15 minute read

Public Grazing Lands and the Progressive Conservation Movement: Reassessing the Gospel of Efficiency

Public Grazing Lands and the Progressive Conservation Movement: Reassessing the Gospel of Efficiency

BY MATTHEW A. PEARCE

If historian Samuel P. Hays defined Progressive conservation as the “rational planning” and “efficient development and use of all natural resources,” in his 1959 book Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency, then the lack of a comprehensive range management program on the western public domain throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries stands out as one of its greatest failures. 1 This failure is stunning when compared to the achievements of the period in regards to water development under the reclamation movement and management of the nation’s forests, national parks, and national monuments. Such achievements had profound consequences for subsequent historiography, which became compartmentalized according to specific bureaucracies (the Forest Service, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the National Park Service, for example) or to particular natural resources such as trees, water, or scenery. Nowhere are these political and historiographical divisions clearer than on the western range. Today, most low-elevation arid rangelands in the Intermountain West are administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), while the region’s lush mountain meadows are managed by the Forest Service. Livestock graze both landscapes, and many ranchers utilize both to ensure the economic success and sustainability of their operations. Yet public lands historians have traditionally treated BLM and Forest Service rangelands, as well as the animals and people who use them, as independent of each other. 2

National forest and BLM rangelands are unique landscapes, but their use by livestock during different seasons (a process known as transhumance) and their immense scale (approximately 316 million acres in the Intermountain West) requires historians to look at both. 3 To that end, this essay examines the work of botanist Frederick V. Coville, who was among a growing group of federal officials during the Progressive Era who investigated the issue of livestock grazing on all public lands in the Intermountain West. Coville graduated from Cornell University in 1887 and became chief botanist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) by 1893. At this time, much of the region’s rangelands were in the public domain, or open for settlement and distributed by the General Land Office (GLO), located in the Department of the Interior. Meanwhile, Coville’s Division of Botany and, later, the Division of Agrostology (created in 1895), situated within the USDA, were tasked with investigating forage conditions and cataloging plants throughout the Intermountain West. Such work placed Coville and other division officials in the unique position of conducting scientific work on western landscapes regardless of federal jurisdiction. 4

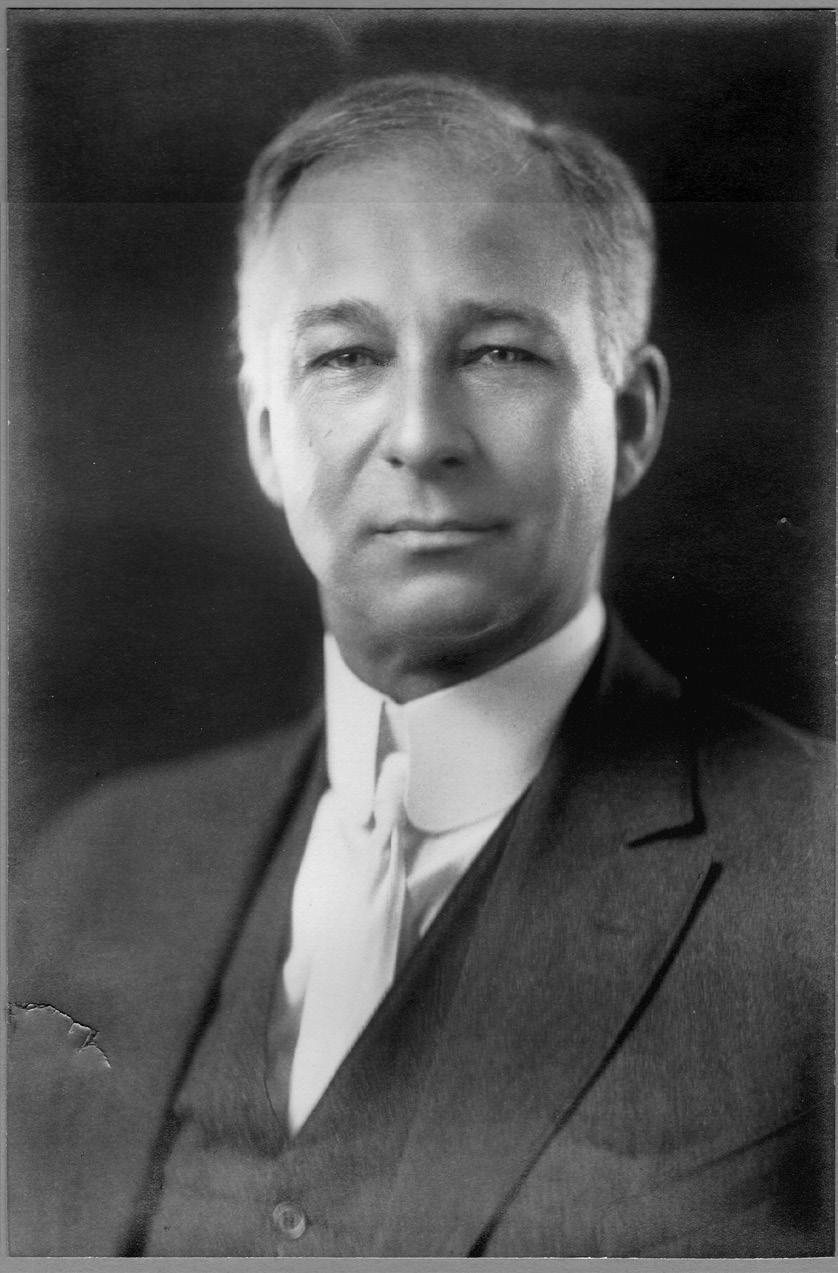

Frederick Vernon Coville (1867–1937), chief botanist of the United States Department of Agriculture whose work in the Intermountain West informed the grazing regulations on the public domain that would be codified with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. He is also prominent as a founder of the United States National Arboretum, in 1927. Wikimedia Commons.

By the summer of 1897, Coville was investigating rangelands within the Cascade Range Forest Reserve (now Willamette National Forest) in Oregon, then under the supervision of the Department of the Interior. There, he observed a landscape used by over 188,000 sheep despite previous attempts by the Interior department to prohibit sheep grazing on the reserve. 5 After a series of protests and lawsuits from sheep operators in the region, the GLO finally allowed sheep grazing within the reserve in June 1897. Yet Coville observed that sheep entered the reserve prior to when the GLO’s announcement went into effect, rendering any attempt to issue grazing permits to specific operators “ineffective” for the 1897 grazing season. 6

Throughout the summer, Coville interviewed sheep operators and catalogued plants believed to be most useful to livestock. Here was the scientific, rational process at work, and Coville’s report was among the most important early studies on livestock grazing within the forest reserves. In Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency, Samuel Hays even referred to it as “the first scientific range investigation in the United States.” 7 In it, Coville concluded that the outright removal of sheep from western forest reserves was impractical, if not impossible, because these animals and their handlers were already on the land. The only solution, one reinforced by Forestry Division chief Bernard Fernow, was the creation of “proper [grazing] restrictions and regulations” that balanced livestock use in each reserve with forest growth and watershed protection. 8

Despite the lack of regulations up to this point, forage conditions could have been worse on the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. In fact, Coville observed that overgrazing had only just “begun” because of “trampling” in sheep bedding grounds and along travel routes. 9 Yet he and other botanists described a much different situation on low-elevation rangelands within the public domain that lay outside and adjacent to the Cascade and other forest reserves. In some places, Coville described gullies that were twenty feet deep and “long since denuded of grass by overgrazing.” 10 Similarly, during a survey of range conditions in the northern Great Basin in 1901, botanist David Griffiths noted areas where “there was practically no more feed than on the floor of a corral.” 11 Such observations went on to emphasize that deteriorating range conditions on the public domain contributed to instability (or what Coville called “restlessness”) among livestock operators as they moved constantly in search of better forage, wearing out their animals and exhausting rangeland resources in the process. 12

This phenomenon was the epitome of what Progressive conservation experts called the public domain “range problem.” 13 According to Coville and other observers, the challenge stemmed not from the fact that the West comprised of marginal or submarginal land, but rather from the government’s inability to administer livestock grazing on the public domain in an equitable manner among ranchers who already lived in the region. Although historians such as E. Louise Peffer commonly referred to public domain rangelands as the “remnants” of America’s public lands system due to their aridity, livestock utilized these landscapes nonetheless. 14 As late as 1931, over one million sheep grazed on the western public domain during the winter, and another 628,000 did so during the spring. 15 Such statistics indicate that these lands continued to offer what the esteemed John Wesley Powell once called “nutritious but scanty grass.” 16

In 1903, a Public Lands Commission comprised of W. A. Richards of the General Land Office, Frederick H. Newell of the Reclamation Service, and Gifford Pinchot of the Bureau of Forestry (later Forest Service) took up the challenge of range regulation. The commission met with stockgrowers throughout the West and, as Samuel Hays wrote, “stirred up a hornets’ nest” over the proposition of leasing public domain rangelands for grazing. 17 Hays described large cattle operations as speaking in favor of the proposition while smaller ranchers opposed it. Western newspapers criticized the leasing proposal as monopolistic and as a threat to future homesteading. Subsequent leasing bills in Congress were subject to similar criticisms. Indeed, by 1926, sixty-five leasing bills had reached the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys and none of them were reported on favorably. 18

Although Hays and subsequent historians commonly argued that such leasing proposals foundered due to politics, such focus on the political failures of range regulation is unsatisfactory. After all, the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which created the framework for a federal range management program on the public domain, emerged from similar political conflicts. If the history of public lands is one of “a tug of war” between the impulses of private development and public ownership, as E. Louise Peffer argued, then any political resolution to grazing disputes had to resolve the tensions between both extremes. As a USDA official who investigated public domain grazing lands, Coville was well suited to navigate such disputes and propose solutions. 19

With Coville’s assistance, the Public Lands Commission recommended the creation of “certain grazing districts or reserves” on the public domain, within which ranchers could receive access on a permit basis that ranged from five to ten years with the possibility of renewal. 20 Preference in using a grazing district would go to established livestock raising operations that could prove their use of the range prior to its organization as a grazing district and its integral role in their annual operations.

In his written contribution to the commission’s report, Coville went on to argue that the individual tasked with implementing the grazing district program “should have a thorough knowledge of the live-stock industry of the western United States, preferably such a knowledge as is derived from actual former experience as a stock raiser.” 21 A potential administrator had to have connections with the livestock associations, be able to sell the program to the industry, and recruit individuals to assist him. There was more to this idea than simply gaining the livestock industry’s seal of approval, however, since administrative and financial matters also had to be considered. As Coville suggested, this approach ensured that the number of district personnel remained small and focused primarily on managing the public domain for the benefit of local ranchers and homesteaders. Coville provided the details for what the commission called a “moderate fee” by suggesting one of “not less than 5 cents per head per season for [sheep and goats] or 25 cents for [cattle and horses]” on the federal grazing districts. 22 He went on to stress that these fees should not raise federal revenue. After a onetime congressional appropriation, Coville argued that the money received from permittees could cover “the cost of administration of the system, including the cost of classification and appraisal.” 23 Any surplus, Coville continued, should be spent on district improvements. In sum, Coville proposed that ranchers should see a direct return of their investment rather than have their fees support a large grazing bureaucracy or fill federal coffers.

Coville’s recommendations regarding grazing fees and grazing districts, combined with his report on the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, represented a compromise between the wholesale absence of federal grazing regulations and the outright removal of livestock from the western range. As he wrote in his report on the Cascade reserve, “[A] system can be adopted which, honestly and intelligently carried out, will stop the real evils of the present system and at the same time maintain the interests of all the communities concerned.” 24 This reference to maintaining “the interests of all the communities concerned” was quintessentially Progressive and anticipated Gifford Pinchot’s famous notions of the “greatest good” philosophy. 25 Yet implementing this program required working with the same ranchers and livestock associations credited with blocking grazing reform. Such industry influence stemmed from the strength of the livestock associations within western politics during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as well as from the economic prestige and political ambitions of the wealthiest ranchers. 26 Thus, despite Coville’s interest in the public good, his reports ultimately indicate that the overall success for federal range reform on public grazing lands depended upon a relatively small number of western inhabitants who used most of the landscape, along with the political support of their respective associations and representatives in Congress.

Landscape scene in Nevada, 2012. Signs and advertisements like this are common in the American West. Photo by Matthew A. Pearce.

Frederick Coville’s work in the Cascade reserve helped lay the foundation for modern range science, influenced the livestock grazing program on western national forests, and even anticipated regulations enacted by the Taylor Grazing Act. Yet historians have overlooked his willingness to engage in ordinary range politics. For instance, Coville emphasized the importance of working with the local woolgrowers’ associations to implement a grazing program for the Cascade reserve. A committee comprised of representatives from these groups, he argued, “would be thoroughly competent to divide the range, and could do it both more equitably and with less objection from dissatisfied owners than could any officer or offices of the Government.” 27 Coville might have been an expert hired by the federal government, but this statement does not reflect a desire to create a grazing administration run by experts. Although Coville could not predict the future, his statement about an ideal range administrator with “a thorough knowledge of the livestock industry” effectively described future federal range administrators, most notably Farrington Carpenter, the first director of the Division of Grazing (1934–1938), and Marion Clawson, the first director of the Bureau of Land Management (1948–1953).

Signs that advertise “Your Public Lands” are everywhere in the American West. Coville’s experiences reveal the scientific expertise and personal compromises involved with the creation, use, and administration of these lands. For every Cliven or Ammon Bundy who makes the national news for their actions or statements against public lands, there are hundreds of arguments, negotiations, and concessions made between public land administrators and users that do not make national headlines. Thus, if federal conservation implied “social control,” as Benjamin Hibbard once argued, historians and the general public should pay closer attention to how this control took shape and remains subject to constant renegotiation within local communities. 28 Federal rangelands administered by the BLM and the Forest Service provide one area to examine these relationships, as they are among the places where science, planning, and politics overlap on western public lands.

Notes

1 Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement (1959; repr., New York: Atheneum, 1974), 2. By “western public domain,” this essay refers to the millions of acres of western land that were available for private ownership under land laws such as the Homestead Act during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

2 While the historiography of other conservation fields such as forestry, parks, and water remains vast and we have seen the emergence of new works in energy, gender, and urban studies, the literature on range management remains small. Notable works on Forest Service range management include Thomas G. Alexander, “From Rule of Thumb to Scientific Range Management: The Case of the Intermountain Region of the Forest Service,” Western Historical Quarterly 18 (October 1987): 409–28; and William D. Rowley, U.S. Forest Service Grazing and Rangelands: A History (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1985). For the public domain and Bureau of Land Management, see Wesley Calef, Private Grazing and Public Lands (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Phillip O. Foss, Politics and Grass (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1960); and James R. Skillen, The Nation’s Largest Landlord: The Bureau of Land Management in the American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009). Only a small number of authors have attempted to examine forest rangelands and the public domain rangelands in relation to each other. Bernard DeVoto, “The West against Itself,” in The Easy Chair (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955), 231–55, was among the first to do so. See also Karen R. Merrill, Public Lands and Political Meaning: Ranchers, the Government, and the Property between Them (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); and William Voigt Jr., Public Grazing Lands: Use and Misuse by Industry and Government (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1976).

3 Cynthia Nickerson et al., Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2007 (Washington, DC: USDA Economic Research Service Economic Information Bulletin No. 89, 2011), 10, 22–24. The 316 million acres figure concerns the total estimated land area of all national forests and BLM lands in the western United States as of 2015. See Carol Hardy Vincent et al., Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2017), 21.

4 Representative examples include H. L. Bentley, Cattle Ranges of the Southwest: A History of the Exhaustion of the Pasturage and Suggestions for Its Restoration (Washington, DC: USDA Farmers’ Bulletin No. 72, 1898); David Griffiths, Forage Conditions on the Northern Border of the Great Basin (Washington, DC: USDA Bureau of Plant Industry Bulletin No. 15, 1902); Cornelius L. Shear, Field Work of the Division of Agrostology: A Review and Summary of the Work Done since the Organization of the Division, July 1, 1895 (Washington, DC: USDA Division of Agrostology Bulletin No. 25, 1901); and George Vasey, Report of Investigation of Grasses of Arid Districts of Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado (Washington, DC: USDA, Division of Botany Bulletin No. 1, 1886). In 1901, the Division of Botany and the Division of Agrostology merged to create the Bureau of Plant Industry.

5 Frederick V. Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon (Washington, DC: USDA, Division of Forestry Bulletin No. 15, 1898), 16.

6 Coville, 11.

7 Hays, Gospel of Efficiency, 55.

8 Bernard E. Fernow to James Wilson, February 8, 1898, in Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing, 3. See also Rowley, U.S. Forest Service, 33–34.

9 Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing, 26–27.

10 Coville, 27.

11 Griffiths, Forage Conditions, 28.

12 Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing, 27; Griffiths, Forage Conditions, 22, 30.

13 W. J. Spillman, “Preface,” in Range Investigations in Arizona, David Griffiths (Washington, DC: USDA Bureau of Plant Industry Bulletin No. 67, 1904), 5.

14 E. Louise Peffer, The Closing of the Public Domain: Disposal and Reservation Policies, 1900–1950 (1951; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1972), 169.

15 William Peterson, “Land Utilization in the Western Range Country,” in Proceedings of the National Conference on Land Utilization (Chicago: November 19–21, 1931), 46.

16 John Wesley Powell, Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah (1878; repr., Boston: Harvard Common Press, 1983), 20.

17 Hays, Gospel of Efficiency, 62. See also Peffer, Closing of the Public Domain, 45–58.

18 Merrill, Public Lands and Political Meaning, 221n23.

19 Peffer, Closing of the Public Domain, 5. See also Merrill, Public Lands and Political Meaning, 58.

20 U.S. Congress, Senate, Doc. 189, Report of the Public Lands Commission with Appendix, 58th Cong., 3d sess., 1905, xxi.

21 The Forest Service reprinted the recommendations of Coville and notable rancher-turned-forester Albert Potter in a separate bulletin titled Grazing on the Public Lands: Extract from the Report of the Public Lands Commission (Washington, DC: USDA, Forest Service Bulletin No. 62, 1905), 64.

22 Grazing on the Public Lands, 67.

23 Grazing on the Public Lands, 67.

24 Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing, 46.

25 This phrase came from a February 1, 1905, letter regarding the purpose of the national forests for Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson written by Gifford Pinchot. For a reprint, see Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground (1947; repr., Washington, DC: Island Press, 1974), 261–62.

26 Marion Clawson, The Western Range Livestock Industry (1950; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1979), 11–12. 27 Coville, Forest Growth and Sheep Grazing, 52. 28 Benjamin Horace Hibbard, A History of Public Land Policies (1924; repr., University of Wisconsin Press, 1956), 563.