<o to o C5 Or FSF! i i **\ ^ *v.~. v . <J#

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD O F EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City,1997

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1997

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City,1999

GENE A SESSIONS, Ogden, 1998

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1999

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end. Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5!4 or 3!4 inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

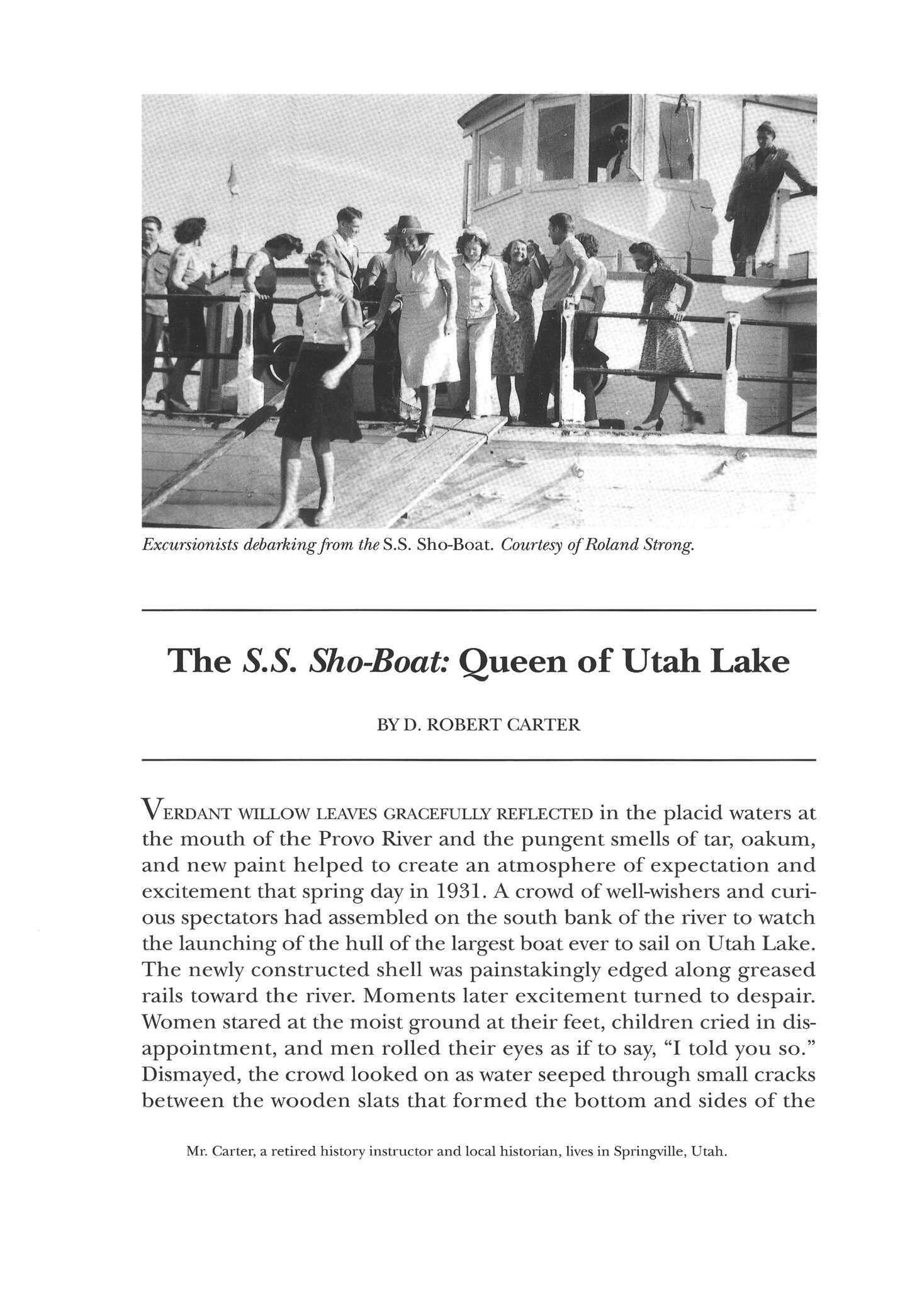

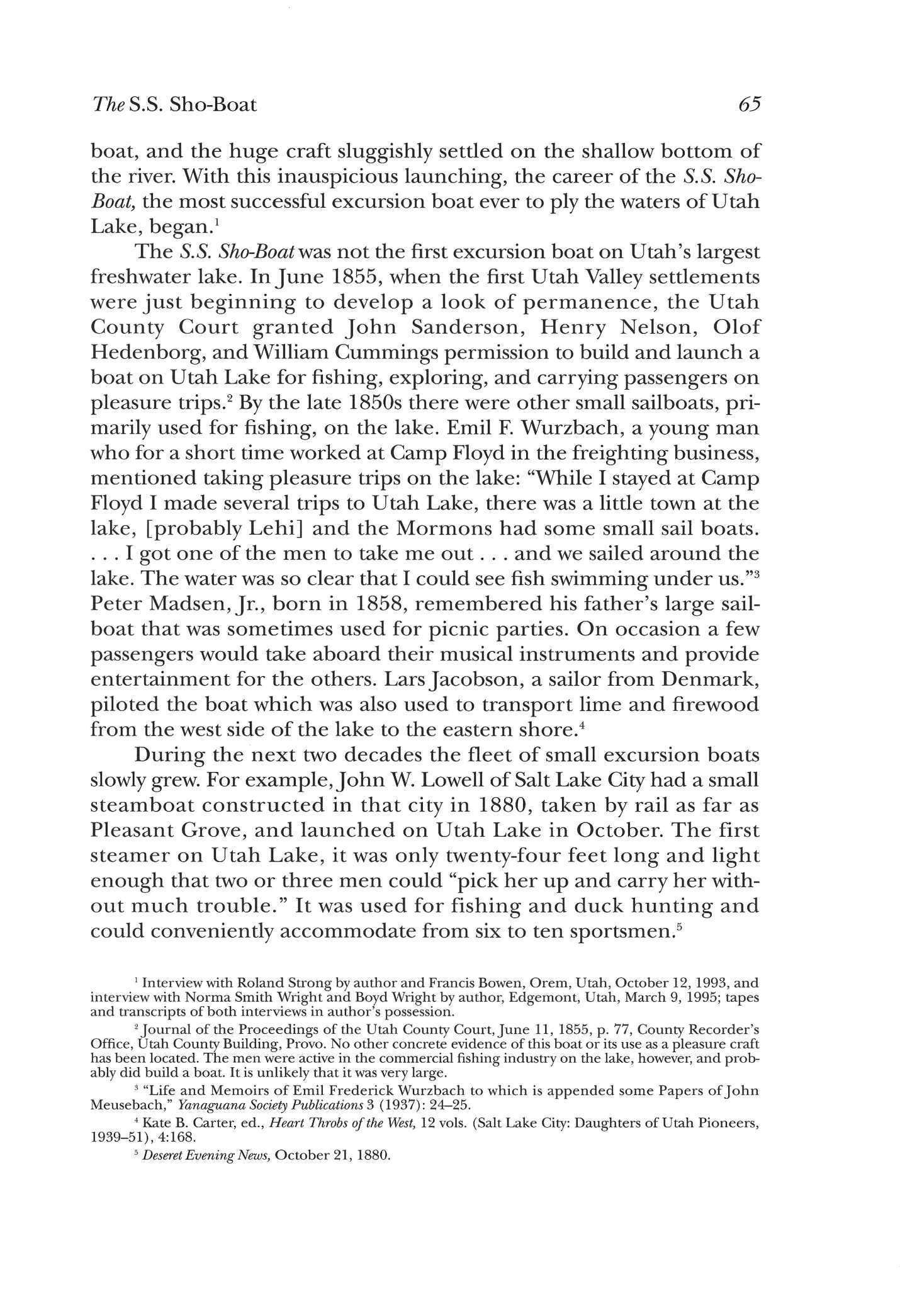

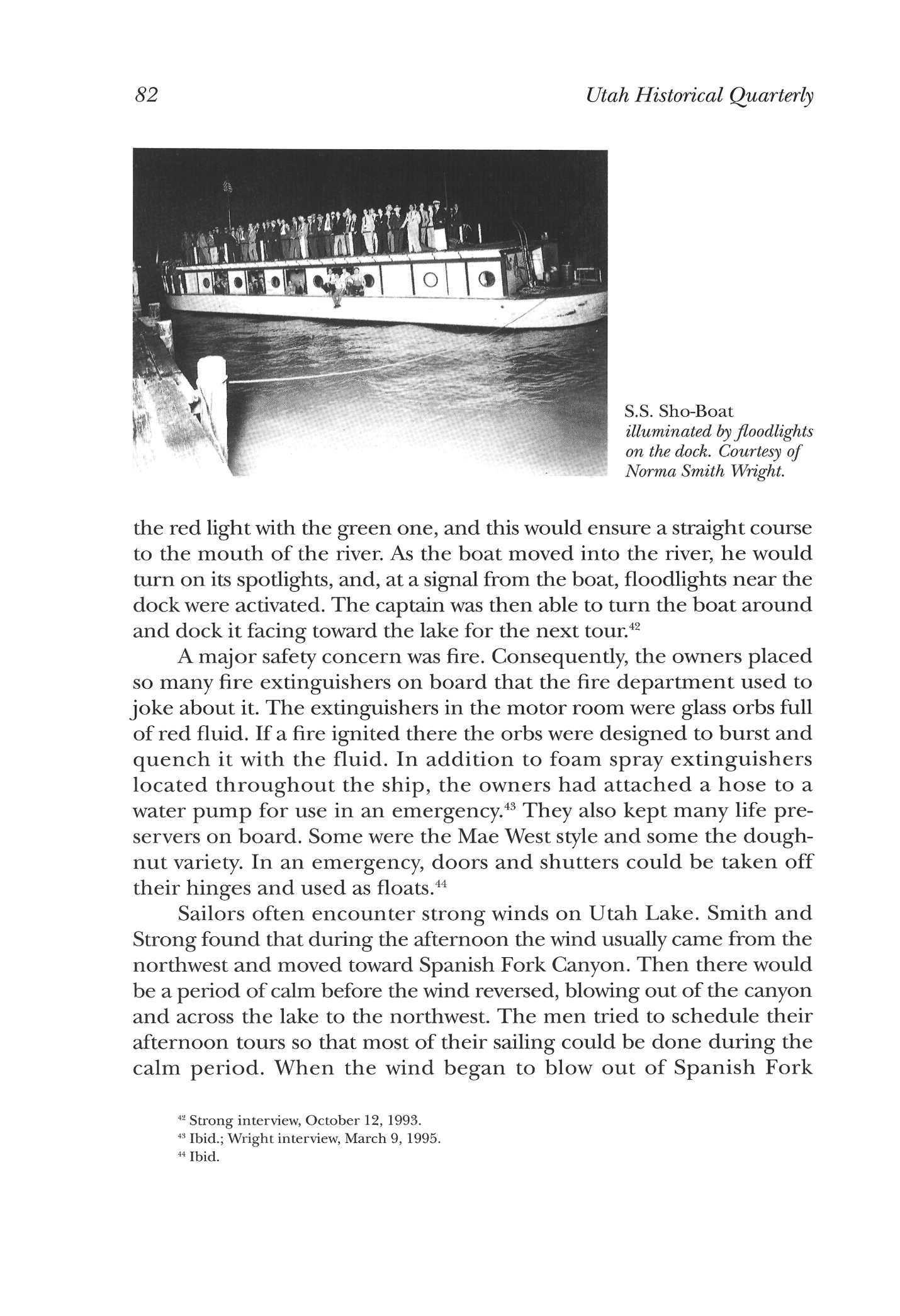

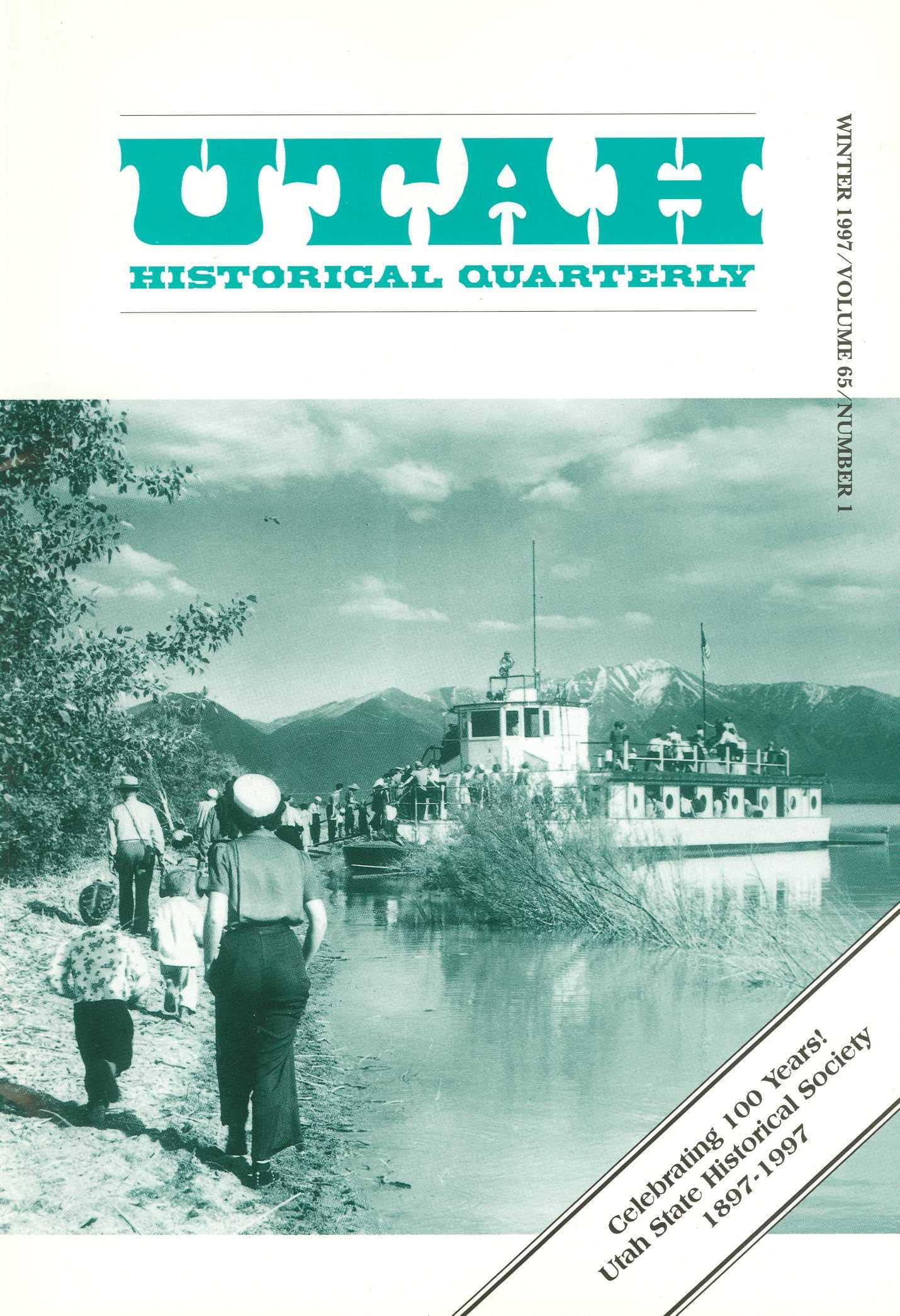

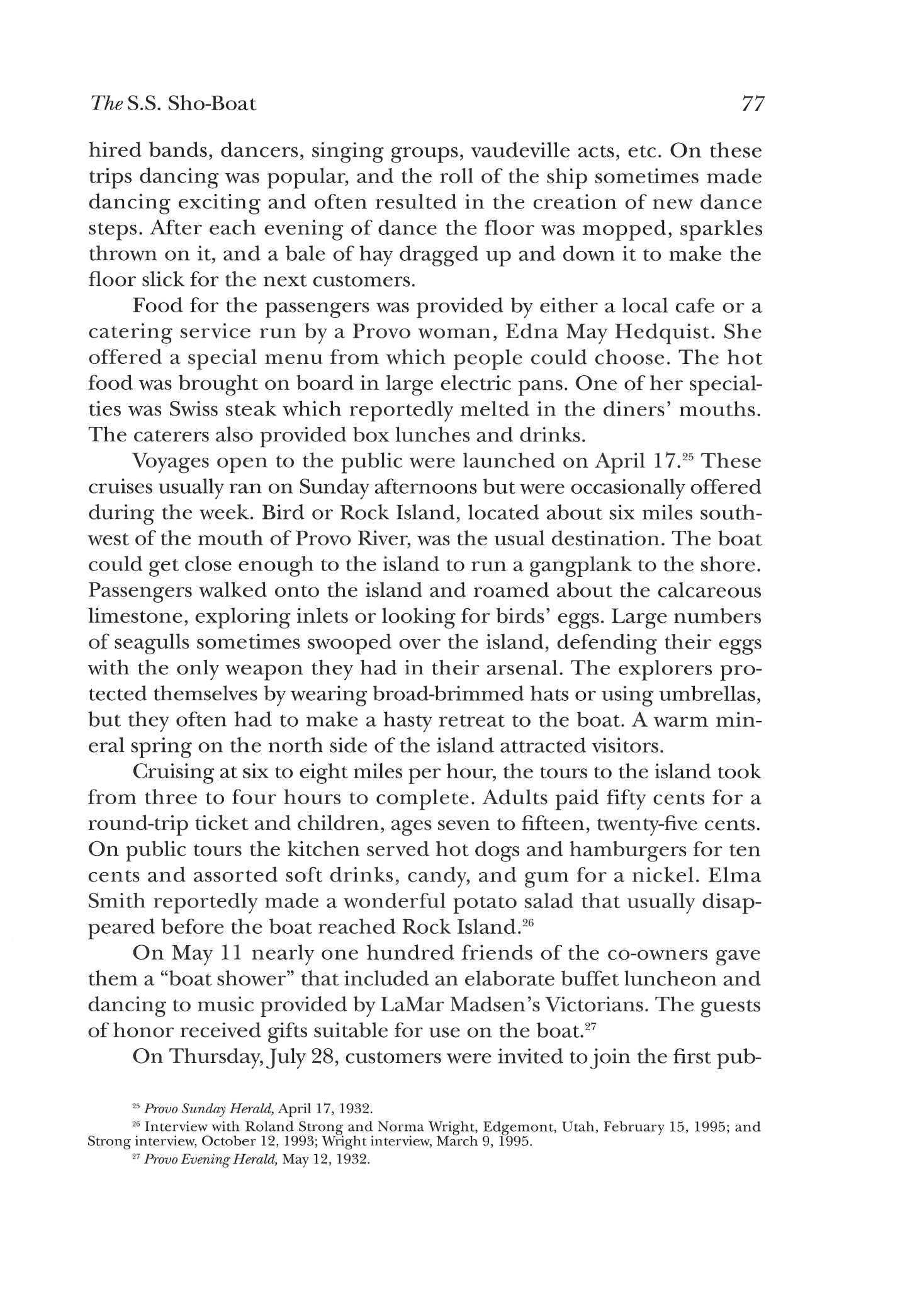

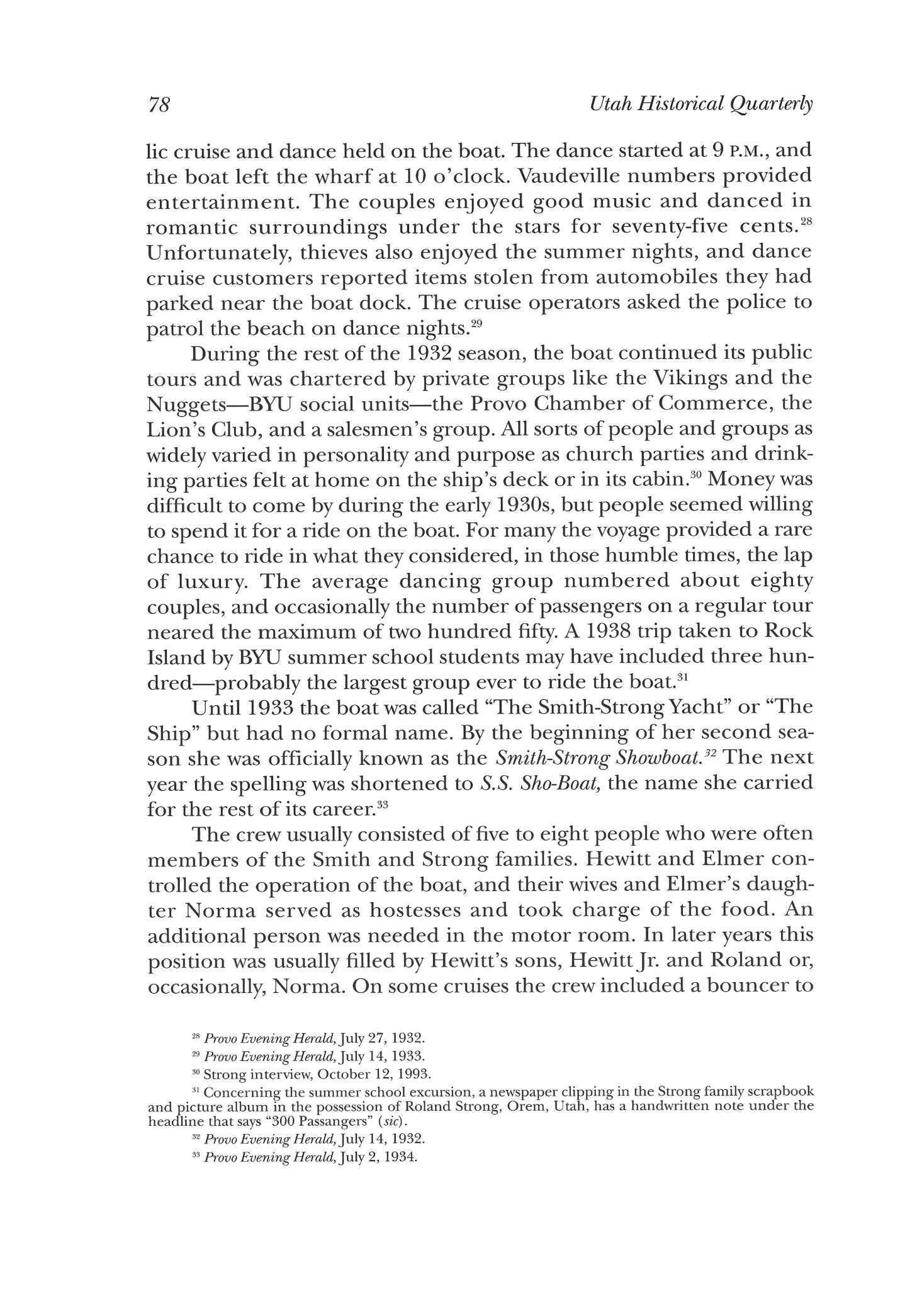

HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y Contents WINTER 1997 \ VOLUME 65 \ NUMBER 1 IN THIS ISSUE 3 HOWARD R. ANTES AND THE NAVAJO FAITH MISSION: EVANGELIST OF SOUTHEASTERN UTAH ROBERT S MCPHERSON 4 THE SENSATIONAL MURDER OFJAMES R HAYAND TRIAL OF PETER MORTENSEN CRAIG L. FOSTER 25 A COMMON SOLDIER AT CAMP DOUGLAS, 1866-68 CATHERINE H ELLIS 49 THE S.S. SHO-BOAT: QUEEN OF UTAH LAKE D. ROBERT CARTER 64 BOOKREVIEWS 88 BOOKNOTICES 95 THE COVER The S.S. Sho-Boat was the largest excursion vessel ever to operate on Utah Lake. She was designed, built, and operated by two Utah County men, Elmer Smith and Hewitt Strong, who loved the lake and loved to sail on it. Courtesy of Roland Strong. © Copyright 1997 Utah State Historical Society

WILLIAM B. SMART and JOH N TELFORD. Utah: A Portrait DELMONT R. OSWALD 88

THOMAS LYON and TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS, eds. Great and Peculiar Beauty: A Utah Reader JAMES M. ATON 89

FREDERICK S BUCHANAN Culture Clash and Accommodation: Public Schooling in Salt Lake City, 1890— 1994 ROGER H THOMPSON 90

BRIGITTE GEORGI-FINDLAY The Frontiers of Women's Writings: Women's Narratives and the Rhetoric of Westward Expansion RUSSELL BURROWS 91

ARTHUR KING PETERS. Seven Trails West STANLEY B. KIMBALL 92

JOH N S MCCORMICK AND JOH N R SILLITO, eds. A World We Thought We Knew: Readings in Utah History DENNIS L LYTHGOE 93

Books reviewed

In this issue

The Four Corners area seemed to cling to its frontier heritage much longer than most other regions of the West. Settled relatively late amidst some of the nation's most rugged terrain features, it remained inaccessible and uninviting in the minds of most potential visitors and homeseekers Yet, for those of a particular mindset—those seeking challenge and adventure— it presented grand opportunities. Such a man was Howard Antes. Making his way to the region near the turn of the century, this eccentric preacher sought to promote reform and economic improvement among the Navajos. In many ways his own worst enemy, Antes at different times and in a variety of ways alienated local ranchers, reservation officials, and many of the native peoples he tried so eagerly to help These dynamics, along with the man's singular triumph, are related in the first article.

During the same time, a remarkable drama was unfolding in Salt Lake City. James R Hay had just been murdered, and one of the most sensational trials in our state's history was soon to follow. Its extraordinary nature was heightened by questions of the validity of evidence claimed to have been received through divine revelation, therefore earning a special niche in judicial history Not until now, in our second selection, has the complete story been fully researched, completely analyzed, and finally told.

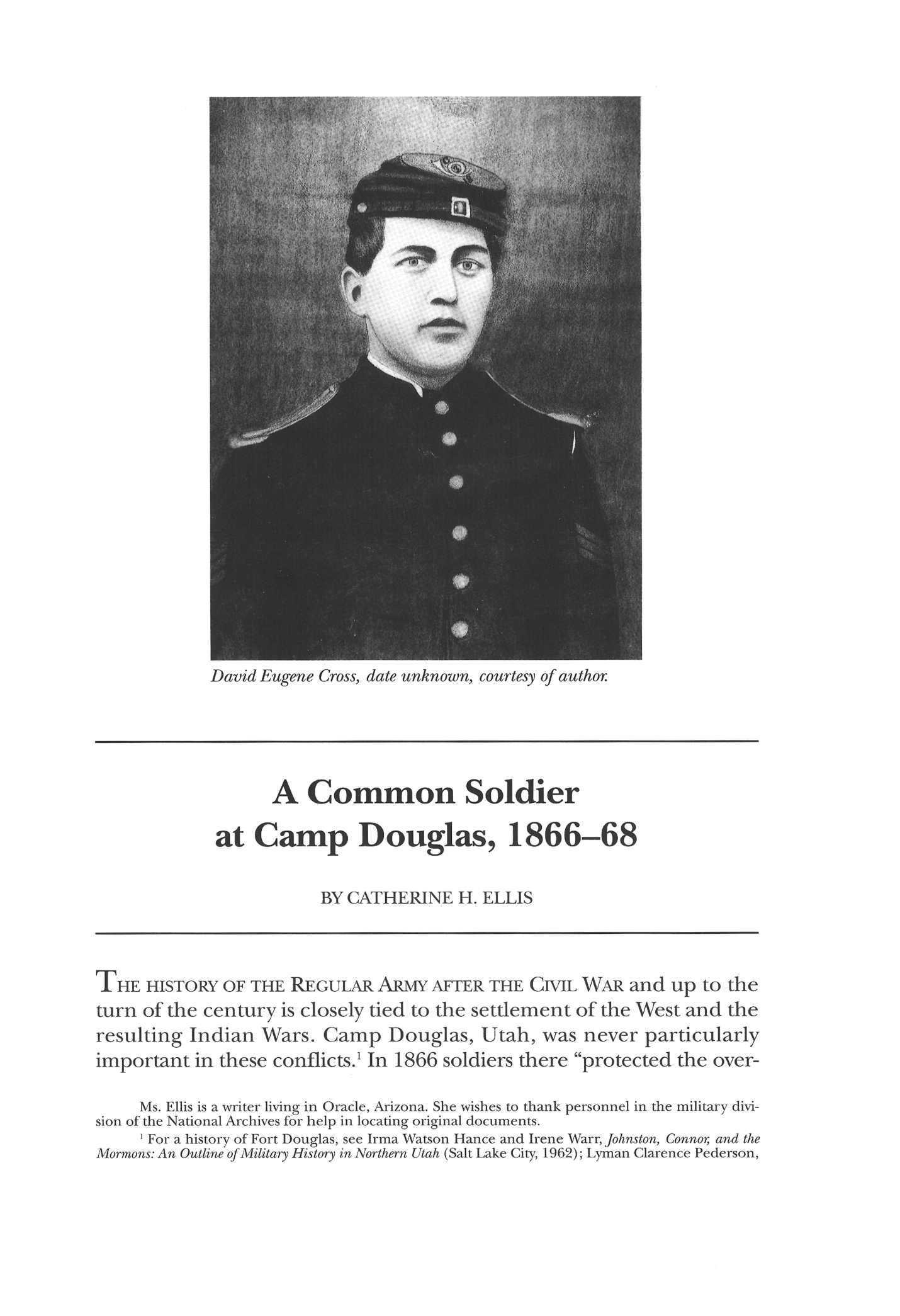

Next comes a small but engaging piece detailing the unlikely adventures of a soldier who deserted while assigned to duty at Fort Douglas following the Civil War. Much of the story comes from letters he wrote that have been preserved—quite uncommon for enlisted men of that time and circumstance The denouement is equally uncommon and is sure to leave the reader wearing at least the shadow of a smile

The final offering is a feel-good account of enterprise and success begun during the Great Depression The S.S. Sho-Boat, designed and built by two local entrepreneurs, provided entertainment and escape to thousands of people who paid a quarter or two for a scenic or romantic excursion across the waters of Utah Lake. The story will not only rekindle old memories for a few and serve as a testament to the entrepreneurial spirit for others but will also remind us all that there is nothing wrong with a bit of old-fashioned nostalgia now and then.

i V

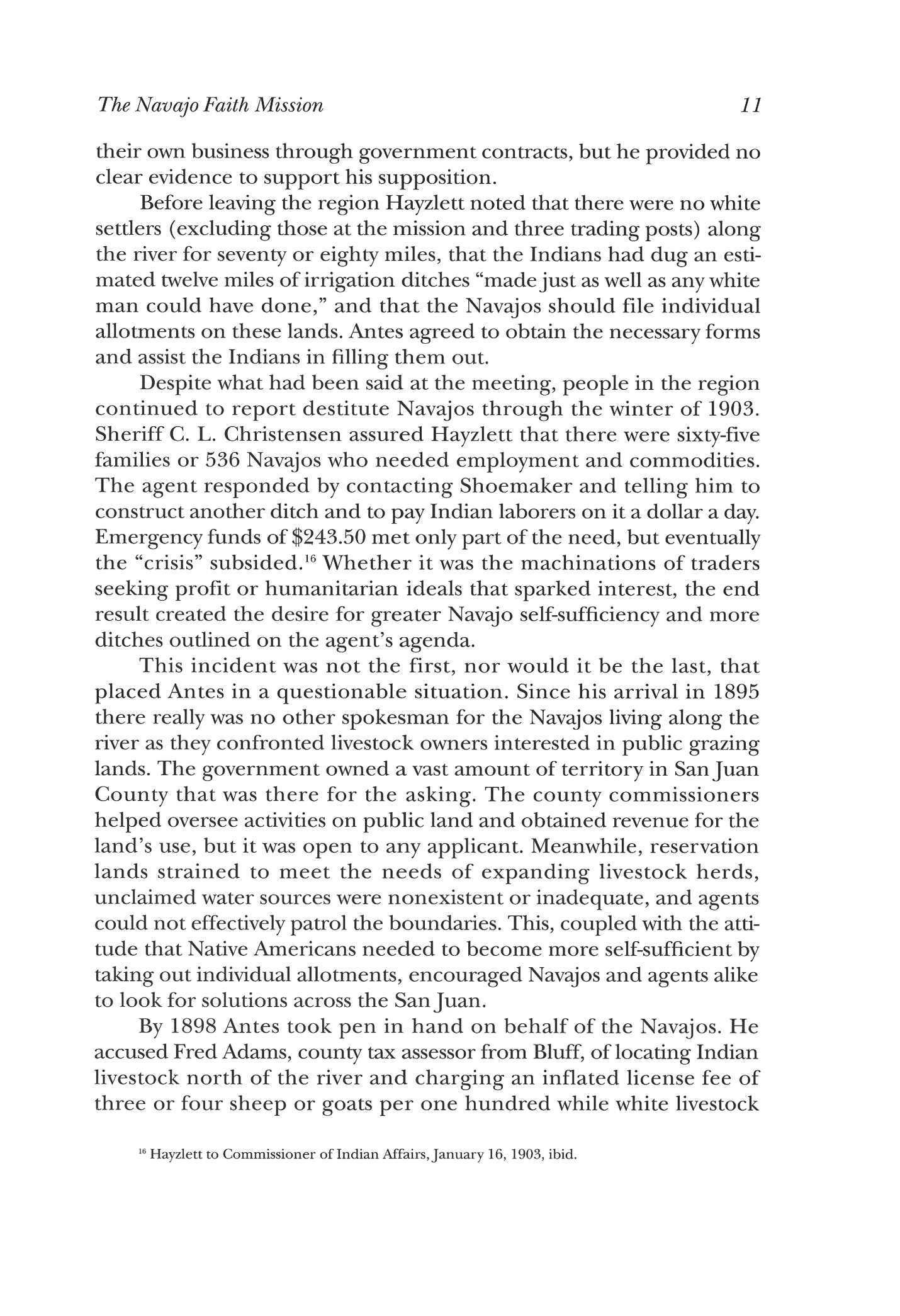

"Looking south across the San Juan River from Navajo Faith Mission, Aneth, Utah, 1901." Photograph by Charles Goodman.

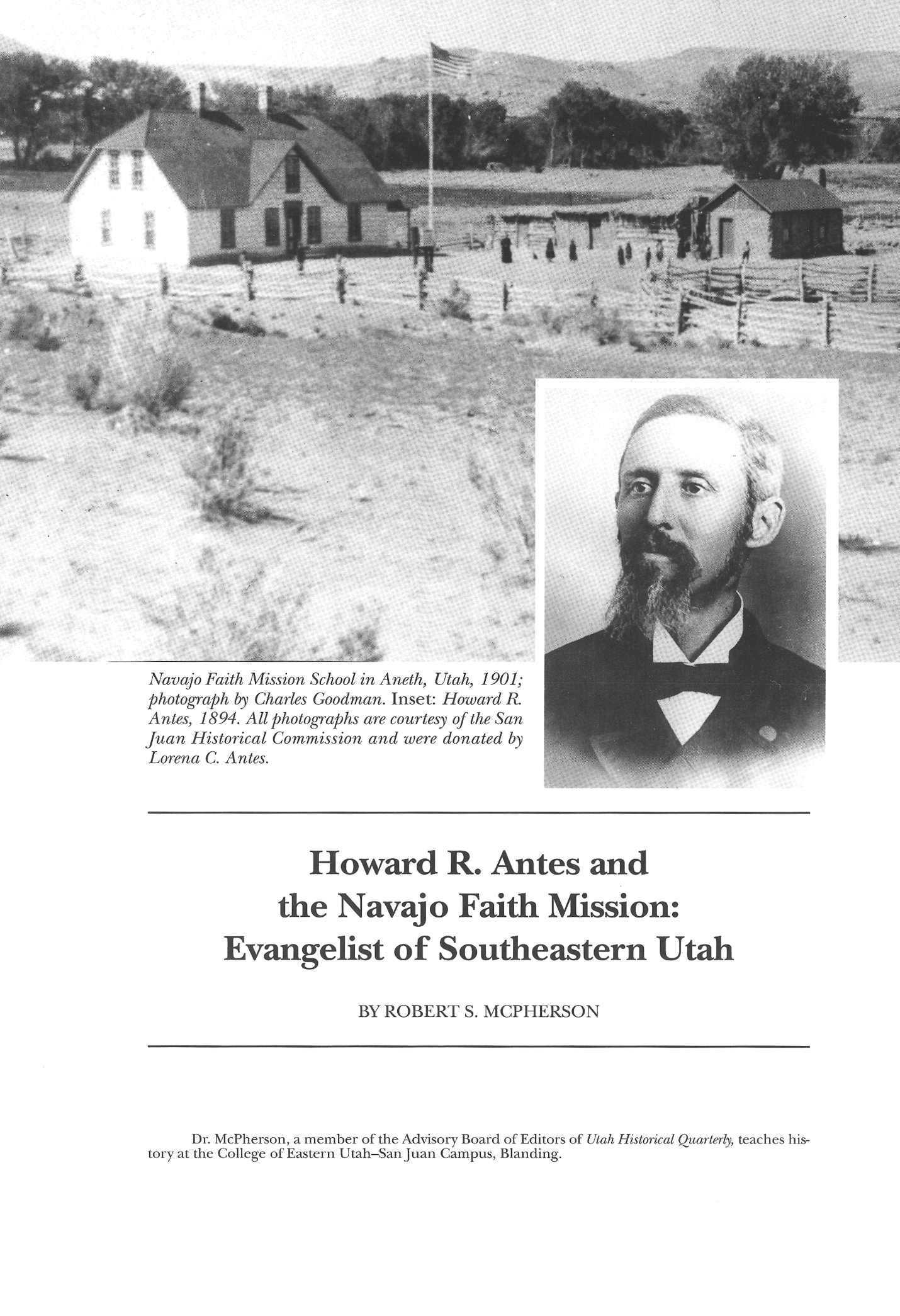

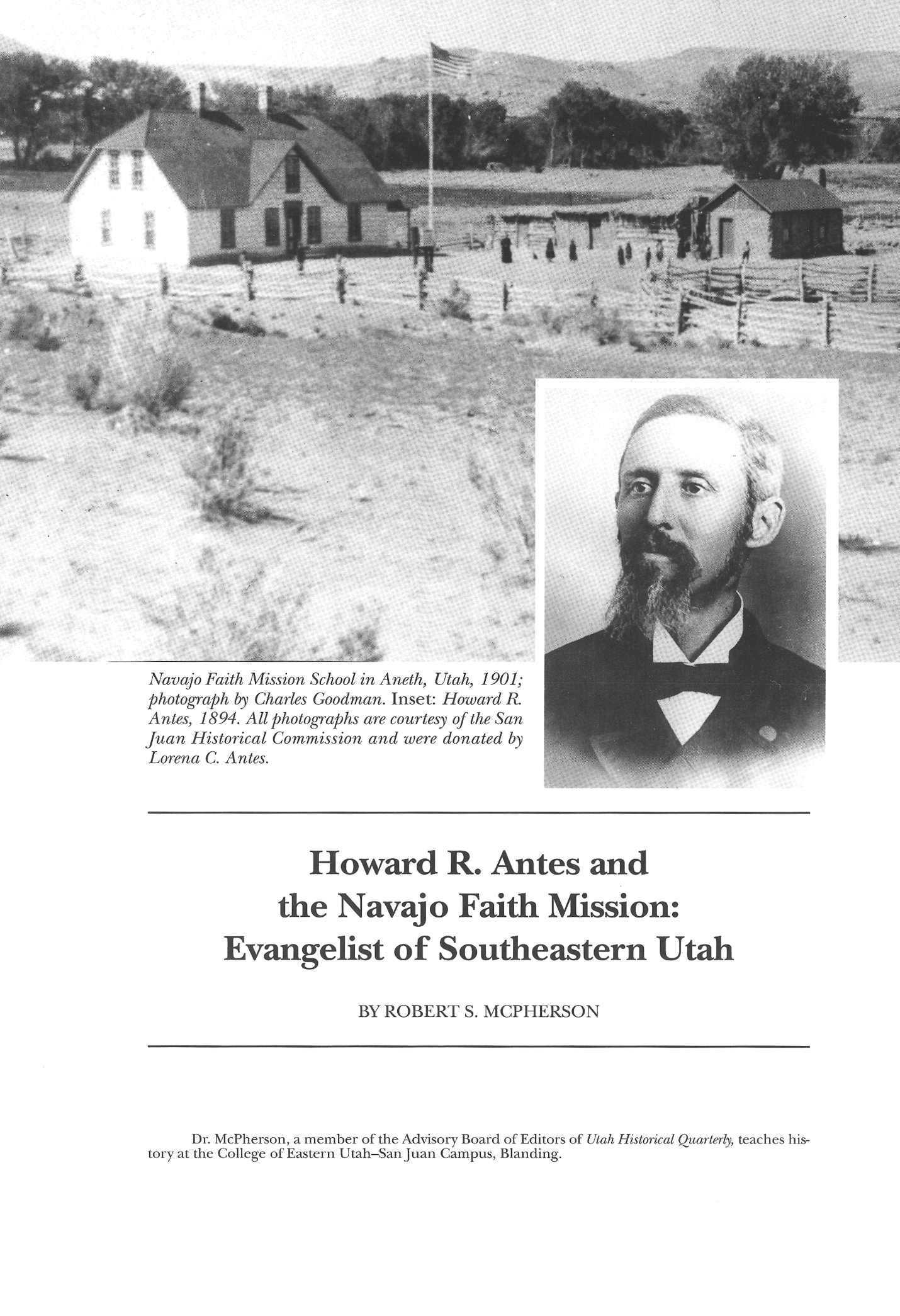

Navajo Faith Mission School in Aneth, Utah, 1901; photograph by Charles Goodman. Inset: Howard R. Antes, 1894. All photographs are courtesy of the San Juan Historical Commission and were donated by Lorena C. Antes.

Howard R, Antes and the Navajo Faith Mission: Evangelist of Southeastern Utah

BYROBERT S MCPHERSON

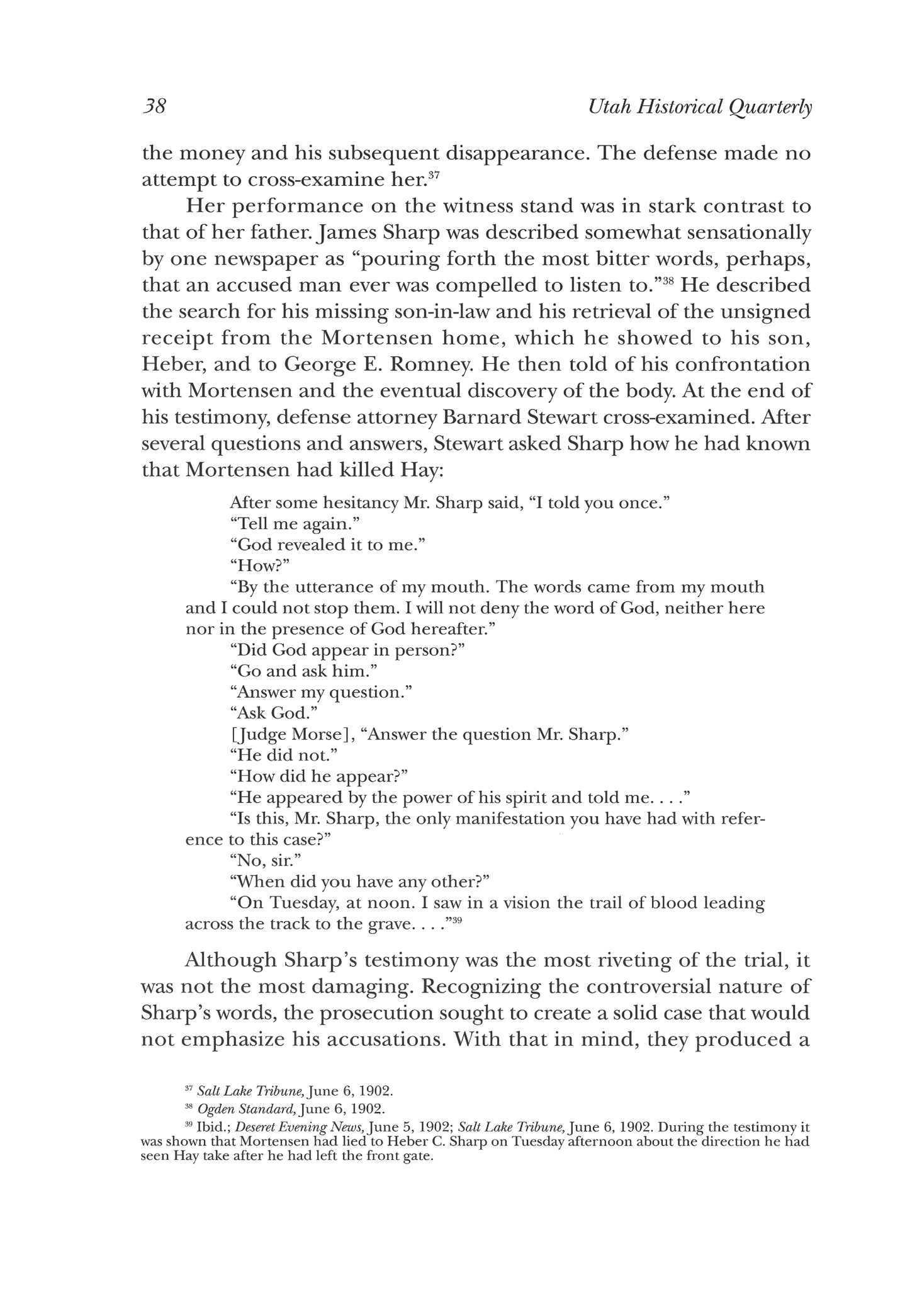

Dr McPherson, a member of the Advisory Board of Editors of Utah Historical Quarleiiy, teaches history at the College of Eastern Utah-San Juan Campus, Blanding

BYROBERT S MCPHERSON

Dr McPherson, a member of the Advisory Board of Editors of Utah Historical Quarleiiy, teaches history at the College of Eastern Utah-San Juan Campus, Blanding

IN 1890 THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OFFICIALLY PROCLAIMEDthe American West settled, the frontier epoch in United States history closed. Native Americans surviving the westward movement had been relegated to a reservation system and a "civilizing" process designed to eventually end Indian culture In the East there arose a growing number of white advocates of various programs for Indian people, but only a few of these reformers actually lived and worked in the West. One person who put his sentiments into action was a Methodist missionary named Howard Ray Antes who, with his wife Evelyn (Eva), settled along the San Juan River in the Four Corners area of southeastern Utah.

Born on October 20, 1850, in Homewood, Illinois, Antes received his training for the clergy in the East before moving to Colorado. His early years of ministry speak of a person dissatisfied with his lot in life—in 1887 he started with a church in Windsor, Colorado; in 1889 he served as a missionary to the Navajo in New Mexico; from 1890 to 1893 he was back in Colorado laboring in the Florence Circuit; in 1894 he preached in Glenwood Springs, Colorado; and a year later he requested to be on his own as a nonsectarian minister.1

Yet this record of ill-fated starts belonged to a man with unshakable principle and zeal. In fact, his zeal was probably the cause of his undoing in these early assignments. Described as an "old fashioned Methodist minister," he was a "holiness preacher" who emphasized a strict interpretation of biblical tenets. Drinking, gambling, and womanizing were sins unacceptable to his beliefs, though his parishioners desired a more liberal approach to ethical behavior. He faced the demands of his congregation head on, refused to change his ways, and chose instead to move on. 2

Howard and Eva Antes came to the San Juan River country armed with almost puritanical faith. Writing in a self-published newspaper called The Navajos Evangel, Antes told of electing not to be tied to any particular denomination in order to be "entirely free to wholly followJesus."3 "Literal obedience" to the commandments and a "prac-

5

1 Paul Millette, archivist, Iliff School of Theology, to author, July 28, 1993.

- Telephone conversation with Lorena Antes, June 18, 1991

3 Howard R Antes, The Navajos Evangel, October 1901, pp 1-2

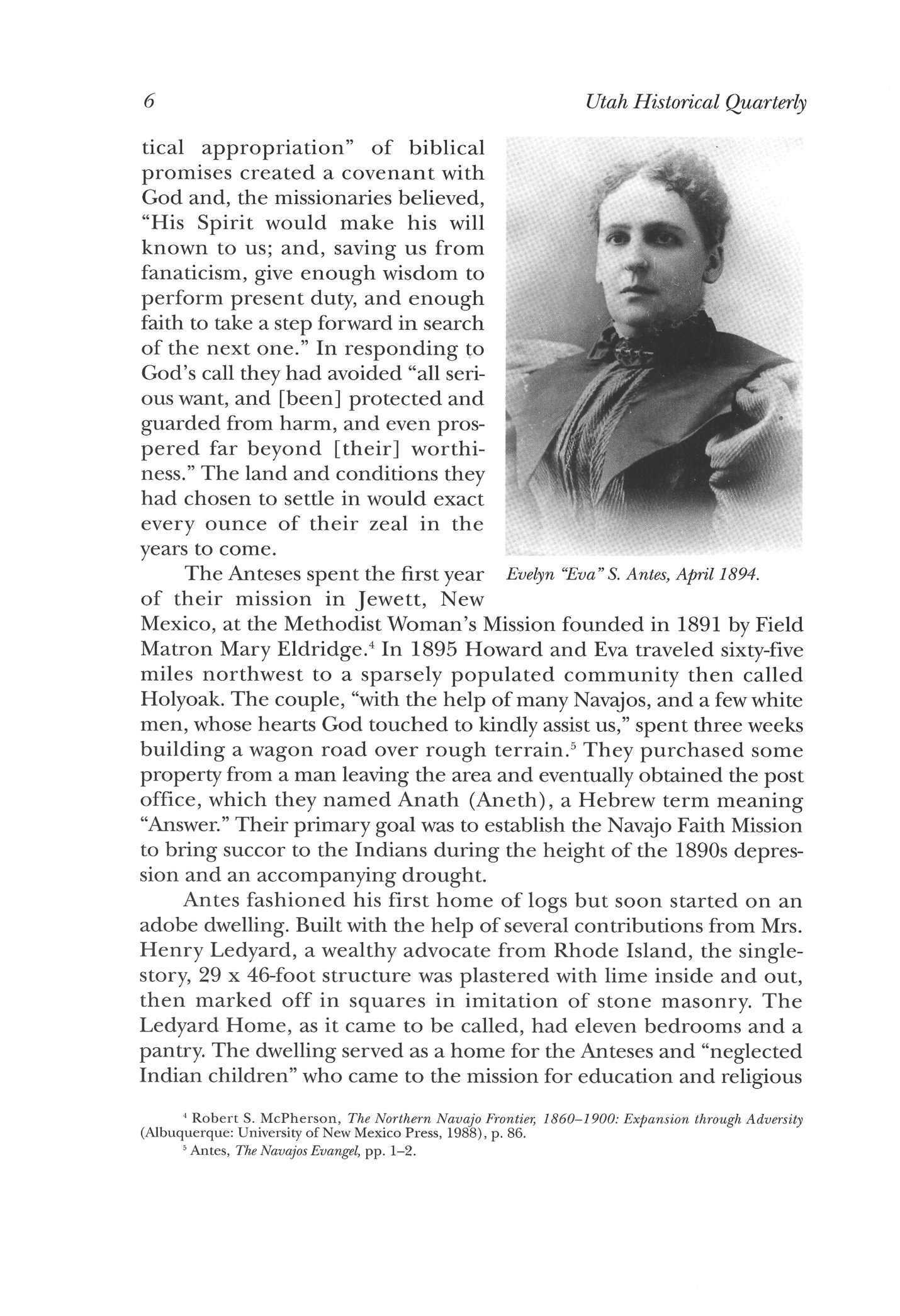

tical appropriation" of biblical promises created a covenant with God and, the missionaries believed, "His Spirit would make his will known to us; and, saving us from fanaticism, give enough wisdom to perform present duty, and enough faith to take a step forward in search of the next one." In responding to God's call they had avoided "all serious want, and [been] protected and guarded from harm, and even prospered far beyond [their] worthiness." The land and conditions they had chosen to settle in would exact every ounce of their zeal in the years to come.

The Anteses spent the first year of their mission in Jewett, New Mexico, at the Methodist Woman's Mission founded in 1891 by Field Matron Mary Eldridge.4 In 1895 Howard and Eva traveled sixty-five miles northwest to a sparsely populated community then called Holyoak. The couple, "with the help of many Navajos, and a few white men, whose hearts God touched to kindly assist us," spent three weeks building a wagon road over rough terrain. 5 They purchased some property from a man leaving the area and eventually obtained the post office, which they named Anath (Aneth), a Hebrew term meaning "Answer." Their primary goal was to establish the Navajo Faith Mission to bring succor to the Indians during the height of the 1890s depression and an accompanying drought.

Antes fashioned his first home of logs but soon started on an adobe dwelling Built with the help of several contributions from Mrs Henry Ledyard, a wealthy advocate from Rhode Island, the singlestory, 29 x 46-foot structure was plastered with lime inside and out, then marked off in squares in imitation of stone masonry. The Ledyard Home, as it came to be called, had eleven bedrooms and a pantry. The dwelling served as a home for the Anteses and "neglected Indian children" who came to the mission for education and religious

6 Utah Historical Quarterly

Evelyn "Eva"S. Antes, April 1894.

4 Robert S. McPherson, The Northern Navajo Frontier, 1860-1900: Expansion through Adversity (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988), p 86

5 Antes, The Navajos Evangel, pp 1-2

The Navajo Faith Mission

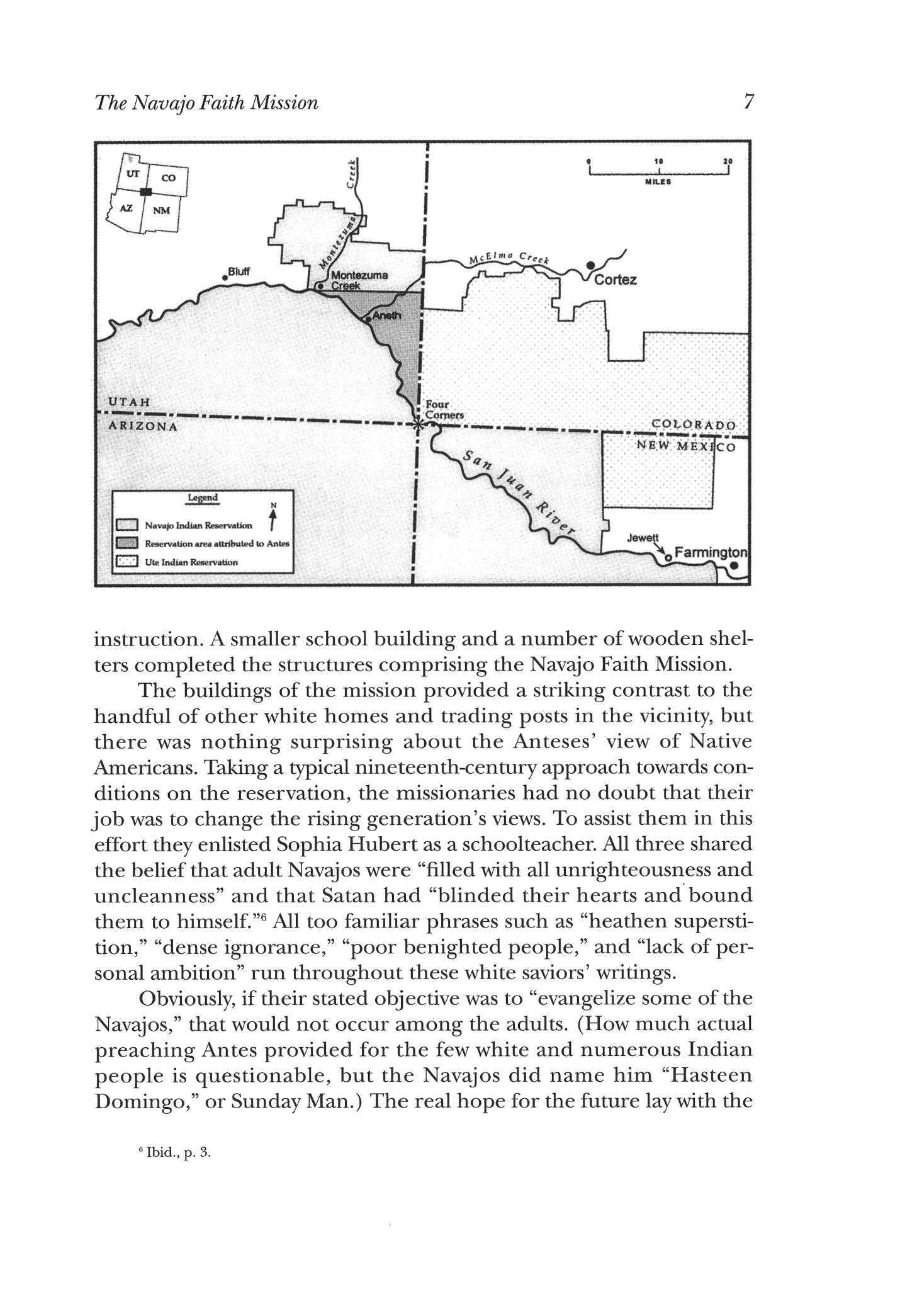

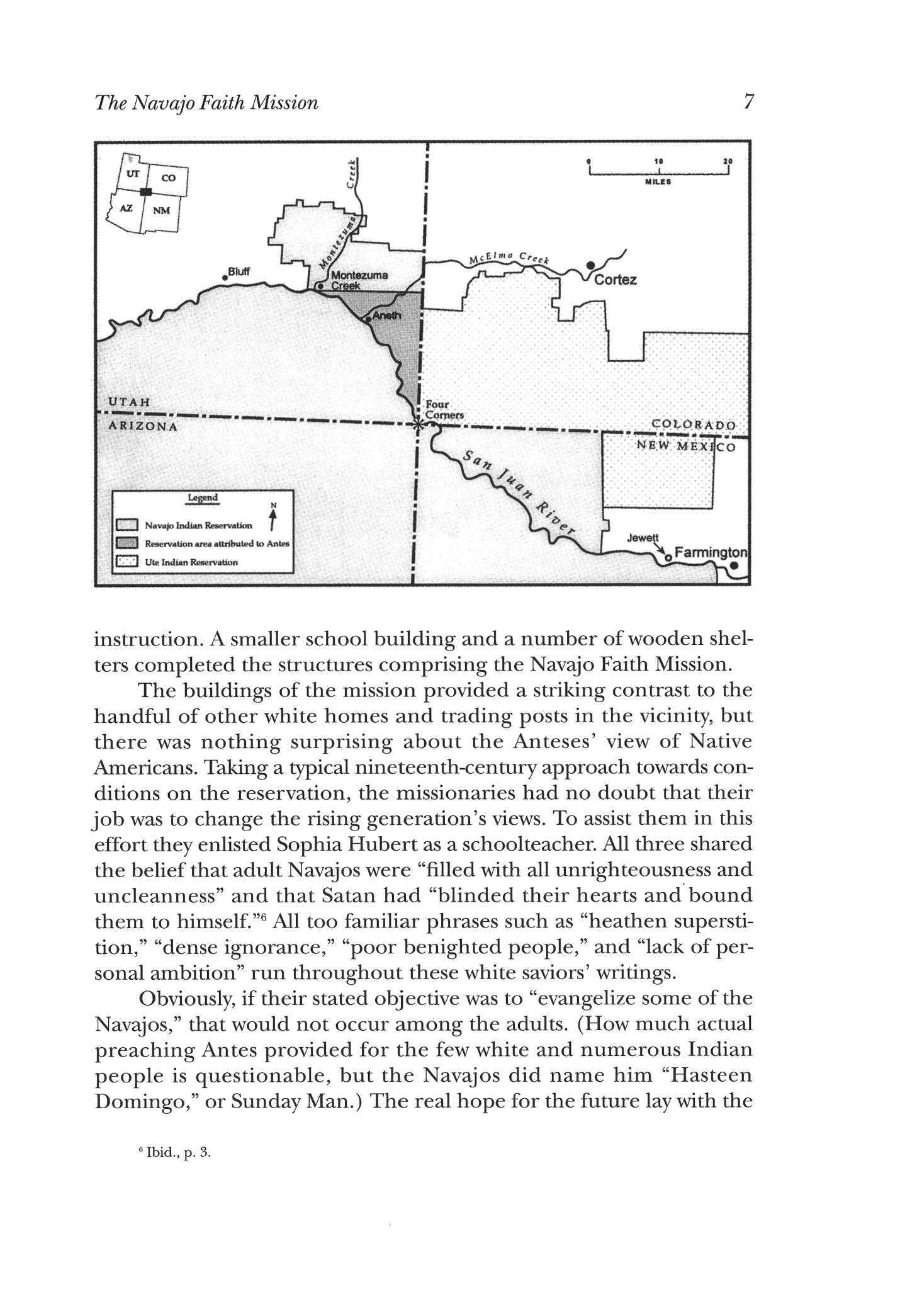

instruction. A smaller school building and a number of wooden shelters completed the structures comprising the Navajo Faith Mission.

The buildings of the mission provided a striking contrast to the handful of other white homes and trading posts in the vicinity, but there was nothing surprising about the Anteses' view of Native Americans. Taking a typical nineteenth-century approach towards conditions on the reservation, the missionaries had no doubt that their job was to change the rising generation's views To assist them in this effort they enlisted Sophia Hubert as a schoolteacher. All three shared the belief that adult Navajos were "filled with all unrighteousness and uncleanness" and that Satan had "blinded their hearts and bound them to himself."6 All too familiar phrases such as "heathen superstition," "dense ignorance," "poor benighted people," and "lack of personal ambition" run throughout these white saviors' writings.

Obviously, if their stated objective was to "evangelize some of the Navajos," that would not occur among the adults. (How much actual preaching Antes provided for the few white and numerous Indian people is questionable, but the Navajos did name him "Hasteen Domingo," or Sunday Man.) The real hope for the future laywith the

Ibid., p 3

1

ti ;•:' 1

I"*,- -,"| Vte

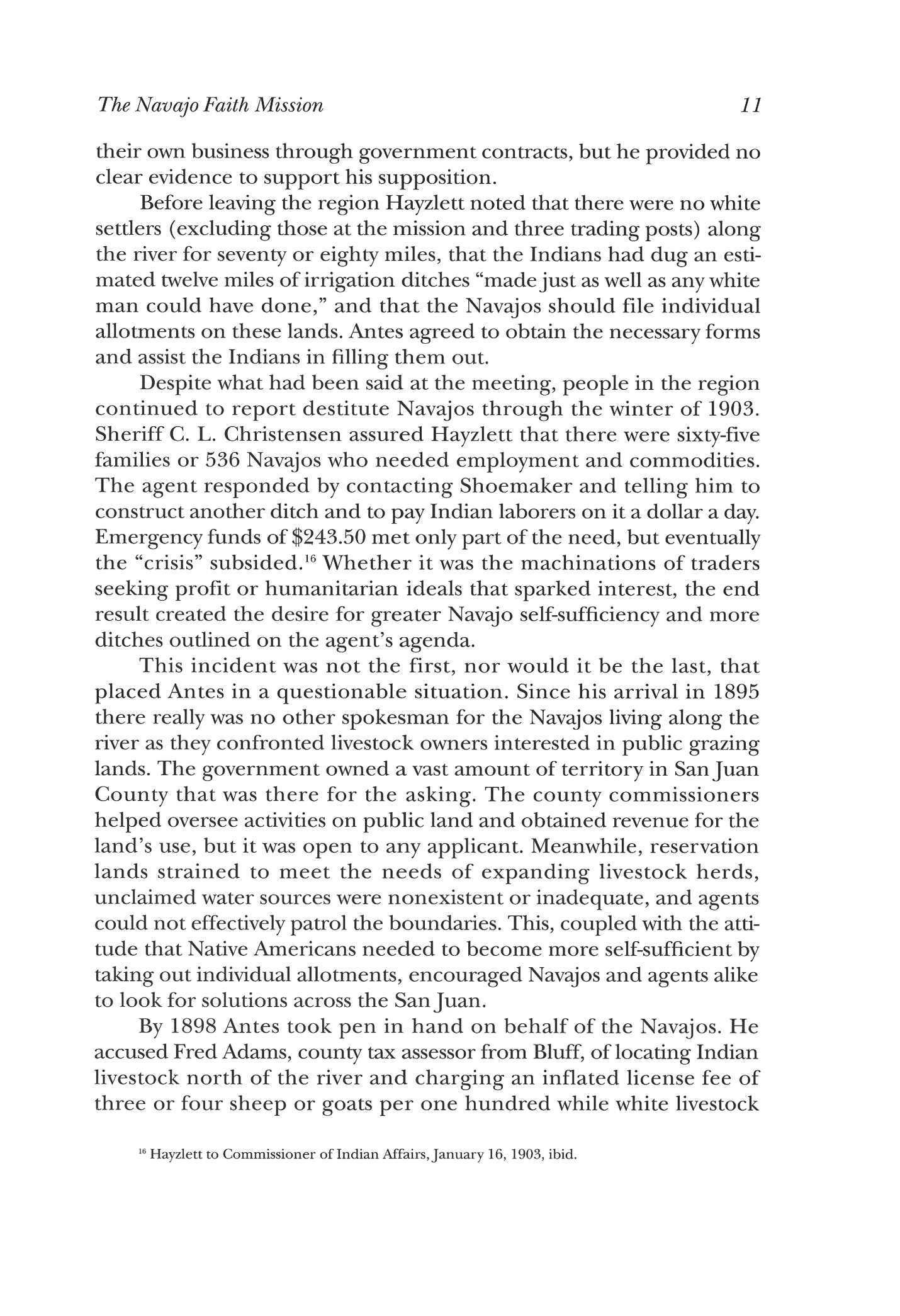

fj Navajo Indian Reservation j

Reservation area attainted to Antes

Indian Reservation

children The mission would serve as a "rescue home or nursery" for young Navajos where they could learn the rudiments of reading, writing, and speaking English with the Bible as a text. When the children reached adolescence they would be removed to another settlement away from the reservation where their transformation into "industrious, intelligent Christians and citizens" would be completed. In 1901 the Lord had not yet identified that spot, but by 1904the Gold Medal Orchard and Farm situated in upper McElmo Canyon just outside of Cortez, Colorado, became the sought-after location. This last point—removing the Indians from the reservation—is important in understanding future conflicts. To Antes's wayof thinking, Indian reservations were a product of a federal policy that intentionally kept the Navajos in a "cesspool of ignorance and superstition and immorality."7 The Navajos were "penned up with the tribal herd on a desert where not even white men could herd sheep profitably." Raising children and women for barter, laziness, and relaxed enforcement of federal rules concerning education were only a few of the problems fostered by a government inattentive to the civilizing process. Hope of temporal and religious salvation remained with the children.

Although Antes may have felt a strong aversion to what he saw happening to Navajo adults, he nevertheless assumed a helpful, neighborly approach with those around him. For example, Old Mexican, a Navajo living in the Montezuma Creek-Aneth area, recalled how "Andy" gave him boards and instructed him on building a headgate to control irrigation water. Old Mexican often went to the mission and received counsel. One time Antes chided him for chasing after women, even though he already had two wives and a number of offspring The Navajo complained that he would happily "take care of my children, buy them clothes, and give them something to eat every once in a while. . . . But I don't care to go back and live with those women. I am scared of my oldest wife. She might do something to me if I were to go back to them." 8 The missionary encouraged him to return to his fatherly duties, and shortly thereafter he once again started providing for his children.

Yet Old Mexican and his problems were only a peripheral concern compared to the mission school that opened in 1899. The facility persisted for eight years with its highest enrollment reaching fifteen

7 Ibid., p. 4.

8 Utah Historical Quarterly

8 Walter Dyk, A Navaho Autobiography (New York: Viking Fund, 1947), pp. 84, 95-96.

The Navajo Faith Mission

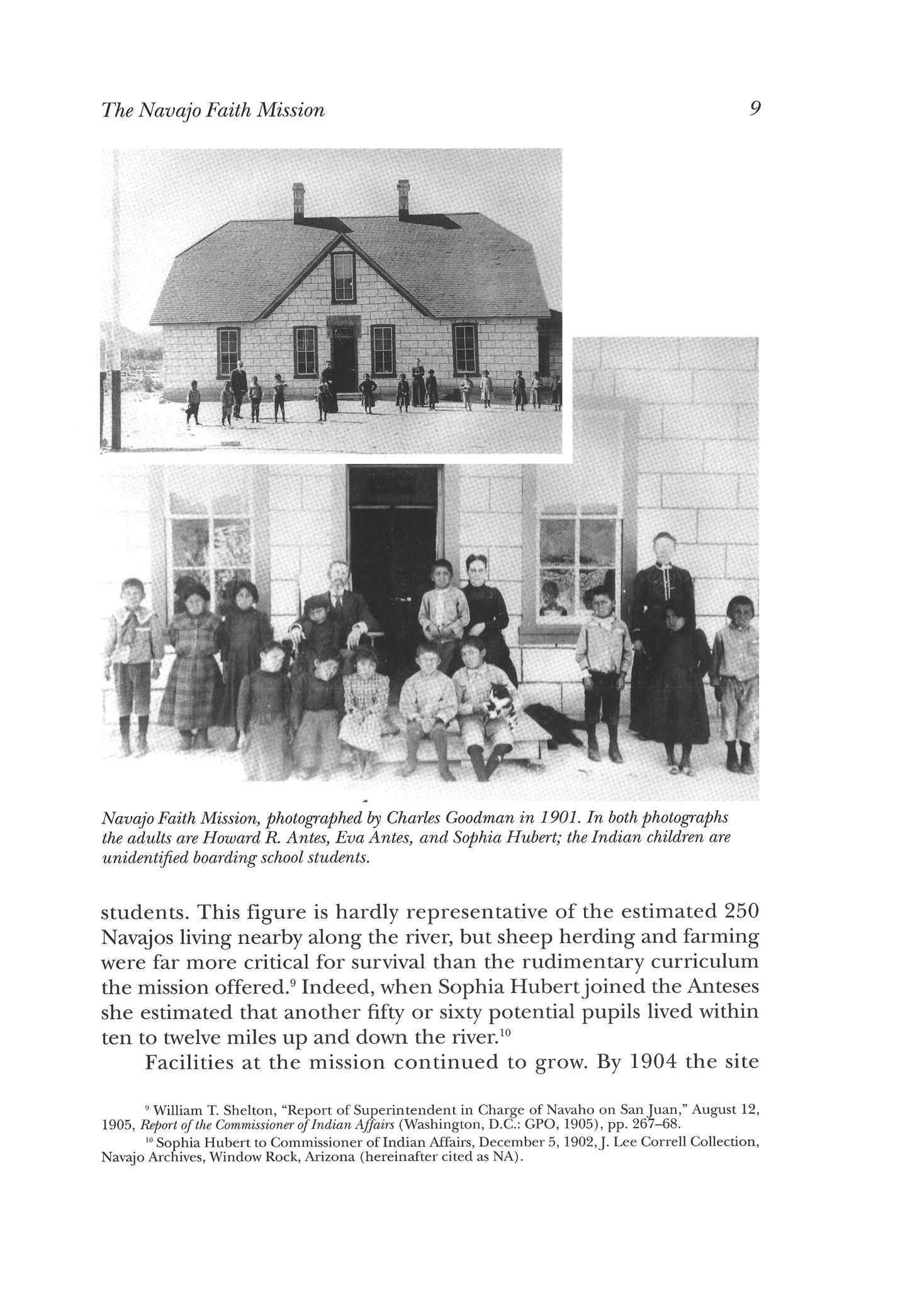

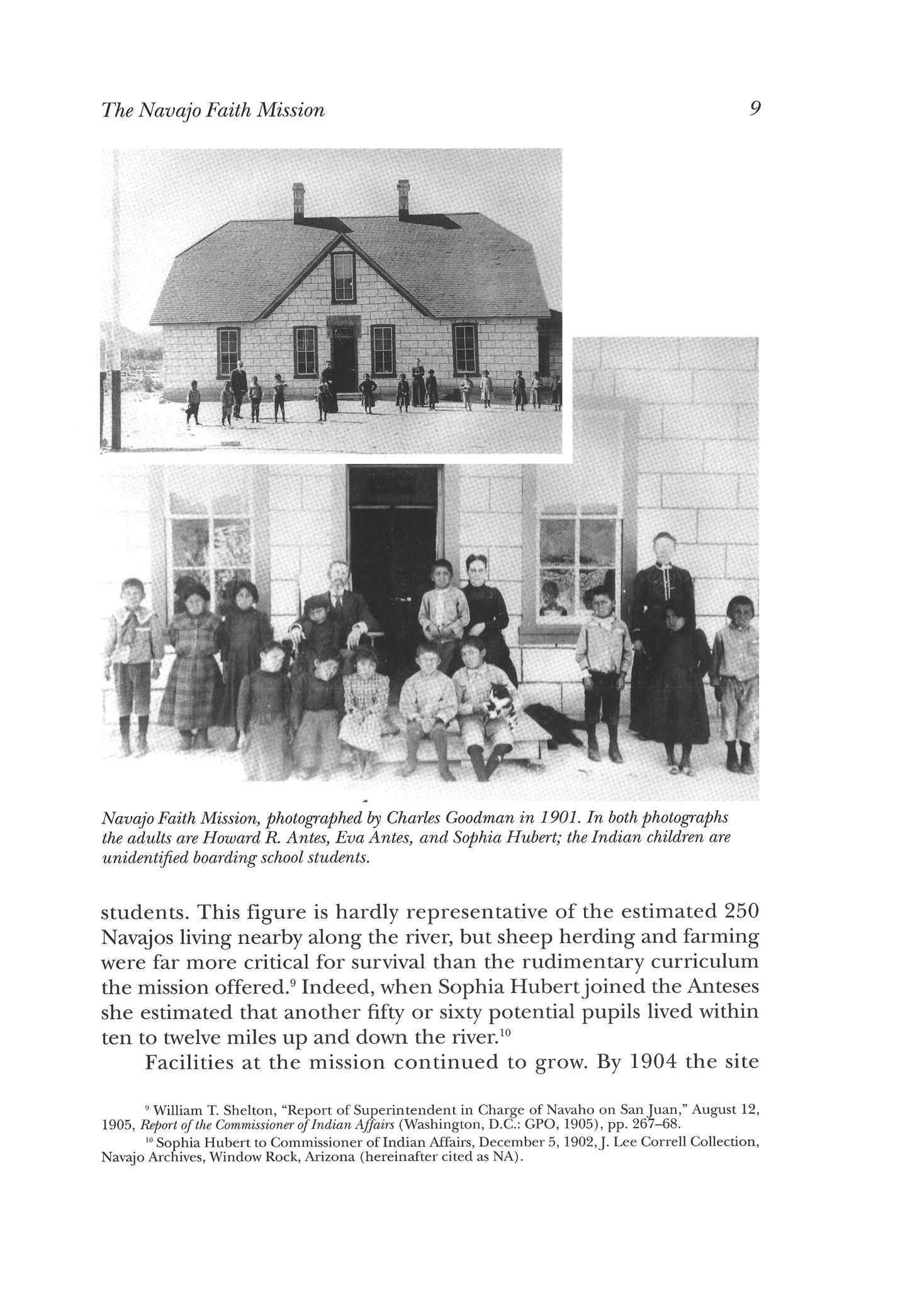

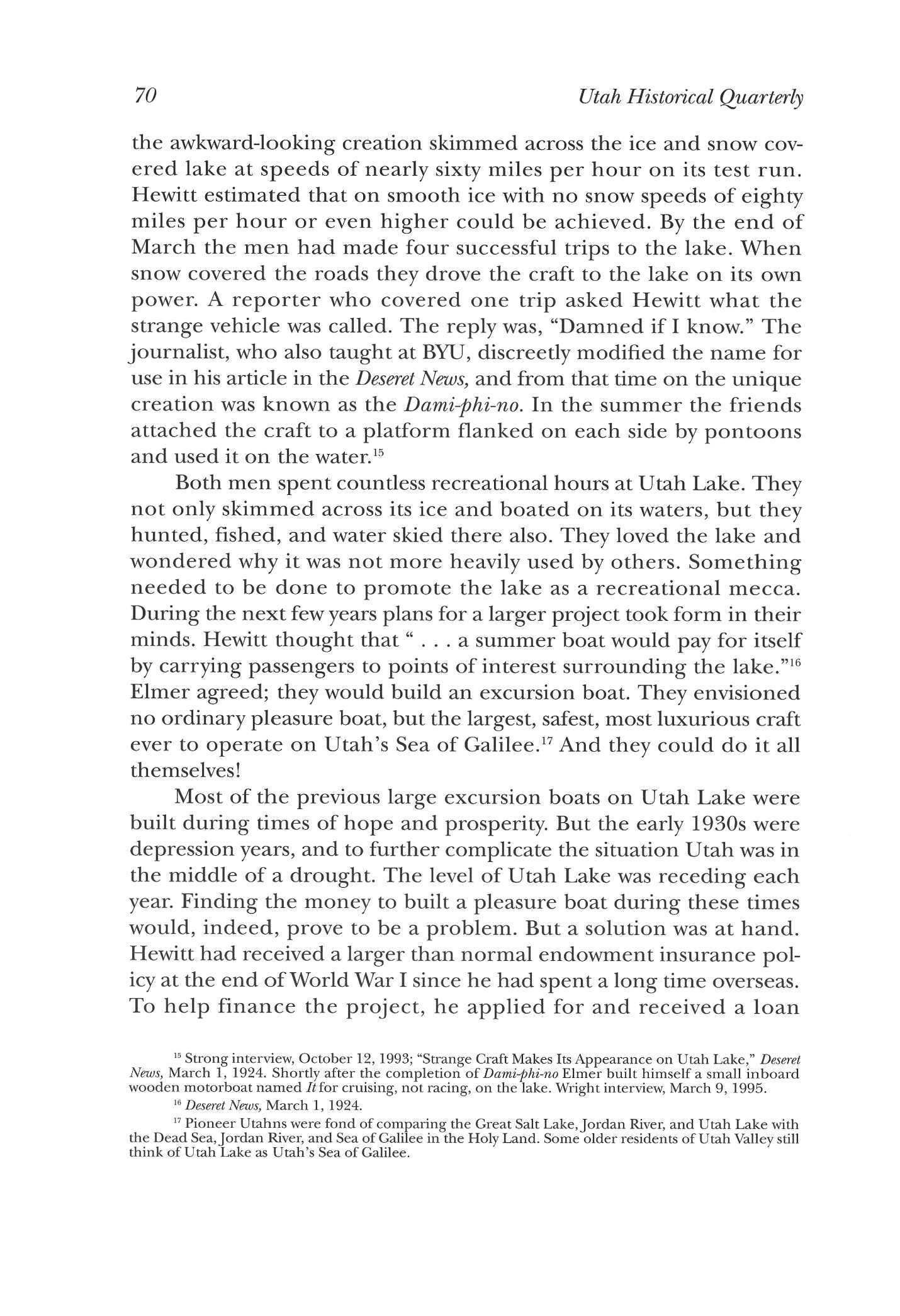

students. This figure is hardly representative of the estimated 250 Navajos living nearby along the river, but sheep herding and farming were far more critical for survival than the rudimentary curriculum the mission offered.9 Indeed, when Sophia Hubertjoined the Anteses she estimated that another fifty or sixty potential pupils lived within ten to twelve miles up and down the river.10

Facilities at the mission continued to grow. By 1904 the site

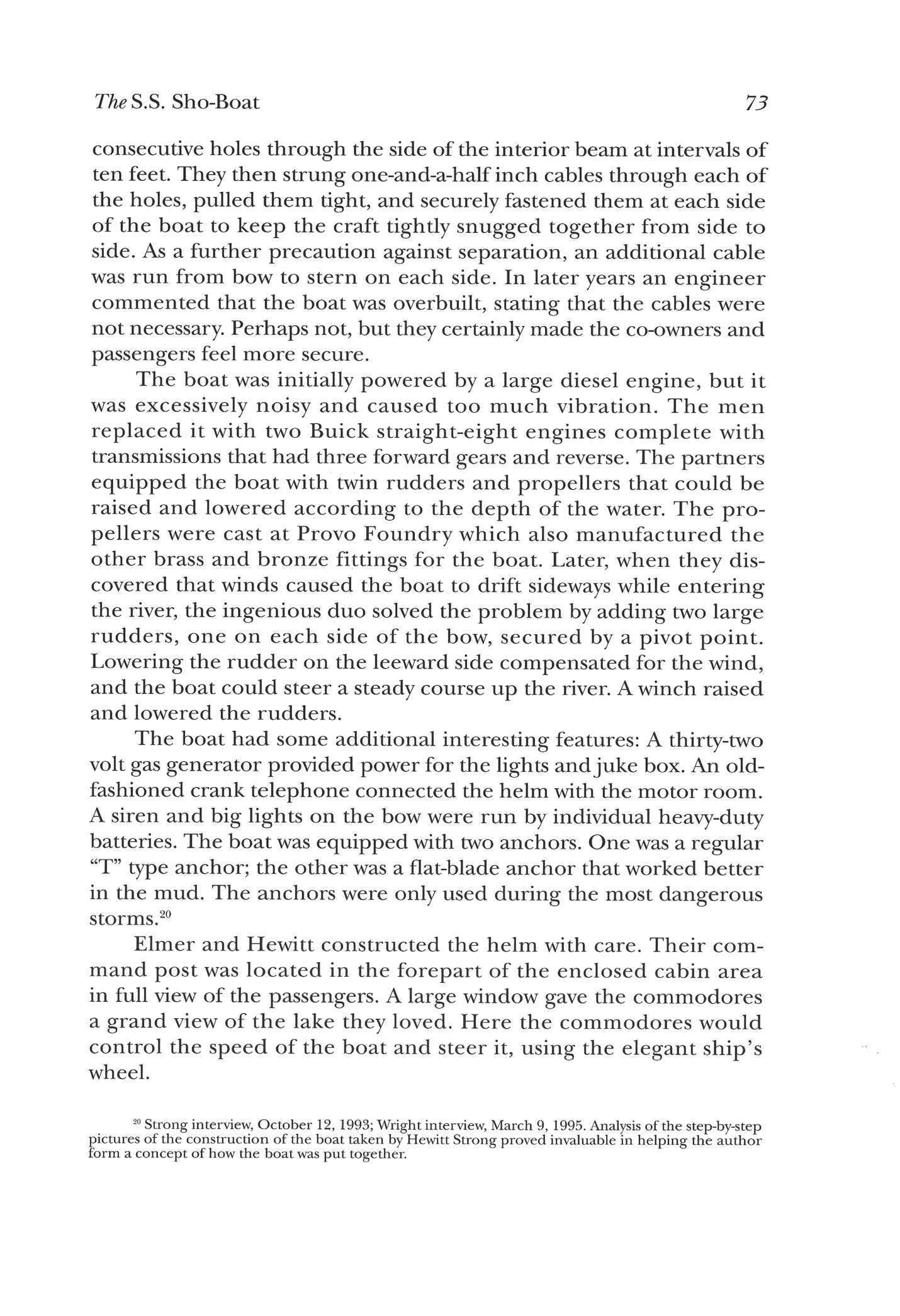

9 William T Shelton, "Report of Superintendent in Charge of Navaho on San Juan," August 12, 1905, Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1905), pp 267-68

10 Sophia Hubert to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, December 5, 1902, J Lee Correll Collection, Navajo Archives, Window Rock, Arizona (hereinafter cited as NA)

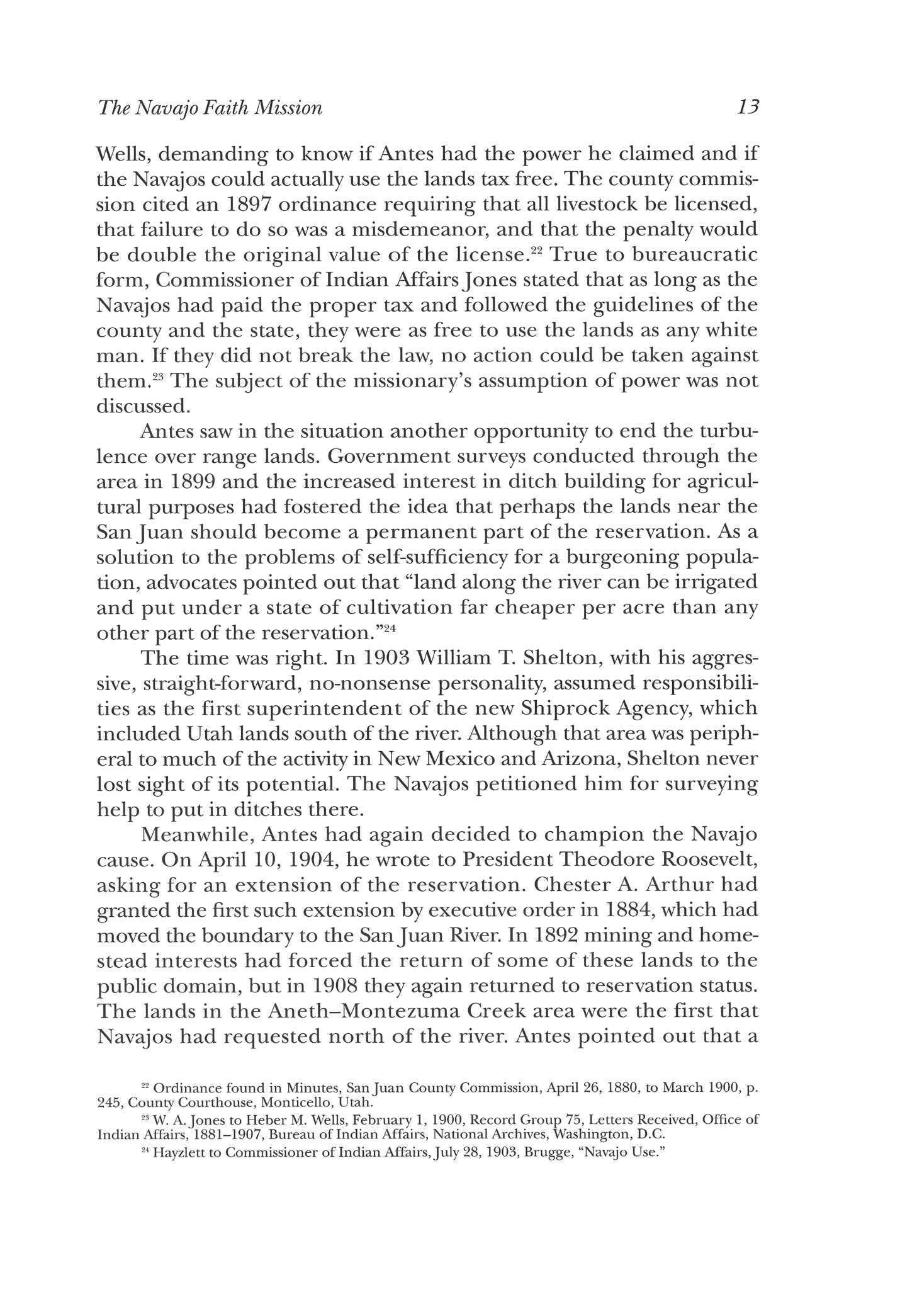

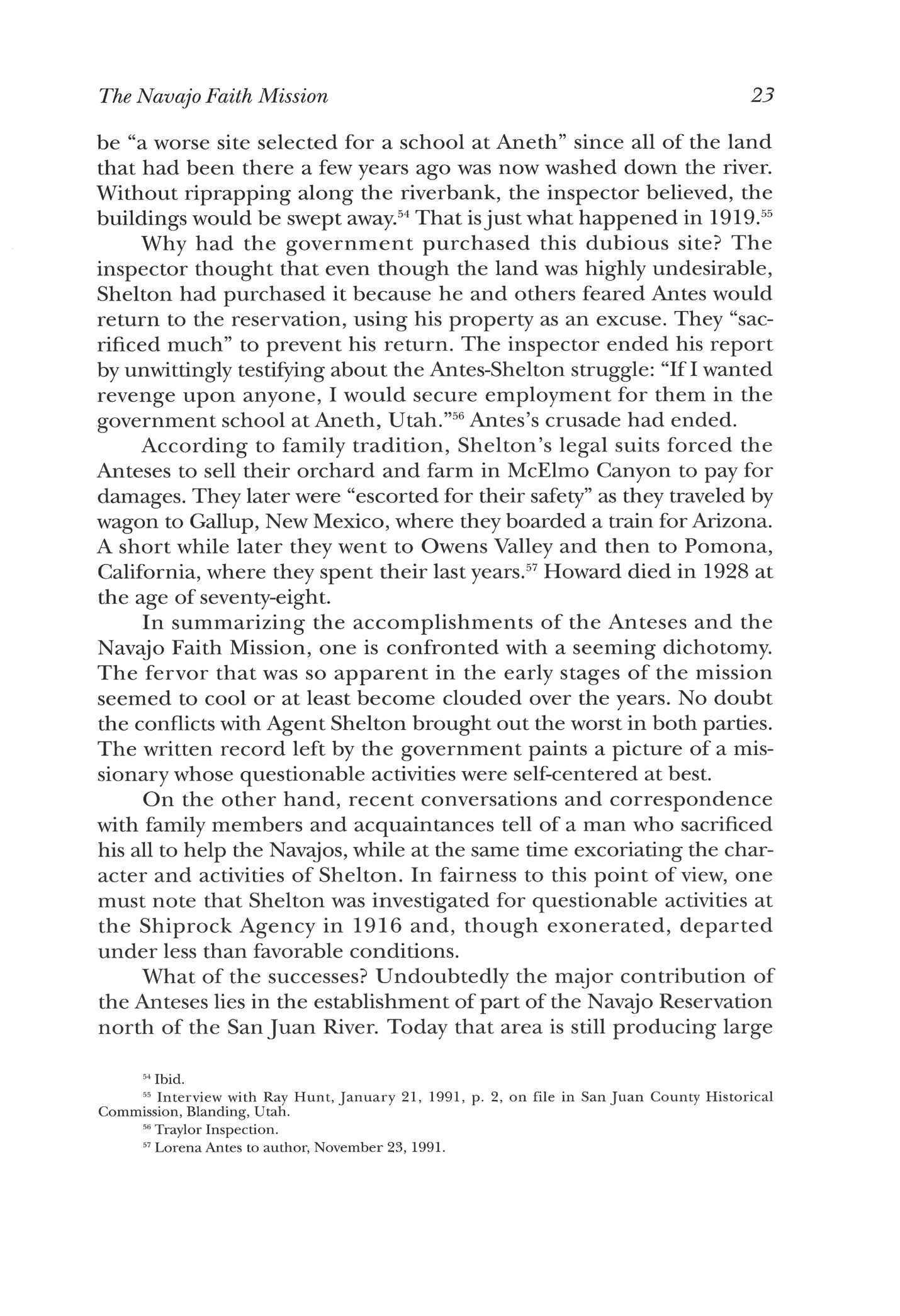

Navajo Faith Mission, photographed by Charles Goodman in 1901. In both photographs the adults are Howard R. Antes, Eva Antes, and Sophia Hubert; the Indian children are unidentified boarding school students.

boasted the Ledyard Home, a smaller school building, and surrounding farm lands and orchards located on the river's flood plain. Antes never took up homestead rights on this property.11 Instead, he put all of his energy into dispensing charitable donations from the East to the Navajos who, according to Antes, were still destitute. He and Eva encouraged the blanket-weaving industry by loaning the wool and dyes necessary for production and "furnishing people with ton after ton of clothing and flour" to sustain them through the winter.12 Antes also stored sacks of corn at the mission for the Navajos who "could not keep it at home without being obliged to give it away."13 Making coffins and burying the dead were other community services provided by the mission

Little wonder when the citizens of Bluff in 1902 petitioned the government to help the starving Navajos that Antes, along with LDS Bishop Jens Nielson of Bluff and Samuel Shoemaker, a government farmer stationed in Farmington, New Mexico, were the men recommended for this humanitarian effort.14 Agent George W. Hayzlett soon received instructions from the secretary of the interior to investigate the situation and to help the 6,000 impoverished Indians in San Juan County—a population statistic far out of line with other sources—by spending $3,000 to purchase emergency rations Hayzlett met Shoemaker in Farmington and then went to the mission to begin his investigation.

He was surprised to hear from the sixty men and two women summoned to discuss the problem that the Navajos were doing well economically—better than they had for several years. Antes added that he had not learned of the petition until two days earlier when the sheriff told him of the plan to have Antes and Bishop Nielson dispense the charity. Charles Goodman, a photographer and the only non-Mormon in Bluff, a town twenty-five miles west of Aneth, corroborated the fact that there were no starving Navajos, as did "every trader between Bluff City and Jewett, New Mexico."15 Antes suggested that perhaps some traders in Bluff had created the misunderstanding in order to increase

11 Antes to President Theodore Roosevelt, April 18, 1904, NA

12 Antes to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, February 2, 1899, cited in David Brugge's "Navajo Use and Occupation of Lands North of the San Juan River in Present-day Utah," photocopy on file at the Edge of the Cedars Museum, Blanding, Utah

13 Antes, The Navajos Evangel, p 4

14 Lemuel H Redd, et al., to Secretary of the Interior, September 5, 1902, NA

15 George W Hayzlett to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, September 18, 1902, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

10 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Navajo Faith Mission

their own business through government contracts, but he provided no clear evidence to support his supposition.

Before leaving the region Hayzlett noted that there were no white settlers (excluding those at the mission and three trading posts) along the river for seventy or eighty miles, that the Indians had dug an estimated twelve miles of irrigation ditches "madejust as well as any white man could have done," and that the Navajos should file individual allotments on these lands Antes agreed to obtain the necessary forms and assist the Indians in filling them out.

Despite what had been said at the meeting, people in the region continued to report destitute Navajos through the winter of 1903. Sheriff C. L. Christensen assured Hayzlett that there were sixty-five families or 536 Navajos who needed employment and commodities The agent responded by contacting Shoemaker and telling him to construct another ditch and to pay Indian laborers on it a dollar a day. Emergency funds of $243.50 met only part of the need, but eventually the "crisis" subsided.16 Whether it was the machinations of traders seeking profit or humanitarian ideals that sparked interest, the end result created the desire for greater Navajo self-sufficiency and more ditches outlined on the agent's agenda.

This incident was not the first, nor would it be the last, that placed Antes in a questionable situation. Since his arrival in 1895 there really was no other spokesman for the Navajos living along the river as they confronted livestock owners interested in public grazing lands. The government owned a vast amount of territory in San Juan County that was there for the asking The county commissioners helped oversee activities on public land and obtained revenue for the land's use, but it was open to any applicant. Meanwhile, reservation lands strained to meet the needs of expanding livestock herds, unclaimed water sources were nonexistent or inadequate, and agents could not effectively patrol the boundaries. This, coupled with the attitude that Native Americans needed to become more self-sufficient by taking out individual allotments, encouraged Navajos and agents alike to look for solutions across the San Juan

By 1898 Antes took pen in hand on behalf of the Navajos. He accused Fred Adams, county tax assessor from Bluff, of locating Indian livestock north of the river and charging an inflated license fee of three or four sheep or goats per one hundred while white livestock

16 Hayzlett to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, January 16, 1903, ibid

11

owners paid only two-and-a-half cents per head. To Antes, this was pure and simple extortion designed to force the Navajos with their large herds back onto the reservation. When told that the "interference of a missionary" was unnecessary, he wrote to Secretary of the Interior C. R. Bliss requesting that he intervene.17

Antes argued that the land was so barren and rocky it was suitable for no other occupation, noting that "fifty miles above us and twentyfive miles below us along the SanJuan River, there are but two [white] men who have a few acres of cultivation" and a couple of trading posts. Because Indian flocks would starve on the sandy, rocky wastes of the reservation, Antes maintained, they should have untaxed access to the resources north of the river Sprinkled throughout this plea were phrases like, "As their friend . . . and as the friend of God, which I know you are also" and, in referring to the Navajo, "destruction of as poor and friendless creatures as our merciful Father in heaven ever called upon us all to show mercy unto, as we hope to receive mercy."18

Antes's letter obtained the desired effect Bliss turned to W A Jones, commissioner of Indian Affairs, who turned to Hayzlett. The response came shortly. The Indians had the right to be there and should not be taxed. As for Mr. Adams, he had overstepped his legal bounds by using "false pretense."Jones sent a letter directly to Antes, stating that the Navajos should pay no taxes as long as they kept the livestock on unoccupied lands and that the missionary should collect evidence to bring Adams to trial.19

Unfortunately, Antes could not do that. In a return dispatch he explained that the prosecuting attorney in Bluff was Fred Adams's brother, that ajury to convict a white man over an Indian could not be found, that Adams's transactions were accomplished without witnesses, that the Indians were not citizens and so could not testify in court, and that the county seat of Monticello was too far away. 20

Antes then assumed the responsibility of writing passes "on the authority of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Secretary of the Interior of the United States" for Navajos wishing to graze livestock on the north side of the river.21 The county commission was irate Kate Perkins, county clerk, fired off letters to Bliss and Governor Heber M.

18 Ibid

12 Utah Historical Quarterly

17 Antes to Secretary of the Interior, November 14, 1898, NA The market value of sheep was $2.50 per head, meaning the Navajos were charged four times as much as the whites.

19 Commissioner of Indian Affairs to Secretary of the Interior, December 2, 1898, NA

20 Antes to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, February 2, 1899, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

21 Kate Perkins to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, January 15, 1900, NA

Wells, demanding to know if Antes had the power he claimed and if the Navajos could actually use the lands tax free. The county commission cited an 1897 ordinance requiring that all livestock be licensed, that failure to do so was a misdemeanor, and that the penalty would be double the original value of the license.22 True to bureaucratic form, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Jones stated that as long as the Navajos had paid the proper tax and followed the guidelines of the county and the state, they were as free to use the lands as any white man. If they did not break the law, no action could be taken against them.23 The subject of the missionary's assumption of power was not discussed

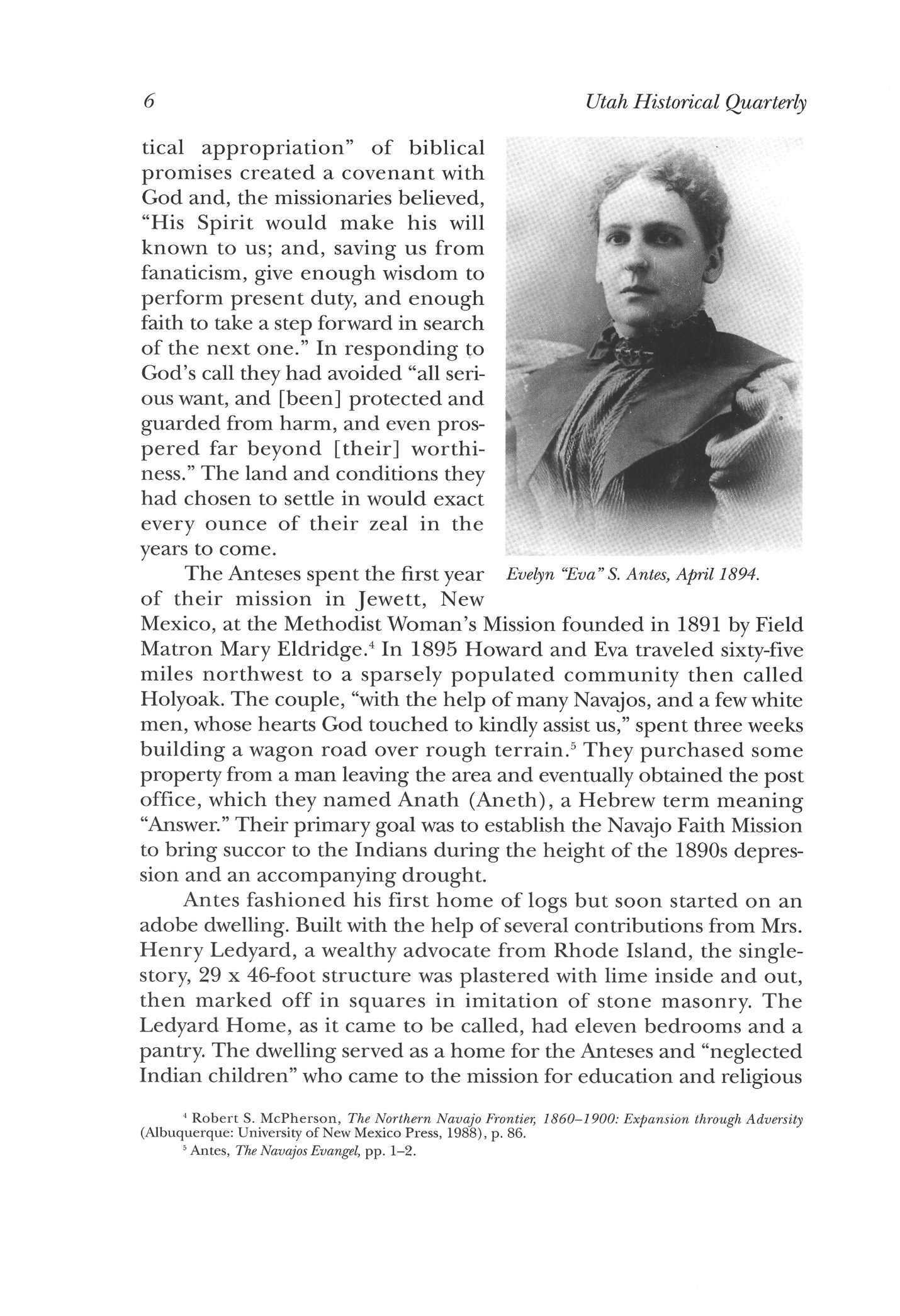

Antes saw in the situation another opportunity to end the turbulence over range lands. Government surveys conducted through the area in 1899 and the increased interest in ditch building for agricultural purposes had fostered the idea that perhaps the lands near the San Juan should become a permanent part of the reservation. As a solution to the problems of self-sufficiency for a burgeoning population, advocates pointed out that "land along the river can be irrigated and put under a state of cultivation far cheaper per acre than any other part of the reservation."24

The time was right. In 1903 William T. Shelton, with his aggressive, straight-forward, no-nonsense personality, assumed responsibilities as the first superintendent of the new Shiprock Agency, which included Utah lands south of the river Although that area was peripheral to much of the activity in New Mexico and Arizona, Shelton never lost sight of its potential. The Navajos petitioned him for surveying help to put in ditches there.

Meanwhile, Antes had again decided to champion the Navajo cause On April 10, 1904, he wrote to President Theodore Roosevelt, asking for an extension of the reservation Chester A Arthur had granted the first such extension by executive order in 1884, which had moved the boundary to the SanJuan River. In 1892 mining and homestead interests had forced the return of some of these lands to the public domain, but in 1908 they again returned to reservation status. The lands in the Aneth-Montezuma Creek area were the first that Navajos had requested north of the river. Antes pointed out that a

The Navajo Faith Mission 13

22 Ordinance found in Minutes, San Juan County Commission, April 26, 1880, to March 1900, p 245, County Courthouse, Monticello, Utah

23 W A Jones to Heber M Wells, February 1, 1900, Record Group 75, Letters Received, Office of Indian Affairs, 1881-1907, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Archives, Washington, D.C

24 Hayzlett to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, July 28, 1903, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

number of white settlers had attempted to farm the region and had given up. There remained only three stores, the Navajo Faith Mission, and the post office operated by Antes He anticipated the end result of an extension of the reservation would be less friction between stockmen and Indians and more desirable conditions for the Navajos.25 Shortly after this communication, Shelton visited the area. Although he described it primarily as a wasteland and believed the morals, customs, and progress of the Navajos in the region "far below the average," he also felt they would work if given the right opportunity. He cited as proof the fact that they had already cut a ditch 200 yards long and twelve feet deep, using only picks, shovels, a level, and plumb-bob for surveying and construction. Unfortunately, all this work could be erased if a major flood scoured the drainage.26

The next question was how to best secure the land Harriet M Peabody, a charity worker among Navajos in the area, thought that individual allotments would be the most practical. She noted how the Indians, most of whom were clustered around the mouth of McElmo Creek, had fenced their lands and built irrigation ditches. They lacked some technical expertise that a farmer could provide, and so she recommended that a trader in Aneth named James M. Holley be given this position.

Shelton agreed in part. He felt Antes's suggestion of annexing the land was good, but he noted that if the Indians had to obtain it through homesteading it would take them twenty-five years to clear its title. On the other hand, if Roosevelt issued an executive order that the land would be protected from encroachment by livestock owners, the Navajos would have access to it and messy legal entanglements would be avoided.27 The three traders living there—Holley, Bryce, and Kermode—could remain unmolested.

Friction continued to fuel the movement to obtain the land Holley reported to Shelton that "Mormons at Bluff were hauling away fences from around Indian gardens and the logs from their homes. He named Frank Hyde,John Adams,Joe Barton, Lemuel Redd, and KumenJones, many of whom were traders. Holley believed these tactics were designed to force the Indians back across the river Holley had probably hoped to tarnish his competitors' reputations, since

14 Utah Historical Quarterly

25 Antes to Theodore Roosevelt, April 18, 1904, NA

26 Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, April 30, 1904, NA

27 Harriet M. Peabody to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, July 8, 1904, and Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, July 30, 1904, NA

The Navajo Faith Mission 15

Shelton investigated the complaints with Navajos and found no basis for the accusations. Holley, in almost the same breath, had also asked Shelton to recommend him for a government position to work with the Indians, which he soon obtained.

28

After some initial revisions due to survey problems, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 324A on May 15, 1905, creating a new section of the reservation. Known today as the Aneth area (not to be confused with another addition created in 1933 known as the Aneth Extension), these lands encompass the region beginning at the mouth of Montezuma Creek, east to the Colorado state line, south along the boundary, then down the San Juan River to Montezuma Creek. Lands previously claimed or settled were excluded from the reservation.29 Antes had fulfilled his goal of annexation.

Whites living near these lands were angry, and some tried to claim mining or homestead rights. The county commissioners and two state senators protested through letters, and others continued to discriminate against Navajos. But Holley received hisjob, and the Indians got their land. While Shelton considered purchasing the Navajo Faith Mission as a nucleus for a tentative boarding school, Antes struggled to keep it open. Two years later he closed and then temporarily reopened the facility, actions taken in part because it was financially impossible to staff it adequately. He retreated to his farm, Gold Medal Orchard, thirty-five miles up McElmo Canyon in Colorado, as he had every summer for the previous five years, and hoped for the best Antes had other concerns as well. He believed that Shelton and Holley were forcing him to abandon his property for a low price. The San Juan River nibbled away at the flood plain upon which the mission sat, washing away with each ripple the value of the property Antes hoped that the agency at Shiprock would provide a riprap barrier to prevent the erosion, but no help was forthcoming. In reality, the agent had at first requested $1,000 to fortify that area with its 500 acres of bottom land, 200 of which were under cultivation by thirty Navajo families.30 But after the river swept away part of the plain and after Antes wrote to President Roosevelt requesting $500 for a breakwater, Shelton

28 James Holley to Shelton, February 20, 1905, and Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, July 25, 1905, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

29 "Navaho Reservation, Utah—Cancellation of Lands Set Apart in Utah," Executive Order 324A, cited in Charles J Kappler, Indian Affairs Laws and Treaties (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913), vol Ill, p 690

30 Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, June 13, 1905, Brugge, "Navajo Use"; Adams, et at, to Interior Department, June 15, 1905, Commissioner of Indian Affairs to Secretary of the Interior, July 27, 1905, and Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, February 13, 1905, NA

changed his mind The agent felt that it would require between $2,000 and $3,000 to restore the river to its original channel and that the missionary should protect his own property. Moreover, although Antes had offered two years earlier to sell the mission for $1,500 as a possible boarding school, it was now too late, since "the best of it has been destroyed."31

Yet darker storm clouds loomed on the horizon in 1907 For some time a Navajo leader named By-a-lil-le had opposed Shelton's plans for improvements in the Aneth area Using witchcraft, thinly

31 U.S., Congress, Senate, "Testimony Regarding Trouble on Navajo Reservation," S Doc 757, 60th Cong., 2d sess., March 3, 1909, pp 53-54 (hereinafter cited as "Testimony"); Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, January 10, 1907, Brugge, "Navajo Use"; Antes to Roosevelt, January 28, 1907, and Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, February 13, 1905, NA

16 Utah Historical Quarterly '- ' • , '« « -

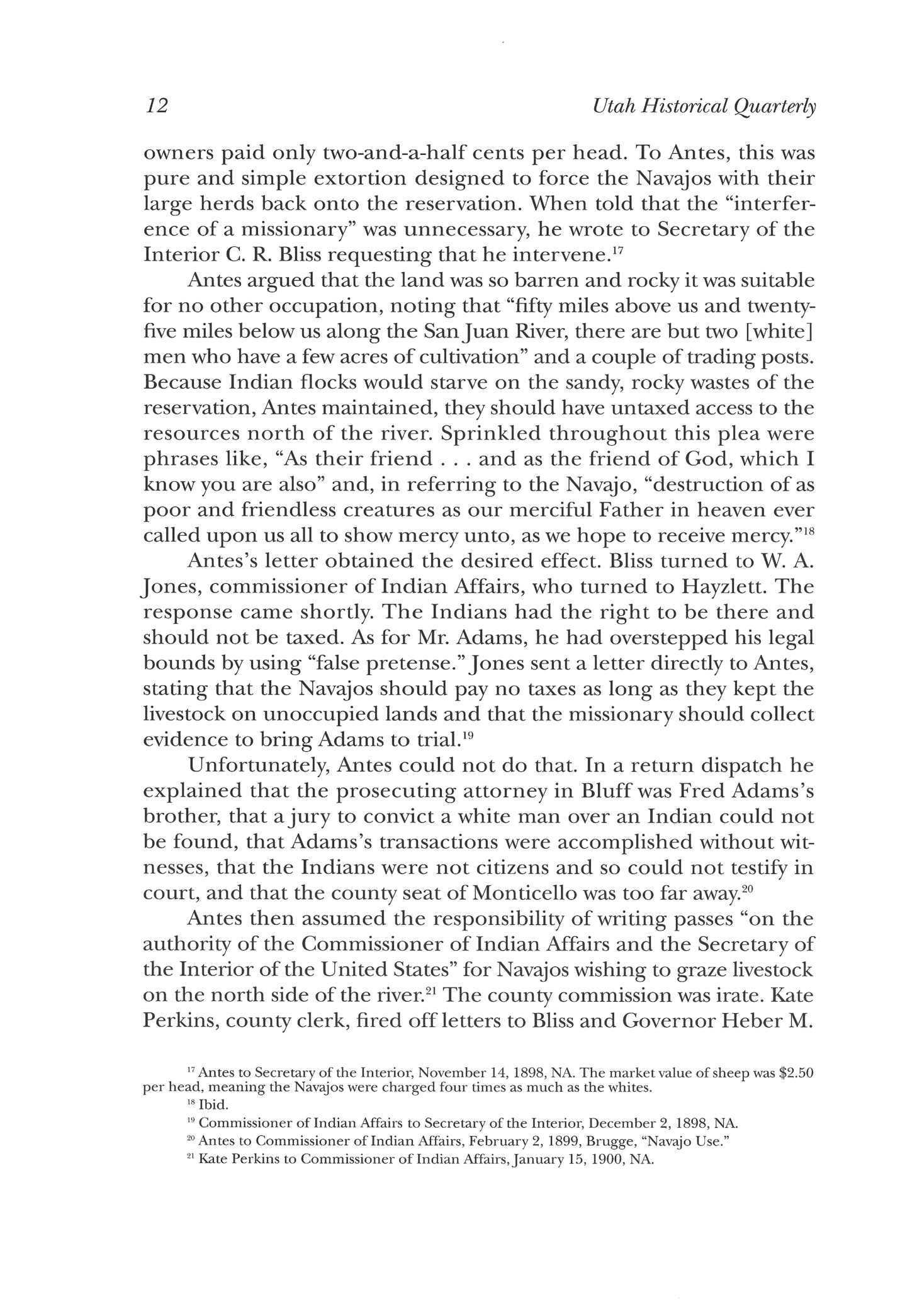

Two views of the Anteses' Gold Medal Orchard in McElmo Canyon taken by Charles Goodman in 1909.

/ %.

'**$*$

Smj^'-iSk

veiled threats, and outright force, he coaxed and coerced a faction of Navajos to resist government programs. By-a-lil-le encouraged his followers to avoid sending their children to school, refuse to use the government sheep-dip vats located at the mouth of Montezuma and McElmo creeks, and defy the orders of Navajo policemen. On October 27, 1907, Shelton and his Indian police led Captain H. O. Williard and two troops of the Fifth Cavalry on a surprise attack of the Navajos' camp. The Indians started shooting, and the soldiers returned fire, killing two and wounding another. They captured By-alil-le along with eight men deemed equally quarrelsome. The troublemakers were marched to Shiprock, Fort Wingate, and then Fort Huachuca, Arizona, where they spent two years at hard labor.32

Although the incident ended quickly and by most accounts was well handled, Antes seized the opportunity to wage another crusade— this time against Shelton Why their relationship had deteriorated is not entirely clear. Perhaps it stemmed from the disagreement over building the riprap dam to protect the mission property, or Shelton's loss of interest in purchasing the site, or a growing misunderstanding over an adopted Navajo boy (to be discussed later), or inaccurate information Antes received from biased sources Whatever the reason, the missionary resorted to the same techniques that had worked so well before. He fired off letters to Colorado Senator H. M. Teller and to the editor of the Denver Post. In them he accused the troops of opening fire on "the poor, defenseless, people," abusing the prisoners, shooting Indians in the back, destroying crops, stealing corn, and scaring the Navajos into the hills. Then the troops withdrew, leaving "the settlers to the mercy of bloodthirsty Indians coming from Cortez."33

Within six months of the incident, Colonel Hugh L. Scott, superintendent of the U.S Military Academy and investigator for the government, received word to proceed to Utah and determine the truthfulness of the charges. He arrived in Aneth on April 19, 1908, and sent for Antes, who was staying on his farm in McElmo Canyon On April 21 the investigation began with Captain Williard, Agent Shelton, Navajo interpreter Bob Martin, Colonel Scott, and Reverend Antes present in the schoolhouse.

The burden of proof rested with the minister, who first called

32 Earl D. Thomas, "Report, Department of Colorado," War Department Annual Reports, 1908, vol. 3 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1908), pp 151-52

33 "Testimony," p 29

17

The Navajo Faith Mission

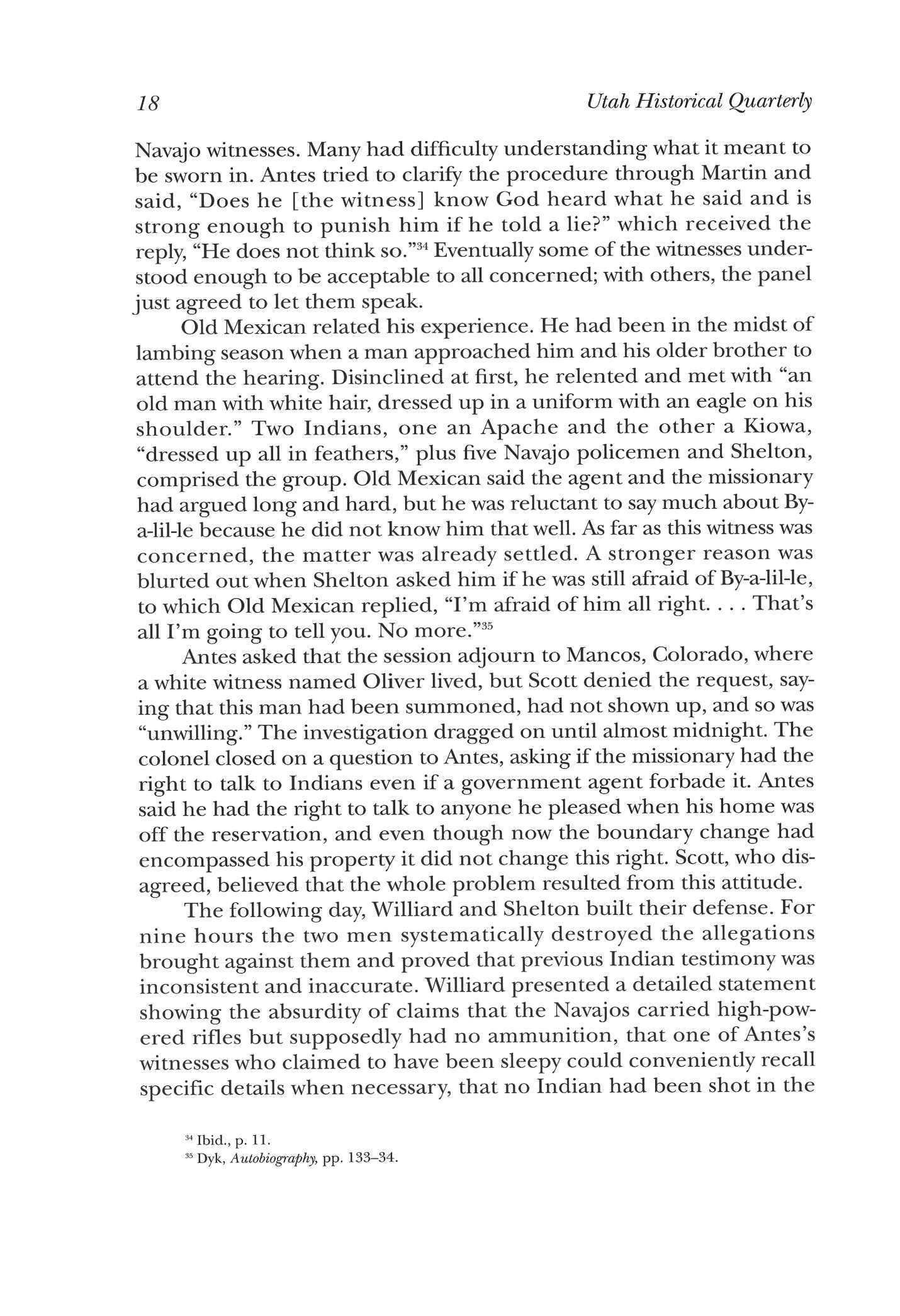

Navajo witnesses Many had difficulty understanding what it meant to be sworn in Antes tried to clarify the procedure through Martin and said, "Does he [the witness] know God heard what he said and is strong enough to punish him if he told a lie?" which received the reply, "He does not think so."34 Eventually some of the witnesses understood enough to be acceptable to all concerned; with others, the panel just agreed to let them speak.

Old Mexican related his experience. He had been in the midst of lambing season when a man approached him and his older brother to attend the hearing. Disinclined at first, he relented and met with "an old man with white hair, dressed up in a uniform with an eagle on his shoulder." Two Indians, one an Apache and the other a Kiowa, "dressed up all in feathers," plus five Navajo policemen and Shelton, comprised the group. Old Mexican said the agent and the missionary had argued long and hard, but he was reluctant to say much about Bya-lil-le because he did not know him that well. As far as this witness was concerned, the matter was already settled. A stronger reason was blurted out when Shelton asked him if he was still afraid of By-a-lil-le, to which Old Mexican replied, "I'm afraid of him all right That's all I'm going to tell you No more."35

Antes asked that the session adjourn to Mancos, Colorado, where a white witness named Oliver lived, but Scott denied the request, saying that this man had been summoned, had not shown up, and so was "unwilling." The investigation dragged on until almost midnight. The colonel closed on a question to Antes, asking if the missionary had the right to talk to Indians even if a government agent forbade it. Antes said he had the right to talk to anyone he pleased when his home was off the reservation, and even though now the boundary change had encompassed his property it did not change this right Scott, who disagreed, believed that the whole problem resulted from this attitude

The following day, Williard and Shelton built their defense. For nine hours the two men systematically destroyed the allegations brought against them and proved that previous Indian testimony was inconsistent and inaccurate. Williard presented a detailed statement showing the absurdity of claims that the Navajos carried high-powered rifles but supposedly had no ammunition, that one of Antes's witnesses who claimed to have been sleepy could conveniently recall specific details when necessary, that no Indian had been shot in the

"Ibid., p 11

35 Dyk, Autobiography, pp 133-34

18 Utah Historical Quarterly

back, that the soldiers had taken steps to bury the dead, that nothing was stolen, and that crops purportedly destroyed during the fight had already been harvested Summarizing his feelings, Williard hotly protested that Antes's allegations "were wilfully and deliberately false and malicious . . . , based on hearsay of the flimsiest character, without an iota of truth [and that he] had been made the butt and scapegoat of a personal feeling of animosity between Mr. Shelton and Mr. Holley on the one hand and the reverend Mr. Antes on the other "36

Williard next offered testimony that shed surprising light on attitudes toward the minister. The captain asserted that he had made an inquiry into Antes's character "all the way from Gallup, New Mexico, to Aneth, Utah, and failed to develop one person who spoke well of him." Dr. W. F. Fish, whose statement Antes had cited during his testimony, said that he had been misrepresented. Even after the doctor clarified the misunderstanding of events, the minister had retorted, . . . but I will make them a whole lot of trouble anyhow; I will write every paper and magazine in the country.' He said something about doing all he could to get Shelton and Holley fired."37 Fish also caught Antes lying about a supposed police force coming to arrest the minister.

Antes was defeated. His charges were dismissed for lack of evidence, his witnesses had either not testified or were shown to be unreliable, and his motives had been called into question. Rather than struggle further he tried to back out gracefully, scraping together as much dignity as possible under the circumstances. Using the guise of protecting his witnesses from the ravages of an irate Shelton, Antes chose "to suffer the humiliation of falling down on this prosecution personally rather than let any injury come to them [i.e., witnesses]."38

This was not the first time that Antes had been "humiliated to the level of the Indians" by their agent. Though he had hoped to take this conflict to a higher court, that was now futile Antes gave Scott both an oral and a written statement relinquishing the charges and wrote to Senator Teller and the editor of the Denver Post, stating that he had believed information and made statements that have since been proven "unreliable and untrue." 3 9 The case was closed, and by 1909 Antes had abandoned much of his life on the San Juan

36 Ibid., p 31

37 Ibid., pp 40-41

38 Ibid., pp 24-25

39 Ibid., pp.38-39

19

The Navajo Faith Mission

There was yet one more episode involving the missionary to the Navajos and one more conflict with Shelton. This time it centered around a Navajo boy named Da-he-ya (He-Went-Down?) born into the Salt clan (Ashiih) in 1902. After his mother died his grandmother, Dezbaa' (Going-to-War), who lived in Aneth, assumed responsibility for the child She was impoverished, however, and decided to take the two-year-old Da-he-ya, dressed only in a velveteen shirt with a necklace of cedar berries, to the mission to remain on "loan" for three years. 40

In 1908 Dezbaa' asked to have the child back Da-he-ya, since christened Samuel S Antes by his foster parents, was now known to his blood relatives as "Little Lost Boy." In official correspondence regarding the boy, Shelton had assumed the role of wanting to do what was best for the youth. The agent had written to Antes, saying that he could either continue to keep Samuel for three to five years, applying the same procedure used to enroll a reservation student in a non-reservation school, or the foster parents could legally adopt him Both courses of action were apparently pursued.41

To the grandmother, though, there was another reason for not returning the child to her. On July 4, 1905, Samuel and another boy were playing with matches and burned down the barn at the Gold Medal Farm, creating an estimated loss of $500 The grandmother believed that Antes kept the child as payment for the lost barn. She appealed to the agent for Samuel's return while Shelton inquired as to the authority Antes had to keep the boy "off the reservation and away from his people."42

Soon Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis E. Leupp became involved, asking Shelton for his understanding of the situation. The agent responded that two to three years before, the Navajos complained about how children attending the school had not been properly fed and clothed and how the Anteses had locked them out of the house in bad weather as punishment Shelton stated, "It is generally understood in this country that Mr Antes is not all that his title of Missionary would imply. In a few years he has changed from a poor missionary to a prosperous rancher. . . ,"43 The agent continued to enumerate Antes's shortcomings: People believed the reverend received free supplies donated by easterners and then sold them to

4(1 Shelton to Antes, February 13, 1908, NA; Lorena C Antes to author, September 8, 1991

41 Telephone conversation with Lorena Antes, June 18, 1991; Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 6, 1908, NA

42 Shelton to Antes, February 13, 1908, NA; Montezuma Journal (Cortez) July 7, 1905, p 1

43 Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 6, 1908, NA

20 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Navajo Faith Mission

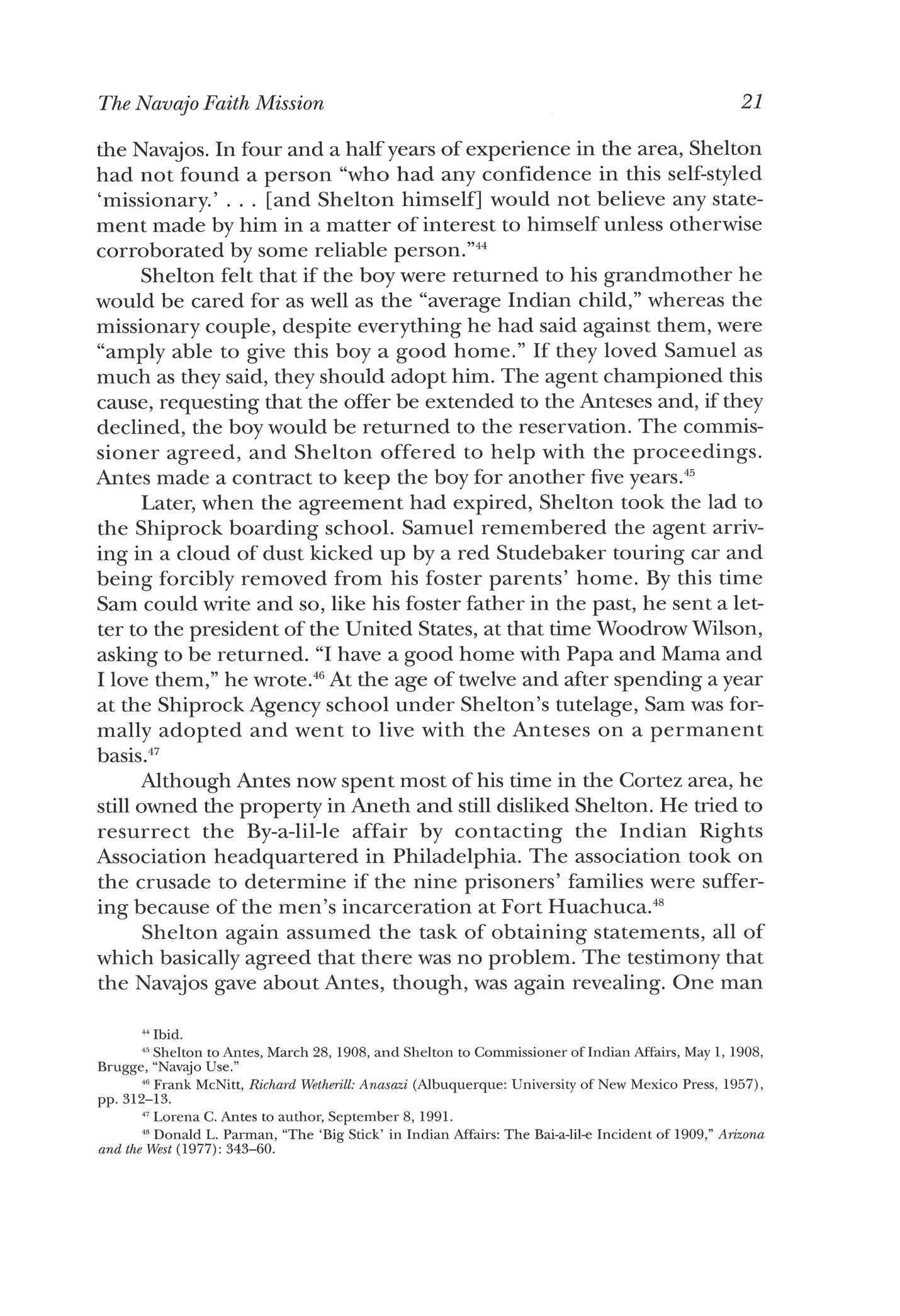

die Navajos In four and a half years of experience in the area, Shelton had not found a person "who had any confidence in this self-styled 'missionary.' . . . [and Shelton himself] would not believe any statement made by him in a matter of interest to himself unless otherwise corroborated by some reliable person."44

Shelton felt that if the boy were returned to his grandmother he would be cared for as well as the "average Indian child," whereas the missionary couple, despite everything he had said against them, were "amply able to give this boy a good home." If they loved Samuel as much as they said, they should adopt him. The agent championed this cause, requesting that the offer be extended to the Anteses and, if they declined, the boy would be returned to the reservation. The commissioner agreed, and Shelton offered to help with the proceedings. Antes made a contract to keep the boy for another five years. 45

Later, when the agreement had expired, Shelton took the lad to the Shiprock boarding school. Samuel remembered the agent arriving in a cloud of dust kicked up by a red Studebaker touring car and being forcibly removed from his foster parents' home By this time Sam could write and so, like his foster father in the past, he sent a letter to the president of the United States, at that time Woodrow Wilson, asking to be returned. "I have a good home with Papa and Mama and I love them," he wrote.46 At the age of twelve and after spending a year at the Shiprock Agency school under Shelton's tutelage, Sam was formally adopted and went to live with the Anteses on a permanent basis.47

Although Antes now spent most of his time in the Cortez area, he still owned the property in Aneth and still disliked Shelton He tried to resurrect the By-a-lil-le affair by contacting the Indian Rights Association headquartered in Philadelphia. The association took on the crusade to determine if the nine prisoners' families were suffering because of the men's incarceration at Fort Huachuca.48

Shelton again assumed the task of obtaining statements, all of which basically agreed that there was no problem. The testimony that the Navajos gave about Antes, though, was again revealing. One man

44 Ibid.

45 Shelton to Antes, March 28, 1908, and Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, May 1, 1908, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

46 Frank McNitt, Richard Wetherill: Anasazi (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1957), pp. 312-13.

47 Lorena C Antes to author, September 8, 1991

48 Donald L. Parman, "The 'Big Stick' in Indian Affairs: The Bai-a-lil-e Incident of 1909," Arizona and the West (1977): 343-60.

21

said, "I have never heard of Mr Antes giving anything to the Indians." Another testified, "My camp was near his house and I was at his place a great deal. ... I never saw or heard of him giving the Indians anything without pay."49 This same man told of how the missionary had jumped on top of his son and then chased him away because the boy had turned water into an irrigation ditch. Antes also had persuaded this father to send one of his sons away to school After the boy left, the father heard that the boy was sick, asked three times unsuccessfully that the missionary write to have the son returned, and later learned that the boy had died.

The final conflict arose two years later when Shelton found out that Antes was running an unlicensed trading post from his private holdings in Aneth. The missionary advertised by sending "goods and trinkets" out with Navajo employees who attracted customers, bought their sheep, and then grazed the animals on reservation lands. One Navajo noted that "Andy" had been chased out before and would often return the same day to pick up where he left off Shelton seized 116 animals, told the Navajos not to trade with Antes, and sought permission to officially deny him access to the reservation.50

Four months later the missionary was still in business, sending "robes, beads, bracelets, rings, and guns" to prospective customers.51 Shelton simmered and waited. Finally, in 1914, the agent had his day in a Salt Lake City court. He requested Old Mexican, through an interpreter, to testify and "tell on the missionary." The proceedings must have vindicated Shelton, since shortly after the trial the government officially told the minister to get off the reservation According to Old Mexican, "They were old folks, Andy and his wife, and they cried when they were leaving. They were driven off in the fall, as things were getting ripe."52

Antes did not leave the Four Corners area before sinking a final barb. Some time before 1916 he sold the Navajo Faith Mission for $1,200 to the government for a boarding school.53 After the renovations were completed an inspector reported that the home had been remodeled for employees' quarters and a new building constructed for dorms and classrooms. He bemoaned the fact that there could not

49 Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, January 16, 1909, NA.

50 Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 2, 1911, Brugge, "Navajo Use"; Dyk, Autobiography, p 143

51 Shelton to Hon Hiram K Booth, January 23, 1912, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

62 Shelton to Booth, January 23, 1912, NA; Dyk, Autobiography, pp 162-65

53 Traylor Inspection, January 22, 1917, Brugge, "Navajo Use."

22 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Navajo Faith Mission

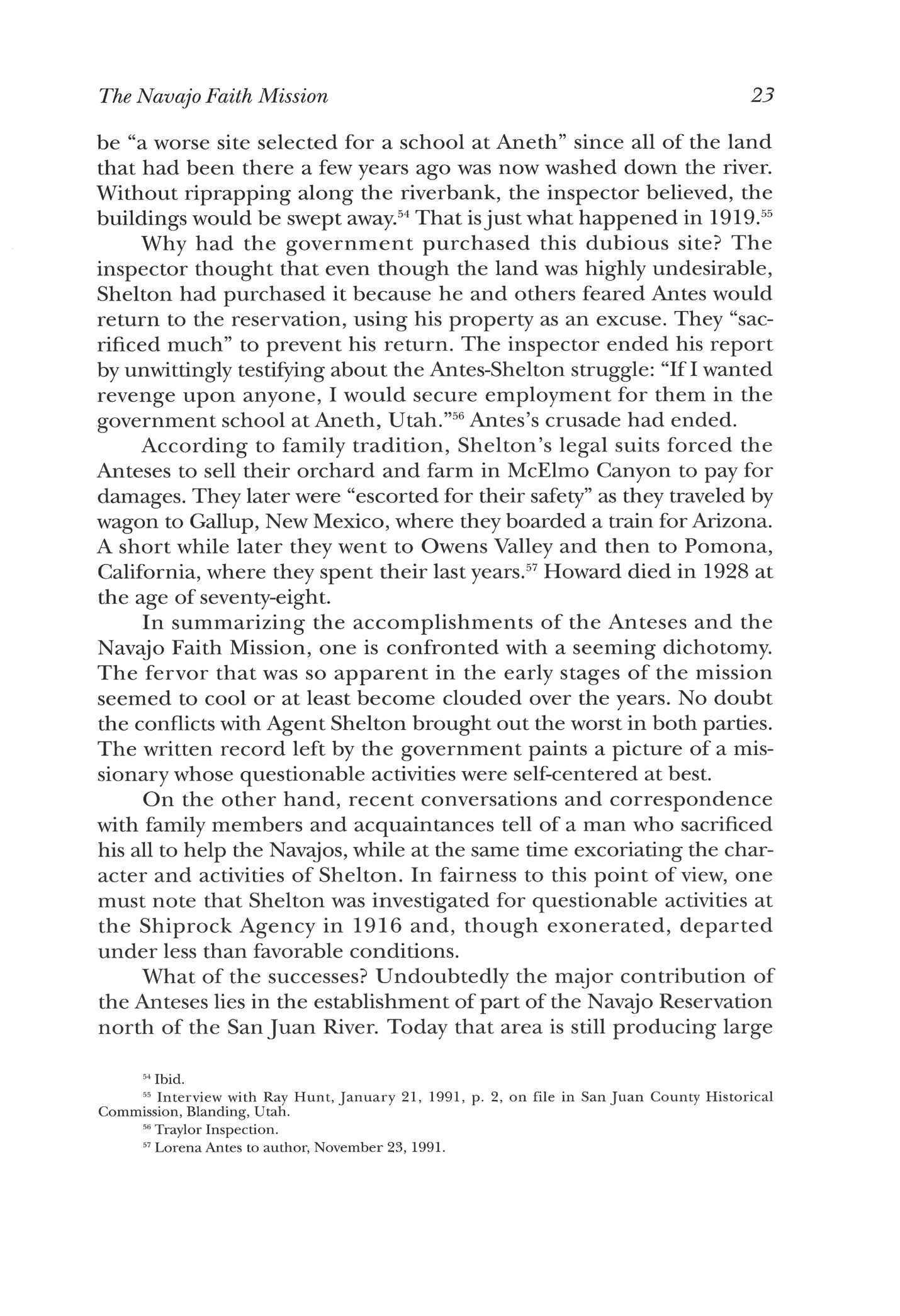

be "a worse site selected for a school at Aneth" since all of the land that had been there a few years ago was now washed down the river Without riprapping along the riverbank, the inspector believed, the buildings would be swept away. 54 That isjust what happened in 1919.55

Why had the government purchased this dubious site? The inspector thought that even though the land was highly undesirable, Shelton had purchased it because he and others feared Antes would return to the reservation, using his property as an excuse They "sacrificed much" to prevent his return. The inspector ended his report by unwittingly testifying about the Antes-Shelton struggle: "If I wanted revenge upon anyone, I would secure employment for them in the government school at Aneth, Utah."56 Antes's crusade had ended.

According to family tradition, Shelton's legal suits forced the Anteses to sell their orchard and farm in McElmo Canyon to pay for damages. They later were "escorted for their safety" as they traveled by wagon to Gallup, New Mexico, where they boarded a train for Arizona. A short while later they went to Owens Valley and then to Pomona, California, where they spent their last years. 57 Howard died in 1928 at the age of seventy-eight.

In summarizing the accomplishments of the Anteses and the Navajo Faith Mission, one is confronted with a seeming dichotomy

The fervor that was so apparent in the early stages of the mission seemed to cool or at least become clouded over the years. No doubt the conflicts with Agent Shelton brought out the worst in both parties. The written record left by the government paints a picture of a missionary whose questionable activities were self-centered at best.

On the other hand, recent conversations and correspondence with family members and acquaintances tell of a man who sacrificed his all to help the Navajos, while at the same time excoriating the character and activities of Shelton. In fairness to this point of view, one must note that Shelton was investigated for questionable activities at the Shiprock Agency in 1916 and, though exonerated, departed under less than favorable conditions

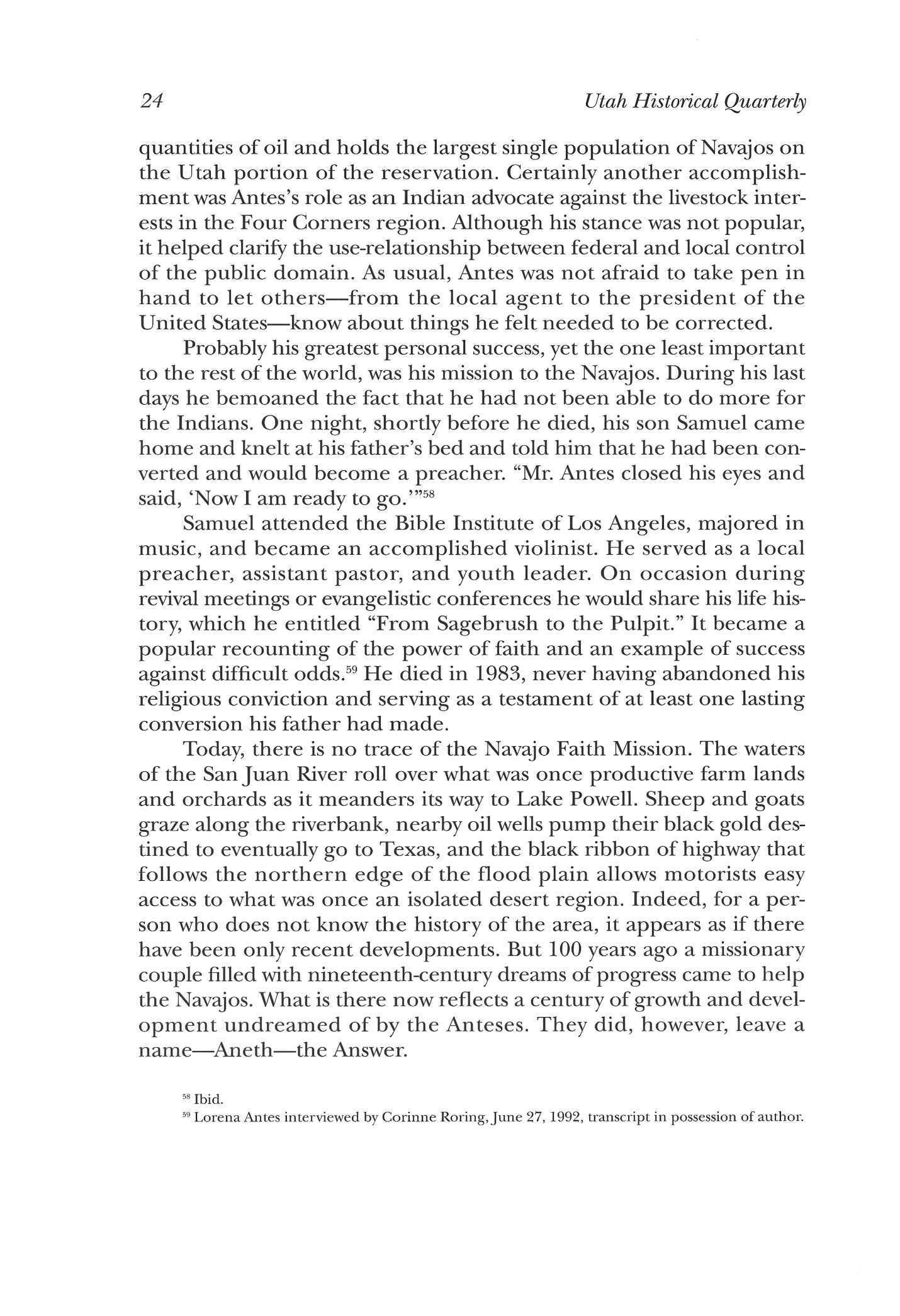

What of the successes? Undoubtedly the major contribution of the Anteses lies in the establishment of part of the Navajo Reservation north of the San Juan River Today that area is still producing large

23

54 Ibid 55 Interview with Ray Hunt, Januar y 21, 1991, p 2, on file in San Jua n County Historical Commission, Blanding, Utah 56 Traylor Inspection 57 Lorena Antes to author, November 23, 1991

quantities of oil and holds the largest single population of Navajos on the LTtah portion of the reservation. Certainly another accomplishment was Antes's role as an Indian advocate against the livestock interests in the Four Corners region. Although his stance was not popular, it helped clarify the use-relationship between federal and local control of the public domain. As usual, Antes was not afraid to take pen in hand to let others—from the local agent to the president of the United States—know about things he felt needed to be corrected.

Probably his greatest personal success, yet the one least important to the rest of the world, was his mission to the Navajos. During his last days he bemoaned the fact that he had not been able to do more for the Indians One night, shortly before he died, his son Samuel came home and knelt at his father's bed and told him that he had been converted and would become a preacher. "Mr. Antes closed his eyes and said, 'Now I am ready to go.'"58

Samuel attended the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, majored in music, and became an accomplished violinist. He served as a local preacher, assistant pastor, and youth leader. On occasion during revival meetings or evangelistic conferences he would share his life history, which he entitled "From Sagebrush to the Pulpit." It became a popular recounting of the power of faith and an example of success against difficult odds.59 He died in 1983, never having abandoned his religious conviction and serving as a testament of at least one lasting conversion his father had made.

Today, there is no trace of the Navajo Faith Mission The waters of the San Juan River roll over what was once productive farm lands and orchards as it meanders its way to Lake Powell. Sheep and goats graze along the riverbank, nearby oil wells pump their black gold destined to eventually go to Texas, and the black ribbon of highway that follows the northern edge of the flood plain allows motorists easy access to what was once an isolated desert region. Indeed, for a person who does not know the history of the area, it appears as if there have been only recent developments But 100 years ago a missionary couple filled with nineteenth-century dreams of progress came to help the Navajos What is there now reflects a century of growth and development undreamed of by the Anteses. They did, however, leave a name—Aneth—the Answer.

24 Utah Historical Quarterly

Ibid

Lorena Antes interviewed by Corinne Roring,June 27, 1992, transcript in possession of author

The Sensational Murder of James R. Hay and Trial of Peter Mortensen

BY CRAIG L. FOSTER

BY CRAIG L. FOSTER

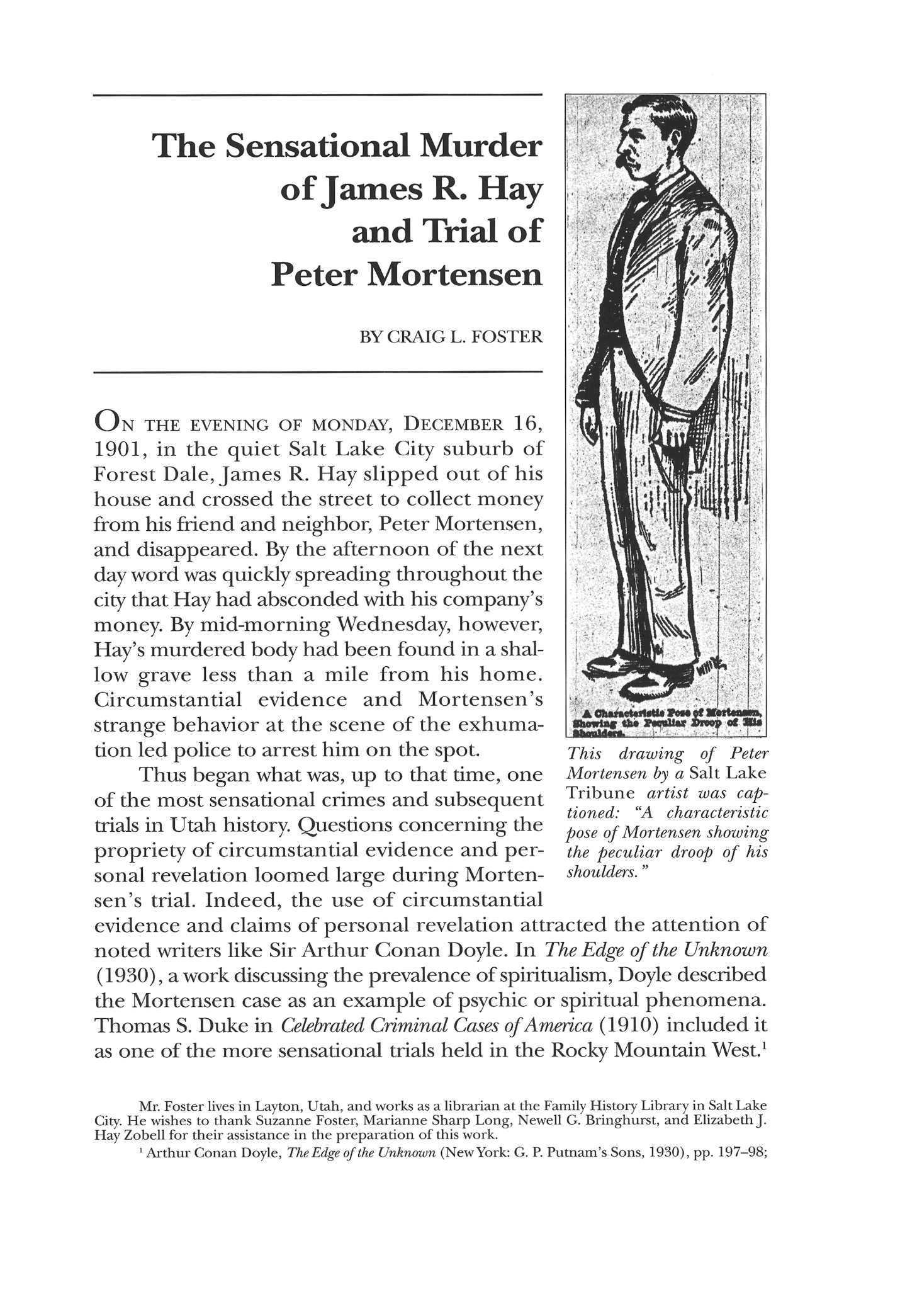

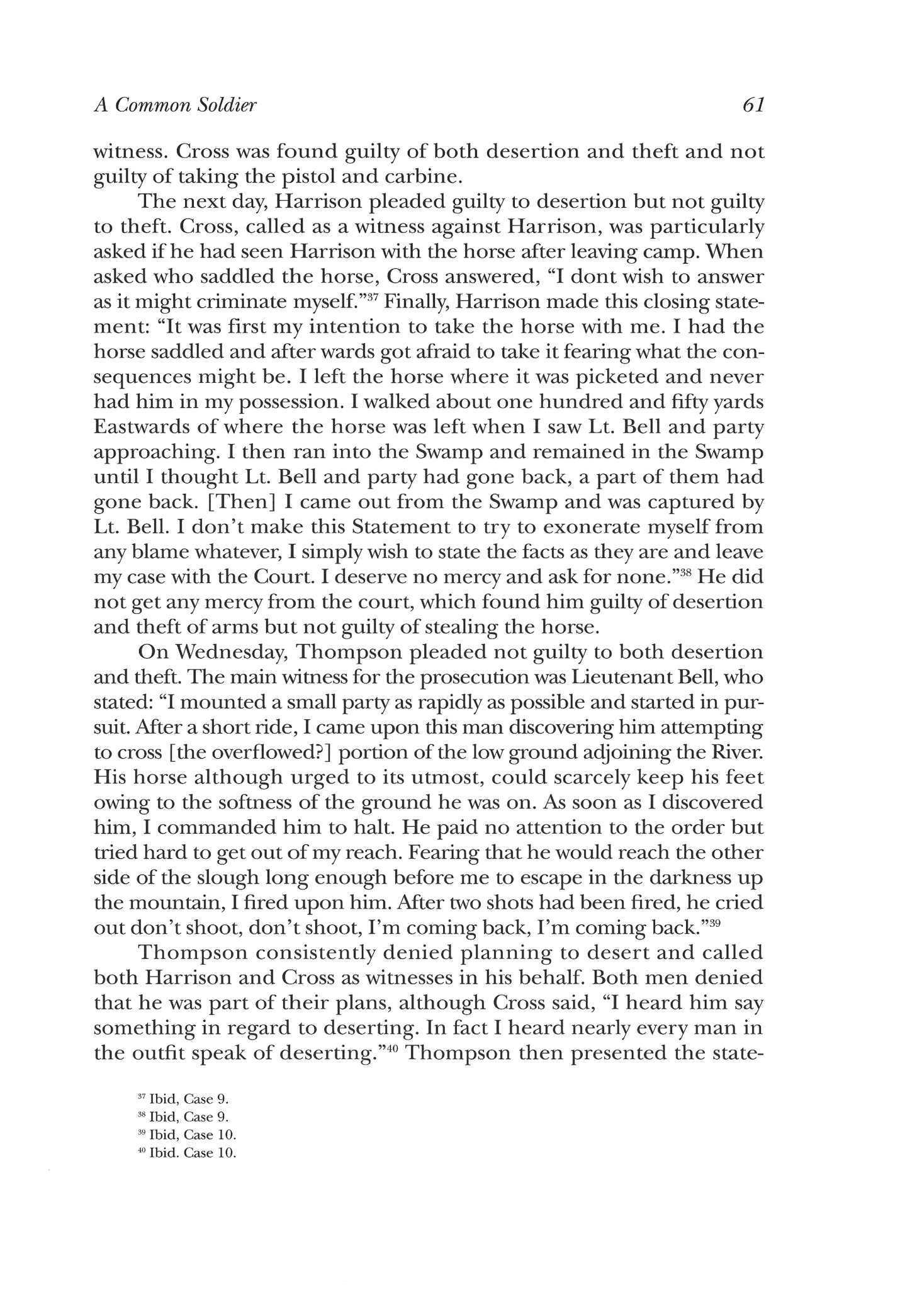

O N THE EVENING OF MONDAY, DECEMBER 16, 1901, in the quiet Salt Lake City suburb of Forest Dale, James R. Hay slipped out of his house and crossed the street to collect money from his friend and neighbor, Peter Mortensen, and disappeared. By the afternoon of the next day word was quickly spreading throughout the city that Hay had absconded with his company's money. By mid-morning Wednesday, however, Hay's murdered body had been found in a shallow grave less than a mile from his home Circumstantial evidence and Mortensen's strange behavior at the scene of the exhumation led police to arrest him on the spot. Thus began what was, up to that time, one of the most sensational crimes and subsequent trials in Utah history. Questions concerning the propriety of circumstantial evidence and personal revelation loomed large during Mortensen's trial Indeed, the use of circumstantial evidence and claims of personal revelation attracted the attention of noted writers like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In The Edge of the Unknown (1930), awork discussing the prevalence of spiritualism, Doyle described the Mortensen case as an example of psychic or spiritual phenomena. Thomas S. Duke in Celebrated Criminal Cases ofAmerica (1910) included it as one of the more sensational trials held in the Rocky Mountain West.1

7* •« . • '"-' afr•'•'•' rw ,: '•••" :>* Kb ' .% 3w'".- i ••'• j&mki IWM^im\ mi •I *I '/I E l * *'Y •JTW/I if : -• 1 (I Ii IE 1 •mil I W$ I 1 • '• AW* ^ 1 it JiW $£ll£pmm^ . V .<;', ' - '.' i ; fi1 i :-:; /.;;

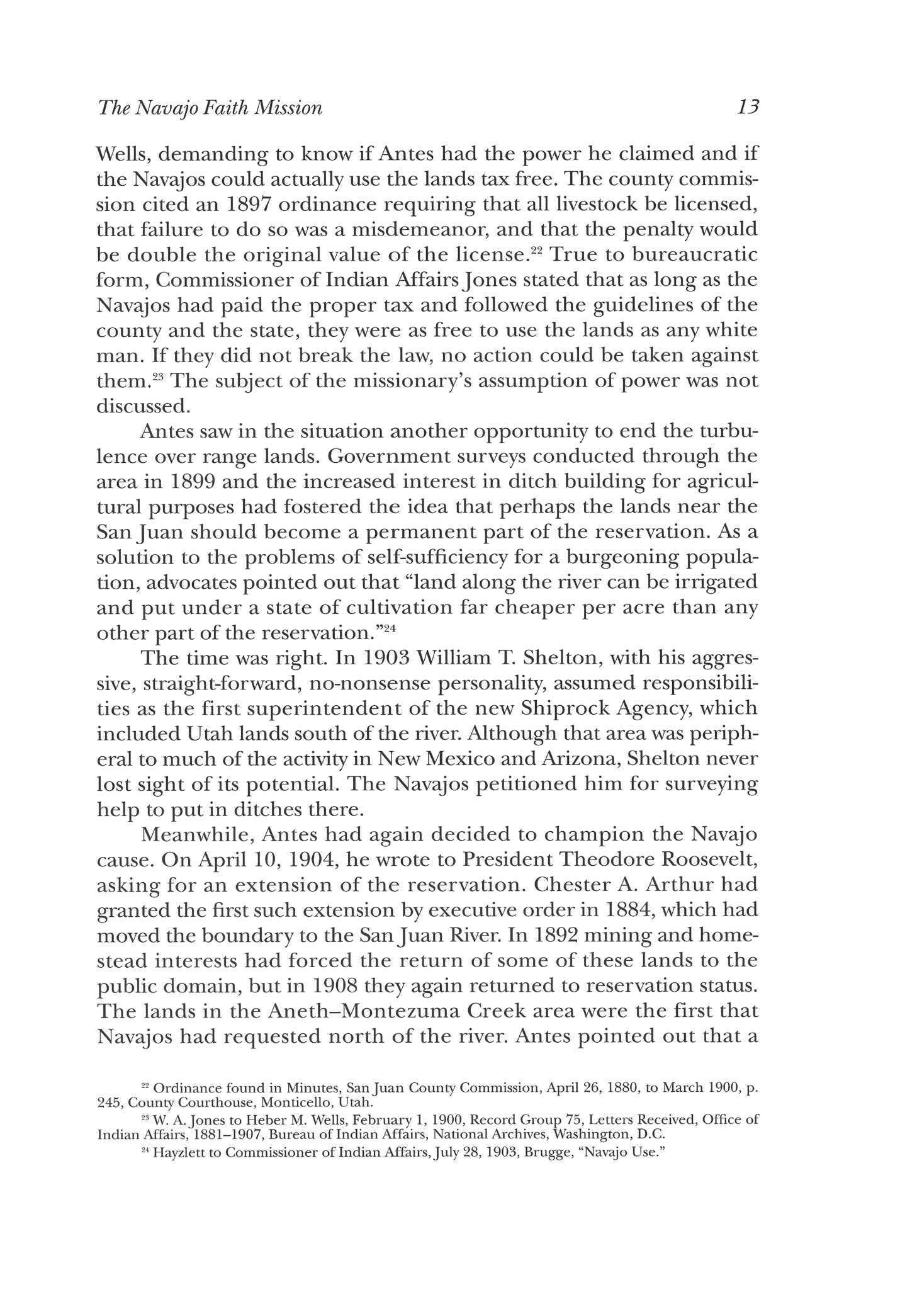

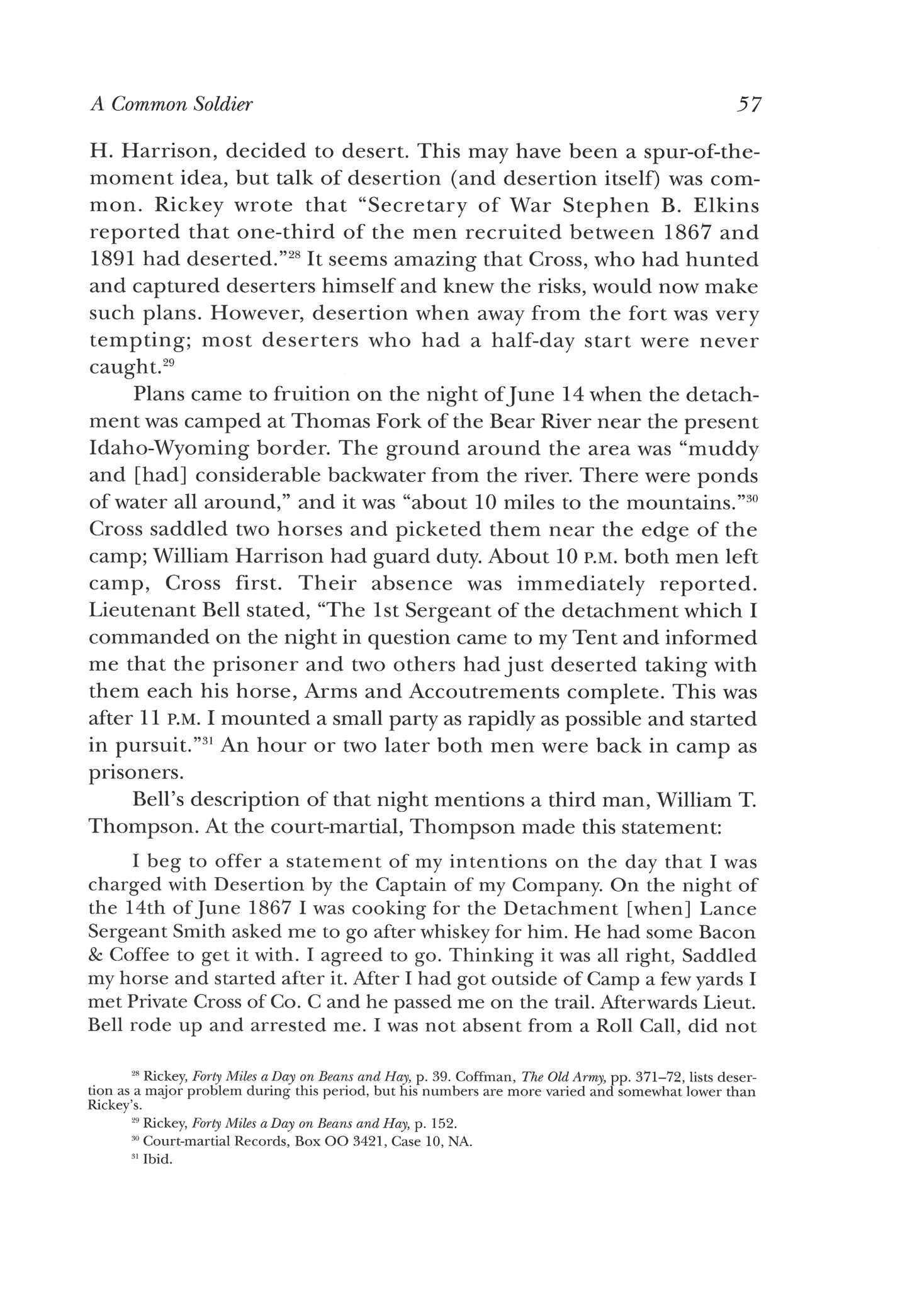

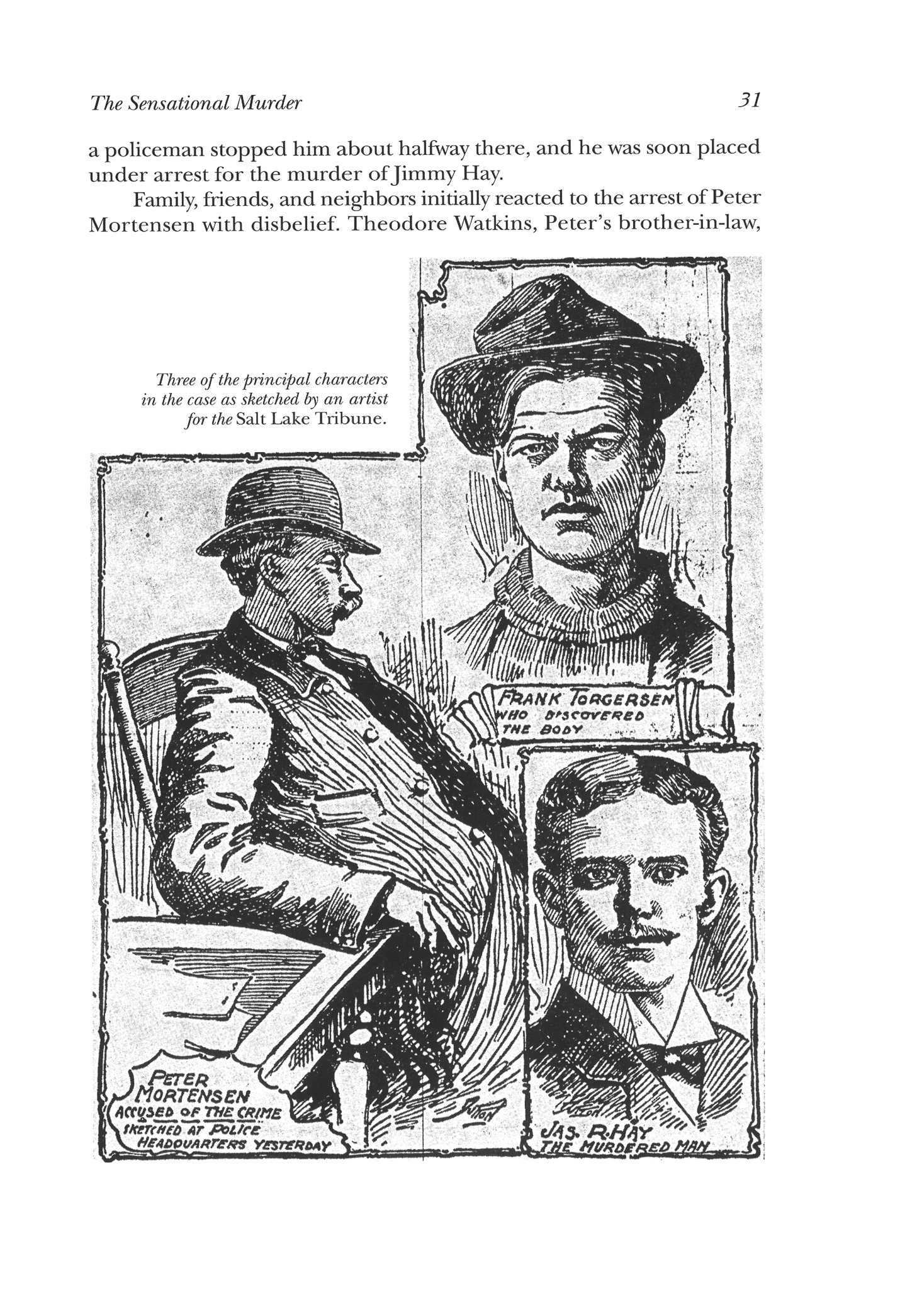

77m drawing of Peter Mortensen by a Salt Lake Tribune artist was captioned: "A characteristic pose of Mortensen showing the peculiar droop of his shoulders."

Mr Foster lives in Layton, Utah, and works as a librarian at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City He wishes to thank Suzanne Foster, Marianne Sharp Long, Newell G Bringhurst, and Elizabeth J Hay Zobell for their assistance in the preparation of this work

1 Arthur Conan Doyle, The Edge of the Unknown (New York: G P Putnam's Sons, 1930), pp 197-98;

On a personal side, the Hay murder was a tragedy that greatly affected a number of lives The murder of ayoung, respectable man by afriend and neighbor shocked the city. More tragically, it shattered the lives of those intimately associated with both Hay and Mortensen.

James Robert Hay was born in 1869 in Maryborough, Victoria, Australia.Jimmy, as he was commonly known, was of Scottish stock, his parents having immigrated to Australia from their native Scotland.2 By the mid-1880s members of the Hay family had settled in Timaru, New Zealand, where they were baptized into the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Following the death of Hay's father the remaining family members immigrated to Salt Lake City, residing in the Twentieth Ward Jimmy Hay obtained work as a clerk in ZCMI and through his ward activities met Aggie Sharp. In 1896 they were married in the Salt Lake Temple.3

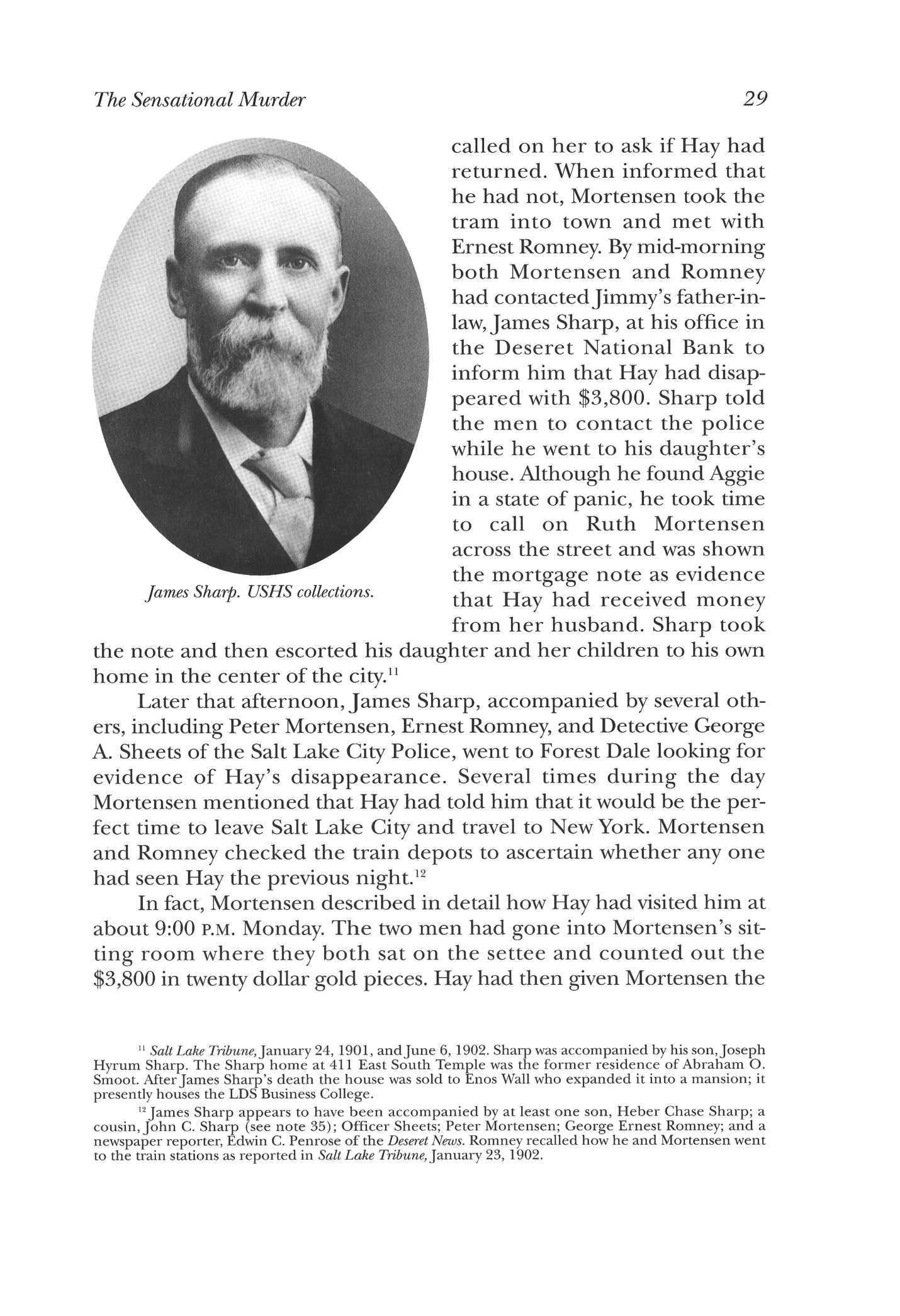

Hay had clearly married above his social class.Aggie Sharp, born in 1876 toJames Sharp and Lizzie Rogers, came from an extremely prominent family both in terms of wealth and social status She was a granddaughter of BishopJohn Sharp of the Twentieth Ward who had been a personal friend and confidant of Brigham Young as well as a canny businessman who had helped found ZCMI, Deseret National Bank, and several railroads. Aggie's father, James Sharp, was equally impressive He had been closely associated with his father in railroading and banking and was, in 1901,president of Deseret National Bank and had an interest in several Utah railroads including the Oregon Short Line He was a former Speaker of the House in Utah's territorial legislature and a former mayor of Salt Lake City. In addition, he was a member of the LDS Board of Education and of the University of Utah's Board of Regents.

Like his father-in-law, Hay was an enterprising, hardworking man seeking financial independence. In 1891 he had left ZCMI and

Thomas S Duke, Celebrated Criminal Cases of America (San Francisco: James H Barry Co., 1910), pp 327-32. Interestingly, the Hay-Mortensen case in Duke's work followed an entry concerning another celebrated Mormon criminal case, the Mountain Meadows Massacre and Philip Klingonsmith's damning testimony against John D Lee L Kay Gillespie also discussed the case in The Unforgiven: Utah's Executed Men (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991)

2 Information obtained from the International Genealogical Index, 1993 edition, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City The parents of James Hay were Robert Massey Hay and Ann McCrea

3 Timaru Branch Records, p 3, LDS Church Archives Robert Massey Hay was not baptized into the church The Ancestral File of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1993 Edition, lists March 15, 1882, as the death date for him. However, the Timaru Heraldlists a Robert Hay as dying in the hospital from consumption on January 31, 1872 This is a very early death date, but it could possibly have been he and would explain why there are no baptismal records for him James Hay and Aggie Sharp were married in the temple byJohn R Winder Witnesses were James Sharp and George Romney Marriage License #6003 for the County of Salt Lake, Utah, September 9, 1896

26 Utah Historical Quarterly

entered into a limited partnership with brothers George Ernest and William S. Romney to form the Pacific Lumber Company. By 1900 the well-known financier David Eccles had joined the firm as a director and president. Hay was a director and secretary of the company. 4 At about that time, Hay, his wife Aggie, and their two young children moved into a home in Forest Dale in what was obviously a significant step in the young couple's upward climb toward social and financial comfort and respectability. 5 There, Hay met Peter Mortensen.

Some three years older than Hay, Mortensen had been born in 1865 in Richfield, Sevier County, Utah, to Danish Mormon settlers who had experienced much hardship in their youth. Their struggle continued into Peter's childhood as his father moved the family to several towns in search of carpentry work Eventually the Mortensens settled in Ogden near a large English family by the name of Watkins.6

In 1891 Peter Mortensen married his twenty-five-year-old neighbor, Ruth Elizabeth Watkins, in the Logan LDS Temple. He followed his father into the carpentry business in Ogden. In 1897 Mortensen moved his young family to Forest Dale and took ajob at the Pacific Lumber Company By 1898 or 1899 he had decided to strike out on his own as an architect/contractor/carpenter. 7 By 1901 he was a recognized builder in the greater Salt Lake City area He was the father of five children and a teacher of theology in the Forest Dale Ward's Sunday School. In that position he came into frequent and friendly

4 According to the Articles of Incorporation for the Pacific Lumber Company, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, the original founders and officers were George Ernest Romney, William S. Romney, James R Hay, and Joseph E.Jensen In 1900 the company was re-incorporated with David Eccles as director and president, Ernest Romney as director and vice-president, James Hay as director and secretary, and Joseph E.Jensen and William S Romnev as directors Eccles held 150 shares of stock valued at $15,000, Ernest Romney 147 shares valued at $14,700, and the other three men one share each valued at $100 Unfortunately, the company suffered from economic problems and in 1911 had its charter of incorporation revoked for failure to pay taxes George Ernest Romney (1868-1940), a close friend of Hay, was the son of Bishop George Romney and Jan e Jamison and lived in the Twentieth Ward Bishop Romney was involved in several business ventures with Eccles, including the Oregon and Mount Hood Lumber companies and Home Fire Insurance of which James Sharp was vice-president.

5 According to AndrewJenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing Co., 1941), pp 253-54, Forest Dale was a small community located on land that was originally part of Brigham Young's Forest Farm and later subdivided into individual home sites that attracted young families In 1896 the Forest Dale Ward was created

6 Monroe Ward Records, p 3, LDS Church Archives; U.S Census of 1880 for the Territory of Utah, Sevier County, Monroe Precinct, p 30; and Ogde n Fourth Ward Records, LDS Church Archives

According to information obtained from the International Genealogical Index, 1993 edition, and the Ancestral File, Charles Frederick Watkins was born and raised in Somersetshire, England He met his London-born wife, Elizabeth Mary Loud, in 1852 They eventually became the parents of eleven children, the last one born in Ogden where they settled after immigrating to America in the late 1870s

7 Logan Temple Record, Book A, p 298, and Forest Dale Ward Record, LDS Church Archives

The Sensational Murder 2 7

contact with his neighbor, Jimmy Hay, who was also actively involved with Forest Dale's Sunday School.8

Although Mortensen was enjoying social stability, he was not having much success financially. Poor business practices had led him to overextend his credit He continued to get building contracts, but when clients were slow to pay for his services he in turn kept his former employer and supplier, Pacific Lumber Company, waiting for payments. In 1900 Mortensen had been forced to take out a second mortgage on his home and to turn over the mortgage note to Ernest Romney of Pacific Lumber. By December 1901 Mortensen owed the lumber company over $3,900. Both Hay and Romney pressured him to pay off his debt. Finally, on December 16, he arrived at the lumber company's office and informed both Hay and Romney that he could pay $3,800 of what he owed. Although he did not have the money with him—it was at his house—he nevertheless asked Hay to fill out a receipt and attach the mortgage note, which Hay did. As the men were preparing to leave the office, Romney specifically told Hay not to collect the money that night as it would be risky to carry so much gold at night. He told him to get it from Mortensen in the morning. Both Hay and Mortensen then took the Calder's Park tram home, arriving a little after 8:00 P.M It is not known what the two men said on the tram, but by the time they arrived in Forest Dale, Hay had agreed to collect the money that evening.

After a light supper Hay told his wife that he had to go over to "Brother Mortensen's for a few minutes to collect a large sum of money" because "Brother Mortensen tells me he must leave town early in the morning, to be gone for a couple of days . . . and insists on paying it tonight."9 Aggie proceeded to put their three children to bed and then went to bed herself at 10:20. At midnight she awoke to find that her husband had not returned. Worried, she sat up until 3:00 A.M. when she went across the street to ask the Mortensens if they had seen her husband. Mortensen said that her husband had left earlier with the money and appeared to be going into town to give it to Ernest Romney. He then suggested that Hay might have missed the last tram back to Forest Dale and decided to stay downtown.10

By morning Aggie was frantic. Early that morning Mortensen had

8 Salt Lake Tribune, December 19, 1901;

Sunday School Union, 1900),

9 Salt Lake Tribune, December 19, 1901

10 Salt Lake Tribune, January 23, 1902.

28 Utah Historical Quarterly

Jubilee History of Latter-day Saints Sunday Schools (Salt Lake City : Deseret

p 310 Hay had previously served as second assistant superintendent of the Twentieth Ward Sunday School

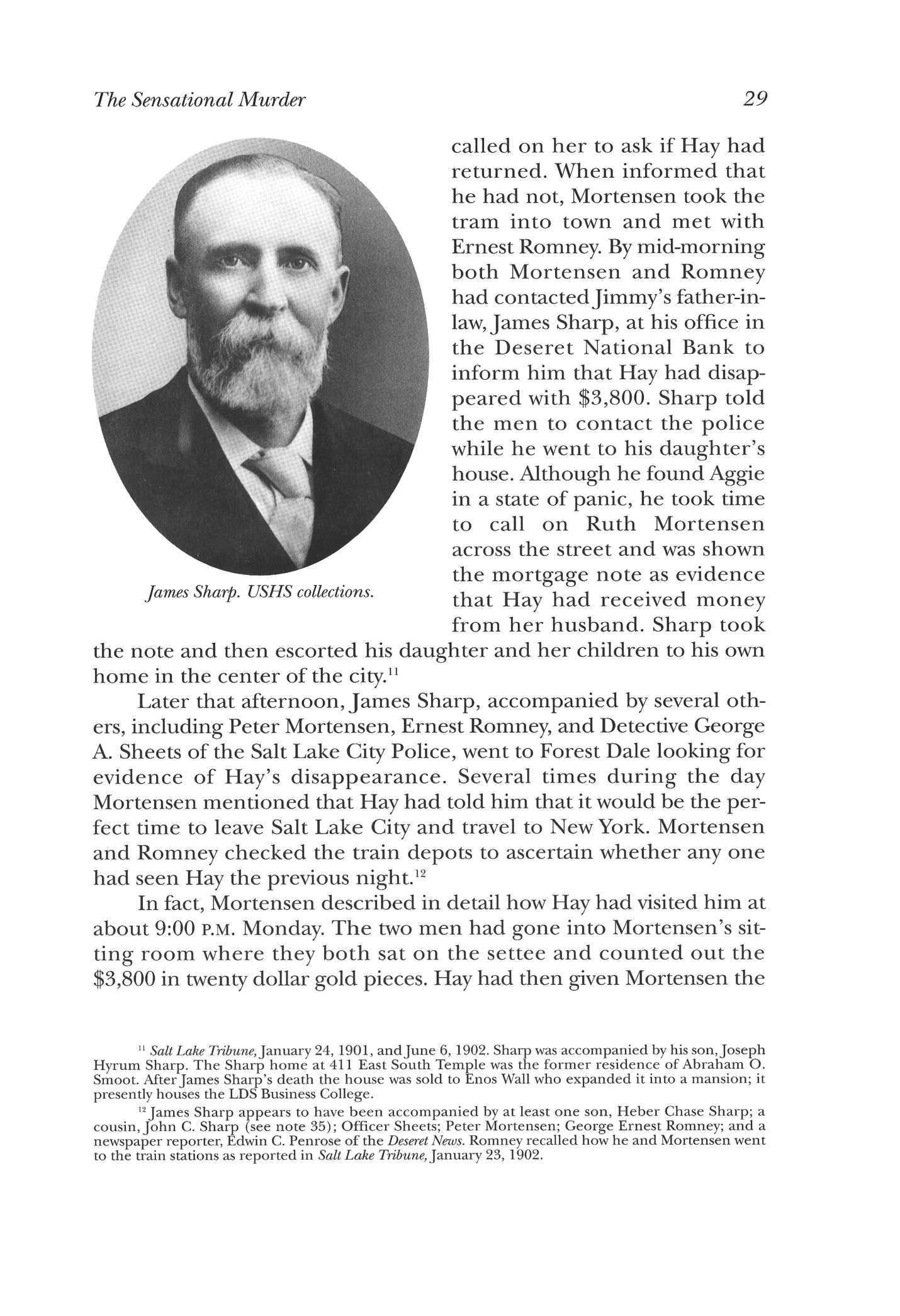

called on her to ask if Hay had returned When informed that he had not, Mortensen took the tram into town and met with Ernest Romney. By mid-morning both Mortensen and Romney had contacted Jimmy's father-inlaw,James Sharp, at his office in the Deseret National Bank to inform him that Hay had disappeared with $3,800. Sharp told the men to contact the police while he went to his daughter's house. Although he found Aggie in a state of panic, he took time to call on Ruth Mortensen across the street and was shown the mortgage note as evidence that Hay had received money from her husband. Sharp took the note and then escorted his daughter and her children to his own home in the center of the city.11

Later that afternoon, James Sharp, accompanied by several others, including Peter Mortensen, Ernest Romney, and Detective George A. Sheets of the Salt Lake City Police, went to Forest Dale looking for evidence of Hay's disappearance. Several times during the day Mortensen mentioned that Hay had told him that it would be the perfect time to leave Salt Lake City and travel to New York Mortensen and Romney checked the train depots to ascertain whether any one had seen Hay the previous night.12

In fact, Mortensen described in detail how Hay had visited him at about 9:00 P.M Monday The two men had gone into Mortensen's sitting room where they both sat on the settee and counted out the $3,800 in twenty dollar gold pieces. Hay had then given Mortensen the

The Sensational Murder 29

fames Sharp. USHS collections.

11 Salt Lake Tribune, January 24, 1901, and June 6, 1902 Sharp was accompanied by his son, Joseph Hyrum Sharp The Sharp home at 411 East South Temple was the former residence of Abraham O Smoot After James Sharp's death the house was sold to Enos Wall who expanded it into a mansion; it presently houses the LDS Business College

12 James Sharp appears to have bee n accompanied by at least one son, Heber Chase Sharp; a cousin, Joh n C Sharp (see note 35); Officer Sheets; Peter Mortensen; George Ernest Romney; and a newspaper reporter, Edwin C Penrose of the Deseret News. Romney recalled how he and Mortensen went to the train stations as reported in Salt Lake Tribune, January 23, 1902

receipt and took the money, after which Mortensen saw Hay out the door.

At the Mortensen house, James Sharp, by then very distraught, confronted Mortensen and demanded to be shown exactly where Jimmy had last been seen. Mortensen, who was on his porch, pointed down the walk and said that it was about where Sharp was standing. Unsatisfied, Sharp insisted that he be shown the exact spot. Hesitantly, Mortensen left the porch and walked to a spot about ten feet from the porch and twenty feet from the gate. Sharp exclaimed that the spot on which they were standing was where his son-in-law had been killed and that Mortensen was responsible "How do you know he is dead?" Mortensen asked. Sharp responded, "The proof is that within twentyfour hours his body will be dug up in a field within a mile of this spot."13

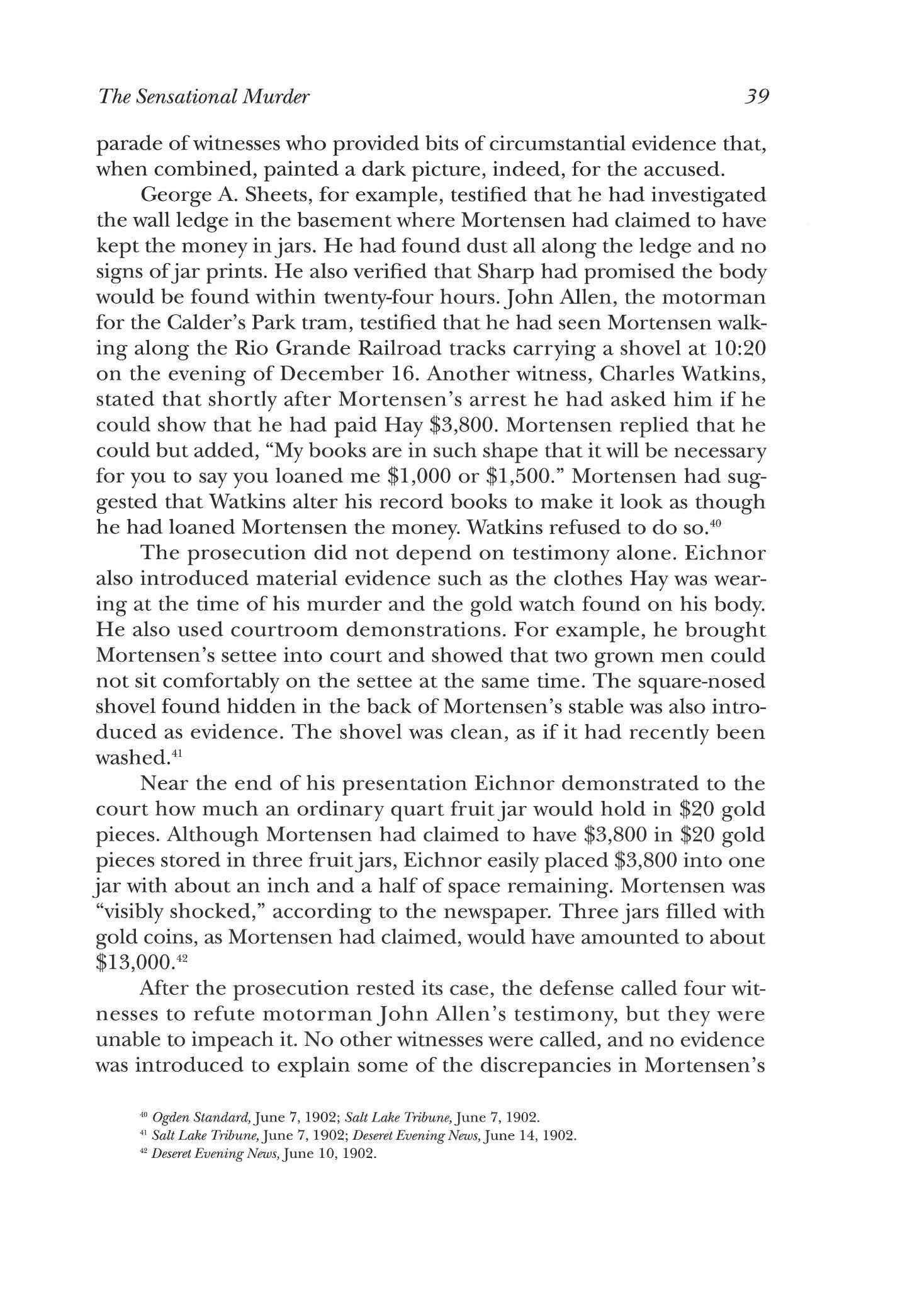

By Wednesday morning there was still no trace ofJimmy Hay. Mortensen was about to catch a tram into town when he and Royal B. Young14 were told by a young woman that "a body" (actually, what appeared to be a hastily dug grave) had been found. The two men rushed to the place where Frank Torgersen had been looking for a loose horse and stumbled upon a trail of blood and a mound of freshly turned earth The shallow grave was close to the tracks of the Park City Branch of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway, between Fifth and Seventh East streets, about a half-mile from Peter Mortensen's home. There was a large quantity of blood on the tracks.

Torgerson asked Mortensen if he had a shovel, since his house was closest to the grave site. Mortensen replied that he did, specifically stating that the only shovel he had was a round nosed one After retrieving the shovel, Mortensen and several others watched while Torgersen dug. As dirt was removed, marks clearly showed that a square shovel had been used to dig the grave originally. Several of the small crowd noted the marks and footprints leading to and away from the grave. When the group realized that the body was indeed Hay's, they contacted the police. 1 5 As the police exhumed the body, Mortensen paced back and forth nervously and acted as if he wanted to leave the gruesome scene When he finally headed toward his home

13 Salt Lake Tribune, January 24, 1902, and Salt Lake Herald, January 24, 1902 Present at the time of Sharp's statement were Mortensen, Heber Sharp, George Romney, reporter Edwin Penrose, detective George Sheets, and at least one other police officer.

14

15 Salt Lake Tribune, December 19, 1901, and Deseret Evening News, December 18, 1901

30 Utah Historical Quarterly

Royal Barney Sagers Young (1851-1929) was the adopted son of Brigham Young He and at least two of his three wives resided in Forest Dale He was president, secretary, and treasurer of Young Brothers Company which dealt in music, musical merchandise, bicycles, and sewing machines

The Sensational Murder

a policeman stopped him about halfway there, and he was soon placed under arrest for the murder ofJimmy Hay.

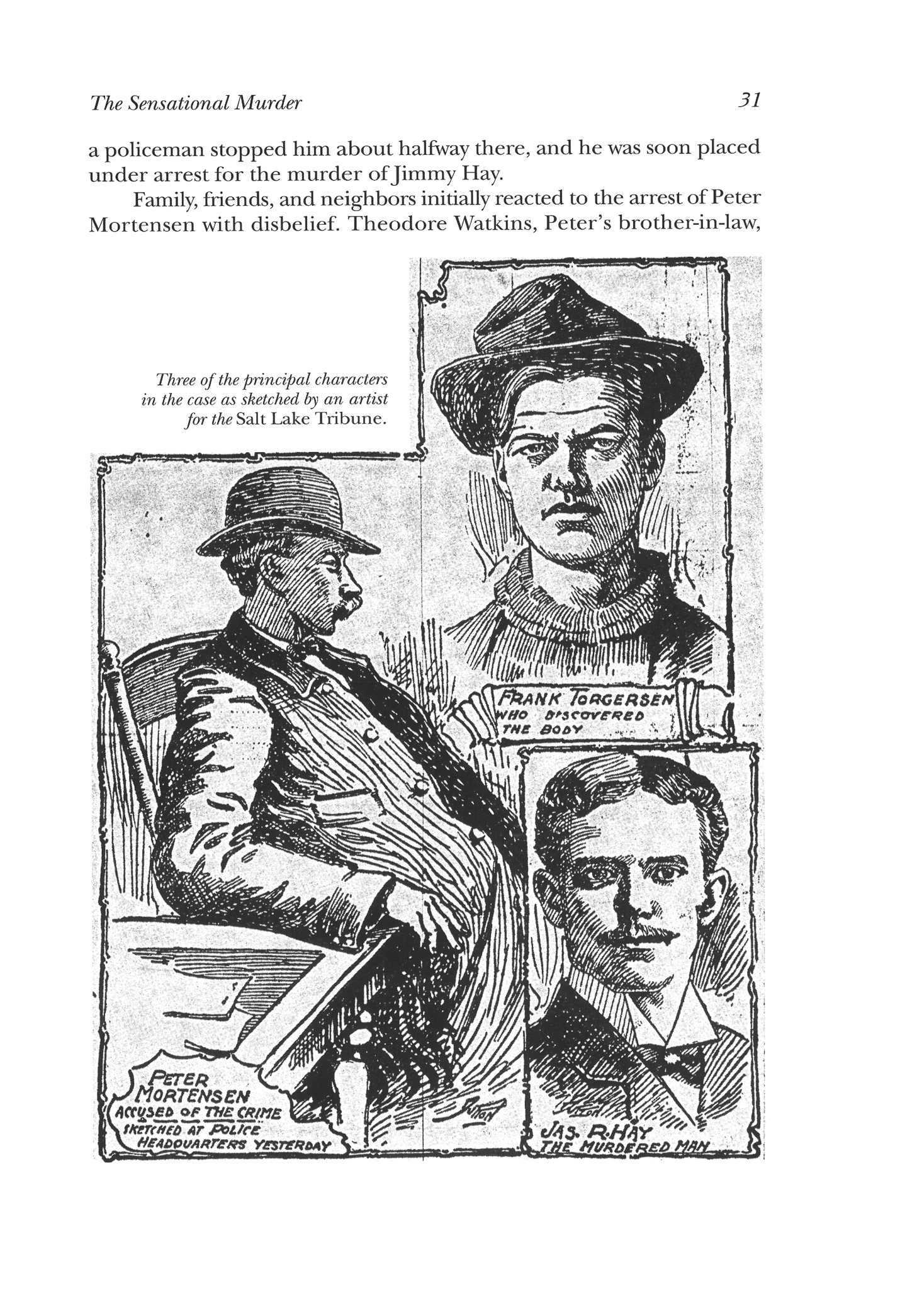

Family, friends, and neighbors initially reacted to the arrest of Peter Mortensen with disbelief. Theodore Watkins, Peter's brother-in-law,

31

Three of the principal characters in the case as sketched by an artist for the Salt Lake Tribune.

stated, "If I believed Peter were guilty of this horrible crime I would not lift a finger to save him from the penalty, but I know he never did it, and I will spend every cent I possess, if necessary to prove his innocence."16

Another brother-in-law, Richard C. Watkins, stated that he believed Peter was innocent and would investigate on his own. He added that even had he believed Mortensen to be guilty, he would take his sister, Ruth Mortensen, to his home in Provo. Ruth, for her part, was on the verge of a nervous breakdown and had secluded herself from the public

In the days following Mortensen's arrest the police, aided by members of the Sharp family and neighbors like Royal B. Young, searched and re-searched the Mortensen property for evidence. Despite great activity, they found little One significant discovery, though, was a recently washed square-nosed shovel hidden in the back of the Mortensen stable.

Hay had been killed by a shot to the back of the head from a .38caliber pistol The lengthy search of the Mortensen property and surrounding streets and fields conducted by the police failed to turn up the gun or Hay's missing hat.17

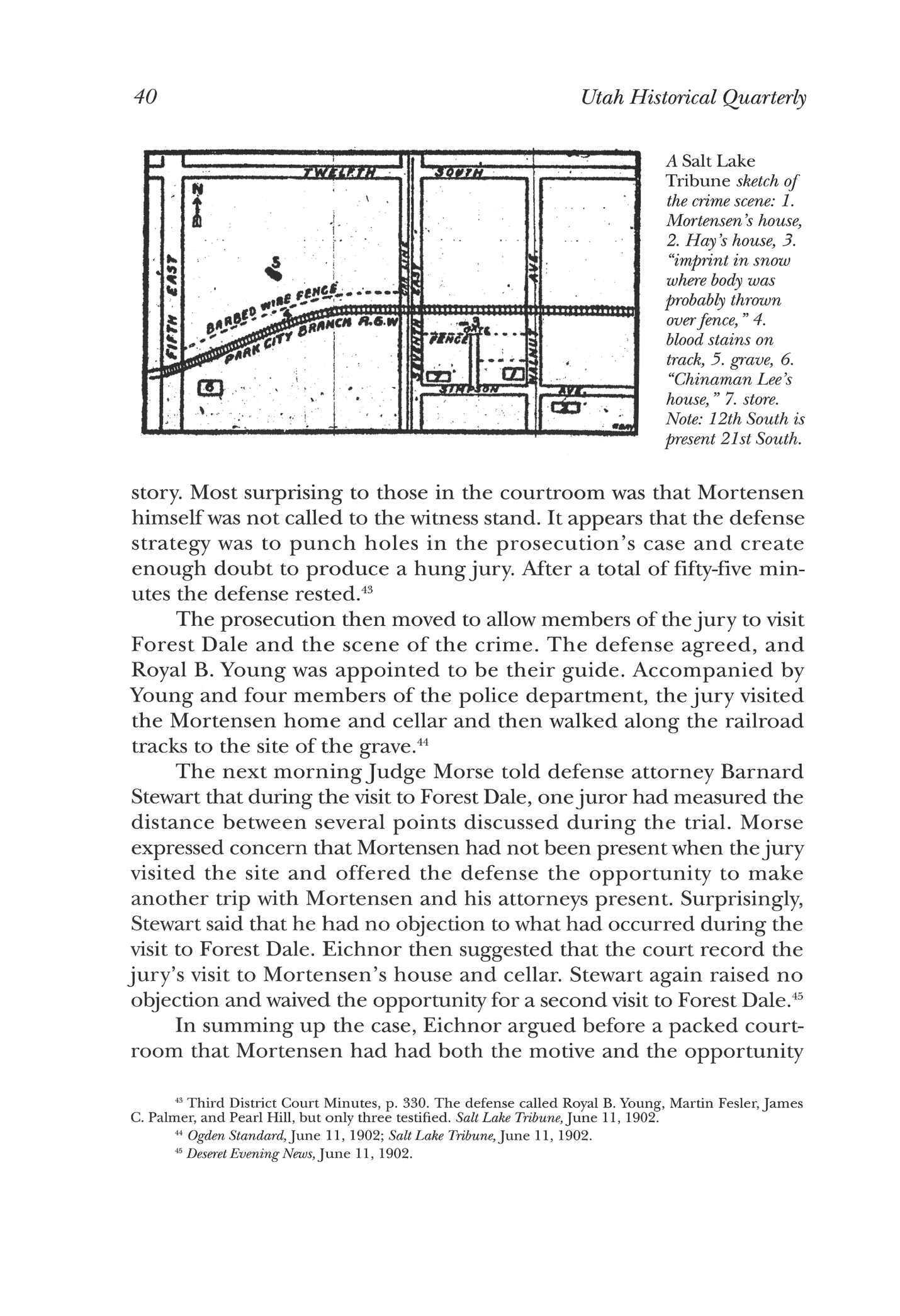

There was also a flurry of activity on the part of Mortensen's lawyers. Barnard J. Stewart, a friend and neighbor, was retained to defend Mortensen. He and his brother, Charles B. Stewart, quickly acted to keep reporters away from Mortensen and tried to have him released from jail.18 Despite their efforts to lessen publicity about the crime, the event and the circumstances surrounding it seemed to take on a life of their own. Every day, including Christmas, stories about the case and how Mortensen was reacting to the pressure appeared in the newspapers One day the headlines would read: "Mortensen is Breaking Down," while the next day's paper would carry the news that

16 Ogden Standard, December 20, 1901

17 Salt Lake Tribune, December 21, 1901 The gun and the hat were never found A pistol found two days after the discovery of Hay's body proved, after ballistics tests, not to be the weapon Numerous manhours were spent looking for the two items. In fact, a nearby pond was drained and thoroughly searched but produced no evidence

1S According to History of the Bench and Bar of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1913), pp 202-4, Barnard (misspelled Bernard in places) Joseph Stewart, a graduate of the University of Utah and the University of Michigan Law School, was admitted to the Utah Bar in 1900 Charles B Stewart, educated at the same institutions, became a member of the Utah Bar in 1893 An older brother, Samuel W Stewart, was also an attorney and sometime law partner of Barnard and Charles and later a judge. See also Biographical Record of Salt Lake City and Vicinity (Chicago: National Historical Record Co., 1902), pp 619-20; Chad M Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), pp 57-59, 76; and, "C B Stewart, Ex-Utahn, Dies in L.A.," Salt Lake Tribune, May 21, 1945 Barnard (1873-1931) and Charles (1870-1945) were both bor n in Draper, Utah, to prominent pioneer parents, Isaac M. and Elizabeth WTiite Stewart Both men married into prominent Mormon families Barnard married Leonora Mousley Cannon, daughter of Angus M Cannon, and Charles married Katherine Romney, daughter of Bishop George Romney and half-sister to Ernest Romney who later served as a witness for the prosecution Barnard lived his entire life in the Salt Lake Valley; Charles later moved to Los Angeles

32 Utah Historical Quarterly

he was "feeling better." That, added to announcements of new witnesses and new doubts created a circus-like atmosphere.19

At about the time that James Hay was being laid to rest, Ruth Mortensen left with her children and brother Richard for Provo. She did not visit her husband injail before she left. In fact, after his arrest she never again saw him. The newspapers had reported that she was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, at times bordering on uncontrollable hysteria Although she had originally defended her husband and offered him a reasonable alibi, by December 23 she had changed her story and, at the insistence of her brother, told the police what she knew.

According to Ruth, Hay had visited Mortensen on that fateful Monday night a little after 9:00 P.M. and, after about a half-hour, they had left the house together. In about twenty minutes Mortensen returned, breathless and red in the face. He told his sister-in-law, Henry's wife, who happened to be visiting, that if she wanted an escort back to her house, she had better hurry for he had "some work to do." He again left the house and was gone for about an hour.20 When Mortensen returned, his wife realized something was wrong, for he looked "simply ghastly" and appeared "so pale and . . .had a wild look in his eyes." She asked him what was wrong, but he refused to answer and went to bed where he pretended to sleep. After awhile, Ruth again asked what had happened and he again refused to answer. Later, when Aggie Hay came to the house and called out for Peter, he did not respond until, at Ruth's urging, he went and talked with her. After he had returned to bed, Ruth asked what he had done with Jimmy Hay. Peter became angry and said, "Don't you ever mention Hay's name to me again." When Ruth threatened to tell Aggie everything she knew, Peter said, "No you won't, even if you hear Hay is dead you must not say how long I was out last night."21 Although Ruth's testimony to the police was damaging, it was never used in court as it was

19 Deseret Evening News, December 21, 1901, and Salt Lake Tribune, December 23, 1901 As an example of the sensationalism produced by the press, a short article, "The Hoodoo House," in the Salt Lake Tribune, December 29, 1901, noted thatJames R. Hay had once lived in a house where two previous owners died tragically Hay, the newspaper opined, may have succumbed to the curse of that house The public displayed a morbid fascination with the crime also According to the Tribune, December 24, 1901, crowds of curious people were destroying the Mortensen property Hundreds had filed in and out of the Mortensen home and visited the burial site. The lawns and gardens had been trampled down by the numerous visitors, and some were bold enough to carry away tools and other personal household items as souvenirs Elizabeth Jane Hay Zobell in a telephone interview on November 14, 1994, said her mother told her that the tops of the picket fence around the yard were torn off by curiosity seekers as souvenirs of the victim's house

20 Salt Lake Tribune, December 24, 26, 1901; Ogden Standard, December 24, 26, 1901

21 Ogden Standard, December 26, 1901 After Ruth Mortensen told the police all she knew, she evidently felt as if a great weight had been taken from her Family members later reported that her nervousness had left her and that she was more cheerful

The Sensational Murder 33

contrary to the law for a spouse to testify against a mate without that person's prior consent.

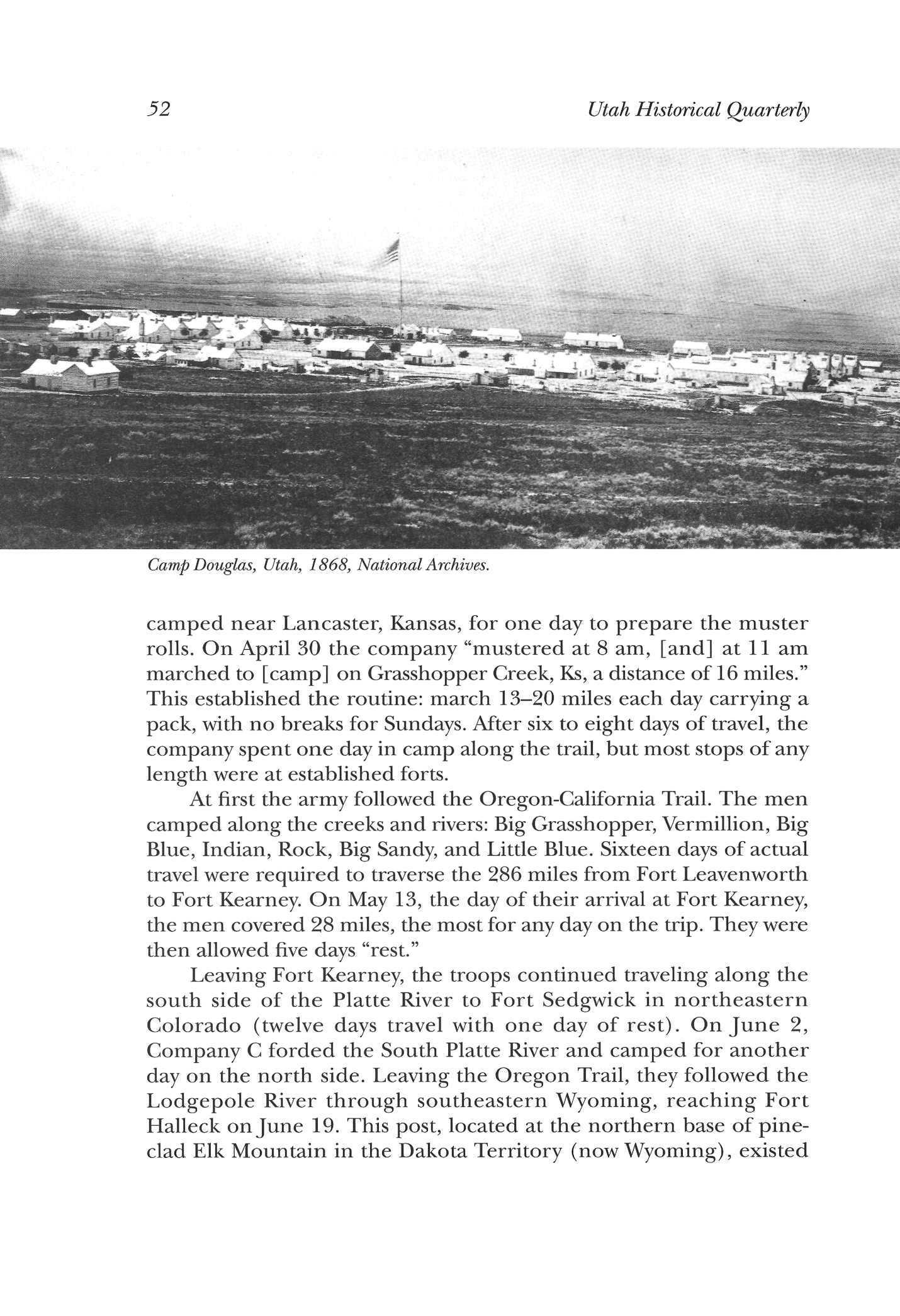

While the evidence continued to mount against him, Peter strongly maintained his innocence. At one point he stated to the press, "There is no punishment too severe for the murderer of Hay" and went on to again emphatically state his innocence.