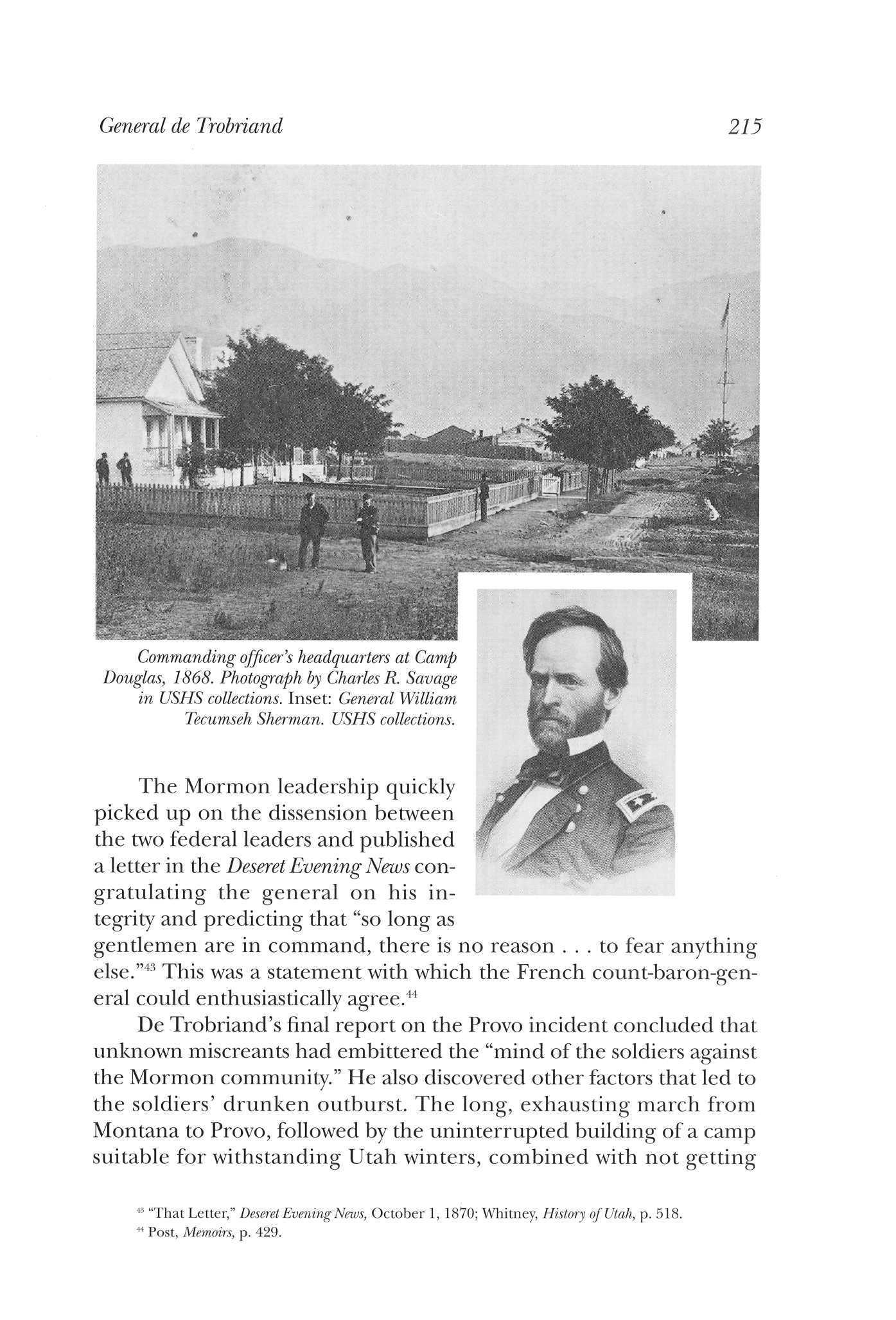

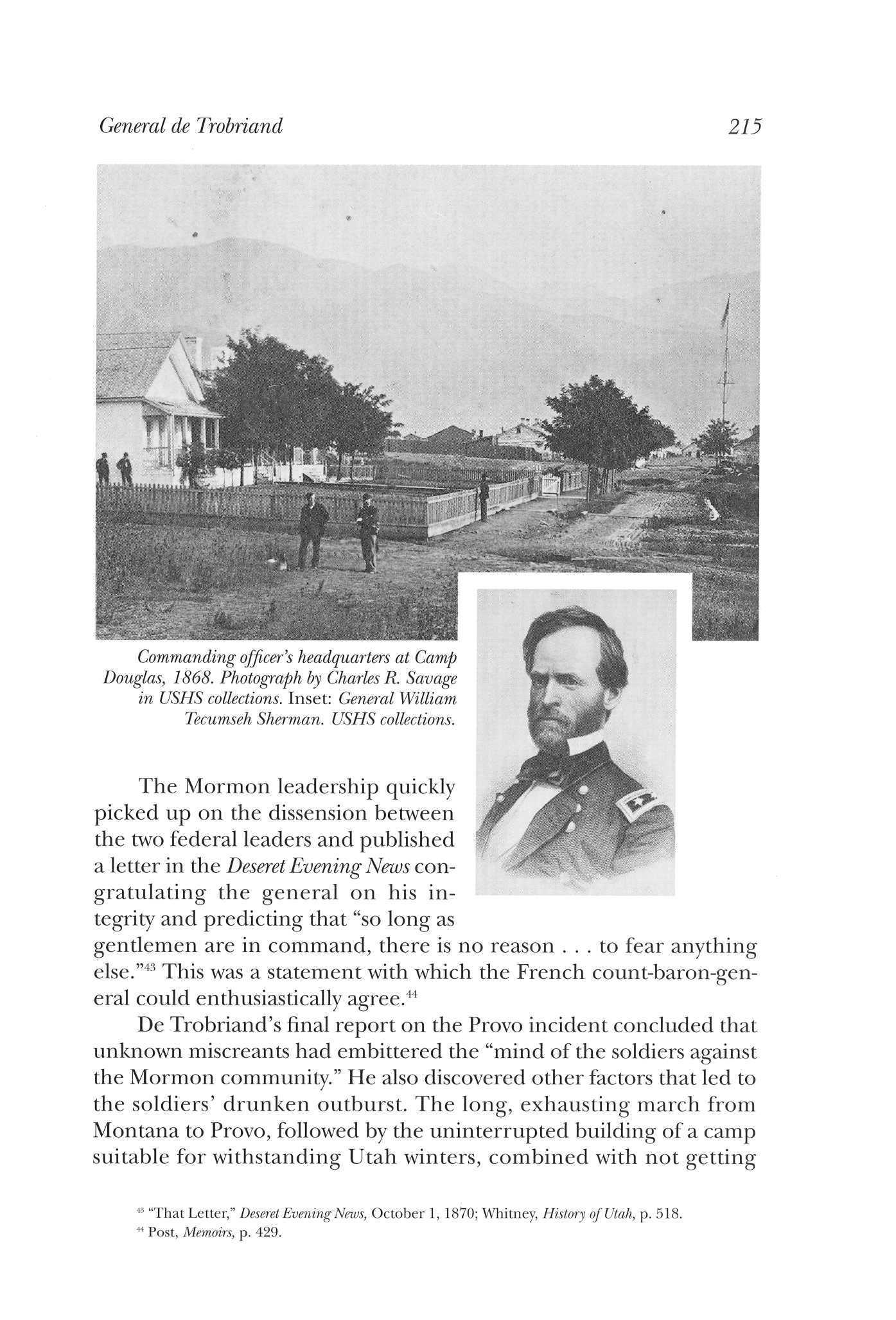

The Mormon leadership quickly picked up on the dissension between the two federal leaders and published a letter in the DeseretEvening News congratulating the general on his integrity and predicting that "so long as gentlemen are in command, there is no reason ... to fear anything else."43 This was a statement with which the French count-baron-general could enthusiastically agree. 44

De Trobriand's final report on the Provo incident concluded that unknown miscreants had embittered the "mind of the soldiers against the Mormon community." He also discovered other factors that led to the soldiers' drunken outburst. The long, exhausting march from Montana to Provo, followed by the uninterrupted building of a camp suitable for withstanding Utah winters, combined with not getting

Generalde Trobriand 215

Commanding officer's headquarters at Camp Douglas, 1868. Photograph by Charles R. Savage in USES collections. Inset: General William Tecumseh Sherman. USES collections.

"That Letter," Deseret Evening News, October 1, 1870; Whitney, History of Utah, p 518 Post, Memoirs, p. 429.

paid for two months, would have been enough to put the men in a surly mood After spending the last two years in Montana, where the soldiers were accepted both for their prowess against the Indians and for their spending money, they resented "the exclusivity of the Mormon community" (which meant no whiskey or female companionship). That resentment fueled the tensions that exploded in a drunken spree two days after payday.45

Yet, such events were common in the army, as frontier conditions combined with irregular pay periods led to drunkenness and desertion. Moreover, the high desertion rate in the army (over one-third deserted in 1871 alone) spoke of low pay, poor conditions, and the quality of the enlisted soldiers. Although the New York Sun exaggerated when it charged that the enlisted ranks of the regular army were composed of "bummers, loafers, and foreign paupers," it was well known, as Sherman put it, that you could not expect to enlist a man with "all the cardinal virtues for $13.00 per month."46 In October 1870, after de Trobriand's investigation, the stockade at Camp Douglas held 19 enlisted men in detention, a 280 percent increase over the preceding month (12 of the 19 were from Camp Rawlins).47

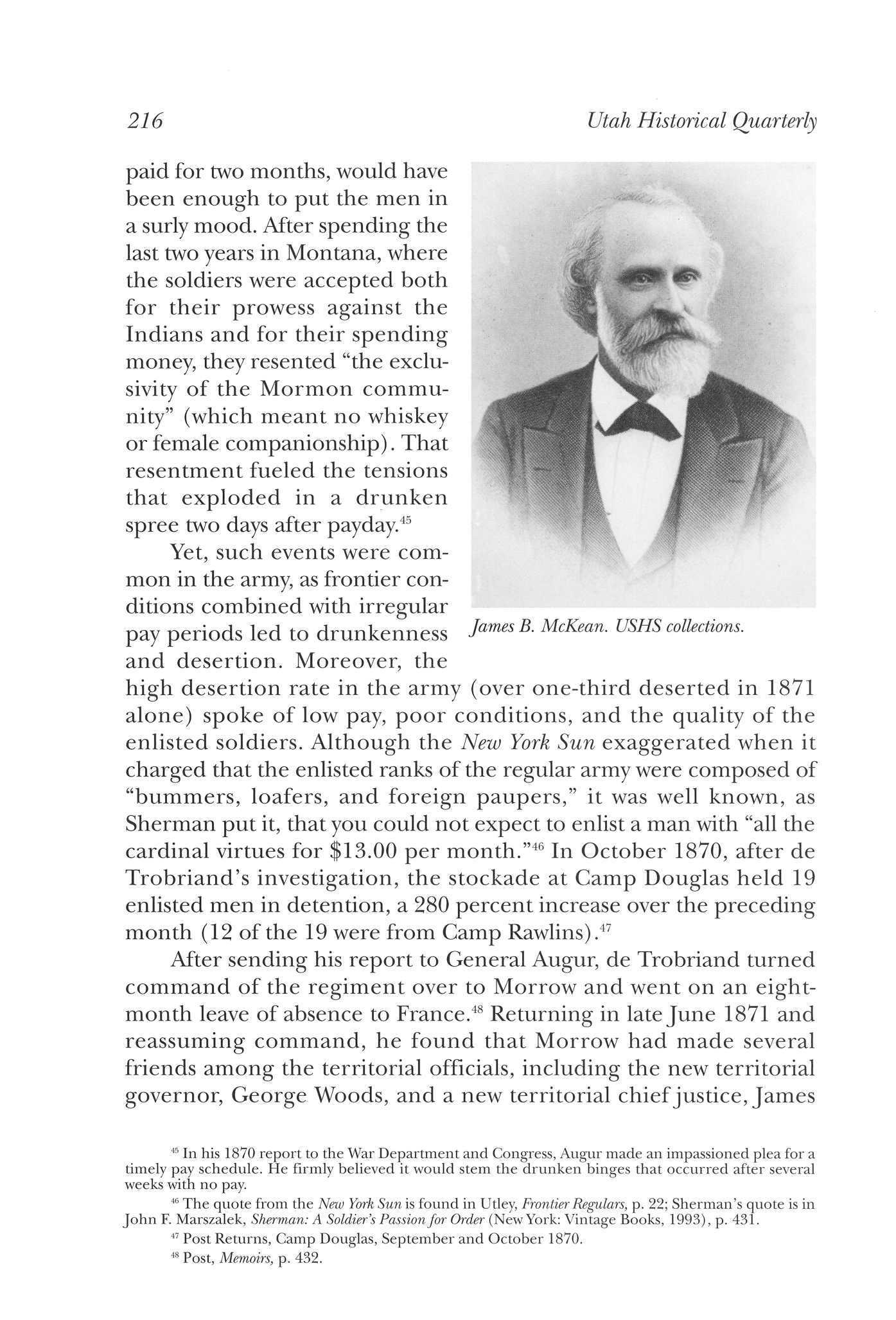

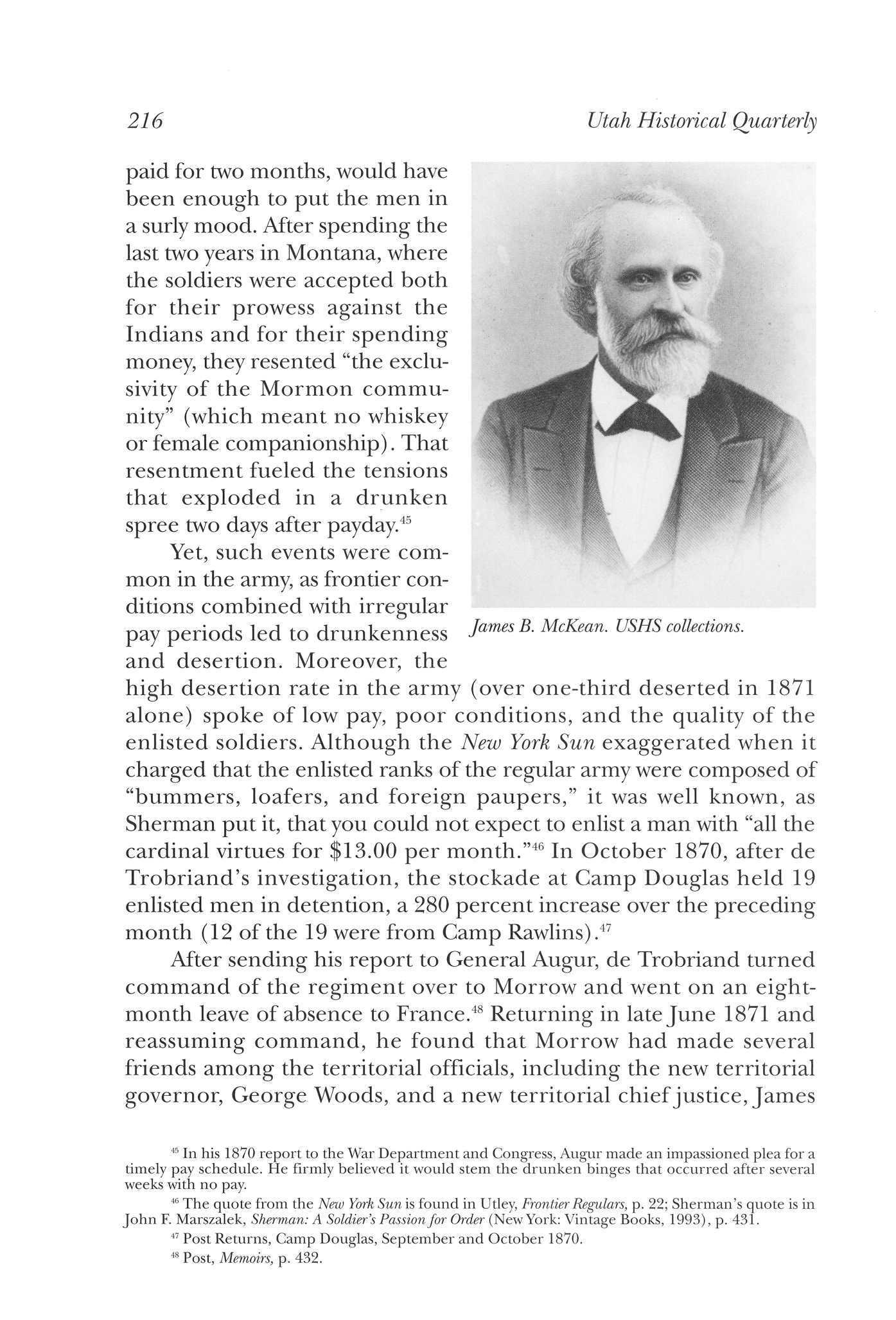

After sending his report to General Augur, de Trobriand turned command of the regiment over to Morrow and went on an eightmonth leave of absence to France.48 Returning in late June 1871 and reassuming command, he found that Morrow had made several friends among the territorial officials, including the new territorial governor, George Woods, and a new territorial chief justice, James

45

46

47

216 UtahHistorical Quarterly

James B. McKean. USHS collections.

In his 1870 report to the War Department and Congress, Augur made an impassioned plea for a timely pay schedule He firmly believed it would stem the drunken binges that occurred after several weeks with no pay.

The quote from the New York Sun is found in Utley, Frontier Regulars, p 22; Sherman's quote is in Joh n F Marszalek, Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), p 431

Post Returns, Camp Douglas, September and October 1870.

48 Post, Memoirs, p 432

McKean.49 Although Morrow returned to his command at Fort Steele in Wyoming, many federal officials took notice of how well they had worked as "a unit."50

Indeed, McKean and Woods had written General Augur in March (four months before de Trobriand returned from France), requesting that Morrow remain in charge at Camp Douglas.51 McKean's letter to Augur recalled de Trobriand's attitude toward Shaffer, pointing out that the Frenchman had "made himself very obnoxious, even offensive, to the friends of the Government in this City Intentionally or not, he caused the disloyal leaders of this peculiar people to believe that his sympathies were with them and against us; and he gave us too much reason to think so, too."52 Within days of receiving McKean's letter, Augur wrote to Sherman, advising him that the federal "officials at Salt Lake object very seriously to de Trobriand." Recognizing that de Trobriand was not the "discreet" officer needed at Camp Douglas, Augur predicted, "if he returns to command there, I am certain of no end of trouble."53 De Trobriand quicklyjustified Augur's prediction.

The issue again centered on Brigham Young's power over the Mormons and the Nauvoo Legion. Woods, the former governor of Oregon and a former justice of the Idaho Supreme Court, made it clear soon after arriving in Salt Lake City that he disliked Young's influence in Utah as much as had Shaffer.54 When the city council appointed a joint Mormon and conservative gentile committee to plan aJuly 4 celebration that included units of the Nauvoo Legion marching in the parade, Woods's administration balked Acting in the governor's absence (but presumably with his permission), Territorial Secretary George Black issued a proclamation reaffirming Shaffer's previous proclamation that the militia could not muster, drill, or parade.55

Black also summoned de Trobriand and insisted that the army back up his edict with force.56 De Trobriand, like other high ranking

49 De Trobriand to William T. Sherman, July 15, 1871, in Post, Memoirs, pp. 435-36.

50 Dwyer, The Gentile, p 72

61 Ibid., pp. 72-73.

52 McKean to Augur, March 8, 1871, in Dwyer, The Gentile, pp. 73.

53 Augur to Sherman, March 13, 1871, in ibid., pp 72-73 On March 18, 1871, Sherman responded to Augur, telling him that he had submitted the letter and report about the Camp Rawlins incident to Secretary of War William Belknap and hoped that Belknap and the president would see the problem in Utah as a sham and that the issues there would "die away." Letter in C C Augur Papers, Illinois State Historical Library, Springfield

54 When asked to meet Young, Woods replied, "the lowest subordinate in the United States ranks higher than any ecclesiastic on earth." See Hubert H. Bancroft, History of Utah (San Francisco, 1889), p. 662.

55 Ibid.; Whitney, History of Utah, 2: 531-33.

86 Bancroft, History of Utah, pp 662-63; See also Ralph Hansen, "Administrative History of the Nauvoo Legion in Utah" (M.A thesis, Brigham Young University, 1954), pp 129-30

GeneraldeTrobriand 217

army officers, disliked using troops as a territorial governor's posse comitatus or domestic peacekeeping force.57 Such roles often placed politicians in a position to put their plans into action at the expense of the electorate and the reputation of the army. Despite his aversion to the role, de Trobriand dutifully channeled the acting governor's request to General Augur at Omaha It was not long until he received a telegram directly from the secretary of war ordering him to forbid the Nauvoo Legion from participating in the parade, and if necessary, to use force in preventing it.58

As an army officer de Trobriand understood why the secretary of war and local federal officials had forbidden the Mormon militia to participate in the parade; as in the Reconstructed South, a local militia only meant further resistance to federal authority.59 Nevertheless, like his officer counterparts in the South, he was suspicious of the "carpetbag politicians" who were apparently using their positions and the army to promote their own aspirations and self-interests.60 Seemingly convinced in his own mind that a "civil war" could break out if the Mormons resisted, he affirmed to Black that soldiers from the 13th Infantry would be ready to execute his prohibition on July 4; but should the militia march, de Trobriand would only give the command to "present arms," leaving it to Black, as the actinggovernor to give the command to "fire."61 This put Black and other federal officials in a precarious position. Firing on the Mormons in response to Black's order would place the responsibility for instigating a war directly on him, not the army. De Trobriand taught Black an important lesson in American civil-military relations that day: civilian authority over the military means that federal or state officials determine when force becomes an extension of politics.62

Yet, even as Black and the so-called anti-Mormon ring were

57 Most officers would probably agree with an opinion found in the November 25, 1871 (p 236) edition of the Army and Navy Journal that the army would prefer to have "its range of duties or employments removed as far as possible from all risk of collision with civil affairs." See Coffman, The Old Army, pp 246-49; Utley, Frontier Regulars, chap 16; Skelton, An American Profession of Arms, pp 300-301 See also Robert W Coakley, The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders (Washington D.C : Center of Military History, 1988), chaps. 5 and 10. Nevertheless, some officers did support a role for the army as a domestic peacekeeper in order to expand the army; see Jerry M Cooper, The Army and Civil Disorder: Federal Military Intervention in Labor Disputes, 1877-1900 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1980), pp 215-17 Two important articles are David E Engdahl, "Soldiers, Riots, and Revolution: The Law and History of Military Troops in Civil Disorders," Iowa Law Review 57 (October 1971): 1-73; and Engdahl, "The New Civil Disturbance Regulations: The Threat of Military Intervention," Indiana Law Journal 49 (1973-74): 581-617

38 Post, Memoirs, p 424

59 Ibid

60 Ibid., p 425

61 Whitney, History of Utah, 2:533.

62 A paraphrase of Carl Von Clausewitz, On War (New York: Viking Penguin, 1968), p 119

218 UtahHistorical Quarterly

deliberating the implications of firing on the Mormons, de Trobriand prepared his troops for what was to come. On the evening of July 3 de Trobriand ordered the 13th Infantry into Salt Lake City. Refusing to ride personally at the head of only a fraction of his regiment, he placed Major A. S. Hough in command. Hough wrote, "With all the gaiety and politeness of his nation, he put me in command, and expressing his doubts as to whether he should ever see us again, fervently hoped that I might have a pleasant day while waiting on the hot streets of Salt Lake for some overt act on the part of the Mormon military."63 Once in the city, troops were issued forty rounds and placed at intervals along the parade route, where they waited at "stacked arms" for the parade to begin the next morning. 6 4

But de Trobriand was not entirely absent. As the soldiers marched into the city, he became "a self-invited guest" at the Mormon prophet's midday meal. When Young and some of his associates argued that they "had a right to honor the national holiday" by parading their militia, de Trobriand stopped them in mid-sentence. "Gentleman," de Trobriand warned, "I am not here to argue or discuss the questions with you. I have orders to obey, and I will obey them; you have seen my preparations, if your militia, under arms, parades tomorrow, I pitch-in."65 Young, not at a loss for words, assured de Trobriand that the Nauvoo Legion could easily destroy the 13th Infantry. If that was to happen, came de Trobriand's cheerful reply, "[it] would not inconvenience the United States in the least, but would ensure the prompt and thorough destruction of Mormonism."66

During the parade the next day no militia marched. Rather the soldiers of the 13th Infantry were greeted by a procession of young girls dressed in white and crowned with flowers. De Trobriand, in his memoirs, wrote that he appreciated the cleverness of Brigham Young on this occasion.67 Later, after finding out about the general's "lunch" with Young, his officers and men applauded his uncompromising firmness with both the Mormons and the politicians Although it seemed that the Mormons admired the Frenchman for his devotion to duty, the politicians continued to question his devotion to their causes. 68 In a way de Trobriand's particular devotion to duty placed

63 Hough as quoted in McAlexander, History of the Thirteenth, pp 74—75

64 Post, Memoirs, p 424

65 Ibid

66 McAlexander, History of the Thirteenth, pp 74-75

67 Post, Memoirs, p 425

68 Not all questioned his devotion to the federal cause See Justice Cyrus M Hawley to Augur, July 5, 1871, which praises de Trobriand's noble performanc e as "he came promptly at the call of the

Generalde Trobriand 219

him in the esteem of his "enemies" and the disdain of his "friends." By early October, actions surrounding the arrest of Brigham Young convinced the politicians that de Trobriand must be replaced

At the center of the controversy was Utah's Chief Justice James McKean who, like de Trobriand, had commanded a regiment of New York volunteers during the war but who now sought to challenge the entire Mormon hierarchy in order to uphold "federal authority over polygamic theocracy."69 Approaching the point of fanaticism, he wrote to his friend Louis Dent, President Grant's brother-in-law, that "the mission that God has called me to perform in Utah" put him above the law—if local or federal laws stood in the way of striking down Mormonism, "by God's blessing I will trample them under my feet."70 McKean naturally targeted Brigham Young as the major symbol of Mormon power Under the authority of the Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862, McKean charged Young with lewd and lascivious cohabitation and

Governor, and all is well." Copy in the de Trobriand Collection, Mormon file, USMA De Trobriand also wrote Sherman about the July 4th incident and of the "praise" he received from Woods and other officials See de Trobriand to Sherman, July 15, 1871, in Post, Memoirs, p 435

59 The best account of this incident is Thomas G Alexander, "Federal Authority versus Polygamic Theocracy: James B McKean and the Mormons," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 1 (Autumn 1966): 85-100; See also Larson, The Americanization, pp 73-75; and Stephen Cresswell, "The U.S Department of Justice in Utah Territory, 1870-1890," Utah Historical Quarterly 53 (1985): 204-22

70 Edward W Tullidge, The Life of Brigham Young (New York, 1876), pp 420-21

220 UtahHistorical Quarterly

George L. Woods. USHS collections.

Brig. Gen. Christopher C. Augur. National Archives.

adultery for living with his polygamous wives, which charge once again pitted the power of the Mormons against that of the federal government. Would Young willingly submit to arrest and arraignment? Telegrams and letters to General Augur from federal officials as well as to de Trobriand demonstrate the intense atmosphere surrounding Young's possible arrest.71

Federal officials apparently believed that the Mormons were on the verge of rebellion and desperately wanted the army to protect them. Governor Woods, either out of distrust or pique—or both— went over de Trobriand's head and telegraphed Augur on September 29, 1871, asking for reinforcements The following day Augur telegraphed de Trobriand telling him that he had ordered two companies from Fort Steele and one from Fort Bridger to reinforce Camp Douglas (bringing the total up to nine companies or 428 soldiers).72 De Trobriand, once again caught between adversaries, again did his duty—in his own manner. He responded to Augur the next day, suggesting that, should there be an outbreak by the Mormons, "under orders or encouragements of the high dignitaries of their Church, there is no doubt that my position here with two hundred men, would be . . . ineffective against thousands of armed religious fanatics ready to lay down their lives as at the beckoning of those they consider as prophets, apostles, and delegates of God."73 Having received Young's word on the matter, de Trobriand was convinced that the Mormons would not rebel He concluded his telegram by welcoming the additional companies but added that he was confident that they would not be needed as no difficulty was contemplated.74

And he was right. Young submitted to federal authorities on October 2 and was placed under house arrest. Daniel H. Wells was arrested the same day and spent a night incarcerated at Camp Douglas, but he was released on $50,000 bail the next day Eventually, McKean's judicial errors caused the cases to be dismissed.75

During these dramatic proceedings it became obvious to Governor Woods and other territorial officials that de Trobriand did not help the government's cause of subduing the Mormons. Indeed,

71 See telegrams dated September 22, 23, 26, 30, and October 1, 1871, in Camp Douglas, Post Record Book, USHS.

72 Augur to de Trobriand, September 30, 1871, Camp Douglas, Post Record Book, USHS The strength of Companies B, C, D, E, F, H, and J of the 13th Infantry and Company D of the 2d Cavalry totalled 20 officers and 408 enlisted men

73 De Trobriand to Ruggles (adjutant general, Department of the Platte), October 1, 1871, 2, in de Trobriand Collection, Mormon file, USMA.

74 Ibid.

75 Alexander, "Federal Authority," pp 91-93

GeneraldeTrobriand 221

on three separate occasions—in the incident at Camp Rawlins, during the Fourth of July parade, and now with the arrest of Young—he appeared to subvert the wishes of the government and ingratiate himself with Brigham Young and the Mormons. The fact that Young had requested de Trobriand to arrest and protect him under guard at Camp Douglas seemed to solidify their belief that the Frenchman was helping to foster Mormon dissent. This belief was exacerbated by these events and provoked Woods and Justice McKean to importune President Grant and Secretary of War Belknap to replace de Trobriand and send more troops.76

On October 15, 1871, de Trobriand received a telegram from President Grant ordering him to move his headquarters to Fort Steele and placing Lieutenant Colonel Henry Morrow in charge of Camp Douglas. "I am beaten by local politicians of Salt Lake City," he would write William T. Sherman in December, "as the order was not initiated by any of my military commanders, but issued by the President of the United States under pressure of some political influence." Citing discussions between Salt Lake City officials and some of his 13th Infantry officers, de Trobriand explained that his "only fault was to be too much of a gentleman and a soldier, and not enough of a politician."

"General de Trobriand is not one of us," the officials told the army officers, because

he did not associate with our people here he did not shake hands or take a drink with the boys but patronized the Cooperative Store and visited Brigham Young What we want here is not so much a fine gentleman and a soldier as a politician to pull through with us. Now you see Morrow was in politics all his life, and it sticks to him in his military career. He understands our people, gets acquainted with everybody . . . will take a drink with any of us, and makes himself generally popular.77

In a separate communication to De Trobriand, Grant corroborated the officials' reasoning by making it clear that he was not being replaced for military reasons but because the situation called for an officer who was both a "lawyer and politician."78 Since Morrow was both and sought promotion, de Trobriand mistakenly concluded that he had conspired with Salt Lake City officials to remove him from the command of Camp Douglas.

76 Woods to U. S. Grant, October 2, 1871, Philip Sheridan Collection, Roll 18, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

77 De Trobriand to Sherman, November 1, 1871, Sherman Papers, Roll 17, Library of Congress.

78 According to a Washington insider, "McKean and the other vultures [at Salt Lake] created such a furor that the Secretary of War, William Belknap convinced Grant to make the change." See Charles F Benjamin, Commissioners of Claim, to de Trobriand, January 18, 1872, de Trobriand collection, Mormon file, USMA

222 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Evidence suggests that Morrow had nothing to do with de Trobriand's removal. Upon being ordered to Salt Lake City, Morrow would write three letters to de Trobriand protesting his new assignment Having just lost his daughter, Morrow pleaded with de Trobriand to not blame him for the change in regimental headquarters, as he desired to stay at Fort Steele and attend to his affairs Moreover, as Morrow "fully concurred" with all that the Frenchman had done "in the recent troubles in Utah," he could not see what else he could do. Morrow even telegraphed the adjutant general of the department, telling him that he did not want the job at Camp Douglas as de Trobriand had the full confidence of the U.S. officers and should not be relieved.79 Despite Morrow's efforts, de Trobriand's dislike of politician-soldiers and his belief that the removal was politically motivated caused him to damn Morrow as a co-conspirator with the "vultures and scalawags" of Salt Lake City.80 Indeed, he would never overcome his wariness of politicians or "political-minded" officers.81

After his move to Fort Steele, de Trobriand continued as commander of the 13th Infantry, and he took another leave of absence to visit France in 1872. Soon after his return, Sheridan requested that de Trobriand and the 13th Infantry be placed under his command in Louisiana for Reconstruction duty.82 In 1879, de Trobriand retired from the army and lived out his life traveling between New Orleans, New York, and France, reading, writing, and painting.83

In January 1889Junius Wells wrote de Trobriand, thanking him for the hospitality extended to his father when a prisoner at Fort Douglas. "That occasion has never been forgotten," Wells wrote, "by those who were treated as his guests rather than prisoners." Wells enclosed a steel engraving of Brigham Young with the hope that the general's time in Salt Lake would be remembered fondly. De Trobriand replied, wishing Wells the best and hoping that there would come a time when religious and political differences would be settled.84 Living to see Utah become a state, General de Trobriand died at Bayport, Long Island, onJuly 15, 1897, at the age of eighty-one—a successor to Lafayette, a man of the world, and a friend to the Mormons

79 Morrow to de Trobriand, October 14, 18, 19, 1871, de Trobriand collection, Mormon file, USMA

80 Benjamin to de Trobriand, 18 January 1872.

81 J T McGinniss to de Trobriand, November 22, 1871, de Trobriand collection, Mormon file, USMA

82 The 13th Infantry arrived in New Orleans in October 1873 Hutton, Phil Sheridan, pp 265-66; Post, Memoirs, pp. 443-46.

83 Post, Memoirs, p 522

84 Junius F Wells to Regis de Trobriand, January 31, 1889; and de Trobriand to Wells, February 9, 1889, in Post, Memoirs, pp 430-33

GeneraldeTrobriand 223

THE MOUNTAINEER.

NO. 1.

TIB IIIITUII

EVERY SATURDAY.

GREAT SALT LAKE CITY, SATURDAY, AUGUST. 27, 1859. VOL. I

AUNT MAQWIRE'S ACCOUNT OF , been Ion- shawls The frocks an 1 petTHrJ MISSION TO MUITLETE- '"-'oats '^'.V J f ;c :l aion S a a 'i""' 1 iT.c«orT, r^,<.w„UTT"r PE» atw.t l<-'» vcar-s I .-aw a notk-e i-i ilic j'Go-pod Trumpet'—I'd left WiggleI'VE Ion very lonesome lituly Jcf-' !?"" a "'" ~

ELAIK FEUOL'SOX & STOUT [^^S^^^^ ^ twZ^i'n^oA^lhZ'^'''^''

TIl.MS: &6 per J»mim in idvance ™1™'lis; but thin- cumlorts nic: bol s ( [ "'= h £ cy*aU

ADVERTISING

• when he comes hack 1 guc-s Hi! be "" ' lor good He's about made up Ins ™' ' l "''!"

•mind to scale down here, and c.civ- P "1" M o !

) hud kit their lield of labor tor the It il3-

kcr He was to sail md Ann Eli.:: came i matiolis fork-.ttill' cuid.A help laugh; .-he tried to look d.gT; I called to see her a lie "o: home Jeff and she was old tha t ma •umderfu dr..»d J

as for sewin', she said they need'nt

'• bodnhink s he'll do well here n-d,.elor d 1

Both newspaper mastheads arefrom Early Utah Journalism.

Turning the Tide: The Mountaineer vs. the Valley Tan

BY ROBERT FLEMING

WHE N READING HISTORY OF UTAH OR THE MORMONS one sometimes sees a statement such as the Valley Tan "was a bitterly anti-Mormon publication which did not circulate far from Camp Floyd."1 More often, however, such histories are silent on the subject The Valley Tans rival, the Mountaineer, has received even less notice in Utah history. Because of the historian's lack of attention, there is a mistaken conception about two of the earliest newspapers in Utah, the Valley Tan and the Mountaineer, neither of which ran more than two years. Their very existence and relative success during an important part of Utah history warrant more research; such work has not been adequately performed. This may be because the Deseret News, the survivor of early Utah newspapers but certainly not the best indicator of the times, has gained most of the historian's attention.

Mr Fleming is a graduate student in history at Brigham Young University, Provo

1 E. Cecil Gavin, U. S. Soldiers Invade Utah (Boston: Meader Publishing Company, 1937), p. 258. Similar statements are made in Orson F Whitney, History of Utah, vol 1 (Salt Lake City: George Q Cannon & Sons Co., 1892), p 724; Richard D Poll et at, eds., Utah's History (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), p 308; and Andrew L Neff, History of Utah, 1847-1869 (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), p 457

ea pert her to do any, for she'd cat sue a hc.my dinner she couldn't Mis Eu-iiek and Miss Teabody had got) • to Il.uri-wwu to buy Ann Eliia1 lets and engage a dressmaker t e over and make her new dresse: d got three very nice silk ones, an umber more, and there wa'n't 11 dressmaker in Scrabble Hill that wt iadiionabic enough to rig outamissiot frolic together She ' arv's lady tely to us, had her; "For a spell after I got there, I about halt a-vard'nnd looked with all the eves 1 had

VALLEY TAN.

The secondary literature on the Valley Tan consists only of a thesis written byJames Greenwell in 1963.2 While one-third of his short thesis discusses the Valley Tan, he focuses more on the later Union Vedette, the Camp Douglas newspaper There is no secondary material of any substance on the Mountaineer, which like the Valley Tan is mentioned only briefly in texts and related monographs. However, Cecil Alter gave both newspapers some consideration in his book on early Utah newspapers, as did Chad Flake in a paper delivered at the Utah Newspaper Conference.3

Despite their brief lives, these two Utah newspapers are significant and provide a glimpse into the sources of Mormon-gentile conflict during a difficult period in territorial history. The Valley Tans coming as an "opposition" paper to the Mormons' DeseretNewswas important to the gentiles, as it gave them a voice in the territory. However, sometimes this voice got out of hand. The Mountaineer attempted to serve as a check to the hypercritical attacks of its rival. The strategy of the Mountaineer was simply to try to direct the allegations of the ValleyTan toward issues that could be more easily dealt with while ignoring the real issues. Because of this strategy the Mountaineer was only somewhat successful in refuting many accusations in the Valley Tan and in bringing the truth to the people of Utah.

In 1847, when Brigham Young entered the valley of the Great Salt Lake, he envisioned it as a home for his people, away from direct per-

2 James Richard Greenwell, "The Mormon-Anti-Mormon Conflict in Early Utah as Reflected in the Local Newspapers, 1850-1869" (master's thesis, University of Utah, 1963)

3 J Cecil Alter, Early Utah Journalism: A Half Century of Forensic Warfare Waged by the West's Most Militant Press (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1938); Robert P Holley, ed., Utah Newspapers— "Traces of Her Past,": Papers Presented at the Utah Newspaper Project Conference, University of Utah (Salt Lake City: University of Utah, Marriott Library, 1984)

&

B Y KIR K AIVDERSOI\ ~ ' EIGHT

IN

VOLUME 1 GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

HRIDAY, DECEMBER 24,

NUMBER 8 THE

••:•!' ---:

!«-(.« .,,„>,.)_„„. 1S,.F_ l»r:.i.;

I li:.. „t.t., t - : .A .v .k VU

DOLLARS

AJDTA.NCE

U T.,

1858.,

VALJLBY

TANJ^'f wlul e the rapidity of traveling on I [Card from Pastnu&r Welter.] ] MAN DROWNED.—On the afternoon led, peaked and long razor-nosed, blue-

• •—_____ land has been three times greater than! Mails to the Aflati-ic of lastTuesday[26th ult.],a» JUeot Coi- niQutlwd.iiigger-lipped.whue-cyed.soft-

.r.

I hoaittwl Irsnjr.^nr^d rranfit-nArhed hlob-

secution, where they could begin to build their Zion. This dream of isolation, that had been slowly deteriorating since the gold rush of 1849, came to a screeching halt when PresidentJames Buchanan sent an army to accompany Alfred Cumming, the newly appointed governor of Utah Territory. Cumming arrived in 1858 replacing Brigham Young, the first governor, who was suspected of treason and rebellion against the United States government. Although Young was disappointed by these actions, he allowed the new governor to take his position.4 Along with Governor Cumming, many other gentiles entered the territory as federally appointed officers or as merchants and contractors following the army.

Even more disconcerting was the decision ofJohn Floyd, the secretary of war, that the accompanying army should remain in Utah to protect the citizens from the Indians and to ensure a peaceful transfer of power within the territory The over 3,000-man army, commanded by General Albert Sidney Johnston, marched through Salt Lake City and settled in Cedar Valley, near Fairfield, at a place they called Camp Floyd (appropriately named in honor of the secretary of war, an avowed Mormon-hater). This location put the army at an equal distance of thirty miles from two major settlements in the area, Salt Lake City and Provo. The Utah War, as these events came to be called, was rather uneventful in terms of physical combat. The real battle began with the struggle for power and influence within the territory.

Part of the Mormons' quest for autonomy and control in their settlements had historically been to establish a means by which church leaders could present news, messages, and information to members. In Utah that means was the DeseretNews. Established by the Mormon church in 1850 and first edited by Willard Richards, a counselor in the First Presidency, the DeseretNews was the only newspaper in the territory until 1858. Because of its religious purpose and strong Mormon influence, it would probably have seemed very biased and one-sided to the gentiles coming from the East. DeseretNews historian Monte McLaws explained that the editors of the Mormon newspaper were more interested in religion than journalism and were either in the church hierarchy or very close to it; thus it was never immune from suppression and editing by church leaders.5

4 This decision came only after widespread defensive actions by Young and through extensive negotiations led by Thomas L Kane, a long-time friend of the Mormons; see Norman F Furniss, The Mormon Conflict (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960)

5 Monte Burr McLaws, Spokesman for the Kingdom: Early Mormon Journalism and the Deseret News, 1830-1898 (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1977), pp xiii, xiv

226 UtahHistorical Quarterly

The motto of the DeseretNews was "Truth and Liberty," and its stated purpose was "to record . . . every thing that may fall under our observation, which may tend to promote the best interest, welfare, pleasure, and amusement of our fellow citizens."6 Although the Mormons had been accustomed to opposition literature and journalism from their Missouri and Illinois periods, in Utah prior to 1858 they had been journalistically unopposed. The events of the Utah War and the settlement of federal troops in the territory fostered bitterness between the Mormons on one side and the army and federal officials on the other. Each side held the other responsible for the growing crime and violence in the territory. The gentiles looked for a means of publicly destroying what they felt was the "scourge of the territory" and of rallying support for their cause. This means finally came in the form of an opposition newspaper. On November 8, 1858, John Phelps, an officer at Camp Floyd, proudly recorded in hisjournal, "The first copy of the Gentile newspaper has made its appearance. It is called 'Valley Tan.'"7

Earlier that year, on September 7, the Valley Tans future editor, Rirk Anderson, had arrived in Salt Lake City from Missouri. He was a successful attorney who had previously written for the Missouri Republican published in St. Louis. Brigham Young and other church leaders speculated that he had been sent by President Buchanan to

6 Deseret News, June 15, 1850

7 The term Valley Tan was originally used in the territory to refer to the first technological process brought to Utah, the tanning of hides; the Utah system was of such quality that it acquired its own name However, the term came to mean any type of home-manufactured goods in the valley, including a strong whiskey loved by the soldiers and a newspaper; see Richard M Burton, The City of the Saints, ed Fawn M Brodie (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1963), p 188 Quotation from John Wolcott Phelps, Diary, November 6, 1859, Special Collections, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo

The Mountaineer vs. ^Valley Tan 227 '•'•'•x

Commanding officer's quarters at Camp Floyd was photographed by Simpson expedition, January 1859. USHS collections.

stir up controversy in Utah and to harass the Mormons.8 From the words of one soldier, however, it can be inferred that Anderson was sent by the Missouri press as a "permanent" correspondent to cover the Utah War and its aftermath.9 Anderson also became involved in the territorial government and was appointed as a federal auditor for Utah, later testifying in favor of the Mormons' claim that they had not tampered with or destroyed court and territorial records. He also practiced law in the territory and was listed as the defense attorney for at least one important criminal case. 10 Little else is known of him, but among Mormons he apparently became known as the "homeliest man in the Territory."11

Shortly after his arrival Anderson began to organize all the resources he could find and quickly set up his newspaper shop in Theodore Johnston's building on South Temple in the heart of Salt Lake City. Much of the paper as well as many of the printing supplies and skilled printers he acquired came from the office of the Mormon DeseretNews.12

The first edition of Kirk Anderson's Valley Tan was published and distributed on November 6, 1858, mainly among the troops at Camp Floyd. It was circulated at the relatively high price of eight dollars per annum, or twenty-five cents per single copy, because, as Anderson explained, his costs were higher on the frontier. Each issue contained four pages with five columns per page, making the Valley Tan a little larger than its rival, the DeseretNews. One thousand copies were printed and circulated in the original edition.13 In appearance the Valley Tan was much like many other weekly frontier newspapers of the period. It contained local as well as national and world news. There was a "humorous" section and an editorial column, including letters to the editor. Business advertisements and personal ads often took up more than one-fourth of the print. However, as was quickly noticed, the purposes and practices of the Valley Tan were different from those of other papers of that day.

Anderson wasted no time in lashing out against the Mormons and their beliefs. The very first issue featured a vitriolic attack on the

"Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, September 7, 1858, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City.

'-' Harold D Langley, ed., To Utah with the Dragoons and Glimpses ofLife in Arizona and California (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1974), pp 106-33

10 Journal History, October 27, November 26, 1858,

11 Scipio Africanus Kenner, Utah As It Is (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1904), p 157

12 Journal History, November 6, 1859

13 Kirk Anderson's Valley Tan, Salt Lake City, Utah, November 6, 1858

228 UtahHistorical Quarterly

legality of polygamy. Subsequent issues also attacked the Mormons for their supposed treason and rebellion against the United States government, their protection of accused Mormons in the court systems, and for alleged acts of "blood atonement" committed by the Danites.14 So strident was Anderson that historian Donald Moorman has called him "that indefatigable military boaster and herald of everything Gentile."15

The Valley Tan was actually owned by John Hartnett, a nonMormon and the federally appointed secretary of the territory, who was also a friend to many prominent church leaders. Hartnett was known to the Mormons as one of the more lenient of the federal officials, but because of his newspaper he was often threatened with violence on the streets.16 When LDS Apostle Daniel H. Wells approached Hartnett regarding the harshness of Anderson's attacks, Hartnett replied that he did not agree with the direction the Valley Tan was taking but that some of the officers at the camp had sent word to Anderson that if he did not "pitch in like hell" they would not patronize him.17 The reasons for Hartnett's continued support of the Valley Tans anti-Mormon stand were clearly economic The troops at Camp Floyd were also pleased to support the Valley Tan, for it substantiated the rumors they had heard in the East regarding the Mormons. As the historian of the DeseretNews, Wendell Ashton, observed, "Utah had become a place of two camps—the army and its followers on the one hand and the Mormon settlers on the other Each now had a news"18 paper.

It is interesting to note that during this time of very serious accusation against the Mormons, the DeseretNews never even mentioned the existence of the anti-Mormon paper nor its demise seventeen months later. This practice of silence was based on a policy of church leaders who thought it was best not to advertise for the opposition by quarreling with them.19 Moreover, when the ValleyTan was about to perish for want of paper the DeseretNews loaned it enough paper to

14 During the Mormon Reformation of 1856-57, church leaders taught that there were some sins for which Christ's sacrifice did not atone; therefore, the sinner's blood must be shed for the atonement Shedding one's own or another's blood under this doctrine came to be known as blood atonement. Many murders in the territory were suspected of being perpetrated by a group of blood atonement assassins known as the Danites

15 Donald R Moorman and Gene A Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons: The Utah War (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1992), p 88

16 Langley, To Utah with the Dragoons, p 133

" Journal History, January 6, 1859