CO H M CO CO \

UTA H HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOAR D O F EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City, 1997

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1997

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 1999

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden, 1998

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1999

RICHARD S. VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 3J4 inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y

Contents

FRONT COVER, clockwise from upper left: Historic Sites Fun Run, May 1978, sponsored by the preservation staff; tour of historic Spring City during 1975 Annual Meeting; USHS Fellow Helen Z Papanikolas researching at Kearns mansion; Society director Max f. Evans as Western Union agent who fired shot signaling statehood at centennial reenactment onJanuary 4, 1996 (photograph courtesy o/Deseret News); Evelyn Partner showing preschoolers how to pull handcart replica in museum.

BACK COVER, clockwise from upper left: Lucy Valeria and Stanford]. Layton during 1976 DominguezEscalante expedition bicentennial; California schoolteacher Todd I. Berens, left, on a visit to the Society with students researching historic trails; USHS Fellow Dale L. Morgan in a lighthearted moment; Linda Thatcher and David Merrill inventorying library holdings prior to move from Kearns mansion; 1979 Annual Meeting in San Juan County included tour of antiquities section salvage dig at White Mesa; USHS FellowJuanita Brooks autographing'Hot by Bread Alone: The Journal of Martha Spence Heywood, 1850-56, at party in May 1978; Society trek to Promontory in 1969; Philip F. Notarianni, right, and his nephew Ronald S. Johnson, secondfrom left, demonstrating traditional Italian sausage making in Kearns mansion kitchen for a Beehive History article asJohn S. H. Smith, Larry Jones, and Linda Edeiken watched. Photographs, exceptas noted, arefrom USHS collections.

© Copyright 1997 Utah State Historical Society

SUMMER 1997 \ VOLUME 65 \ NUMBER 3 IN THIS ISSUE 199 ONE HUNDRED YEARS AT THE UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY GARY TOPPING 200 BOOK REVIEWS 303 BOOKNOTICES

308

STERLING M. MCMURRIN and L.JACKSON NEWELL Matters ofConscience: Conversations with Sterling M. McMurrin on Philosophy, Education, and Religion .BRIGHAM D MADSEN 303

RICHARD W ETULAIN Re-imagining theModern American West: A Century ofFiction, History, and Art ROBERT C. STEENSMA 304

BRIAN Q CANNON Remaking the Agrarian Dream: New Deal Rural Resettlement in the Mountain West F. ALAN COOMBS 305

ANNE BRUNER EALES. Army Wives on the American Frontier: Living bythe Bugles MARK R. GRANDSTAEF 306

Books reviewed

In this issue

Almost lost amid the parades, speeches, and other kinetic excitement of the Golden Jubilee in July 1897 was the meeting of a few dozen Utahns at the Templeton Hotel in Salt Lake City Gary Topping. to create a state historical society. Yet, when the last float was nothing more than a fading image in a wide-eyed child's memory and the final hyperbolic speech had dissipated into the summer air, the organizational work of those history-minded visionaries was already beginning to prove itself as the greatest legacy of that grand celebration.

From its modest beginnings of a century ago, the Utah State Historical Society has grown to 3,000 members, developed a research collection of over a million items, published over 250 issues of Utah Historical Quarterly, led the historic preservation movement in Utah for a quarter century, offered grants and technical assistance in support of local history initiatives, created energetic antiquities and museums programs, and much more Such growth and success did not occur without setbacks, frustrations, and other difficulties. Fortunately, men and women of foresight, commitment, good humor, and an enduring love of Utah history have always been there to guide the organization along the path outlined on July 22, 1897

It is time to tell the story of those me n and women. The editorial staff of Utah Historical Quarterly commissioned Gary Topping, a former Historical Society staffer and present professor of history at Salt Lake Community College, to do the job Employing all the skills of the true professional, Dr Topping spent two years examining the pertinent sources, interpreting the facts with reasoned and mature judgment , placing all key developments within larger contexts, and packaging it all in a lively, entertaining narrative. His achievement is more than worthy of that great promise which animated the Society's perspicacious founders a century ago. Find a cool and quiet place, turn the page, and enjoy a nifty trip down history's lane.

Rich County'sfloat heads down Main Street during the huge parade ofJuly 22, 1897, celebrating thefiftieth anniversary of Mormon pioneer arrival in the Salt Lake Valley. Note Brigham Young Monument unveiled three days earlier. In this time of heightened historical awareness, a group of citizens met on the evening of the grand parade day tofound the Utah State Historical Society. All photographs arefrom USHS collections unless noted otherwise. Opposite: Notice in fAeDeseret News of the Society's July 22 organizational meeting.

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society

BY GARY TOPPING

BY GARY TOPPING

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 201

SPECTACULAR SCENE THE LIKE OF Which Was Never Before Witnessed in the West"

blared the Deseret Evening News on July 22, 1897, and for once pioneer western journalism, infamous for hyperbole, was not exaggerating. It was the climax of a week-long blowout of patriotic energy celebrating the Golden Jubilee, the fiftieth anniversary of the first Mormon pioneers' entrance into the Salt Lake Valley. Beginning on July 19 with the unveiling of the Brigham Young Monument at South Temple and Main streets, the festivities would continue until July 24 with full daily schedules of parades, concerts, theatrical and musical performances, and speeches.

Historical Society Call,

To th e People of Utah :

Believing tho "Jubile o celebration" of th e adven t of the Pioneer* an appropriate tim e for the founding of a society, which shall have for Its objects the en • oour&gomcnt of historical research ami inquir y by iho exploration and investigation of aboriginal monument " and remains , the collection of such materia! a« ma y serve to illustrate itae trowth of Uta h and tho intermnuutai n region, tho preservation in a permanen t depositor:' of manuscripts , documents, papers an 1 tracts of value; the dissemination of information and the holding of meetingM at stated interval* for tha interchange of views and criticisms, the undersigned tak e this mod e of asking ail who ma y L>> , disposed to aid m such an undertakin g to mee t at th e Templeton hotel in Salt 'juk i Ctty on Thurtda y the 22nd day of *'uiy, 1897 at 4 p.m., for the purpose of taking th e necessary t»tcp« looking to the iucorpora'io n of KD organization io be known a t "Th e Ua h Stato Historical Society."

It is desired that every soction of th ? State should be represented Salt Lak e City, Utah, Jul y 15, 1897

Holier M Well*

Joh n R Winde r

J T Hammon d

A C Bishop

Y D Ricnarda

O W Power s

C S Zir.f

AqniHa Nebokor

A O Smoot

Joh n Henr y Smit h

O F Whitne y

L.S Hills

Joh n Q Cannon

J K rwoly

R \V Youn g

U V Xioodwin

W m A Lee

L VV Shurtlltf

Artiiu • Prat t

Thoma s Marshall

Gran t H iSmitb

Charles Admi x

Morri- L Ritchie

Mat Thoma s

Kllen H Ferguson

I>ai;ells CameronBrown

W S McCornick

Na t M Brigha m

11 W Lt.wreuce

Kmma J MoVictter

Eiias A Smit h

Angu s M Cannon

Aifiil^H Youn g

C V7 Penrose

K W Wilson

FSwinelitio B Wells

F « Richards

Wiiliam Howar d

V W B«nnett

P L Wiiliams

Joh ' "* nine

• ;i ; a .^e

Kle .nl' »ck

Joh n T Lync h

Hadlev DJohneo n

() It Bairati

Edwar d P eolborn

Horace O Whitne y

II C Hill

Ruritiie'.: LelJarlhe O W Thatche r

R N Buskin Spencer Cluwson

H F McCune

Chrim Dithi

Robert C Lun d

Jerrold R Letcher

The immense parade of July 22, however, was surely the most extravagant event of the celebration To the News the parade seemed to be almost as much about hydroelectric power as about history, for the estimated one hundred thousand spectators were flooded with illumination from red, yellow, green, and blue incandescent bulbs whose beams bounced from colorful bunting crisscrossing the street from the rooftops. "No more tangible evidence can be found," the reporter exulted, "that Utah is in the van of the electric age, than the marvelous display of lights that have greeted the sight seer night after night during the Jubilee."

Dr Topping is assistant professor of history at Salt Lake Community College and a member of the Advisory Board of Editors of Utah Historical Quarterly. From 1979 to 1991 he served as curator of manuscripts at the Utah State Historical Society He is the author of numerous historical articles and reviews and will have two books published in 1997: Gila Monsters and Red-eyed Rattlesnakes: Don Maguire's Arizona Trading Expeditions, 1876-79 and Glen Canyon and the San Juan Country.

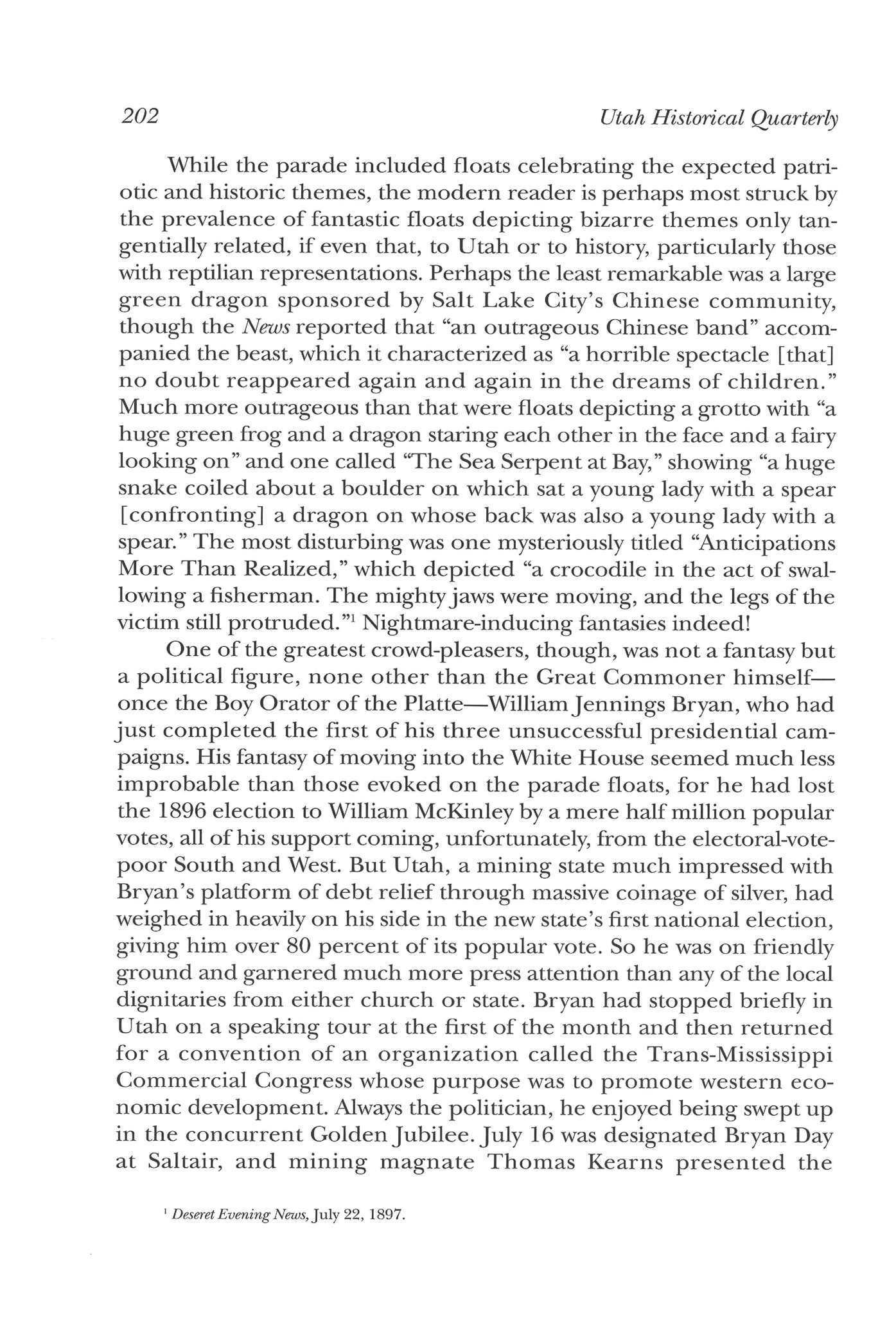

While the parade included floats celebrating the expected patriotic and historic themes, the modern reader is perhaps most struck by the prevalence of fantastic floats depicting bizarre themes only tangentially related, if even that, to Utah or to history, particularly those with reptilian representations. Perhaps the least remarkable was a large green dragon sponsored by Salt Lake City's Chinese community, though the News reported that "an outrageous Chinese band" accompanied the beast, which it characterized as "a horrible spectacle [that] no doubt reappeared again and again in the dreams of children." Much more outrageous than that were floats depicting a grotto with "a huge green frog and a dragon staring each other in the face and a fairy looking on" and one called "The Sea Serpent at Bay," showing "a huge snake coiled about a boulder on which sat a young lady with a spear [confronting] a dragon on whose back was also a young lady with a spear." The most disturbing was one mysteriously titled "Anticipations More Than Realized," which depicted "a crocodile in the act of swallowing a fisherman. The mighty jaws were moving, and the legs of the victim still protruded."1 Nightmare-inducing fantasies indeed!

One of the greatest crowd-pleasers, though, was not a fantasy but a political figure, none other than the Great Commoner himself— once the Boy Orator of the Platte—William Jennings Bryan, who had just completed the first of his three unsuccessful presidential campaigns. His fantasy of moving into the White House seemed much less improbable than those evoked on the parade floats, for he had lost the 1896 election to William McKinley by a mere half million popular votes, all of his support coming, unfortunately, from the electoral-votepoor South and West. But Utah, a mining state much impressed with Bryan's platform of debt relief through massive coinage of silver, had weighed in heavily on his side in the new state's first national election, giving him over 80 percent of its popular vote. So he was on friendly ground and garnered much more press attention than any of the local dignitaries from either church or state. Bryan had stopped briefly in Utah on a speaking tour at the first of the month and then returned for a convention of an organization called the Trans-Mississippi Commercial Congress whose purpose was to promote western economic development. Always the politician, he enjoyed being swept up in the concurrent Golden Jubilee. July 16 was designated Bryan Day at Saltair, and mining magnate Thomas Kearns presented the

202 Utah Historical Quarterly

1

22,

Deseret Evening News, July

1897

Commoner with an ornate cup fashioned from silver and gold in the ratio of sixteen to one, symbolizing the bimetallic currency standard upon which his political campaign had been based.2

If Bryan happened to read the Deseret Evening News on the afternoon of July 21, he would have been pleased with its report of his enthusiastic reception the previous evening at a patriotic musical program in the Tabernacle and its verbatim coverage of an impromptu speech he had given at the conclusion in response to clamorous audience demand. Appropriate to the occasion, his remarks struck a historical note, emphasizing the need to keep alive the memory of the state's pioneer heritage:

As I watched the unveiling of the monument to Brigham Young this morning, I wondered how long would live die story of thejourney across the Plains If men have kept for three thousand years the tale of the search for the golden fleece, how much longer will they remember the history of this successful search for wealth, for prosperity, for greatness which you commemorate. 3

As his eye drifted down the page, Bryan may have been struck by a couple of notices that echoed his historical theme. One was an appeal by H. W. Naisbitt for the loan of "relics of the first pioneers or of Nauvoo days, or any objects of historic interest," to be placed in the "Hall of Relics" which had been drawing unexpected throngs of visitors during the Jubilee. In fact, the special white building had been "crowded to its utmost capacity by visitors from all sections of Utah and from surrounding states and territories."4

In addition, Bryan could not have failed to notice a "Historical Society Call" addressed to the people of Utah and inviting all interested persons to an organizational meeting at the Templeton Hotel on July 22 to form a Utah State Historical Society The proposal may not have been news to him, for all of the fifty-seven undersigned backers were prominent Utahns and several were either Bryan Democrats or Republicans well known to him: Gov. Heber M. Wells,John Q. Cannon, Judge C. C. Goodwin, Dr. Ellen B. Ferguson, Henry W. Lawrence,

- Thomas G Alexander, "Political Patterns of Early Statehood" in Richard D Poll, ed., Utah's History (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), p 414 Richard Hofstadter says Bryan's political career had been bankrolled in part by Utah silver interests since 1892; see The American Political Tradition & the Men Who Made It (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1948), p 193 Bryan Day is described in the Deseret Evening News, July 17, 1897 Ironically, both Salt Lake City newspapers at this time were carrying ongoing reports of the Klondike gold strike that would shortly expan d the country's gold supply an d effect national debt relief without the necessity of adding to the silver in circulation, thus dooming Bryan's 1900 campaign on that issue

3 Deseret Evening News, July 21, 1897

4 Ibid

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 203

Abraham O. Smoot, Alfales Young, Franklin S. Richards, and Jerrold R. Letcher. The call, moreover, was dated July 15, the very day of Bryan's arrival in Salt Lake City, and it seems inconceivable that the Commoner's friends who had worked untold hours to solicit such highpowered backing for the project would not have mentioned it in some way during the previous week. And perhaps it is not even speculating too remotely that it was recent discussions with his historically minded friends that had borne spontaneous fruit in his Tabernacle remarks.

Credit for creation of the Utah State Historical Society belongs, more than anyone else, to an aggressive lawyer-journalist, a Bryan backer and friend, whose name appears with inappropriate modesty at the very end of the callers of the organizational meeting, Jerrold Ranson Letcher.5 He was, frankly, a carpetbagger who had arrived in Salt Lake City in 1890 at the age of thirty-nine to seek his fortune in law and politics A native of Missouri, he was educated in the public schools of that state and received the LL.B degree from the law school of Missouri State University in 1875. After briefly practicing his profession in Missouri, he moved to Ouray, Colorado, in 1878. There he became active in Democratic politics, representing his district in

204 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Historical Society was organized in the Templeton Building on the southeast corner of South Temple and Main Street on July 22, 1897.

5 Although no press reports during Bryan's visit link him with Letcher, the latter's wife is listed twice as one of Mary Bryan's intimates during her visit: at an immense reception in the City and County Building on July 14 (Mary Bryan had preceded her husband's arrival) and at a small luncheon on July 15 at the home of Mrs Joseph L Rawlins Deseret Evening News, July 15-16, 1897

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 205

the state legislature and his party at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1884

Upon moving to Utah, Letcher immediately began promoting the development of state political parties along the lines of the national parties, which he hoped would replace the political dominance of the Mormon church with a more democratic structure. Thus he formed a Democratic party journal and acted as its reporter while helping in the formation of "democratic societies" in the interest of nationalizing Utah party politics.

The year 1894 was a big one for Letcher. For one thing, he married Sarah Black, a Missouri schoolteacher. Also, he became a member of the last Utah Commission. This five-member body had been created in 1882 to oversee enforcement of the Edmunds Act of that year, a federal law that, among other things, disfranchised polygamists. It was the commission's responsibility to supervise Utah elections in accordance with the act's qualifications for voting and to see that the resulting legislature passed electoral laws in conformance with national standards. Not surprisingly, Utah Mormons regarded the commission as one in a series of examples of obnoxious federal meddling in local affairs. Although it is impossible to measure the temperature of Letcher's anti-Mormonism, statehood for Utah was evidently his prized goal rather than persecution of Mormons, and when the new state constitution had been approved by Congress, Letcher was a member of the delegation that transmitted it to President Grover Cleveland for signature.6

That Letcher's membership on the Utah Commission was not interpreted by Mormons as intended persecution is eloquently

6 Biographical sketches of Letcher appear in Noble Warrum, Utah Since Statehood (Chicago: S J Clarke Publishing Co., 1919), vol 3, pp 565-66; and History of the Bench and Bar of Utah (Salt Lake City: Interstate Press Association, 1913), pp 164—65 A concise account of the Utah Commission is in Gustive O. Larson, "The Crusade and the Manifesto," in Poll, Utah's History, pp. 268-71.

Jerrold R. Letcher, the driving force behind the Historical Society'sfounding, from Bench and Bar of Utah.

demonstrated by his effectiveness in enlisting prominent Mormons to support and participate in the Utah State Historical Society. The roster of signatories of the "Historical Society Call" is remarkable for its balance between non-Mormons (one might even say anti-Mormons) like Judges Charles S. Zane, Orlando W. Powers, and C. C. Goodwin and Mormon bluebloods like Franklin D. and Franklin S. Richards, Charles W. Penrose, and John T. Caine. Letcher's respect and influence in Utah society is also exhibited in the power and wealth represented on the roster, from Governor Heber M. Wells, Secretary of State James T. Hammond, and former Chief Justice Zane to the wealthy John E. Dooly and H. F. McCune. Finally, Letcher recognized the importance of women in Utah cultural life by enlisting Dr. Ellen B. Ferguson, Isabella CameronBrown, Eurithe K. La Barthe, Emma J. McVicker, and Emmeline B. Wells.7

Why form a historical society at all and why at that particular time? There is an obvious and simple answer in the interest in history naturally aroused by the pioneer Golden Jubilee. That emotional impetus, the organizers hoped, could be carried through to institutional expression. The "Historical Society Call" began by recognizing that "the 'Jubilee celebration' of the advent of the Pioneers [is] an appropriate time for the founding of a society."8

There are other reasons, though, that challenge us to probe more deeply into contemporary historical and psychological forces and developments, both in Utah and the nation at large. To begin at the national level, America in the 1890s was experiencing a complex crisis, a crisis so fundamental that Henry Steele Commager has referred to

7 Deseret Evening News, July 21, 1897

8 Ibid

206 Utah Historical Quarterly >

Legislator Eurithe K. LaBarthe was among those who endorsed the call to organize a historical society.

the decade as "the watershed of the nineties." 9 Utahns were not immune to that crisis, despite the fact that, as Dale Morgan has said, Utah has written the most "cross-grained" chapter in American history. Prompted by the process of what Gustive O. Larson has called "the Americanization of Utah"—the bringing of Utah social mores and institutions into conformity with national standards in preparation for statehood—Utah Mormons were beginning to think of themselves as Americans No longer were they able, as they once had been, to dismiss national misfortunes as merelyjust deserts for sinful ways

The inescapable focal point of the crisis of the nineties was the great economic depression inaugurated by the Panic of 1893 and lasting until 1897. That depression, the worst in American history to that point, had called attention to the existence of other problems that seemed to indicate fundamental flaws in the American way of life. For one thing, it had contributed to outbursts of farm protest in the Populist movement and labor violence in the Homestead and Pullman strikes. It had called attention to the extent of the new consolidation in such corporate innovations as the pool and the trust, which seemed to doom competition within free enterprise as a major economic force. Americans were also becoming aware of the immense decline in civic virtue as the corrupt business practices of the robber barons had spread into politics at all levels. They knew of the annual torrent of immigration bringing hordes of apparently unassimilable aliens who created urban slums. Finally, although in reality vast quantities of public land still remained available, Americans were becoming worried about increasingly restrictive economic opportunities attendant upon the announced closing of the frontier. In the face of this complex crisis, then, which seemed to call into question the validity of some of America's most fundamental values and institutions, it is natural that a tendency toward introspection would develop and that much of that introspection would focus on the historical development of those now challenged values and institutions.

Utahns had reasons within their own history and culture for such introspection as well. In the half century since the arrival of the first

9 Henry Steele Commager, The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since the 1880's (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), pp. 41-54. In addition to Commager, my thesis which follows is based on Henry F May, The End ofAmerican Innocence: A Study of the First Years of Our Own Time, 1912-1917 (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1959), and especiallyJohn Higham, "The Reorientation of American Culture in the 1890's," in Writing American History: Essays on Modern Scholarship (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970), pp 73-102; and Richard Hofstadter, "Cuba, the Philippines, and Manifest Destiny," in The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), pp.

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 207

Mormon settlers, Utah history had seen some of the most fundamental changes imaginable. Rather like the Puritan "errand into the wilderness" of seventeenth-century New England, the great Mormon migration was inspired by the opportunity to create an ideal social order. Drawn by that inspiration, thousands uprooted themselves from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and elsewhere to live in a collectivist society in one of the most remote parts of the earth under the centralized leadership of the Mormon hierarchy.

If that uprooting, relocating, and adapting to a radically new way of life in a harsh environment were not disorienting enough, immigrants and other outside influences almost from the beginning forced fundamental alterations in the Mormon way of life As early as 1850 the influx of gold rushers and the achievement of territorial status marred Mormon isolation. Discontent with the hostile, federally appointed governors and judges was a nagging feature of the territorial period, leading at one point to an invasion of the territory by federal troops The transcontinental railroad began an integration of Utah into the national economy. The polygamy prosecutions of the 1880s caused immense disruptions in Utah society and greatly exacerbated the already raw feelings between Utah Mormons and the nation at large. Now, during the turbulent nineties, Utah had begun a wholesale reversal of its cross-grained traditions in order to gain statehood. Surely it is no wonder that Utahns, Mormon and non-Mormon alike, might be asking who they were in the midst of those apparently contradictory influences and experiences. If the culture at large was experiencing an identity crisis, the bewilderment must have been doubly acute in Utah Beyond the parades, the speeches, the musical festivities, the monument unveilings, beyond the innocent celebration of pioneer greatness and the gawking throngs filing through the Hall of Relics, lurked some very serious questions in the minds of thoughtful people. It was time to begin looking within, to begin examining the contradictory process that had brought Utah to its present circumstance, and to try to plan a future based upon its best traditions. The focal point for that introspection would be a state historical society. While the crisis of the 1890s and the convoluted nature of Utah history gave a particular urgency to the forming of a historical society, on the other hand Utah was following a familiar pattern. Throughout American history, state historical organizations have appeared sometime after the closing of the pioneer period as residents have recognized their emergence into a new era of settled civilization and have

208 Utah Historical Quarterly

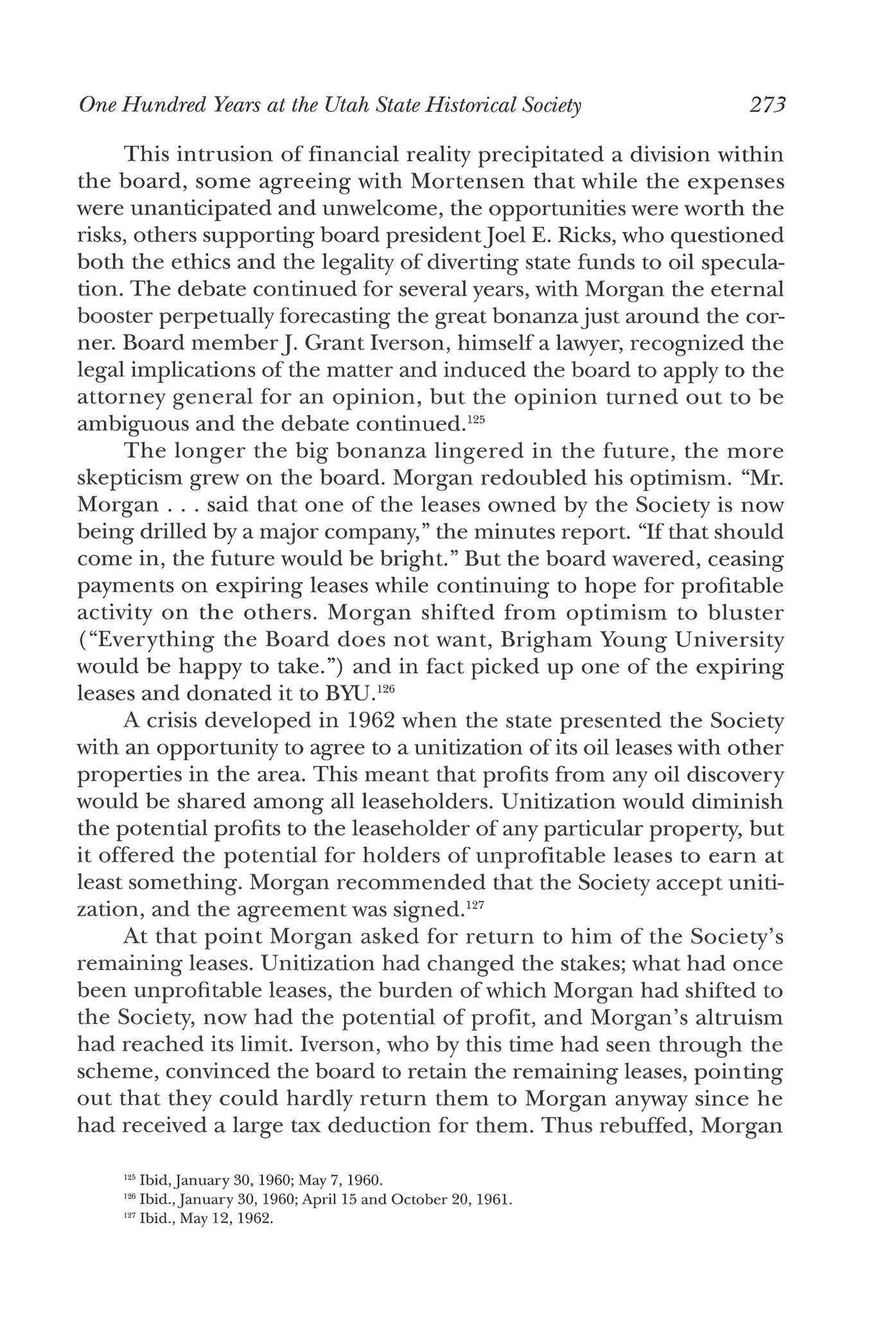

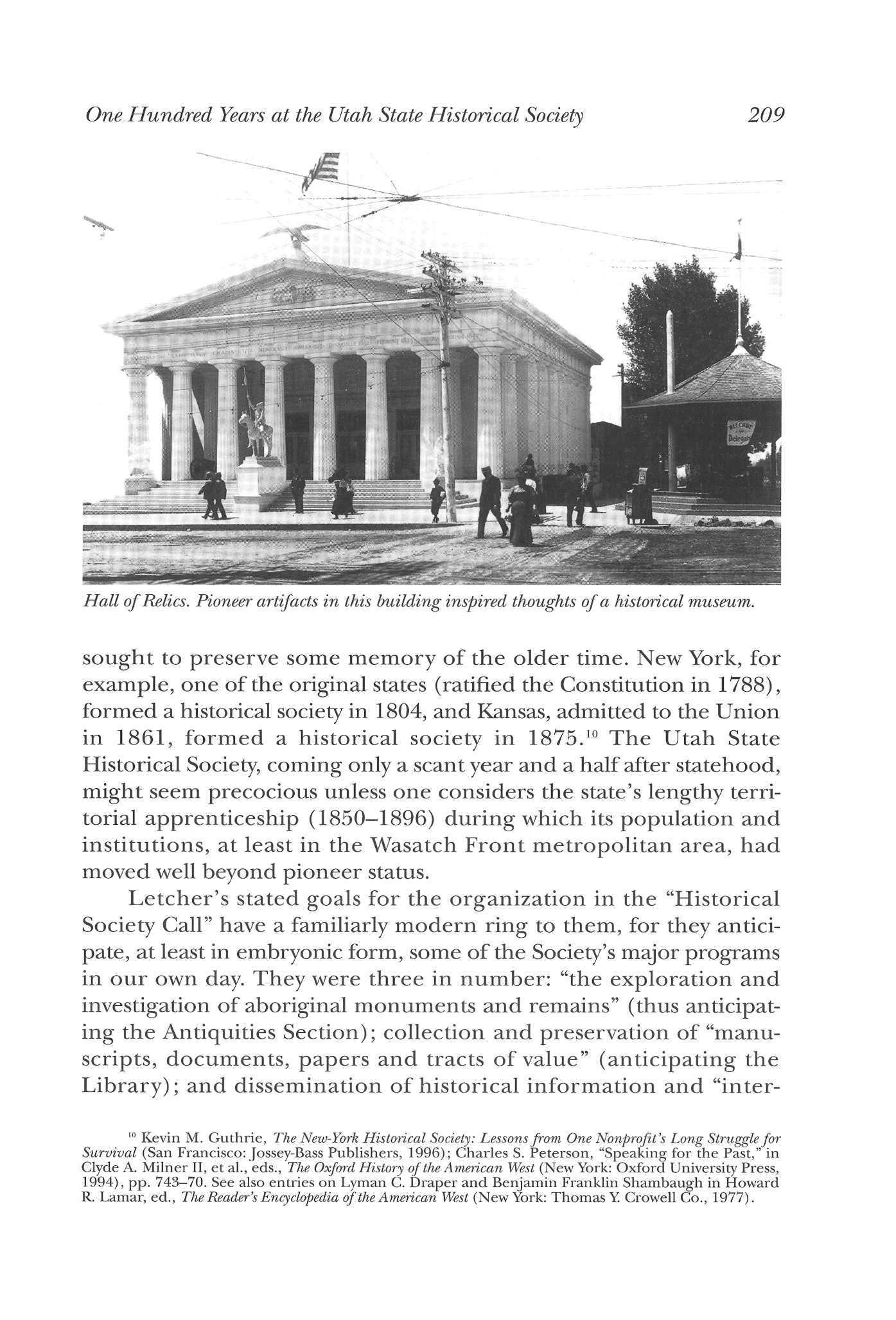

sought to preserve some memory of the older time. New York, for example, one of the original states (ratified the Constitution in 1788), formed a historical society in 1804, and Kansas, admitted to the Union in 1861, formed a historical society in 1875.10 The Utah State Historical Society, coming only a scant year and a half after statehood, might seem precocious unless one considers the state's lengthy territorial apprenticeship (1850-1896) during which its population and institutions, at least in the Wasatch Front metropolitan area, had moved well beyond pioneer status.

Letcher's stated goals for the organization in the "Historical Society Call" have a familiarly modern ring to them, for they anticipate, at least in embryonic form, some of the Society's major programs in our own day. They were three in number: "the exploration and investigation of aboriginal monuments and remains" (thus anticipating the Antiquities Section); collection and preservation of "manuscripts, documents, papers and tracts of value" (anticipating the Library); and dissemination of historical information and "inter-

10 Kevin M Guthrie, The New-York Historical Society: Lessons from One Nonprofit's Long Struggle for Survival (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1996); Charles S Peterson, "Speaking for the Past," in Clyde A. Milner II, et at , eds., The Oxford History of the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), pp 743-70 See also entries on Lyman C Draper and Benjamin Franklin Shambaugh in Howard R Lamar, ed., The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West (New York: Thomas Y Crowell Co., 1977)

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 209

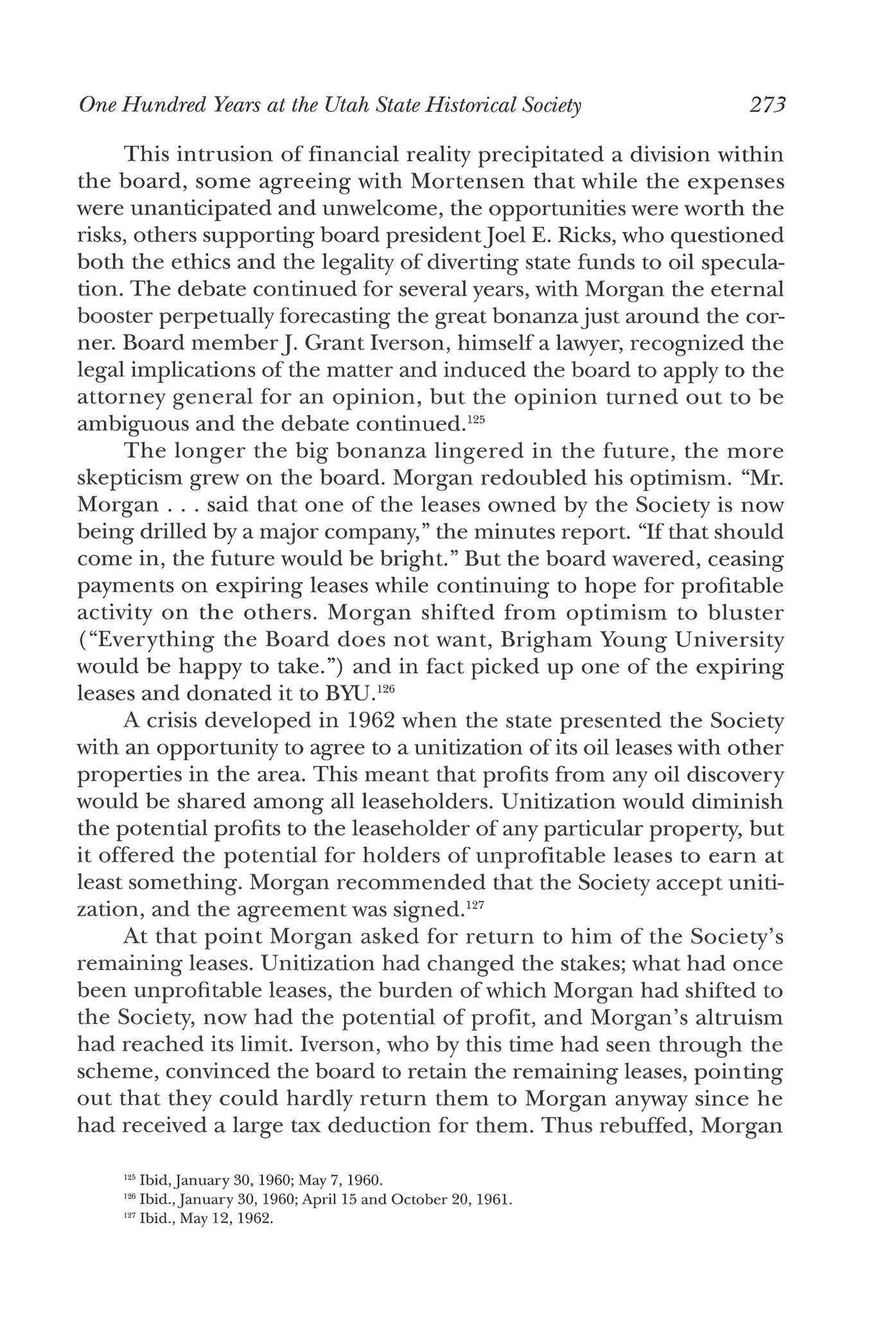

Hall of Relics. Pioneer artifacts in this building inspired thoughts of a historical museum.

change of views and criticisms" through scheduled meetings (anticipating the annual meetings, Statehood Day celebrations, and perhaps even the Publications Section). Little imagination is required to foresee the Historic Preservation Section developing as an extension into the historical period of the concern for aboriginal sites (though historically the Historic Preservation Section would slightly precede the Antiquities Section). And one can easily see the preservation, interpretation, and exhibition of museum artifacts contained within both the impulse to investigate Indian remains and the impulse to collect documentary sources. Finally, Letcher urged that "it is desired that every section of the state should be represented" both at the organizational meeting and in participation in the Society's activities In this he was to be disappointed, for the northern counties were almost the only ones represented, particularly Salt Lake County, which sent no less than sixteen delegates Cache, Davis, Weber, and Utah counties each sent two representatives, while one delegate from Carbon and one from Iron County were the sole representatives from the central and southern parts of the state.11 Over the years, the Society would continue the effort to make itself authentically a state organization through the formation of local chapters, holding annual meetings and Statehood Day celebrations outside the Wasatch Front, encouragement of local historic preservation efforts through the Certified Local Government program, and publication in the Utah Historical Quarterly of articles on all parts of the state. Governor Wells called the July 22 meeting to order, recognized the fact that the organization was the brainchild ofJerrold R Letcher, and appointed him chairman. Letcher's first act exhibited his political acumen: he invited Franklin D Richards to address the gathering

210 Utah Historical Quarterly

Governor Heber M. Wells opened the Society's organizational meeting.

11 Deseret Evening News,

21, 1897;

22, 1897,

July

Utah State Historical Society Minutes, July

Utah State Archives

and to give his approval to the new organization. Second in seniority only to Lorenzo Snow on the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Mormon church (when Snow succeeded to the presidency in 1898, Richards became president of the quorum and remained second in line to succession to the church presidency until his death in 1899), Richards was one of the most important figures in Mormondom. Furthermore, as church historian since 1889, he was the one person whose blessing on the Utah State Historical Society would indicate that the Mormon church saw neither competition nor conflict of interest inherent in the new organization. As we shall see, Richards even became its first president, thus holding at once the same position for both church and state In view of Letcher's well-known status as a non-Mormon, involving Richards at the beginning was an important step in avoiding an apparent church-state division as the new organization sought its place in Utah cultural life.12

Other speakers addressed the meeting, the most significant, perhaps, being Governor Wells, who urged the writing of a "true history of the state" with due consideration to its geological features and advocated the creation of "a reading-room and a library in connection with the association." Antoinette B. Kinney endorsed Wells's library proposal Hadley D Johnson addressed the meeting last Modern observers of the Society, well aware of the perennial struggle to raise both public and private funds to support its programs at even minimal levels, will recognize the voice of a prophet in Johnson's comments: "He was willing to do anything to help the movement except in the way of money and in a pinch might help with money. 'You will need money, too,' he said, 'for when the society is fully organized and under good headway we will need a good building for it.'"13

Two seven-member committees were appointed, one to draft a constitution and by-laws and the other to meet with the Jubilee Commission to try to gain custody of the artifacts collected and exhibited in the Hall of Relics. Obviously, if the Society was going to assume custody of a museum collection and begin assembling a library, the constitutional committee was going to have to provide a way for the

12 While the Deseret Evening News, July 23, 1897, reports the organizational meeting, the Salt Lake Tribune of the same date carries a fuller narrative of the proceedings than either the News or the official minutes of the Society. On Franklin D. Richards, see Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1901) vol. 1, pp. 115-21. Although Davis Bitton and Leonard

J. Arrington, Mormons and Their Historians (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988), give little detail on Franklin D Richards, their background information on the development of the Church Historian's Office is useful

13 Salt Lake Tribune, July 23, 1897

Hundred Years at the Utah State

211

One

Historical Society

Archaeology intrigued the Society's founders, but activity in that field was decades away. Antiquities Section excavation at White Mesa ca. 1979.

organization to acquire some kind of permanent and legal status as well as funding for a permanent staff and physical facilities. A second meeting was scheduled for December 28 in the director's room of the Deseret National Bank to examine the progress of each committee. The resulting articles of incorporation and by-laws gave a fairly clear indication of the direction the new organization intended to take. The statement of purpose, for one thing, was significantly expanded from earlier versions. At the head of the list was the previously stated goal of investigating prehistoric sites, followed by a reiteration of the intention to create a museum and library. The latter goal was now augmented, though, by specific mention of a desire to collect "especially narratives of the adventures of early explorers and pioneers." Finally, the Society was directed vaguely to promote "the cultivation of science, literature and the liberal arts" and to hold regular meetings toward those ends.14

Gaining membership in the Society, unlike today, when one is asked only for a name, address, and annual fee, was no idle matter. Active membership was available to "any person of good moral character who is interested in the work of this society." Each application had to be "endorsed by not less than three active members in good standing" and accompanied by an initial membership fee of two dollars and another two dollars annual fee. Having passed those hurdles,

212 Utah Historical Quarterly

14 Deseret Evening News,

December 29, 1897

the application went before the Board of Control, where it was required to receive a majority vote.15

The lists of incorporators and charter members (there were separate lists, curiously, containing approximately but not precisely the same names) included, as did the signers of the "Historical Society Call," a wide sampling of Utah's most prominent citizens. Among the initial officers was Franklin D. Richards as president. Although he was seventy-six years old and in fact would die almost exactly two years later, he was, in view of his status in the Mormon church and his role as church historian, noted above, a diplomatic choice. Furthermore, while most of the routine business of the Society was apparently carried out by the energetic Jerrold Letcher in his role as recording secretary, Richards was no mere figurehead. At the two annual meetings over which he presided, he gave a presidential address.16

In addition to Richards and Letcher, the officers included Isabel Cameron-Brown as vice-president, James T. Hammond as corresponding secretary, Lewis S. Hills as treasurer, and Antoinette Brown Kinney as librarian. Kinney, an 1887 graduate of the University of Michigan and wife of Salt Lake City attorney and fellow charter member of the Society, Clesson S. Kinney, was paying for her vocal endorsement of Governor Wells's suggestion that the Society should have a library by being appointed its first librarian—a librarian without books. Among the members of the first Executive Committee (or Board of Control) were Henry W. Lawrence, a businessman, former Godbeite, and Populist gubernatorial candidate; Judge Charles C. Goodwin; Joseph T. Kingsbury, president of the University of Utah; and John T Caine, actor, editor, and former delegate to Congress.

The Society planned an active program. Besides an annual general meeting of the Society on the third Monday ofJanuary, the Board of Control was to meet four times a year, in January, April, July, and October. Finally, a "field day" was to be held each summer.

THE FIRST ANNUAL MEETING

The Society's earliest annual meetings were lively affairs featuring both music and intellectual stimulation. The first one took place

15 Ibid Life membership was available to anyone offering good moral character, three endorsements, and fifty dollars; corresponding membership could be acquired by out-of-state residents of "literary and historical attainments" (no examination specified), and honorary membership was for "explorers and Pioneers, or persons distinguished for literary or scientific work, particularly in the line of American history, who are non-residents of the State."

16 Ibid.; USHS Board Minutes, December 28, 1897-January 16, 1899.

213

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society

in the Theosophical Hall on West Temple on the evening of January 17, 1898, less than three weeks after the Society's organizational meeting There is reason to doubt the Deseret News report of the meeting which says it began with the election of officers, for the officers had already been chosen at the December 28 meeting, though they may have been installed or confirmed in some way. 17 It is likely that the meeting launched right into the musical entertainment, a vocal solo by Miss Nellie Holliday called "Rest Unto the Weary." The musical component of the annual meeting remained a common, though not indispensable, feature of the meetings until the retirement of Marguerite Sinclair in 1949. The address of President Richards that followed may not have been, as the News reported, "the chief event of the evening," but he clearly took hisjob seriously and put some effort into sketching his vision for the future of Utah historical work. He began by commending the Society's intention to preserve the artifacts collected during the Jubilee as the nucleus of a history museum and then went on to list the themes that he thought Utah historians should make the focal points of their research. Among those were irrigation, agriculture, the extractive industries, transportation, and social and political development. Dominating his recommendations, though, were cultural affairs—literature, architecture, fine arts, and religion The modern reader can hardly fail to be struck by the fact that, in view of the recent celebration of the pioneer era, Richards made only one mention of that and devoted the rest of his address to themes that still engage Utah historians a century later

The other two addresses were given by prominent cultural figures in turn-of-the-century Utah. Dr. Ellen Brooke Ferguson, one of the

214 Utah Historical Quarterly

Franklin D. Richards, first president of the Utah State Historical Society, was also the IDS church historian.

17 Deseret Evening News, January 18, 1898 The Board Minutes give a less elaborate report, with only the titles of the addresses

founders of the Society and surely one of the most energetic and accomplished members in its history, spoke on "The True Mission of History."18 The daughter of a prominent lawyer in Cambridge, England, she was taught from an early age by Cambridge University tutors from whom she acquired a much better education than was available in the women's seminaries to which females were often banished in that day In 1857 she married Dr. William Ferguson and began her own study of medicine, finishing her program in the United States, to which they immigrated in 1860. In this country she ran a newspaper, practiced medicine, and traveled about the East lecturing on woman suffrage. She returned from a brief visit to England in 1876 to find her husband preparing to move to Utah in response to his recent conversion to Mormonism In Utah she divided her time among medicine, woman suffrage, and Democratic politics. Widowed in 1880, she poured her energy single-mindedly into various civic causes. She was one of the founders of the Utah Conservatory of Music in 1878, the Deseret Hospital in 1882, and the Woman's Democratic Club in 1896. At some point in the late 1890s her commitment to Mormonism waned, and she left that church and became involved in Theosophy, a spiritualist religion founded in the United States in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky that was enjoying considerable popularity. It was obviously through Dr. Ferguson's agency that the Society met in the Theosophical Hall Not long after this meeting she moved to New York.19

The final address, on "The Utah Pioneers," was given by Joseph T. Kingsbury, president of the University of Utah. A native of Weber County, he grew up with the University of Utah (while it was still the University of Deseret) as a student, chemistry professor, and president. A poor farm boy, he worked his way off the farm through academic excellence. After studying at the University of Deseret, which was then little more than a high school, he attended Cornell and Wesleyan universities, taking the Ph.D. in chemistry from the latter institution. Returning to Utah as professor of chemistry, Kingsbury was instrumental in transforming the school into the University of Utah (the name changed in 1892), a credible institution of higher learning with the beginnings of the campus on its present site.20

18 Th e Deseret Evening News gives, the title as "The Proper Field for the Historian."

19 Orson F Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q Cannon & Sons, 1904), vol 4, pp 602-4

20 Ibid., pp 355-57; Ralph Vary Chamberlin, The University of Utah: A History of Its First Hundred Years, 1850 to 1950 (SaltLake City: University of Utah Press, 1960), pp 212, 340 See also Craig H Bower, "Academic Freedom and the Utah Controversy, 1911 and 1915" (honors thesis, University of Utah, 1995)

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 215

The DeseretEvening News reported none of Ferguson's address but gave a brief sketch of Kingsbury's remarks, which appear not to have been profound. After outlining the history of the pioneer period and describing the natural resources of the state, he went on to forecast an important role for the Historical Society in the "collection of proper and accurate data for the future historian."21

The first annual meeting set the direction for the Society for years to come. One healthy precedent was inclusion of avocational historians as speakers, for later history would demonstrate the strength imparted to the Society by local and family historians and history buffs. Some of Utah's best history has been written by the likes of Leonard J. Arrington, Dale L. Morgan, Juanita Brooks, Charles Kelly, Helen Z. Papanikolas, and Wallace Stegner—all of them lacking academic degrees in history. Another precedent was to involve Utah's most prestigious citizens, who made Historical Society membership something to be desired and respected. In a relatively poor state with a strongly pragmatic tradition, where cultural agencies have to compete for funding with prisons, roads, and other urgent matters, involving the wealthy, the prestigious, and the powerful can help give those agencies the competitive edge they need

Nevertheless, one thing was lacking among the founders of the Society: professionalism. In spite of his position as LDS church historian, Franklin D. Richards was not an academically trained historian, and he was the only one of the founders who had any claim to professionalism, if only through his employment. It is true, of course, that the modern historical profession was only beginning to emerge at that time, as young American scholars began going to Germany to undertake seminar-based Ph.D programs, so it is scarcely remarkable that Utah as yet would have few, if any, of them.

That lack of a pool of professionals notwithstanding, the second annual meeting, held on January 16, 1899, made a significant step forward in the quality of two of the four addresses given. One was byJames E. Talmage, at that time director of the Deseret Museum, on the topic "The Materials of History." The burden of his remarks was that the state's material heritage must be protected from vandalism which had destroyed "many important relics of bygone ages."22 No doubt his cornNamed president of the university in April 1897, Kingsbury resigned in disgrace in 1916 after the new American Association of University Professors found him guilty of preferring Mormons in faculty recruitment and promotion

21 Deseret Evening News, January 18, 1898.

22 Ibid., January 17, 1899 The full text of the addresses is given in ibid., January 28, 1899

216 Utah Historical Quarterly

ments were prompted by the indiscriminate plundering of prehistoric sites just beginning at the time as well as the heightened interest in material culture prompted by the Hall of Relics exhibition during the Jubilee. Proper curation of the latter artifacts would remain a concern of his and although the museology profession was at that time as embryonic as the historical profession, he rendered the state a significant service.

The other address, "The Prehistoric Races of the Southwest," was given by the inimitable Don Maguire, one of the most remarkable characters in Utah history.23 He was born into a family of Irish immigrant peddlers in St.Johnsbury, Vermont, in 1852. When the family followed the transcontinental railroad to Utah in 1870, Maguire began learning the family trade from his father and brothers Peddling led him on several remarkable journeys from his home in Ogden to North Africa, to the gold fields of Idaho and Montana, and, most significant, to Nevada, California, Arizona, and even Mexico, the latter three, especially, bringing him considerable money. Much more than just an adventurer and businessman, though, Maguire was a student who kept detailed notes on the geography, economy, and society of the places he visited. One of his greatest passions was prehistoric Indian cultures. His notes on his Arizona expeditions contain elaborate descriptions of Indian ruins—famous ones like Casa Grande and obscure ones like a later-destroyed castle near Prescott where he and his men camped while awaiting the business that payday at Camp Verde would bring. Upon his retirement from peddling in 1879, Maguire devoted much of his time to mining exploration and

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 217

Artifacts in the Hall of Relics shown here include oldfort door and tools, rifles, and musical instruments.

23 In addition to the Don Maguire Papers at the Utah State Historical Society, see Gary Topping, ed., Gila Monsters and Red-eyed Rattlesnakes: Don Maguire's Arizona Trading Expeditions, 1876-79 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1997)

speculation and to excavating prehistoric sites. Perhaps his most famous excavation was the ruins near Paragonah, Utah, the site from which the evidence for his Historical Society address was derived.24 Beginning with a general account of the prehistoric sites observed during his southwestern expeditions, he then offered a survey of the economy, architecture, weapons, and burial practices of the Paragonah Indians.

If museology and history were in their professional infancies, so too was archaeology, and Maguire's excavation techniques and interpretations would no more stand up to modern professional standards than would those of Richards or Talmage in their fields Excavation to Maguire was simply artifact recovery, with no attention paid to mapping, stratigraphy, or any of the other techniques of the modern archaeologist. Also, Maguire considered prehistoric American Indians to have been a single culture, so that generalizations based on one site would apply everywhere else Nevertheless, Talmage and Maguire were active scholars reporting current knowledge in their fields as ably as their limited training would allow, and their addresses represent a discernible progress toward the scholarly standards of the modern Historical Society.

Scientific documentation ofarchaeological sites and artifacts is the hallmark of Antiquities Section work as this 1980 photograph demonstrates.

Despite what appeared to be a promising beginning, the Society rather quickly passed into the doldrums. The third and fourth annual meetings again featured musical selections and addresses, but from then until the twenty-first annual meeting in 1918, the meetings with few exceptions consisted only of the election of officers in dutiful obedience to the by-laws, with no other business conducted. After the 1918, 1919, and 1920 annual meetings which featured addresses

218 Utah Historical Quarterly AS 42SA854 5 METATE IN SITU P 3 VIEW S 4 7 8 0 ROLL 3 E 5

24 Don Maguire, "The Paragoonah Fortress," Salt Lake Tribune, January 30, 1893; Neil M Judd, Archaeological Observations North of the Rio Colorado. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 82 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1926), 54 indicates that Maguire did his work at that site in January, 1893 Something of the growth in sophistication in archaeology is indicated in the fact that Judd, who worked at the site in 1916, refers to Maguire's work as "mutilation."

(though only the 1918 meeting included music), the tradition was completely abandoned except for the perfunctory elections, until 1930. Two more annual meetings with addresses followed, and then the Lecture Committee on October 3, 1931, announced formal suspension of the public sessions for fear of competing with other organizations that were holding similar meetings.

The Society's hard times following World War I are graphically symbolized by the board minutes themselves. Handsomely typewritten on ledger sheets during Jerrold Letcher's tenure as recording secretary, they rapidly declined in both content and appearance. When Letcher resigned in 1920 to fill a state position called referee of bankruptcy,25 his successors sometimes penciled their minutes on odd chunks of scratch paper, and in three instances merely on 3-by-5 index cards. There was little business to record, and from 1925 to 1927 minutes are completely lacking. Evidently, the empty exercise of electing officers with nothing to do had finally lost whatever appeal it had once exerted

This is certainly not to say that the Society was completely inactive during those years around World War I, for in fact some fundamentally important developments occurred at that time. For one thing, the Society achieved the status of a state agency in 1917 and received its first state appropriation in that year—two hundred dollars to care for the artifacts from the Hall of Relics.26 It is hard to overestimate the importance of that achievement Founded by an elite group of Utahns in the momentary rush of enthusiasm for the Pioneer Jubilee, the Society had easily assumed responsibilities it could never have fulfilled had it remained an elite organization funded only by membership dues and donations. Becoming a state agency laid the groundwork for shifting the Society's base of support from a tiny group—wealthy and influential though they were—to the people of Utah themselves. It was the beginning of the democratization of the Society, and that democratic support has been the Society's greatest strength.

Another accomplishment of the Society during that somewhat fallow period was the acquisition of permanent quarters. It was obvious from the beginning that if the Society were to fulfill any part of its ambitious goals of assembling a library and manuscript collection and

25 Letcher continued to be active at meetings of the Society until his death in 1922 Deseret News, July 17, 1922.

26 State of Utah, Biennial Report of the State Historical Society of Utah, 1917-1918, in Utah Public Reports.

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 219

curation of the Hall of Relics artifacts and other material objects, some kind of office or museum space would be required. With both the governor and the secretary of state of Utah present on the Society's board, it was natural that the possibility of rooms in the future State Capitol, then under discussion, would be considered. In fact, the initial call to organize the Society expressed the intention of seeking space in the Capitol

Unfortunately for the Society, as for state government, that building was slow in coming. As a result of a contest among architects for the best design, Richard Kletting was given the commission, and ground was first broken in 1912. Completion of the building in 1915 marked the end of what Dale L Morgan calls "an orphaned existence" for state government and for the Historical Society as well.27 While that orphan status must have been difficult enough for the state legislature and courts, it was impossible for the Society to carry out much more than board meetings and public lectures without permanent quarters. Thus, even though the minutes laconically mention the Society's first meeting in its new room in the basement of the Capitol on January 17, 1916, the event must have been the occasion for considerable rejoicing. At last, cramped and isolated as its new quarters were, the Society could begin its full role as initially planned.28

One of its most neglected functions was the preservation and exhibition of the pioneer artifacts assembled during theJubilee. Much of that material had already passed out of the Society's custody. Lacking any facility in which even to store the artifacts properly, the Society had at first housed them in the City and County Building, but it responded positively to an offer from James E. Talmage on January 20, 1913, to place the most interesting of them on display in a special exhibit as part of the Deseret Museum in the Vermont Building on South Temple. 2 9 When combined with materials loaned by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) and certain privately owned artifacts, they made a large and impressive exhibit, requiring expansion of the museum onto a whole new floor of the building.30

In an attempt to realize its original goal of caring for historical artifacts, though, the Society retained some of the Jubilee material for

27 Utah Writers' Project, Utah: A Guide to the State (New York: Hastings House, 1941), p 246

28 USHS Board Minutes, January 17, 1916

29 Ibid., January 20, 1913 The minutes of December 12, 1924, indicate that the artifacts had first been stored in the City and County Building

30 Sterling B Talmage, "Relic Hall of the Deseret Museum," Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine* (1913): 137-42.

220 Utah Historical Quarterly

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society

exhibit in the Capitol. Innocent of security and preservation concerns, the Society apparently placed the artifacts in unprotected locations about the building. The consequences were easily predictable, and Jerrold Letcher complained on January 3, 1920, that the artifacts were being damaged by public handling. D. W. Parratt, the new secretary, recommended installation of protective screens at an estimated cost of $332. Although the Society continued to receive donations of historical artifacts, and in fact assumed the additional responsibility for the new Memorial House in Memory Grove, it was to be many more years before it acquired the facilities and professional expertise to care for and exhibit them properly Eventually responsibility for the Capitol exhibits passed to the DUP.31 Sadly, the central stated purpose behind creation of the Society—curation of pioneer artifacts—has to be reckoned among its greatest early failures

The Society's final project during the doldrum years of the 1920s was ultimately successful, though it reached that success via a rocky road World War I, the Great War, the bloodiest conflict in world history to that point, had traumatized Utahns as it had all civilized people. The ghastly carnage of the Marne, the Somme, and Verdun had called into question the most fundamental assumptions of western civilization: the belief in progress, the belief in democracy, the belief in science. Instead of creating a peaceful millennium of democracy and prosperity, the two great revolutions of the nineteenth cen-

31 Utah Writers' Project, Utah: A Guide to the State, pp 249-50, describes the Relic Hall exhibits of the DUP in the Capitol at the beginning of the 1940s In the "Report of the Utah State Historical Society, 1925-26," Utah Public Documents, president Albert F Philips reported that "the property of the society was gathered together and stored in room 131 in the capitol building, a number of relics which could not be stored in the room were placed in an enclosure in the basement of the building and still others which had been thrown into a junk pile resurrected and the Daughters of the [Utah] Pioneers placed them on exhibition with the relics which they have, for the better protection of them." An inventory of the collection is appended After construction of the DUP Museum in 1947 some of the artifacts found their way there, while others were placed on exhibit in the Information Services Building on Temple Square

221

The Society is still the custodian of The Book of the Pioneers, a unique two-volume compilation of pioneer reminiscences collected during the 1897Jubilee.

tury had converged to create the world's greatest catastrophe. As the industrial revolution produced the technology to kill immense numbers of people, the democratic revolution produced immense numbers of people willing to be killed.32

At the end of the war, Utah's war mobilization agency, the Council of Defense, turned over to the Utah State Historical Society a state-funded project to write a history of Utahns who had participated in that great conflict. Supported by a $5,000 appropriation, it was the Society's first great project, and it engaged University of Utah history professor Andrew Love Neff to write the book.33

The war history caused a bustle of activity at the Society's headquarters for the next three years For one thing, the legislative appropriation enabled the Society to hire its first salaried employees in the form of two secretaries—Misses Willajaskey and Marba Cannon—for a stipend of $100 per month (soon reduced to $75). Also, the Society's well-known newspaper clipping files were begun at this time, as the board engaged the Intermountain Press and Clipping Service to clip articles on Utah and the war. Unfortunately, this project was discontinued after a year. 34 Neff proved to be a mighty engine of research who produced a draft manuscript of some three hundred pages. 35 Ultimately, though, his interpretive powers proved unequal to his research energy, and he abandoned the project.

At the board meeting ofJanuary 16, 1922, Neff reported that the gathering of individual biographical information on Utah's veterans was becoming an expensive redundancy, for the federal government had offered to provide similar data at no cost More serious, the subject appeared so diffuse to him that he was unable to discover a central theme or themes around which an integrated narrative could be organized: "The writing of a military history had proved impracticable because of the geographical distribution of the men and the lack of unity in the kinds of service rendered by them." Therefore Neff proposed to abandon the comprehensive history in favor of a "series of historical monographs" on smaller topics focusing on "the internal history of the state during the war, stressing the organization of the state for war purposes and evaluating the extent and character of the

32 The author is indebted to Professor Ronald Smelser of the University of Utah for this concise summary of the significance of World War I

33 USHS Board Minutes, March 25, 1919.

34 Ibid., May 20, 1919; June 3, 1920.

35 Andrew Love Neff Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

222 Utah Historical Quarterly

service performed by the citizens and industries of this commonwealth."

This contraction of the original plan might have seemed necessary to Neff, but the protracted discussion of the subject over the next year's board meetings seems to indicate that the board was reluctant to abandon the larger enterprise There was certainly no ambiguity on the part of the Council of Defense which, when it received the news of Neff's proposal, elected to remove the project from his hands At the meeting of October 29, 1923, the board considered a request from the governor, prompted by the council, that all source material assembled by Neff be turned over to Noble Warrum, a representative of the council, for preparation of a comprehensive history along the lines of the original plan. Although a committee consisting of Neff, Levi Edgar Young, and D W Parratt was appointed to meet with the governor concerning what they called "this strange request," the council's wishes prevailed, and the history was finished by Warrum under the title Utah in the World War.56 And so the Society's first great publishing project came to a close. Neff's massive, though uncompleted and unpublished, manuscript still resides at the Society At least he had worked cheaply: the board minutes of January 19, 1920, report that at that point, of the $5,000 appropriation, the only expenditures had been for the clipping service and secretarial salaries, a total of $660.69

THE FOUNDING OF UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

No one reading through the minutes of the board of the Utah State Historical Society during the 1920s can fail to be impressed by the radical improvement simply in their physical appearance begin-

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 223

Noble Warrum completed the Society's first book-publishing project. Frontispiece from another work of his, Utah Since Statehood.

Noble Warrum, Utah in the World War (Salt Lake City: Arrow Press, 1924).

ning on April 6, 1927. Instead of being scrawled in pencil on torn scraps of paper and so laconic that an entire meeting could be recorded on a 3-by-5 card, suddenly the minutes are neatly typewritten on small three-hole binder sheets and fully as elaborate in content as those kept byJerrold Letcher. Clearly something radical had happened.

That something radical was J. Cecil Alter, and for the next two decades his industrious efforts would begin the transformation of the Society into a vigorous organization with authentic scholarly standards fulfilling a vitally important function in Utah cultural life. Encouraged by the businessman-scholar Herbert S. Auerbach, aided by the tireless secretary-manager Marguerite L. Sinclair, and supported by the remarkable self-made historian Dale L. Morgan, Alter started the Utah Historical Quarterly, began assembling a serious Utah history library, and secured the first regular appropriation from the state legislature The modern Historical Society had begun to emerge.

Given Alter's obsessive enthusiasm for Utah history, it is ironic that he was neither a native Utahn nor an academically trained historian.37 Born on a farm near Rensselaer, Indiana, in 1879, Alter evidently acquired his breadth of curiosity from hisjack-of-all-trades father who had pursued a variety of occupations. After attending several midwestern colleges, he settled upon meteorology as a career and went to work for the U.S. Weather Bureau in 1902. He excelled at his profession and invented an effective precipitation gauge and a system for surveying mountain snow When the bureau assigned him to Salt Lake City in 1904, Alter found a bride,Jennie O. Greene, and a new environment into which he threw himself with unbridled eagerness. Not content merely to study and record the weather, he served his adopted state as chairman of the Utah State Parks Commission, as a member of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, and as author of travelogs and historical columns in two Salt Lake newspapers.

Alter's interest in Utah history became so consuming that he rejected several opportunities to advance in his own profession that would have required leaving Utah. Instead, he filled his free time by writing a succession of books on his adopted state, including a biography of Jim Bridger, the three-volume Utah: The Storied Domain, and especially Early Utah Journalism. While others, particularly Dale Morgan, could find fault with some of Alter's research, his writings sig-

37

224 Utah Historical Quarterly

Most of the biographical material that follows is based on Miriam B Murphy, 'J Cecil Alter, Founding Editor of Utah Historical Quarterly," Utah Historical Quarterly 46 (Winter 1978): 37-44

nificantly advanced our understanding of Utah history.38

Perhaps Alter's greatest contribution to Utah and the Historical Society was the creation of the Utah Historical Quarterly and nursing it through the disastrously lean times of the Great Depression. Forced to suspend its publication during 1933-39, he kept the magazine alive as an idea, at least, by publishing a series of historical monographs in its place and then resuscitating it when sales of earlier bound volumes and of Early Utah Journalism had brought in the needed funds.

Publishing had been implied as far back as the original statement of the Society's goals, but specific plans were not advanced until 1920 when Andrew Jenson announced the intention to start a quarterly historical magazine the following year. He planned to use the magazine to publish original documents and to that end had secured permission to publish portions of Wilford Woodruff's diary It was a farsighted plan, but the legislature denied the necessary funds.

By 1927 the legislature was evidently in a more generous mood, for it voted an annual salary of $1,200 to be split between Alter, as secretary-treasurer of the Society and editor of the Quarterly, and Albert F Philips, as librarian and curator of the museum. Although Alter's mounting responsibilities led to a raise in 1931 of $100 per month, that sum was, in the estimation of Alter's biographer, "more like an allowance since it was expected to cover expenses 'not provided for in appropriations for properly conducting the Society's business.'"39 Eventually, though, his salary was cut to $30 per month in 1933 as the depression tightened its grip on Utah. Luckily, Alter had more reliable and substantial sources of income.

One Hundred Years at the Utah State Historical Society 225

J. Cecil Alter, weatherman and founding editor o/"Utah Historical Quarterly.

38 Writing to Marguerite Sinclair, Morgan acknowledged that he "always had the greatest admiration for his [Alter's] promotional efforts in behalf of the Historical Society, though often I don't see eye to eye with him as a scholar and historian." Morgan to Sinclair, April 15, 1943, Dale Morgan Papers, Utah State Historical Society

39 Murphy, "J Cecil Alter," 41

The stipend was enough, nevertheless, to begin publishing the Utah Historical Quarterly. Following up on Jenson's original concept, the board members concurred that "the Quarterly should be made up largely ofjournals or diaries already available, at least prospective and not otherwise available in print."40 In fact, the early issues of the Quarterly contained a fair sprinkling of interpretive articles as well as original sources. Articles on Indians and military subjects were most prominent in the first six volumes, but there was a fair showing of other topics as well. Board members, according to Miriam Murphy's calculations, contributed 18 percent of the articles

Despite this promising start, the Great Depression had so constricted state revenues by 1933 that the legislature was forced to cut the Society's budget deeply enough to kill the young Quarterly and greatly reduce Alter's stipend. It was the Society's greatest crisis to that point, and something of the desperation of the board is conveyed in the language of the minutes for April 8, 1933. At the same time it announced suspension of the Quarterly and Alter's salary cut, it moved that "the fate of the Quarterly be left to the Editor, Secretary-Treasurer [Alter], and that he be given 'Dictatorial' powers to do as he found possible and practicable, with the assurance such action would be approved by the Board. This motion was passed unanimously without discussion." Dictator Alter, indeed! One may reasonably doubt that he felt much kinship with Caesar or Napoleon! The grandiose term seems only to have meant that the board was suspending its regular meetings in the interest of economy and turning policy decisions as well as routine operations entirely over to Alter.

The Quarterly may have been dead, but its ghost haunted the office of the Society During its infrequent meetings over the next few years, the board expressed regret over its loss and "hopes for a rising tide in the Society's affairs very soon." Eventually those hopes bore fruit. Although its intention to replace the Quarterly with annual monographs had not come to pass, one such monograph, Alter's Early UtahJournalism, finally came off the press in 1938. The book sold well, its revenues nicely augmenting sales of bound copies of volumes 1-6 of the Quarterly. Finally, in 1939, the legislature was able to appropriate $5,000 for the next biennium, and the Quarterly was resurrected.41

Although Alter had passed over earlier opportunities to advance in the Weather Bureau because they would take him away from Utah, he

40 Board Minutes, April 6, 1927

41 Board Minutes, April 7, 1934; April 8, 1939

226 Utah Historical Quarterly

accepted a position in Cincinnati in 1941. Perhaps he felt he had accomplished most of what hewanted to do in Utah and, as we shall see, he certainly realized he was leaving the Quarterly in astrong position and the Society in good hands Even then, he could not really bring himself to leave the Society Alter continued as official editor ofthe Quarterly until 1945 but with greatly diminished effectiveness. For one thing, he was distracted by a divorce (the charge, understandably, inview ofhis multitudinous involvements with civic activities and organizations, was neglect) and remarriage to one of his assistants atthe Weather Bureau More important, it simply did not make sense to try to dothe job at a distance. As Dale Morgan complained, "the Board should get down to brass tacks and appoint anew editor of the Quarterly who can work at the job. I think itis absurd to continue any longer the policy of having Alter 'edit' the Quarterly at long range. The necessary work cannot be done except in the offices of the Society, and ifAlter is not coming back to Utah pretty soon, some other arrangement should be made."42 Alter's last contribution tothe Society was to augment the library. The board minutes of April 2, 1938, note that he had offered about thirty books plus a run ofthe Salt Lake Chronicle to form the nucleus of a reference collection. On October 8 the list was extended to a total of seventy-eight volumes. Never awealthy man, Alter was forced to sell the books to the Society AsJohn James remembered, Alter's offers continued well into the 1950s. "His letters were always delightful," James recalled, "and he always apologized for selling us the books, but he said he had to. He was retired and needed the money. He always gave us very good prices, and within the limits of our budget we were able tobuy quite afew of them."43

One Hundred Years atthe Utah State Historical Society 227 ItahHistoricaltuarterty JANUARY APRIL 1941 Hit Site of fort fipbidoux 6tt Trails, <Md forts, #ld Trappers and Traders Iscaiante's Map and Boutc Published in January, April July and.October, by tho Board of Control UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Stale Capitol SALT LAKE CITY UTAH Reprinted April 194)

Utah Historical Quarterly (JanuaryApril 1941) reflects interests of board members in trapper era and Father Escalante.

42 Marguerite L Sinclair to Dale Morgan, March 25 and July 12, 1943; Morgan to Sinclair, August 14, 1946 Dale L Morgan Papers, Utah State Historical Society 4, John James, Jr., interview with Eric Redd, August 9, 1972

Alter was fortunate in attracting some equally energetic co-workers, and much of what the Society accomplished during that time was a collaborative effort. Herbert S. Auerbach, for example, was president of the Board of Control (later called the Board of Trustees) from 1936 until his death in 1945, bringing wealth, energy, and a passion for western history, particularly the fur trade and the Dominguez-Escalante expedition. As an heir to the Auerbach's department store fortune, Herbert spent his money wisely on education, travel, and assembling one of the legendary collections of western books Born in Salt Lake City, Auerbach was educated in Germany and became an accomplished violinist who gave concerts in Europe. His graduate training at Columbia University School of Mines earned him a master's degree in electrometallurgy in 1906. He worked for several years as a mining engineer, but returned to Salt Lake City where he assumed an increasing role in the family business after 1911. A life-long bachelor, Auerbach lived in the Brooks Arcade and designed and built the popular Centre Theater across State Street from his living quarters.44

As Miriam B. Murphy has observed, "Auerbach seemed obsessed by Escalante."45 After publishing several articles on various aspects of the Franciscan Father, Auerbach and Alter worked together in presenting a translation of the Escalante journal as volume 11 (1943) of the Quarterly. Auerbach had located a copy of the journal at the Newberry Library, but that institution had already given permission to publish it to the great Latin American historian Herbert E. Bolton of the University of California, Berkeley. Undaunted, Auerbach found another copy in Mexico City and proceeded to prepare it for publication with Alter as his editor.46

41 J Cecil Alter, "In Memoriam: Herbert S Auerbach, 1882-1945," Utah Historical Quarterly 13 (1945):v-viii

45 Murphy, 'J Cecil Alter," p 43

46 Ibid., pp 42-43 Not everyone was impressed with Auerbach's scholarship Dale Morgan called

228

Historical Quarterly

Utah

Herbert S. Auerbach, department store heir, Society board president, and Escalante aficionado.

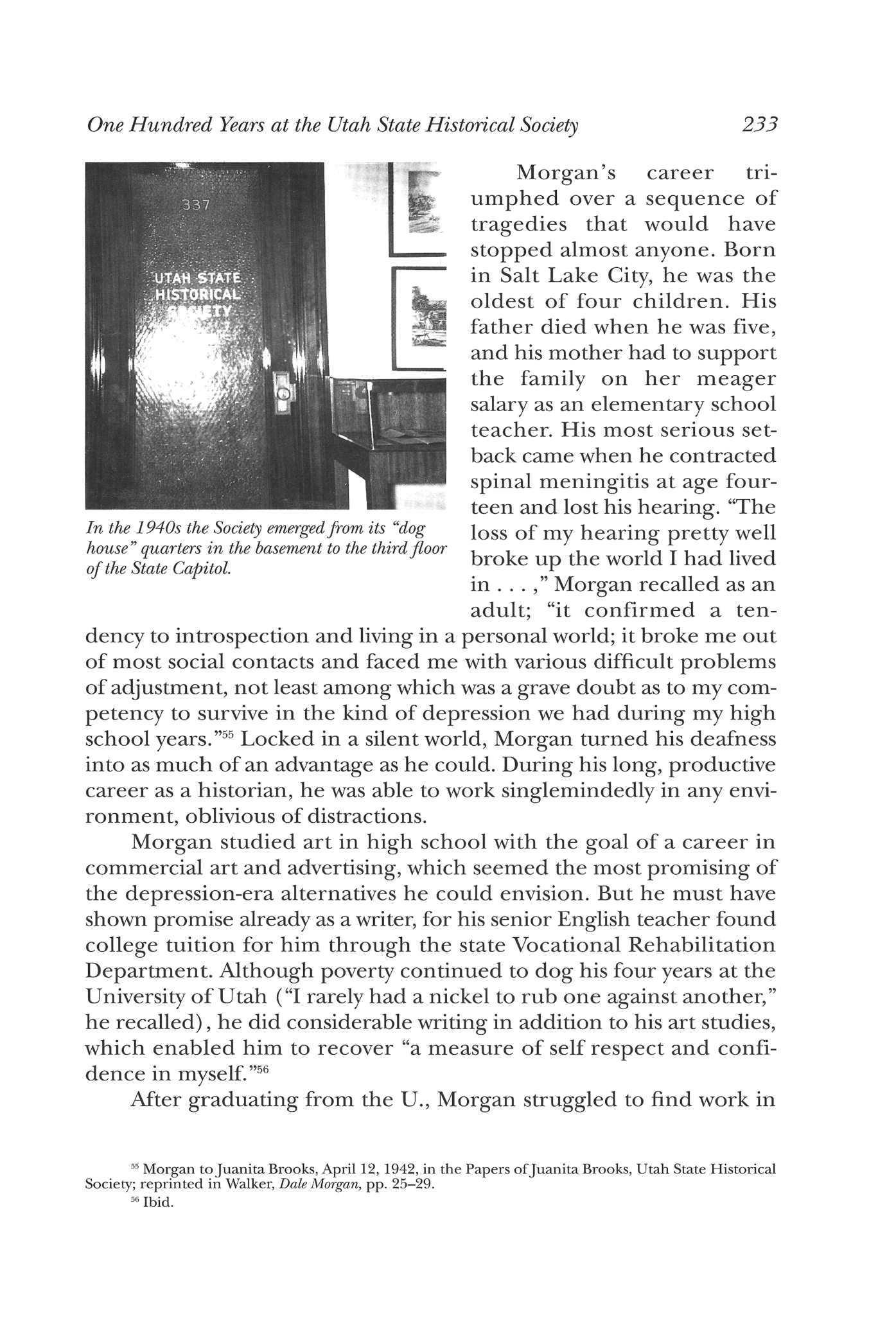

Auerbach's most controversial involvement with the Society concerned his immense library of western books on which he had lavished a large fortune. During his tenure on the Board of Control, he evidently allowed it to be understood that the Society would inherit his library upon his death, for in fact he had taken advantage of his status as president of the board to acquire some bibliographic rarities.47 It was not to be, for Auerbach left no will, and his sisters decided instead to have the collection catalogued by Brigham \foung University bibliophile Wilford Poulson and sold at auction. It was an immense blow to the Society, whose limited funds would not allow purchase of even a significant portion of the collection when forced to compete with the large acquisition budgets of the major libraries that would be bidding Matters were even worse than that, asJohn James, Jr., who became the Society's librarian in 1952, recalled, for anticipation of the Auerbach donation had significantly retarded the Society's book purchases, and James then had to start an acquisition program that was already seriously behind.48