49 minute read

Charcoal

This map shows Utah sites with constructed kilns, as well as sites associated with Utah resources.

Douglas H. Page

Charcoal

and Its Role in Utah Mining History

BY DOUGLAS H. PAGE JR., SARAH E. PAGE, THOMAS J. STRAKA, AND NATHAN D. THOMAS

Most Utahns know about the importance of mining in the state’s early history. They are often surprised to learn that the charcoal industry was also a fascinating and critical part of Utah’s history. Charcoal’s role as the fuel for Utah’s early mining industry and its impact on the state’s forests are often overlooked. Charcoal production itself was one of Utah’s earliest industries. One author called it the “West’s forgotten industry,” and it seems forgotten in Utah, except where its remnants are scattered across the landscape. 1 In this article we describe the primary charcoal production sites and regions and the condition of the charcoal kilns that remain as ghosts of the forgotten industry in Utah. We also provide background on the mining activity they supported and their role in powering the mining industry in the state. Unfortunately, in many cases we describe areas that once contained immense industrial endeavors that produced massive amounts of charcoal but that now contain few visible remnants.

Charcoal has always been a preferred source of heat in metallurgy. It is the solid residue produced by carbonization or pyrolization when wood is “burned” in a confined space with limited (controlled) air at a high temperature (300ºC or 572ºF). Normally, in the open air, wood burns down to a small residue of ash. When carbonized with limited air, wood chemically decomposes instead into charcoal. 2 Carbonization removes moisture and impurities, leaving a low ash content and low amount of trace elements such as sulfur and phosphorus. Thus it produces a “clean” heat that enhances the quality and malleability of a smelter’s output. 3 Charcoal burns much hotter than wood (with twice the heat of seasoned wood) and more evenly and consistently than wood. It produces the intense heat needed to reduce iron oxide ore into pig iron (2,600 to 3,000ºF). Moreover, charcoal is much easier than wood to transport and store because it has one-third of the weight and one-half of the volume of wood. Charcoal burners produced the ideal fuel for the smelting process. As wood became depleted near the smelters, woodcutters had to transport wood over greater distances and supply and transportation issues caused prices to rise. 4 Thus, charcoal developed as its own industry, with its own set of complications, such as labor costs, raw material supply, and negotiations with teamsters.

Charcoal represented the largest expense of a typical smelter. A cord of wood could produce twenty-five to thirty-five bushels of charcoal, with the price per bushel dependent on variables such as quality and transport distance. Supply and demand, of course, greatly influenced price, which could vary from eight cents to sixty-five cents, while twenty-five to thirty cents was more normal. Some smelters used tremendous amounts of charcoal. For instance, the Bristol and Daggett smelter at Brigham Canyon used fifty-nine bushels to the ton of ore in 1872, and the Winnamuck Furnace accounted for 56 percent of its operating expense from charcoal. 5 The difference of a single cent could make a great difference to a charcoal burner. The largest charcoal market in Nevada experienced a small war in 1879 at the market’s center in Eureka that involved the governor calling out the state militia and resulted in the death of five charcoal burners and the wounding of six more by deputy sheriffs. All this was over a strike for two additional cents per bushel. 6 The industry has a history that has been called “reviled, greedy, troublesome, wasteful, and corrupt,” 7 and it was all those, plus fascinating. We attempt to relay some of the fascinating aspect of the industry.

Utah’s mining industry boomed after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869; this in turn created a need for charcoal. The state’s mining history began in the early 1850s with a few short-lived iron missions in southern Utah. The first commercial mining activity began in the early 1860s when Patrick Connor’s California volunteer soldiers became prospectors and made the first precious metal strikes in the Wasatch and Oquirrh mountains. Until 1869, the combination of high transportation and labor costs, charcoal scarcity, and the lack of experienced miners limited development. After 1869, smelting furnaces soon followed with new access to the railroads. 8 Until about 1875, charcoal was the sole fuel of the Great Basin smelters, and it remained a primary fuel well into the twentieth century when coal and coke gained importance as smelter fuels. 9

Utah mines needed charcoal, yet it could be a costly and difficult commodity to obtain. An 1873 federal report on mining in the Great Basin discussed the importance of charcoal to the state’s mining industry and its smelters; the report noted the tendency of charcoal prices to become precariously high, threatening the profitability of the smelters. 10 Most of the charcoal in Utah at the time of the report was transported by rail from the Sierra Nevada in California, though some was produced in-state in the Wasatch Mountains and the districts farther south where pinyon pine is found. The California charcoal sold for twenty-five cents per bushel and the local, inferior charcoal sold for twenty-two to thirty cents per bushel. The smelter owners considered these charcoal prices to be high but the charcoal burners were close to abandoning the business for lack of a profit. It was, in other words, a difficult proposition on both ends of the trade. The report stated that:

Thus, though Utah miners needed charcoal for their smelters, its cost could prove troublesome.

The eleven sites associated with the Frisco Mining District offer some of the best remaining charcoal kilns in the state.

Douglas H. Page

Until the 1870s, most of the Great Basin charcoal was produced in charcoal pits (also called meilers) or soil-covered piles of wood. 12 Charcoal burners located pits in the wooded areas near smelters. For those who know what to look for, the remains of these pits are relatively easy to recognize in the woods: they are circular areas that still contain charcoal residue and are always located on very flat, level ground. 13 The word pit is a misnomer; a charcoal pit is entirely above ground, built on a clean, level surface called a hearth. Most often woodcutters formed four-foot lengths of wood into a pile that was centered on the thirty- to forty-foot diameter hearth. A typical pit had three tiers of piled wood. The charcoal burner then covered the wood with leaves or other vegetative debris and earth. Once sealed, it was ready to be fired with hot coals from the camp fire. Vents or holes at the bottom controlled air circulation. The pit might burn for a week to ten days; it was extinguished when the wood had completely carbonized. It remained closed for cooling for a few days, when the burner raked the charcoal out. 14 If the charcoal pits were a distance from the furnace, teamsters would haul the charcoal to a charcoal house located at the furnace. Experienced Italian charcoal burners near Eureka, Nevada, had a reputation for producing the best charcoal in the Great Basin. Burners in some Utah locations, on the other hand, reportedly made the poorest local charcoal. The 1873 federal report noted that Utah charcoal burners composed pits of varying sizes and primarily from “cedar, quaking aspen, mountain mahogany, and nut pine wood.” A pit made of one hundred cords of green wood would burn for “fifteen or twenty days, and yield from 2,500 to 3,500 bushels of charcoal.” 15

In the early 1870s, charcoal burners constructed kilns of stone and, less often, brick to supplement charcoal production from pits. The principles used to convert wood to charcoal were identical to those used in the pits. Instead of a vegetation and dirt covering to limit oxygen, the kiln itself provided the protective covering. In Utah, kilns operated at their prime from 1879 to 1884. 16 Utah still has a fair number of these ghosts of the mining era, clustered near the old mining regions.

People associated with charcoal production considered kilns to be an improvement over pits, and the subject received much discussion, especially prior to 1880. Some researchers suggested the kilns were necessary for processing some types of wood that required higher temperatures to burn properly. 17 The key factor, however, was financial. Though the kilns cost more to construct and could not be moved like a pit, they offered advantages that incrementally exceeded the benefit of a charcoal pit’s mobility. 18 Because kilns were permanent structures, the collier (or charcoal burner) had complete control of all the steps in the burning process.

This improved both the quality and the density of the charcoal, led to increased and faster yields, and reduced labor requirements. Kilns decreased the chances of accidentally burning the wood completely and increased the uniformity of the burning process. Moreover, kilns yielded up to 20 to 25 percent more charcoal than pits. That charcoal was denser and cleaner (because it did not contain the sand and dirt from a pit covering) and it cost one-third less to produce. Additionally, some charcoal burners using pits transported their product large distances to the furnaces, which could cause a loss of 10 to 15 percent due to travel over rough roads. This meant an overall yield advantage of perhaps 33 percent for kilns over pit production. 19

The skilled labor needed to build the kilns would be difficult to duplicate today. Stone charcoal kiln construction required specialized skills that came with Europe immigrants, such as the highly skilled carbonari from Italy and the Swiss-Italian border region. Charcoal kilns take a number of shapes: rectangular, square, round, conical, or dome shaped. Most kilns in Utah and the Great Basin tend toward the dome or beehive shape, though several are conical. Table one summarizes charcoal kiln locations in Utah.

The design of the beehive kiln is credited to J. C. Cameron, an engineer who introduced it in Marquette County, Michigan, in 1868. Cameron described it as a “a parabolic dome, with a base of twenty to twenty-four feet in diameter and an altitude of nineteen to twenty-two feet.” The beehive kiln had an estimated construction cost of less than $700. Although construction methods might have varied, Cameron’s illustrations show an external scaffolding that supported a series of internal scaffolds through the top of the kiln as it was being constructed. This internal scaffolding was laid against the walls that slanted inward toward the top of the kiln. 20 The prevalence of parabolic kilns in Utah—the

TABLE 1. UTAH CHARCOAL KILNS *

Beehive State- is evidenced by use of the "beehive kiln" as the generic term for charcoal kilns in the state. Just so, most historical markers and summaries call charcoal kilns "beehive kilns." Some of the best examples of parabolic kilns are the five kilns at the Frisco town site. The Iron City and Leeds Creek kilns are good examples of conical kilns.

Charcoal kilns were made of stone, fire brick, adobe, or a combination of these materials. The right to manufacture the beehive kiln commercially belonged to the Morris and Evans partnership in Salt Lake City, a firm that was also the sole producer of fire bricks in Utah, according to the 1885 census. 21 The walls of a kiln get thinner as it gets taller; the base may be twenty-five to thirty inches thick and the top only twelve to eighteen inches thick. There were usually three primary openings: typically a very small one at the top used to draw in air and sometimes to fire the charge, a three-byfour foot opening about two-thirds of the way up the kiln used for loading, and a four-by-six foot opening at the bottom used for charging and discharging the charcoal and sometimes to fire the charge. Two to four rows of three-byfour inch vents at the bottom provided air circulation. Sometimes a chimney was left in the stacked wood, just like the pit, and used for the same purpose. Other times a channel might be built through the wood and filled with shavings and dry wood. The channel would be fired from the lower opening so that the fire was drawn to the upper opening. 22

Kilns typically ranged in size from twenty-five to thirty feet in diameter and twenty to twenty-five feet in height. They held from twenty-five to forty-five cords of wood. They could be built into the side of a bank to make loading from the top easier; otherwise, a charcoal burner would need a ladder or ramp to reach the upper charging door. An example of size ranges is found at the kilns of American Fork Canyon, where one kiln was twenty-six feet in diameter and twenty feet tall and held twenty-five cords of wood; another kiln was twenty-nine feet in diameter and twenty-eight feet tall and held forty-five cords. 23

The operations in American Fork Canyon also provide an example of the production costs of charcoal kilns. The high price of coke justified the use of charcoal there: in 1875, coke cost forty-five dollars per ton, while charcoal was eighteen cents a bushel (roughly twenty dollars a ton). A kiln holding thirty-five cords would produce between 1,000 and 1,200 bushels of charcoal. Pine cost $3.75 per cord and poplar cost three dollars per cord. It took six men to do all the work and nine to ten days to burn the charcoal. At the end of every operation, the kilns received a whitewash. 24

Though charcoal kilns were more permanent than pits, they did not last indefinitely. Erosion of a kiln usually began at the top. Today, some extant kilns lack only a top, while others retain only parts of their sides; the fairly permanent foundation is all that remains of a few. There are five areas where intact, or nearly intact, charcoal kilns can be found in Utah: Frisco (thirteen kilns), Leamington (one kiln), Iron City (one kiln), Silver Reef (one kiln), and Lake View (one kiln); sites in Wyoming and Colorado, closely associated with Utah mining, have (respectively) three and four intact kilns. There are also dozens of locations that were important to the charcoal industry that still retain kiln remnants, though usually just the foundation (see table two). What follows is a geographic tour of kiln sites throughout the state.

§

American Fork Canyon in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah County had two sets of charcoal kilns. Now the existing remnants are just crumbling foundations or rocky circles in the ground with the last few stones still present. American Fork District was organized in 1870; it comprised six square miles at the head of the canyon. The principal mine was the Miller Mining and Smelting Company, which built the Sultana Smelter on a flat near the mine. Forest City, eighteen miles from the town of American Fork, developed near the smelter and mine. 25

TABLE 2: FRISCO CHARCOAL KILN CONDITION ASSESSMENT *

In 1872 the American Fork Railroad was organized to connect Forest City to the Utah Southern Railroad. Due to steep grades, the railroad stopped about four miles short of Forest City. The town of Deer Creek developed at the terminus of the railroad at present-day Tibble Fork Reservoir. At the time the railroad was built, twenty-five stone, beehive-shaped charcoal kilns were built, which included fifteen at Forest City and ten at Deer Creek. 26 A tramway built on a trestle connected these kilns to the Sultana Smelter. 27 They ran constantly from 1872 to 1877, making charcoal for the Salt Lake Valley smelters. 28 One author described the kilns as conical in shape and gave their capacity as twenty-five cords of wood, with a diameter base of twenty-six feet and a height of twenty feet. 29 However, J. C. Cameron, who worked in Utah at the time, used the American Fork kilns as examples of the beehive design. 30

The Salt Lake Daily Tribune reported in November 1872 that Deer Creek location contained ten charcoal kilns constructed by the Miller Mining Company. The ovens ran at full capacity, requiring a minimum of twenty-five cords of wood each and the labor of forty men and fourteen teams daily. The Tribune described the kilns as beehive shaped and

Then, in 1878, the ore played out. The Miller mine soon closed, and the railroad tracks were taken up. The ten Deer Creek charcoal kilns were torn down to salvage lead in the bottoms. 32 Today, the site may be under or adjacent to the Tibble Fork Reservoir. The bases of the kilns at Forest City, meanwhile, are lined up at the side of North Fork Road at the intersection with Shaffer Fork Road.

Big and Little Cottonwood canyons in Salt Lake County are just north of American Fork Canyon. Though some of the earliest mining in the state happened in these canyons, charcoal burning there occurred in charcoal pits, and the cutting of wood for charcoal took place from the earliest settlement. 33 Truckee, California, and Piedmont, Wyoming, supplied most of the area’s charcoal, however. 34

Moreover, not much smelting occurred in Big and Little Cottonwood canyons. The railroad made mining profitable and provided a connection to outside smelters. 35 Several smelters operated in Little Cottonwood Canyon, but none lasted long. 36 Only one large smelter was ever built in Big Cottonwood Canyon and it quickly proved unsuccessful in turning a profit. 37 Finally, early settlers, who needed lumber for building and timbers for mining, denuded the canyons; few trees could have been left for charcoaling. Thus, an area where you would expect to find kilns has none.

We found a similarly surprising lack of kiln activity for Bingham Canyon (West Mountain District). This area, which is located on the east side of the Oquirrh Mountains in Salt Lake County, saw some of the earliest mining development in Utah. Yet we found no mention of kilns in that canyon. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, in 1872 the charcoal supply came from Truckee, California, and Piedmont, Wyoming— the same areas that supplied the Big and Little Cottonwood canyons. 38

In contrast, farther south in the Wasatch Mountains in Utah County, Spanish Fork Canyon had two sets of kilns. In 1881 the Provo businessman S. S. Jones was convinced to transport charcoal from Spanish Fork Canyon to the Horn Silver Mine’s Murray Smelter near Frisco. A new railroad was built through the canyon, and the charcoal produced closer to the mine was expected to be cheaper than that supplied via the Union Pacific Railroad. Jones selected Mill Fork as the location for the kilns as it was near the railroad, water, and pinyon pine. Construction of several beehive-shaped kilns started in September and by late October the kilns were ready to be fired. The first burn proved to be catastrophic because too much water was used to cool the coals and the resulting steam caused the kilns to burst. 39 The kilns were rebuilt and future burns proved successful.

Jones prospered and in 1886 he purchased the nine McCoy and McAllister (M&M) kilns located about four miles farther up the canyon, about two miles from Clear Creek (present-day Tucker). 40 He now owned fourteen kilns that produced forty carloads of charcoal monthly. 41 Charcoal provided much of the employment in Mill Fork. An 1887 business publication described bustling appearance of the operation:

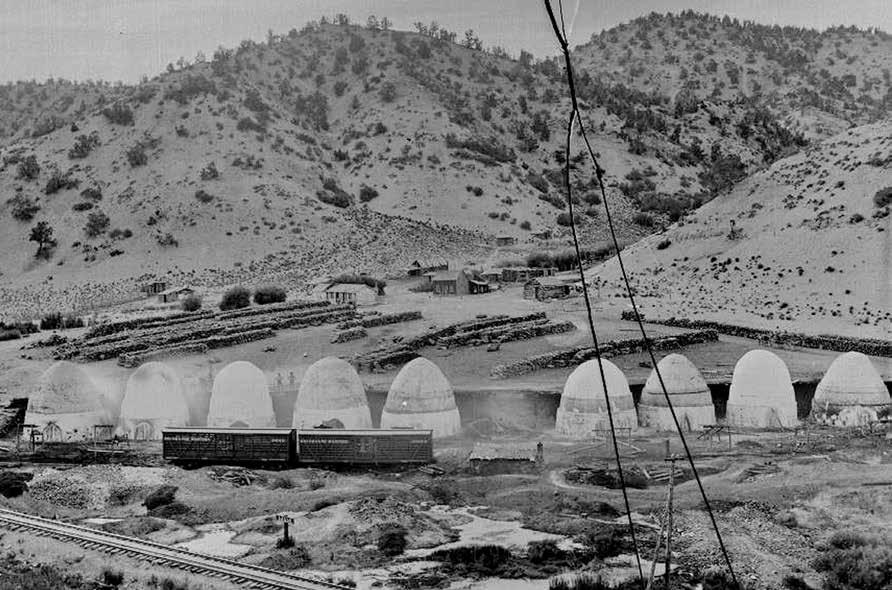

The McCoy and McAllister kilns that were once in Spanish Fork Canyon, ca. 1890.

USHS

The number of Mill Fork and M&M kilns fluctuated between twelve and fourteen as older ones burned out and some were replaced. They operated into the 1890s. 43 These kilns were on the north side of the then-existing railroad tracks. Neither set of kilns exists today due to extensive reworking of the railroad and highway beds. 44

The literature can be confusing on charcoal kilns; not all planned kiln construction took place. In late 1894, local newspapers discussed well-developed plans for an ironworks and thirty-five charcoal kilns to be built at or near Willard. That construction never took place because of a lack of investment capital. 45 Eastern Utah (Emery and Grand counties) had coke available by the time it was settled; limited charcoal burning (using pits) occurred there. 46

When the railroad reached Spring Glen, near the center of the state in Carbon County, the availability of pinyon pine attracted the town’s first industry—charcoal production. John Thompson Rowley, an excellent charcoal burner, established the Blue Cut Charcoal Company there in 1889. S. S. Jones had previously employed Rowley in the charcoal business. Rowley built his first six kilns just south of the Blue Cut sandstone bluff, about a mile south of Spring Glen. 47 His company shipped charcoal to gold and silver smelters in Nevada, where it could be used instead of coke. 48 The business was profitable and provided considerable employment in cutting and transporting wood and tending the kilns. 49 The next year, in 1890, Rowley built an additional six kilns on the Andrew Simmons’s homestead in Spring Glen. 50 By 1902, the Deseret Evening News noted that “the charcoal kilns of J. T. Rowley at Spring Glen are working full blast at this time, the product finding a ready market in Salt Lake City.” 51 The business prospered for about fifteen years, benefiting the community financially, until the price of silver dropped. 52

Tooele County was a major producer of gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc. Accordingly, several sets of kiln remnants are present. John Hammond built the first charcoal kiln in the county in about 1869, just north of Rush Lake around the time the Waterman Smelter was being constructed. 53 Two more were soon added. Though Hammond built the kilns, Archibald Shields, a brick maker, planned them. The Deseret News described the kilns as thirty feet tall, with “thimble-like” domes. 54 It took four to five days to burn the charcoal and one day to empty the kiln. The kilns were cleaned and repaired after each use, since the high temperature caused cracking. No evidence of the kilns remains at this location.

In about 1880 more kilns were erected about three miles east of Stockton at the foot of Soldier Canyon. These kilns, also known as the Waterman Coking Ovens, produced charcoal for the Chicago Smelter. Transportation costs played a major role in the location of charcoal kilns; the Waterman kilns were halfway between the timber source on Bald Mountain, to the east, and the Rush Valley Mine, three miles to the southeast. 55 They too were supervised by Shields; as producers of the kiln bricks, Shields and his brother had an active part in much of the county’s charcoal making. 56 A federal mining report confirms the presence of charcoal burning in the Tooele Mining District; it noted that in 1880, “In the neighborhood of Tooele City there are twelve stone beehive kilns constructed at intervals between 1874 and 1889. They are run irregularly by Mormon owners, who sell the charcoal produced to the Stockton smelters.” 57 There were easily twelve kilns operating then. To locate all of them today would be impossible. 58 However, the foundation walls of the four Waterman Coking Ovens still remain, though the bottom three to four feet of the kilns are buried in soil and rock deposited by flood waters.

Three charcoal kilns were built in the community of Pine Canyon (also called Lake View and Lincoln) northeast of the city of Tooele. These kilns operated from about 1870 to 1880. Only a single kiln, mostly intact, is still present today. The remaining Lake View kiln has been proposed for restoration and stabilization by the county historical society. In addition to these three ovens, there was another kiln about 0.9 miles southeast of them, near the mouth of Pine Canyon. It no longer exists. 59

Family tradition and documents both describe kilns elsewhere in Tooele County. While no evidence exists on the ground today, a family history states that the James David James family had several charcoal kilns in Settlement Canyon and provided charcoal to the many smelters in the area. 60 There were two sets of kilns in Settlement Canyon on the southeast side of Tooele city. The lower set (of unknown number) was located just downstream of the present day Settlement Canyon Reservoir, within a modern residential area. The upper set of two kilns was located approximately 4.5 miles away, where Kelsey Canyon joins Settlement Canyon. Nothing remains of either set. 61 A charcoal kiln was located in Tooele off 200 West Street, but nothing remains of it due to urban development. A mining history of the county notes that besides Soldier Canyon, “Other kilns were located in Vernon, Pine Canyon, Tooele City, and Settlement Canyon.” 62 The kiln mentioned at Vernon was likely a lime kiln.

The remains of four kilns can still be found in Soldier Canyon just east of Stockton.

Douglas H Page

Farther north, on the east side of the Oquirrh range, two more charcoal kilns were likely present in the Ophir Mining District. They do not exist today as the area has been developed. 63 Finally, in far western Tooele County near the Nevada line, a set of rock-based adobe charcoal kilns were located at Gold Hill. 64 Only two foundations and a small sidewall portion remain today.

About two-and-a-half miles northeast of Eureka is the ghost town of Homansville in Utah County. Near U.S. Highway 6, just south of the old railroad bed, are the remains of three charcoal kilns. Stephen Carr reported the existence of two charcoal kilns, approximately eight feet in diameter,but our field investigation revealed three foundations, each measuring twenty to twenty-one feet in diameter. 65 These were built in about 1871, and the charcoal likely went to the Wyoming Smelter. 66 The East Tintic Mountains had a charcoal kiln location in Broad Canyon in Utah County, near the Tooele County line (close to where those counties intersect with Juab County). 67 Efforts to locate the kiln revealed only a pit location, and any stone kiln might no longer exist, if it ever did.

Traveling south, two of four charcoal kilns remain along State Highway 132; they are about a mile east of Leamington on the northern border of Millard County. A historical marker at that site states that Nicholas Paul, Ole Jacobson, and Herman Lundahl built the ovens for George Morrison in 1882. 68 A variety of transportation methods were involved in the different stages of charcoal production for these kilns. Wood was cut in the nearby canyons to the east and hauled by horse or mule—at a rate of one quarter cord per mule—to the canyon mouth. With four mules and three trips per day, one man could transport three cords of wood in a day. The wood then moved by wagon or cart to the kilns. The Utah Southern Railroad Extension had reached the area in 1879, and Morrison built his kilns near the tracks to the facilitate shipping of charcoal to smelters in northern Utah. 69 Then in 1895, the Ibex Smelter was built two miles northwest of the kilns. For at least one year, the Morrison kilns supplied Ibex with charcoal; when the smelter shut down due to a lack of ore, the kilns presumably followed soon thereafter. 70

About fifteen miles west of the present town of Milford in Beaver County is perhaps the highest concentration of charcoal kilns in Utah and the Great Basin. Two prospectors accidentally discovered silver-bearing ore there in 1875 and Frisco was founded in 1876. Their strike became the Horn Silver Mine, one of the richest silver mines in the world, and Frisco became one of the wildest mining boom towns in Utah. 71 Then in 1885, the Horn had a major cave-in. Frisco started its decline soon afterward; it is now a ghost town. 72

Numerous charcoal pits and kilns, constructed of native stone, surrounded the mines and the community of Frisco. Charcoal from pits sold for a few cents less than kiln charcoal because of its lower quality. A 1913 government report described the Frisco location in some detail and noted that it contained thirty-six beehive-type charcoal kilns, managed in eight groups. According to the report, these kilns were near local wood supplies, ranging from six to eighteen miles from Frisco. 73

The site located north of Sawmill Canyon has the largest number of intact kilns in the state.

Douglas H. Page

Most other sources also describe thirty-six kilns at eight locations; however, our field investigation located evidence of forty-one stone kilns at eleven sites. Those eleven sites are spread over two mountain ranges—with nine sites in the San Francisco Mountains and two sites in the Wah Wah Mountains—and span twenty-five miles from the Beaver-Millard County line in the north to Lamerdorf Canyon in the south. Charcoal pits were also common in both mountain ranges and can be found as far south as Blawn Mountain. The number and concentration of the kilns, with no doubt, had profound short- and long-term effects on the nearby pinyon-juniper forest and the composition and structure of these forests as we see them today.

The five Frisco kilns at the old town site, built by the Frisco Mining and Smelting Company, are probably the best-known charcoal kilns in Utah. 74 The sets of kilns around Frisco vary in condition. The Sawmill North site is probably the best preserved of the eleven sets, with six of the seven kilns still largely intact. The Copper Gulch kiln had been partially cleaned with a fresh whitewash coating applied on the lower portion after its last use, but it was never used again. At the Barrel Spring site an arch doorway fell sometime between March 2012 and July 2013, leaving only one kiln with an intact doorway. For a time, the Three Kilns Spring site was used as a line shack by ranchers who installed wooden doors and a roof on one kiln. Table one lists the general location of each set, along with other kilns throughout the state; table two lists the eleven sets and gives a general assessment of each set.

Some of Utah’s iron mining history includes charcoal kilns located near Cedar City in Iron County. In Utah’s early history, Mormon leaders did not encourage mining for precious metals. However, resources like iron or coal had productive use and were another matter. The State of Deseret that Brigham Young attempted to establish in the Great Basin was to be self supporting. In 1849 he commissioned the Southern Exploring Company to locate resources in Utah’s southern region. They located “thousands of acres of Cedar, constituting an almost inexhaustible supply of fuel that makes excellent charcoal. In the center of these forests rises a hill of richest iron ore.” 75 That hill was Iron Mountain, near present-day Cedar City. Iron ore is still being mined from this location today.

In 1850 iron missionaries traveled south from Salt Lake City to develop the resource and within two years the Deseret Iron Company was organized. This was one of the first locations west of the Mississippi to produce pig iron. 76 The effort never fully succeeded, partially due to natural disasters and conflicts with local Native American groups. It ceased operation in 1858. 77 Ten years later the Union Iron Works was established on Little Pinto Creek south of Iron Mountain and about twenty-three miles southwest of Cedar City. Iron City grew up around the iron works. 78 Iron City had a smelting furnace, two conical charcoal kilns, a charcoal house, and the various buildings that make up a small town, including a post office. Within a few years production was well over a ton per day. A railroad was planned to connect Iron City to the northern mining districts, but it never materialized. While the venture had some short-term success, it closed in 1876. 79

Iron City is now known as Old Irontown and is a part of Frontier Homestead State Park Museum. It consists of a set of protected ruins connected by footpaths. Historical markers interpret the ruins, which include the furnace, portions of the foundry and its chimney, and a restored charcoal kiln, along with the foundation of a second adjacent charcoal kiln. The restored kiln has a distinctive look as the top portion is the exposed brick lining and the bottom portion still has its original exterior rock surface. Its historical marker explains that one kiln had to burn for twelve days in order to produce fifty bushels of charcoal, the amount required to process one ton of iron ore. 80

During our field investigation, we discovered a second charcoal production site just two miles northeast of the Iron City kilns in the Big Dry Wash. Pinyon-juniper clearing operations have twice disturbed this site. Though such activity would have destroyed and displaced any kiln remnants, the rock we observed there indicates a good likelihood that a kiln was connected with this site. 81

Just north of Cedar City another charcoal kiln once existed in Enoch at Johnson Fort, now the city park. The families of John Lee Jones and John Pittinger ran the kiln, which was part of a small family business venture, probably a blacksmith shop. 82 A small ring of stones in the park, approximately ten feet in diameter, is identified as a charcoal oven. This is next to the remains of the furnace operation. We found no evidence to either support or refute the assertion that these stones are the remains of the charcoal oven.

There are other possible charcoal kilns in southwestern Utah associated with the Apex Mine. One source claims that “Beehive shape charcoal kilns were built at Spring Hollow and Poor Hollow, at the foot of the Pine Valley Mountains, to produce charcoal for the smelter.” 83 Our field investigation located a charcoal pit site in Spring Hollow but no evidence of constructed kilns. The location of Poor Hollow is unknown. 84

Another kiln is located in the Silver Reef district, along Leeds Creek and just west of the present-day town of Leeds in Washington County. In 1866 a prospector noticed silver in the sandstone in an area about eighteen miles northeast of St. George. The common view at the time was that it was not geologically possible for silver to exist in sandstone. For over five years the prospector worked in the general area and eventually convinced himself and a few others of the truth of his discovery. Salt Lake City bankers became involved, and in the mid-1870s the Salt Lake Tribune published the location of the strike, which resulted in a mining boom. 85

Old Irontown in Iron County has a restored charcoal kiln, one that is a good example of a conical-shaped kiln.

Douglas H. Page

Miners from nearby Pioche, Nevada, soon arrived. 86 Many other participants in the Reef boom were workers displaced by the end of construction on the transcontinental railroad; accordingly, Silver Reef had a large Chinatown. 87 Though the town of Silver Reef had a mile-long Main Street, paved with smooth river rocks and boasting a boardwalk on both sides, it also had a reputation as one of the wildest towns in the West. 88 The peak of the boom lasted from 1878 to 1882. By 1884 most of the mines had closed. 89 Demand for smelter fuel quickly developed and local men financed a charcoal

kiln near Silver Reef. 90 Italian stone masons built the Leeds Creek kiln in about 1885 of sandstone blocks and mud mortar. The kiln’s Roman-style arch and the nearby Italian Wash support the idea of Italian labor in the construction. Pinyon pine and scrub oak, logged from the Pine Valley Mountains, filled the kiln. Teamsters then hauled the charcoal produced in Leeds Creek to the smelter in Silver Reef. 91

Though charcoal production occurred throughout much of Utah, some areas of the state were not conducive for the creation and use of charcoal kilns, largely because they did not have the desired tree species in sufficient quantities to justify the long-term investment in constructed kilns. For instance, the charcoal burning that took place in northern Utah occurred in pits, rather than kilns. Furthermore, much of the local ore was transported for processing in Tooele County, and the demand for charcoal was never high. 92

Several Wyoming kilns have a Utah connection: most of the wood processed at these Wyoming kilns came from Utah; ore smelters in Utah and Colorado then consumed the charcoal. 93 The Bear River has its headwaters in northeastern Utah and then flows north into Wyoming. The Upper Bear River supported substantial timber supplies, and the region was a source of lumber, railroad ties, mine timbers, and wood for charcoal production. Harvesting—principally of lodgepole pine, Englemann spruce, and aspen—started in about 1870.

For approximately a decade, the Upper Bear River had a colorful logging industry. A large sawmill existed on the Bear River at Evanston, Wyoming (near the Utah border). Most of the timber was floated down the river or transported by flume. Thirty-six miles of flume flowed from the mountains of Utah north to Hilliard, Wyoming, about fourteen miles southeast of Evanston and on the main line of Union Pacific Railroad. The main line was thirty miles long, about half in Utah and half in Wyoming. Both timber for railroad ties and cordwood for the kilns travelled on the flume. When the price of cordwood dropped, the flume was sold and eventually dismantled.

Twelve charcoal kilns were constructed in the immediate vicinity of Evanston, fed by fourfoot long cordwood floated down the Bear River. The charcoal industry flourished at Hilliard during the late nineteenth century. Hilliard had approximately twenty-nine kilns constructed from rock; these too were fed by the flume. 94 Today, the kiln site is privately owned and has been used for stock pens and equipment storage, leaving only remnants of the original kilns visible. Two kilns were constructed about five miles south of Hilliard on Sulphur Creek. Finally, five kilns were built at Piedmont, Wyoming, about twelve miles northeast of Hilliard. One author reported that wagons and sleds supplied the Piedmont kilns. 95 However, Piedmont is significantly distant from the timber sources; we suspect that the adjacent rail line might have supplied wood to these kilns from the flume in Hilliard. We found no record to support or debunk particular wood sources. Three of the Piedmont kilns have been restored, one has only foundation walls, and nothing but a mound of rubble remains of the fifth kiln.

Just across the Utah state line in Moffat County, Colorado, near Greystone, are the best surviving examples of charcoal kilns in Colorado. The capital, men, and teams that developed this mining region all came from Utah, and in its early days, this was considered a Utah enterprise. The Salt Lake Herald stated, “This mine is located just over the line in Colorado, but is owned by Utah men, and is considered as tributary to Vernal, the owners being mostly Vernal men.” 96 Four beehive style charcoal kilns were constructed in 1898. 97 These kilns have been protected and afford an excellent overview of intact charcoal kilns. 98 Charcoal produced from them went to the nearby Bromide Mining and Milling Company’s smelter facility.

§

It is not surprising that the charcoal industry has a modest place in Utah history. The industry never had much glory. Perhaps that is why so little of it is preserved. With the exception of the collier who had the skill to actually turn wood into charcoal, the charcoal burners were often disparaged. They worked in the low-skilled labor market and would earn less than half the wages of a common laborer in the mines. They lived in crude huts or dugouts, with none of the modern conveniences of the day. The charcoal-burners were “dregs of the Western labor barrel,” only welcomed in town when they had their ten dollars of weekly wages to spend. 99

Though the charcoal industry has only a small place in state history, it had a huge impact on Utah’s forests, altering and reshaping them. As one observer put it, charcoal production swept “over the West like a pestilence, leaving behind tens of thousands of acres stripped of timber.” 100 The use of charcoal by the smelters had consequences beyond the fuel supply and charcoal prices. Mining meant that demand was heavily concentrated in certain areas of the state, and most of Utah is not heavily timbered. Forest devastation was reported in some areas, and concern developed for the long-term wood supply for mining, commercial, and private uses. One 1873 report noted that:

For Native Americans, pine nut groves that had supported them through long winters over untold centuries were destroyed to supply wood to the charcoal kilns. Often, loggers paid little attention to the legal requirements of harvesting on the public lands. The industry was scarred by bloodshed, discrimination, and corruption. It was an exploitive industry, with aspects that some might not wish to remember, but it played a major role in developing the state, and its contribution is known by few.

Charcoal production was integral to the mining history of Utah. The state would have certainly developed differently without it and the extant remnants of Utah’s charcoal industry stand as testament to its importance. The remaining structure of the industry deserves protection and interpretation. Many of these remnants are the most visible evidence that mining activity existed in an area. Time is taking its toll on these relics and, perhaps, this article can spur interest in protecting a valuable part of Utah’s history. We also described charcoal production areas that no longer contain significant tangible evidence that the industry existed. In a few cases, that evidence is in danger of vanishing. Unless more active management and preservation efforts are exerted, there will be fewer and fewer ghosts to show the industry existed.

— DOUGLAS H. PAGE JR. is a retired forester who had a thirty-five-year career with three state and two federal agencies in six states, with most of his career spent in Utah. He lives in Cedar City. SARAH E. PAGE is a professional archaeologist for HDR, Inc. in Salt Lake City. THOMAS J. STRAKA is a forestry professor in the School of Agricultural, Forest, and Environmental Sciences at Clemson University in South Carolina. NATHAN D. THOMAS is the deputy preservation officer and state archaeologist for the Bureau of Land Management, Utah State Office in Salt Lake City.

—

WEB SUPPLEMENT

See history.utah.gov/uhqextras for an image gallery and for historical articles about kilns throughout the state.

1 Nell Murbarger, “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry,” Desert Magazine 19 (June 1956): 4.

2 Arlie W. Toole, Paul H. Lane, Carl Arbogast Jr., Walton R. Smith, Ralph Peter, Edward G. Locke, Edward Beglinger, and E. C. O. Erickson, Charcoal Production, Marketing, and Use, Report No. 2213 (Madison, WI: USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory, 1961).

3 Charles E. Williams, “Environmental Impact,” in Industrial Revolution in America: Iron and Steel, ed. Kevin Hillstrom and Laurie C. Hillstrom (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 163–72.

4 Robert B. Gordon, American Iron: 1607–1900 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 90–100.

5 Murbarger, “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry,” 4–9.

6 Thomas J. Straka, Robert H. Wynn, and Charles E. Burkhardt, “Charcoal Kilns of Eureka and White Pine Counties,” Central Nevada’s Glorious Past 28 (2009): 9–14. Massacre may be too strong a word, but the Eureka Historical Society used the word on a marker they placed on the mass grave in 1983. The grave is in one of the cemeteries on the hillside behind the County Courthouse.

7 Murbarger, “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry,” 4.

8 Brigham D. Madsen, “General Patrick Edward Connor: Father of Utah Mining,” in From the Ground Up: The History of Mining in Utah, ed. Colleen Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006), 58–80.

9 James A. Young and Jerry D. Budy, “Historical Use of Nevada’s Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands,” Journal of Forest History 23 (July 1979): 112–21.

10 Rossiter W. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1873), 300–301.

11 Ibid., 385, 442.

12 Gustaf Svedelius, Hand-book for Charcoal Burners (New York: John Wiley and Son, 1875). The soil covering limited oxygen to the fire.

13 Thomas J. Straka and Robert H. Wynn, “Pit Production of Charcoal for Nevada’s Early Smelters,” Central Nevada’s Glorious Past 29 (2010): 12–16.

14 Jackson Kemper III, American Charcoal Making in the Era of the Cold-blast Furnace, Popular Study Series History No. 14 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1941).

15 Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining, 385.

16 Martha Sonntag Bradley-Evans, “San Francisco Mining District,” in From the Ground Up, 370.

17 Young and Budy, “Historical Use,” 117.

18 T. Egleston, “The Manufacture of Charcoal in Kilns,” Journal of the United States Association of Charcoal Iron Workers 1 (November 1880): 56–64.

19 John Birkinbine, “Our Fuel,” Journal of the United States Association of Charcoal Iron Workers,” 2(April 1881): 66- 79.

20 Philip F. Notarianni, “The Frisco Charcoal Kilns,” Utah Historical Quarterly 50 (Winter 1982): 42. J. C. Cameron moved to Utah and took credit for the design of the beehive charcoal kiln in the Utah Mining Gazette, July 25, 1874.

21 D. Robert Carter, “American Fork Canyon: Utah’s Yosemite,” Provo (UT) Daily Herald, July 31, 2005; Heather R. Puckett, “A Cultural Landscape Study and History of the San Francisco Mining District and Frisco, Southwest Utah, United States” (PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 2013), 5–69. Firebricks used to construct the Frisco charcoal kilns were pressed with the marks “M & E / UTAH.”

22 James A. O’Neill, “Central Nevada’s Charcoal Industry,” Central Nevada’s Glorious Past 9 (May 1986): 12–15.

23 T. Egleston, “The Manufacture of Charcoal in Kilns,” Journal of the United States Association of Charcoal Iron Workers 2 (January 1881): 55–64.

24 T. Egleston, “Manufacture of Charcoal,” 1881, 62; Birkinbine, “Our Fuel,” 74–75. Birkinbine explained that the interior of the kiln was whitewashed. Burning caused the kiln to expand, and cooling caused it to contract. This created small cracks and openings, allowing air to leak into the kiln. This could cause the entire contents of the kiln to burn down to ash.

25 F. C. Calkins, B. S. Butler, and V. C. Heikes, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Cottonwood-American Fork Area, Utah, USDI Geological Survey Professional Paper 201 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1943), 140.

26 B. S. Butler and G. F. Loughlin, A Reconnaissance of the Cottonwood–American Fork Mining Region, Utah, United States Geological Survey Bulletin 620-I (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916), 165–226; Stephen L. Carr, The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (Salt Lake City: Western Epics 1987), 51.

27 Richard N. Holzapfel, A History of Utah County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Utah County Commission, 1999), 136.

28 B. S. Butler, G. F. Loughlin, and V. C. Heikes, The Ore Deposits of Utah, USDI Geological Survey Professional Paper 111 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920), 258.

29 Egleston, “Manufacture of Charcoal,” 1881, 57–58.

30 J. C. Cameron Jr., “The Smelting Ores of Utah and their Economic Metallurgy,” Utah Mining Gazette, July 25, 1874, 381.

31 “American Fork, Silver Lake City,” Salt Lake Daily Tribune, November 21, 1872.

32 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 51.

33 Calkins, Butler, and Heikes, Geology and Ore Deposits, 72.

34 Ibid., 74.

35 Anthony W. Bowman, “From Silver to Skis: A History of Alta, Utah, and Little Cottonwood Canyon, 1847–1966” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1967), 21–23.

36 Ibid., 34.

37 Laurence P. James, Geology, Ore Deposits, and History of the Big Cottonwood Mining District, Salt Lake County, Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah Geological and Mineral Survey, 1979), 37.

38 Salt Lake City Tribune, November 22, 1872.

39 Provo (UT) Daily Enquirer, October 29, 1881.

40 Helen Z. Papanikolas, “Utah’s Coal Lands: A Vital Example of How America Became a Great Nation,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (Spring 1975):104–124. Papanikolas’s article contains a photograph of the M&M charcoal kilns (p. 120). There were nine kilns north of the rail line about a mile from Clear Creek. Close analysis of the photograph shows the space between the fifth and sixth kilns from the left contains the foundation and rubble from a tenth kiln. Thus, the M&M location had a least ten kilns at one time.

41 Provo (UT) Daily Enquirer, May 13, 1890. According to the Daily Enquirer “S. S. Jones has five charcoal kilns running at full blast at Mill Fork, and seven at the M. M. kilns. Two more will soon be erected, making a total of 14 kilns owned by Mr. Jones.” The Mill Fork Cemetery is the best landmark remaining, and a short history posted there states that “There were three charcoal kilns located along the highway just west of this cemetery. Men with teams and wagons cut Piñon Pine to burn in these kilns. One can walk for miles on the north side of the highway from Sheep Creek to Tie Fork and count thousands of Piñon Pine stumps left standing.” Which is it? Did Mill Fork have five kilns or three kilns? Most likely both sources are correct. Note that the first kilns burst, while others burned out and were replaced. The number of kilns at both sites fluctuated over time.

42 Utah Industrialist, June 15, 1887.

43 D. Robert Carter, “Mill Fork: Sired by Steam, Fostered by Fire,” Provo (UT) Daily Herald, November 20, 2005.

44 While these kilns no longer exist, their locations were recorded on early United States Department of Interior General Land Office cadastral surveys. The Mill Fork kilns are shown on an 1885 map of Township 10 South, Range 5 East, Section 12, by Steward M. Pancake, and the M & M kilns are shown on an 1883 map of Township 10 South, Range 5 East, Section 16, by Augustus D. Ferron.

45 Ogden Standard, November 12, 1894; Salt Lake Herald, October 7, 1894.

46 Edward A. Geary, personal communication, August 8, 2013.

47 “Spring Glen Photographs,” Western Mining and Railroad Museum, accessed October 1, 2013, wmrrm. com/springglen.html. This website contains photographs of the six charcoal kilns just south of Blue Cut and a photograph of the Dupin Mercantile in Spring Glen. Some of the bricks from the Blue Cut kilns were used in construction of the mercantile.

48 Nancy J. Taniguchi, Castle Valley, America: Hard Land, Hard-Won Home (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2004), 67.

49 Nancy J. Taniguchi, “Common Ground: The Coalescence of Spring Glen, 1878–1920” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1977).

50 Teachers, Pupils, and Patrons of the Carbon County School District, “Spring Glen,” A Brief History of Carbon County, accessed October 1, 2013, http://www.carbonutgenweb.com/1930b.html.

51 “Carbon County Affairs,” Deseret Evening News, January 23, 1902.

52 “History of Spring Glen,” Price (UT) News-Advocate, May 26, 1921.

53 Gilberta Gillespie, “Charcoal Kilns of Pioneer Days Still Stand in Tooele County,” Deseret News, May 30, 1934. An 1886 United States Department of Interior General Land Office cadastral survey of Township 4 South, Range 5 West, Section 23, by Edward W. Koeber shows a kiln west of Stockton.

54 Gillespie, “Charcoal Kilns.”

55 Becky Bartholomew, “Charcoal Kilns and Early Smelting in Utah,” Utah History Blazer, May 1996, 18–19.

56 Ouida Blanthorn, A History of Tooele County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Tooele County Commission, 1998), 123, 361–62.

57 S. F. Emmons and G. F. Becker, Statistics and Technology of the Precious Metals (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885), 455.

58 Ouida Blanthorn, personal communication, August 9, 2013.

59 Alice and Ron Dale, personal communication, August 21, 2013.

60 Lewis Larsen, “Margaret Alice James Larsen,” Find a Grave, accessed May 11, 2014, http://www.findagrave. com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=53336603.

61 Ibid.

62 Claude T. Atkin, T. Allan Comp, S. E. Craig, Larry Deppe, Frank C. Dunlavy, Bill Kelsey, Chris Weyland, and Orrin P. Miller, Mining, Smelting, and Railroading in Tooele County (Tooele: Tooele Historical Society, 1986), 36.

63 Alice and Ronald Dale, personal communication, August 10, 2013.

64 Murbarger, “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry,” 4–9. The article contains a photograph of a rock-based adobe charcoal kiln taken about 1891 at Gold Hill. Adobe charcoal kilns are rare; another set, the Cottonwood Kilns, exists in eastern California near Owens Lake. Thomas J. Straka and Robert H. Wynn, “Western Nevada and Eastern California Charcoal Kilns,” Central Nevada’s Glorious Past 29 (2010): 7–11.

65 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 95.

66 Phillip F. Notarianni, “Historic Resources of the Tintic Mining District,” Nomination Form for National Register of Historic Places, 1977, accessed September 29, 2014, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/ Text/64000875.pdf.

67 An 1890 United States Department of Interior General Land Office cadastral survey of Township 9 South, Range 3 West, Section 3, by Robert Gorlinski shows an “old charcoal kiln” in or near Broad Canyon.

68 “Morrison Charcoal Ovens 1882,” Historical Marker Database, accessed May 11, 2014, http://www.hmdb.org/ marker.asp?marker=34859.

69 Stella H. Say and Sabrina C. Ekins, Milestones of Millard: 100 Years of History of Millard County, 1851– 1951 (Springville, UT: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers of Millard County and Art City Publishing, 1951), 496; Edward Leo Lyman and Linda King Newell, A History of Millard County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Millard County Commission, 1999), 163.

70 “Morrison Charcoal Ovens 1882.”

71 Martha Sonntag Bradley, A History of Beaver County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Beaver County Commission, 1999), 118; Frank Robertson, quoted in the Deseret News, September 8, 1969, cited in Bradley, History of Beaver County, 119. Robertson, together with Beth Kay Harris, authored Boom Towns of the Great Basin (Denver: Sage Books, 1962).

72 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 109–11.

73 B. S. Butler, Geology and Ore Deposits of the San Francisco and Adjacent Districts, Utah, United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 80 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913). Butler’s report (p. 114) contains the following description of the kilns: They “are made of granite float found in the neighborhood and a lime mortar. They are of various sizes, from 16 to 26 feet in diameter. It is the rule in this section to make the height of the kiln equal to the diameter. The thickness varies from 18 to 30 inches at the base and from 12 to 18 inches at the summit. There are two openings, closed by sheet-iron doors, one at the ground level, 4 by 6 feet, and the other in the side two-thirds of the distance to the apex, three by four feet. There are also three rows of vent holes, three by four inches, near the ground. The rows are about 18 inches apart, having vent holes three feet apart in each row.”

74 Notarianni, Frisco Charcoal Kilns, 40–46.

75 Gustive O. Larson, “Bulwark of The Kingdom: Utah’s Iron and Steel Industry,” Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (July 1963): 248.

76 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 149–50.

77 Janet B. Seegmiller, A History of Iron County: Community Above Self (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Iron County Commission, 1998), 320–27.

78 Kerry W. Bate, “Iron City, Mormon Mining Town,” Utah Historical Quarterly 50 (Winter 1982): 47–58.

79 Nell Murbarger, Ghosts of the Glory Trail (Las Vegas: Nevada Publications, 1956), 77–80.

80 Iron City charcoal kiln historical marker, Frontier Homestead State Park Museum, Cedar City, Utah.

81 Marian Jacklin, personal communication, August 21, 2013.

82 Ryan Paul, personal communication, August 15, 2013; ElRoy Smith Jones, ed., John Pidding Jones, His Ancestors and Descendants (Salt Lake City: American Press, 1972), 10.

83 George A. Thompson, Some Dreams Never Die: Utah’s Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 1999), 32.

84 Investigations into Spring Hollow and Poor Hollow included field surveys in Spring Hollow and consultations with Marian Jacklin, Dixie National Forest archaeologist; Geralyn McEwen, BLM archaeological technician, St. George; Glen Rogers, Shivwits Paiute Tribe; and Dick Kohler, president of the Washington County Historical Society.

85 Douglas D. Alder and Karl F. Brooks, A History of Washington County: From Isolation to Destination (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Washington County Commission, 1996), 112–17.

86 Leonard J. Arrington, “Abundance from the Earth: The Beginnings of Commercial Mining in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1963): 214–16.

87 Murbarger, Ghosts of the Glory Trail, 162–67. 88 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 138–42.

89 Gary Topping, “Another Look at Silver Reef,” Utah Historical Quarterly 79 (Fall 2011): 310–16.

90 Marietta M. Mariger, Saga of Three Towns: Harrisburg, Leeds, Silver Reef (Panguitch, UT: Garfield County News, 1951), 95–96.

91 “Leeds Creek Kiln,” Washington County Historical Society, accessed May 11, 2014, http://wchsutah.org/ miscellaneous/leeds-creek-kiln.php. The kiln’s historical marker, which mistakenly describes this conical oven as “beehive-shaped,” notes that it “measures 20 feet in diameter at its base and stands 25 feet high.” It has a “Roman arch entryway [that] was sealed with a metal door and the upper entry on the opposite side was used to fill the kiln with wood.”

92 Ronald Cefalo and Kaia Landon, personal communication, August 13, 2013.

93 L. J. Colton, “Early Day Timber Cutting Along the Upper Bear River,” Utah Historical Quarterly 35 (Summer 1967): 202–208.

94 Different sources report different numbers of kilns at Hilliard. Colton, “Early Day Timber Cutting,” 207, reported that thirty-two kilns were located there. However, Elizabeth A, Stone, Uinta County: Its Place in History (Laramie, WY: Laramie Printing Company, 1924), 178–81, and Margaret M. Lester, From Rags to Riches: A History of Hilliard and Bear River, 1890– 1990 (Evanston, WY: First Impressions, 1992), 7, both reported that thirty-six kilns were located there. The Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1878, reported twenty-nine kilns were operating there.

95 Carr, Utah Ghost Towns, 149–50.

96 Salt Lake Herald, December 13, 1897.

97 Salt Lake Herald, October 4, 1898.

98 S. V. Beckett, “Bromide Charcoal Kilns,” Nomination Form for National Register of Historic Places, 2000, accessed September 29, 2014, http://pdfhost.focus.nps. gov/docs/NRHP/Text/00000740.pdf.

99 Murbarger, “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry,” 4–9.

100 Ibid.

101 Rossiter W. Raymond, Silver and Gold: An Account of the Mining and Metallurgical Industry of the United States, with Reference Chiefly to the Precious Metals (New York: J. B. Ford, 1873), 304.

* For tables please view this article on a desktop.