WINTER 2002 • VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 1

UTA H HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIA L STAF F

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN SMART ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISOR Y BOAR D O F EDITOR S

NOEL A CARMACK, Hyrum, 2003

LEE ANN KREUTZER,Torrey, 2003

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2004

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Murray, 2003

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora,WY, 2002

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 2002

JOHN SILLITO, Ogden, 2004

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 2002

RONALD G WATT, West Valley City, 2004

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information

Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20; institution, $20; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or older), $15; sustaining, $35; patron, $50; business, $100.

Manuscripts submitted for publication should be double-spaced with endnotes Authors are encouraged to include a PC diskette with the submission. For additional information on requirements, contact the managing editor Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

4 Utah Schools and the Japanese American Student Relocation Program By R

. Todd Welker

21 The Utah Writers' Project and Writing of Utah: A Guide to the State By Richard L

Saunders

39 Dorothea Lange's Portrait of Utah's Great Depression By James

R Swensen

63 Hecatomb at Castle Gate, Utah, March 8, 1924 By

Philip F. Notarianni

75 Senator Orval Hafen and the Transformation of Utah's Dixie By Douglas

D. Alder

92 BOO K REVIEWS

Morris A Shirts and Kathryn H Shirts A Trial Furnace: Southern Utah's Iron Mission.

Reviewed by Douglas D Alder

Samuel Nyal Henrie, ed Writings ofJohn D. Lee

Reviewed by Lawrence G Coates

William Wroth, ed. Ute Indian Arts and Culture: From Prehistory to the New Millennium.

Reviewed by Forrest S Cuch

Ronald W.Walker, David J.Whittaker, and James B.Allen. Mormon History.

Reviewed by Peter L Kraus

Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard O. Cowan, eds. Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History.

Reviewed by David A. Hales

Jan Shipps Sojourner in the Promised Land: Forty Years Among the Mormons.

Reviewed by Newell G Bringhurst

Polly Steward, Steve Siporin, C.W Sullivan III, and Suzi Jones, eds Worldviews and the American West: The Life of the Place Itself.

Reviewed by George H Schoemaker

WINTER 2002 • VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 1

2 IN THIS ISSUE

• COPYRIGHT 2002 UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

As this issue goes to press,Utah, in the thick of the Olympic Games,is trying to make good on the slogan coined for the occasion:"The world iswelcome here."The sentiment has great appeal;however,ifweplace itin ahistorical context we can see thatitissimplyonemoretrendinthestate'sevolvingrelationships between "insiders"and "outsiders." One example:During theJapanese American internment ofWorldWar II,the National Student Relocation Council askedcollegesaroundthecountry ifthey-wouldacceptstudentsofJapanese ancestry.OfUtah'sthreemajor colleges,twowelcomedtheNisei.The other saidno—andexpelledthosealreadyenrolled.Ourfirstarticleexplores these divergent decisions aswell as the students'experiences on campus and in Utah communities.

The"worldiswelcome"sloganispartofthetremendous efforts thathave goneintoimage-makinginpreparationfortheGames.Thisissuenext turns tohistoricalprocessesofimage-making.TheWriters'Project,afederal program that employed out-of-work writers and historians during the Great Depression,resultedinasetofstateguidebooks,including Utah: A Guide to the State. The guidewasmeant tomakeUtah attractivetotourists (andalso tomaketheWriters'Projectlookworthwhile) Butamostcompelling story liesinthepoliticsandbureaucratictanglesbehindthefinished book.

I N THI S ISSU E

Also during the depression,Dorothea Lange came to Utah with her camera and an agenda.As our third article explains, her wellknown 1930s photos of Utah do not necessarily reflect reality; instead, she created them as propaganda tools to garner support for federalfarmreliefprograms

Juxtaposed with the Lange images,aphoto essay on the Castle Gate Mine explosion of 1924 offers opportunity for further reflection on the hypothesis that every photo reflects an agenda Today's viewer cannot know -whether the photographer had a political purpose in mind, but the images certainly make a forceful statementeventoday

Last,we turn to aman who took up alifelong crusade to transform St.George both inimage andin fact.OrvalHafen worked onmany fronts towardhisgoalofmakingadestinationtouristattractionoutofthisagriculturaltown.Although the image he heldin hismind and communicated to othersdidnotaccomplishthisfeatalone,itplantedvitalseeds

Now,for the Olympic Games and beyond,Utah organizations continue to tweak—or recast—public images. Future historians will have the opportunity to set the Games,with their catchy slogans,banners, media events,and more,in the larger context ofevolvingpublic relations.In the meantime,readers ofthisjournal mayfind itinterestingindeed to compare thePR.goalsandchallengesoftodaywiththoseofpastdecades.

OPPOSITE:Madge

ABOVE:Springdale

ONTHECOVER:

Young Nielson, Widtsoe postmistress, photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1936.

family harvesting peaches, photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1938.

1941publicity photo for Utah: A Guide to the State The caption reads, "Walter Frese of Hastings House, Gwen Nolan, United Airlines stewardess, and William Henry Jackson, 98 years of age, pioneer photographer, at New York City airport. First copy of 'Utah Guide' was transported by plane and presented to Governor Maw." Jackson had driven abull train to Salt Lake City in 1867.

Utah Schools and the Japanese American Student Relocation Program

By R TODD WELKER

By R TODD WELKER

Utah has been recognized asan important site for the study of JapaneseAmerican relocation duringWorldWar II.A number ofscholarly works document the state's role in the evacuation story.Prominent among these works arehistories ofTopaz and theJapaneseAmerican CitizensLeague (JACL).1

However, atleast one aspect ofUtah's evacuation role hasnot received theattentionitdeserves,thatoftheinvolvementofUtahuniversitiesin the JapaneseAmerican StudentRelocation Program.Atatimewhen relatively fewgroupssoughttohelptheJapanese,anumber ofcollegesand universitiestookpartinthisprogram,thepurpose ofwhich-wastoopenthe doors ofcollege campuses throughout the nation to assistNisei (second-generationJapaneseAmerican citizens) in continuingtheirhighereducation.Recognized asthe Students at the University of Utah first step in resettlingJapanese Americans Park Building during the 1940s.

1 See Leonard J Arrington, The Price of Prejudice (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1962); Sandra C Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993); Roger Daniels, Sandra C.Taylor, and Harry Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991); Elmer R Smith, "The Japanese in Utah," Utah Humanities Review 11 (April-July, 1948)

R.ToddWelker is a graduate student in history at Utah State University He would like to thank Brian Q Cannon for making him aware of this topic and critiquing early drafts

after incarceration in the relocation centers,the program played a crucial part in alleviatingthe evacuationblow.Given theprogram'simportance,it is only natural that we explore the involvement of Brigham Young University (BYU), the University of Utah (U of U), and Utah State University,thenknownasUtahStateAgriculturalCollege (USAC)

Surprisingly little has been published on the matter, and most of the availablematerial isconfusing Scholarly works,including those by Roger Daniels,LeonardArrington, and SandraTaylor,exhibit anumber of discrepancieswithregardtotheinvolvementoftheU ofU andUtah Statein student relocation, and in none of them isBYU even mentioned. 2 It becomes difficult, therefore, to trace Utah's contributions to this program basedonexistingaccounts.Infact,thereisaninterestingstorybehind each school's decision either to open or close its doors toJapanese American students.This study seeks to relate the circumstances behind those decisions

Atthesametime,thisessayexplorestheissueofUtah'sdistinctive treatment ofJapaneseAmericans duringWorldWar II.In his article "Utah's Ambiguous Reception:The Relocated Japanese Americans," Leonard Arrington argues that in some ways Utah distinguished itselffrom other statesbydemonstrating unusualfavor toward theJapanese duringthe war. On theotherhand,herecognized evidenceofstatewideprejudice,suggestingthatUtahwasno different thantherestofthenation.3 The experience of Utah schools in the Student Relocation Program helps to solidify Arrington's argument,for it too is tinged with ambiguity.In some ways, Utah universities showed extraordinary favor toward theJapanese,and in otherwaystheyreflectedtheprevailingprejudices

Thereislittleambiguity,however,behindthebeginningsoftheJapanese American Student Relocation Program itself. Soon after Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066,groups that included students, educators, religious organizations, and theJapanese American Citizens Leaguebegan meetingvoluntarily to discussthefate ofNisei college students.After a series of conventions, and with the backing of the War Department,they gained official recognition from the federal government as the National Student Relocation Council (later changed to National JapaneseAmericanStudentRelocation Council) Basictasksofthe council included raisingfunds for students,distributing inquiries so that potential studentsmight obtain FBIclearance (aprerequisite to acceptance),visiting

2 Daniels's book Concentration Camps: North America (Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing, 1981) notes that "the state universities of Utah. .expressed almost immediate willingness to admit [Japanese] students," suggesting that both the U of U and USAC cooperated with program officials from the outset Arrington, on the other hand, makes it clear in The Price of Prejudice that the USAC and U of U turned down all Nisei applications beginning in 1942 but then began accepting them "in the late stages of the war." Taylor asserts in Jewel of the Desert that the University of Utah opened its doors to the Nisei from the beginning, while "the president of Utah State University.. refused them admittance."

3 Leonard J Arrington, "Utah's Ambiguous Reception: The Relocated Japanese Americans," in Daniels et al., eds.,Japanese Americans.

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

relocation camps to encourage Nisei enrollment, and convincing inland institutions to open their doors The council received "no financial assistance whatever from the government eitherfor operatingexpensesor for scholarshipaidtothestudents."Allexpenses, including salaries,were paid by voluntary contributors.4

BrighamYoung University demonstrated immediate willingness to further the efforts of the relocation council.Compared to the U ofU and the USAC,ithad an easy time indecidingtoopenitsdoorstotheNisei.In fact,verylittle deliberation,ifany,appear to have been necessary.The few remaining records of direct correspondence between the student relocation council and the administration at BYU reveal the decisionmakingprocess On September21,1942,the university began receiving letters from the council, to which President Franklin S Harris immediately responded:"For many years we have had afewJapanese students here and we shall be glad to have any of theminthefuture who areproperly recommended."5 Helaterwrote,"Weacceptallthe relocation students who are recommended, and they can enter at any time."6 Such was the policy of BrighamYoung University from the beginning.

Brigham

In addition to influencing administrative policy,Harris played a direct role in aidingmany prospectiveJapaneseAmerican students From March to December 1942,extensive correspondence between Harris and Nisei studentsattestedtohispersonalinvolvement Inoneletter,hereceived not only anadmittance request but alsoapleafor additional assistance.Calvin Harada wrote to Harris from theTopazRelocation Center on November 24,"Beingwithoutfunds atthetime,canyou find me ajob sothat Imay attend college?Ihaveamother and sister;mymother would liketo work inProvo,roomandboard,andearnmytuition,andmysisterwouldlike to attendsecondaryhighschool.Canyoufindajobformymotheralso?"

6 Ibid.,fldrK.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Young University president Franklin S. Harris.

4 Robert W O'Brien, The College Nisei (Palo Alto: Pacific Books, 1949), 60-67 For another comprehensive study of the experiences of the Nisei participating in student relocation, see Gary Y Okihiro, Storied Lives:Japanese-American Students and World War II (Seattle: University ofWashington Press, 1999).

5 Franklin S. Harris papers, box 92, folder M-MC, Brigham Young University Archives, Provo, UT.

Harrisrespondedafewdayslater:

We would be able to find part-time work at the University for you and your sister, but it is doubtful if we would have work for your mother However, there is a good deal of work for women here in town In fact, just this morning a friend of ours called wondering where we could get a Japanese woman to help for a few days I think the better thing for you to do would be for you to come here, and then you can look around for your mother.7

PresidentHarrisdemonstrated a-willingnesstogobeyondthemere acceptance process He was concerned not only with the students' ability to attendBYUbutalsowiththeirhavingthemeanstocompletetheirstudies Helen Shiozawa,aJapaneseAmerican who attended BYU during the war years,recognized Harris's influence in opening the school's doors to the Nisei.As a student from 1942 through 1945, she remembered, "PresidentHarriswasparticularlyopentotheJapanese.Ididn'tknow [that] untilIgotthereandthenIfound outthattherehadbeensome comments made at the faculty meetings about what they -weregonna do—because otherschoolshadclosedthedoorstoanyJapaneseAmerican students—and hesaidourschooliswideopen.AndIthinkthatmadeabig difference."8

Not onlydidPresidentHarrisopenlyaccepttheNiseibutevidencealso suggeststhatthestudentsatBYU didthesame.DonBowen submitted an articletotheuniversitynewspaper-whereinhedeploredthe "short-sighted bigotry"ofPresidentAtkinsonoftheUniversityofArizona,whorefused to allowwhat he called"the enemy"to enroll in U ofA extension courses "Such an attitude,"Bowen argued, suggested that "we throw out both Christianity anddemocracy...andhatethosewithwhom weareforced to fight...and who arepurelybycircumstanceassociatedwith [theenemy] Formyself,"he concluded,"Iamproud andhappythatIamprivileged to be amember ofaninstitution where the rational mantle ofreason is not substitutedbytheroguishgarments ofblindemotion,wherewe welcome, not shun ourAmerican brothers oftheJapanese race."9 Although Bowen's article represented the opinion of only one student, his use of the term "-we"suggests that he sawhimselfasaspokesman on behalfofthe entire studentbody.The institution asawhole,inhisview,shouldbepraised for thewayithadreceivedJapaneseAmericansintheirtimeofneed.

George Funatake's personal experience atBYU confirms the positive student response.LivinginPortland when thewarbroke out,George and his entire family were consigned to the Minidoka relocation camp in southern Idaho In 1944heattendedBYU for oneyearbefore enlisting in

7 Ibid.,box91,fldrH

8 Helen Shiozawa, telephone interview with author, December 27, 1999, Ogden, Utah; notes in possession of author.

9 "Scribe Lambasts Arizona U President for Jap Stand," White and Blue, December 4, 1942 It is ironic that the article speaks of welcoming the Japanese but that the headline writer uses the discriminatory term "Jap" in the title. This usage seems to have been a common occurrence, and it demonstrates how kindness and prejudice did coexist

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

thearmy Although notamember oftheMormon faith,Funatake recalled goodtimes-whenhethoughtofhisshortstayattheLDS-owned university: There were a bunch of us in this professor's home This professor had rooms made in his basement, you know, partitioned off There were quite a few of us; there were. .dischargees and some going in like me, so we were a mixed group I don't know if that John Christiansen is still around, but he was a blind guy going to school and we took him up to that big "Y," you know, on the hill I can still remember that.10

When asked about hisBYUexperience, Funatake first thought ofthe times hehadspent with fellow students He seemed to have interacted quite naturally with those around him,especially -with those notof Japanese descent "There were afew [Japanese students] I remember there were acouple ofbrothers from the Oakland area...but I can't remember anyof them by name. I always associated not with the Japanese...so it felt normal to me."11 Funatake's easy acceptance into non-Japanese social circlessuggests that thestudents played arole in contributingtothesuccessoftheschool'sopendoorpolicy.

ThefacultyatBYU-wasalsopraisedforhavingtakenaspecialinterestin the Nisei.SeichiWatanabe arrived attheschoolin1942.Ofhistwoyears there,herecalledwith gratitude thepositiveroleoftheprofessors inshapinghisexperience:"Ihavetremendous respectforthemembers ofthe faculty Alloftheprofessors that Istudied under were excellent educators to begin with,andthey-werevery helpful tous.Ithink they realized that wewereinabadsituation,andIcouldfeelthattheyweretryingtobenice tous Ithinkthey understood."12

In the final analysis,theuniversity emerged asoneofthemost active participants in student relocation during theheart ofthewar.In1943, nearly fortyJapaneseAmerican students were enrolled,placing theschool behind only four other U.S.institutions with regard tooverall numbers.13 Furthermore,"agroup of300 U.S Army privates arrived attheschoolon July 1,1942to complete theArmy Specialization Training Program." On-campus military training could haveprovided theadministration with a"goodexcuse"tolimitorevendenyadmittancetotheJapanese,especially sincealackoffacility spacehadalreadycreatedproblems.14 Butthereisno evidence suggesting that these circumstances influenced the administration's posture toward theNisei, andeven ifthey were considered,the school never didmodify itspolicy ofunlimited enrollment forJapanese Americans.

Perhapsthemost obviousreasonwhyBYUresponded the-wayitdidto

10 George Funatake, telephone interview with author, December 27, 1999, Portland, Oregon; notes in possession of author

11 Ibid

12 Seichi Watanabe, telephone interview -with author, December 27, 1999, Hilo, Hawaii; notes in possession of author

13 O'Brien, The College Nisei, appendix.

"Ernest L.Wilkinson, ed., BrighamYoung University: The First One Hundred Years, 4 vols (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:392

the plight of the Nisei was the influence of BYU student photos in the 1944 President Harris Not only did he play a Banyan (BYU'syearbook,page directroleinestablishingadministrativepolicy 21y but he also became personally involved in helping the Nisei Even yearsbefore hispresidency,he had spent time in JapanrecruitingforBYU Asaresult,thefirststudentstoattendtheuniversity from outsideNorthAmericaweretwoyoungmenfromJapan.In addition, Harris made trips to theTopaz relocation center to help "solve various social and educational problems" and oversee the implementation of certain programs at the camp. 15 By personal example,he prepared the groundwhereBYU'sopendoorpolicycouldtakeroot.

Perhapsinanindirectway,theinfluence oftheChurchofJesusChrist of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon), which owned and operated the school,may have also contributed to BYU's positive reception. Leonard Arringtonnotesthat"thepreservationofpeculiar [Mormon]values caused theLatter-daySaintstoadmirenationsandpeopleswho,liketheJapanese, were attempting the same." Furthermore, "ties had been established between key Utah leaders and theJapanese people after the Mormons establishedaproselytingmissioninJapanin 1901."Infact,HeberJ.Grant, who led the first LDS mission toJapan,acted aspresident ofthe church duringWorldWarIIAdditionally,oneofthestate'smoreprominent politicalofficials atthe time,seniorU.S senatorElbertDThomas,wasaleader within the Mormon church and had served a church mission toJapan.16

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

Felice Kartchner

Home Town: Flagstaff, Arizona Major: Musk

Jack S Ka+o Home Town: Provo, Utah Major: Soils

Romola King Home Town: Provo Utah Mojor: Sociology

Virginia Knowlton 1 Home Town; Holtadav, Utah : Major: English

:;'

Benjamin S Kuraya Home Town: Honolulu Hawaii

h Major: Music

Kathleen H Layton Home Town: Loyton Utah Major: Foods

15 Ernest L. Wilkinson and W. Cleon Skousen, Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny (Provo: BrighamYoung University Press, 1976), 254-55; White and Blue, May 1943.

16 Arrington, "Utah's Ambiguous Reception," 92—93

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Suchfactorsmayhaveaffected,forgood,theBYU environment

SeichiWatanabe and George Funatake, although not members of the LDSchurch,recognized theimportance oftheMormon influence "I have ahell ofalot ofrespect for the Mormon people,"Watanabe commented, "because they are allMormons over there...and Iwas treated very well." Similarly,Funatake remarked,"I got along great.And we werejust such a small group of guys... Yeah, alot of those guys were Mormon.. from southernUtahandfrom Idaho."17

But to refer to the LDS church as an unmitigated influence for good would be misleading Members of the Mormon community in Provo demonstrated open hostility toward theJapanese attimes.Helen Shiozawa recalled,"Some places wouldn't wait on you ifyou went shopping, and otherplacespeoplewould come out ofthebuildings and start calling you namesandthings. .andsoyoulearnedtoavoidthecity."Evenlocalleaders of the Mormon faith were sometimes cruel. During her senior year, Shiozawaandherhusbandexperiencedsuchcruelty first-hand:

We went to the ward [LDS church congregation] where I'd been going to church, this was not on the campus, and they told us that we lived in a different area now so we had to go to another area to church So we went there and the Bishop [ward leader] was waiting for us and refused us entry.... H e just met us and said you're not welcome here, and I knew why... He'd been warned by the other ward that I was coming So that ended our church affiliation until we left Provo.18

Suchepisodes,accordingtoShiozawa,werecommoninProvoatthe time. The university itself,however, seemed to be a haven for the Nisei In spite of occasional prejudices that surfaced within the community, most students felt very comfortable at BYU As Shiozawa recalled,"I had no prejudices facingme atschool....Theschoolwaswonderful! Oh,they [the people at BYU] were very good to me!""I'll tell you what," George Funatake remarked,"it was great!Because itwaswar time and all,I think thepopulation ofthestudentbody..wasreallyamixedbag But Ican tell you Ienjoyed it."SeichiWatanabe summed up hisBYU days:"They were wonderful! Excellent! Iwas treated very well... Imake asubstantial contributioneveryyearbecauseIfeelveryindebtedtoBYU."

LikeBYU,theUniversity ofUtah alsodecided to open itsdoors to the Nisei. On March 13, 1942,Leroy Cowles,president of the university, received aletter from the relocation council askingifstudents ofJapanese ancestrywouldbeadmitted.19 After some debate,Cowles andtheBoard of Regents drafted areply stating that "nothing had been done officially to prevent American-born Japanese students from registering at the University" and that "students who present transcripts of credit from

17 Watanabe and Funatake interviews

18 Shiozawa interview

"Board of Regents minutes, May 29, 1942, p 222, University of Utah Archives, Salt Lake City, in Jenny Nicholas, "Students and Soldiers: The University of Utah and World War II," unpublished essay in U of U archives

10

reputable institutions,together with recommendation asto their character and loyalty and who have sufficient money to pay their tuition and other expenses,will not be prohibitedfromregisteringhere."20

But theU ofU position wasnot without reservations Inthesameletter,Cowles spoke ofpossible"future restrictions"thatmight be applied to the campus area,due to the"very important military concentrations here." He continued:"Wedonot encourage [Niseistudents] to come aswe haveno way of determining what the future may bring It might happen that they would be requested to move onfrom here....We carryno responsibilityforwhatmaybedoneifthiswholearea isdeclared arestricted zone asisthe western coast."Healsospokeofhowtheuniversitywas"notinthepositionto furnish employment or free scholarships to such students,and they likewise willbesubjecttothenon-residentfee."21

Despiteadministrativeconcerns,applicationsfromtheNisei immediately begantopourinbythehundreds,andmanywereadmitted.Before the end of the year,the university had sixty-eight registeredJapanese Americans Theyhadalsoreceived270applicationsforwinterquarterandhad acceptedsixty-five.22 Infact,by 1943theUniversity ofUtahhadmore registered Nisei students than any other institution ofhigher learning in the nation Althoughtheadministrationwaslikelyunawareofitatthetime,the school wasthe onlyuniversityin theUnited Stateswith more than one hundred JapaneseAmericanstudentsinattendance,enrollmenthavingpeakedat 127 thatyear.23

Before the school reached its 1943 peak inJapaneseAmerican enrollment, however, some university officials began to grow alittle nervous, especially when problems over student housing arose.Toward the end of 1942,ElmerR Smith,professor ofanthropology andofficial advisorto the Nisei,notedthatanumber ofJapanesestudentslivedinboardinghouses or rentedroomsthatbelongedtolocalfamilies.Hefearedthattheareawould reach asaturation point if the number of Nisei students continued to increase.He reported to the board that "attitudes in the community, a

21 Ibid

23

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

University of Utah president Leroy Cowles.

20 Leroy E Cowles papers, accn no 23, box 1, fldr 33, University of Utah Archives, Salt Lake City, quoted in Mark Wiesenberg, "Japanese-American Students and the University of Utah" (1997), unpublished essay in U of U Archives

22 Board of Regents minutes, May 29,1942, quoted in Wiesenberg, "Japanese-American Students."

11

O'Brien, The College Nisei, appendix.

recentsurveyshowed,maybesoonofsuchnegativeproportionsastomake averylargenumber of[Nisei]studentsahindrancetotheirwelfare aswell as bringing various problems to a head at the University." Based on ProfessorSmith'srecommendations,theBoarddecidedtolimitthe number ofJapaneseAmericanstudentsto 150atanygiventime.24

Indeed,the Salt Lake community exhibited "negative attitudes" toward theJapaneseAmericanstudents.Localsspokeoutthroughthemediaandin letterstoPresident Cowles InMay 1942aneditorialinthe Utah Chronicle erroneously—and bigotedly—reported that Nisei transferees from out of state did not have to pay non-resident fees:"Dr Sproul declares that we oughttotakeJapanesestudentsfree ofcharge,whichisjustasifaman next doordemandedthatweleaveourgardengateopensothathecould dump his unwanted and unneeded material on our front lawn."The author concluded that "the University of Utah would be swamped byJapanese studentstakingadvantage ofthisfreeprogram.Why shouldthebadboy be givenaquarterafterhavingbeenspankedforhisbehavior[?]"25

Followingthearticle'spublication,rumorsconcerningtheNisei students proliferated. In an attempt to dispel false information, President Cowles answered mail,published articles,and delivered speeches To the Salt Lake Rotary Club in May of 1943,he asserted,"Rumors are to the effect that 350Japaneseareontheuniversity campusreceivingfree tuition The truth istherenoware 125personsofJapaneseancestryonthecampus.Some 25 arenativeUtahns."26 Then,in anarticleinthe Utah Chronicle, he defended theNiseibystatingthat"severalof[theJapanesestudents]are exceptionally brightandthe 125haveahighergeneralintelligencethantheaverageofall studentsattheUniversity."27 Thus,Cowlesdidmuchtotemperapotentially volatilesituation.

But the controversies surrounding the Nisei students at the U of U made up only asmallpart oftheir overall experience.Despite challenges, they gained wide acceptance into the university community In one way, the Nisei were considered among the most patriotic students on campus. They actively participated in war stamp and bond sales,for example, and sold more than their quota in the month of March 1943.In fact, they

24 Cowles papers, accn no 23, box 1, fldr 13, quoted in Nicholas, "Students and Soldiers." See also Douglas Hardy, "Caucasian Attitudes toward Japanese in Metropolitan Salt Lake City" (Master's thesis, University of Utah, 1946) Hardy studied under Elmer Smith, and the "recent survey" spoken of may be linked to the statistics cited in Hardy's thesis Statistics indicate that during the war years, the number of enrolled Nisei students at the U of U never did exceed 127. After 1943, as greater numbers of colleges and universities throughout the nation began to participate in the Student Relocation Program, the Nisei tended to spread out See O'Brien, The College Nisei, appendix

25 Utah Chronicle, May 7, 1942, quoted in Nicholas, "Students and Soldiers." Existing documents suggest that Cowles never "proposed" any kind of tuition waiver. His statement on page 11 makes it clear that, from the beginning, he and the board decided that "the Nisei would be subject to the non-resident fee." It appears that the author of this editorial based his remarks on false information

26 Salt Lake Tribune, May 26,1943, quoted in Wiesenberg, "Japanese-American Students."

27 Utah Chronicle, May 26, 1943, quoted in Nicholas, "Students and Soldiers." For a student response to local prejudice, see Utah Chronicle, May 14, 1942

UTAH HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

12

purchased more bonds and stamps per studentthantheaveragenon-Japanese student.28

Other Nisei involved themselves in extracurricular activitiessuchassportingprograms One student in particular became quite popular as aplayer for the U of U's NCAA championship basketball team in 1944.WatMisaka occupied avery important position asastarting guard for the team He went on to become a firstround draft pick of the NewYork Knicks and the first Asian-Pacific AmericantoplayintheNBA.29

Other former JapaneseAmerican students testified of their acceptance into theuniversity environment Roy Ishihara enrolledfrom 1942to early 1945.He and most of his family escaped mass confinement and moved from LosAngeles to Salt Lake City during the few months of voluntary evacuation in February 1942.At the time of the move, he was a nineteen-year-old sophomore at Pepperdine University in Los Angeles. Having converted to theBaptist faith someyearsbefore,hewas majoring

28

in Nicholas

29 Ogden Standard Examiner, November 6,1999

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

University of Utah player Arnold Ferrin (22) passes the ball to teammate Wat Mikasa during a 1944 NCAA tournament game against Dartmouth at Madison Square Garden.

Leroy E Cowles, University of Utah and World War II (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1949), quoted

13

inspeechandEnglish,withplanstoattendaseminarytobecome aminister Oftransferringschoolsherecalled,"TheUniversityofUtahwasone of the few universities atthat time that would accept those ofus ofJapanese background... Other universities said,'No,we don't wantJaps!'So I give themcredit.TherewerealotofJapaneseAmericanswho attendedtheU of U atthat time."According to Ishihara,the university provided a comfortable environment, and theJapanese felt secure on campus.With regard to thetreatmentthatheandotherNiseistudentsreceived,Roy stated,"At the Universityitself,theywere open.Ididn'thaveone incident of discriminationordiscourtesy....Theywelcomed usasstudents.Infact,theywent out oftheirwaytobefriendly tous."30

Kazuo Sato shared asimilar view.The Sato family had been long-time residentsofOgden,Utah Inthelate1930sSatoleft thestateandbeganhis collegestudiesattheUniversity ofWashington inSeattle.Inanticipation of the danger ahead for the Nisei,andin an attempt to avoid forced evacuation,hedecidedtoreturntohishomestateandfinishhissenioryearatthe University of Utah early in 1942 Of the situation at the U of U he recalled,"In my caseitwas fine Igot alongpretty good There was no animosity,no real concerns at all."With only ayearleft to graduate, Sato was astudent at Utah through the first quarter of 1943.He received his bachelor's degree in engineering.Due to hisshort stayon campus,he did not remember many specific experiences,but he continually insisted that "[TheNisei]hadnoproblemsattheuniversity."31

There are specific reasons why the University of Utah became such a haven for the Nisei and one of the greatest contributors to the Student Relocation Program Inpart,the efforts ofboth studentsandfaculty made adifference. Ofthe few former Nisei studentsinterviewed for this article, notonecouldrecallevenamoment ofdiscrimination onthepartofeither group.Instead,they remembered how both students and faculty had gone outoftheirwaytoextendawelcome

Furthermore, as was the case at BYU, the LDS presence may have helped in creatinganopen environment.Even asamember ofthe Baptist community, Ishihara could not deny the LDS influence."My experience withtheU ofU wasrealpositive,"heremarked,"andIattributethisto the Mormon group;theywere very friendly. In fact,theywould saythat they knew what we were going through because their ancestors,the Mormons who came to Salt Lake City,they were discriminated against back in the Midwest."32

Butmore thananything,thesuccessoftheStudentRelocation Program andthepositiveNiseireception on campusresultedfrom theleadership of President Cowles and his fellow administrators From the moment the

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

14

' Roy Ishihara, telephone interview by author, December 27, 1999; notes in possession of author Kazuo Sato, telephone interview by author, December 27, 1999; notes in possession of author Ishihara interview

doors were opened, the university accepted large numbers ofJapanese American students and became the national leader in that regard during 1942 Then,when rumors andfalseinformation began to circulate around the community,President Cowles quicklycametothe defense ofJapanese Americanstudents.33

And yet, similar to the BYU students, the U'sJapanese American students encountered open hostility in the community.About ayear into his studies,Roy Ishihara and aBaptist youth group ofabout thirty Nisei weremakingtheirwaybackfrom aSundayafternoon outingto the Great SaltLakeThe return triptotown requiredthatthey"passthrough aradio station,"apparently an area of town that was regulated by the military Certain restrictions applied to the area,including acurfew that forbade those ofJapanese descent to go near the station after five o'clock in the evening. Conscious of the situation, the group left their outing in just enoughtimetomakeitthroughthezonebeforefiveo'clock However,on theway,accordingto Ishihara,"apolice officer approached usandsaid we willgiveyou an escortto SaltLake City....Wehadplenty oftime to get back,buthesaid,'No,wewillescortyou.'"Withthat,thegroup proceeded, ledby two officers "As we neared the radio station,"Ishihara continued, "the policemen stopped us in the middle of the restricted zone,and we waited there until past five o'clock...then they arrested us.Look in the headlines....Theysaid,'JapsArrestedintheCurfew Zone!'"Fortunately for the group,the state attorney general and SenatorThomas both "went to bat" for them, and they were released after spending one night injail

Outside ofthe university securityblanket,then,thingswere not so secure for the Nisei.The campus environment at the U ofU seemed to differ fromthecommunity,offering aworldapartfortheNisei,aworldinwhich theycouldfreelypursuetheirinterests

Giventhefact thatbothBYU andtheU ofU madesubstantial contributions to the Student Relocation Program,it issurprising to learn that Utah StateAgricultural College chose not to participate at all Due to a paucity of documents,it is difficult to understand all of the reasons and circumstances behind the school's decision to exclude the Nisei. One reasonmightbeconnectedwiththefactthat,assoonafterPearlHarboras thesecondweekofDecember 1941,thefederalgovernment informed the schoolthatitsfacilities would most likelybe utilizedfor military training

At theJanuary 1942board oftrustees meeting,the board gave authorization to "accept quotas of trainees from government agencies in various

33 Cowles and members of the board retrospectively recognized their contributions to student relocation as one of the highlights of their careers Such recognition can be seen in Cowles's treatment of the topic in his University of Utah and World War II and in the remarks of Sydney Angleman at Cowles's retirement dinner, when he praised the president and other administrators for their "freedom from prejudice" despite "severe criticism by the thoughtless, the prejudiced and the blind," quoted in Wiesenberg, "Japanese-American Students."

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

15

lines of national defense service."A few months later, the Navy Department and USAC negotiated anofficial contract wherebytheschoolagreedtoreceiveitsfirstgroup of100students"for the trainingof radiomen onoraboutMarch 16."34

It was in that context that Elmer G. Peterson,president of the college,began to receiverequestsfrom the Student Relocation Council Justafewdaysafter theMarch contractwasdrafted,thecouncilsenthim acopy of the same letter it had sent to President Cowles of the University of Utah, asking if students of Japanese descent would be acceptedattheinstitution.Beforerenderinga decision,President Peterson appealed to state officials. On March 23 Governor Maw responded that "no policy [had] asyet been adopted by Utah with respect to Japanese." He assured the president that the state "[would] not make recommendations as to whether the USAC should permit Japanese students ofAmerican parentage to register at gj| [the] school,"and concluded that "whatever [he] and the board decided in the matter [would]beacceptable."35

President Peterson took the issue to the board oftrustees.Afew dayslater,on March 28,Petersondrafted areplytothecouncil Henoted,"After careful consideration ofthismatter ourBoard ofTrustees decided,inview ofour heavy program of defense training. .it would not be advisable for us to accept suchstudentsatthistime."Thereplywasshortandtothepoint.And while Peterson expressed"great sympathy,"the decision to exclude the Nisei,he insisted,wasoneofpracticality.36

Becauseinformation from theboardminutesandthepresidential papers tellusnothingmore about theadministration's earlyresponse,we can only speculateastothecircumstancesbehindtheschool'sdecision Itseemsthat the principal concern for the administration wasthe military activities on campus Perhaps school officials viewed the Nisei presence as a threat to

34 Logan Herald, December 11, 1941; USAC board of trustees minutes, vol 7, January 24, March 28, 1942, Utah State University Archives, Logan, Utah

35 USAC board of trustees minutes, March 28, 1942.

36 Ibid.; Peterson to Relocation Council, April 3, 1942

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Zik1 rCiii ,r,fc z !

Utah State Agricultural College president Elmer G. Peterson

16

nationalsecurityYetsimilarconcentrations ofmilitarypersonnelexisted on the campuses ofBYU and theU ofU,and those schools didnot deem it necessary to exclude the Nisei Maybe the administration anticipated increased militaryinvolvement inthefuture.But evenso,itseemsthat the beginningofthewarwouldhavebeenthebesttimefortheschoolto open its doors to as many Nisei aspossible.Such had been the approach of President Cowles and the administration atthe U ofU At first they took in asmany Nisei as they could; then, as circumstances developed, they founditadvisabletoatleastsetanenrollmentcap.

Assuming,however,thattheUSAC trulysympathizedwith theJapanese American students,how does one explain the administration's actions regardingthefew Nisei students alreadyinattendance atthetime ofPearl Harbor? Following U.S entry into the war,Peterson had released astatement advising students that itwasin their best interest to"continue their studiesuninterruptedly."37 Andyet,aroundthemonth ofMarch,mostlikely right after the board had established its policy with regard to Japanese American transfer students,the four or five Nisei then enrolled at the USACwereaskedtoleave.

SeichiWatanabewasofthesestudents HebeganhisstudiesatUtah State in 1941 and was approaching the end ofhisfreshman year atthe time of Pearl Harbor Although there had been talk ofon-campus changes before the year ended,he and about four otherJapaneseAmericans returned to school for the first quarter of 1942,logically following the president's advice to continue with their studies.Not long thereafter, each student received aletterfrom President Peterson statingthat,atthe completion of thecurrentterm,theywouldnolongerbewelcomedbacktotheschool.38

According toWatanabe,the request provided no explanation,and neither he nor any ofthe others sought one.In fact, throughout his life he assumed that the school's decision hadbeen the direct result ofamandate from the state."I didn't know,"he explained,"if Governor Maw decreed thatJapaneseAmericansnotbeallowedtoattendthestateinstitutions,orif it was the legislature."He further assumed that the same restrictions had been established attheU ofU "My understanding waswhen Iwas asked toleavethecollege,thatthesameappliedtoJapaneseAmerican studentsat the University ofUtah,so Ididn't try to contact the school."Seichi then attempted totraveleastto continue hisstudies,buthewasrefused aticket atthe Ogden railway station,and the stationmaster informed him that he couldnottraveleastwithout FBIclearance Ina"last-ditch effort,"he took the train from Ogden to Provo to inquire into the situation atBYU. He recalled,"President Harriswelcomed me with open arms Hisexact words 37 Logan Herald, December 11, 1941. 38 Watanabe interview

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

17

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

to me were,T hope you bring five hundred just like you; I will gladly acceptthemall.'"39

The reasonsbehind the decision toban enrolledJapaneseAmerican studentsareunclear Nothing intheminutes oftheboard orin the presidentialpapers suggestsanykind ofdiscussion ofthe matter.Watanabe testified thattheletterhereceivedhadbeenwrittenbyPresidentPeterson,but that did not mean Peterson was solely responsible for the decision. Moreover, thesituationreceivedno attentionfrom themedia EventheUSAC school newspaperfailedtoprovide coverage.

But the case was not yet closed Before the end of 1942, questions regardingtheUSAC policyresurfaced.On October 14,President Peterson receivedaletterfromJohn Provinse oftheWarRelocationAuthority, who wrote,"We arepleased to be able to inform you that your institution has been approved by both theWar and Navy Departments for purposes of studentrelocation.Thismeansthatyoumayproceedwith theadmission of Japanese-Americanstudentswho arenow atassembly centers orat relocation centers with the complete assurance that all necessary governmental sanction has been obtained."Apparently, the letter persuaded Peterson to reconsider the matter.He approached the board again and suggested that "itbethepolicyoftheCollegetoacceptthe [Provinse] recommendation." It seemed, for a time, that the school's doors would be opened to the Nisei.40

Butwhether ornot theadministration cameto anydefinite conclusions isdifficult to tell The minutes ofthe subsequent board meeting reflected no discussionoftheProvinseletteroroftheJapaneseAmerican studentsin general Infact,the Nisei question didnot appearin the board minutes at all throughout the remainder of the war.At the same time, attendance records continued to show that students ofJapanese background were not being accepted into the school.It seems the issuewas either forgotten or theboardminutesremained incomplete.

Only correspondence in thepresidentialpapers offers an explanation as towhy thepolicy remained unchanged On December 11,1942,Peterson receivedanotherletterfrom theWarRelocationAuthority:

This is to inform you that although the War Department gave its approval for [purposes of relocation of Japanese American students], on August 26, 1942, the institution has not been cleared by the Navy Department The misunderstanding arises from the fact that the name of this school was inadvertently included on a list of 259 approved institutions sent by this office to the National Student Relocation Council. We regret any inconvenience that this may have caused you. 41

40 E G Peterson papers, Record Group 3.1/6-2, box 204, fldr 8, Utah State University Archives

41 Ibid

39 Needless to say, Watanabe was shocked when he learned that the University of Utah had opened its doors to the Nisei from the outset "All these years I didn't know that," he exclaimed during an interview with the author "I would have gone to the U of U had I known that."

Althoughtheletteroffers apartialexplanationfortheunchanged policy, it does not explain why the issue apparently was not discussed by the board.Perhaps President Peterson had been made aware ofthe relocation council's "mistake"before receiving the above letter. Such knowledge would haverendered unnecessary the discussion oftheProvinseletter Or, perhaps theboard had made the decision to admit the Nisei,and the discussionwassimplyexcludedfrom theminutes.Whateverthecase,alack of availableinformation allowsforspeculationonly

Matters certainlybecame simplerfor the administration after it received the December letterfrom theWarDepartment.The navy,the same group with whom the school had negotiated its early contract,had the final say regarding the conditions on campus It became apparent in the following weeks exactly why the navy had intervened. InJanuary 1943 the school wasassigned"togiveacademictrainingtoandprovidehousingand feeding for one thousand Army Air Forces trainees."42 The military, therefore, increaseditsuseofUSAC facilities,negatingallchancesfor the institution toacceptNiseistudents.Theschooleventuallybecameoneofthirteen colleges in the western United States,and the only one in Utah,which was placed on agovernmental list ofinstitutions considered"important to the war effort"bytheWarDepartment.The schoolremained on thatlist until closetotheendofthewar.43

Thus,thestorybehindUtahState'sdecisiontocloseitsdoorsto collegebound Nisei is difficult to assess.The initial policy to bar Japanese American transfers is questionable.Moreover, the decision to expel those few Nisei students already enrolled at the school at the time of Pearl Harbor seemsto havebeen unnecessary anduncalledfor.Itmight be easy toplacetheburden ofresponsibilitysquarelyontheshoulders ofPresident Peterson andtheadministration.Butto dosowouldbeunfair,sincealack ofinformationrendersimpossibletheformulation ofanydefinite conclusions

The evidence suggeststhat theinstitutionwould haveaccepted students ofJapaneseancestryhadthenavynotintervened Indeed,thepresident had urged adoption ofthe recommendations setforth intheProvinse letter in hiscommunicationswith theboard Moreover,theschoolwent on to provide classesatthebranch collegeinCedar City (asmallcommunity in the southern part ofthestate),which they encouraged many Niseistudents to attend, especially those from theTopaz relocation camp.In aletter to Edward Marks inJanuary 1943,Peterson noted the final arrangements for initiating the program at the branch college and stated,"I regret that the main campus of Utah StateAgricultural College at Logan has not yet received Navy Department approval."44 It appears that Utah State was at

STUDENT RELOCATION PROGRAM

: Ibid

19

' Taylor, Price of Prejudice, 18 1E G Peterson papers, Record Group 3.1/6.2, box 204, fldr 8

leastonthepathtoopeningitsdoorstotheJapaneseAmerican students

Thus,the experiences ofBYU,the U ofU,and the USAC with regard to the Student Relocation Program offer some interesting insights into Utah's reception ofJapanese Americans duringWorldWar II.A unique world came tolife on the campuses ofBrighamYoungUniversity and the University of Utah.Among the most active program participants, both schools served as examples of the success of student relocation and its impact for good on the lives ofthousands ofJapaneseAmerican students.

Certain factors were important in creating afavorable atmosphere The influence ofreligion,inthiscaseMormonism,mayhavehelpedto generate anopen environment The friendly attitudesofstudentsandfaculty toward theNiseialsoplayedarole.Finally,thecourageandintegrityofthe administrations,particularlytheuniversitypresidents,wereespecially significant

Still,thevery different experience ofUtah StateAgricultural Collegeis equallyinsightful.Likemany institutions throughout the nation,itdid not open itsdoorsto the Nisei.Although the reasonsbehind that decision are unclear, it islikely that military considerations simply overrode all other factorsinshapinginstitutionalpolicyThelevelofdefense trainingon campus,asdictatedbythenavy,emergedasoneoftheschool'smost important concerns throughout the war—so important that even the existence ofa fewJapaneseAmericanstudentsoncampuswasconsidered threatening.

As Leonard Arrington noted, Utah's reception ofJapanese Americans duringWorldWar IIwasindeed ambiguous His assessment applies to the experiences of Utah schools.In some ways,they offered an exceptional environment wherein the Nisei could escapethe turmoil ofa hypocritical society;inothers,theysimplyreflectedtheharsh"realities"ofanationatwar.

HISTORICAL

UTAH

QUARTERLY

2 0

The Utah Writers' Project and Writing of Utah: A Guide to the State

By RICHARD L SAUNDERS

By RICHARD L SAUNDERS

The 1930sarealmostdefined bytheeconomic recovery programs oftheRooseveltadministration.Midwayintothenationalrecoveryprocess,in 1935,asliverofreliefwork wasbudgeted to put unemployed writers,researchers,and office workers into meaningful employment TheFederalWriters'Project (FWP) employedlessthan1 percent ofthe nation'spublic reliefrolls—and garnered criticism inversely proportionaltoitssizeTopoliticians,theFWPwasmerelyonemore strategytoputpeopleintopayingwork;anythingactuallyproducedwasaside benefit To those who actually led the work, however, it represented an opportunitytogenerateliterarymonumentsthatwouldstandalongside the parks,trails,and watercourse improvements built by other relief projects Drawing upon aEuropean tourist tradition,theBaedeker guidebooks,the FWP envisioned its crowning contribution

A u r j Utah Writers'Project director and to American culture as a series or guidebooks,theAmerican Guide Series,which Utah guide editor Dale Morgan would describe the country geographically, autographs a copy for Governor historically,andculturally1

Herbert Maw.

1 Jerre Mangione, The Dream and the DeahThe Federal Writers' Project, 1935—1943 (2d ed.; Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), 46-49 The FWP also produced several regional and city guides, but the guides for the forty-eight states and the territories of Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii were the main focus The widespread criticism of the FWP in the conservative press is considered in detail in Mangione's book

Richard L Saunders is the curator of Special Collections at the University ofTennesee at Martin His most recent book is Printing in Deseret; currently he is at work on a biography of Dale Morgan

21

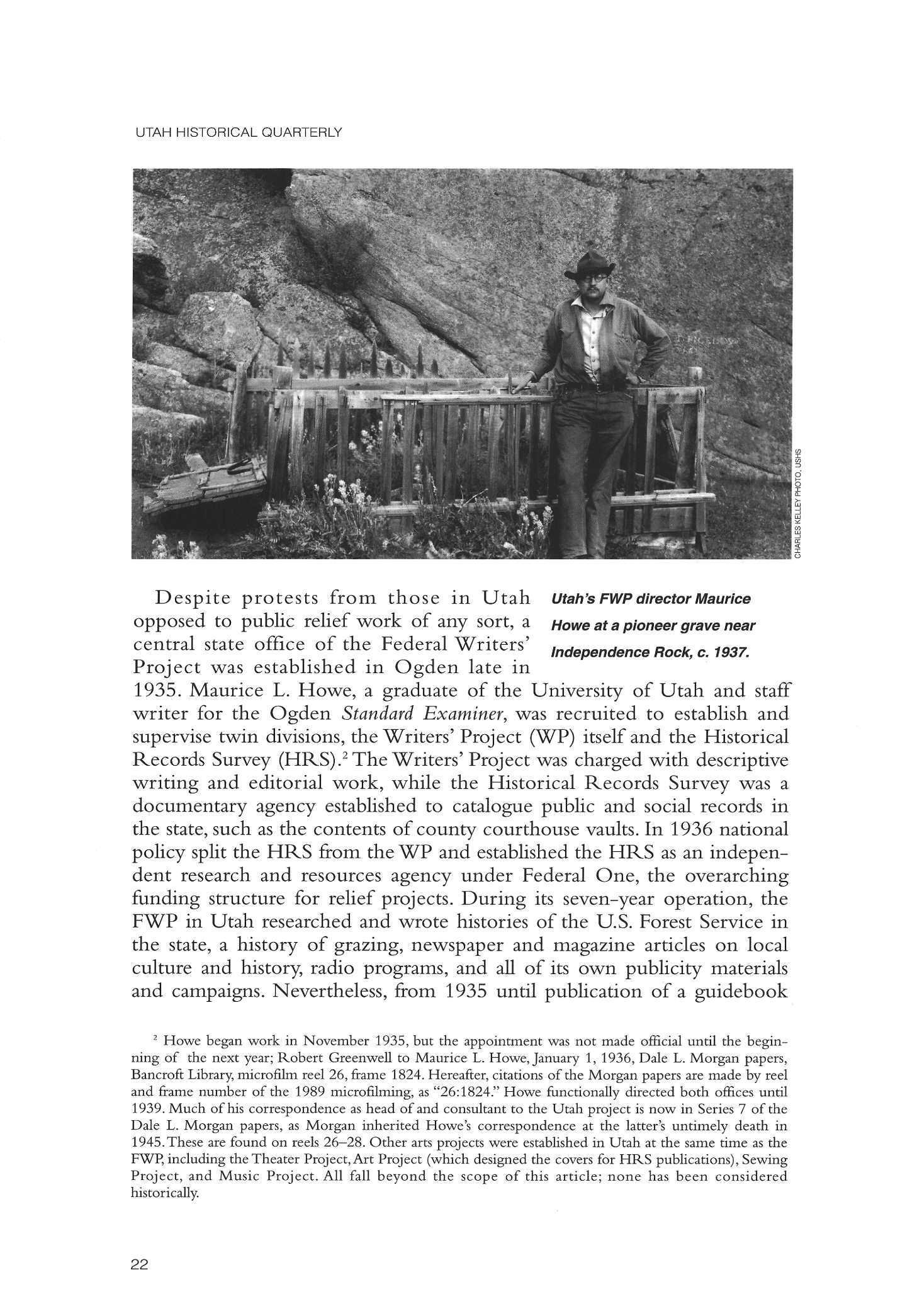

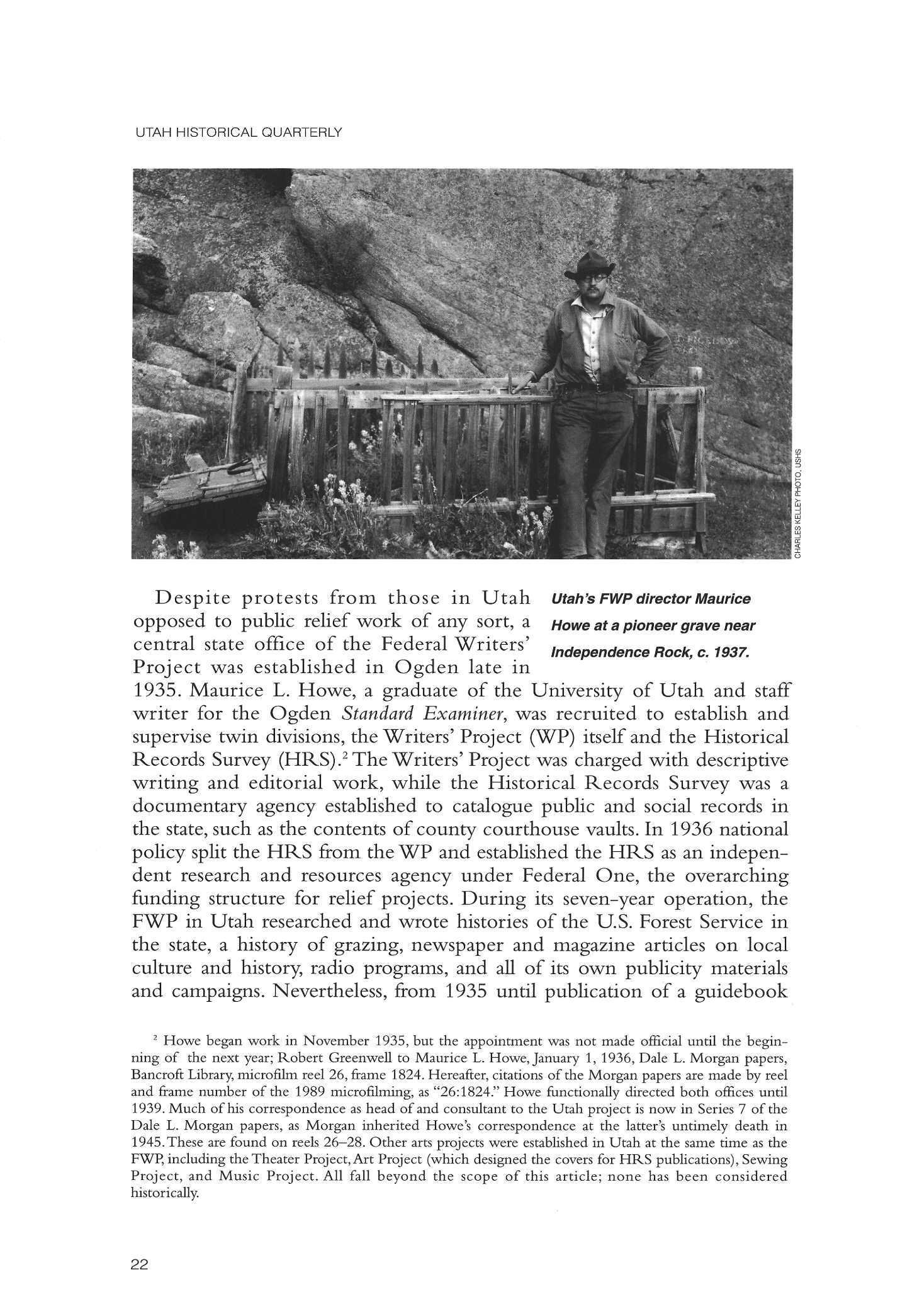

Utah's FWP director Maurice Howe at a pioneer grave near Independence Rock, c. 1937.

Despite protests from those in Utah opposed to public reliefwork of any sort,a central state office of the Federal Writers' Project was established in Ogden late in 1935.Maurice L.Howe, a graduate of the University of Utah and staff writer for the Ogden Standard Examiner, was recruited to establish and supervise twin divisions,theWriters'Project (WP) itselfandthe Historical Records Survey (HRS).2 TheWriters'Project waschargedwith descriptive writing and editorial work, while the Historical Records Survey was a documentary agency established to catalogue public and social records in thestate,suchasthecontentsofcountycourthousevaults.In 1936 national policysplittheHRS from theWP andestablishedtheHRS asan independent research and resources agency under Federal One, the overarching funding structure for relief projects. During its seven-year operation, the FWP inUtah researched and wrote histories ofthe U.S Forest Service in the state,ahistory of grazing, newspaper and magazine articles on local culture and history,radio programs,and all ofits own publicity materials and campaigns.Nevertheless,from 1935 until publication ofa guidebook

2 Howe began work in November 1935, but the appointment was not made official until the beginning of the next year; Robert Greenwell to Maurice L Howe, January 1, 1936, Dale L Morgan papers, Bancroft Library, microfilm reel 26, frame 1824 Hereafter, citations of the Morgan papers are made by reel and frame number of the 1989 microfilming, as "26:1824." Howe functionally directed both offices until 1939 Much of his correspondence as head of and consultant to the Utah project is now in Series 7 of the Dale L Morgan papers, as Morgan inherited Howe's correspondence at the latter's untimely death in 1945. These are found on reels 26-28. Other arts projects were established in Utah at the same time as the FWP, including the Theater Project, Art Project (which designed the covers for HR S publications), Sewing Project, and Music Project All fall beyond the scope of this article; none has been considered historically

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

2 2

in 1941,the primary goal of Utah's FWP (and its successor, the Utah Writers'Project) wasthecreation ofamanuscript fortheAmerican Guide Series

Asproject directorandeditor,MauriceHowefacedthe dauntingtask of generatingusableresearchfilesandbeginningtocompiletheguidebook at thesametimethatthenationaloffice wastryingfirsttodecideandthen to communicatewhattheWriters'Projectwoulddoandhowitswork should be done.Tomake areasonable beginning,Howe dispatched hispeople to work in several directions Some of his twenty- to thirty-member HRS staffbegan by generating survey forms for workers (usually no more than two in acounty;some counties hadno workers) to useininventories and descriptions of county records.Others began compiling bibliographies of publishedworksthat contained dataonspecific counties ortranscribing or abstractingsignificantworksanddividingthetranscriptsintotopicalfiles.

Almost as soon as the project office was established in Ogden, the Writers' Project staff set to work outlining potential sections of the guidebook.Within a month, half a dozen were completed and filed. Writing effort soon shifted toward expanding outlinesinto drafts The staff also began apreliminary page-length estimate and layout on the Utah guidebook In May 1936 they completed apage-makeup dummy and a full-scale outline allotting space for essaysand specifying the number and placement ofillustrations,and they dispatched these to the national office The dummy wasfollowed inJulybypreliminary drafts ofseveral sections fortheforthcoming volume.3

While work progressed on the narrative sections of the forthcoming guide,ahandful ofotherworkers were dispatched throughout the state to drivecountyroadsandhighwaysTheyrecordedmileagebetween intersections,listed sites ofhistoric or scenic value along roadways,noted driving conditions andresources atravelermight need,andweighed the merits of one route over another.Their reports, edited and presented neatly in sequence, eventually resulted in a detailed set of in-state road tours coveringeverynook andcranny ofthestateandoccupyingnearlyhalfthe completed guidebook.

TheWP staffwascomparatively smallin anyone state,but each project employed dozens ofpeople with awide range ofskills (and competence levels)who occasionally demonstrated the willtowork atcross purposes. 4 The writingprocesswashampered bythreemajor flawsforeseen by FWP officials atthe inception ofthe program:widely diverse abilities,interests, and writing styles of those employed; staff turnover; and the stylistic choppinessthatinevitablyresultedfrom thefirsttwoThe solutionto these

3 Outlines for "Manufacturing and Industry," "Transportation," and "Hotels" may be found in Morgan papers, 26:1796, 1802, 1811; "Prehistoric Inhabitants of Utah" was dispatched to Washington as early as June 10,1936; seeWPA papers,"Final Copy," 80, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City (USHS)

4 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, chapter 4

UTAH WRITERS' PROJECT

2 3

problems had been to centralize the review and approval processes for anything intended for publication. Central review fostered stylistic coherence,but the turnaround for manuscripts sent to theWashington office becameachronicproblemalmostimmediately.Thedelayswere compoundedbydirectorHenryAlsberg'sdesiretohavethefinaleditorialapproval on everything the country produced.A guidebook section was first drafted, edited,corrected,andretypedatthestateoffice before carbonsweredistributed to outside reviewers and forwarded to the national office. Here, each sectionwasreviewed,editedforlanguage and theme,forwarded to director Alsbergforthesameprocess,andthenreturnedtothestate office—theoretically.In reality,because ofthe veritable avalanche ofmaterial pouring in from thestate offices,theWashington office became abottleneck for drafts atalldifferent stagesofapproval.Statematerialsriskedlosswithin the cogs ofbureaucracyandAlsberg'sfreneticallypacedorganizationalstyle.5

Through 1936 and halfway through 1937,the Ogden office forwarded draft chapterseastwardfor reviewand approvalasquicklyasthey could be written.But since fifty other states and territories and several cities were doingthe same,Utah'smaterial only addedto anunmanageable deluge of manuscripts.Being asmall western state,Utah did not rank high on the national priority list TheWashington stafflargely ignored its submissions, and drafts from Utah eventually eddied into the quiet backwaters of file drawers. Unaware of this,the FWP office staff back in Ogden busily continuedcompilingdata,organizingresearchfiles,anddrafting essays.

The desirefor process and stylisticsimilarity among the guideswas frustratedfurther bythetangle ofconflicting instructions,formats,outlines,and formsthatspunoutofthenational O&LCQ likeaspider'sweb Itwasquitepossible for astate office to submit achapter and have it returned "approved with minor corrections"in its first stage ofreview—and then to have the whole corrected draft rejected as unsuitable when it was resubmitted amonthlater Forinstance,oneparticularsetofUtah tourswas submittedinFebruary 1938.Themanuscriptlayuntouched intheDC.files untilAugust,whenitwasreturnedwithouteditorialcomment;then,thefollowingJanuary,itwasdiscardedasunacceptableatWashington'sinsistence.6

While Howe busied his staffin Utah,the first volume ofthe American Guide Serieswasissued.Itwasnot,ashadbeen planned,theWashington, D.C.,volume The Idaho FWP director,novelistVardisFisher,had ignored directives and regulations, written the text mostly himself, offered the manuscripttoacommercialpublisher (CaxtonPress),andgottenthe Idaho guideintoprint in early 1937.Thiswasnotmerely anissueoverwho was abletoreleasethesymbolicfirstbook Byfederallaw,government publica-

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

5 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 13-14. Maurice Howe commented privately on Alsberg, calling him "a punk [i.e., poor] executive and marvelously evasive"; Maurice Howe to Darrell Greenwell, Morgan papers, 27:164.

2 4

6 Howe to Darrell Greenwell, August 25,1939, Morgan papers, 27:165

tions were to be printed by the Government Printing Office and distributed atnominal charge.Thisregulationhadalwaysbeenastickingpoint in the plans for theAmerican Guide Series.Fisher had avoided the issue by having the Idaho secretary ofstate sponsor publication ofthe guide After discussing it among the staff and tweaking FWP regulations to create a loophole,Alsberg and theWashington office instructed other projects to follow suit State offices were to find nominal public sponsors for the guidebooks from within the state.This move meant that the guidebooks would not be strictlyfederal reliefprojects,and thus they could avoid the federalprintingrestriction.7

Rather thanpitch stateguidebook manuscripts topublishers individually,asFisherhaddone,Alsberghitupon aplanfornationalpublishersto bid onstateguidemanuscripts grouped insmalllots.Inthisway,stateslike the Dakotaswouldhavethesameopportunities for qualitymanufacturing and national distribution that the NewYork or Massachusetts guides would. Utah's guidebook wound up,along with those from Arizona,Arkansas, California,Colorado,Louisiana,Mississippi,New Mexico,andTexas,in the handsofHastingsHouseofNewYork.8

InUtah,thesearchfor astatesponsor,apainful and drawn-out process, was the responsibility ofWriters' Project editor Charles Madsen, one of Howe'soriginaltour-writingcrewandthemanagerofdailyactivityin the WP office.Madsen presented the sponsorship plan to the Ogden and Salt LakeCitychambersofcommerce,receivingagooddealofexcited interest, butneitherbodywasinapositiontoadvancesponsorship money.He then approached the State Road Commission and the Utah State Historical Society,buttheirrefusalsalsocitedmoneyastheissue.Madseneven floated theideaofdistributingproduction costsamonglocalprinters and publishers,and he asked for a cost estimate from printer and amateur historian Charles Kelly at theWestern Printing Company "All feeling favorable to Guide,"noted aninternalpublishingreportfor early 1937,"but no funds." Potential distribution of the as-yet-unpublished guidebook was about as encouraging.Howepersonallywrotetoeverystoreinthestatethat carried books.Onlysixrespondedthattheywouldbeinterestedincarryingsucha volume.9

Atthe end ofJune 1938Maurice Howe wassummoned toWashington andappointed to the FederalWriters'Project centraleditorialstaff But he retained directorship of the Utah project, supervising the writing and editorial work by correspondence until June 1939. Howe was then reassigned,and Utah's HRS andWP offices became independent projects

7 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 202-207, 220-22 The title page of the Idaho guide was dated 1936, but the volume was actually published the following year

8 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 230—32.

9 "Publications Report," 1937, Morgan papers, 26:1861; Howe to Morgan, May 13, 1941, Morgan papers, 26:879

UTAH

WRITERS' PROJECT

2 5

with separate management Law student Dee Bramwell was appointed to head the Utah HRS, and Charles Madsen became head of theWriters' Project Because of his personal interestintheresearch andactivitiesin Utah, Howe remained connected asan official (but unpaid)project consultantand advisor.10

Utah's leadership change was symptomatic of the recurring challenge that plagued research and writing staffs nationwide. Since theWriters'Project wasareliefprogram,turnover in theproject staffs was steady,evenamong themembers not on relief,dueboth to migration into better paying private-sector jobs and to regulations limiting the time a workerwasallowed toremaininareliefposition.Beyond afew key "noncertified" positions (hirees not on work relief, some of whom had part-time appointments) both the HRS andWP were required toput into serviceanyonewhowassentthem—notalwaystothebesteffect.The Utah project faced aspecific challenge in Howe's replacement Charles Madsen hadbeeninvolvedwiththeforthcoming guidealmostsincethe beginning, yetwith the loosening ofHowe's direction,work on the Utah guidebook ground quickly intolow gear.Madsen waswell-respected for hisability to create the tours that would go into the guide,but asan administrator he cloaked himselfand entangled hisstaffinpetty office politicsWittingly or unwittingly, Madsen played staff members against each other, creating an atmosphere in which it was difficult for workers to trust each other

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Tour writer and Utah guide editor

Charles Madsen, on the left, at the W-Bar-L Ranch, between Mexican Hat and Bluff, San Juan County, c 1936. Also in the photo, from left to right, are Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Lee, Robert Clark Tyler, and Buck Lee.

26

10Robert Slover, Circular Letter no 7, June 2, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:64; Charles Madsen to Hugh O'NeilJuly 2, 1938, Morgan papers, 26:1988

sufficiently todraft,critique,andeditworkproductively.11 Similar situations thatfrustratedWP workinotherlocationswereaddressedfrom the central office,but,intent onpushingguidebooks tocompletion inotherstates,the centralFWPoffice seemednottonoticetheseissuesin Utah.

Bythefallof1938,many ofthe stateguideswere atthe manufacturing stage.The national office atlastrealized thatitshouldbe concerned about theUtahvolume,andtheregionalandstatesupervisorswerefinally willing to admitthat,despitetwo and ahalfyearsofwork,littlehad actually been accomplished.To stimulate Utah's writing process (and evidently unaware of the drafts already buried in their own files), avisiting member of the national staffsolicitedVardis Fisher,head ofthe IdahoWriters'Project, to pushoutanacceptableguidebookmanuscriptforUtah.12

InWashington, Maurice Howe forcibly pried from the grip of the national office the material that Utah's project had submitted to date and returned it to Salt Lake City.Much ofit had been "in review"for more than ayearandwasstillin editoriallimbo.VardisFisher made atrip from BoisetoSaltLakeCityinApril 1939tofindnear-chaosamongthe assembled drafts.The first batch oftours and descriptive essayshe discovered to be incomplete Most had notes like "See Madsen for this material" and "Thistobeaddedlater"sprinkledliberallythroughoutthepages.Checking randomly asecond,third,and fourth batch,he discovered that incompletions were not limited to discrete sections of the drafts;most or all were incomplete and,with isolated exceptions,inno condition tobe edited for publishablecopy.13

Several months later,in mid-August, the national reviewer, a woman cited only as"Mrs Isham,"again cameWest unannounced and demanded from Fisheranassessment oftheUtahproject.Hewasnot complimentary. Yes,draftswerestillincomplete,buttheeditor'scooperationhadbeen difficult for him to secure.Having worked with the Utah essays since spring andhavingbeen in the Utah offices for severalweeks,Fisherlaid primary responsibility for Utah'slack ofheadway squarely on state editor Madsen, who had regarded Fisher's appointment as apersonal affront "I do not think it reasonable to expect even an efficient staff here to get the Utah book ready before the first of the year,"Fisher reported."There's simply too much tobe doneyet.Toomuch copyisintherough."He was giving up.Both the FWP official andstateWPA administratorDarrell Greenwell, whohaddislikedtheWriters'Projectfromthefirst,askedifFisherknew of

"See statements about Madsen by office workers in Morgan papers, 27:1100-112 Comments on Madsen's feuds are discussed in Fisher to Howe, August 17, 1939, 27:146; Fisher to Howe, August 20, 1939, 27:152; Howe to Greenwell, August 25, 1939, 27:165; Fisher to Greenwell, August 29, 1939, 27:169; Fisher to Howe, October 18,1938, 26:2057

12 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 201-208; Dee Bramwell to Dale L Morgan, August 15, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:142;Vardis Fisher to Howe and Fisher to Henry Alsberg, October 18, 1938, Morgan papers, 26: 2057, 2052; Salt Lake Tribune, August 30,1939

13 Fisher to Howe, August 17, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:146

UTAH WRITERS' PROJECT

2 7

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

someonewhowouldbeabetterdirector.He didnot.14

Inaprivateletter to Howe written afew dayslater,Fisherreported the rounds of intrigues and posturing ambitions that plagued the Utah WP office andasked,"Doyouknow ofanyonewho couldwhip thebook out?

Firstthingyouknow G[reenwell] willbeclosingthisproject."15 Greenwell, knowing that Howe himself was caught in the flux of a shakeup in Washington and the dismissal of FederalWriters' Project head Henry Alsberg, also wrote to Howe suggesting he return to Salt Lake City to againheadtheUtahproject.Howe respondedwith encouragement, noting that Fisher could write well but tended to overreact Admittedly, Madsen wasnot acareful editor,but,Howe told Greenwell,he had earned asolid reputation with the national office for consistently generating good tour materials.Hehaddoneagreatdealofworkandshouldbeallowedto finish the task.Howe didwelcome Greenwell'ssuggestion that anew supervisor be found.16

Fishersubmitted hisformal report onthestatusoftheUtah guidebook, including estimates on the time needed to complete various parts, on August 29, 1939 In the report Fisher also suggested that in order to streamline the process the Ogden office be closed and that reliefpositions located elsewhere in the statebe relocated in SaltLake City He proposed thattheUtahWP securetheservicesofMontana'stoureditorand suggested hiring an office manager to take managerial responsibilities out of Madsenshands,allowinghim to concentrate onwriting.Both suggestions were veiled swipes at Madsen. Fisher now said he saw no reason that a complete guidebook manuscript could notbeapprovedbyJanuary 1940.17 Though the offices were consolidated ayearlater,most ofhis recommendationswere ignored

Inaddition,theUtahofficewasworkingwithlargercomplications looming overhead. NationalWriters'Project director Henry Alsberg had been dismissedinMay.Inadditiontotheuproarconnectedwiththisfiring,everyonehadbeen distractedbycongressionalwrangling overCongress's authorizationforthenationalproject andthepotentialfalloutiftheFWPwasleft withoutfunding Through thelatespringandintothesummerof1939,the work pace in Utah had lagged appreciably asthe HRS in Ogden and the WP inSaltLakeCitymarkedtime,workingontasksandfilesthatcouldbe completed quickly and dropped ifthe funding plug were actually pulled. Writing on the Utah guide was slowed dramatically or not done at all Francis Harrington, the national relief-project administrator, even ordered offices closednationwide afterJune 30 (thelastfunded day) until the vote

14 Fisher to Howe, August 17, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:146; Fisher to Darrell Greenwell, August 27, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:169.

15 Vardis Fisher to Maurice Howe, August 17,1939, Morgan papers, 27:146

16 Greenwell to Howe, August 22, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:159; Howe to Greenwell, August 25, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:164

17 Fisher to Greenwell, August 29, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:169

28

onthependingReliefBillresolvedthefinalstatusofFederalOne.18

Writers' Project funding survived the congressional vote tally,but the compromise bill that passed required several drastic,immediate changes

First,theideaofguidebook sponsorshipwasexpandedtoapplytothestate projectsasawhole Somestateshadalreadypublishedtheirguidebooks and closed their offices, but theWriters'Project offices still functioning were required to obtain partial support from sponsoring bodies within their respectivestates. InUtah,CharlesMadsenmadehastyarrangements toslide theWriters'Project under the rubric of the Utah Institute of Fine Arts (UIFA),the state cultural resources office This provided the state's orphan guidebookwithaparentatlast(aco-sponsorwaslaterfoundintheSaltLake County Commission) A second funding condition was that,rather than merely accumulating topical researchfiles,each office must secure sponsors willing to underwrite some ofthe costs ofthe research and distribution of individual writing projects.Writers' Project work would center on what could be funded The legislation also transferred administration from the national level to the states themselves,aprocess that recreated the various stateWP offices asfederallysubsidizedresearch-for-hire units.19 Utah'sguidebook,conductedundertheUIFAsponsorship,becamemerelyoneofseveral large-scaleprojects envisionedbytheUtahWP,amongwhichwere a major historyofgrazingintheWest (completedbutneverpublished) andahistory ofthe Forest Service,which became entangled in sponsorship negotiations andwasabortedbeforewritingwasbegun.20

On thesamedaythat Fisherdatedhisreport,theUtah Institute ofFine Arts signed alease on the old ElksBuilding at 59 So.State Street in Salt Lake City,intending to renovate it asacommunity arts center and offices for the UtahWriters'Project.Within the week, the project sponsorships that the staff had scrambled to draw together werejudged sufficient to meritcontinuedfederal support,andPresidentRooseveltsignedthe necessarypapers InpreparationforthemovetotheElksBuilding,Madsen traveled to Ogden in mid-September to notify the staffthat offices would be centralizedinSaltLakeCity.Bythelastmonths of1939,theOgden office oftheUtahWriters'Projecthad closed.21

The newUtahWriters'Projectwasnowreasonablysecure,and attention returned to the flagging state guidebook Under renewed pressure from

18 Fisher to Howe, June 2, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:65; O'Neil to Morgan, June 24, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:86; Bramwell, Circular Letter No 10, June 30, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:89; Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 13-16, 329-30

19 Mangione, Dream and the Deal, 20—21, 330

20 Smaller projects included publication of Provo: Pioneer Mormon City and a book collecting the texts from state historical markers titled Utah's Story. A "dictionary of Utah altitudes" nearly made it to press with University of Utah sponsorship, as did a Salt Lake City almanac with help from the county One project that was discussed but never got off the ground was a history of Utah's mining industry; another was a history of the Great Salt Lake. Dale Morgan later wrote such a book privately.

21 Salt Lake Tribune, August 29, September 6, 1939; Madsen to Howe, September 12, 1939, Morgan papers, 27:192; Howe to Morgan, October 11, 1939, Morgan papers, 26:575

UTAH WRITERS' PROJECT

29

state and national administrations,Madsen began pushing his writing and editorial staffto produce The pressure backfired badly Staffmembers,still stressedbyinternaldissension,werenowalsosuspiciousoftheir supervisor, and they accomplished little useful editorial work By the third week of September,Madsenknewheneededhelp,andhequietlyoffered HRS historian and editor Dale L Morgan ajob on theWriters' Project staff Morgan was closeto beginning amanuscript on the State ofDeseret that he wanted to write and was putting out HRS county historical sketches with regularity. His attention had been drawn to Farrar & Rinehart's Rivers ofAmerica Series aswell.Infact,on the first ofOctober he wrote the firm proposing avolume on the Humboldt River, and he was still writing to advertising firms throughout California seeking permanent employment With his capacity for writing already strained by what he wanted todo,Morgan declinedtheoffer,feeling thathe couldnottake on anotherlarge-scalewritingoreditorialprojectliketheUtah guidebook.22

With Fisher gone and Madsen still playing office politics, the Utah Writers' Project was left with an incomplete guidebook manuscript, a writingstaffalmostparalyzedbyintrigues,andaneditorinaquandary over preciselyhowtoproceed.Impatient,thenationaloffice moved preemptively and informed the Utah office in December 1939 that aconsulting editor was being dispatched from Washington. Not knowing quite what to expect,inlateJanuaryMadsenaskedMorgantoatleastreviewand critique the historical essay, which had already been through one round of approvals.Morgan agreed.After several dayswith the material,though he feltthatonthewhole theworkwas"ablywritten,"hereturned adevastatingfactual critique.Hiscatalogue offactual errors orfaulty interpretations rantothirteen closely-typed pages "My principle [sic] objection," Morgan wrote to Howe,aclosefriend,"isthat the [guidebook's] emphasislies too greatlyonevent,onpoliticalhistory,andtoolittleonthepeople."23

Less than two weeks later, national Writers' Project editor Darel McConkey arrived in Salt Lake City and set about reviewing drafts and discussing with the staff what yet needed to be done.LikeVardis Fisher months before, McConkey was not impressed with the Utah Writers' Project's collection ofwritten material,andhe confronted Charles Madsen about the state ofthe office and the project Earlier inWashington, Howe had quietly suggested thatMcConkey getDaleMorgan involvedwith the guide,oratleastthehistorical essaysAgainstthisbackdrop,out ofMadsen and McConkey's meeting came an idea to borrow rather than to draft Morganawayfrom theHRS Withindays,McConkeywascampedinWPA director Darrell Greenwell's office insisting that Morgan's services were required if the guidebook project was to be salvaged at all Greenwell

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

22C. C.Anderson to Morgan, [July 1940], Morgan papers, 27:1101; Morgan to Howe, September 26, 1939, Morgan papers, 26:245.

3 0

23Morgan to Howe, January 24, 1940, Morgan papers, 8:915 and 27:303