> F M CO CO 05 o F S w H

HISTORICA L QUARTERL

Contents FALL 1996 \ VOLUME 64 \ NUMBER 4 IN THIS ISSUE 297 FROM HAARLEM TO HOBOKEN: PAGES FROM A DUTCH MORMON IMMIGRANT DIARY TRANSLATED AND EDITED BYWlLLIAM MULDER 29 8 LAMBS OF SACRIFICE: TERMINATION, THE MIXED-BLOOD UTES, AND THE PROBLEM OF INDIAN IDENTITY R. WARREN METCALF 322 EMMA LUCY GATES BOWEN: SINGER, MUSICIAN, TEACHER CATHERINE M. JOHNSON 344 CHARLES W. PENROSE AND HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO UTAH STATEHOOD KENNETH W. GODFREY 356 BOOKREVIEWS 372 BOOKNOTICES 380 INDEX 381 THE COVER Emma Lucy

Violetta in Verdi's opera La Traviata Widtsoe collection, USHS. © Copyright 1996 Utah State Historical Society

Y

Gates as

THOMAS G. ALEXANDER. Utah: The Right Place B. CARMON HARDY 372

WILLIAM E. HILL The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and Today . .RUSH SPEDDEN 373

NORMAN R BOWEN AND MARY KANE BOWEN SOLOMON. A Gentile Account ofUifein Utah's Dixie, 1872-73: Elizabeth Kane's St. George fournal DOROTHY MORTENSEN 374

JOHN S MCCORMICK AND JOHN R SILLITO, EDS. A World We Thought We Knew: Readings in Utah

History DENNIS L LYTHGOE 375

WILLIAM D ROWLEY Reclaiming the Arid West: The Career ofFrancis G. Newlands DAVID BLANKE 377

ROBERT H WEBB Grand Canyon, a Century of Change: Rephotography of the 1889-1890 Stanton ^ Expedition .PETER H DELAFOSSE 378

THOMAS E SHERIDAN AND NANCY PAREZO, EDS. Paths ofLife: American Indians of the Southwest and Northern Mexico DAVID RICH LEWIS 379

Books reviewed

In this issue

As Utah approaches the sesquicentennial of pioneer settlement, it is easy to conjure images of hardships and heroism along the overland trail and to neatly conceptualize that great drama as having happened a long time ago Accordingly, one's sense of history will likely be exercised upo n reading Foekje Mulder's account of her 1920 immigration, presented as the first selection in this issue, and realizing that even in the moder n age of ocean liners and automobiles the task of immigrating was never easy. Worries over money, health, language, and employment plagued Foekje and others like her, and the sadness occasioned by leaving loved ones and familiar homes far behind was no more easily abated in the twentieth century than in the nineteenth Yet there are moments of triumph as well, and the reader of this diary will undoubtedly come to love the determined and sensitive Foekje, pictured here with her husband Albertus, and to be touched by the historical experience in a profoundly personal way.

Melting pot dynamics affected not just the newcomers but the native people as well When, in the 1950s, the federal government sought political termination for the Utes, the explosive question of tribal membership erupted into acrimonious debate. Complicated by a very lucrative judicial award won by the tribe and some long-standing intratribal antagonisms, the issue had enormous implications for both the blooded Utes and those of mixed ancestry A dispassionate analysis of that controversy, much needed and long overdue, is offered in the second article.

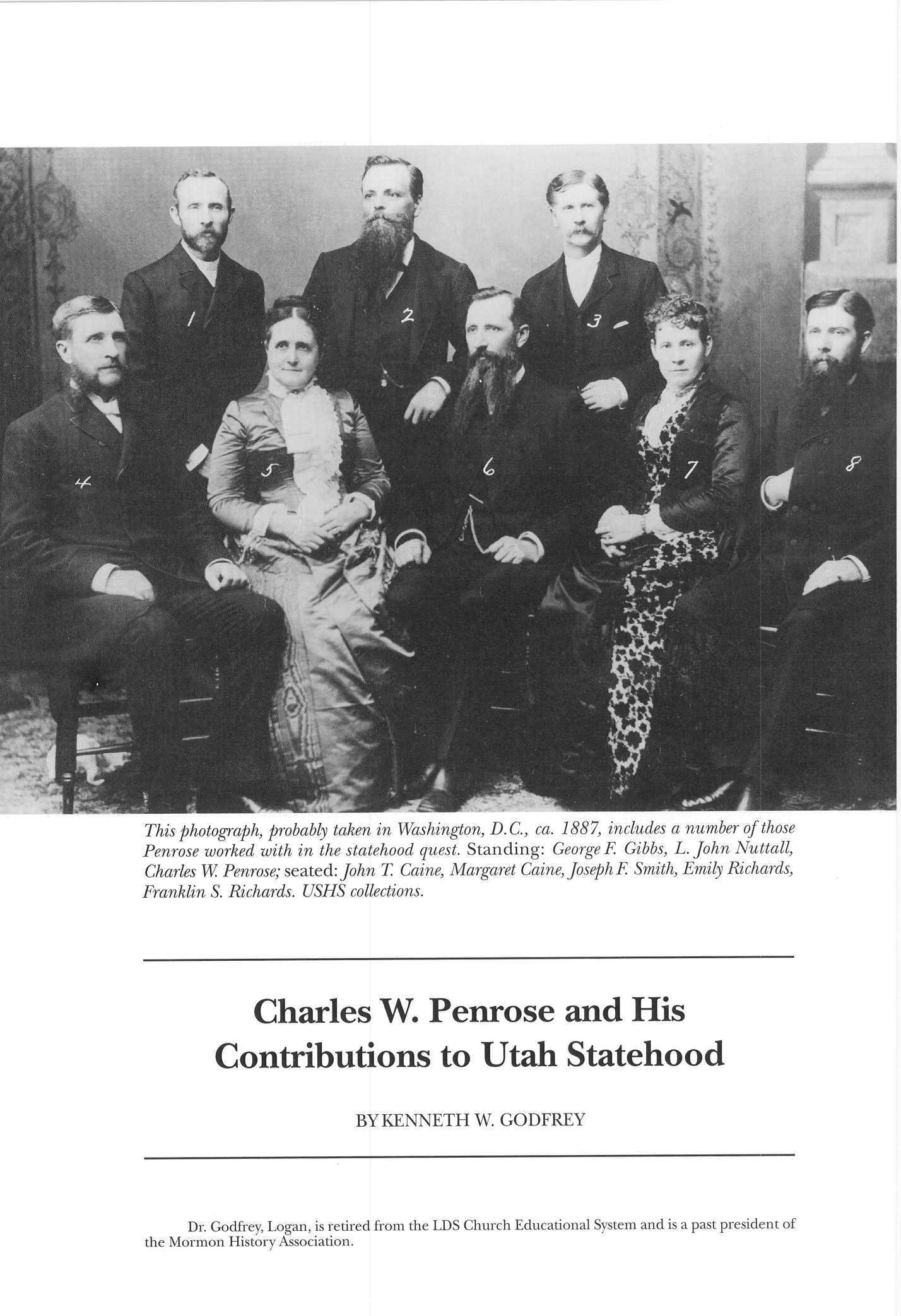

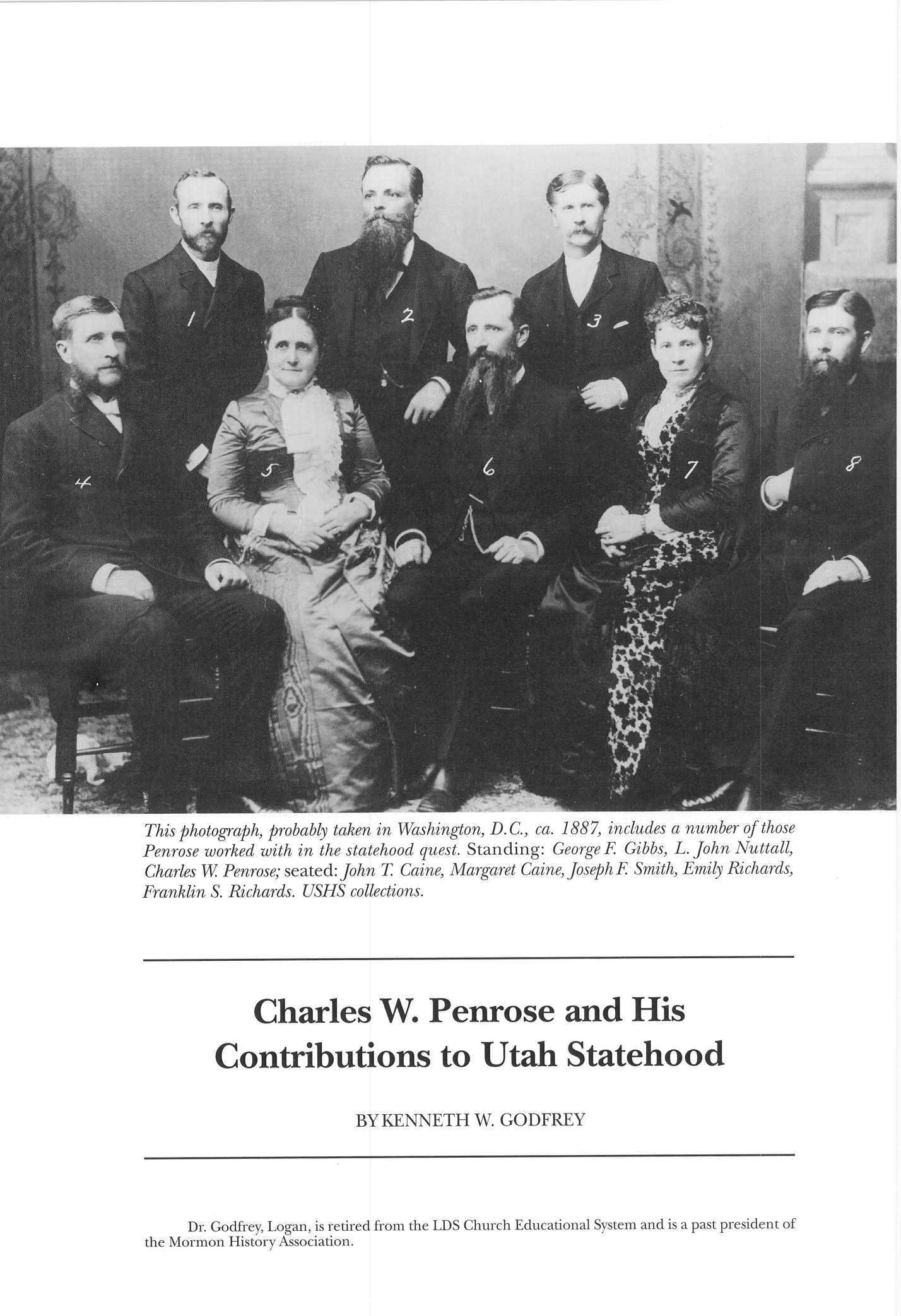

As we draw the curtain on a most memorable centennial year, it is appropriate that we return to the era of statehood for our final two articles The first of these is a short biography of the talented singer, Emma Lucy Gates Bowen. A granddaughter of Brigham Young, she represents the advancement of Utah culture beyond the pioneer period to the moder n opera halls of Berlin, New York, Boston, and Chicago At the very time the young starlet was discovering and developing her musical ability, Utah was also reaching political maturity and knocking at the door of statehood. One of the leading figures in that quest, Charles W. Penrose, is the subject of the last article As the author reminds us, if a Utah statehood hall of fame were to be established, Penrose would be among its first dozen inductees This illuminating study leaves no doubt as to why.

Engagement photograph, 1910, of Albertus Mulder, age twenty, and Foekje (Fannie), Visser, age nineteen, in Haarlem, Holland. Courtesy of William Mulder.

Engagement photograph, 1910, of Albertus Mulder, age twenty, and Foekje (Fannie), Visser, age nineteen, in Haarlem, Holland. Courtesy of William Mulder.

TheMulderfamily in 1920 on the eve oftheirdepartureforAmerica: Albertus and Foekje and their two children, Angenietje (Annie) and Willem (Wim). Family photographs courtesy of the author.

From Haarlem to Hoboken: Pages from a Dutch Mormon Immigrant Diary

TRANSLATED AND EDITED BYWILLIAM MULDER

Dr Mulder is Professor Emeritus of English, University of Utah He wishes to thank his sister, Anne Glissmeyer, childhood companion on that transatlantic voyage, for remembering or puzzling out names, places, and events, and to thank Theda Van Dongen, widow of the late Sebastian Van Dongen, who served for several years as Dutch consul in Utah, for reviewing his translation The original diary has been placed on deposit with the Utah State Historical Society

NINETEENTH-CENTURY PIONEER AND IMMIGRANT DIARIES are a commonplace in American, especially Mormon, history. Twentieth-century accounts of crossing an ocean and a continent to reach Zion are rare, perhaps because the journey seemed both less hazardous and less romantic than in the days of sailing ships and covered wagons. Yet the later convert-immigrants felt the same pains at parting from loved ones in the old country and the same anxieties on arrival as they dealt with the pots-and-pans realities of settling down in the new.

My mother's diary, kept from the day she and her young family left Haarlem, Holland, on May 20, 1920, toJuly 11, six weeks after arriving in Hoboken, NewJersey, provides a fresh glimpse of the convert-immigrant experience in this century, all the more interesting because my mother, though limited to a grammar school education, proved to be a sensitive, observant young woman. Her diary, written with pen and ink in a neat, meticulous hand in a ruled 6/i-by-8-mch hardcover notebook of the kind she may have used as a school girl, runs to 49 manuscript pages without margins, a bit of Dutch thrift, perhaps, to use every sheet from edge to edge. At my mother's death in 1977 at the age of eightysix it passed to my elder sister Anne (the An or Zus, for Sis, of the diary), who placed it in my custody (I am the Wim, for Willem, of the diary), in the hope I would find time to translate it as a piece of the family's legacy. That hope has finally materialized.

My mother was Foekje Visser, born onJune 19, 1891, in Amsterdam of Friesian ancestry. At eighteen she met my father Albertus Mulder, a nineteen-year-old apprentice printer from Delft, in a small Latter-day Saint congregation in Haarlem Both with Dutch Reformed Church upbringings, they had, unknown to each other, responded to the message of a restored gospel preached by Mormon missionaries from America and, captivated by the idea of "the gathering," looked forward to "going up to Zion" from the moment they were baptized. They were engaged in 1910, married in 1913, and had to wait out World War I while my father served on border patrol with the Dutch Army before they could take the fateful step of going to America. Two children were born to them in the meantime, the An and Wim of the diary.

A loan from Foekje's older brother John (the Koo—pronounced Ko—of the diary),1 already in the States as a "steamfitter" in the Hoboken shipyards, made the move possible Making the journey with them was Uldrik (known as Henry once in America), my mother's

1 The second syllable ofJohn's Dutch nameJacobus produced his nickname Ko.

Immigrant Diary 299

orphaned youngest brother who, at eighteen as an apprentice baker, became the family's first wage earner after their arrival in Hoboken.2

The diary's opening entry, "The moment has come to say goodbye," is weighted with the anguish of leaving my father's widowed and aging mother (the "Mother" of the diary) and his crippled, dependent sister Mien (for Wilhelmina), who felt bereft at their going. Anxiety about and yearning for them and for the old home thread the diary.

The family could not go on to Salt Lake City, their ultimate destination, immediately Paying back their immigration debt (a recurrent concern in the diary) and, as it turned out, assisting the families of two of my mother's sisters (Joukje, the eldest, and Geertje, the youngest) to come to America delayed them for six years. Meanwhile they learned English.3 My father by good luck, after unaccustomed hard labor in the shipyards scraping barnacles and painting hulls in dry dock, found work within a few months in his trade as pressman for a large printing firm in Manhattan. They brought two more children into the world, Mary and Albert, Jr. (In the diary my mother records the illness which marks the beginning of one of the pregnancies.)4 And they played active roles in the life of the Hoboken Branch, a sizable Mormon congregation in the Eastern States Mission in the days B. H. Roberts presided over it. Uldrik within a year went on to Utah ahead of the rest and established himself as a baker in Ogden, later in Salt Lake City, and ultimately in Compton, California. Throughout the years the hand that kept the diary wrote hundreds of letters in both Dutch and English (and sometimes in a mixture of the two) and occasional faith-promoting verse, the penmanship not as refined but recognizably kin to the beautiful script of the diary. My mother's correspondence was the wonder of all who knew her for its fullness of detail and bright observations Given the opportunity, she might have developed as a writer The diary is notable for narrative economy, descriptive detail, and introspection. It is a model of grammatical correctness, too formal for what I had hoped would be a conversational flow, and I have employed contractions wherever suitable to relieve the stiffness. There are few collo-

2 My

3 1 remember my grade school teacher coming to the house to give lessons

4 Mary married Carlton Ence, and AlbertJr. married LauraJohansen, both couples still living in Salt Lake City A daughter, PatriciaJoy, was born in Salt Lake City, now living as Mrs Herbert Shoemaker in Peoria, Arizona

300

Utah Historical Quarterly

mother came from a large family of ten brothers and sisters Her father was Harman Jelte Visser, the skipper of a freighter that plied the canals and rivers of Holland, Belgium, and Germany. Her mother, Angenietje Alta, died in 1906 when my mother was fifteen, a younger sister Geertje, eight, and the Uldrik of the diary, five. They were spared life in an orphanage when the eldest sisterJoukje and her husband Hermanus R Kikkert, recently married, convinced the court that they could look after the children and were appointed their legal guardians.

quialisms, but an occasional folk saying and numerous snatches of dialogue often bring moments immediately to life. Tense shifts from past to present and back again, always unconsciously suited to the movement of the narrative There are moments of pathos, passages withholding more than they reveal, rhetorical questions, anguished appeals to Heavenly Father, and a clear control as well as display of emotion. As much concealed as disclosed are the unnamed trouble with a friend, the concern about her relationship with her husband, a brother-in-law Willem's "forgiveness" (for what?). Recurrent entries record her observations of the beauties of nature, her trust in and appeal to her Heavenly Father, her longing for loved ones in Holland, her trepidation about what lies ahead, her resolve to persevere, her desire to repay their immigration debt Among poignant moments are the family's separation on Ellis Island, her finding precious mementos from home broken as she unpacked their sea trunks, her hurt when she finds her husband "a closed book" and her disappointment when he does not have a surprise for her birthday.Joyous moments include crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, boating on the Hackensack River, visiting Central Park in New York City, trolleying down the Palisades from Jersey City to Hoboken, the sight of candles on a birthday cake, receiving news from Holland, hearing "the Prophet" (the president of the LDS church), and gathering with "the Saints" at home or in congregation My mother found two small triumphs worth recording: the day her husband said the communion prayer in English and the day she read the 13th Article of (LDS) Faith in English.51wish there were a companion diary of the continental leg of the journey to Zion in 1926, six years after the family's arrival in America. But perhaps in this instance less is more, indicative of what wonders she might have reported along the Lincoln Highway and what anxieties and aspirations filled the days that became her prolonged years in that Zion on which she had set her heart so long ago in Holland

THE DIARY

[Aboard

Thursday, 20 + 21 May 19206

The moment has come to say goodbye. It was hard, very hard to part from Mother and Mien. O, they were so grieved. We had not thought that

5 The 13th Article remained a favorite, expressing sentiments she tried to live by: 'We believe in being honest, true, chaste, benevolent, virtuous, and in doing good to all men. If there is anything virtuous, lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy we seek after these things."

6 The departure by train from Haarlem and the events in Rotterdam are recorded on board ship as the diary's first entry, accounting for two days, the 20th and 21st of May

Immigrant Diary 301

the S.S. Rotterdam]

Mien would take our going away so hard. I had kept my composure all through, but when I saw Mien standing there so unhappy, it was too muc h for me. Sobbing, I left them, waving to them as long as I could Jan and Willem7 accompany us to Rotterdam At the station are Joukje and Joop, 8 Betsy and her mother. 9 At the last minute Joukje hands me a packet of sandwiches and chocolate for the children. As always, she is so caring. At 10:30

[A.M.] the train leaves; we wave as long as we can

Arrived in Rotterdam, a worker brings the hand luggage in a handcart to the Wilhelmina quay Uldrik with him, we with line 4 to the transfer boat There we wait until Uldrik and the worker come [who were] also ferried over. There lies the Rotterdam before us, huge and stately. First the baggage to the sheds. After that fetching the ship's papers. O how long we must wait. Albert and Uldrik are inside, the children and I, Willem and Jan wait outside; meanwhile we eat a sandwich with an egg.

When Albert and Uldrik had rejoined us and we came around the corner, we saw br v d Vis10 and Joop standing there. That was a surprise, really touching. At 3:30 we had to be at the doctor's. O, O, what a crowd. There were many emigrants—Russians, Poles, Germans, even Arabs and Negroes After an anxious time, one doctor examined the hands, especially between the fingers and the hair. The other doctor examined the eyes, not very gently, mind! Luckily all was well. Now we are free until eight o'clock, when only then may we go on board.

Now on a visit to Sister ten Hoeve.11 It's a long way and it begins to rain hard I'm thinking it's worst for Br v d Vis and Joop, Jan and Willem—they aren't wearing much. Still more walking. Finally we find the family ten Hoeve. The welcome there was most hearty, which did us a great deal of good after swimming about the whole day. Our deepest thanks, sisters, for the affection shown us Father bless you all for that

Br v d Vis and Joo p had to hurry away At seven o'clock Gerrie ten Hoeve12 took us to the boat. Again we had to stand in a crowd for a long

9

8

10

302 Utah Historical Quarterly

The diarist, Foekje (Fannie) Visser Mulder at age 27 in Amsterdam.

7 Jan Mulder, my father's elder brother, and Willem Van Os, a very close friend and member of the Haarlem LDS branch presidency.

Joukje Kikkert, my mother's elder sister, and her son Jan, sixteen, nicknamed Joop, who would be known as John in America after the Kikkert family's emigration three years later

Betsy was a close friend of my mother in Haarlem

Brother van de Vis, fellow convert and a member of the Haarlem branch presidency

11 The ten Hoeve family were LDS converts living in Rotterdam

12 Sister Gerrie ten Hoeve, mother's close friend.

time. There seemed to be no end in sight. O, how gladly I would have run away, back to all I hold dear; but no, that may not be; steadily forward.

Finally, at 9 o'clock, we got on board, where the others were already waiting for us. A crew member brought us to our cabin. Must we go in here? It seemed at first a prison cell. I burst into tears, long held back, and I couldn't help it but sobbed and sobbed. That relieved me and Gerrie said, "Let's make the beds; it's only for a few days," and so it is and I thought, Come on, Foek, have courage, all will come aright.

First the children to bed Our cabin has four berths, two above each other The children sleep together so that Uldrik can also stay with us That's pleasant for him There is no comfort in these cabins, no stool or even a wash basin, but we are lucky that our cabin is close by the lavatory and the W.C The dining hall is also close by Gerrie wanted me to visit Second Class The others had already done that Willem and I went with her The rain fell in torrents How fine everything is in 2nd Class The difference is too great I hope if we ever have the privilege of making this journey again we can also go 2nd Class Now we must simply make do

The wash places consist of a large space with a long row of wash tables with sturdy basins. We have to supply our own soap and towels. Jan, Willem and Gerrie take leave and we stay behind. We move the trunks a little and lay ourselves, very tired, to rest. The berths consist of a straw mattress on springs and because we ourselves have a pair of pillows and blankets we lie very well. We are too tired to think very much and quickly fall asleep.

At half past three [A.M.] Uldrik woke us to come and see the ship leaving the harbor It was still raining hard, but notwithstanding that there were still visitors on the wharf Greetings and best wishes were called out back and forth while the Rotterdam was drawn out of the harbor by tugboats

Farewell, Fatherland Shall I ever see you again? Farewell, dear ones, until we meet Each hour now takes us farther from you I can't deny that my heart is still full of longing to be with you again Many sacrifices will first have to be made, but thereafter the blessing will surely not be withheld Be of good cheer

It is now three o'clock [P.M. of the following day, the 21st]. We have slept an hour. That did us good. It is usually a cure for anxiety. I have visited a sick lady who is here with her husband and six little children. She is very ill. I brought her some eau de cologne (Mien, I am most thankful for the lovely bottle) and spoke with her. I think often of Mother and Mien and all whom we have left behind. Shall I ever see you one and all again?

Father, bless us that we might yet be able to do much for them The three of us have stood singing hymns at the stern of the ship, with full throat, as I love to do I often flee to my cabin when my longing overcomes me Not that it stops there, but I can be alone there and ask Father for strength that I might be a good support for my husband, soon to be in strange surroundings

There is great effort here to keep everything clean The crew have plenty of work Wim comes to fetch me to go above where I play some with the children and speak with one or another And some singing with that little group of Hollanders

Immigrant Diary 303

/^^_^_ J ^^ ' A.0 tmj(%C6 *a JL&

>_£*_<, -&4X*~&&- .»*T«*/ - _^Kl<^ ***!?•- - "**^/TCS'£>'«- •£-_-- £^-g^S&__

^ - • *_4-__ <s> >_j> ' -t***^__— ,2—«#£> ~-fa6&4»&&C J^5_L -Afc*_S vM^r '

• «0j5«at^fel-<l*T^«'- ~m^%^js^^^(jiM>t^. t t/fC —1&£0l£*£ -*_ W ' --_<iSS*W?* 4^4S* £ SgJ ^

T^^~- , <2^.^*_a* -^^M^b _^^^ t .^sS^__t_- <9f>«»- - Jkj« ? ^^^<^t^.^ii ^

^^pUp* ••.*f/-4t&0****.... ^<Sr8*l*S»C —_Si«^ 2 JM^I^." aCJH— ^m^jsfC^e^C^C^. C>

«l-T-^-ul<^&tvT!S^_~_ -Z>_S_- *_JT <-_-C»-*~- -j^Jfr*^ ^»^*_S«^»^^jSl_>*^« j -*»Sft**w

^Co^O^^— <~M0?Cif o**&fj£*if cnf 2J^ A^fcws^l , &ZZ ~_^2*=-~^?r ^

^*L J/^-^Z^^e^C*^'

At six o'clock below to eat—bread, ship's biscuit, and potatoes with mayonnaise dressing. It tasted good. After that a bit of fresh air. There are white caps on the waves More wind has sprung up

From 2nd Class and also from the upper deck near us sweets and pieces of money are thrown below to the children of the emigrants. The children fall over each other as they scramble for these things It is getting cold; [we go] below and put the children to bed. Myself to bed too so that I can write these lines on my bed. So, I close and shall try to sleep. I still feel tired and want most to lie down. It's wonderful to see our children sleeping so peacefully What a kingdom is ours Father, wilt Thou watch over us this night Amen. F[oekje].

The Rotterdam, Saturday 22 May 1920

It is now nine o'clock in the morning We have had England in sight for a considerable time Because our Annie slept so long, I have missed much of this beautiful scene. In the meantime, I have tidied up our cabin a bit. We have all slept wonderfully well. Last night went to bed at half past ten, first sewed somewhat and wrote some cards so that it got to be very late It is

304 Utah Historical Quarterly

o_s»i>>---^J<C»^WT^-_^_i y(\JaJ*** -Jxey* o&- ^C^y'T^sK ^ i^*M Cfa^f^T '&~~ J/&pth?.\ c>*4P- oc L -^/-^-B^-S^L *«-#<jx~t. &&- ~&&itr&&, ^^_%^«___i_ *»<£«_• <-MT~C^U^- M~- £&^(t£& :X^M- ••~ff£+~r***-*y OZ*- -Z_^C^_~*CJI^_ <*_- _I*_y F^io/fc £^ ~ ^>- ~ ^ -^^-^L f^fejP"^ handwritten diary.

good weather; the seagulls continuously fly around the ship hoping for food. Enough gets thrown out from the kitchen. Bert complains of stomach ache, which lasted all through yesterday. I hope it gets better soon and he feels cheerful again.

Heavenly Father, we thank Thee that we are able to greet another day. How great is Your wisdom that we behold constantly anew in beautiful nature and Your great creation.

At half past six the gong wakens the people and at half past seven another gong for breakfast. Bread and jam, as much as you want. The waiters are friendly and helpful, the Hollanders' desires their first care in all things.

We are now enjoying the beautiful sight of England's coast. O, what a splendor do our eyes see, I cannot describe it. Beautiful landscapes, valleys and woods wherever the eye stretches. Plymouth harbor, with her pretty lighthouse and here and there various little ships. A boat comes alongside and brings us 400 passengers—there are now 3,600 in all. The Third Class alone has 2,000. So always crowding, very unpleasant. We sit on the canvas [cover] of one of the lifeboats because the few benches here are in constant use by the many folk. As we now experience it, Third Class is very unpleasant. This is the source of the annoyance [of being] nowhere able to find a restful little place to sit reading or writing. Besides, Uldrik is bored. I'm constantly busy trying to keep the children away from that dirty traffic. Wherever Sis carries the doll she gets a lot of attention. The sun shines gloriously. It is warm. The reflection in the water is beautiful and I never tire gazing at it.

We are yet lying still in Plymouth harbor. Directly in front of me I see beautiful overgrown rocks. Yes, these shores are beautiful, more beautiful than what we saw in Germany.

At twelve o'clock we ate pea soup, potatoes with endive, meat and some pickle It tasted good and we were given plenty, although of course it's naturally not as delicious as at home

I have slept a couple of hours. I fell asleep where I sat so that I went to my berth to lie down. A staff member opened the door of our cabin and asked, "Any sick?" No, luckily not. It is now five o'clock, now briefly outside and then at six o'clock again at table. Bread and a warm snack. Many are already sick. A dismal sight, the filth here and there, and the emigrants [uitlanders, literally "outlanders"] are so very dirty, bah! We make steady headway through the ocean.

So, the children have gone to bed; darned Wim's stockings, then one more quick look outside and then under the wool. Bert happily feels well again. I have stood singing with a little group of Hollanders, sociable, we must encourage each other. At 10 o'clock to bed. The second day is at an end. F.

23 May First Day of Pentecost

Today Henkie13 would have been ten years old had he lived. How swiftly the time flies By 5:30 we were already washed and dressed, thinking it was

Immigrant Diary 305

13 Henkie was the son of Herman and Joukje Kikkert Born in 1910, he lost his life at six years of age when he fell into a neighborhood canal and drowned

later, but we are already two hours behind Holland time Annie sleeps restfully on; [I] walked a bit on deck; it's so heavenly restful there now It is beautiful weather

At table by 7:30. There is corned beef, surely because it's Sunday. Took a sandwich for Sis. Because so many are sick it was not crowded, but still too crowded to say a blessing aloud; we do that together beforehand in our cabin. What a different life from home, but it is only for a short time. I have asked for a deck chair. These cost 1 and 1/2 dollars, but there are none left over from 2nd Class, so then [we do] without. We feel ourselves lucky for which we are very thankful. Now our eyes see nothing but sky and water. At twelve o'clock we ate soup, potatoes and beefsteak, prunes and raisin bread. The food is fine and so is the service.

I can't really believe we are actually going to Zion What will the future bring us? We don't know, but this I know, that God lives and if we do His Will all will be to our benefit whatever we experience, be it good or bad At six o'clock we passed the Hook of Holland, but I felt so tired that I lay until eight There's the reaction and now I feel how exhausted I am At eight o'clock breakfast, bread, butter, cheese Everything is clean and sanitary If only those filthy folk weren't there They are so disgusting.14 It's good they eat apart and sleep in another section but still you encounter them everywhere We have asked for hot water and have made cocoa ourselves At twelve o'clock the gong sounded again for the midday meal: soup, potatoes, much meat and barley with raisins Food in abundance Bread on table at every meal It tasted good The children ate only a little soup

At two o'clock we had a pleasant sitting on deck We now have the Krijtbergen [Chalk Mountains] of Germany [sic; England?] in view A beautiful sight with the sun shining It is moving when we see how grand nature is The children are enjoying the out of the ordinary and are as free as a bird It is also such beautiful weather At six o'clock eating again Bread and a warm snack It's all good Only the crowding oppresses me Sat again for a lovely moment on deck; refreshed by eau de cologne, am feeling much more cheerful The children were dear Bert and Uldrik sat reading Slowly Germany's [sic] coastline is disappearing, after we had taken on 200 [?] passengers from there

We are going to retire early, hoping that every day we shall have such beautiful weather. I end for this day.

24 May 2nd Day of Pentecost

Up at 6:30. Lay awake a long time last night listening to the slap of the waves and the murmur of the sea. Many thoughts, O, so many, have gone through my head. I long to be back in our house and stay there. How one must always struggle to make a sacrifice. We wish we could receive the blessings easily. If we with the help of the Lord can see the truth and are willing to undertake these, then all sacrifices will be rewarded

At half past seven breakfast, cheese on table The children are dear

14 Fastidious all her life about cleanliness, my mother had no kind words for the east European emigrants

306 Utah Historical Quarterly

After that tidied up the cabin, and now we are sitting on deck Wim attracts general attention when he sets his [toy] Negro dancing.15 That makes for some relief The weather is not as nice as it has been, much wind We all feel very well We see a great ship in the distance, saw one yesterday too

It's 12:30. We have eaten: brown bean soup, potatoes with sauerkraut and bacon. There's bread on table with every meal. Bought a couple of oranges from the pantry @ 12 cents each An[nie] and Wim have found a companion, a 15-year-old girl named Jo She provides the children with some entertainment Sis sits working beside her and Wim with the dominoes

Bert and Uldrik have a midday nap and I shall follow their example The sea breeze makes [one] sleepy On deck one must almost always walk or stand because people always occupy the best places When the sun is warm they lie tangled together like animals on the ground Now and then we play tag How is everyone in Holland faring? I'll be glad to hear they have received a letter from us Be assured, everyone, all is well

At six o'clock ate bread and rice. That was food for the children. After that we went on deck again for a short while. It's not so crowded now. It is 8 o'clock. Bert and I have put the children to bed. Uldrik sat on deck to read. We have to walk a long way before we can go up and the most disagreeable part is that we have to pass through the space of those emigrants. We must learn patience, much patience. Uldrik has just come below and tells us he has seen the sun set. I hope to see it once [while we are still] on board.

O, if I could only see the future for a moment. How shall our way be? We don't know, but I do know with my whole heart that God lives and if we try to do His Will we shall return to His presence. And that is worth the struggle to go forward and to fight the good fight to the very end. For O, how short is our life compared with eternity Father, give us strength to go forth in Your might F

Tuesday 25 May 1920

I'm glad we can get up because it's getting too stuffy in the cabin. Quickly washed and dressed, and helped the children. With that I can always count on my husband's help. He's always ready to help and I'm grateful to him. It does me good to feel his love.

Breakfast at 7:30, bacon on table that tasted so good Sat on deck a little while and read English Sang a little and at 11:30 at table again Pea soup, potatoes, stringbeans, meat and some pickle After that a lovely nap I'm getting lazy

Walked on deck again for a little while and at half past five mealtime again—bread and meatballs with new potatoes. That was tasty. Then again a short nap and then put the children to bed. When they were asleep we went to sit in the cafe. Bert and Uldrik read and I write a little. When I finished, I walked about a bit. A crew member asked me whether I would care to see this and that. Yes, very much, if you please. So he led me around and let me see everything such as the printing shop, the kitchens, the preparation gal-

Immigrant Diary 307

15 I remember a colorful tin wind-up figure with jointed arms and legs that could be made to "dance," the stereotype, as I realized years later, of the black as entertainer

ley, the engine room, the section for the personnel, and thus brought me to the foredeck, where I stood talking sociably for a moment with some of the crew. I was made aware that our ship was signalling to another visible on the horizon. Then I got Bert and Uldrik and retraced the same way with them. On the foredeck stood talking a while with the cook from First Class, and then to bed.

It was a pleasant evening for us F

Wednesday 26 May 1920

Both my husband's and Uldrik's watches are broken so we can't tell time unless we ask someone now and then I got up with a severe headache and wanted most to go outside right away How is it I have to fight against depression? We are all healthy. Come, hold the head high.

At 7:30 breakfast, cheese on table. It doesn't appeal to me. But I steel myself, determined to do my best. The children are glad there is cheese. Quickly up on deck It's lovely there I have good company in Jo's mother, a good little woman It is remarkable that such a good spirit prevails among so many different nationalities. The sea is beautiful and smooth as glass. We stay on deck the whole morning, delicious! I wind yarn with Jo's mother, talk a little, and read again But the time still drags Everyone longs for an end to the journey. It hurries up; if the weather stays the same we may arrive on Saturday.

At 12 o'clock at table: vegetable soup, potatoes with fresh meat and rice with raisins. Th e food is good, but always bland. Afterwards sleep for a couple of hours and then up to the deck There is more wind, whitecaps visible We enjoy a lovely sitting and remain there until five-thirty. We saw a ship in the distance.

We eat sandwiches, potatoes and gravy with meat I take my sandwich up on deck. Below I am quickly full. It doesn't go well today and my head is whirling.

At 8 o'clock Bert helped me put the children to bed. Bert and Uldrik sit by me and also write. Now I must mend Sis's stockings and then we go to bed Hoping for a good night's rest, I close F

Thursday 27 May 1920

This morning got up at 6 o'clock and had breakfast at 7:30. Corned beef on table. Our children are happy and healthy. Albert and Uldrik also feel well But what ails me I don't know I feel different than usual Am I getting seasick? I hope not The weather has totally changed The sea is unruly and angry. Shall we now get bad weather? I quickly lie down. Would I were home. Bert hurries below and does everything for me.

At 12 o'clock to table, but it does not appeal to me I am determined to keep well but it does no good White bean soup, potatoes with string beans, meat and pickles were on table. I have gone to lie down again, and afterwards sat in the salon. I felt a little better, thank goodness.

At 5:30 [sat] at table and ate a small portion. Again on deck for a bit and then put the children to bed A heavy fog has settled down, drawing closer and closer to the ship The foghorn sounds continuously I end My energy is gone. Father, keep us safe from harm. Amen. F.

308 Utah Historical Quarterly

Friday 28 May

This morning up at 5:30. The weather is fully improved, lovely mild weather. The fog has lifted. At 7:30 breakfast, cheese at table. I am recovered but our Wim is not normal. His beautiful blue eyes look feverish. He has no energy and just wants to sit on my lap. We hope he'll soon be better.

Yesterday we saw several icebergs in the distance That was a beautiful sight We have sailed more southward in order to avoid the ice fields. That cost a half day's travel The days are long because we are wakened so early and then glad to leave the cabin where it's so hot

At 12 o'clock we went to table after spending the whole morning on deck The midday meal consisted of vegetable soup, potatoes and meat, and barley with raisins Wim ate nothing After lunch we all slept and then went quickly up to the deck Wim is listless It is wonderful on deck There is opportunity to send telegrams at a cost of fifteen guilders Every now and then we see the birds, a sign that we are closer to land This morning we overtook a boat which we could plainly see

It is now 8 o'clock. Wim lies in bed. I sit by him and write. Bert, Uldrik and Ann are up on deck. I hope that my darling will be better in the morning. F.

Saturday 29 May

Last night I woke up at about three o'clock and could not go back to sleep. So many thoughts went through my head. Wim is still feverish and restless. Got up at 5:30. It is beautiful weather. The sea is so calm. A beautiful rose glow lies on the horizon. At 7:30 breakfast, jam on table. Wim ate a thin little sandwich. He is so listless. He goes on deck with Pa and wants to be carried.

Yesterday a child in 2nd Class died, a terrible blow for the poor parents.

At 11 o'clock we are summoned to see the doctor; such a throng; we waited until the very last; all in order.

At 12 o'clock at table: pea soup, potatoes and meat and endive and pickles. It was not appealing; there's no real appetite. Wim ate nothing at all. Afterwards I put our darling to bed. He has high fever. We stay with him. He just lies still with his eyes shut.

At two o'clock we hailed a freighter from Rotterdam, Now and then there is a heavy fog. We are rapidly approaching our destination. Shall we have solid ground under our feet tomorrow? We hope so. Shall we see Koo16 tomorrow? Has he been able to get a house? Time will tell.

Bert and Uldrik are getting some fresh air Annie is playing in the hallway and I sit by Wim and write Evenings there's more sociability than during the day Negroes box for fun, couples dance, and other sing whatever, and so the time passes O, I long so to make our house pleasant once again and renew my activities Patience will win out!

At 6 o'clock we ate rice Wim had a little of it This afternoon he was delirious and called out for me all the while I was with him Now he's a bit better, the little darling

It is now 9 o'clock. I spent a moment on deck while Bert tended the

Immigrant Diary 309

16 Mother's elder brotherJacobus (John in the States) who would be expecting them in Hoboken.

children already in bed The workers are busy getting the baggage out ready to load.

I just received word that all the Hollanders are to breakfast at 5:30 and be packed and ready at seven on deck. So now to get packed. This is the last of what I write on board. Where shall we rest tomorrow night? I don't feel very well O Father, lead us on our way Be ever close by F

[no entry for 30 May]

Hoboken 31 May 1920

We are happily at Koo's Yesterday after we disembarked we had to wait [dockside] in the shelter until all the baggage had been sorted. O, what an endless wait. It was finally over and when we thought we could go on to Koo's we were sent down a ramp, put in a boat, and taken to "Island Eiland" [Ellis Island] where we were inspected very closely What I endured there only my Father knows. I was taken care of and the children too, after that Uldrik, and when it was Albert's turn he was given a big chalk mark on both shoulders of his jacket and was set aside to be more closely inspected We had to go upstairs and were brought into the great hall and there more waiting. O, what anxiety that was. My waiting was one prayer that my beloved would be found in order. In such a moment you realize what you mean to each other. Happily, there he came It had been a mistake.17 How thankful I was

After that our papers were looked over and we could go. But first all our money exchanged, which wasn't very favorable We had to give 2.85 guilders for one dollar Then we could buy a box with edibles for a dollar We were glad because we had not eaten since half past four in the morning and now it was six o'clock in the evening. The children had a sandwich around 11 At half past six with the ferryboat to New York There a friendly man approached us and said "To Hoboken?" Yes, was the answer, and we were invited to step into a carriage,18 the baggage on top and we headed for Hoboken. We were under the impression that the man was a friend of Koo and that Koo himself awaited us at his house But we soon had other thoughts. After quite a while and riding through ugly streets and impassable ways we came to Grand Street No. 1409. Did Koo live there? I couldn't understand it and I felt miserable and I'm sure Bert and Uldrik felt the same way The children were the best off and enjoyed the out of the ordinary Albert rang the bell and, God be thanked, there came Koo. O how glad we were. His first words were, Couldn't you have let me know?" We looked surprised. It so happene d that Koo had not received our letter and now we stood unexpectedly before him O, how sorry we were about that How glad we were when we were good and well upstairs, where we were received by a

17 My father had a festering thumb, injured at work in Holland, which, after that long day's anxious waiting, was determined to be noninfectious As a child of five I added to my mother's anxiety when I failed to respond to an inspector's request to speak, to say anything at all to prove I was not deaf and dumb. "Zeg iets!" ("Say something!") my mother implored, shaking my shoulder. I stayed mum. The inspector let us pass

18 To everyone's wonder, a horse-drawn coach This episode has been the subject of family anecdote ever since

310 Utah Historical Quarterly

friendly lady.19 Her mother and daughter were also close by and a Dutch boy, a brother of Riek Wessels.20

Preparations were quickly made for us but we were too emotional to eat very much. Koo had wanted to surprise us and have everything ready, and now that fell to pieces. That was just too bad for him and for us, but we were here—that was everything

And now Emil, as the lady is named,21 is our good genius Today is Koo's birthday, and so it has been our pleasure to be able to congratulate him in person. We are still exhausted and I have no real desire to go out.

Now we have gone with Koo to the cottage he bought.22 O, how lovely it

19 The "friendly lady" proved to be Koo's betrothed, Amy, whom the diary variously miscalls Emil, Emy, and Emmy Family lore has it that UncleJohn met her in a brothel, which accounts for my mother's surprise to find her so compatible, "clean and eager and not the waywe had pictured the 'ladies,'" in the entries forJune 1 and 3 below

20 A friend in Holland

21 See footnote 19.

22 204 Meadow Lane in Secaucus, NewJersey, on the banks of the Hackensack River It was true countryside; Farm Road, which led to Meadow Lane from theJersey City trolley line, reflected the neighborhood's rural nature I remember a pig farm across from our cottage and meadows filled with iris (flags) and rushes (cattails) spreading out toward the river

Immigrant Diary 311 ..>.

Theprincipals in thediary in theirfirst American home at 204 Meadow Lane, Secaucus, Newfersey: Uldrik (Henry) Visser (brother ofFoekje), Foekje and Albertus Mulder, Wim, and Annie, 1920.

is there. We feel ourselves most thankful that we shall live there, if all goes well It is what I have always longed for, a cottage outside the city We are most thankful to Koo for going to so much trouble for us, and hope that he will never regret having helped us. We have returned by riding over the heights [the Palisades] by tram. We have walked and enjoyed the lovely views from the heights and the beautiful surroundings It is more beautiful here than I thought yesterday All will come out well, even though at first we may have a hard time. We feel ourselves well and Koo, too, and that is the main thing.

This evening a pair of Koo's friends paid a visit and we sat sociably for a while, although I could hardly keep my eyes open. How would Mother and Mien be faring? Wouldn't they be worrying about us? And for all we hold dear, we hope the best.

We have had a lovely boat ride with Koo on the "Hakkesak" [Hackensack] River. F.

Grandstreet 1 June 1920

We have slept wonderfully and feel ourselves more fully rested. Koo has gone with Bert and Uldrik for information about our baggage I help Emil some I know I shall become very fond of her She is good and we must feel ourselves at home here. We sleep in her bed while she herself sleeps on the floor. The children are also entirely at home. Sis plays with a doll almost as big as herself

We have done some shopping and I enjoy it The stores are altogether different from [those] in Holland, but there is everything to buy. The prices are much higher than Willem had told us, but that was five or six years ago. Koo went to a bakery with Uldrik and he was hired at once It was 9 o'clock when they applied and Uldrik can start at 5 o'clock He will earn 20 dollars a week. That's a good beginning. We're very happy about that and hope Albert also meets success so early. F.

Grandstreet 2 June Wednesday

It is terribly warm and we wear as few clothes as possible. Emil goes to her work and I must do the wash; we have so many soiled clothes from shipboard I had not thought I would feel at home so quickly Emil and I speak as distinctly as possible so that we can understand each other. The washing here doesn't require bleaching and dries quickly. I have ironed so that everything has been done in one day I feel tired and sleepy; I blame this on circumstances

Th e bakery suits Uldrik. H e just has to persevere, as we do, which makes us strong. Koo takes Albert along to work.23 He sat in a boiler with Koo and came home black The change is very great for him I hope he will soon be in a position to be earning, so that we can quickly repay our debt He earns 54 cents an hour. F.

Grandstreet 3 June Thursday

So, I have tidied everything up and all have been home to eat. I shall send some cards to Holland. I should like to sit in a corner looking at them.

312 Utah Historical Quarterly

23 At the

Brooklyn shipyards

I should like to write them all, but there's so much. It's so warm again. The children are cranky from it

This evening we are going with Koo to our future dwelling and put everything in order so that we can move in tomorrow The children will enjoy such freedom there We feel thankful for all the blessings we receive

It's 11 o'clock at night We have gone to the house with Koo and reached an understanding that we can move in tomorrow Uldrik and Koo stay with Emil for the time being until our house is entirely vacated. The tenants are still there and we will occupy the rooms upstairs.

I can see that there's enough for me to do. What I have seen is dirty, the stoves rusty, but if I stay well nothing will be too much for me.

Emil surprised us with "ice cream" when we returned. That was tasty. Our Annie had gone to the ice cart and wanted some ice so Emil got ice cream later. She is always trying to please us and the children. The children are fond of her and also Uncle Koo

I believe that if we could understand each other better we could see much in each other She is clean and eager and not the way we had pictured the "ladies." There are many such, but Emil is like us. I see she is opposed to our going to the house in the morning but I shall persist. We had a pleasant walk with Koo and also went to the river I hope with all my heart we shall have much enjoyment and see troubles and cares through with courage

Br. Muse with Jo and Riek24 were here yesterday evening. I was so pleased they came. I have feasted tonight on the beautiful sight of the river where the evening red was most beautiful Nature is the loveliest of all F

Secaucus [New Jersey] 4 June Friday

We are in our new house. Koo brought us. One room upstairs is vacant and the lady is willing to help us with everything we don't have yet It was hard to leave Emil How is it I could become so attached to her in so short a time? We were good together, our characters are so much alike. I am certain she will make a good wife for Koo. I'm sorry I couldn't keep my composure, but when we left, the tears, held back so long, came and I could not help sobbing I quickly mastered myself and we were able to leave And now we are here and will do our best to see it through.

It will be nice when the tenants are out and we can have the whole house. We have such a lovely view overlooking farmland and everything green around us It is far from the men's work but they are willing to take the trouble in order to live here.25

Secaucus 5 June Saturday

I'm glad the night is over O, such a night it was Wim constantly awake with a terrible earache. We spent the night looking after him. And to our great shock we saw the bugs26 on our bed. It was an old bed from the tenants.

21 Brother (in the church) Muse, spelled elsewhere as Muuse, and Jo and Riek were fellow converts from Holland living in Hoboken.

25 For Albert, my father, it meant a long trolley ride to Hoboken and by subway or ferry to Manhattan and again by trolley to Brooklyn Uldrik had to go only as far as Hoboken My father's daily trips were shortened to Manhattan after he found work with Van Rees Press

26 The diary calls them wandluisen, which translates simply as "bugs"—they could have been bedbugs or cockroaches

Immigrant Diary 313

I killed three Now I know what bedbugs/cockroaches [?] are! They have an awful stink. If Willem were here he would know what to do because he experienced this himself. I beat the old bed and hauled it outside. I would rather sleep on the boards. I could cry, it's so filthy here and I am not free to cleanse everything I have cleaned the room as best I could so it feels fresh The lady here is German and it seems that people do only for appearances, as they say. 27

I wish I had some writing paper, then I could write to Holland.

Yesterday I bought a few things with Emil that we needed the most, such as a small pan with a handle for 70 cents, a frying pan was a guilder 27, a small pail for 80 cents, an alarm clock for 2.40 And some groceries Our trunks still have not arrived.

The children already feel entirely at home. F.

Secaucus 7 June Monday

It is nice weather Now the children can be outdoors Yesterday we had a pleasant Sunday School. At around 10 o'clock we went by [trolley] car from here and were with the family Muuse.28 We spent a pleasant while there. Bert played the organ and we sang It was as though I were home again Then Jo and Riek came by and we briefly went to their house with them Everything there is neatly in order and Sister Muuse would be satisfied should she come here. Some Hollanders had arrived on the Lapland and were lodged by Muuse in the Willom.29 They are going on to Salt Lake At two o'clock to the meeting, where from 2 to 3:30 Sunday School was held and after that the meeting until 5.

We liked it very much. It is a nice hall and the congregation is about as large as in Haarlem I had a good impression and was glad to have been there

It's good that we had no great expectations; now much seems agreeable and we can adjust in all things. I feel myself drawn to the family Doesie30and hope to become better acquainted

From there we went to Emil, who had invited us to have supper with her. We were hungry and glad to be able to eat. I was glad to see Emil again and I hope that her good time will come. After supper we were treated to ice cream It's expensive—costs 70 cents a little box

At 9 o'clock we returned home where everything lay in deep rest on our arrival.

Now it is Monday morning I have already done the wash once and it's ready to be laundered further. I'm thankful we all feel so well and my most earnest wish is that everyone in Holland may know this.

It is now 10 o'clock. We have been to the river and Bert has bailed out Koo's boat, which had filled up in the rain The children and I sat in the boat and enjoyed the lovely evening.

314 Utah Historical Quarterly

27

28 In Hoboken 29 A hotel? 30 Fellow converts

The saying is "Voor't oog wat wissen" ("What passes before the eye")

A beautiful sight greets one there on the river the lovely green and the houses against the hills—it is so pretty.

In the meeting yesterday testimony was borne in three different languages—we heard Dutch, English, and Danish Uldrik was not with us; he had to work from 12:30 to 8:30

Hoping for a refreshing night sleep, we give ourselves to rest F

Secaucus Tuesday 8 June 1920

It was nice weather today, this evening a lovely rain shower I have cleaned our bedroom as thoroughly as possible O, it's so awfully helpless There is no equipment and I can't really feel at home with everything so grubby.

The days seem long and I am homesick for Holland. I feel so alone and I fight against it as well as I can but I feel O so grieving. There is no one to whom I can express myself. Only Emil understands me, could we only understand each other a little more. She was here for a little while this evening, which I appreciated. She has given me a new name because my name [Foekje] sounds so strange here as an improper word. She calls me Annie.31

If I could I would go back at once. That leaden feeling doesn't leave me. Shall I ever on this earth feel truly happy again? I don't think so. My husband is to me a closed book. Heavenly Father, open his heart more to me, so that I can be more to him. O help me. F.

Secaucus. Wednesday 9 June 1920

I have wandered about a bit with the children Everything is so beautifully green I feel at my best outdoors I would very much like to go to Hoboken, but I must be very thrifty, otherwise we won't make it

We have done some shopping—hamburger, prunes, but I don't like the meat, it looks so dark. The prices are very disappointing. I watch the weight closely. The children ask to be taken out again. That's what I'll do because indoors I feel miserable. The sacrifices are more than they seemed at first. But God will not forsake His own, and if we are faithful, all will be well.

Bert brings home a letter from Holland, from Willem It's so nice to hear from him so soon Bert had already hung his portrait and said that feels more like home I am very thankful that he had done his best to feel he could forgive and that it has turned out so well for him after much struggle.32 All things will work together toward our eternal welfare F

Secaucus Saturday 12 June

It is warm, terribly warm.

Yesterday I was able to clean our room thoroughly. I'm glad of that, although it's not easy in such heat to clean someone else's dirt. Everything has been neglected and it will take a long time to make it all good. Thursday our trunks arrived, to our joy. It cost 5 dollars and 7 cts, to our good fortune. Since the room was cleaned yesterday I have opened the big trunk curious whether everything arrived whole. Two blue saucers are broken, and the glass in a pair of small paintings. But the big portraits and the mirror are

31 "Annie" became "Fannie" to avoid confusion with daughter Annie

32 We have no clue that could explain this reference

Immigrant Diary 315

whole, though somewhat damaged, but we are glad to have them here Bert has hung them, which feels more like home. The sugar bowl is broken too, which makes me sad because I had been given that by Mother.33 Now I sit on the porch and write after first working in the kitchen I am glad tomorrow is Sunday If I could only be with everyone in Holland for a moment F

[no entries for 13, 14, 15 June]

Secaucus. Wednesday 16 June [marginal note]: Sunday Albert blessed the water for the sacrament in English.

It is so tranquil all around me I feel as if I am in Friesland, everything is so pastoral, even the language resembles the Friesian.34 Sunday [June 13] we had a good time. It was announced at the meeting that the President [Heber J Grant of the LDS church] would speak in Brooklyn at half past seven We went there with a small group of Hollanders after sandwiches at Br Muuse's What a shame Uldrik couldn't be with us; he had to work again. First by ferry to New York and then after walking for about a quarter of an hour we reached the trolley which took us to Brooklyn. We crossed a suspension bridge [Brooklyn Bridge]; it thundered over at a steady pace It was a wonderful ride. We could see the houses far below us. Now we realized we were in the so-called wonderland. By 7:30 we were at the church, a nice building with an organ and a piano. Although we could not understand very much, we enjoyed the Spirit that prevailed there The Prophet bore powerful testimony of the Gospel It was a pleasure to listen to him We were also pleasantly surprised to encounter Br. Hall35 there. "Hello, Foekje," he said. After ten years he still remembered my name. We spoke sociably with him for a few moments and walked with him to the trolley. He well remembered everything from Holland

It was a wonderful evening. We enjoyed the lovely music and song.

Monday [June 14] I felt very tired and unwell because for the fourth time I missed my period when the 14th came around.

Tuesday [June 15] it was very warm again. I did the wash early and ironed in the afternoon and did some sewing. My upper body is covered with a rash and looks very red and itches horribly. O, it's so awful. It makes me think of the time Annie was about to be born Yesterday evening a woman peddler came by: I bought a morning robe [or housecoat] from her for 2.25.

Now it is Wednesday and lessening a little, luckily not so warm. A peddler has just been here and I have bought a skirt for 2 and a blouse for 1 dollar, underwear for Bert for 2.50. He was a happy man. It doesn't seem possible I could buy so much, but because until now we haven't had to pay any rent I can buy a few things with that money. 36

I discover that, although everything has become more expensive since Willem lived here, I can do more with 20 dollars than in Holland.

33 "Moeder" in the diary is always Albert's widowed mother.

34 My mother's sense of a kinship between Friesian and English is sound: Friesian has close ties with Anglo-Saxon, ancestor of modern English

35 An American who had served a Mormon mission in Holland

36 Mother's brother Koo, the landlord, arranged a moratorium

316 Utah Historical Quarterly

What a joy it will be when the time comes that we can pay our debts

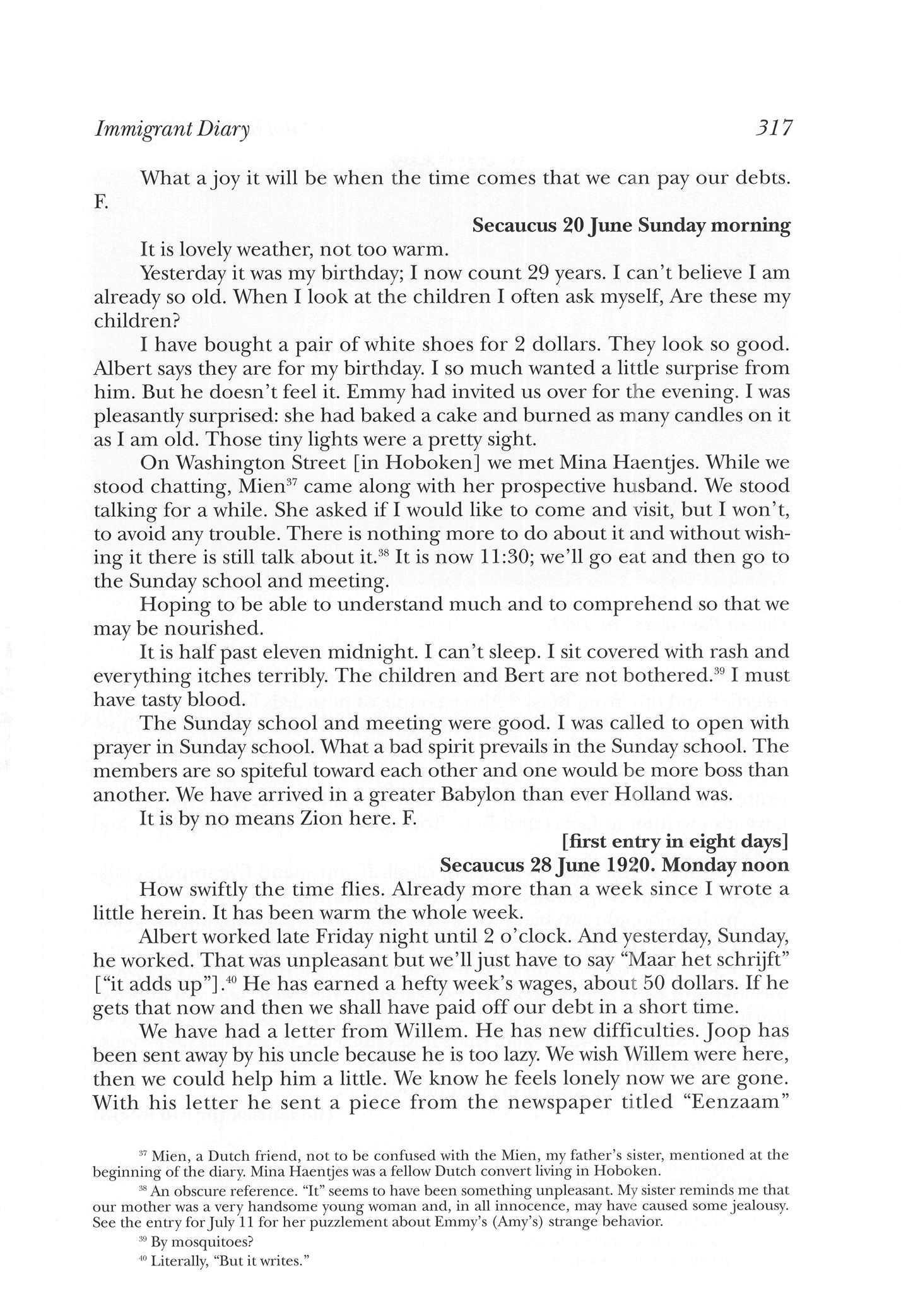

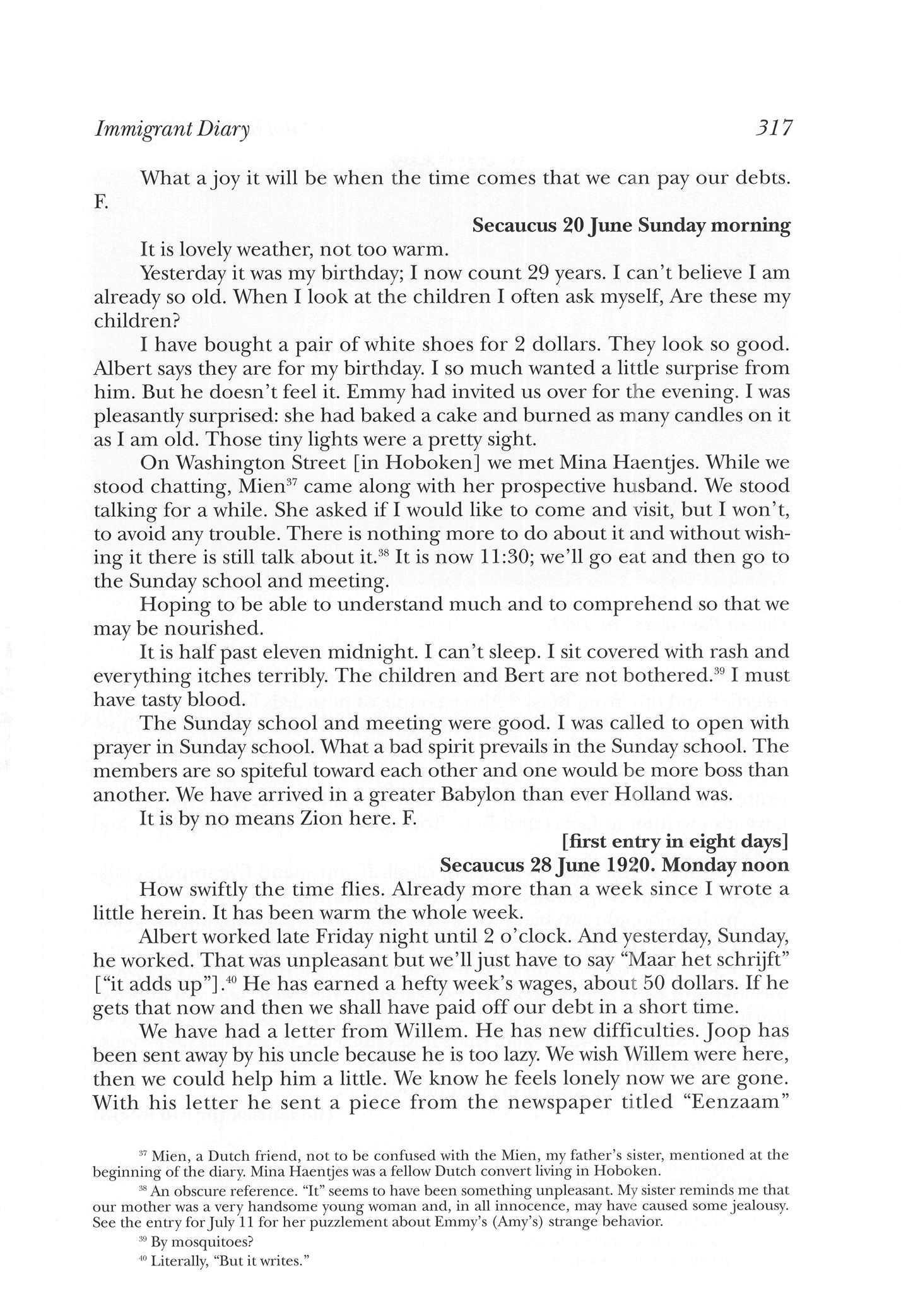

Secaucus 20 June Sunday morning

It is lovely weather, not too warm.

Yesterday it was my birthday; I now count 29 years. I can't believe I am already so old. When I look at the children I often ask myself, Are these my children?

I have bough t a pair of white shoes for 2 dollars They look so good Albert says they are for my birthday I so much wanted a little surprise from him. But he doesn't feel it. Emmy had invited us over for the evening. I was pleasantly surprised: she had baked a cake and burned as many candles on it as I am old. Those tiny lights were a pretty sight.

O n Washington Street [in Hoboken] we met Mina Haentjes. While we stood chatting, Mien37 came along with her prospective husband. We stood talking for a while. She asked if I would like to come and visit, but I won't, to avoid any trouble. There is nothing more to do about it and without wishing it there is still talk about it.38 It is now 11:30; we'll go eat and then go to the Sunday school and meeting.

Hoping to be able to understand much and to comprehen d so that we may be nourished.

It is half past eleven midnight. I can't sleep. I sit covered with rash and everything itches terribly. Th e children and Bert are not bothered. 39 1 must have tasty blood.

The Sunday school and meeting were good. I was called to open with prayer in Sunday school. What a bad spirit prevails in the Sunday school. The members are so spiteful toward each other and one would be more boss than another. We have arrived in a greater Babylon than ever Holland was.

It is by no means Zion here F

[first entry in eight days]

Secaucus 28 June 1920. Monday noon

How swiftly the time flies. Already mor e than a week since I wrote a little herein. It has been warm the whole week.

Albert worked late Friday night until 2 o'clock. And yesterday, Sunday, he worked. That was unpleasant but we'll just have to say "Maar het schrijft" ["it adds up"] . 40 H e has earned a hefty week's wages, about 50 dollars. If he gets that now and then we shall have paid off our debt in a short time.

We have had a letter from Willem. H e has new difficulties. Joo p has been sent away by his uncle because he is too lazy. We wish Willem were here, then we could help him a little. We know he feels lonely now we are gone. With his letter h e sent a piece from the newspape r titled "Eenzaam"

37 Mien, a Dutch friend, not to be confused with the Mien, my father's sister, mentioned at the beginning of the diary Mina Haentjes was a fellow Dutch convert living in Hoboken

38 An obscure reference. "It" seems to have been something unpleasant. My sister reminds me that our mother was a very handsome young woman and, in all innocence, may have caused some jealousy. See the entry for July 11 for her puzzlement about Emmy's (Amy's) strange behavior

39 By mosquitoes?

40 Literally, "But it writes."

Immigrant Diary 317

F

["Lonely"].41 That says enough for us. We have also had a letter from Geertje42 and one from Betsy.43 Also a couple of postcards for Ann and Wim. This morning we received a letter from B[rother] Van Or [den]44 and three postcards from Jouk45 and the children. I was happy to receive them. She has received our first letter. I was just about to post a letter to them, so I have written on the outside of the envelope that we had just received the cards. I have also written to Geert and Bets. Tonight we shall write to Mother and Mien.

Writing! It still bothers me most of all. If you spend five minutes talking with each other you can say more than in writing

We have bought two beds, two bedsteads with springs and mattress costing us 70 [90?] dollars Such things are indeed expensive

Yesterday I went to Sunday school with the children and then home I was asked to recite the 13th Article of Faith. It went well. O, I am eager to learn English It will be grand when I do On our way to Sunday school we ran into Jo and Riek Muuse and, since it was still early, we went to their house for a few moments

We long to hear something from Mother F

[no entries for two weeks]

41 Again, an obscure reference Had we read the diary in my mother's lifetime, she could have explained Willem's "difficulties."

42 Mother's youngest sister

43 The friend in Haarlem

44 A fellow LDS convert in Haarlem.

45 Joukje, mother's eldest sister

318 Utah Historical Quarterly

The immigrant Mulderfamily at ease at Bear Mountain in the Catskills, afavorite Hudson River retreat, ca. 1921.

Secaucus 11 July 1920 Sunday morning

How the time does fly. Soon when I have the [whole] house for my own the time will go even more quickly because I'll have so much to keep me busy. The past week was a good one for us because we received a letter from Mother and Mien And a letter from Willem, yesterday a card from Freek.46 Monday it was a holiday here [4th of July] and there was no going to work We were going to go sailing with Koo but he didn't come. He went sailing just with Emy and was to pick us up later but his pump broke down so nothing came of it I'm not sure how to take Emy sometimes; she seems jealous that Koo should come to us I wish Koo were still entirely free, then everything would be fine again. Now he often doesn't know what bothers Emy when she is so strange. So on the holidayjust the four of us [parents and two children] went out To New York, visited the aquarium and by elevated to Central Park How beautiful it is and so immense We saw only a small part of it. We also saw the deer. That area resembles Artis,47 only much bigger and everything free. Rich and poor can enjoy themselves there.

Wherever we are and we see various things I always wish our dear ones could be with us to see what we see

How long will it be before we see even one of them again? We don't know. Patient waiting and hoping all will come out well. O. I long so often for just a glimpse of them We have written a reply right away to Mother and Willem

Yesterday afternoon the Muuse boys were here with Uldrik. They swam in the river Albert was near them in a sailboat with the children They like it here We enjoy the friendship of the family Muuse

Albert is now a painter's helper. Koo is working in the shop for himself. We hope he will have lots of work.48 F [end of diary]

In 1926 the family, now numberin g six, with in addition a Mollie Higginson, a British convert who ha d becom e enamore d of my parents while on a mission in the Eastern States, set out for Salt Lake City in a four-cylinder, seven-passenger, secondhan d Willys-Knight, forming a little caravan in company with the secondhan d Hudso n Super Six driven by my uncle William Hooft, who ha d married Geertje and was making the move west with their two children an d a Swiss sister from the mission. (Hooft got some notoriety as "Big Bill" for Wonder Bread's "long loa f when he worked for the m in Salt Lake before the depression uproote d hi m an d sent hi m to Winnemucca , wher e h e started the still flourishing Winnemucca Bakery.) Trekking west by car

46

47 A park in Holland

48

Immigrant Diary 319

A relative or friend in Holland

Koo (UncleJohn) started his own plumbing business with a workshop behind the Meadow Lane cottage Albert eventually found work as a pressman in his trade, as noted above, with Van Rees Press in Manhattan

was an uncommon adventure when Route 30, the celebrated Lincoln Highway, was a primitive two-lane transcontinental road still under construction.

After a discouraging few years, which included a brief trial as a Fuller Brush salesman and a series of stints in job printing ("Salt Lake is not a printing town," he said), my father found success, first with Paragon Printers, then later with Stevens and Wallis, and finally a small partnership of his own called Mercury Printers. He was a popular figure in the Dutch community for his humorous songs and dramatic recitations, and he sang second tenor with the Swanee [sic] Singers, a men's chorus, for many years.

In all the years of struggle, my mother, renamed Fannie (the diary tells us when she learned that her Dutch name sounded "improper" in American ears), ever anxious about debt (she abhorred installment buying), worked at various tasks to supplement the family income, from door-to-door selling of one product or another and doing housework (even in her sixties) to conducting genealogical research for paying patrons. She answered every call of ward or stake in a range of offices in Primary, Relief Society, and the Genealogical Society and won a reputation as an angel of mercy, a peacemaker, a pillar of faith in the LDS community. The husband who seemed at one point in the diary to be a "closed book" to her was affectionate and loyal but inflicted the greatest pain of her life when he "fell away" from the church, attracted by the occult claims of the "I Am" and related

320 Utah Historical Quarterly

The four Mulder children shortly before the family's departure for Salt Lake City in 1926: standing, William, Anne, and Mary; seated, Al.

esoteric movements. I recall how fascinated he was by Francis Darter's numerology of the Great Pyramid. His disaffection was my mother's greatest trial, but she remained by his side, as steadfast in her support of him as she was in her own faith. They achieved a golden wedding anniversary and they remained united in their memories of Holland. They did, in fact, make a return sea voyage to the fatherland in 1955 and practiced the native tongue with their relatives and survivors among their friends of yesteryear. After father's death in 1963 my mother made three visits of her own by air, one accompanied by her eldest daughter, the Annie of the diary, who had married LeRoy Glissmeyer and raised a family of her own. My father died a few days short of his seventy-third birthday. His widow did not think she could last a year, but she outlived him by nearly fourteen years, the center of a growing circle of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Immigrant Diary 321

Lambs of Sacrifice: Termination, the Mixed-blood Utes, and the Problem of Indian Identity

BYR. WARREN METCALF

I N 1954 THE BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS ATTEMPTED to implement policies that would halt federal supervision and trust responsibilities over several tribes of American Indians These new policies, collectively known by the rather ominous sounding name "termination," followed the will of Congress as expressed in House Concurrent Resolution 108. Passed in the preceding year, this document succinctly stated the determination of Congress to make Indians subject to the same laws and privileges as other U.S. citizens and to "end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all of the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship." The resolution further declared that all of this was to be accomplished "as rapidly as possible."1

In due course, more than a hundred tribal groups would be subjected to the termination process The question of how the mixedblood Utes of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation of Utah came to be terminated is the subject of this study. These people were members, for the most part, of the Uintah band of the Ute Tribe. Their story is little known for several reasons—not the least being that scholars of American Indian history have not considered them sufficiently "Indian" to merit study. In this regard they are like other mixed-blood peoples who have been neglected simply because they do not fall within traditional areas of inquiry AsJennifer S H Brown recently pointed out, Anglo-American thought contains a deeply embedded kind of "racial dualism," which carries over into scholarly dichotomies of "Indian" and "white."2

The mixed-blood Ute story has also been neglected because it does not precisely fit the pattern in which Indians serve as the victims of the dominant culture, although it is true that Utah Senator

1 House Concurrent Resolution 108, U.S. Statutes at Large, vol 67, 1953

Dr Metcalf is an adjunct assistant professor of history at Idaho State University

2 Jennifer S H Brown, "Metis, Halfbreeds, and Other Real People: Challenging Cultures and Categories," The History Teacher 27 (November 1993): 21-2

Arthur V Watkins, one of the leading congressional proponents of termination, deserves the disproportionate responsibility for what happened to these people. However, it also remains true that the actual work of terminating the mixed-bloods fell to other Utes and their leaders, assisted by sympathetic BIA officials and even representatives of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). The unfortunate fact of the matter is that the mixed-blood Utes fell victim to the termination process largely as a result of the actions of other Indians and even the nominal defenders of Indian rights.

Moreover, the mixed-blood Ute story involves the kinds of controversies that scholars sometimes prefer to avoid: rivalries between tribal leaders, petty jealousies, distrust between tribal bands, and a bitter fight over tribal membership. This last point was especially exacerbated by the windfall of some $18 million received by the tribe as a result of successfully prosecuted claims cases against the United States. In short, what happened to the mixed-blood Utes defies many of the accepted interpretations of the termination era

The Utes at Uintah and Ouray received the news of the $18 million judgment in July 1950 when tribal claims attorney Ernest L. Wilkinson met with the tribe and explained the conditions of a settlement he had negotiated with the government. The situation was complicated by the fact that only two of the three Ute bands residing on the reservation, the Whiteriver and Uncompahgre bands, were party to the claims cases that produced the windfall award. This was so because these bands originally lived in Colorado and were removed to the Uintah Reservation in the aftermath of the 1879 Meeker Massacre. The claims cases derived from the value of the Colorado lands the

of Sacrifice 323

Lambs

U.S. Senator Arthur V. Watkins, fuly 1952. Salt Lake Tribune photograph in USHS collections.

Whiterivers and Uncompahgres lost when forced to relocate. The third band, the Uintah Utes, constituted the remnants of the several Ute bands that once resided in Utah and as a consequence had no legal claim to the judgment money.

Wilkinson knew that a hopeless tangle of lawsuits and countersuits would ensue should only two of the three bands share in the award, and so he engineered an agreement by which the two Colorado bands were compelled to share the money with the Utah Utes as a condition of the settlement. Naturally, this "share and share alike" arrangement engendered considerable resentment on the part of the Colorado Utes, but that was not all The Colorado bands had an additional reason to resent the Utah branch of the tribe: a large proportion of the Uintahs had intermarried with Indians of other tribes. Hence, in the 1950s context of the term, many of the Uintahs were "mixed-blood" Indians—descendants of different tribes.3

The mixed-blood issue contributed significantly to the controversy over who should share in the $18 million award—an argument that erupted during a period of experimentation and preparation for both tribal and governmental leaders In Washington, members of Congress debated and then embraced the philosophy of termination but left the actual task of creating terminal programs with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and tribal leaders. Bureau officials, meanwhile, heeded the legislative mandate of House Concurrent Resolution 108 and began collecting information about specific tribes deemed "capable" of assuming the responsibilities rendered by the federal government The huge Colorado judgment moved the Ute Tribe directly into this category, despite the fact that the tribe had previously been considered ill-prepared for termination. Suddenly tribal leaders found themselves subject to the demands of bureau and congressional policymakers, while tribal factions fought over control of the money. The ensuing disagreements reflected deep divisions within the tribe itself.

Ute tribal leaders initially proposed to spend some of the money on a three-year development program (approved by Congress as

3 According to statistics compiled by the BIA in 1954, only 4 percent of the 672 members of the Uncompahgre Band had one half or less Ute "blood" (to use the blood quantum definition employed by the bureau); less than 1 percent of the 308 Whiteriver Utes were one-half degree or less Ute, while more than half—52 percent—of the 785 Uintahs fell into this "mixed-blood" category See "Population Figures of the Enrolled Members of the Ute Indian Tribe, Uintah and Ouray Reservation, March 1954," RG 75, BIA, accession #57A-185, box 196, file 9639-52-075, National Archives, Washington, D.C

324 Utah Historical Quarterly

As termination philosophy matured into policy, these accumulated pressures threatened the fragile equilibrium that existed among the three Ute bands

Public Law 120 on August 21, 1951) to provide immediate relief for the poverty-stricken tribal members and to develop several experimental programs. Unfortunately, problems quickly emerged over the plan's objective and which tribal factions would benefit the most from it The plan itself offered something for almost everyone, including a per capita payment authorized by the secretary of the interior In October 1951 every enrolled member of the Ute Tribe received $1,000 in the form of an individual money account, subject to withdrawal upon the submission of a brief plan explaining how the funds would be used. The tribe offered very few restrictions on the money in the expectation that members would need the experience gained in handling large sums. According to Superintendent Forrest R. Stone, most of the Utes used the money to buy food and clothing and to pay old debts. He noted in his report to the bureau that almost every family bought an automobile or a truck, exercising "reasonably good judgment" in purchasing these vehicles, but added that there were also a "number of stupid transactions, both in the care that they have taken of their automotive equipment and the tendency to spread out in this direction far beyond their need."4

The per capita distribution continued out of tribal funds over the duration of the three-year program. Additional features of the plan included a program designed to add new land to the reservation and provide more grazing property, to survey the carrying capacity of tribal grazing lands, and to fund improvements on existing range lands through the construction offences, stock ponds, and other useful projects Other provisions of the program helped the members in a more personal way A revolving credit fund of $1 million was established to provide loans to individual members, complete with a rather conservative Tribal Credit Committee. A housing rehabilitation program helped to remodel or build more than a hundred homes, with much of the lumber coming from tribal forestry reserves. The program also made arrangements to close the Uintah day and boarding school at Whiterocks and to transfer the Ute children to public schools in the Uinta Basin. A Reservation School Board was established to assist in this process and to act as a liaison with the local school boards.5

The Ute Planning Division intended that the various provisions

5 Ibid

Lambs of Sacrifice 325

4 Forrest R Stone to Ralph M Gelvin, February 7, 1952, RG 75, BIA, accession #57A-185, box 196, file 9020, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

of the three-year program would further the development of the tribe as a whole and foster the "rehabilitation" of individual members. But all of these provisions—range enhancements, housing and credit programs, and involvement in the public schools—anticipated that participants would already possess a certain amount of experience in business, banking, and education. The assimilationist objectives of the program, therefore, made it inevitable that the most acculturated tribal members would be in a position to receive the greatest benefit from them. The per capita payment program formed the only exception to this general pattern, and government officials observed that the Utes took less interest in their farms, ranches, and off-reservation employment opportunities as a result of the tribal income. 6