UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN S. ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

AUDREY M. GODFREY, Logan, 2000

LEE ANN KREUTZER, Torrey, 2000

ROBERT S. MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2001

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Murray, 2000

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

RICHARD C. ROBERTS, Ogden, 2001

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 1999

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1999

RICHARD S. VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 2001

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25,00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 3/4 inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

UTAH

STATE HISTORICAL! SOCIETY !

HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y Contents SPRING 1999 \ VOLUME 67 \ NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 99 SCHOOL DAYSAND SCHOOLMARMS DAVID A HALES 100 GOING TO THE MOVIES: A PHOTO ESSAY OF THEATERS ROGER ROPER 111 REUBEN G MILLER: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY RANCHER, ENTREPRENEUR, AND CIVIC LEADER . . .EDWARD A. GEARY 123 CATTLE, COTTON, AND CONFLICT: THE POSSESSION AND DISPOSSESSION OF HEBRON, UTAH W. PAUL REEVE 148 IN MEMORIAM: LEONARDJ ARRINGTON, 1917-1999 DAVIS BITTON 176 BOOKREVIEWS 181 BOOKNOTICES 192 THE COVER Rialto Theater, Salt Lake City, 1941. © Copyright 1999 Utah State Historical Society

JESSIE L. EMBRY "In HisOwnLanguage": MormonSpanish-Speaking Congregations inthe United States LAMOND TULLIS 181

FORREST G. ROBINSON, ed. The New Western History: The Territory Ahead W. PAUL REEVE 182

RICHARD PATTERSON. ButchCassidy: A Biography E. LEO LYMAN 183

SHAWN HALL. Old Heartof Nevada: Ghost Towns and MiningCamps ofElko County .STEPHEN L CARR 185

SCOTT B. VICKERS NativeAmerican Identities: From Stereotype to Archetype in Artand

Literature ERIKM . ZISSU 187

LEONARDJ. ARRINGTON. Adventuresof a Church Historian. .WILLIAM MULDER 188

CHARLES WALLACE MILLER, JR The Automobile Gold Rushesand Depression Era Mining .PHILIP F NOTARIANNI 190

Books reviewed

In this issue

For readers of history, a certain poignancy lies in the ability to know the conclusion of a story—to see how hopes and expectations play out in the end. Beginnings, of course, carry a certain charged energy. Witness these beginnings: In 1862 a group of devout St. George settlers, assigned to raise cattle for the Cotton Mission, move forty miles north to establish a new community; a generation later, a young cowboy sets out to build a livestock empire in the Price area; during the depression in southern Idaho, a young man plans a lifework of poultry raising; four young women leave their smalltown homes to earn teaching degrees at Snow College

But events never seem to unfold in ways that, during those hope-filled beginnings, can be guessed. The students at Snow College, for example, had expectations for the future as they both worked and romped through a year away from home; however, changing cultural conditions would alter the trajectories of these women's lives. Reuben G. Miller, the young cowman in Price, probably saw only success ahead as he grew to become the region's most prominent stockman and businessman; he, too, could not have guessed how his fortunes would change. As the Cotton Mission settlers put their faith and energy into building a community, they did not forsee that their hamlet of Hebron could not survive And finally, the would-be poultry farmer, Leonard Arrington, could never have imagined that he would become Utah's most-honored historian.

History's retrospective view links these beginnings and endings. By exploring the territory in between, the articles in this issue illuminate the whys and hows of unfolding events. In addition to the above-mentioned stories of labor and lifework, a photo essay on movie theaters shows how entertainment, like everything else, has evolved in previously unimaginable ways Together, this issue's articles and the memorial tribute to Society Fellow Arrington offer perspectives that cannot be had at the beginning of any endeavor.

'iMMJ::

Cows crossing the Virgin River. USHS collections.

School Days and Schoolmarms

BY DAVID A HALES

DURIN G THE DEPRESSION YEARS, four young women left their homes in Oak City, Utah, to attend Snow College. In doing so, Helen Shipley, Sadie Lovell, Blanche Nielson, and Lucile Roper1 were taking a step that was both adventurous and conventional: While most of their friends married right after high school, these young women decided to leave familiar surroundings in order to prepare for careers. With few alternatives available, however, they chose to pursue a traditional female occupation. As Lucile later recalled, "Aunt Jane and Mabel [Lucile's sister] tried to get me to follow in their footsteps and become a nurse I was not interested in nursing As a child I loved to play school and I decided I wanted to become a school teacher."2 Teaching also attracted the other three women.

Lucile, oldest of the four, left home first. After graduating from Delta High School in 1929, she spent a busy summer helping her father care for the family's large truck garden and orchard at their home in Oak City, a few miles east of Delta. Although even before the depression the Roper finances were meager, the family managed to accumulate enough funds to send their daughter to college

Lucile truly wanted to become a teacher, but it was difficult for her to leave home for the first time. Although she had the reputation of being the "life of the party," she was actually shy Besides, as the

David A Hales is Director of the Library at Westminster College, Salt Lake City

1 Lucile, the author's mother, carried the full name of Rachel Lucile Roper The women's married names were Helen S. Anderson, Sadie L. Christensen, Blanche N. Crafts, and Lucile R. Hales.

2 Lucile Roper Hales interview by author, Deseret, Utah, June 1989 Lucile also wrote a detailed life history, and it is mainly through her perspective that the story unfolds

School Days and Schoolmarms101

youngest daughter of a close-knit family of eleven, she had always been sheltered and protected by her older brothers and sisters.

Lucile joined her cousins Glenn and Lynette Rawlinson at Snow College, and the three rented a pair of upstairs rooms from Orval Peterson. Glenn slept in the kitchen/living area while the two girls shared the bedroom. Other students also rented rooms in the Peterson home, heating and cooking with a wood stove and using an outhouse with accommodations for two (affectionately known as a two-holer). The students bathed in an old round galvanized tub.

Lucile wrote, "I surely got homesick that year and didn't enjoy it much. Lynette was always running off to play [piano] for people, so I never got help or companionship from her. Glenn was real good and helped me out a lot."3

At that time, students at Snow College could earn an associate degree in education in two years by completing ninety-six hours of credit Among the required courses were religion, handwriting, health education, educational psychology, curriculum, organization and administration, and practice teaching. In addition to maintaining a B average, students were expected to "be free from habits of using tobacco or intoxicating liquor, and be able, otherwise, to give evidence of good character."

Tuition for three quarters was $50, which included a studentbody fee admitting the student to all regular lyceum numbers, dances, sporting events, and entertainments; it also included a subscription to

Opposite page: Lucile Roper and Blanche Nielson. This page: Helen Shipley and Sadie Lovell. From Snowonian, 1931. All photos courtesy of the author.

3 Lucile Hales, life history notes (original copy in possession of Rawlene Hales Hansen, Washington, Utah; pagination by author), 20-21

3 Lucile Hales, life history notes (original copy in possession of Rawlene Hales Hansen, Washington, Utah; pagination by author), 20-21

the college newspaper, SnowDrift. The Snowonian, the annual yearbook, cost $2.50 Two-year graduates received a Utah State First Class Certificate permitting them to teach in Utah's elementary schools for five years without further examination.4

Lucile was confident that she would be able to find a position once she completed the program. She was also quite sure she would find a position in Millard County since she knew several young women who planned to resign in order to marry. As Miriam Murphy has recorded, "Besides their generally lower pay, women teachers were saddled with another handicap that cut short their careers and effectively kept them from working toward higher-paying supervisory positions Most school districts fired women teachers who married."5

After a year of homesickness

Lucile returned home the next summer to help her father. In the fall of 1930, her hometown friends Blanche, Helen, and Sadie convinced her to return to Snow College and room with them. At this time the Roper family was able to gather the necessary funds even though, as Lucile recalls, "We were still having hard times Father sold a calf for about $2.00."6

Lucile's parents were only able to send her $5.00 each month to meet her expenses; since her share of the rent and electricity was $2.50, her budget was very tight, but it was comparable to that of other students The college catalogue reported: "The cost of living in Ephraim is much lower than in the large cities of the state. Good room and board in a private house can be obtained at from $5.00 to $7.50 per week. Nonresident students can reduce their expenses by renting rooms and boarding themselves. Rent is from $2.00 and up per room per month."7

102Utah HistoricalQuarterly

•• • Sadie (left) and Blanche (right) on washday. From Snowonian, 1931.

4 Thirteenth Annual Announcement of Snow College, 1929-1930 (Ephraim: Snow College, 1929), 31, 32,36,27

5 Hales interview; Miriam B Murphy, "Women in the Utah Work Force from Statehood to World War II," in John S McCormick and Joh n R Sillito, eds., A World We Thought We Knew: Readings in Utah History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995), 189-90

6 Hales life history, 24

7 Annual Announcement of Snow College, 27, 28

The young women chose to "reduce their expenses" by renting two front rooms in the home of Peter Hansen and bringing all their food with them from home. One room was used as the kitchen/living room and the other as the bedroom "We had to go outside to the twoholer and some times it was pretty cold," wrote Lucile.8

Blanche recalled, "I remember my Dad dropped me and a hundred-pound bag of flour off at school. We took all our food from homecanned fruit and vegetables We ate what our families were eating at home. If they killed a beef we got some; if they killed chicken we got some, too. During the year they would send us food packages through the U.S mail We also ate lots of bread and sardines. Canned sardines were very cheap in those days. We would have starved otherwise." Lucile confirmed, "We had to take a good supply of food because we could get home only at Christmas and at the end of the year. The old man [Hansen] let us put our food storage down in his cellar."9

Helen remembers that, although she was a farm girl, she had never liked sweet corn. However, because Mr. Hansen let the girls pick all the corn they wanted from his garden, that changed: "I learned to like corn just to have some variety." Lucile remembered, "We would take turns making the bread and running home, which was a block from the college, to bake our bread Sometimes it would be well cooked."10

Wash day was a major chore for the students The girls had to heat water on the stove then wash the clothes with a scrubbing board in a number 3 metal tub. In winter, they had to hang their laundry in the kitchen, creating a small obstacle course.

L1 • 103

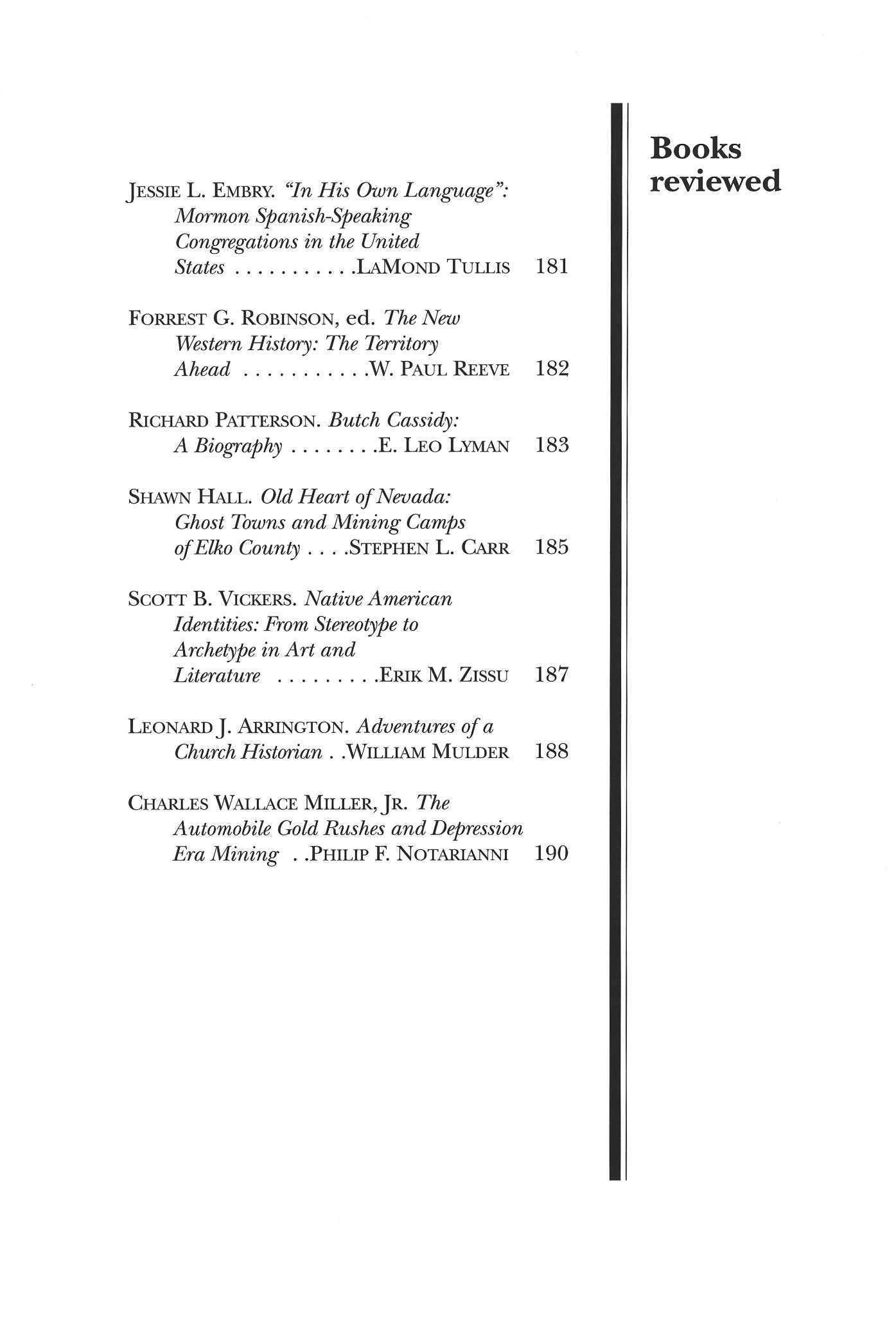

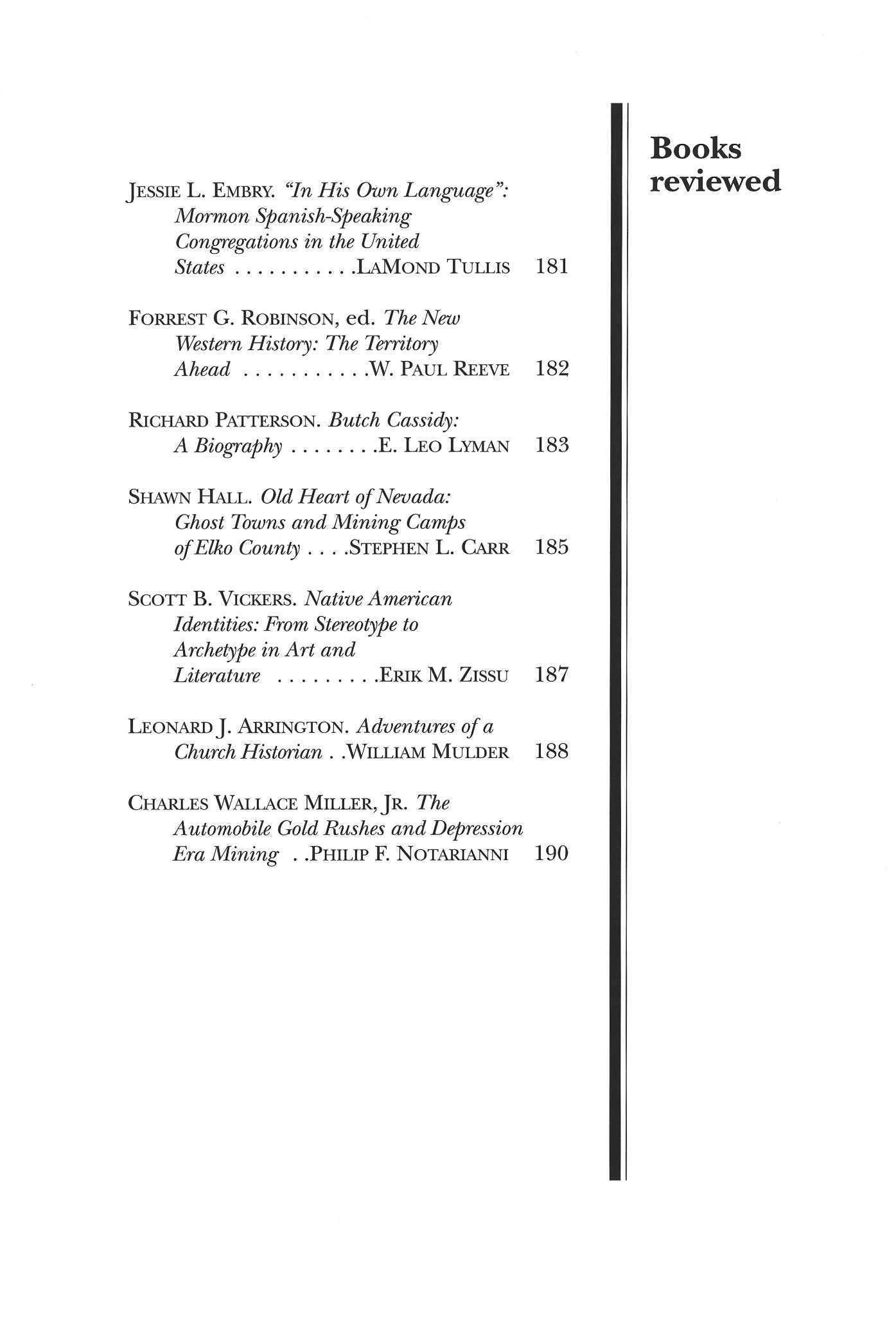

Mock wedding, one of the coeds' favorite games. The "bride " is Lulu Jensen and the "groom " is Lucile Roper.

8 Hales life history, 24

9 Blanche Nielson Crafts and Lucile Roper Hales interview with author, Hinckley, Utah, June 1989; Hales life history, 25 10 Helen Shipley Anderson interview with author, Oak City, Utah, August 1997; Hales life history, 25.

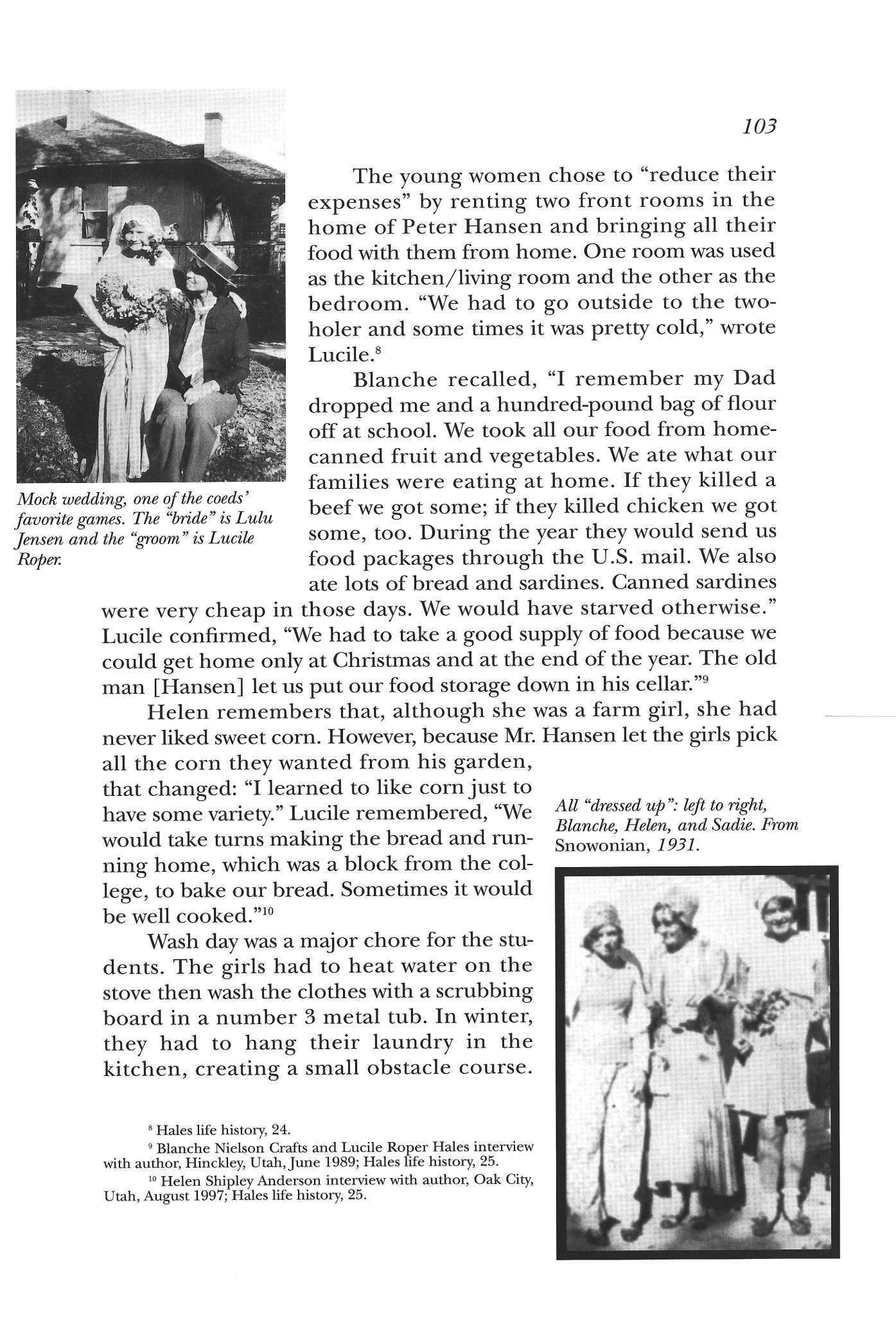

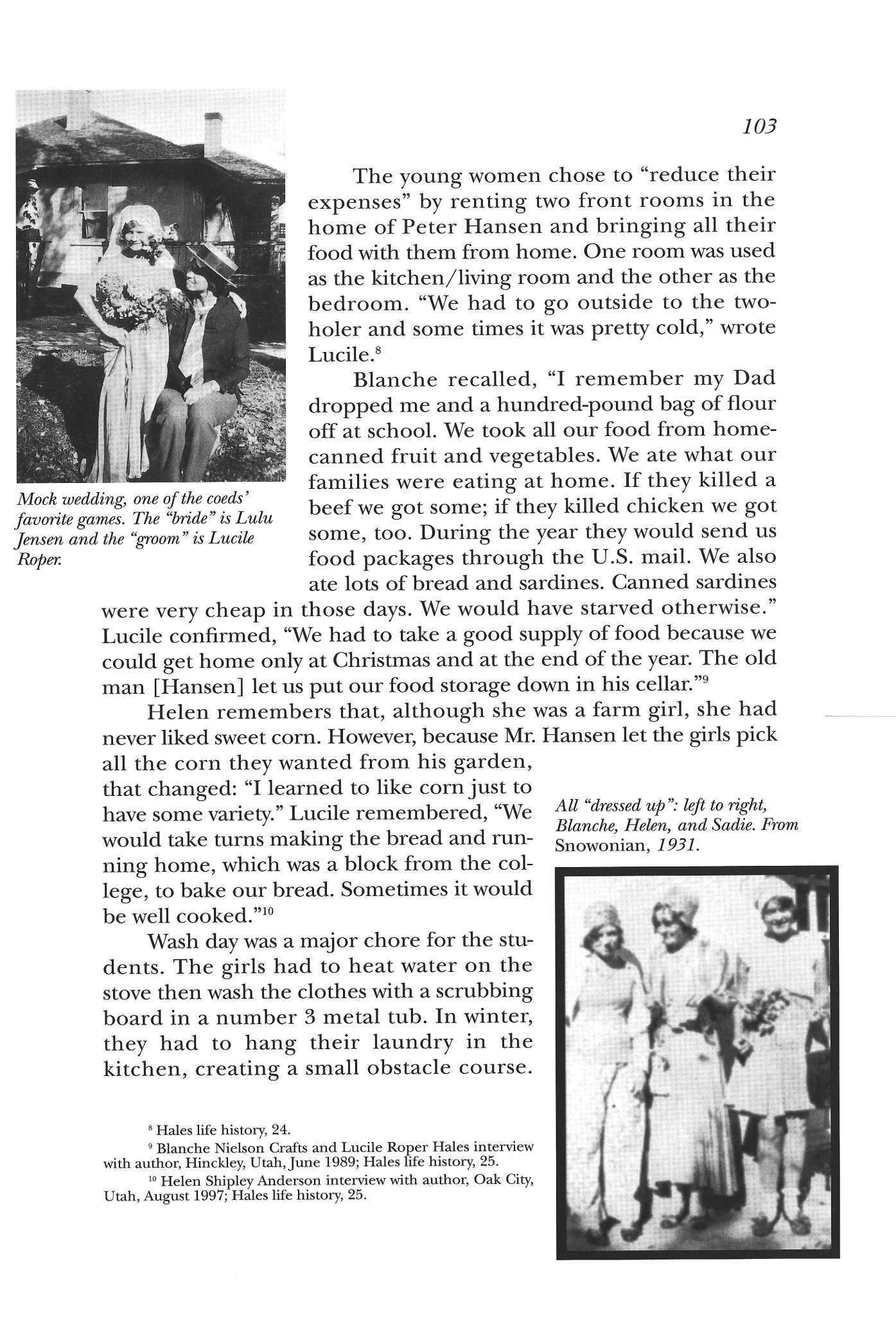

All "dressed up": left to right, Blanche, Helen, and Sadie. From Snowonian, 1931.

Lucile's wardrobe was typical for the time. She had one pair of shoes, two every-day dresses, a blouse and skirt, and a Sunday dress. For Easter one year she was excited to receive a new dress from her sisters. Blanche and Helen had similar wardrobes, but they did own two pairs of shoes each.11

Naturally, the coeds anxiously awaited care packages from home. One day they received a large box in the mail. Excited and expecting to receive some special items from their families, they opened it "But to our sad plight," reported Lucile, "[we] found an old dead crow. We were a sad bunch of hungry girls. We didn't know whether to laugh or cry." The girls blamed the hoax on some "fellows" who had been coming to the house. But when, several days later, Ned Armstrong came by with a hefty fish he had caught at Fish Lake, the girls overlooked the prank. "Boy, was it ever good," Lucille wrote.12

Fellows had been showing up at the house since the beginning. The first night the young women were in Ephraim, some local boys dropped by to meet the new arrivals The young men, who had been drinking, insisted that the girls go out on the town with them and became obnoxious when the girls refused. Finally, Lucile told them that she was the mother of the family and that her daughters could not go out. After that, everyone called Lucile "Ma." Blanche, the small-

Above: TheJorgensen home, where the girls were often invited for dinner. Top left: Astrid Jorgensen, friend and schoolmate. Left: Astrid's mother Alma, who often served home-cooked meals to the coeds.

Helen Shipley Anderson interview; Crafts and Hales interview Hales life history, 25

est of the girls, acquired the nickname "Buzz." On campus, the entire Oak City group became known as "Hansen's little pigs" because their landlord raised and sold pigs. The girls detested the nickname.13

Although on that first night "Ma" had sent the unruly young men packing, Hansen's house soon became a popular place for boys Late one evening Mr. Hansen appeared at the door in his nightshirt and cap, holding a candle; he told the boys it was time for them to leave. Lucile wrote, "The boys left in a hurry, but it did not stop them from coming back." Hansen apparently reported the late-night activities to the college, though, because the administration called Lucile in and told her she needed to see that there was more studying and less play at her residence. She spoke to her roommates, and the situation improved.14

Still, "We hardly ever spent a weekend without doing some crazy thing," Lucile wrote. For one thing, the Oak City coeds and their friends liked to put on mock weddings. One would dress as the groom, another as the bride, and the rest as bridesmaids and other members of the wedding party. And at homecoming, "not any of us went to the dance, but stayed home and goofed off. Lula [Jensen] and I dressed up silly and the rest bet we wouldn't dare go in those clothes up to the bakery on Main Street and get some candy Well, we took them up on it and went. Of course, we went sneaking through the lot,

105

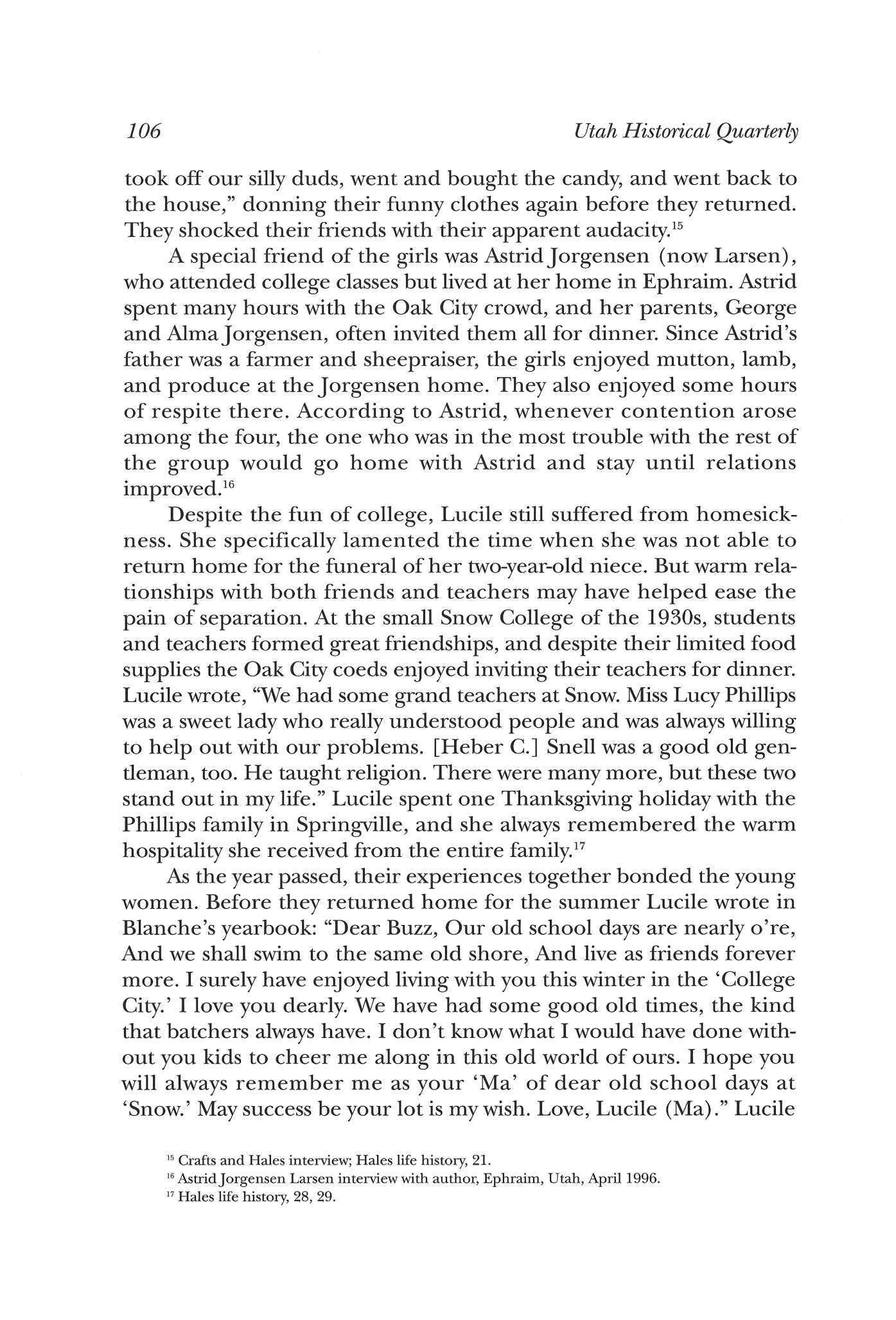

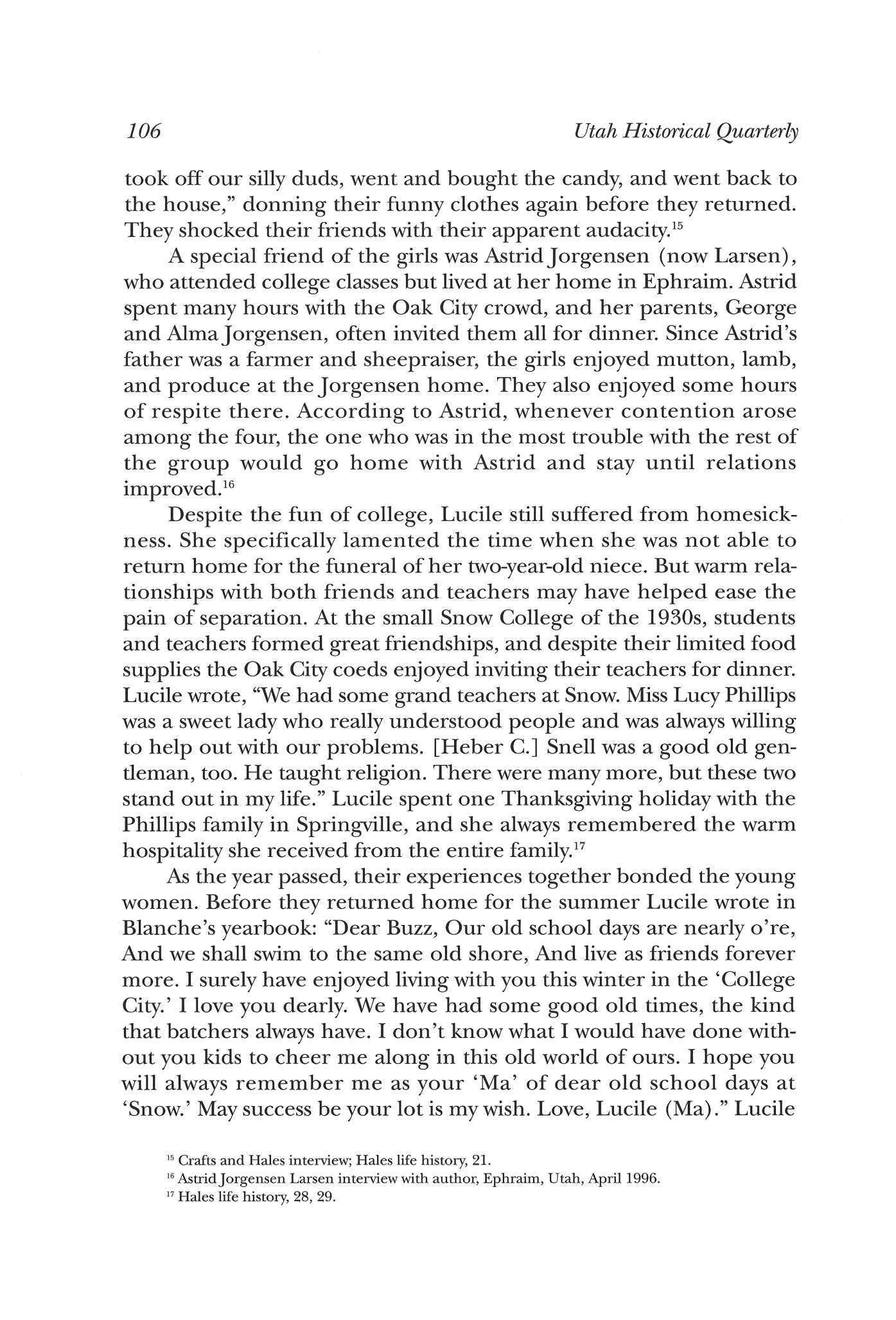

Snow College Building, 1931; teachers Lucy Phillips and Heber C. Snell. From Snowonian, 1931.

Ibid Ibid., 26-27

took off our silly duds, went and bought the candy, and went back to the house," donning their funny clothes again before they returned. They shocked their friends with their apparent audacity.15

A special friend of the girls was Astrid Jorgensen (now Larsen), who attended college classes but lived at her home in Ephraim. Astrid spent many hours with the Oak City crowd, and her parents, George and AlmaJorgensen, often invited them all for dinner. Since Astrid's father was a farmer and sheepraiser, the girls enjoyed mutton, lamb, and produce at the Jorgensen home. They also enjoyed some hours of respite there According to Astrid, whenever contention arose among the four, the one who was in the most trouble with the rest of the group would go home with Astrid and stay until relations improved.16

Despite the fun of college, Lucile still suffered from homesickness. She specifically lamented the time when she was not able to return home for the funeral of her two-year-old niece But warm relationships with both friends and teachers may have helped ease the pain of separation At the small Snow College of the 1930s, students and teachers formed great friendships, and despite their limited food supplies the Oak City coeds enjoyed inviting their teachers for dinner. Lucile wrote, "We had some grand teachers at Snow. Miss Lucy Phillips was a sweet lady who really understood people and was always willing to help out with our problems. [Heber C] Snell was a good old gentieman, too. He taught religion. There were many more, but these two stand out in my life." Lucile spent one Thanksgiving holiday with the Phillips family in Springville, and she always remembered the warm hospitality she received from the entire family.17

As the year passed, their experiences together bonded the young women. Before they returned home for the summer Lucile wrote in Blanche's yearbook: "Dear Buzz, Our old school days are nearly o're, And we shall swim to the same old shore, And live as friends forever more I surely have enjoyed living with you this winter in the 'College City.' I love you dearly. We have had some good old times, the kind that batchers always have. I don't know what I would have done without you kids to cheer me along in this old world of ours. I hope you will always remember me as your 'Ma' of dear old school days at 'Snow.' May success be your lot is my wish. Love, Lucile (Ma)." Lucile

15 Crafts and Hales interview; Hales life history, 21

16 Astrid Jorgensen Larsen interview with author, Ephraim, Utah, April 1996

17 Hales life history, 28, 29

106Utah Historical Quarterly

and Blanche had played together as young girls herding cattle on the banks of the irrigation ditches in Oak City Helen had also been a friend since childhood, and these three women remained close throughout their lives.18

Although she had not completed her student teaching, Lucile graduated in the spring of 1931. Since students did not have money for the traditional caps and gowns, the young men wore suits and the young women their best dresses. "My graduation dress was light blue with ruffles going from the front to the back," Lucile wrote.19

That summer Lucile worked for her sister Mabel, a nurse who ran Delta Hospital for Dr. M. E. Bird. In the fall, she completed her student teaching at Ephraim. Although she had been confident that she could find ajob, when Lucile finished in December she was not able to find a single teaching position. However, she did learn from Dr Bird that the government was looking for teachers who would establish kindergartens. She inquired and received permission to start one in Oak City "Each parent who wanted their children in the school had to pay ten cents per child and the government would pay the rest. So that's how I got started teaching." With very few supplies available, Lucile relied on her ingenuity: "I got along well with the Sears and Roebuck Catalog and the Montgomery Ward Catalog for the kids to learn to cut out."20

When Lucile learned that one of the teachers in Oak City was getting married, she went to see Clead Nielson, a school board member, and he helped her get ajob teaching third, fourth, and fifth grades. She enjoyed that first year of teaching. "Edith [Stevens] and I spent many hours in the evenings, (especially around Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter) decorating our rooms." Lucile lived with her parents, paying $20 per month for board and room, which helped her brother Rawlin attend school at BYU.21 Her time at Oak City was to be short, however. "The next summer we were in the canyon to a program and Dad heard a man talking to the Superintendent about me. He said I favored my own relatives too much. When our assignments [for the new school year] came out I was assigned to A.C. Nelson School at Deseret." In Deseret, Lucile

18

19 Hales life history, 27

20 Ibid., 30

21 Ibid., 31

School Days andSchoolmarms107

Snowownian, 1931, original in possession of Ralph Crafts, Hinckley, Utah Lucile and Blanche married men who were cousins to each other, and for the rest of their lives the two families lived only three miles apart

taught third and fourth grades and lived in an old schoolhouse owned by Mr. and Mrs. Louis Schoenberger, a couple who had boarded teachers for many years. At this point Lucile was earning $75 per month and paying $25 for room and board, which included a lunch to take to school. "I was envied by many. People just couldn't believe a single woman would have $50just for herself."22

For three years Lucile taught at A. C. Nelson School, attended Brigham Young University during the summers, and continued to provide financial support to Rawlin, who graduated in 1935 with a teaching certificate. After teaching his first year in Millard County, Rawlin was eager to go to Carbon County, where pay was higher. He learned that there was a vacancy for a teaching couple in Wattis, with housing provided, and he convinced his sister to go with him after the superintendent agreed to hire the brother/sister team. Lucile wrote, "It was quite a raise too, from $85.00 per month to $175.00 per month."23 However, when the two arrived in Price, they learned that the position had been given to a husband and wife. Instead, the district offered the Ropers teaching positions in Consumers and Gordon Creek.

During her first year in Carbon County, Lucile was severely injured in an automobile accident and required several months of recuperation at the family home in Oak City By the end of her second year teaching there, she was engaged to marry Albert (Bert) Hales, whom she had first met while she was teaching in Deseret. Lucile recorded, "I did want to teach one more year, but Bert said, 'now or never,' so I decided it better be now." When they married on June 28, 1940, Lucile surmised that her teaching career had ended.24

She was the last of the four roommates to marry. Sadie married Anthony Christensen in 1931 after her first year at college. She wanted to continue her schooling, but her husband was a teacher and said, "One schoolteacher in the family is enough." He and Sadie settled in Aurora, Utah, where they farmed and raised a family; she never completed her college studies.25

Blanche and Helen both graduated in the spring of 1932. Helen taught school for one year then married Harold Anderson. She never returned to teaching. Blanche taught for one year in Deseret and two

22 Ibid., 31-32; Hales interview

23 Hales life history, 40

24 Ibid., 47

26 Sadie L Christensen telephone interview by author, February 1990

108Utah Historical Quarterly

years in Lynndyl. When she married Ralph Crafts onjuly 1, 1937, she too assumed that her teaching career was over

However, World War II changed the status of married women in rural classrooms. Many young men who had fought in World War II either lost their lives (as was the case with Lucile's brother, Rawlin)26 or moved to larger metropolitan areas when they did return. Also, many young women had gone to live and work in cities during the war and chose to stay there afterward. The resulting demographic shift caused a teacher shortage in many small rural areas.

In 1947, although they had not taught for many years and were not certified teachers, Lucile and Blanche were contacted by Hinckley High School principal Kenneth Robins, who persuaded them to teach at Hinckley Elementary School. The school administration was so desperate that the superintendent agreed to provide transportation for both Lucile and her babysitter. Each weekday morning Lucille Cahoon, the babysitter, would board the school bus in front of her home in Oasis and ride to the Hales residence in Deseret. There she would get off the bus, and Lucile would get on and travel to school with the students After school the bus routine was reversed.27

Blanche taught until December, when she and her husband had the opportunity to adopt a baby boy. Lucile had become pregnant, but she was able to finish the year because her pregnancy was not obvious.

"Mrs. [Fannie Lee] Hilton was surprised when I told her I was pregnant. She said, f just thought you were getting pleasantly plump.' She told the Superintendent and he said to let me go on teaching if I felt like it." School ended on May 31, 1948, and Lucile gave birth to a baby boyjust a week later With a new baby and two other children at home, Lucile decided not to return to the classroom in the fall.28

Both Blanche and Lucile spent the next years raising their families. By 1960, however, expanding economic opportunities in fields other than education created new demands for teachers. That year Blanche returned to the classroom, teaching at Delta Elementary, and Lucile began teaching kindergarten at the Sutherland Elementary The two were hired because of their experience but with the understanding that they would acquire the current credential, a bachelor's degree in education. Blanche and Lucile, now in their late 40s and

School Days andSchoolmarms109

26 Hugh Rawlin Roper enlisted in April 1941 He became a pilot and was killed when his plane collided with another plane during their return from bombing the Ploesti oil fields in Romania on August 1, 1943

27 Hales life history, 64

28 Ibid., 64, 65

early 50s, were not typical coeds anymore, but they took correspondence courses and went to summer school year after year until they finally graduated from the College of Southern Utah in June of 1966.

Lucile taught until 1974 and Blanche until 1977, ending careers that each exceeded twenty years and spread across five decades. During this time, the two women saw many changes. They themselves had become harbingers of change as they, like many other young women, left the comforts of home with plans to pursue an education and return to their communities to teach They became role models, both for other women and for the children of rural Utah. Lucile provided hundreds of Utah children with their first introduction to reading, and Blanche was responsible for acquiring a grant and establishing the first media center in any Utah school.

The careers of the two were significantly affected by events and laws of the time. They entered the teaching profession in the 1930s confident that they would be able to find jobs, since most women were not allowed to teach once they married. In the late 1940s, years after they had married and left the profession, school officials begged them to return—although they were not certified to teach—because of the teacher shortage caused by the war. They left teaching to raise their families but re-entered the profession during the 1960s when a booming economy again caused a shortage of teachers. After years struggling to juggle families, jobs, and education, and after they had produced a legacy of quality job performance, these same women were forced to leave the careers to which they had devoted much of their lives, talents, and energies Ironically, it was not their choice to retire; instead, the mandatory retirement law abruptly ended their careers.

Toward the end of their lives, both women agreed that their greatest rewards had come from their experiences in teaching and raising families. Yet they still looked back fondly on those memorable days as students themselves, sharing hard times and sardine sandwiches at Snow College during the Great Depression

HOUtah HistoricalQuarterly

Going to the Movies: A Photo Essay of Theaters

BY ROGER ROPER

MOVIE S ARE A 20™-CENTURY phenomenon, and movie theaters are a distinct type of 20th-century architecture. Though descended from opera houses and playhouses of an earlier era, movie theaters quickly developed characteristics of their own. The first theater designed specifically for motion pictures opened in 1902 in Pennsylvania, and by 1905 most large cities in America had one

The evolution of theater design in Utah paralleled national trends. The flamboyant, exaggerated architecture of movie palaces—including regal Neoclassical designs, exotic Egyptian and Spanish Colonial revivals, or daring Art Deco and Art Moderne styles—set them apart from their more mundane neighbors on Main Street And if this "pay attention to me" styling was not enough to capture the public eye, projecting marquees bedazzled with lights ensured attention. Other notable features included sidewalkaccessible ticket booths, concession stands, and stage-less auditoriums.

Roger Roper is the preservation coordinator for the Utah State Historical Society Unless otherwise noted, all photos are from USHS collections Footnotes are on p 122

The Beaux Arts-style Casino (Star) Theater on Gunnison's Main Street is the most elaborate smalltown theater in Utah and one of the state's first buildings constructed specifically for movies. The commercial spacesflanking the entrance generated additional revenue. When this elegant, modern theater opened inJanuary 1913, the local newspaper noted that "patrons will need a little time to break off old custom, " and offered them thefollowing bits of advice: "Read to yourself. the explaining sentences thrown on the screen and don't annoy, by reading aloud, others who can readfor themselves "; "When you are required to make roomfor another person to pass by, just tip back the seat you occupy "; and "When you leave, go; don't make a church handshake time of it. "l

Movie theaters were usually the showiest buildings in the downtown area. That was true in larger cities as well as small towns. The 1912-13 Renaissance Revival-style Capitol Theater in Salt Lake City (1947 photo), designed by an out-of-state architect, features Palladianmotif upper windows, diamond-pattern brickwork, and a heavily decoratedfrieze and cornice. Though originally built for vaudeville, the theater was remodeled in 1927 to become "the city's leading moving picture palace. " The theater sign arching over 2nd South a distinction afforded no other building in the city— provided further visibility.

A more subtle effect of exuberant theater designs was their ability to create an atmosphere of imagination and suspended rationality. Through those doors and inside those darkened auditoriums patrons were transported to new worlds. The surrounding architectural features helped prepare them for that journey. Though theaters were built for entertainment, they were also businesses. Location was critical to their success, and theaters always managed to occupy prime downtown sites. Return on investment was important, so many theaters included leaseable commercial space flanking the theater itself and sometimes apartments above In some instances the front shops were small, while in others they were full-scale commercial spaces, necessitating the familiar long lobby/hallway (usually carpeted and adorned) leading to the deeply recessed auditorium.

Movies and movie theaters initiated cultural change. They had a broadening and homogenizing effect on small-town Utah, "creat[ing] an unprecedented common culture or experience."2 They brought the larger world into Provo and Panguitch and Parowan, and in the process bound them ever more tightly into the fabric of American culture.

The photographs on the following pages include a rep-

112Utah Historical Quarterly

resentative sample of Utah's historic movie theaters . Some of them remain standin g while others have given way to new developments.

The sweeping curves ofProvo's Princess Theater (c. 1913, below; now demolished) and the exotic detailing ofPeery's Egyptian Theater in Ogden (1924) set them apart from their neighbors. The Egyptian Theater alsofeatured an "atmospheric" ceiling in the auditorium that, through special effects lighting, simulated sunsets, clouds, and starlit night skies.

Below: Built c.1930, the Star Theater in LaPoint (Uintah County), typical of many small-town theaters, was used for a wide range of community activities, including stage shows, movies, community meetings, and even funerals. The stuccoed Mission-style facade contrasts dramatically with the roughhewn "stockade" construction (vertical logs) visible on the side walls. Like many small-town theaters, it struggled financially. After it stopped showing movies in 1931, due to the expense of films and projection equipment, it served as a dance hall and skating rink until it burned down in 1940/

Below: Escalante's Star Theater, built in 1938, stands out on the local scene with its rounded parapet and use ofpetrified wood insets on the pebbledashfacade. The building had "Escalante"painted on the roof to help guide early aviators.

The dramatic 1912 transformation of Salt Lake City's ratherplain, but still quite new (1908), Bungalow Theater into the regal Rex Theater illustrates the apparent needfor a theater to have an epic architectural presence if it was to be successful. The crown-topped Rex, complete with sentry knights at the corners, also featured paired ticket booths in front. Freestanding or projecting ticket booths were a commonfeature on theaters in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The castle-like Tower Theater in Salt Lake City (1933 photo) underwent a dramatic modernization in 1950 that obscured its original architecture and added the coffee and ice cream shop next door as a supplemental source of income. Built at 9h South and 9h East in 1921, it was one of the first theaters located outside the downtown area. It was also the city'sfirst theater with air conditioning.

Theaters drew packed houses of children on Saturdays, especially in the pre-television years. Kids could spend much of the day watching thefeature movie, several cartoons, a serial episode, and perhaps a comedy.

Compare the interiors of this theater and the one on the cover (both 1941 photos): The Rialto (on cover) exhibits classical elements popular during the movie palace era of the 1920s, while the Southeast Theater shows the sparse, angular decor consistent with 1930s and '40s Art Deco. Both theaters use the double-aisle arrangement of seats that continues to be the standard for movie theaters.

Opposite: Elegant lobbies presided over by uniformed ushers were one of the most memorablefeatures oftheaters. The lobby of Salt Lake's Capitol Theater (1944 photo), though more ornate than most, was typical in that it included promotionsfor coming attractions. Lobbies were also usedfor more blatant advertising, ranging from the simple adfor a radio station in the Paramount Theatre (1942) to the gauntlet of appliance displays in the Utah Theater lobby (1950).

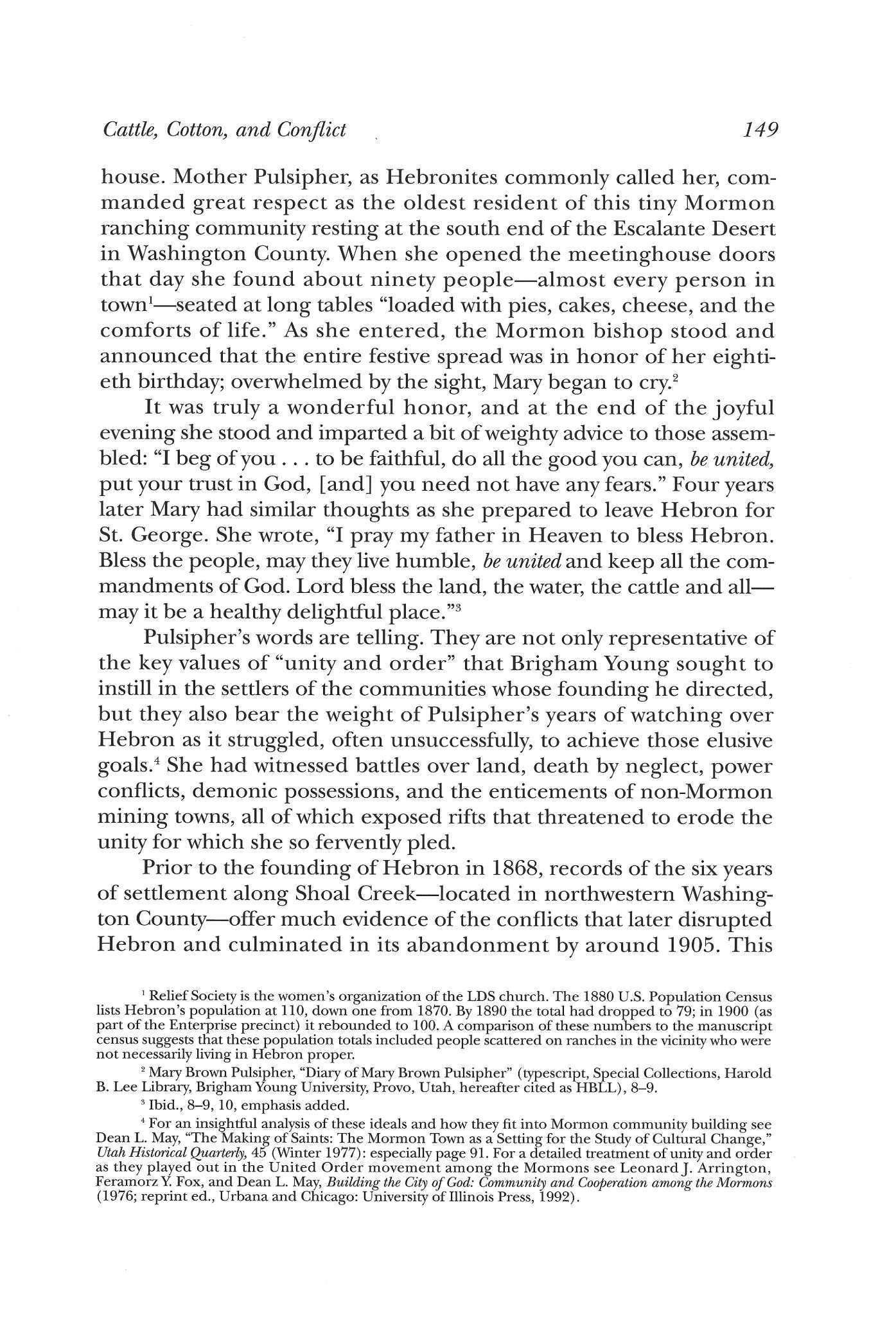

Utah Theater (Salt Lake City) snack bar at Easter time, 1950. Concession stands became increasingly important sources of revenue in theaters, eventually (by the 1980s) emerging as the main source ofincome.4

! I

The smooth stucco finish and streamlined curves of the Art Moderne-style Murray Theater (1938) represent a dramatic shift toward modern architecture and awayfrom the exotic revival styles of earlier decades.

Upper left: This movie at the Paramount Theater in 1936 attracted a long line of Salt Lakers. Movies were a popular, and affordable, distraction during the depression; escapist orfantasy movies were especiallyfavored during this period.

Left: The Burk Theater on Midvale's Main Street (1949) is typical of virtually all small-town theaters, which were nestled comfortably in the heart of the downtown business district.

Orpheum Theatre, Salt Lake City (1934 photo). Projecting marquees, large vertical signs, and neon lights were signature elements of movie theater promotion. The overlit, overscale nature of theater signage was intended not only to "out-shout" other signs but also to capture the attention of fast-moving automobile travelers.5

At right: The Lyric (later Promised Valley Playhouse) Theater, Salt Lake City, 1947. As the marquee indicates, many older theaters had thefacilities to continue with stage performances even after shifting largely to movies.

Below: The Centre Theatre, constructed in 1937, was the first large theater to be built in Salt Lake City in almost two decades. It featured a distinctive neonlit circular marquee and a 90-foot corner tower (not yet constructed in this photo) that resembled the top of the Empire State Building. The auditorium was set toward the interior of the block, leaving the valuable streetfront locations available for revenue-generating shops. This Art Deco landmark was demolished in 1989.

The Villa Theatre (1949), located at 3092 S. Highland Drive in Salt Lake City, was one of Utah's first suburban theaters large, freestanding buildings located near growing residential areas.

Architect A. B. Paulson's design was described as "modern, though not radical" and included innovative "stadium " seating, which had recently been used in two theaters in Los Angeles.6 True to its suburban character, the theater offeredfree parking for 500 automobiles on the property.

The Star-Lite Drive-in Theater, located at 285 South 500 East in American Fork, c.1950. Going to the movies took on an entirely different meaning with the emergence of drive-ins. Though they had been around since the 1930s, drive-ins blossomed throughout the U.S. in the 1950s, growingfrom 547 in 1947 to over 4,000 by the mid-1950s.7Drive-ins were built alongside highways at the edge of towns, where land prices were low and visibility was high. Due to growth-induced land pressures and changing tastes of moviegoers, these theaters have been in dramatic decline during the last two decades. Today, only ten drive-ins are still in operation in Utah.

1 Gunnison Gazette, January 17, 1913

2 Carrie Richter, "Glitz and Glamour on Main Street: A History of the Small Town Movie Theater in Utah, 1915-1945," (MS thesis, Univ of Utah Graduate School of Architecture, 1997), 53-54.

3 Doris Burton, Settlements of Uintah County: Digging Deeper (Vernal, UT: Uintah County Library, 1998), 459-60 Photo courtesy of Uintah County Library Regional History Center

4 Maggie Valentine, The Show Starts on the Sidewalk (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 176 By 1989, candy counter receipts accounted for 80 percent of profits.

5 Richter, "Glitz and Glamour," 43

6 Salt Lake Tribune, August 22, 1948

7 Valentine, "The Show Starts," 160

fff

Reuben G. Miller: Turn-of-the-Century Rancher, Entrepreneur, and Civic Leader

BY EDWARD A GEARY

BY EDWARD A GEARY

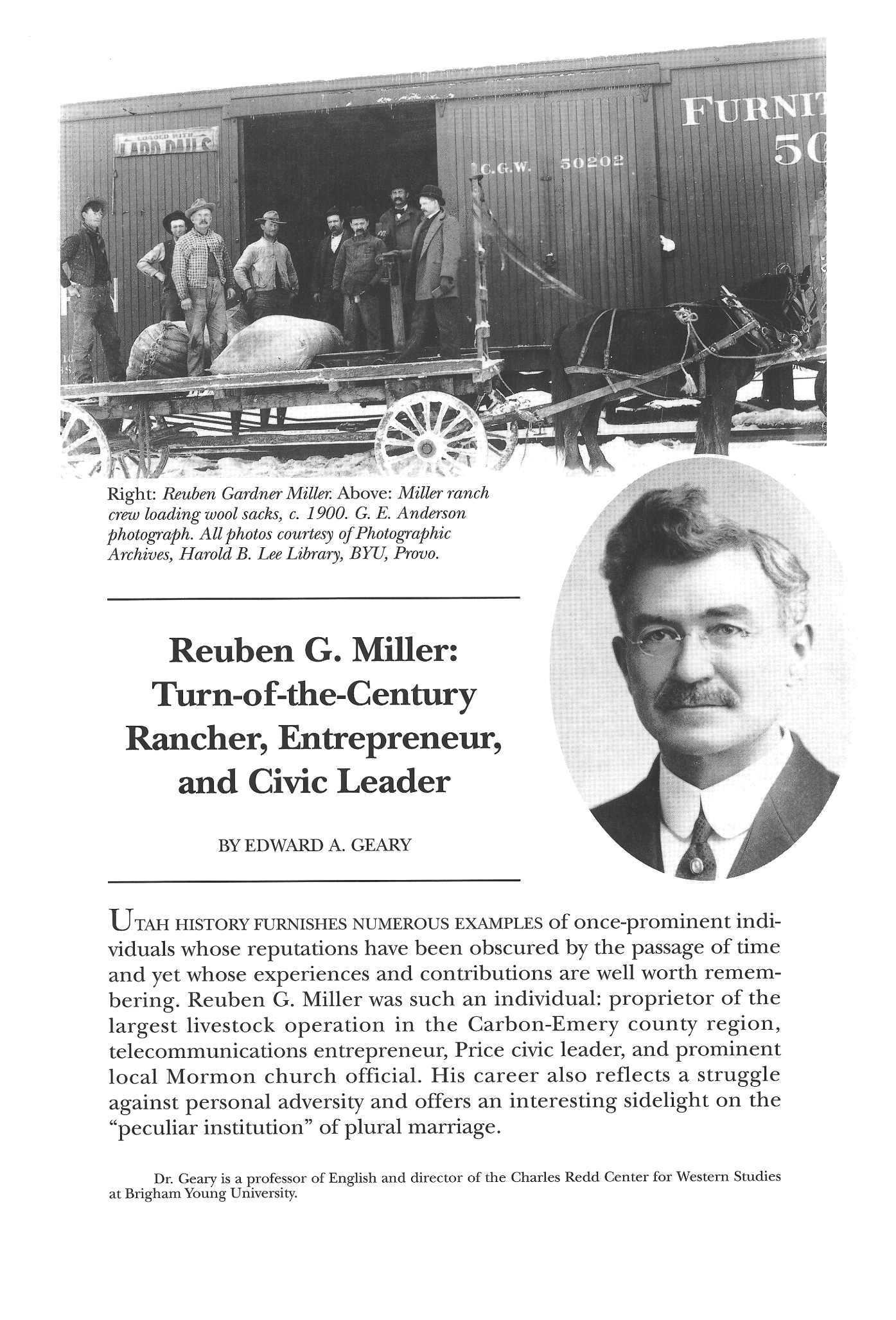

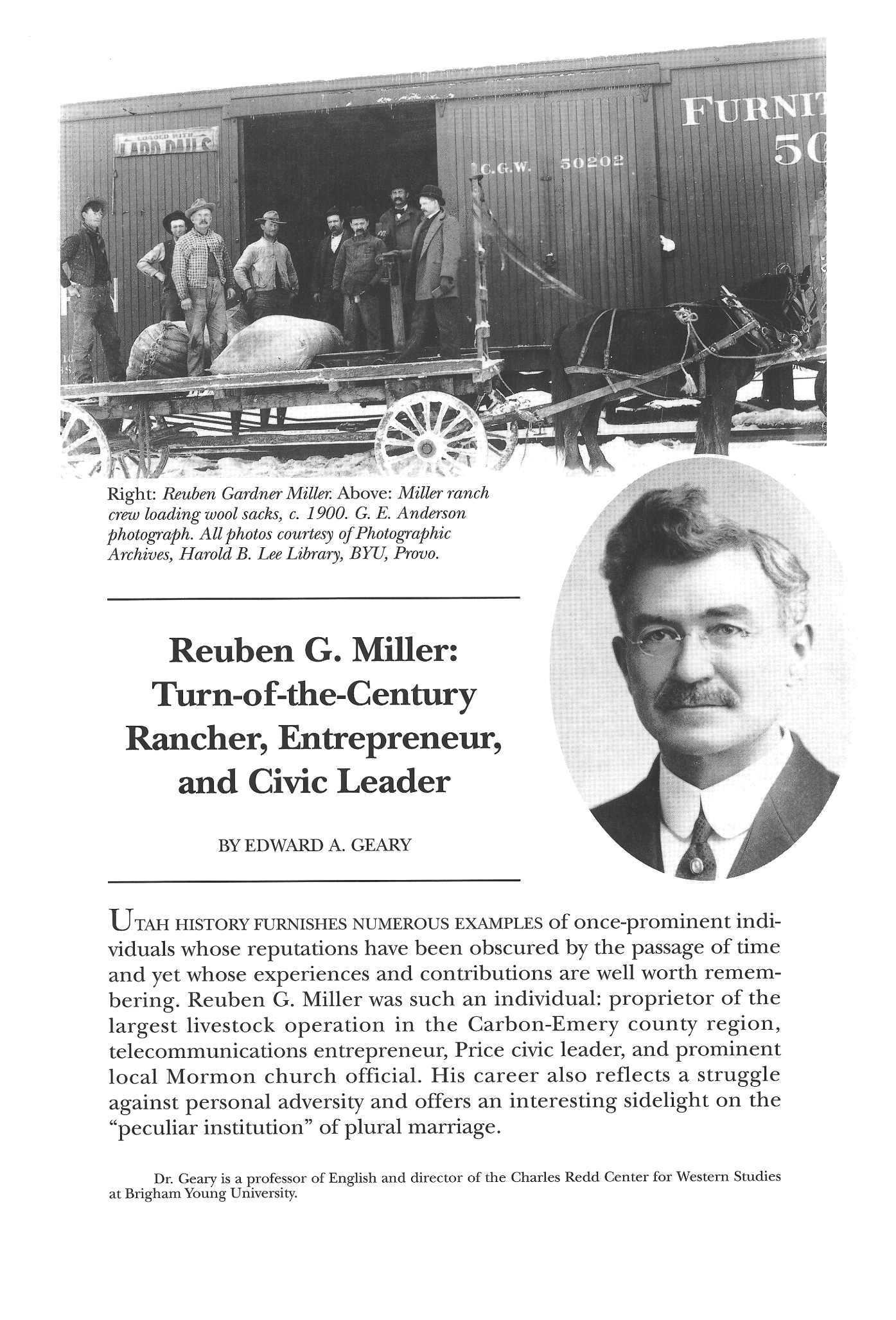

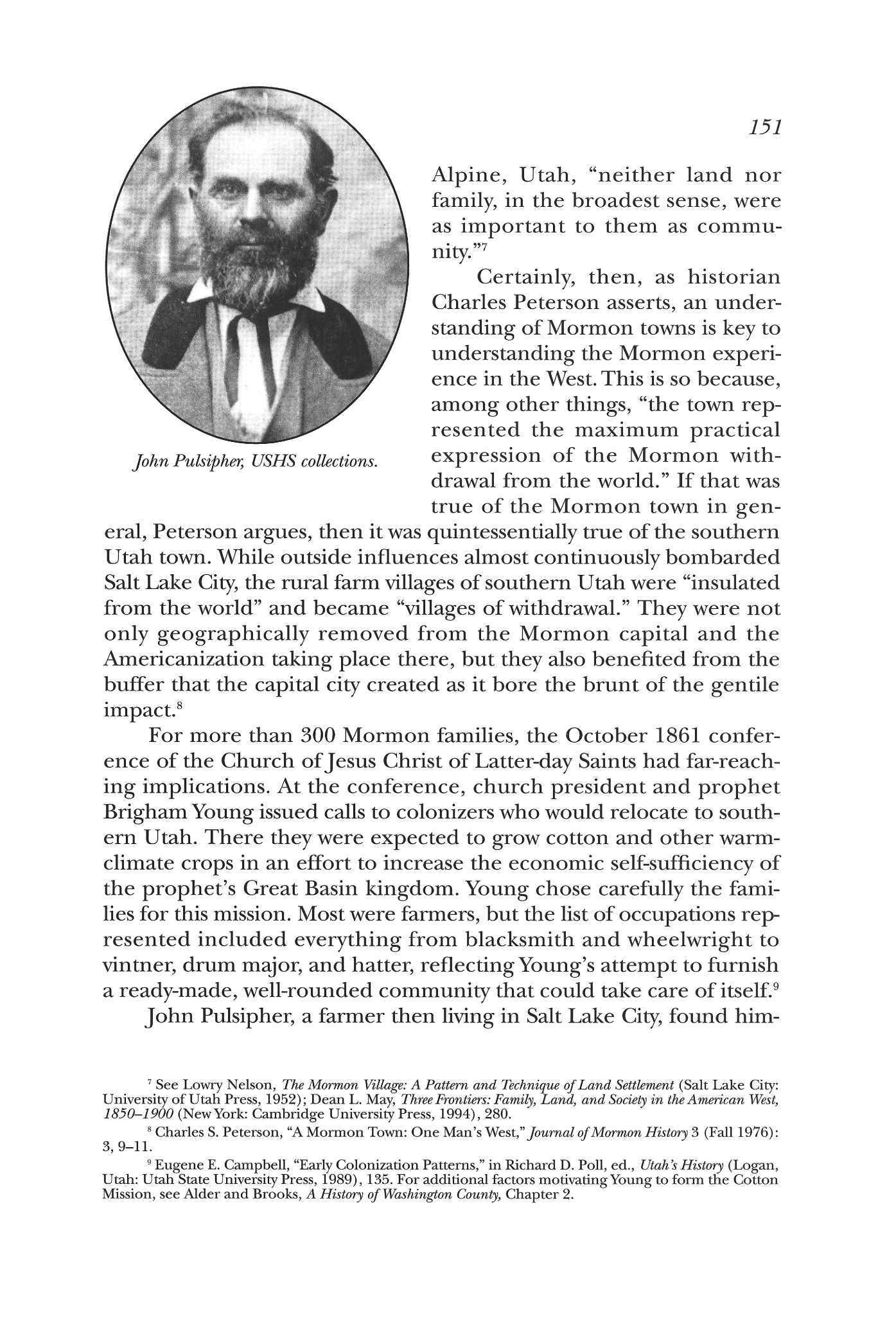

UTA H HISTORY FURNISHES NUMEROUS EXAMPLES of once-prominent individuals whose reputations have been obscured by the passage of time and yet whose experiences and contributions are well worth remembering. Reuben G. Miller was such an individual: proprietor of the largest livestock operation in the Carbon-Emery county region, telecommunications entrepreneur, Price civic leader, and prominent local Mormon church official. His career also reflects a struggle against personal adversity and offers an interesting sidelight on the "peculiar institution" of plural marriage.

Right: Reuben Gardner Miller. Above: Miller ranch crew loading wool sacks, c. 1900. G. E. Anderson photograph. All photos courtesy of Photographic Archives, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU, Provo.

Dr Geary is a professor of English and director of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University

No doubt Miller gained some of his entrepreneurial energy from his family background Reuben Gardner Miller was descended on both sides from prominent pioneer families. His maternal grandparents, Robert Gardner,Jr., andJane McCune (or McKeown), and their family arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in the fall of 1847. The following spring Robert and his brother Archibald erected the sawmill that gave Mill Creek its name. Robert took up land and built a home near the present intersection of Highland Drive and Thirty-ninth South where the family lived until 1861, when they were called to colonize the St. George area. 1 Miller's paternal grandparents, Reuben Miller and Rhoda Ann Letts, came to Utah in 1849 and settled on the north bank of Big Cottonwood Creek near Ninth East. Reuben Miller served as bishop of the LDS Mill Creek Ward from 1851 until his death in 1882.2

In 1858 the Millers' eldest son,James Robinson, married Robert Gardner's eldest daughter, MaryJane. The young couple acquired eighty acres south of Big Cottonwood Creek in the angle now formed by Forty-eighth South and Ninth East. Here Reuben G. Miller was born in a log cabin on November 7, 1861, the second of fourteen children The family moved to a five-room adobe house a short time after Reuben G.'s birth. In 1882 they erected a large brick home. This historic structure has been preserved and now serves as a clubhouse for residents of the Pine Lake condominiums.3

The Millers were an enterprising family. According to a biographical sketch composed in later years by Reuben G. Miller, James and his brother Reuben P. made seven round trips between Salt Lake City and Omaha with mule teams during the pre-railroad years, hauling "farm machinery, mill stones . . . and various articles of hardware and drygoods." The Miller brothers worked with their teams and scrapers on the Union Pacific roadbed in 1868, for which efforts they were "hansomely remunerated . . . and returned home with considerable means and useful impliments." In 1869 they secured a contract to haul ore from the Emma Mine at Alta to the smelter in Sandy, and in 1870 they contracted to build the segment of the Utah Central Railroad between Big and Little Cottonwood creeks

The Miller brothers also developed a farm implement sales busi-

1 Delila Gardner Hughes, The Life of Archibald Gardner (West Jordan, Utah: Archibald Gardner Family Genealogical Association, 1939), 25, 37-43

2 "Mill Creek Ward," in Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church offesus Christ ofLatter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing Company, 1941), 503-504

3 "James Robinson Miller," in The History of Murray City, Utah (Murray City Corporation, 1976), 406-407.

124Utah Historical Quarterly

ReubenG. Miller125

ness, owned one of the first threshing machines in the area, and owned large farms on Provo Bench and in Cache Valley. James R. Miller operated a flour mill on Big Cottonwood Creek from 1866 to 1896. In addition, he was a progressive farmer and was reputedly among the first in Utah to plant alfalfa, thereby getting three cuttings of hay each year where only one cutting had been harvested previously. Finally, a feed, coal, and hardware store first organized asJ. R. Miller and Company (later known as Miller and Cahoon) was a prominent business establishment in Murray for many years. 4

In a typical pattern for the period, young Reuben G. assisted in the family enterprises from an early age, spending, as he later claimed, "most of his time behind a plow, on a freight wagon, or in the saddle." He recalled being assigned, at the age of nine, to carry beer to the workers on the Utah Central construction crew and getting drunk after he decided to sample the brew. His schooling was irregular, confined to the winters, when there was less farm work He spent two terms at the University of Deseret but expressed regret in later years at "being deprived of schooling and embarrassed when drafted into public service in church and political positions."5

The Miller family entered the range livestock business in the late 1860s when the livestock business began to evolve into a major force in the territorial economy. Under early Mormon settlement patterns, communities were built around agriculture rather than stockraising Horses, cattle, and sheep were pastured in the hills near the towns, typically under the care of young boys. But as livestock numbers multiplied, these conveniently situated grazing lands became depleted. Orson Hyde, speaking to an LDS general conference in 1865, recalled that when the pioneers first arrived in the Salt Lake Valley "there was an abundance of grass" covering the benchlands "like a meadow." Less than two decades later, however, the grass had been replaced by "the desert weed, the sage, the rabbit-brush, and such like plants, that make very poor feed for stock."6

The range livestock industry in Utah had its beginnings when some individuals and families began to assemble herds of surplus animals and take them to the west desert or to the mountain valleys east

4 Miller Brothers Co ranch acreage list, box 3, folder 7, Reuben Gardner Miller Collection (Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; hereinafter cited as RGM Collection); biographical sketch ofJames Robinson Miller, box 4, folder 4, RGM Collection

5 Deseret News, November 25 1951, clipping in box 2, folder 1, RGM Collection; notebook, box 1, folder 5, RGM Collection; diary, January 10, 1949, box 1, folder 11, RGM Collection

6 Orson Hyde, "Instructions Concerning Things Temporal and Spiritual," in fournal ofDiscourses by President Brigham Young, His Two Counselors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others (Liverpool, 1867), 11:149.

of the Wasatch Front James R Miller's brothers Reuben P and Melvin undertook such an operation in the Cherry Creek area of the West Tintic mountains, herding cattle at first at a charge per head and later in exchange for a share of the calf crop, which they found to be a more profitable arrangement. Other family members contributed their surplus stock to this growing herd. When James obtained an appointment as pound keeper for the South Cottonwood district, he purchased unclaimed stray animals and sent them to Cherry Creek. The cattle were a motley assortment descended from mixed-breed milk cows, heavy draft animals, and wiry, long-limbed Texas longhorns. In an effort to improve the quality of their herd, the Miller brothers imported purebred shorthorn bulls in 1872 and 1874 "for Range Breeding purposes."7

The western valleys of Utah held a rich supply of accumulated forage when domestic livestock were first taken there Hyrum Bennion, a member of another early stockraising family, recalled, "When we first came to the south end of Rush Valley in 1860 we thought it was the best range in Utah, because we could stay in one place all the year round. But by 1875 it was all et out, and we had to move our cattle to Castle Valley." The Miller brothers faced a similar situation in the Cherry Creek region. Together with another Murray-area resident, Jonas Erekson, who also had cattle in the West Tintic mountains, the Millers moved their growing herd to the Wasatch Plateau in central Utah in the summer of 1875 and then east into Castle Valley for the winter, establishing a camp at the point where Huntington and Cottonwood creeks converge to form the San Rafael River.8

In the mid-1870s Castle Valley, and indeed all of eastern Utah, was virgin range, as the west desert had been fifteen years earlier. Beginning in 1874 or 1875 large numbers of livestock were moved from the crowded ranges of western Utah across the mountainous backbone that separates the Great Basin from the Colorado Plateau. According to Charles S Peterson, "It is difficult to know how many cattle were trailed from the Great Basin into eastern Utah, but it is certain they numbered in the hundreds of thousands." In addition to the Millers, Ereksons, and Bennions, other stockraisers who came to

7 See Charles S Peterson, "Grazing in Utah: A Historical Perspective," Utah Historical Quarterly 57 (Fall 1989): 300-319; biographical sketch ofJames Robinson Miller, box 4, folder 4, RGM Collection; notebook, box 1, folder 5, RGM Collection

8 Quoted in Glynn Bennion, "A Pioneer Cattie Venture of the Bennion Family," Utah Historical Quarterly 34 (Fall 1966): 319; undated letter from RGM to Lamont Johnson in response to an inquiry dated January 14, 1950, typescript carbon copy in box 3, folder 4, RGM Collection

126Utah Historical Quarterly

ReubenG. Miller127

Castle Valley during this period included the Swasey brothers from Juab County, William H. Chipman from American Fork, Mike Molen from Lehi, George and James M. ("Tobe") Whitmore from St. George and Nephi, Orange and Wellington Seely from Mount Pleasant, Lee Lemmon from Mill Creek, William Gentry and the Starr brothers from Springville, Daniel Davidson from Salt Lake City, and a mysterious Britisher who styled himself as Lord Scott Elliott. Under such intensive grazing pressure this range too was soon depleted. A railroad surveyor who worked in the region for several months in 1881 and 1882 reported seeing "great numbers of cattle apparently feeding along the mountainside, although I could not see what in the world they found to eat."9

The grazing frontier was a passing phase Faced with a deteriorating range and the added competition of the permanent settlers who entered Castle Valley beginning in 1877, most of the large livestock outfits left the region within a few years. The Miller brothers remained. In 1876 they had once again trailed their cattle to the Wasatch Plateau; that fall they established a permanent camp on what came to be known as Miller Creek and erected a log cabin that they called the Winter House. The following year they built the Summer House near a spring that still bears that name on the high benches of the Gordon Creek drainage.10

Initially, like most other stockraisers, the Miller brothers established their claim to the public lands by customary use According to a local history, the Millers and Whitmores had an informal agreement whereby "the Whitmores ran their cattle entirely on the north side of the Price River, while the Miller Brothers covered the south side." Over time, the Millers acquired title to key properties that included the Winter House headquarters ranch, the Summer House ranch, several hundred acres of rich meadowland in Pleasant Valley (an area later covered by the waters of Scofield Reservoir), and a 200-acre hay farm near Huntington. From this base in deeded land, the Miller operation dominated more than 500 square miles of the public domain extending from Pleasant Valley to Cedar Mountain and the San Rafael Swell. Pleasant Valley and the 10,000-foot Castle Valley Ridge provided high-quality summer grazing. The Gordon Creek benches, at an elevation above 7,000 feet, supplied an abundant

9 Peterson, "Grazing in Utah," 306; Francis Hodgman, "In the Mountains of Utah," Colorado Rail Annual 1992, 29.

10 RGM to LamontJohnson (1950), box 3, folder 4, RGM Collection

Locations City Locations Minor Roads Major Roads Water Courses - County Lines

Note: Miller Ranch properties are shown in relation to current geographic features Cartogn

Main Miller ranch properties

growth of bunch grass in the spring. The lower benchlands between Price and Huntington were more sparsely vegetated but were seldom covered by snow in the winter.11

Active management of the Miller brothers livestock operations during the early years was in the hands of Reuben P. and Melvin while James managed the business interests in Murray and made only occa-

11

T ; \ 96 Scofield

inch

i Ranch e Ranch.

James Liddell, "The Cattle and Sheep Industry of Carbon County," in Thurseyjessen Reynolds et al., Centennial Echoesfrom Carbon County (Carbon County Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1948), 52; Miller Brothers Co ranch acreage list, box 3, folder 7, RGM Collection

ReubenG. Miller129

sional visits to the ranch. In addition to their Castle Valley ranches, the Miller brothers partnership also owned large farms on Provo Bench and in Cache Valley. Young Reuben G. Miller apparently began working on the ranch in 1879 at age eighteen, riding with the cowboys and picking up some habits of which his parents did not approve. In 1880 his father gave him a mare in return for a promise to "quit using tobacco."12

In 1883 the Millers sold most of their cattle to a Colorado buyer and went into the sheep business. This was a representative move in a trend that saw sheep numbers on Utah ranges increase from fewer than one million in 1880 to almost four million by 1900.13 Sheep, though requiring more care, were potentially more profitable than cattle because they returned a double crop of wool and lambs In addition, they were better adapted to survive on marginal grazing lands, which many Utah ranges had become. The Miller brothers purchased 4,000 sheep in California in 1882, and Melvin Miller trailed them to Utah in company with another large herd belonging to Lee Lemmon and Al Starr. The herd spent the winter of 1882-83 in the Deep Creek Mountains on the Utah-Nevada border. In November, young Reuben G went with Al Starr to take supplies to the overwintering herders, a trip that he recalled fondly in his later years.

The Millers enlarged their sheep operation through other purchases in Wyoming and northern Utah and by natural increase until the brothers were typically shearing between 15,000 and 20,000 animals each year at their Pleasant Valley pens They continued to run several hundred head of cattle that wintered at the Huntington farm and on nearby Poison Spring Bench and summered on Cedar Mountain A sizeable herd of horses apparently grazed throughout the year in the environs of the Summer House ranch, and the Millers loaned unbroken horses to local farmers without charge; the farmers would break the horses to work, use them for a year, then return them in exchange for fresh animals Of course, the Millers could then sell the broken-in horses for a much better price than they could get for raw colts.14

Beginning in 1883, Reuben G. Miller assumed major responsibilities in the sheep operation He moved camp and hauled supplies for

12 Notebook, box 1, folder 5, RGM Collection

13 Peterson, "Grazing in Utah," 305

14 Reuben Brasher and Stella McEIprang, "The Livestock Industry," in Castle Valley: A History of Emery County (Emery County Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1949), 38

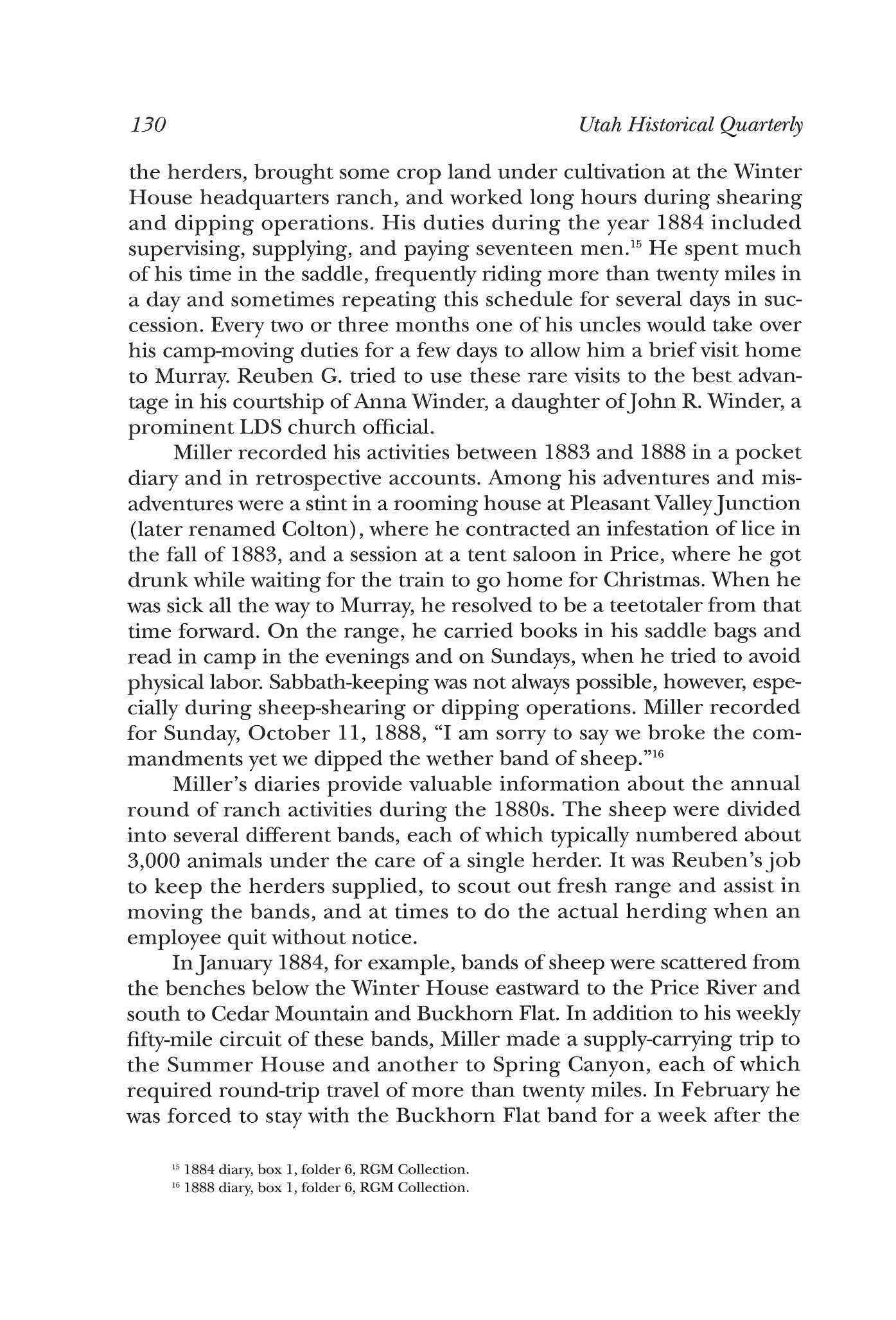

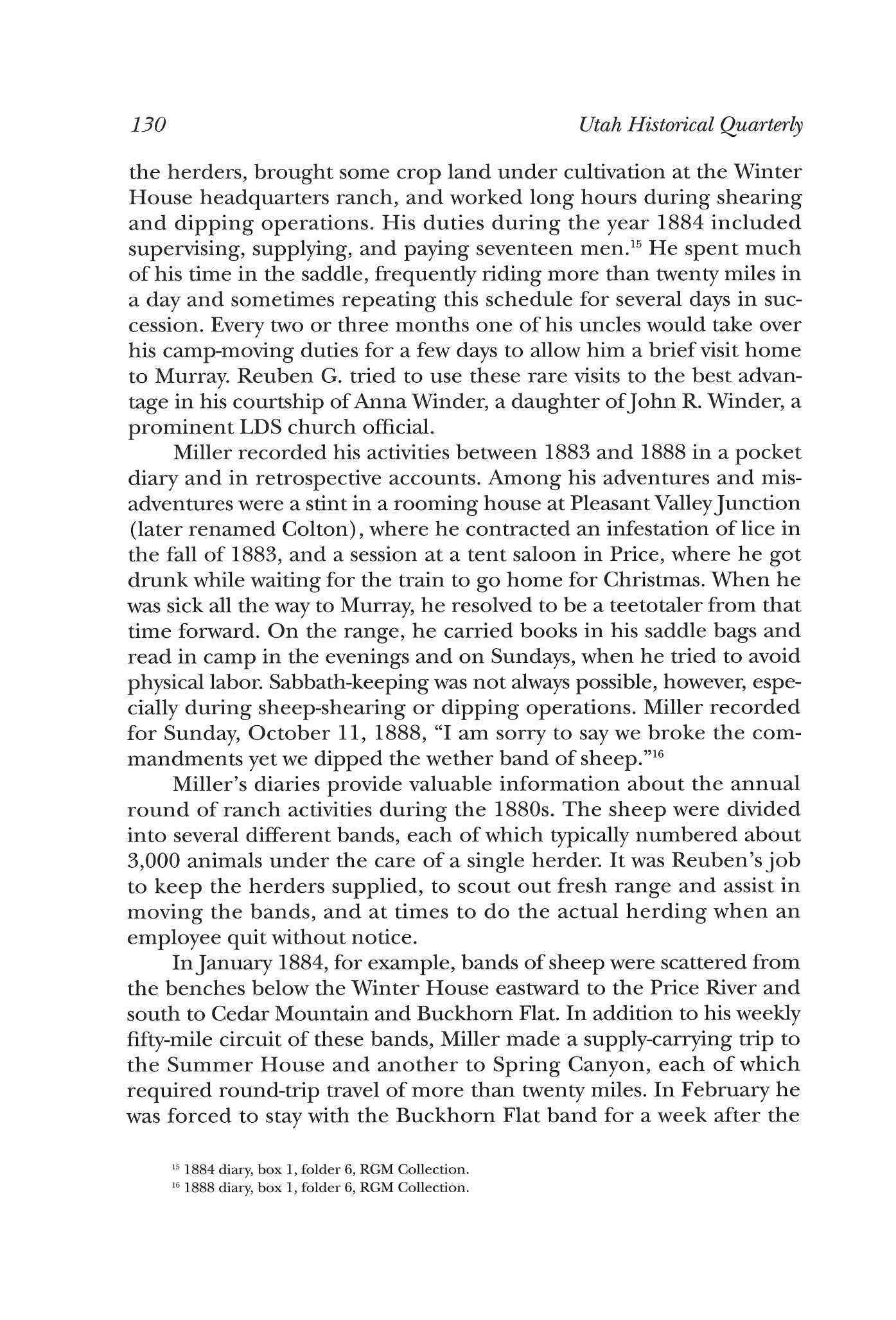

the herders, brought some crop land under cultivation at the Winter House headquarters ranch, and worked long hours during shearing and dipping operations His duties during the year 1884 included supervising, supplying, and paying seventeen men. 15 He spent much of his time in the saddle, frequently riding more than twenty miles in a day and sometimes repeating this schedule for several days in succession. Every two or three months one of his uncles would take over his camp-moving duties for a few days to allow him a brief visit home to Murray. Reuben G. tried to use these rare visits to the best advantage in his courtship of Anna Winder, a daughter ofJohn R. Winder, a prominent LDS church official.

Miller recorded his activities between 1883 and 1888 in a pocket diary and in retrospective accounts Among his adventures and misadventures were a stint in a rooming house at Pleasant Valley Junction (later renamed Colton), where he contracted an infestation office in the fall of 1883, and a session at a tent saloon in Price, where he got drunk while waiting for the train to go home for Christmas When he was sick all the way to Murray, he resolved to be a teetotaler from that time forward. On the range, he carried books in his saddle bags and read in camp in the evenings and on Sundays, when he tried to avoid physical labor. Sabbath-keeping was not always possible, however, especially during sheep-shearing or dipping operations Miller recorded for Sunday, October 11, 1888, "I am sorry to say we broke the commandments yet we dipped the wether band of sheep."16

Miller's diaries provide valuable information about the annual round of ranch activities during the 1880s. The sheep were divided into several different bands, each of which typically numbered about 3,000 animals under the care of a single herder. It was Reuben's job to keep the herders supplied, to scout out fresh range and assist in moving the bands, and at times to do the actual herding when an employee quit without notice.

InJanuary 1884, for example, bands of sheep were scattered from the benches below the Winter House eastward to the Price River and south to Cedar Mountain and Buckhorn Flat In addition to his weekly fifty-mile circuit of these bands, Miller made a supply-carrying trip to the Summer House and another to Spring Canyon, each of which required round-trip travel of more than twenty miles. In February he was forced to stay with the Buckhorn Flat band for a week after the

130Utah Historical Quarterly

151884 diary, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection

16 1888 diary, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection

ReubenG. Miller131

herder quit. In March, in addition to his camp-moving responsibilities, he helped his uncle Reuben P. and his younger brother Will build a corral at the Winter House. In April he went home for a two-day visit then returned to the ranch to assist in moving the sheep up to the higher Miller Creek and Gordon Creek benches.

On May 9 he carried supplies to the Summer House and spent the night at the cabin of Frank Rhoades, lower on Gordon Creek, where they "talked about the cattle business and how we need to watch our neighbor ranchers." Several days in late May were spent in docking lambs. On June 5 he went to Huntington to help the cowboys start the cattle toward the summer range on Cedar Mountain. On June 9 he began driving sheep to the summer range in Pleasant Valley, where he later spent several days with his father, his brothers, and his uncle Reuben P. constructing shearing pens Shearing began onJune 23 and continued into mid-July, followed by several days of forcing

the sheep through dipping vats to control ticks and Anna Jane Winder Miller. " & r r » other vermin Miller went home to Murray onjuly 22 and worked on the farm there, putting up hay, until August 4, when he caught the train for Pleasant Valley. After several more days of dipping sheep, he drove a small herd of calves from the Summer House to Murray, a trip that required four days

After a week at home, Reuben took the train to Richmond, Cache County, for a two-day visit with Anna, who was staying there with her mother. Then it was back to the ranch on September 3 and a circuit of the sheep camps, now located in the Beaver Creek area east of Pleasant Valley On September 21 he went to the Summer House to assist with the horse roundup. Then it was down to the Winter House on October 4, followed by a two-week visit home and a return to the ranch on October 27. The first three weeks of November were devoted to moving the sheep to the winter range On November 24, Miller went home to prepare for his wedding to Anna Jane Winder on December 10. Wedding and Christmas parties occupied the time until December 31; Reuben then left his bride in a refurbished log cabin on his parents' farm and went back to the ranch.17

The next year followed a similar schedule, but Reuben managed more frequent visits home, and Anna spent two weeks at the ranch in June. On the other hand, his duties required him to move sheep

17 1884 diary, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection

" - ~~

camps on Christmas Day The diaries provide only vague insights into Anna's view of this long-distance marriage. During her stay at the ranch, "Anna was croshaing and found it was Sunday 8c said she wouldn't work another bit."18 During a visit home onjuly 1, Miller recorded, "Anna cried at night"; and onjuly 9, "I had to cook breakfast as Anna was sick." In the 1888 diary there appears the notation "Anna had the blues" on the day before Reuben's departure for the ranch.19 It is difficult to determine whether these emotional disturbances were caused by her husband's frequent absences, by her pregnancies, or both. The Millers' first child, Gertrude, was born on March 4, 1886, and James Rex was born on September 29, 1888.

During the period when he was employed by the Miller brothers partnership, Reuben G. was apparently paid a salary plus bonuses based on the wool receipts. For the year 1884 he earned $1,570, a good income for that period. InJune 1885 he recorded, "Pap gave me $400 in cash & told me may be there would be a little more if the Boston wool was sold."20 This payment evidently represented a bonus for the previous year's work

The Millers had an exceptionally good summer range, but with the passage of time it became necessary to go farther afield in search of winter grazing. By the winter of 1887-88, Reuben was tending camps in the Woodside area, a considerable distance farther from the Winter House than the ranges used in earlier years. Even there it seems that the feed was insufficient for the numbers of stock. Reuben recorded on February 4, "Went south to look out a place to move camp but found more sheep than country."21

Miller's ranch life was interrupted in 1888 when he was called to the LDS Southern States Mission. He left home on November 6, only a few weeks after the birth of his second child,James Rex. He spent most of the next two and a half years in rural West Virginia, not the most hospitable environment for a Mormon missionary. In a letter to his parents he compared the narrow Appalachian valleys to the finger canyons on the Miller range at the head of Gordon Creek: 'You know when you get on the Ridge going from Pleasant Valley to Summer House you can look down into the heads of dozens of Canyons well down injust such Canyons in this Country are the homes of the inhabitants of this land." 18

132Utah Historical Quarterly

30,

1,

6,

6,

1885 diary, entry for June 14, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection. 19 1888 diary, entry for April 29, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection 20 1885 diary, entry for June

box

folder

RGM Collection 21 1888 diary, box 1, folder

RGM Collection

ReubenG. Miller133

It was, he added, "one of the roughest places that ever I saw for people to be living in and all pretending to be farmers."22

On his return from his mission in 1891, Miller assumed the full management of the ranch The early 1890s were a profitable period The 112,867 pounds of wool sheared in 1891 sold for $16,648. The return was almost the same in 1892, and Reuben and Anna used a portion of their dividend for a trip to the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. He also undertook several improvements, erecting a new house and barn at the Summer House and fencing property in Pleasant Valley and Gordon Creek. However, the Cleveland Depression hit the wool market in 1894, when the Miller wool brought only $6,408 Perhaps as a consequence of this decline in profits, the Miller brothers partnership was dissolved in 1896, and Reuben G. made arrangements to purchase the ranch holdings.23

Miller's regular diary-keeping did not continue for long after his mission In an isolated entry explaining a two-year lapse, he wrote, "On acct. of the monotony of all days seeming the same neglected this diary and ceased writing from July 1891 till this dayJuly 11th 1893. My time has been passed on the Ranch and only have been home on short visits of a few days at a time during the two years."24 Apparently there would be a few breaks in the monotony, however. In a summary of important events in his life, composed sometime after 1936, Miller wrote that he had made the acquaintance of the notorious outlaws Butch Cassidy and Joe Walker during the period betweenJanuary 18 and March 31, 1897, evidently while the Miller sheep were wintering in the San Rafael country.

He also recorded, "Was held up byJoe Walker at the point of a Pistol, down in Buckhorn draw, and very much abbused by him in vile

Miller's "commodious residence" in Price, purchasedfrom Carl Valentine in 1897. G. E. Anderson photo.

22 RGM to J R Miller, February 10, 1890, box 1, folder 4, RGM Collection

23 1891 diary, entry for July 4, box 1, folder 7, RGM Collection; 1893 diary, entries for July 11-25, box 1, folder 7, RGM Collection; Cattle, Horse, and Sheep Memoranda, box 3, folder 7, RGM Collection; biographical sketch ofJames Robinson Miller, box 4, folder 4, RGM Collection.

241893 diary, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection.

Miller's "commodious residence" in Price, purchasedfrom Carl Valentine in 1897. G. E. Anderson photo.

22 RGM to J R Miller, February 10, 1890, box 1, folder 4, RGM Collection

23 1891 diary, entry for July 4, box 1, folder 7, RGM Collection; 1893 diary, entries for July 11-25, box 1, folder 7, RGM Collection; Cattle, Horse, and Sheep Memoranda, box 3, folder 7, RGM Collection; biographical sketch ofJames Robinson Miller, box 4, folder 4, RGM Collection.

241893 diary, box 1, folder 6, RGM Collection.

words although he did not do me any violent harm." A short time later, after the April 21, 1897, payroll robbery at Castle Gate, the Carbon County sheriff stopped at the Winter House to borrow horses to use in the pursuit of the outlaws. Evidently unimpressed by the lawman's zeal, or lack thereof, Miller noted that he "Killed time to let them get away." The following year, one of Miller's cowhands, Jim Inglefield, was a member of the posse that killedJoe Walker in the Book Cliffs.25

Although he continued to maintain a home in Murray until 1897, Miller was assuming an increasingly prominent role in public affairs in Price and eastern Utah. He was chosen as one of three selectmen (an office roughly equivalent to county commissioner) when Carbon County was created in 1894 In 1896 he was elected, as a Republican representing the five counties of eastern Utah (Carbon, Emery, Grand, San Juan, and Uintah), to the first Utah state senate. In 1897 he moved his family from Murray to "a commodious residence" in Price By this time the family consisted of daughter Gertrude and four sons, Rex, Milton, Byron, and Clarence. Three additional sons were born in Price but died in infancy.26

In 1898 Carbon County voters elected Miller to the state house of representatives. InJanuary 1899 he was installed as president of the Emery LDS Stake with authority over thirteen local wards that extended in a wide arc from Sunnyside, twenty-five miles east of Price, to Castle Gate, twelve miles north, and Emery,fifty-fivemiles to the southwest. This ecclesiastical position, combined with his civic activities and his large-scale livestock operations, made Reuben G. Miller at the age of thirty-eight the most prominent and influential individual in the Carbon-Emery region

134Utah Historical

Quarterly

? •>'•"•<£

j

^5sS

1,—IJ

f&j

2ffljjjpSmf£Mr " -

f *,$sn^o?SB*vi--

Newly completed Price Public School and students, 1902. G. E. Anderson photograph.

25

Memorandum book, box 1, folder 5, RGM Collection.

26

Eastern Utah Advocate (Price, Utah), September 22, 1898; book of family and genealogical memorabilia, box 3, folder 9, RGM Collection

ReubenG. Miller135

The settlement of the Price River Valley had begun about three years after the Miller brothers first brought their livestock to the region. In 1882-83 the building of the Rio Grande Western Railway provided a crucial stimulus for development, particularly in coal mining Railroad construction crews uncovered a large seam of coal at Castle Gate; the railroad also improved connections to the existing mines in the Scofield area. Through its subsidiaries—PleasantValley Fuel Company and Utah Fuel Company—the Rio Grande developed several new mines and dominated coal production in the region for several decades.

In 1900 Price had a population of only 655, substantially less than the coal towns of Castle Gate (1,109) and Scofield (956). However, Price was a more important regional center than its size might suggest. The seat of Carbon County, it was home to several mercantile establishments and a weekly newspaper. The city served as the trading and transportation center for the Emery County communities to the south and was also the most convenient rail connection and hence the main shipping point for the communities, Indian agencies, and gilsonite mines in the Uinta Basin. According to the Utah State Gazetteer for 1900, "In the matter of freight handled [Price] is considered the third station on the R.G.W. Ry. system, ranking next to Ogden." Price counted among its residents at the turn of the century several other stockraisers and business entrepreneurs who would play significant roles in the town's development. The capital and initiative supplied by these individuals, combined with the town's advantageous location for a regional commercial center, fostered growth to a population of 1,122 by 1910 and 2,777 by 1920.27

Reuben G. Miller was one of these businessmen, devoting an

Emery Stake Academy building and students, graduation day, 1906 (note the date on the roof). G. E. Anderson photograph.

27 Utah State Gazetteer and BusinessDirectory (Salt Lake City: R L Polk, 1900), 210; Ronald G Watt, A History of Carbon County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997), 71-74

Emery Stake Academy building and students, graduation day, 1906 (note the date on the roof). G. E. Anderson photograph.

27 Utah State Gazetteer and BusinessDirectory (Salt Lake City: R L Polk, 1900), 210; Ronald G Watt, A History of Carbon County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997), 71-74

increasing share of his time and resources to the growing Price economy. He and his family held a majority of the stock in the Price Cooperative Mercantile Institution, established in 1901 Also in 1901 Millerjoined with fellow stockman J. M. Whitmore and others in organizing the First National Bank of Price, with Miller as vice president and director. In addition he served as president of the town board (a position equivalent to mayor) from 1902 to 1904 and as president of the local school board during the same period, overseeing construction of a new eight-room brick school. When the other members of the school board refused to pay the architect's fee, Miller reportedly paid it out of his personal funds.

It is interesting to note that Miller played an important role in supporting both public and church-related education During the same period when he was pushing forward the construction of a new school in Price, he also promoted the growth of the Emery Stake Academy in his role as president of the stake board of education. Founded in 1889 and suspended in 1894, the academy was reopened in 1899 after Miller assumed the stake presidency. Under his leadership a building begun in Castle Dale in 1896 was finally completed and dedicated in 1903, and a competing church-operated seminary at Huntington was closed. Enrollment at the academy grew from sixtyfive in 1901 to 140 in 1907. At the 1907 commencement exercises, President Miller announced plans for a new and much larger building to be erected on the bench overlooking Castle Dale.28 This threestory structure was first occupied during the 1910-11 school year. It would appear from his activities that Miller's concept of the roles of public and church-sponsored education was similar to that held by others in the region: the public schools were to provide a primary education (variously conceived of as extending through grades five, six, seven, or eight), with high school-level instruction left to the church academies. The first public high school in the region was not established until 1912, two years after Miller moved away.

With these business, civic, and ecclesiastical responsibilities, Miller was able to give less time to his livestock interests than he had in earlier years. Still, he continued to manage the ranch and spent considerable time on the range. For example, the local newspaper reported in the fall of 1901, "Hon. Reuben G. Miller has been in the

136Utah Historical Quarterly

28 Paul Robert Tabone, "The History of Emery Stake Academy" (master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 1976), 105; Emery Stake Academy Announcements, 1910-11, Library Archives, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah

ReubenG. Miller137

hills for some two or three weeks, looking after his sheep, cattle and horses, which he says are all in good condition."29

The early years of the twentieth century brought significant changes to the range livestock industry. The unregulated growth in sheep numbers had resulted in severe overgrazing and watershed damage; in addition to the locally owned stock, so-called "tramp herds" were shipped into Utah by rail in the spring, trailed over the mountain ranges through the summer, and shipped out in the fall. Eventually, farmers and townspeople, becoming concerned about floods from denuded watersheds and about the quality of their water supply, demanded controls on grazing In response to such concerns, the federal government established several national forests in Utah during the first decade of the century. Despite the political clout of the powerful woolgrower lobby, forest managers, with the support of local officials and small farmer-stockmen, succeeded in reducing the number of livestock allowed in the forests and gave preferential treatment to the owners of small herds who also farmed land near the forests. Largely as a result of these efforts, the number of sheep on Utah ranges declined by more than one million between 1900 and 1910.30

The vast public domain outside the national forests remained unregulated except by customary usage. But there, too, changes were occurring. New immigrants whose cultural traditions were deeply involved with sheep raising were coming to Utah. The French were the first of these to arrive in the Carbon County area, some coming from the Basque country near the Pyrenees and others from the

29 Eastern UtahAdvocate, October 15, 1901.

30

Price Trading Company store, c. 1900. Miller's Price Coop was a rival to this company, which was controlled by stockmanJames R. "Tobe" Whitmore. G. E. Anderson photo.

For a good account of these events on the Manti National Forest see the relevant chapter in Albert Antrei, ed., The OtherForty-niners: A Topical History of Sanpete County, Utah, 1849-1983 (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1982); Peterson, "Grazing in Utah," 305

Piedmont region in southeastern France. They were followed by the Greeks, who originally came to work in the mines but several of whom soon made their way into the sheep business. Because of their experience and their willingness to stay on the range for extended periods, these newcomers were formidable competitors for the grazing lands. (Pierre Moynier, for example, claimed that he once spent three years out with his herd without ever going into town.)31

The Miller ranch was better situated than most to weather these changes. The mountain range on Castle Valley Ridge where Miller livestock had traditionally grazed was not included in the Manti National Forest, established in 1903. Still, there were some who refused to recognize the traditional Miller claim to this range, and competition became ever more intense for the winter and spring ranges in the valley. The Price newspaper reported in 1902, "Hon. R. G. Miller is figuring on taking to the Eastern market in the near future five to six cars of cattle and horses, because, he says, the range is playing out."32

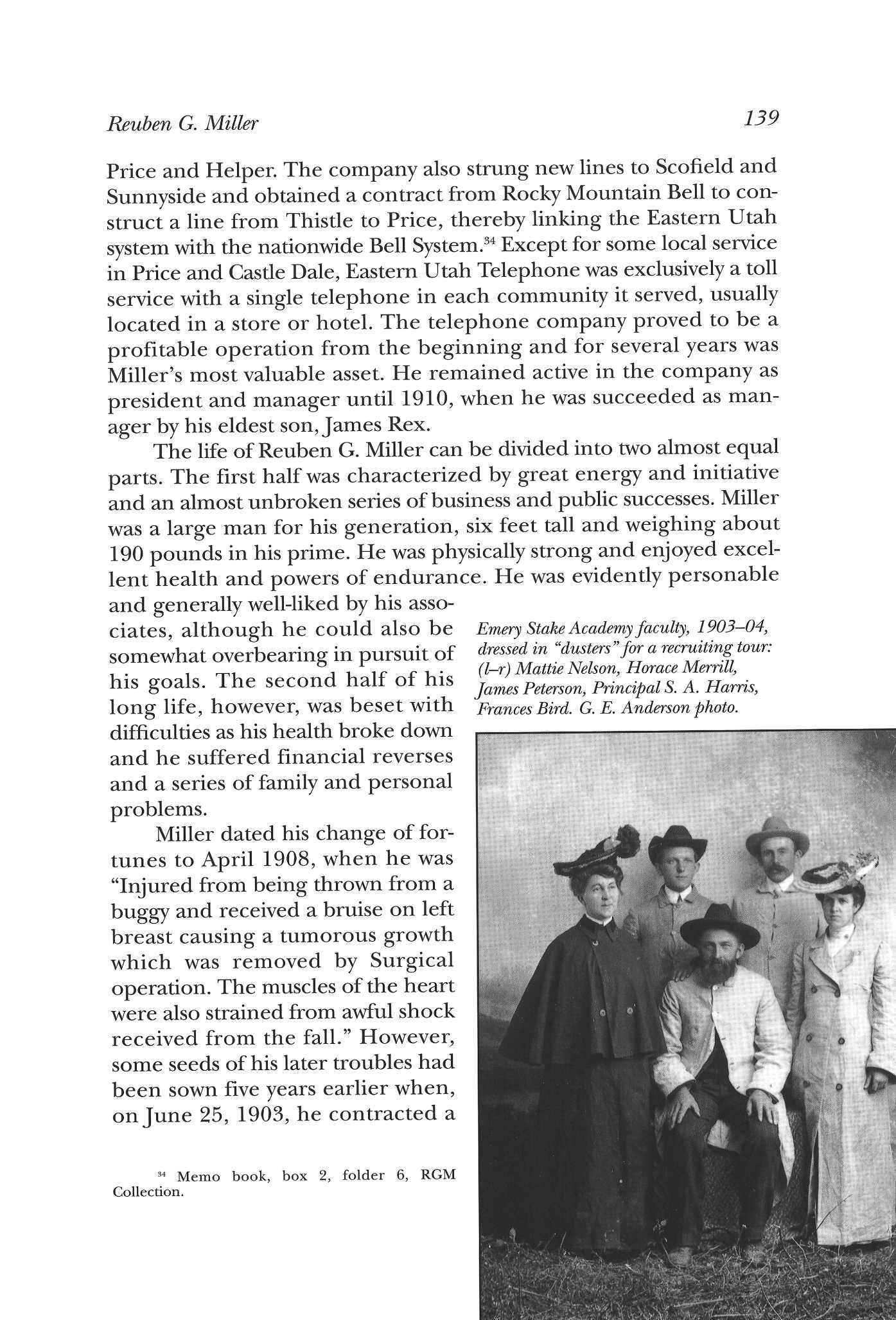

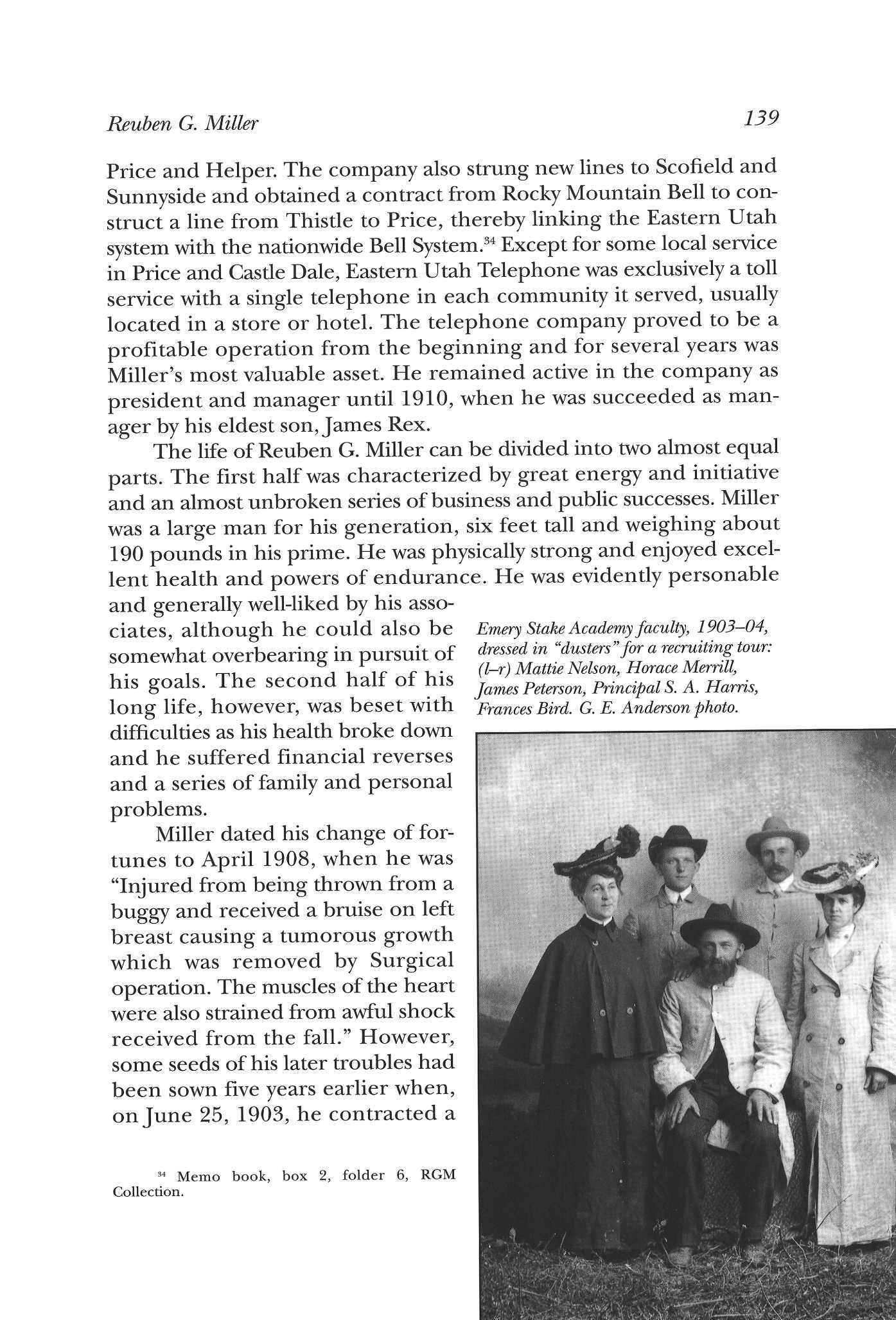

Probably impelled in part by a perception that the era of the big livestock operation was coming to an end and in part by his growing involvement in other activities, Miller disposed of most of his livestock in 1905 and sold his Carbon County ranches the following year to N. L. Nielson, a sheepman based in Mount Pleasant. The Winter House headquarters ranch was resold in 1907, primarily for its water rights, to the company that was developing the Hiawatha mine.33 Subsequently known as the Millerton Ranch, it is still held by a successor company With his ranching career at an end, Miller turned his attention to the fledgling communications industry. In 1890 the first telephone line in the region had been strung from Price to Huntington by the Price Trading Company and was later extended to other Emery County towns. Sometime after 1900 the Harmon Brothers, Levi and Oliver, acquired the line. In 1905 Miller and other Price investors bought the Emery County line from the Harmons for $3,775 and organized the Eastern Utah Telephone Company with both financial and technical assistance from Rocky Mountain Bell. The following year Eastern Utah Telephone purchased the government line between Price and Myton in the Uinta Basin and an independent line between

31 Liddell, "Cattle and Sheep Industry of Carbon County," 55

32 Eastern Utah Advocate, August 21, 1902

33 "Notes & bits of information used in making up replies to Mr Johnson," box 3, folder 4, RGM Collection; Emery County Progress, October 19, 1907

138Utah Historical Quarterly

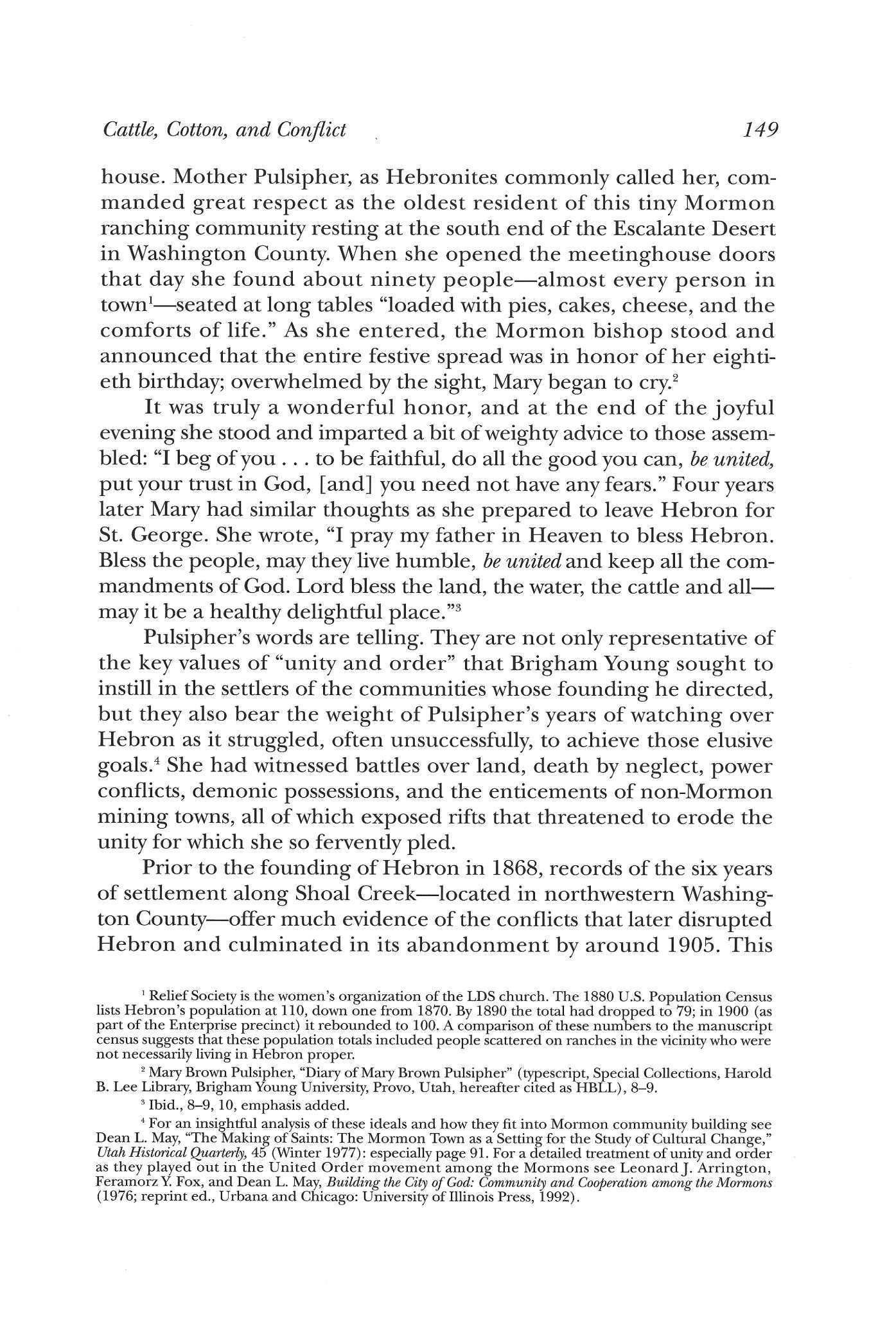

ReubenG. Miller139