H W co CO CO \ W <r \ z

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN S. ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

AUDREY M. GODFREY, Logan, 2000

LEE ANN KREUTZER, Torrey, 2000

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2001

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Murray, 2000

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

RICHARD C ROBERTS, Ogden,2001

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 1999

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1999

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 2001

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801)533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly Nezvsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on VA inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor. Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

^o<

UTAH STATE j HISTORICAL] SOCIET Y

THE COVER On September 1, 1936, PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt was in Utahfor thefuneral of his Secretary of War, former Utah governor George Dern. He is shown here on that occasion with Eleanor Roosevelt and Governor Henry Blood, a Democrat who, like Roosevelt himself was upfor re-election that year.

© Copyright 1999 Utah State Historical Society

HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y Contents WINTER 1999 \ VOLUME 67 \ NUMBER 1 IN THIS ISSUE 3 MORMONS AND THE NEW DEAL: THE 1936 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN UTAH BRIAN Q. CANNON 4 "BEEN GRAZED ALMOST TO EXTINCTION": THE ENVIRONMENT, HUMAN ACTION, AND UTAH FLOODING, 1900-1940 ANDREW M. HONKER 23 "THE MURDEROUS PAIN OF LIVING": THOUGHTS ON THE DEATH OF EVERETT RUESS GARYJAMES BERGERA 48 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING: THE SANJUAN RIVER GOLD RUSH, 1892-93 ROBERT S. MCPHERSON and RICHARD KITCHEN 68 BOOKREVIEWS 88 BOOKNOTICES 95 LETTERS 96

JUDY DYKMAN and COLLEEN WHITLEY

The Silver Queen: Her Royal Highness Suzanne Bransford Emery Holmes Delitch Engalitcheff, 18591942 ANN CHAMBERS NOBLE

88

MICHAEL F ANDERSON Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region BART ANDERSON 89

ANTON PAUL SOHN A Saw, Pocket Instruments, and Two Ounces of Whiskey: Frontier Military Medicine in the Great Basin . . . .EDWARD J. DAVTES II 90

DAVID R MACIEL and MARIA HERRARASOBEK Culture across Borders: Mexican Immigration and Popular Culture . . .DAVID CLARK KNOWLTON 92

RONALD M. JAMES and C. ELIZABETH RAYMOND Comstock Women: The Making of a Mining Community . . . .NANCYJ. TANIGUCHI 93

Books reviewed

In this issue

During the first century of statehood, Utahns have proven themselves notably mainstream in electoral politics. In twenty-six presidential elections, the Beehive State has lined up behind the winner no less than twenty times And in die eleven presidential elections from 1916 through 1956, the state pattern matched the national pattern perfectly. With considerable justification, the late Richard Poll could argue in the mid-1980s that "any disposition [of Utahns] to emphasize differences has long since given way to a desire to be the most American of all." Never was this generalization more conspicuously applicable than in 1936 as Utah joined forty-five other states in supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt's bid for a second term Yet, in at least on respect, this was an apparent anomaly: the typical Utah voter had to ignore the wishes of LDS church leadership to vote for FDR The dynamics of that interesting occurrence are analyzed and detailed in our first article.

The New Deal years are also at the heart of the second selection. Here the management of the public lands is put under the historian's glass in order to assess the cause and impact of floods in northern Utah during the 1920s and 30s. Once again, certain features suggest the Utah experience was typical of a much larger pattern, while other features are distinctly atypical. Equally interesting are the implications that this analysis holds for future planning as the state's growth rates continue to soar.

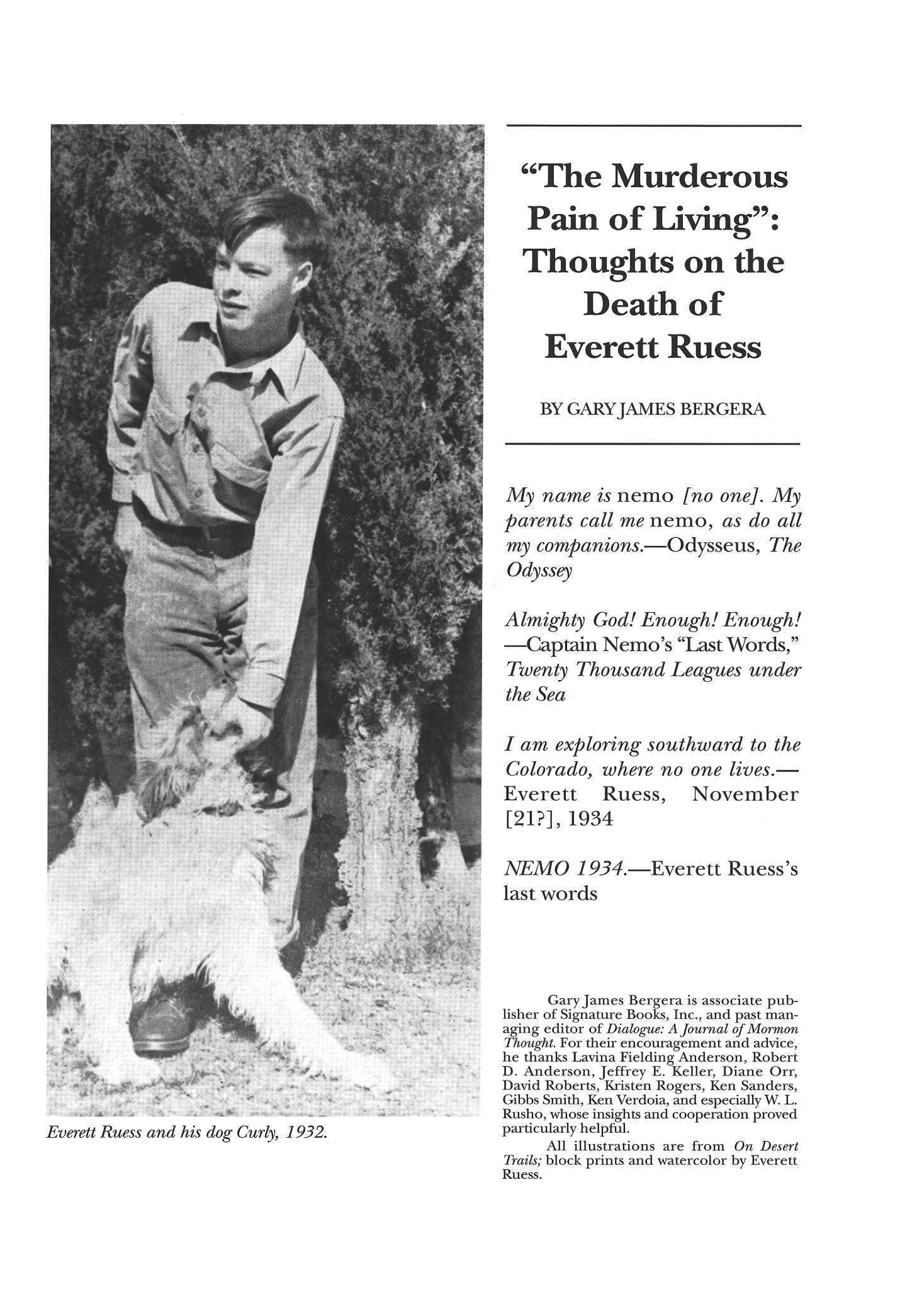

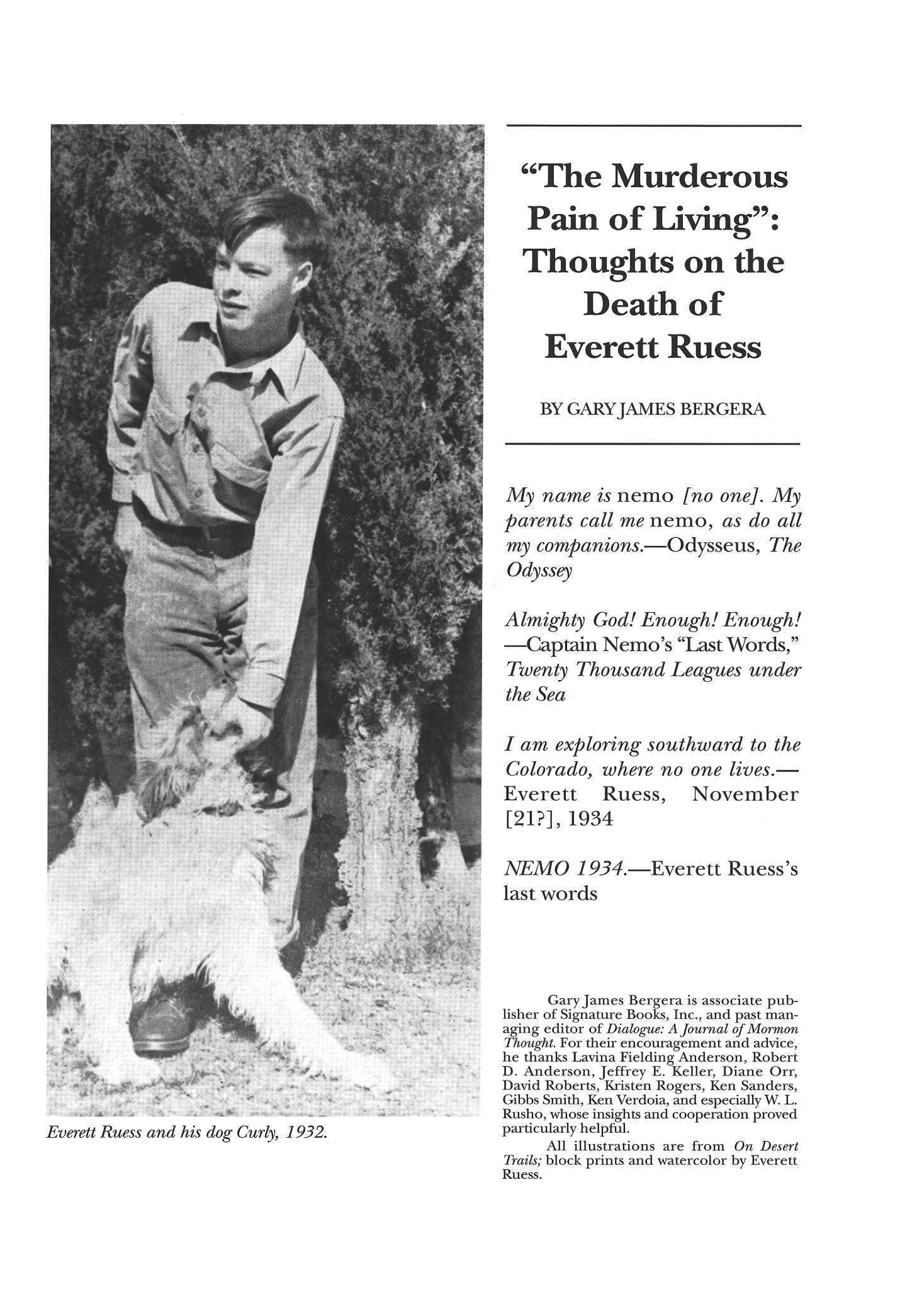

We then join in a historian-as-detective scenario as the next article seeks to resolve the riddle of Everett Ruess. A precocious, sensitive young poet and introvert, Everett simply vanished in 1934 during one of his solitary journeys into the beautiful wilds of southern Utah. The only clues he left behind are cryptic clips from his poetry and other musings, teasing and tormenting historians for decades. New and plausible hypotheses, of the type advanced here, are always welcome.

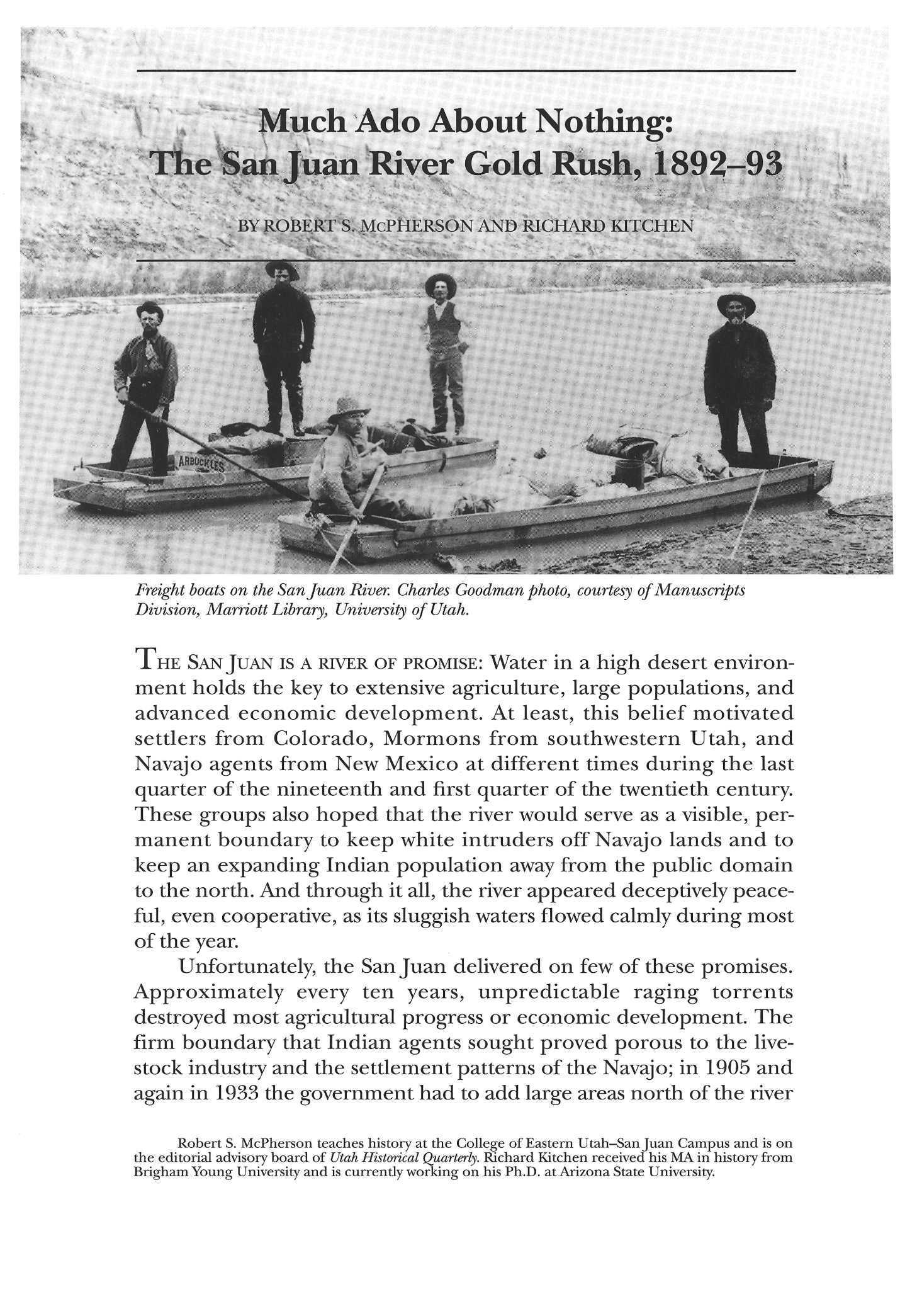

While young Ruess explored canyon country to find his soul, hundreds of other men preceded him by a full generation in quest of something equally elusive: gold from the San Juan. Doomed to personal disappointment by geological imperatives, these argonauts soon grumbled their way back home. Only the historical record was enriched, and that little treasure is generously shared in our concluding selection.

funiper tree, block print by Everett Ruess. From On Desert Trails (El Centro, CA: Desert Magazine Press, 1940).

Mormons and the New Deal: The 1936 Presidential Election in Utah

BYBRIAN Q. CANNON

BYBRIAN Q. CANNON

KE$ GOOD :ME 9 fo

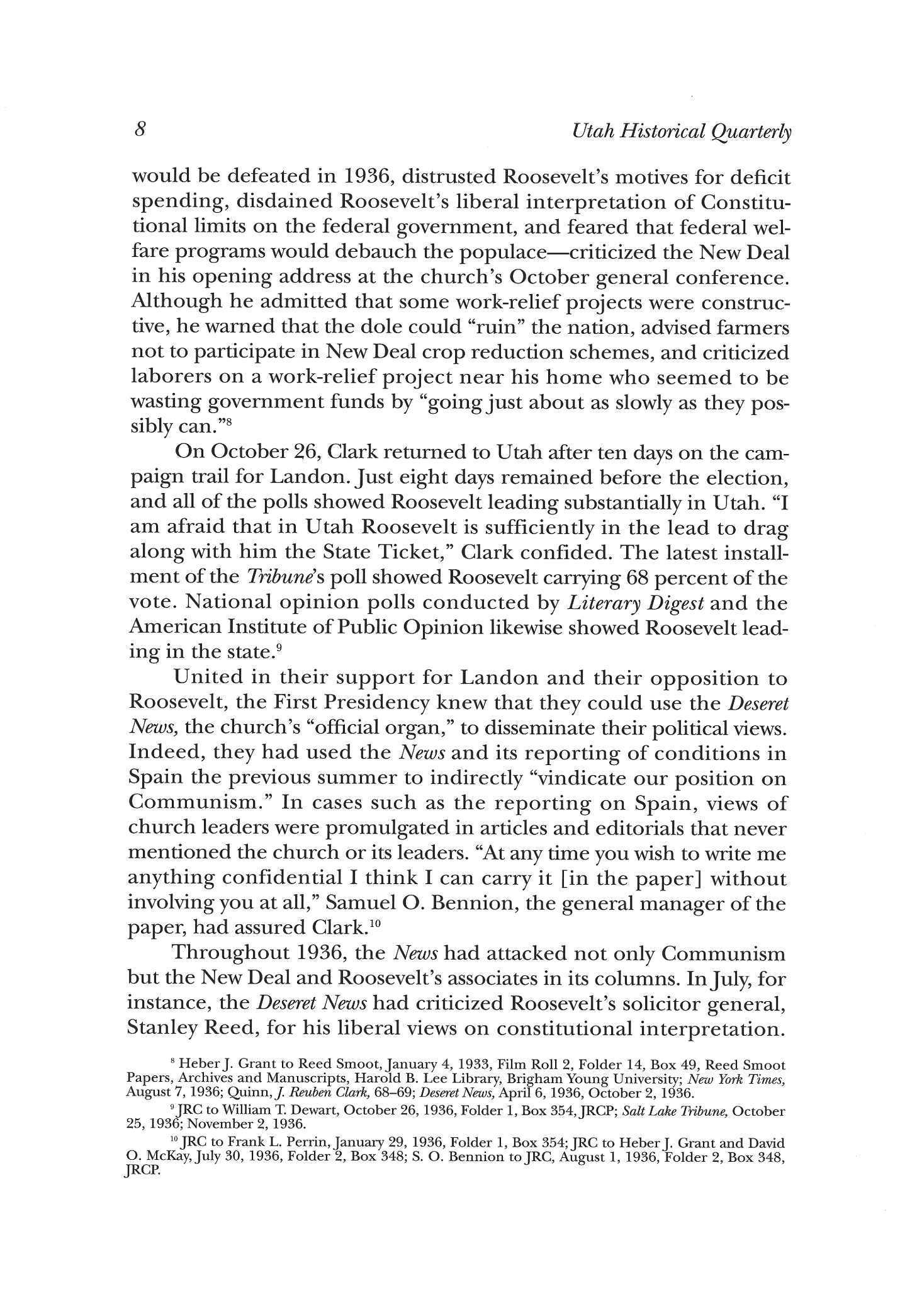

Cartoon from Salt Lake Tribune, November 2, 1936, one day before the presidential election. All photosfrom USHS collections.

Brian Q. Cannon is an associate professor of history at Brigham Young University.

I N 1936, ALFRED LANDON, THE REPUBLICAN governor of Kansas, attempted to wrest the presidency from the controversial but immensely popular Franklin D. Roosevelt. In Utah during that campaign, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, through President Heber J. Grant and counselors J. Reuben Clark and David O. McKay, made one of its few direct forays into presidential politics in the twentieth century

The efforts of church leaders to influence the campaign began to be apparent to Utahns when Clark, first counselor in the First Presidency, attended the Republican national convention inJune as a delegate at large and there helped write the Republican platform. Later that summer he spent a week in Topeka drafting speeches for Landon Standing in the church administration building upon returning from Kansas, Clark told reporters that he was "more impressed than ever 'with the sterling qualities which will make him [Landon] a great president.'" At this early date, Clark was voicing his own opinions and not speaking officially for the First Presidency, but the fact that he made these comments in the church administration building gave them a quasi-official tenor Several weeks later, the New York Times reported that Heber J Grant had expressed his "great hope" to Republican national chairman John Hamilton "that Governor Landon would be elected."1

Regardless of the views of LDS leaders, it was clear that Landon would face an uphill battle in Utah. A poll conducted in June by the American Institute of Public Opinion had shown that 63 percent of Utahns planned on voting for Roosevelt Only in traditionally Democratic states in the South did Roosevelt enjoy greater popularity.2

Some Utah Republicans attempted to turn the situation around not only by using Clark's personal endorsement of Landon but by quoting from church president HeberJ. Grant's conference addresses regarding the importance of industry, the evils of the dole, and the need to maintain the Constitution. Margaret M. Cannon, a prominent

1 New York Times, August 7, 1936; Salt Lake Tribune, July 13, 1936 The First Presidency, comprised of the prophet and his counselors—usually there are two of them—possesses "supreme authority" in the church See J Lynn England and W Keith Warner, "First Presidency," in Daniel H Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia ofMormonism (New York: MacMillan, 1992), 2:512-14 Clark's views of the Roosevelt administration and the New Deal as well as of Utah politics were colored by his extended absences from Utah while he served as functioning president of the Foreign Bondholders Protective Council, headquartered in New York City For information on Clark's work in this capacity, consult Gene A Sessions, Prophesying upon the Bones:J. Reuben Clark and the Foreign Debt Crisis, 1933-39 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992)

2 Salt Lake Tribune, June 7, 1936

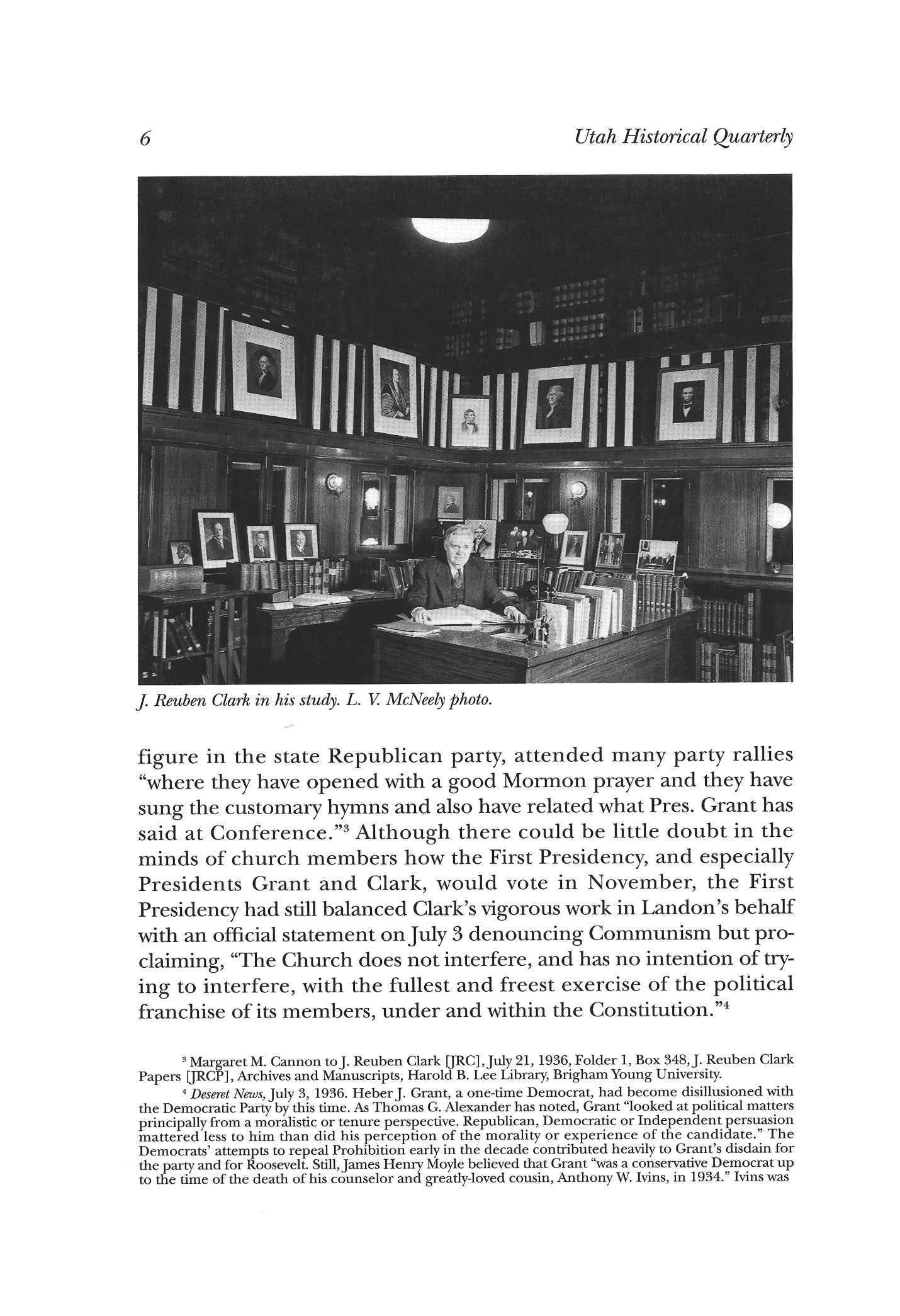

Election of 1936 5

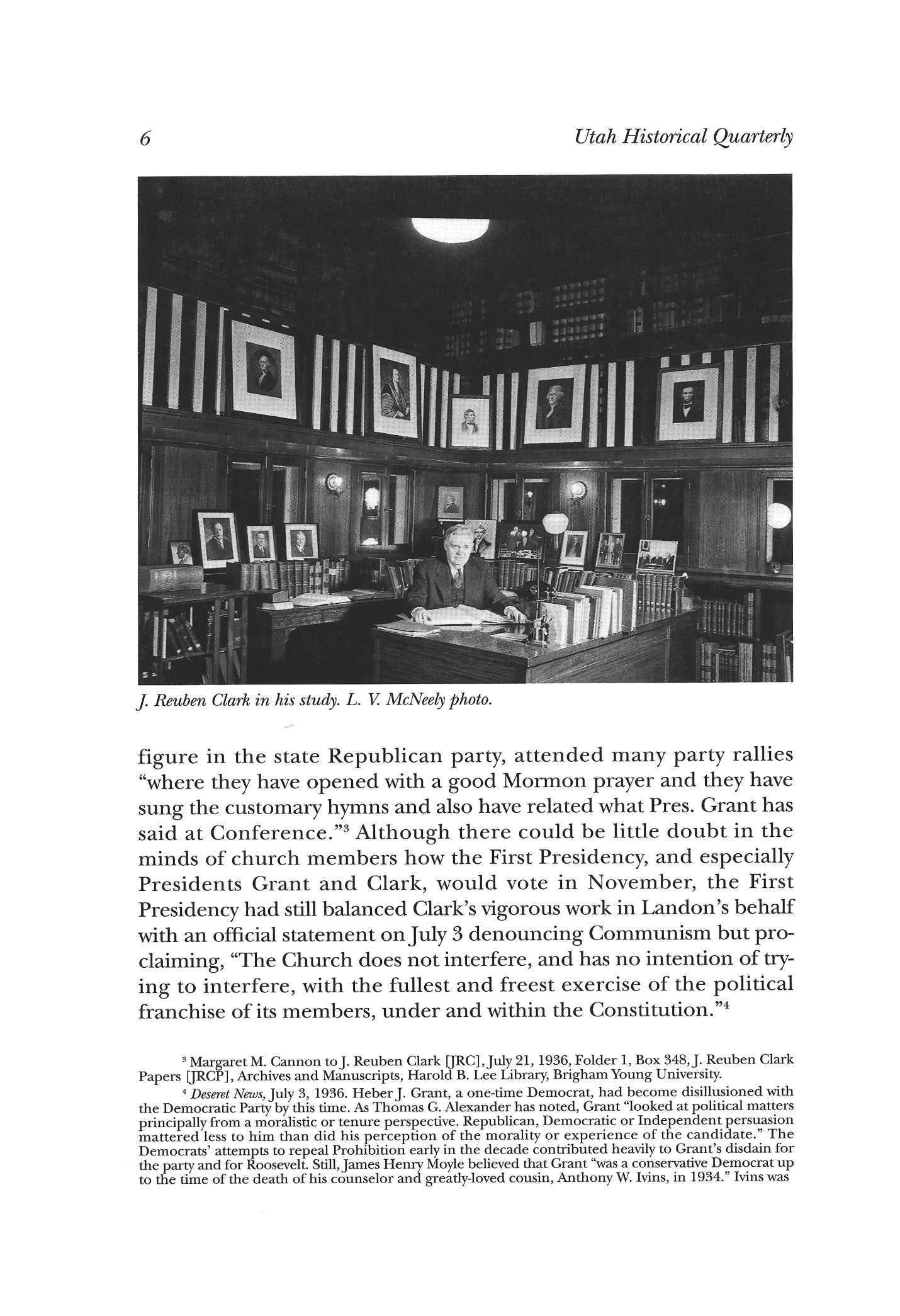

figure in the state Republican party, attended many party rallies "where they have opened with a good Mormon prayer and they have sung the customary hymns and also have related what Pres. Grant has said at Conference." 3 Although there could be little doubt in the minds of church members how the First Presidency, and especially Presidents Grant and Clark, would vote in November, the First Presidency had still balanced Clark's vigorous work in Landon's behalf with an official statement on July 3 denouncing Communism but proclaiming, "The Church does not interfere, and has no intention of trying to interfere, with the fullest and freest exercise of the political franchise of its members, under and within the Constitution."4

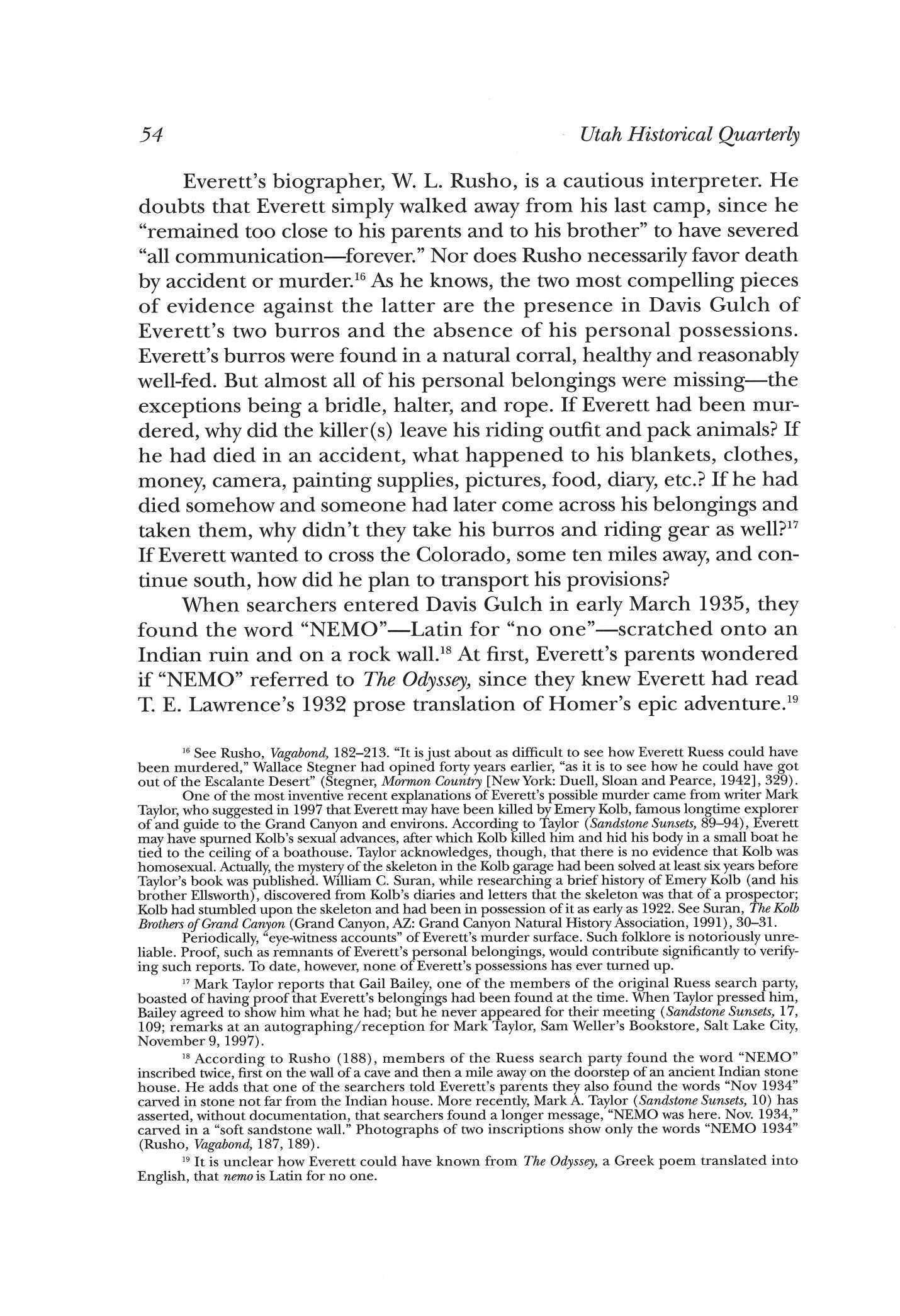

3 Margaret M Cannon toJ Reuben Clark QRC],July 21, 1936, Folder 1, Box 348, J Reuben Clark Papers [JRCP], Archives and Manuscripts, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University

4 Deseret News, July 3, 1936 Heber J Grant, a one-time Democrat, had become disillusioned with the Democratic Party by this time. As Thomas G. Alexander has noted, Grant "looked at political matters principally from a moralistic or tenure perspective Republican, Democratic or Independent persuasion mattered less to him than did his perception of the morality or experience of the candidate." The Democrats' attempts to repeal Prohibition early in the decade contributed heavily to Grant's disdain for the party and for Roosevelt. Still, James Henry Moyle believed that Grant "was a conservative Democrat up to the time of the death of his counselor and greatly-loved cousin, Anthony W Ivins, in 1934." Ivins was

Utah Historical Quarterly

f. Reuben Clark in his study. L. V. McNeely photo.

By fall, with Roosevelt's immense popularity and the First Presidency's commitment to political non-interference, the situation looked bleak for Landon among Utah voters, including the Mormon electorate The first installment of a two-month poll conducted by the Salt Lake Tribune—in which polling cards were to be mailed to every fourth person whose name appeared on voter registration rolls across the state—showed Roosevelt in the lead with 67 percent of the vote, about ten more percentage points than he had garnered in 1932.J. R. Fitzpatrick, the politically conservative publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune and a political friend of Clark's, had commiserated on September 9 in a letter to Clark reporting the results: "Only wish I had some better news to give you."5 Subsequent installments of the Tribune's poll showed a similar pattern of support for Roosevelt. Hoping to boost Landon's morale, Clark wrote to him late in September questioning the accuracy of the polls: "I find it most difficult to believe that the Tribune Poll now being conducted represents the facts." He felt instead that Landon's radio broadcasts were producing "a change of sentiment here in favor of yourself."6

Clark desired to accelerate that supposed change in sentiment but feared that direct efforts might backfire. Late in September the Republican National Committee asked Clark to deliver at least a dozen speeches in Utah supporting Landon, and Clark nearly decided to do so. His brother Ted helped to dissuade him, though. "I am fully convinced that if you go on the stump here among the Saints that much . . . respect and good feeling towards you will change. As it has to all the other leaders who have done it," Ted warned. "Many of your own side will lose confidence if you do." So Clark refused to speak for Landon in Utah "If I were to take the stump in this State, I would solidify opposition rather than gain votes," he explained Clark did agree to speak at rallies elsewhere in the West that month, though.7

For his part, Heber J. Grant—who "deep[ly] regret[ted]" that Roosevelt had defeated Herbert Hoover in 1932, hoped that Roosevelt

a strong Democrat Thereafter, under the influence ofJ Reuben Clark and David O McKay and his own objections as a fiscal conservative to New Deal financing and welfare programs, Grant became "more of a Republican than a Democrat." Thomas G Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of theLatter-day Saints, 1890-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 37, 44-45, 57; Gene A Sessions, Mormon Democrat: The Religious and Political Memoirs ofJames Henry Moyle (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 282,286

5 Salt Lake Tribune, September 6, 1936; J R Fitzpatrick toJRC, September 9, 1936, Folder 2, Box 348JRCP

6 JRC to Alfred M Landon, September 28, 1936, Folder 9, Box 347, JRCP

7 Ted [Clark] to JRC, October 1, 1936, Folder 1, Box 337; Fred S Purnell to JRC, September 24, 1936, Folder 5, Box 347; JRC to Purnell, October 7, 1936, Folder 5, Box 347, JRCP; D Michael Quinn,/ Reuben Clark: The Church Years (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1983), 75

Election of 1936 7

would be defeated in 1936, distrusted Roosevelt's motives for deficit spending, disdained Roosevelt's liberal interpretation of Constitutional limits on the federal government, and feared that federal welfare programs would debauch the populace—criticized the New Deal in his opening address at the church's October general conference. Although he admitted that some work-relief projects were constructive, he warned that the dole could "ruin" the nation, advised farmers not to participate in New Deal crop reduction schemes, and criticized laborers on a work-relief project near his home who seemed to be wasting government funds by "goingjust about as slowly as they possibly can."8

On October 26, Clark returned to Utah after ten days on the campaign trail for Landon. Just eight days remained before the election, and all of the polls showed Roosevelt leading substantially in Utah "I am afraid that in Utah Roosevelt is sufficiently in the lead to drag along with him the State Ticket," Clark confided The latest installment of the Tribune's poll showed Roosevelt carrying 68 percent of the vote. National opinion polls conducted by Literary Digest and the American Institute of Public Opinion likewise showed Roosevelt leading in the state.9

United in their support for Landon and their opposition to Roosevelt, the First Presidency knew that they could use the Deseret News, the church's "official organ," to disseminate their political views. Indeed, they had used the News and its reporting of conditions in Spain the previous summer to indirectly "vindicate our position on Communism." In cases such as the reporting on Spain, views of church leaders were promulgated in articles and editorials that never mentioned the church or its leaders "At any time you wish to write me anything confidential I think I can carry it [in the paper] without involving you at all," Samuel O. Bennion, the general manager of the paper, had assured Clark.10

Throughout 1936, the News had attacked not only Communism but

the New Deal and Roosevelt's associates in its columns InJuly, for instance, the Deseret News had criticized Roosevelt's solicitor general, Stanley Reed, for his liberal views on constitutional interpretation.

8 Heber J Grant to Reed Smoot, January 4, 1933, Film Roll 2, Folder 14, Box 49, Reed Smoot Papers, Archives and Manuscripts, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University; New York Times, August 7, 1936; Quinn,/ Reuben Clark, 68-69; Deseret News, April 6, 1936, October 2, 1936

9 JRC to William T Dewart, October 26, 1936, Folder 1, Box 354, JRCP; Salt Lake Tribune, October 25, 1936; November 2, 1936

10 JRC to Frank L. Perrin, January 29, 1936, Folder 1, Box 354; JRC to Heber J. Grant and David O McKay, July 30, 1936, Folder 2, Box 348; S O Bennion to JRC, August 1, 1936, Folder 2, Box 348, JRCP

8 Utah Historical Quarterly

Election of 1936

Indeed, to DemocratJames Henry Moyle it seemed that the paper had become "against almost everything President Roosevelt advocated."11 Some Republicans, though, thought the criticism had been too restrained In September staunch Republican Benjamin L Rich complained to Clark about a pussyfooting editorial policy that "minimizes the effect of criticism of the administration" in Deseret News articles. He observed, "If the administration is not to be criticized for its disregard of Constitutional Government as expressed in the principles underlying NRA and AAA and a lot of other of those things, then it is just too bad for the Constitution in Utah." Clark admitted that his own "feelings were not far away from full brotherhood to yours."12

The First Presidency, however, was sustained by members of a church that in 1936 was predominantly comprised of people who characterized themselves as Democrats and supported the New Deal Moreover, Grant, Clark, and David O. McKay had professed the church's political neutrality in an official statement three months earlier and had just managed to extricate the church from allegations of unfairness and ecclesiastical influence occasioned by Clark's public endorsement of a candidate for the Republican gubernatorial nomination.13 It was also possible that an official church endorsement of Landon would produce the same type of backlash that Clark feared

11 Deseret News,July 17, 1936; Sessions, Mormon Democrat, 284

12 Benjamin L Rich to JRC, September 15, 1936; JRC to Rich, September 23, 1936, Folder 2, Box 354, JRCP. NRA was the National Recovery Administration; AAA was the Agricultural Adjustment Administration

IS Salt Lake Tribune, March 15, 1936; Heber J Grant and David O McKay to JRC, August 13, 1936; JRC to Grant, August 14, 1936; McKay to JRC, August 14, 1936, Folder 2, Box 348, JRCP Clark endorsed D H Christensen, who lost in the primary election to Ray E Dillman

HeberJ. Grant and David 0. McKay, 1937. Salt Lake Tribune photo.

would arise if he stumped the state. So although the Deseret News offered church leaders a means of airing their views, there were reasons to exercise caution about promulgating those views too forcefully. Against this backdrop, the Mining and Contracting Review, a weekly miningjournal edited by Burt B Brewster, on October 27 chastised all three Salt Lake papers but especially the Deseret News, whose "heads . . . know what things are all about," for not having taken "some definite editorial stand on national and state politics." The editorial continued, "Either the owners or the editorial staffs, we know not which, unless lightning strikes while this is being written, have given the greatest exhibition of sniveling, weakkneed, and cowardly, middle of the road editorial policy—on both major sides of national politics— exhibited by any papers supposed to show character in the United States." The editorial's effect upon the First Presidency is unclear, although they did see it; Clark received a copy from his ardent Republican friend Ben Rich along with a letter warning him that "unless we have in Utah some daily newspaper which adopts, maintains, and prosecutes a continuous, vigorous, patriotic American policy, the Republican party might as well fold up."14

Whether or not Rich's letter or the editorial in the Mining and Contracting Review exerted any influence, the Deseret News soon delivered what Rich and other Republicans had hoped for: an unequivocal front-page editorial castigating the incumbent and endorsing his opponent—without naming either one Citing Grant's diary, which is now closed to research, D Michael Quinn concluded that the decision to run the editorial stemmed not from Clark's partisanship but from Grant's own conviction that, because of the serious issues at stake, "the First Presidency would have to take a very strong stand." Marion G. Romney's recollections of a conversation with Heber J. Grant support Quinn's conclusion. Grant, Romney recalled, told him, "I know they charge President Clark with this editorial, but President Clark told me not to publish it. He said they would say, 'You are using the paper for political purposes.' But I put the editorial on the front page of the news over his objections."15

Even if Grant insisted on publishing the editorial, it was Clark who wrote it. Although no complete handwritten draft in Clark's hand has been found, several typewritten drafts with corrections penned in

14 Mining and Contracting Review, October 27, 1936; Benjamin L Rich to JRC, October 29, 1936, Folder 2, Box 354, JRCP.

15 Quinn, J. Reuben Clark, 75; F Burton Howard, Marion G. Romney: His Life and Faith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988), 109

10 Utah Historical Quarterly

Election of 1936 H

the margins in Clark's hand do exist, and the arguments and examples advanced closely resemble those found in speeches Clark wrote for Landon.16 The editorial began by quoting Section 101 of the LDS Doctrine and Covenants, with a slight modification in verb tense, to demonstrate that God had established the Constitution and that he had "asserted that this Constitution 'should be maintained for the rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles.'"17

Having argued for the Constitution's divine origins, the editorial proceeded to outline Roosevelt's attitudes toward the document. The News alleged that the president had "characterized the Constitution as of 'horse and buggy days,'" a reference to a favorite whipping boy of conservatives. Roosevelt had made this spontaneous comment in a press conference on May 31, 1935, four days after the Supreme Court had ruled against the National Recovery Act, a key piece of New Deal legislation. In its decision the Court had narrowly interpreted the interstate commerce clause in the Constitution, ruling that the clause conferred upon the federal government only the right to regulate the actual shipment of goods between states Roosevelt complained, "The country was in the horse-and-buggy age when that clause was written." Now, in an era when the nation's economic and political spheres were far more integrated and when a broad interpretation of that clause was needed in order to permit the federal government to "administer laws that have a bearing on, and general control over, national economic problems and national social problems," Roosevelt had lamented, "we have been relegated to the horse-and-buggy definition of interstate commerce."18

Although Roosevelt had singled out one clause in the Constitution and although the phrase, as Thomas Alexander has observed, correctly characterized modes of travel in the eighteenth century, conservatives like Clark argued that the statement not only revealed Roosevelt's perception of the document as outmoded but also his desire to broaden in "a tyrannical fashion" presidential power at the expense of the states.19

16 Quinn, / Reuben Clark, 75; editorials found in folder labeled "Editorials 1934-39," Box 208, JRCP

17 Deseret News, October 31, 1936

18 Ibid.; Samuel I. Rosenman, comp., The Public Papers and Addresses ofFranklin D. Roosevelt (New York: Random House, 1938), 4:200-222.

19 Thomas G Alexander, Utah: The Right Place (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 1995), 331; "Topeka Draft Mainly byJRC," Folder 9, Box 347, JRCP

The editorial offered additional evidence of Roosevelt's attitudes

toward the Constitution, mentioning that he had "advised members of Congress to join in enacting laws irrespective of the belief of the Congressmen as to the constitutionality of such laws." Here Clark referred to aJuly 6, 1935, letter Roosevelt wrote to Chairman Hill of the House Committee on Ways and Means. Roosevelt had advised, "I hope your committee will not permit doubts as to constitutionality, however reasonable, to block the suggested legislation [Guffey-Snyder Coal Bill]." The editorial noted that the president who had made these statements was sworn to "preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution." In earlier drafts of the editorial, Clark had also reiterated common charges that Roosevelt was a Communist, noting that even some Democrats had "publicly accuse [d] him of sympathy or affiliation with Communism," but this allegation was removed before the editorial was printed.20

Having castigated the incumbent without mentioning his name, the editorial praised Landon as "the other candidate" because he had "declared he stands for the Constitution and for the American system of government which it sets up." Noting the LDS church's affinity for "constitutional government" the editorial concluded, "Church members, who believe the revelations and the words of the Prophet, must stand for the Constitution Every patriot, loving his country and its institutions, should feel in duty bound to vote to protect it."21

20 Deseret News, October 31, 1936; typewritten draft of editorial entitled "The Constitution," folder entitled "Editorials 1934-39," Box 208, JRCP; James P Warburg, "Hell-Bent for Election," Washington Post, September 17, 1935, copy in Folder 3, Box 88, Smoot Papers; New York Herald Tribune, March 23, 1935, clipping in folder entitled "Roosevelt," Box 314, JRCP On the passage of the Guffey-Snyder Act of 1935, see William E Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940 (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), 161-62

21 Deseret News, October 31, 1936 The entire editorial reads: "More than one hundred years ago the Lord declared: 'I establish the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose.' In the same revelation He asserted that this Constitution 'should be maintained for the rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles.'

"For many weeks The News has carried at the head of its editorial column a statement by the Prophet Joseph giving his view of the origin, purpose, and virtue of the Constitution The Prophet also declared the peculiar relationship which the people of the Church have towards the Constitution and its preservation

"We are nearing the end of a Presidential campaign

"The issues of the campaign touching the Constitution seem clearly and squarely drawn

"One candidate has characterized the Constitution as of 'horse and buggy days,' he has advised members of Congress to join in enacting laws irrespective of the belief of the Congressmen as to the constitutionality of such laws The great bulk of the pivotal legislation passed by Congress at his request, to carry out his views, has been pronounced unconstitutional Even though publicly asked to declare his intention in the matter, he has thus far failed to say that he will not continue to carry out the principles of his earlier legislation which the Supreme Court has declared unconstitutional He keeps his silence in face of the fact that if he be elected he must take an oath—the same which he took when he first became President—that 'I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States [']

"The other candidate has declared he stands for the Constitution and for the American system of government which it sets up He makes it clear that he will keep inviolate the oath which he must take as President of the United States He has shown himself to be an honest, truthful man, a patriotic efficient public servant

12 Utah Historical Quarterly

Although Clark wrote the editorial, it reflected the position of all three members of the First Presidency and was approved by each of them Writing to David O McKay the following year, Clark referred to the document along with two subsequent editorials as "our Deseret News editorials."22

The editorial, showcased on the front page and opposing not specific policies but the personification of the entire New Deal, was far more strident and controversial than the paper's previous depressionera editorials Although it did not directly link the first presidency to the message, O. N. Malmquist, political columnist for the Tribune in the 1930s, believed that it was "doubtful that the church leadership had ever taken a stronger stand against one candidate and for another, either publicly or within organization ranks, than in the 1936 election."23

Predictably, therefore, the editorial raised a "rumpus." Its tone was less strident than that of an editorial appearing the following morning in the Salt Lake Tribune that criticized Roosevelt even more heavily, accused his administration of sympathizing with Communism, and argued that "the election of Governor Landon . . . is the quickest and surest way back to constitutional government and the American tradition." Nevertheless the News's statement attracted more attention because of its ties to the LDS church. Utah Republicans hailed the editorial, along with the Tribune's endorsement of Landon, as "courageous" and in last-minute campaigning they attempted to capitalize upon the constitutional arguments, billing their candidates as defenders of the Constitution. "After having the issues discussed and after reading the courageous editorials in Utah's two great daily papers . . . are you not convinced that there are more vital issues in this campaign than have confronted the citizens of this great nation since the Civil War?" a Republican advertisement queried. "Only in the Republican party platform can a citizen

"The Church and its membership have always stood for constitutional government; they have resisted with all their might every effort to impair it, or to curtail our liberties, or to destroy our free institutions set up and guaranteed by it, no matter where such effort originated or in what disguise it came The First Presidency, obedient to the principles of the Church, have admonished Church members against Communism, and against all persons wherever placed, who in any way advocate or sustain it "Church members, who believe the revelations and the words of the Prophet, must stand for the Constitution Every patriot, loving his country and its institutions, should feel in duty bound to vote to protect it."

22 JRC to David O McKay, February 6, 1937, Folder 1, Box 358, JRCP

23 O. N. Malmquist, The First 100 Years: A History of the Salt Lake Tribune, 1871-1971 (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1971), 331 Malmquist was correct in his remarks about opposition to one candidate, although Joseph F Smith's endorsement of William Howard Taft in the October 1912 Improvement Era was crystal clear On Smith's 1912 endorsement see Frank H.Jonas and Garth N.Jones, "Utah Presidential Elections, 1896-1952," Utah Historical Quarterly 24 (October 1956): 298.

Election of 1936 13

feel certain that his constitutional rights will continue to be enjoyed," declared national committeeman George W. Snyder the day before the election Jesse R Smith, a Mormon attorney practicing in the nation's capital, aptly expressed the views of Republican Mormons who supported the editorial "I for one wholeheartedly commend the leaders of the Church for the position they have taken in connection with our duties and responsibilities as American citizens. When a cardinal principle of our faith is placed in jeopardy, albeit through the forces of political campaign, there can be but one position for every thoughtful Latter-day Saint."24

Some Democrats were amused: A S. Brown, National Democratic Committeeman for Utah, reportedly quipped, "If the Deseret News and the Mormon church can carry the state of Utah for Alf Landon, I'll join the church because I'll have seen a miracle." Most Utah Democrats were shocked or embittered rather than amused, though Taking no chances, Democratic politicians disputed the editorial, billing Roosevelt as a defender and savior of the Constitution. At a rally in Bingham the night before the election, state Democratic chairman Calvin W. Rawlings, an active Mormon, labeled the attacks on Roosevelt "false and unwarranted" and claimed that "President Roosevelt saved the Constitution and our democracy against the only threat of their destruction in my lifetime or yours." Pointing out that great presidents likeJefferson, Jackson, and Lincoln had acted beyond the scope of the Constitution in "champion [ing] the cause of the com-

14 Utah Historical Quarterly

E. 0. Howard, president of Walker Bank and Trust, and A. S. Brown, National Democratic Committeemanfor Utah, at chamber of commerce breakfast meeting in 1938. Salt Lake Tribune photo.

24 JRC to David O McKay, February 6, 1937, Folder 1, Box 358; Jesse R Smith to JRC, November 3, 1936, Folder 2, Box 354, JRCP; Salt Lake Tribune, November 1, 1936; Salt Lake Tribune, November 2, 1936; Salt Lake Tribune, November 3, 1936

mon people," Rawlings reminded his audience that Roosevelt's "horse and buggy" remark had been a spontaneous reaction to the Supreme Court's decision Democrats also took indirect aim at the editorial Governor Henry Blood indirectly referred to it and similar statements as a "last minute effort . . . aimed at arousing animosity, hatred and prejudice," while Rawlings labeled such efforts "slanderous."25

In full-page ads in Utah newspapers Democrats proclaimed that "Roosevelt Saved the Constitution" by "restoring peace and prosperity." Quoting Roosevelt that the "flag and the Constitution stand for democracy, not tyranny; for freedom, not subjection, and against a dictatorship of mob rule and the OVERPRTVILEGED alike," the ads criticized the church for violating Utah's Constitutional prohibition against religious domination of politics They encouraged Mormons, "Have no fear of frightening cries of Republican reactionaries who would inject church influence in this campaign. American people resent church interference. Latter Day Saints will not be swayed by such attempts. They have a safe guide in their own Doctrine and Covenants which says, 'We do not believe itjust to mingle religious influence with civil government.'"26

In a front-page editorial on November 2, the Logan HeraldJournal, one of the state's most liberal city papers, rebutted the stance taken by the Deseret News and Salt Lake Tribune, labeling both papers as part of "Utah's capitalistic press." The Logan paper particularly criticized the Deseret News. Referring to prominent Republicans in the church hierarchy, including former senator Reed Smoot and J. Reuben Clark, the Herald-Journal averred that the stance taken by the Deseret News had been "inspired by the political bitterness of those who sat in high places and who were confidants of those who ruled before the present administration." Dismissing the argument that Roosevelt had jeopardized the Constitution as "so absurd and farfetched as to be ridiculous," the paper praised the New Deal for improving economic conditions and thereby reducing the likelihood of revolution Whereas the Deseret News had enlisted religion in support of Landon, the Herald-Journal linked Roosevelt's program to deity. "In our humble opinion, Destiny produced the man who successfully was to lead us through a period of calamity . . . [W]ell may

25 Frank Herma n Jonas, "Utah: Sagebrush Democracy," Rocky Mountain Politics, Thomas C Donnelly, ed (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1940), 34; Calvin L Rampton, As I Recall (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1989), 47; Salt Lake Tribune, November 3, 1936

26 Salt Lake Tribune, November 2, 1936; Deseret News, November 2, 1936; Salt Lake Telegram, November 2, 1936

Election of 1936 15

the American people thank God for giving us a fearless, daring pilot."27

On the eve of the election, the Deseret News, as a response to criticism that the church had taken a partisan stance after having pledged not to interfere politically, printed a second editorial by Clark. Reiterating the First Presidency statement ofJuly 3, 1936, that "the Church does not interfere, and has no intention of trying to interfere, with the fullest and freest exercise of the political franchise of its members," the News justified its October 31 volley on the grounds that "great moral issues are involved" and that "great principles of Church belief or doctrine are in peril." The paper "would be recreant to the public trust... if it did not tell the people of its views on great public questions." Although an earlier draft of this editorial had guaranteed only that the church would not "discipline" members for supporting Roosevelt, the final version went further and pledged that the church would not "look with disfavor upon any member for the free exercise of his franchise."28

On election day, in a state where nearly seven in ten residents were LDS, 69.3 percent of Utah's voters endorsed Franklin D Roosevelt at the polls. Only Kane County registered more votes for Landon than for Roosevelt. "Obviously the people have not learned their lesson. The largesse of the Emperor still speaks with the multitude," Clark ruefully remarked. If anything, support for Roosevelt had solidified following the editorial. Only 66.6 percent of the respondents polled by the Tribune in the last two weeks of October indicated that they would vote for Roosevelt at the polls, but 69.3 percent of Utah's voters did so—a higher percentage than in any of the installments of

27 Logan Herald Journal, November 2, 1936 In particular, Apostle Reed Smoot, who in 1932 had been defeated in his bid for reelection after having represented Utah in the U.S. Senate for nearly thirty years, had been a strong supporter of the Hoover Administration Hoover campaigned for Smoot in Utah just before that election, praising his work in the Senate For information on the 1932 Smoot campaign and Herbert Hoover's role in it, see Milton R Merrill, Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1990), 135-37, 230, 232-33.

28 Deseret News, November 2, 1936; typescript draft of editorial entitled "A Principle of Church Rule," folder labeled "Editorials 1934-39," Box 208, JRCP The final version in its entirety reads, "In their Signed statement ofJuly 3, 1936, regarding Communism, the First Presidency said: "'The Church does not interfere, and has no intention of trying to interfere, with the fullest and freest exercise of the political franchise of its members, under and within the Constitution, which the Lord declared: "I established .. . by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose," and which as to the principles thereof, the Prophet, dedicating the Kirtland Temple, prayed should be "established forever.'"

"The NEWS understands this to be the rule of the Church It would regard as UnAmerican any suggestion that the Church would look with disfavor upon any member for the free exercise of his franchise.

"But where great moral issues are involved or where great principles of Church belief or doctrine are in peril, the NEWS as a responsible newspaper reaching thousands of readers feels it would be recreant to the public trust which its character necessarily vests in it, if it did not tell the people of its views on great public questions."

16 Utah Historical Quarterly

the Tribunes two-month poll. Roosevelt in 1936 received a higher percentage of the vote than had any previous presidential candidate in Utah, aside from William Jennings Bryan in 1896 Not until Richard Nixon's landslide reelection in 1972 would a candidate for president again receive as high a percentage of the votes as Roosevelt received that year. 29

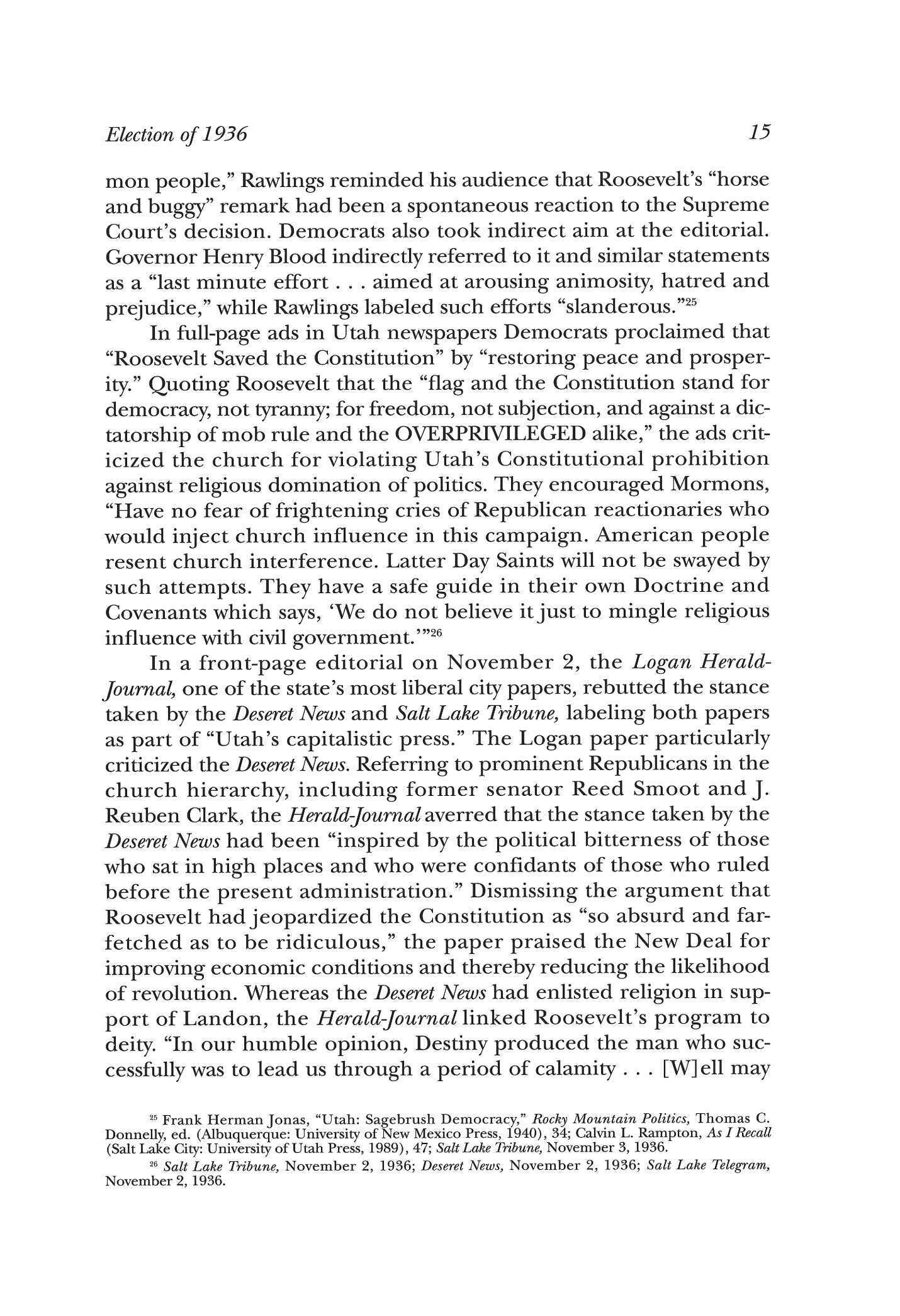

Roosevelt's stunning success notwithstanding, the editorial had led to much soul-searching among some loyal Democrats and did persuade some of them to vote for Landon Marion G Romney, a Mormon bishop and Democratic state legislator working on a campaign committee in Salt Lake County, resigned from the committee and publicly broke with the Democrats after reading the editorial and praying about it for three hours. In the Salt Lake Seventeenth LDS Ward testimony meeting on the day after the editorial appeared, three of the first four speakers announced their intention to vote for Landon as a result of the editorial. Even more statements might have been forthcoming if the bishop had not asked the congregation to desist from further political commentary in the meeting.

Although she almost certainly voted for Roosevelt, one member of the Seventeenth Ward congregation, Edna Thomas, whose husband, Senator Elbert Thomas, was in California at the time campaigning for Roosevelt, felt particularly torn in her loyalties. After the election she and her husband attended a dinner party where the Deseret News and its editorial campaign were roundly condemned. Returning from the party she confided in her diary, "I came home feeling quite guilty because we had made so much fun of Pres. Grant and criticized the writing of the editorial in the News. I really feel quite guilty I receive many, many blessings, that I do not show much appreciation [for] when I make fun of sacred things."30

The day after the election, the News printed a third editorial by Clark, acknowledging that Roosevelt had been re-elected by constitutional means and that any attempt to "modify or change that decision" must be "by constitutional means and not by force." The editorial concluded by reiterating the paper's right and obligation to speak out on "great public questions."31

29 Tonas and Tones, "Utah Presidential Elections," 301-302; Table K, Richard D. Poll, ed., Utah's History (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1989), 700-701; JRC to Alfred Landon, [November 9 1936], Folder 10, Box 347, JRCP; Salt Lake Tribune, November 1, 1936; Salt Lake Tribune, November 5, 1936.

30 Howard, Marion G. Romney, 100-102; Edna Harker Thomas, "Diary," November 1, 1936, Box 3, Elbert D Thomas Collection, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City

31 Deseret News, November 4, 1936 The final version reads:

Election

•*•'

of 1936

An earlier draft of the editorial contained statements that were removed before the editorial was published. Reminding the readers that the paper had editorialized against repeal of Prohibition and that the public had disregarded that appeal, the draft noted, "Few who think and know will deny that conditions are far worse today than under Prohibition." Now the readers had rejected the News's advice regarding the election, but that did not make the advice wrong Linking the editorial with the cause of righteousness, the draft concluded, "If it [Deseret News] shall fail to carry the people with it, it will not be the first time in the history of the race, the Church, or the cause of the Master that a voice crying in the wilderness has gone unheeded."32

Unwelcome might have been a better word than unheeded, for the editorial triggered considerable correspondence and discussion For every three letters received by the First Presidency that applauded the editorial, seven opposed it. Even many supporters referred to widespread disdain and contempt for the stance taken by the Church. Writing to Clark,Joel Ricks believed that members of "the better class" agreed with Clark but estimated that at least twice as many people opposed it. "I would not be surprised to see a move to 'oust' you from office, all three of you," he observed Roosevelt's overwhelming victory at the polls demonstrated the strength of "what you have to meet and overcome."

D R Roberts, a lawyer residing in Ogden who "endorse

D R Roberts, a lawyer residing in Ogden who "endorse

[d]

"Under the Constitution of the United States the People of the United States are sovereign They declare their sovereign will through the voice of majorities

"The Sovereign People have duly declared their will through the constitutional methods they have provided. It is the high, patriotic duty of every citizen to accept their decision. It is the right of every citizen to see, by constitutional means, to modify or change that decision if he does not agree therewith, but he must do it by constitutional means and not by force

"As declared in our editorial Saturday last:

"'The Church and its membership have always stood for constitutional government; they have resisted with all their might every effort to impair it, or to curtail our liberties, or to destroy our free institutions set up and guaranteed by it, no matter where such effort originated or in what disguise it came.'

"On Monday we repudiated any suggestion that we aimed or desired to coerce the people in their franchise We reiterate that repudiation now But we also stated that 'where great moral issues are involved or where great principles of Church belief or doctrine are in peril, THE NEWS as a responsible newspaper reaching thousands of readers feels it would be recreant to the public trust which its character necessarily vests in it, if it did not tell the people of its views on great public questions.'

"While freedom of the press remains, THE NEWS will continue to follow this course."

32 Typewritten draft of "The Sovereign Will," folder labeled "Editorials 1935-39," Box 208, JRCP.

18 Utah Historical Quarterly

ElbertD. Thomas, U.S. senator from Utah, 1933-1951.

with my whole soul the News (Front page) editorials of Oct 31st and Nov 2d" as "a very timely warning," found "most painful . . . the action and attitude of many of our people" in their "criticism" of the First Presidency.33

Few letters from readers that were published by the Deseret News referred directly to the editorial. Sylvester Earl, a resident of Virgin, Utah, did decry "all the aspersions and malign and false accusations against the character of Franklin D Roosevelt by his political and financial enemies." The clearest rebuttal to the editorial that appeared in the paper was written by W. A. Adams of Garland. Adams observed, "I have been taught from my youth by my parents and Church leaders that not only the framers of the Constitution were inspired, but our presidents from Washington down were entitled to inspiration, so long as they worked for the interests of all the people." This had not been the case in the 1920s, when those in power had "chosen to protect the strong at the expense of the weak until all became weak." To rescue the nation from this plight, Adams believed, "the Lord raised up Franklin D. Roosevelt." Roosevelt on inauguration day in 1933 had prayed to God "to help and inspire him to fight humanity's cause." Decrying the "coercion of the press, the cry of 'Constitution Violator,' 'Communist' and 'dictator,'" Adams exulted that Roosevelt had trounced his opponents.34

In the ensuing weeks, other supporters of Roosevelt attempted to identify him with God and righteousness, indirectly rebutting the First Presidency's stance. Lloyd O. Ivie, in a letter to the editor printed nearly a month after the election, refuted the argument that Roosevelt was "an enemy of democracy and constitutional government" by referring to Roosevelt's endorsement in a recent speech of "the Democratic form of constitutional representative government," religious freedom, and trust in God He reasoned that Mormons "should more than any other people in the world, rejoice in and sustain a president who

Election of 1936 19

Edna Harker Thomas.

33 Quinn,/ Reuben Clark, 75; Joel Ricks to JRC, November 19, 1936, Folder 2, Box 354; D R Roberts to JRC, December 5, 1936, Folder 2, Box 354, JRCP

34 Deseret News, November 13, 1936; Deseret News, November 14, 1936.

stands for such ideals." Ivie was convinced that "the voice of the divine is speaking through that inspired leader."35

The Deseret News's foray into political editorializing was disastrous from a business standpoint Already operating in the red, with subscriptions dwindling because of the depression, the News lost more than 1,200 subscribers after printing the editorial, according to Frank Jonas All told, the News had 11 percent fewer readers in 1940 than it had commanded a decade earlier, and although there were many reasons for the decline, the paper's political commentary did not help. By the 1940s, Democrat James Moyle could name "a number of good saints [who] have cancelled their subscriptions" because they objected to the paper's "nearly seditious editorial policy." Seeking for ways to overcome the paper's "difficulties" and to bolster subscriptions in 1937, the First Presidency considered bringing a non-Mormon editor aboard but refused to relinquish their influence over editorials. "We should always control the editorial policy of the paper," Clark insisted.36 Incensed by the fact that the state's major newspapers had openly opposed Roosevelt's re-election, Utah Democrats approached several newspapermen, includingJ. David Stern of the Philadelphia Record, trying to interest someone in establishing a Democratic paper in Salt Lake City "in order to save our party the embarrassment in the future, of having a practically united press against it." With three papers already operating in the city, though, they realized that obtaining "a real news service for the paper" would be difficult.37

The editorial did little to improve rapport between the Democratic leadership in Utah and the church, and it helped to associate the church

35 Deseret News, December 2, 1936

36 Sessions, Mormon Democrat, 285; Jonas, "Utah: Sagebrush Democracy," 34; Peggy Peterson Barton, MarkE. Peterson: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 79; Wendell J Ashton, Voice in the West: Biography of a Pioneer Newspaper (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1950), 399; JRC, untitled typewritten memorandum regarding Deseret News, filed in untitled brown binder containing memoranda prepared byJRC and sent October 21, 1937, to Heber J Grant and David O McKay, Folder 1, Box 358, JRCP Salt Lake Tribune's opposition to Roosevelt's bid for re-election also alienated many readers Ernest L Nelson reported, "So many people refused to subscribe to one paper in the State because of its stand on the election that it lost nearly one-third of its subscribers and the remainder read the large morning daily grudgingly." Ernest L Nelson to J David Stern, December 8, 1937, Box 21, Elbert D Thomas Papers, Utah State Historical Society

37 A. S. Brown to Elbert D. Thomas, January 19, 1937; Thomas to Brown, January 25, 1937; Ernest L. Nelson to J. David Stern, December 8, 1937; Nelson to Thomas, December 21, 1937, Box 21, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

20 Utah Historical Quarterly

foelE. Ricks.

Election of 1936 21

with the Republican party in the minds of many residents of the state. "The oligarchy of the Democratic party, now in power, is made up chiefly of non-Mormons and impious members of the Church. . . . Democratic leaders like nothing better than to have the Mormon Church endorse a rival candidate, for official Church approval makes it easier, they say, to 'knock him over.' They do not seek Church endorsement for their own candidates," political analyst FrankJonas wrote in 1940 Although it was still possible for active Mormons to rise to prominence in the state Democratic Party after the First Presidency's campaign to defeat Roosevelt in 1936, the 1936 election certainly encouraged resentment toward the church, its newspaper, and its leaders, a resentment that would not easily be forgotten.38

Although the 1936 editorial campaign divided

church members, alienated some subscribers, offended Democrats, and did not materially change election results, the debacle did not convince the First Presidency to avoid interfering in national politics, although it may have made them more cautious The following spring, Grant visited with a church member in Nevada who suggested that the First Presidency directly repudiate the New Deal. Grant wrote to McKay, "I have sometimes thought the same thing, but we don't seem to be a unit, and until we are I guess it is wise to let things alone."

When Roosevelt proposed "packing" the Supreme Court in 1937, Clark and McKay opposed a milquetoast editorial written by a Deseret News employee; but Clark recommended that it would be best for the

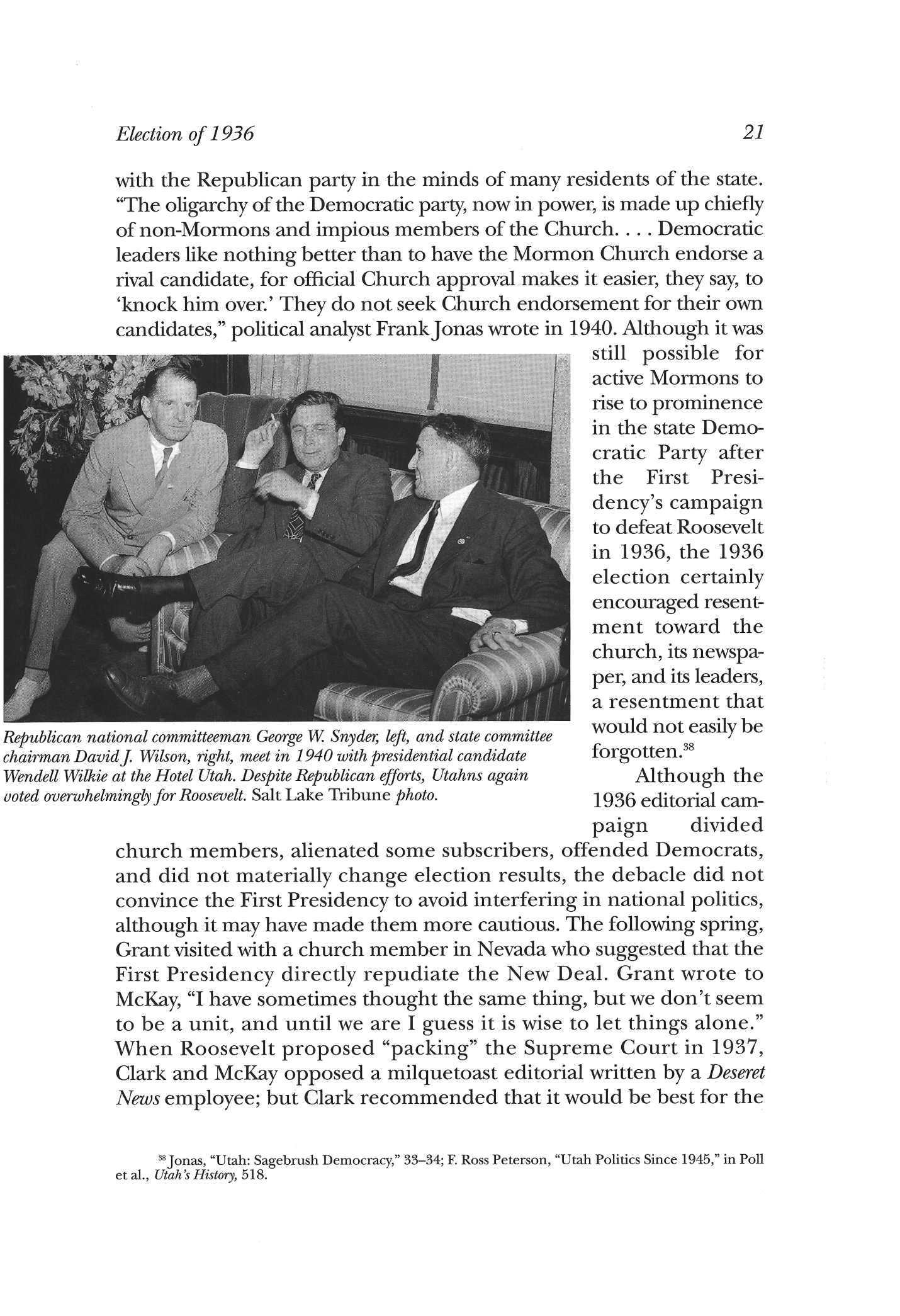

Republican national committeeman George W. Snyder, left, and state committee chairman David f. Wilson, right, meet in 1940 with presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie at the Hotel Utah. Despite Republican efforts, Utahns again voted overwhelmingly for Roosevelt. Salt Lake Tribune photo.

38 Jonas, "Utah: Sagebrush Democracy," 33-34; F Ross Peterson, "Utah Politics Since 1945," in Poll etal., Utah's History, 518

Republican national committeeman George W. Snyder, left, and state committee chairman David f. Wilson, right, meet in 1940 with presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie at the Hotel Utah. Despite Republican efforts, Utahns again voted overwhelmingly for Roosevelt. Salt Lake Tribune photo.

38 Jonas, "Utah: Sagebrush Democracy," 33-34; F Ross Peterson, "Utah Politics Since 1945," in Poll etal., Utah's History, 518

News to print editorials from several New York papers opposing the scheme rather than stirring up controversy with an editorial of its own. In 1938 Clark, who was in New York at the time, drafted an editorial for the front page of the Deseret News criticizing Utahns for their heavy reliance upon New Deal assistance to the elderly. When McKay and Grant met to review it, Grant was reluctant to publish it and wondered whether "a milder treatment should be applied first."39

The 1936 editorial fiasco, along with Utah's rejection of Heber J. Grant's plea for Prohibition in 1933, marked the nadir of the LDS church's political influence in Utah. It demonstrated how Utah's strongly worded decree separating church and State, a prerequisite for admission to the Union that few Mormons in 1896 would have supported if Congress had not required it, had become for many Utah Mormons a fiercely guarded guarantee of agency. Most Utah Mormons in the 1930s did not believe their prophet's realm extended to politics. Voter response to the editorial contrasted sharply with Utahns' respect for President Joseph F. Smith's 1912 endorsement of William Howard Taft. Church leaders such as Grant who could remember the tremendous political power wielded by prophets and apostles in an earlier era believed that they spoke with inspiration not only in matters of doctrine or morality but also in matters of politics and economics; by the 1930s, however, they found that most members disregarded their counsel in those realms. It was almost as if politicians had supplanted prophets in politics, with some Utah Mormons claiming that Roosevelt had been raised up by God and that the "voice of God [was] heard in Pres. Roosevelt's words." "About half the Latterday Saints almost worship him," Grant complained.40

Senator Elbert D. Thomas viewed support for Roosevelt more optimistically, praising Utahns who had voted for Roosevelt and blaming the First Presidency for their "lack of astuteness." "I have always felt that the people were probably slow at learning, but since the election of 1936 I have learned that it is the mighty ones who are gullible They were the ones who were taken in. The people minded their own business and voted their bestjudgment, and, heaven knows," he concluded, "they voted right."41

40

22 Utah Historical Quarterly

39 Quinn,/. Reuben Clark, 78; David O. McKay to JRC, February 6, 1937, Folder 1, Box 358; JRC to McKay, February 8, 1937, ibid.; JRC to McKay, January 17, 1938, ibid.; McKay to JRC, January 22, 1938, ibid., JRCP

Jonas and Jonas, "Utah Presidential Elections," 298, 306;John F Bluth and Wayne K Hinton, "The Great Depression," in Poll, 491; DeseretNews, December 2,1936; Quinn, / Reuben Clark, 69. In 1912 only Utah and Vermont voted for Taft, and Utah's vote was partly attributable toJoseph F Smith's endorsement of Taft

41 Elbert D Thomas to H Grant Ivins, December 8, 1936, Box 16, Elbert D Thomas Papers, Utah State Historical Society

A 200-ton boulder deposited by floods near Davis Creek, Davis County. Probably taken in 1930 by U.S. Forest Service. All photos from USHS collections.

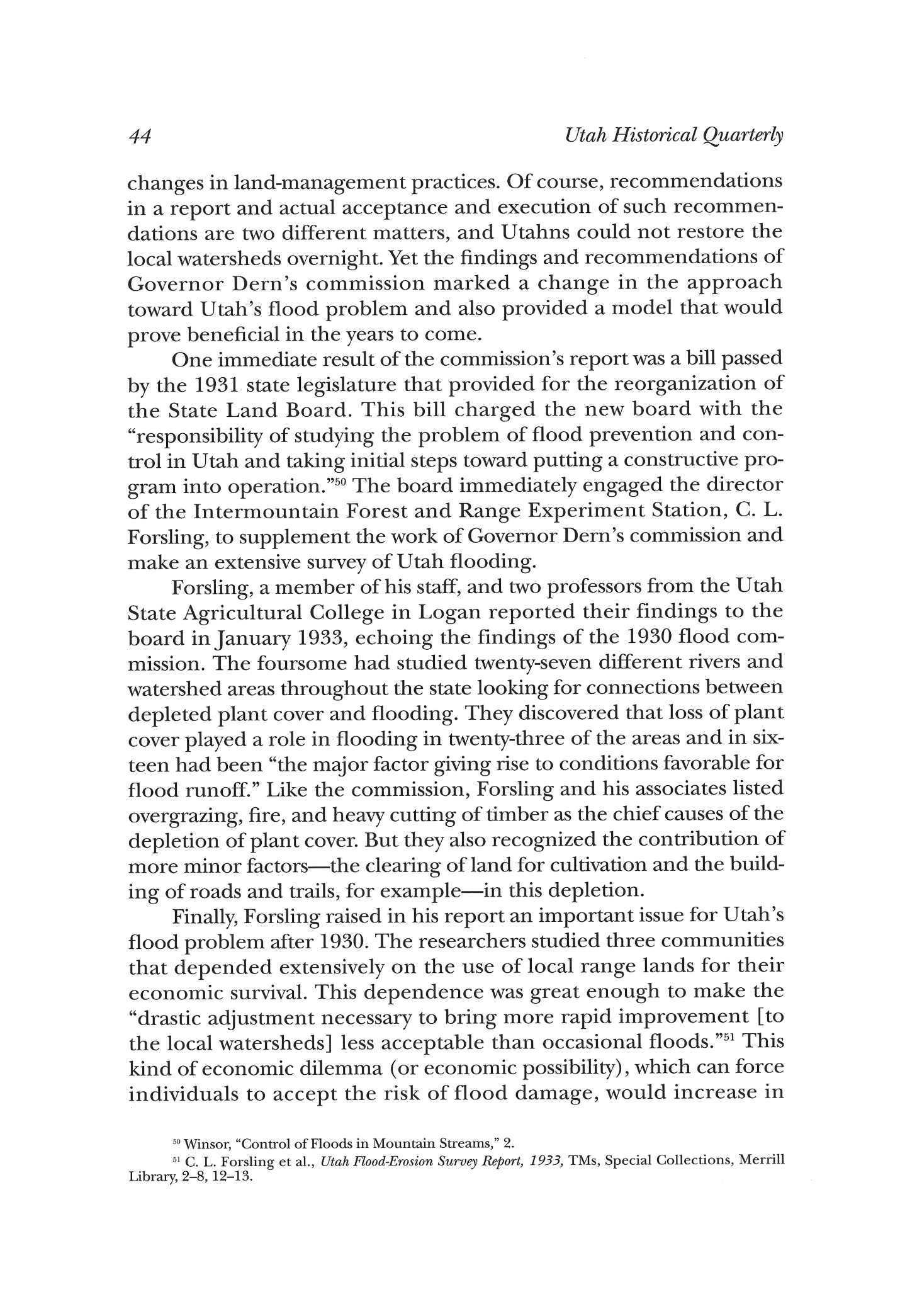

"Been Grazed Almost to Extinction": The Environment, Human Action, and Utah Flooding, 1900-1940

BYANDREW M HONKER

BYANDREW M HONKER

North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, 1908.

Andrew M Honker is pursuing his doctorate at Arizona State University, where he studies environmental history and the American West This article is based in part on his M.A thesis, which he completed at Utah State University

O N JULY 10, 1930, ELLA M DALE—who lived with her husband in Weber Canyon, southeast of Ogden, Utah—heard a roar outside her home that sounded like "an approaching freight train." After her husband assured her that the train was not due, Dale opened her door and watched as "a flash of lightning struck the high tension wires on the north side of the canyon and flashed along them, lighting up the entire gorge. Then the rain came down in sheets and the rocks and dirt followed it." Some 250,000 tons of debris washed down Weber Canyon that day, "with boulders piled 35 feet high and extending over a distance of 400 feet."1

Utah is the nation's second most arid state—only Nevada receives less moisture annually than Utah's average of thirteen inches—but flooding as a natural process has occurred in the area for thousands of years. 2 The combination of Utah's topography and erratic climate creates an ideal situation for periodic flooding Due to seasonal disparities in precipitation, many of Utah's smaller streams remain completely dry during part of the year. Such dry water courses, along with other desert surfaces, canyons, and gullies, provide an outlet for flash flooding during periods of unusually heavy precipitation. Heavy winter snows and low spring temperatures create a snowpack susceptible to rapid melting in late spring when temperatures jump, unleashing water from an entire winter onto the valleys below Finally, cloudburst storms can dump huge quantities of water onto already-saturated or otherwise impaired mountain watersheds, sending a wall of water and debris down canyon streambeds.3

The physical setting to which Brigham Young brought the initial Mormon settlers in the summer of 1847 had a long history. Natural forces, primarily wind and water, had shaped and eroded the landscape, and flooding had long been a naturally occurring phenomenon. Various cultures and peoples had lived in, explored, and used the area to which the Mormon pioneers came. These earlier peoples had exploited the natural flora and fauna, and some had developed irrigation.4 Utah was not a virgin uninhabited wilderness in the summer of 1847, but the arrival of Brigham Young's band and the thou-

1 Salt Lake Tribune, July 11, 1930

2 Bill Weir, Utah Handbook (Chico, CA: Moon Publications, 1989), 5

3 Robert L Layton, "Utah: The Physical Setting," in Richard D Poll et at, ed., Utah's History (1978; reprint ed., Logan: Utah State University Press, 1989), 18; Weir, Utah Handbook, 7.

4 Native

24 Utah Historical Quarterly

irrigation systems usually consisted of simple dams and gravity-fed ditches supplied by streams as opposed to the deep ditches, pipelines, and culverts that were introduced later and are still used by modern Utah farmers

Utah Floods 25

sands that followed did mark a new era for the region. Less than five years after their entrance into the Salt Lake Valley, Mormons had to cope with flooding, and in 1862 flood waters plagued much of Utah from February to June, sweeping away almost every bridge in the region and demolishing roads, fields, and homes. A continuing war against rising and rushing waters, with the damage they may bring, had begun

From the beginning of statehood in 1896 to the beginning of World War II, Utahns greatly increased the number and means of flood control projects in their ongoing battle against inundation During this period, they built barrier dams, catchment basins, spillways, and channel control structures, all in an attempt to establish some human control over flood waters. This period also saw the introduction of the federal bureaucracy into the local flood control effort through Civilian Conservation Corps camps and workers and the increased federal control of public lands. Unfortunately, the expansion of engineering projects and the influx of federal workers and funds failed to protect Utahns from flood waters. In many areas, Utahns had to battle the results of their own use of the land: severely impaired watersheds that increased the frequency and devastation of floods

On July 1, 1902, Albert F. Potter, chief grazing officer of the U. S. Department of the Interior's Division of Forestry, stepped off the train in Logan, Utah Gifford Pinchot, head of the Division of Forestry, had assigned Potter the task of surveying the mountainous forest land of eastern Utah for inclusion in federal forest reserves. Potter spent five months crisscrossing the Wasatch Mountains and Colorado Plateau from the Idaho border to Escalante. During his journey, he kept a diary noting the effects of a half century of grazing and lumbering on the condition of the region's watersheds and timberlands.5

Potter's diary describes countless areas that logging enterprises or local citizens had completely cut over, sometimes more than once. Descriptions such as "only trees too small for telephone poles are now left," "timber cut very clean in the places which were easily reached," and "every tree (and seedling) has been cut" are common in the diary. In the vicinity of Alta, east of Salt Lake City, Potter noted that the area "has been worked until both the ore and timber were pretty well

5 Albert F Potter, "Diary of Albert F Potter, July 1, to November 22, 1902," photocopy, Special Collections, Merrill Library, Utah State University, Logan, Utah; Charles S Peterson, "Albert F Potter's Wasatch Survey, 1902: A Beginning for Public Management of Natural Resources in Utah," UtahHistorical Quarterly 39 (Summer 1971): 238-53

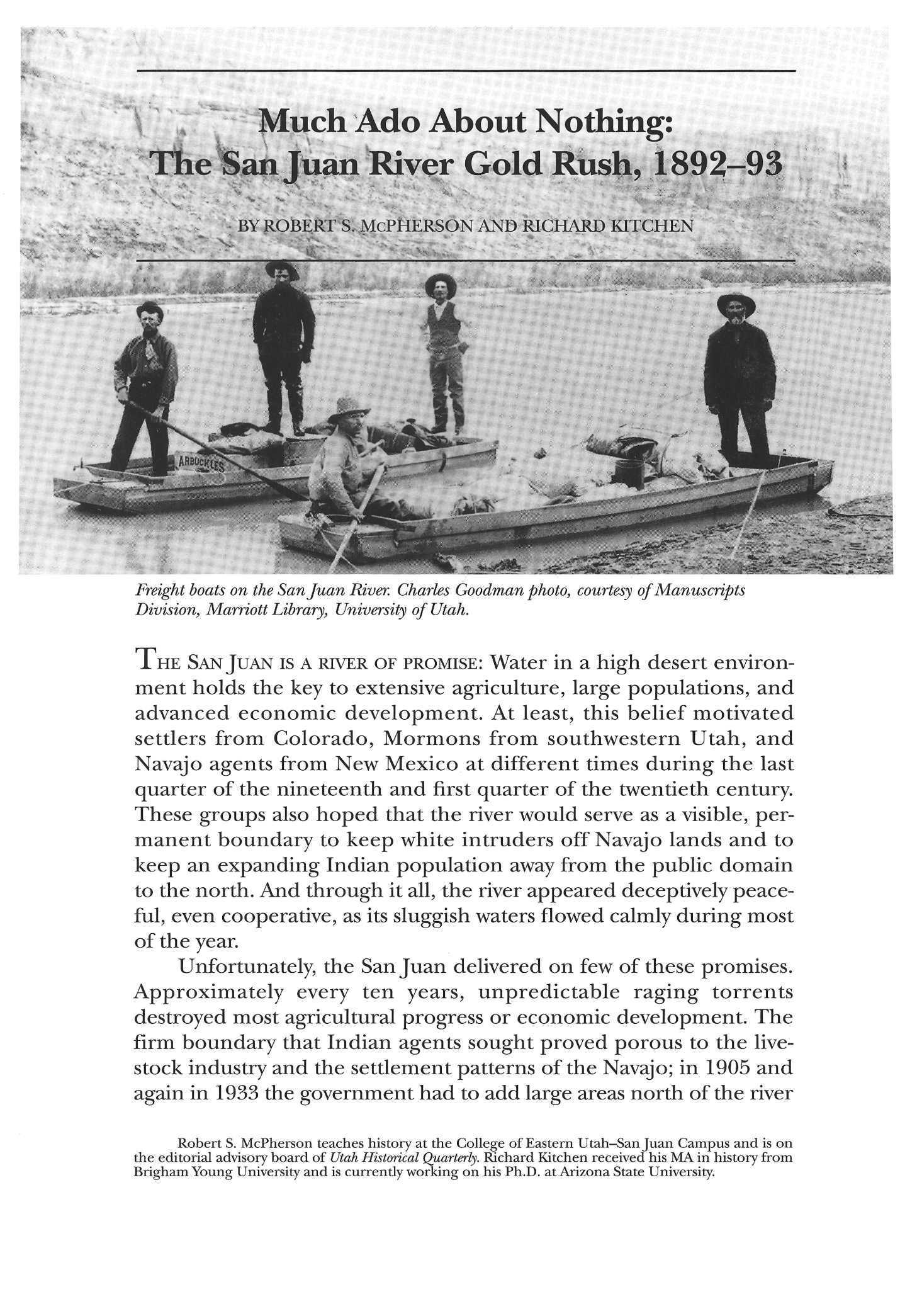

Top: Debrisfrom Manti flood of 1902, showing creek flume near center of town.

Bottom: Main Street, Manti, afterflood. Theflume was actually raisedfour feet by debris that was pushed under it.

Top: Debrisfrom Manti flood of 1902, showing creek flume near center of town.

Bottom: Main Street, Manti, afterflood. Theflume was actually raisedfour feet by debris that was pushed under it.

exhausted. ... It would be hard to find a seedling big enough to make a club and kill a snake."6

Potter also saw firsthand how overgrazing by sheep and cattle had damaged the vegetative cover of Utah's mountain watersheds. In the mountains surrounding Logan and the Cache Valley, he found areas "badly tramped out by sheep . . . [and] creek banks trampled down and barren of vegetation." Estimating that 150,000 sheep had grazed the area the previous year, Potter suggested that "the number allowed within the proposed forest reserve should not exceed 50,000." He encountered a similar scene in almost every area he visited, with the notable exception of the Uintah Indian Reservation. At the border of the reservation, Potter noted a marked change in the vegetative cover and general condition of the land He saw good grass and plenty of trees on the reservation, which demonstrated "the difference restriction of grazing makes in range conditions."7

He also recorded the opinions of a number of Utahns about the possibility of establishing forest reserves. At the time of Potter's survey, forestry officials pointed to the role of trees in protecting watersheds, arguing that preserving the forests would ensure a water supply for local communities. This argument did not convince everybody, however. Potter found that support for forest reserves varied according to geographic location; people in those areas that had not historically experienced a shortage of water or timber did not feel conservation practices necessary. Not surprisingly, he also discovered a great difference in support between those who held an economic interest in sheep or cattle and those who did not.8

While recording these general opinions toward conservation, Potter found that Utahns generally failed to correlate deteriorated watersheds with increased flooding and erosion. Citizens in Logan told him that they supported conservation because the large number of sheep and cattle posed a local health problem: "They think the health of the town is endangered by stock dying near the stream and by the pollution of the water by the manure and the urine

Denudation of the slope by timber cutting diminishing the water supply does not seem to alarm them."9

Several individuals, however, did grasp the relationship of over-

6 Potter, "Diary," 1, 5, 10

'Ibid., 3-5, 8-9, 13

8 Ibid.; Peterson, "Albert F Potter's Wasatch Survey," 249-53

9 Potter, "Diary," 2.

Utah Roods 27

grazing to increased flooding. Tom Smart of Logan informed Potter that "the most serious damage done by livestock has been packing the soil so that the water runs off in floods more than it did in former years." Professor G. L. Swendsen of the Utah State Agricultural College provided Potter with statistics on the Logan River showing that, since local deforestation and livestock damage to the range, "floods have come down earlier in the spring." Although Peter Thompson of Ephraim thought that tramping of the soil helped to increase the local water supply, he correctly admitted that denuded watersheds caused "the water to run down the canyons in place of soaking into the ground."10

Finally, the citizens of the town of Manti appeared to have learned a lesson from previous flooding Potter found that after the damaging floods in 1890 local citizens had excluded all stock from Manti Canyon in hope of restoring the vegetation. Manti citizens had elected L. R. Anderson mayor of the town in 1900 after he ran oh a "no more floods" platform; Anderson had then immediately petitioned President Theodore Roosevelt to set aside the Manti watershed as a forest reserve. This petition, along with the observations made during Potter's survey, led to the establishment of the Manti Forest Preserve on May 29, 1903. Complete prohibition of grazing in the Manti Creek watershed continued until 1909, and after that year federal grazing management continued the protection of the watershed.11

Potter's trip through Utah led directly to the establishment of most of the state's other national forests as well. Between 1903 and 1910 the Dixie, Wasatch, Ashley, and Cache forests all joined the Uinta and Fish Lake reserves, which had been established at the end of the nineteenth century. Forest officials immediately moved to restrict grazing on these new reserves; by 1910, they had reduced the number of sheep using Utah lands by almost one million, and numbers continued to fall over the next decade.12 This success in controlling grazing did help relieve some of the pressure on overgrazed watersheds, but forest officials failed to restore ground cover and to reduce erosion. It would take several decades and several devastating floods—floods created by poor watershed conditions—before officials

10 Ibid., 1, 9, 47

11 Ibid., 34; Salt Lake Tribune, June 8, 1953; Walter P Cottam, Is Utah Sahara Bound? Bulletin of the University of Utah, Vol 37, No 11 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1947), 7-9

12 Sheep far outnumbered cattle in Utah at the turn of the century. In 1900, there were almost four million sheep in the state, while the number of cattle remained around 350,000 Cattle actually experienced a slight rise in numbers in the first few decades of the twentieth century, peaking at a little over 500,000 in 1920 and then declining in the following years Cottam, Is Utah Sahara Bound?, 4

28 Utah Historical Quarterly

treated most of the state's watersheds with the same care exhibited by the citizens of Manti.13

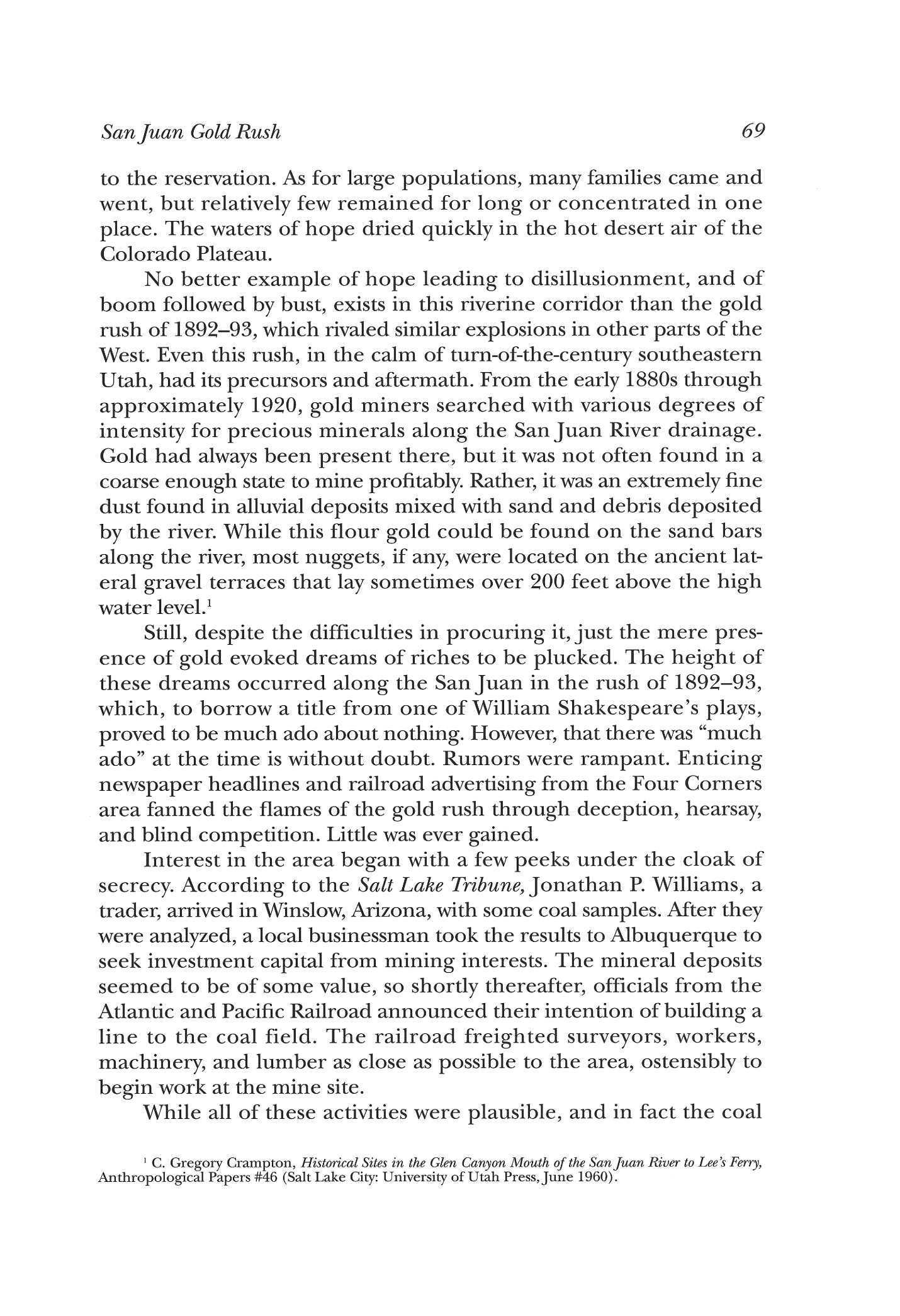

Floods were common in the first two decades of the twentieth century, although they were rather minor and isolated compared to the floods of 1862 On June 12, 1908, water overflowed on west North Temple Street in Salt Lake City, flooding the street and several homes. The following day, the Deseret News wrote that local citizens insisted "that the city is responsible for the conditions and must be forced to recognize their rights and prevent further flooding of the vicinity."14 People held the city responsible even though the News noted that railroad construction had caused the problem by cutting off a sewer connection that also served as a safety outlet for excess runoff. The city fixed the problem and public outcry dissipated, but as the size and

13 Charles S. Peterson, "Natural Resource Utilization," in Poll et at, Utah's History, 660-61.

14 Deseret News, June 13, 1908 In an interesting sidenote, the Salt Lake Tribune ran a story the same day that called the News coverage of this incident a "big canard." The Tribune noted that water had overflowed for only a distance of fifty feet and had caused "no trouble whatever." In response, the News called the Tribune an "organ of crooks." It seems that no topic was free from dispute in the frequent bickering between these two papers

29

Utah Floods

North Temple Street, 1907.

complexity of the city's sewer system increased, so would its problems and limitations in dealing with excess runoff.

During the first ten days of June 1909, high water from melting snow flooded areas along City Creek, the Jordan River, and around Utah Lake The heavy runoff turned City Creek into a "raging, frothy, yellow stream, full of debris from stumps of trees to boulders one foot in diameter The roaring of the stream can be heard from a distance of 150 feet from its banks."15 The creek roared down North Temple Street, and city workers built five-foot-high embankments along the street to contain the flow. South of the city, Parleys Creek flooded large tracts of farmland. The high runoff washed out bridges, damaged roads, drove people out of their homes, and drowned sixyear-old Matthew Desmond after he fell off a temporary bridge into the swirling waters of Mill Creek.16

Throughout Salt Lake City, channels, canals, and conduits exacerbated the flood problem. Residents had originally built these structures for irrigation, and the city had later expanded and maintained them in order to improve the water supply throughout the city These artificial water courses also served an additional function, helping channel excess water from the steep canyons east of the city to the Jordan River. However, when the water level rose above the capacity of such structures, they only served to complicate the problem.17

During the floods of 1909, a number of these artificial water

15 Salt Lake Tribune, June 5, 1909.

16 Deseret News,June 5 and 9, 1909; Salt Lake Tribune, June 6, 9, and 10, 1909

17

For more information on the construction of canals and conduits for water supply, see Fisher Stanford Harris, 100 Years of Water Development, Report Submitted to the Board of Directors of the Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake City, April 1942, Special Collections, Merrill Library

30 Utah Historical Quarterly

Utah Floods 31

courses filled with silt and debris and failed to function properly. The canal on 900 South filled so fast that it flooded the entire neighborhood in its vicinity On 1000 South, the canal on the north side of the street was able to channel excess water to theJordan River, but blockage in the canal on the south side was so bad that it caused the water to flow back on itself. This reverse flow, unable to travel very far uphill, soon cut a new channel straight through a number of backyards, giving homeowners riverfront property they were unaware that they had.18

This 1909 flooding brought renewed criticism of public officials. Writers and editors at the Deseret News sharply criticized public officials for their lack of foresight After a few members of the city council viewed the damage on June 5, a writer in the paper commented sardonically: "Of course they are all full of plans for the prevention of any similar trouble in the future—one such plan being the deepening and enlarging of the surplus canal. The flooded inhabitants are thus invited to forget this year's distress in the contemplation of next year's promise."19 The staff of the News also suggested that the authorities should "blow up" several dams that Salt Lake and Davis County officials had allowed gun clubs to build at the mouth of theJordan. These obstructions "set the water back, obstruct the flow, and materially aid in clogging up the channel of the river."20 The reactive nature of the city councilmen's promises—acting after the fact—and the lack of

18 Deseret News,June 5 and 9, 1909

19 Deseret News, June 5, 1909

20 Deseret News, June 9, 1909

The surplus canal referred to carried water from the Jordan River south and west of Salt Lake City directly to the Great Salt Lake, thus, designers hoped, helping to alleviate high water running through the heavily populated parts of the city

North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, 1907.

foresight on the part of county officials in allowing such development typify the relationship between humans and the flood problem in Utah.

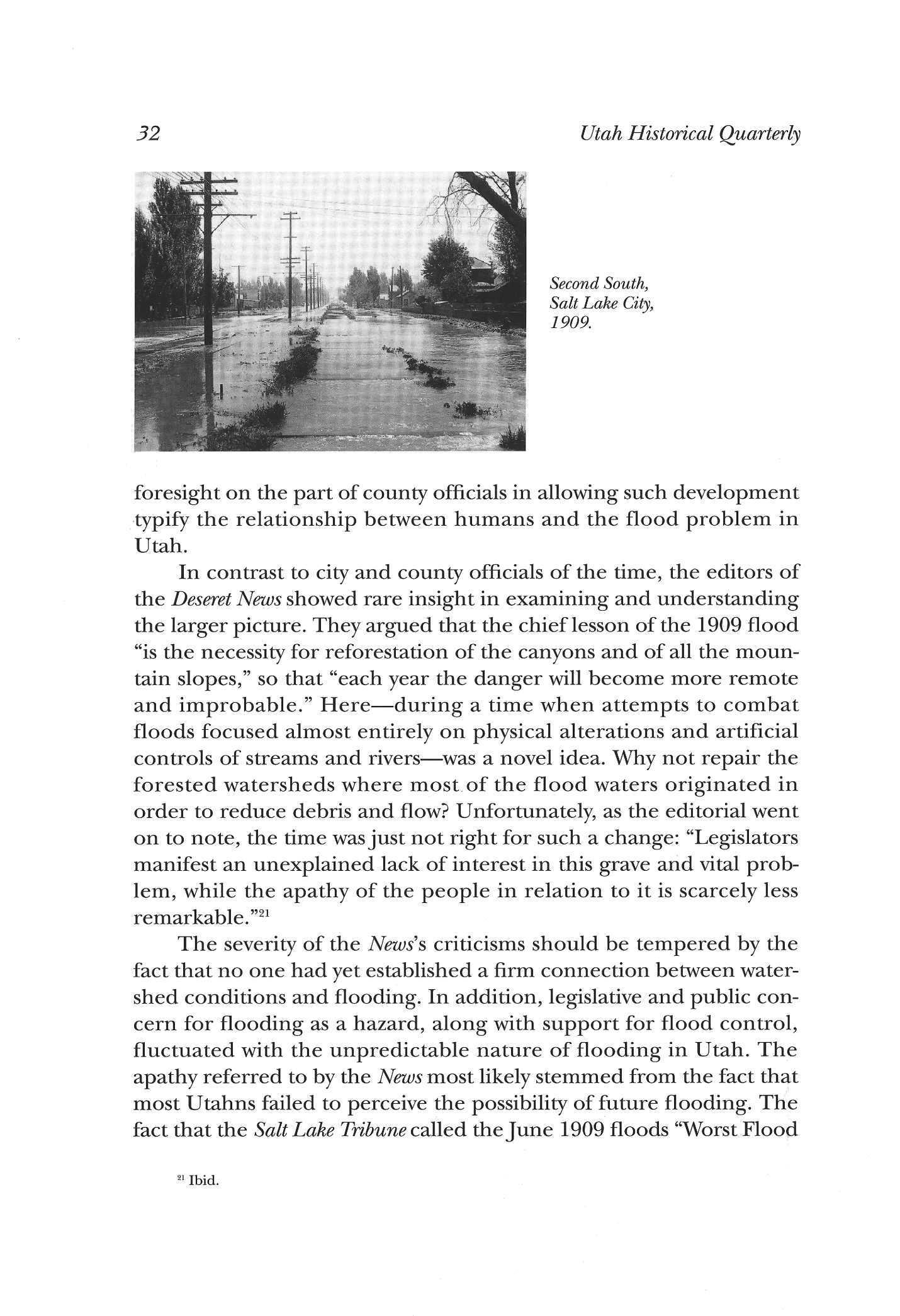

In contrast to city and county officials of the time, the editors of the Deseret News showed rare insight in examining and understanding the larger picture They argued that the chief lesson of the 1909 flood "is the necessity for reforestation of the canyons and of all the mountain slopes," so that "each year the danger will become more remote and improbable." Here—during a time when attempts to combat floods focused almost entirely on physical alterations and artificial controls of streams and rivers—was a novel idea. Why not repair the forested watersheds where most of the flood waters originated in order to reduce debris and flow? Unfortunately, as the editorial went on to note, the time wasjust not right for such a change: "Legislators manifest an unexplained lack of interest in this grave and vital problem, while the apathy of the people in relation to it is scarcely less remarkable."21

The severity of the News's criticisms should be tempered by the fact that no one had yet established a firm connection between watershed conditions and flooding. In addition, legislative and public concern for flooding as a hazard, along with support for flood control, fluctuated with the unpredictable nature of flooding in Utah. The apathy referred to by the News most likely stemmed from the fact that most Utahns failed to perceive the possibility of future flooding. The fact that the Salt Lake Tribune called theJune 1909 floods "Worst Flood

32 Utah Historical Quarterly

Second South, Salt Lake City, 1909.

21 Ibid.

in History of Zion" implied a forgetfulness—or ignorance—regarding the floods of 1862.22

Flooding two months later in the vicinity of Manti seemed to prove the News editorial's points regarding reforestation In August 1909, heavy rains caused flooding "in adjacent canyons to both the north and south of Manti Canyon, while the latter was not perceptibly affected."23 Local citizens, of course, had protected Manti Canyon from all grazing since the 1890 flood, and the inclusion of the area in the Manti-LaSal forest reserve in the first decade of the twentieth century helped continue the program of protection. Although it appeared that restriction of grazing had paid off in this localized case, a widespread effort to restore Utah's watersheds remained more than twenty years away

In 1917, Salt Lake City officials decided to end their flood problems once and for all. They diverted City Creek, which had long been a flood hazard, into an underground conduit designed to carry flows from the mouth of City Creek Canyon to the Jordan River at North Temple Street. The diversion of City Creek followed other projects completed earlier: Red Butte Creek, which entered an underground conduit at the junction of 1100 South and 1200 East; Emigration Creek, which entered a conduit near Westminster College; and Parleys Creek, which entered an underground conduit that extended northwesterly to intersect the combined Red Butte-Emigration conduit near State Street on 1300 South. From there, a conduit along 1300 South carried the combined flow into the Jordan River. Officials designed all of these underground diversions to carry runoff and excess flows directly to the Jordan River without traveling—at least above ground—through the heart of the city All of these diversions opened new land for development and functioned adequately during years of normal high water.

However, flooding during the same year that officials diverted City Creek into an underground channel illuminated the inherent problems of these conduit systems.24 On April 25 and 26, 1917, heavy rainstorms

22 Salt Lake Tribune, June 5, 1909 For more on perception and flooding see Robert William Kates, Hazard and Choice Perception in Hood Plain Management (Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Geography, 1964), 104-34, and Gilbert F White, Choice of Adjustment to Floods (Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Geography, 1964), 1-41 For a discussion of perception and hazards in general, see Charles Perrow, Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies (New York: Basic Books, 1984)

23 C L Forsling, A Study of the Influence ofHerbaceous Plant Cover on Surface Runoff and SoilErosion in Relation to Grazing on the Wasatch Plateau in Utah, United States Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin No 220 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1931), 8