36 minute read

It's All Downhill from Here: The Rise and Fall of Becker Hill, 1929-1933

It's All Downhill from Here: The Rise and Fall of Becker Hill, 1929-1933

By LEE SATHER

Ogden in the late 1920s was a city of more than 40,000 people. The second largest city in the state, it was prospering as the home of several of Utah's canning, construction, and banking interests and as a major hub for both passenger and freight railroad service. Local government officials and the chamber of commerce aggressively pursued projects that would promote the city and enhance the region's future, such as a new post office, lights for the city airport, a new athletic stadium in Lorin Farr Park, and a municipal golf course. 1

But city leaders also sought a tourist niche for the city. In an open letter to the community in late January 1929, P.J. Mulcahy, president of the Ogden chamber of commerce, proclaimed:

An unexpected opportunity developed almost immediately. In February 1929 several dog teams stopped briefly in Ogden on their way from races in Trucker, California, to Ashton, Idaho. Their owners intrigued local officials with the prospect of Ogden's joining a race circuit that might bring 50,000 spectators to the city. In June, convinced by the idea, the chamber decided to establish a winter sports program featuring dog team races and ski jumping contests. Wilbur Maynard was an influential figure in shaping this decision. Maynard, who had lived in Ogden but was then living in Truckee and was a prominent figure in the Truckee—Ashton dogsled races, had visited Ogden in June to promote the winter program and to explain the benefits that Truckee enjoyed from hosting these events. 3

In early September the Ogden chamber officially joined with Truckee/Lake Tahoe and Ashton to sponsor dogsled races and ski jumping competitions during the winter months. The group then formed a "winter sports program committee, which included sixty influential Ogdenites and several state leaders, to plan Ogden's participation. G. L. (Gus) Becker agreed to chair this group. A prominent local businessman, he was head of the Becker Products Company, which before Prohibition had been a leading local brewery; thereafter it had been forced to rely on its soft drink products. He was also an accomplished sportsman and nationally recognized trap-shooter. Becker expressed the group's optimism when he observed:

The committee first turned its attention to the construction of the ski jumping hill. Wilbur Maynard was very likely instrumental in the selection of Lars Haugen as the chief consultant for this project. A native of the Norwegian county of Telemark, Haugen had immigrated to the United States in 1909 with his brother Anders and had won the U.S. national amateur ski jumping championship seven times; his brother had been a member of both the 1924 and 1928 U.S. Olympic ski jumping teams. 5 Haugen and Maynard visited both Ashton and Ogden in late summer to select sites for ski jumping hills. Originally, Ogden officials had assumed that their hill would be located in Huntsville, but Henry Beckett, Jr., manager of the Hotel Bigelow, suggested the area then called Shanghai Flat. Haugen and the local committee members visited the site, located approximately three-tenths of a mile above the present Pine View Reservoir spillway on Highway 162, and agreed. 6

During the fall both local and regional plans moved into high gear. Representatives from the three cities selected Becker to lead the planning board, and Al Warden, sports editor of the Ogden Standard Examiner, was chosen as secretary. The group agreed that Lake Tahoe would hold its events on February 8 and 9, 1930; Ogden's events would take place the following week on February 15 and 16, and Ashton's dog derby would be run one week later. 7 Like Ogden, Tahoe built its first ski jump in preparation for the events. Ashton originally intended to build a ski jump but never did.

Becker and his committee rallied community support through a dinner for forty local leaders in mid-November. 8 A.V. Smith, owner of the El Monte Springs Resort, supervised construction of the ski jump during the autumn months. Built at an estimated cost of $2,000, it had a total length of 305 feet from the top to the takeoff; including the apron, or landing area, it was nearly 500 feet long. Upon completion, the jump -was immediately proclaimed the "longest ski jump in the world." Haugen, Maynard, and other program leaders optimistically predicted jumps of over 400 feet, far in excess of the then-current record of 229. To encourage such feats, the local committee offered a $2,000 bonus to anyone who broke the world record on Ogden's hill. 9 It is ironic that this venture, conceived when Ogden's "future prospects" seemed so bright, was actually carved out of the side of Ogden Canyon just as the "Great Crash" of 1929 initiated the Great Depression and one of the most serious economic and social crises of all time.

The organizing committee needed ski jumpers to make the competitions at Ogden and Lake Tahoe successful. Their timing, at least in this regard, could not have been better. Ski jumping, as "was true of most sports, had begun as a participatory activity and, at best, as amateur competition. Along with many others, this sport was affected by economic, social, and cultural changes in the late nineteenth century that allowed more people to enjoy far greater amounts of free time and leisure than ever before. The increased leisure led to the development of athletic clubs both in the United States and in Europe to promote sports and to organize and regulate competitive activity.

But these developments also tended to encourage professional competitions in which the ordinary individual became the spectator. It also led to the emergence of national athletic heroes on a much wider scale than before. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in baseball, Red Grange in football, and Jack Dempsey in boxing are but a few examples of these heroes during the 1920s. Both the newspapers and the relatively new radio stations helped to generate interest in sports competitions and attempted to meet the public's increasing demand for coverage of organized sports. Ogden—along with Salt Lake City—became a microcosm of this phenomenon with the advent of "big-time" ski jumping.

Skiing itself had been practiced in Northern Europe for millennia and was carried by Scandinavian immigrants to North America in the nineteenth century. Norway's major ski jumping event at Holmenkollen in Oslo "was first held in 1892 and immediately assumed international importance. In the United States, ski jumping spread from the East to the Midwest, the chief center of Scandinavian immigration in the 1880s. The first-known American jumping competition was held in Red Wing, Minnesota, in February 1887. Competitions soon developed in larger cities such as Minneapolis and Chicago, home of the Norge [Norway] Ski Club, and in lesser-known places such as Wanamingo, Minnesota; Canton, South Dakota; and Omaha, Nebraska. 10

In Utah, skiing as a popular and practical sport was common, particularly among miners and Scandinavian immigrants and their children. But it also attracted any child who could attach barrel staves to his feet for a brief downhill flight down one of Utah's many hills and mountains. Members of Salt Lake City's Wasatch Mountain Club, founded in 1912, regularly enjoyed ski outings. Likewise, in Ogden, members of the Bonneville Hiking Club enjoyed outings during the summer months and presumably during the winter as well. In 1915 the Norwegian Young Folks' Society began to organize frequent ski jumping contests for its members. In 1929 this society changed its name to the Utah Ski Club to attract a broader base of support, and it helped construct a ski jump on Ecker Hill, at Rasmussen Ranch in Parley's Canyon east of Salt Lake City. Thus, Ogden's experiment possessed a ready audience among Salt Lakers as well. 11

In the Midwest several local ski clubs created the National Ski Association in 1905 to organize amateur championships. The association demanded that participants in its competitions be amateurs; this rule later preserved the competitors' eligibility for participation in the Winter Olympic Games first established in 1924. As Becker Hill was being constructed, however, fourteen jumpers, including twelve Norwegians, bolted the group to form the professional American Ski Association. 12 Ogden had found jumpers for its new hill. Wilbur Maynard and Lars Haugen were clearly most responsible for recruiting these skiers for the trip west. Maynard, although not a competitive skier himself, attended the American Ski Association's first meeting in Minneapolis in November 1929, and veteran jumper Haugen was one of its most respected members. 13

The two men very likely recommended that Ogden hire one member of this group, Halvor Bjorngaard (as he spelled it in Norway), as Ogden's "own" professional. Bjorngaard agreed in November to become the director of the Ogden Ski Club's winter sports activities and to represent the club and Ogden in the Lake Tahoe and Ogden competitions. Originally from Hegra, Norway, Bjorngaard had immigrated in 1924 to Wanamingo, Minnesota. Although technically an amateur, he had probably derived most of his living from ski jumping, at least during the winter, since 1926. As a representative of the Aurora Ski Club of Red Wing, Minnesota, he had established a reputation as a first-class skier noted particularly for his graceful style. 14

When Bjorngaard arrived in Ogden in early January 1930, he immediately embarked on his Ski Club duties. The club had been organized in late November 1929 to foster popular participation in winter sports and, very likely, to stimulate interest and support for the winter sports program. Al Warden, selected as the group's first president, served as an important link to the sports program committee. The club hoped to secure 1,000 members and provide ski lessons for members and all interested youth in the region. As a start, it had planned an amateur winter sports festival for local citizens for February 8 and 9, one week before the Wasatch Dog Derby and the professional ski jumping competition. 15

Bjorngaard responded enthusiastically to the club's charge. He conducted skiing and skating classes on -weekday afternoons and all day Saturdays and Sundays at the club's El Monte Springs headquarters at the mouth of Ogden Canyon. A large skating rink, a toboggan run, and an amateur jumping hill were located there. Bjorngaard also toured schools in the Ogden area to promote youth participation in the club's sports programs. As Will Bowman from the Standard Examiner staff reported:

The Norwegian skier also prepared the jumping hill for its first winter season. A lack of snow early in January 1930 caused some concern, but Bjorngaard optimistically predicted that someone would exceed the ! unofficial world's record of 240 feet or the recognized mark of 229 feet. 17 On Sunday, January 19, some 3,000 spectators braved a swirling snowstorm to attend inaugural ceremonies in which the jumping hill was christened Becker Hill to honor G. L. Becker for his leadership of the winter sports program. Despite the weather, Bjorngaard thrilled the crowd with a single leap of 176 feet, although he fell while landing and suffered head cuts. Four amateur jumpers from the Utah Ski Club in Salt Lake City then closed the day's activities with jumps as well. 18

The presence of jumpers and officials from the Salt Lake City ski club provided the Ogden committee with the opportunity to solicit support from the capital city. The preceding week, the Ogden chamber of commerce board of directors had hosted their Salt Lake City peers, and Becker presided at a dinner on the 19th for Martinius Strand and P. S. Ecker, the main leaders of the Utah Ski Club, as "well as for Salt Lake City journalists "who had covered the jumping exhibition that day. 19

These efforts soon had the desired response, for within a "week the Salt Lake City chamber of commerce agreed to sponsor an entry in the season's dog races. Moreover, the Tribune's coverage of winter sports, particularly Ogden's upcoming winter festival, increased dramatically after mid- January. 20 Officials of the Utah Ski Club also redoubled their efforts to improve the newly constructed ski jump in Parley's Canyon. /Although not as long as Becker Hill, the jump was said to be steeper, and ski club officials made minor alterations in January so that jumps there would equal those at the Ogden site. The club had planned to host the state amateur ski jumping championship at the Parley's site in late February but changed the date to March 2 so that the professional jumpers could also compete after the end of their regular season. The hill was officially named Ecker Hill on that occasion. 21

In Ogden, Al Warden, sports editor of the Standard Examiner, provided local readers with a steady stream of stories on Lake Tahoe's festivities in early February and on the organizing committee's plans for Ogden's Wasatch Dog Derby and the ski jumping competition. Earlier, he had quoted Wilbur Maynard's praise of Ogden's hill and ski jumping in general:

The jumpers had completed their first weekends as professionals with events in Detroit and then Omaha before setting out for Ogden. The troupe arrived on Tuesday, February 11, and practiced on Becker Hill for the remainder of the week while final touches, such as the judges' stand and space for the press, were added. The two-day program was arranged so that the dog teams would race a 25-mile course on the mornings of both Saturday and Sunday. Ski jumping competitions would take place on both days at 2:30 p.m. Daily admission was set at a dollar for adults and fifty and twenty-five cents for children. The canyon would be closed to automobiles for the weekend; special buses and electric car service were mobilized instead. 23 This was a major event for the Junction City.

The first-place prize money for both the dog derby and the ski jumping was a princely (particularly with the onset of the depression) $1,250; second place was worth $750; and $500 was reserved for third. As advertised, the $2,000 offered for a world record gave ski jumpers an added incentive to do well. As Sverre Engen noted later:

Thirteen jumpers participated in the first professional event at Becker Hill: Sigurd Ulland, Alf Engen, Sverre Engen, Lars Haugen, Oliver Kaldahl,

Steffan Trogstad, Bert Wilcheck, Halvor Hvalstad, Einar Fredbo, Alf Mathisen, Carl Hall, Ted Rex, and Ogden's Halvor Bjorngaard. Mathisen also represented the Ogden Ski Club in the events of that weekend and the remainder of the season, and both he and Bjorngaard sported distinctive red sweaters with the club's name emblazoned in white letters across the front.

Warm afternoon temperatures on Saturday, February 15, made the snow extremely soft, however, and the distances recorded by the jumpers were much shorter than expected. Ulland won the first day's competition with a best single leap of 118 and best total of two with 220. Alf Engen, who had immigrated to the U.S. about six months before, was second with jumps of 100 and 113 feet. His brother Sverre was third and Bjorngaard fourth. 25

Again on Sunday, no new records "were established. Program officials and jumpers had worked far into the night between the jumping sessions to improve conditions, but the snow remained soft and -wet and again slowed the jumpers down. Sig Ulland "won the event again. Alf Engen held on to second place, while Lars and Anders Haugen moved into third and fourth, respectively. Bjorngaard finished sixth after having broken a binding but not falling.

Although no crowd estimates were given for the competition, Becker and chamber officials judged the entire event to be a great success. Earl Kimball swept both legs of the Wasatch Dog Derby in record time. Thula Geelen, one of the two women entered in the thirteen-sled competition, was second. On Sunday evening Becker hosted a sumptuous banquet, apparently at his own expense, for more than ninety people involved in the weekend activities: participants, officials, and other guests. 26 In the weeks that followed, Bjorngaard and Mathisen competed in the Lake Tahoe tournament and then at the opening of Ecker Hill. The distances recorded at Ecker were similar to those of February's event at Becker Hill. 27

The public's increased interest in winter sports—professional, amateur, and participatory—paid off, and Becker Hill's first season was by any standard a tremendous success. On the one hand, the ski jumping competition provided Ogden with much greater publicity than before; it also encouraged Ogden's tourist trade for at least a few days in the winter. Merchants apparently sold more skis and other winter sports equipment than ever before, which was particularly remarkable since the depression had already impacted both jobs and pocketbooks. 28

But an unexpected bonus was the permanent appeal this region acquired for many of the Norwegian ski jumpers. Though they had settled at first in the Midwest, they now began to be attracted to the West. According to a Salt Lake City reporter,

Bjorngaard and Alf Mathisen had decided very early to remain in Ogden for the summer. 30 Both played during the summer on the Ogden soccer team that won the state championship, and Bjorngaard received all-state honorable mention that season for his play. 31 Their presence gave added significance to the local team's matches against the Vikings, a Salt Lake City team comprised mainly of Norwegians and featuring many of the same ski jumpers, such as Fredbo, Hvalstad, and the Engen brothers, against whom Bjorngaard and Mathisen had competed during the winter and who had indeed stayed in the area during the off-season. 32

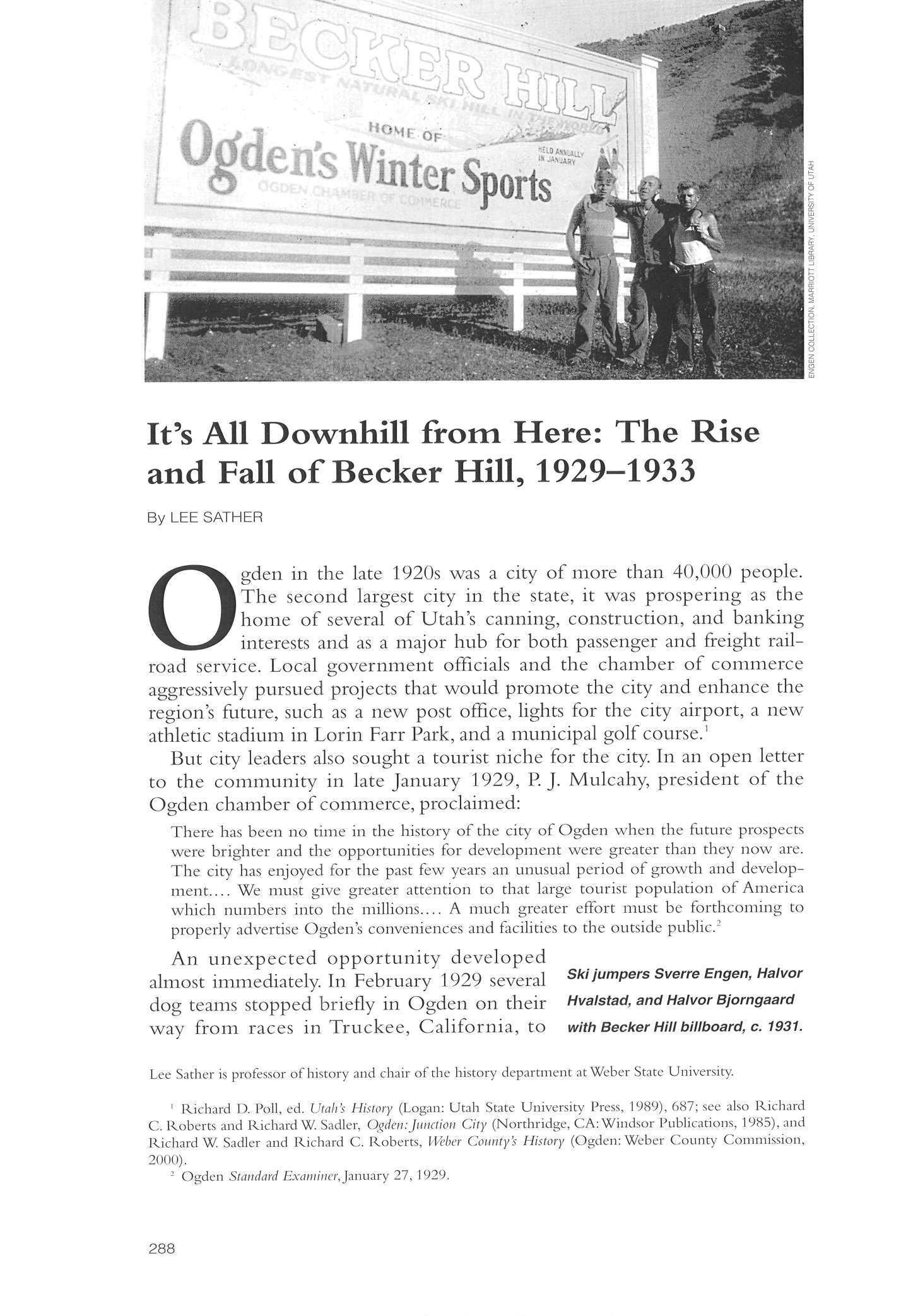

Bjorngaard was employed locally as a mason but also spent several weeks working on Becker Hill. In either the summer of 1930 or 1931 he had the assistance of Lars Haugen, Halvar Hvalstad, and Sverre Engen. According to Sverre:

Because of, or perhaps despite, these trips to the still waters, considerable improvements were made on the hill during the summer of 1930, including wooden steps installed alongside the jump. However, it was not until mid-December 1930 that work on the takeoff area was undertaken. 34 Once the winter snow arrived in mid-December 1930, Bjorngaard enthusiastically resumed his duties with the Ogden Ski Club. He provided ski instruction to schoolchildren during the week, worked with children and adults at the reservoir on Saturdays, and did the same in Huntsville on Sundays. 35

In the meantime, plans for Ogden's winter sports program for 1931 were being made. E. R. Alton, immediate past president of the Ogden chamber of commerce, assumed an increasingly important role by becoming tournament manager. The cooperation among Ogden, Tahoe, and Ashton took a more organized approach when the consortium was renamed the Western America Winter Sports Association. Los Angeles, with its Big Pine resort some ninety miles from the city, was accepted as a new member of the group. Becker remained president of the association, and Warden continued as secretary. Ogden, Tahoe, and Los Angeles would offer both a dog derby and ski jumping, and Ashton, as before, would continue to sponsor its American Dog Derby. 36 Dates for the activities were also changed so that Ogden began events at its winter carnival on January 23 and 24, with the others following afterwards. The local committee decided to reduce daily admission prices for Ogden's events to fifty cents for adults and ten cents for children, a price drop very likely influenced as much by the depression as by the desire to draw more spectators. 37

Prior to the main winter festival, several jumping competitions were held to test the "perfected" hill and to stimulate spectator interest. Bjorngaard and Mathisen both participated in a New Year's Day jumping competition at Ecker Hill. Bjorngaard placed second in that event, which Alf Engen won with an unofficial world record leap of 247 feet. On January 4 Alf and Sverre Engen, other Salt Lake jumpers, and an estimated 8,000 spectators attended an exhibition performance by Bjorngaard and Mathisen at Becker Hill. Bjorngaard reportedly recorded one jump of 201 feet as well as others of 155 and 185—all considerably beyond those of 1930. 38

One week later an estimated 2,000 spectators braved a "winter snowfall to observe both professional and young skiers perform. For youngsters, cross-country ski races and ski jumping contests were held on a practice hill erected east of the main hill. Bjorngaard, Mathisen, the Engen brothers, and Einar Fredbo all assisted in these activities. Because of the poor visibility, only Bjorngaard and Alf Engen actually jumped that day from Becker Hill. Engen jumped 195 feet on his first jump but fell on his second. Bjorngaard, however, recorded a leap of 190 feet and then followed with one estimated at 201 feet.

Despite the optimism these jumps created, the distances recorded during the two-day skiing competition held on Saturday and Sunday, January 24 and 25, were disappointing. Approximately 5,000 spectators did attend the ski jumping events each day. Alf Engen won both days, with Einar Fredbo placing second and Bjorngaard third. Engen recorded jumps of 200 and 199 on Saturday but only jumped 181 and 190 feet on Sunday. The consistently longer jumps on the first day reflected the dramatic change in snow conditions from Saturday to Sunday. On Saturday the snow was reported to be somewhat soft, with windy conditions causing some concern. On Sunday, however, the course -was extremely icy. The ice not only led to shorter jumps but also caused injuries to Mathisen and Fredbo. 39

The spotlight given to both the dog derby and ski jumping meant that local newspaper readers were likely to follow performers in these sports through the remainder of the "winter season. Ski jumping, however, garnered greater attention and newspaper space. This "was certainly due in part to the success and legendary status that Alf Engen began to establish in the sport. But in 1931 Bjorngaard, Ogden's "own" professional, was also extremely successful. The Standard Examiner, therefore, promoted upcoming competitions as two-man duels of heroic proportions. On February 1 the newspaper headlined a story "TWO JUMPERS COMPETE FOR SKI GONFALON: Engen and Bjorngaard To Settle Argument Today At Los Angeles." Engen won that two-day event and set an official world's record of 243 feet. The following week, the skiers moved to Lake Tahoe, and the Standard proclaimed on February 7, "ALF ENGEN IS FAVORED TO WIN NATIONAL SKI TITLE: Lake Tahoe Classic Draws Throng; Ogden Performer Is Threat." In fact, over the three competitions that comprised the "national" professional circuit, Bjorngaard finished third at Becker Hill, fifth at Big Pines (Los Angeles), and fourth at Lake Tahoe, 300 points in all behind Alf Engen for second place but 27 points ahead of Sverre Engen. 40

Conditions on Becker Hill during both days of the 1931 meet, wet and soft on Saturday and dangerously icy on Sunday, indicated that fundamental problems existed with the hill. The course had a south-facing exposure, and it lay in the afternoon sun of the canyon. This essentially guaranteed that conditions on the hill could never be the best possible for jumping. 41 The jump's orientation was certain to raise safety concerns and consequently affect the competitors' "willingness to compete on the hill. On the other hand, Salt Lake ski officials had made significant alterations to Ecker Hill prior to its second season, making much longer leaps, including Engen's in early January, possible.

Ogden winter sports officials were aware of Becker Hill's shortcomings, though traffic in Ogden Canyon may have been their primary concern at first. After the first winter sports program of February 1930, suggestions were made to relocate the hill much closer to Ogden and thus eliminate the traffic problems. In late January 1931, not long after the major ski jumping events of the season had ended, reports developed that a new hill at the top of Taylor's Canyon was being considered to replace Becker Hill. Bjorngaard and other jumpers examined this site as well as others near Huntsville. At some point, a decision was made to proceed on the Taylor's Canyon site, for Bjorngaard was scheduled to begin work on this project in mid-June. 42

He never did so, however, for he was killed on June 6 in a traffic accident. After having spent much of the day with Sverre Engen, Bjorngaard left Ogden for Brigham City. At approximately 10:30 p.m. his motorcycle collided head-on with an automobile in Pleasant View, about one mile east of the intersection of Highway 89 and Pleasant View Drive. Both vehicles were traveling at excessive rates of speed, but later investigation revealed that the driver of the automobile was in the wrong lane of traffic at the time of the collision. Ironically, the driver of the other vehicle was the brother of the young woman in Brigham City whom Bjorngaard was traveling to visit. 43

Bjorngaard's death stunned the city. One week later, his funeral in Ogden was held at the large Ogden Tabernacle, very likely because of the expected number of mourners—but the choice of location was nevertheless remarkable since he had lived in Ogden less than eighteen months. E. R. Alton and G. L. Becker both spoke, as did his skiing and soccer comrades. The coffin was covered with flowers and a crossed pair of jumping skis. 44 Afterward, his remains were shipped to relatives in Wanamingo, Minnesota, for services and burial there.

Al Warden, whose son had participated in ski jumping contests, wrote two days after Bjorngaard's death:

It is fair to say that the ski jumping program at Becker Hill never recovered from his death. Ski club and ski jump tournament officials attempted to find a replacement during the summer, but by late autumn the position was still not filled. Both Einar Fredbo and Sverre Engen had applied for the job, and when Fredbo "withdrew from consideration, local officials were confident in early December that Engen would accept their offer of employment. 46 Negotiations floundered, however, and the post was not filled. Ted Rex and Steffan Trogstad, both regulars on the professional circuit, represented Ogden on the ski jumping circuit during the winter 1932 season but did not perform the local duties previously carried out by Bjorngaard. Moreover, plans to replace Becker Hill were also apparently shelved after his death. Thus, only minor changes to the hill's takeoff were made in preparation for Ogden's tournament in January 1932.

Other changes to the jumping circuit and Ogden's own winter program were made before the season began. The dates for the Wasatch Dog Derby and the ski jumping events were separated so that the dog derby was scheduled for February and the ski jumping competition slated for January 9 and 10. These dates coincided with Ogden's annual Livestock Exhibition, one of the most important regular tourist events of the city. 47

Bad luck continued to plague the ski jumping competition on Becker Hill as a heavy snowstorm on Saturday, January 9, forced cancellation of the first day's jumping by the professionals, although a jumping contest for more than one hundred young Weber County contestants was completed on the nearby practice hill. On Sunday 3,500 spectators watched six professionals complete their jumps, but "soft and sticky" snow caused the jumps to be relatively short. Alf Engen won the competition for the second straight year with four jumps that varied from 136 to 150 feet. Ted Rex and Trogstad, representing Ogden, finished fifth and last. 48

Unlike in earlier years, the ski jumping competition in January seemed to bring an abrupt end to activity on Becker Hill.The Ogden area enjoyed noticeably more snow than it had in previous years, thus permitting the Wasatch Dog Derby to be run near Ogden's old airport. Junior ski activity continued, with relatively large numbers competing in cross-country and junior ski competition held in conjunction with the dog races. But those activities were held close to Ogden. Although Rex and Trogstad represented the city on the professional circuit, local interest in ski jumping was fading rapidly, if coverage in the Standard Examiner is any measure.

One year later, arrangements for the 1933 ski jumping season seemed much more hurried and certainly much lower-key than before. There was renewed hope that Sverre Engen might accept the Ogden Ski Club's offer to direct its winter sports program, but again recruitment efforts failed. There may well have been some uncertainty whether Becker Hill would even be ready for the annual professional ski jump competition. The chamber of commerce and the Ogden Ski Club had acquired land along Ogden's east bench for cross-country skiing, tobogganing, and ski jumping, and they spearheaded construction of two ski hills at the top of 29th Street, near the mouth of Taylor's Canyon. They built another jump much further south and a fourth near the northern boundary of the city. The Ogden City-Weber County Relief Committee provided labor for the projects. 49

Preparations for the professional show may also have been hampered by indecision regarding the date of the event. Organizers were only certain in the last days of December that the competition would take place on Sunday, January 8, 1933. This obviously gave organizers little time to make adequate preparations for the event. The competition was also cut back to a single day, there was much less fanfare in the press, and only eight jumpers participated. After the group of jumpers participated in the traditional New Year's Day event at Ecker Hill, they traveled to Ogden to prepare the hill for competition. There is no record that any work had been done on the hill since the year before, but Lars Haugen, the venerable captain of the jumpers, pronounced the eighteen inches of snow on the course to be sufficient and said that the hill was in "perfect shape." 50

Alf Engen again won the ski jumping competition as 1,500 spectators watched his official leaps of 168 and 167 feet. TAlthough conditions were said to be "ideal," soft, sticky snow again plagued the event and led to shorter jumps—not the type of leaps that were becoming commonplace at other venues. For example, Halvor "Dynamite" Hvalstad had bested Engen on Ecker Hill the week before with a leap of 236 feet. 51

This competition proved to be the last hurrah for Becker Hill. No written evidence on the hill thereafter has been found. It has generally been assumed that the construction of Pineview Dam was the basic cause of Becker Hill's demise. This project entered its initial stages in autumn 1933, and construction began in 1934. However, it is much more likely that the hill disappeared in 1933 because of the liabilities associated with its location and that it would not have remained in use under any circumstances. It is also very likely that the magnitude of the depression made it increasingly difficult, despite the best efforts of Becker, Alton, and Warden, to mobilize the financial support necessary to maintain the hill or support a major professional event. Finally, Bjorngaard's death was extremely important, particularly when the group could not find a replacement. The man had been a genuine hometown hero. He combined a colorful personality with a genuine commitment to the promotion of his sport and the requisite talent to compete on even terms with his professional peers.

Although Becker Hill thus slipped silently away, the Ogden Ski Club, or Sports Club as it was later called, continued to promote winter sports activities in the Ogden area. The group sponsored a very successful junior ski jumping tournament in January 1933 at a new ski jump at the mouth of Taylor's Canyon. 52 Later that year, the club also prepared the second ski jump at Taylor's Canyon for professional competition. A two-day tournament, along with the official dedication of the jump as Bjorngaard Hill, was scheduled for the weekend of January 6—7, 1934, but lack of snow forced cancellation of the meet. Similar conditions derailed a meet scheduled for one year later in January 1935. 53

On January 11, 1936, the competition and dedication of the hill were finally held. Once again, however, weather conditions played havoc with the event. Although Ogden had been blessed that winter with relatively large amounts of snow, rain prior to and during the jumping contest reduced the number of competitors to four professionals and seven amateurs. It also forced the jumpers to use a lower takeoff point, which limited John Elverum's winning leaps to 108, 109, and 112 feet. Alf Engen made jumps of 116 and 120 feet but declined to make a third attempt because of the poor weather conditions. In contrast, Engen won an Ecker Hill competition one week later with jumps of 227 and 224 feet. 54

Ogden's first efforts to promote professional winter sports thus ended with this futile and frustrating effort to maintain the legacy established at Becker Hill. The opportunities that seemed so promising in early 1929 -were certainly affected greatly by the onset of the depression. Also Becker Hill's location created problems that its builders "were unable to correct, and a suitable replacement could not be found—especially not right on Ogden's doorstep. But the venture had its positive sides as well. A clear connection exists between Becker Hill and the much more successful ski resorts that developed on the higher eastern slopes of the Wasatch Mountains later on. With the more reliable snow conditions there, Snow Basin, Powder Mountain, and Nordic Valley would prosper as they became more accessible to the public.

Finally, many of the small corps of ski jumpers who first arrived at Becker Hill in 1930—Bjorngaard, the Engen brothers, Einar Fredbo, and Steffan Trogstad—remained in the state and left their mark upon it. The Engens, in particular, played a major role in the development of downhill skiing as a popular sport for many Utahns and in the development of the ski resort industry. But this group also represents the tendency found after this date for an increasing number of Scandinavians and Scandinavian Americans to settle in Utah, both for the job opportunities and out of love for the mountains and outdoor opportunities that the state offers to its citizens.

NOTES

Lee Sather is professor of history and chair of the history department at Weber State University

1 Richard D Poll, ed Utah's History (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1989), 687; see also Richard C Roberts and Richard W Sadler, Ogden: Junction City (Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1985), and Richard W Sadler and Richard C. Roberts, Weber County's History (Ogden: Weber County Commission, 2000)

2 Ogden Standard Examiner,January 27, 1929

3 Ibid., February 15, June 16 and 24, 1929.

4 Ibid., September 5, 9, 10, 1929.

5 Ibid.,June 16,August 17, 1929

6 Salt Lake Tribune, October 19, 1929; interviews by author with Keith Rounkle, June 19, 2001, Ralph Johnston, June 23, 2001, Arthur Nylander, June 22, 2001, and Robert Chambers, July 31, 2001 (tapes of interviews are in author's possession); Standard Examiner, September 5, 1929.The Hotel Bigelow is the present Ben Lomond Hotel Becker Hill is now largely under the waters of Pine View Reservoir

7 Standard Examiner, October 2, December 18, 1929

8 Ibid., November 24, 1929

9 Ibid., October 31, November 14 and 15, 1929; Roberta Cartwright, "Guys like Gus: Ogden's Basin Goes Big-time," Western Skiing, Dec 1945, 16 (copy in G L Becker scrapbook #2, 150, Ogden Union Station Archives)

10 Alan K Engen, For the Love of Skiing: A Visual History (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publishers, 1998), 1-20.

11 Ibid., 21-30;Alexis Kelner, Skiing in Utah:A History (Salt Lake City: A. Kelner, 1980), 43-51.

12 Engen, For the Love of Skiing, 19; Standard Examiner, November 27, 1929

13 Standard Examiner, November 11, 1929.

14 StjordalsNytt (Norway), December 28, 2000 I am indebted to Mr Howie Arnstad for calling my attention to this article.

15 Standard Examiner, November 24 and 25, December 10 and 21, 1929.

16 Ibid., January 26,1930.The El Monte Springs site is presently called Rainbow Gardens

17 Ibid., January 7, 1930; Salt Lake Tribune, January 5, 1930

18 Standard Examiner, January 20, 1930; Salt Lake Tribune, January 20, 1930.

19 Salt Lake Tribune, January 15, 19, 20, 1930

20 Ibid., January 26, February 2 and 9,1930

21 Ibid., January 27, February 9 and 10, 1930

22 Standard Examiner, November 11, 1929.

23 Ibid., February 11, 12, 14, 1930

24 Sverre Engen, Skiing, a Way of Life: Saga of the Engen Brothers: Enterprises, 1976), 40

25 Standard Examiner, February 16,1930.

26 Ibid., February 15, 16, 17, 25, 1930. See also a draft of Becker's report to the Ogden chamber of commerce, February 24,1930, Becker scrapbook #1 , 99, Ogden Union Station archives

27 Standard Examiner, March 3, 1930

28 Draft of G L Becker's report to the Ogden chamber of commerce, February 28, 1931, Becker scrapbook #2 , 105

29 Salt Lake Tribune, March 4, 1930

30 Standard Examiner, February 6, 1930

31 Ibid., March 6, 1931

32 Ibid., March 30, October 1, 1930.

33 Alan Engen, For the Love of Skiing, 31 For a somewhat different version of the same situation, see Sverre Engen, Skiing: A Way of Life, 45. Sverre dates this as the summer of 1931. Alan Engen places it within the context of the construction of Becker Hill in 1929

34 Standard Examiner, December 17 and 24,1930

35 Ibid., December 9, 19, 21, 1930

36 Ibid., October 13, November 3, December 18, 1930

37 Ibid.,January21,1931

38 Ibid.,January 2 and 5, 1931

39 Ibid., January 7, 12, 25, 26, 1931

40 Ibid., February 10, 1931

41 Rounkles, Johnston, Nylander, and Chambers interviews; Kelner, Skiing in Utah, 59

42 Salt Lake Tribune, February 25,1930; Standard Examiner, January 30, February 8, June 7, 1931

43 Standard Examiner, June 7, 8, 9, 10, 1931; Nylander interview.

44 Standard Examiner, June 10, 1931

45 Ibid.,June 8, 1931

46 Ibid Jun e 25, November 17, December 4 and 10, 1931

47 Ibid., December 13 and 31, 1931

48 Ibid.,January 8,10, 11,1932

49 Ibid., December 11 and 18, 1932.

50 Ibid., December 27 and 30, 1932January 4, 5, 6, 7, 1933

51 Ibid., January 1 and 9, 1933

52 Ibid January 22 and 23, 1933

53 Ibid.,January 4, 1934,January 2, 1935

54 Ibid.,January 12 and 19,1936