12 minute read

The Fight of Their Lives

Here, meet just a few of the Pioneers on the front lines:

In the ‘Belly of the Beast’

Nick Hallett ’18

A lot has changed for Nick Hallett ’18 since March 2020. For one, he left his position as a cardiopulmonary ICU nurse at Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse to answer the desperate call for nurses downstate just as the pandemic began. He quickly secured a contract position with Aya Healthcare, a travel nursing agency that assigned him to a crisis relief position in an understaffed, COVID-only hospital in New Jersey—what he called “in the belly of the beast” of the crisis. In August, he moved again—this time across the country to southern California, for another COVID-relief assignment at an ICU in Orange County. On top of it all, Hallett found time to marry his longtime girlfriend and fellow UC nursing alum, Samantha Warner Hallett ’17, on August 8, 2020.

Back in April, during one of the biggest COVID surges in the New York City area, we talked to Hallett about what his experience had taught him about COVID-19, the nursing profession—and himself:

The virus is unpredictable—and probably scarier than we think.

By now, the general public is familiar with the telltale signs of COVID-19: fever, cough, shortness of breath. But in the worst cases, says Hallett, the virus attacks the body in strange and even more devastating ways.

“We’ve seen many, many patients die from cardiac arrest,” says Hallett. “We’re just learning now how the virus affects the heart, the lungs, and the kidneys, thickening the blood and causing blood clots.”

For Hallett and his team of doctors, this makes treating the virus like shooting a moving target.

“We will devise a treatment plan that has to completely change the next day because of how this virus progresses in the body,” he says. “It’s like nothing we’ve seen before.”

Nurses are improvising.

“This has been the most trying assignment of my life,” says Hallett.

Compared to most hospitals, says Hallett, his facility has not experienced the dire shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) so widely reported in the news. But there have been challenges.

When Hallett arrived at work one day to find only sizesmall N95 face masks, a colleague suggested buying his own reusable respirator online. Sold out nearly everywhere, Hallett eventually found one on eBay—marked up about four times the normal price. “That’s capitalism at its finest,” he says with a laugh.

One crucial piece of equipment in short supply, says Hallett, are the monitors that allow nurses to keep tabs on an ICU patient’s vital signs from outside the patient’s room.

“In a typical ICU, that large monitor screen would be visible through a glass window or wall, so the nurse could check vitals without having to enter the room,” he says.

In his makeshift ICU, only small travel monitors are available, requiring Hallett and his fellow nurses to “gown up” and enter the patient’s room multiple times an hour to check his or her vitals.

But thanks to a company’s donation of baby monitors, Hallett fashioned his own system by duct-taping the camera portion of the baby monitor to the travel monitor’s display, allowing him to see the patient’s information from anywhere in the unit.

“I keep that baby monitor in my pocket and check it more than I check my phone,” he says.

The rules have changed.

In nursing school, Hallett learned one thing above all else: do whatever you can to save a life. “When a patient is coding [experiencing cardiopulmonary arrest], we were taught to do whatever it takes,” he says. “You’d do compressions for hours if necessary.”

But in the midst of the pandemic, Hallett finds himself and his colleagues making a heartbreaking calculation all too often.

“Sometimes it’s more dangerous for the patient and the healthcare workers to continue these interventions,” he says.

Nick Hallett '18

- Nick Hallett ’18

For instance, life-saving chest compressions require close contact between the patient and healthcare workers. The virus is easily transmissible through the patient’s bodily fluid and droplets in the air, putting everyone in the area at risk. What’s more: ICU beds are in demand. When one patient is discharged or passes away, there’s a long line of new, severely ill patients waiting to take his or her place.

“It was a rude awakening the first time a patient was coding,” he says. “We did several rounds of compressions and a doctor said, ‘I think we should call it.’”

“I got into this profession to save lives, but in this situation, you have to make difficult decisions for the greater good.”

Optimism is everything.

When a typical day includes delivering the news of a loved one’s death to a family—sometimes in person but more often via FaceTime—it’s not easy to leave work behind at the end of a long shift, says Hallett.

“Dumb stuff” on Netflix helps him decompress, as does Hallett’s self-imposed boycott of Facebook and other social media (Facebook friends who claim the pandemic is a “hoax” are especially grating). And despite leaving behind his fiancé, also a nurse, back in Syracuse, Hallett is joined in his New Jersey apartment by his dog, Oliver.

“It’s nice to have some sort of companionship,” he laughs.

But more than anything else, says Hallett, staying mentally healthy is all about his outlook.

“Strangely enough, this whole situation has made me more of an optimist,” he says. “I’m constantly looking for the good in things. We are discharging patients. In my unit, we have saved 10 patients who have coded.

“I have to keep thinking about the positive,” he says. “Despite everything, people are getting better.”

Helping Young People Cope

Loretta Plescia ’06

Beyond the physical toll of the COVID-19 crisis, the emotional effects can be devastating to those who already struggle with mental health issues. A Recreational Therapist at Mohawk Valley Psychiatric Center in Utica, New York, Loretta Plescia ’06 is helping kids and young adults manage the mental burden.

UM: How has your work changed amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

LP: Pre-COVID, my day usually consisted of planning and implementing Dialectal Behavioral Therapy (DBT) Groups and Recreation Therapy groups to patients from the ages of 5-17. These children suffer from different mental health issues including anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Programming has changed based on the CDC recommendations, especially with social distancing. It has changed what interventions and materials that we use for the health safety of both the patients and staff. The work itself is a little more challenging. Many of those we treat are already anxious and depressed because of their own life stressors, and they now have to worry about the unknown of this pandemic on top of it. Also, with social distancing we are having smaller groups of both staff and kids, so instead of all sitting together at a table, we are spaced out. It seems to be a little less personal.

Loretta Plescia '06

UM: You’re one of many whose work is deemed essential amid this crisis. Why do you feel the work you do is essential in not just times like these, but all the time?

LP: As a recreational therapist, I work with the whole person. We treat all the domains—physical, cognitive, emotional, social and spiritual. I offer interventions that help the person be successful while teaching leisure and coping skills. Here at MVPC, working with young people who struggle with mental health issues, I teach them skills they can use while here in the hospital and when they are out in the community. My goal every day is to make them believe that life is worth living, even in the toughest times.

Turning Patient Care Upside Down

Dan Kemp ’17 DPT

Dan Kemp, an acute care physical therapist at Rome Memorial Hospital in Rome, New York, is pioneering new techniques that may improve outcomes for intubated patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

UM: When did COVID-19 first appear on your radar?

DK: When we started seeing the staggering numbers down in New York City and in all the major cities in March, I realized that this was going to be something that we were going to be dealing with rather quickly here in the Mohawk Valley. I knew I had to buckle down and find a way to help these patients in my own way. It clicked to me that with the acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by the virus, patients exhibiting severe symptoms have a greater chance of oxygenating well when they are prone, or on their stomachs or chest lying down on the bed. It changes the way that the lung works to truly allow the gas exchange to happen, giving the patient better oxygenation and a better chance at fighting this illness.

UM: Are you seeing positive results?

DK: The first patient who we proned reduced his oxygenation demand by nearly half the amount he required when he was supine. The pressure that was needed decreased quite a bit as well to allow him to continue to oxygenate. Now, this isn’t appropriate for every patient that COVID-19 impacts, but there are patients that are benefitting from it. Every time you think you have COVID-19 figured out, something else pops up that we didn’t know about the virus before. It makes you come back together as a team and think about how we can solve that aspect of the patient care. That’s something that’s going on throughout the country and the world. We’re constantly thinking of something different and trialing something else. But we’re fighting it.

Dan Kemp '17 DPT

UM: A cornerstone of the PT curriculum at UC is the evidence-based approach to clinical practice. Has that prepared you to deal with and respond to this health crisis?

DK: It’s one hundred percent applicable here. The program at UC always pushed us to be sure we’re providing what is optimal for our patients, what is suited as best practice, what is backed by evidence. Without that education and training—really, that way of thinking and approaching the work I do—I don’t think I’d have the knowledge, the confidence, or the strength to handle something like this. My professors always pushed us to think, “And then? And then? And then?” The surface answer was not good enough. That really prepared me for dealing with this crisis.

Fighting the Virus, One Test at a Time

Bryce Berie ’22

Bryce Berie is the first to admit—the test for COVID-19 is not pleasant.

It requires placing a sterile swab deep into a patient’s nasal passage to reach the nasopharynx, the upper part of the throat behind the nose. After several seconds, secretions are absorbed and a sample is collected.

Since March, Berie estimates he has administered more than 5,000 of these tests on patients ranging in age from six months to 92 years.

“Kids are usually the toughest to test,” says Berie. “I’ll say ‘OK, I’m going to pick your boogers now’ and that helps puts them at ease.”

From March until June, Berie, a Utica College junior and member of the U.S. National Guard, was stationed at a COVID-19 drive-through testing site in Suffolk County, New York. It was one of dozens of similar testing sites established throughout the country this spring and staffed, in part, by the National Guard and other medical volunteers. Berie and his troop were deployed to help with the testing efforts at Stony Brook University on Long Island, which converted much of its campus to accommodate testing operations and patient triage.

Fast and Furious

Along with the rest of the country, it was a whirlwind spring for Berie, who headed downstate from Utica in mid-March, at a time when Suffolk County had reported fewer than 100 cases of the coronavirus.

“We were told that the deployment would last around a week, so I planned to be down here for the duration of UC’s spring break,” he says.

But within days, the number of confirmed cases had nearly quadrupled, and it became clear to Berie and his commanders that the troop’s deployment would be extended. (By November 2020, Suffolk County had surpassed 49,000 confirmed cases.)

Berie remained in Long Island through the summer, when his work transitioned from testing in the drive through site in the University’s commuter parking lot to the University’s hospital.

Bryce Berie '22

Now back in Utica, Berie remains on active duty with the National Guard, testing incoming travelers for COVID-19 at Syracuse Hancock International Airport.

As for the emotional toll of his daily work, Berie is matter of fact: “It’s not easy,” he says. “I just try to be a calming presence [when testing], because people are scared.”

Is he scared? Of the virus, the death toll, and what the future might look like for him and the rest of the country, when and if this pandemic subsides?

“No, I’m not,” he says.

He joined the National Guard three years ago to help people, he explains. And in this time of national and global crisis, he’s proud to be doing just that.

“This,” says Berie, “is what I signed up for.”

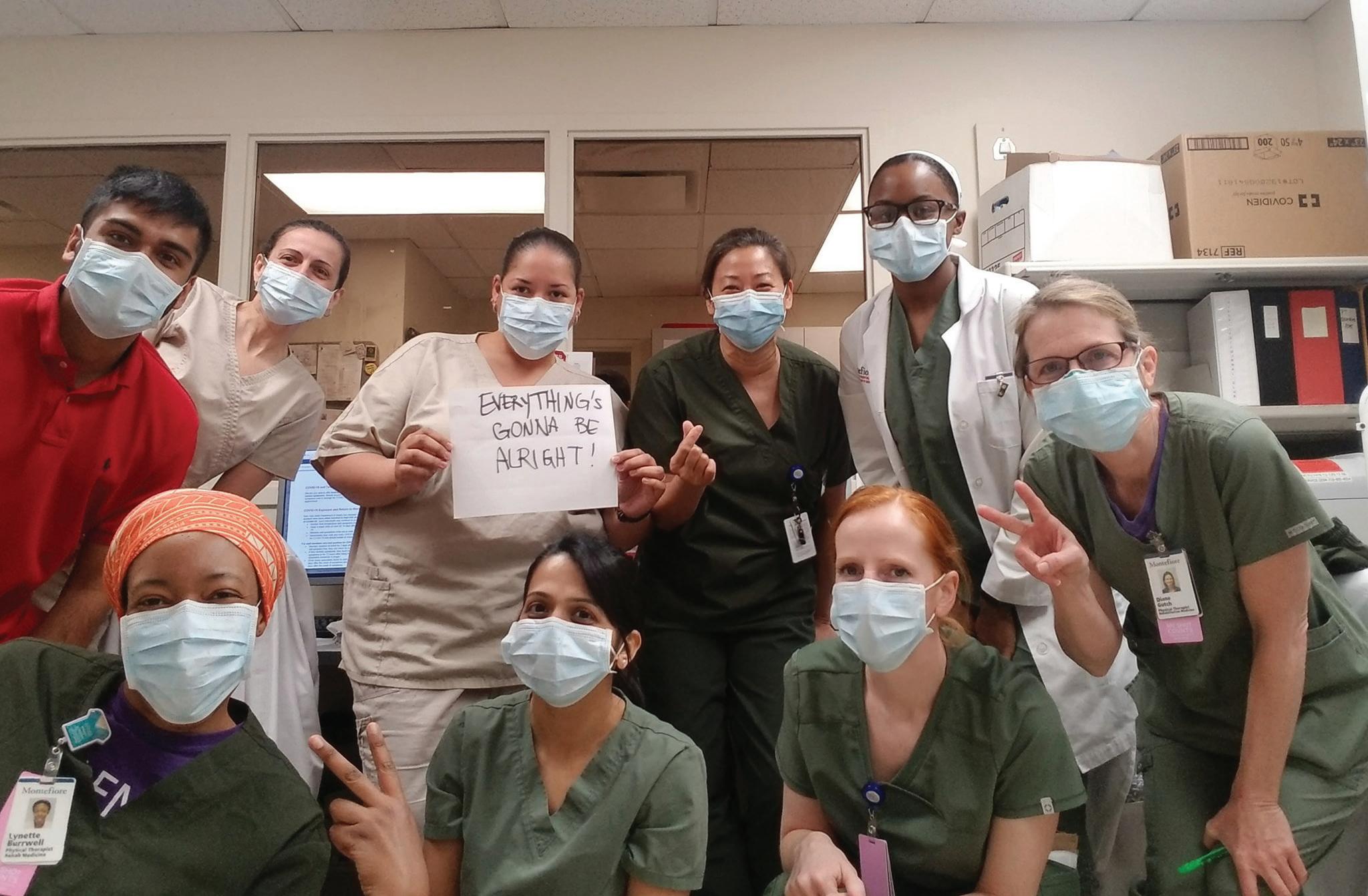

At the height of the spring surge in NYC, Utica College PT alumnae Nikolina Klindo Markovic ’02 (back row, second from left) Melissa Ortiz Dorset (third from left, holding sign), and Myra Choi ’00 (back row,second from right) do their best to stay positive at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx.

Into the Unknown

Melissa Ortiz Dorset ’03, G’05, ’08 DPT

As an acute care physical therapist at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, NY, Melissa Ortiz Dorset has seen firsthand the devastating effects of COVID-19—even after patients recover.

UM: What are you seeing in patients who have recovered from COVID-19?

MOD: The change in their endurance is the big thing. They become short of breath doing everyday things, they’re weaker and limited in their ability to live life as normal. We’re still learning about the long-term effects of COVID-19, and it varies so widely from patient to patient. But it’s significant to see how lasting the consequences have been.

UM: What’s the biggest misconception about this virus?

MOD: People don’t seem to understand how unpredictable it is. I’ve seen this virus affect people of all ages, all ethnicities, and from all walks of life. I’ve seen 20-year-olds who contract COVID and have mild symptoms, and others who end up on ventilators and feeding tubes. As a healthcare worker, that unpredictability is scary. We’re always trying to do what’s in the best interest of patients while protecting ourselves. With this virus, there’s still so much unknown.

- Melissa Ortiz Dorset