3 minute read

In This Issue

At the age of twenty-five, the future founding father and second president of the United States, John Adams, wrote in his diary in 1760,“I must judge for myself, but how can I judge? How can any man judge unless his mind has been opened and enlarged by reading?” Reading continued to be a life-long passion for Adams and his insights about government and the solid leadership he rendered owed much to the history, literature, and essays he read. Contributors to the Utah Historical Quarterly have a well-deserved reputation of providing readers with the substance for enlightenment, appreciation, entertainment, and enrichment. The writers whose articles appear in this issue of the Quarterly are no exception.

Our first article considers the life of Willem DeBry and his role in the publication of the Dutch-language newspaper De Utah Nederlander from 1914 to 1935.Like thousands of other immigrants to Utah and the United States during the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, DeBry embraced America but did not forget his homeland. DeBry sought to keep the ties to the Netherlands strong by preserving the Dutch language among immigrants and their children in Utah and, in a time of still limited communication between Europe and the New World, faithfully reported news from the Netherlands. DeBry and De Utah Nederlander remind us just how important journals and newspapers are in keeping a community or a people connected and just how rich the social and cultural life was among Utah immigrants.

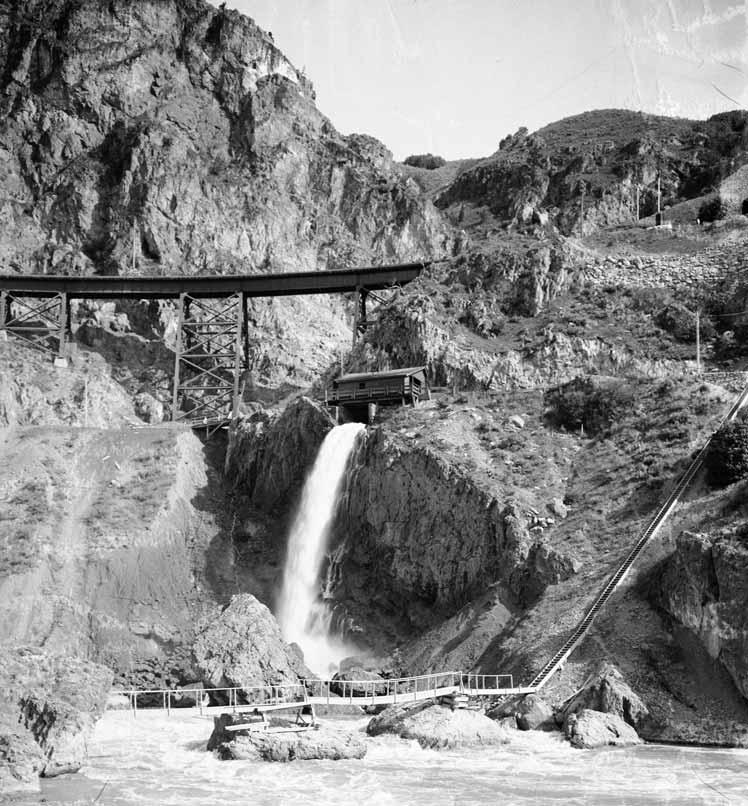

View of Bear River Canyon (Gorge), Box Elder and Cache County line, 1913.

SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Our second article considers the question of economic cooperation and individual enterprise in nineteenth-century Cache Valley. The idealism of the Mormon cooperative community, articulated so eloquently by Brigham Young and others and pushed so fervently during the United Order movement of the late 1860s and the 1870s, sounded throughout Utah’s valleys against a distinct counterpoint of individualism, private economic opportunity, and need. In the turmoil created by the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the emerging mining industry in Utah and surrounding states, the anti-polygamy crusade, and the just-out-of-reach goal of statehood, it is not surprising that the economic alternative offered through the cooperative movement did not receive unchallenged acceptance.

Bear River Duck Club, Box Elder County, 1906. Later the Duck Club became part of Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.

SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Another challenge to cooperation came a century later as Utah and Idaho encountered the question of the most judicious use of the waters from the Bear River. This most unusual river springs from the north slope of Utah’s Uinta Mountains, flows north into Wyoming and around the northern shore of Bear Lake before turning south to reenter Utah and discharge its waters into the Great Salt Lake. The course of the river runs over five hundred miles, yet its point of origin is only ninety miles east of the Great Salt Lake. As our third article demonstrates, the designation as “the Hardest Worked River in the World,” is one that is well-deserved given the vital role the Bear River has served in the agricultural and economic life of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

Frances Burke, the subject of our last article, served as a Presbyterian missionary in the predominantly Mormon community of Toquerville for more than four decades from 1881 until 1925 when poor physical health ended her ministry. A fearless woman of commitment ,idealism, and persistence, Miss Burke entered a hostile environment that a person of less fortitude could not have endured. Yet she ended her days honored and remembered by the community for her selfless service and devotion.