60 minute read

The 1966 BYU Student Spy Ring

The 1966 BYU Student Spy Ring

By GARY JAMES BERGERA

... I wanted to know from regular students what their regular teachers were teaching, and I think information of that kind is proper for me as the President [of Brigham Young University] to know, and I think this method of finding out is a proper method ... I know of no other alternative, except wiring the rooms, and I have not employed that method.

—Ernest L. Wilkinson, “Draft of Report for the Board of Trustees on Surveillance of Teachers ...,” April 17, 1967

Following a hard-fought but unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate in 1964, Ernest L. Wilkinson, the no-nonsense sixty-five-year-old lawyer-turned-president of LDS Church-owned Brigham Young University, returned to his beloved Utah Valley campus determined more than ever to mold the school into a showcase of conservative thought.1 His tenplus months on a grueling campaign trail had helped to reinforce his already strong political beliefs and to further stoke his fears of a nation blindly marching towards communism. He was convinced that during his year-long absence from the Provo school a “group of ‘liberal’ teachers had decided to attempt to change the political and social atmosphere of the BYU so as to bring it more in line with the prevailing political trend toward Socialism rather than the traditional conservative view of the Church.”2 “We are facing a great crisis in this country,” he told ninety-one-year-old David O. McKay, the Church’s venerable prophet-president, “and many of our political science and economics teachers are teaching false doctrine.” 3 “The problems that I will face,” he confided to his diary, “are much larger than those I faced when I first came in as president of the B.Y.U.” in 1951. Even so, he told himself, “I am going to do what I can to reverse [this] trend.”4 Wilkinson’s attempts to expose members of his faculty who, he believed, were guilty of disloyalty to LDS doctrine—as Wilkinson interpreted it— would culminate in a short-lived administration-initiated student spy ring. Wilkinson’s subsequent actions would reveal a university president reluctant to acknowledge his own involvement and willing to shift the blame onto others less able to defend themselves.5

Brigham Young University President Ernest L. Wilkinson greets freshman students.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Wilkinson’s brand of conservative politics was shared by a majority of his church’s general officers (many of whom also served on BYU’s Board of Trustees) as well as by Church President McKay. But while almost all of his LDS colleagues tended to hold their political views closer to the chest, Wilkinson publicly positioned himself as a fearless crusader of what he termed broadly as fundamental American freedom. 6 He nurtured an especially close relationship with McKay, and carefully cultivated McKay’s support in championing his beliefs. While some trustees occasionally voiced concern over Wilkinson’s privileged access to McKay, Wilkinson almost always succeeded in securing his board’s support in his governance of BYU, thus insulating himself, he hoped, from criticism and attack.7 He may have suffered some major disappointments (such as his failure to relocate the church’s junior college from Rexburg, Idaho, to Idaho Falls, as well as to establish a national network of junior colleges feeding upper-level undergraduates to BYU), but his contributions to the development of BYU cannot easily be over-stated.8

In the years prior to 1965, Wilkinson had usually relied on subordinates to help evaluate evidence in handling complaints against so-called liberalleaning faculty.9 With time, however, he grew frustrated that such efforts seemed only to produce anonymous or hearsay testimony. 10 What was needed, he came to conclude, was a more direct approach. Sometime by early April 1966, he decided to deliver a university-wide politically charged talk crafted to provoke comment from the school’s more outspoken faculty, then to enlist the aid of one or more students to report back on the in-class criticisms of selected teachers. Armed with eyewitness evidence of these teachers’ disloyalty, Wilkinson believed he would be best equipped to secure their dismissals.11

On April 9, 1966, he met with McKay to preview a draft of his controversial remarks, entitled “The Changing Nature of American Government from a Constitutional Republic to a Welfare State.” Wilkinson knew that McKay’s approval would help to ensure that any criticism of Wilkinson could be viewed as criticism of the LDS prophet. According to McKay’s diary, the increasingly infirm Church president “listened with interest to the talk President Wilkinson has prepared . . . against Communism or any issue [a]ffecting the freedom of the people of this country. I approved in general of the talk he will give.”12 The next week, Wilkinson met with Joseph T. Bentley, BYU’s sixty-year-old comptroller. 13 According to Bentley’s diary, Wilkinson said that as Bentley “knew several students had

7

been complaining about liberal teachers and teachers who criticized the brethren in their classes; that he was concerned about it as were some of the brethren. He mentioned that on Thursday [April 21] he was going to give a hard hitting speech in the forum assembly and undoubtedly some of the teachers wouldn’t like it. He wondered if there was some dependable student, a good conservative, who could find out what some of these professors were saying and especially their reaction to his talk.” Bentley, who shared much of Wilkinson’s politics, immediately thought of Stephen Hays Russell, a junior in economics whom Bentley had met the previous month and whom he described as “dependable[,] honest[,] and capable.” (Russell, a member of the John Birch Society, had recently received funding from the administration to attend a conservative economics symposium in New York.) Wilkinson then “suggested that I [Bentley] get [in] touch with him [Russell] and see what he could do.” Bentley shortly afterwards called “Steve and mentioned that ELW had wanted some information and asked if he could help and he said yes.”14 The next day, April 20, Wilkinson asked Bentley if “everything was fixed up with Steve to get [the] reaction of certain faculty members to his speech to be given tomorrow.” Bentley replied that he “had talked with Steven and Steve was working on the problem.” Evidently sensing the potential for negative fall-out, Wilkinson hinted at the need for deniability, stressing, as Bentley reported, that “of course he and I should be kept out of it.”15

The Joseph Smith Memorial Building on Brigham Yung University Campus.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Russell, who had independently voiced his own concerns to friends and associates regarding “liberal” faculty, subsequently recalled Bentley’s inviting him to his office and telling him that he had been “selected by the administration to assist in a confidential project.” Flattered and eager to please, Russell immediately agreed. Bentley also said that “President Wilkinson’s name must remain clear,” stipulating, as Russell interpreted Bentley’s instructions, that “if I got caught at this, official university reaction would be that I was working on my own.” Then, with Russell present, Bentley “commenced writing a list of ‘liberal professors,’” inviting Russell to contribute names as he “deemed proper.” The final list included political scientists Stewart L. Grow, Ray C. Hillam, Melvin P. Mabey, Louis C. Midgley, and Jesse R. Reeder; economists J. Kenneth Davies and Richard B. Wirthlin; and English professor Briant S. Jacobs. (Several--Hillam, Mabey, and Midgley—later wondered if they had been targeted because they had publicly supported Wilkinson’s Republican opponent in 1964.)16 Bentley next introduced Russell to his assistant, Lyman Durfee, who promised Russell whatever clerical help he needed. Russell remembered “Brother Bentley prais[ing] me for my conservatism ... That day in his office, I developed a deep respect and appreciation for a fine man.”17 Bentley, too, recalled the confidence Wilkinson and he had in Russell: “We seized upon the opportunity to use this young man to set up the monitoring groups.”18

Shortly after his meeting with Bentley, Russell contacted a number of like-minded friends and acquaintances whom he had met both in local meetings of the Birch Society and in the on-campus conservative-oriented Young Americans for Freedom club. He told them that “an important situation had arisen in which they could assist me in serving the administration.” The small group assembled on campus that evening, April 20, in room 370 of the Ernest L. Wilkinson Center. 19 Russell began with a prepared statement, stressed the need for absolute secrecy, and asked those who were not sympathetic to leave. When copies of the teaching schedules of the eight professors were distributed, only two or three of the students were enrolled in any of the classes. Russell consequently asked “for volunteers to monitor the other classes for [the] three periods following the president’s speech or until the professors made a statement on the address to the class whichever came first.” At least ten students--several of whom, like Russell, had already publicly and privately complained of certain faculty— volunteered: Everett Eugene Bryce, Lyle H. Burnett, Michel L. Call, Curt E. Conklin, Ronald Ira Hankin, Edward (Ted) G. Jacob, Lloyd L. Miller, Mark A. Skousen, Lisle H. Updike, and James H. Widenmann. Russell instructed the students to “bring their reports to [him]” the following week so that he could deliver them to Bentley as soon as possible.20

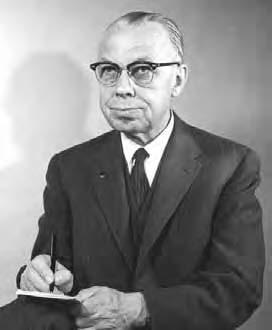

Ernest L. Wilkinson.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

As promised, Wilkinson delivered his no-pulledpunches address the next morning.21 “We had a small attendance,” he recorded in his diary,

“I am charged by the Board of Trustees,” Wilkinson announced near the beginning of his talk, “with the awesome mandate of making sure that the truth, as revealed and understood by the Lord’s prophets, is taught at this institution. . . .I know that there are some,” he continued, “who try to differentiate between advice given by our leaders on religious matters and advice which they allege pertains to political matters ... [I]f we are faithful members of the church, and if we want the blessings of liberty for ourselves and our posterity, we are under the same moral obligation to follow his advice on political as on religious matters.” Then, after listing the statements of several church presidents condemning socialism, he announced: “[W]e have for a period of at least 30 years been proceeding just about as fast as it is possible for a nation to proceed in the direction of the welfare state.” This rush was propelled, he contended, by such federal programs as: aid to education, unemployment compensation, food stamps, medicare, increasing minimum wages, federal housing, a cabinet position of Housing and Urban Development, price supports for agriculture, and federal intervention in labor disputes. To these he added the federal income tax, the Supreme Court’s emergence as “the god of our political life,” a runaway national debt, and the erosion of individual freedoms. The solution, he suggested, was three-fold: to “study diligently . . . the founding of our Republic and the teachings of our prophets,” to “live a righteous life,” and to elect “good and wise men to public office on the local and national level, who understand these principles and who will both defend and advance them.” “I am aware,” he closed, “that there will be some who will attempt to characterize this address as politically partisan. . . . I am concerned, not with parties, but with principles. . . . It is the duty of those of us who believe in the Constitution of our fathers to resist the welfare state at every turn in both parties.”23

Following Wilkinson’s talk, Russell’s group of students dutifully attended their assigned classes, took notes, then reported back to Russell, who prepared a typed, twelve-page summary.24 “I recall being asked to attend Ray Hillam’s ‘Current Affairs’ class,” Curt Conklin later wrote,

The Ernest L. Wilkinson Center was dedicated on April 3, 1965.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

At Bentley’s urging, Russell submitted his findings to Wilkinson on April 29. Russell said that he “read a few of the more explosive and derogatory remarks to [Wilkinson] and then handed him the report.” In his diary, Wilkinson characterized the document as “a voluntary report from certain students” and fumed that “some of the liberals on the campus are fighting mad because in my address to students I quoted Church authorities for my viewpoint. This shows that they think much more of their political convictions than they do of following their prophets—a situation which cannot be permitted on this campus.”26 Ostensibly busy with other matters, Wilkinson handed Russell’s report to BYU vice president and university counsel Clyde D. Sandgren and instructed him to meet with the students individually to verify their allegations. 27 Importantly, Wilkinson did not explain to the fifty-five-year-old Sandgren precisely how the student report came to be, merely that concerned students had voluntarily complained of their professors’ comments.28 Though Russell’s group ceased to function as an organized “ring” thereafter, at Bentley’s urging, Russell continued “to keep [his] ears open.” 29 Some professors also said they were visited by some students, and on at least one occasion, a teacher reported that a student recorded their conversation without his permission. The list of “questionable” professors expanded to include David Kirk Hart (political science), Russell Horiuchi (geography), Gordon Wagner (economics), and even social sciences dean John T. Bernhard. Any such reports were channeled to Wilkinson through Sandgren, who was expected to verify the statements.30

On July 14, 1966, one of Ray Hillam’s former evening students told him that Sandgren had asked him to confirm a number of allegations against Hillam made by James C. Vandygriff, a student who had taken one of Hillam’s political science classes and, like Stephen Russell, was a member of the local Birch Society. (Vandygriff had not been a member of Russell’s spy ring and his separate report on Hillam had been sent to Wilkinson’s office about two weeks after Russell’s composite report.)

Ray Hillam.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Hillam, a forty-one-year-old assistant professor and lay leader of a local LDS church congregation, immediately contacted Sandgren to lodge a protest. Sandgren expressed surprise that Hillam had not been told he was under investigation. He also mentioned that in addition to Vandygriff, Stephen Russell had raised some concerns about Hillam’s teaching, but also tried to assure Hillam that he was not “on trial.” Hillam then remembered his brother-in-law telling him the previous summer that Russell had commented on Hillam’s being on some kind of “hit list.” Skeptical of Sandgren’s reassurances, Hillam contacted his department chair, Edwin Morrell, who registered a personal protest with Wilkinson over the way the investigation of Hillam was being handled. According to Morrell, Wilkinson replied that he “should not object because surveillance [was] a common practice used by the FBI.”31 Wilkinson was convinced of Hillam’s guilt but wanted to avoid charges of personal animus and decided to turn the investigation over to the university’s three vice presidents: Earl C. Crockett (Academic), Ben E. Lewis (Executive), and Sandgren and “let them determine whether the charges are true and, if true, what [the] punishment should be.”32 “Because some of the complaints made against Ray Hillam involve alleged accusations which he has made against me,” Wilkinson explained to them, “it seems to me, although I think I could be objective in the matter, that it would be unfair to him for me to sit in judgment . . . Another reason why I have disqualified myself is that over the years a number of reports have come to me as to Hillam’s intense dislike of me.”33

In a written defense, Hillam not only denied the allegations but protested the “motives and methods” of the complaining students. He later met privately with Wilkinson, who insisted that students had not been organized to “spy on” the faculty and confidently predicted that Hillam’s charge of improper administrative procedure would be put to rest during the vice presidents’ impartial hearing. “I wondered at the time,” Hillam later recalled, “how his three vice-presidents could be as fair-minded with me as with him [i.e., Wilkinson]? I learned from the 90minute visit with Wilkinson that I was in serious trouble with him.”34

On August 15, Hillam, joined by Ed Morrell, met with the three vice presidents and Vandygriff.35 Hillam thought the meeting went “pretty well” and agreed to meet with the vice presidents again the next month. He also asked that Morrell be allowed to attend again. Sandgren consented but, when Wilkinson objected, asked Hillam not to press the matter. Hillam insisted, however, and the vice presidents eventually agreed that Morrell could observe but not participate.36 Soon rumors that “the administration had used students to spy on members of the faculty” began to circulate on campus.37 Though some school administrators were embarrassed by the resulting “unrest,” Wilkinson, writing in his diary in early September, refused to “apologize” or “get in a very defensive position.”38 On September 12, Wilkinson tried to reassure faculty members:

Joseph Bentley.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

“I now hear that I am bugging phones and have instituted an elaborate spy system. This latest rumor is as false as the others.”39 The next day, one of Russell’s spies, Ron Hankin, inadvertently revealed to a neighbor of Louis Midgley that Midgley had been one of several professors under scrutiny.40 Two days later, another of Hillam’s associates overheard Hankin relate virtually the same story. Other faculty also began to piece together past incidents that, at the time, had seemed inconsequential.41

Formal hearings into Hillam began on September 15, 1966. Hillam was confronted with a list of statements he had allegedly made several months earlier. He was charged with being pro-communist because he had reportedly endorsed the entrance of the People’s Republic of China into the United Nations; with having said that “BYU is becoming an evangelical college and a center for indoctrination for conservatism;” and that “within one month, BYU’s graduate school accreditation [would] either be taken away or [placed] on a three year probation.” (The school was awaiting the final verdict of a review of its academic programs conducted decennially by faculty from other universities.)42 During the hearing, Hillam questioned Stephen Russell, who was present, to find out how he had gathered his information. Russell denied any involvement in concerted surveillance activities. Towards the end of the hearing, however, Louis Midgley interrupted the meeting to tell Hillam, “I have [Ron Hankin] and he will tell everything.” At Hankin’s presence, Sandgren became “very uneasy,” according to Russell. Hankin then detailed his story of an “administration organized spy ring,” and when Ben Lewis asked, “Who is the administration?” Hankin replied that Sandgren should know since he had personally contacted the students to confirm their reports. Caught off-guard, Sandgren said, “Well, I only heard a rumor. That is why I called you in,” indicating Russell. Sandgren then asked Russell to explain “these accusations being made against the administration.” Flustered, Russell asked for three days to prepare a response. His request was granted.43

According to Russell, he immediately afterwards “dashed right to President Wilkinson’s office and told him of Hankin’s exposé.” Wilkinson looked at Russell and, “with an instructive tone of voice,” said, “You know of course this is the first I’ve heard of this group.” Wilkinson suggested that Russell contact Bentley for “advice on how to reply.” After Russell left, Wilkinson met with his vice presidents and was distressed to learn that both Lewis and Crockett evidently believed Hankin. He also telephoned Bentley and, “anxious to make sure Steve didn’t implicate others,” suggested that Russell be the administration’s “scapegoat.” Bentley refused, pointing out that Russell “had only done what [he] had been asked to do.” Wilkinson wanted to make certain that Bentley and he “understood the matter of Steve Russell the same. I suggested,” Bentley recorded, “that if we simply told the truth that would be all that would be necessary.” According to Russell, Bentley shortly afterwards confessed that he “was worried” about Wilkinson: “He’s involved and he’s scared.” Wilkinson thought that Russell needed to have a lawyer draft any response to the vice presidents; Bentley suggested H. Verlan Andersen, an attorney and the advisor to BYU’s Young Americans for Freedom club. Bentley, Anderson, and Russell subsequently met to “work out [Russell’s] five page reply.” In his response, Russell “criticized the manner in which Brother Sandgren had conducted the hearing” but avoided direct comment on a student “spy ring.” He charged instead that Hillam’s “shaky” evidence depended on the testimony of an unstable witness, Ronald Hankin.44

Meanwhile, Hillam met with a number of colleagues for a “strategy session.” During the meeting, Sandgren happened to telephone Hillam about meeting together in Sandgren’s office. Sandgren wanted Hillam to write a memorandum expressing appreciation that the hearing had been conducted fairly. “Like hell you’ll write a memo and get Sandgren off the hook,” one of Hillam’s colleagues protested.45 Following their meeting, the professors began conducting their own investigation. Hillam and Midgley tape-recorded an interview with Hankin and gathered testimonies from other students. 46 Richard Wirthlin went to Wilkinson four days later and accused Russell of “spying on teachers.” According to Wirthlin, Wilkinson “exploded” and demanded that he “give him all his evidence,” insisting that Hillam, not Russell, was the subject of the hearing and that the vice presidents had no right to look into allegations of spying. Annoyed, Wilkinson also threatened to investigate Wirthlin.47

Within the week, BYU economist Larry T. Wimmer enlisted the help of Edwin B. Firmage, a former LDS mission companion and grandson of the first counselor in the LDS Church’s First Presidency, Hugh B. Brown. Wimmer hoped to arrange a meeting for Hillam, Morrell, and Wirthlin with Brown, N. Eldon Tanner (McKay’s second counselor), and Church Apostle Harold B. Lee. Wimmer later explained that he initiated the conference because he believed Hillam “could not expect . . . a fair and impartial hearing before the vice presidents.” According to Hillam, both Church officials were “very interested in what we had to say. Elder Lee was with us every step and would, with a sigh, say, ‘One lie leads to another.’” At the conclusion, Tanner urged that the men keep complete records of their investigations. 48 Less than a week later, Hillam left for Vietnam on a Fulbright scholarship. On October 17, the three vice presidents issued their verdict, finding Hillam guilty of minor “indiscretions” and advising him to be more cautious in the future. Hillam’s counter-charge, that he had been the object of a group of student “spies” acting under instructions from the BYU administration, was not addressed. 49 Hillam was “depressed and furious” over the report; Wilkinson condemned it as “pretty much of a whitewash” for not “advocat[ing] [any] disciplinary action . . . yet admit[ing] that [Hillam] is largely responsible because of his inflammatory statements in class.” 50 Three days later, during another university wide faculty meeting, Wilkinson “reiterated” that he had “not knowingly” urged any students or others to report on faculty members. “I feel confident,” he said, “that no members of the Administrative Council would do so.”51

The next week on October 28, Ed Morrell met with the three vice presidents to protest the omission of Russell’s surveillance activities from their report. Initially, the vice presidents “suggested that Morrell not pursue the matter further” but, by November 3, they amended their findings to include, for the first time, an admission that Russell had, in fact, “organized a group of students to obtain reactions to President Wilkinson’s speech,” though again avoided mention of Wilkinson’s involvement.52 Wilkinson wrote to Hillam the next day to insist again that he had not encouraged “any students or others” to “spy” on the faculty since such activity would be an “improper administrative procedure.”53 Early the next year, Crockett mailed Hillam a teaching contract. Disappointed with what he felt was a minimal salary increase, Hillam responded that he would delay accepting the offer until after his own charges against the administration had been resolved.54 Others in the social sciences watched the showdown between Wilkinson and Hillam with growing dismay. Wirthlin, for example, decided to accept a position at Arizona State University.55 During a tense December 1966 meeting with social sciences faculty, Wilkinson fended off questions regarding his competence.56 Wilkinson concluded that without some kind of additional administrative intervention in faculty affairs, the campus could soon become a haven for “liberals,” and asked Verlan Andersen and W. Cleon Skousen, former Salt Lake City police chief and well-known conservative, to help draft a letter to the faculty from President McKay confirming “that [McKay] had told me many times, that he did not want socialism evaluated on our campus.”57

The Memorial Lounge in the Wilkinson Center in the mid-1960s.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Five months later in May 1967, Wilkinson met privately with McKay, to whom he described the recent spying incident as a minor difficulty in impressing upon the faculty that they “not advocate socialism or the welfare state.” McKay signed the letter Wilkinson’s aides had drafted, urging faculty in history, sociology, political science, and economics to “continuously teach [their] students the evils of socialism and the welfare state.”58 Early the next month, Wilkinson read the letter to his Board of Trustees. Elder Ezra Taft Benson moved that the board “go on record as wholeheartedlyapproving [the] letter as the policy of the Board of Trustees.” While some trustees, knowing of McKay’s health problems, questioned the letter’s authorship, Elder Marion G. Romney thought that the letter “could not have been drafted by a lawyer because it had the ring of the prophet all through it.” 59 McKay remained silent throughout much of the board’s deliberations. Finally, all voted in favor of the proposal, except Harold B. Lee, who abstained. When Wilkinson suggested that a clarifying statement be issued to explain the intent of the letter, the board decided that the letter “should stand alone.”60 Wilkinson subsequently agreed to delete from the letter references to specific campus departments as well as explicit injunctions prohibiting the teaching of socialism.61 As eventually distributed, the letter, bearing McKay’s signature, read, in part, “I am aware that a university has the responsibility of acquainting its students with the theories and doctrines which are prevalent in various disciplines, but I hope that no one on the faculty of Brigham Young University will advocate positions which cannot be harmonized with the views of every prophet of the church.”62

On February 28, 1967, Wilkinson learned that “some very rebellious students,” as he called them, undergraduates Ronald Hankin, David M. Sisson, and Colleen D. Stone, had contacted area newspapers and television and radio stations, announcing their intention to publicly broach the “spy ring” during a “Free Forum” sponsored by the Associated Students of Brigham Young University in the Wilkinson Center. Alarmed, Wilkinson immediately met with BYU’s dean of students, J. Elliot Cameron, and the chief of BYU security, Swen Nielsen. The university had assembled a list of “very serious” Honor Code-related “charges” against Hankin and Sisson, Wilkinson explained. Cameron and Nielsen would do well, he continued, to “interrogate [the students] so as to keep them occupied during the period they were going to make these false accusations.” Wilkinson discovered afterwards that neither Cameron nor Nielsen had been able to locate the three undergraduates prior to their public appearance and wondered if he was “getting the proper support from the dean of students.” 63 Without implicating other students, faculty, or administrators by name, Hankin told the crowd gathered in the Wilkinson Center’s Memorial Lounge on February 28 that he had been approached by “someone who was supposed to represent an administrative official” to obtain information on the “views” of certain BYU professors. Hankin and Stone were later interviewed on local television news programs.64

A BYU coed in front of a mirror in the Wilkinson Center to remind students to dress, groom, and behave properly.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

In the wake of Hankin’s public confession, campus officials scrambled to refute the charges, while local members of the Association of American University Professors asked the B oard of Trustees to investigate the allegations.65 Disillusionedafter nearly a week of official denials, Ed Morrell tried to resign as political science department chair but was refused. 66

Stephen Russell, hearing his name “on every front ... mentioned with derision” and feeling “the burden of the whole affair had been carried long enough,” decided to give “a detailed confession of the affair” to his local LDS bishop, Duane M. Laws.67 Russell and Laws met with Bentley on March 5, and the next day, at Bentley’s suggestion, with Wilkinson to discuss some kind of public statement “clarifying the whole matter.” When he learned how Russell’s and Laws’s meeting with Wilkinson had gone, Bentley feared that Wilkinson

The same day Wilkinson talked with Russell and Laws, he also hurriedly met with McKay to remind him of his previous instructions that “teachers ought not to object to [Wilkinson] knowing what they teach, nor to students reporting on the same so long as the Administrator is careful in properly evaluating such reports ... [and] that it is my [Wilkinson’s] responsibility to see that Atheism, Communism, and Socialism are not to be advocated by BYU teachers.”69 Wilkinson made sure that McKay signed a statement attesting to this understanding should he ever need to provide proof that he had merely been following McKay’s instructions. The next day, as Wilkinson and Bentley met to discuss the situation, N. Eldon Tanner telephoned to suggest that both men prepare statements of the spying incident. “Of course,” Wilkinson afterwards told Bentley, “this doesn’t mean that we can’t consult with each other.” “I d[o]n’t think we should,” Bentley replied. 70 Later that evening, Russell, at Laws’s urging, telephoned his thirty-one-year-old faculty advisor, Larry Wimmer, asking to meet. For the next two hours, Russell narrated his involvement in the spy ring. Wimmer then made arrangements for Russell to repeat his confession the next day to Tanner. When Wimmer and Russell, together with Laws, arrived in Tanner’s office, they were met also by Harold B. Lee, whom Tanner had invited. After some preliminaries, Russell again detailed his participation in the spy ring, with Lee occasionally asking questions. When Russell finished, Wimmer recalled, “Elder Lee’s first comments to Pres. Tanner and me were ‘And they spin their webs of deceit.’” As the men then prepared to leave, Lee said to them, “I want you to know that I am very concerned about the moral implications of what has happened at BYU,” adding that while he was not “currently in a position to respond to these events as I might wish,” if he ever were, there would be changes. Wimmer remembers departing “with great respect for President Tanner and Elder Lee, and the knowledge that finally we had been heard.”71

Clyde D. Sandgren, Brigham Young University general counsel.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

On March 11, less than two weeks after Hankin’s announcement, Wilkinson issued a formal public statement acknowledging “the organized surveillance of faculty by students,” accepting responsibility as president, and regretting any “misunderstanding and uneasiness which [had] been engendered.” However, he did not, as Bentley had guessed he would not, disclose the extent of his own involvement.72 In fact, Wilkinson privately told McKay that “a student had tried to organize some very Left-Wing organizations on the campus, and that because of the times President Wilkinson said that he had to be alert as to what some of the faculty members were teaching.” Wilkinson’s proposal, which McKay authorized, that they employ “a man with Federal Bureau of Investigation detective experience to exercise surveillance on the campus,” never materialized.73 Two days after Wilkinson’s public statement, Russell prepared his own double-spaced, thirteen-page typewritten notarized account. The next month, Hankin and Sisson were dismissed from school. Accusations surfaced that the two undergraduates were being punished for “whistleblowing,” but administrators insisted that the students’ disclosures regarding the spy incident were completely unrelated to their expulsion.74

In his report of the controversy prepared at Tanner’s request, dated April 17, Wilkinson admitted to having asked Bentley to recruit Russell and other students, while stressing that he did not know just how aggressively Russell would pursue his assignment. He characterized his initial meeting with Bentley as an “informal hasty conversation (one of hundreds which I will have every month) occurred over a year ago,” and admitted that “there may be a difference of memory between Brother Bentley and myself as to exactly what was said.”75 According to Wilkinson, he asked Bentley if “he knew of some reliable students who would advise as to comments of teachers. He replied that he knew a Stephen Russell, who was a very competent and reliable student whom he would ask to report to him.” “Since Stephen Russell and others had been previously complaining to Brother Bentley about what they both considered to be false teachings,” Wilkinson continued, “it was understood that they would report to him as to what their teachers said and that in the same way that I had not publicized the approval of my speech by President McKay, Brother Bentley was not to inform the students that the request came from me....76 [I]t now turns out,” Wilkinson emphasized, “that Stephen Russell got a group of students together and organized them to attend certain classes in some of which they were not regularly registered. This was never contemplated by me—I merely wanted reports of regular students from their regular classes.... Further,” he closed, “it was never contemplated that a group of students would be called together in a room and be organized for the purpose of obtaining information, even from their regular teachers.”77

In his own statement, dated March 8, Bentley made certain to emphasize Wilkinson’s participation even as he defended Russell’s character:

Brigham Young University President Ernest L. Wilkinson and student body officer Cam Caldwell prepare for the “Y Community Day” during which students and faculty painted and fixed up homes of needy persons.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

LDS officials, however concerned they may have been, chose not to pursue the delicate matter further, and Wilkinson was never asked to defend himself to his Board of Trustees. The letter he had had drafted for McKay, and adopted by the board, only hinted indirectly at the controversy. Hillam returned to BYU and resumed his teaching position in late September 1967. In Vietnam, he had been awarded a Medal of Honor by the South Vietnamese Army and a Civilian Patriotic Service award by the U.S. military.79 Wilkinson, however, continued to “wonder if I did right in persuading Hillam to come back by increasing his salary.”80 More and more alienated from his social sciences faculty, Wilkinson wanted to “find someone for a dean next year, who will put the spiritual approach above everything else.”81 Social sciences dean John Bernhard had resigned in early 1968 to accept the presidency of Western Illinois University.82 At the urging of Ezra Taft Benson, Wilkinson thought about asking one of BYU’s religion teachers to fill Bernhard’s vacancy. In fact, Wilkinson had come to trust his religion faculty more than his social sciences faculty. “They are as loyal and faithful and helpful as they can be,” he observed in his diary. “I hope you will see to it that the College of Religious Instruction, as a part of the gospel teachings, continues to decry the evils not only of communism but also of socialism,” he told religion administrators in February 1968. “It is ... just as appropriate to teach this in the College of Religious Instruction as it is in the Department of Political Science, and with more authority.”83

Some five months after his return to BYU, Hillam submitted to Vice Presidents Crockett, Lewis, and Sandgren a list of objections to their report in his case. Accompanied by his department chair and college dean, Hillam met with the vice presidents in March 1968; Joseph Bentley and Larry Wimmer also presented evidence to the vice presidents.84 Wilkinson met privately with Hillam at the end of the month, insisted that McKay had instructed him “to seek feedback from faculty on his [April 21, 1966] address,” agreed that “things got out of hand,” and, according to Hillam, apologized that students had monitored classes in which they had not been officially enrolled. 85 On May 10, 1968, the vice presidents amended their report to admit, for the first time, that Bentley, at Wilkinson’s request, had asked Russell to organize students to spy on teachers. They also addressed the issue of a cover-up, expressing “regret and disappointment that we learned—sixteen months after the case had been closed (1) that important facts pertaining thereto had been withheld from us, and (2) that although we had been appointed to determine the truth and to take final action in the matter, our effort is in that direction had covertly been challenged through the services of an attorney for a key witness, said attorney having been engaged with the knowledge of the one by whom we had been appointed and for whom we were conducting the investigation.” Finally, they recommended Hillam’s appointment as chair of the Department of Political Science as a “public expression of confidence.” 86 Administrators agreed, and the action was taken.87

LDS Church President David O. McKay visits with BYU students and faculty members following an assembly address on May 9, 1961.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Though largely pleased with the vice presidents’ revised report, Hillam pushed for “a further explanation” of the administration’s involvement in the surveillance. He asked that the activities of Bentley, Sandgren, Wilkinson, and Russell be, at least, generally outlined. Several drafts subsequently passed between Hillam and Sandgren. When finally completed on May 15, 1969, more than three years after Wilkinson first called Bentley into his office, the vice-presidents’ report vindicated Hillam of all charges and detailed the activities of Wilkinson, Bentley, Sandgren, and Russell. “[W]e individually and jointly regret,” the vice-presidents concluded, “that, although we were asked to make a full investigation and were clothed with authority to make a final decision with respect there to so far as the University Administration is concerned, important facts were withheld from us. ... we acted in good faith and were greatly embarrassed to learn that we had not been given full information.”88 By this time, however, at least four social sciences faculty who had tangled with Wilkinson over a variety of matters—Richard Poll, John Bernhard, Richard Wirthlin, and David Kirk Hart—had left, or were preparing to leave, BYU. Two others, besides J. Kenneth Davies and Hillam, were later appointed department chairs: Larry Wimmer (economics) and Russell Horiuchi (geography).

Chastened from all sides, Wilkinson pursued his conservative agenda a little less zealously over the next few years until his resignation in 1971. (He was also busy trying to stem a steady waning of support from trustees, notably Harold B. Lee, in the wake of McKay’s declining health.)89 Still, rumors of student spies continued to plague his administration, and Wilkinson still sometimes pressed associates to “keep in close touch” with “trouble making” faculty, suggesting in 1971 that Louis Midgley’s promotion to full professor be postponed “another year” to “see if he doesn’t mellow a little more.” 90 Following his resignation, Wilkinson remained defiant regarding the 1966 spy ring, carefully parsing his words a year before his death on April 6, 1978, to insist: “I never made one speech on campus about my political views, except to the extent that the Board of Trustees had previously declared. I didn’t want my administration here at BYU to be dove-tailed with politics. I did not authorize students to use tape recordings of any kind. Students were never organized by the administration to spy.”91 Bentley retired from BYU shortly after Wilkinson’s resignation and spent much of his remaining twenty years in various Church assignments, including serving as president of the LDS Church’s new Argentina East Mission (beginning in 1972) and with his wife later filling an LDS mission to Budapest, Hungary.92 He died on June 16, 1993, at age eighty-seven. Sandgren retired from BYU in 1975, practiced law privately, and died on December 21, 1989; he was seventy-nine. Of BYU’s other two vice-presidents during the spy ring, Crockett returned to teaching in 1968, retired in 1972, and died on December 2, 1975, at age seventy-two; Lewis retired in 1979, served as president of the Church’s England London Mission from 1979 to 1982, and died on October 24, 2005, at ninety-one. Hillam continued to teach political science at BYU until 1993. He died sixteen years later, after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease, on August 10, 2009, at age eighty-one. Stephen Russell graduated from BYU in economics in 1967. He went on to receive a master’s degree from the Air Force Institute of Technology in Dayton, Ohio, and a Ph.D. in business economics from Arizona State University in 1978. He taught at the Air Force Academy, Brigham Young University, Arizona State University, and the National War College in Washington, D.C. Since 1991, he has been on the faculty of the Goddard School of Business and Economics at Weber State University in Ogden. During the academic year 2003-2004, he was a visiting professor of economics at Brigham Young University–Hawaii.93

Army and Air Force ROTC students assembled in the Smoot Building quad for the lowering of the colors.

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Writing in 2001, Hillam suggested that during his two decades at BYU, Wilkinson came to view the school almost as “an extension of his persona.” Increasingly, Wilkinson cloaked the power of the BYU presidency “in his conservative political ideology and religious orthodoxy,” and following his failed 1964 Senate bid returned to the campus “with vengeance and with a political agenda.” Wilkinson may have been a “scrappy infighter” and “a genius in getting things done,” but, according to Hillam, because of excessive pride, he also “stumbled” and “erred.” “In our culture,” Hillam concluded, “a higher level of perfection is expected of those who are powerful and preside over us. . . . It is perhaps unfair to them as they are not without human weaknesses.” When Wilkinson balked at telling the complete truth about the 1966 BYU student spy ring, “he was compelled by the pressures of his status, which we conferred upon him, to cover himself. And once he dissembled he became a prisoner entrapped by a web of deceit. He was compelled to protect his power and preserve his pride.”94

NOTES

Gary James Bergera is managing director of the Smith-Pettit Foundation, Salt Lake City, Utah. He appreciates the advice and cooperation of Lavina Fielding Anderson, Curt E. Conklin, Duane M. Laws, Lewis C. Midgley, Stephen Hays Russell, Jonathan A. Stapley, Larry T. Wimmer, and Richard B. Wirthlin. All errors are Bergera’s own.

1 For Wilkinson’s Senate bid, see Gary James Bergera, “‘A Sad and Expensive Experience’: Ernest L. Wilkinson’s 1964 Bid for the U.S. Senate,” Utah Historical Quarterly 62 (Fall 1993): 304-24. For Wilkinson’s politics prior to 1964, see Gary James Bergera, “‘A Strange Phenomena’: Ernest L. Wilkinson, the LDS Church, and Utah Politics,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26 (Summer 1993): 89-115.

2 Wilkinson, “Report for the Board of Trustees on Surveillance of Teachers ...,” April 17, 1967 (Second Draft). Ernest L. Wilkinson Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. Copies of many of the documents cited in this article are now in possession of the Smith-Pettit Foundation, Salt Lake City, where they are available to other researchers.

3 Wilkinson to McKay, July 1, 1965, Wilkinson Papers. These “false doctrines” included, according to Wilkinson: that there “is no difference between Socialism and the United Order [an early LDS attempt at communal living] except for the religious aspect”; LDS leaders “are ignorant of economical and political problems”; there “is no need to worry anything about the national debt of this country”; and there “should be complete and unrestricted freedom of speech on the BYU campus” Wilkinson, “Draft of Report for the Board of Trustees on Surveillance of Teachers ...,” April 17, 1967 (First Draft), Wilkinson Papers.

4 Wilkinson Diary, January 2, April 7, 1965. Wilkinson Papers. “The political environment at BYU in the sixties was characterized by fear and anxiety,” remembered one faculty member. “The relationship between administrators and faculty was polarized.” Ray C. Hillam, “The BYU Spy Episode, 1966-68,” July 25, 2001,” 3, Ray C. Hillam Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. For more, see Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis, Brigham Young University: A House of Faith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985), 191-202.

5 For an earlier treatment, see Bergera and Priddis, Brigham Young University, 207-17. D. Michael Quinn has argued that LDS Church Apostle Ezra Taft Benson was involved in the spy ring. See Quinn, “Ezra Taft Benson and Mormon Political Conflicts,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26 (Summer 1993): 1- 87, esp. 50-55. I have been unable to substantiate any direct link between Benson and the spy ring.

6 An exception was Ezra Taft Benson, former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and, during the 1960s, a conservative anti-communist crusader. At the other end of the spectrum was Hugh B. Brown, a counselor in McKay’s First Presidency beginning in 1961 and life-long active Democrat. McKay usually supported both men’s freedom of speech.

7 For more on Wilkinson’s personality and managerial style, see Gary James Bergera, “Wilkinson the Man,” Sunstone 20 (July 1997): 29-41.

8 See Gary James Bergera, “Building Wilkinson’s University,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 30 (Fall 1997): 105-35.

9 See the examples in Bergera and Priddis, Brigham Young University, 202-207.

10 “Although these reports came to me from many sources,” Wilkinson later asserted, “they were generally told to me in confidence, and it was, therefore, difficult to use the information for the purpose of talking to the faculty members involved ...” Wilkinson, “Draft of Report,” Wilkinson Papers.

11 “I was anxious to know the comments and reactions of teachers,” he later explained, “some of whom had been accused of teaching opposite doctrines.” Wilkinson, “Draft of Report,” Wilkinson Papers.

12 David O. McKay, Diary, April 9, 1966, photocopy, Western Americana, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. McKay’s diary during this period was maintained by his personal secretary, and it is not always clear if McKay is speaking for himself. Because of this, the diary should be approached cautiously when looking for evidence of McKay’s own thoughts.

13 Joseph T. Bentley was born March 6, 1906. He graduated from BYU in 1928, joined BYU’s accounting department in 1953, earned a master’s degree from BYU in 1955, and was appointed accounting department chair that same year. He was made an assistant to Wilkinson in 1957.

14 Joseph T. Bentley, Diary, April 19, 1966, photocopy courtesy of the Smith-Pettit Foundation. Later, in 1982, Bentley recalled Wilkinson saying that his remarks would “rock the campus from one end to the other.” See Bentley, quoted in Ron Priddis, “BYU Spy Case Unshelved,” Seventh East Press, March 14, 1982.

15 Bentley, Diary, April 20, 1966. Wilkinson’s diary avoids direct mention of these conversations; Bentley’s does not.

16 Wilkinson’s campaign manager recalled that Wilkinson was “incensed to find such opposition from his faculty.” John T. Bernhard, quoted in Priddis, “BYU Spy Case Unshelved.”

17 Stephen Hays Russell, Statement, March 13, 1967. Photocopy, Smith-Pettit Foundation.

18 Bentley, in Priddis, “BYU Spy Case Unshelved.”

19 Lyman Durfee and a representative of the local Birch Society were also invited to attend the meeting but declined.

20 Combined from Russell, Statement; Ronald I. Hankin, To Whom It May Concern, September 17, 1966 (hereafter Hankin, Statement); and Ray C. Hillam, To Whom It May Concern, August 15, 1966, Hillam Papers. Some estimates place the number of students at fifteen. Five of the students—Burnett, Call, Conklin, Hankin, and Jacob—were members of the YAF Club. Later, it was reported that Russell had told the students that Hillam, a graduate of American University (Washington, D.C.) who had joined the BYU faculty in 1960, was “on the top of the [BYU administration’s] list. ... They wanted to know about him and they [were] going to get him.” Russell subsequently explained that the previous year, 1965, he had, in fact, made such a statement, but that it had actually reflected the views of the president of Provo’s chapter of the John Birch Society. He had, Russell said, “in a moment of weakness and to project my perceived self-importance ... made [the local Birch Society’s] list the Administration’s.” (Russell, “Comments ...,” dated December 23, 1986, attached to Russell to Bergera, January 5, 1987, Smith-Pettit Foundation.

21 See “The Changing Nature of American Government from a Constitutional Republic to a Welfare State,” April 21, 1966, Perry Special Collections; reprinted in Edwin J. Butterworth and David H. Yarn, eds., Earnestly Yours: Selected Addresses of Dr. Ernest L. Wilkinson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1971), 30-55.

22 Wilkinson, Diary, April 21, 1966, Wilkinson Papers. Close to two-thirds of the talk repeated much of Wilkinson’s 1965 BYU commencement address, “The Decline and Possible Fall of the American Republic,” Wilkinson Papers.

23 See Wilkinson, “Changing Nature,” 2, 3, 8, 9,10-14, 19, 21.

24 Russell later insisted that he told the students to “silently monitor [the] classes.” Russell, “Comments,” Hillam Papers. Russell also acknowledged that some students may have asked leading questions.

25 “To say I feel badly about my participation in the Spy Scandal ...,” Conklin later wrote, “is an understatement ...” Conklin to the editor, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26 (Winter 1993): vii-viii. In addition, Call and Hankin monitored Wirthlin, Hankin and Updike monitored Reeder, and Skousen monitored Grow and Midgley.

26 Wilkinson, Diary, April 29, 1966.

27 Clyde D. Sandgren was born September 5, 1910. He graduated from BYU in 1932 in music. He attended New York University and the Juilliard School of Music, then received a law degree from St. John’s University (New York). In addition to acting as BYU counsel, he was also secretary of the school’s Board of Trustees. He may be best remembered for having composed BYU’s “Cougar Fight Song” (1932).

28 Later, from conversations with Russell, Sandgren learned about the student group and targeted professors. See Russell, Statement.

29 Russell, “Comments.” Russell said that he personally was aware of only two instances in which reports on faculty were forwarded to Wilkinson.

30 Hankin, Statement; Russell, Statement; Wilkinson, “Report for the Board of Trustees,” Wilkinson Papers; Richard B. Wirthlin to Bentley, May 25, 1966, Bentley to Wirthlin, June 6, 1966, and Russell to Wilkinson, June 3, 1966, Hillam Papers.

31 Hillam, “Notes regarding an interview with President Clyde D. Sandgren,” July 18, 1966; Hillam, “Telephone conversation with President Sandgren,” July 19, 1966; John P. Sanders, Statement, July 20, 1966; Russell, “Comments”; Wilkinson, Diary, July 20, 1966; Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 6, Hillam Papers. See also Wilkinson, memo of conference with Morrell, July 20, 1966. When Hillam’s colleague Louis Midgley learned of the spying, he confronted Wilkinson during a chance encounter on campus, asking, “Why are you investigating Ray Hillam? I have stronger feelings of hostility toward you than he does.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 5.

32 Wilkinson to Sandgren, Crockett, and Lewis, July 21, 1966. See also Wilkinson to Sandgren, Crockett, and Lewis, September 19, 1966. Earl C. Crockett was born May 13, 1903. He graduated from the University of Utah (economics, 1927) and the University of California, Berkeley (1931). He joined BYU’s economics faculty in 1957, served as academic vice-president for eleven years, and was acting president during Wilkinson’s Senate bid (1964). Ben E. Lewis was born November 16, 1913. He graduated from BYU in 1940 and from the University of Denver in 1942. Following a career with Hot Shoppes, Inc., he joined the BYU administration in 1952. He served as a school administrator for twenty-seven years, and was awarded an honorary doctor of business degree in 1970.

33 Wilkinson to Sandgren, Crockett, and Lewis, July 21, 1966. Hillam later reminisced: “It hurt when he [Wilkinson] told me that he thought I did not like him.” “Spy Episode,” 28.

34 Hillam to Sandgren, July 22, 1966; Hillam, “Conversation with President Wilkinson,” July 23, 1966 (cf. Wilkinson, Diary, July 23, 1966); Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 6.

35 About a week before this, Hillam, accompanied by Wirthlin, met with Hugh B. Brown, First Counselor to McKay. “Do not surrender any ground to the vice-presidents as they are Wilkinson’s men and will prepare a case against you,” Brown advised Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 7; Hillam, Interview with President Hugh B. Brown, August 9, 1966, Hillam Papers.

36 Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 8; Sandgren to Hillam, August 30, 1966; Hillam, “Telephone conversation with President Sandgren,” September 12, 1966; Hillam, “Interview with President Sandgren,” September 13, 1966, Hillam Papers.

37 See, for example, J. Kenneth Davies, To Whom It May Concern, July 26, 1966; Hillam to Morrell, July 31, 1966; John P. Sanders, To Whom It May Concern, August 5, 1966; Russell Horiuchi, To Whom It May Concern, August 11, 1966; Gordon Wagner, To Whom It May Concern, August 11, 1966; Midgely to Hillam, August 11, 1966; Hillam, To Whom It May Concern, August 12, 1966; Richard Wirthlin, To Whom It May Concern, August 12, 1966; David Hart, Statement, August 13, 1966; Richard Poll to Hillam, September 12, 1966; and Jesse Reeder, Statement, September 21, 1966, Hillam Papers.

38 Wilkinson, Diary, September 10, 1966. See also Hillam, “Telephone conversation with Lynn Southam, BYU Student Body President,” September 12, 1966, Hillam Papers.

39 Wilkinson, “Address of Ernest L. Wilkinson to B.Y.U. Faculty,” September 12, 1966. During this period, Hillam declined to discuss the issue publicly. Hillam, “Telephone conversation with a representative of KUTV,” September 13, 1966; Hillam, “Telephone conversation with Ernest L. Wilkinson immediately after conversation with representative of KUTV,” September 13, 1966, Hillam Papers.

40 “I made a horrendous error in character judgment,” Russell later commented, “when I invited ... Ron Hankin to join the group.” Russell, “Comments.” “I think the term ‘misfit’ probably does the best justice to [Hankin],” Curt Conklin reminisced. Conklin to Bergera, Smith-Pettit Foundation.

41 Midgley to Wilkinson, September 13, 1966; Hillam, To Whom It May Concern, September 15, 1966; Steve Gilliland to Midgley, September 15, 1966, Hillam Papers.

42 See Bergera and Priddis, Brigham Young University, 217-19.

43 Russell, Statement; “Minutes from the Vandygriff and Russell Hearings,” September 15, 1966. Two days later, Midgley and Hillam conducted an in-depth interview with Hankin regarding the spy ring (see Hankin, Statement; the typescript of Hankin’s Statement runs fourteen single-spaced pages). “Eureka!” Hillam later wrote. “It was a dramatic event. We had proved our case. There WAS a conspiracy. . . . I thought the Hankin revelation would end things. What a stroke of luck! I thought it was providence. As for ending things, I was naïve.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 11; emphasis in original.

44 Russell, Statement; Bentley, Diary, September 17, September 18, September 19, September 20, 1966. “On many occasions after the expose,” Russell later recalled, “he [Bentley] said, ‘We must stick to the truth at all costs.’” Russell, “Comments.” Bentley thought that Wilkinson, during this period, did not “have the old fight he used to have.”Diary, September 29, 1966.

45 Hillam, “Conversation with President Sandgren,” September 16, 1966. See also Hillam to Ben E. Lewis, September 16, 1966, not sent; “BYU Spy Case Unshelved.” Hillam later decided that Sandgren’s request for a memo reflected “Sandgren’s fear of Wilkinson.”Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 28.

46 See Hankin, Statement; Ronald I. Hankin and David M. Sisson, To Whom It May Concern, September 17, 1966; David M. Sisson, To Whom It May Concern, September 17, 1966; Wimmer, Statement, January 30, 1968, Hillam Papers.

47 Richard Wirthlin, quoted in Priddis, “BYU Spy Case Unshelved”; Wilkinson, Diary, September 19, 1966; Wilkinson, memo re: conference with Richard Wirthlin, September 20, 1966, Wilkinson Papers.

48 Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 13.

49 Crockett, Lewis, and Sandgren, “Report, Findings of Fact, Conclusions and Recommendations,” October 17, 1966. cf. Crockett, Lewis, and Sandgren to Hillam, October 20, 1966. Hillam Papers.

50 Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 15; Wilkinson, Diary, October 20, 1966. Bentley lamented: “This whole matter of Hillam & Steve Russell and all others [is] a complete flop. ELW has let liberals completely dominate the situation so it appears that they can get away with anything.” Bentley, Diary, October 5, 1966.

51 BYU Faculty Minutes, October 20, 1966, Perry Special Collections.

52 Midgley to Hillam, November 11, 1966; Crockett, Lewis, and Sandgren to Hillam, November 3, 1966, Hillam Papers.

53 Wilkinson to Hillam, November 4, 1966, Hillam Papers.

54 Crockett to Hillam, January 27, 1967; Hillam to Crockett, February 1967, Hillam Papers.

55 Wirthlin to Hillam, December 9, 1966, Hillam Papers. Wirthlin wrote: “I am convinced that a person can double his salary by leaving BYU and reduce greatly the potential of having ulcers and a heart attack before one is 45.” At the time Wirthlin was thirty-five. He went on to become a prominent pollster and also worked on Ronald Reagan’s two successful U.S. Presidential campaigns. From 1996 to 2001, he was a member of the LDS Church’s Second Quorum of the Seventy.

56 Social Sciences Faculty, Minutes, December 13, 1966, Perry Special Collections; cf. Richard L. Bushman to Robert K. Thomas, December 30, 1966; and J. Weldon Moffitt to Wilkinson, December 22, 1966, Wilkinson Papers.

57 Wilkinson, Diary, December 13-25, 1966. At Wilkinson’s prompting, BYU’s trustees later repeated their instructions that Wilkinson “engage only those teachers whose religious, social and economic views accord with those of the president of the church ...” Board of Trustees, Executive Committee, Minutes, February 23, 1967; Board of Trustees, Minutes, May 25, 1967.

58 Wilkinson, Diary, May 14, June 7, 1967; Wilkinson, memo of conference with McKay, May 21, 1967; McKay to Wilkinson, May 25, 1967, Wilkinson Papers.

59 “I approved and signed that letter—and it is mine,” McKay subsequently insisted. McKay, Diary, June 16, 1967.

60 Board of Trustees Minutes, June 7, 1967. Wilkinson in his diary referred to this meeting as “a historic occasion” (June 7, 1967). Trustees also disapproved of a BYU faculty senate, affirmed that Wilkinson retain “the right of appointment of faculty members,” affirmed that trustees “have final authority” regarding “curriculum matters,” and affirmed the school’s policy of not having “legal lifetime tenure.”

61 Wilkinson, Diary, February 27, 1968. See also McKay, Diary, June 12, June 14, June 16, 1967, February 27, 1968. Many of the changes to the letter were recommended by LDS Apostle Richard L. Evans.

62 Ernest L. Wilkinson et al., ed(s)., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 4 Vols. (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1975-76), 4:544-45. Copies of the final version of the letter were sent to all faculty with their teaching contracts from 1968 to 1971.

63 Wilkinson, Diary, February 28, 1967.

64 “Free Forum Filled with ‘Charges,’” Daily Universe, March 1, 1967. cf. Jeri Bowne to Editor, Daily Universe, March 2, 1967); “BYU Denies Campus ‘Spy’ Story,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 1, 1967. News of the incident reached a national audience by the end of the month: “Spies, J.G.,” Newsweek, March 27, 1967, 112.

65 “BYU Denies Campus ‘Spy’ Story” and “Truth Should Back Viewpoint,” Daily Universe, March 1, 1967.

66 Wilkinson, Diary, March 1-11, 1967. For the denials, see, for example, Wilkinson to McKay, March 7, 1967: “there is probably some truth to the charge that certain students had been organized to report on certain teachers, and that the Administration may have advertently or inadvertently encouraged these students although not in the manner it took place.”

67 Russell, Statement.

68 Bentley, Diary, March 5-6, 1967. Bentley subsequently summarized that Laws and Russell “reported to me that President Wilkinson was evasive and stated that he couldn’t remember some of the actual happenings with regard to the matter and was somewhat contradictory when he was reminded by Steve that he (Steve) had actually handed him the reports given him by the students, and that Steve and President Wilkinson had talked about it.” Bentley, “Confidential Statement Re: So Called ‘Spy Ring’ on the BYU Campus,” March 8, 1967, Smith-Pettit Foundation. Wilkinson’s diary for March 6 does not mention meeting with Russell and Laws, merely that he “found out that during the three days I had been away from campus there had been a great agitation by a noisey few, over the question of free speech, a so-called spy ring of students, and a great many other things.” Laws was a member of BYU’s child development and family relations department, and later taught at Eastern Michigan University,Ypsilanti, from 1971 to 1994.

69 Wilkinson to McKay, March 7, 1967, in McKay, Diary, March 6, 1967. Wilkinson told Bentley he had been “called to Salt Lake by the brethren and when they call ‘I have to go.’” Bentley was skeptical: “I really doubt he was called but think he went on his own.” Bentley, Diary, March 7, 1967. Wilkinson’s diary for March 6 confirms that he “decided to go to Salt Lake where I had a conference with President McKay ...”

70 Bentley, Diary, March 7, 1967. Coincidentally, that same day, Earl Crockett sent Hillam a second teaching contract, now offering him a salary increase more comparable to that of other faculty of his rank. Crockett to Hillam, March 7, 1967, Hillam Papers.

71 Wimmer, “The BYU Spy Episode of 1965-66: My Part,” April 13, 2010, 4, copy Smith-Pettit Foundation. Wimmer remained at BYU for the next four decades, and is currently the school’s Warren and Wilson Dusenberry University Professor of Economics, Emeritus. For Russell’s account of this meeting, see Russell, “Personal History of Stephen Hays Russell,” 1983, 109-10. Russell later added: “I felt an urgency to lay out every detail of the affair to Wimmer for two reasons: (1) Wilkinson was not willing to put out a full disclosure and I felt the moral obligation to do so: (2) Wimmer’s close friend Edwin Brown Firmage had taken it upon himself to plead strongly with my fiancé (who was his mission convert) to terminate her relationship with me. I was humbled and contrite.”Russell, “Comments.”

72 Wilkinson to All Members of the Faculty, March 11, 1967; “Statements Out on ‘Spy Ring,’” Daily Universe, March 15, 1967.

73 McKay, Diary, March 15, 1967. Wilkinson may have had W. Cleon Skousen in mind.

74 Wilkinson, Diary, April 12, 26, 1967; “Standards Clarifies Hankin Suspension,” Daily Universe, April 14, 1967; Wilkinson, “Report for the Board of Trustees.” Both Hankin and Sisson petitioned the Board of Trustees for a rehearing but were denied. Shortly afterwards, Hankin accosted Wilkinson on campus; and Sisson threatened Wilkinson and was subsequently arrested for burglary (Wilkinson, Diary, May 8, 18-19, July 30, August 6-7, 1967; see also J. Elliot Cameron to Wilkinson, July 19, 1967). “Hankin was many things,” Hillam later wrote. “He was bright, articulate, and spoke with conviction. He was a ‘true believer’ and thought as a spy that he was engaged in a ‘noble cause.’ But he may have been neurotic. However, to the discomfort of Russell and Wilkinson, he was correct about the spying, the noble cause, and all that stuff.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 17.

75 “I ... would not be surprised if Bentley’s version is different than mine,” Wilkinson told Robert Thomas. “I have found several instances recently in other areas where he went beyond my instructions to him.” Memo dated April 20, 1967, Wilkinson Papers.

76 Russell later commented, generously, of Wilkinson that “he truly felt the interest of Brigham Young University would best be served by his protective denials.” Russell, “Comments.”

77 Wilkinson, “Draft of Report.”

78 Bentley, “Confidential Statement.”

79 “Hillam Back from Vietnam with Honor,” Daily Universe, October 3, 1967. See also “He Serves His Church and His Country,” Church News, Deseret News, September 9, 1967.

80 Wilkinson to Thomas, September 21, 1967, Wilkinson Papers.

81 Wilkinson, Diary, May 10, 1967, April 2, 1968, February 13, 1969.

82 “Dr. Bernhard Heads Illinois University,” Daily Universe, March 21, 1968. University of Utah alumnus Martin B. Hickman was eventually appointed as dean of the College of Social Sciences, a position he held for the next seventeen years.

83 Board of Trustees, Executive Committee, Minutes, April 25, 1968; Board of Trustees, Minutes, May 1, 1968, cf. Wilkinson, Diary, April 12, 1968; Wilkinson to Daniel Ludlow, Chauncey Riddle, and Roy Doxey, February 19, 1968.

84 Bentley, about this time, also privately apologized to Hillam “for participating in the spying. ... It was a tender moment,” Hillam recalled, “and I have never forgotten it.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 22.

85 Hillam, memo, March 31, 1968; Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 24; Wilkinson, Diary, March 26, April 1, May 10, 1968. “Will I ever get an apology out of him [Wilkinson]?” Hillam wondered. “He did say we have both made mistakes. But it was clear that he had convinced himself that he was not that involved.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 24.

86 Crockett, Lewis, and Sandgren, “Amended Report, Findings of Fact, Conclusions and Recommendations,” May 10, 1968. Wilkinson could have disbanded the vice presidents’ committee at any time, but did not—perhaps, as Louis Midgley observed (in conversation with Bergera, February 3, 2010), out of an over-riding allegiance to American constitutional law.

87 Robert K. Thomas to Wilkinson, May 15, 1968, Wilkinson Papers.

88 Hillam to John T. Bernhard, July 3, 1968; Hillam to Sandgren, October 7, 1968; Sandgren to Hillam, November 27, 1968, and attachment; Hillam to Sandgren, April 25, 1969, and attachment; Sandgren to Hillam, May 13, June 4, 1969. “I have come to terms with my Wilkinson problem,” Hillam wrote in 2001. “I have no malice toward him. ... my idealism was replaced by guarded realism. ... I learned about university politics and the concepts of power, pride, fear, and distrust.” Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 30, 31.

89 See Gary James Bergera, “Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education,” Journal of Mormon History 22 (Spring 1996): 157-72.

90 Wilkinson to Robert K. Thomas, April 29, 1970; Thomas, minutes of a meeting with Wilkinson, May 4, 1970; Wilkinson to Thomas and Robert J. Smith, March 2, 1971. For later allegations of spying, see Phares Woods, Statement, May 27, 1969.

91 Wilkinson, interview with Bergera, February 1977, notes, Smith-Pettit Foundation. Both the fourand one-volume editions of BYU’s official history blamed the episode on overzealous students. Hillam protested: “The dishonesty which accompanies the ‘cover up’ is more distressing than the spying itself.” Hillam to Wilkinson, W. Cleon Skousen, Leonard J. Arrington, and Bruce C. Hafen, November 1, 1976; Vern Anderson, “Y. Teachers Blast ‘Spy Scandal Coverup,’” Salt Lake Tribune, December 24, 1976.

92 Bentley and his wife also presided over the Provo LDS Temple from 1976 to 1978. Joseph T. Bentley, Life and Family of Joseph T. Bentley: An Autobiography (Privately Published, 1981), 142.

93 Stephen Russell believes that “if, in Bentley’s office in April of 1966, Bentley and I had responded literally and noncreatively to Wilkinson’s request, no ‘1966 Spy Ring’ would have emerged.” Russell,

“Comments.” Of his own experience, Curt Conklin writes, “[T]hose of us involved were young . . . Back then, like a lot of others that age, I knew all the answers, trouble is, I didn’t know the questions!” Conklin to Bergera, Smith-Pettit Foundation. Conklin retired from BYU employ in 2009 after thirty-seven years as a librarian in the university’s J. Reuben Clark Law School.

94 Hillam, “Spy Episode,” 27, 28, 29, 30. Midgley refers to the spy ring and especially the cover-up as “Wilkinson’s Watergate.” Conversation with Bergera, February 8, 2010.